Abstract

Electron avalanche breakdown plays a pivotal role in determining the efficiency and reliability of semiconductors and insulators in micro-nanoelectronics and power systems. However, it still remains challenging to understand and control this transient non-equilibrium process. Here, we propose and demonstrate an atomic-scale electron avalanche breakdown model to investigate the dynamic behaviors of excited electrons under extremely high electric fields in various dielectrics ranging from simple oxides to perovskites. Using high-throughput calculations, we establish the relationship maps between ionization energy, bond energy, electron mean free path and breakdown strength, and then excavate their mathematical expressions. On this basis, a high-entropy strategy in BaTiO3-based dielectrics with controllable lattice distortion is well designed to regulate the electron avalanche process, which successfully achieves a ~ 250% improvement in the breakdown strength by preventing electrons from acquiring sufficient energy. The atomic-scale understanding of electron avalanche breakdown process provides more refined guidance for atom/defect engineering to break the universal rule of inverse relation between breakdown strength and permittivity in dielectrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electron avalanche breakdown, triggered by collision ionization and avalanche multiplication of mobile electrons1, has gained increasing attention due to the rapid development of power electronic components and integrated circuit chips2,3. This is because the breakdown strength, inherently governed by the behavior of high field carriers like localization, excitation and transport, plays a crucial role in determining the maximum operating voltage, the power handling capability and cycling endurance of electronic devices such as capacitors4,5,6, memristors and transistors7,8,9,10,11. Therefore, understanding the underlying mechanisms behind the dielectric breakdown is essential for the rational design of high-performance and reliable modern electronic systems. Since the 1930s, several semi-classical and quantum mechanical models have been proposed to explain electron avalanche breakdown in solids at both the electronic and atomic levels12,13. While these approaches typically provide analytical solutions for steady-state conditions, they are unable to capture the multiscale dynamic process of dielectric breakdown step by step. Subsequently, fractal dimension models as well as phase field simulations have been implemented to understand the continuous evolution of breakdown paths observed in micro/mesoscopic scale experiments14,15,16. However, these phenomenological models lack the intrinsic physical implications and accurate initial parameters of the material, resulting in the underlying physical mechanisms that determine the formation and evolution of localized conductive pathways at the nanoscale remaining unclear. Thus, there is still a large gap between the practical breakdown phenomena and the theoretical knowledge of the breakdown mechanisms. For example, the effects of atomic engineering in experiments, such as element doping17,18, solid solution and high entropy design19,20,21, on the macroscopic dielectric breakdown properties remain unclear. Therefore, exploring the continuous dynamic breakdown process in conjunction with the atomic configuration and electron localization is essential not only for understanding dielectric breakdown failure, but also for advancing the performance and reliability of a broad range of electronic devices that rely on field-driven carrier dynamics.

To study the dynamic electron avalanche breakdown process in dielectrics, we propose an atomic-scale breakdown model that includes the following processes: (I) collision ionization between electrons and lattice atoms, (II) multiplication of local electrons, (III) breakage of chemical bonds, and (IV) formation of continuous avalanche channel, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (more details about the model are described in Methods). First, this model is employed to study the behaviors of electron dynamics, bond breaking, continuous avalanche path and corresponding changes in electrical properties under varying electric fields with the example of BaTiO3. Then, we consider three key atomic-scale variables of ionization energy, electron mean free path and bond energy to establish their relationship maps with the breakdown strength in different dielectrics ranging from simple oxides to perovskites. Through high-throughput simulations, we further clarify how to design atomic configurations with different lattice distortions to regulate the electron transport behavior and bond property. Then, several BaTiO3-based high-entropy dielectrics are theoretically predicted to have great potential for high breakdown strength, which is also verified by several targeted experiments. Additionally, we also analyze the influence of extrinsic factors such as oxygen vacancies on the electron avalanche breakdown behavior, thus explaining why the measured breakdown strength in experiments is significantly lower than the theoretical expected value.

a Collision ionization between electrons and atoms. b Multiplication of local electron density. c Breakage of chemical bond. d Formation of electron avalanche channel. q, λ, Eapp, Wi, Elocal, Welec and Wb represent the electron charge, the mean free path, the applied electric field, the ionization energy, the local electric field, the electric energy and the bond energy, respectively.

Results

Simulation of dynamic electron avalanche process

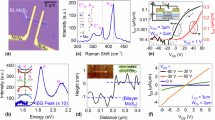

Taking BaTiO3 as an example, we first analyze the possible region where collision ionization and bond breakage occur by comparing the atomic features in a unit cell. As shown in Fig. 2a, owing to the larger atomic radius and lower electronegativity, the ionization energy (Wi) of Ba (5.21 eV) is much smaller than that of Ti and O (6.82 and 13.61 eV), implying that the Ba is more prone to be ionized out of electrons under the same electric field. Only two chemical bonds of Ti-O and Ba-O exist in BaTiO3, whose bond energy (Wb) would determine the tendency of avalanche path growth. Similarly, the Ba-O bond exhibits a lower Wb of 5.85 eV compared to the Ti-O bond of 6.93 eV. Thus, we consider that the Ba-O plane in BaTiO3 is the preferred region for the initiation of collision ionization and bond breakage, which is used for subsequent simulations. To characterize the initial atomic configuration of the Ba-O plane, phase field crystal method and density functional theory are employed to obtain the atom position, initial charge density and local electric field in the Ba-O plane22,23, respectively (see Supplementary Note S1 and Fig. S1). As shown in the left side of Fig. 2b, the local charge density around the O ion is as high as 1.2 e/Å2, while that around the Ba ion is approximately 0.2 e/Å2. The right side of Fig. 2b illustrates the corresponding local electric field distribution, and the arrows represent its direction. It can be observed that the smallest electric field is located at the center of each ion, and gradually increases toward the outside of the ion. Such phenomenon agrees well with some experimental observations by scanning transmission electron microscopy as well as computational simulations by density functional theory24,25.

a Comparisons of the ionization energy Wi of Ba/Ti/O and bond energy Wb of Ba/Ti-O in BaTiO3. b Initial charge density and corresponding local electric field distribution at the Ba-O plane, where arrows indicate the direction of the local electric field. c Evolution of the electron avalanche path with increasing electric field at the mean free path λ of 16 Å. d Changes of the normalized electrical conductivity under varying applied electric field with different λ of 4, 8, 12 and 16 Å.

Based on the above initial conditions, we start to dynamically study the electron avalanche process by simulating the spatio-temporal evolution of the avalanche path and the conductive behavior in BaTiO3 with the mean free path (λ) of 16 Å (a comparison with the Ti-O plane is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2). Four intermediate states during the avalanche breakdown process are exhibited in Fig. 2c, respectively. It is clear that the initial electron ionization is triggered from the Ba, then the avalanche path begins to expand rapidly along the Ba-O bond under an applied electric field (Eapp) of 569 MV/m, and finally the electron avalanche breakdown is almost entirely completed when Eapp increases to 576 MV/m. The corresponding local electron density and electric field distributions during the breakdown process are given in Supplementary Note S2 and Fig. S3, where the high electron density is predominantly distributed in the avalanche path and the local electric field is typically concentrated at its forefront. To better evaluate the critical behavior associated with the onset of avalanche breakdown, the normalized conductivity variations under increasing Eapp are calculated, as the blue curve shown in Fig. 2d. Upon increasing Eapp, the electrical conductivity remains almost unchanged initially until reaching a critical electric field, at which collision ionization is intensified and subsequently accompanied by local bond breakage. The resulting sharp increase in electron density and enhanced carrier mobility under high fields leads to a pronounced rise in electrical conductivity. When Eapp increases to the breakdown strength, a sharp evolution in the normalized electrical conductivity is observed, marking the ultrafast transition of BaTiO3 from an insulator to a (semi)conductor. It should be pointed out that the normalized electrical conductivity here is mainly intended to characterize the critical electric field that triggers breakdown and the rapid dynamic processes during the early stage of the avalanche, rather than to describe the macroscopic conductive behavior of the bulk material.

Unlike the constant parameters of Wi and Wb in BaTiO3, λ can be affected by the intrinsic characteristics and external stimuli, such as microstructure and ambient conditions26,27,28, which cause its value to change in a certain range. Thus, we also study the electron avalanche breakdown process with different λ, as displayed in Fig. 2d. As λ decreases, the distance the electron can travel freely is shortened, resulting in a corresponding reduction in the kinetic energy. Therefore, the free electrons with lower λ require a higher electric field to gain enough energy to ionize the lattice atoms. As a result, the avalanche breakdown strength increases from 576−1128 MV/m as λ varies from 16 to 4 Å in BaTiO3. Thus, λ is an important and variable factor that can significantly affect the breakdown strength.

Structure-property relationship maps

Apart from variable λ, the other two key intrinsic parameters, Wi and Wb, can also be tuned at the atomic scale in different experiments. Thus, to fully explore the correlation between these parameters and the breakdown strength (Eb), the dependences of Eb on Wi, λ and Wb are mapped by performing high-throughput calculations. Figure 3a shows the mapped Eb as functions of Wi (4 ~ 10 eV), λ (4 ~ 16 Å) and Wb (2 ~ 10 eV), suggesting that Eb gradually goes up from the upper left to the bottom right of the mapping as both Wi and Wb increase and λ decreases. Moreover, Fig. 3b further illustrates the possible quantitative functions between Eb and each parameter. It can be seen that Eb exhibits different dependences on those three parameters, i.e., \({{E}}_{{{\rm{b}}}}\propto \,{{{\rm{ln}}}}({W}_{i})\), \({{{\rm{E}}}}_{{{\rm{b}}}}\propto {\lambda }^{-1/2}\) and \({{E}}_{{{\rm{b}}}}\propto {W}_{{{\rm{b}}}}^{1/2}\), respectively, in which Eb has a stronger dependence on Wi and λ than Wb. More specifically, with Wi increasing from 4−10 eV while maintaining λ at 4 Å and Wb at 10 eV, Eb increases from 1035−1559 MV/m. However, Eb only increases from 935 to 1035 MV/m when Wb increases from 2 to 10 eV while Wi is 4 eV and λ is 4 Å. Then, we also excavate the analytical expression for Eb by regression analysis using the least squares regression (see Supplementary Note S3, Table S1 and Fig. S4), that is,

a High-throughput simulation results of Eb for perovskite dielectrics with different Wi, λ and Wb. b Eb as functions of Wi, λ and Wb, respectively. c Comparisons of Wi, λ and Wb for different dielectrics. d Prediction of Eb as a function of dielectric constant εr for different dielectrics ranging from simple oxides to perovskites, where the inset shows a magnified view of the low εr region. The relation Eb = 3500 εr−0.64 (MV/m) proposed by McPherson et al. is also presented for comparison33, and experimental breakdown dates are from Supplementary Table S3.

Thus, Eq. (1) implies that the Eb of dielectric materials can be enhanced by designing atomic-scale features of higher Wi, Wb and lower λ.

To find more universal rules for the breakdown strength, we then extend this electron avalanche breakdown model to a wide range of dielectric systems. Focusing on the three key atomic-scale variables Wi, λ and Wb, we semi-quantitatively predict the Eb of 14 common dielectrics ranging from simple oxides (SiO2, Al2O3, MgO, HfO2, Ta2O5, ZrO2 and TiO2) to ABO3 perovskites (CaTiO3, SrTiO3, AgNbO3, BiFeO3, PbZrO3, BaTiO3 and PbTiO3). Figure 3c presents the details of these three atomic-scale parameters for different dielectrics (see Supplementary Note S4 and Table S2 for more details). Here, Wi and Wb of each dielectric are fixed based on the specific component and crystal structure, which can be reasonably determined by identifying the element and chemical bond with the lowest ionization energy and weakest bond energy within the ionization region, respectively. However, since λ is affected not only by the inherent physical and chemical properties of the material but also by extrinsic factors such as defects as well as variations in morphology and microstructure, we consider a range of possible numerical variations in practical experiments. The left panel of Fig. 3c exhibits Wi and Wb for each dielectric, where Wi and Wb of most perovskites are usually smaller than that of these simple oxides. As shown in the right panel of Fig. 3c, λ of simple oxides (2 ~ 10 Å) are mostly smaller than that of perovskites (10 ~ 25 Å), which may be due to that the scattering probability of electrons is increased and electron migration is impeded in more insulating oxides29. To intuitively understand the universal rule of the breakdown strength, Fig. 3d displays the calculated Eb of different dielectrics from simple oxides to perovskites using the dielectric constant (εr) as the characteristic parameter. It is found that Eb decreases significantly with increasing εr as a function of Eb = 1846εr-0.18 (MV/m) with a coefficient of determination R2 of 0.889, which is consistent with the inverse coupling relationship between Eb and εr mentioned in lots of reports29,30,31,32,33,34,35. It is worth noting that the negative power law of Eb ~ εr-0.18 obtained here differs from previously proposed theoretical and empirical relations of the form Eb ~ εr-α, with reported exponents α ranging from 0.5 to 0.6530,31,33,34. Most studies rely on statistical fitting across large datasets or employ static theoretical model predictions, which do not properly solve the microscopic parameters-related collision ionization and bond breaking. As such, previous approaches unable to fully capture the non-equilibrium dynamic characteristics of the breakdown process. While in our electron avalanche breakdown model, physically meaningful atomic-scale parameters like Wi, λ and Wb are comprehensively considered to simulate continuous avalanche paths under high fields. In addition, λ is treated as varying within a reasonable numerical range that reflects the effects of both intrinsic properties and extrinsic factors on the electron scattering, thereby providing realistic predictions of the breakdown process and fundamental insights into its underlying atomic-scale mechanisms of avalanche breakdown behavior. Specifically, some ferroelectric perovskites with high εr (e.g., BaTiO3, BiFeO3, PbTiO3) are typically accompanied by lower Wi, Wb and higher λ, which increase the likelihood of collision ionization (related with Wi and λ) and bond breakage (related with Wb). Consequently, perovskite dielectrics usually exhibit lower Eb of <600 MV/m. In contrast, for low εr oxides (e.g., SiO2, Al2O3, MgO) with higher Wi, Wb and lower λ, the initiation of avalanche breakdown is significantly delayed, with a higher Eb of >1200 MV/m. As shown in Fig. 3d, some experimental results represented by the red solid symbols are dispersed around the fitted curve (see Supplementary Table S3 for more details), which strongly support the reliability of our analytical expression. Furthermore, this electron avalanche breakdown model is not only applicable to oxide dielectrics, but can also be extended to other highly insulating materials like nitride compounds36,37, to elucidate variations in breakdown strength and provide fundamental insights into the underlying mechanisms at the electronic and atomic levels.

High-entropy design strategy

The results of both our model predictions and the experimental tests indicate that the dielectric constant and the breakdown strength are strongly inversely coupled in nature38,39,40, which has become a major contradiction in dielectric materials. Based on our model predictions that the atomic-scale parameters of Wi, λ and Wb have a significant influence on the electron avalanche breakdown process, it is possible to regulate those three variables to improve the breakdown strength by introducing foreign atoms into the lattice sites. Taking BaTiO3 as the pristine matrix, we use the avalanche breakdown model to reveal how the atomic configurations affect the microscopic electrical properties and the corresponding breakdown strength. Here, the main focus is on cation substitution at the A/B-sites, while anion doping (e.g. replacing oxygen with fluorine or nitrogen) that also shows an important role in modulating the dielectric properties is not considered yet41,42. Because the Wi of Ba/Ti in BaTiO3 is smaller than that of common doped atoms (e.g., Sr, Ca, La, Nd, Sm as A-site dopants and Zr, Hf, Sn, Ta as B-site dopants), the substituted atom in A/B-sites almost makes ionization more difficult and thus slows down the electron avalanche. While for the influence of substituted atoms on λ and Wb, the situation becomes more complex and variable. One of the most typical atomic features caused by the substitution atom is lattice distortion (δ). High contents of heteroatoms, which induce large δ, can increase the probability of electron collision with lattice atoms, thereby reducing λ43, as shown in Fig. 4a. The relationship between λ and δ can be obtained semi-quantitatively by fitting the electrical properties of BaTiO3-based dielectrics (see Supplementary Note S5 and Fig. S5). In addition to regulating the electron transport behavior, the lattice distortion also affects the local bond properties. As shown in Fig. 4b, the lattice distortion would cause chemical bonds to be compressed or stretched, leading to the variations in bond length (r) and thus lower the bond energy compared to the initial bond. The relationship between Wb and r can be determined by Mie-Grüneisen bonding potential (see Supplementary Note S6 and Table S4)44. It also should be pointed out that the new chemical bond X-O formed by the introduction of conventional elements (such as Na, Sr, Ca and Sn) are generally smaller than the Ba/Ti-O bond energy, whereas some rare metal elements including rare earths (such as La, Nd, Sm, Zr, Hf, Sc and Ta) could form a higher bond energy. Therefore, the variations of λ and Wb caused by the introduction of heteroatoms have complex effects on the electron avalanche breakdown. How to introduce suitable atoms to balance these mutual impacts on the breakdown strength is a thorny problem faced by multi-element replacement experiments.

To address this challenge, we first study how A-site atom doping affects δ and Eb by considering ionic radii compatibility and charge balance (see Supplementary Note S7 and Fig. S6). Here, four representative solid solution systems (Ba1-2xSrxCaxTiO3, Ba1-2xNaxLaxTiO3, Ba1-2xNaxNdxTiO3, Ba1-2xNaxSmxTiO3) are considered. The larger the difference in ionic radii between the elements, the larger the lattice distortion, such that the δ of Ba1-2xNaxSmxTiO3 can reach ~10.9% at doping content x of 0.3, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S6a. As a result, the Eb is enhanced by nearly 2.1 times, as shown in Fig. 4c. Here, we assume that the doped atoms are discretely distributed in the lattice sites so as to be able to achieve the ideal δ, as shown in the insets of Fig. 4c. However, in practice, due to the influence of the dynamics of nucleation and growth in experimental preparation45,46, doped atoms may agglomerate and concentrate in a certain region of the lattice, which prevents the actual δ from reaching the optimal value. As a result, the electron scattering and breakdown enhancement may be greatly suppressed due to the aggregation distribution of atoms in elemental doping or solid solution systems. Therefore, achieving local uniform dispersion of foreign heteroatoms to improve the lattice distortion and thus reduce the mean free path is a key and challenge to improve the breakdown strength in experimental design.

Recently, high-entropy strategy has been recognized as a feasible and effective method to easily modulate the local atomic heterogeneity to realize near-ideal lattice distortion4,19,47,48,49. On this basis, we design a series of BaTiO3-based dielectrics with different atomic configurations to improve the breakdown strength by gradually introducing equimolar-ratio elements, i.e., Sr, Ca, Na, Nd, Sm and Zr, Hf, Sn, Sc, Ta into the Ba site and Ti site, respectively, with the nominal composition of Ba1-4xSrxCaxNaxSmxTiO3, BaTi1-5xZrxHfxSnxScxTaxO3, Ba1-2xSrxCaxTi1-2xZrxHfxO3, Ba1-3xSrxNaxNdxTi1-2xZrxHfxO3, and Ba1-3xSrxNaxSmxTi1-2xZrxHfxO3. Here, the configurational entropy (Sconfig) is used to represent different atomic configurations (see Supplementary Note S8 and Fig. S7), and is taken as a feature variable to systematically investigate its effect on Eb. The variation ratio of λ is shown in Supplementary Fig. S7c, where λ is found to first decrease significantly and then increase with Sconfig. We also note that due to the difference in ionic radii between foreign atoms and matrix atoms, different material systems exhibit various lattice distortion at the same entropy, thereby affecting the electron scattering probability as well as the corresponding electron mean free path. In addition, simultaneous multi-element doping of the A-site and B-site can further enhance lattice distortion with respect to single doping of the A-site or B-site, and it is more obvious when the high entropy system is doped with rare earth elements. As a result, the variation ratio of λ for BaTi1-5xZrxHfxSnxScxTaxO3 is about -60.4% at Sconfig of 1.5 R, while the variation ratio of λ for Ba1-3xSrxNaxSmxTi1-2xZrxHfxO3 reaches a maximum of -92.9% at Sconfig of 2.28 R. For Wb, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7d, the variation ratio of Wb decreases continuously with the increase of Sconfig due to entropy-induced lattice distortion. It is worth noting that the introduction of rare metal elements in high-entropy materials can form higher bond energy with the O atom, which could effectively mitigate the detrimental effects of lattice distortion on bond energy. Specifically, for Ba1-4xSrxCaxNaxSmxTiO3 with more conventional elements such as Sr, Ca, and Na, Wb is reduced by 21.7% at Sconfig of 1.61 R. With the introduction of rare metal elements like Zr, Hf, Sc, and Ta, the overall Wb of BaTi1-5xZrxHfxSnxScxTaxO3 could increases by 6.3% at Sconfig of 1.79 R. Consequently, as the variation ratio of Eb shown in Fig. 4d, all high entropy systems exhibit a tendency for Eb to first increase and then decrease in line with the rise in entropy, a similar trend of Eb with entropy has also been observed in other material systems (see Supplementary Fig. S8). However, the position and value of the peak in the change curve of Eb vary between high-entropy systems. This is primarily due to the fact that the same entropy may bring different lattice distortion and bond energy change in different systems. For example, for BaTi1-5xZrxHfxSnxScxTaxO3, the maximum Eb located at Sconfig of 1.5 R with an increase of ~1.6 times. With more significantly reduction of λ and slightly weakening Wb in Ba1-3xSrxNaxSmxTi1-2xZrxHfxO3 with Sconfig of 2.28 R, the Eb exhibits a maximum about 3.5 times that of the pristine BaTiO3. Thus, the changes in mean free path and bond energy in high-entropy materials are two fundamental reasons for the variation of the breakdown strength, and especially, rare earth elements have notable advantages in modulating the mean free path and bond energy. Among these BaTiO3-based dielectrics predicted above, we choose Ba1-3xSrxNaxSmxTi1-2xZrxHfxO3 as the targeted materials to verify our theoretical predictions (see Supplementary Note S9 and Fig. S9), as shown by the purple solid symbols in Fig. 4d. As Sconfig increases, the sluggish diffusion effect in experimentally high entropy films leads to the inevitable formation of amorphous phases50. The coexistence of disordered amorphous phases and highly distorted crystalline regions significantly enhance the electron scattering effect, boosting Eb by ~3 times at Sconfig of 2.28 R. As Sconfig further increases to 2.43 R, Eb decreases significantly, mainly attributed to more local impurity aggregation and structural defects caused by excessive multi-elements doping and further diffusion kinetics limitation at higher entropy49,51. Although the model does not account for the amorphous phases observed experimentally, the great enhancement of Eb indicates that the electron scattering effect constructed by the entropy-induced large lattice distortion does work. Therefore, based on the avalanche breakdown model, it is found that the lattice distortion in the crystalline region of high-entropy systems can also effectively regulate the electron transport and local bond property to significantly enhance the breakdown strength. Meanwhile, a general and practical theoretical design principle is provided for the selection of multiple doping elements in high-entropy dielectrics.

The effect of oxygen vacancies

In practical experiments, the measured breakdown strength is often lower than the theoretical predicted value, which is mainly due to the influence of extrinsic factors (e.g., lattice defects, chemical impurities, cavities and cracks)52. Among these extrinsic factors, oxygen vacancy (VO), one of the most common defects in dielectrics, is considered to be responsible for the reduced breakdown strength53. As shown in Fig. 5a, the VO may act as trap sites to capture electrons. Under high electric field stimulus, trapped electrons can be emitted into the conduction band to become free electrons, which increases the leakage current and decreases the resistivity. According to the Poole-Frenkel emission54, the contribution of VO to the local electron density can be approximated as \({N}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}},{t}){=}{q}{{N}}_{c}{{{\rm{exp}}}}[-\frac{{W}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}-\sqrt{{q}^{3}{E}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}},{t})/\pi K{\varepsilon }_{0}}}{{k}_{B}T}]\), where Nc, Wt, K, kB and T are the effective density of states of the conduction band (about 8 × 1024 m-3), trap energy level (about 0.2 ~ 0.8 eV for VO), optical permittivity, Boltzmann constant and temperature, respectively. Thus, transforming the shallow Wt into a deeper one is beneficial to reduce electron excitation and improve the breakdown strength, which is also one of the important strategy to regulate the oxygen vacancy in experiments55.

a Schematic diagram of the oxygen vacancy effect on electron transport behavior. b Variations of the maximum local electric energy of different trap energy levels Wt under the increasing electric field. c Comparisons of the electron avalanche path with Wt of 0.2 and 0.8 eV in Ba-O plane. d Dependences of breakdown strength Eb on Wt and effective density of states Nc in BaTiO3.

To investigate the effect of Wt on the electron avalanche breakdown process, we firstly calculate the variation of maximum local electric energy (\({W}_{{{\rm{elec}}}}^{{{\rm{max}}}}\)) under different Eapp with Wt of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8 eV. Here, the λ of BaTiO3 is set to 4 Å and the corresponding Eb of 1128 MV/m is used to compare the variation of Eb with different VO. As shown in Fig. 5b, upon increasing Eapp, the initial growth rate of \({W}_{{{\rm{elec}}}}^{{{\rm{max}}}}\) is small and then rapidly increases when reaching the critical electric field. As Wt varies from 0.2 to 0.8 eV, the electric field where the \({W}_{{{\rm{elec}}}}^{{{\rm{max}}}}\) is greater than the critical Wb (the point where the red dotted line intersects the curve) tends to move to a higher value. This indicates that compared with the low Wt, the oxygen vacancy with high Wt is conducive to reducing the local electric energy of electrons, thus delaying the chemical bond breaking. Then, we further compare the local electric energy distribution of Wt at 0.2 and 0.8 eV, as shown in the left side of Fig. 5c. At Wt of 0.2 eV, \({W}_{{{\rm{elec}}}}^{{{\rm{max}}}}\) is mainly concentrated around VO and exceeds the critical Wb when Eapp reaches 361 MV/m. While for Wt of 0.8 eV, \({W}_{{{\rm{elec}}}}^{{{\rm{max}}}}\) appears around the Ba and the bond does not break until Eapp reaches 1118 MV/m. As a result, the difference in the local electric energy distribution leads to completely different electron avalanche paths and breakdown strengths, as presented in the middle and right sides of Fig. 5c. When Wt is low, the captured electrons are very easily excited by the electric field to escape from VO and become free electrons. At this time, VO as the triggered point dominates the electron avalanche breakdown process, with the final breakdown strength of 381 MV/m at Wt of 0.2 eV. As Wt increases to 0.8 eV, VO strongly traps electrons and electrons excitation is greatly suppressed. In this case, the generation of free electrons mainly comes from the collision ionization, and thus the avalanche breakdown prefers to initiate from the Ba, which is basically consistent with the dielectric breakdown process in Fig. 2. As a result, the breakdown strength could reach 1126 MV/m, which is comparable to the intrinsic values and is almost 3 times larger than that with Wt of 0.2 eV. In addition to Wt that can control local electron behaviors, the concentration and distribution of VO have also been proved to modify the localized electron density by influencing Nc as they introduce additional energy levels within the band gap or affect the conduction band structure56,57. Then, we plot the mapped Eb as functions of Wt (0.2 ~ 0.8 eV) and Nc (8×1021 ~ 8 × 1024 m−3), as shown in Fig. 5d. It can be seen that by increasing Wt and decreasing Nc, the breakdown strength could be increased several times over as the breakdown mechanism transitions to the intrinsic dielectric breakdown. Thus, the black dashed line shown in Fig. 5d not only represents the boundary of the breakdown mechanism transformation, but also identifies the thresholds of Wt and Nc corresponding to the intrinsic dielectric breakdown. Such a breakdown characteristic shift revels the significance of rational design and precise control of oxygen vacancy for the insulating reliability of electronic devices.

Discussion

In summary, an atomic-scale electron avalanche breakdown model is developed to investigate the continuous and dynamic avalanche process in solid dielectrics by coupling collision ionization and bond breakage. Simulation results reveal that the breakdown strength is fundamentally governed by the atomic-scale physical parameters, including ionization energy, bond energy and electron mean free path. The mapping relationship between the breakdown strength and these parameters is established through high-throughput calculations, from which regression analysis is employed to obtain an analytical expression for the breakdown strength as a function of these variables. Furthermore, it is found that the lattice distortion induced by local atomic heterogeneity via a high-entropy strategy in BaTiO3-based dielectrics can effectively suppress the electron avalanche process, resulting in ~250% enhancement in breakdown strength. Moreover, the extrinsic factor oxygen vacancy could alter the breakdown behavior and induce a transition in the breakdown mechanism by modulating the local electron excitation barrier. The theoretical insight on the avalanche breakdown gained in this work is expected to provide precise guidance for exploring and designing novel dielectrics with the requirement of high voltage endurance. Additionally, the fundamental mechanisms revealed here can potentially be extended to predictive modeling of field-driven switching behaviors in emerging electronic systems such as memristors and neuromorphic nanodevices.

Methods

Here, we divide the evolution of electron avalanche breakdown into four stages as shown in Fig. 1. For the first step of collision ionization, a critical avalanche would form when the initial electrons undergo forty generations of collision ionization, as proposed by Seitz et al.1, which provides an important theoretical basis for building the atomic-scale breakdown model. However, the ionization process involved in this theory relies on some constant preconditions like specific electric field, ionization energy and avalanche path, which is difficult to consider the dynamically changing in spatial and temporal. Here, we reconsider that the collision ionization depends on the dynamic interaction between free electrons and lattice atoms. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, free electrons, driven by the applied electric field, collide inelastically with lattice atoms. The higher the energy of free electrons gained from the electric field, the greater the probability of bound electrons escaping from the nucleus. On this hypothesis, we define an ionization rate α(Eapp) to describe the dynamic probability of electron ionization based on how much energy is gained as follow:

where q is the electron charge, λ is the electron mean free path (about 4 ~ 20 Å in solid dielectrics), Eapp is the applied electric field, Wgain is the free electron energy gained from the applied electric field, and Wi is the ionization energy. Considering that lattice atoms are typically bound and in an ionic state, the energy required to ionize such ions is usually much higher than that for neutral atoms. As such, during inelastic collisions between free electrons and lattice atoms, the process is more likely to involve first exciting the electrons to higher energy states that similar to outer orbitals of neutral atoms before ionization occurs58,59. Following this excitation, ionization then occurs and the released electrons are involved in further ionization events, thus accelerating avalanche breakdown. To simplify the complex nonlinear behavior of ionization, we approximate the energy required to ionize electrons of lattice atoms as comparable to the ionization energy of neutral atoms at the initial stage of the electron avalanche breakdown (>4 eV for most atoms60, see Supplementary Fig. S10).

For the second step, electron multiplication represents that the subsequent repetition of the collision ionization process leads to a continuous increase in the local electron density N(r, t). To describe the electron multiplication process under the high electric field quantitatively, we introduce an exponential mathematical expression based on the ionization rate to capture the nonlinear dynamic evolution of the local electron density over the electric field61, which is expressed as:

where N0 is the outer electron density that affects chemical bonding. With the continuous ionization and multiplication of the electrons, the local electric field around atoms would increase due to more and more electrons being excited. As shown in Fig. 1b, the ionized electrons in the excited state are temporarily confined around the atom due to the electrostatic attraction of the chemical bond62. As the excited electrons gradually gather around the atom, the local electric field Elocal accumulates, which can be obtained by solving Poisson’s equation:

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity and εr is the relative permittivity that compensates for electronic and ionic polarization under high electric fields. During the electron multiplication process, the accumulation of Elocal inevitably causes the electric energy of excited electrons Welec to rise, where Welec is calculated by the following equation: \({{W}}_{{{\rm{elec}}}}={\int }_{{V}}\frac{1}{2}{{\varepsilon }}_{{0}}{{\varepsilon }}_{{r}}{{E}}_{{{\rm{local}}}}{({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}},{t})}^{2}{d}V\). High Welec would weaken the binding effect of the chemical bond on excited electrons. As a result, when Welec exceeds the critical energy, the third stage of bond breakage may happen, as shown in Fig. 1c. Unlike previous multi-scale breakdown models63,64, which typically treat bond breakage as thermally activated process initiated by electron-assisted defect generation, here our model couples the chemical bond dissociation with the accumulation of Welec, enabling tracks the local bond breaking behavior that is regarded as the key factor to determine the stability and insulation of the dielectrics65. While the thermochemical model proposed by McPherson related the breakdown strength (Eb) to the bond energy (Wb) through an analytical expression33, it does not precisely address the atomic-scale complexity of the dynamic but asynchronous bond-breaking process that is highly dependent on the localized electron accumulation and non-equilibrium excitation under high electric fields. To account for the differences in bond breaking at different atomic positions, we assume that once Welec at a certain point exceeds the critical energy, the chemical bond would be broken and the discharging occurs simultaneously, as shown in Fig. 1c. Then, free electrons released from the bond breakage continue to break nearby bonds in a dynamic chain reaction process. Here, based on the fractal dimension breakdown model14, the probability p of the bond breakage from one initial broken bond position (r) to the adjacent bond position (r’) is defined as follow:

where \({{W}}_{elec}^{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{{\hbox{'}}}}}}}\) is the electric energy of excited electrons in possible broken bond position, Wb is the bond energy which describes the critical value of the bond breakage (about 2 ~ 10 eV for X-O bond60, where O is oxygen atom and X represents possible atoms, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S11), and ξ is the fractal dimension determining the shape characteristic of the avalanche paths (see Supplementary Note S10 and Fig. S12). Here, ξ is set to 1, that is, the bond breaking probability is linearly related to the local electric energy.

As the bond-breaking chain reaction proceeds, the localized density of broken bonds and thus activated electrons increase to a sufficiently high level to form a conductive percolation channel, as the fourth stage shown in Fig. 1d. Thus, the dynamic evolution of the electron avalanche path could be achieved by capturing the bond-breaking behavior caused by high localized electron density. Here, extending from the continuous model for conductive electrical tree growth in dielectrics66, we use a normalized variable η(r, t) to describe the dynamic evolution of avalanche channel in the rate equation:

The first two terms determine the difficulty and tendency of bond breaking, and the last term is related to the bond properties of the dielectrics. The coefficients A, B and C are the positive constants and decide the weight of each term in the equation. To emphasize the role of local electrons in bond breaking, the coefficient C is set to the bond breaking probability p with both A and B of 0. The effects of A and B on the breakdown process are also investigated in Supplementary Note S11 and Fig. S13. The simulations are carried out in two dimensions (2D) with the size of 15 × 15 lattices (~6 nm). Here, we define that the electron avalanche breakdown has approximately completed when the longitudinal length of the conductive channel is up to ~6 nm, because this value is comparable to the electron mean free path of conductive metals67,68. When the electron avalanche path is larger than ~6 nm, subsequent avalanche processes is out of control and the insulating dielectric would turn into a (semi)conductor in an instant. In addition, to compare the size effect on the breakdown behavior, we also study the electron avalanche breakdown process in dielectrics with different thicknesses (see Supplementary Note S12 and Fig. S14). The control equations are solved by finite element simulations using the commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics 5.6, with a spatial and temporal resolution of 0.1 Å and 0.01 ps.

Data availability

All data used are available within this paper and Supplementary Information. Further information can be acquired from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Seitz, F. On the theory of electron multiplication in crystals. Phys. Rev. 76, 1376 (1949).

Palumbo, F. et al. A review on dielectric breakdown in thin dielectrics: silicon dioxide, high-k, and layered dielectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1900657 (2020).

Shekhawat, A., Papanikolaou, S., Zapperi, S. & Sethna, J. P. Dielectric breakdown and avalanches at nonequilibrium metal-insulator transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 276401 (2011).

Zhang, M. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage in high-entropy ceramic capacitors with polymorphic relaxor phase. Science 384, 185–189 (2024).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Giant energy storage and power density negative capacitance superlattices. Nature 629, 803–809 (2024).

Han, S. et al. High energy density in artificial heterostructures through relaxation time modulation. Science 384, 312–317 (2024).

Privitera, S., Bersuker, G., Lombardo, S., Bongiorno, C. & Gilmer, D. Conductive filament structure in HfO2 resistive switching memory devices. Solid-State Electron 111, 161–165 (2015).

Lanza, M. et al. Memristive technologies for data storage, computation, encryption, and radio-frequency communication. Science 376, eabj9979 (2022).

Gonzales, C. & Guerrero, A. Mechanistic and kinetic analysis of perovskite memristors with buffer layers: the case of a two-step set process. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 1395–1402 (2023).

Shi, Y. et al. Electronic synapses made of layered two-dimensional materials. Nat. Electron. 1, 458–465 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Scalable integration of hybrid high-κ dielectric materials on two-dimensional semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 22, 1078–1084 (2023).

Von Hippel, A. Electric breakdown of solid and liquid insulators. J. Appl. Phys. 8, 815–832 (1937).

Frohlich, H. On the theory of dielectric breakdown in solids. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. 188, 521–532 (1947).

Niemeyer, L., Pietronero, L. & Wiesmann, H. J. Fractal dimension of dielectric breakdown. Phys. Rev. Lett. 52, 1033 (1984).

Chaitanya Pitike, K. & Hong, W. Phase-field model for dielectric breakdown in solids. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 044101 (2014).

Shen, Z. H. et al. High-throughput phase-field design of high-energy-density polymer nanocomposites. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704380 (2018).

Pan, H. et al. Ultrahigh energy storage in superparaelectric relaxor ferroelectrics. Science 374, 100–104 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Chemical framework to design linear-like relaxors toward capacitive energy storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3498–3507 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Giant energy-storage density with ultrahigh efficiency in lead-free relaxors via high-entropy design. Nat. Commun. 13, 3089 (2022).

Pan, H. et al. Ultrahigh–energy density lead-free dielectric films via polymorphic nanodomain design. Science 365, 578–582 (2019).

Yang, B. et al. High-entropy enhanced capacitive energy storage. Nat. Mater. 21, 1074–1080 (2022).

Elder, K., Katakowski, M., Haataja, M. & Grant, M. Modeling elasticity in crystal growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 245701 (2002).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Shibata, N. et al. Electric field imaging of single atoms. Nat. Commun. 8, 15631 (2017).

Goh, E., Ong, L., Yoon, T. & Chew, K. Structural and response properties of all BaTiO3 phases from density functional theory using the projector-augmented-wave methods. Comput. Mater. Sci. 117, 306–314 (2016).

Jabar, B. et al. Homo-composition and hetero-structure nanocomposite Pnma Bi2SeS2-Pnnm Bi2SeS2 with high thermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 12, 7192 (2021).

Steinhögl, W., Schindler, G., Steinlesberger, G. & Engelhardt, M. Size-dependent resistivity of metallic wires in the mesoscopic range. Phys. Rev. B 66, 075414 (2002).

Chawla, J., Zhang, X. & Gall, D. Effective electron mean free path in TiN (001). J. Appl. Phys. 113, 063704 (2013).

Song, D. et al. High-k perovskite gate oxide for modulation beyond 1014 cm−2. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm3962 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Perovskite lead-free dielectrics for energy storage applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 102, 72–108 (2019).

Yu, Y. et al. Structure-evolution-designed amorphous oxides for dielectric energy storage. Nat. Commun. 14, 3031 (2023).

Neusel, C. & Schneider, G. A. Size-dependence of the dielectric breakdown strength from nano-to millimeter scale. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 63, 201–213 (2014).

McPherson, J. W., Kim, J., Shanware, A., Mogul, H. & Rodriguez, J. Trends in the ultimate breakdown strength of high dielectric-constant materials. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 50, 1771–1778 (2003).

Liu, J. et al. Influence of dielectric constant on dielectric strength by defect discharge and molecular polarization in solid insulation materials. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 115103 (2019).

Kim, C., Pilania, G. & Ramprasad, R. From organized high-throughput data to phenomenological theory using machine learning: the example of dielectric breakdown. Chem. Mat. 28, 1304–1311 (2016).

Yasuoka, S. et al. Effects of deposition conditions on the ferroelectric properties of (Al1−xScx) N thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 114103 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Giant energy density nitride dielectrics enabled by a paraelectric-metaparaelectric phase transition. Nat. Commun. 16, 3191 (2025).

Yao, Z. et al. Homogeneous/inhomogeneous-structured dielectrics and their energy-storage performances. Adv. Mater. 29, 1601727 (2017).

Hu, H. et al. Recent advances in rational design of polymer nanocomposite dielectrics for energy storage. Nano Energy 74, 104844 (2020).

Prateek, Thakur, V. K. & Gupta, R. K. Recent progress on ferroelectric polymer-based nanocomposites for high energy density capacitors: synthesis, dielectric properties, and future aspects. Chem. Rev. 116, 4260–4317 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Strain-induced anion-site occupancy in perovskite oxyfluoride films. Chem. Mat. 33, 1811–1820 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Large enhancement of ferroelectric properties of perovskite oxides via nitrogen incorporation. Sci. Adv. 11, eads8830 (2025).

Mu S. et al. Uncovering electron scattering mechanisms in NiFeCoCrMn derived concentrated solid solution and high entropy alloys. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 1 (2019).

McPherson, J. Determination of the nature of molecular bonding in silica from time-dependent dielectric breakdown data. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 8101–8109 (2004).

Boyle, C. J. et al. Tuning charge transport dynamics via clustering of doping in organic semiconductor thin films. Nat. Commun. 10, 2827 (2019).

Blavette, D. & Duguay, S. Investigation of dopant clustering and segregation to defects in semiconductors using atom probe tomography. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 181502 (2016).

Ma, Y. et al. High-entropy energy materials: challenges and new opportunities. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2883–2905 (2021).

Schweidler, S. et al. High-entropy materials for energy and electronic applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 266–281 (2024).

Yang, B. et al. Engineering relaxors by entropy for high energy storage performance. Nat. Energy 8, 956–964 (2023).

Yang, B. et al. High-entropy design for dielectric materials: Status, challenges, and beyond. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 110904 (2023).

Gao, Y. et al. Optimizing high-temperature energy storage in tungsten bronze-structured ceramics via high-entropy strategy and bandgap engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 5869 (2024).

Sun, Y., Yang, J., Li, S. & Wang, D. Defect engineering in perovskite oxide thin films. Chem. Commun. 57, 8402–8420 (2021).

Pabst, G. W., Martin, L. W., Chu, Y.-H. & Ramesh, R. Leakage mechanisms in BiFeO3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 072902 (2007).

Chiu, F.-C. A review on conduction mechanisms in dielectric films. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 578168 (2014).

Pan, H. et al. Enhanced electric resistivity and dielectric energy storage by vacancy defect complex. Energy Storage Mater. 42, 836–844 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Femtosecond visualization of oxygen vacancies in metal oxides. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax9427 (2020).

Sangalli, D. et al. Role of oxygen vacancies on the structure and density of states of iron-doped zirconia. Phys. Rev. B 87, 085206 (2013).

Kang, I. J. & Foland, W. D. Theory of electron impact excitation and ionization of atoms and ions. Phys. Rev. 164, 122 (1967).

Kingston, A. E. Excitation and ionization of hydrogen atoms by electron impact. Phys. Rev. 135, A1529 (1964).

Haynes W. M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 97th edn (CRC Press, 2016).

Holway, J.rL. H. & Fradin, D. Electron avalanche breakdown by laser radiation in insulating crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 46, 279–291 (1975).

Ruedenberg, K. Atoms and bonds in molecules as synergisms of interactions between electrons and nuclei. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 210901 (2022).

Padovani, A., Gao, D., Shluger, A. & Larcher, L. A microscopic mechanism of dielectric breakdown in SiO2 films: in insight from multi-scale modeling. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 155101 (2017).

Strand, J., La Torraca, P., Padovani, A., Larcher, L. & Shluger, A. L. Dielectric breakdown in HfO2 dielectrics: Using multiscale modeling to identify the critical physical processes involved in oxide degradation. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 234501 (2022).

Li, X., Tung, C. & Pey, K. The nature of dielectric breakdown. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 072903 (2008).

Zhao, L. A mathematical model for conductive electrical tree growth in dielectrics—part I: theory. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 29, 1353–1360 (2022).

Gall, D. Electron mean free path in elemental metals. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 085101 (2016).

Penn, D. R. Electron mean-free-path calculations using a model dielectric function. Phys. Rev. B 35, 482 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Basic Science Center Program of NSFC (Grant No. 52388201, C.-W.N.), the NSF of China (Grant No. 52422206, 52372121 and 52002300, Z.-H.S.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFB3812200, H.-X.L.), the Major Research Plan of NSFC (Grant No. 92066103, Z.-H.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

These authors contributed equally: J.W. and Z.-H.S. J.W., Z.-H.S. and C.-W.N. conceived and designed the research. W.L. prepared the ceramic films. R.-L.L. established the machine learning model. Y.-L.D. performed the density functional theory calculations. Z.-H.S. and C.-W.N. reviewed and edited the paper with contributions from Y.S. and H.-X.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Victor Lopez-Richard, Gaetano Calogero, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Shen, ZH., Li, W. et al. Dynamic atomic-scale electron avalanche breakdown in solid dielectrics. Nat Commun 16, 6465 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61866-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61866-z