Abstract

In divergent carbonylative transformations using identical starting substrates, ligand-assisted transition metal catalysis has dominated selectively controllable transformations. However, achieving precise control of CO insertion in transition-metal-free systems remains a challenge. Herein, we disclose a divergent radical tandem carbonylation of multi-substituted homoallylic alcohols for the synthesis of γ-lactones and 1,4-diones. Utilizing quinuclidine as an electron donor steers the reaction towards lactonization, whereas the employment of DIPEA results in the migration of the aryl group to the carbonyl carbon. The key to tune the chemoselectivity lies in the ability of tertiary amines with different structures to precisely control the form of the active carbonyl intermediate, thereby inducing two distinct reaction pathways. Mechanistic studies reveal that the tertiary amine not only serves as an electron-transfer mediator but also functions as a tuner to govern chemoselectivity. The insights obtained from this study offer valuable enlightenment for selectively obtaining two types of carbonyl compounds, both advancing the performance exploring of electron donors in EDA complexes, fostering selective carbonylation development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

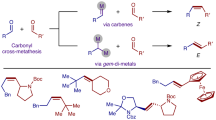

Embedding CO into small organic molecules provides an effective pathway for the construction of diverse molecular skeletons containing carbonyl functional groups1,2,3,4,5,6. Obviously, selectivity-related challenges also gradually emerged with the development of carbonylation reactions. In particular, whether regioselectivity or chemoselectivity can be effectively controlled has become a common focus in the field of selective carbonylative synthesis7,8. In the past few years, selective carbonylation9,10,11,12 (linear and branched) of unsaturated bonds represented by hydroformylation have achieved remarkable results. The practicality of these strategies can be attributed to the selective activation of the substrate by the ligand-chelated metal species13,14,15. In these cases, whether the selectivity can be effectively controlled is often determined at the beginning stage of the reaction16,17 (Fig. 1a). For ligand-assisted metal-catalyzed systems, to enable the selective activation of diverse sites, its high demand on the specific steric and/or electronic properties of the ligands increasing the challenge of the methodology. Therefore, there is an urgent need at present to develop innovative strategies for selective carbonylation in transition-metal-free systems. Whether there exists a key factor that can determine the direction of the carbonylation reaction by controlling the carbonyl intermediate in the late stage has triggered our meditation. The concept we envision is that different acyl intermediates induce the reaction in their respective channels. The challenge is how to obtain acyl intermediates with different reactivity in a controllable manner (Fig. 1b).

a Tunable divergent carbonylation via site-selective activation strategy. b Our concept: chemoselective carbonylation enabled by controlling acyl intermediates. c Traditional EDA complex model in which amine species play a single role. d Our design of dual functionality of amine species in EDA chemistry. e Tertiary amine regulated divergent carbonylation for the synthesis of 1,4-diones and γ-lactones.

Over the past few years, organic transformations promoted by small organic molecules have provided complementary strategies for traditional transition metal-catalyzed coupling reactions, especially the exploration of electron donor-acceptor (EDA) complexes reaction system18, which has successfully attracted much attention of organic chemistry researchers19,20,21,22. Triarylamines are electron-rich due to the presence of their lone pair electrons and are therefore often used in EDA complexes as electron donors to induce the generation of radical species through single-electron transfer. For example, in 2022, Procter and co-workers developed an EDA complex for the alkylation and cyanation of arenes23. In this system, newly designed amines act as an electron donor, promoting triarylsulfonium salts to produce aromatic radicals. Recently, Li’s group also reported a novel EDA complex employing tris(4-methoxyphenyl) amine as a catalytic electron donor for the sulfonylation of alkenes24. These representative studies demonstrated that amines have great development potential as electron donors in EDA complex chemistry25,26 (Fig. 1c). In traditional EDA chemistry, for tertiary amines, whether they act as a stoichiometric electron donor or a catalytic electron donor, during the reaction process, apart from undertaking the responsibility of electron transfer, they do not play an additional role, such as controlling the chemoselectivity of the reaction27. The unique properties of amine cation radicals generated by tertiary amines with different structures have been ignored. Amine cation radicals with different electronic properties may become the key elements for controlling reaction intermediates. Especially in selective carbonylation transformations, if amines can not only transfer electrons but also play a second role in controlling the form of the acyl intermediate, it will provide a new platform for divergent carbonylation. (Fig. 1d). Although amine cation radicals show great potential in controlling the chemoselectivity of reactions, yet there remains less explored on tertiary amines that take on two functions in one process and achieve chemoselective transformations.

A variety of reactive carbonyl intermediates are the basis for achieving chemoselectivity in carbonylation reactions, but how to precisely control the production of a particular intermediate is a challenge. We try to overcome this obstacle, so we envision a model in which tertiary amines as electron donors. Carbon radical is produced by the EDA complex, then captures CO to obtain an acyl radical species. Meanwhile, the amine loses one electron and is transformed into an amine radical cation, and the radical cations with different structures or electronic properties will determine the form of the acyl intermediate. Specifically, when the steric hindrance is small, the acyl radical species could be oxidized to acyl cations28, but when the steric hindrance is large, the acyl radical could be exposed. While two active groups, a nucleophilic hydroxyl group and an aryl group that can be added by radical, competing in one molecule, the acyl intermediate will selectively react with one of them. Electrophilic acyl cations tend to undergo lactonization with the hydroxyl group, while nucleophilic acyl radicals tend to allow the aryl group to complete radical long-distance migration29 (Fig. 1e).

Aryl-substituted homoallyl alcohol compounds, which can be obtained from various ketones through simple transformation, come into our view. The structural characteristics of both hydroxyl and aromatic groups make it the best choice for us to test the regulation of chemoselective carbonylation by controlling intermediates. Note that, although unsaturated alcohols have been widely studied in intramolecular cyclization and remote functional group migration reactions30,31,32,33, homoallylic alcohols are not candidates for aromatic migration due to their short carbon chain. CO insertion enables intramolecular cyclization and remote group migration because of carbon chain can be extended. We expect to rely on the control of the acyl intermediate species by the electron donor to synthesize 1,4-diketones and γ-lactones from the same substrate, respectively. 1,4-diketones34,35,36,37,38 and γ-lactones39,40,41 are two important carbonyl-containing compounds that are isomers of each other, and their skeleton structures are widely present in natural products and drug molecules. This platform, which only relies on switchable tertiary amines as electron donors, offers valuable enlightenment for selectively obtaining two compounds containing different types of carbonyl functional groups, both advancing the performance exploring of electron donors in EDA complexes and fostering selective carbonylation development.

Results

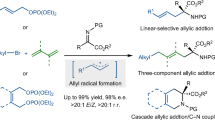

To test the validity of chemoselective carbonylation utilizing tertiary amine, we selected amines and Togni’s reagent (II)42 as EDA complex models to investigate the intramolecular cyclization and distant aromatic migration of homoallylic alcohol 1a in the presence of CO (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Tables 1–4). We started our study by stirring a mixture of 1a, Togni’s reagent (II) (2 equiv.), and TEA (triethylamine) (2 equiv.) in MeCN under CO atmosphere at 30 °C for 36 h. As expected, the intramolecular cyclization product 2a and the phenyl migration product 3a were obtained simultaneously in 42% and 33% yields, respectively. The most immediate challenge facing us was controlling chemoselectivity (lactonization vs migration). We tested a series of organic amines with different structures (D1–D5), which are considered to be potentially effective to solve this problem. Surprisingly, we found that the type of amine essential to regulate the chemoselectivity in this transformation (Fig. 2b). The specific situation is 2a was delivered in 73% yield with exquisite selectivity when D1 (quinuclidine, 2 equiv.) was employed as the electron donor in this system (Fig. 2c, entry 3). When the electron donor was replaced with D4 (DIPEA, 2 equiv.), 3a was successfully obtained with a yield of 63% (Fig. 2c, entry 4). According to the ratio of 2a and 3a, it can be confirmed that the amine with a small steric hindrance can promote the lactonization process to obtain 2a, while the amine with a large steric hindrance is conducive to the migration of the phenyl group to obtain 3a. It has been preliminarily proved that the change of steric hindrance helps to tune the selectivity.

a Reaction conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.4 mmol), donor (50 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv.) in solvent (2 mL) at 30 °C for 36 h under CO (40 bar). b Comparison of the effects of typical amines on selectivity between lactonization and migration. Reaction conditions: 1a (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.4 mmol), donor (0.4 mmol), in solvent (2 mL) at 30 °C for 36 h under CO (40 bar), yields were determined by GC-FID. c Effect of others on tunable chemoselective carbonylation, yields were determined by GC-FID analysis using n-hexadecane as internal standard. Isolated yields are given in brackets.

In addition, we also attempted to add more amines, both commercially available and newly designed (Please see Supplementary Table 1 for more details). We found an interesting phenomenon that greater steric hindrance is not always more favorable for the formation of 3a. For example, the results of the experiment in the presence of D5 showed that when the steric hindrance is too large, both lactonization and aromatic rearrangement will be inhibited, and the starting materials will be completely recovered. We speculated that compared with DIPEA after the ethyl group is replaced by the benzyl group, the lone pairs of electrons on the nitrogen atom are subjected to a stronger shielding effect, the formation of the EDA complex is hindered, which retards the single-electron transfer and thus no radicals are generated. It is worth noting that the amount of amine donor cannot exceed that of the electron acceptor (Togni’s reagent (II)); otherwise, the reaction will be completely inhibited, regardless of whether D1 or D4 was used.

After screening the dosage of amines, the temperature test of lactonization conversion43,44,45,46 was also carried out, it was found that when the temperature was reduced to 20 °C, the reaction system was completely inactivated (Fig. 2c, entry 5), and when the temperature was increased to 50 °C, the selectivity control effect was slightly reduced. Notably, the two reaction pathways have different sensitivities to temperature. When D4 was used for rearrangement transformation, the yield of 3a did not fluctuate significantly in the range of 20 °C to 50 °C.

Reducing the CO pressure47 is not conducive to carbonylation conversion (whether lactonization or migration), which is mainly due to the difficulty in capturing alkyl radicals by CO (Fig. 2c, entries 7 and 8)48,49,50. Finally, the loading of the amine donor could be appropriately reduced by adding an additional inorganic base, and the reaction efficiency can be marginally improved. In particular, only amines play a decisive role in the selectivity of carbonylation conversion in the whole process, thus revealing that the EDA system we designed is indeed a suitable system, which can achieve unusual chemoselective carbonylation reactions under transition metal-free conditions by relying on the characteristics of amines.

As the lactonization and migration conditions have been optimized, we assessed the ability of this protocol to discriminate between lactonization and migration products by preparing a series of substrates to explore the effects of aromatic ring substitution (Fig. 3). First, homoallylic alcohols substituted with two symmetrical aromatic rings are well tolerated, especially when the para-position of the aromatic ring contains the same substituent (such as the Me, OMe, halogen, OTs.), whether it is an electron-withdrawing group or an electron-donating group. In condition A, the lactonization products 2a–2g were delivered in 65–77% yields. In condition B, the migration products 3a–3g were delivered in 43–68% yields. When the substituents on the substrate are replaced by two asymmetric aromatic rings, containing two different substituents at the para-position, 2h–2j were obtained in 53–65% yields using the lactonization procedure. However, in the migration section, we found that there is a priority between the two asymmetric aromatic rings. For example, the ratio of electron-poor trifluoromethyl-substituted benzene ring to electron-rich tert-butyl substituted benzene ring is 9:1 (3h). However, the ratio of chlorine-substituted benzene rings to unsubstituted benzene rings is 4.5:1 (3j). This indicates that the more electron-deficient aromatic ring will migrate preferentially, and further extreme electronic effects of the two benzene rings are conducive to better selectivity. These results are consistent with the fact that acyl radicals are nucleophilic51. It’s also important to mention that the diastereomers could not be separated to determine the major diastereomers for the compounds that have diastereomers due to their very similar polarity52.

aCondition A: 1 (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.4 mmol), quinuclidine (50 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv.) in CH3CN (2 mL) at 30 °C for 36 h under CO (40 bar). Condition B: 1 (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.4 mmol), DIPEA (50 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv.) in CH3CN (2 mL) at 30 °C for 36 h under CO (40 bar). bThe ratio of diastereoisomers (competition migration between two different aryl groups) was determined by 1H NMR. The dr. ratio was determined by 1H NMR. All yields are isolated yields.

Aside from double aromatic ring substitution, single aromatic ring substituted homoallylic alcohols were also used to perform exploration (1k and 1l). 1k was tested under condition A, lactone product 2k was obtained in 51% and gave a 16% yield of the migration product 3k (3.2:1 lactonization/migration). For cyclohexyl-substituted 1l, the ratio of lactone products 2l to migration products 3l decreased to 1.6:1, but 2l was still the major product. Obviously, in condition A, alkyl substitution reduced the selectivity of lactonization. With condition B, 3k and 3l can be obtained in moderate yield with good migration selectivity (52% and 41%). It is noteworthy that we isolated the acyl radical homolytic aromatic substitution product 3l’ in 23% yield. We speculate that the alkyl substitution hinders the ipso-addition of the acyl radical to the aromatic ring, so the acyl group was directly introduced into the benzene ring to complete the cycloketonization.

Interestingly, lactonization is more sensitive to the steric hindrance of the substrate than migration. When a methyl group was introduced at the ortho-position of one of the benzene rings of the model substrate 1a, the lactonization was almost completely inhibited, only trace amounts of the target product 2m were detected, and the raw material 1m was recovered. Even increasing the reaction temperature could not overcome this obstacle. Although migration is also affected, 3m can still be obtained at a yield of 37%. The benzene ring with less steric hindrance has an advantage over the competition for migration. Further increasing the steric hindrance of the substrate, such as 2n, no matter which conditions are used, it cannot be made reactive, lactonization and migration are both completely inhibited. When we tried the cyclic substrates 1o, surprisingly, the spironolactone product 2o could be obtained under condition A, but ring expansion by migration seemed extremely difficult.

Inspired by the spironolactone 2o obtained from 1o, we next turned our attention to the spirolactonization promoted by quinuclidine. γ-Lactone fragment is found in myriad pharmaceuticals and natural biological molecules. Especially spironolactone, has a special efficacy in the treatment of certain diseases, such as spironolactone can be used to treat heart failure53. Although some methods have been developed to synthesize spironolactones52,54, existing strategies are difficult to avoid preparation for complex substrates or dependence on transition metal catalysis. The inside-out cyclization of α-oxygenated radicals is based on oxalyl chloride as the carbonyl source. However, there are less studies on utilizing cheap CO to construct spironolactone in transition-metal-free conditions (Fig. 4).

aReaction conditions: 4 (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.4 mmol), quinuclidine (50 mol%), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv.) in CH3CN (2 mL) at 30 °C for 36 h under CO (40 bar). b4s (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.8 mmol), quinuclidine (0.4 mmol), in solvent (2 mL) at 30 °C for 36 h under CO (40 bar). c4m (0.2 mmol), CCl4 (2 mmol), quinuclidine (0.4 mmol), CH3CN (2.0 mL, 0.1 M), CO (40 bar), 390 nm LED (45 W), rt. and 24 h. d4m (0.2 mmol), Rf-I (0.4 mmol), quinuclidine (0.4 mmol), Et2O (2.0 mL, 0.1 M), CO (40 bar), white LED (30 W), rt. and 24 h. The dr. ratio was determined by 1H NMR. dr. diastereomeric ratio. All yields are isolated yields.

Relying on a quinuclidine-promoted lactonization strategy, we synthesized a series of cycloalkyl-substituted homoallyl alcohols 4 from cyclic ketones to produce a wide variety of spirolactonization products 5. Trifluoromethyl-substituted γ-lactones with 4, 5, 6, 7, and even 12-membered carbon rings can be obtained in moderate to good yields (5a–5e, respectively). Oxetane-containing spirocyclic lactones 5f that are difficult to construct by other methods can be synthesized using this strategy. 2-Indanone derivatives can also be used to construct spironolactone 5g, containing aromatic rings. Six-membered heterocyclic rings containing oxygen, sulfur, or nitrogen also show good compatibility, spiro-γ-lactones (5h–5j) obtained in excellent yields, requiring only the corresponding alcohols derived from cyclic ketones. When the para-position of the 6-membered carbon ring contained an amino or fluorine functional group, 5k and 5l were synthesized in 91% and 83% yields, respectively. Polycyclic and endocyclic structures are very attractive, so we hope to use this approach to introduce structures with important synthetic values, such as adamantane and tropane, into spironolactones. Fortunately, we successfully obtained products 5m–5r. When the substrate contains two cyclization sites, molecule 5s containing two lactone fragments can be constructed in one step. In addition, some complex substrates containing bioactive molecular fragments could also be employed, allowing for the formation of spironolactones 5t–5x in good yields. Notably, 5aa has two pyridine groups derived from di-2-pyridyl ketone, which is a potential ligand for selective C-H activation55. Finally, by simply adjusting the conditions, we can replace the radical precursor and expand the types of radicals to trichloromethyl and various perfluoroalkyl (5cc–5gg).

To further demonstrate the practicality of using DIPEA as an electron donor to initiate remote group migration, after completing the above-mentioned studies, we attempted to replace the migrating group with a heterocycle (Fig. 5). Considering that heteroaryl groups are generally electron-deficient, the addition of the nucleophilic acyl radical to the heterocycle for dearomatization is more advantageous56. We anticipate that heterocycles will undergo remote migration more rapidly than benzene rings. Under condition B, substrate 6a containing benzothiazole and phenyl groups was employed for the preliminary test. The results showed that benzothiazole had an absolute advantage in undergoing remote migration, and the target product 7a was successfully obtained, which was consistent with our expectations. To facilitate the full conversion of raw materials, appropriate modifications were made to migration condition B. The solvent was changed from MeCN to EtOAc, and the reaction temperature was raised to 35 °C. Subsequently, we investigated the influence of modifying the phenyl group on the homoallylic alcohol substrate. The experimental results show that benzothiazole is the only object to be migrated, not the benzene ring (7a–7n). In addition, there are neither lactone products nor ketone products generated from the homolytic aromatic substitution of acyl radicals. Other heterocycles, including benzoxazole, thiazole, oxazole, and pyridine, have been demonstrated to undergo the same type of selective migration (7o–7v). The transfer of the heterocyclic ring to the acyl carbon always has an absolute advantage. This provides evidence that acyl radicals are the most efficient reactive acyl intermediates in the presence of DIPEA. As the migrated groups expand from aromatic to heteroaromatic groups, the applicability of this emerging DIPEA-promoted carbonylation migration platform is further confirmed.

aReaction conditions: 6 (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.4 mmol), DIPEA (1.0 equiv.), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv.) in EtOAc (2 mL) at 35 °C for 24 h under CO (40 bar). b6v (0.2 mmol), Togni reagent (II) (0.6 mmol), DIPEA (0.2 mmol), K2CO3 (1.5 equiv.) in EtOAc (2 mL) at 35 °C for 48 h under CO (40 bar). All yields are isolated yields.

To probe the possible radical mechanism, we added radical inhibitor TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl) to standard conditions A and B, respectively. As predicted, both the lactonization and migration processes were completely inhibited; no 2a and 3a were detected, and the raw material 1a was completely recovered (Fig. 6a). We also designed and synthesized but-3-ene-1,1-diyldibenzene 8 as a radical receptor and attempted to capture the acyl intermediate produced by carbonylation. Indeed, product 9 provides evidence for the existence of an acyl radical intermediate in condition B (Fig. 6b)57. To explore our mechanistic hypothesis and quantitatively assess the role of the donor in promoting lactonization or migration, we examined the yield distributions of 2a and 3a over a range of D1/D4 donor mixtures. An initial experiment using 1:1 mixture of D1/D4 as donor demonstrated that can give an approximate yield of 2a and 3a (1.1:1 lactonization/migration). Obviously, mixtures of D1/D4 demonstrated lower chemoselectivity compared to D1 or D4 alone when employed as donors. Lowering the ratio of D1/D4 to 1:3 increased production of 3a (43%) and decreased the yield 2a (28%), enhancing the ratio of D1/D4 to 3:1 increased production of 2a (58%) and decreased the yield 3a (26%). The ratio of lactonization products to migration products was positively correlated with the dosage of D1 and D4, which showed that D1 was beneficial to the lactonization process, while D4 was beneficial to the migration process. We can infer that lactonization and migration are two independent processes that do not interfere with each other, and the selectivity is mainly regulated by the amine as an electron donor (Fig. 6c).

To further illustrate how different electron donors regulate the reaction process, we performed cyclic voltammetry tests on four amines D1–D4. D1 (quinuclidine) showed an oxidation potential peak at Ep = 1.33 V vs. Ag/AgCl (blue line; Fig. 2d), which is higher than the oxidation potential of D4 (DIPEA, Ep = 1.12 V vs. Ag/AgCl (orange line; Fig. 2d)). The higher oxidation potential of D1 means that its cation radical has a stronger oxidizing ability. The lactonization process may go through an acyl carbon cation intermediate, which is obtained by the oxidation of the acyl radical by the amine cation radical. Although all amines D1–D4 have redox potentials of 1.12–1.39 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), it seems that they are capable of oxidizing acyl radicals to acyl cations58,59,60,61,62,63. We speculate that, compared with other amines, the relatively constrained cyclic geometric structure of the quinuclidine radical cation allows it to easily immediately undergo single-electron transfer. Its unique structure determines that quinuclidine is the only electron donor that exhibits excellent intramolecular esterification selectivity.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to gain deeper insights into the reaction mechanism and the origins of selectivity (Fig. 6e, and see Supplementary Fig. 3 for more details). Based on the analysis of the aforementioned results, DFT calculations, and related studies, the plausible reaction mechanisms are summarized in Fig. 6f. CF3 radical and tertiary amine radical cation were generated from an EDA complex of Togni’s regent II with tertiary amine, and then CF3 radical added to olefin (1a) to produce a secondary carbon radical (Fig. 2f). In the CO atmosphere, carbon radicals capture CO to produce acyl radical intermediate III (Fig. 2f). The radical attack on the aryl ring occurs via transition state TS1, with an energy barrier of 7.3 kcal/mol. This step leads to the formation of the dearomatized radical intermediate V, from which migration of the aryl group affords product 3a. Alternatively, the acyl radical intermediate III can undergo an outer-sphere single-electron transfer (OSET) with the tertiary amine radical cation to generate the neutral tertiary amine and the acyl cation IV. The latter subsequently undergoes facile intramolecular lactonization to yield the cyclized product 2a. According to Marcus theory, the OSET involving quinuclidine radical cation I requires an energy barrier of 5.1 kcal/mol, which is 2.2 kcal/mol lower than that of the radical attack transition state TS1, consistent with experimental observations that the cyclized product 2a should be observed with D1. However, the energy barrier for the OSET with DIPEA radical cation II was calculated to be 8.3 kcal/mol, which is 1.0 kcal/mol higher than that of TS1. Therefore, the computations clearly reproduce the observed selectivity switch upon changing the tertiary amine.

Marcus theory indicates that the energy barrier of the OSET is sensitive to the energy difference between the tertiary amine radical cation and the neutral tertiary amine. Specifically, the OSET leading to the formation of quinuclidine D1 is exergonic by −19.4 kcal/mol, whereas it is only −9.5 kcal/mol for the formation of DIPEA D4, making the OSET with I lower in energy than with II. The optimized geometries reveal that the DIPEA radical cation II adopts a nearly ideal planar geometry for the radical species (179.87°), whereas quinuclidine radical cation I adopts a nearly tetrahedral geometry due to its constrained cyclic structure (135.87°). These geometric features render quinuclidine radical cation I relatively less stable compared to II. Furthermore, quinuclidine D1 adopts a geometry closer to tetrahedral than that of DIPEA D4, likely due to the steric effects of the bulkier substituents in D4, making D1 relatively more stable than D4. The combination of the relatively unstable I and the more stable D1 results in the thermodynamics of the OSET with I being 5.1 kcal/mol more favorable than with II, thereby enabling the experimentally observed selectivity switch. Experimentally, a mixture of products 2a and 3a was observed when tertiary amines D2 and D3 were used. The energies of the OSET processes involving these tertiary amine radical cations were calculated to be 7.5 and 7.2 kcal/mol, being very close to the energy of TS1, which aligns well with experimental observations (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for details). This can be attributed to the fact that compared to D4, the substituents in D2 and D3 are relatively smaller, rendering D2 and D3 more stable than D4, which leads to a relatively easier OSET process.

Discussion

The selective synthesis of γ-lactones and 1,4-diones starting from the same materials confirms the feasibility of the strategy for regulating switchable carbonylation by electron donors. Further extension of the synthetic scope to γ-spironolactones and heteroaryl-substituted diketones demonstrates the excellent compatibility of this system. We have pioneered the discovery of another important function of tertiary amine in the EDA complex besides being an electron donor, which is to act as a tuner to control the chemoselectivity of the carbonylative reaction. Mechanistic studies show that amine electron donors with different structural properties are the key to controlling the acyl intermediates in the form of electrophilic acyl cations or nucleophilic acyl radicals. Controllable carbonylation enables the diversification of the transformation of homoallylic alcohols, showing the unique appeal of CO activation and utilization. Considering the potential of EDA systems in organic transformations, the protocol we developed to use dual functions of electron donors will serve as a launchpad for exploring new EDA complex platforms to achieve chemoselective control.

Methods

General procedure for the carbonylation-triggered lactonization or migration. A 4 mL screw-cap vial was charged with homoallylic alcohols (0.2 mmol), Togni’s reagent (II) (0.4–0.6 mmol) or other radical precursors (0.4–0.6 mmol), electron donor amine (50 mol%), K2CO3 (0.1–0.3 mmol), and an oven-dried stirring bar. The vial was closed with a Teflon septum and cap and connected to the atmosphere via a needle. Then solvent (2 mL) was added with a syringe under N2 atmosphere. The closed autoclave was flushed two times with nitrogen (~5 bar), and a pressure of 40 bar CO was charged. The autoclave was then placed on a magnetic stirrer. The reaction mixture was stirred at 30–35 °C for 24–36 h. After the reaction, the mixture was concentrated under vacuum. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (PE/EA = 50/1–2/1) on silica gel to afford the corresponding products. Note: Because of the high toxicity of carbon monoxide, all the reactions should be performed in an autoclave. The laboratory should be well-equipped with a CO detector and alarm system.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information or from the authors upon request.

References

Peng, J.-B., Geng, H.-Q. & Wu, X.-F. The chemistry of CO: carbonylation. Chem 5, 526–552 (2019).

Sumino, S., Fusano, A., Fukuyama, T. & Ryu, I. Carbonylation reactions of alkyl iodides through the interplay of carbon radicals and Pd catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1563–1574 (2014).

Torres, G. M., Liu, Y. & Arndtsen, B. A. A dual light-driven palladium catalyst: breaking the barriers in carbonylation reactions. Science 368, 318–323 (2020).

Tung, P. & Mankad, N. P. Light-mediated synthesis of aliphatic anhydrides by Cu-catalyzed carbonylation of alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9423–9427 (2023).

Day, C. S., Ton, S. J., Kaussler, C., Vronning Hoffmann, D. & Skrydstrup, T. Low pressure carbonylation of benzyl carbonates and carbamates for applications in 13C isotope labeling and catalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308238 (2023).

Ding, Y., Wu, J. & Huang, H. Carbonylative formal cycloaddition between alkylarenes and aldimines enabled by palladium-catalyzed double C-H bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4982–4988 (2023).

Xu, T. & Alper, H. Pd-catalyzed chemoselective carbonylation of aminophenols with iodoarenes: alkoxycarbonylation vs aminocarbonylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16970–16973 (2014).

Peng, J.-B. & Wu, X.-F. Ligand- and solvent-controlled regio- and chemodivergent carbonylative reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1152–1160 (2018).

Fang, X., Jackstell, R. & Beller, M. Selective palladium-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of olefins with aromatic amines and nitroarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 14089–14093 (2013).

Fang, X., Li, H., Jackstell, R. & Beller, M. Selective palladium-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of 1,3-dienes: atom-efficient synthesis of β, γ-unsaturated amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16039–16043 (2014).

Xu, T., Sha, F. & Alper, H. Highly ligand-controlled regioselective Pd-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of styrenes with aminophenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6629–6635 (2016).

Bao, Z.-P., Zhang, Y., Wang, L.-C. & Wu, X.-F. Difluoroalkylative carbonylation of alkenes to access carbonyl difluoro-containing heterocycles: convenient synthesis of gemigliptin. Sci. China Chem. 66, 139–146 (2023).

Shen, C., Wei, Z., Jiao, H. & Wu, X.-F. Ligand- and solvent- tuned chemoselective carbonylation of bromoaryl triflates. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 13369–13378 (2017).

Wu, F.-P. & Wu, X.-F. Ligand-controlled copper-catalyzed regiodivergent carbonylative synthesis of a-amino ketones and a-boryl amides from imines and alkyl iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 695–700 (2021).

Cao, Z., Wang, Q., Neumann, H. & Beller, M. Regiodivergent carbonylation of alkenes: selective palladium catalyzed synthesis of linear and branched selenoesters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202313714 (2024).

Lu, B. et al. Switchable radical carbonylation by philicity regulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14923–14935 (2022).

Yuan, Y. & Wu, X.-F. Generation and transformation of α-oxy carbene intermediates enabled by copper-catalyzed carbonylation. Green. Carbon 2, 70–80 (2024).

Crisenza, G. E. M., Mazzarella, D. & Melchiorre, P. Synthetic methods driven by the photoactivity of electron Donor-Acceptor complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5461–5476 (2020).

Xue, T. et al. Characterization of A π–π stacking cocrystal of 4-nitrophthalonitrile directed toward application in photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 1455 (2024).

Spinnato, D., Schweitzer-Chaput, B., Goti, G., Oseka, M. & Melchiorre, P. A photochemical organocatalytic strategy for the α-alkylation of ketones by using radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9485–9490 (2020).

Jiang, Y.-X. et al. Visible-light-driven synthesis of N-heteroaromatic carboxylic acids by thiolate-catalysed carboxylation of C(sp²)-H bonds using CO2. Nat. Synth. 3, 394–405 (2024).

Beato, E., Spinnato, D., Zhou, W. & Melchiorre, P. A general organocatalytic system for electron donor-acceptor complex photoactivation and its use in radical processes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12304–12314 (2021).

Dewanji, A. et al. A general arene C-H functionalization strategy via electron donor-acceptor complex photoactivation. Nat. Chem. 15, 43–52 (2023).

Lasso, J. D. et al. A general platform for visible light sulfonylation reactions enabled by catalytic triarylamine EDA complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 2583–2592 (2024).

Dang, X. et al. Photoinduced C(sp3)-H bicyclopentylation enabled by an electron donor-acceptor complex-mediated chemoselective three-component radical relay. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400494 (2024).

Volkov, A. A., Bugaenko, D. I. & Karchava, A. V. Transition metal and photocatalyst free arylation via photoexcitable electron donor acceptor complexes: mediation and catalysis. ChemCatChem 16, https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.202301526 (2024).

Wei, D. et al. Radical 1,4/5-amino shift enables access to fluoroalkyl-containing primary β(γ)-aminoketones under metal-free conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26308–26313 (2021).

Quesnel, J. S., Fabrikant, A. & Arndtsen, B. A. A flexible approach to Pd-catalyzed carbonylations via aroyl dimethylaminopyridinium salts. Chem. Sci. 7, 295–300 (2016).

Wu, X., Ma, Z., Feng, T. & Zhu, C. Radical-mediated rearrangements: past, present, and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 11577–11613 (2021).

Allen, A. R., Noten, E. A. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Aryl transfer strategies mediated by photoinduced electron transfer. Chem. Rev. 122, 2695–2751 (2022).

Li, Z.-L., Li, X.-H., Wang, N., Yang, N.-Y. & Liu, X.-Y. Radical-mediated 1,2-formyl/carbonyl functionalization of alkenes and application to the construction of medium-sized rings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15100–15104 (2016).

Hervieu, C. et al. Asymmetric, visible light-mediated radical sulfinyl-smiles rearrangement to access all-carbon quaternary stereocentres. Nat. Chem. 13, 327–334 (2021).

Chen, K. et al. Functional-group translocation of cyano groups by reversible C-H sampling. Nature 620, 1007–1012 (2023).

DeMartino, M. P., Chen, K. & Baran, P. S. Intermolecular enolate heterocoupling: scope, mechanism, and application. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11546–11560 (2008).

Cheng, Y. et al. Direct 1,2-dicarbonylation of alkenes towards 1,4-diketones via photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26822–26828 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Photoredox-enabled chromium-catalyzed alkene diacylations. ACS Catal. 12, 1879–1885 (2022).

Wang, D. & Ackermann Three-component carboacylation of alkenes via cooperative nickelaphotoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 13, 7256–7263 (2022).

Lemmerer, M., Schupp, M., Kaiser, D. & Maulide, N. Synthetic approaches to 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds. Nat. Synth. 1, 923–935 (2022).

Zhu, R. & Buchwald, S. L. Copper-catalyzed oxytrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 12462–12465 (2012).

Jeffrey, J. L., Terrett, J. A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. O-H hydrogen bonding promotes H-atom transfer from α C-H bonds for C-alkylation of alcohols. Science 349, 1532–1536 (2015).

Zhou, S., Zhang, Z.-J. & Yu, J.-Q. Copper-catalysed dehydrogenation or lactonization of C(sp3) -H bonds. Nature 629, 363–369 (2024).

Cheng, Y. & Yu, S. Hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes and alkynes enabled by an electron-donor-acceptor complex of Togni’s reagent with a tertiary amine. Org. Lett. 18, 2962–2965 (2016).

Petti, A. et al. Economical, green, and safe route towards substituted lactones by anodic generation of oxycarbonyl radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16115–16118 (2019).

Lindner, H. et al. Photo-and cobalt-catalyzed synthesis of heterocycles via cycloisomerization of unactivated olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. 63, e202319515 (2024).

Wackelin, D. J. et al. Enzymatic assembly of diverse lactone structures: an intramolecular C-H functionalization strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 1580–1587 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Repurposing visible-light-excited ene-reductases for diastereo-and enantioselective lactones synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402673 (2024).

Kawamoto, T., Fukuyama, T., Picard, B. & Ryu, I. New directions in radical carbonylation chemistry: combination with electron catalysis, photocatalysis and ring-opening. Chem. Commun. 58, 7608–7617 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Transition-metal-free alkoxycarbonylation of aryl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12542–12545 (2012).

Guo, W. et al. Metal-free, room-temperature, radical alkoxycarbonylation of aryldiazonium salts through visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2265–2269 (2015).

Majek, M. & Wangelin, A. J. Metal-free carbonylations by photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2270–2274 (2015).

Chatgilialoglu, C., Crich, D., Komatsu, M. & Ryu, I. Chemistry of acyl radicals. Chem. Rev. 99, 1991–2070 (1999).

Weires, N. A., Slutskyy, Y. & Overman, L. E. Facile preparation of spirolactones by an alkoxycarbonyl radical cyclization-cross-coupling cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8561–8565 (2019).

Quintavalla, A. Spirolactones: recent advances in natural products, bioactive compounds and synthetic strategies. Curr. Med. Chem. 25, 917–962 (2018).

Cavalli, D. & Waser, J. Organic dye photocatalyzed synthesis of functionalized lactones and lactams via a cyclization-alkynylation cascade. Org. Lett. 26, 4235–4239 (2024).

Jin, Y., Ramadoss, B., Asako, S. & Ilies, L. Noncovalent interaction with a spirobipyridine ligand enables efficient iridium-catalyzed C-H activation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2886 (2024).

Proctor, R. S. J. & Phipps, R. J. Recent advances in Minisci-type reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13666–13699 (2019).

Fu, Y., Liu, L., Yu, H.-Z., Wang, Y.-M. & Guo, Q.-X. Quantum-chemical predictions of absolute standard redox potentials of diverse organic molecules and free radicals in acetonitrile. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 7227–7234 (2005).

Peng, J.-B., Qi, X. & Wu, X.-F. Visible Light Induced carbonylation reactions with organic dyes as the photosensitizers. ChemSusChem 9, 2279–2283 (2016).

Fukuyama, T., Nakashima, N., Okada, T. & Ryu, I. Free-radical-mediated [2 + 2 + 1] cycloaddition of acetylenes, amidines, and CO leading to five-membered α, β-unsaturated lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 1006–1008 (2013).

Kawamoto, T., Sato, A. & Ryu, I. Photoinduced aminocarbonylation of aryl iodides. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 14764–14767 (2015).

Fukuyama, T., Bando, T. & Ryu, I. Electron-transfer-induced intramolecular heck carbonylation reactions leading to benzolactones and benzolactams. Synthesis 50, 3015–3021 (2018).

Picard, B., Fukuyama, T., Bando, T., Hyodo, M. & Ryu, I. Electron-catalyzed aminocarbonylation: synthesis of α, β-unsaturated amides from alkenyl iodides, CO, and amines. Org. Lett. 23, 9505–9509 (2021).

Forni, J. A., Micic, N., Connell, T. U., Weragoda, G. & Polyzos, A. Tandem photoredox catalysis: enabling carbonylative amidation of aryl and alkylhalides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 18646–18654 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the financial support provided by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1507500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22302198 and 22471191), and the Chinese Academy of Sciences Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. designed and carried out most of the reactions and analyzed the data. Y.X. performed the DFT calculations under the supervision of G.H. X.-F.W. designed and supervised the project. Y.W., X.Q., L.-C.W. and C.X. provided raw material support. X.-F.W., G.H. and Y.W. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Xu, Y., Qi, X. et al. Amines tuned controllable carbonylation for the synthesis of γ-lactones and 1,4-diones. Nat Commun 16, 6305 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61762-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61762-6