Abstract

The Eulipotyphla (true insectivores) is the third largest mammalian order, comprising over 500 species, and could be an important source of human infectious diseases. However, relatively little is known about the microbial diversity in insectivores and their contribution to virus transmission among wild hosts. In this study, we compile a comprehensive dataset containing over 400,000 records of insectivores and their associated microbes from 1903 to 2023 from multiple public databases. Meta-analyses show that insectivores host 941 unique microbes, 60% of which are viruses; these are predominantly found in shrews and hedgehogs. Human-associated viruses harbored by shrews and hedgehogs are phylogenetically closely related to those in humans, suggesting potential bidirectional transmission between insectivores and humans. Moreover, virus-sharing networks reveal that insectivores hold the second-most central position for virus sharing, second to bats, among all mammalian orders. Insectivores have a high proportion of cross-order transmitted viruses, including many human-associated viruses. Dietary diversity, habitat diversity, and distributional traits emerge as the key ecological factors contributing to cross-species virus transmission. Our findings highlight the microbial diversity in insectivores, indicating this order may serve as potential incubators for viruses capable of infecting mammals and spreading viruses of public health concern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) in humans originate from pathogens hosted by non-human animals through zoonotic transmission1,2. Wild small mammals are the primary animal sources of these EIDs3,4,5. Eulipotyphla (“true insectivores”, hereafter insectivores) is the third largest mammalian order, encompassing over 500 species across four taxonomic families: Erinaceidae (hedgehogs and moonrats), Soricidae (shrews), Solenodontidae (solenodons), and Talpidae (moles)6,7. Despite their small body size, insectivores can harbor a number of important zoonotic viruses, including but not limited to hantaviruses, Borna disease virus (BoDV), Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronaviruses (MERS-related CoVs), severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), and Langya henipavirus8,9,10,11,12,13, all of which pose challenges to human, wildlife, and domestic animal health. However, the epidemiology and ecology of microbes in insectivores remain largely unexplored and poorly understood. This gap is a priority for the early detection and warning of EIDs.

Outside of zoonotic viruses, insectivores have been shown to carry a wide spectrum of microbes, with some species having even more viruses than well-known viral hosts such as bats and rodents14,15,16,17. This includes many genetically distinct viruses through reassortment or recombination18,19. Some insectivore species (e.g., shrews) also have been shown to share many viruses with other wild species, even among host orders17. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that insectivores may play a prominent role in the generation of novel pathogen variants, subsequently spreading them to other wild species and eventually posing a threat to public health through spillover and emergence.

Previous studies of insectivores have typically focused on specific host and microbe species in limited geographic areas, reducing their ability to generally assess the diversity and distribution of microbes in this order. A systematic investigation of microbes in insectivores is lacking. In addition, most studies have primarily aimed at discovering novel pathogens. Consequently, less is known about the broader patterns of microbial diversity in insectivores and the factors that govern their transmission.

In this work, we integrated data from multiple sources to establish a comprehensive dataset of insectivores and their associated microbes. Our dataset comprised more than 400,000 records of insectivore hosts and 941 microbes from diverse habitats across the world, spanning from 1903 to 2023. With this extensive dataset, we aimed to (i) characterize the diversity and distribution of microbes in insectivores, including identifying viruses specifically with zoonotic potential and (ii) understand the role of insectivores in virus transmission across mammals more generally and to determine the ecological factors influencing this process.

Results

Insectivore dataset

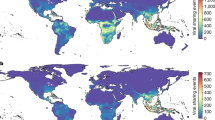

We established a multisource dataset comprising the geographic distribution of true insectivores, their microbe diversity and prevalence, and the genomic sequences of these microbes from 1903 to 2023. The dataset included 432,941 location records of insectivores globally (Supplementary Data 1). Insectivores were documented in their natural habitats across 161 countries and territories on all continents except Antarctica (Fig. 1a). They were particularly recorded in Europe and North America, with high frequencies in the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Spain, and Germany. The distribution of records among insectivore host families varied considerably (Supplementary Fig. 1). Shrews, hedgehogs, and moles had a similar number of records, while the solenodons accounted for a very small number of the total records (given only two extant species in this family, Atopogale cubana and Solenodon paradoxus).

a Spatial distribution of recorded insectivores. Darker shading indicates areas with higher numbers of insectivore species. Bar chart showing the log-transformed record count of four families of insectivorous across each continent. b Geographic distribution of microbes harbored by sampled insectivores. Darker shading indicates areas with increased microbial diversity. The accompanying pi chart displays the composition of four microbe categories (viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi) in different countries, with proportional areas representing relative richness. Base map from the Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform (https://www.resdc.cn). Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 3.

The dataset also contained 14,831 records and 10,245 genomic sequences of microbes in insectivores. The earliest microbial publication on insectivores was in 1905, and the number of related articles has gradually increased over time, reaching a total of 2,078 studies by 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Notably, most genomic sequences of microbes in insectivores were obtained in the past two decades. We observed a significant non-linear increase in the number of microbial species over time (\({{\chi }^{2}}_{{5.4,9}}=1224\), P < 0.001), with the greatest periods of change beginning after 2010 (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Diversity and distribution of microbes in insectivores

We found a wide variety of microbes in insectivores, with an identified 941 unique microbes, including 569 viruses, 226 bacteria, 117 protozoa, and 29 fungi, across 94 orders and 173 families in 137 insectivore species (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 4, and Supplementary Data 2). Microbes from the families Hantaviridae, Eimeriidae, Bartonellaceae, and Trypanosomatidae were the most detected, each found in more than 25 insectivore species. Notably, 41.12% (234/569) of the viruses were invertebrate-specific. We assessed potential sampling biases in these data. Rarefaction curves showed heterogeneous sampling coverage: curves for well-studied species (e.g., Eurasian shrew [Sorex Araneus]) approached saturation, whereas less-sampled taxa (e.g., genus Hylomys) and less abundant species failed to reach plateaus (Supplementary Fig. 5). We also found that microbial and viral richness accumulated as sampled species increased at the family level (Supplementary Fig. 6). Greater sampling effort was associated with identification of more microbes (generalized linear mixed effects model (GLMM): β = 0.074, P = 0.001). However, microbial diversity did not differ between urban-adapted and non-urban species (β = 0.546, P = 0.126), suggesting species in close proximity to humans are not driving results.

a Classification of microbes in insectivores. The three inner circles represent the category, phylum, and order of the microbes, respectively. In the fourth circle’s grid, the number of species in the microbe family are represented by a gradient color. The number of human-associated microbe species and invertebrate virus species in each family are indicated by black and red number, respectively. The circle outside the fourth circle represents the host. The outermost names correspond to the microbe families. b Non-metric multidimensional scaling analyses showing the variation in microbe composition among three host families within the insectivore order (Erinaceidae, n = 13; Soricidae, n = 104; Talpidae, n = 19). All samples are from different host species, each representing an independent biological replicate. Ellipses indicate 95% confidence intervals around the group centroid. Box plots display data distribution with the central line indicating the median, the box representing the interquartile range (IQR, 25th to 75th percentiles), whiskers extending to the most extreme data points within 1.5 × IQR from the box, and points beyond whiskers shown as outliers. NMDS axis differences were evaluated using two-sided t-tests. c Venn diagrams showing the number of microbes shared among three host families. Black and red denotes the number of microbes and the number of human-associated microbes, respectively. d Profiles of microbes and human-associated microbes in insectivore species. The boxes indicate microbes, viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. The Y-axis represents the number of microbes harbored by the host. Circle size represents the number of human-associated microbes, and the circle color indicates the proportion of human-associated microbes within the microbes. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 2.

The diversity and composition of microbes varied substantially among the host families within insectivores (Fig. 2a–c), however, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) and non-parametric permutation multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) analysis revealed no significant differences in microbial composition across these families (stress value = 0.121, R² = 0.024, P = 0.078; Fig. 2b). Shrews harbored the highest number of microbes, with 70% being viruses, predominantly from the families Hantaviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, and Phenuiviridae (Supplementary Fig. 4b). In contrast, hedgehogs had a higher proportion of bacteria, accounting for more than 50% of the microbes, mainly belonging to the families Arthrodermataceae, Leptospiraceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Borreliaceae (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Moles hosted fewer microbes, with the majority being protozoa from the family Eimeriidae (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Shrews and hedgehogs tended to share more microbes, whereas only 11 microbes were common to all three host families (Fig. 2c). Certain shrew and hedgehog species had especially high microbial richness. The European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus), house shrews (Suncus murinus), and Eurasian shrew each hosted over 100 microbial species (Fig. 2d). Some species were even capable of hosting a particularly high number of viruses. For example, Smith’s shrew (Chodsigoa smithii) hosted 152 viruses, 128 of which were invertebrate-specific viruses (Fig. 2a).

Microbes in insectivores were documented on six continents, with a predominant presence in Asia, Europe, and Africa (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Data 3). Microbial composition varied by continent (NMDS and PERMANOVA: stress value = 0.153, R² = 0.092, P = 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 7), with viruses and bacteria mainly recorded in Asia, Europe, and Africa. Fungi and protozoa were mainly found in Europe and East Asia. The geographic distribution of microbes also varied across different host families (NMDS and PERMANOVA: stress value = 0.144, R² = 0.14, P = 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 8).

Microbial prevalence

We next sought to determine the prevalence of microbes in insectivores, revealing considerable differences across microbe families (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Data 4–6). Among the virus families, the Circoviridae (91.30%, n = 1 study) and Parvoviridae (33.64%; 95% CI: 8.54-65.31%) had higher prevalence. Microbial prevalence varied significantly among different host families as well, with higher prevalence in hedgehogs (meta-regression: β = 0.12, P < 0.001) and moles (β = 0.14, P < 0.001; Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 10). Viruses in shrews mainly belonged to the Hantaviridae, Paramyxoviridae, and Sedoreoviridae families. The prevalence of the most prevalent viruses in each family was 46.67% (Xinyi virus, n = 1 study), 33.33% (Jeilongvirus apodeme, n = 1 study), and 15.22% (Rotavirus H, n = 1 study) respectively. In hedgehogs, high-prevalence viruses included Betacoronavirus erinaceus (54.40%; 95% CI: 22.70-84.22%), Mecsek mountains virus (45%, n = 1 study), and Jeilongvirus erinaceid (38.78%; n = 1 study). By contrast, viruses in moles were almost exclusively from the Hantaviridae family, including Academ virus (77.78% prevalence, n = 1 study) and Mobatvirus novaense (51.56% prevalence, 95% CI: 42.63–60.45%). Most bacterial and fungal species were present only in hedgehogs (Fig. 3). Anaplasma phagocytophilum had 65.41% prevalence (95% CI: 34.46–90.45%), Borreliella burgdorferi had 49.20% prevalence (95% CI: 0.16–99.69%), and Enterocytozoon bieneusi had 42.69% prevalence (95% CI: 10.34–79.15%). Protozoa with prevalence greater than 49.32% were almost exclusively present in moles (Fig. 3). Diagnostic methods and continents accounted for an average of 8.28% and 5.53% of the variance in prevalence, respectively. Microbial prevalence was not significantly different between urban-adapted and non-urban-adapted species (meta-regression: β = −0.008, P = 0.66). We also investigated the distribution of microbe prevalence across organs and continents (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). Details are described in the Supplementary Information.

a viruses, (b) bacteria, (c) protozoa, (d) fungi. The first column lists the microbe families. In the heat map, the three columns on the left represent the number of host species per family that carry the microbe, the middle three columns represent the meta-analysis prevalence in insectivore host families with color gradient from 0–100%, and the right column represents the number of countries where the microbe has been detected. The red dots on the right of the heatmap indicate human-associated microbes. The histograms denote the number of organs in which microbe has been detected. The forest plots illustrate prevalence and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for microbes in the insectivore order after meta-analysis. The circles indicate the pooled prevalence and error bars show 95% CIs. The number on the right indicates the number of studies included in the meta-analysis; blank indicates only one study. HCV-AC represents Human circular dsDNA virus associated with alcoholic cirrhosis. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 4–6.

Viral sharing networks

To better characterize the role of insectivores in virus transmission, we constructed host-virus correlation and virus-sharing networks. Insectivores harbored an average of 202 viruses per family, which was lower compared to ticks (Ixodida: 734), bats (Chiroptera: 366.36), and primates (Primates: 326.15), yet higher than that of rodents (Rodentia: 158.125; Fig. 4a and Supplementary Data 7). Meanwhile, the average number of viruses per genus in insectivores was 47.71, ranking second only to odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla: 86.0), primates (85.60), and bats (62.88), again surpassing rodents (40.95; Fig. 4a). Topological analyses of the virus-sharing network revealed that insectivores held the second-most central positions in the network, following bats and ranking above rodents among all mammalian host orders (Fig. 4b, d). However, sampling effort (i.e., citation counts) for insectivores was substantially lower than other mammals, representing only 3% of that for primates, rodents, bats, and carnivores (Carnivora; Supplementary Fig. 13b).

a Number of viruses harbored and shared by each mammalian order. Percentage represents the number of shared viruses per order divided by the total number of viruses per order, multiplied by 100. b Cross-order virus-sharing network. c Cross-family virus-sharing network. The size of each node depicts the closeness centrality. d Closeness centrality of mammalian orders in the cross-order virus-sharing network. The x-axis represents the weighted closeness centrality adjusted. The circle size represents the weighted closeness centrality. The circle color represents the closeness centrality. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 7.

Virus transmission likely occurred between insectivores and other hosts at multiple taxonomic levels: species (122 viruses), genus (108 viruses), family (86 viruses), and even order (84 viruses). We found that insectivores had a higher proportion of cross-order viruses (16.94%) than bats (5.36%) and true bugs (Hemiptera; 16.45%), comparable to that of primates (17.37%), though slightly lower than that of rodents (20.57%; Fig. 4a). The 84 cross-order transmitted viruses were shared with hosts from 34 distinct orders, such as rodents, primates, and even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla). The number of shared viruses between insectivores and other orders was significantly correlated with the phylogenetic distance of the hosts (Spearman’s ρ = 0.555, P = 0.002). Notably, in insectivores, human-associated viruses accounted for more than half (43/84, 51.19%) of the cross-order transmitted viruses, although they represented only a small portion (43/496, 8.67%) of the total viruses. Insectivores were more likely to share RNA viruses rather than DNA viruses: of the 84 cross-order transmitted viruses, 72 were RNA viruses and 12 were DNA viruses. In the RNA virus-sharing network, insectivores held the second-most central positions after bats among all mammalian orders, while they ranked fifth in the DNA virus network, below bats but above rodents (Supplementary Fig. 13c, d). In the human-associated virus-sharing network, insectivores ranked fourth, following bats, odd-toed ungulates, and carnivores among all mammalian orders (Supplementary Fig. 13e, g).

Viruses in insectivores were mainly found in the shrew and hedgehog families, prompting further investigation into virus-sharing patterns at different host taxonomic levels. The virus-sharing network at the host family level revealed that shrews and hedgehogs were more likely to transmit viruses to other hosts, ranking in the top 7% and 18% of the host families, respectively. In contrast, moles ranked in the top 53% (Fig. 4c). At the host species level, the house shrew, Eurasian shrew, and European hedgehog ranked in the top 13% of the 2801 included species (Supplementary Data 8). We observed a similar pattern when only considering human-associated viruses (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Data 9). These findings suggest that insectivores, particularly the shrew and hedgehog families, contributed significantly to virus transmission.

Ecological factors affect virus transmission

To further identify the ecological drivers governing the centrality of insectivores in virus transmission networks across families, genera, and species, we conducted phylogenetic comparative analyses using Phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS) models. The centrality of host families (λ = 0.533) and species (λ = 0.265) exhibited moderate and weak phylogenetic signals, respectively, whereas no phylogenetic signal was detected at the host genus level (λ = 0). We identified four, 17, and 10 competitive PGLS models (ΔAkaike information criterion (ΔAIC) < 2) at the family, genus, and species levels, respectively (Supplementary Data 10–12). Longevity was the most significant factor influencing host centrality at the family (β = 0.58, P < 0.001) and species (β = 0.14, P = 0.013; Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 13) levels. Habitat diversity was also positively associated with host centrality at the family (β = 0.28, P = 0.04), genus (β = 0.25, P < 0.001), and species levels (β = 0.08, P < 0.001; Fig. 5), indicating that habitat diversity may be a common trait among central hosts in virus transmission. In addition, host centrality at the family level was positively correlated with dietary diversity (β = 0.002, P = 0.01) and negatively correlated with phylogenetic distance (β = −0.29, P = 0.0034; Fig. 5a). At the species level, higher host centrality was correlated with larger range size (β = 0.13, P = 0.001), higher mean latitude (β = 0.14, P = 0.001), and lower phylogenetic distance (β = −0.67, P < 0.001; Fig. 5c). Additionally, we identified two significant interactions: urban adaptation enhanced the negative association between phylogenetic distance and host centrality (β = −0.70, P < 0.001), while longevity synergized with dietary diversity to increase host centrality (β = 0.11, P = 0.007).

The coefficients and corresponding P-values were estimated using the best PGLS models at host (a) family level, (b) genus level, and (c) species level (family n = 75, genus n = 198, species n = 664). The circles indicate the estimates and error bars show 95% CIs. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided PGLS tests; P-values reported represent nominal significance without adjustment. Red: P-values < 0.001, green: P-values < 0.01, dark orange: P-values < 0.05, and black: P-values > 0.05. Exact P-values for each coefficient and source data are reported in Supplementary Data 13.

We also examined differences in host traits across orders to broadly assess distinct ecological features of insectivore species (Kruskal-Wallis tests: P < 0.05). Among the 11 mammalian orders, insectivores have higher dietary diversity than rodents and bats, second only to marsupials (Didelphimorphia; Supplementary Fig. 14a). Although the median habitat diversity of insectivores is in the middle range (Supplementary Fig. 14b), moles and shrews rank in the top 3.95% and 21.05%, respectively. In addition, the mean latitude of insectivores is higher than that of all other mammalian orders including rodents and bats (Supplementary Fig. 14c), whereas their geographic range size is smaller than only carnivores, marsupials, and sloths and anteaters (Pilosa; Supplementary Fig. 14d).

Shrews and hedgehogs carry human-associated viruses closely related to those in humans

Phylogenetic trees revealed that 11 human-associated viruses found in shrews and hedgehogs were closely related to those identified in humans. These viruses can be divided into two major categories based on their transmission modes (Fig. 6).

a Phylogenies of vector-borne viruses. b Phylogenies of non-vector-borne viruses. Host species are indicated by different colors. Bootstrap support values (> 80%) are displayed at the node. The length of the branches in the tree are proportional to the number of nucleotide substitutions per site as indicated by the scale. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 15 and Source Data file.

The first category consisted of three vector-borne viruses likely transmitted to humans from insectivores via ticks (Fig. 6a). SFTSV in European hedgehogs clustered with strains from humans and Haemaphysalis longicornis in China (nucleotide identity 94.94–99.85%). Hedgehogs may serve as amplifying hosts of SFTSV, with Haemaphysalis longicornis as the primary transmission vector. In addition, Orthoflavivirus encephalitidis in Eurasian shrews and Orthoflavivirus usutuense in white-toothed shrews (Crocidura), both belonging to the Flaviviridae family, were phylogenetically related to human strains with nucleotide identities of 99% and 97.30–99.85%, respectively. Orthoflavivirus encephalitidis, the causative agent of tick-borne encephalitis, is endemic in Eurasia. The virus in shrews was also closely related to those from ticks, primarily transmitted by Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus.

The second category comprised eight non-vector-borne viruses, showing potential bidirectional transmission between insectivores and humans (Fig. 6b). The Langya virus in shrews was closely related to those in febrile patients (nucleotide identity 99.22–100%); shrews are considered the potential natural reservoirs for this virus20,21. Orthohantavirus hantanense, Orthohantavirus seoulense, and Orthohantavirus dobravaense, all within the Hantaviridae family, were also closely related to human strains (nucleotide identity 94.57–99.61%, 90.50–99.50%, and 95.40–97.93%, respectively). Similar relationships were observed for Orthobornavirus bornaense, Paslahepevirus balayani, and monkeypox virus. Notably, our phylogeny revealed that Simplexvirus humanalpha1 in the European hedgehog clustered within a group of human strains (nucleotide identity 99.05–99.87%), suggesting potential spillback to European hedgehogs, as humans are the primary hosts for this virus22.

Discussion

Role of insectivores as viral hosts

We observed that insectivores, particularly shrews, harbor a wide spectrum of viruses. Some shrew species may even carry a greater diversity of viruses compared to bats and rodents. Growing evidence suggests that insectivores serve as natural reservoir hosts for multiple viruses23,24,25. Although relatively little is known about which biological traits of insectivores may facilitate this high viral diversity, it is likely that they share certain characteristics with both bats and rodents that may allow for the efficient maintenance of viruses. Like rodents, insectivores have a fast life history, which may enhance transmission through population dynamics26, but, like bats, they also have high metabolism, exhibit torpor (as do some rodents), and may have unique immune responses to viral infection. Such bat-like factors likely contribute to the persistence of chronic infection or decrease viral replication through within-host dynamics5,27. Historically, our understanding of virus diversity in wild small mammals has been strongly skewed towards bats and rodents, with insectivores representing only a small fraction of mammals studied28,29,30. This can only in part be explained by the greater species richness of these two orders31, given the likewise speciose nature of the Eulipotyphla. Comprehensive investigation of the virome in insectivores, representing multiple species, distinct ecological habitats, and at the scale of individual animal, could offer a more complete view of the virus diversity in this order and offer insights into the emergence of zoonotic infections.

Potential incubator for novel viruses that could infect mammals

Our study reveals that insectivores carry a large proportion of invertebrate-associated viruses. This is likely due to the diet of species in this order, many of which have invertebrates as the majority of their diet. Moreover, a high abundance of arthropod-specific or related viruses has been found in various organs in shrews17, suggesting true infection rather than only colonization of the viruses. Enhanced surveillance and investigations are needed to clarify if arthropod-specific or related viruses can undergo adaptive evolution within insectivores and subsequently expand their host range to other mammals.

Moreover, the diversity of viruses found in insectivores could theoretically create favorable conditions for viral genome recombination and reconfiguration. Previous studies have demonstrated the presence of viral recombination or reassortment in shrews18,19,32, including reassortment between divergent virus strains33. Invertebrate-associated viruses may encounter opportunities to recombine or reassort with mammalian viruses in shrews, which might contribute to the emergence of novel viruses or variants. A comparable example has been observed in swine, which have been hypothesized to serve as “mixing vessels” for the evolution of influenza A viruses34. Swine are susceptible to infection with both avian and human influenza viruses, enabling the generation of genetically novel and pandemic strains through reassortment. For instance, the 1957 and 1968 pandemic strains influenza A viruses likely arose through reassortment between an avian influenza strain and the strain circulating in humans at the time35,36,37. Given this, it is plausible to suspect that shrews might similarly act as potential incubators facilitating the reconfiguration of viral genomes between mammalian and non-mammalian viruses; however, this hypothesis requires experimental validation through co-infection studies. Therefore, continuous monitoring and characterization of viruses circulating in insectivores are crucial for providing early warnings about the emergence of viruses or variants with increased pathogenicity or zoonotic potential.

Role of insectivores in cross-species transmission among mammals

Consistent with previous studies38,39, we found that bats, ungulates, and carnivores play important roles in the transmission of viruses among mammals. However, our study differs from previous studies in providing insights into virus transmission across mammals. We found that insectivores, specifically shrews and hedgehogs, contributed significantly to virus-sharing networks. The centrality of insectivores in both total virus and human-associated virus-sharing networks ranked second only to bats and surpassed that of rodents among all mammalian orders. The proportion of cross-order transmitted viruses was higher in insectivores than in bats and comparable to that in rodents. Notably, over half of the cross-order transmitted viruses in insectivores were human-associated viruses, indicating a heightened risk of zoonotic spillover.

As many previous studies have linked host functional traits to the processes of pathogen transmission and spillover26,40, we next explored insectivores’ factors contributing to their central roles in viral-sharing networks at different taxonomic levels (i.e., family-, genus-, and species-level networks). We found that habitat diversity was positively correlated with hosts’ centrality at all three levels. Dietary diversity was also positively associated with hosts’ centrality at the family level. These results were consistent with previous studies that proposed different levels of exposure to pathogens in hosts with different foraging traits40,41. For insectivores, their global distributions in diverse ecological habitats allow them to be exposed to more viruses and thus enhance their potential to spread viruses across different environments. The diverse diet of insectivores could also facilitate virus transmission by consuming a wide range of invertebrates (accounting for about two-thirds of their diet), which is consistent with the identification of many invertebrate-associated viruses. On the other hand, carnivores consuming virus-infected insectivores would also create opportunities for cross-species transmission. These predators could potentially act as amplifying hosts, contributing to the persistence and wider dissemination of these viruses. Consistent with several previous studies42,43, we showed that longevity was positively correlated with hosts’ centrality at both species and family levels. This could be explained by long lifespans facilitating greater cumulative exposure to viruses41. In addition, we also found a positive interaction effect between longevity and diet diversity at the species level, indicating that species with greater longevity and diet diversity might play a particularly important role in virus sharing.

Previous studies have shown that viruses are more likely to spread between phylogenetically related species39,44,45,46,47. We likewise found a negative relationship between phylogenetic distance and frequency of viral sharing among mammal species at both the family and species levels. Insectivores are ancient mammals, and viruses that evolved in insectivores may use conserved cellular receptors that enhance their ability to transmit viruses to other mammalian orders48. Contrary to previous studies42,43, we did not detect a significant correlation of urban-adapted status. However, we found a significant negative interaction effect between urban-adapted status and phylogenetic distance at the species level, suggesting that urban-adapted status can strengthen the negative effect of phylogenetic distance on host centrality. It has been suggested that urban-adapted species may show higher spillover potential due to their higher abundance, greater infection prevalence and intensity, and more interactions with humans26. For example, a recent study reported the circulation of SFTSV between hedgehogs and the Asian long-horned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) in Beijing resulting from the increased abundance of hedgehogs49, which can pose great spillover risk given the shared habitats between hedgehogs and humans. In the context of ongoing urbanization, most of which may occur in low- and middle-income countries with greater vulnerability to disease risk50, we call for more proactive surveillance in urban-adapted mammals, such as European hedgehog and Eurasian shrew.

Carrying viruses of public health concern

Lastly, our phylogenetic analyses revealed that certain viruses found in shrews and hedgehogs, such as Langya henipavirus, SFTSV, and BoDV-1, were closely related to viruses infecting humans. These viruses have been documented to transmit via various transmission routes and are known to cause diseases in humans10,50. For example, hantaviruses can be transmitted to humans through inhalation of respiratory secretions, leading to serious diseases such as hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Hedgehogs, often heavily infested with ticks, harbor multiple tick-borne viruses16,51. They have been recognized as amplifying hosts of SFTSV52,53, which can cause a wide range of clinical outcomes and has a case-fatality rate of 12–50%54,55,56. Shrews have been identified as natural hosts of the Langya henipavirus, which is closely related to the two well-known henipaviruses, Hendra virus and Nipah virus10. Langya henipavirus can cause respiratory symptoms and has been associated with febrile illness in humans, particularly in farmers who reported contact with shrews. We acknowledge that phylogeny-based inferences, while widely used to analyze cross-species transmission, cannot definitively rule out alternative scenarios. Our findings aim to highlight the risk of potential cross-species transmission, rather than to assert definitive transmission routes. Subsequent studies combining serology, viral isolation, and spatial-temporal sampling are needed to validate these inferences.

In addition, we observed that several human-associated viruses, such as SFTSV, exhibited high prevalence and multi-organ distribution in insectivores. Such viruses showed a broad host range and possess a high probability of crossing species barriers. Given the wide geographical distribution of insectivores, along with the high prevalence, multi-organ distribution, and various transmission modes of their viruses, there is an elevated likelihood of further zoonotic spillover events. Given these risks, we recommend surveillance of high-risk human populations, such as agricultural workers who may come into regular contact with shrews and hedgehogs, to assess the zoonotic potential of these viruses.

Furthermore, shrews and hedgehogs are not restricted to rural areas. They can thrive near humans in urban settings and thus could carry and sustain the natural circulation of their zoonotic viruses within suburban and urban environments49,57. Human activities that increase exposure to urban-adapted shrews heighten the risk of virus spillover to humans or domestic animals. Moreover, shrews tend to display bolder behaviors in urban settings58, which may in turn increase their contact with humans and increase the risk of virus spillover. Pathogen surveillance at the wildlife-human interface in urban settings should be considered as a critical component of public health interventions aimed at controlling infectious diseases.

Our findings highlight the necessity of expanding wildlife surveillance programs beyond traditional wildlife to include understudied insectivores. Systematic screening of hedgehogs and shrews could serve as an early warning system for emerging zoonotic threats. Public health agencies in areas with high insectivore biodiversity could prioritize community education about safe handling of these animals and enhanced diagnostic capacity for insectivore-associated pathogens in local healthcare systems. Urban green space management should prioritize creating buffer zones between insectivore habitats and residential areas.

Limitations

While we have implemented rigorous measures to mitigate the inherent biases in our dataset, the generalizability of our findings requires cautious interpretation. Our rarefaction curves showed heterogeneous sampling coverage of certain insectivore species, suggesting that microbial diversity in under-sampled taxa may require further characterization. Specifically, shrews and hedgehogs dominated the dataset, while less data is available for moles and solenodons. This disparity reflects a challenge in insectivore microbiology; cryptic and fossorial taxa (e.g., moles and solenodons) are chronically underrepresented due to logistical sampling constraints. Therefore, inferences regarding moles and solenodons remain provisional. For instance, the low viral diversity observed in moles may reflects their biological traits or artifacts of undersampling. Additionally, some insectivores in our dataset are urban-adapted species. Our analyses revealed no significant differences in microbial diversity and prevalence between urban-adapted and non-urban species, suggesting that urbanization has minimal impact on microbial communities in insectivores. Nonetheless, rural sampling gaps warrant caution; long-term monitoring of insectivores across urbanization gradients is essential to clarify the effect of urbanization on their microbial diversity.

Limitations of this study also stem from inherent biases in temporal and geographic sampling coverage. The temporal dynamics of microbial diversity underscore the profound impact of genomic sequencing on our understanding of microbes in insectivores. The majority of microbial genomic sequences from insectivores have been generated over the past two decades, coinciding with advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies. Future surveillance should prioritize combining metagenomic sequencing with targeted methods to comprehensively resolve the diversity of unculturable or novel microbes in insectivores. Geospatially, records of insectivores and their associated microbes were primarily from Europe, Asia, and North America, leaving key biodiversity hotspots like Southeast Asia and Africa drastically undersampled. These spatial gaps impede accurate risk mapping of potential zoonotic reservoir hosts. To address this, future studies should integrate spatially explicit sampling designs with machine learning approaches to optimize estimates of microbial diversity and spillover risk associated with insectivores in underrepresented regions.

Our study identified several ecological factors that contribute to cross-species virus transmission across mammals; however, capturing all possible ecological interactions remains challenging. Microbial diversity and transmission in wildlife are influenced by nonlinear interactions across spatial, temporal, and trophic scales. Future work is required to integrate field ecology data (e.g., animal movement tracking, dietary analysis, or environmental microbiome sampling) to investigate viral transmission among wild animals. We must also admit that some of the conclusions might be more speculative, particularly for virus transmission and zoonotic potential. Combined evidence from serological profiling, viral isolation and genomic sequencing, and epidemiological contact tracing is imperative to resolve transmission pathways; definitive zoonotic potential assessment necessitates experimental validation.

While our study focused primarily on the sharing of viruses because they accounted for over 60% of the microbes in insectivores, these hosts are also known to carry bacterial pathogens such as Leptospiraceae and multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, which may spill over via environmental contamination of soil or water. Similarly, keratinophilic fungi (e.g., Microsporum, Trichophyton) associated with insectivore fur could pose dermatophytosis risks to humans, suggesting that holistic microbe surveillance is critical for these animals47. Network analyses could be applied to investigate the sharing of bacterial and fungal species among insectivores. Future applications of multi-omics platforms may reveal important interactions between the viral, bacterial, and fungal communities in these animals, potentially offering mechanistic insights into zoonotic emergence.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that insectivores harbor a wide spectrum of microbes, particularly viruses. Shrews and hedgehogs in particular may serve as potential incubators for viruses capable of infecting mammals, and these families play a key role in the spread of viruses that pose significant public health risks. The repeated emergence of pandemic viruses that have originated from wild animals underscores critical gaps in current biosecurity systems. Subsequently, global surveillance and further research on insectivores should be intensified to better assess the risks associated with zoonotic transmission and to guide more effective strategies for disease prevention and control.

Methods

Data collection

We collected data on the Eulipotyphla, including information on the geographic locations of sampled insectivore hosts, the diversity and positivity (i.e., prevalence) of microbes, and genomic sequences of the microbes. These data were obtained from the literature, relevant websites, and the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). Electronic databases (PubMed and China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database) were searched by two independent reviewers (J.L. and L.H.) to extract data from research papers published before December 30, 2023, using a systematic protocol59. Searches were conducted using both the Latin and common names (in English or Chinese) of each insectivore species. To avoid inconsistencies, specific Latin names were referenced according to the NCBI Taxonomy Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi), disregarding the common names in the original publications. Publications were included if they contained relevant terms in the title, abstract, or keywords. Full-text publications were considered if they were in English or Chinese and provided detailed information on insectivores. Articles were excluded if they lacked sufficient information on the distribution (i.e., information on collection sites at the national scale or at finer spatial scales) and/or microbes (i.e., studies had to report testing for at least one microbe) of insectivores; duplicate articles were also excluded. The detailed data extraction procedure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2a. We assessed temporal changes in the number of microbial species carried by insectivores using generalized additive models (GAMs) fitted with the mgcv package in R (v4.3.1)60. The GAMs included microbial diversity as a negative binomial response and a yearly nonlinear term using thin-plate samples with smoothing penalties, fit using restricted maximum likelihood. To identify periods of significant change in microbial diversity, we calculated the first-order derivative of the prediction curve and assessed whether the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for this derivative overlapped with zero61.

Geographic distributions of insectivores were extracted using the Global Biodiversity Information Facility62 (https://www.gbif.org/) and mapped using ArcGIS (v10.8), supplemented by host geographic locations obtained from the literature. When exact locations were unavailable, the centroids of administrative areas were used. Additional microbial data of insectivores were retrieved from the Enhanced Infectious Disease Database (EID2)63 and GenBank database in April 2024. These microbes included viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Genomic sequences of viruses in insectivores were obtained from GenBank for phylogenetic analyses. Relevant details were extracted, including insectivore species, location, virus classification, and the dates of sequence submission and release.

Because measures of microbe diversity are highly susceptible to variation in sampling effort, including propensities to better sample host species that occur in close proximity to humans64,65, we used a series of analyses to correct for potential bias. Rarefaction curve analysis was conducted to evaluate sampling sufficiency for microbial diversity across insectivore families, genera, and species with at least five studies. We also used GLMM fit using the glmmTMB package to analyze the effects of urban adaptation and sampling effort on species-level microbial diversity, with host family as a random effect66. Urban adaptation status for each species was determined using a published database on long-term urban adaptation in mammals67. Species classified as “dweller” or “visitor” were considered “urban-adapted”, while those not included in the urban-adapted dataset were coded as “non-urban”. Urban adaptation was thus treated as a binary variable at the host species level with species coded as 0 (non-urban) or 1 (urban). Sampling effort was defined as the number of PubMed citations with the Latin name of the host species and the term “virus”. To further account for potential underestimation of microbial diversity in understudied taxa and regions, we implemented NMDS and PERMANOVA using the vegan package68. This analysis was based on the Jaccard distance matrix to quantify how host family taxonomy and continental geographic units influence microbial diversity.

Meta-analysis of microbe prevalence

To investigate the prevalence of microbes in insectivores, we conducted a meta-analysis to estimate their combined prevalence of positivity and 95% CI. Studies reported the number of all positive microbes using various assays, including PCR, next-generation sequencing, and microscopy. Studies were included irrespective of their methodological focus, provided they reported testing for at least one microbe. We calculated the pooled prevalence and 95% CI for microbe families/species in the insectivore order, as well as per insectivore family and species. For microbes containing only one study, the prevalence was calculated without a 95% CI. At the microbe family level, if the total number of positive samples was available in the original publication, prevalence was calculated by dividing the total number of positives by the number of samples tested. If it was not possible to determine the total number of positive samples due to the co-existence of multiple microbe species in individual samples, the highest prevalence for the microbe species was used to represent the entire family’s prevalence. Studies with fewer than 10 samples were excluded to minimize bias from underpowered datasets. Prevalence estimates were stabilized using the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation and analyzed using multilevel random-effects models via the rma.mv() function from the metafor package in R69. These models incorporated three random effects: a nested effect of observations within studies, diagnostic method, and geographic origin (continent)70. The diagnostic methods were classified into three distinct categories based on microbial detection principles: molecular biological techniques, microbiological cultures, and histopathological examinations. For studies reporting microbial data from multiple insectivore species, data from each species were analyzed independently to preserve taxonomic resolution. For analyses involving multiple species (e.g., by order/family/etc), we accounted for biological variability by including host species and microbial taxonomy as additional random effects. Meta-regression analyses were used to assess the effects of host family, tested organ, and urban adaptation on microbial prevalence. To further assess the methodological bias, we repeated the meta-analysis using a subset of studies published post-2000 (1118/1268).

Transmission network and centrality measures

We constructed a viral-sharing network to analyze the role of insectivores in virus transmission across mammals. The mammal-virus and invertebrate-virus interactions were extracted from the EID2 and GenBank databases, including 34,253 interactions between 16,194 viruses and 3731 host species. A bipartite network was constructed to connect each host order with its associated virus, comprising 18,497 interactions between 16,194 viruses and 141 host orders (20 mammalian orders and 121 invertebrate orders; Supplementary Fig. 15). This bipartite network was then projected onto a weighted unipartite network, where nodes represented host orders connected by the number of shared viruses. The cross-order virus-sharing network included 723 host-host interactions between 1039 viruses and 80 host orders (Fig. 4b). Additionally, networks were constructed at the host family, genus, and species level for different virus groups, including DNA viruses, RNA viruses, and human-associated viruses. Human-associated viruses were defined as those viruses detected in humans71.

Degree centrality, closeness centrality, eigenvector centrality, and the PageRank algorithm72 were calculated for each node in the viral transmission network. To adjust for host sampling bias, sampling effort was used to correct the centrality metrics. The correction was based on the residuals obtained from regressing centrality on sampling effort73,74. Specifically, centrality metric scores for each node were calculated using the number of shared viruses between two nodes as the edge weight, and these scores were then regressed against the sampling effort of each host. The residuals from each regression were used as the final centrality score for each node. The pairwise correlation coefficients between the four measures were all positive (Spearman’s ρ > 0.70, P < 0.05), indicating that the central hosts identified by different centrality indicators were similar (Supplementary Fig. 13a). Therefore, closeness centrality was selected as the primary indicator for assessing central hosts in virus transmission.

Ecological factors driving virus transmission

We used phylogenetic comparative analyses to determine the ecological factors influencing virus transmission across mammals. Life-history traits (body mass, longevity, litter size, and gestation time), foraging traits (habitat diversity and dietary diversity), distributional traits (range size and mean latitude), and urban adaptation status were collected from publicly available databases. Body mass and longevity data were sourced from the PHYLACINE75 and Amniote databases76, respectively. Data on litter size and gestation time were retrieved from the AnAge77 and Amniote76 databases. The size and mean latitude of hosts’ distribution range were obtained from PanTHERIA78. Urban adaptation status for each species was again determined using a published database on long-term urban adaptation in mammals67. Body mass and range size were log-transformed to reduce skewness. These species-level trait values were available for all the insectivore species in our analyses of host species centrality. The mean value (percentage for urban adaptation status) of a specific trait was calculated across the species within each genus or family to generate genus- or family-level trait values. Missing values were neglected when calculating genus- and family-level mean trait values.

Habitat use data were collected from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) database (http://www.iucnredlist.org). Dietary proportions were obtained from the PHYLACINE database. Habitat diversity at the species level referred to the number of habitats utilized by a species, whereas dietary diversity was calculated using the Shannon index based on dietary proportions. For both traits at the family and genus levels, dendrograms were generated for each trait, and Faith’s index (FD) was calculated by treating the species within the family or genus as a community. FD was calculated using the picante package79.

Phylogenetic trees for 75 host families, 198 host genera, and 664 host species of mammals were derived from the TimeTree31,80,81,82 and PHYLACINE75,83,84,85 databases. We conducted a systematic evaluation of polytomies using the ape package in R and confirmed that no hard polytomies were present within the phylogeny. Based on these trees, we calculated the pairwise phylogenetic distances between species, genera, and families, which were included in the following analyses of host centrality. Phylogenetic signal for host centrality in virus transmission networks at the family, genus, and species level were calculated using Pagel’s λ from the caper package42,86,87. A λ value of 0 indicates no phylogenetic signal, while λ of 1 suggests strong phylogenetic dependence.

PGLS models were then applied to examine the effect of the above host traits on the centrality in viral-sharing networks at the family, genus, and species levels. Candidate models were constructed by including as many main effects as possible (i.e., body mass, litter size, gestation time, longevity, dietary diversity, habitat diversity, range size, mean latitude, urban adaptation, phylogenetic distance), removing collinear predictor variables (i.e., Spearman’s ρ > 0.6; Supplementary Fig. 16). In addition to these main effects, the models incorporated the following interaction terms: 1) interactions between foraging traits (dietary diversity and habitat diversity) and distributional traits (range size and mean latitude); 2) interactions between foraging traits (dietary diversity and habitat diversity) and longevity; 3) interactions between dietary diversity and habitat diversity; and 4) interactions between urban adaptation and both range size and phylogenetic distance. These interaction terms were selected given hypothesized synergistic effects based on prior studies of microbe sharing39,65,88,89.

The number of predictor variables was limited to ensure that each estimated coefficient had at least 10 observations. Candidate models were compared using AIC, derived Akaike weights, and averaged coefficients when the ΔAIC of multiple models was less than two90. PGLS models were fitted using the phylolm package91, and model averaging was performed using the MuMIn package92. Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed to compare median differences in host traits that affect host centrality.

Phylogenetic analyses

We performed phylogenetic analyses to identify viruses in insectivores with zoonotic potential. For human-associated viruses found in insectivores, phylogenetic analyses were conducted based on the coding sequences (CDS) of conserved viral proteins, including the RdRp structural domain of RNA viruses, the capsid proteins of DNA viruses, and other specific genes of certain viruses (Supplementary Data 14). All available sequences for each virus in GenBank were utilized (Supplementary Data 15). Sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT (v7.525)93. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed using the IQ-TREE (v2.2.6)94, with branching support assessed using 1000 SH-like approximate likelihood ratio test (SH-aLRT) replicates (branches critical to cross-species transmission hypotheses required >80% support). Phylogenetic trees were visualized using ggtree, phangorn, and ggplot295.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The sequences of insectivores-associated microbes analyzed in this study are available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/) under accession numbers shown in Supplementary Data 15. Phylogenetic tree data for Fig. 6 are available in the Source Data. Host-microbe associations were compiled from PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), EID2, and GenBank, with detailed information available in Supplementary Data 2. Geographic distributions of insectivores and associated microbes were compiled from PubMed, CNKI, and GBIF, further details are provided in Supplementary Data 1,3. Host ecological traits were sourced from the PHYLACINE, Amniote, AnAge, and IUCN databases. All source data needed to fully replicate and evaluate the analyses are provided as Supplementary Data 1–15 and Source Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990–993 (2008).

Wolfe, N. D., Dunavan, C. P. & Diamond, J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature 447, 279–283 (2007).

Van Brussel, K. & Holmes, E. C. Zoonotic disease and virome diversity in bats. Curr. Opin. Virol. 52, 192–202 (2022).

Meerburg, B. G., Singleton, G. R. & Kijlstra, A. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol 35, 221–270 (2009).

Irving, A. T., Ahn, M., Goh, G., Anderson, D. E. & Wang, L.-F. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature 589, 363–370 (2021).

D’Elía, G. & Teta, P. Illustrated checklist of the mammals of the world. J. Mammal. 102, 1445–1446 (2021).

Wei, F.-W. Taxonomy and distribution of mammals in China. (Science Press, Beijing, 2022).

Guo, W.-P. et al. Phylogeny and origins of hantaviruses harbored by bats, insectivores, and rodents. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003159 (2013).

Puorger, M. E. et al. Distribution of borna disease virus antigen and RNA in tissues of naturally infected bicolored white-toothed shrews, crocidura leucodon, supporting their role as reservoir host species. Vet. Pathol. 47, 236–244 (2010).

Zhang, X.-A. et al. A zoonotic henipavirus in febrile patients in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 470–472 (2022).

Böhmer, M. M. et al. One Health in action: investigation of the first detected local cluster of fatal borna disease virus 1 (BoDV-1) encephalitis, Germany 2022. J. Clin. Virol. 171, 105658 (2024).

Li, D. et al. MERS-related CoVs in hedgehogs from Hubei Province, China. One Health 13, 100332 (2021).

Liu, J.-W. et al. Prevalence of SFTSV among Asian house shrews and rodents, China, January-August 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 2126–2128 (2014).

Falkenhagen, A. et al. Genetic and biological characteristics of species A rotaviruses detected in common shrews suggest a distinct evolutionary trajectory. Virus Evol. 8, veac004 (2022).

Low, D. H. W. et al. Cencurut virus: a novel Orthonairovirus from Asian house shrews (Suncus murinus) in Singapore. One Health 16, 100529 (2023).

Bown, K. J. et al. The common shrew (Sorex araneus): a neglected host of tick-borne infections?. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 11, 947–953 (2011).

Chen, Y.-M. et al. Host traits shape virome composition and virus transmission in wild small mammals. Cell 186, 4662–4675.e12 (2023).

Lee, S.-H. et al. Dynamic circulation and genetic exchange of a shrew-borne hantavirus, imjin virus, in the Republic of Korea. Sci. Rep. 7, 44369 (2017).

Ling, J. et al. Evolution and postglacial colonization of Seewis hantavirus with Sorex araneus in Finland. Infect. Genet. Evol. 57, 88–97 (2018).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Langya virus, a newly identified Henipavirus in China - zoonotic pathogen causing febrile illness in humans, and its health concerns: current knowledge and counteracting strategies - correspondence. Int J. Surg. 105, 106882 (2022).

Thien, D. H. et al. A comprehensive review of Langya virus and framework for future zoonotic disease control. Rev. Med Virol. 34, e2520 (2024).

Echenique, J. V. Z. et al. Fatal Simplexvirus humanalpha1 infection in howler-monkeys (Alouatta sp.) under human care: clinical, molecular, and pathological findings. J. Med Primatol. 52, 392–399 (2023).

Jin-Won, S. et al. Characterization of imjin virus, a newly isolated hantavirus from the ussuri white-toothed shrew (Crocidura lasiura). J. Virol. 83, 6184–6191 (2009).

Goethert, H. K., Mather, T. N., Johnson, R. W. & Telford, S. R. Incrimination of shrews as a reservoir for Powassan virus. Commun. Biol. 4, 1319 (2021).

Hilbe, M. et al. Shrews as reservoir hosts of borna disease virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 12, 675 (2006).

Albery, G. F. & Becker, D. J. Fast-lived hosts and zoonotic risk. Trends Parasitol. 37, 117–129 (2021).

Tian, S. et al. Comparative analyses of bat genomes identify distinct evolution of immunity in Old World fruit bats. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd0141 (2024).

Wu, Z. et al. Comparative analysis of rodent and small mammal viromes to better understand the wildlife origin of emerging infectious diseases. Microbiome 6, 178 (2018).

Cui, X. et al. Virus diversity, wildlife-domestic animal circulation and potential zoonotic viruses of small mammals, pangolins and zoo animals. Nat. Commun. 14, 2488 (2023).

Wu, Z. et al. Decoding the RNA viromes in rodent lungs provides new insight into the origin and evolutionary patterns of rodent-borne pathogens in Mainland Southeast Asia. Microbiome 9, 18 (2021).

Mollentze, N. & Streicker, D. G. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9423–9430 (2020).

Haring, V. C. et al. Small in size but huge as reservoir—insights into the virome of European white-toothed shrews. preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.14.567014 (2023).

Liphardt, S. W. et al. Reassortment between divergent strains of camp ripley virus (Hantaviridae) in the Northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda). Front Cell Infect. Microbiol 10, 460 (2020).

Webster, R. G., Bean, W. J., Gorman, O. T., Chambers, T. M. & Kawaoka, Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 56, 152–179 (1992).

Schäffr, J. R. et al. Origin of the pandemic 1957 H2 influenza A virus and the persistence of its possible progenitors in the avian reservoir. Virology 194, 781–788 (1993).

Kawaoka, Y., Krauss, S. & Webster, R. G. Avian-to-human transmission of the PB1 gene of influenza A viruses in the 1957 and 1968 pandemics. J. Virol. 63, 4603–4608 (1989).

Bean, W. J. et al. Evolution of the H3 influenza virus hemagglutinin from human and nonhuman hosts. J. Virol. 66, 1129–1138 (1992).

Wells, K., Morand, S., Wardeh, M. & Baylis, M. Distinct spread of DNA and RNA viruses among mammals amid prominent role of domestic species. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 470–481 (2020).

Albery, G. F., Eskew, E. A., Ross, N. & Olival, K. J. Predicting the global mammalian viral sharing network using phylogeography. Nat. Commun. 11, 2260 (2020).

Huang, Z. Y. X., Halliday, F. W. & Becker, D. J. Host functional traits as the nexus for multilevel infection patterns. Trends Ecol. Evol. 38, 1125–1128 (2023).

Smith, O. M. et al. A trait-based framework for predicting foodborne pathogen risk from wild birds. Ecol. Appl 32, e2523 (2022).

Yin, S. et al. Functional traits explain waterbirds’ host status, subtype richness, and community-level infection risk for avian influenza. Ecol. Lett. 26, 1780–1791 (2023).

Becker, D. J. & Han, B. A. The macroecology and evolution of avian competence for Borrelia burgdorferi. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 710–724 (2021).

French, R. K. et al. Host phylogeny shapes viral transmission networks in an island ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1834–1843 (2023).

Streicker, D. G. et al. Host phylogeny constrains cross-species emergence and establishment of rabies virus in bats. Science (1979) 329, 676–679 (2010).

Wang, J. et al. Individual bat virome analysis reveals co-infection and spillover among bats and virus zoonotic potential. Nat. Commun. 14, 4079 (2023).

Shaw, L. P. et al. The phylogenetic range of bacterial and viral pathogens of vertebrates. Mol. Ecol. 29, 3361–3379 (2020).

Calisher, C. H., Childs, J. E., Field, H. E., Holmes, K. V. & Schountz, T. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin. Microbiol Rev. 19, 531–545 (2006).

Zhang, X., Zhao, C., Si, X., Hu, Q. & Zheng, A. Natural circulation of tick-borne severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in the city ecosystem, China. Virol. Sin. 38, 832–835 (2023).

Neiderud, C.-J. How urbanization affects the epidemiology of emerging infectious diseases. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 5, 27060 (2015).

Geng, H. et al. Diversity analysis of tick-borne viruses from hedgehogs and hares in Qingdao, China. Microbiol Spectr. 11, e05340–22 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Hedgehogs as amplifying hosts of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 28, 2491 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Seroprevalence of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in hedgehog from China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 17, 347–350 (2017).

Takahashi, T. et al. The first identification and retrospective study of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 816–827 (2014).

Li, H. et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of laboratory-diagnosed severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China, 2011–17: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 1127–1137 (2018).

Liu, Q., He, B., Huang, S.-Y., Wei, F. & Zhu, X.-Q. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 763–772 (2014).

Wang, B. et al. Detection and characterization of three zoonotic viruses in wild rodents and shrews from Shenzhen city, China. Virol. Sin. 32, 290–297 (2017).

von Merten, S. et al. Urban populations of shrews show larger behavioural differences among individuals than rural populations. Anim. Behav. 187, 35–46 (2022).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. & PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern Med 151, 264–269 (2009).

Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315370279 (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2017).

Simpson, G. L. Modelling palaeoecological time series using generalised additive models. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00149 (2018).

GBIF.org GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.wr46fe (2024).

Wardeh, M., Risley, C., McIntyre, M. K., Setzkorn, C. & Baylis, M. Database of host-pathogen and related species interactions, and their global distribution. Sci. Data 2, 150049 (2015).

Gibb, R. et al. Mammal virus diversity estimates are unstable due to accelerating discovery effort. Biol. Lett. 18, 20210427 (2022).

Albery, G. F. et al. Urban-adapted mammal species have more known pathogens. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 794–801 (2022).

Brooks, M. E. et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R. J. 9, 378 (2017).

Santini, L. et al. One strategy does not fit all: determinants of urban adaptation in mammals. Ecol. Lett. 22, 365–376 (2019).

Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927–930 (2003).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03 (2010).

Konstantopoulos, S. Fixed effects and variance components estimation in three-level meta-analysis. Res Synth. Methods 2, 61–76 (2011).

Olival, K. J. et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 546, 646–650 (2017).

Tang, H. et al. TensorFlow solver for quantum PageRank in large-scale networks. Sci. Bull. (Beijing) 66, 120–126 (2021).

Gómez, J. M., Nunn, C. L. & Verdú, M. Centrality in primate–parasite networks reveals the potential for the transmission of emerging infectious diseases to humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 7738–7741 (2013).

Nunn, C. L., Altizer, S., Jones, K. E. & Sechrest, W. Comparative tests of parasite species richness in primates. Am. Nat. 162, 597–614 (2003).

Faurby, S. et al. scp>PHYLACINE</scp> 1.2: the phylogenetic atlas of mammal macroecology. Ecology 99, 2626–2626 (2018).

Myhrvold, N. P. et al. An amniote life-history database to perform comparative analyses with birds, mammals, and reptiles. Ecology 96, 3109–3109 (2015).

De Magalhães, J. P. & Costa, J. A database of vertebrate longevity records and their relation to other life-history traits. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 1770–1774 (2009).

Jones, K. E. et al. PanTHERIA: a species-level database of life history, ecology, and geography of extant and recently extinct mammals. Ecology 90, 2648–2648 (2009).

Kembel, S. W. et al. Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26, 1463–1464 (2010).

Kumar, S. et al. TimeTree 5: an expanded resource for species divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac174 (2022).

Price, T. D. et al. Niche filling slows the diversification of Himalayan songbirds. Nature 509, 222–225 (2014).

Youngblut, N. D. et al. Vertebrate host phylogeny influences gut archaeal diversity. Nat. Microbiol 6, 1443–1454 (2021).

Cox, D. T. C., Gardner, A. S. & Gaston, K. J. Diel niche variation in mammals associated with expanded trait space. Nat. Commun. 12, 1753 (2021).

Toussaint, A. et al. Extinction of threatened vertebrates will lead to idiosyncratic changes in functional diversity across the world. Nat. Commun. 12, 5162 (2021).

Andermann, T., Faurby, S., Turvey, S. T., Antonelli, A. & Silvestro, D. The past and future human impact on mammalian diversity. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb2313 (2020).

Revell, L. J., Harmon, L. J. & Collar, D. C. Phylogenetic signal, evolutionary process, and rate. Syst. Biol. 57, 591–601 (2008).

Freckleton, R. P., Harvey, P. H. & Pagel, M. Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: a test and review of evidence. Am. Nat. 160, 712–726 (2002).

Stephens, P. R. et al. Parasite sharing in wild ungulates and their predators: effects of phylogeny, range overlap, and trophic links. J. Anim. Ecol. 88, 1017–1028 (2019).

Dallas, T. A. et al. Host traits associated with species roles in parasite sharing networks. Oikos 128, 23–32 (2019).

Model Selection and Multimodel Inference. https://doi.org/10.1007/b97636 (Springer New York, New York, NY, 2004).

Tung Ho, L. S. & Ané, C. A Linear-Time Algorithm for Gaussian and Non-Gaussian Trait Evolution Models. Syst. Biol. 63, 397–408 (2014).

Bartoń, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. R package version 1.48.11, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn (2025)

Rozewicki, J., Li, S., Amada, K. M., Standley, D. M. & Katoh, K. MAFFT-DASH: integrated protein sequence and structural alignment. Nucleic Acids Res 47, W5–W10 (2019).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Schliep, K. P. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593 (2011).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Professor Xuejie Yu and Xuelong Jiang for helpful discussion on this study. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32470561, YFX, 32271605, ZYXH), Taishan Scholars Project (tsqn202306003, YFX), and Shandong Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (2022HWYQ-056, YFX). DJB was supported by the National Science Foundation (DBI 2515340, DJB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F.X. and F.W.W. conceptualized the initial hypothesis and conceived and designed the study. H.F.L., J.L., L.H., and X.M.W. collected the data and conducted the data analysis. H.F.L., Z.Y.X.H., D.J.B., and Y.H.W. performed the statistical analysis. H.F.L., X.M.W., and Y.F.X. carried out phylogenetic analysis and interpretation. H.F.L., J.L., and L.H. created and prepared the figures and tables. Y.F.X., D.J.B., Z.Y.X.H., and H.F.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. H.F.L., Z.Y.X.H., J.L., L.H., X.M.W., Y.H.W., X.J.L., Y.L., D.J.B., F.W.W., and Y.F.X. contributed substantially to data acquisition, interpretation, and revision and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Eyal Klement, Mekala Sundaram, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Huang, Z.Y.X., Lan, J. et al. Diversity and transmission and zoonotic potential of microbes in true insectivores. Nat Commun 16, 6709 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61835-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61835-6