Abstract

Zn-ion batteries with aqueous electrolytes are promising for large-scale energy storage as they are low-cost, environment-friendly and safe. The commercialization of Zn-ion batteries is hindered by several challenges such as the formation of detrimental Zn dendrites. High current density is previously thought to stimulate the dendritic growth of metals such as Li in electrodeposition. However, our study finds that for metallic Zn negative electrode in Zn-ion batteries, high-current deposition results in a dense and flat Zn layer with a (002) texture, which extends the cycling life. Low-current deposition, on the other hand, leads to a porous and dendritic morphology and a short cycling life. Using a synchrotron-based high-throughput in situ X-ray diffraction method we recently developed, Zn deposition under different conditions is systematically investigated, and a texture formation mechanism is proposed. Based on these findings, we suggest guidelines for designing cycling protocols that enable long-lasting Zn-ion batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zn ion batteries (ZIBs) are a promising electrochemical energy storage technology for large-scale energy storage due to the low cost arising from the use of Zn and aqueous electrolytes1,2,3. Yet, the commercialization of ZIBs is still facing several critical challenges, such as low Coulombic efficiency (CE), poor cyclability, and parasitic reactions at both the negative and positive electrodes4,5,6,7,8. The cycling stability of the metallic Zn (or Zn-alloy) negative electrode is a key issue closely related to these challenges. Similar to the well-known Li dendrite problem in Li-ion batteries, Zn dendrites can form during the discharge process due to the non-uniform nucleation of Zn, which can cause a short circuit and significantly shorten the cycle life of ZIBs9,10,11.

Many previous studies have explored different approaches to mitigate the formation of Zn dendrites12,13,14,15,16,17. Recently, our research revealed that the current density for Zn deposition (i.e., the rate of discharge) plays a critical role in determining the morphology of the deposited Zn. Previous studies on Li-ion and Na-ion batteries commonly agree that high-rate metal deposition promotes the formation of dendrites18,19,20,21 and low-rate cycling is generally recommended for long-term cycling. However, our research indicates that this may not be the case for Zn deposition. High-rate deposition leads to a dense deposition layer with a favorable (002) texture and without forming any dendrites, while low-rate deposition produces a porous layer and dendrites.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Zn negative electrodes with different textures can have different cycle lives22,23. A number of previous studies have reported the positive impact of the (002) surfaces on the cycling life of ZIB22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, though with a few reported otherwise37,38. The exposed (002) planes have high corrosion resistance to the aqueous electrolyte and can effectively suppress dendrite formation during long-term cycling24,25. However, the formation mechanism of the textures and the key factors that control and tune the formation of different textures are not fully understood. Although previous reports have demonstrated the dramatic influence of the deposition current density on the formation of the morphology and texture of Zn on different substrates39,40,41,42,43 and on the cycling stability of Zn-ion batteries44, no commonly agreed conclusion has been reached on the underlying mechanism of the formation of the textures of Zn, particularly because of the lack of the experimental support from in situ characterizations. Recently, we developed a novel synchrotron-based high-throughput in situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) platform, with which we successfully uncovered the formation mechanism of the (002) texture of Zn in electrodeposition and the key factors governing this process. These new findings provide opportunities to further improve the cycle life of ZIBs and advance the general knowledge of the deposition of metals and alloys.

Results and discussion

In situ/operando XRD of single cycling batteries has been widely used since the 1990s, while high-throughput in situ XRD tools for batteries are rarely reported. To quickly reveal the relations between the cycling conductions and the morphologies of deposited Zn, we modified our recently-developed in situ XRD platform for electrodeposition45,46 to make it high-throughput. The design of the in situ cell is shown in Fig. 1. The working electrode (WE, which is a metal foil, such as Cu) and counter electrode (CE, which is a Zn strip) are placed in the positions shown in Fig. 1a on the opposite walls inside the cell. With such geometry, when a voltage is applied between the two electrodes, the electric field strength near the surface of the WE at different locations varies as the function of the horizontal distance to the CE in a gradient, as schematically shown by the inset of Fig. 1b. Therefore, in an electrodeposition experiment of metals/alloys, e.g., Zn, the local deposition current density at different locations on the WE (i.e., the substrate) also varies as a continuous gradient function of the distance, which would result in a gradient thickness for single metals and/or different phases/compositions for alloys. This voltage gradient and thus the current density gradient can be modeled with an analytic model, as shown in Fig. 1b and elaborated in Methods. The local current densities and areal capacities at P1–P8 are summarized in Table S1 in supporting information (SI). Mounting this in situ cell at a synchrotron beamline and taking advantage of high-intensity synchrotron X-ray, high-quality XRD data can be collected in transmission mode by scanning the substrate horizontally with very fine temporal (1–30 s per XRD scan) and spatial (a few tens of micrometers to millimeters) steps in real time. With just one experiment, XRD patterns of the deposited metals or alloys can be collected for a large number of different current densities (at different locations on the WE). In this work, we selected eight spots on the WE (P1, P2, … P8 shown in Fig.1 b) to investigate Zn deposition under current densities from ~0.1 to ~100 mA/cm2. This approach can be extended to hundreds of spots, if necessary. With this tool, we can in real time qualitatively and quantitatively characterize the nucleation, growth and ripening processes in electrodeposition, as well as the dissolution of the metal/alloy phases in electrochemical stripping/dealloying processes for a wide range of metals and alloys, not limited to Zn.

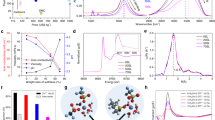

a Schematic of the in situ cell to realize gradient current density distribution on the substrate/working electrode (WE). Zinc or Pt are used as counter electrode (CE). b Red curve: modeled current density distribution on the substrate/working electrode. Black spots: selected positions where in situ XRD patterns are collected during the deposition experiments. c In situ XRD patterns and d the corresponding integrated peak area of 002 and 100 reflections in the in situ XRD patterns of Zn deposited at selected spots on the Cu substrate with an electrolyte consisting of 1 M ZnSO4 and 0.5 M Na2SO4, under an average current density of 10 mA/cm2. XRD patterns are collected with a wavelength of 0.24085 Å in transmission mode and plotted in d-spacing. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

High-throughput in situ XRD analysis of Zn deposition was conducted using a nominal/average current density of 10 mA/cm2 (calculated based on the total surface area of the WE) in a galvanostatic mode to deposit Zn on a 0.5 × 4 mm rectangular Cu foil. XRD patterns were collected from P1 to P8 shown in Fig. 1b in turns with each XRD scan taking 30 s. The full in situ XRD patterns are shown in Fig. S1 in the SI and a selected range is shown in Fig. 1c. The amount of deposited Zn can be quantified by integrating the area of the Bragg reflections. The quantification protocol is shown in Fig. S2. The quantification of the 002 and 100 reflections in Fig. 1c is shown in Fig. 1d. Quantification results of more Bragg reflections are shown in Fig. S3. It can be seen that the intensity of different hkl reflections all vary as a linear function of deposition time, which agrees well with the galvanostatic deposition condition. The slopes of the same (hkl) at different locations are different, with the slope of P1 being the maximum and a gradient decay showing from P1 to P8. This indicates the gradient-distributed growth rate of Zn and the gradient-distributed local current density, as expected.

The last pattern of each in situ XRD series of P1 through P8 is shown in Fig. 2a. Interestingly, Zn deposited at P1 shows a pronounced low reflection intensity ratio of I(002)/I(100), very different from that of the PDF database entry shown at the bottom of Fig. 2a, indicating a strong texture with the (002) planes being parallel to the substrate (Note that the synchrotron XRD data is collected in a transmission mode, thus the rules of reflection intensity enhancing/depressing for textured samples are the opposite to XRD data collected from lab XRD in a reflection mode, as shown in Fig. S4a, b). Such texture gradually decreases from P1 to P8 as the local current density decreases. To verify the texture, secondary electron scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the same sample at P1 through P8 spots were taken and the top-view images of P2, P4 and P7 are shown in Fig. 2b–d, respectively. Consistent with the XRD, Zn deposited at P2 with a high current density of ~60 mA/cm2 (estimated from the model) shows a very dense deposition layer and the characteristic hexagon shape of the particles indicates the top surfaces are the (002) facets, which are parallel to the substrate. The Zn deposited at P4 ( ~ 28 mA/cm2) with lower current density also shows a dense deposition with large particles in a hexagonal shape. Most of the hexagonal plates are not completely parallel to the substrate, forming small angles with the substrate, which agrees with the weaker (002) texture seen in the XRD pattern of P4 compared to P2. For P7, as the local current density is even lower ( ~ 2.6 mA/cm2), the deposited Zn shows a very porous dendritic morphology with no preferred orientation that can be visually identified, which also agrees well with its XRD pattern where no texture is shown. At higher current densities, the Zn deposits form a more aligned and dense structure. As the current density decreases, as shown in Fig. S5, the deposits become increasingly disordered and porous, forming the highly dendritic and mossy morphology.

a The last patterns of the in situ XRD patterns of Zn deposited at selected spots (P1 to P8) on the Cu substrate, with electrolyte consisting of 1 M ZnSO4 and 0.5 M Na2SO4, under an average current density of 10 mA/cm2. (b–d) SEM images of deposited Zn at P2, P4, and P7 spots, respectively. XRD patterns are collected with a wavelength of 0.24085 Å in transmission mode and plotted in d-spacing. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

From the above high-throughput in situ XRD results, it can be seen that the formation of the (002) texture strongly depends on the deposition current density, with the higher current density better promoting the formation of the texture. To verify this trend, we conducted deposition experiments using a conventional setup (shown in Fig. S6) that we previously developed45,46, where the two electrodes with identical square shapes are placed in directly opposite positions and a constant current density is applied. The XRD results are displayed in Fig. S4 and the same current-texture dependence was observed.

To further evaluate how general this current-texture dependence may be, we conducted a variety of experiments employing different substrates and electrolyte concentrations, leveraging the powerful high-throughput capability of our in situ XRD tool. The last XRD patterns of the in situ XRD series of Zn deposited at P1 through P8 spots on a Ti foil substrate and a stainless-steel foil substrate are shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. Similarly, Zn deposited on Ti and stainless-steel substrates also yields stronger (002) textures under higher current densities than lower ones. The results show that within the substrates that we investigated, this current-texture dependence seems to be general.

a and b The last patterns of the in situ XRD pattern series of Zn deposited on a Ti and b stainless-steel (SS) substrates, with the same electrolyte of 1 M ZnSO4, 0.5 M Na2SO4 and the same average current density of 10 mA/cm2. c and d The last patterns of the in situ XRD pattern series of Zn deposited with c) 2 M ZnSO4, and d) 0.5 M ZnSO4, and the same 0.5 M Na2SO4 additive at the same average current density of 10 mA/cm2 on Cu substrates. XRD patterns are collected in transmission mode with a wavelength of a 0.187, b 0.1818, c and d 0.24085 Å, respectively, and plotted in d-spacing. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figures 3c and d show the last XRD patterns of Zn deposited at P1 through P8 taken from experiments with 2 and 0.5 M ZnSO4 concentrations of the electrolyte, respectively. The average current density was kept the same at 10 mA/cm2. Comparing the I(002)/I(100) ratios at P1 through P8 in the conditions with 2 M (Figs. 3c), 1 M (Fig. 1a), and 0.5 M (Fig. 3d) ZnSO4, it can be seen that the lower concentration better promotes the formation of the (002) texture than the higher concentration under the same current density. These results imply that the formation of the texture is closely related to the reaction kinetics, which inspired our investigation of the formation mechanism. The full in situ XRD patterns of different substrate and electrolyte concentrations are shown in Figs. S7–S10 in the SI.

The in situ XRD patterns for the deposition experiment using an electrolyte without Na2SO4 additive are shown in Fig. S11 and Fig. S12 in the Supplementary Information, respectively. Ex situ XRD results of Zn deposited using Cu substrates with different textures (no texture and (220) texture) are shown in Fig. S13 in the Supplementary Information. Together with the observations presented in Fig. S1 and Fig. 3, it can be seen that although the additives (e.g., Na2SO4), texture and type of the substrate, and type and concentration of the electrolytes can have some impacts on the significance of the texture formed under the same current density, overall, the dominant impact of the current density on the formation of the (002) texture is generally observed.

To further reveal the formation mechanism of Zn texture, we designed and conducted a series of systematic in situ XRD experiments and we established a protocol to quantitatively characterize the texture evolution. Based on the common definition of the texture coefficient and relative texture coefficient (RTC) used in literature to reflect the texture composition of selected (hkl) crystal planes47,48,49, we calculated the RTC values of the XRD patterns. The RTC is defined by the following equation:

where I(hkl) is the integrated peak area of the experimentally observed Bragg reflection hkl, and I0(hkl) is the intensity of simulated Bragg reflection hkl for a powdered sample assuming no texture.

In situ XRD patterns and SEM images of Zn electrodeposition using the conventional setup under current densities of 10 and 60 mA/cm2 are shown in Fig. 4a and c, respectively. Very high temporal resolution for in situ XRD data collection is used for the 60 mA/cm2 experiment with each scan taking only 2 s to capture the early nucleation stage. The corresponding integrated peak area is shown in Fig. S14. RTC values of each XRD pattern were calculated using Eq. (1) and following the protocol shown in Fig. S2. RTC values of the data in Fig. 4a, c are plotted as the functions of deposition time in Fig. 4b, d, respectively. Note that an RTC value of 1 means the sample has no texture by definition. For synchrotron XRD data obtained in transmission mode, an RTC value below 1 for a particular Bragg reflection hkl means the sample has a preferred orientation/texture with the (hkl) planes parallel to the substrate, and a value above 1 indicates a texture of (hkl) planes perpendicular to the substrate. Ex situ SEM images were also taken for both samples at selected times/stages while keeping the deposition capacity the same for both samples for the purpose of comparison, shown in Fig. 4e, f.

a Selected in situ XRD patterns, b corresponding relative texture coefficients (RTCs) of Zn deposited under 10 mA/cm2 and c and d under 60 mA/cm2. e Cross-section SEM image and g top view SEM images of Zn deposited under 60 mA/cm2 and f and h under 10 mA/cm2. The electrolyte consists of 1 M ZnSO4 and 0.5 M Na2SO4. Cu is used as a substrate. Both cross-section Zn samples have an areal capacity of 10 mAh/cm2. In situ synchrotron XRD patterns are collected with a wavelength of 0.182 Å in transmission mode and plotted in d-spacing. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In Fig. 4b and d, it can be seen that at the initial stage, both samples deposited under 10 and 60 mA/cm2 show small RTC values (~0.5) of the 002 reflection and high RTC values (~1.2) of reflection 100, which collectively indicate a slight texture with the (002) planes parallel to the substrate. Cross-checking the SEM images in Fig. 4e and f, this is because the Zn nuclei are in a hexagonal plate shape, and they tend to lie flat on the substrate. After the initial stage, however, Zn deposited under different current densities show distinctively different texture evolutions. Under 10 mA/cm2, the RTC values of all plotted hkl reflections quickly converge to 1 with time, clearly indicating a random orientation. While under 60 mA/cm2, the RTC values of (002) drastically drop to small values close to 0, while the RTC values of (100) increase to ~1.75, which collectively indicates a very strong texture with (002) parallel to the substrate. In situ XRD patterns of Zn deposition under 10 and 60 mA/cm2 at a d-spacing range of 12–11 Å are shown in Fig. S15. At 10 mA/cm2, after ~1 h of deposition, a weak Bragg reflection around 11 Å is observed, which may be attributed to the 001 reflection of Zn4SO4(OH)6·5H2O (ZSH). For Zn plating under 60 mA/cm2, no signal of ZSH is observed after 20 minutes of deposition.

The different texture evolutions at 10 and 60 mA/cm2 are further confirmed by the SEM images in Fig. 4e, f. Under 60 mA/cm2, as time goes on, besides that the particle size becomes bigger, as expected, more and more hexagonal plate-shaped Zn particles are seen with their hexagons (i.e., the (002) facets) parallel to the substrate, consistent with the stronger and stronger (002) texture observed in XRD. The deposition layer is densely packed as shown in the cross-section image in Fig. 4g. While for Zn deposited under 10 mA/cm2, the orientations of the particles are visually random, and dendrites start to grow after 30 min. These Zn dendrites continue to grow and eventually form a very porous and dendritic layer, confirmed by the cross-sectional image in Fig. 4h. We also conducted in situ XRD for current densities 20 and 40 mA/cm2. The XRD patterns, integrated peak areas and calculated RTCs are shown in Fig. S16. Bringing together the results from 10, 20, 40, and 60 mA/cm2, it can be seen that under higher current density, the drop of the (002) RTC value occurred sooner than under lower current density, which again confirms the current-texture dependence aforementioned. A side-by-side comparison of in situ XRD data from gradient cells and conventional cells with similar current densities is shown in Fig. S17. The RTCs of both the gradient cells (indicated by solid dots) and conventional cells (represented by hollow dots) follow a very similar trend, confirming that the morphology-current relationship observed in the gradient cells is well supported and validated by the conventional cell experiments.

More interestingly, the quantitative characterization of the texture evolution reveals fundamental insights into the formation mechanism of the (002) texture. Very recently, similar current-texture dependence was reported independently by two groups39,50. Both groups explained the formation of the texture with the different preferred nucleation shapes of Zn under different current densities driven by the different affinity of different (hkl) facets to the substrate, and by the much faster growth rate along the <100> and <110> directions than that along the <001> direction. However, the results of current in situ XRD experiments clearly indicate that the current-texture dependence appears in a variety of substrate types. It is unlikely the substrate is the most critical factor. Meanwhile, results in Fig. 4e, f also show that the texture feature in the nucleation stage is very similar under high and low current densities, which means the formation of the texture is not determined at the nucleation stage, but rather, at the growth stage.

Based on the in situ XRD results, we attribute the current-texture dependence to an evolutionary orientation selection mechanism51, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 5a. The evolutionary orientation selection process can be viewed in three stages: initial stage, transition stage and final stage. Here, the initial stage differs from the conventionally defined nucleation stage. Instead, it refers to the point at which the deposited Zn substantially covers the substrate surface, such that subsequent Zn deposition occurs exclusively on top of the existing Zn layer rather than directly on the substrate. In the initial stage, (near) randomly oriented nuclei form simultaneously in hexagonal plate shapes, as shown in Fig. 4e, f. It has been revealed by previous computational studies that the fast-growth directions of the plate-like Zn particle are <100> and <110> directions (i.e., the directions of 2D-expansion of the hexagonal plate), while the slow-growth direction is the <001> direction (i.e., the thickening direction of the hexagonal plate), dictated by the lower binding energy of Zn atoms on Zn (100) facet (−0.86 eV) than (001) facet (−0.68 eV)16 This difference in growth rates along the ab-plane and c-axis is common for materials with hcp lattices52, which implies that the rate of the hexagonal plates growing bigger is faster than them growing thicker. It is not a problem for the plates with relatively small angles to the substrate to grow bigger, as schematically shown in Fig. S18. While for the plates having large angles to the substrate, the growth toward the substrate is impeded. Some plates, if not heavily blocked, may gradually pivot to a smaller angle with the substrate so as to have the chance to expand and grow into bigger plates. Some, if their angles with the substrate are too large or they are blocked from pivoting, have to grow asymmetrically to form a trapezial or triangular shape, self-terminate the growth (Fig. S18c), and quickly get buried by other fast-expanding plates parallel to the substrate. This selection is more effective when the current density is high, i.e., the rate of the expansion of the parallel plates is fast. In contrast, when the current density is low and the expansion of the parallel plates is relatively slow, there are more chances for the vertical plates not being buried. It would form statistically randomly orientated plates. Figure 5a demonstrates the orientation selection and texture enhancement for the high current case. An electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) experiment was conducted for a Zn sample deposited under 60 mA/cm2 for 20 minutes. The pole figure (Fig. 5b) shows that the regions with high texture intensity are mostly located close to the north and south poles, suggesting that the <001 > / < 00\(\bar{1}\,\)> directions of most grains are closely aligned with the normal direction of the substrate. The inverse pole figure map (Fig. 5c) clearly shows that the particles close to the substrate have smaller sizes and more random orientations, and the particles on the top have bigger sizes and more uniform orientations with their <001> directions normal to the Cu substrate. These results clearly show the random-orientated particles get buried by the textured particles and strongly support the evolutionary orientation selection mechanism we proposed. Cross-verification of the ex situ EBSD and in situ RTC data of Zn samples deposited under 10 mA/cm2 and 60 mA/cm2 are shown in Fig. S19.

a Schematic of texture formation mechanism under high current densities. b Pole figure showing the texture of the cross-section. The texture intensity is scaled with the color legend. c Image quality map (IQM) from an EBSD scan showing the grain structure of a cross-section from a Zn film deposited under 60 mA/cm2 for 20 min (the Cu substrate is the dark region at the bottom), and corresponding inverse pole figure (IPF) map of the same area showing the crystallographic orientations of different grains. The sample normal direction (ND) in the IPF is chosen to be pointing upwards as labeled by the black arrow. As a result, grains with their <001> directions aligned (or approximately aligned) with the ND are colored reddish, as shown in the legend on the right. d–h RTCs of Zn plating under different plating protocols. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In this evolutionary orientation selection process, the final texture of Zn is majorly determined in the transition stage, while the morphology and texture of the initial/nucleation stage are not that important. To further verify this mechanism, we conducted more experiments. In one experiment, we first deposited Zn at 60 mA/cm2 for a short time of 10 s to form the nuclei, then switched to 10 mA/cm2 for 50 min to allow the Zn to grow. The RTC values gradually converge to 1, as shown in Fig. 5d, indicating a sample with no preferred orientation at the end. In the second experiment, we started the deposition with 10 mA/cm2 current for 1 min for nucleation and then switched to 60 mA/cm2 for 30 minutes (Fig. 5e). The evolution of the RTC is very much like what is shown in Fig. 4d, where 60 mA/cm2 current density was used throughout, indicating that no matter what current is used during the nucleation stage, as long as a high current is applied onward, a (002) texture will form. These results confirm that the initial/nucleation stage is not critical while the current in the transition stage matters.

However, if we keep the initial current density for too long, e.g., starting with 60 mA/cm2 for 5 min then switching to 10 mA/cm2 for 30 min, or starting with 10 mA/cm2 for 20 min then switching to 60 mA/cm2 for 40 min, the final yielded samples keep the texture feature formed under the initial currents, as shown in Fig. 5f, g, respectively. In these two cases, the amount of Zn deposited under the initial low (or high) current has passed the transition stage and in the following deposition, it is just the further growth of the existing texture. The corresponding in situ XRD patterns of Fig. 5d–h are shown in SI as Figs. S20–24.

These results are very intriguing for establishing optimized cycling protocols for ZIBs. For instance, the results in Fig. 5f indicate that with a thick enough (002)-textured layer of Zn already formed under the initial high current, subsequent deposition of Zn can be continued under much lower current densities without losing the favorable texture features This enables the formation of the desired (002) texture without the constant application of high current. In contrast, it would be detrimental to the cycling life if low current is used for a sufficiently long time, as this condition would yield random orientations that persist through the deposition process. Yet, it is worth noting that the random-oriented sample formed under low current can be corrected back to (002)-textured, by applying a much higher current density (e.g., 100 mA/cm2), as demonstrated in Fig. 5h. However, such high current conditions may not be practical for the cycling of ZIBs. Suggested guidelines for designing the cycling protocols for long-lasting ZIBs can thus be summarized as follows:

-

1.

A fresh ZIB should start discharging (i.e., Zn deposition) with a sufficiently large current for a reasonably long time (over the transition stage) to form a (002)-textured surface. After establishing an (002)-textured surface, currents can be applied as needed.

-

2.

Low current discharging is to be avoided unless a (002)-textured surface is already formed.

-

3.

If a ZIB has been cycled under low current for a while (i.e., a porous/dendritic surface is already formed) the cycling life can be extended by applying deep cycling with high current.

To verify the different electrochemical performances of Zn with different textures, Cu | |Zn half cells were assembled and tested at different cycling current densities and different areal capacities. Under different cycling current densities, different Zn textures and morphologies are formed and in turn, result in different cell cycling life. For half cells cycling at a high current density of 60 mA/cm2, a flat and dense layer of Zn with a strong (002) texture is formed. Similar to the results reported previously, the (002) texture surface is beneficial for the cycling life24,25,40. For cells cycled under 10 mA/cm2, a dendritic random oriented Zn layer is formed, which significantly increases the possibility of short-circuiting of the cell. In Fig. 6a, when cycled with 1 mAh/cm2 areal capacity, the half-cell cycled at 10 mA/cm2 failed after ~220 cycles, likely due to loss of Zn caused by the low CE associated with mossy morphology under low current density. The half-cell cycled at 60 mA/cm2 delivers a much longer cycle life of more than 400 cycles. The zoom-in voltage profiles from 70-80 cycles are shown in Fig. 6b. In Fig. 6c, with a higher cycling areal capacity of 5 mAh/cm2, half-cells cycled at 60 mA/cm2 demonstrate stable cycling for ~150 cycles. Cells cycled under 10 mA/cm2 failed after only ~20 cycles. The CE of half-cells cycled under different current densities are plotted in Fig. 6d, further demonstrating that more stable cycling performance is achieved under 60 mA/cm2 than 10 mA/cm2, attributed to the formation of the dense (002)-textured Zn under this high current density. Additional cycling tests (as shown in Fig. 6e) were performed using two cells with identical Cu electrode surfaces, both pre-deposited with Zn of 10 mAh/cm² under a current density of 60 mA/cm². One cell was cycled continuously at 10 mAh/cm² and failed after ~300 cycles. In contrast, the other cell was cycled in intervals: 40 cycles at 10 mAh/cm² followed by 10 cycles at 60 mAh/cm². This cycling protocol with periodic surface refreshing by the high-current cycling resulted in a significantly longer cycle life of over 500 cycles, demonstrating the beneficial effect suggested by the third cycling protocol guideline outlined above.

Voltage profiles of half-cells cycled under 10 and 60 mA/cm2 with areal capacities of (a) 1 mAh/cm2 (before cycling, 5 mAh /cm2 of Zn are plated on Cu substrate under 10 and 60 mA/cm2, respectively) and c 5 mAh/cm2 (before cycling, 25 mAh /cm2 of Zn are plated on Cu substrate under 10 and 60 mA/cm2, respectively). b The detailed voltage profiles from 70 to 80 cycles in (a). d The Coulombic efficiency (CE) of half cells cycling under 10 and 60 mA/cm2. e Cycling performances of Cu | |Zn half-cells cycled under cycled continuously under 10 mA/cm2 (bottom plot) and 10 mA/cm2 for 40 cycles and 60 mA/cm2 for 10 cycles and then repeated in sequence (top plot). Both are cycled with an areal capacity of 2 mAh/cm². Prior to cycling, a Zn layer of 10 mAh/cm² was plated onto the Cu substrate at a current density of 60 mA/cm². f Zoom-in plots for detailed voltage profile are plotted in (e). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In summary, the current-texture dependence of Zn formed in electrodeposition under different current densities is revealed and systematically investigated using the high-throughput in situ XRD tool. High current densities lead to the formation of the (002) texture that benefits the cycling life of the ZIBs. This current-texture dependence can be explained by an evolutionary orientation selection mechanism. These findings provide fundamental insights into the cycling of ZIBs and offer guidelines for designing the cycling protocols.

Methods

Electrodeposition of Zn

Zn samples with different textures were electrodeposited at different current densities. The electrodeposition process was conducted using a LANHE or a BioLogic potentiostat with a two-electrode system. During deposition, commercial Zn foil (Thermo Scientific, ≥99.98%, thickness 0.25 mm) was used as the reference/counter electrode. Commercial Cu foil (1 × 1 cm) was used as the substrate and the working electrode, with the backside covered with Kapton tape. In this work, all samples deposited on Cu substrates were prepared using as-received commercial 12 μm Cu foil (MTI Corp. ≥99.8%), which has a slight (220) texture, except for one experiment which employed a 6 μm Cu substrate (MTI Corp. ≥99.8%) shown in Fig. S13a (red line), which has no texture (random orientation). Other substrates of Ti (Thermo Scientific, type 304, thickness 0.025 mm) and stainless steel (Thermos Scientific, ≥99.7%, thickness 0.032 mm) were also used to study the influence of different substrates on Zn texture formation. Before electrodeposition, Cu substrates were immersed into 0.05 M HCl for 20 s and then rinsed with distilled water and ethanol to remove the oxide layer on the surface. Ti and stainless steel substrates were sonicated in 0.05 M HCl for 10 min and then in ethanol for 10 min to remove the surface contamination and oxide layer. The electrolyte consisted of 1 M ZnSO4 (99.0–103.0% ACS, Alfa Aesar) and 0.5 M Na2SO4 (Alfa Aesar, 99.0%). To investigate the influence of electrolyte concentration on Zn texture formation, 0.5 and 2 M ZnSO4 with 0.5 M Na2SO4 were also used as electrolytes.

EBSD experiments and data analysis

The sample foil (Zn deposited on Cu) was mounted in epoxy and ground using SiC paper from 800 to 4000 grit. Polishing of the sample was conducted using diamond suspensions from 6 to 1 microns, followed by chemical-mechanical polishing using alcohol based colloidal silica. The EBSD data were acquired using a Velocity electron detector installed inside a TESCAN MIRA scanning electron microscope. EBSD scan was analyzed using EDAX OIM Analysis program.

XRD and SEM characterization

The morphology and microstructure of electrodeposited Zn were studied using high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi SU8230). For SEM sample preparation, the electrodeposition solution was purged with argon to eliminate dissolved oxygen, preventing the formation of any Zn salt byproducts and allowing for clearer observation of the Zn sample morphology. The electrodeposited Zn film on a Cu substrate was then directly mounted on the sample holder using conductive carbon tape. Ex situ and in situ XRD patterns were collected to investigate the phase and texture information of the electrodeposited Zn samples. Ex situ XRD measurements were conducted using an X-Pert Pro Alpha-1 diffractometer equipped with a copper radiation source (λ Kα1 = 1.5406 Å) and a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with a Mo source (λ Kα1 = 0.7093 Å). For ex situ XRD sample preparation, electrodeposited Zn samples were mounted with their edges taped to the holder, ensuring that the film remained flat and fully adherent. This prevented any shifts or detachment during analysis. For in situ XRD data collection, a 0.5 mm diameter hole was drilled in the Zn counter electrode to allow X-rays to pass through without collecting any signals from the Zn CE. In situ synchrotron XRD data were collected at beamline 28-ID-2 at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) at Brookhaven National Laboratory and beamline 17-BM-B at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory.

Cell cycling

To study the Zn plating/stripping behavior under different current densities, half cells with commercial Zn foil and Cu electrodes (1 × 1 cm2) were assembled using the same electrodeposition in situ cell and tested under different current densities with the same areal capacity. Zn plating/stripping behavior was tested using the conventional in situ cell with ~3 mL electrolyte, without seperators, at different current densities and with commercial Zn foil and Cu (1 × 1 cm2) as the two electrodes.

CE tests with different areal capacity were conducted with first plating different amounts of Zn onto Cu substrate, and then stripping Zn until 0.5 V. Before cycling, all cells were first activated under 0.1 mA current between 0 to 1 V to remove surface contamination and stabilize the Cu surface. During electrochemical cycling tests, the cells are sealed with Parafilm to prevent the evaporation of the solvent. The electrolyte was the same as used in the electrodeposition process, consisting of 1 M ZnSO4 and 0.5 M Na2SO4. Cells are tested with using a LANHE battery cycler or an Arbin cycler, depending on the applied cycling current density. All reactions and measurements were conducted at 25 °C.

XRD Data analysis (in situ XRD patterns Bragg reflection fitting and integration)

The XRD data were obtained with an area detector and reduced to one dimensional patterns by GSAS-II53. Different hkl reflections of the XRD patterns were fit to pseudo-Voigt functions to obtain integrated intensities using LmFit Python libraries54. The integrated reflection intensities were then used to calculate RTCs of different hkl reflections. Data analysis code for reflection intensity and RTCs calculation can be found on GitHub (https://github.com/yifan36/Zn-XRD-quantification-.git).

Numerical modeling of current density distribution

The current density distribution for gradient electrodeposited samples was determined using a simplified analytical model for the primary current distribution. Assuming negligible kinetic resistance, the current density distribution is determined from the electric field distribution by applying Ohm’s Law:

Because the electrodeposition setup is symmetric along the center of the electrodes in the direction of the current density gradient, the problem can be simplified to two dimensions based on Laplace’s equation. To numerically model the 2-D electric field distribution, the working electrode and counter electrode are discretized into finite elements Pi for the counter electrode and Qk for the working electrode. Each element of the counter electrode is treated as a point source. The relative contribution of electric field strength by each point source at a given element of the working electrode is given by Coulomb’s Law (2), where ri,j is the distance between elements Pi and Qk, and the total relative electric field strength at each WE element is given by equation (3), where A is a proportionality constant:

By applying (1), it follows that E/Eavg = j/javg. Therefore, normalizing the calculated values of E reveals the shape of the current density distribution. Because the gradient electrodeposition experiments are performed galvanostatically, javg is known and the value of the proportionality constant can be determined by applying the condition of average current density:

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper. The code for the reflection intensity and RTCs calculation can be found on GitHub (https://github.com/yifan36/Zn-XRD-quantification-.git). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Blanc, L. E., Kundu, D. & Nazar, L. F. Scientific challenges for the implementation of Zn-ion batteries. Joule 4, 771–799 (2020).

Kundu, D. et al. A high-capacity and long-life aqueous rechargeable zinc battery using a metal oxide intercalation cathode. Nat. Energy 1, 16119 (2016).

Xu, C. J. et al. Energetic zinc ion chemistry: the rechargeable zinc ion battery. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 51, 933–935 (2012).

Parker, J. F. et al. Rechargeable nickel-3D zinc batteries: an energy-dense, safer alternative to lithium-ion. Science 356, 414–417 (2017).

Li, H. F. et al. Advanced rechargeable zinc-based batteries: recent progress and future perspectives. Nano Energy 62, 550–587 (2019).

Tang, B. Y. et al. Issues and opportunities facing aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 3288–3304 (2019).

Song, M. et al. Recent advances in Zn-Ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802564 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. ZnCl2 “Water-in-Salt” electrolyte transforms the performance of vanadium oxide as a Zn battery cathode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1902653 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. A metal-organic framework host for highly reversible dendrite-free zinc metal anodes. Joule 3, 1289–1300 (2019).

Zhao, Z. M. et al. Long-life and deeply rechargeable aqueous Zn anodes enabled by a multifunctional brightener-inspired interphase. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1938–1949 (2019).

Du, W. C. et al. Challenges in the material and structural design of zinc anode towards high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 3330–3360 (2020).

Liang, G. J. & Zhi, C. Y. A reversible Zn-metal battery. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 854–855 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Calendar life of Zn batteries based on Zn anode with Zn powder/current collector structure. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003931 (2021).

Liang, P. C. et al. Highly reversible Zn anode enabled by controllable formation of nucleation sites for Zn-based batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908528 (2020).

Hao, J. N. et al. Deeply understanding the Zn anode behaviour and corresponding improvement strategies in different aqueous Zn-based batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 3917–3949 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Revealing the role of crystal orientation of protective layers for stable zinc anode. Nat. Commun. 11, 3961 (2020).

He, P. & J. X. Huang, Chemical passivation stabilizes Zn anode. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109872 (2022).

Fan, L. et al. Stable lithium electrodeposition at ultra-high current densities enabled by 3D PMF/Li composite anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1703360 (2018).

Zhang, R. et al. Conductive nanostructured scaffolds render low local current density to inhibit lithium dendrite growth. Adv. Mater. 28, 2155–2162 (2016).

Orsini, F. et al. In situ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation of interfaces within plastic lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 76, 19–29 (1998).

Li, C. F. et al. Two-dimensional molecular brush-functionalized porous bilayer composite separators toward ultrastable high-current density lithium metal anodes. Nat. Commun. 10, 1363 (2019).

Zheng, J. et al. Textured electrodes: manipulating built-in crystallographic heterogeneity of metal electrodes via severe plastic deformation. Adv. Mater. 34, e2106867 (2022).

Zhou, M. et al. Surface-preferred crystal plane for a stable and reversible zinc anode. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100187 (2021).

Zhang, X. T. et al. An ion-sieving Janus separator toward planar electrodeposition for deeply rechargeable Zn-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2205175 (2022).

Hao, Y. et al. Gel electrolyte constructing Zn (002) deposition crystal plane toward highly stable Zn anode. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104832 (2022).

Zheng, J. X. et al. Reversible epitaxial electrodeposition of metals in battery anodes. Science 366, 645 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Converting commercial Zn foils into single (002)-textured Zn with millimeter-sized grains for highly reversible aqueous zinc batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202401507 (2024).

Cheng, Y., Jiao, Y. & Wu, P. Manipulating Zn 002 deposition plane with zirconium ion crosslinked hydrogel electrolyte toward dendrite free Zn metal anodes. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 4561–4571 (2023).

Feng, J. et al. Periodically alternating electric field layers induces the preferential growth of Zn (002) plane for ultralow overpotential zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2204092 (2023).

Huang, Z. et al. Regulating Zn(002) deposition toward long cycle life for Zn metal batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 372–380 (2022).

Lin, Y. et al. Interfacial regulation via anionic surfactant electrolyte additive promotes stable (002)-textured zinc anodes at high depth of discharge. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301999 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Hydrophobic ion barrier-enabled ultradurable Zn (002) plane orientation towards long-life anode-less Zn batteries. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, 07639 (2024).

Lv, B. et al. Assembly of metal–organic chemical conversion layers as ion sieves along with exposing Zn(002) planes for stable Zn metal anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2316535 (2024).

Wei, T. et al. Building near-unity stacked (002) texture for high-stable zinc anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312506 (2023).

Xi, M. et al. Shear-flow induced alignment of graphene enables the closest packing crystallography of the (002) textured zinc metal anode with high reversibility. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 3168–3178 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Inducing the preferential growth of Zn (002) plane for long cycle aqueous zn-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2203254 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Construct robust epitaxial growth of (101) textured zinc metal anode for long life and high capacity in mild aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, e2305988 (2024).

Xu, D. et al. Selectively etching-off the highly reactive (002) Zn facet enables highly efficient aqueous zinc-metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 642–654 (2024).

Yuan, W. et al. Realizing textured zinc metal anodes through regulating electrodeposition current for aqueous zinc batteries. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 62, e202218386 (2023).

Pu, S. D. D. et al. Achieving ultrahigh-rate planar and dendrite-free zinc electroplating for aqueous zinc battery anodes. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202552 (2022).

Cui, Y. F. et al. A dendrite-free and anticaustic Zn anode enabled by high current-induced reconstruction of the electrical double layer. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 59, 2437–2440 (2023).

Cai, Z. et al. Ultrafast metal electrodeposition revealed by in situ optical imaging and theoretical modeling towards fast-charging Zn battery chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 61, e202116560 (2022).

Hao, Z. et al. Metal anodes with ultrahigh reversibility enabled by the closest packing crystallography for sustainable batteries. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209985 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Tailoring the metal electrode morphology via electrochemical protocol optimization for long-lasting aqueous zinc batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 3699 (2022).

Ma, X. T. et al. Understanding the polymorphism of cobalt nanoparticles formed in electrodeposition- an in situ XRD study. Acs Mater. Lett. 5, 979–984 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. Electrochemically dealloyed 3D porous copper nanostructure as anode current collector of li-metal batteries. Small 19, 2301730 (2019).

Nasirpouri, F. et al. An investigation on the effect of surface morphology and crystalline texture on corrosion behavior, structural and magnetic properties of electrodeposited nanocrystalline nickel films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 292, 795–805 (2014).

Ruppi, S. Deposition, microstructure and properties of texture-controlled CVD α-Al2O3 coatings. Int. J. Refractory Met. Hard Mater. 23, 306–316 (2005).

Zhang, X. et al. Single [0001]-oriented zinc metal anode enables sustainable zinc batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 2735 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Nonepitaxial electrodeposition of (002)-textured Zn anode on textureless substrates for dendrite-free and hydrogen evolution-suppressed Zn batteries. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300073 (2023).

Vanderdrift, A., Evolutionary selection a principle governing growth orientation in vapour-deposited layers. Philips Res. Rep. 22, 267 (1967).

Chen, H. et al. LiCoO2 concaved cuboctahedrons from symmetry-controlled topological reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 262–270 (2011).

Toby, B. H. & Von Dreele, R. B. GSAS-II: the genesis of a modern open-source all purpose crystallography software package. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 46, 544–549 (2013).

Geise, N. R. et al. Quantification of efficiency in lithium metal negative electrodes via operando x-ray diffraction. Chem. Mater. 33, 7537–7545 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is in part financially supported by Novelis Inc. through Novelis-Georgia Tech Research Hub. This work is also in part financially supported by the U.S. NSF project 2004878 and the internal fund of Georgia Institute of Technology. YS and JK acknowledge the support from the U.S. NSF project 2043264. The authors thank beamline scientists at 28-ID-2 of the NSLS II, 17-BM of the APS for technical assistance of data collection. This research used resources of the NSLS II, APS, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facilities operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DESC0012704, and by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC0206CH11357. Y. M. would also like to thank Timothy S. Chen and Salem Clay Wright for their assistance with the EBSD sample preparation exploration, even though the data was not ultimately used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C. conceived the idea. H.C. and Y.M. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Y.M., G.Z., and J.P conducted electrodeposition and in situ XRD experiments. J.P. modeled current and potential of the gradient cell. Y.M. and H.C. analyzed the data. Z.L. contributed to the growth mechanism. J.B., W.X., H.Z., and T.L. helped with synchrotron data collection. Y.S. and J.K. conducted EBSD characterization and analyzed data. M.K. and J.C. contributed helpful discussion and edits of the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, Y., Pepas, J., Zhang, G. et al. Understanding rate-dependent textured growth in zinc electrodeposition via high-throughput in situ x-ray diffraction. Nat Commun 16, 7448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61813-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61813-y