Abstract

Mycelium-bound composites (MBCs) grown from fungi onto solid lignocellulosic substrates offer a sustainable alternative to petroleum-based materials. However, their limited mechanical strength and durability are often insufficient for practical applications. In this work, we report a method for designing and developing strong and thermally insulating MBCs. The method grows mycelium onto 3D-printed stiff wood-Polylactic Acid (PLA) porous gyroid scaffolds, enhancing the strength of the scaffold while imparting other functional properties like thermal insulation, fire resistance, hydrophobicity, and durability. The extent of improvement in MBCs’ performance is directly dependent on the mycelium growth, and the best growth is observed at 90% porosity. We observe yield strength (σy) of 7.29 ± 0.65 MPa for 50% porosity MBC, and thermal conductivity (Kt) of 0.012 W/mK for 90% porosity MBC. Maximum improvement in σy (50.4–77.7%) between before and after mycelium growth is observed at medium (70%)–high (90%) porosity. The MBCs also exhibit design-dependent improved fire-resistance and durability compared to the base wood-PLA scaffold, further enhancing their suitability for practical applications. Our findings show that integration of 3D printing, design, and biomaterials enables the development of sustainable bio-based composites to replace pollution-causing materials from the construction industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction sector, liable for 37% of global greenhouse gas emissions, adds new buildings equivalent in number to the total number of buildings in the city of Paris every five days1. Brick manufacturing alone contributes significantly to CO2 emissions and global warming, with conventional kilns emitting 0.8–1.2 kg CO2 per brick2. The construction industry also depends greatly on thermal insulators, such as mineral wool and expanded polystyrene (EPS), which regulate heat dissipation but often have significant environmental impacts from production to disposal3. The sectors responsible for carbon emissions are forecasted to further increase their emissions from 25% to 50% by 20501. However, implementing sustainable practices could decrease emissions by 40% by 2050. For instance, repurposing existing buildings produces 50–75% less emissions than constructing new ones1. To achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century, the construction industry must focus on circular economy approaches, bio-based materials, and decarbonizing conventional materials like steel, aluminum, and concrete4. Bio-based construction materials include bamboo, timber, hemp, straw, cork, mycelium, and bioplastics5,6,7. These materials offer lower carbon footprints and can capture CO2, offering sustainable material choices4,8. However, these materials face challenges like inconsistent quality, moisture sensitivity, fire hazard, and low durability9,10. Developing biomaterials with enhanced thermo-mechanical properties and durability is therefore needed to reduce the environmental impacts of buildings.

By harnessing the unique properties of living organisms, biomaterials can be converted into functional materials and address some challenges for other passive bio-based materials11. These living biomaterials, called engineered living materials (ELMs), can grow, self-repair, and adapt to environmental changes, making them highly versatile for various applications12,13,14. MBCs are one type of ELMs, grown by fungi onto lignocellulosic substrates. MBCs are sustainable bio-composites in which organic substrates like agricultural waste are bonded using fungal mycelium as a natural adhesive. These composites are biodegradable, lightweight, and customizable. For long-term applications, the MBCs can be dried to kill the fungus and to create materials with functional properties like hydrophobicity, thermal insulation, and fire-resistance15,16,17. Because they are bio-based, MBCs hold significant potential as a sustainable alternative, but their adoption is limited by their typically low yield strength of about 0.01–0.72 MPa18,19. This low strength arises from the root-like network of hyphae that loosely bind the organic lignocellulosic substrate together. The hyphae network creates a flexible and lightweight material, but it lacks the rigidity necessary for construction applications. Increasing the mechanical strength of MBCs while retaining their multiple functional properties could facilitate their adoption in the infrastructure industry.

One way to increase the mechanical properties of MBCs is to press them, but this results in a loss of shape and thermal insulation properties20. Another way could be to increase the density of hyphae to create a stronger binding network. However, it is not easy to homogeneously grow dense hyphae: a dense fungal skin layer is generally formed at the surface of the substrate, blocking oxygen and humidity access to the interior of the structure, resulting in a low-density hyphae network. Having a porous substrate can facilitate oxygen diffusion and improve mycelium growth and stiffness while further enhancing functional properties due to the increased surface area21. The porosity of loose lignocellulosic substrates could be tailored by varying the size of the particles in the substrate, but the discontinuity of the particles would still lead to weak mechanical properties. In turn, rigid porous lignocellulosic bio-based substrates could be obtained using biopolymers reinforced by wood particles. Furthermore, the designed scaffolds allow precise control over architecture and porosity, in terms allows for tuneable strength and functional properties22. Commercially available 3D printing filaments made from PLA and recycled wood could be 3D printed into porous structures for the mycelium to grow.

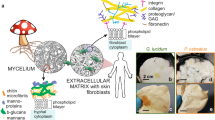

In this study, we develop MBCs by using a stiff scaffold, which increases the mechanical strength and mycelium growth. In turn, the mycelium growth also improves the mechanical and functional properties of the scaffold. We propose to use these MBCs as a sustainable alternative to clay bricks currently used in construction, which cause pollution during processing and are disposed of by landfilling (Fig. 1a). The fabrication of the MBCs uses a nutrition-rich solution to coat a 3D-printed porous scaffold made from bio-based materials. The nutritious solution enables the growth of the mycelium and the final functional properties, while the 3D-printed scaffold enables customization, design of the optimum porous structure, and mechanical properties (Fig. 1b). Additionally, micropores in the scaffold material, wood-PLA, facilitate moisture retention via capillary action, creating an environment that supports mycelium proliferation and metabolic activity (Fig. 1c). Our method uses a 3D printer, wood-PLA filament, nutrition-rich solution, and mycelium inoculant. The low temperature and simplicity of the process enable easy fabrication, without the need for energy-intensive kilns, complex equipment, and infrastructure, which also reduces transportation cost and emissions. For physical, mechanical, and thermal properties of wood-PLA, (see Supplementary Table 1) and more information about the selection of porous scaffold design is mentioned in (see Supplementary notes). Ganoderma lucidum is the fungal species chosen to demonstrate the concept of this work, given its excellent properties reported, although the approach is applicable to other species. The synergistic presence of the macropores from the scaffold design and the micropores from the scaffold material leads to improvement in mycelium growth and which directly improves the mechanical and functional properties.

a Cartoons making a parallel between clay and mycelium bricks, as proposed in this study. The manufacturing of clay bricks is energy-intensive and results in landfilling. Mycelium brick can be produced with low energy drying, are tailor-made and compostable. b Schematic showing the fabrication steps of mycelium bricks. Bio-based raw materials from low-cost discarded wood and corn are converted into filaments for 3D printing a porous scaffold. This scaffold is coated with the nutrition rich solution of Peptone-Malt-Agar (PMA) by dipping. The fungus is then inoculated and grown for 21 days. c Electron micrograph of the 3D printing filament, revealing wood flakes distributed in the PLA matrix with some micropores (scale bar is 100 μm). Micro-computed tomography reconstructed data showing the 3D distribution and percentage of different elements in the 3D printing filament.

Results

Mycelium growth

To achieve the desired final properties of the composite bricks, mycelium should grow on the entire 3D printed wood-PLA scaffold. The growth of the mycelium depends on the composition of the Peptone-Malt-Agar (PMA) coating, unit cell size, and the porosity of the scaffold, which were investigated on a wood-PLA gyroid scaffold (Fig. 2). This study selected gyroid due to its superior mechanical properties, interconnected porous network and high surface area (Supplementary notes).

a Growth of mycelium with time on wood-PLA with PMA coating containing 10 w/v% malt (scale bar is 10 mm). The inset shows the microscopic network of mycelial hyphae, where blue arrows indicate porosity, and red arrows show interwoven connections and hyphae (scale bar is 10 μm). b Increase in mycelium mass (top) and the corresponding decrease in moisture (bottom) as a function of growth time (Data are presented as Mean value ± SD for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). c 5 × 5 matrix representation of the change in average hyphae diameter and mycelium density with change in unit cell size and porosity of the gyroid scaffold after 21 days of growth. Lighter color represents low mycelium density and darker represents high mycelium density. d Difference of the air flow in the 50% and 90% unit cell porosity gyroid scaffold from computational flow dynamics (CFD) simulation. Low air flow in 50% results in less oxygen supply and low CO2 removal from the scaffold, resulting low density mycelium, high air flow and continuous supply of oxygen and removal of CO2 resulting in high density mycelium (Pictures on the right) (scale bars are 10 mm).

First, the PMA coating should be optimized to allow for efficient mycelium growth. Malt is the main component that influences the growth and determines the exploration (guerilla) or exploitation (phalanx) growth behavior of the mycelium. Previous work growing G. lucidum on hydrogels reported that a malt concentration lesser than 2–4 w/v% of the PMA solution favors exploration, while a concentration between 2 and 20 w/v% favors exploitation12. Since we want to form a thick, dense, and uniform mycelium layer onto the scaffolds, we varied the malt concentration between 2 and 20 w/v% while keeping agar and peptone constant. For 2 to 5 w/v% malt, the mycelium still exhibits exploration behavior, forming a fluffy and highly porous mycelium layer (Supplementary Fig. 1a). At 20 w/v% malt, the mycelium exhibits exploitation behavior, with a dense but slow mycelium formation so that even after 21 days, the scaffolds were not entirely covered. At 10 w/v% malt, there is a balance between exploration and exploitation resulting in a healthy and vigorous growth of the mycelium which covers the entire scaffold homogeneously. For the rest of the study, 10 w/v% malt was used and 40 mm cubic uniform gyroid samples with 70% porosity were completely covered with mycelium in 14 days. An addition of 7 days led to the formation of highly branched hyphae and a dense mycelium layer (Fig. 2a). In the final week of incubation, although the mycelium mass reaches saturation, it displays active branching and expands its network without an increase in total biomass (Fig. 2b).

In the design of the porous scaffold, we considered unit cell sizes and porosities in the range of 5–25 mm and 50–90%, respectively, based on printability and practical application (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Too small unit cell sizes are difficult to print, and too large ones create gaps too wide for the mycelium to bridge. Similarly, porosities above 90% are difficult to print, whereas below 50%, the scaffolds do not cover our scope of porous MBCs. Furthermore, small pore sizes clog during PMA coating and prevent the internal spread of the hyphae. Clogging can also occur when the dipping time of the scaffolds in the PMA solution is too long (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Indeed, as the dipping time increases, the thickness of the PMA coating increases. On the porous scaffolds, the hyphal diameter and density in the mycelium layer were measured from electron micrographs after 21 days of growth (Fig. 2c). Larger hyphal densities are often associated with higher unit cell porosity, suggesting a possible relation between the structure of the hyphae and the overall porosity of the scaffold. However, the hyphal diameter did not show a clear relationship with the unit cell size and porosity of the scaffold. In general, the hyphal diameter varies between 0.85 and 1.04 μm, and the mycelium layer density lies between 41.68 and 81.43%. The high mycelium density obtained at 90% unit cell porosity results from the efficient and continuous supply of oxygen, which is necessary for mycelium growth, while it avoids CO₂ build-up. Real-time computational flow dynamics (CFD) simulation of gyroid scaffolds with 50% and 90% unit cell porosities show higher and continuous airflow at 90% porosity and low and stagnant air flow at 50% (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 1d). This is visualized by the wood-PLA brown color appearing below the mycelium on the scaffold with 50% porosity after 21 days growth, whereas the wood-PLA color is not visible anymore on the scaffold with 90% porosity. Also, the connected porous network in the gyroid aided the internal growth of the mycelium (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b).

Understanding the interaction between scaffold and mycelium is crucial to reveal changes in chemical structure during mycelium growth, impacting the composite’s performance. The chemical composition and bonding structure of PLA, wood-PLA, and the MBCs are studied using electron micrographs, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The schematic and electron micrographs of the MBCs cross-section show three types of hyphae: aerial, biofilm, and penetrative hyphae (Supplementary Fig. 3a–f, and Supplementary notes). These multilayered interactions involving both surface colonization and structural penetration contribute to good adhesion at the mycelium-scaffold interface. In our MBCs, the combination of a 3D printed porous scaffold, and colonizing mycelium forms a functionally integrated material. The interpenetration, binding, and mutual reinforcement between the wood-PLA scaffold and the mycelia justify the use of the term “composite” in the broader context of mycelium bio-composites.

C–C/C–H (alkyl bonds) and C = O (carbonyl bonds) are the signature peaks for the polymer backbone in PLA. In the wood-PLA, C–O (ether or hydroxyl bonds) intensity increases due to the lignocellulosic components of wood. The presence of O–C = O (ester linkages) increases from the interactions between PLA and wood flakes. The C = O (carbonyl group) in the MBC comes from the carbohydrate breakdown of the malt (Supplementary Fig. 4a,b). The XPS plots also show the presence of nitrogen in the MBC (Supplementary Fig. 4c) which come from the nitrogen-containing functional groups, i.e., amine (C–N) and amide (N–C = O) bonds. This confirms the integration between fungal biomass and scaffold, as these functional groups are characteristic of proteins and chitin present in mycelium23. In the FTIR plots (Supplementary Fig. 4d), the broad peak around 3200–3600 cm⁻¹, attributed to O–H or N–H stretching, is more prominent in the MBC. This increase indicates a high presence of hydroxyl (O–H) and potentially amine (N–H) groups, which are contributed by the lignocellulosic wood flakes as well as the protein or polysaccharide components present in the mycelium24. Mycelium also introduces additional O–H, N–H, C–O, and possibly C–N and N–C = O bonds, suggesting a stronger and more diverse interaction between wood-PLA and mycelium, which means a more cohesive interface and better load transfer between the interfaces. These interactions could enhance mechanical properties by promoting a more unified structure at the interface. Building on the insights from the relation between scaffold design parameters (unit cell size and porosity) and the growth dynamics of mycelium, the next section examines the mechanical properties of the MBCs to evaluate their structural performance. Furthermore, the current work studied both inactive MBCs (mycelium was killed after 21 days) and living MBCs (mycelium was kept alive). It should be noted that unless specifically mentioned, the reader should consider the analysis of inactive MBCs.

Mechanical properties

The influence of scaffold design (porosity and functional grading) on the mechanical properties of the MBCs was analysed to assess their structural performance (Fig. 3). The notation used for different designs is: U-uniform, PG-porosity graded, CG-cell size grading, and adjacent number is porosity (%). e.g., U90 indicates a uniform scaffold with 90% porosity).

a Images of the scaffolds before (top) and after (bottom) 21 days mycelium growth for 3 different designs: uniform 70% porosity (green), porosity graded from 70 to 90% (blue), and unit cell size graded from 20 to 10 mm (bottom to top) (orange). (scale bar is 10 mm). b Stress-strain curves of the 3 different designs before (dashed lines) and after mycelium growth (continuous lines), shaded regions show the 95% confidence of interval (t-distribution, mean ± 95% confidence interval based on n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). Insert images show the deformation of uniform 70% porosity MBC at different strains. c Yield strength (σy) and percentage improvement (with respect to wood-PLA scaffold) in yield strength of MBCs as a function of effective porosity (Data are presented as Mean value ± SD for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). For mechanical data of wood-PLA scaffolds (see Supplementary Table 2). d Yield strength-density map of the MBCs prepared in this study (orange filled star - best MBC), the wood-PLA scaffolds as well as existing materials: bricks (green), and other MBCs (plum for mold and dark yellow for ink-based fabrication method). Conventional polymers (red), foams (blue), and wood and wood products (black) are also represented (For exact references to data points, readers are advised to follow Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

The yield strength (σy) of the MBCs grown on a gyroid scaffold with 70% porosity increases with increasing malt concentration up to 10 w/v% which corresponds to a dense and homogeneous mycelium layer (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Next, PMA coating with 10 w/v% malt was used to grow the mycelium on different scaffold designs: uniform (U), porosity-graded (PG), and cell size graded (CG) (Fig. 3a). The stress-strain curves of the MBCs and the bare scaffolds (without mycelium) were measured under compression (Fig. 3b). Pictures during the test also show the layer-by-layer deformation mechanism of the uniform 70% porosity MBC (U70_my). All the curves present an elastic region, a plateau, and a densification region, which is typical of porous structures25. In the elastic region, the stress values are the same for the MBCs and the scaffold alone since the load is mostly carried by the walls of the scaffold. Beyond the yield stress, the cell walls start to collapse, and the mycelium layer acts as a foam inside the porous scaffold (Supplementary Fig. 5b), substantially increasing the peak stress (σp) values in the MBCs as compared to the bare scaffolds. After the densification strain, the cell walls are already collapsed, and the porous sample becomes dense. This means in the densification region, the samples are acting as a solid material as the load progresses, the stress value increases abruptly, and the samples show fracture after 5–10% onset of their densification strain (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

For the designs explored here, the MBCs with cell size grading showed the best mechanical performance. However, the highest improvement in σy and specific energy absorption (SEA) after mycelium growth was observed in the porosity-graded MBCs (PG_my). The porosity graded MBCs with 90% effective porosity (gradually changes from 100 to 80%) were not included in this work, due to the constraint on the printing dimensions. For all designs, the σy and SEA decrease when the porosity increases because the unit cell wall thickness decreases. Nevertheless, the improvement in properties increases due to more mycelium growth: 90% porosity (CG90_my) shows a 77.7% and 133.33% increase in σy and SEA, respectively (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). Though a significant increase in σy was observed, the load-carrying capacity of mycelium becomes more prominent after the cell walls start to collapse and mycelium acts as a foam between two walls, resulting in a further increase in σp. The highest mechanical performance was observed with cell size grading. For example, CG50_my MBC shows elastic modulus (E) = 257 ± 18.8 MPa, σy = 7.29 ± 0.65 MPa, σp = 15.77 ± 1.08 MPa, and SEA = 8.79 ± 0.77 kJ/kg (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Overall, integrating mycelium with wood-PLA scaffold showed that the mycelium growth improves the elastic modulus by 4.2–80.95%, yield strength by 9.58–77.78%, peak strength by 14.87–163.63%, and energy absorption by 14.11–125.1%. While Fig. 3c presents both absolute σy and percentage improvements in σy due to mycelium colonization, we would like to highlight that at high porosities, the relatively high percentage improvements come from the initial low scaffold strength, which is a common limitation in percentage-based representation. However, our intention is not to emphasize these standalone values as performance indicators. The goal is to show the trend and relative contribution of mycelium reinforcement across different porosity and designs.

In addition to the compressive properties, the adhesion between the mycelium and wood-PLA was measured using double-lap shear pull tests (Supplementary Fig. 5g). The measured shear strength provides an estimate for interfacial bonding, which plays a critical role in stress transfer and improvement in mechanical properties of MBCs. The higher adhesion strength of 0.044 ± 0.001 MPa suggests effective load transfer between biological mycelia and stiff wood-PLA scaffold. Fracture morphology reveals a combination of cohesive failure within the mycelial network and interfacial delamination (Supplementary Fig. 5h, i). For reference, the earlier work on hot-pressed joints between mycelium and wood has reported shear strength between 0.2–1.74 MPa26, which could be due to the densification of the joints during hot-pressing, a condition not present in our ambient conditions grown MBCs.

The MBCs obtained provide an excellent balance of strength and density, making them suitable materials for lightweight and sustainable construction applications. Indeed, the MBCs have properties comparable to existing wood products with a tunability easily achievable through design (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table 3). In particular, we demonstrate that it is possible to obtain MBCs with strength comparable to that of bricks, which confirms their capability to be used for low-load bearing applications, such as false walls, decorative features, or insulation panels. The σy of MBCs reported across the literature lies in the range of 0.01–0.72 MPa (Supplementary Table 3). In comparison to other MBCs, the approach presented here fabricates MBCs stronger than ever reported, with σy in the range of 0.15–7.29 MPa, thanks to the presence of mycelium, which improved the properties of the scaffold by 9.5–77.77%. Next, we evaluate the functional properties, including thermal insulation and fire resistance, to further demonstrate the suitability of our MBCs for building applications.

Thermal insulation and fire-resistance

Thermal insulation and fire resistance are key properties for application in the built environment. The thermal properties of the MBCs can be tailored through the design of the scaffold. At the same time, the presence of the design-dependent mycelium layer provides additional insulation and fire resistance (Fig. 4). For example, properties like thermal insulation and fire-resistance can be highly dependent on the direction of grading (porosity and cell size)27. Therefore, in this section, we considered both directions of grading to characterize performance. For porosity graded, PG and PG* samples are used, with PG samples, the hot end (for both thermal and fire tests) is at a higher porosity. For example, in PG6040, the porosity functionally changes from 60% to 40% along one direction (vertical direction), and this sample has an effective porosity of 70%, therefore, this sample is referred to as PG70 (PG70_my for MBC). However, if for the same sample, instead of hot end at 60% porosity, it is shifted to 40% porosity end, and 60% becomes a cold end, this sample is referred to as PG70* (PG70_my* for MBC). Similarly, in CG70 and CG70*, the hot end is at a bigger and smaller unit cell side, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6).

a Infrared thermographic images showing the temperature distribution across U70_my, PG70_my, PG70_my*, CG70_my and CG70_my* MBCs. b Average temperature change with time during heating and cooling for the wood-PLA scaffolds, the MBCs and commonly used polyurethane foams (HDPU and LDPU) (To avoid overlapping of curves, the data for PG80_my* and CG80_my* are not included in the plot, they can be found in source data file). c Thermal conductivity as a function of the scaffold effective porosity for the different MBCs designs, obtained by FEM. Low thermal conductivities represent the influence of mycelium integration and the significant difference in the PG_my and PG_my* MBCs thermal conductivities represent influence of mycelium and design. d Thermal conductivity-density of the MBCs prepared in this study (orange filled star - best MBC), the wood-PLA scaffolds as well as existing materials building materials. (For exact references for the other materials data points, readers are advised to follow Supplementary Table 3). e Pictures of the sample with 50% effective porosity after exposure to flame, showing differences in structural integrity and char formation between wood-PLA and MBCs (scale bar is 10 mm). f Bar chart representation of percentage of surface area burned (all six faces) and change in mass of the samples with 50% effective porosity after fire test (Data are presented as Mean value ± SD for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). g Electron micrographs of the wood-PLA (left) and MBC (right) surfaces after flame exposure (scale bar is 10 μm).

The low thermal conductivity (Kt) of mycelium, reported to be 0.03–0.05 W/mK, makes it suitable for thermal insulation28. In contrast, wood-PLA has a relatively high Kt of 0.51 W/mK, which may increase the overall Kt of the MBCs. However, this effect can be mitigated by introducing porosity, as the low Kt from the air in the pores reduces conductive heat transfer. The combination of a porous scaffold, mycelium, and wood-PLA greatly improves thermal insulation properties, surpassing the performance of traditional polyurethane (PU) foams (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Thermal insulation can be further modulated through the functional grading of the scaffolds. By varying the porosity and material distribution within the scaffold, it is possible to tailor the Kt to meet specific insulation requirements. Thermographic comparisons of uniform MBC (U70_my) with 70% porosity and 20 mm unit cell size, porosity-graded MBCs (PG70_my: 80–60% porosity, hot end at 80%; PG70_my: 60–80% porosity, hot end at 60%), and cell-size-graded MBCs (CG70_my: 40–20 mm, hot end at 40 mm; CG70_my: 20–40 mm, hot end at 20 mm) demonstrate that functional grading enhances thermal insulation performance, with CG70_my showing the highest temperature gradient, which means best insulation (Fig. 4a). This is further confirmed by the heating and cooling behavior of different samples (Fig. 4b). MBCs demonstrate improved thermal insulation, as indicated by their slower heating and cooling rates compared to the scaffolds alone and high-density polyurethane (HDPU) and low-density polyurethane (LDPU) foams. The thermal insulation performance of the MBCs was further extended experimentally and numerically (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary notes).

Finite Element Modeling (FEM) simulations help reveal the heat flux and temperature distributions throughout the uniform and graded MBCs (Supplementary Fig. 6b). U70_my and PG70_my* exhibit higher heat flux, meaning more heat transfer and lower thermal insulation, while functionally graded MBCs CG70_my and PG70_my show lower heat flux and more effective thermal insulation. Furthermore, the insulation performance in the case of the graded MBCs can be engineered by changing the hot (source) and cold (sink) sides of the MBCs. For instance, in PG70_my, where the heat source has 80% porosity and the sink has 60% porosity, the Kt = 0.138 W/mK, whereas in PG70_my*, the hot and cold sides are reversed, the Kt = 0.221 W/mK increases. In PG70_my, the higher air content at the heat source slows down thermal diffusion, creating a thermal barrier. Conversely, when the gradient is reversed (low to high porosity), the denser region near the source enables more heat conduction. Similarly, in the case of CG70_my, where a bigger unit cell size filled with air reduces heat transfer and on CG70_my* the dense structure near the source enhances heat conduction, thus increasing the overall thermal conductivity. Kt also depends on the porosity of the MBCs, as an example in U_my MBCs, higher porosity yields lower Kt (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 6c) due to the combined effect of thermal insulation of mycelium and increased air content inside the pores of MBCs. The Kt vs density plot of shows that our MBCs achieve the lowest thermal conductivity compared to conventional building materials and previously reported MBCs (Fig. 4d). This exceptional thermal performance results from the integrated effect of the mycelium’s natural insulating properties and the engineered porosity of the scaffold, which slows heat transfer through controlled internal architecture. These findings highlight that functional grading tailors heat flow and temperature distribution effectively, offering enhanced design flexibility for different types of infrastructure.

The low Kt of MBCs also enhances their fire resistance by slowing heat transfer, thereby delaying ignition and reducing the flame spread as compared to the scaffolds alone (Fig. 4e). The PG50 wood-PLA scaffold has lowest fire resistance as it burns rapidly due to the highest porosity (60%) at the fire end, while the PG50* has the highest fire resistance in wood-PLA scaffolds it’s because of the lowest porosity (40%) at the fire end. The less burned area and change in weight suggest better fire resistance of MBCs as compared to the scaffolds, due to their char production ability without significant flaming combustion, which restricts the further spread of fire (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). The fire resistance also depends on the design of the MBC, as quantified from a burned area and change in weight between before and after fire testing (Fig. 4f). CG50_my MBCs have the lowest burned area and change in weight, suggesting the best fire resistance. The high fire-resistance of CG50_my could be due to the lower thermal conductivity. Though PG50_my and CG50_my have almost equal thermal conductivity, CG50_my still has better fire-resistance, which could be because the presence of more air at the fire end aided the fire spread in PG50_my MBCs. A similar pattern was observed in the weight change of 70% porosity MBCs (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d) (Samples with 70% porosity showed significant deformation, making it challenging to measure the burned surface area accurately, therefore, data of burned surface area is not included). However, the fire spread much faster in 70% samples as compared to the 50%, which could be the presence of more air at 70%. Fire spread in the wood-PLA scaffolds melts the polymer, compromising the structural integrity, while char in the MBCs prevents melting (Fig. 4g).

For thermal insulation, both mycelium and entrapped air contribute toward performance, whereas for fire resistance, only mycelium contributed positively, as more air content can promote fire spread. The thermal insulation and fire resistance analysis in MBCs is backed by infrared imaging. Experiment and numerical analysis of heat transfer and fire resistance of the MBCs, showcase their exceptional performance and underscore the potential for property customization through design optimization. Building on these advantages, the hydrophobicity and durability of MBCs are critical factors that further determine their suitability and extended functionality in the built environment.

Hydrophobicity and durability

This section illustrates the hydrophobicity and durability tests of MBCs, highlighting water and humidity absorption, and durability under various environmental conditions for inactive and living MBCs (Fig. 5). In the inactive MBCs, mycelium was killed after 21 days of inoculation and in living MBCs, mycelium was still active when the samples were placed in different environment conditions.

a Pictures of MBC (U70_my and CG50_my) repelling water droplets (water dyed in blue) (scale bar is 5 mm). The contact angle θc is measured after 30 min. b Water absorption as a function of days for U70 scaffold and U70_my MBC (Data are presented as Mean value ± SD for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). c Mass decrease (water release) and increase (water uptake) as a function of time for U70 scaffold and U70_my MBCs during cycling fluctuation of humidity (gray) (Data are presented as Mean value for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). d Compressive strength over 300 days for U70_my MBCs left in different environmental conditions, when the mycelium is inactive (Data are presented as Mean value ± SD for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). e Pictures of the U70_my MBCs left at different environment conditions on day 0 and day 300, when mycelium is inactive (scale bar is 10 mm). f Compressive strength of U70_my MBCs left outside the lab (OL) over 100 days, when the mycelium is still active and living (Data are presented as Mean value ± SD for n = 5 biologically independent mycelium samples). g Electron micrographs of the cut cross-section of unit cell walls of the MBC with active mycelium on different days showing the breakdown of the wood-PLA scaffold by the mycelium. Red arrow point to mycelium hyphae (scale bars are 10 μm).

Water absorption problems could be more severe in porous materials because of the internal cavities and high surface area. The contact angle (θc) of the wood-PLA scaffolds increased from 85.51° to 130.93° after mycelium growth (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 8a). The slightly lower θc (121°) for CG50_my is due to low density of mycelium hyphae at 50% porosity of scaffold. The increasing θc and its stability over time indicate the enhancement in hydrophobicity due to the mycelium layer, making the MBCs more resistant to moisture. Furthermore, the water absorption of the wood-PLA scaffolds and MBCs showed a rapid increase over the first 7 days, with higher absorption in the wood-PLA scaffolds (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 8b). Overall, mycelium decreases water absorption by 2.6 times. The improvement in hydrophobicity can be due to the secretion of hydrophobic proteins (e.g., hydrophobins), which coat the surface and reduce water absorption29. The network of thread-like dense hyphal growth limits water penetration (Supplementary Fig. 3c, e). Mycelium also changes the surface chemistry by depositing lipids, polysaccharides, and other hydrophobic compounds (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Construction materials might expand and contract under fluctuating and high-humidity environmental conditions, which could develop cracks and compromise the integrity of the building30. We studied the moisture uptake and release according to the NORD test. In NORD test, the samples are subjected to two humidity levels to evaluate their hydrophobicity and overall resilience. At low humidity of 53%, the mass of both wood-PLA scaffolds and MBCs decreased, suggesting moisture release. At high humidity of 75%, the mass of the samples increased, suggesting moisture uptake. The rate of moisture release is higher, and the uptake is lower in the MBCs as compared to the wood-PLA scaffolds, as can be seen from the slopes of the lines (Fig. 5c). The higher release rate means the moisture absorption in the MBCs is low, as mycelium prevents the capillary intake of the water. This could avoid any structural change in the MBCs due to moisture absorption.

The durability of the samples was studied for inactive and living mycelium. The inactive MBCs were left for 300 days under three environmental conditions. The durability of the MBCs was assessed by measuring the σy and weight on different days (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 8c). Results show no significant change in the aforementioned properties for all three conditions. The MBCs are in perfect condition even after 300 days despite some color alteration due to ambient dust (Fig. 5e), which is attributed to the structural stability of the wood-PLA scaffold, and it does not degrade under different environmental conditions. For the living MBCs where the mycelium was not deactivated by drying, the organism was still alive. These living MBCs were left outside the laboratory. The results showed that the strength increased for the first 25 days, but suddenly started to decrease after that (Fig. 5f). After 100 days, the strength of the MBCs was reduced by 2.82 times from the maximum strength on the 25th day. The decrease in strength is due to the degradation of the wood-PLA by the living mycelium. Electron micrographs of the cell walls of the living MBCs on different days show the colonization of wood-PLA by the mycelium in the MBCs. Mycelium naturally decomposes lignocellulosic material by producing enzymes like hemicellulases, cellulases, and ligninases, which break down hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin in wood24. The weakened wood-PLA scaffolds create pathways for the degradation of PLA as well31. This results in a synergistic effect, with the mycelium breaking down both wood and PLA components of the MBCs, ultimately aiding the decomposition of the entire structure more effectively than it would for wood or PLA alone.

The change in chemical structure and chemical bonding at day 0 and day 300 for the MBCs with inactive mycelium was studied using XPS (Supplementary Fig. 8d–f). Deconvolution plots show no change in the bonding type. However, the percentage of C = O bonding decreases, with less change in inside samples (IL) and more in the outside samples (OL and OLIB). This could be due to prolonged exposure to the sunlight, which causes photo-oxidative degradation and breaks down C = O bonds. FTIR results (Supplementary Fig. 8g) show no change in the intensity and bonding for inactive MBCs. However, the shift in the FTIR curve and loss of defined ester/carbohydrate bands for OL_active (living) MBC show a structural change in bond strength, chemical degradation, and metabolic activity from living mycelia.

The slow degradation ability of the MBCs while the mycelium is living presents significant advantages for sustainable construction. The controlled biodegradability could be used for temporary structures or modular buildings, which allows eco-friendly disposal at the end of the life cycle with minimal waste. However, for long-term durability, the mycelium can be killed after it is fully grown on the porous scaffold. Our new method has developed MBCs which can be used for both short and long-term construction practices. The next section presents a proof of concept, a small mycelium house (myco-house), and compares the performance of MBCs with conventional building materials across key parameters.

Application

The improved mechanical strength and multifunctional characteristics of our MBCs highlight their potential as sustainable and high-performance alternatives to conventional construction materials. To illustrate this, we created proof-of-concept samples and compared the performance with existing construction materials (Fig. 6).

a 3D model and picture of a miniature prototype house made of MBCs (myco-house) (scale bar is 10 mm). b Temperature variation recorded by sensors placed on interior (dashed line) and exterior (continuous solid line) walls of the myco-house (cell size grading) and polyurethane (PU) house over 3 days. The inset shows a magnifying view of the temperature curves peaks on day 1 (data shown are only after the response became stable). c Model illustrating the heat damping in the myco-wall made from myco-bricks. d Radar plot comparing the performance parameters of wood-PLA, our MBC, clay brick and PU foam (Lightweight is 1/Density and Thermal insulation is 1/Thermal conductivity). Data is presented as range of values (shaded area) between minima and maxima (see source data file).

As a proof-of-concept example, we developed a miniature MBCs house utilizing solid, uniform, and graded MBC walls (Supplementary Fig. 9a), and recorded interior and exterior walls temperatures for three consecutive days using several temperature sensors (Fig. 6a). A polyurethane (PU) house of the same wall thickness and overall geometry was also prepared to compare the thermal insulation performance (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Temperature recorded by i-buttons attached to the outside and inside of CG_my wall and the front wall of PU-house shows cyclic fluctuation following the day-night cycles (Fig. 6b). The outer temperature readings are higher for both houses, and slightly higher for the PU-house than the MBC one. The temperature gradient (ΔT = Outside wall temperature - Inside wall temperature) across the walls for the myco-house (ΔT = 3.03 °C) is almost double that for the PU-house (ΔT = 1.46 °C). Higher ΔT means lower thermal conductivity and better insulation. In addition to the ΔT, the myco-house also shows lag (δt = 40 min) between the external and internal peak temperatures (inset in Fig. 6b). Such lag reveals some heat storing capacity of MBCs, which can dampen the effects of external temperature changes (Fig. 6c), providing a more stable indoor climate and reducing the need for active heating or cooling.

The graded design of myco-house also allows for different ΔT across the four walls. For solid (porosity = 0%) and uniform MBCs, ΔT is low, indicating high heat transfer, less suitable for thermal insulation. Both graded walls have higher ΔT, which means better insulation and low heat transfer (Supplementary Fig. 10a). The lag between the peaks of external and internal temperatures for each wall design reflects their thermal inertia (inset in Fig. 6b). On the other hand, PU-house shows minimal ΔT in the front wall (wall facing sun) and almost none for other walls, with no observed time lag (Supplementary Fig. 10b). These results demonstrate that the myco-house offers better thermal insulation performance and higher ΔT across its walls, combined with noticeable thermal lag, highlighting potential use of our MBCs as sustainable, passive thermal regulators, reducing reliance on the harmful chemical foams and energy-intensive thermal systems.

The radar chart in (Fig. 6d) compares the performance of the wood-PLA scaffolds and our MBCs with clay bricks and PU foams. The MBCs produced in this work demonstrate the most balanced (high strength-to-weight ratio, high insulation, and durable) performance overall, indicating their potential as the most efficient material for construction applications requiring high insulation and temperature stability. Clay bricks and PU foams display a trade-off between strength and insulation, making them low-performing choices as compared to MBCs. The findings suggest that MBCs are ideal for applications in climates with significant temperature fluctuations due to their strong insulating properties and ability to maintain indoor temperature stability.

Discussion

In summary, we have attempted to address one main drawback of MBCs, which is low mechanical strength and uneven mycelium growth, caused by loosely bonded matrix, restricted airflow, and moisture buildup. Poor mycelium growth can also adversely affect the functional properties like thermal insulation, fire resistance, and hydrophobicity. To address the issue, we used a stiff 3D printed wood-PLA porous scaffold to support mycelium colonization. The growth dynamics and metabolic activity of the mycelium can be tailored within the porous scaffold. The scaffold not only aided the stiffness and growth but also influenced the design-dependent mechanical and functional properties. The ability to achieve mechanical strength as high as clay bricks, thermal conductivity as low as insulating foams, along with fire resistance, durability, and sustainability, is particularly noteworthy, as they address the typical challenges faced by bio-based materials, which often struggle to achieve the robustness required for broader industrial adoption. The absolute mechanical properties remain modest at high porosities, as expected from bio-based materials. Nevertheless, applications that prioritize thermal insulation, lightweight, and biodegradability can extend the use of such materials. The key limitations of our study are that the highest improvement in mechanical strength and thermal conductivity is observed at high porosity (90%). Interestingly, our graded designs were able to achieve the low thermal conductivity even at lower porosity. This study enables the future exploration of the optimization of porosity-performance balance to achieve a practical trade-off between different properties. The current study uses the vertical fire test method due to the sample size and architected nature of the MBCs; quantitative tests like cone calorimetry were not feasible. Future work will include more detailed measurements of heat release and smoke. Furthermore, the manufacturing time of MBCs is longer than that of conventional materials, however, MBCs offer significantly lower embodied energy and negative embodied carbon, making them a sustainable, carbon-sequestering alternative to conventional building materials32. The use of sustainable materials, low-energy growth processes, and the potential for using pre-grown or prefabricated MBC units justify the trade-off, offering a more eco-friendly and multifunctional alternative to conventional materials.

Functionalization of MBCs through our method carries high prospects for various applications, ranging from sustainable construction materials with enhanced mechanical and thermal properties to packaging and product design substitutes. The ability to engineer MBCs with both mechanical stability and biological characteristics provides an original outlook in the quest for next-generation sustainable, functional materials, paving a way ahead where materials are not only engineered but concurrently possessed with bio-inspired capabilities.

Methods

Materials and chemicals

Commercially available composite wood-PLA filament (Filamentive Ltd, England) of diameter 1.7 mm was used to fabricate porous scaffolds. This filament was chosen based on the knowledge that mycelium flourishes on lignocellulosic biomass. Additionally, the role of biodegradable PLA is to enhance the material’s printability. The filament is sold as 100% made from recycled materials, with 40% wood and 60% PLA composition. Peptone, malt extract, and agar powder were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. G. Lucidum spawns were obtained from a commercial farm, Malaysian Feedmills Farms Ltd. Deionized water was used in the preparation of the PMA solution and measurement of hydrophobicity of the MBCs. Self-expanding Polyurethane (PU) foam, with the commercial name No More Gaps, was procured from Selleys Singapore. Butane gas cartridges with the brand name Golden Fuji were purchased from the local hardware store.

3D printing

A sheet-based gyroid triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) structure was selected due to its highest surface area and strength among commonly used TPMS structures33. The structures were modeled in an open-source MSLattice software34. An industrial-grade fused deposition modeling (FDM) printer, Flashforge Creator 3 Pro, was used to 3D print porous structures with a 0.6 mm size tungsten carbide nozzle. The printing parameters of the wood-PLA filament were kept the same as typical PLA filament.

Liquid mycelium culture

Firstly, a master agar plate (MAP) was prepared. It was prepared by adding 2.5 w/v% agar in deionized water, followed by sterilization at 121 °C for 1 h and 30 min of warming at 50 °C in an autoclave (Hirayama, HG-80). Sterilized agar solution was poured into 90 mm petri dishes. A small piece from the fungal spawn was used as an inoculum and placed at the center of the petri dish. The complete process was carried out in a bio-safety cabinet (BSC) (Gelman, BH Class II) under ultraviolet light to avoid contamination. MAPs were stored in a dark enclosed cabinet for 21 days (Supplementary Fig. 11a).

Liquid mycelium culture (LMC) was prepared by adding 0.3 w/v% peptone and 1.7 w/v% malt in deionized water. Similar steps (like MAP) were followed to sterilize the solution. A small inoculum from the MAP plate was placed in the sterilized solution to inoculate it. The liquid mycelium culture (Supplementary Fig. 11b) was stored for 14 days at 23 °C and 80% relative humidity in a dark enclosed cabinet before being used to inoculate the porous scaffolds. LMC was sub-cultured by 1 ml solution from the previous batch every 2–3 weeks.

Nutrition rich PMA solution

Mycelium requires a consistent supply of nutrients, optimal humidity levels, and a suitable pH environment to support efficient growth and development. The PMA nutrition-rich solution is prepared by mixing peptone (P), malt (M), and agar (A). Peptone and malt serve as nutrients, and agar provides an ideal growth medium during mycelium growth. The optimal composition of 0.1 w/v% peptone, 10 w/v% malt, and 2.4 w/v% agar was obtained from the trial experiments. The PMA solution was also sterilized under the same conditions as MAP and liquid mycelium culture.

Porous MBCs preparation

Though the FDM printed samples were sterilized at the printing stage, still to avoid contamination, the porous scaffolds were UV sterilized for 30 min in a BSC. The PMA solution was coated onto the porous scaffolds using the dip coating method. A one-time dip of 10 s was enough to form a thin and uniform coating. From the experiments, it was observed that the PMA solution at temperatures between 40–50 °C was perfect, i.e., not too viscous to pass through the pores of the samples and not too thin to stick on the samples. Once again, samples were UV sterilized. Samples were inoculated at the top surface with 1 ml of liquid mycelium culture using a micropipette. The current study selected G. lucidum due to its natural tendency to thrive on woody substrates35. All the experiments were conducted in BSC. Each inoculated sample was stored in a parafilm-sealed container and placed at 23 °C and 80% relative humidity in a dark enclosed cabinet for 21 days for the mycelium to grow. To ensure that MBCs did not undergo any further biological changes and remained stable, mycelium growth was stopped by heating samples overnight in an oven (IKA, Malaysia) at 48 °C; these samples are called inactive samples. There were a few samples in which the mycelium growth was not stopped; these samples are called living samples.

Composition analysis

To enhance the electrical conductivity of the samples for electron microscopy, a sputter coating of 5 nm gold was applied using a mini sputter coater (Quorum SC7620). A field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-6360) was utilized to obtain electron micrographs. The resulting micrographs were analysed with ImageJ software to assess the density of the mycelium layer, employing a threshold method to differentiate mycelium from pores, as well as to measure the diameters of the hyphae. The microstructure of the 3D printing filament was measured using the micro-CT scanning method (Zeiss Xradia 620 Versa). A 1 cm long filament was cut out from the spool and vertically mounted on the rotating X-ray stage. X-rays were then emitted and captured as 2D projection images while the sample rotates, typically through 360 degrees. Finally, these images were processed using open-source SLICER software to reconstruct high-resolution 3D images of the internal structure (see Supplementary Table 5 for the parameters used for capturing the images and doing the 3D reconstruction). Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometry (Perkin Elmer Frontier) was used to describe functional groups. The samples were analysed for surface chemistry using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS Kratos AXIS Supra). The data from the XPS machine were further analysed using (CasaXPS v2.3.26).

Mycelium proliferation

The overall weight of the samples decreases during the incubation period. This is caused by the loss of water from the PMA solution which is more than the gain in mycelium mass. Sacrificial samples were prepared to subtract the loss of moisture from the reading. The sample preparation for these samples followed the same steps as the MBCs except for no mycelium inoculation. They were also stored in the same environment conditions. When moisture loss is subtracted from the reading, overall increasing trend of mycelium mass was observed.

Mechanical test

Compression tests were conducted using an Instron 5569 Universal Testing Machine (UTM) (50kN load cell) by the ASTM D1621 standard. The average of five samples was considered as the final reading. A loading rate of 2 mm/min was chosen to ensure a steady and controlled compression process. The yield strength (σy) is the stress value corresponding to first peak in the stress-strain curve and peak strength (σp) is the stress value at the densification point, i.e., the point where all the pores are completely compressed, and the porous structure starts behaving like a solid material36. The energy absorption (EA) is the area under the stress-strain curve up to densification strain (εd) and is calculated using Eq. 1. \({\varepsilon }_{d}\) is the strain corresponding to densification point, which is calculated from the energy efficiency method in Eq. 2, which stated the energy absorption efficiency (η) is the area under stress-strain curve divided by peak stress \(({{{\sigma }}}_{{{\rm{p}}}})\), where \({\varepsilon }_{a}\) is the strain up to which energy absorption is calculated. The strain corresponds to global maxima on the efficiency vs strain curve is the densification strain (Eq. 3)36 Specific energy absorption (SEA) was calculated by dividing EA by the density of the samples.

Adhesion strength between mycelium and wood-PLA was measured from double lap shear tests carried out according to ASTM D3528-96. Dimensions were considered according to Type A standards, with lapping area as 25 × 25 mm (x2 for double lap test). All the shear lap samples were prepared under similar PMA solution and inoculation conditions. Tests were carried out using an Instron 3366 UTM with a 500 N load cell at a displacement rate of 1 mm/min. Confidence intervals (95%) for all the mechanical tests (n = 5) were calculated using the t-distribution.

Thermal insulation

The room temperature experimental thermal conductivity of the MBCs was measured under transient heat transfer conditions following ASTM D5930-17 standard using Xiatech TC3000E transient hotwire thermal conductivity meter (see Supplementary Fig. 12 for the images of the samples). The average of three measurements was considered for the final value. Before the test, each sample were completely dried in an oven at 50 °C until the reading became constant. The infrared thermal images of the composites were captured using a thermal imaging system (FLIR, ETS320), and each sample was recorded at least three times. The constant emissivity of 0.95 was applied to all MBCs. Each sample was recorded for 5 min of heating and 5 min of cooling. During heating, the sample was placed on a heated plate (Torrey Pines Scientific Hot Plate HP50) at 100 °C and recorded for 5 min; the same sample was shifted to a plate at 25 °C and recorded for another 5 min during the cooling stage. DS1921H-F5 Thermochron i-buttons were used to measure the temperature in real-time (see Supplementary Fig. 9b for the details of the i-button arrangement in myco-house). The logging rate was set at 5 (one reading in 5 min). A polyurethane (PU) house of same overall dimensions was also prepared (using 3D printed mold) to compare thermal insulation. The i-buttons are attached to the walls of houses using thermally conductive epoxy adhesive (TIM-813HTC-1HP). The thickness of each wall is 10 mm in both houses.

Fire resistance

For fire testing, samples of size 12 × 12 × 120 mm were prepared and tests were carried out in a dark cabinet of size 0.5 m3 according to ASTM D3801-20a standard. Prior to tests, the samples were dried in the oven at 50 °C until the five consecutive weight readings became constant (i.e., the difference in weight between consecutive measurements is <0.1%). Butane gas with torch setup was placed vertically at 10 mm from the bottom head of the sample and a blue flame of length 20 mm was used to burn the samples. Each test was performed for 10 sec of flaming time and fire was put out at the 20th sec. Every test was repeated five times, and the average value was considered. To quantify the test results, the total burned surface area of the samples was measured using ImageJ software. Weight change of the samples was also measured to quantify the material loss during tests.

Hydrophobicity

The contact angle (θc) was optically measured by placing a 1 ml drop of DI water on the flat surface of samples using a Goniometer (Theta Flex, Biolin Scientific). Water absorption tests were conducted according to ASTM D570 standards by dipping complete mycelium and without mycelium samples in the water and recording the weight of the samples after 1 day, 1 week, 2 weeks, 3 weeks, and 14 weeks until the weight became saturated. The moisture uptake and release were measured using the NORD test. It uses two humidity levels per day. In our study, we selected 53% (16 h) and 75% (8 h). The objective of the test is to evaluate the compatibility of MBCs within an office environment. Similar test criteria have been widely used for natural woods37,38. Weight is measured twice a day and plotted vs time. This test was also conducted for 96 h until the moisture uptake became saturated.

Durability

To study the durability of MBCs, MBCs were left for 300 days under three environmental conditions: inside lab (IL), outside lab (OL), and outside lab but enclosed inside a box (OLIB). Durability was measured from mechanical test data, change in weight, FTIR, and XPS analysis of the MBCs. We also studied the environmental degradation of the samples that were not oven-heated, which means mycelium was still alive when the samples were placed outside the lab.

Numerical analysis

Two types of numerical analysis were carried out. To visualize the flow of air inside the porous gyroid structure, CREO parametric software was used. The thermal heat transfer conditions were modeled in ABAQUS 6.14 software. The rest of the details are mentioned in Supplementary notes. All the data used to plot figures can be found in source data file.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to support the findings of this manuscript are included in the main text, supplementary information and source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

United Nations Environment Programme. 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector. UNEP (2022).

Singh, S., Maiti, S., Bisht, R. S., Panigrahi, S. K. & Yadav, S. Large CO₂ reduction and enhanced thermal performance of agro-forestry, construction and demolition waste based fly ash bricks for sustainable construction. Sci. Rep. 14, 8368 (2024).

Wi, S., Kang, Y., Yang, S., Kim, Y. U. & Kim, S. Hazard evaluation of indoor environment based on long-term pollutant emission characteristics of building insulation materials: an empirical study. Environ. Pollut. 285, 117223 (2021).

Churkina, G. et al. Buildings as a global carbon sink. Nat. Sustain. 3, 269–276 (2020).

Ramage, M. H. et al. The wood from the trees: The use of timber in construction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 68, 333–359 (2017).

Mi, R. et al. Scalable aesthetic transparent wood for energy efficient buildings. Nat. Commun. 11, 3836 (2020).

Dong, X. et al. Low-value wood for sustainable high-performance structural materials. Nat. Sustain. 5, 628–635 (2022).

Barbieri, V., Gualtieri, M. L. & Siligardi, C. Wheat husk: a renewable resource for bio-based building materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 251, 118909 (2020).

Dams, B. et al. Upscaling bio-based construction: challenges and opportunities. Build. Res. Inf. 51, 764–782 (2023).

Lambert, S. & Wagner, M. Environmental performance of bio-based and biodegradable plastics: the road ahead. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 6855–6871 (2017).

Yang, L., Park, D. & Qin, Z. Material function of mycelium-based bio-composite: a review. Front. Mater. 8, 737377 (2021).

Gantenbein, S. et al. Three-dimensional printing of mycelium hydrogels into living complex materials. Nat. Mater. 22, 128–134 (2023).

Manjula-Basavanna, A., Duraj-Thatte, A. M. & Joshi, N. S. Mechanically tunable, compostable, healable and scalable engineered living materials. Nat. Commun. 15, 9179 (2024).

Teoh, J. H., Soh, E. & Le Ferrand, H. Manipulating fungal growth in engineered living materials through precise deposition of nutrients. Int. J. Bioprint. 10, 3939 (2024).

Gan, J. K. et al. Temporal characterization of biocycles of mycelium-bound composites made from bamboo and Pleurotus ostreatus for indoor usage. Sci. Rep. 12, 19362 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Mycelium composite with hierarchical porous structure for thermal management. Small 19, 2302827 (2023).

Lingam, D., Narayan, S., Mamun, K. & Charan, D. Engineered mycelium-based composite materials: comprehensive study of various properties and applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 391, 131841 (2023).

McBee, R. M. et al. Engineering living and regenerative fungal–bacterial biocomposite structures. Nat. Mater. 21, 471–478 (2022).

Shen, S. C. et al. Robust myco-composites: a biocomposite platform for versatile hybrid-living materials. Mater. Horiz. 11, 1689–1703 (2024).

Liu, R. et al. Preparation of a kind of novel sustainable mycelium/cotton stalk composites and effects of pressing temperature on the properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 141, 111732 (2019).

Soh, E. & Le Ferrand, H. Woodpile structural designs to increase the stiffness of mycelium-bound composites. Mater. Des. 225, 111530 (2023).

Han, L. & Che, S. An overview of materials with triply periodic minimal surfaces and related geometry: from biological structures to self‐assembled systems. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705708 (2018).

Cheng, Q. et al. Molecular architecture of chitin and chitosan-dominated cell walls in zygomycetous fungal pathogens by solid-state NMR. Nat. Commun. 15, 8295 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Lightweight, thermal insulation, hydrophobic mycelium composites with hierarchical porous structure: design, manufacture and applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 266, 111003 (2023).

Gibson, L. J. Cellular solids. MRS Bull 28, 270–274 (2003).

Sun, W., Tajvidi, M., Howell, C. & Hunt, C. G. Functionality of surface mycelium interfaces in wood bonding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 57431–57440 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Numerical study on the anisotropy in thermo-fluid behavior of triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS). Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 215, 124541 (2023).

Elsacker, E., Vandelook, S., Brancart, J., Peeters, E. & De Laet, L. Mechanical, physical and chemical characterisation of mycelium-based composites with different types of lignocellulosic substrates. PLoS One 14, e0213954 (2019).

Winandy, L., Hilpert, F., Schlebusch, O. & Fischer, R. Comparative analysis of surface coating properties of five hydrophobins from Aspergillus nidulans and Trichoderma reesei. Sci. Rep. 8, 12033 (2018).

Pereira, C., de Brito, J. & Silvestre, J. D. Contribution of humidity to the degradation of façade claddings in current buildings. Eng. Fail. Anal. 90, 103–115 (2018).

Stoleru, E., Vasile, C., Oprică, L. & Yilmaz, O. Influence of the chitosan and rosemary extract on fungal biodegradation of some plasticized PLA-based materials. Polymers 12, 469 (2020).

Livne, A., Wösten, H. A., Pearlmutter, D. & Gal, E. Fungal mycelium bio-composite acts as a CO2-sink building material with low embodied energy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 12099–12106 (2022).

Sharma, D. & Hiremath, S. S. Additively manufactured mechanical metamaterials based on triply periodic minimal surfaces: Performance, challenges, and application. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 29, 5077–5107 (2022).

Al-Ketan, O. & Abu Al-Rub, R. K. MSLattice: a free software for generating uniform and graded lattices based on triply periodic minimal surfaces. Mater. Des. Process. Commun. 3, e205 (2021).

He, J. et al. Species diversity of Ganoderma (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) with three new species and a key to Ganoderma in Yunnan Province, China. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1035434 (2022).

Li, Q. M., Magkiriadis, I. & Harrigan, J. J. Compressive strain at the onset of densification of cellular solids. J. Cell. Plast. 42, 371–392 (2006).

Kaczorek, D. Moisture buffering of multilayer internal wall assemblies at the micro-scale: experimental study and numerical modelling. Appl. Sci. 9, 3438 (2019).

Rode, C. et al. NORDTEST Project On Moisture Buffer Value Of Materials. In AIVC Conference ‘Energy Performance Regulation’: Ventilation in Relation to the Energy Performance of Buildings 47–52 (INIVE 2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Research Foundation of Singapore and ETH Zurich, Switzerland with the grant Future Cities Laboratory Global, Module A4: Mycelium digitalization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S. and H.L.F. Validation, D.S. Formal analysis, D.S. Investigation, D.S. Visualization, D.S. Writing–original draft, D.S. Writing–review & editing, D.S. and H.L.F. Funding acquisition, H.L.F. Supervision, H.L.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Blaise Tardy, who co-reviewed with Malak AbuZaid; and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, D., Le Ferrand, H. 3D printed gyroid scaffolds enabling strong and thermally insulating mycelium-bound composites for greener infrastructures. Nat Commun 16, 5775 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61369-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61369-x

This article is cited by

-

Impact of Fomes fomentarius growth on the mechanical properties of material extrusion additively manufactured PLA and PLA/Hemp biopolymers

Fungal Biology and Biotechnology (2025)