Abstract

Generating molecular structures towards desired properties is a critical task in computer-aided drug and material design. As special 3D entities, molecules inherit non-trivial physical complexity, and many intrinsic properties may not be learnable through pure data-driven approaches, hindering the transaction of powerful generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) to this field. To avoid existing molecular GenAI’s heavy reliance on domain-specific models and priors, in this research, we derive theoretical guidelines to bridge the methodological gap between GenAI for images and molecules, allowing pre-training of foundation models for 3D molecular generation. Difficulties due to symmetry, stability and entropy, which are critical for molecules, are overcome through a simple and model-agnostic training protocol. Moreover, we apply physics-informed strategies to force MolEdit, a pre-trained multimodal molecular GenAI, to obey physics laws and align with contextual preferences, and thus suppress undesired model hallucinations. MolEdit can generate valid molecules with comprehensive symmetry, strikes a better balance between configuration stability and conformer diversity, and supports complicated 3D scaffolds which frustrate other methods. Furthermore, MolEdit is applicable for zero-shot lead optimization and linker design following contextual and geometrical specifications. Collectively, as a foundation model, MolEdit offers flexibility and developability for AI-aided editing and manipulation of molecules serving various purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The computer-aided design of functional molecules, such as those related to materials and drugs, has gained increasing interest in both scientific and industrial communities1,2,3,4. A central concept in functional molecule design is molecular editing, which encompasses the generation, modification and evolution of molecules towards desired properties with specific structural features. As a common demand during drug design, the alteration or optimization of a lead compound is often required to enhance its potential activity and suitability for development into better drug candidates5,6,7. However, such function-oriented molecular editing can be challenging due to the non-linear constrained optimization problem it presents within the vast chemical space. Consequently, conventional in-silico lead optimization typically involves resource-intensive screening in a trial-and-error manner and relies on specific expert knowledge8,9,10.

Recent advances in diffusion-based GenAI11,12 have made significant progress in the field of image editing. Particularly, in computer vision (CV), scalable GenAIs built upon converged architectures13,14, usually termed as foundation models, have pushed the boundaries of applications such as text-to-image generation, image inpainting, compositing, and style transfer, etc.15,16,17. The success of GenAI in image processing demonstrates the potential for applying well-established generative learning algorithms to molecular sciences, offering promising solutions to the challenges of molecular editing. Unfortunately, these powerful GenAIs cannot be applied directly to molecular generation, since, unlike images, 3D molecular entities are strictly constrained by intrinsic physical and chemical principles. Particularly, in addition to trans-rotational equivariance which is known to cause incompatibility with modern foundational model architecture18,19, molecules also exhibit ubiquitous and property-determining symmetries embedded within various point groups20. To combat these challenges, many researchers are developing domain-specific GenAIs for molecules, compromising the scalability or compatibility with existing foundation models. These attempts are mostly focused on designing new model architectures based on domain-specific priors and assumptions, and diverge significantly from the mainstream GenAI which has largely converged. Such a gap in technical momentum not only induces incompatibility with the rapid progress brought by mainstream GenAI, but also obstacles the transaction of well-established GenAI methodologies into molecular science.

Aiming at a more general approach and to keep with the momentum of foundational GenAI, we develop here a methodology that allows reuse of GenAI models for molecules with full compatibility. Particularly, we find that such compatibility can be readily achieved via a simple reformulation of training labels for vanilla denoising diffusion models11,12,21. Noteworthy, this process is non-invasive, introducing merely a plug-and-play modification to the training protocol of denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) during pre-processing, thus, can be executed efficiently in practice. Orthogonal to existing methods, our approach does not depend on either the choice of model architecture (i.e., being model-agnostic) or domain-specific priors, thus, can benefit from any technical progress of mainstream DDPMs.

Based on the unified methodology, we further split the training of scalable molecular GenAI into pre-training and fine-tuning phases, parallel to existing foundation models. Specifically, pre-training over large amounts of available molecular data endows scalable models with emerging capabilities. Inspired by the success of Text2Image GenAI13,22, we perform multimodal pre-training through a decomposition of molecular representations. Moreover, similar to other foundation models, hallucinations of molecular GenAI are also ubiquitous23, but are mostly ignored by existing methods or ameliorated post hoc24,25. In this work, we underscore several types of common hallucinations of existing molecular GenAIs, and address them through preference alignment with respect to physics oracles and AI feedback26,27,28, and allow the model to benefit from inference-time self-improvement.

Assembling these advances collectively, we obtain MolEdit, a multimodal molecular GenAI which combines physics-informed and data-driven learning to effectively model the distribution of 3D molecular structures. Being compatible with mainstream GenAI, MolEdit inherits the scalability of foundation models, and is pre-trained over large amounts of molecular data subjected to 3D molecular reconstruction, an unsupervised objective for molecular AI. Through experiments, we show that, as a foundation model, MolEdit can be adapted to multiple downstream generative tasks with or without fine-tuning. In addition to the de novo design of functional molecules, MolEdit is capable of producing diverse, high-quality structures of textual molecular representations. It also facilitates molecular scaffold modifications, including the redesign of functional groups, linkers, and pharmacophores, along with structural edits such as inpainting, outpainting, and compositing. Overall, MolEdit not only offers a versatile in silico approach for molecular editing, but also provides a unique perspective for adapting mainstream AI techniques to domain-specific challenges.

Results

We begin with a concise overview of the rationale and methodologies developed for our molecular GenAI framework, with full details provided in the “Methods” and Supplementary Methods. In the following two sections, we validate the effectiveness of our proposed techniques by training a symmetry-aware DDPM (MolEdit) with group-optimized (GO) labeling and by mitigating hallucinations through physics-informed preference alignment. Building on these advances, we demonstrate MolEdit’s ability to render structures from textual molecular representations, edit functional molecules, and design protein binders by imprinting known lead compounds. We also present a practical example of designing selective inhibitors by integrating GenAI with traditional pharmacophore analysis to demonstrate the flexibility and versatility of MolEdit.

In addition to the results presented in the main text, Supplementary Discussion 2.1–2.2 provide detailed experimental setups, 2.4–2.8 discuss extended experiments on MolEdit’s robustness and diversity, 2.9 covers further applications through fine-tuning for property-guided sampling, and 2.10–2.11 describe two quantitative benchmarks in different tasks.

Scaling up 3D molecular diffusion models under physics principles

Unlike SMILES29,30,31,32 or graph-based33,34,35 approaches, we leverage 3D atomic coordinates as a unified representation of both isomeric and conformational variations. This shift eliminates ambiguities inherent in discrete representations (e.g., multiple degenerate SMILES or graph encodings for a single molecule, Fig. 1a, b) while offering a direct route to modeling continuous chemical and conformational spaces (Fig. 1c, see “Methods” for more details about pros and cons of different molecular representations). However, 3D coordinates introduce additional complexity due to the need to handle translation, rotation, and intramolecular symmetry operations—factors that can be machine-unfriendly yet are essential for accurately capturing the nature of molecular systems (Fig. 1d)18,19,24.

a A single structure can correspond to multiple molecular graphs, which represent resonance forms or tautomers. The same molecular graph may correspond to degenerate SMILES strings; the corresponding canonical SMILES are highlighted in bold. b Similar molecular graphs may map to significantly different SMILES strings; a slight displacement of a methyl group results in a Levenshtein distance of 23 in the SMILES strings. c Conformers and isomers can be unified by representing different relative positions of atoms in coordinate spaces. d Illustration of the SE(3) and permutation symmetry of molecular structures. With known molecular graphs, the permutation symmetry of a molecule is related to the elements in the molecular point group (right panel).

To address the symmetry constraints of 3D atomic coordinates, we adopt an asynchronous multimodal diffusion (AMD) schedule that decouples the diffusion of molecular constituents from that of atomic positions (Fig. 2a), resulting in a two-stage generation strategy which probabilistically decomposed the discrete and continuous variables in molecules (Fig. 2b). This approach prevents the combinatorial explosion that arises when all atoms are diffused simultaneously without accounting for their equivalences, especially as the model scales to larger molecules. Moreover, we develop a non-invasive group-optimized (GO) labeling strategy, which reformulates the training labels of a standard DDPM11,12 to respect translational, rotational, and permutation symmetries. Because we only adjust how labels are generated rather than modifying the model itself, GO labeling remains model-agnostic and incurs minimal overhead (see “Methods” for more details of AMD schedule and GO labeling). This strategy effectively reduces degeneracy caused by symmetries, ensuring that the learned diffusion process is both efficient and symmetry aware.

a The synchronous diffusion process that jointly diffuses constituents and structures (middle panel) with two asynchronous limits: in the forward process, constituents are diffused first, resulting in a structured point cloud, followed by the diffusion of the structure (up panel); alternatively, the structure is diffused first, leading to unstructured constituent sets, followed by the diffusion of constituents (down panel). b The basic workflow of MolEdit. Following the probabilistic decomposition \(P\left({{\rm{mol}}}\right)=\int {P}_{S}\left({{\bf{s}}}\right){p}_{{X|S}}({{\bf{x}}}|{{\bf{s}}}){{\rm{d}}}{{\bf{x}}}\), MolEdit first generates constituents \({{\bf{s}}}\) using the constituent model, then conditionally generates structures \({{\bf{x}}}\) given \({{\bf{s}}}\), and finally assembles the molecular graph from constituents \({{\bf{s}}}\) and structures \({{\bf{x}}}\). \(P\left({{\rm{mol}}}\right)\), \({P}_{S}\left({{\bf{s}}}\right),{p}_{{X|S}}({{\bf{x}}}|{{\bf{s}}})\) represent the probability distribution of molecules, constituents, and conditional probability density of structures given constituents respectively. c Illustration of molecules generated by MolEdit trained on three different datasets, QM939, ZINC40,41,42 and QMugs43.

Despite accurately capturing the symmetries of molecules, purely data-driven methods can still produce physically hallucinated structures (e.g., atom clashes, unrealistic angles)24,36. We address this issue by incorporating a Boltzmann-Gaussian Mixture (BGM) kernel, which aligns the diffusion process with physical constraints such as force-field energies (See Methods for construction details of BGM kernels)37,38. This integration resembles preference alignment in other generative AI systems but uses a physics critic for guiding molecular structures. The approach adds a Boltzmann factor to the forward diffusion transitions, emphasizing physical criteria like free energy. Consequently, our model prioritizes more realistic configurations during training and inference, mitigating the need for extensive post hoc corrections.

By combining 3D representation, symmetry-awareness through AMD and GO labeling, and physics alignment via the BGM kernel, we achieve a flexible generative framework for molecular editing and design (Fig. 2b). Our 3D diffusion model scales effectively from small molecules in QM939 (up to 9 heavy atoms) and medium-sized drug-like compounds in ZINC40,41,42 (up to 64 heavy atoms) to large, bioactive molecules in QMugs43 (up to 100 heavy atoms). Throughout these scales, the model maintains robust validity and stability in generated structures (Fig. 2c), demonstrating its potential as a foundation for physics-informed molecular generation across diverse chemical and conformational spaces.

Group-optimized diffusion preserves molecular symmetries

Molecules exhibit rich symmetries, including translational, rotational, and permutation invariance, as well as symmetries embedded within various point groups. These symmetries are ubiquitous and closely tied to molecular properties, such as vibrational modes and absorption spectra, and influence their interactions with other chemical species, including metal ions, solvents and host molecules. However, current molecular GenAIs often overlook these symmetries. For instance, as discussed in “Methods” and Supplementary Methods 1.1, diffusion-based molecular GenAIs typically model a synchronous diffusion process for constituents and structures (Fig. 2a). This approach complicates the rigorous definition of atom equivalence and, consequently, the determination of the corresponding molecular permutation symmetry, which is closely associated with the molecule’s point group (Supplementary Methods 1.5). To determine whether existing methods are truly symmetry-aware, we curated a dataset from the ZINC database40,41,42 containing molecules with rich symmetry elements (details are available at Supplementary Discussion 2.1). Based on this dataset, we re-trained a baseline E(3) equivariant diffusion model (EDM)24 following the reported settings where constituents and coordinates are diffused jointly, alongside a MolEdit model of similar size trained upon GO labels following an AMD schedule. To assess to which extent these models are characteristic of the molecular symmetries present in the training data, we conducted adversarial purification experiments44: The molecules are first subjected to attacks by the model-specific forward diffusion kernel till a certain noise level, and then restored by the backward kernels learned by the model. Figure 3a illustrates how the purified molecular symmetries vary with different noise scales used in the attack process. Although molecular structures are blurred with noise, thus, gradually losing symmetries during the attacks, a model fit on the dataset comprising highly symmetric molecules is expected to restore or re-create as many symmetry elements as possible after purification, so that the distribution of the purified molecules is consistent with the training data.

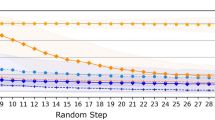

a Illustration of the adversarial purification experiments used to assess the symmetry awareness of the models. A molecule with rich symmetries is initially attacked by a model-specific forward diffusion process, during which its symmetries are gradually lost due to blurring with white noise, and then restored by the backward diffusion process learned by the model. A model trained on a dataset which contains high-symmetry molecules is expected to restore as many symmetry elements as possible after the backward diffusion process. The upper panel corresponds to the asynchronous multimodal diffusion schedule (as in MolEdit), and the lower panel corresponds to the synchronous diffusion schedule (as in the baseline E(3) equivariant diffusion model, EDM24). b The loss of symmetries (the decreased number of symmetry elements after adversarial purification experiments, normalized with respect to the original molecules) varies across different forward attack diffusion time steps of MolEdit and EDM model. For each noise scale, we sampled 1024 forward and backward diffusion processes. Data are shown as median, with error bars representing the first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3). c MolEdit produces physically valid molecules with high symmetry in alignment with the dataset distribution. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To quantify the model’s robustness in terms of molecular symmetries, we defined loss of symmetries as the decreased number of symmetry elements (normalized with respect to the original molecules) in the attack-purification process. We find that compared to EDM, MolEdit consistently yields more symmetric molecules during purification of the attacks, even when a relatively large attack magnitude (i.e., large noise scale) is applied (Fig. 3b). Noteworthy, this improvement of symmetry awareness is obtained almost for free based on GO labeling, without symmetric-specific modifications to the models or priors. Moreover, we find evidence that taking symmetry into account during training also boosts model generalization. For instance, trained on ZINC dataset, MolEdit generates molecules with a higher validity (90.5%) compared to EDM (57.8%) and can produce high-symmetry molecules that conform to the dataset distribution (Fig. 3c).

Preference alignment suppresses hallucinations of generated molecules

As a critical evaluation metric, the validity of generated molecules is benchmarked by many molecular GenAIs. However, existing methods can only attribute the improved validity to their model design or dataset, and cannot further improve this metric after training. In our experiments, by virtue of AMD, the invalidity of generated molecules is equivalent to a special type of condition violations, thus, can be addressed by means of hallucination suppression (see “Methods” for details). Specifically, aiming to improve validity, conditioned on molecular constituents (sampled from constituent priors; see “Methods” and Supplementary Methods 2.9 for more details), we fine-tuned MolEdit using standard preference alignment method45, encouraging the model to generate valid molecules and penalize inconsistent ones. We performed experiments on the QM9 dataset39, and compared our methods with respect to EDM and other baseline models. It can be found in Supplementary Table 2 that, compared to baselines, the fine-tuned MolEdit is very competitive in producing valid molecules when taking hydrogen atoms into account. Furthermore, we also experimented with post-training strategies to suppress the generation of invalid molecules. Specifically, independent of MolEdit, we trained a surrogate critic model to predict whether an intermediate configuration in backward diffusion will finally lead to a valid molecule (Supplementary Methods 1.12). Using this surrogate critic model as a classifier, we can conduct oracle-assisted guidance27 to further increase the validity of generated molecules (Supplementary Methods 1.12 and Supplementary Table 2). This guidance provides a model-agnostic and training-independent solution to specifically improving the validity of molecular GenAIs, which is in principle also applicable to other molecular GenAIs.

On top of validity, which is usually evaluated on the topology heuristically, one more essential assessing metric of 3D molecular GenAIs is the stability of generated 3D molecular configuration or conformation. Due to constraints of quantum mechanics, molecules are known to be brittle in the perturbation of atomic positions. A subtle change of atomic positions may lead to dramatic transition of molecular stability (such as bond breakage). Therefore, we underscore the importance of evaluating the stability of generated 3D molecules in terms of physics, and propose molecular physics instability (MPI) to measure this type of hallucination. Specifically, MPI is defined as the average physics stress (norm of forces) experienced by each atom under an oracle physics Hamiltonian (or force field; detailed definition of MPI used in evaluation under general AMBER force field, GAFF38, and universal force field, UFF37, can be found in Supplementary Discussion 2.3).

Using MPI as the assessment metric, we compared different methods on the QM9 dataset, given that this dataset includes many molecules with substantial structural stress, posing a significant challenge for 3D molecular generation. Figure 4a displays the MPI distribution (under GAFF)38 for molecules generated using EDM, MolEdit with different solvers (including solvers based on annealed Langevin dynamics, ALD solvers11, and solvers based on high-order ordinary differential equations, DPM solvers46), and MolEdit with the BGM kernel, all trained on the QM9 dataset. MolEdit with default diffusion kernels produces molecules with higher MPI compared to EDM (Fig. 4a), likely due to smaller model size and truncation error introduced by higher-order ODE solvers. After fine-tuning with the BGM kernel, however, MolEdit’s MPI decreases sharply, relaxing unstable configurations and achieving lower MPI than both its vanilla version and EDM (Fig. 4a), even though it still uses a smaller model. Moreover, the BGM kernel at lower temperatures exhibits lower MPI values (Fig. 4b), indicating that the BGM kernel can effectively reduce instabilities in molecular structures (Fig. 4c). The successful application of the BGM kernel illustrates that high likelihood in a data-driven model does not necessarily equate to low energy and high physics stability, and that employing a physics-informed strategy can be beneficial.

a The distribution of Molecular Physics Instability (MPI) under the general AMBER force field38 for 10,000 molecules generated by the E(3) equivariant diffusion model (EDM)24, MolEdit with different solvers, and MolEdit with the Boltzmann-Gaussian mixture (BGM) kernel, all trained on the QM9 dataset. b The reduction in MPI when using the BGM kernel with different temperatures. Statistical distributions were derived from a sample of 10,000 molecules. Box plots in a, b are defined by the median as the center black line, first and third quartiles as the box edges and 1.5 times the interquartile range as the whiskers. c Application of the BGM kernel produces molecules with high physical stability. d MolEdit is utilized to sample diverse conformers for molecules with complex structures, which is challenging for tools like RDKit47. e Distributions of diversity and physical stability (under universal force field)37 of conformers sampled by GeoDiff36, MolEdit, MolEdit with FPS solver, and RDKit on the GeoDiff test set (1024 conformations for each molecule, 1000 molecules in total). f MolEdit constructs structures with constrained cyclohexane rings in twist-boat or chair conformations and double bonds in E or Z conformations. Structures of highlighted areas are constrained during generation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

3D rendering of textual molecules with high quality and diversity

In textbooks or databases, molecules are represented or stored in compact textual representations such as SMILES and graphs. Generating 3D structures according to 1D SMILES or 2D molecular graphs and exploring the conformational space of molecules is crucial for structure-based applications in molecular science. The distribution of structures is closely associated with kinetic as well as thermodynamic properties of molecules, such as entropies and free energies. Structures of molecules form fundamental ingredients of microscopic interactions, thus influencing molecules’ reactivity and their communications with environments like solvents and proteins. However, leveling up to 3D structures from 1D and 2D representations requires complex inference of group arrangements, particularly for molecules with crowded substructures under high structural stress and large steric hindrance, where bonds are entangled and forced to adopt uncomfortable conformations. Furthermore, molecules often contain multiple highly flexible rotatable bonds, which expands an extensive structural space that poses a significant challenge to the model’s diversity. Traditional methods for generating conformers often rely on heuristic approaches that incorporate chemical intuition and empirical data. These methods generally fail to generalize to complex molecules, such as those with intricate ring structures. Figure 4d demonstrates that MolEdit, conditioned on molecular graphs, can sample diverse conformers for molecules that challenge tools like RDKit47, which frequently struggles with complex bicyclic rings.

To further assess the quality and diversity of the sampled conformers, we defined a metric based on the effective number of samplings to evaluate the conformational diversity (Supplementary Discussion 2.3). Figure 4e shows the distribution of MPI (under UFF)37 and conformational diversity of conformers sampled from GeoDiff36, RDKit, MolEdit, and MolEdit with Fokker Planck sampler (FPS, a sampler we developed to improve sampling diversity, more details are provided in Methods and Supplementary Methods 1.8) on molecules from the GeoDiff test set, which is derived from the GEOM-Drugs dataset48. The results indicate that although GeoDiff samples more diverse conformations, it includes many physically unreasonable structures. In contrast, MolEdit achieves a better balance between diversity and physical stability. Additionally, the FPS sampler, a self-improvement technique introduced by us to maximize conformational entropy in the backward diffusion process, enhances the sample diversity without compromising physical stability. It is noteworthy that although MolEdit was trained on a dataset with only a few (less than four) conformations per molecule, it is capable of generating more conformations during inference. This observation supports the presumption that conformers and isomers in 3D space can be described in a unified manner, and improves model generalization.

Besides freely sampling conformations, the manipulation of 3D structures within constrained conformational spaces is also of significant interest. This is particularly relevant when the relative positions and orientations of certain atoms are anchored based on specific constraints, such as experimentally resolved structures, necessary structural constraints for specific functions, or limitations imposed by external host environments. MolEdit has demonstrated its ability to inpaint compatible structures on rigidly constrained structure fragments15,16. In Fig. 4f, MolEdit successfully constructs structures when cyclohexane rings in molecules are constrained to adopt twist-boat or chair conformations, and when double bonds are constrained to E or Z conformations, showcasing its versatile structural editing capabilities in conformational space.

In-context functional molecular editing

Real-world applications, including fragment-based drug design49 and molecular optimization, often involve editing molecules within constraints defined by chemical languages, which specify essential information such as molecular fragments and functional groups. To demonstrate this concept, we generated molecules with different sizes of aliphatic rings as specified chemical conditions based on a set of constituents. Figure 5a illustrates that MolEdit successfully collapses the diffusion process into the chemical subspace consistent with the designated chemical conditions.

a MolEdit collapses the diffusion process into the chemical subspace which is consistent with specified chemical conditions, here shown with different sizes of aliphatic rings. b Editing and generation of various aromatic rings in molecules with conjugated systems. c New functional groups are designed and repositioned within a glycosylamine molecule, demonstrating MolEdit’s ability to manipulate molecular structures while preserving the core functional elements. d MolEdit designs diverse linkers connecting separate molecular fragments. e Scaffold hopping optimizes a inhibitor of adenylyl cyclase by converting a tricyclic ring (red, PDB ID: 5IV4) to a pyrazole ring (green), the unchanged atoms (gray) are anchored according to their binding pose, ensuring the new structure generated by MolEdit is superimposed with the binding structure of the original inhibitor (left panel). MolEdit also builds structures for further evolution of the hopped compound with R-group modifications (right panel). The blue and red highlighted regions in b–e indicate the retained and generated scaffolds of the molecules, respectively.

We further applied MolEdit to various scenarios with different chemical conditions. The core heteroaromatic ring plays a crucial role in the chemical properties of conjugated systems, such as the gap between highest occupied and lowest unoccupied orbitals, which is vital for materials involving charge transfer, including organic photoelectric and fluorescent materials50,51. In Fig. 5b, MolEdit is utilized to edit and generate different aromatic rings for molecules with conjugated systems, potentially altering their electron transfer properties. In Fig. 5c, while retaining the core of a glycosylamine, new groups are designed and migrated to different oxygen atoms in the glycosylamine via MolEdit. This capability of growing groups at arbitrary positions within a fragment enables MolEdit to design and optimize molecules while preserving key functional groups, which is valuable in drug design based on pharmacophores52,53. Similarly, MolEdit can be used to design linkers for two separate fragments. Figure 5d shows that the designed linkers are diverse and compatible with designated fragments, indicating MolEdit’s potential applications in fragment-based drug design and designing chemically induced proximity systems, such as proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTAC) complexes54. Moreover, even without additional training, MolEdit yields results comparable to those of specialized linker-design models (Supplementary Discussion 2.10).

Moreover, the ability to generate structures with parts rigidly fixed can benefit computational workflows related to molecular optimization, such as virtual screening using free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations55,56. In FEP, a molecule is mutated to multiple variants using scaffold hopping or R-group modifications, and the change in binding free energy with certain protein targets due to this mutation is calculated using molecular dynamics simulations. To initiate a FEP simulation, the mutated and the original molecule should overlap according to their maximum common substructure to mitigate potential bias introduced by improper initialization. In Fig. 5e, an inhibitor of adenylyl cyclase, LRE1, is optimized through scaffold hopping, converting a tricyclic ring to a pyrazole ring57 (PDB ID: 5IV4). We used MolEdit to construct hopped structures while anchoring the unchanged atoms according to their binding pose with adenylyl cyclase, thus ensuring the resulting structures perfectly fit into the original pockets with the same pose (Fig. 5e). The hopped compound is further evolved with R-group modifications, including converting a thiophene ring and adding modifications to the pyrazole ring57. Similarly, MolEdit can be utilized to modify the corresponding structures while maintaining the integrity of the scaffold (Fig. 5e).

Lead-imprinted binder design

In many protein-ligand binding systems, the compatibility of the shape between the ligand and the protein pocket is a critical determinant of their binding affinity58,59,60. As previously mentioned, both chemical space and conformational space share a unified perspective in coordinate representations. Therefore, MolEdit’s diffusion process, defined in coordinate space, facilitates exploration of the chemical space to design new ligands with potential binding capabilities. This process is guided by shapes that closely match those of known molecules binding to targets of interest. We condition the diffusion process in MolEdit on the radius of gyration (Fig. 6a), which, along with the number of atoms, largely determines the molecule’s rough shape, for example, indicating whether a molecule is linear or globular. For more precise shape information, we incorporate established molecular shape comparison tools as training-free guidance for the diffusion processes (Fig. 6a, details provided in Supplementary Method 1.13), such as ultrafast shape recognition descriptors58 and rapid overlay of chemical structures59, which are utilized to virtually screen large compound databases for similar molecular shapes.

a A shape-aware diffusion process is implemented, conditioned on the radius of gyration of molecules. Finer granularity in shape control can be achieved through integrating refined shape similarity scores based on established shape comparison tools. The equation presents the stochastic differential equation employed for lead-imprinted sampling of structure \({{\bf{x}}}\), where \(\nabla \log {p}_{\theta }\) denotes the parametrized score function (conditioned on radius of gyration \({r}_{{{\rm{g}}}}\)) in the diffusion model, \({S}_{{{\rm{shape}}}}\) represents the shape similarity score between \({{\bf{x}}}\) and the template molecule \({{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\rm{template}}}}\), and \({\widetilde{\sigma }{{\bf{w}}}}_{t}\) is a standard Brownian motion with variance \({\widetilde{\sigma }}^{{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}\). b The generated molecules exhibit shapes, docking poses, and binding affinities that are similar or superior to template molecules in protein-ligand complexes, including ALK with Lorlatinib (PDB ID: 5A9U), adenylyl cyclase with LRE1 (PDB ID: 5IV4), and JAK1 with Abrocitinib (PDB ID: 6BBU). c The crystal structure of a selective inhibitor bound to the PI3Kα-H1047R mutant (PDB ID: 8V8U), with the hydrogen bond between the ligand and Arg1047 highlighted (left panel). The right panel shows the docking poses of selected molecules generated by MolEdit, exhibiting high affinity for PI3Kα-H1047R and maintaining the hydrogen bond contact with Arg1047. The chemical group circled in blue was retained during generation. The numbers in the lower right corner of each structure indicate the corresponding docking affinities. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

This strategy has proven effective for several known protein-ligand complexes, including human Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase bound with the food and drug administration (FDA)-approved drug Lorlatinib (PDB ID: 5A9U), adenylyl cyclase with the allosteric inhibitor LRE1 (PDB ID: 5IV4), and human Janus Kinase 1 (JAK1) with the FDA-approved drug Abrocitinib (PDB ID: 6BBU). By constructing shape-aware diffusion processes, MolEdit is capable of generating molecules that resemble the shape of lead molecules. In subsequent docking calculations61, these molecules bind to the target proteins in a similar pose, and demonstrate binding affinity that is comparable or exceeds that of the template molecules (Fig. 6b). A further quantitative benchmark also shows that this “lead-imprinting” approach can produce molecules with binding affinities comparable to those from target-aware methods (Supplementary Discussion 2.11).

Building on lead-imprinting strategy of binder design, we further explored a system where selective inhibition hinge on a key pharmacophoric interaction. Specifically, we attempted to design selective inhibitors which targets the PI3K\(\alpha\) H1047R mutant, a variant implicated in breast cancers and solid tumors, while avoiding interference with the wild-type PI3Kα protein, which is critical for normal cellular function. Previous studies by Ketcham et al. identified several selective inhibitors and proposed that hydrogen bonds with the Arg1047 residue are pivotal for selective inhibition62. Huang et al. corroborated this mechanism by demonstrating through cryo-EM and molecular dynamics that these hydrogen bonds stabilize the activation loop in the H1047R mutant, thereby suppressing its super activity caused by H1047R mutation63.

To maintain this essential interaction, we retained the benzoic acid pharmacophore from a known selective inhibitor (PDB ID: 8V8U, Fig. 6c) and applied the lead-imprinting process. Thereby, MolEdit attempts to preserve the hydrogen bond with Arg1047 while exploring nearby chemical space with high affinity targeting PI3K\(\alpha\) H1047R mutant. In Fig. 6c, representative molecules generated through this process exhibit high docking scores against the H1047R mutant and retain the critical hydrogen bond with Arg1047, suggesting they likely preserve the ability of selective inhibition. This example illustrates how MolEdit can integrate existing pharmacophore and mechanistic insights with GenAI to design novel molecules that exhibit both strong binding affinity and potential clinical relevance.

Discussion

Molecular editing is a central concept in the in silico design of functional molecules, which includes the generation, modification, and optimization of molecules to achieve desired properties with specific chemical contexts and structural features. It also represents a long-standing challenge with significant demand and interest, aimed at accelerating the discovery of new functional molecules for scientific, medical and industrial applications. Traditionally, molecular editing involves a labor-intensive trial-and-error process, heavily reliant on specialized expert knowledge.

Modern GenAIs, particularly, DDPMs, have reformed and redefined how images can be generated and modified with unprecedented flexibility. Particularly, converging to scalable model architectures like convolution and transformer, foundational GenAI can be readily adapted for various purposes such as image inpainting, compositing and style transfer15,16,17. Many of these concepts and demands are also shared by molecular design, hence, it is appealing to borrow the portfolio of mainstream GenAI for molecular generation. Unfortunately, as special 3D objects, molecules inherit non-trivial physics complexity, and previous research mainly focused on developing domain-specific model architectures or training objectives. Although some innovations along this line have shown effectiveness, one particular concern of such attempts lies in the compromised scalability and the growing gap from the mainstream GenAI. Such a divergence in technical momentum induces incompatibility with the rapid progress brought by mainstream GenAI, and impedes the convergence of a foundation model for molecular generation.

In this research, we introduced several plug-and-play techniques, through which one can simply parallel molecular generation with image generation and implement scalable models to generate realistic 3D molecules. These techniques, including GO labeling, can be viewed as a bug-fixer to vector-space DDPMs, because they are model-agnostic and induce almost no overhead to the training of standard DDPMs. Although being simple in practice, we showed that models trained by these means exhibit better generalizability and symmetry awareness. Based on these advances, we pretrained and fine-tuned MolEdit, a foundation GenAI for molecules, which is expected to be adaptable for various downstream tasks. With 3D molecular reconstruction as the pre-training target, MolEdit enjoys the advantage that it can be trained simultaneously on molecular configuration and conformation, thus can be easily scaled up to even larger datasets.

In contrast to existing molecular GenAIs, hallucinations are carefully addressed during training and inference of MolEdit. Particularly, through experiments we showed that hallucinations of molecular GenAI, including invalidity, instability, and violation of conditions, can be effectively suppressed by preference alignment with respect to cheap and accessible AI agents and physics critics during training or fine-tuning. Besides, we also equip MolEdit with self-improvement abilities to yield better sample quality during inference. Put all together, MolEdit is able to generate valid molecules with comprehensive symmetry, strikes a better balance between configuration stability and conformer diversity, and even supports complicated 3D scaffolds which frustrate other methods.

As a foundation model, we showed that MolEdit can be applied to various downstream tasks through fine-tuning or even in a zero-shot manner. In Results, we demonstrate MolEdit’s capability to render and edit physically-favored structures from textual molecular representations, such as graphs and SMILES strings. Furthermore, we apply MolEdit to in-silico functional molecular editing, where molecules are designed or modified to meet chemical specifications, such as functional cores, fragments, and groups. Finally, with crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes, we utilize MolEdit to design molecules resembling the shapes of lead compounds that bind to target proteins. These molecules, validated through docking calculations, show potential as effective binders.

Despite its versatility, MolEdit has several limitations. First, the pre-trained model does not generate explicit hydrogen coordinates, which restricts applications that depend on precise protonation states or hydrogen-sensitive properties, particularly quantum-chemical descriptions (Supplementary Discussion 2.9). Second, bond orders are inferred from 3D coordinates and constituents (Supplementary Methods 1.10); this inference can be ambiguous for tautomers and other edge cases. Third, MolEdit lacks direct pocket conditioning and instead relies on shape-guided inference (“lead imprinting”, Supplementary Methods 1.13). This strategy depends on the availability of appropriate lead molecules and limits MolEdit’s applicability in scenarios requiring direct pocket-specific interactions or rigorous target-guided design.

The MolEdit codebase is openly available, and we hope future work will address these limitations. Potential directions include hydrogen-aware training, improving graph topology prediction, and introducing plug-ins such as ControlNet17 for task-specific fine-tuning. We expect that further refinement and development will lead to more innovative applications in the future and molecular editing can be made as simple as image editing. Given the fact that our methods are scalable and model-agnostic, it is also a promising direction to generalize MolEdit to macromolecules such as bio-polymers, or apply these techniques to enhance existing 3D diffusion models like AlphaFold364, and we leave these exciting ideas for future research.

Methods

Leveling up to 3D representation for multimodal molecular generation

Unlike image generation, where pixels are uniformly used as data representation across different generative models, molecular generation methods vary considerably in how they represent molecules. SMILES29, the first widely adopted molecular representation, leverages its string format for compatibility with text processing models30,31,32. Although being machine-friendly, SMILES was primarily designed for efficient machine recording and suffers from several limitations65,66,67. It is not unique, as a single molecule can be represented by multiple degenerate strings (Fig. 1a). Moreover, it is grammatically fragile and lacks the inductive bias needed for similar molecules to be encoded similarly (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, molecules can be alternatively represented as graphs. Unlike SMILES, graph representations preserve the permutation invariance of molecules. Yet, graphs pose significant challenges to modern scalable AI models due to the polynomial computational complexity68,69. Particularly, generating graphs is a significant problem due to the discrete optimization process and the combinatorial explosion resulting from permutation invariance33,34,67. The sparse nature of molecular graphs exacerbates this issue35,70. Worse still, similar to SMILES, graphs can also be ambiguous, where a single molecule may correspond to multiple degenerate molecular graphs (Fig. 1a), indicating that the heuristic of molecular graphs is not characteristic of the nature of the molecular universe.

On the other hand, at atomistic level, molecules are completely determined by their continuous atomic positions without ambiguity. Unlike strings or graphs, in 3D representation, both conformers and isomers are simply different arrangements of molecular coordinates (Fig. 1c), providing a unified perspective that facilitates exploration across conformational and chemical spaces. Therefore, by learning 3D molecular representations, rather than either isomers or conformers alone, we can leverage available molecular data to the maximum extent, and endow the model with generalization capability. Although being an ideal representation for molecules, unfortunately, 3D atomic coordinates exhibit specific symmetry constraints, thus being machine-unfriendly. How to effectively and efficiently deal with molecular symmetry remains wide open in machine learning18,19,24,71,72. To address this issue, we develop GO labeling, a non-invasive plug-and-play remedy, in order to adapt vector-space diffusion models to be aware of molecular symmetries.

Imbue diffusion models with symmetry-awareness via group-optimized labeling

Molecular structures are invariant under translation, rotation, and valid permutations that do not contradict known molecular information (Fig. 1d). Therefore, a generative model \({p}_{\theta }({{\bf{x}}})\) should be group-invariant, i.e., \({p}_{\theta }\left(g\left({{\bf{x}}}\right)\right)={p}_{\theta }\left({{\bf{x}}}\right)\) for any \(g\in {{\mathcal{G}}}\) (symmetry group), where \(g({{\bf{x}}})\) denotes the action of group element \(g\) on \({{\bf{x}}}\). Although equivariance is particularly concerned by existing molecular DDPMs, permutation invariance, which is key to molecular symmetries, is not properly addressed by most 3D molecular GenAIs. This difficulty arises from the explosion of degenerate permutation operations during the forward diffusion process, as also observed in GNN-based molecular generation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Methods 1.1). We demonstrate that, in order to minimize the permutation complexity, a decoupled diffusion strategy is preferred (Fig. 2a; Rationale and details can be found in Supplementary Methods 1.1). Put it simply, unlike existing approaches which diffuse molecular constituents and positions simultaneously24, we opt for an asynchronous multimodal diffusion (AMD) schedule, which whitens the molecular positions prior to the constituents, keeping the number of equivalent permutation operations constant during diffusion. Moreover, AMD formally transforms the generation of molecular structures into a conditional generative task, which not only improves the quality of the generated 3D structures, but also allows systematic suppression of hallucinations via contextual preference alignment. In this study, a discrete probabilistic model first produces the constituents as conditions; then a 3D conditional diffusion model generates the corresponding structures (Fig. 2b, detailed algorithms and model architectures can be found in Supplementary Methods 1.9–1.10).

Noteworthy, we develop a non-invasive method to allow vector-space DDPMs to account for SE(3) equivariance and other molecular symmetries. Unlike existing methods which exclusively rely on equivariant models and equivariant diffusion kernels, we propose to reformulate the labels of score matching11 instead of changing other settings of diffusion models, leading to a minimum modification to the vanilla DDPMs. Specifically, for arbitrary group \({{\mathcal{G}}}\), we define a group-optimized objective for denoising diffusion, where we optimize both the label-transform function \(g\) and the diffusion model \({{{\bf{f}}}}_{\theta }\):

We term \({g}^{*}({{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\bf{s}}}})\) as GO labels (\(g({{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\bf{s}}}}),g\in {{\mathcal{G}}}\) forms the group orbit of element \({{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\bf{s}}}}\)), given the fact that the optimization of \(g\) can be performed offline prior to training of \({{{\bf{f}}}}_{\theta }\), thus, is equivalent to the preparation (or preprocessing) of labels. Importantly, the GO labeling is non-invasive to DDPMs, inducing almost no overhead to the training process; Moreover, it is model-agnostic, that is, compatible with any model architecture of \({{{\bf{f}}}}_{\theta }\). Algorithms of obtaining GO labels can be found in Supplementary Method 1.2–1.5. Besides GO labels, by randomly augmenting the noisy samples x with group operations, we offer flexibility in the choice of \({{{\bf{f}}}}_{\theta }\), which is no more necessarily equivariant and can even be totally non-equivariant64.

Hallucination suppression and self-improvement with respect to contextual conditions and physics critics

Inspired by the success of multimodal and conditional GenAIs, a foundational molecular GenAI should be able to respond to various specifications of molecular editing. Therefore, instead of unconditional training, we train our model MolEdit in context of multiple conditions. For instance, MolEdit is able to control the shape of molecules using the radius of gyration. The model can also be conditioned on (sub)molecular graphs and inpaint the missing motifs given predefined contextual fragments or functional groups. More details about the conditioned generation can be found in Supplementary Methods 1.9 and 1.11. However, parallel to other GenAIs23, 3D molecules generated by AI may also suffer from various undesired hallucinations, among which researchers are particularly concerned with the following pathologies: (1) invalidity, (2) instability, and (3) violation of contextual conditions.

To address violation of contextual conditions, which are commonly encountered in mainstream GenAI, we can directly transact techniques for hallucination suppression developed in the machine learning community. Specifically, preference-aligned optimization is performed during the fine-tuning phase similar to reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF)26 and AI feedback (RLAIF)28, which allows systematic improvement over the consistency with respect to the conditions. Moreover, we also conduct iterative refinement during inference, allowing for post-training improvement of generated molecules to be more consistent with contextual conditions.

Although the validity of generated molecules is a critical metric for assessing molecular GenAIs, existing methods do not have a model-agnostic or data-independent solution to improving this objective. In contrast, thanks to AMD, we can now translate the issue of invalidity as a special type of condition violations, hence, improving this metric continually during and after training.

Besides, the instability of 3D molecules is widely observed in existing molecular GenAIs, yet has not been properly addressed. Particularly, without post hoc corrections, 3D molecular structures generated through data-driven probabilistic methods are often unreal, exhibiting severe physical distortions24,36. This failure arises from the fact that some physical priors such as Pauli exclusion73,74,75 may not be learned through a finite amount of data. To combat this issue, we additionally align MolEdit with respect to physics critics, as an extension to preference alignment with respect to humans or AI. Specifically, during training, MolEdit is optimized based on a physics-informed transition kernel, termed as Boltzmann-Gaussian Mixture (BGM) kernel, leading to a forward transition distribution \({q}_{\sigma,\beta }\left({{\bf{x}}},|,{{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\bf{s}}}}\right)\) as:

where \({{\mathcal{N}}}\left({{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\bf{s}}}},{\sigma }^{2}{{\bf{I}}}\right)\) refers to the Gaussian kernel corresponding to a predefined noise level \(\sigma\) in a data-driven DDPM. In addition to this data-driven term, an extra physics-informed term, taking the form of Boltzmann distribution, is included, and this part makes Eq. (2) an anisotropic kernel. Intuitively, it helps focus the model on restoring important 3D molecular features like bonds and angles which severely impact molecular stability. Parallel to the human feedback in RLHF, \({U}_{{{{\bf{x}}}}_{{{\bf{s}}}}}\) serves as a physics critic or feedback. Unlike post hoc calling of physics models36,76, evaluation of the critic is only performed before training (i.e., alignment) and no longer needed during inference. Therefore, the BGM kernel is also plug-and-play and model-agnostic, similar to GO labeling. Furthermore, to boost the diversity in generated molecular conformers, we also developed a Fokker-Planck Solver (FPS) which allows inference-time improvement over sample entropy. More details about the BGM kernel and FPS can be found in Supplementary Methods 1.6–1.8.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data source of MolEdit is accessible from the Zenodo repository at https://zenodo.org/records/1548081677. This study employed three published datasets for training: QM939, ZINC40,41,42 (https://zinc15.docking.org/), and QMugs43 (the ETH Library Collection https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-00048212978), detailed data cleaning and processing procedures are described in Supplementary Discussion 2.1. Additionally, we incorporated publicly available codes and datasets from EDM24 (https://github.com/ehoogeboom/e3_diffusion_for_molecules), GeoDiff36 (https://github.com/MinkaiXu/GeoDiff), DiffLinker72 (https://github.com/igashov/DiffLinker) and TargetDiff79 (https://github.com/guanjq/targetdiff) for model evaluation. The crystal structures of all proteins and protein-ligand complexes used in this study are publicly available in the Protein Data Bank under the following accession codes: 5A9U, 5IV4, 6BBU, 8V8U. Source data are provided with this paper as a zipped folder. The individual files in the zipped folder are named according to their location in the manuscript, for example, Figure3b.xlsx. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code of MolEdit is available via the GitHub repository at https://github.com/issacAzazel/MolEdit80 under Apache-2.0 license, or as part of the MindSPONGE repository81.

References

Sadybekov, A. V. & Katritch, V. Computational approaches streamlining drug discovery. Nature 616, 673–685 (2023).

Stokes, J. M. et al. A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery. Cell 180, 688–702.e13 (2020).

Kwon, O. et al. Computer-aided discovery of connected metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 10, 3620 (2019).

Barden, C. J. et al. Computer-aided drug design to generate a unique antibiotic family. Nat. Commun. 15, 8317 (2024).

Fromer, J. C. & Coley, C. W. Computer-aided multi-objective optimization in small molecule discovery. Patterns 4, 100678 (2023).

Yang, Z. et al. Matched molecular pair analysis in drug discovery: methods and recent applications. J. Med. Chem. 66, 4361–4377 (2023).

Jorgensen, W. L. Efficient drug lead discovery and optimization. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 724–733 (2009).

Bender, B. J. et al. A practical guide to large-scale docking. Nat. Protoc. 16, 4799–4832 (2021).

Lyu, J. et al. AlphaFold2 structures guide prospective ligand discovery. Science 384, eadn6354 (2024).

Tropsha, A. Integrating QSAR modelling and deep learning in drug discovery: the emergence of deep QSAR. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 23, 141–155 (2024).

Song, Y. & Ermon, S. Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems(2019).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (2020).

Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P. & Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 10674–10685 (IEEE, 2022).

Peebles, W. & Xie, S. Scalable diffusion models with transformers. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 4172–4182 (IEEE, 2023).

Lugmayr, A. et al. RePaint: inpainting using denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11451–11461 (IEEE, 2022).

Meng, C. et al. SDEdit: guided image synthesis and editing with stochastic differential equations. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Zhang, L., Rao, A. & Agrawala, M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 3813–3824 (IEEE, 2023).

Musaelian, A. et al. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 579 (2023).

Frank, J. T., Unke, O. T., Müller, K.-R. & Chmiela, S. A Euclidean transformer for fast and stable machine learned force fields. Nat. Commun. 15, 6539 (2024).

Atkins, P. W., De Paula, J. & Keeler, J. Atkins’ Physical Chemistry (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Song, Y. et al. Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Radford, A. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 8748–8763 (PMLR, 2021).

Farquhar, S., Kossen, J., Kuhn, L. & Gal, Y. Detecting hallucinations in large language models using semantic entropy. Nature 630, 625–630 (2024).

Hoogeboom, E., Satorras, V. G., Vignac, C. & Welling, M. Equivariant diffusion for molecule generation in 3D. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning 8867–8887 (PMLR, 2022).

Ni, Y. et al. Pre-training with fractional denoising to enhance molecular property prediction. Nat. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00900-z (2024).

Ouyang, L. et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2022).

Naderiparizi, S., Liang, X., Cohan, S., Zwartsenberg, B. & Wood, F. Don’t be so negative! Score-based generative modeling with oracle-assisted guidance. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2024).

Lee, H. et al. RLAIF vs. RLHF: Scaling reinforcement learning from human feedback with AI feedback. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2024).

Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 28, 31–36 (1988).

Segler, M. H. S., Kogej, T., Tyrchan, C. & Waller, M. P. Generating focused molecule libraries for drug discovery with recurrent neural networks. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 120–131 (2018).

Grisoni, F., Moret, M., Lingwood, R. & Schneider, G. Bidirectional molecule generation with recurrent neural networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 1175–1183 (2020).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Jin, W., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. Junction tree variational autoencoder for molecular graph generation. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning 2323–2332 (PMLR, 2018).

Assouel, R., Ahmed, M., Segler, M. H., Saffari, A. & Bengio, Y. DEFactor: differentiable edge factorization-based probabilistic graph generation. arXiv.org https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.09766v1 (2018).

De Cao, N. & Kipf, T. MolGAN: an implicit generative model for small molecular graphs. In ICML 2018 workshop on Theoretical Foundations and Applications of Deep Generative Models (2018).

Xu, M. et al. GeoDiff: a geometric diffusion model for molecular conformation generation. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Rappe, A. K., Casewit, C. J., Colwell, K. S., Goddard, W. A. I. & Skiff, W. M. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10024–10035 (1992).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Ramakrishnan, R., Dral, P. O., Rupp, M. & von Lilienfeld, O. A. Quantum chemistry structures and properties of 134 kilo molecules. Sci. Data 1, 140022 (2014).

Irwin, J. J. & Shoichet, B. K. ZINC—a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 45, 177–182 (2005).

Irwin, J. J., Sterling, T., Mysinger, M. M., Bolstad, E. S. & Coleman, R. G. ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 1757–1768 (2012).

Sterling, T. & Irwin, J. J. ZINC 15—ligand discovery for everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 55, 2324–2337 (2015).

Isert, C., Atz, K., Jiménez-Luna, J. & Schneider, G. QMugs, quantum mechanical properties of drug-like molecules. Sci. Data 9, 273 (2022).

Nie, W. et al. Diffusion models for adversarial purification. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2022).

Wallace, B. et al. Diffusion model alignment using direct preference optimization. in 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 8228–8238 (IEEE, 2024).

Lu, C. et al. Dpm-solver: a fast ode solver for diffusion probabilistic model sampling in around 10 steps. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 5775–5787 (2022).

Landrum, G. et al. rdkit/rdkit: 2024_09_1 (Q3 2024) Release Beta. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.591637 (2024).

Axelrod, S. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. GEOM, energy-annotated molecular conformations for property prediction and molecular generation. Sci. Data 9, 185 (2022).

Erlanson, D. A., Fesik, S. W., Hubbard, R. E., Jahnke, W. & Jhoti, H. Twenty years on: the impact of fragments on drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 605–619 (2016).

Ha, J. M., Hur, S. H., Pathak, A., Jeong, J.-E. & Woo, H. Y. Recent advances in organic luminescent materials with narrowband emission. NPG Asia Mater. 13, 53 (2021).

Luke, J., Yang, E. J., Labanti, C., Park, S. Y. & Kim, J.-S. Key molecular perspectives for high stability in organic photovoltaics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 839–852 (2023).

Dixon, S. L. et al. PHASE: a new engine for pharmacophore perception, 3D QSAR model development, and 3D database screening: 1. Methodology and preliminary results. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 20, 647–671 (2006).

Meyenburg, C., Dolfus, U., Briem, H. & Rarey, M. Galileo: three-dimensional searching in large combinatorial fragment spaces on the example of pharmacophores. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 37, 1–16 (2023).

Zheng, S. et al. Accelerated rational PROTAC design via deep learning and molecular simulations. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 739–748 (2022).

Wang, L., Berne, B. J. & Friesner, R. A. On achieving high accuracy and reliability in the calculation of relative protein–ligand binding affinities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1937–1942 (2012).

Mey, A. S. J. S. et al. Best practices for alchemical free energy calculations [Article v1.0]. Living J. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 18378 (2020).

Sun, S. et al. Scaffold hopping and optimization of small molecule soluble adenyl cyclase inhibitors led by free energy perturbation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 2828–2841 (2023).

Ballester, P. J. & Richards, W. G. Ultrafast shape recognition to search compound databases for similar molecular shapes. J. Comput. Chem. 28, 1711–1723 (2007).

Hawkins, P. C. D., Skillman, A. G. & Nicholls, A. Comparison of shape-matching and docking as virtual screening tools. J. Med. Chem. 50, 74–82 (2007).

Wang, Z. et al. Fully flexible molecular alignment enables accurate ligand structure modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64, 6205–6215 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. DSDP: a blind docking strategy accelerated by GPUs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 4355–4363 (2023).

Ketcham, J. M. et al. Discovery of pyridopyrimidinones that selectively inhibit the H1047R PI3Kα mutant protein. J. Med. Chem. 67, 4936–4949 (2024).

Huang, X. et al. Cryo-EM structures reveal two allosteric inhibition modes of PI3KαH1047R involving a re-shaping of the activation loop. Structure 32, 907–917.e7 (2024).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Krenn, M., Häse, F., Nigam, A., Friederich, P. & Aspuru-Guzik, A. Self-referencing embedded strings (SELFIES): a 100% robust molecular string representation. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 1, 045024 (2020).

Arús-Pous, J. et al. Randomized SMILES strings improve the quality of molecular generative models. J. Cheminform. 11, 71 (2019).

Boitreaud, J., Mallet, V., Oliver, C. & Waldispühl, J. OptiMol: optimization of binding affinities in chemical space for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 5658–5666 (2020).

Wu, Z. et al. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32, 4–24 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Graph neural networks: a review of methods and applications. AI Open 1, 57–81 (2020).

Williams, R. J. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Mach. Learn. 8, 229–256 (1992).

Huang, L. et al. A dual diffusion model enables 3D molecule generation and lead optimization based on target pockets. Nat. Commun. 15, 2657 (2024).

Igashov, I. et al. Equivariant 3D-conditional diffusion model for molecular linker design. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 417–427 (2024).

Pfau, D., Spencer, J. S., Matthews, A. G. D. G. & Foulkes, W. M. C. Ab initio solution of the many-electron Schrödinger equation with deep neural networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033429 (2020).

Hermann, J., Schätzle, Z. & Noé, F. Deep-neural-network solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation. Nat. Chem. 12, 891–897 (2020).

Pfau, D., Axelrod, S., Sutterud, H., Von Glehn, I. & Spencer, J. S. Accurate computation of quantum excited states with neural networks. Science 385, eadn0137 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Protein conformation generation via force-guided SE(3) diffusion models. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (2024).

Lin, X. et al. In-silico 3D molecular editing through physics-informed and preference-aligned generative foundation models. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.15480816 (2025).

Isert, C., Atz, K., Jiménez-Luna, J. & Schneider, G. QMugs: Quantum Mechanical Properties of Drug-like Molecules., ETH Zurich, https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000482129 (2021).

Guan, J. et al. 3D equivariant diffusion for target-aware molecule generation and affinity prediction. in The 11th International Conference on Learning Representations (2023)

Lin, X. et al. In-silico 3D molecular editing through physics-informed and preference-aligned generative foundation models. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.15485932 (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. Artificial intelligence enhanced molecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 4338–4350 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022ZD0115002 to Y.Q.G.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 92353304, T2495221, 21927901 to Y.Q.G.) and New Cornerstone Science Foundation (NCI202305 to Y.Q.G.). This work was partly done during Shuo Liu’s internship in Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. The authors thank Zhenyu Chen, Siyuan Jiang, Mengyun Chen, Ningxi Ni and Zidong Wang for useful discussion, and gratefully acknowledge the support from Huawei Ascend and MindSpore team to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q.G. and J.Z. developed overall concepts in the paper and supervised the project. X.L., Y.X., Y.L. and S.L. developed and benchmarked the model and/or contributed to the code. Y.H. proposed and developed the Gaussian-Boltzmann mixture kernel. X.L. performed data collection and analysis. X.L. and J.Z. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed ideas to the work and assisted in manuscript editing and revision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kenneth Atz, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, X., Xia, Y., Li, Y. et al. In-silico 3D molecular editing through physics-informed and preference-aligned generative foundation models. Nat Commun 16, 6043 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61323-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61323-x