Abstract

High-precision birefringence detection is crucial in many fundamental and applied research fields such as chirality detection, optical clocks and quantum information. Although numerous techniques have been demonstrated to detect birefringence in optical materials, the current detection precision typically remains at 10−8. Here we introduce a different physical mechanism for birefringence detection in the classical regime, achieving an accuracy at the 10−11 level. Our technique uses an effective photonic two-level system, dynamically driven by a birefringence-sensitive synthetic magnetic field created by propagation-invariant spin-orbit-coupled structured light in the subwavelength regime. The magnetic field equivalent induces the Rabi oscillation of photonic state, manifested as a nontrivial periodic spin-orbital angular momentum conversion. The ultrahigh detection precision arises from high-birefringence-sensitive topological transition between different oscillatory modes with high Rabi frequencies. The detection precision is tunable by controlling envelope size of structured light at the subwavelength scale. Our technique benefits a broad range of applications involving optical birefringence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Linear birefringence in photonic materials is recognized as a fundamental effect, significantly affecting photonic spin-orbit coupling1,2,3, particularly when the size of the light beam is at the subwavelength level4. In addition, circular birefringence, a typical chiroptical effect5 that left- and right-handed circular polarizations of light propagate through chiral materials at different speeds becomes a powerful tool for detecting material chirality6. Acquiring an exceedingly precise knowledge of the birefringence becomes necessary since it reveals fundamental information about the materials such as their internal structures and molecular orientations7,8. On the other hand, birefringence becomes undesirable in some particular scenarios. For example, some physical fields, such as optical clocks9,10 make use of a high-finesse optical resonator11,12, which requires supermirrors that consist of ideal isotropic coatings. However, the optical coating13, in general, is stressed nonuniformly in the deposition process, adding a small amount of stress-induced birefringence, which limits the performances of the optical resonators. Another example is that crystallized silicon being an important material in gravitational wave detection exhibits small birefringence14,15,16, which largely reduces interferometric contrast and generate signal disturbances in an interferometer. In optical communications, an extremely small amount of birefringence produces light field distortions after photon propagation in the fiber17,18. Therefore, high-precision determination of the very tiny birefringence for the photonic materials is essential in many specific scenarios, for either better exploiting or avoiding it.

Many techniques for the determination of the photonic birefringence have been demonstrated. An early approach, which depends on a photoelastic polarization modulator, has been demonstrated and leads to a detection accuracy at the level of Δn ~10−3 19. Since then, a number of birefringence detection methods have been demonstrated, improving the precision. These include methods based on laser feedback effect (Δn ~10−4)20, total internal reflection (Δn ~10−5)21, Fabry-Perot cavity (Δn ~10−6)11 and interference (Δn ~10−7)22,23,24,25. These detection techniques are either sensitive to photon propagation path that is difficult to be optimized or influenced by inhomogeneous thickness of the optical materials. As a consequence, it seriously limits their measurement accuracy, thus far, to the level of Δn ~10−7. Recently, high-purity polarimetry, based on the high-brilliance synchrotron radiation, has been demonstrated to probe the very low birefringence in the condensed matter systems26. By exploiting a combination of the weak-value amplification (quantum weak measurement) technique27 and ultrafast time-delay control method in the quantum regime, one has achieved an improvement of the accuracy at the level of Δn ~10−8 28. In this article, we report a different physical mechanism for birefringence detection in the classical regime, achieving an accuracy of birefringence at the level of Δn ~10−11, which is better than the previously reported precision by three orders of magnitude.

Our technique relies on a fundamental phenomenon of the Rabi oscillation, which was originally demonstrated as a quantum effect in a quantum two-level system29. Such an important effect has stimulated a number of applications ranging from quantum state measurements and quantum computings30,31 to atomic spectroscopies32. Since its discovery, the concept of Rabi oscillation has been extended to other disciplines including optics33,34,35,36, acoustics37, and atomic physics38, allowing to detect precise information about material structures39, molecule reactions40,41, chemical environments42, etc. Although the Rabi oscillations as well as the relevant Rabi coherent controls of quantum states43 attract a great fundamental and applicable interest across different domains, to our knowledge, this phenomenon has not yet been exploited for precise detection of optical birefringence.

To demonstrate our idea, we require to realize a unique spin-orbit-coupled Rabi oscillation44, which incorporates photonic spin and orbital angular momenta (SAM and OAM). This requires a spatially structured light that comprises a coherent superposition of orthogonal polarization eigenstates with nontrivial topological wavefronts44,45. Our technique is therefore closely relevant to a nontrivial topological transition of photonic state between two spin-orbit-coupled Rabi oscillatory modes. To address this, we build a direct relationship between the spin-orbit Rabi frequency and birefringence, by using a uniquely size-controlled propagation-invariant structured light. Using such a unique structured light, we are able to achieve tunable detection precision by spatially varying beam size. Specifically, if the beam size is at the subwavelength region, a very tiny birefringence with a value at the level of Δn ~10−11 is assuredly detected; while in the non-subwavelength region, the Rabi oscillation frequency is considerably decreased, which leads to less birefringence-sensitive topological transition and a relatively poor detection precision at the level of Δn ~10−9. The tunable light beam permits us to precisely control its topological transition in the Rabi oscillations, providing an effective technique for precise birefringence detection. We note that although the phenomenon of the spin-orbit Rabi oscillation was first demonstrated in ref. 44, here we apply such an effect to realize precise birefringence detection, with tunable measurement sensitivity.

Results

Theoretical model

Figure 1a illustrates the operation principle. First, we define an effective two-level system by considering two orthogonal photonic states as pseudo spin up and spin down, written as \(\hat{R}=\exp \left(+i\ell \phi \right)\left(\hat{x}-i\hat{y}\right)/\sqrt{2}\), and \(\hat{L}=\exp \left(-i\ell \phi \right)\left(\hat{x}+i\hat{y}\right)/\sqrt{2}\), respectively, where \(\hat{x}\) and \(\hat{y}\) are unitary vectors in the cartesian coordinate system (x, y) and \(\phi=\arctan \left(y/x\right)\). ℓ represents a topological charge of the state. These photonic states are spin-orbit coupled, uniquely featured by a nontrivial helical wavefront (orbital angular momentum) and a homogeneous circular polarization (spin angular momentum). Second, we demonstrate the use of a synthetic magnetic field for adiabatically driving the “two-level” system. The physical origin of the synthetic magnetic field is connected to the two-level quantum system, whose Hamiltonian (H \(=-\sigma \cdot \hat{{{{\bf{B}}}}}\), where σ denotes the Pauli matrix vector46) is associated with an external magnetic field \(\hat{{{{\bf{B}}}}}\). We study the interaction between the spin-orbit photonic state and photonic crystal, and develop an equivalent Hamiltonian model H = −σ ⋅ B for the “two-level” system, where B is an equivalent (synthetic) magnetic field. It is contributed from inhomogeneous distribution of structured light and structural parameters of the photonic crystal, hence being birefringence-sensitive. In the presence of B, we realize photonic topological transition, as a result of a precession of the state vector S around the birefringence-sensitive magnetic field B (Fig. 1b). In this process, we obtain a nontrivial coupling between \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\), and a mixing state expressed as \(\Phi={\Phi }_{R}\hat{R}+{\Phi }_{L}\hat{L}\). The resultant state vector is therefore defined as S = Φ†σΦ, where “†” denotes conjugate transpose operator. Obviously, the mixing state comprises different weights on \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\), which can be described in a normalized form as47,48\({\Phi }_{R}=\sin (\theta /2)\exp (+i\varphi /2)\) and \({\Phi }_{L}=\cos (\theta /2)\exp (-i\varphi /2)\), where θ and φ denotes polar and azimuthal angles, respectively. These sets of fundamental parameters define a spin-orbit Poincaré sphere (Fig. 1b), which unifies all possible photonic states via the Stokes parameters (S1, S2, S3).

a Our precision detection technique is based on a spin-orbit two-level system driven by the synthetic magnetic field which is birefringence-sensitive. The two-level system is defined by two orthogonal spin-orbit photonic states \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\), which represent the pseudo spin up and spin down, respectively. An initial state comprising a superposition of \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\) is sent to the system and evolves adiabatically in the presence of birefringence-sensitive magnetic field. As a result, a slight change of the birefringence leads to a significant topological transition of photonic states, as manifested by a prominent variation of topological wavefront (featured by a charged number ℓ). b A spin-orbit Poincaré sphere is defined for geometrical representation of precession of the photonic state vector S around the synthetic magnetic field B. The spin-orbit state vector exhibits evolution along a direction perpendicular to B, leading to nontrivial mutual conversion between photonic spin and orbital angular momenta (SAM and OAM).

Our technique for tiny birefringence detection requires a high birefringence-sensitive topological transition of the spin-orbit state. We realize such a transition by precisely controlling Rabi frequency shift between two different spin-orbit Rabi oscillatory modes through action of the synthetic magnetic field. Thus, we require to reveal a clear relationship between the synthetic magnetic field and the birefringence, by exploiting analogies between the two-level system in a light-crystal interaction process and the electron spin-1/2 system subjected to an external magnetic field46. The photonic crystal is characterized by its refractive index along three principal axis: nx, ny, and nz. We consider a state evolving along optical axis z of the crystal. In this limit, we achieve magnetic-like Hamiltonian of the synthetic system (see Methods), written as

Here, Δβ = βy − βx (βx,y = k0nx,y) is a phase mismatch quantity arising from the birefringence (Δn = ∣ny − nx∣). It features nontrivial coupling between the two pseudo spins and mutual transformation between SAM and OAM. k0 = 2π/λ denotes a free-space wavenumber, with λ being the wavelength. We further introduce parameters \({\gamma }_{x,y}=1-{n}_{x,y}^{2}/{n}_{z}^{2}\) to describe crystal anisotropy. A small birefringence simplifies the Hamiltonian and gives rise to \(\bar{\beta }\approx \left({\beta }_{x}+{\beta }_{y}\right)/2\) and \(\bar{\gamma }\approx \left({\gamma }_{x}+{\gamma }_{y}\right)/2\). In this case, the Hamiltonian leads to an analogous spin-1/2 model

where \(M=2\bar{\beta }\tilde{A}/(2-\bar{\gamma })\) denotes effective mass of the spin-orbit state, with \(\tilde{A}\) being an envelope field for carrying the state. \({{{{\bf{P}}}}}_{\perp }^{2}=[-{\nabla }_{\perp }^{2},0;0,-{\nabla }_{\perp }^{2}]\) is a transverse momentum operator. Since equation (2) demonstrates an identical mathematical form to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation46, intriguing spin transport phenomena can be emulated with structured light, under the action of the synthetic magnetic fields49,50,51,52. In the circular basis, a theoretical model for the synthetic magnetic field is derived as: \({B}_{1}=-\bar{\gamma }{\nabla }_{xy}^{2}\tilde{A}/(\bar{\beta }\tilde{A})\), B2 = 0, and B3 = −Δβ.

With an approximation of nondiffracting light beam, equation (2) admits unique harmonic Rabi oscillatory solutions, manifested by a periodic conversion between two photonic states with opposite helicities (topological wavefronts). We demonstrate such harmonic solutions in terms of the Stokes parameter defined as \({S}_{2}(z)=| {\Phi }_{R}{| }^{2}-| {\Phi }_{L}{| }^{2}={S}_{3}(0)\sin (\Omega \cdot z)+{S}_{2}(0)\cos (\Omega \cdot z)\), with a phase offset determined by an initial state vector S(0) = [S1(0), S2(0), S3(0)]. Here Ω represents the Rabi oscillation frequency expressed as

Equation (3) reveals that the Rabi oscillation depends on the envelope field \(\tilde{A}(x,y)\) and the birefringence Δn. It therefore allows to read out of birefringence value by detecting the topological wavefront variation.

We produce large synthetic magnetic field strength, which leads to a high Rabi frequency. Owing to the unique spatial gradient effect (\({\nabla }_{xy}^{2}\)) on amplitude \(\tilde{A}\), we achieve the high Rabi frequency by using a nondiffracting subwavelength envelope \(\tilde{A}(x,y)\). The resultant magnetic field equivalent effectively inhibits decaying of the Rabi oscillation and thus generates a prominent phase shift (manifested by a topological transition) in two slightly different Rabi oscillatory modes. We express the envelope as \(\tilde{A}(r)={J}_{\ell }(r/{r}_{0})\), where Jℓ is the Bessel function of order ℓ, and \(r={({x}^{2}+{y}^{2})}^{1/2}\). r0 features the envelope width, being an important beam parameter that is associated with the Rabi frequency.

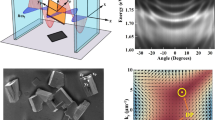

Figure 2 illustrates a theoretical result that a tiny birefringence at the magnitude level of 10−11 can be identified, with a typical beam parameter r0 = 130 nm. We consider a featured state initially located at an equatorial position (θ, φ) = (π/2, π/2). This is because it contains non-separable SAM and OAM (both SAM and OAM are zero), exhibiting a trivial topology (see starting point at c1 in Fig. 2a, as well as its polarization and phase in Fig. 2d, h, respectively). Without birefringence (Δn = 0), the propagation-invariant synthetic magnetic field yields a harmonic oscillation (Fig. 2a). We then select an appropriate coupling length, such that the output photonic state returns to its original equatorial position (see output point c2 in Fig. 2a). Regarding the coupling length, there is in principle no constraint on it. However, the length should be chosen such that the undesired phase shift is effectively eliminated. This requires the coupling length to be an integer multiple of the Rabi oscillation period. For example, the length L = 240 μm is equal to four cycles of Rabi evolution, see Fig. 2a. With a different length, one can appropriately adjust the incident beam width r0 to eliminate the phase shift, since r0 is associated with the Rabi frequency. We plot polarization and phase distributions of the output state, which exhibits a space-variant linear polarization (Fig. 2e) and trivial phase wavefront (Fig. 2i). These preliminary results indeed suggest a complete cyclic evolution of state in the crystal. By contrast, with birefringence (Δn ≠ 0), a Rabi frequency shift given by \(\Delta \Omega=\bar{\beta }\tilde{A}{({k}_{0}\Delta n)}^{2}/(2\bar{\gamma }{\nabla }_{xy}^{2}\tilde{A})\) leads to birefringence-sensitive topological transition of spin-orbit state. Figure 2b shows that introducing a tiny birefringence Δn = 10−11 leads to an obvious phase shift, in comparison with the case without birefringence (Fig. 2a). The output photonic state features a trivial-to-nontrivial topological transition, as evident from its distinct inhomogeneous elliptical polarization (Fig. 2f) and topological phase wavefront (Fig. 2j). The larger birefringence value results in more pronounced phase shift (Fig. 2c). As a result, the separated SAM and OAM become more pronounced, see the near-circular polarization and helical phase distributions in Fig. 2g, k. Thus, the birefringence-induced change of topological wavefront allows us to quantitatively determine the change of optical birefringence.

a–c Harmonic Rabi oscillations of a photonic state between the pseudo spin up and spin down components, represented as S2(z) = ∣ΦR∣2 − ∣ΦL∣2. These harmonic oscillations are achieved with an initial state [located at (θ, φ) = (π/2, π/2)] carried by a subwavelength BG envelope (envelope parameter r0 = 130 nm), in different conditions of birefringence: a n = 0; b Δn = 10−11; and c Δn = 10−10. For a given coupling length L = 240 μm, the output spin-orbit state exhibits a prominent birefringence-sensitive phase shift indicated by points c2, c3, and c4, with respect to the incident one (point c1). The resultant Rabi oscillation period is calculated as: a Λ = 60.00 μm; b Λ = 58.43 μm; and c Λ = 56.84 μm. d–g Inhomogeneous polarization distributions of the photonic state at the initial (d, input point c1) and final (e, f, and g, output points c2, c3, and c4) positions of the crystal. h–k Inhomogeneous phase distributions of the photonic state at positions corresponding to (d–g), featuring OAM variations.

Experimental demonstration

Experimentally, we should produce the nondiffracting envelope at the subwavelength scale, which remains a challenge because topology of the spin-orbit state is vulnerable when its transverse dimension is at the subwavelength level53,54. To overcome the obstacle, we utilize a combination of an inhomogeneous optical wave plate and an ultrathin metallic disc to prepare for the expected state. The wave plate exhibits a space-dependent optical axis with its orientation in the transverse plane described by a formula α = qϕ + α055, where q is a charge number determining topology of the spin-orbit state, and α0 denotes its initial axis orientation. Its Jones matrix is given by \([\cos (2\alpha ),\sin (2\alpha );\sin (2\alpha ),-\cos (2\alpha )]\)55. Given an incident plane-wave polarization along the x-axis and a charge number q = 1/2, the resultant polarization from the wave plate is denoted as [\(\cos (\phi+2{\alpha }_{0});\sin (\phi+2{\alpha }_{0})\)], which positions at the equator of the first-order (ℓ = 1) Poincaré sphere (see “Methods”). At this stage, the generated spin-orbit state is carried by the Laguerre-Gaussian (LG) envelope. We then use an ultrathin metallic disc to transform the large-scale LG envelope into weakly diffracting subwavelength-scale Bessel-Gaussian (BG) envelope, while maintaining the spin-orbit state unchanged. Note that we cannot generate such a subwavelength-structured light that is completely nondiffracting because of the Gaussian truncation. The BG envelope is a consequence of in-phase superposition of many high-spatial-frequency propagating waves excited by the metallic edge, while retention of the spin-orbit state is a result of circular symmetry of the disc that allows to fully recover incident phase and polarization (see “Methods”).

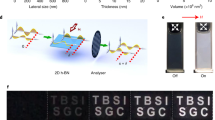

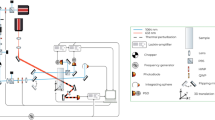

We build an experimental setup (Fig. 3a) for characterizing the prepared state and hence detecting the tiny birefringence with it. A linearly polarized He-Ne laser (λ = 632.8 nm) is divided by a beam splitter, forming a Mach–Zender interferometer. One of the separated beam (signal beam) passes through the combined element (inset I), generating the spin-orbit state at the subwavelength scale (more details see Supplementary Fig. 1 in Sec. A). A microscopic system comprising an objective lens (Nikon, 150× , numerical aperture 0.9), a tube lens and a charge-coupled device (pixel size 1.85 μm) is utilized to measure the envelope field. Figure 3b illustrates the recorded intensity distribution, showcasing the BG envelope profile, with the beam parameter measured as r0 = 130 nm and a peak-to-peak envelope width measured as 466 nm (more details see Supplementary Fig. 2 in Sec. A). To characterize the spin-orbit state, we insert a linear polarizer into the system, measuring its horizontal and vertical polarization components, see Fig. 3c and d respectively. These measurements are in accordance with the simulations (Fig. 3e–g) performed with a state positioned at (θ = π/2, φ = π/2) of the first-order (ℓ = 1) Poincaré sphere. To detect the wavefront, we superimpose the state with another separated beam as a reference beam. Figure 4a presents the recorded spherical-wave interference pattern, in an agreement with the simulated outcome (Fig. 4d). Both the interferograms exhibit concentric circular fringes, indicating a trivial non-helical wavefront. This suggests a generated equatorial spin-orbit state. Our setup includes a high-precision position tracking system (inset III in Fig. 3a), allowing to characterize nondiffracting property of the subwavelength BG envelope and monitor wavefront variations of the spin-orbit states. The tracking system is realized by mounting the objective lens onto an electrical-control piezoelectric transducer stage with a step resolution up to 5 nm. It not only allows to characterize the envelope field at specific propagation distance (see Supplementary Fig. 2 in Sec. A), but also permits us to find an appropriate envelope width to calibrate the Rabi frequency for a given coupling length. This allows to eliminate additional phase shift of the emerging state from the crystal with respect to the incident one.

a An experimental setup. A linearly polarized He-Ne laser operating at the fundamental Gaussian mode with wavelength λ = 632.8 nm is separated into two paths by a beam splitter (BS). One path as the signal beam passes through a combined optical element (inhomogeneous wave plate plus ultrathin metallic disc, see inset I), generating the expected equatorial spin-orbit state at the subwavelength scale. The initially prepared state is then sent to an electrically engineered photonic crystal (see inset II), whose birefringence can be transversely modulated through an external voltage U. A microscopic system [comprising objective lens (OB), tube lens (TL), polarizer (P) and charge-coupled device (CCD)], together with a precision position tracking system (inset III), is built for observing the birefringence-sensitive spin-orbit topological transition. Another path as a reference beam interferes with the emerging beam from the crystal, detecting the phase wavefront of the output photonic state. b–d Experimental characterization of the initial state at the input end of the crystal: b the experimentally recorded BG envelope field with envelope parameter measured as r0 = 130 nm (the peak-to-peak size 466 nm); c the horizontal polarization; and d the vertical polarization. e–g Simulation results corresponding to b–d. b–g share identical scale with scale bar being 500 nm.

The experiments are performed based on the prepared initial state (π/2, π/2) and the subwavelength BG envelope (r0 = 130 nm). a–c Experimentally recorded spherical-wave interference patterns: a at the input end of the crystal; b at the output end of the crystal but without birefringence modulation (Δn = 0); c at the output end of the crystal with a tiny birefringence (Δn = 9.48 × 10−11 ± 7.23 × 10−12). d–f The simulation outcomes corresponding to the experiments a–c. All panels share identical scale, with scale bar being 10 μm.

We perform a non-contacting experiment based on an electrically engineering lithium niobate (LN) crystal (inset II in Fig. 3a), which can reduce instability caused by man-made operation. In the presence of transverse modulation, the refractive index along the principal axis is given by \({n}_{x}={n}_{{{{\rm{o}}}}}+0.5{n}_{{\mbox{o}}\,}^{3}{d}_{22}{E}_{\perp }\), \({n}_{y}={n}_{{{{\rm{o}}}}}-0.5{n}_{{\mbox{o}}\,}^{3}{d}_{22}{E}_{\perp }\)56, where no = 2.2863 denotes the ambient refractive index, d22 = 6.8 pm/V (at λ = 632.8 nm) the electro-optic coefficient, and E⊥ the transverse electric field applied to the crystal. Therefore, the birefringence in our setting is electrically controlled and expressed as Δn = \({n}_{\,{\mbox{o}}\,}^{3}{d}_{22}{E}_{\perp }\). Since the coupling length of the LN crystal is insufficient to deposit efficient coatings and apply electrodes on the top and bottom surfaces, we add contacts to its front and back faces with transverse dimension: b × b = 10 × 10 mm (inset II in Fig. 3a). The effective electric field applied to the crystal is denoted as E⊥ = U/d, where U is the external voltage, d the relative distance \(d={[{(b-{b}^{{\prime} })}^{2}+{L}^{2}]}^{1/2}\)/cos(η), \({b}^{{\prime} }\) the width of the conducting films and η is defined in the inset (more details see Supplementary Fig. 3 in Sec. B).

We first observe the spin-orbit Rabi oscillation without birefringence modulation (Δn = 0). We present the measured and theoretical spherical-wave interference patterns (Fig. 4b, e), with a beam parameter r0 = 130 nm, showcasing the expected circular fringes after calibrating the detection system. These results are similar to those free-space measurements (Fig. 4a, d), suggesting that the spin-orbit state exhibits a periodic evolution in the presence of the synthetic magnetic field and indeed returns to its original equatorial position. When the voltage is increased to U = 7.0 × 10−3 V, corresponding to a birefringence of Δn = 9.48 × 10−11, we observe irregular interference patterns (Fig. 4c, f): the interferograms contain a form of spiral fringes rather than the regular circular ones. This distinct wavefront variation is caused by an inclusion of the tiny birefringence, which leads to an increase of the Rabi frequency in the system (see Eq. 3) and hence causes a more rapid conversion between the pseudo spin up and spin down states, as compared to the case without birefringence. The measurement indicates an output photonic wavefront with a nontrivial topological charge being ℓ = 1. On the other hand, we present additional plane-wave interference patterns, observing a prominent bifurcation point in the fringes, which corresponds to a vortex phase singularity (ℓ = 1). This also shows sharp contrast to those regular plane-wave fringes both in free space and in crystal but without birefringence modulation (see Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 in Sec. C). These experimental observations are in agreement with the simulation outcomes. To measure the uncertainty, we maintain experimental conditions unchanged and repeat the measurements for 30 times (see Supplementary Fig. 6 in Sec. D). The recorded voltage shows slight fluctuation. The uncertainty of the birefringence is measured as ±7.23 × 10−12, according to the uncertainty of the recorded voltage. Clearly, the uncertainty is significantly below the detection precision, demonstrating reliability of our technique. More details are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6 in Sec. D.

Decreasing the Rabi frequency relatively degrades the detection precision. For example, we select two larger BG envelopes: r0 = 0.55 and 2.76 μm. We observe the corresponding birefringence-induced topological transitions. Without birefringence, we observe regular circular fringes in the spherical-wave interferograms in both envelope cases (Fig. 5a, c). These measurements confirm that the associated spin-orbit states undergo a full cycle evolution in the respective Rabi oscillatory modes and then return to their original equatorial position. However, in the case of r0 = 0.55 μm, the observation of a significant topological transition (Fig. 5b) requires to increase the applied voltage to U = 1.23 × 10−1 V ± 6.31 × 10−4 V, corresponding to a birefringence Δn = 1.67 × 10−9 ± 8.54 × 10−12; whereas with an even larger BG envelope r0 = 2.76 μm, the topological transition (Fig. 5d) requires a larger birefringence Δn = 7.14 × 10−9 ± 2.06 × 10−11 (the corresponding voltage is U = 5.27 × 10−1 V ± 1.51 × 10−3 V). This phenomenon is explained by insufficient phase shift in the Rabi oscillatory mode with smaller frequency. Thus, a large birefringence compensates for the topological transition.

The experiments are performed based on two different BG envelopes: r0 = 0.55 μm (a, b) and r0 = 2.76 μm (c, d), while maintaining the initial state unchanged. a, c Experimentally recorded spherical-wave interference patterns at the output end of the crystal without birefringence modulation (Δn = 0); b, d Experimentally recorded spherical-wave interference patterns at the output end of the crystal with birefringence modulation, yielding the detection accuracy: b Δn = 1.67 × 10−9 ± 8.54 × 10−12 (r0 = 0.55 μm) and d Δn = 7.14 × 10−9 ± 2.06 × 10−11 (r0 = 2.76 μm). e–h The simulation outcomes corresponding to the experiments (a–d). All panels share identical scale, with scale bar being 10 μm.

We demonstrate detection precision Δn(r0) as a function of the envelope width (Fig. 6a, blue curve). Depending on this relationship, we cautiously classify the detection precision into subwavelength and non-subwavelength regions, separated by r0 ≈ 0.5λ. At the subwavelength region I, we obtain ultrahigh detection precision with birefringence value reaching 10−11 level. The precision increases dramatically with a decrease of the envelope width (inset in Fig. 6a). To quantitatively characterize the detection sensitivity to the variation of r0, we calculate the curve slope using the experimental data at the subwavelength region I, approximately yielding \([\Delta n({r}_{0}^{2})-\Delta n({r}_{0}^{1})]/({r}_{0}^{2}-{r}_{0}^{1})\approx 1.44\times 1{0}^{-11}\) nm−1. Such a relationship indeed suggests an important technique to detect very tiny birefringence by shrinking structured light to the subwavelength scale. By contrast, a larger envelope at the non-subwavelength region II reduces the detection precision. Particularly, when r0 is considerably larger than the wavelength, the detection precision is reduced to the level of 10−9 while the sensitivity becomes 2.59 × 10−12 nm−1. Figure 6 suggests a different physical mechanism, namely considering structured light to effectively tune the detection precision.

The tunable detection precision can be achieved by carefully varying the BG envelope width or crystal coupling length. a The experimentally obtained detection precision as a function of envelope parameter r0, for two different coupling lengths: L = 180 μm (red line) and L = 240 μm (blue line). Based on these data, we can reasonably separate the detection precision into regions I and II, where the sensitivity (curve slope) to the envelope parameter is measured as 1.44 × 10−11 nm−1 and 2.59 × 10−12 nm−1, respectively. Values of experimental data in (a) are fitting plus s.e.m (10%). b Difference between detection precisions obtained by these two different coupling lengths. c, d Experimentally recorded spherical-wave interference patterns at the output end of the crystal: c without birefringence modulation and d, with a tiny birefringence (Δn = 2.38 × 10−10 ± 7.04 × 10−12). e, f The simulations corresponding to the experiments c and d. c–f Share the same scale with scale bar being 10 μm.

Finally, we examine influence of a different crystal coupling length on the detection precision. We choose a smaller coupling length as L = 180 μm, while maintaining the envelope width (r0 = 130 nm) unchanged. Such a coupling length is three times the period of the Rabi oscillation. Without birefringence, our measurement suggests that the spin-orbit state returns to its original equatorial position after evolution along the crystal, as manifested by the regular circular fringes in Fig. 6c. Then we detect the topological transition by introducing a tiny birefringence of Δn = 2.38 × 10−10 ± 7.04 × 10−12 with an voltage U = 1.79 × 10−2 ± 9.00 × 10−4 V. A generation of spiral fringes with a topological charge of ℓ = 1 is observed (Fig. 6d). The experimental measurements (Fig. 6c, d) match well to the corresponding simulations (Fig. 6e, f). These results, together with those obtained by a coupling length L = 240 μm, suggest that decreasing the coupling length would reduce the measurement precision. We present more experimental data to confirm the assertion, see the plot which shows the detection precision as a function of r0 (red curve in Fig. 6a). Clearly, the detection precision is relatively poor for smaller coupling length (L = 180 μm), while it shows a similar trend to the curve Δn(r0) achieved with L = 240 μm. Note that because of weakly diffraction of the BG envelope, we cannot obtain unlimited increase in detection sensitivity by extrapolating the coupling length. Figure 6b depicts the difference between precisions obtained by these two different coupling lengths, showing an approximately linear increasing function of the BG envelope parameter. It means that the detection precision is not obviously different when the beam parameter r0 locates at the subwavelength region; however, at the non-subwavelength region, even if the coupling length of the crystal is only different by one cycle, the difference in detection accuracy becomes non-negligible for a given r0.

Discussion

In summary, we have reported theoretical and experimental observations of birefringence-sensitive topological transitions of photonic states in a synthetic two-level system, and demonstrated successful application of such a topological phenomenon in the precision detection of tiny birefringence, with accuracy reaching Δn ~10−11 level. The nontrivial topological transition is resulted from a pronounced birefringence-induced phase shift between different photonic Rabi oscillatory modes with high oscillating frequencies. We have presented a formulism that clearly shows the magnetization-birefringence connection and reveals how to enhance the synthetic magnetic strength using the propagation-invariant subwavelength envelope. Such a unique synthetic magnetic field allows precise engineering of the Rabi oscillatory modes, opening up an efficient manner to effectively control the topological transition of photonic states. Thus, our detection technique uniquely combines subwavelength generation of nonspreading envelope for the photonic state, high-frequency photonic Rabi oscillations enabled by the strong synthetic magnetic field, and electrically controlled topological transitions. As a result, the presented technique offers much higher sensitivity and less systematic instability than previous demonstrations19,20,22,23,24,25. We emphasize that tiny birefringence detection with ultrahigh precision has been recognized as an important technique in testing small birefringence in an optical fiber and coating process for optical mirrors, benefiting many applicable fields11,12,15. In this aspect, we also demonstrate how our results are closely connected to the interesting fields such as precisely detecting THz wave frequency, manipulating quantum entangled states and significantly improving sensitivity of birefringent interferometer. Specific applicable schemes are presented in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8 in Sec. E.

In addition, our demonstration suggests precise detection of a tiny variation of structured light with nanometric spatial resolution. Figure 6a suggests that the Rabi oscillations demonstrate an ultrahigh sensitivity to the beam parameter, which provides a different technique for precise detection of the beam variation. To achieve this, it requires to produce a fast Rabi oscillation between pseudo spin down and spin up. Obviously, the Rabi oscillation is highly sensitive to the spatial variation of structured light, leading to high-sensitive beam-dependent Rabi oscillatory modes. We therefore expect that a very tiny change of the beam parameter results in significant topological transition. Moreover, the presented two-level system, which is equivalent to those governed by the Pauli wave equation46, allows us to investigate other intriguing birefringence-sensitive or beam-dependent topological phenomena such as the topological Hall effect57 and Stern-Gerlch effect51,52 using the spin-orbit photonic states. These prospects are intriguing and become possible by appropriately engineering the synthetic magnetic fields either by the designed structured light or the birefringence of the photonic crystal. Our results, together with these prospects discussed above, hold immense potential across various applications48.

Methods

Derivation of the theoretical model

We introduce an effective two-level system with the pseudo spin up and spin down being two orthogonal spin-orbit photonic states \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\), respectively. Such spin-orbit states are defined in the higher-order optical regime, exhibiting nontrivial topological wavefront, which allows to realize topological transition in the presence of birefringence-sensitive synthetic magnetic field.

We begin our derivation from the following Maxwell’s equation

where \({\tilde{{{\mathbf{\Psi }}}}}\) denotes a complex amplitude in the spatiotemporal domain (x, y, z, t). \(\hat{\epsilon }\) and μ express fundamental dielectric tensor and permeability of the photonic crystal, respectively. We examine spin-orbit state evolution along propagation direction z based on the Maxwell wave equation. This can be achieved by expressing the complex light field in a form written as44

where ω is the carrier-wave frequency. \({{{\mathbf{\Psi }}}}={\Psi }_{x}\hat{x}+{\Psi }_{y}\hat{y}+{\Psi }_{z}\hat{z}\) (\(\hat{x},\hat{y},\hat{z}\) are unitary vectors associated with x, y, z axis, respectively) denotes spatial components of the complex amplitude. In the Cartesian coordinate system, we obtain a three-component coupled-wave equation, written as follows

where \({\beta }_{j}=\omega \sqrt{\mu {\epsilon }_{j}}\,\left(j=x,y,z\right)\) represents propagation constant of the wave component Ψj in the photonic crystal. We take into account a solution of the coupled-wave equation as follows

and consider approximation of the slowly varying amplitude with propagation distance, i.e., \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{A}_{x}}{\partial {z}^{2}}\;\ll \;{\beta }_{x}\frac{\partial {A}_{x}}{\partial z}\) and \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}{A}_{y}}{\partial {z}^{2}}\;\ll\; {\beta }_{y}\frac{\partial {A}_{y}}{\partial z}\). Under these conditions, we simplify the above coupled-wave equation as

where \({\nabla }_{\perp }^{2}={\nabla }_{xx}+{\nabla }_{yy}\) denotes a Laplace operator. We expand the term ∇ ⋅ Ψ in the Cartesian coordinate system, and consider using the constraint condition

As a consequence, we obtain a general Schrödinger-like equation governing the evolution dynamics of photonic state in the crystal. It is expressed as

where \(\bar{\beta }\approx \left({\beta }_{x}+{\beta }_{y}\right)/2\) for a shallow birefringence. We introduce another parameter: \({\gamma }_{j}=1-{n}_{j}^{2}/{n}_{z}^{2}\) (j = x, y and \({n}_{j}=\sqrt{{\epsilon }_{j}}\)) to describe photonic anisotropy. The value of γj can be either negative or positive, relying on crystal polarity. Given shallow birefringence, we reasonably assume \(\bar{\gamma }\approx \left({\gamma }_{x}+{\gamma }_{y}\right)/2\). Δβ is a phase mismatch, defined as Δβ = βy − βx. It arises from birefringence of the crystal which leads to a mutual coupling between Ax and Ay.

Since the Schrödinger-like equation contains rapid oscillatory terms \(\exp (\pm i\Delta \beta \cdot z)\), it is relevant to demonstrate photonic spin-orbit dynamics in a rotating frame44,49. We achieve this by using the following transformation

In this rotating frame, the Schrödinger-like equation is modified as

To obtain an equivalent of the Pauli equation, which describes spin dynamics of a quantum particle in a driven magnetic field46, we further transform the present setting from the Cartesian basis (x, y) into the circular basis (\(\hat{R},\hat{L}\)), via a transformation matrix \(T=\left[1,-i;1,i\right]\). This transformation yields a magnetic-like Hamiltonian

In the circular basis, the complex light field can be expressed as a superposition of \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\) with different weights ΦR and ΦL, i.e., it can be written as

These weight coefficients become propagation-variant during state evolution and can be expressed in a normalized form as \({\Phi }_{R}\left(z\right)=\sin \left[\theta \left(z\right)/2\right]\exp \left[+i\varphi \left(z\right)/2\right]\) and \({\Phi }_{L}\left(z\right)=\cos \left[\theta \left(z\right)/2\right]\exp \left[-i\varphi \left(z\right)/2\right]\), respectively47,48. Thus, a pseudo spin defined in this setting can be denoted as Φ = (ΦR; ΦL), which can be geometrically represented as a point on the normalized higher-order Poincaré sphere47. Substituting the expression of \({\tilde{{{\bf{A}}}}}\left(x,y,z\right)\) into the Schrödinger-like equation, we obtain the Pauli equation equivalent represented in the spin-orbit framework as

where \({{{{\bf{P}}}}}_{\perp }^{2}=\left[-{\nabla }_{\perp }^{2},0;0,-{\nabla }_{\perp }^{2}\right]\), and \(M=2\bar{\beta }\tilde{A}/\left(2-\bar{\gamma }\right)\) is the equivalent mass of the spin Φ. Here σ is the Pauli matrix vector \(\sigma=\left({\sigma }_{1},{\sigma }_{2},{\sigma }_{3}\right)\), in the circular basis having the following form

B represents a magnetic field equivalent presented in the rotating frame. It is a three-component vector field \({{{\bf{B}}}}=\left({B}_{1},{B}_{2},{B}_{3}\right)\), where \({B}_{1}=-\bar{\gamma }{\nabla }_{xy}^{2}\tilde{A}/\left(\bar{\beta }\tilde{A}\right)\), B2 = 0, and B3 = −Δβ. In the presence of the synthetic magnetic field B, the left- and right-circular polarization components become mutually coupling in the course of spin evolution, manifested as a conversion between the spin and orbital angular momenta. Particularly, the Pauli equation admits harmonic oscillatory solutions, when B is propagation-invariant. With an initial state denoted as S = [S1(0), S2(0), S3(0)], we demonstrate such harmonic solutions in terms of: \({\left\vert {\Phi }_{R}\right\vert }^{2}-{\left\vert {\Phi }_{L}\right\vert }^{2}={S}_{3}\left(0\right)\sin \left(\Omega \cdot z\right)+{S}_{2}\left(0\right)\cos \left(\Omega \cdot z\right)\), where the oscillation frequency is expressed as

This formula reveals a close relationship between the spin-orbit oscillation and the birefringence Δn, allowing us to reveal birefringence value by measuring the topological wavefront variation.

Generation of initial spin-orbit photonic states

We design a space-variant wave plate to generate the expected spin-orbit photonic state that is initially represented as an equatorial point of the higher-order Poincaré sphere. To realize such a wave plate, we consider using the nematic liquid crystal sandwiched between two planar glasses and form a 2 × 2 mm (transverse dimension) planar cell58. We choose an appropriate thickness of the liquid crystal to be 6 μm (in the beam propagation direction) such that we can achieve a half-wave retardation between two orthogonal polarization components Ax and Ay, at a specific operation wavelength of λ = 632.8 nm. In this case, we express the Jones matrix of the wave plate as55

where α = qϕ + α0 represents space-dependent orientation angle of the optical axis of the wave plate, with α0 being an initial angle which can be changed by rotating the wave plate with respect to z axis. Here, \(\phi=\arctan (y/x)\), and q features its topological number, which is connected to the topological property of the spin-orbit state. With an incident polarization state of light denoted as Φin = (Px; Py), the output polarization state from the wave plate takes a form of

To illustrate its performance, we consider a setting of topological number as q = 0.5. As a result, the output spin-orbit state Φout can be geometrically represented by the first-order Poincaré sphere. Particularly, if we consider an incident polarization that is along the horizontal direction, i.e., Φin = (1; 0), the output state becomes

Clearly, this outcome is expected, in accordance with the equatorial spin-orbit state, see the Poincaré sphere (Fig. 1b) at an angle of θ = π/2. We emphasize that we can generate all the equatorial spin-orbit state simply by changing the orientation angle α0. This is possible by rotating the wave plate in a specific experimental setup. Since the spin-orbit state contains equal weights on \(\hat{R}\) and \(\hat{L}\), both the SAM and OAM of the initial state are zero, which facilitates experimental observation of the expected topological transitions.

Subwavelength generation of the nonspreading spin-orbit states

Our theoretical model reveals that the high-frequency spin-orbit Rabi oscillation requires a generation of the non-spreading (propagation-invariant) Bessel envelope at the subwavelength scale. We achieve this by utilizing an ultrathin metallic disc which is able to convert the large-scale spin-orbit state carried by the LG envelope into the subwavelength-scale one carried by the nearly nonspreading BG envelope. We theoretically demonstrate this possibility. When an LG structured light propagates through the metallic disc, a partial complex amplitude is binary truncated, leading to high-spatial-frequency diffractive waves, which originate from sharp-edge diffraction of the metallic disc59. The BG-structured light is a result of a coherent superposition of these diffractive waves in the far field.

Theoretically, the envelope field behind the metallic disc is written as

Here zd denotes a position where the metallic disc is placed, and t(x, y) is a transmission function of the disc. Note that the spin-orbit state is presented in the cartesian coordinate system. We solve the diffractive field based on the Rayleigh-Sommerfeld theory60. The envelope field after passing through the metallic disc can be written as

where \(R={[{(x-{x}^{{\prime} })}^{2}+{(y-{y}^{{\prime} })}^{2}+{z}^{2}]}^{1/2}\). Owing to the circular symmetry of the metallic disc, we reveal the nonspreading propagation property of the diffractive field in the cylindrical coordinate: \({x}^{{\prime} }={\rho }^{{\prime} }\cos ({\phi }^{{\prime} })\) and \({y}^{{\prime} }={\rho }^{{\prime} }\sin ({\phi }^{{\prime} })\). The vectorial field at the propagation distance z is obtained as

where \({R}_{0}={z}^{2}+{\rho }_{0}^{2}\) (ρ0 is radius of the disc), and J1 is the first-order Bessel function with the variable being ξ = 2πρ0ρ/(λR0). It shows that the generated BG structured light exhibits an identical spin-orbit state to the initial one, even though the envelope becomes the Bessel form. It means that this particular element allows to completely recover the initial pseudospin state when it passes though the ultrathin disc. It also allows us to detect significant pseudospin precession caused by the subwavelength-induced strong synthetic magnetic field.

Fabrication of the ultrathin metallic disc

To fabricate the metallic disc, we consider using a 50-nm-thick gold film that is initially deposited on a substrate (the thickness is 0.3 mm). To stabilize the disc, we should deposit another chromium film (10 nm thickness) between the gold film and the substrate. These can be done using the physical vapor deposition method. After these processes, a positive photoresist is spin-coated on the gold film. We then bake the sample for several minutes at a temperature of 100 °C, in order to evaporate the solvent as well as to enhance the viscosity of the photoresist. We prepare a mask and place it onto the photoresist. We use a ultraviolet source to shine the sample for about one minute. The shape of the mask is then transferred to the photoresist. Finally, we utilize the ion beam to peel off the undesired gold film from the pattern, and obtain the expected metallic disc with a thickness of only 60 nm. An example of the metallic disc with a radius of ρ0 = 300 μm is presented in Sec. A of Supplementary. Such a disc is able to partially truncate the complex amplitude of light field at the element edge, which, due to the cylindrical symmetry of the disc, causes significant in-phase diffractive waves and generates the expected nondiffracting Bessel beam at the subwavelength scale.

Data availability

All data that supports the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

The custom code used in this study is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Brasselet, E. et al. Dynamics of optical spin-orbit coupling in uniaxial crystals. Opt. Lett. 34, 1021–1023 (2009).

Bliokh, K. Y. et al. Spin-Hall effect and circular birefringence of a uniaxial crystal plate. Optica 3, 1039–1047 (2016).

Guo, C. et al. Dynamic control of cylindrical vector beams via anisotropy. Opt. Express 26, 18721–18733 (2018).

Bliokh, K. Y., Rodríguez-Fortuño, F. J., Nori, F. & Zayats, A. V. Spin-orbit interactions of light. Nat. Photonics 9, 796–808 (2015).

Collins, J. T. et al. Chirality and chiroptical effects in metal nanostrctures: fundamentals and current trends. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1700182 (2017).

Rui, G. & Zhan, Q. Nanophotonic methods for chiral sensing and characterization. Acta Photonica Sinica 51, 0551301 (2022).

Tudi, A., Han, S., Yang, Z. & Pan, S. Potential optical functional crystals with large birefringence: recent advances and future prospects. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 459, 214380 (2022).

Palmer, B. A. et al. X-ray birefringence: a new strategy for determining molecular orientation in materials. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 3216–3222 (2012).

Sherman, J. A. et al. High-accuracy measurement of atomic polarizability in an optical lattice clock. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 153002 (2012).

Bloom, B. J. et al. An optical lattice clock with accuracy and stability at the 1018 level. Nature 506, 71–75 (2014).

Fleisher, A. J., Long, D. A., Liu, Q. & Hodges, J. T. Precision interferometric measurements of mirror birefringence in high-finesse optical resonators. Phys. Rev. A 93, 013833 (2016).

Koks, C., Baalbergen, F. B. & van Exter, M. P. Observation of microcavity fine structure. Phys. Rev. A 105, 063502 (2022).

Winkler, G. et al. Mid-infrared interference coatings with excess optical loss below 10 ppm. Optica 8, 686–696 (2021).

Adhikari, R. X. et al. A cryogenic silicon interferometer for gravitational-wave detection. Class. Quant. Grav. 37, 165003 (2020).

Hamedan, V. J., Adam, A., Blair, C., Ju, L. & Zhao, C. Precision mapping of a silicon test mass birefringence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 064101 (2023).

Ng, T. C. K., Isi, M., Wong, K. W. K. & Farr, W. M. Constraining gravitational wave amplitude birefringence with GWTC-3. Phys. Rev. D 108, 084068 (2023).

Thornburg, W. Q., Corrado, B. J. & Zhu, X. D. Selective launching of higher-order modes into an optical fiber with an optical phase shifter. Opt. Lett. 19, 454–456 (1994).

Samaniego, D., Zoireff, G. & Vidal, B. Brillouin-induced dynamic arbitrary birefringence. J. Light. Technol. 39, 1961–1967 (2020).

Modine, F. A., Major, R. W. & Sonder, E. High frequency polarization modulation method for measuring birefringence. Appl. Opt. 14, 757–760 (1975).

Chen, W., Zhang, S. & Long, X. Thickness and refractive-index measurement of birefringent material by laser feedback technique. Opt. Lett. 38, 998–1000 (2013).

Sokolov, I. M. & Fofanov, J. A. Investigations of the small birefringence of transparent objects by strong phase modulation of probing laser radiation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 12, 1579–1588 (1995).

Lee, J., Shih, H., Hong, C. & Chou, T. K. Measurement of refractive index change by surface plasmon resonance and phase quadrature interferometry. Opt. Commun. 276, 283–287 (2007).

Ghosh, N. & Bhattacharya, K. Polarization phase-shifting interferometric technique for complete evaluation of birefringence. Appl. Opt. 50, 2179–2184 (2011).

Chou, C., Lu, S., Lin, T., Lu, S. & Jeng, R. Environment-noise-free optical heterodyne retardation measurement using a double-pass acousto-optic frequency shifter. Opt. Lett. 41, 5138–5141 (2016).

Ge, B., Zhou, R., Takiguchi, Y., Yaqoob, Z. & So, P. T. C. Single-shot optical anisotropy imaging with quantitative polarization interference microscopy. Laser Photonics Rev. 12, 1800070 (2018).

Schmitt, A. T. et al. Disentangling x-ray dichroism and birefringence via high-purity polarimetry. Optica 8, 56–61 (2021).

Hosten, O. & Kwiat, P. Observation of the Spin hall effect of light via weak measurements. Science 319, 787–790 (2008).

Wang, Y., Chen, S., Wen, S. & Luo, H. Realization of ultra-small stress birefringence detection with weak-value amplification technique. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 161104 (2021).

Rabi, I. I. Space quantization in a gyrating magnetic field. Phys. Rev. 51, 652–654 (1937).

Vijay, R. et al. Stabilizing Rabi oscillations in a superconducting qubit using quantum feedback. Nature 490, 77–80 (2012).

Assemat, F. et al. Quantum Rabi oscillations in coherent and in mesoscopic cat field states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 143605 (2019).

Nishimura, S. et al. Rabi-oscillation spectroscopy of the hyperfine structure of muonium atoms. Phys. Rev. A 104, L020801 (2021).

Kartashov, Y. V., Vysloukh, V. A. & Torner, L. Resonant mode oscillations in modulated waveguiding structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 233903 (2007).

Shandarova, K. et al. Experimental observation of Rabi oscillations in photonic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 123905 (2009).

Zhang, P. et al. Unveiling chiral phase evolution in rabi oscillations from a photonic setting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 123201 (2020).

Liu, G. et al. Higher-order optical Rabi oscillations. Fundam. Res. 3, 898–903 (2023).

Cronenberg, G. et al. Acoustic Rabi oscillations between gravitational quantum states and impact on symmetron dark energy. Nat. Phys. 14, 1022–1026 (2018).

Bludov, Y. V., Konotop, V. V. & Salerno, M. Rabi oscillations of matter-wave solitons in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 80, 023623 (2009).

Vasa, P. et al. Real-time observation of ultrafast Rabi oscillations between excitons and plasmons in meta nanostructures with J-aggregates. Nat. Photonics 7, 128 (2013).

Bertaina, S. et al. Quantum oscillations in a molecular magnet. Nature 453, 203 (2008).

Pan, S. et al. Rabi oscillations in a stretching molecule. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 35 (2023).

Atzori, M. et al. Room-temperature quantum coherence and Rabi oscillations in vanadyl phthalocyanien: toward multifunctional molecular spin qubits. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2154 (2016).

Bose, R., Cai, T., Choudhury, K. R., Solomon, G. S. & Waks, E. All-optical coherent control of vacuum Rabi oscillations. Nat. Photonics 8, 858–864 (2014).

Liu, G. et al. Spin-orbit Rabi oscillations in optically synthesized magnetic field. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 205 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Geometric control of vector vortex light beams via a linear coupling system. Opt. Express 29, 30694 (2021).

Scully, M. O., Lamb, W. E. & Barut, A. Theory of the Stern-Gerlach apparatus. Found. Phys. 17, 575 (1987).

Milione, G., Sztul, H. I., Nolan, D. A. & Alfano, R. R. Higher-order Poincaré sphere, stokes parameters, and the angular momentum of light. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 053601 (2011).

Forbes, A., de Oliveira, M. & Dennis, M. R. Structured light. Nat. Photonics 15, 253–262 (2021).

Karnieli, A. & Arie, A. All-optical Stern-Gerlach effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 053901 (2018).

Karnieli, A., Tsesses, S., Bartal, G. & Arie, A. Emulating spin transport with nonlinear optics, from high-order skyrmions to the topological Hall effect. Nat. Commun. 12, 1092 (2021).

Yesharim, O. et al. Observation of the all-optical Stern-Gerlach effect in nonlinear optics. Nat. Photonics 16, 582–587 (2022).

Liu, G. et al. Electrically engineering synthetic magnetic fields for polarized photons. Optica 11, 980–987 (2024).

Dorn, R., Quabis, S. & Leuchs, G. Sharper focus for a radially polarized light beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 233901 (2003).

Wang, H., Shi, L., Lukyanchuk, B., Sheppard, C. & Chong, C. T. Creation of a needle of longitudinally polarized light in vacuum using binary optics. Nat. Photonics 2, 501–505 (2008).

Marrucci, L., Manzo, C. & Paparo, D. Optical spin-to-orbital angular momentum conversion in inhomogeneous anisotropic media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 163905 (2006).

Chen, G. et al. Advances in lithium niobate photonics: development status and perspectives. Adv. Photonics 4, 034003 (2022).

Jiang, W. et al. Direct observation of the skyrmion Hall effect. Nat. Phys. 13, 162–169 (2017).

Wang, L., Ge, S., Hu, W., Nakajima, M. & Lu, Y. Tunable reflective liquid crystal terahertz waveplates. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 2023–2029 (2017).

Hu, Y. et al. Subwavelength generation of nondiffracting structured light beams. Optica, 7, 1261–1266 (2020).

Gillen, G. D. & Guha, S. Modeling and propagation of near-field diffraction patterns: a more complete approach. Am. J. Phys. 72, 1195–1201 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62175091, Z.L., 12374306, S.F., 12304358, Y.H., and W2441005, S.F.), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2020B090922006, Z.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Fu conceived the concept. S. Fu, X. Zhang, Z. Li, and Z. Chen carried out the analytical considerations. S. Fu, X. Zhang, and Z. Li drafted and revised the paper. X. Zhang, Z. Zeng, S. Zhou, and Y. Hu participated in sample designs and performed the experiments. X. Zhang, G. Liu, and H. Lin performed numerical simulations. Z. Chen, Z. Li, and S. Fu supervised the project. All authors participated in discussions and contributed to the editing of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Hu, Y., Zhou, S. et al. Precise detection of tiny birefringence with accuracy reaching 10−11 level. Nat Commun 16, 6434 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61800-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61800-3