Abstract

Single atom alloys (SAAs) with maximum atomic efficiency and uniform active sites show great promise for heterogeneous catalytic applications. Meanwhile, crystal phase engineering has granered significant interest due to tailored atomic arrangements and coordination environments. However, the crystal phase engineering of SAAs remains challenging owing to high surface energy and complex phase transition dynamics. Herein, Ru1Co SAAs with tunable crystal phases (hexagonal-close-packed (hcp), face-centered-cubic (fcc), and hcp/fcc structure) are successfully synthesized via controlled phase transitions. These SAAs exhibit distinct crystal phase-dependent performance towards nitrate reduction reaction (NO3RR), where hcp-Ru1Co outperforms its counterparts with a NH3 Faradaic efficiency of 96.78% at 0 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode and long-term stability exceeding 1200 h. Mechanistic investigations reveal that the hcp configurations enables shorter Ru-Co distances, stronger interatomic interactions, and more positive surface potential compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co, which enhances the NO3− adsorption, reduces the free energy barrier, and suppresses competitive hydrogen evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Noble metal-based nanomaterials have attracted considerable attention in electrocatalysis due to their unique catalytic properties1,2. Theoretically, modulating the crystal structure can tailor the coordination geometry and electronic configuration of active sites, thereby affecting the adsorption/desorption behavior of reactants and intermediates, which ultimately regulates catalytic performance3,4. However, the inherent characteristics of metallic bonds (their unsaturated and non-directional nature) tend to drive metal catalysts toward conventional crystal structures5,6. For instance, Ru typically forms a hexagonal-close-packed (hcp) structure while Pt adopts a face-centered-cubic (fcc) arrangement. This structural persistence presents significant challenges in both controlling crystal phase modifications and establishing clear structure–property relationships in metallic catalytic systems.

To minimize noble metal usage while enhancing catalytic performance, the atomic dispersion of noble metal atoms within a host metal matrix to form single-atom-alloys (SAAs) has emerged as an effective strategy7,8,9. SAAs can realize the maximum utilization of metal atoms, uniform active sites, peculiar geometric and electronic structures, which collectively contribute to superior catalytic properties10,11,12,13. The well-defined active centers in SAAs further facilitate fundamental investigations of structure–activity relationships and catalytic mechanisms. Nevertheless, constructing SAAs with tailored crystal structures remains challenging due to the high surface energy of isolated metal atoms and the lack of effective synthetic methods for precise crystal phase control at the nanoscale. Notably, successful demonstrations of crystal phase engineering in SAAs have not yet been reported.

Herein, we successfully synthesize Ru1Co SAAs with distinct crystal phases (i.e., hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co) through a solvothermal method followed by thermal annealing. These obtained Ru1Co SAAs are employed as electrocatalysts for nitrate reduction reaction (NO3RR) to ammonia (NH3). Remarkably, hcp-Ru1Co demonstrates competitive performance with a NH3 Faradaic efficiency (\({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)) of 96.78% at 0 V vs. reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE). The energy consumption (EC) and NH3 production cost for hcp-Ru1Co are calculated as 19.04 kWh kg−1 and 0.57 $USD kg−1, respectively. Additionally, hcp-Ru1Co maintains operational stability for over 1200 h. Combined experimental and theoretical analyses reveal that hcp-Ru1Co possesses reduced Ru–Co distances, enhanced Ru–Co interatomic interactions, and more positive surface potential compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co, collectively promoting NO3− adsorption, lowering the free energy barrier, and suppressing hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). A prototype Zn-NO3− battery employing hcp-Ru1Co as the cathode catalyst demonstrates high electrochemical performance.

Results

Synthesis and structural characterizations

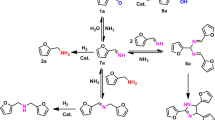

The Ru1Co SAAs with different crystal phases are successfully synthesized via a solvothermal method followed by thermal annealing (see the “Methods” section for experimental details and Fig. 1a for schematic illustration). Specifically, CoCl2·6H2O and RuCl3·xH2O precursors are dissolved in 1,4-butanediol and heated at 230 °C for 20 min. Subsequent annealing at 300, 500, and 700 °C for 30 min yields hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co, respectively.

The crystal phases of synthesized samples are characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Fig. 1b, d, the diffraction peaks of hcp-Ru1Co match well with those of hcp-Co (JCPDS No. 05-0727), while fcc-Ru1Co exhibits the diffraction peaks well indexed to fcc-Co (JCPDS No. 15-0806). Notably, the diffraction peaks of both hcp-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co exhibit slightly negative shifts compared to those of hcp-Co and fcc-Co, indicating the successful incorporation of Ru with a large atomic radius into the Co matrix. The XRD pattern of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co shows the coexistence of diffraction peaks from both phases (Fig. 1c), verifying the successful synthesis of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co. Rietveld refinement profiles demonstrate high phase purity in all Ru1Co SAAs. Inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) analysis confirms consistent Co/Ru atomic ratios of 99.25/0.75 in all Ru1Co SAAs (Supplementary Table 1).

The morphology of hcp-Ru1Co is investigated through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM), which reveals a homogeneous nano-urchin structure (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Atomic-scale characterization via aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM (AC-HAADF-STEM) utilizes Z-contrast imaging, where Ru atoms (Z = 44) exhibit brighter atomic-scale contrast compared to Co (Z = 27). As shown in Fig. 2b, isolated Ru atoms are observed without detectable clusters or nanoparticles, confirming the atomic dispersion of Ru in the Co matrix. Three-dimensional (3D) surface plots converted from the cyan square in Fig. 2b are analyzed. High-intensity spots represent Ru atoms, while low-intensity spots correspond to Co atoms. The isolated Ru spots in Fig. 2c provide additional evidence of Ru atomic dispersion. The atomic arrangement of hcp-Ru1Co is further revealed by high-resolution AC-HAADF-STEM (Fig. 2d). An enlarged view from the cyan square in Fig. 2d shows the atomic columns along the [110] zone axis (Fig. 2e), closely matching the simulated atomic model of hcp-Co (Fig. 2g). The corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern (Fig. 2f) aligns with the simulated electron diffraction pattern of hcp-Co (Fig. 2h). Interplanar spacings measured from the intensity profiles (converted from orange rectangles in Fig. 2d) are 0.21 and 0.19 nm, corresponding to the (110) and (111) planes of hcp-Ru1Co, respectively (Fig. 2i, j). Notably, the presence of isolated peaks with relatively high intensity further confirms the atomic dispersion of Ru. HAADF-STEM image and corresponding elemental mappings demonstrate the uniform distribution of Ru and Co in the nano-urchin structure (Fig. 2k–n). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) reveals the Ru/Co atomic ratio of 99.24/0.76 (Supplementary Fig. 3), consistent with ICP-OES results.

a TEM image of hcp-Ru1Co. b HAADF-STEM image of hcp-Ru1Co. c 3D surface plots converted from the cyan square in (b). d High-resolution AC-HAADF-STEM image of hcp-Ru1Co. e Enlarged AC-HAADF-STEM image taken from the cyan square in (d). f The corresponding FFT pattern. g and h The simulated atomic model (g) and the electron diffraction pattern (h) of hcp-Co viewed along the [110] zone axis. i and j Intensity profiles from the orange rectangles in (d). k–n HAADF-STEM image (k) and corresponding elemental mappings (l–n) of hcp-Ru1Co. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

The structural characteristics of fcc-Ru1Co are systematically investigated. TEM image confirms the preserved nano-urchin morphology (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Atomic dispersion of Ru in the Co matrix is verified by HAADF-STEM (Fig. 3b) and 3D surface plot analysis (Fig. 3c). An enlarged AC-HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 3e) from the purple square in Fig. 3d shows the atomic columns along the [110] zone axis, matching the simulated atomic model of fcc-Co (Fig. 3g). The corresponding FFT pattern (Fig. 3f) aligns with the simulated diffraction pattern of fcc-Co (Fig. 3h). Interplanar spacing measurements yield 0.21 nm, corresponding to the (111) plane of fcc-Ru1Co, with isolated Ru peaks confirming atomic dispersion (Fig. 3i, j). For hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, TEM image reveals the conserved nano-urchin structure (Fig. 3k and Supplementary Fig. 5). HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 3l) and 3D surface plots (Fig. 3m) confirm the atomic dispersion of Ru. High-resolution AC-HAADF-STEM image reveals two types of atomic arrangements with distinct heterophase boundary (Fig. 3n). FFT patterns (Fig. 3o and p) from the selected purple and cyan squares in Fig. 3n, align with the simulated diffraction patterns of fcc-Co along the [110] zone axis (Fig. 3q) and hcp-Co along the [111] zone axis (Fig. 3r), respectively. FFT pattern (Supplementary Fig. 6b) from the boundary region (orange square) in Supplementary Fig. 6a, reveals the overlapped electron diffraction dots along the [110] zone axis of fcc-Co ([110]fcc) and the [111] zone axis of hcp-Co ([111]hcp) (Supplementary Fig. 6c). The intensity profiles from the orange rectangles in Fig. 3n reveal the interplanar spacings of 0.21 and 0.20 nm, assigned to the (111) plane of fcc-Ru1Co and (011) plane of hcp-Ru1Co, respectively (Fig. 3s, t). The existence of the isolated maximum peaks further confirms Ru atomic dispersion.

a TEM image of fcc-Ru1Co. b AC-HAADF-STEM image of fcc-Ru1Co. c 3D surface plots converted from the purple square in (b). d High-resolution AC-HAADF-STEM image of fcc-Ru1Co. e Enlarged HAADF-STEM image extracted from the purple square in (d). f The corresponding FFT pattern. g and h The simulated atomic model (g) and the electron diffraction pattern (h) of fcc-Co oriented along the [110] zone axis. i and j Intensity profiles from the orange rectangles in (d). k TEM image of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co. l AC-HAADF-STEM image of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co. m 3D surface plots extracted from the blue square in (h). n High-resolution AC-HAADF-STEM image of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co. o and p FFT patterns extracted from the squares in (n). q and r The simulated electron diffraction patterns oriented along the [110]fcc and [111]hcp zone axes. s and t Intensity profiles from the rectangles in (n). Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

The electronic structure and coordination environment of Ru1Co SAAs with different crystal phases are investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). XPS analysis confirms that metallic Co and Ru are dominant in all Ru1Co SAAs (Supplementary Fig. 7). The Ru 3p XPS spectrum of hcp-Ru1Co exhibits peaks at 461.38 and 483.56 eV, assigned to 3p3/2 and 3p1/2 of Ru0, respectively14. A positive shift in the binding energy of Ru0 3p3/2 peak is observed for hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (461.79 eV) and fcc-Ru1Co (462.01 eV) compared to hcp-Ru1Co (461.38 eV), suggesting reduced electron density on Ru in hcp-Ru1Co. The observed oxides are attributed to the easy oxidation characters of Co and Ru in air, in accordance with previous reports15,16. Figure 4a displays the normalized Co K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of Ru1Co SAAs and references (i.e., Co foil and Co3O4). The absorption edges of all Ru1Co SAAs are close to Co foil but with slight shifts towards higher energy, indicating the metallic characteristics of Co with reduced electron density. This is attributed to the lower electronegativity of Co (1.9) compared to Ru (2.2), resulting in electron transfer from Co to Ru17. This directional electron transfer is further corroborated by the decreased valence state of Ru in hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co relative to Ru foil, as revealed in the normalized Ru K-edge XANES spectra (Fig. 4c). Notably, the Co K-edge adsorption of hcp-Ru1Co positively shifts compared to fcc-Ru1Co and hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (inset of Fig. 4a), with the opposite trend observed for the Ru K-edge adsorption (inset of Fig. 4c), suggesting a stronger electronic interaction between Co and Ru in hcp-Ru1Co.

a The normalized Co K-edge XANES spectra of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, fcc-Ru1Co, Co foil, and Co3O4. b The Co K-edge FT-EXAFS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, fcc-Ru1Co, Co foil, and Co3O4. c The normalized Ru K-edge XANES spectra of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, fcc-Ru1Co, Ru foil, and RuO2. d The Ru K-edge FT-EXAFS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, fcc-Ru1Co, Ru foil, and RuO2. e The Ru K-edge EXAFS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, fcc-Ru1Co, Ru foil, and RuO2. f-i The WT-EXAFS contour plots of hcp-Ru1Co (f), hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (g), fcc-Ru1Co (h), and Ru foil (i) at Ru K-edge. j In situ CO-DRIFTS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co at room temperature. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy is performed to probe the local atomic configurations. The Co K-edge Fourier transformed EXAFS (FT-EXAFS) spectra of Ru1Co SAAs display a prominent peak at 2.17 Å, matching the characteristic Co–Co bond observed in Co foil (Fig. 4b). This consistent peak position results from the low Ru concent and the predominant Co–Co bond in Ru1Co SAAs. The Ru K-edge FT-EXAFS spectrum of Ru foil shows a peak at 2.35 Å, corresponding to the Ru–Ru metallic bond (Fig. 4d). In contrast, hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co exhibit the prominent peaks at 2.10, 2.13, and 2.17 Å, respectively. The significant differences in peak positions between Ru foil and Ru1Co SAAs suggest that the prominent peak of Ru1Co SAAs is not contributed by Ru–Ru metallic bond, but Ru–Co metallic bond. The absence of Ru–Ru bond further confirms the atomic dispersion of Ru in Ru1Co SAAs. Notably, the Ru–Co bond length in hcp-Ru1Co is shorter than that in fcc-Ru1Co and hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, suggesting enhanced interatomic interactions between Ru and Co in hcp-Ru1Co, consistent with the XANES results.

The least-squares EXAFS fitting curves and fitting parameters are provided in Supplementary Figs. 8–17 and Tables 2 and 3. The Co K-edge EXAFS oscillation functions reveal minor variations in both oscillation frequencies and amplitudes for hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co, indicating similar coordination environment for Co species (Supplementary Fig. 18). In contrast, the Ru K-edge EXAFS oscillation functions of Ru1Co SAAs exhibit significant differences, reflecting substantial variations induced by crystal phase differences (Fig. 4e). The Co K-edge wavelet-transformed EXAFS (WT-EXAFS) contour plot of Co foil shows a local maximum at k = 7.21 Å−1 and R = 2.17 Å, similar to that of hcp-Ru1Co (k = 7.25 Å−1, R = 2.17 Å), hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (k = 7.42 Å−1, R = 2.17 Å), and fcc-Ru1Co (k = 7.59 Å−1, R = 2.17 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 19). However, the Ru K-edge WT-EXAFS contour plot reveals that hcp-Ru1Co exhibits a local maximum at k = 7.69 Å−1 and R = 2.10 Å, which is significantly different from Ru foil (k = 9.52 Å−1, R = 2.35 Å) and assigned to Ru–Co bond (Fig. 4f, i). Additionally, the lower R value in hcp-Ru1Co (2.10 Å) in comparison with hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (2.13 Å) and fcc-Ru1Co (2.17 Å) further confirms the shorter Ru–Co bond in hcp-Ru1Co (Fig. 4g, h). These results collectively confirm that hcp-Ru1Co possesses a shorter Ru–Co bond and thus stronger interatomic interaction compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co.

To further confirm the atomic dispersion of Ru in Ru1Co SAAs with different crystal phases, in situ CO diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (CO-DRIFTS) is performed (Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 20). Following CO adsorption at room temperature, two broad peaks at 2170 and 2121 cm−1 are observed, corresponding to the mononuclear (Ruδ+(CO)) and tricarbonyl species adsorbed on single Ru atom (Ruδ+(CO)3), respectively18,19,20. The absence of peaks below 2000 cm−1, which is the fingerprint of bridge-bonded CO, confirms the absence of Ru clusters or nanoparticles21,22.

Electrocatalytic NO3RR performance

The electrocatalytic NO3RR performance is evaluated using an H-type cell. Ru1Co SAAs supported on Ni foam (NF) serve as the working electrode, with Ag/AgCl (saturated KCl) and Pt wire as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. The electrolyte contains 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 M NaOH with 200 ppm NO3−-N. All potentials are referenced to the RHE scale. Figure 5a displays the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves of Ru1Co SAAs in electrolyte with/without 200 ppm NO3−-N. Apparently, upon the addition of NO3−, significant enhancement in current density is observed, indicating the occurrence of NO3RR. Notably, hcp-Ru1Co demonstrates the highest current density in the presence of NO3− and the lowest current density in the absence of NO3−, indicating superior NO3RR activity and suppressed hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) (Supplementary Fig. 21).

a LSV curves of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 in an electrolyte containing 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 M NaOH with and without 200 ppm NO3−-N at room temperature (25 °C). b \({{\mbox{FE}}}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\) of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co at different potentials. c Comparison of \({Y}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\), \({{\mbox{FE}}}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\), \({C}_{{{\mbox{NO}}}_{3}^{-}}\), \({S}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\), \({j}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\), and \({{\mbox{EE}}}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\) over hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co at 0 V. d NH3 production cost of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co at different potentials. e Ea of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co at 0 V. f \({Y}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\) of hcp-Ru1Co at 0 V obtained by colorimetric and 1H NMR methods (the insets are UV–Vis absorption and 1H NMR spectra of post-electrolyzed solution over hcp-Ru1Co at 0 V). g Chronopotentiometry curve of hcp-Ru1Co in an H-type continuous-flow cell at 20 mA cm−2 with corresponding \({Y}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\) and \({{\mbox{FE}}}_{{{\mbox{NH}}}_{3}}\). h In situ Raman spectra of hcp-Ru1Co during chronopotentiometry test at different potentials in an electrolyte containing 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 M NaOH with 200 ppm NO3−-N. All potentials are referenced to the RHE scale without iR compensation. Catalyst loading amount for all NO3RR tests is 3 mg cm−2. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three independent measurements. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

The NO3RR performance of Ru1Co SAAs is systematically investigated through chronoamperometric tests at different potentials. The concentrations of NO3−-N and NH4+-N are quantified by colorimetric methods via UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). As shown in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 24, hcp-Ru1Co exhibits superior performance with maximum NH3 yield rate (\({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)) of 1.33 ± 0.06 mg h−1 cm−2 at −0.1 V and NH3 Faradaic efficiency (\({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)) of 96.78 ± 1.97% at 0 V, significantly outperforming hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (0.90 ± 0.06 mg h−1 cm−2, 84.41 ± 3.70%) and fcc-Ru1Co (0.39 ± 0.05 mg h−1 cm−2, 56.94 ± 2.60%). The minimal concentrations of by-products (i.e., NO2−, N2H4, N2, and H2) confirm the high NH3 selectivity of hcp-Ru1Co (Supplementary Figs. 25–31). At 0 V, hcp-Ru1Co demonstrates higher values of \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\), \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\), NO3− conversion (\({C}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}}\)), NH3 selectivity (\({S}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)), half-cell energy efficiencies of NH3 (\({{{\rm{EE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)) and NH3 partial current density (\({j}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)) compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 32 and 33). Notably, under high-concentration conditions (1400 ppm NO3−-N), hcp-Ru1Co delivers \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of 11.65 ± 0.46 mg h−1 cm−2 at −0.1 V and \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of 100% at 0 V (Supplementary Fig. 34). These metrics position it among the most active metal-based catalysts for NO3RR (Supplementary Table 4).

EC and NH3 production cost analyses are explored only considering the price of renewable electricity (0.03 $USD kWh−1, full levelized cost of electricity for utility solar power according to the announcement by the US Department of Energy for the 2030 target)23,24,25. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 35 and Fig. 5d, EC and NH3 production cost of hcp-Ru1Co are calculated as 19.04 ± 1.10 kWh kg−1 and 0.57 ± 0.03 $USD kg−1 at 0.1 V, respectively, significantly lower than those of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (37.0 ± 0.37 kWh kg−1, 1.11 ± 0.01 $USD kg−1) and fcc-Ru1Co (288.78 ± 0.50 kWh kg−1, 8.66 ± 0.02 $USD kg−1). Notably, the EC values of hcp-Ru1Co at all potentials are significantly lower than commercial benchmarks (1–1.5 $ kg−1)26, highlighting its industrial viability. Temperature-dependent \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) measurements reveal the apparent activation energy (Ea) of 3.49 kJ mol−1 for hcp-Ru1Co, significantly lower than that of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (14.22 kJ mol−1) and fcc-Ru1Co (25.55 kJ mol−1), confirming the accelerated NO3RR kinetics (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 36). In addition, hcp-Ru1Co possesses a larger electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co (Supplementary Fig. 37, Table 5), consistent with the N2 adsorption–desorption results (Supplementary Fig. 38). \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) values normalized to ECSA and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area indicate the superior intrinsic activity of hcp-Ru1Co (Supplementary Figs. 39 and 40). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) reveals reduced charge transfer impedance for hcp-Ru1Co, attributed to its distinctive hcp structure and large ECSA (Supplementary Fig. 41).

To verify that the produced NH3 originates from the NO3RR process catalyzed by hcp-Ru1Co, control experiments are carried out. Negligible NH3 is detected in solutions of 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 M NaOH at 0 V or in solutions of 0.5 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 M NaOH with 200 ppm NO3−-N at open circuit potential (OCP), and using pure NF substrate as the working electrode (Supplementary Fig. 42). 15N isotope labeling experiments employing 15NO3− as nitrogen source yield characteristic 15NH4+ peaks at δ = 6.91 and 7.06 ppm in 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 43), confirming NH3 generation through NO3RR (Supplementary Fig. 44). \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) values obtained from 1H NMR method match those from colorimetric analysis (Fig. 5f), validating both analytical methods.

Durability is a pivotal aspect in evaluating the performance of electrocatalysts. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 45, negligible changes in \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) and \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of hcp-Ru1Co during 12 consecutive recycling tests demonstrate its robust electrochemical stability. Chronopotentiometric test under continuous electrolyte flow (2 mL min−1, Supplementary Fig. 46) maintains stable \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) and \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) over 1200 h of prolonged operation (Fig. 5g). Post-stability characterizations confirm the retention of nano-urchin morphology, atomic Ru dispersion (Supplementary Fig. 47), crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 48), and chemical states (Supplementary Fig. 49). In situ Raman spectroscopy during NO3RR only detects the vibration mode of SO42− (981 cm−1) from electrolyte (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 50)27. No additional Raman peaks are observed at all applied potentials, suggesting that hcp-Ru1Co does not transform into oxide during NO3RR. Furthermore, hcp-Ru1Co exhibits competitive performance across a broad range of NO3−-N concentrations (100–500 ppm), suggesting its wide applicability (Supplementary Fig. 51). As current density increases from 50 to 500 mA cm−2, \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of hcp-Ru1Co progressively rises, attaining a maximum value of 25.52 mg h−1 cm−2 at 500 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 52).

Mechanistic studies

Recent studies have highlighted the critical role of catalyst surface potential in regulating NO3− adsorption, where elevated surface potentials significantly enhance NO3− adsorption and improve NO3RR performance28,29,30. To explore the surface potential of Ru1Co SAAs, Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) is conducted (Fig. 6a). The average surface potential of hcp-Ru1Co achieved by contact potential difference is 155 mV, substantially exceeding that of hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (100 mV) and fcc-Ru1Co (44 mV) (Fig. 6b). This enhanced surface potential of hcp-Ru1Co, attributed to its unique hcp structure, facilitates NO3− adsorption and thereby accelerates the reaction kinetics. To quantitatively assess NO3− adsorption behavior, Ru1Co SAAs are immersed in an electrolyte containing 200 ppm NO3−-N and agitated for 30 min, the NO3− adsorption capacity (qe) is determined by measuring the concentration of NO3− in solution before and after agitation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 53, hcp-Ru1Co achieves a qe value of 1.91 ± 0.05 μmol mgcat.−1, significantly surpassing hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (1.20 ± 0.03 μmol mgcat.−1) and fcc-Ru1Co (0.77 ± 0.02 μmol mgcat.−1). Furthermore, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) analysis of Ru1Co SAAs with absorbed NO3− further confirms the enhanced NO3− adsorption on hcp-Ru1Co, evidenced by intensified absorption at 1350 cm−1 corresponding to anti-symmetric stretching vibrations of NO3− (Supplementary Fig. 54)31. These findings collectively demonstrate that hcp-Ru1Co possesses a stronger NO3− adsorption, contributing to its enhanced NO3RR performance.

a Surface potential distribution of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co. b The corresponding surface potentials. c In situ ATR-SEIRAS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co at different potentials. d Online DEMS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co during the NO3RR process. e The PDOS profiles of hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co. The vertical dashed lines indicate the position of the d-band center. f and g The optimized structure models of hcp-Ru1Co (f) and fcc-Ru1Co (g). h and i 2D deformation charge density difference maps of hcp-Ru1Co (h) and fcc-Ru1Co (i). j The charge density difference of *NO3 adsorbed on hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co (electron accumulation and depletion are indicated by yellow and cyan regions, respectively). k The free energy diagrams of NO3RR over hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co. Source data for this figure are provided as a Source Data file.

To probe into the intermediates formed during the NO3RR process, in situ attenuated total reflection surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS, Supplementary Fig. 55) and online differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS, Supplementary Fig. 56) are carried out. In situ ATR-SEIRAS spectra of hcp-Ru1Co (Fig. 6c) display characteristic peaks at 1595, 1483, 1438, 1235, and 1168 cm−1, attributed to the vibrations of *NO, *NH3, *NH2, *NO2, and *NH2OH, respectively32,33. The peak at 1668 cm-1 is assigned to the bending vibration of the adsorbed H2O34. Online DEMS analysis during chronoamperometry test at 0 V reveals the mass signals of mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of 46, 33, 32, 31, 30, and 17, attributed to *NO2, *NH2OH, *NHOH, *NHO, *NO, and *NH3, respectively (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 57). Based on these detected intermediates, the NO3RR pathway is deduced, involving the following key intermediates: *NO3 → *NO2 → *NO → *NHO → *NHOH → *NH2OH → *NH2 → *NH3.

To gain preliminary insights into the enhanced NO3RR performance of hcp-Ru1Co, density functional theory (DFT) calculations are performed. The optimized structure models are provided in Supplementary Fig. 58 and Supplementary Data 1. Partial density of state (PDOS) profiles reveal that hcp-Ru1Co exhibits a d-band center at −1.03 eV, positioned closer to the Fermi level compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (−1.33 eV) and fcc-Ru1Co (−1.36 eV) (Fig. 6e). The upshift of the d-band center for hcp-Ru1Co could theoretically favor the adsorption of intermediates. Additionally, the effect of the crystal structure on Ru–Co interatomic interaction is explored. As shown in the structure models (Fig. 6f, g), hcp-Ru1Co possesses a relatively shorter Ru–Co bond length (2.53 Å) than fcc-Ru1Co (2.55 Å), consistent with XAS findings. 2D deformation charge density maps and Bader charge analysis demonstrate electrons transfer from Co to Ru (Fig. 6h, i), with hcp-Ru1Co showing a slightly larger charge transfer, indicating an enhanced Ru–Co interatomic interaction in hcp-Ru1Co.

Gibbs free energy of \({{{\rm {NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption \(\left(\Delta {G}_{*{{{\rm {NO}}}}_{3}}\right)\) reveals that hcp-Ru1Co exhibits a more negative \(\Delta {G}_{*{{{\rm {NO}}}}_{3}}\) of −0.74 eV compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (−0.53 eV) and fcc-Ru1Co (−0.05 eV) (Supplementary Fig. 59, Supplementary Data 1). This suggests a stronger NO3− adsorption on hcp-Ru1Co, which aligns with the results of NO3− adsorption capacity and FT-IR experiments in Supplementary Figs. 53 and 54. Charge density difference maps and Bader charge analysis demonstrate that 0.82 electrons are transferred from hcp-Ru1Co to *NO3, exceeding the amount transferred on hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (0.80 electrons) and fcc-Ru1Co (0.74 electrons) (Fig. 6j). Free energy diagrams identify the hydrogenation of *NO (*NO → *NHO) as the potential-determining step (PDS) for Ru1Co SAAs (Fig. 6k, Supplementary Figs. 60–62, Supplementary Data 1). Notably, hcp-Ru1Co exhibits a lower energy barrier of PDS (0.35 eV) compared to hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (0.39 eV) and fcc-Ru1Co (0.60 eV). Considering that HER is a primary competitive reaction, the free energy of *H adsorption is calculated (Supplementary Figs. 63, 64, Supplementary Data 1). The free energy required to generate by-product H2 for hcp-Ru1Co is 0.91 eV, higher than that for hcp/fcc-Ru1Co (0.51 eV) and fcc-Ru1Co (0.09 eV). This suggests that hcp-Ru1Co could potentially suppress the competing HER.

The performance of the Zn-NO3 − battery

The Zn-NO3− battery offers dual functionality by generating electricity while converting NO3− pollutants into valuable NH335. The Zn-NO3− battery is constructed by anchoring hcp-Ru1Co on NF as the cathode, paired with a zinc plate anode (Supplementary Fig. 65). The hcp-Ru1Co assembled Zn-NO3− battery exhibits a stable OCP of 1.405 V vs. Zn/Zn2+ (Supplementary Fig. 66). Two such batteries connected in series can power a bulb of 1.5 V (Supplementary Fig. 67). Additionally, the hcp-Ru1Co assembled Zn-NO3− battery delivers a high power-density of 6.55 mW cm−2, surpassing most recently reported Zn-NO3− batteries (Supplementary Fig. 68 and Table 6). At current densities of 2, 4, and 6 mA cm−2, the specific capacities of this battery are 576.81, 616.84, and 668.51 mAh g−1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 69). Consequently, the corresponding energy densities under these conditions are calculated as 470.03, 448.13, and 416.04 mWh g−1. The battery demonstrates high rate-capability and stable operation at current densities ranging from 1 to 20 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 70). Continuous discharge–charge cycling at 2 mA cm−2 suggests its robust stability (Supplementary Fig. 71). Additionally, it achieves an \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of 1.72 ± 0.02 mg h−1 cm−2 at 50 mA cm−2 and a \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of 90.93 ± 0.80% at 40 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 72). Minimal fluctuations in both \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) and \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) during consecutive recycling test at 40 mA cm−2 confirm robust long-term stability (Supplementary Fig. 73).

Discussion

In summary, Ru1Co SAAs with distinct crystal phases, i.e., hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co, are successfully synthesized through precise control of the phase transition process and exhibit crystal phase-dependent performance in NO3RR to NH3. Notably, hcp-Ru1Co demonstrates superior catalytic performance with \({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) of 96.78 ± 1.97% at 0 V, EC of 19.04 ± 1.10 kWh kg−1, NH3 production cost of 0.57 ± 0.03 $USD kg−1, and stable operation exceeding 1200 h, significantly outperforming hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co. Insightful experiments and theoretical calculations reveal that hcp-Ru1Co is featured with shorter Ru–Co interatomic distances, stronger Ru–Co interatomic interactions, and more positive surface potential, which enhance the adsorption capacity of NO3−, reduces the free energy barrier of PDS, and suppresses the HER. Furthermore, hcp-Ru1Co, when integrated as the cathode electrocatalyst into Zn-NO3− battery, demonstrates its significant potential for application in advanced energy devices. This study not only achieves precise control over the crystal phase of SAAs but also provides comprehensive insights into the relationship between the crystal structure of SAAs and catalytic performance.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2·6H2O, 99.0 wt%), ruthenium(III) chloride hydrate (RuCl3·xH2O, 99.95 wt%), 1,4-butanediol (98 wt%), sodium sulfate anhydrous (Na2SO4, 99.0 wt%), deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9 at% D), sodium hypochlorite solution (NaClO, available chlorine 5.5–6.5 wt%), ammonium chloride-15N (15NH4Cl, 98.5 wt%), sodium nitrate–15N (Na15NO3, 98.5 wt%), maleic acid (C4H4O4, 98.0 wt%), salicylic acid (C7H6O3, 99.5 wt%), sodium citrate dihydrate (C6H5Na3O7·2H2O, 99.0 wt%), N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (C12H14N2·2HCl, 98 wt%), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, 85 wt%), sulfanilamide (C6H8N2O2S, 99.5 wt%), and nitroferricyanide (III) dihydrate (Na2Fe(CN)5NO·2H2O, 99.0 wt%) were obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥96.0 wt%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95.0–98.0 wt%), hydrogen chloride (HCl, 36.0–38.0 wt%), and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, ≥99.5 wt%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Ethanol (C2H5OH, ≥99.7 wt%) was purchased from Tianjin Fuyu Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. Acetone (C3H6O, ≥99 wt%) was purchased from Yantai Far East Fine Chemical Co., Ltd. Nickel foam (NF, thickness: 2 mm) was purchased from Tianjin EVS Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. Nafion solution (D520, 5 wt%, Dupont) was purchased from Suzhou Sinero Technology Co., Ltd. Nafion 211 membrane (diameter: 3 cm, thickness: 25.4 μm) was purchased from SCI Materials Hub. All reagents were utilized without further purification. Deionized water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ was employed throughout all experimental procedures.

Synthesis of Ru1Co SAAs

0.08 M CoCl2·6H2O and 0.15 M NaOH were dissolved in 40 mL of 1,4-butanediol to form solution A. 0.015 g RuCl3·xH2O were dissolved in 5 mL of 1,4-butanediol to form solution B. Subsequently, solution B was gradually introduced into solution A under vigorous stirring for 30 min. The mixed solution was then heated to 230 °C for 20 min. The resulting product was washed with ethanol and acetone several times, and dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 3 h. Finally, the precursor powder was annealed at 300, 500, and 700 °C for 30 min at N2 atmosphere with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1 to form hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co and fcc-Ru1Co, respectively.

Fabrication of the working electrode

The working electrode was fabricated by immobilizing Ru1Co SAAs onto the pretreated nickel form (NF) substrate. In detail, NF was sequentially pretreated by sonication in HCl solution (3 M), followed by thorough rinsing with ethanol and deionized water to remove surface impurities. Subsequently, the synthesized sample (hcp-Ru1Co, hcp/fcc-Ru1Co, and fcc-Ru1Co; 20 mg each) was dispersed in a mixed solution consisting of 950 μL ethanol and 50 μL Nafion under sonication for 0.5 h to form a homogeneous ink. Finally, the ink (300 µL) was dropped onto the surface of the pretreated NF (1 × 1 cm2), and dried in air for 30 min to form the working electrode. The mass loading of the catalyst was calculated to be 3 mg cm−2.

Physicochemical characterizations

XRD patterns were acquired using a Rigaku SmartLab powder diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). TEM images were recorded using a HITACHI H-8100 electron microscope with an operation voltage of 200 kV. AC-HAADF-STEM was conducted on ThermoFisher Scientific Themis microscope (300 kV) equipped with image and probe correctors, using a beam current of 2 pA, a convergence angle of 25 mrad, and a collection angle range of 55–220 mrad conditions. ICP-OES was carried out on an Agilent 5110 system. XPS measurements were performed on an ESCALABMK II spectrometer equipped with Mg Kα excitation. The C1s peak at 284.8 eV was utilized for calibration. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was carried out at the 1W1B beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. In situ CO-DRIFTS experiments were performed on a Bruker Tensor II infrared spectrometer. UV–Vis absorbance spectra were collected using a SHIMADZU UV-1900 spectrophotometer. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 500 MHz spectrometer. DEMS measurements were conducted on a QAS 100 system (Linglu Instruments Co. Ltd). FT-IR spectroscopy was performed using a Perkin-Elmer spectrometer. In-situ ATR-SEIRAS spectra were collected using an INVENIO S FT-IR spectrometer equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector. Raman spectra were obtained using a LabRAM HR Evolution (Horiba) with a 532 nm excitation laser. KPFM images were acquired on a BRUKER Dimension Icon with ScanAsyst system. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured on a Quantachrome NOVA-3000 instrument.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical experiments were conducted in a H-type cell with a three-electrode configuration by CHI 760E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments Inc., China). The cathodic and anodic chambers are separated by a Nafion 211 membrane (diameter: 3 cm, thickness: 25.4 μm, DuPont). Prior to use, Nafion membrane underwent sequential pretreatment. First, the membrane was immersed in a 5% H2O2 solution and maintained at 80 °C for 1 h to eliminate organic contaminants. Subsequently, the membrane was repeatedly rinsed with deionized water and immersed in deionized water at 80 °C for 1 h to ensure the complete removal of any residual H2O2. After pretreatment, the membrane was stored in deionized water under ambient conditions.

A saturated Ag/AgCl electrode and a Pt wire served as the reference and counter electrode, while nickel foam anchored with the prepared Ru1Co SAAs (mass loading: 3 mg cm−2) was used as the working electrode. All potentials were referenced to the RHE scale without iR compensation using Eq. (1):

where the pH of electrolyte was measured to be 12.98 ± 0.12 using a pH meter (Mettler Toledo).

The electrolyte containing 0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH and 200 ppm NO3−-N, was prepared prior to the NO3RR tests by dissolving 71.02 g of Na2SO4 (0.5 mol), 4.00 g of NaOH (0.1 mol), and 1.21 g of NaNO3 in 1 L of deionized water within a volumetric flask. The solution was stored at room temperature (25 °C) for subsequent use. The electrolyte volume in cathodic and anodic chamber is 12.5 mL.

LSV test was performed at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1 at a potential range from 0.2 to −0.3 V vs. RHE at room temperature (25 °C). Potentiostatic tests were conducted at different potentials for 1 h, with a stirring rate of 1500 r.p.m. at room temperature (25 °C). After electrolysis, the electrolyte was analyzed by UV–Vis spectrophotometry. Electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) was assessed using cyclic voltammetry in a non-Faradaic region (−0.45 to −0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl) at different scan rates of 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 mV s−1. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) tests were conducted in a frequency range of 0.01 Hz–100 kHz at open circuit potential (−0.036 V vs. RHE) in an electrolyte containing 0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH, and 200 ppm of NO3−-N.

Determination of NO3 −-N concentration

NO3−-N concentration was determined using UV–Vis spectrophotometry. Initially, 100 μL of cathodic electrolyte were extracted and diluted to a total volume of 10 mL. Then, 200 μL of HCl (1 M) were incorporated to the above solution. Using UV–Vis spectrophotometry, the absorption intensities at wavelengths of 220 nm (A220nm) and 275 nm (A275nm) were recorded. The absorbance value (A) was determined employing the equation: A = A220nm−2 × A275nm. The UV–Vis absorbance spectra of standard NO3−-N solutions with known concentrations were measured for calibration, resulting in the calibration equation: y = 0.110x + 0.031 with an R2 value of 0.999.

Determination of NH4 +-N concentration

The indophenol blue method was employed to quantify NH4+-N concentration. Initially, 40 μL of cathodic electrolyte were obtained and diluted to a total volume of 4 mL. Subsequently, 4 mL of chromogenic agent composed of 1.0 M NaOH, 0.36 M C7H6O3, and 0.17 M C6H5Na3O7·2H2O, 2 mL of NaClO (0.05 M), and 0.4 mL of complexing agent (1 wt% Na2[Fe(NO)(CN)5]·2H2O) were sequentially introduced into the aforementioned solution. Following 1 h’s incubation, UV–Vis absorbance spectra were acquired, and the absorbance at 655 nm was recorded. The UV–Vis spectra of standard NH4+-N solutions with known concentrations were measured for calibration, resulting in the calibration equation: y = 0.459x + 0.032 with an R2 value of 0.998.

Determination of NO2 −-N concentration

Initially, 50 μL of cathodic electrolyte were extracted and diluted to a total volume of 5 mL. Subsequently, 0.1 mL of color reagent composed of 12.9 mM C12H14N2·2HCl, 0.38 M C6H8N2O2S and 2.87 M H3PO4, were added to the above solution. Following 10 min’s incubation, UV–Vis absorbance spectra were acquired, and the absorbance at 510 nm was recorded. The UV–Vis spectra of standard NO2−-N solutions with known concentrations were measured for calibration, resulting in the calibration equation: y = 0.370x + 0.001 with an R2 value of 0.998.

Determination of N2H4-N concentration

N2H4-N concentration was determined by the Watt and Chrisp method. Initially, a colorimetric reagent was prepared by dissolving 5.99 g C9H11NO (0.01 mol) in a mixture of HCl (30 mL) and ethanol (300 mL). Subsequently, 5 mL of cathodic electrolyte were extracted and combined with 5 mL of the prepared color reagent. Following 10 min’s incubation at room temperature, UV–Vis absorbance spectra were acquired, and the absorbance at 455 nm was recorded. The UV–Vis spectra of standard N2H4-N solutions with known concentrations were tested for calibration, resulting in the calibration equation: y = 0.773x + 0.026 with an R2 value of 0.997.

Performance evaluation

To calculate NO3− conversion (\({C}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}}\)), Eq. (2) is used as follows:

where \({c}_{0}\) represents the initial concentration of NO3−-N in electrolyte, \({\Delta c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) stands for the variation in the concentration of NO3−-N before and after electrolysis.

To calculate NH3 selectivity (\({S}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)), Eq. (3) is used as follows:

where \({\Delta c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the variation in the concentration of NO3−-N before and after electrolysis, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) stands for the concentration of \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}-{{\rm{N}}}\) after electrolysis.

To calculate NH3 yield rate (\({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)), Eq. (4) is employed as below:

where \({c}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) stands for the concentration of NH3 after electrolysis, V is the cathodic electrolyte volume, t represents the reduction time, S is the geometric area of the working electrode.

To calculate NH3 Faradaic efficiency (\({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)), Eq. (5) is used as follows:

where F stands for the Faradaic constant (96,485 C mol−1), \({c}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) is the concentration of NH3 after electrolysis, V is the cathodic electrolyte volume, and Q is the total charge that has passed through the electrode.

To calculate NO2− yield rate (\({Y}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}}\)), Eq. (6) is employed as follows:

where \({c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}}\) stands for the concentration of NO2− after electrolysis, V represents the cathodic electrolyte volume, t is the reduction time in h, and S is the geometric area of the working electrode.

To calculate NO2− selectivity (\({S}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}}\)), Eq. (7) is used as follows:

where \({\Delta c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the variation in the concentration of NO3−-N before and after electrolysis, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the concentration of NO2−-N after electrolysis.

To calculate NO2− Faradaic efficiency (\({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}}\)), Eq. (8) is used as follows:

where F stands for the Faradaic constant, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}}\) is the concentration of NO2− after electrolysis, V is the cathodic electrolyte volume, Q is the total charge that has passed through the electrode.

N2 selectivity (\({S}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}_{2}}\)) is obtained by the subtraction method (Eq. 9), as only the N-containing products of NO2−, N2, and NH3 can be detected during the NO3RR process.

where \({\Delta c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the variation in the concentration of NO3−-N before and after electrolysis, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{2}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the concentration of NO2−-N after electrolysis, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the concentration of \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}-{{\rm{N}}}\) after electrolysis.

To calculate N2 Faradaic efficiency (\({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}_{2}}\)), Eq. (10) is used as follows:

where F is the Faradaic constant (96485 C mol−1), \({\Delta c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the variation in the concentration of NO3−-N before and after electrolysis, V is the cathodic electrolyte volume, Q is the total charge that has passed through the electrode.

H2 was detected by the gas chromatograph (GC, A91 Plus PANNA) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The gas effluent from the cathodic chamber was directly delivered into the gas sampling loop of GC. H2 Faradaic efficiency (\({{{\rm{FE}}}}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}}\)) is calculated using the following Eq. (11)36:

where F is the Faradaic constant (96,485 C mol−1), \({V}_{{{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}}\) is the volume concentration of H2 in the exhausted gas from cathodic chamber at a given sampling time (vol%), G is total gas flow rate at room temperature and ambient pressure (20 L min−1), \(t\) is the electrolysis time, \({P}_{0}\) is the gas pressure (1.013\(\times {10}^{5}\) Pa), R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), T is the temperature (298 K), and Q is the total charge that has passed through the electrode during the NO3RR process.

To calculate NH3 partial current density (\({j}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)), Eq. (12) is employed as follows:

where Q is the total charge that has passed through the electrode, t is the reduction time, and S stands for the geometric area of the working electrode.

The half-cell energy efficiency (\({{{\rm{EE}}}}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)) determined by the ratio of fuel energy to the electrical power applied, is calculated using Eq. (13) as follows:

where \({E}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}^{0}\) is the equilibrium potential of the NO3RR process (0.69 V), E stands for the applied potential.

To calculate energy consumption (EC), Eq. 14 is employed as follows:

where E stands for the applied potential, i represents the current, t is the reduction time, \(m\) is the mass of produced NH3 after electrolysis.

To calculate NH3 production cost, Eq. (15) is employed as below:

where EC stands for the energy consumption, 0.03 ($USD kWh−1) is the full levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for utility solar power according to the recent announcement by the US Department of Energy (DOE) for the 2030 target23,37. Note that this is a simplified calculation method that solely considers the electrical price without taking into account the capital costs and Ohmic losses.

Calculation of ECSA and ECSA-normalized \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)

To calculate ECSA, Eq. (16) is used as follows:

where Cs refers to the specific capacitance of a flat metallic surface38, with a value of 40 μF cm−2. Cdl is the double-layer capacitance, which can be derived from cyclic voltammetry (CV) performed within the non-Faradaic potential range at different scan rates (10–60 mV s−1). The calculation of Cdl is based on Eq. (17) as follows:

where ia and ic represent the anodic and cathodic current at a certain potential, respectively, ν is the scan rate of CV.

ECSA-normalized \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) is calculated using Eq. (18) as follows:

where V stands for the cathodic electrolyte volume, t is the reduction time, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) is the concentration of NH3 after electrolysis.

Calculation of BET surface area-normalized \({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\)

\({Y}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) is normalized to BET surface area according to the following Eq. (19):

where V stands for the cathodic electrolyte volume, t represents the reduction time, \({c}_{{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}}\) is the concentration of NH3 after electrolysis. BET surface area is obtained by N2 adsorption-desorption method.

In situ Raman measurement

Gamry Refence 3000 coupled with an iRaman instrument equipped with a 532 nm laser was employed for in situ Raman measurement. A self-made cell featuring a three-electrode configuration was employed. The electrolyte contained 0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH, and 200 ppm NO3−-N. All Raman spectra were acquired during chronoamperometric experiments.

In situ ATR-SEIRAS measurement

For in situ ATR-SEIRAS measurements, hcp-Ru1Co was supported on an Au-coated Si crystal substrate as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl and Pt foil functioned as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. During chronoamperometry experiments at various potentials, spectral data were collected. The electrolyte contained 0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH, and 200 ppm NO3−-N.

Online DEMS measurement

For online DEMS measurements, a peristaltic pump was utilized to continuously flow the electrolyte (0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH, and 200 ppm NO3−-N) into a custom-made electrochemical cell, in which hcp-Ru1Co loaded on glassy carbon electrode served as the working electrode, while Pt wire and Ag/AgCl were used as the counter and the reference electrodes, respectively. Ar gas was bubbled into the electrolyte constantly before and during the DEMS measurement. The gaseous products generated from the working electrode were brought into a mass spectrometer through a hydrophobic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane (porosity ≥50%, pore diameter ≤20 nm). Chronoamperometry test at 0 V was carried out for 150 s. Once the test was completed and mass signals recovered to their initial levels, the subsequent cycle was initiated under identical conditions. Following four cycles, the measurement was finished.

Isotope labeling experiments

Isotopic labeling experiments utilized Na15NO3 (98.5 wt%) as the nitrogen source. The post-electrolysis electrolyte was extracted and adjusted to pH 4 using H2SO4. For 1H NMR test, 1 mL of D2O with 4.4 mg of C4H4O4 was incorporated into 10 mL of the above solution. The 1H NMR spectra of standard 15NH4+ solution with known concentrations were measured for calibration, resulting in the calibration equation: y = 0.016x−0.034 with an R2 value of 0.997.

NO3 - adsorption and FT-IR experiments

To ascertain the adsorption capacities of NO3−, Ru1Co SAAs (10 mg) were immersed in 10 mL of an electrolyte comprising 0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH, and 200 ppm NO3−-N. After stirring for 30 min, the adsorption capacity (qe) is determined using Eq. (20) as follows:

where qe stands for the adsorption capacity, \({\Delta c}_{{{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}-{{\rm{N}}}}\) is the variation in the concentration of NO3−-N before and after stirring, V is the electrolyte volume, m is the mass loading amount of Ru1Co SAAs.

The Ru1Co SAAs with absorbed NO3− underwent sequential washing with deionized water, centrifugation, and drying. Finally, they were analyzed using FT-IR spectroscopy.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Vienna ab-initio Simulation Package software39,40. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation function was used, and projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudo-potentials were used to model ion-electron interactions41,42,43. A plane-wave cutoff energy basis set with a cutoff energy of 450 eV was applied. To account for van der Waals forces, the DFT-D3 method was employed44,45. Structural relaxations utilized a Monkhoest–Pack k-point grid of 2 × 2 × 1, with convergence thresholds set to an energy tolerance of 10−5 eV and force below 0.05 eV Å−1. A 15 Å vacuum region was introduced along the z-axis. The free energy change (ΔG) of the reaction pathway was determined using Eq. 21 as follows:

where ΔE, ∆ZPE, and ∆S are the variations in the reaction energy, zero-point energy change, and entropy change, respectively, T stands for the temperature.

Rechargeable Zn-NO3 − battery measurements

For the rechargeable Zn-NO3− battery tests, an H-cell setup with a Nafion 211 membrane as the separator was used. The anode compartment contained 2 M KOH as the electrolyte, while the cathode compartment utilized a solution of 0.5 M Na2SO4, 0.1 M NaOH, and 200 ppm NO3−-N. A polished Zn plate with a geometric area of 0.5 cm2 served as the anode, and the cathode employed NF anchored with hcp-Ru1Co.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lin, L. et al. Low-temperature hydrogen production from water and methanol using Pt/α-MoC catalysts. Nature 544, 80–83 (2017).

He, T. et al. Mastering the surface strain of platinum catalysts for efficient electrocatalysis. Nature 598, 76–81 (2021).

Ge, J. et al. Ultrathin amorphous/crystalline heterophase Rh and Rh alloy nanosheets as tandem catalysts for direct indole synthesis. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006711 (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Heterophase intermetallic compounds for electrocatalytic hydrogen production at industrial-scale current densities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 20594–20603 (2024).

Nguyen, Q. N. et al. Elucidating the role of reduction kinetics in the phase-controlled growth on preformed nanocrystal seeds: a case study of Ru. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12040–12052 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. New twinning route in face-centered cubic nanocrystalline metals. Nat. Commun. 8, 2142 (2017).

Han, Z.-K. et al. Single-atom alloy catalysts designed by first-principles calculations and artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 12, 1833 (2021).

Zhang, T., Walsh, A. G., Yu, J. & Zhang, P. Single-atom alloy catalysts: structural analysis, electronic properties and catalytic activities. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 569–588 (2021).

Bunting, R. J., Wodaczek, F., Torabi, T. & Cheng, B. Reactivity of single-atom alloy nanoparticles: modeling the dehydrogenation of propane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 14894–14902 (2023).

Liu, W. et al. Highly-efficient RuNi single-atom alloy catalysts toward chemoselective hydrogenation of nitroarenes. Nat. Commun. 13, 3188 (2022).

Kaiser, S. K. et al. Single-atom catalysts across the periodic table. Chem. Rev. 120, 11703–11809 (2020).

He, C. et al. Single-atom alloys materials for CO2 and CH4 catalytic conversion. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311628 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Co-catalytic metal-support interactions design on single-atom alloy for boosted electro-reduction of nitrate to nitrogen. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2406917 (2024).

Yue, J., Li, Y., Yang, C. & Luo, W. Hydroxyl-binding induced hydrogen bond network connectivity on Ru-based catalysts for efficient alkaline hydrogen oxidation electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202415447 (2025).

Fan, L. et al. High entropy alloy electrocatalytic electrode toward alkaline glycerol valorization coupling with acidic hydrogen production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7224–7235 (2022).

Kim, C. et al. Atomic-scale homogeneous Ru–Cu alloy nanoparticles for highly efficient electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2205270 (2022).

Hao, J. et al. Unraveling the electronegativity-dominated intermediate adsorption on high-entropy alloy electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 13, 2662 (2022).

Qiu, J.-Z. et al. Pure siliceous zeolite-supported Ru single-atom active sites for ammonia synthesis. Chem. Mater. 31, 9413–9421 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Atomically dispersed Ru catalyst for low-temperature nitrogen activation to ammonia via an associative mechanism. ACS Catal. 10, 9504–9514 (2020).

Sarma, B. B. et al. Tracking and understanding dynamics of atoms and clusters of late transition metals with in-situ DRIFT and XAS spectroscopy assisted by DFT. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 3032–3046 (2023).

Ji, K. et al. Electrocatalytic hydrogenation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural promoted by a Ru1Cu single-atom alloy catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209849 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. A single site ruthenium catalyst for robust soot oxidation without platinum or palladium. Nat. Commun. 14, 7149 (2023).

Chu, S., Cui, Y. & Liu, N. The path towards sustainable energy. Nat. Mater. 16, 16–22 (2017).

Miller, D. M. et al. Engineering a molecular electrocatalytic system for energy-efficient ammonia production from wastewater nitrate. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 5691–5705 (2024).

Han, S. et al. Ultralow overpotential nitrate reduction to ammonia via a three-step relay mechanism. Nat. Catal. 6, 402–414 (2023).

MacFarlane, D. R. et al. A roadmap to the ammonia economy. Joule 4, 1186–1205 (2020).

Gu, Z. et al. Coordination desymmetrization of copper single-atom catalyst for efficient nitrate reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409125 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Constructing molecule-metal relay catalysis over heterophase metallene for high-performance rechargeable zinc-nitrate/ethanol batteries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2311149120 (2023).

Chu, K. et al. Cation substitution strategy for developing perovskite oxide with rich oxygen vacancy-mediated charge redistribution enables highly efficient nitrate electroreduction to ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 21387–21396 (2023).

Liu, Y., Ma, J., Huang, S., Niu, S. & Gao, S. Highly dispersed copper-iron nanoalloy enhanced electrocatalytic reduction coupled with plasma oxidation for ammonia synthesis from ubiquitous air and water. Nano Energy 117, 108840 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Phase engineering of high-entropy alloy for enhanced electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407589 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Transition metal gallium intermetallic compounds with tailored active site configurations for electrochemical ammonia synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202409515 (2024).

Hu, Q. et al. Ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate using a ruthenium−copper cocatalyst system: A full concentration range study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 668–676 (2024).

Wang, H., Dekel, D. R. & Abruña, H. D. Unraveling the mechanism of ammonia electrooxidation by coupled differential electrochemical mass spectrometry and surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 15926–15940 (2024).

Ma, C. et al. Screening of intermetallic compounds based on intermediate adsorption equilibrium for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 20069–20079 (2024).

An, B. et al. Liquid nitrogen sources assisting gram-scale production of single-atom catalysts for electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205639 (2023).

Xia, C. et al. Confined local oxygen gas promotes electrochemical water oxidation to hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Catal. 3, 125–134 (2020).

Nairan, A., Feng, Z., Zheng, R., Khan, U. & Gao, J. Engineering metallic alloy electrode for robust and active water electrocatalysis with large current density exceeding 2000 mA cm−2. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401448 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Klimeš, J., Bowler, D. R. & Michaelides, A. Van Der Waals density functionals applied to solids. Phys. Rev. B 83, 195131 (2011).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Qilu Young Scholarship Funding of Shandong University. This work is also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22005176 to A.-L.W., 92061119 to Q.L., 22305138 to Y.-C.W., 22302037 to C.-F.L.), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020QE014 to A.L.W.), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20200228 to A.L.W.), Innovative Team Project of Jinan (202228063 to A.-L.W.), Carbon Neutrality Research Institute Fund (CNIF20230203 to A.-L.W., CNIF20220206 to S.Y.), the Beijing NOVA program (Z201100006820066 to Q.L., 20220484172 to Q.L.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (GJRC003 to Q.L.), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Nos. 2022A1515140051 Q.L., 2023A1515140158 to C.-F.L.), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20231203 to Y.-C.W.), and the Shuimu Scholar from Tsinghua University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.-L.W. and Q.L. proposed the overall research direction and guided the project. A.-L.W., Q.L., and X.Z. conceived and designed the experiments, synthesized the materials, performed the electrochemical measurements, and drafted the manuscript. Y.-C.W. conducted the aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM characterizations. K.Q. and S.Y. carried out the theoretical calculations. L.S., J.W., Y.G., X.L., and C.-F.L. provided valuable discussions and suggestions. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Emma Lovell, Jianping Yang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Wang, YC., Qu, K. et al. Modulating Ru-Co bond lengths in Ru1Co single-atom alloys through crystal phase engineering for electrocatalytic nitrate-to-ammonia conversion. Nat Commun 16, 5742 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61232-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61232-z

This article is cited by

-

Real space characterizations of catalysts by advanced transmission electron microscopy

Science China Chemistry (2026)