Abstract

Thiols are used in many click reactions, and are also excellent platforms for biomolecular click or bioconjugation reactions. The direct cross-coupling of two thiols is an attractive biomimetic concept for click chemistry, but leads to statistical mixtures of homo- and heterodimers. Here, we introduce a novel class of thiol-click reagents, bromo-ynones, where the kinetic differentiation between the first and second thiol addition onto these reagents facilitates a stepwise one-pot cross-clicking of two distinct thiols in aqueous media, without the need for intermediate isolation or purification. The two thiols are linked through a single carbon atom, mimicking a disulfide bridge. We demonstrate the use of bromo-ynones in the synthesis of various cross-coupled thiols, including small molecule drugs, fluorophores, carbohydrates, peptides and proteins, including an example of a protein-protein heterodimer. The resulting adducts are robust under physiological conditions and by judicious choice of the bromo-ynone reagent, the adducts can be stable even in the presence of excess free thiols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Click chemistry has propelled the creative power of organic synthesis beyond the realm of chemical laboratories, and into the hands of a much wider range of scientists1,2,3,4,5,6. A few good reactions have thus boosted the technical toolbox of many modern researchers. Alkynes and azides have taken a leading role in click chemistry, as they are common functional groups with a mild and chemoselective reactivity profile7,8,9. A good argument can be made in favor of thiols (or mercaptans) as the third most prominent functional group in click chemistry, used in thiol-ene10,11,12, thiol-yne13,14,15, and thiol-X click chemistries16,17,18. Moreover, due to the widespread (yet specific) occurrence of thiols in biomolecules, thiols have a primary place in the development of biomolecular click reactions (or bioconjugation reactions), with the thiol-maleimide click reaction as a prime example. Thiol-selective click chemistries are still heavily researched19,20,21,22,23. Next to reaction kinetics and selectivity, also the stability profile of the resulting adducts is an important point of attention24,25,26,27,28.

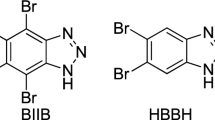

The classical oxidative coupling of two thiol-functional molecules can be regarded as a click-like reaction, due to the mildness of the oxidation method that is required and due to the excellent selectivity with which thiol-functions can be coupled in the presence of a wide range of other reactive functions. However, the biomimetic disulfide-forming reaction of two thiols falls short of two important click chemistry criteria. First, the disulfide linkages are relatively labile and show limited stability under physiological conditions29,30. Second, and more importantly, for intermolecular thiol-thiol coupling, disulfide formation lacks selectivity and generates statistical mixtures of homo- and heterodimers. This can be avoided by employing one of the thiols in large excess and by performing a purification of intermediates and final products31,32,33. Both of these drawbacks prevent the widespread use of thiol-thiol clicking, and are also intrinsic in many other thiol-thiol coupling reactions. The most well-known example in this regard is Baker’s dibromomaleimide reagent34 (Fig. 1a). These next-generation maleimides can be used to make thiol-thiol homodimers or to rebridge intramolecular disulfides after their reductive cleavage, but the adducts show lability to excess thiols, and the preparation of heterodimers is not readily achievable under stoichiometric conditions35,36. More recently, Hackenberger reported the use of vinyl phosphonite ester as a reactive linchpin to cross-couple two thiols, although this requires activation of one of the thiols as a reactive disulfide37 (Fig. 1b). Similarly, Poulsen introduced oxSTEF reagents as a click reagent for thiol-thiol coupling with just one carbon in between the two thiols (Fig. 1c). However, for heterocouplings, a multistep work-around is required that also requires chromatography38. Our own group recently reported a thiol-thiol coupling strategy using simple phenylpropynone reagents based on consecutive thiol-yne and thiol-ene Michael additions (Fig. 1d). These showed excellent chemoselectivity in the formation of symmetrical dithioacetals and for the rebridging of cyclic disulfide peptides. The thiol exchange reaction can be blocked by a chemoselective reduction of the ketone39. However, we were not able to control the selective formation of heterodimers under stoichiometric conditions, despite the fact that we observed a clear kinetic difference between the first and second thiol addition step. We were then intrigued by the recent report of Loh, in which similar 3-silyl-substituted propynone reagents were found to undergo selective mono-addition of thiols, resulting in stable adducts40.

a Dibromomaleimide reagents as introduced by Baker; b vinylphosphonite reagents as introduced by Hackenberger; c vinylogous thioester reagents (named oxSTEF) as introduced by Poulsen; d phenylpropynones reagents as introduced by our group in previous work; e Silyl-ynone reagents as introduced by Loh; f Bromo-ynones as thiol-thiol bioconjugation reagents as introduced in this work.

In this work, we report that 3-bromo-1-phenyl-propynone reagents (or bromo-ynones, BYO) allow access to stabilized ketene-dithioacetals (KDTA), with control over the first and second addition step (Fig. 1f). To our considerable surprise, the substitution of the bromide proceeds much faster than the targeted thiol-yne click reaction, giving clean conversion to a thio-ynone (TYO) intermediate. This undergoes a second addition of a thiol following the typical thia-Michael-yne pathway. The TYO can be isolated, but we can also report that these steps can be performed in sequence in a buffered aqueous medium, resulting in the direct cross-coupling (or cross-clicking) of two consecutively added thiols, including carbohydrates, peptides and proteins, without the need for excess reagents or purification steps.

Results and discussion

Study of homodimer synthesis

The BYO reagent 1 was found to be soluble and hydrolytically stable for several days in 1:1 mixtures of aqueous phosphate buffer and acetonitrile, as well as various other water-miscible organic solvents (see Supplementary Section 2). Upon treatment of BYO 1 with one equivalent of N-acetyl-O-methyl cysteine, we observed the very rapid formation of a mono adduct. Instead of the expected thia-Michael adduct with a remaining reactive bromide, we isolated only the thio-ynone (TYO) substitution product 2 (Fig. 2a), possibly indicating a direct substitution pathway rather than the expected Michael addition/elimination pathway41. When the stoichiometry of 1 and the thiol was well controlled, no trace of a double adduct 3 could be observed, indicating a much slower second addition. However, in our studies of reactions of BYO 1 with two equivalents of thiol (Fig. 2b), we found that the formation of the bis-adduct 3 was also very fast, albeit more pH dependent. At lower pH (6.5), unreacted TYO 2 could still be observed after 20 min. Nevertheless, at pH 8.0, the thiol-thiol conjugation could be achieved in quantitative yield within 5 min at room temperature, indicating very fast kinetics of both bond forming steps. The chemoselectivity of the process was monitored by a competition reaction in which 2 equivalents of N-acetyl-O-methyl cysteine and two equivalents of Nα-acetyl-O-methyl-lysine were treated with BYO 1. The adduct 3 formed quantitatively within minutes and even after 48 h at room temperature, no other product than the ketene-dithioacetal (KDTA) 3 could be observed (see Supplementary Section 2), showing both the selective formation and stability of the formed thiol-thiol conjugate 2. A range of other functional thiols showed broad functional group tolerance and orthogonality of the methodology (see KDTA 4–10). For the glutathione dimer 10, the reaction proceeded exclusively on the thiols. The reagent 1 was also found to be very useful in the rebridging of several cyclic disulfide peptides, which all showed near-quantitative formation of the cyclic KDTA peptides (see Fig. 2c and Supplementary Section 6).

The above findings compare well with our previous study of thiol-thiol homodimer formation with phenylpropynone (see Fig. 1d), as those reagents required 30–60 min of incubation at 40 °C to achieve full dithioacetal formation39.

Stability studies and stability improvement

The formed KDTA adducts can still be seen as reactive Michael acceptors and may be reactive towards nucleophilic species over time. We thus investigated the robustness of the formed KDTA moiety under different conditions (Fig. 3a). The methylthiol-homodimer 11 was selected for this study, as any release of free thiol would also be effectively irreversible due to its volatile nature. Nevertheless, this KDTA 11 was found to be completely stable in buffer:acetonitrile over several days, with no formation of hydrolysis products at pH 8. This KDTA 11 also largely survived treatment with an excess of the common disulfide cleavage reagent TCEP (tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine). Treatment of 11 with an excess of L-cysteine showed clear evidence of a slow but gradual thiol exchange reaction, where only about 70% of the KDTA remained after 3 days of incubation at room temperature, with the clear formation of heterodimers. This slow exchange with thiols is an important factor for possible bioconjugation applications and was thus also monitored and quantified for the KDTA 4, using glutathione as a competitive thiol. Exposed to five equivalents of GSH under near-physiological conditions, our dithioacetal 4 exhibited gradual thiol exchange, again over the course of days, with clear formation of mixed dithioacetals and the release of the original thiols over time (see Supplementary Section 4). This phenomenon is well known for other thiol-bioconjugation methods (see Fig. 1) and is generally seen as a drawback, especially if it cannot be controlled24,25,26,27,28.

stabiliyty studies of BYO-derived KDTAs (a), comparison to dibromo-maleimide derived thiol-thiol adducts (b), bromo-ynamides (BYAs) as alternative thiol-thiol cross-click reagents that give adducts stable to thiol exchange (c), chemical strategy to stabilized BYO-derived KDTA adducts by conjugation with PTAD (d).

In order to benchmark the stability profile of our thiol-thiol adducts, we prepared the corresponding dithiomaleimide 13 from N-acetyl-cysteamine and Baker’s dibromomaleimide 1234,35, and submitted this to the same thiol exchange conditions (Fig. 3b). Here, a much more rapid thiol exchange was observed, giving near statistical exchange within only 30 min at room temperature. Thus, the BYO-based thiol-thiol cross-linking can be said to be more robust towards physiological conditions.

As the electron-withdrawing nature of the carbonyl moiety will likely affect the rate at which the ketenedithioacetal can exchange with free thiols, we also decided to investigate the bromo-propynamide reagent 14 (Fig. 3c). As expected, this reagent showed a slightly slower thiol-thiol coupling rate in the forward conjugation reaction, but still a complete coupling was achieved within 1 hour at room temperature. Likewise, the resulting ketene dithioacetal 15 showed an attenuated reactivity towards glutathione incubation, with more than 90% of the homodimer persisting after three days of exposure to excess glutathione. This shows that an interesting trade-off in reactivity can be achieved with these reagents, and that the physiological stability of the adducts can be rationally designed by judicious choice of the BYO reagents.

Finally, given our experience in using triazolinediones as versatile reagents and as bioconjugation reagents, we briefly explored the reactivity of a ketene dithioacetal with triazolinediones42,43,44. As expected for a conjugated olefin44, the phenyl-triazolinedione reagent (PTAD 16) quickly reacted with the push-pull substituted alkene in adduct 11 (Fig. 3d). This reaction established an interesting post-modification protocol for our bioconjugation method. Moreover, we found that the resulting adduct was strongly inactivated towards thiol-substitution reactions in our standard glutathione incubation protocol. This points to yet another strategy with which the reversible nature of the adduct can be controlled. The donating effect of the nitrogen lone pair onto the KDTA is indeed expected to make 17 a less electrophilic Michael acceptor. Moreover, at physiological pH, the urazole N-H in adduct 17 is expected to be fully ionized (pKa(NH) = 4.7-5.8)45, likely offering electrostatic protection of the adduct, a rationale that we were further able to confirm through experiment (see SI, sections 4.11 and 11.1.3).

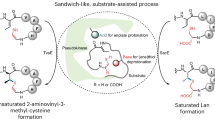

Thiol-thiol cross-clicking

The established bromo-ynone thiol conjugation methodology already shows great potential as a click chemistry tool. However, the distinct reaction rates of the very fast first and second thiol couplings, and the observed resistance towards further thiol exchange of the resulting adducts, prompted us to investigate the potential of these reagents to simply cross-click two different thiols, by their sequential addition in stoichiometric amount to a BYO reagent (Fig. 4).

We found that the thiol-BYO click reaction proceeds very smoothly, and that the expected TYO products could be isolated in high yield and purity, with no need for chromatographic purification. The successful formation of the thiocoumarin TYO 22 illustrates that aromatic thiols are also viable substrates in this click reaction. The ferrocene-thiol-BYO adduct 25 was isolated in lower yield, which was attributed to the low solubility of the thiol. Sufficiently hydrophobic TYO products could be obtained in pure form by simple liquid-liquid extraction, affording bench stable TYOs. The glutathione-derived TYO 23 could be stored in solution for a few days and then used as such in a second coupling step (vide infra).

In a next step, we investigated the coupling of different functional thiols unto the pre-prepared TYO products (Fig. 4b). We were delighted to find that the expected KDTA heteroadducts were generally obtained in high yield and purity, as judged by both NMR and LC-MS analysis. As expected, the adducts were obtained as mixtures of E and Z diastereomers (ratios vary from 6:4 to 8:2, see Supplementary Sections 8 and 9). Qualitatively and quantitatively the same results were obtained when the TYO intermediate was not isolated by extraction and a second equivalent of a different thiol was just added in the initial reaction medium (Fig. 4c). However, care must be taken here to control the pH of the buffer, as the first step generates one equivalent of hydrobromic acid. This can decrease the pH and lead to a retardation of the second addition (see Fig. 2b). Using this one-pot protocol, we successfully biotinylated two mono-thiol-functional peptides (see 36 and 37).

Thiol-functional protein conjugation study

Having demonstrated the successful cross-clicking of various thiol-functional (bio)molecules, we next turned our attention to protein conjugation studies. As a simple model protein, we used a single cysteine-containing Alphabody sequence (named MB23). Alphabodies are designed antiparallel triple helix coiled-coil protein scaffolds that can be engineered as artificial antibodies against various extra-or intracellular protein targets of therapeutic value46. The recombinant MB23 Alphabody contains a single surface-exposed cysteine residue and is thus an ideal model protein for cysteine based bioconjugation, as we have previously demonstrated42,47. We first prepared a DMEQ-fluorophore-derived thiol (see Supplementary Section 7), which was clicked with BYO to afford the fluorophore-TYO reagent 42. The isolated TYO reagent was added in excess to Alphabody MB23 (Fig. 5a). After one hour at room temperature, full conversion of the Alphabody was observed. This experiment was repeated successfully with 6 other of the previously prepared TYO reagents (also see Fig. 4a). The protein-TYO click reactions proceeded quite slowly, so that a ten-fold excess of the TYO reagent needed to be used to ensure swift cysteine-conjugation. In order to circumvent this issue (even though dialysis can remove the excess TYO), we changed around the order of the click reactions (Fig. 5b). By carefully controlling the stoichiometry of both the BYO reagent 1 and the Alphabody MB23, we managed to click the protein under stoichiometric conditions, now taking advantage of the higher reaction rate of the first thiol click to ensure full protein conjugation. Care needs be taken not to add an excess of the BYO reagent in this step, as otherwise side reactions can be observed, which do not at all occur in the reverse addition protocol. Next, the protein-derived TYO reagent can be clicked with just one equivalent of a second thiol (in this case a biotin-derived thiol). There is a striking rate difference between protein and small molecule thiols, which could be attributed to steric or diffusion -factors. Taking advantage of this observed intrinsic rate difference between the macromolecular and small molecule thiol reaction partners, we then conducted an experiment in which the Alphabody and the cysteamine derived biotin amide are first mixed in equimolar amounts and then treated with exactly one equivalent of the BYO reagent 1 (Fig. 5c). To our surprise, this afforded the same coupling efficiency as in the previous sequential cross-click experiment with the same substrates. Thus, a remarkable self-sorting behavior of the thiol compounds is demonstrated in this cross-click reaction.

Single cysteine bioconjugation with pre-clicked thio-ynones (a), selective conversion of cysteine into electrophilic conjugation site (b), one-pot cross-conjugation with a one-to-one hetero-thiol mixture (c), glutathione stability studies of conjugated Alphabodies (d), magnetic streptavidin beads pulldown followed by glutathione-triggered release (e), one-pot alphabody-nanobody cross-click with all reagents at 0.1 mM and by consecutive adding of BYO 1 and then nanobody EgA1-nb-Cys to a solution of MB23 (f).

The resulting protein-biotin KDTA conjugate was subjected to incubation with 100 equivalents of glutathione (Fig. 5d). This resulted in quite fast thiol exchange, faster than in our model studies (cf Fig. 3). However, when the same adduct was prepared using bromo-propynamide (BYA) reagent 14, the cross-click conjugation was also successful (see Supplementary Section 10) and the resulting conjugate was significantly more stable, as most of it survived a treatment with 100 equivalents of glutathione for several days.

With the biotin-conjugated Alphabody in hand, we also demonstrated a possible application of the remaining reactivity of the BYO-derived KDTA-adducts. Using magnetic streptavidin coated beads, an affinity pull down experiment was conducted on the MB23-biotin conjugate. Treatment with a solution of glutathione afforded a very mild way to elute MB23 from the beads (Fig. 5e).

Finally, we were able to show efficient protein-protein conjugation with BYO 1 (Fig. 5f). MB23 was first reacted with 1 equiv of 1 for 15 min, followed by addition of the recombinantly expressed anti-EGFR nanobody EgA1 with an encoded additional C-terminal cysteine residue (EgA1-nb-Cys)48. The EgA1 nanobody and its conjugates are of therapeutic interest as it prevents dimerization of the EGFR receptor. Its efficient chemical conjugation with another Cys-functional protein, through a single carbon atom as a linker, showcases the potential of our method to recombinatorily generate protein-protein constructs in a fully site-selective manner from native proteins and with complete selectivity for the heterodimer, as demonstrated by LC-MS and SDS-PAGE analysis (see Figs. S148 and S159).

Methodological benchmarking and diversification

The forward reaction kinetics of BYO 1 and thiols in buffer/acetonitrile at room temperature proceeds very rapidly within the initial seconds of mixing the two reagents. In a head-to-head competition experiment, we showed that 1 clearly outcompetes maleimides for N-acetyl-O-methyl-cysteine conjugation (Fig. 6a). The second addition of a thiol to TYO, although finished within minutes at pH 8, was shown to be considerably slower by a similar competition experiment (Fig. 6b). The observed product ratios indicate almost two orders of magnitude difference in reaction rate between the first and second addition. A more quantitative analysis was possible via UV-VIS measurements of the relevant absorbances (see Supplementary section 3, Figs. S23-S30)49. This provided a second order rate constant of 1780 M-1.s-1 (Fig. S27), compared to the literature value of 1300 M-1s-1 for the related reaction of phenyl maleimide50. For the second addition step, a second order rate constant of 135 M-1s-1 was determined (Fig. S29). The decay curves for the reaction between 1 and 2 equiv of N-Ac-O-Me-Cys, measured at 0.05 mM, showed a first reaction half life of about one second for the first addition and a reaction half life of about 80 seconds for the second addition (Fig. S30). A comparison of the reactivity of dibromo-maleimide 12 and bromo-phenylpropynone 1 also proved to be instructive (Fig. 6c). The ratio of formation of thiol adducts to both reagents was very comparable (54:46 based on internal standard), but while the bromo-ynone 1 gave exclusive mono-addition to the TYO 2, the dibromomaleimide 12 already gave comparable amounts of the mono- and bis-thiol conjugated products. Again, the unique kinetic discrimination of the first and second thiol additions with BYO can be clearly observed here.

Cysteine competition experiments of bromo-ynone and a maleimide bioconjugation reagent (a), cysteine competition experiments of thio-ynone and a maleimide bioconjugation reagent (b), cysteine competition experiments of bromo-ynone and a dibromomaleimide bioconjugation reagent (c), diastereoselective amine addition (d), thio-ynone competition with lysine and benzylic and aromatic amines (e), heterocyclization reactions with 1,2-dinucleophiles (f, g). For direct competition experiments between thiols and the nucleophiles listed here, see supplementary section 2.4.

Thiols are partially deprotonated at pH 7–8, while amines are mostly protonated (and H-bonded) and thus non-nucleophilic within this pH range, which explains the lack of reactivity of amines (such as lysines) in competition with thiols towards Michael acceptors in buffered media. Even though we showed that lysines are not competitive with thiols for the first nor the second thiol-click reaction on BYO 1 (cf Fig. 2b), we investigated the reactivity of different amines onto TYO 20. Reasoning that benzylic amines and especially anilines have a considerably lower pKaH-value than alkyl amines, we expected that their more abundant unprotonated amine could lead to a more prominent aza-Michael type reactivity, thus allowing thiol-amine cross-clicking. Two proof-of-principle experiments indeed showed a very promising outcome for the further development of BYO reagents for this purpose (Fig. 6d). Even though the amine addition was still relatively slow (requiring 24 h at room temperature), the resulting hetero-adducts 44 and 45 were obtained in high yield and high purity, and - moreover – as single diastereomers. Competition experiments with N-Ac-O-Me-Lys confirmed our earlier rationale that more basic amines are actually less reactive in buffered media (Fig. 6e). Furthermore, we conducted a wide range of intermolecular competition experiments, where all natural amino acid side chains and the nucleophile types from Fig. 6 were reacted head-to-head with N-Ac-O-Me-cysteine (See Supplementary Section 2.4). Only one nucleophile, the unnatural p-anisidine showed competitive formation of an aza-Michael adduct in aqueous buffer, whereas all other competition experiments showed exclusive formation of thiol-adducts.

One limitation of the BYO-click methodology that was encountered in our study is related to thiols that also have a nucleophilic group in their beta-position. A swift second intramolecular Michael addition occurs here, and prevents the addition of second thiol. Reaction of cysteine with 1 gave thiazoline 46, even when an excess of cysteine is used (Fig. 6f). This reactivity motif opens options for further click-like reactions of BYOs with various mild bis-nucleophiles. One example was found in the slow but high yielding reaction between 1 and catechol, giving a relatively robust ketene acetal adduct 47.

In summary, we have uncovered a relatively straightforward reagent class for click conjugation and click cross-conjugation of thiol-functional molecules. We have shown the utility of the method for small molecule, peptide and protein couplings under fully stoichiometric conditions. We have also shown that the methodology compares favorably to existing methods for thiol clicking and thiol bioconjugation reactions12,34,35,36,37,38,39,51,52,53. The click chemistry platform shows remarkable ability to tune both the forward and reverse kinetics, and opens up interesting possibilities in click chemistry, including the direct cross-conjugation of two native proteins in a fully site-selective and heteroselective manner. We expect the method will find good use in a wide range of applications, some of which are under current investigation in our laboratories.

Methods

General procedure for thiol-thiol cross-clicking with BYO 1 to form a KDTA heterodimer

3-Bromo-1-phenyl-2-propyn-1-one 1 (BYO) (50 µmol, 1 equiv.) was placed in a 25 ml flask and was dissolved in 3 ml acetonitrile and 3 ml phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8). A stock solution of the first thiol containing small molecule (50 µmol in 2 mL of pH 8 phosphate buffer/MeCN, 1:1, 1 equiv.) was added dropwise at room temperature over 2 min. The resulting mixture was stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the second thiol containing small molecule (50 µmol, 1 equiv.) was added in a single portion (with no need to make a prior solution) and the resulting mixture was stirred for another 15 min at room temperature. The mixture was extracted three times with 10 mL ethyl acetate, and the combined organic layers were washed with a saturated aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered over a plug of cotton wool and concentrated in vacuo to afford the KDTA heterodimer. For reactions performed with lower concentrations of thiols (e.g. for protein conjugation), reaction times were extended for the second coupling step (see Supplementary Information).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data relating to the materials and methods, optimization and control studies, experimental procedures, HPLC spectra, UV-spectra, NMR spectra, and mass spectrometry are available in the Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Sun, N. et al. Highly efficient peptide-based click chemistry for proteomic profiling of nascent proteins. Anal. Chem. 92, 8292–8297 (2020).

Lau, Y. H., Wu, Y., De Andrade, P., Galloway, W. R. J. D. & Spring, D. R. A two-component ‘double-click’ approach to peptide stapling. Nat. Protoc. 10, 585–594 (2015).

Kofoed, C., Riesenberg, S., Šmolíková, J., Meldal, M. & Schoffelen, S. Semisynthesis of an active enzyme by quantitative click ligation. Bioconjug. Chem. 30, 1169–1174 (2019).

Walker, J. A. et al. Substrate design enables heterobifunctional, dual “click” antibody modification via microbial transglutaminase. Bioconjug. Chem. 30, 2452–2457 (2019).

Fantoni, N. Z., El-Sagheer, A. H. & Brown, T. A Hitchhiker’s guide to click-chemistry with nucleic acids. Chem. Rev. 121, 7122–7154 (2021).

Xu, Z. & Bratlie, K. M. Click chemistry and material selection for in situ fabrication of hydrogels in tissue engineering applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 2276–2291 (2018).

Rostovtsev, V. V., Green, L. G., Fokin, V. V. & Sharpless, K. B. A stepwise huisgen cycloaddition process: Copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective ‘ligation’ of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2596–2599 (2002).

Agard, N. J., Prescher, J. A. & Bertozzi, C. R. A Strain-Promoted [3 + 2] azide−alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 15046–15047 (2004).

Tornøe, C. W., Christensen, C. & Meldal, M. Peptidotriazoles on solid phase: [1,2,3]-Triazoles by regiospecific copper(i)-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of terminal alkynes to azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 67, 3057–3064 (2002).

Hoyle, C. E. & Bowman, C. N. Thiol–Ene click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 1540–1573 (2010).

Choi, H., Kim, M., Jang, J. & Hong, S. Visible-Light-Induced cysteine-specific bioconjugation: Biocompatible thiol–ene click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 22514–22522 (2020).

Ahangarpour, M., Kavianinia, I., Hume, P. A., Harris, P. W. R. & Brimble, M. A. N-Vinyl Acrylamides: Versatile Heterobifunctional Electrophiles for Thiol–Thiol Bioconjugations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13652–13662 (2022).

Shiu, H. et al. Electron-Deficient Alkynes as Cleavable Reagents for the Modification of Cysteine-Containing Peptides in Aqueous Medium. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 3839–3850 (2009).

Kasper, M. et al. Cysteine-Selective phosphonamidate electrophiles for modular protein bioconjugations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11625–11630 (2019).

Lowe, A. B., Hoyle, C. E. & Bowman, C. N. Thiol-yne click chemistry: A powerful and versatile methodology for materials synthesis. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 4745 (2010).

Spokoyny, A. M. et al. A perfluoroaryl-cysteine SNAr chemistry approach to unprotected peptide stapling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5946–5949 (2013).

Zhang, D., Devarie-Baez, N. O., Li, Q., Lancaster, J. R. Jr. & Xian, M. Methylsulfonyl benzothiazole (MSBT): A selective protein thiol blocking reagent. Org. Lett. 14, 3396–3399 (2012).

Luo, Q., Tao, Y., Sheng, W., Lu, J. & Wang, H. Dinitroimidazoles as bifunctional bioconjugation reagents for protein functionalization and peptide macrocyclization. Nat. Comm. 10, 142 (2019).

Chen, F. & Gao, J. Fast cysteine bioconjugation chemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202201843 (2022).

Hartmann, P. et al. Chemoselective umpolung of thiols to episulfoniums for cysteine bioconjugation. Nat. Chem. 16, 380–388 (2023).

Ochtrop, P. & Hackenberger, C. P. R. Recent advances of thiol-selective bioconjugation reactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 58, 28–36 (2020).

You, J., Zhang, J., Wang, J. & Jin, M. Cysteine-based coupling: challenges and solutions. Bioconjug. Chem. 32, 1525–1534 (2021).

Lyon, R. P. et al. Self-hydrolyzing maleimides improve the stability and pharmacological properties of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Biotech. 32, 1059–1062 (2014).

Ahangarpour, M., Kavianinia, I. & Brimble, M. A. Thia-Michael addition: the route to promising opportunities for fast and cysteine-specific modification. Organic Biomol. Chem. 21, 3057–3072 (2023).

Christie, R. J. Stabilization of cysteine-linked antibody drug conjugates with N-aryl maleimides. J. Control. Release 12, 660–670 (2015).

Richardson, M. B. et al. Pyrocinchonimides conjugate to amine groups on proteins via imide transfer. Bioconjug. Chem. 31, 1449–1462 (2020).

Kalia, D., Malekar, P. V. & Parthasarathy, M. Exocyclic olefinic maleimides: synthesis and application for stable and thiol-selective bioconjugation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 128, 1454–1457 (2015).

Tobaldi, E., Dovgan, I., Mosser, M., Becht, J.-M. & Wagner, A. Structural investigation of cyclo-dioxo maleimide cross-linkers for acid and serum stability. Org. Biomolecular Chem. 15, 9305–9310 (2017).

Smithies, O. Disulfide-bond cleavage and formation in proteins. Science 150, 1595–1598 (1965).

Pillow, T. H. et al. Decoupling stability and release in disulfide bonds with antibody-small molecule conjugates. Chem. Sci. 8, 366–370 (2017).

Schulz, A., Adermann, K., Eulitz, M., Feller, S. M. & Kardinal, C. Preparation of disulfide-bonded polypeptide heterodimers by titration of thio-activated peptides with thiol-containing peptides. Tetrahedron 56, 3889–3891 (2000).

Dasari, M. et al. H-Gemcitabine: a new gemcitabine prodrug for treating cancer. Bioconjug. Chem. 24, 4–8 (2012).

Kim, T. et al. A biotin-guided fluorescent-peptide drug delivery system for cancer treatment. Chem. Comm. 50, 7690 (2014).

Smith, M. E. B. et al. Protein modification, bioconjugation, and disulfide bridging using bromomaleimides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1960–1965 (2010).

Wall, A. et al. One-pot thiol–amine bioconjugation to maleimides: simultaneous stabilisation and dual functionalisation. Chem. Sci. 11, 11455–11460 (2020).

Takeuchi, H., Shimshoni, E., Gandhesiri, S., Loas, A. & Pentelute, B. L. Equimolar cross-coupling using reactive coiled coils for covalent protein assemblies. Bioconjug. Chem. 35, 1468–1473 (2024).

Baumann, A. L. et al. Chemically induced vinylphosphonothiolate electrophiles for thiol–thiol bioconjugations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9544–9552 (2020).

Nisavic, M. et al. oxSTEF reagents are tunable and versatile electrophiles for selective disulfide-rebridging of native proteins. Bioconjug. Chem. 34, 994–1003 (2023).

Maes, D., Nicque, M., Iftikhar, M. & Winne, J. M. Phenylpropynones as selective disulfide rebridging bioconjugation reagents. Org. Lett. 26, 895–899 (2024).

Teng, S. et al. Thiol-specific silicon-containing conjugating reagent: β-Silyl Alkynyl Carbonyl Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311906 (2023).

Miller, S. I. & Dickstein, J. I. Nucleophilic substitution at acetylenic carbon. The last holdout. Acc. Chem. Res. 9, 358–363 (1976). For classical relevant examples of a direct substitution pathway on bromo-alkynes, see.

Denijs, E. et al. Thermally triggered triazolinedione–tyrosine bioconjugation with improved chemo- and site-selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12672–12680 (2024).

Decoene, K. W. et al. Triazolinedione protein modification: from an overlooked off-target effect to a tryptophan-based bioconjugation strategy. Chem. Sci. 13, 5390–5397 (2022).

De Bruycker, K. et al. Triazolinediones as highly enabling synthetic tools. Chem. Rev. 116, 3919–3974 (2016).

Bausch, M., Selmarten, D., Gostowski, R. & Dobrowolski, P. Potentiometric and spectroscopic investigations of the aqueous phase acid–base chemistry of urazoles and substituted urazoles. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 4, 67–69 (1991).

Desmet, J. et al. Structural basis of IL-23 antagonism by an alphabody protein scaffold. Nat. Comm. 5, 5237 (2014).

De Geyter, E. et al. 5-hydroxy-pyrrolone based building blocks as maleimide alternatives for protein bioconjugation and single-site multi-functionalization. Chem. Sci. 12, 5246–5252 (2021).

Schmitz, K. R., Bagchi, A., Roovers, R. C., en Henegouwen, P. M. V. B. & Ferguson, K. M. Structural evaluation of EGFR inhibition mechanisms for nanobodies/VHH domains. Structure 21, 1214–1224 (2013).

Bernardim, B. et al. Stoichiometric and irreversible cysteine-selective protein modification using carbonylacrylic reagents. Nat. Comm. 7, 13128 (2016).

Christie, R. J. et al. Stabilization of cysteine-linked antibody drug conjugates with N-aryl maleimides. J. Control. Release 220, 660–670 (2015).

Wu, L. H., Zhou, S., Luo, Q. F., Tian, J. S. & Loh, T. P. Dichloroacetophenone derivatives: a class of bioconjugation reagents for disulfide bridging. Org. Lett. 22, 8193–8197 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. 2 H-azirines as potential bifunctional chemical linkers of cysteine residues in bioconjugate technology. Org. Lett. 22, 2038–2043 (2020).

Kang, M. S., Khoo, J. Y. X., Jia, Z. & Loh, T. P. Development of catalyst-free carbon-sulfur bond formation reactions under aqueous media and their applications. Green. Synth. Catal. 3, 309–316 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Complix N. V. for providing us with the alphabody protein. J.M.W. thanks BOF-UGent for GOA funding (01G00721). We would like to thank Ir. Jan Goeman of Ghent University for the LCMS measurements. We also thank the funders of the NMR facilities at Ghent university: FWO (I006920N, 01XP2017) and BOF (BOF/COR/2023/006). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No 956070 [J.H.M. and A.M.]. M.N. thanks the FWO for a scholarship (1SH7F24N). K.B. thanks the FWO for a scholarship (1SA4422N). J.G. thanks BOF-UGent for funding (GOA008-24BOF and BOF/24j/2023/145).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.N. and J.M.W. conceived the work and together acquired its main source of funding. M.N. performed the most small molecule and peptide modification experiments. D.M.; K.B and M.I. assisted in some of the modification experiments and preparation of substrates, as well as in preliminary investigations that supported this work. J.M.W. supervised the whole project. J.M.W. and M.N. wrote the original draft of the manuscript and also drafted its main figures. M.N. and J.H.M. jointly performed all protein modification experiments as well as the small molecule kinetic studies, which were jointly supervised and conceived by J.M.W and A.M. The cysteine-functionalized nanobody was expressed and isolated by O.Z. and J.G. Moreover, J.G. helped conceive the protein-protein conjugation experiments. All the authors participated in the data analysis and discussion and in reviewing and editing the manuscript and its supplementary information.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Thomas Poulsen, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicque, M., Meffert, J.H., Maes, D. et al. Thiol-thiol cross-clicking using bromo-ynone reagents. Nat Commun 16, 6386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61682-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61682-5