Abstract

In plants, the developing cell plate which is characterized by a series of anionic lipids, undergoes dramatic morphological change for successful cytokinesis. However, the mechanisms underlying these alterations, and the roles of anionic lipids such as phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), and phosphatidylserine (PS) during cell division remain poorly understood. Here we present that changes in anionic lipid composition have a profound effect on cell plate development: deprivation of phosphatidylinositides (PIPs) leads to incomplete cytokinesis through distorted cell-plate architecture. Our data demonstrate that PI4P shapes cell plate membrane morphology through flippase-regulated PS flipping inhibition, while PI(4,5)P2 functions in the recruitment of dynamin-related protein 1A (DRP1A) and the constriction region formation; depletion of PIPs causes cell plate tubulation and flattening failure. We propose a model in which PI4P regulates the level and distribution of PS, while PI(4,5)P2 mediates the localization of DRP1A; together, they coordinate cell plate morphology to ensure successful cytokinesis in plant cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plant cells possess complicated endomembrane systems and employ intracellular membrane components for cell division, represented as centrifugal expansion of cell plates. Cell plate assembly is facilitated by guided vesicle trafficking along the phragmoplast, which is composed of microtubules and actin filaments positioned perpendicular to the division plane1. Homotypic fusion of vesicles from the secretory pathway is essential for this process, and involves components such as KNOLLE, KEULE, and vesicle-associated membrane protein 721/722 (VAMP721/722)2,3,4. Golgi-derived vesicles fuse at the division plane to form an hourglass-shaped vesicle intermediate, which is stretched to form dumbbells that fuse to form the tubulovesicular network. The tubulovesicular network gives rise to the tubular network, later maturing into a planar fenestrated sheet at the center of the developing cell plate5,6. Callose is then deposited into the lumen of the interconnected tubular network for stabilization7. The tubulation process is facilitated by dynamin-related protein 1A (DRP1A/ADL1A)8,9 and the BAR domain-containing protein SH3 Domain-Containing Protein 2 (SH3P2), which both localize at the constricted region of membrane tubules10,11. Although the structural progression of cell plate formation has been characterized, the regulatory factors and signaling pathways governing the associated morphological transitions remain poorly understood.

As part of the endomembrane system, the cell plate has unique lipid features and protein composition. Anionic lipids like phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P), and diacylglycerol (DAG) are present throughout cell plate expansion, while phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) is found at late stage when the cell plate is partially attached to the parental plasma membrane (PM)12,13. It is well established that the lipid composition of the outer leaflet, also called the exoplasmic leaflet, of the PM differs from the inner, or the cytoplasmic leaflet14,15. PM transbilayer lipid asymmetry is achieved through lipid transportation by flippases (out-to-in pumps), floppases (in-to-out pumps), and scramblases (rapid bidirectional flip-flop translocator). Flippases and floppases establish PM asymmetry by ATP-driven transportation of PS and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to the cytoplasmic leaflet and phosphatidylcholine (PC) to the exoplasmic leaflet, while scramblases disrupt this asymmetry14. Sphingomyelin (SM)-rich lipid domains in the outer leaflet have been shown to colocalize with inner leaflet PI(4,5)P2-rich domains at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis in mammalian cells16. The mechanisms underlying the biophysical association of transbilayer lipids remain unclear, and the functional role of interleaflet lipid coupling is yet to be elucidated. Furthermore, the function and regulation of lipid asymmetry in other endomembrane structures, such as the cell plate, remain largely unexplored.

Among the anionic lipids, phosphoinositides (PIPs) are key molecules that regulate signal transduction, membrane trafficking, and cytoskeleton organization through direct interaction with membrane proteins or recruitment of PIP binding proteins17. PI4Kβ has been shown to regulate membrane trafficking and phragmoplast dynamics during cytokinesis18, and the polar depletion of PI(4,5)P2 at the final stage of cytokinesis has been reported to guide the cell plate attachment19. However, our understanding of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 during cell plate formation remains limited. This is partly because it is challenging to study a specific PI species by genetically manipulating certain PI metabolizing enzymes without affecting other PI species in the metabolic network. Moreover, compensatory adaptive changes of other PI metabolizing enzymes in the long-term range would complicate the results further20. In addition, genes encoding phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatases are highly redundant in plants, making genetic analysis more challenging. As the substrate for PI synthesis, disruption of de novo inositol synthesis can induce PI deficiency, and subsequent PM integrity and endomembrane trafficking defects21. D-myo-inositol-3-phosphate synthase (MIPS) catalyzes the rate-limiting step of inositol synthesis. In addition to PIPs, other inositol derivatives, such as inositol phosphates and inositol pyrophosphates, have been reported to act as intracellular signaling messengers, enzyme co-factors, and phosphorous storage22,23. Knocking out MIPS genes in Arabidopsis could cause diverse defects, including anthocyanidin accumulation21, programmed cell death21,24, impaired pattern formation and auxin transport21,25, defective in pathogen resistance26 and stress response27, etc. Here we show that cell plate tubulation and flattening were impaired in the MIPS double mutant mips1 mips3, due to deficiency in PI4P and PI(4,5)P2. Knocking out the flippase gene Aminophospholipid ATPase 1 (ALA1) or overexpressing the dynamin gene DRP1A could rescue the incomplete cytokinesis in mips1 mips3, suggesting the involvement of cytoplasmic aminophospholipid, such as PS level, and DRP1A in PIPs-mediated cell plate development. Furthermore, transient inhibition of PI4P increased cytosolic PS level and induced phenotypes such as cell plate bulges, PM invaginations, and incomplete cytokinesis, similar to those observed in mips1 and mips3. Transient deprivation of PI(4,5)P2 reduced DRP1A aggregation at the cell plate. These results indicate that inhibition of PI4P-dependent lipid flipping, together with PI(4,5)P2-dependent DRP1A recruitment, regulates cell plate morphology during cytokinesis. Our findings provide insights into the roles of anionic lipids in membrane curvature regulation during cell plate formation, revealing implications for the morphology modulation of various plant endomembrane compartments.

Results

PIPs deficient mutant mips1 mips3 shows incomplete cytokinesis

To investigate the role of cell plate localized PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 in cell plate formation, the mips1 mips3 double mutant in which both PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 levels were significantly reduced compared to that in the wild type (Supplementary Fig. 1) was used. mips1 and mips3 show greatly decreased root length compared to wild type control when grown on an inositol-free medium (Fig. 1a, b). The short root phenotype can be partially rescued by exogenous application of inositol (Fig. 1a, b). The mips1 mips3 seedlings analyzed in this study were grown on medium without inositol unless indicated. To check whether the short root phenotype is caused by defective cell division, the centromere marker HTR12-GFP28 was introduced into wild type and mips1 mips3 mutant plants. Confocal microscopy showed that the numbers of fluorescent foci did not exceed ten (2n) in most wild type root tip cells, while a significant fraction of mips1 mips3 cells had more than ten HTR12-GFP foci, indicating that frequent endoreduplication occurred in mips1 mips3 (Fig. 1c, d). Similar features, including enlarged nuclei and increased ploidy, have been observed in cytokinesis mutants such as knolle and keule29, likely representing secondary effects of impaired cytokinesis, potentially due to nuclear fusion or failure to properly reset cell cycle checkpoints. Further analysis using FM 4-64 staining of PM demonstrated that mips1 mips3 seedlings grown on inositol-free medium showed thick cell wall stubs, which were absent in the wild type and mips1 mips3 seedlings supplied with inositol (Fig. 1e), suggesting incomplete cytokinesis upon inositol depletion. The short root and incomplete cytokinesis phenotypes of mips1 mips3 could be fully complemented by expressing the native promoter-driven MIPS1 gene (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). Z-stack scanning and 3D reconstruction of FM 4-64 labeled developing cell plate showed that, unlike the disc shape in the wild type, a donut-shaped cell plate was formed in the mips1 mips3 roots (Fig. 1f). Time series analysis demonstrated that as the GFP-TUB6 labeled30 microtubule bundles representing phragmoplast moved centrifugally, the FM 4-64 labeled cell plate expanded smoothly in the wild type (Supplementary Movie 1), but in the mips1 mips3 root cells, the cell plate at the center was not stabilized, leaving an expanding hole in the middle of the cell plate (Supplementary Movie 2). The phragmoplast consists of two sets of parallel microtubules that formed during late telophase, and expanded laterally until they reached the PM of the parental cell (Supplementary Movie 3). The whole process usually took around 30 min (32 ± 3.209 min [SEM; n = 5]) for the wild type root cells (Supplementary Fig. 2c). In mips1 mips3, however, cytokinesis took much longer (75.4 ± 7.104 min [SEM; n = 5]) (Supplementary Fig. 2c), and phragmoplast dynamics were characterized by slower and asynchronous expansion (Supplementary Movie 4), which might serve as a protective mechanism to repair the incomplete cell plate. Our observations suggest an aberrant cell plate formation in mips1 mips3 mutant.

a Representative images of 5 DAG wild type and mips1 mips3 seedlings grown without or with 0.1 or 0.5 g/L inositol. Scale bar: 5 mm. b Quantification of root length under the same conditions. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (wild type: -inositol, n = 22; 0.1 g/L inositol, n = 28; 0.5 g/L inositol, n = 35. mips1 mips3: -inositol, n = 28; 0.1 g/L inositol, n = 25; 0.5 g/L inositol, n = 29). n.s. P = 0.9676; *** P < 0.0001. c Representative 3D projection images of HTR12-GFP-labeled root epidermal cells (10 DAG). Dots represent centromeres. Red asterisk indicates polyploid macronuclei. Scale bars: 5 μm. d Quantification of endoreduplication for each genotype (n = 5 roots, >50 cells analyzed in total). Two-tailed Student’s t-test, *** P < 0.0001. e FM 4-64-stained root epidermal cells show incomplete cell walls (white arrows) and thickened stubs (white arrowheads) in mips1 mips3 grown without inositol. Scale bars: 10 μm. The experiment was repeated more than three times with similar results. f 3D projections of cell plates (top) and cell walls (bottom). Black arrow indicates donut-shaped cell plate in mips1 mips3; white arrow points to a hole between neighboring cells. Scale bars: 5 μm. g Representative TEM images of dividing root epidermal cells at the disk and discontinuous phragmoplast stages. Red arrows show swollen, incomplete cell plates with gaps; red arrowheads highlight unfused vesicles. n: nucleus. Scale bars: 0.5 μm or 1 μm. h Quantification of cell plate thickness as shown in (g) (wild type, n = 76; mips1 mips3, n = 73) from >10 cells per genotype. For each cell plate, thickness was measured at 5 to 6 evenly spaced positions along the lagging zone. Two-tailed Student’s t-test, *** P < 0.0001. Data in (b, d, h) are shown as box and whisker plots with individual points, representing three experimental replications with similar results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further investigate the cell plate formation, transmission electron microscope (TEM) was employed. The result showed that at the disk phragmoplast stage, vesicles fused at the division plane to form the tubulovesicular network in wild type (left upper panel of Fig. 1g); on the contrary, large vesicles derived from the cytokinetic vesicle fusion were observed in mips1 mips3 (middle upper panel of Fig. 1g). Additionally, accumulation of unfused vesicles in the division plane was occasionally observed in mips1 mips3 cells (right upper panel of Fig. 1g). At the discontinuous phragmoplast stage when the cell plate partially attached to the PM, unlike the continuous fenestrated sheet found in the wild type (left lower panel of Fig. 1g), cell plates in mips1 mips3 turned swollen at the leading edge and segmented (middle lower panel of Fig. 1g), and in some cases, two daughter nuclei were in direct contact due to incomplete cell plate formation (right lower panel of Fig. 1g). Cell plates are significantly thicker in mips1 mips3 (0.232 ± 0.022 μm [SEM; n = 76]), than that of the wild type (0.114 ± 0.006 μm [SEM; n = 73]) (Fig. 1h). Meanwhile, FM 4-64 staining revealed various cell plate phenotypes in mips1 mips3, including discontinuous, swollen, and branched cell plates, as well as irregular membrane accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 3). Confocal and TEM analyses revealed that mips1 mips3 exhibits defects at multiple stages of cell plate development, including early vesicle fusion and membrane bridging, as well as late-stage flattening and morphological organization. Unlike many cytokinesis mutants that primarily impair early-stage vesicle fusion18,31, mips1 mips3 predominantly exhibits pronounced morphological defects, including discrete spheroids, thickened and branched cell plates, whereas defects in cell plate orientation are rarely observed compared to mutants such as rsw99 and knolle29, highlighting a key role for PIPs in regulating late-stage structural organization. These together suggest that a cell plate morphology regulation defect occurred in the mutant without exogenous inositol application, and the reduction of PIPs most likely causes the cell plate defect.

Knocking out ALA1 suppresses the cytokinesis phenotype of mips1 mips3

A suppressor screen by EMS mutagenesis of mips1 mips3 was carried out to identify the components involved in the cytokinesis phenotype. An M2 population derived from self-fertilized M1 plants was used for mutant screening. Over 100 candidate plants with roots over twice the length of mips1 mips3 were obtained. A mutant designated VLR_95 showed significantly increased root length and a greatly recovered incomplete cytokinesis phenotype was identified, although the cell division pattern was somewhat impaired (Fig. 2a–c, e, f and Supplementary Fig. 4a). The causative mutation was identified by bulked segregant analysis (BSA), coupled with deep gene sequencing. Manhattan plot analysis from BSA-seq located the candidate region on chromosome 5, demonstrating strong linkage disequilibrium with neighboring loci (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The candidate region contains 5 nonsynonymous substitutions and one stop gain mutation of coding genes. The stop gain mutation occurs in the first exon of the ALA1 gene, leading to a truncated protein of 293 amino acids, compared to 1158 amino acids in the normal protein (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Disruption of the ALA1 gene by T-DNA insertion (SALK_002106 and SALK_056947) significantly increased the root length of mips1 mips3 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Additionally, overexpressing ALA1 decreased the root length of VLR_95 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Similar to VLR_95, T-DNA insertion of ALA1 in the mips1 mips3 background significantly rescued the incomplete cytokinesis phenotype of mips1 mips3, although it increased defects in cell division orientation (Fig. 2c, e, f). In contrast, expression of ALA1 in the VLR_95 background phenocopied the cytokinesis defects observed in mips1 mips3 (Fig. 2c, e, f). Overall, genetic results confirmed that ALA1 is the causative gene of VLR_95.

a Root lengths of 7 DAG wild type, mips1 mips3, and EMS mutant VLR_95 seedlings grown without inositol were compared. Scale bar: 1 cm. b Quantification of root length across wild type, mips1 mips3, VLR_95, SALK_002106/mips1 mips3, SALK_056947/mips1 mips3, and VLR_95/ALA1 (n = 10 each; including two independent VLR_95/ALA1 lines). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (****P < 0.0001). The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. c Representative views of root cells stained with FM 4-64. For each genotype, more than 30 roots were analyzed, and consistent results were obtained across all samples. White arrows indicate incomplete cell walls. Scale bar: 10 μm. d ALA1-GFP fluorescence overlapped with FM 4-64 signal at the plasma membrane and cell plate. Scale bar: 5 μm. Consistent results were obtained from two independent experiments using more than five individual transgenic lines. e Cell wall stub frequency was quantified in root epidermal cells stained with FM 4-64 (n = 12 roots per genotype; 10 to 20 cells were analyzed for each root). One-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons was used for statistical analysis. The data are from one of two comparable experiments. f, The incidence of “cell wall orientation defects” was quantified in root epidermal cells of the same genotypes (n = 12 roots per genotype; 10 to 20 cells were analyzed for each root) stained with FM 4-64. Statistically significant differences between groups in b, e, f (P < 0.05) are indicated by distinct letters. Data in b, e, f are displayed as box and whisker plots. Box plots represent the median, 1st and 3rd quartiles; whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. All individual data points are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

ALA1 is a putative type 4 ATPase that transports aminophospholipids from the exoplasmic to the cytoplasmic leaflet of the membrane bilayer32,33,34. Accordingly, we conducted a subcellular localization analysis to determine where ALA1 functions within the cell. The results demonstrated that ALA1-GFP resides on the PM and cell plate of root epidermal cells (Fig. 2d). TEM result showed that the cell plate thickness of the disk phragmoplast stage was significantly reduced in VLR_95 compared to mips1 mips3 (Fig. 3a, b), demonstrating ALA1 mutation alleviates cell plate defects in mips1 mips3. The ALA1 protein is predicted to contain ten transmembrane domains (TMD) and two cytoplasmic loops (Supplementary Fig. 5a)35,36. Given that PIPs levels are markedly reduced in mips1 mips3, we next investigated whether ALA1 might functionally interact with PIPs to modulate cell plate formation. To decipher the relationship between ALA1 and PIPs, we expressed both loop sequences and the C-terminal domain, and tested their lipid binding abilities in vitro. Western blot analysis confirmed correct expression and expected molecular weights of the target fragments (Supplementary Fig. 5b). We assessed the binding affinities of ALA1 fragments to liposomes containing different phospholipids using Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI). The ALA1 Loop1 (151–329 aa) exhibited the strongest binding to PS liposomes, followed by PI4P liposomes, with minimal interaction observed with PI(4,5)P2, PI5P, and PI3P liposomes (Fig. 3c). For ALA1 Loop2 (410–914 aa), the highest near-steady-state binding was observed with PS, PI4P and PI5P liposomes, which significantly exceeded its binding to PI(4,5)P2 and PI3P liposomes (Fig. 3d). While potential contributions from nonspecific electrostatic interactions exist, the observed binding of ALA1 loops to anionic lipids such as PS and PI4P appears primarily indicative of lipid-selective interactions. However, the C-terminal domain of ALA1 did not exhibit binding to any of the liposomes tested (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Kinetic analysis of the binding between ALA1 cytosolic loops and PI4P-containing liposomes revealed apparent dissociation constant (KD) values of 6.048 μM for Loop1 and 2.212 μM for Loop2 (Fig. 3e, f). Additionally, we also performed a lipid overlay assay, although it is generally considered less sensitive and reliable than BLI. The results demonstrated that both loops directly bound to all PIPs, but not to PI or other phospholipids (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). Consistently, the C-terminal domain did not bind to any of the lipids tested (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Our findings reveal that the ALA1 cytosolic loops exhibit high-affinity binding to PI4P and PS, suggesting that these lipids may function as potential regulators or substrates of ALA1.

a Representative TEM image showing the developing cell plate at discontinuous phragmoplast stage of root epidermal cells of 5 DAG VLR_95. Scale bar: 2 μm. b Quantitative analysis of cell plate thickness shows a significant reduction in VLR_95 compared to mips1 mips3. Cell plates from 5 discontinuous phragmoplast stage root cells of each genotype were analyzed. For each cell plate, thickness measurements were taken at more than 6 evenly spaced positions along the lagging zone. mips1 mips3, n = 33; VLR_95, n = 34. Statistical differences were determined using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. ***P = 0.0001. c, d Binding affinity of ALA1 cytosolic loops to PS and PIPs analyzed by BLI. The phospholipid-binding specificities of ALA1 cytosolic Loop1 (151–329 aa) (c) and Loop2 (410–914 aa) (d) are shown. Specific binding levels were calculated by subtracting background binding to POPC liposome control. Representative data from two independent experiments are presented. e, f Kinetics of PI4P-specific binding by ALA1 cytosolic loops. Time-course analyses of PI4P-specific binding by ALA1 Loop1 (151–329 aa) (e) and Loop2 (410–914 aa) (f) are shown, with 0 nM target protein control subtracted. Binding was measured at protein concentrations ranging from 100 nM to 400 nM. Global fitting of the binding kinetics (red lines) yielded dissociation constant KD values. Representative data from two independent experiments are presented. Data in (b) are displayed as box and whisker plots. Box plots represent the median, 1st and 3rd quartile; the whiskers represent maximum and minimum values. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Knockout of the ALA1 gene rescued the incomplete cytokinesis and thickened cell plate phenotypes observed in mips1 mips3. These findings point to the prospect that inhibiting phospholipid translocation to the cytoplasmic leaflet can mitigate the cell-plate defect, suggesting a role for membrane asymmetry in cell-plate formation.

Cell plate development requires PI4P-mediated membrane morphology regulation

To elucidate how ALA1 contributes to cell plate development, we began by determining its lipid substrate. Initial studies in yeast demonstrated that ALA1 could translocate fluorescent PS at the PM and complement the cold-sensitive phenotype of yeast drs2 mutant34. However, subsequent research demonstrated that ALA1 failed to complement a yeast triple mutant deficient in P4 ATPases responsible for PS transport, raising doubts about whether PS serves as the substrate for ALA1 in the yeast system37,38. On the other hand, phosphoinositide species have been reported to modulate transmembrane channel/transporter activity, leading to compartment-specific or stimuli-dependent activation39,40,41,42. The PM environments differ between yeast and plant cells; for example, PI4P predominantly localizes to the PM in plant cells, whereas its major pool resides at the TGN in yeast43. Therefore, we analyzed ALA1 flippase activity at the PM of Arabidopsis root epidermal cells within a biologically more relevant context. To determine whether ALA1 facilitates the flipping of PS, we conducted a phospholipid uptake assay utilizing 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-labeled phosphatidylserine (NBD-PS)44,45. After a 1-h incubation with NBD-PS, the ALA1 knockout mutant SALK_002106 exhibited significantly reduced uptake compared to the wild type, providing evidence that ALA1 mediates NBD-PS transport in Arabidopsis root cells (Fig. 4a, c). Significantly elevated NBD-PS uptake was observed in the mips1 mips3 mutant, which is deficient in PIPs. Mutation of ALA1 in mips1 mips3 restored NBD-PS uptake to wild type levels, further supporting the involvement of ALA1 in PS flipping (Fig. 4a, c). Together, these findings demonstrate that ALA1 flips PS at the Arabidopsis PM and is regulated by membrane PIPs.

a Representative confocal images of root epidermal cells from wild type, mips1 mips3, VLR_95, and SALK_002106 following NBD-PS treatment; acquired under identical confocal settings. Scale bars: 5 μm. b Wild type roots treated with PAO for 1 h prior to NBD-PS labeling were imaged under the same settings. c NBD-PS fluorescence was quantified using fixed ROIs (wild type, n = 22; mips1 mips3, n = 20; VLR_95, n = 23; SALK_002106, n = 21; PAO-treated wild type, n = 20; one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons; distinct letters: P < 0.05; **P = 0.0064, ****P < 0.0001). d Super-resolution confocal images of dividing cells labeled with EGFP-C2LACT. Scale bar: 10 μm. e Quantification of EGFP-C2LACT signal intensity in VLR_95 (n = 15) and mips1 mips3 (n = 15); two-tailed t test, **P = 0.0014. f Super-resolution confocal images show PS-free domains (arrowheads) in wild type cell plates, whereas mips1 mips3 exhibits more uniform PS signal (n = 15 per genotype). Scale bar: 1 μm. g PS distribution heterogeneity in mips1 mips3 (n = 14) and wild type (n = 14), evaluated by coefficient of variation. Two-tailed t test, **P = 0.0011. h Relative EGFP-C2LACT signal intensity at late-stage cell plates in mips1 mips3 (n = 13) compared to wild type (n = 14); two-tailed t test, **P = 0.0089. i Dual-color super-resolution imaging of CITRINE-2xPHFAPP1 and mChe-C2LACT following DMSO or PAO treatment (representative of >6 replicates). Scale bars: 5 μm. j Super-resolution confocal images showing incomplete cytokinesis (white arrowheads, left), cell plate branching (blue arrowheads, left) and membrane invaginations or bulges (purple arrowheads, right) in wild type root epidermal cells following PAO and NBD-PS treatments. Scale bars: 10 μm. k–n Quantification of CITRINE-2xPHFAPP1 or mChe-C2LACT fluorescent signals at the PM or cell plate as indicated (n = 6 dividing cells, two-tailed t-test; ***P = 0.0007 (k), ***P = 0.0001 (l), n.s. P > 0.05). Repeated three times with similar results. a.u. = arbitrary units. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

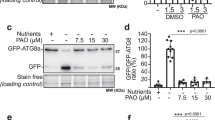

We next examined the regulatory influence of individual phosphoinositides on ALA1 activity. The S. cerevisiae homolog of ALA1, Drs2p, is regulated through autoinhibition by its C-terminal tail and directly activated through binding with PI4P46,47. Protein structure alignment of Drs2p and ALA1 shows significant similarity, except that the two cytosolic tails are hardly aligned (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b)48. The C-terminal tail of ALA1 contains only 42 amino acids compared to the 132 amino acids in Drs2p, suggesting a lack of the autoinhibitory and PI4P activation domains in ALA1 (Supplementary Fig. 6c). PIPs deficiency in mips1 mips3 increased NBD-PS uptake, suggesting that PIPs play an inhibitory rather than an activating role in the regulation of ALA1 activity. Given that PI4P exhibited the strongest binding to both cytosolic loops of ALA1 compared to other PIPs, and knocking out ALA1 could rescue the cytokinesis phenotype of PI4P deficient mips1 mips3, we hypothesized that PI4P might inhibit ALA1 activity and reduce cytoplasmic leaflet PS level at the cell plate for successful cytokinesis. We further employed phenylarsine oxide (PAO), a PtdIns(4) kinase (PI(4)K) inhibitor, to investigate the effect of transient PI4P depletion49. PS uptake in wild type root cells was markedly elevated after 1 h of PAO treatment followed by NBD-PS incubation (Fig. 4b, c), suggesting an inhibitory role of PI4P on NBD-PS flipping.

To investigate in vivo PS levels, we used fluorescence PS marker EGFP-C2LACT 50 and observed that VLR_95, which lacks ALA1, exhibited reduced cytoplasmic PS levels at the cell plate compared to mips1 mips3 (Fig. 4d, e), providing further evidence for the role of ALA1 in PS flipping at the cell plate. Next, the PS level and distribution pattern at the cell plate were investigated employing a super-resolution confocal microscope. For wild type, PS was distributed discontinuously along the lagging zone of the expanding cell plate, while mips1 mips3 showed reduced heterogeneity for PS distribution (Fig. 4f, g and Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating that local PS flipping inhibition in wild type is lost in mips1 mips3 upon PIPs depletion. Fluorescence intensity of PS marker EGFP-C2LACT was higher in mips1 mips3 than in wild type, suggesting an increased cytoplasmic PS level at the cell plate upon PIPs deficiency (Fig. 4f, h). The total PS levels were comparable between the wild type and mips1 mips3 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Therefore, the elevated PS levels observed in the cytoplasmic layer of the cell plate in mips1 mips3 suggest increased PS flipping activity. Compared to mips1 mips3, VLR_95 and wild type exhibited reduced PS levels at the cell plate, averaging 83% and 82%, respectively, indicating comparable PS levels in both genotypes (Fig. 4e, h).

Following the observation of the discontinuous PS distribution at the cell plate, we investigated the distribution of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 at the 2 μm forepart region of the lagging zone where the cell plate expansion is taking shape, at the discontinuous phragmoplast stage6,19,51. Genetically encoded biosensors mNeonGreen-P4M for PI4P, and CITRINE-2xPHPLC and CITRINE-1xTUBBY-C for PI(4,5)P2 were introduced into Arabidopsis plants52,53,54. Compared to the lipophilic dye FM 4-64, which is known as being rather homogenously localized at the membrane, the PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 markers showed more heterogeneous distributions (Supplementary Fig. 8a–f). The fluorescent signal of mNeonGreen-P4M and mChe-2xPHPLC displayed distinct patterns along the region of interest at the cell plate (Supplementary Fig. 8g–m), suggesting the distinction of spatial distribution between PI4P and PI(4,5)P2.

To better monitor the effect of PI4P depletion during cell plate development, short-term PAO treatment was performed on the transgenic line coexpressing the PI4P marker CITRINE-2xPHFAPP1 52 and the PS marker mChe-C2LACT. Neither PI4P nor PS abundance was affected at the PM after 15 min treatment, but the PI4P level was significantly reduced while the PS level was significantly increased at the cell plate (Fig. 4i, k–n and Supplementary Fig. 9a), suggesting that the cell plate PI4P pool is more sensitive to PAO treatment than the PM pool. Notably, short-term PAO treatment resulted in altered membrane morphology manifesting as cell plate bulges (lower panels of Fig. 4i). At the cell plate, the co-occurrence of PI4P reduction and PS increase after PAO treatment is consistent with PS increase in mips1 mips3, providing additional evidence for the regulation of PS level by PI4P at the cytoplasmic leaflet of developing cell plate.

Notably, long-term PAO treatment abolished membrane-bound PI4P and induced cytokinesis defects, including cell wall stubs and branched cell plates reminiscent of those observed in mips1 mips3 (left panel of Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 9b, c), highlighting the essential role of PI4P in regulating cell plate morphology and ensuring proper cytokinesis. Moreover, the presence of ectopic cell wall stubs under PAO treatment suggests misoriented cell plate formation (left panel of Fig. 4j). Importantly, the increased curvature of the cytoplasmic leaflet along the division plane observed in the cell plate of mips1 mips3 mutants and PAO-treated wild type cells was also evident in the PM, with both mips1 mips3 mutants and long-term PAO-treated wild type cells displaying pronounced PM invaginations and large endocytic vesicles (right panel of Fig. 4j and Supplementary Fig. 9c, d), emphasizing the marked enhancement of lipid flipping across the bilayers triggered by PI4P depletion.

Our results collectively underscore the contribution of anionic lipids to the modulation of membrane shape at both the cell plate and PM. Taken together, these results connect PI4P enrichment at the lagging zone of the cell plate to reduced PS levels, altered PS distribution, decreased membrane curvature, and the proper morphology essential for cytokinesis.

The potential role of PI(4,5)P2-mediated DRP1A constriction region formation in cell plate tabulation

By constructing the cell plate marker with DRP1A, we accidentally discovered that overexpressing DRP1A significantly increased root length (Fig. 5a) and partially rescued cell plate development of mips1 mips3 (Supplementary Movie 5). TEM analysis of the cell plate phenotype demonstrated that overexpression of DRP1A led to a significant reduction in cell plate thickness in mips1 mips3 mutants (Fig. 5b, c), confirming the recovery of the phenotype observed at the cellular level. DRP1A belongs to the dynamin superfamily that plays a key role in the regulation of membrane fission and tubulation, processes essential for many cellular functions such as intracellular trafficking, organelle division, and cytokinesis55. During plant cytokinesis, dynamins are reported to facilitate tubulovesicular network formation and potentially clathrin-coated vesicle budding55. At the PM, DRP1A localizes within small puncta and participates in clathrin-mediated endocytosis during vesicular scission56. To investigate the distribution pattern of DRP1A at the cell plate, we introduced DRP1A-GFP into both the wild type and mips1 mips3 and employed super-resolution confocal microscopy. Our analysis demonstrated that DRP1A-GFP is heterogeneously distributed along the developing cell plate, mainly concentrated in nanodomains but also dispersed in between, revealing coexisting pools of constriction region-associated and dissociated DRP1A (upper panel of Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 10a). On the contrary, the DRP1A-GFP-enriched regions were reduced in number and appeared less compacted in mips1 mips3 (lower panel of Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 10b), suggesting that constriction region formation is impaired upon PIPs deficiency.

a Root lengths were measured in wild type (n = 10), mips1 mips3 (n = 10), and mips1 mips3/DRP1A-GFP (n = 10). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. ***P < 0.0001. b Representative TEM images of developing cell plates at the discontinuous phragmoplast stage in DRP1A-GFP/mips1 mips3 (upper panel) and mips1 mips3 (lower panel). Scale bars: 200 nm (upper); 1 μm (lower). c Cell plate thickness in DRP1A-GFP/mips1 mips3 (n = 31) compared to mips1 mips3 (n = 36), based on measurements from five root cells per genotype at >6 positions per cell plate. two-tailed Student’s t test, **P = 0.0016. d Super-resolution confocal images from at least 10 biological replicates show DRP1A-GFP distribution at the cell plate in wild type and mips1 mips3. Arrowheads indicate DRP1A clustering sites. Scale bars: 1 μm. e Binding affinity of DRP1A for PS and PIPs analyzed using BLI. The data presented are representative of two independent experiments. f Kinetics of PI(4,5)P2-specific binding by DRP1A. Global fitting of the binding kinetics (red lines) provided dissociation constant (KD) values. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments. g Analysis of the cell plate DRP1A nanodomains upon inducible depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by iDePP system. Super-resolution images show DRP1A-GFP (left) and MAP-mChe-dOCRL (middle) signals after DMSO (top) or 150 min DEX treatment (bottom). For each treatment, more than 15 roots were analyzed. White arrowheads indicate DRP1A nanodomains. Scale bar: 5 μm. h Fluorescence intensity profiles of DRP1A-GFP along the cell plate lagging zone with DMSO treatment control or DEX induction as indicated in (g). i DRP1A-GFP heterogeneity was quantified by calculating the coefficient of variation of fluorescence intensities in discontinuous phragmoplast-stage cell plates of 5 DAG root epidermal cells (DMSO, n = 20; DEX, n = 19); ***P = 0.0001, two-tailed t test. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Data in a, c, i are shown as box and whisker plots. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

These findings imply a role for DRP1A in PIPs-mediated regulation of cell division. To explore this further, we investigated the lipid binding profile of DRP1A. Unlike canonical dynamin proteins, which possess a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain for PI(4,5)P2 binding and curvature sensing/generation, DRP1A belongs to the DRP1 subfamily, which is plant-specific and lacks the PH domain57,58. Previous liposome flotation assays demonstrated that DRP1A binds to PI3P, PI4P, PI5P and PS liposomes in vitro, though its interaction with PI(4,5)P2 liposomes was not tested59. Recombinant DRP1A was expressed at the expected molecular weight (Supplementary Fig. 11a) and subsequently used in lipid overlay assay, which demonstrated that DRP1A specifically binds to all phosphorylated phosphatidylinositols (Supplementary Fig. 11b), suggesting direct regulation by PIPs. To further characterize the interaction, we employed BLI, a more sensitive and quantitative method. DRP1A exhibited the strongest binding to PI5P and PI(4,5)P2 liposomes, followed by weaker binding to PI4P and PS liposomes, with negligible interaction with PI3P liposomes (Fig. 5e). Kinetic analysis of the binding between DRP1A and PI(4,5)P2 containing liposomes revealed a KD value of 1.225 μM (Fig. 5f). Notably, minor His-reactive bands, likely from contaminants or degradation, were detected, and their contribution to the lipid-binding signals in the overlay and BLI assays cannot be fully excluded (Supplementary Fig. 11a).

To further confirm the relationship between DRP1A and PI(4,5)P2, we employed the inducible iDePP (inducible depletion of PI(4,5)P2 in plants) system to transiently diminish PI(4,5)P2, to avoid any indirect effect caused by permanent reduction of PI(4,5)P2 in mips1 mips360. PI(4,5)P2 depletion induced by dexamethasone (DEX) treatment significantly reduced DRP1A nanodomains at the cell plate (Fig. 5g), as evidenced by changes in the DRP1A fluorescent profile and the coefficient of variation of fluorescent signals (Fig. 5h, i). These findings further support the role of PI(4,5)P2 in the formation and maintenance of DRP1A constriction regions at the cell plate.

Altogether, our data indicate that PI(4,5)P2 participates in the cell plate DRP1A recruitment and constriction region formation, possibly through direct binding.

Discussion

The plant cell plate undergoes dramatic morphology changes during expansion and maturation, but little is known about how this transformation is achieved. During cytokinesis, several anionic lipids such as PI4P, PI(4,5)P2, PS, and PA accumulate at the cytoplasmic leaflet of the cell plate, while the roles of these lipids at the cell plate during cytokinesis remain largely unsolved. Our findings revealed that PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 levels are essential for cell plate morphology changes, especially tubulation and flattening at the lagging zone where cell plate takes shape. Our data innovatively demonstrate that the level and function of PI4P and PS are linked at the cell plate, revealing how the interplay between different anionic lipid species and the transbilayer lipid coupling is achieved.

Transbilayer lipid asymmetry is associated with membrane physicochemical properties and functions: e.g., the exposure of PS at the cell surface activates the recognition and clearance of apoptotic cells in animals61. Although an asymmetrical distribution of PS between PM leaflets of plant cells has been reported62, the physiological significance of PS transbilayer asymmetry in plants is unclear. Disruption of flip-flop balance, such as ALA1 flippase hyperactivation by suppressor reduction, could cause a lateral pressure difference between each monolayer and subsequently induce membrane bending63,64. Moreover, local transbilayer asymmetry causes local membrane curvature change, which could affect the overall shape of membranous structures with constant volume and surface area65. Flipping of PS or PC by the type IV P-type ATPase could increase cytoplasmic leaflet curvature and promote membrane deformation64,66. On the contrary, for cell plate maturation, the reduction of local or spontaneous membrane curvature is required along with the onset of a spreading force, to facilitate overall cell plate flattening67. Although PS has been reported essential for cell plate development68, our data suggest that excess cytoplasmic PS contributes to the formation of a thicker cell plate or the development of cell plate bulges, suggesting an increased cytoplasmic curvature along the division plane. To explicitly validate this interpretation, future work incorporating precise local curvature quantification coupled with a mathematical model will be essential. As membrane lipids constantly undergo transbilayer movement to establish and maintain transbilayer asymmetry69,70, the activity of lipid translocators such as flippase is strictly regulated. Our data suggest that genetic or biochemical depletion of PI4P causes a substantial increase in the cytoplasmic leaflet curvature of both the cell plate and the PM through ALA1. However, two issues remain unresolved: (1) whether other flippases are involved in the PI4P-dependent regulation of cell plate curvature, and (2) whether ALA1 facilitates the translocation of lipids beyond PS, to modulate curvature. Moreover, further investigations are required to unravel the detailed molecular mechanisms by which PI4P modulates ALA1 activity. Elucidating these processes will not only advance our understanding of lipid-mediated modulation of membrane protein function but also shed light on broader aspects of lipid signaling and membrane remodeling.

In addition to PIPs, membrane lipids such as sterol and very-long-chain fatty acids also participate in cell plate development and cause ectopic accumulation of cell plate markers such as KNOLLE, which mediates vesicle fusion during cytokinesis71,72,73. Similar incomplete cytokinesis and cell wall stubs have been reported in the DRP1A mutant rsw9 and the syntaxin KNOLLE mutant kn; as well as under diverse chemical treatments that inhibit the ER-Golgi or TGN trafficking9,31,74,75,76,77. These lines of evidence indicate that complete cell division requires exquisite control of different stages. DRP1A was proposed to target the cell plate through direct interaction with SH3P2, which contains a BAR domain for PIPs binding11. Moreover, DRP1A is found together with sterols, contributing to the maintenance of high lipid order at the cell plate during cytokinesis78. Our data showed that DRP1A could bind directly to PI5P, PI(4,5)P2, PI4P, and PS-containing liposomes, suggesting an unconventional lipid binding strategy of DRP1A. Purified DRP1A could form large polymers in vitro and promote liposome clustering; however, it failed to tubulate liposomes and form rings observed encircling the cell plate membrane tubules during the syncytial endosperm cellularization, indicating that additional in vivo factors are required for DRP1A to maintain full functionality10,59. In addition, maturation of the cell plate requires the removal of excess membrane by clathrin-coated vesicles, as well as the constriction of fused vesicular compartments and wide tubular network at different stages, both of which need the dynamin protein for fission or tubulation, respectively10. DRP1A at the PM functions as a pinchase during clathrin-mediated endocytosis79,80. In animal cells, sequential phosphoinositide conversion at the PM confers vesicle identity at intermediate steps during clathrin-mediated endocytosis54. Given the distinct temporal and spatial distribution patterns of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 at the cell plate, it is likely that DRP1A fulfills both fission and tubulation roles, modulated by the dynamic lipid environment and protein cofactors at various stages of cell plate development.

Super-resolution microscopy revealed a discontinuous distribution pattern of PS and a clustered localization of DRP1A in the lagging zone of the developing cell plate. In addition, a heterogeneous distribution of PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 was observed at the leading edge of the lagging zone during the discontinuous phragmoplast stage. Determining whether the observed distribution patterns of PIPs, PS, and DRP1A are functionally interconnected requires further investigation, which would be facilitated by advances in tools and techniques. Beyond direct protein interactions, PIPs may affect the membrane’s physical properties—such as curvature, charge, fluidity, and lipid nanodomain organization—potentially influencing the localization and activity of ALA1 and DRP1A. Additionally, other regulatory proteins, such as SH3P2, might also contribute to PIPs-mediated curvature modulation. As shown previously, PS flipped by ALA1, as well as cell plate curvature along the division plane manifested by bulges and thickening, are significantly increased in mips1 mips3 or upon PAO treatment. Combining this with the fact that the DRP1A distribution pattern along the cell plate is altered in mips1 mips3 or by transient PI(4,5)P2 depletion, we propose that PI4P-inhibited PS flipping and PI(4,5)P2-mediated DRP1A constriction region formation coordinately regulate morphology change during cell plate development (Fig. 6). Recent biophysical modeling suggests that late-stage cytokinesis requires both the initiation of a spreading force and a reduction in membrane curvature to enable the transition to a flattened cell plate67. In mips1 mips3, enhanced PS flipping increases curvature stress, promoting spherification rather than lateral expansion of the cell plate. At the same time, impaired recruitment of dynamin-related proteins may diminish the mechanical forces needed for membrane spreading. These disruptions give rise to abnormal morphologies, such as thickened or segmented cell plates that are structurally unstable and fail to complete cytokinesis, resulting in persistent cell wall stubs. Additionally, changes in lipid composition may interfere with membrane fusion and recycling, further contributing to cytokinesis defects in the mutant. Our findings highlight that regulating levels and transbilayer asymmetry of anionic lipids are important in shaping the cell plate during its maturation. These results illuminate the broader roles of anionic lipids in regulating membrane dynamics and compartmentalization, offering a framework for investigating their functional contributions to the organization and remodeling of intracellular membranes across diverse cellular processes and contexts.

PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 at the lagging zone of the developing cell plate are critical for successful cytokinesis. PI4P reduces local membrane curvature along the division plane by inhibiting PS flipping via ALA1, while PI(4,5)P2 facilitates DRP1A recruitment to promote constriction region formation. In mips1 mips3, the reduction of these lipids increases membrane curvature, disrupts tubulation and prevents cell plate flattening, leading to thickened and incomplete cell plates. This model highlights PI4P-regulated transbilayer lipid asymmetry, combined with PI(4,5)P2-induced external forces generated by dynamin polymerization, to ensure proper cell plate morphology and successful plant cell division.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

All Arabidopsis materials used in this research were in the Columbia background (Col-0). Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized and stratified for 2 days at 4 °C before being sown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS medium: 10 g/L sucrose (S0389; Sigma-Aldrich), 2.2 g/L MS basal salt mixture (M0221.0005; Duchefa Biochemie), 0.5 g/L MES salt (145224-94-8; AMRESCO Chemicals), 9 g/L Phytagel (P8169; Sigma-Aldrich), pH 5.8) without or with inositol (I7508; Sigma-Aldrich) as required. Seedlings were grown vertically at 22 °C in a 16-h/8-h light-dark cycle. The lines mips1 mips321, mips1 mips3/MIPS121, CITRINE-2xPHFAPP152, CITRINE-2xPHPLC52, CITRINE-2xFYVEHRS52, CITRINE-1xTUBBY-C52, HTR12-GFP28, GFP-TUB630 used in this study have been described previously. mNeonGreen-P4M53,54/mChe-2xPHPLC52 was constructed by crossing these two marker lines. SALK_002106 and SALK_056947 seeds were acquired from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC, UK). Mips1 mips3/HTR12-GFP, mips1 mips3/DRP1A-GFP, mips1 mips3/GFP-TUB6, mips1 mips3/CITRINE-2xPHFAPP1, mips1 mips3/CITRINE-2xPHPLC, mips1 mips3/ CITRINE-2xFYVEHRS, mips1 mips3/EGFP-C2LACT were generated by crossing mips1 mips3 with marker line HTR12-GFP, DRP1A-GFP, GFP-TUB6, CITRINE-2xPHFAPP1, CITRINE-2xPHPLC, CITRINE-2xFYVEHRS, EGFP-C2LACT50, respectively. VLR_95/ALA1 was developed by introducing pGWB508-ALA1 into VLR_95 seedlings through transformation. The VLR_95 line was genotyped by PCR amplification followed by sequencing to confirm the presence of the point mutation. DRP1A-GFP/MAP-mChe-dOCRL was constructed by transforming DRP1A-GFP plants with the inducible MAP-mChe-dOCRL vector60.

Generation of constructs

All vectors were constructed using the Gateway cloning technology (11789020 and 11791020; Thermo Fisher Scientific), except the E. coli expression vectors, which are constructed by Gibson assembling. The coding sequences of DRP1A and ALA1 were amplified via PCR (KOD-401; TOYOBO) from first-strand cDNA (18091050; Invitrogen). The coding sequence of the C2LACT domain, mNeonGreen, and P4M(DrrA) domain were amplified from the published vectors50,53,54,81. The fluorescent proteins and lipid binding domains were linked by GGS 5x linker (5′-GGAGGATCCGGTGGATCTGGAGGTTCTGGTGGTTCTGGTGGTTCC-3′), and introduced into pDONR221. Vectors pDONR P4-P1R-UBQ1082 and pDONR 221-EGFP-C2LACT were introduced into pH7m24GW,383 to create the transcriptional reporter vector. Vectors pDONR P4-P1R-UBQ1082 and pDONR 221-mNeonGreen-P4M(DrrA) were introduced into pK7m24GW,383 to create the transcriptional reporter vector. DRP1A-GFP was constructed by introducing pDONR 221-DRP1A into pK7FWG283. pGWB508-ALA1 was constructed by introducing pDONR 221-ALA1 into pGWB50884. For ALA1-GFP, pDONR 221-ALA1 without a stop codon was introduced into the destination vector pH7FWG283.

Lipidomics analysis

Ffive DAG Arabidopsis seedlings were harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until lipid extraction. For each replicate, 100 mg of fresh tissue was used. Lipid extraction followed a modified Bligh and Dyer method. Seedling tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of cold extraction solvent (chloroform:methanol:water, 2:1:0.8, v/v/v) with internal standards (330825, 330830; Avanti). The homogenates were incubated on ice for 30 min, vortexed intermittently, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The organic phase was collected, dried under nitrogen, and resuspended in 200 μL chloroform for analysis. Lipids were quantified using a triple quadrupole LC-MS/MS system (AB Sciex QTRAP 6500) with electrospray ionization (ESI). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a reverse-phase C18 column using a binary gradient of solvent A (acetonitrile:water, 6:4, v/v, 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (isopropanol:acetonitrile, 7:3, v/v, with 0.1% formic acid and 5 mM ammonium formate). The gradient was as follows: 40% B for 2 min, increasing to 100% B over 8 min, and held at 100% B for 2 min. Lipids were detected using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). Relative quantification was achieved by normalizing lipid signals to internal standards. For absolute quantification, lipid extracts were spiked with the PI Internal Standard Mixture (330830; Avanti), and PIP standards were used to generate a calibration curve. Experiments were conducted with four biological replicates for relative quantification and three for absolute quantification.

Imaging and signal quantification

All seedlings used for confocal imaging were grown on 1/2 MS medium without inositol unless indicated. FM 4-64 staining was done by immersing seedlings in 5 μM FM 4-64 solution for 5 min and subsequently rinsed out with ddH2O six times before imaging. For colocalization analysis, the fluorescence intensity was determined in single transgenic lines stained with FM 4-64 or double transgenic lines. Since PI(4,5)P2 signal first appears at the late stage of cell plate development, with cell plate partially attached to the PM and the discontinuous phragmoplast formed, we chose cell plates of this stage for colocalization assay to make consistency in analysis. The cell plate regions that were measured are ~2 μm in length and locate ~1 μm from the expanding edge, representing the lagging zone where the cell plate takes shape6,19,51. Profiles for quantitative signal intensity distribution and colocalization were generated using ZEN lite 3.5 software (Zeiss). The model goodness of fit was calculated by a linear regression model analysis of signal intensities along the selected cell plate region using GraphPad Prism 9. For the comparisons of cell plate DRP1A-GFP or EGFP-C2LACT signal distribution patterns between wild type and mips1 mips3, root epidermal cells of 5 DAG seedlings were analyzed, and the discontinuous phragmoplast stage cell plates which were partially attached to the parental PM are demonstrated. The ROIs selected for Fig. 4f and Fig. 5d represent around 5 μm long cell plate regions involving the leading zone and the lagging zone6,51. Fluorescence images were captured using an LSM 980 inverted confocal microscope (Zeiss) equipped with Airyscan 2 detector, under a 63x/1.4 NA Oil Dic M27 objective lens. Micrographs were analyzed using the ZEN lite 3.5 software (Zeiss). The relative membrane fluorescence was calculated as described previously85. Briefly, the fluorescence intensities of both the cell plate or PM and the intracellular space were measured with fixed ROIs by ImageJ. The relative cell plate or PM fluorescence was achieved by dividing the cell plate or PM fluorescence intensity by the intracellular fluorescence intensity. GFP, mNeonGreen, and CITRINE were excited with a 488 nm laser line and detected between 491 nm and 535 nm. mChe and FM 4-64 were excited at 587 nm and 506 nm laser lines, and detected at 610–658 nm, and 621–757 nm, respectively. NBD-PS was excited using a 488 nm laser line, and its fluorescence was detected within the range of 454 nm to 693 nm. For super-resolution imaging, LSM 980 was set to Airyscan 2 SR mode with Joint Deconvolution, and scan speed was set at 5 with 2x signal averaging, to improve resolution and signal-to-noise ratio.

Transmission electron microscopy

5 DAG Arabidopsis root tips were collected from seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium lacking inositol, and fixed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 4% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde (G7651; Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature (RT) for 2 h, and then 4 °C overnight. Samples were washed three times with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at RT before post-fixation with 1% OsO4 for 2 h at RT. Samples were washed four times with an interval of 30 min for each time with ddH2O, and then stained with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 h. After wash and acetone dehydration, root tips were infiltrated using a series of resin-acetone mixes, followed by resin embedding (14120; Electron Microscopy Sciences) as described by the manufacturer. Samples were sectioned into 100 nm slices and stained by 0.2% lead citrate solution for transmission electron microscope examination (JEM-1400; JEOL Ltd.).

EMS mutagenesis and BSA analysis

10,000 mips1 mips3 seeds were treated with 0.2% ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) in 100 mM phosphate buffer for 15 h at RT. Seeds were washed 20 times and sown in soil for M1 seeds. M2 seeds were obtained by self-crossed M1 seedlings, and planted on 1/2 MS (w/o inositol) plates and directly screened for mutants with recovered root length. Identified M2 candidates were backcrossed with mips1 mips3, and confirmed F1 plants were self-fertilized to produce F2 segregating populations. Leaves from at least 20 seedlings were pooled and used for genomic DNA extraction (69204; QIAGEN). DNA samples from parental lines (M2 candidate and mips1 mips3) and two bulk populations (F2 seedlings with either long roots or short roots) were used to construct sequencing libraries (RS-122-2001; Illumina, Inc.) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqTM PE150 platform. SNP-index analysis was calculated for all SNPs as described in ref. 86. The SNP positions with Δ(SNP-index) value = 1 were selected and set for further analysis to identify the causative mutation.

Protein expression and purification

Coding sequences of DRP1A, the two cytoplasmic loops, and the C-terminal fragment of ALA1 were cloned into E. coli. expression vector pET-28a(+), with both N-terminal and C-terminal 6xHis-tag. Transformant cells were collected after IPTG induction at 17 °C for 16 h. Proteins were extracted by high-pressure homogenization under 40 MPa, 4 °C, with extraction buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (P8849; Sigma-Aldrich). Proteins were then purified by magnetic agarose beads (H9914-1ML; Sigma-Aldrich). Beads were washed three times using extraction buffer at 4 °C and incubated with protein supernatants at 4 °C overnight. After that, beads were washed three times at 4 °C with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM imidazole). Proteins were eluted from the washed beads using elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.5% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (P8849; Sigma-Aldrich), 200 mM imidazole) at 4 °C for 30 min. Finally, the elution buffer was displaced by storage buffer using Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter (UFC801024; Merck) for protein storage and further analysis.

Western blot analysis

Protein samples were added 25% loading buffer and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. For western blot analysis of DRP1A, ALA1 (amino acids 151-329), and ALA1 (amino acids 410-914), protein separation was conducted using a 10% precast polyacrylamide gel (P0455M; Beyotime) and prestained protein marker ranging from 10 to 200 kDa (G2058; Servicebio). For the ALA1 C-terminal fragment, protein samples were separated using a 15% precast polyacrylamide gel (P0461M; Beyotime) along with prestained protein marker ranging from 2 to 40 kDa (G2090; Servicebio). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 1X TBS containing 5% milk. Immunoblotting was performed using a primary antibody against His-tag (1:1000; His Tag Rabbit Monoclonal Antibody, AG8061; Beyotime) and a peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:10000; 5220–0336; Seracare). Chemiluminescent signals were detected using Western ECL Substrate (1705060; Bio-Rad). Images obtained from the chemiluminescent Western blot and the protein markers were merged to facilitate accurate molecular weight determination.

Lipid overlay assay

The hydrophobic PIP array strips (P-6001; Echelon Biosciences, Inc.) were blocked in BSA-T + 3% BSA (SRE0098; Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C, and then incubated with the purified peptides (0.5 μg/mL each) for 1 h at RT with gentle agitation. The membranes were washed in TBS-T (three times and 10 min each time) and then incubated with anti-His-HRP antibody (1:1000; MA1-21315-HRP; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with gentle agitation for 1 h at RT. The strips were washed in TBS-T as described above, and then detected by chemiluminescence using ECL detection reagent (34580; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

BLI analysis

Phospholipid stock solutions (20 mM in chloroform) were stored in glass bottles under an inert atmosphere at −20 °C. Liposomes containing 3% PIPs (18:1 PI(4)P, 850151 P; 18:1 PI(4,5)P2, 850155 P; 18:1 PI (3) P, 850150 P; 18:1 PI(5)P, 850152 P; Avanti) and PS (18:1 PS (DOPS), 840035 P; Avanti) were prepared by mixing the required lipids with 97% 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) (42773; Sigma-Aldrich) in glass vials (WAT270946DV; Waters). As a control, 100% POPC liposomes were prepared. The lipid mixtures were dried under a stream of nitrogen to form a thin film, then further dried under vacuum for at least 4 h to remove residual solvent. The dried lipid films were hydrated with HEPES buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 5% glucose, and 10% sucrose, pH 7.5) to achieve a final lipid concentration of 1 mM. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared by sonication (53 kHz, 40% power, 18 °C) for 15–20 min until optically clear. The SUVs were stored at 4 °C and used within 48 h.

Binding interactions between the protein and liposomes were assessed using the Octet RED96 system (Octet R8; Sartorius) with Ni-NTA biosensors (18-5101; Sartorius). Sensors were hydrated in liposome preparation buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20 (9005-64-5; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min, then loaded with 2 μM protein in HEPES buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 1% BSA (SRE0098; Sigma-Aldrich). Protein immobilization occurred via coordination of the His tag to the nickel ion. After equilibration, sensors were dipped into liposome solutions (association phase) and buffer (dissociation phase), and binding signals were recorded in real time. Baseline corrections were performed by subtracting the POPC control signal. Binding curves were analyzed using Octet Data Analysis software, and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) were derived by fitting data to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model.

For specific phospholipid binding, aminopropylsilane (APS) biosensors (18-5045; Sartorius) were hydrated in liposome preparation buffer and loaded with 0.5 mM liposomes until saturation. Excess liposomes were removed by washing with HEPES buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 1% BSA. The liposome-loaded sensors were then exposed to serial dilutions of target protein (100–400 nM) in HEPES buffer. Real-time association and dissociation signals were recorded and corrected for baseline drift. KD values were determined using nonlinear regression with Octet Data Analysis software. All experiments were performed twice with similar results.

Chemical treatments

Chemical stocks were prepared in DMSO at the following concentrations: 40 mM PAO (P3075, Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM DEX (D1756; Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 mM NBD-PS (810192 P; Avanti). For PAO treatment, 5 DAG Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated in 1/2 MS liquid medium with 0.1% DMSO (control), or 40 μM PAO, for the indicated time periods. For DEX induction, 5 DAG Arabidopsis seedlings were incubated in 1/2 MS liquid medium with 0.1% DMSO (control), or 5 μM DEX for 150 min.

NBD-PS uptake assay

Five DAG Arabidopsis seedlings from each genotype were incubated in 20 µM NBD-PS (810192 P; Avanti) in liquid 1/2MS medium for 1 h at room temperature in the dark to label PS uptake. The seedlings were then washed with fresh 1/2 MS medium 5 times to remove unbound NBD-PS. To evaluate the effect of PAO on PS flipping in the wild type background, wild type seedlings were pre-treated with 40 µM PAO for 1 h before performing the NBD-PS uptake assay as described above. After NBD-PS incubation, the root epidermal cells were excised and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope to detect NBD-PS fluorescence. All imaging acquisition settings were maintained consistently across samples with different genotypes or treatments. The average fluorescence intensity of NBD-PS was quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.53) with a fixed ROI to evaluate the relative uptake.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc.), unless otherwise noted. Comparisons between two independent groups were analyzed using two-tailed unpaired t-tests, following assessment of variance homogeneity by the F-test. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was employed for comparisons among multiple groups. For multiple hypothesis testing, P values were adjusted using the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. The coefficient of variation provides a measure of the relative variability in the fluorescent protein distribution and was calculated as the standard deviation divided by the mean to quantify signal heterogeneity: Coefficient of variation (%) = (standard deviation of the fluorescence intensities/mean of the fluorescence intensities) × 100. Linear regression models were applied in GraphPad Prism 9, and nonlinear regression fitting for BLI kinetic data was conducted using Octet Data Analysis software (Sartorius).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study are available in this article and its supplementary information, or upon request from the corresponding authors. All Arabidopsis genes involved in this study can be found at TAIR (www.arabidopsis.org), with the following accession numbers: MIPS1 (AT4G39800), MIPS3 (AT5G10170), ALA1 (AT5G04930), and DRP1A (AT5G42080). Protein sequences are accessible at UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) with the following accession numbers: ALA1 (P98204) and DRS2P (P39524). The raw mass spectrometry data have been deposited into the MassIVE database (https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/static/massive.jsp) with the dataset identifier MSV000098180 [https://massive.ucsd.edu/ProteoSAFe/dataset.jsp?task=236636c099004628a0de9f0396894667]. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Lee, Y. R. & Liu, B. The rise and fall of the phragmoplast microtubule array. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 757–763 (2013).

Lukowitz, W., Mayer, U. & Jürgens, G. Cytokinesis in the Arabidopsis embryo involves the syntaxin-related KNOLLE gene product. Cell 84, 61–71 (1996).

Zhang, L. et al. Arabidopsis R-SNARE proteins VAMP721 and VAMP722 are required for cell plate formation. PLoS ONE 6, e26129 (2011).

Park, M. et al. Sec1/Munc18 protein stabilizes fusion-competent syntaxin for membrane fusion in Arabidopsis cytokinesis. Dev. Cell 22, 989–1000 (2012).

Seguí-Simarro, J. M. et al. Electron tomographic analysis of somatic cell plate formation in meristematic cells of Arabidopsis preserved by high-pressure freezing. Plant Cell 16, 836–856 (2004).

Smertenko, A. et al. Plant cytokinesis: terminology for structures and processes. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 885–894 (2017).

Thiele, K. et al. The timely deposition of callose is essential for cytokinesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 58, 13–26 (2009).

Kang, B. H., Busse, J. S. & Bednarek, S. Y. Members of the Arabidopsis dynamin-like gene family, ADL1, are essential for plant cytokinesis and polarized cell growth. Plant Cell 15, 899–913 (2003).

Collings, D. A. et al. Arabidopsis dynamin-like protein DRP1A: a null mutant with widespread defects in endocytosis, cellulose synthesis, cytokinesis, and cell expansion. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 361–376 (2008).

Otegui, M. S. et al. Three-dimensional analysis of syncytial-type cell plates during endosperm cellularization visualized by high resolution electron tomography. Plant Cell 13, 2033–2051 (2001).

Ahn, G. et al. SH3 domain-containing protein 2 plays a crucial role at the step of membrane tubulation during cell plate formation. Plant Cell 29, 1388–1405 (2017).

Caillaud, M. C. Anionic lipids: a pipeline connecting key players of plant cell division. Front Plant Sci. 10, 419 (2019).

Noack, L. C. & Jaillais, Y. Functions of anionic lipids in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 71, 71–102 (2020).

Kobayashi, T. & Menon, A. K. Transbilayer lipid asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 28, R386–R391 (2018).

Mamode Cassim, A. et al. Plant lipids: key players of plasma membrane organization and function. Prog. Lipid Res. 73, 1–27 (2019).

Abe, M. et al. A role for sphingomyelin-rich lipid domains in the accumulation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 32, 1396–1407 (2012).

Balla, T. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol. Rev. 93, 1019–1137 (2013).

Lin, F. et al. A dual role for cell plate-associated PI4Kβ in endocytosis and phragmoplast dynamics during plant somatic cytokinesis. EMBO J. 38, e100303 (2019).

Lebecq, A. et al. The phosphoinositide signature guides the final step of plant cytokinesis. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf7532 (2023).

Idevall-Hagren, O. & De Camilli, P. Detection and manipulation of phosphoinositides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851, 736–745 (2015).

Luo, Y. et al. D-myo-inositol-3-phosphate affects phosphatidylinositol-mediated endomembrane function in Arabidopsis and is essential for auxin-regulated embryogenesis. Plant Cell 23, 1352–1372 (2011).

Stevenson-Paulik, J. et al. Generation of phytate-free seeds in Arabidopsis through disruption of inositol polyphosphate kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA102, 12612–12617 (2005).

Gillaspy, G. E. The cellular language of myo-inositol signaling. N. Phytol. 192, 823–839 (2011).

Meng, P. H. et al. Crosstalks between myo-inositol metabolism, programmed cell death and basal immunity in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 4, e7364 (2009).

Chen, H. & Xiong, L. Myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase is required for polar auxin transport and organ development. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24238–24247 (2010).

Murphy, A. M. et al. A role for inositol hexakisphosphate in the maintenance of basal resistance to plant pathogens. Plant J. 56, 638–652 (2008).

Zhai, H. et al. A myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase gene, IbMIPS1, enhances salt and drought tolerance and stem nematode resistance in transgenic sweet potato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 592–602 (2016).

Fang, Y. & Spector, D. L. Centromere positioning and dynamics in living Arabidopsis plants. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 5710–5718 (2005).

Söllner, R. et al. Cytokinesis-defective mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 678–690 (2002).

Tian, J. et al. Orchestration of microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton in trichome cell shape determination by a plant-unique kinesin. Elife 4, e09351 (2015).

Lauber, M. H. et al. The Arabidopsis KNOLLE protein is a cytokinesis-specific syntaxin. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1485–1493 (1997).

Tang, X. et al. subfamily of P-type ATPases with aminophospholipid transporting activity. Science 272, 1495–1497 (1996).

López-Marqués, R. L. et al. Intracellular targeting signals and lipid specificity determinants of the ALA/ALIS P4-ATPase complex reside in the catalytic ALA alpha-subunit. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21, 791–801 (2010).

Gomès, E. et al. Chilling tolerance in Arabidopsis involves ALA1, a member of a new family of putative aminophospholipid translocases. Plant Cell 12, 2441–2454 (2000).

Omasits, U. et al. Protter: interactive protein feature visualization and integration with experimental proteomic data. Bioinformatics 30, 884–886 (2014).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

López-Marqués, R. L., Poulsen, L. R. & Palmgren, M. G. A putative plant aminophospholipid flippase, the Arabidopsis P4 ATPase ALA1, localizes to the plasma membrane following association with a β-subunit. PLoS ONE 7, e33042 (2012).

López-Marqués, R. L. Mini-review: lipid flippases as putative targets for biotechnological crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1107142 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. TPC proteins are phosphoinositide-activated sodium-selective ion channels in endosomes and lysosomes. Cell 151, 372–383 (2012).

Zhang, X., Li, X. & Xu, H. Phosphoinositide isoforms determine compartment-specific ion channel activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11384–11389 (2012).

Carpaneto, A. et al. The signaling lipid phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate targets plant CLC-a anion/H+ exchange activity. EMBO Rep. 18, 1100–1107 (2017).

Le, S. C. et al. Molecular basis of PIP2-dependent regulation of the Ca2+-activated chloride channel TMEM16A. Nat. Commun. 10, 3769 (2019).

Shin, J. J. H. et al. pH biosensing by PI4P regulates cargo sorting at the TGN. Dev. Cell 52, 461–476.e4 (2020).

Poulsen, L. R. et al. A phospholipid uptake system in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Commun. 6, 7649 (2015).

Jensen, M. S. et al. Phospholipid flipping involves a central cavity in P4 ATPases. Sci. Rep. 7, 17621 (2017).

Azouaoui, H. et al. High phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P)-dependent ATPase activity for the Drs2p-Cdc50p flippase after removal of its N- and C-terminal extensions. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 7954–7970 (2017).

Timcenko, M. et al. Structure and autoregulation of a P4-ATPase lipid flippase. Nature 571, 366–370 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. FATCAT 2.0: towards a better understanding of the structural diversity of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, W60–W64 (2020).

Simon, M. L. et al. A PtdIns(4)P-driven electrostatic field controls cell membrane identity and signaling in plants. Nat. Plants 2, 16089 (2016).

Yeung, T. et al. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science 319, 210–213 (2008).

Smertenko, A. et al. Phragmoplast microtubule dynamics - a game of zones. J. Cell Sci. 131, jcs203331 (2018).

Simon, M. L. et al. A multi-colour/multi-affinity marker set to visualize phosphoinositide dynamics in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 77, 322–337 (2014).

Hammond, G. R., Machner, M. P. & Balla, T. A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J. Cell Biol. 205, 113–126 (2014).

He, K. et al. Dynamics of phosphoinositide conversion in clathrin-mediated endocytic traffic. Nature 552, 410–414 (2017).

Praefcke, G. J. & McMahon, H. T. The dynamin superfamily: universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules?. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 133–147 (2004).

Yoshinari, A. et al. DRP1-dependent endocytosis is essential for polar localization and boron-induced degradation of the borate transporter BOR1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 57, 1985–2000 (2016).

Fujimoto, M. & Tsutsumi, N. Dynamin-related proteins in plant post-Golgi traffic. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 408 (2014).

Hong, Z. et al. A unified nomenclature for Arabidopsis dynamin-related large GTPases based on homology and possible functions. Plant Mol. Biol. 53, 261–265 (2003).

Backues, S. K. & Bednarek, S. Y. Arabidopsis dynamin-related protein 1A polymers bind, but do not tubulate, liposomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393, 734–739 (2010).

Doumane, M. et al. Inducible depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by the synthetic iDePP system in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 7, 587–597 (2021).

Segawa, K. & Nagata, S. An apoptotic ‘eat me’ signal: phosphatidylserine exposure. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 639–650 (2015).

Takeda, Y. & Kasamo, K. Transmembrane topography of plasma membrane constituents in mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) hypocotyl cells. I. Transmembrane distribution of phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1513, 38–48 (2001).

Graham, T. R. & Kozlov, M. M. Interplay of proteins and lipids in generating membrane curvature. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 430–436 (2010).

Takada, N. et al. Phospholipid-flipping activity of P4-ATPase drives membrane curvature. EMBO J. 37, e97705 (2018).

Mironov, A. et al. Membrane curvature, trans-membrane area asymmetry, budding, fission and organelle geometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7594 (2020).

Xu, P. et al. Phosphatidylserine flipping enhances membrane curvature and negative charge required for vesicular transport. J. Cell Biol. 202, 875–886 (2013).

Jawaid, M. Z. et al. A biophysical model for plant cell plate maturation based on the contribution of a spreading force. Plant Physiol. 188, 795–806 (2022).

Yamaoka, Y. et al. Phosphatidylserine is required for the normal progression of cell plate formation in Arabidopsis root meristems. Plant Cell Physiol. 62, 1396–1408 (2021).

Contreras, F. X. et al. Transbilayer (flip-flop) lipid motion and lipid scrambling in membranes. FEBS Lett. 584, 1779–1786 (2010).

Fujimoto, T. & Parmryd, I. Interleaflet coupling, pinning, and leaflet asymmetry-major players in plasma membrane nanodomain formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 4, 155 (2017).

Müller, I. et al. Syntaxin specificity of cytokinesis in Arabidopsis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 531–534 (2003).

Boutté, Y. et al. Endocytosis restricts Arabidopsis KNOLLE syntaxin to the cell division plane during late cytokinesis. EMBO J. 29, 546–558 (2010).

Bach, L. et al. Very-long-chain fatty acids are required for cell plate formation during cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3223–3234 (2011).

Yasuhara, H. Caffeine inhibits callose deposition in the cell plate and the depolymerization of microtubules in the central region of the phragmoplast. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 1083–1092 (2005).

Reichardt, I. et al. Plant cytokinesis requires de novo secretory trafficking but not endocytosis. Curr. Biol. 17, 2047–2053 (2007).

Van Damme, D. et al. Adaptin-like protein TPLATE and clathrin recruitment during plant somatic cytokinesis occurs via two distinct pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 615–620 (2011).

Park, E. et al. Endosidin 7 specifically arrests late cytokinesis and inhibits callose biosynthesis, revealing distinct trafficking events during cell plate maturation. Plant Physiol. 165, 1019–1034 (2014).

Frescatada-Rosa, M. et al. High lipid order of Arabidopsis cell-plate membranes mediated by sterol and DYNAMIN-RELATED PROTEIN1A function. Plant J. 80, 745–757 (2014).

Konopka, C. A. & Bednarek, S. Y. Comparison of the dynamics and functional redundancy of the Arabidopsis dynamin-related isoforms DRP1A and DRP1C during plant development. Plant Physiol. 147, 1590–1602 (2008).

Fujimoto, M. et al. Arabidopsis dynamin-related proteins DRP2B and DRP1A participate together in clathrin-coated vesicle formation during endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 6094–6099 (2010).

Shaner, N. C. et al. A bright monomeric green fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum. Nat. Methods 10, 407–409 (2013).

Marquès-Bueno, M. D. M. et al. A versatile Multisite Gateway-compatible promoter and transgenic line collection for cell type-specific functional genomics in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 85, 320–333 (2016).

Karimi, M., Inzé, D. & Depicker, A. GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 193–195 (2002).