Abstract

Microbubbles are an important tool due to their unique mechanical, acoustic, and dynamical properties. Yet, it remains challenging to generate microbubbles quickly in a parallel, biocompatible, and controlled manner. Here, we present an opto-electrochemical method that combines precise light-based projection with low-energy electrolysis, realizing defined microbubble patterns that in turn trigger assembly processes. The size of the bubbles can be controlled from a few to over hundred micrometers with a spatial accuracy of ~2 μm. The minimum required light intensity is only ~0.1 W/cm2, several orders of magnitude lower compared to other light-enabled methods. We demonstrate the assembly of prescribed patterns of 40-nm nanocrystals, 200 nm extracellular vesicles, polymer nanospheres, and live bacteria. We show how nanosensor-bacterial-cell arrays can be formed for spectroscopic profiling of metabolites and antibiotic response of bacterial assemblies. The combination of a photoconductor with electrochemical techniques enables low-energy, low-temperature bubble generation, advantageous for large-scale, one-shot patterning of diverse particles in a biocompatible manner. The microbubble-platform is highly versatile and promises new opportunities in nanorobotics, nanomanufacturing, high-throughput bioassays, single cell omics, bioseparation, and drug screening and discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbubbles exhibit special mechanical, acoustic, and dynamical properties and have become important tools in fields ranging from medical imaging to microfabrication. Their ability to interact with soft matter has been explored for diverse applications, including microfluidic pumping and mixing1,2,3,4,5, chemical switching6,7, drug delivery8,9, shaping ultrasound fields10, and in the propulsion of micro/nanorobots11,12,13,14. Ultrasonically excited microbubbles can transduce forces directly15, or indirectly via streaming or nonlinear effects, and can be amplified to move objects in solution16. Microbubbles that are not resonantly excited can induce local fluid flows to manipulate colloidal and nano-particulate matter17. This capability is particularly useful in overcoming the technical challenges in complex device design and fabrication for high-throughput bioassays, single-cell omics, and rapid drug screening. Technically, microbubble-enabled particle assembly often involves the generation of a single microbubble with a focused laser beam to deposit particles onto a substrate via convective flows that form around the microbubble. The laser beam can also be raster-scanned to move the micro-bubble and thereby drive complex nanoparticle deposits17. However, this method is relatively slow as it involves a single microbubble and a major drawback is that it operates at elevated temperatures as the microbubbles are thermo-optically generated, which severely restricts its usefulness for any potential biological application.

Conventionally, microbubbles are formed in prefabricated templates, including concave microstructures, which can then be used to mediate acoustic forces14. However, the bubble patterns are defined by the template and are thus static. Alternately, the use of laser-induced heating can form opto-thermal microbubbles at the focus of the laser. While the use of plasmonic Au/Ag nanoparticles or surfaces reduces the required laser power18,19,20, the direct formation of a microbubble with a laser always requires relatively high intensities and temperatures (>60° C up to 250° C, depending on bubble size17). As the opto-thermal approach utilizes a laser focus, it is difficult to adapt this method for larger-scale applications and importantly restricts the capability in working with temperature-sensitive biological samples. Therefore, it is desirable to explore alternative schemes to form bubbles, such as electrolysis. Thus far, there have been no reports on biologically meaningful applications (with the exception of cell lysis) using thermal bubbles21. While electrolysis can proceed at room temperature, it is challenging to define the size, location, or number of bubbles that are generated. Overall, several drawbacks of existing state-of-the-art techniques restrict practical applications of microbubbles (Table S1)22,23.

Here, we show an alternative microbubble scheme that uses low-intensity light to obtain defined microbubble patterns and we show that these can be used to assemble diverse colloidal matter, including extracellular vesicles and biological cells at room temperature, into complex patterns. The term “assembly” here describes primarily the action of collecting and aggregating entities without ordering them, but in some cases, we did observe the formation of more ordered semicrystalline arrangements of particles after bubble deposition.

We show that very low light levels can trigger the formation of microbubbles via the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). We utilize a photoconducting α-Si:H surface deposited on a fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate to convert low-intensity light patterns into versatile bubble patterns. In the absence of light, the α-Si:H prevents any current from flowing and hence prevents the gas formation via electrolysis. However, electrolysis proceeds when the α-Si:H becomes conducting under light, even at low intensities (~0.1 W/cm2). This enables room temperature applications and ensures the high scalability of our technique, as a digital light projector (DLP) can project entire images and thus form complex bubble patterns “in one shot” made of many bubbles simultaneously, opposed to serial, single bubble-based techniques. We would like to stress that the light intensity is several orders of magnitude lower compared to that required by various other light-based bubble techniques19,24. Furthermore, standard electrolysis results in the formation of clusters of microbubbles in an activated region, but we show that the addition of nanoparticles can prevent the formation of small satellite bubbles, such that one can, for the first time, form individually light-addressable bubbles from a few to hundreds of µm in diameter.

Next, we demonstrate that the bubbles also drive the assembly of particles in the suspension, which, in contrast to opto-thermally generated bubbles, does not rely on thermocapillary or thermal convection currents. Rather, the attraction of particles to the bubble surface can be attributed to a surface tension and concentration gradient near a shrinking bubble25. The microbubble patterns are shown to be versatile for assembly from metallic and polymer nanoparticles to extracellular vesicles, cells, and particle-cell hybrids. Finally, as a proof-of-concept, we demonstrate a microbubble-enabled nanosensor assay. The technology not only permits integration with bioassays but also enables the dynamic monitoring of bacterial cell activity in response to drugs in quasi-real time.

Results

Working mechanism, characterization, and optimization

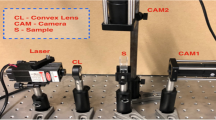

The experimental setup consists of a DLP device, which, illuminated by a 532 nm continuous wave laser, projects images onto a photoconductive α-Si:H substrate, where a PDMS well houses a sodium sulfate (Na2SO4)/nanoparticle solution and covered with a second FTO substrate as the counter electrode (Fig. 1a, b). An electric signal is applied, which drives the rapid formation of individual or large arrays of microbubbles at the projected light points (Fig. 1c). The application of both light and electric voltages is essential for the process; therefore, it is important to elucidate the working mechanism that generates microbubbles. We first determine the minimum required light intensity (MRLI) for the formation of bubbles.

Upon light illumination with an applied electric field, a microbubble quickly forms. The radius (r) increases from ~6 to ~13 μm as the light intensity increases in an E-field (Vbias: −5 V, Vpp: 12 V at 1.5 kHz, 0.1 M Na2SO4 concentration) (Fig. 2a); the power coefficient of 0.29 indicates the close-to-linear dependence of the bubble volume (V) on light intensity (Inset, Fig. 2a). The MRLI depends on the AC frequency and decreases from 12 to 0.74 W/cm2 when the AC frequency is lowered from 1 to 1.5 kHz (Vbias: −5 V, Vpp: 12 V, 0.1 M Na2SO4 concentration) (Fig. 2b). At a given AC E-field (Vpp: 12 V at 1.5 kHz, 0.1 M Na2SO4 concentration), the MRLI is also reduced ~2.72-fold with an increasing superimposed DC bias from −3.5 to −5.5 V (Fig. 2c). Optionally, 0.1 M Na2SO4 has been used here to facilitate the bubble formation, but as shown below with phospahte-buffered saline (PBS) solutions, this is not essential. It should be also noted that a constant positive DC bias up to 9 V (or a positive bias superimposed on a symmetric AC voltage) does not generate bubbles, which suggest that the α-Si:H film conducts electrons under a negative bias, similar to p-type Si, supported by a voltage sweep test from +4 to −4 V (Fig. S1). Increasing the electric conductivity of the electrolyte solution also promotes bubble generation, where the MRLI is lowered by over 4.5-fold from 7.4 to 0.16 W/cm2 (Vbias: −5 V, Vpp: 12 V at 1.5 kHz) with the increase of Na2SO4 concentration from 0.1 to 1.5 M (Fig. 2d).

a (top) Bubble radius linearly increases with laser intensity. (bottom) bubble volume vs laser intensity. Minimum required laser intensity as a function of b AC frequency, c DC bias, and d Na2SO4 electrolyte concentration. Unless stated otherwise, conditions used in characterization: 0.1 M Na2SO4 solution, −5 V DC/12 Vpp at 1.5 kHz AC E-field applied for ~225 ms, and 500 μm PDMS well. e Schematic of the overall setup and corresponding equivalent circuit. f Optimization of the limit of light intensity for bubble generation. Conditions: (Black) 0.5 M Na2SO4, −5 V, 12 Vpp at 1.5 kHz, 100 ms, PDMS 500 µm. (Orange) PBS solution, −9 V, 2Vpp at 250 Hz, 200 ms, PDMS 100 µm. (Green) 0.75 M Na2SO4, −5 V, 10 Vpp at 1.5 kHz, PMDS 100 µm. (Blue) 1.5 M Na2SO4 with CTAC and H2O2, −12 V DC pulse with 50% duty cycle, 150 ms, PDMS 257 µm. Error bars: standard deviation (s.d.). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The requirement of light and electric voltage suggests three possible bubble-creation mechanisms: (1) ohmic heating of the light-illuminated α-Si:H, (2) light-based thermal heating, and (3) light-controlled electrochemical hydrolysis. While thermal heating has been widely explored for making microbubbles20, this working mechanism requires a light intensity that is at least 5 orders of magnitude higher than in our system26. Further calculation and numerical simulation indicate that neither ohmic heating nor thermal heating can account for the observed bubble creation, the effects of which only increase the temperature by «1 K (SI Note 1 and Fig. S2).

The electrochemical-reaction mechanism, in contrast, explains the observed bubble evolution and dependence on the laser intensity, the AC frequency, the DC bias, and the electrolyte concentration very well (Fig. 2a–d). For instance, the volume increases linearly with the light intensity (inset, Fig. 2a), which is in agreement with the linear dependence of the photocurrent (ip) (of the α-Si:H substrate) participating in electrochemical reaction, with photon rate (N0) and thus light, as shown in the following Eq. (1)27:

where R, α, d, η, τ, and tt are the surface reflection, surface absorption coefficient and depth, electron-hole pair generation efficiency, recombination lifetime, and carrier transit time, respectively.

We further model the system as an equivalent electrochemical circuit, which consists of an electric double layer (EDL) with a capacitance of CSi, next to the photoconductive Si electrode with a resistance of RSi, an electrolyte solution with a resistance of Rs, and a second EDL next to the FTO counter electrode (CR) (Fig. 2e). Here, light turns on/off this electrochemical circuit path via controlling the Si-film’s local resistance. When light is switched on and RSi is significantly lowered (Fig. S3), an applied voltage is distributed across all the circuit elements, with a voltage drop proportional to each element’s resistance (impedance). For a capacitor, the impedance (Z = 1/(2πfC)) and the voltage drop (VC_SI) increase as the AC frequency (f) decreases. Therefore, we observe that a low AC frequency and a negative DC bias both prompt aid the HER as both effects enhance the voltage drop on the EDL capacitor. Owing to the same principle, a reduced electrolyte resistance (Rs) improves the HER by taking a smaller voltage drop and redistributing it to other circuit elements, including the EDL capacitor next to Si. The experimental observations, i.e., the improvement of the MRLI with the decrease of the AC frequency and the increase of negative DC bias and Na2SO4 electrolyte conductivity (Fig. 2b–d), all agree with the theoretical circuit-model analysis, and both indicate that light-controlled electrochemical reaction is the dominating mechanism for bubble generation.

It should also be noted that a DC field alone can also generate microbubbles. However, we study the AC E-field due to its importance in understanding the working mechanism and practically employ this strategy for robust bubble creation, as we find that the Si surface may more easily degrade with DC or low-frequency AC fields. This can be attributed to the FTO layer partially exposed to the solution due to the voids/grain boundaries in the 200 nm α-Si:H (Fig. S3), in which case, the FTO competes with the reactions on the light-activated Si surface, generating bubbles and damaging the Si layer in the process. The use of an AC field, on the other hand, lowers the conductivity of the Si’s capacitive component, and hence the total resistance of the Si. While this also reduces the effective voltage applied to the EDL, the reactions are shifted more to the Si, with fewer reactions taking place near the FTO layer. Indeed, experimentally, at a 10 kHz AC field, we observe that the Si maintains its integrity. For the electrochemical formation of bubbles, we therefore choose an optimized AC-frequency and further add a negative DC bias to obtain the best MRLI value that preserves the surface performance. However, it should be noted that there isn’t a universal frequency at which Si becomes permanently stable, since its integrity can depend on factors like film thickness, deposition method, and surface treatment. For the specific silicon films used in our study, under the employed electric field conditions, we observed stable Si performance and achieved optimized efficiency in microbubble generation.

The understanding of the bubble formation mechanism assists us in rationally improving the efficiency of the electrochemical system by adding hydrogen peroxide and surfactants (CTAC) for a lower redox voltage and surface tension, respectively (Fig. 2f, SI Note 2). With all conditions optimized, it only requires a light illumination of ~0.1 W/cm2, corresponding to the level of sunlight, to create a microbubble (532 nm laser; electrolyte: 1.5 M Na2SO4, 1.25 mg/mL CTAC, 5% H2O2; Vpp: 12 V at 1.5 kHz, square wave, Vbias: −6 V) Even in PBS solutions, as low as ~0.22 W/cm2 is needed for bubble creation (532 nm light, Vpp: 2 V at 1.5 kHz, Vbias: −9 V). For biological applications, solutions such as PBS are recommended, without the addition of CTAC or H2O2 due to potential biocompatibility issues. Overall, this technique exhibits a much higher energy efficiency (>2–3 orders of magnitude) compared to other current bubble generation techniques listed in Table S2. This work, although using a similar setup to optoelectronic tweezers28, the mechanism is distinct, which generates bubbles and uses them for manipulation. In addition, our electrochemical bubble-based approach is fully compatible with high-ionic-strength solutions, overcoming the limitations of dielectrophoresis-based manipulation under such conditions.

Fast, parallel, versatile microbubble patterning

The microbubble patterns can be rapidly refreshed to form dynamic movies. Demonstrations include a bubble-made longhorn image, the symbol of UT Austin, which is overlaid on the map of the state of Texas (Fig. 3a, b, Video S2), the logo of the Max Planck Society (Fig. 3c, d, Video S2), as well as animations, including a running horse (Video S3), a continuously expanding circle and fireworks (Video S4).

High-precision, bubble-actuated nanoparticle printing

For capturing and assembling colloidal nanoparticles, it is crucial to control the surface state of the substrate and the concentration of the nanoparticle suspension. For instance, a native α-Si:H surface can only support truncated spherical hydrogen bubbles that results in coffee-ring particle patterns (Fig. S4) due to the hydrophobic nature of both hydrogen gas and α-Si:H29,30. Without nanoparticles in solution (or at a low concentration), multiple, instead of single, bubbles form under a light spot (Fig. 4a, inset and Video S5)30, which is detrimental to precise particle printing. The formation of single or multiple bubbles can be understood when considering the thermodynamic factors driving the bubble formation (SI Note 3). Nanoparticles are attracted to the bubble interface25, captured, and finally deposited at a single spot during its shrinkage (Fig. 4b, inset, SI Note 4).

a Simultaneous generation of microbubbles over a larger area, respectively, with nanoparticles in solution (inset without nanoparticles in solution). b A microbubble is generated rapidly, within sub-milliseconds (a few µm) to less than a second (~10 µm), and (inset) shrinks over tens of seconds. Results of multiple individual bubbles show consistent behaviors. c The size of the nanoparticle assembly can be controlled by the bubble size from a few µm to >100 µm. Formation of nanoparticle-assemblies in an array by d the generation of an array of microbubbles (shown as an optical micrograph) in a solution containing polystyrene nanospheres, followed by the e shrinkage of the microbubble arrays that result in ordered nanoparticle assemblies. f The location of the nanoparticle assembly is within 1.0 ± 0.6 μm relative to the center of the bubble position. Scale bars: 100 μm. Error bars: standard deviation (s.d.). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The above observations, together with further considerations of surface charge and particle density (SI Note 5), indicate that surface modification is needed to enable the formation of single-spot particle aggregates. We first modify the α-Si:H surface with positive charges using an oxygen plasma followed by poly-diallyldimethylammonium chloride (PDDA) coating. The efforts generate single, size-controlled, and position-defined bubble patterns at the point of the incident light with a positional accuracy of 2.45 ± 1.08 µm (Fig. S5). The diameter of a bubble increases during the application of an E-field (Fig. 4b) (Vbias: −5 V, Vpp: 12 V at 1.5 kHz) with the power-law coefficient determined as 0.44, close to 0.5 for gas-diffusion controlled bubble growth (Fig. 4c and SI Note 6)31,32. The PDDA functionalization of Si further enables single-point contact of a bubble on the substrate; it also effectively helps in fixing the nanoparticles to the oppositely charged substrate (200-nm polystyrene nanospheres: 6–8 × 1010/ml; Na2SO4 to 0.66–0.75 M) (Fig. 4d, e and Video S6). In addition, the microbubbles shrink symmetrically during the process so that the nanoparticle clusters can be precisely localized to within 1.03 ± 0.61 μm of the microbubble center. This permits positioning to an order-of-magnitude smaller feature sizes compared to the size of the light pattern and bubbles (Fig. 4f).

The electrochemical microbubble platform can be used to reliably deposit a variety of inorganic and biological particles, ranging from 200 nm to several micrometers in size, onto the Si surface. The assemblies remain firmly attached, even when the surface is rinsed with DI water. The particle–particle and particle–surface adhesion can be attributed to electrostatic and van der Waals forces after bubble shrinkage (Fig. 4e). However, when a new microbubble is formed nearby, then the assembled particle cluster can be detached and repositioned, specifically, during bubble shrinkage. Microbubbles may thus not only be used to form stable assemblies, but also be used to reconfigure the particle organization.

Microbubbles for rapid programmable nanoparticle assembly

While small light spots can be used to create corresponding individual microbubbles with precise position control, simple large-area light patterns can also be applied to simultaneously generate many microbubbles for rapid, large-scale, programmable particle assembly (Fig. 5, Video S7). An average light intensity as low as 0.15 W/cm2 is sufficient to generate bubbles (Vbias: −5 V, Vpp: 12 V at 1.5 kHz, 0.75 M Na2SO4). A single bar of light can be used to obtain an evenly spaced chain of bubbles (Fig. 5a), where the spacing between bubbles can be controlled by the total E-field-application time (Fig. 5b). Depending on the sizes of the light pattern and bubbles, different arrangements of the patterns can be generated (inset of Fig. 5b, blue and green rectangles). When broadening the width of the light pattern, the bubbles first increase in size and then a second row of bubbles forms (Fig. S6). Further, the bubble size and hence the bubble lifetime (time for a bubble to collapse after growth) can be varied over three orders of magnitude from 23 to 24 s (Fig. 5c), with a corresponding increase of the number of deposited particles (Fig. S7). The nanoparticle assembly arises at the microbubble and by choosing appropriate parameters based on the above observations, we achieve programmable nanoparticle patterns consisting of evenly spaced spots along defined patterns (Fig. 5d, e).

a The interparticle distance of the deposits is controlled by the bubble size. Dependence of b (Black) bubble radius and (Green) separation of bubbles as a function of the E-field duration, and c bubble volume and bubble lifetime. Particle clusters formed by (d) circular and (e) rectangular light patterns (and the corresponding microbubbles). Simultaneously deposited particles (in the same color) are denoted in white, green, and yellow; enhanced images. Scale bars: 100 μm. Error bars: standard deviation (s.d.). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Large-scale bubble printing

Distinct from state-of-the-art printing techniques, opto-electrochemical bubble printing allows easy, massive, biocompatible parallel assemblies. We demonstrate the printing of Ag nanoparticles (40 nm), polystyrene spheres (200 nm), and live bacterial cells (1–2 µm) as well as assemblies of 200-nm extracellular vesicles in one exposure (Fig. 6), and a 2.56-mm-long nanosphere lattice in only 7 light exposures (Fig. S8). The aggregates are typically a few micrometers in size, and the deposition contrast can be further enhanced by optimizing the Si surface functionalization (Fig. S9a–c). These results suggest a facile approach to for instance enrich biologics in a complex solution by creating microbubbles and selectively depositing the desired species, assisted by surface-particle interactions. Bacterial cells, for example, assemble on positively charged silicon but redisperse into the solution when the surface is hydrophobic or negatively charged, while extracellular vesicles can be captured by hydrophobic surfaces33.

Microbubble assembly of diverse structures ranging from a metallic silver nanoparticles (40 nm), b bacterial cells (E-coli) (1–2 mm), to c 200 nm extracellular vesicles from breast cells (enhanced image); original image in Fig. S13. Scale bars: a 1 μm, b 3 μm, c 50 μm, and 25 μm in inset.

Microbubble platform for bioassays

In addition, the rapid co-assembly of cells and nanosensors for continuous profiling of biomarkers can be achieved with microbubbles. As a proof of concept, we generate microbubbles in solution containing both bacterial cells and plasmonic nanosensors and co-assemble these in defined cell clusters, ranging from individual to tens of cells, on the substrate (Fig. 7a, b). The microbubble assembly exhibits excellent biocompatibility (>93%), as confirmed by standard trypan blue cell-staining of Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells after being exposed to microbubbles (see “Methods” section). Here, we focus on a bacteria–nanoparticle sensor array to highlight both the biological relevance and the unique strengths of our microbubble platform compared to the other technologies (Tables S3 and S4). The array enables the continuous monitoring of metabolite release from bacteria and provides biological insights into bacterial antibiotic resistance. Different cells can be assembled, such as Escherichia coli and Bacillus(B.) Subtilis, which remain highly active as shown by their strong, dynamic, and heterogenous metabolite release, without signs of degradation during the 2-h long continuous monitoring by surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) (Fig. S10).

Nanosensors: Ag-coated nanospheres; cells: Gram-positive B. Subtilis. Controlled cell counts in the hybrid arrays are determined by bubble size, ~98 µm for (a) and ~54 µm for (b). Continuous metabolite profiling up to 3 h in response to vancomycin for (c) large clusters in (a), and d small clusters in (b), exhibits (e) distinct diminishing time depending on average cell counts analyzed with Mann–Whitney U Test. Island-large clusters: Z value = −1.98; Large clusters-small clusters: Z value = −2.78; Islands-small clusters: Z value = −2.72. Raman signals in green and red for metabolites and the nanosphere sensors, respectively (c) d shows 4 representative measurement results. Additional data for (c, d) are available in Fig. S14. Scale bars: (a) 5 μm and (b) 2 μm. Error bars: Standard deviation (s.d.). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Here, we evaluate B. Subtilis in response to Vancomycin, an antibiotic drug commonly applied to Gram-positive bacteria. The SERS-active nanosensors are made of Ag-NPs synthesized on polystyrene (PS) nanospheres (Fig. S11, “Materials and Methods”), which are deposited along with B. Subtilis cells during the microbubble printing. We successfully detect the evolving metabolite signals from assembled arrays in a prescribed manner, as seen in the 4 representative SERS measurements in Fig. 7c, d. SERS reveals metabolites that are associated with end products of the purine cycle, including hypoxanthine, xanthine, uric acid, guanine, AMP and adenine, the metabolism of which is attributed to nutrient-deprived bacteria (Figs. 7c, d,S12 and S13; note that peaks associated with various metabolites shown in these figures are listed in Table S5, which provides Raman peak positions of purine derivatives identified in the literature)34.

Overall, we observe consistent strong heterogeneity of metabolites in terms of species and dynamics across cell assemblies ranging from a single cell to large aggregates with tens to hundreds of bacterial cells. The smaller the assembly size, the earlier the metabolite activity disappears in the presence of excess antibiotic drugs. Specifically, a small bacterial assembly with a few cells, e.g., 5 cells, remains active in releasing metabolites for ~35 min; the activity extends to ~75 min for tens of cells, e.g., 30, and ~120 min for bacterial islands or films with hundreds of cells (Fig. 7e). A detailed analysis is included in SI Note 7. The time-dependence of the drug response on cell-assembly size, discovered with this platform, could likely be attributed to the physical coverage and protections among cells with increased counts as well as their chemical communication35. Moreover, with a greater number of cells deposited in an assembly, the chance of including cells with antibiotic resistance increases, as well as the observed drug-response time. The microbubble technique is general and versatile and can thus be used to establish biosensing platforms for cell biology, drug screening, testing for precision therapeutics, and cell-cell communication studies.

Summary

We introduce an opto-electrochemical technique that permits the room-temperature formation and patterning of microbubbles with defined size in a parallel and scalable fashion. The required low light intensity (~0.1 W/cm2), a few orders of magnitude less than what has been reported previously, triggers the electrolysis-driven bubble formation. The size of the microbubbles determines their lifetime, and the preparation of the substrate enables the formation of well-defined microbubbles. The use of nanoparticles in the suspension facilitates the growth of single bubbles, which guides the assembly of nanoparticle clusters onto a substrate. The nanoparticle aggregates can be positioned with an accuracy of ~1 µm, relative to the bubble center. The microbubble technique presented herein is general and can be used to quickly form precise assemblies from a range of structures and materials with ease, including polymeric or metallic nanoparticles, extracellular vesicles, and live biological cells. For demonstration, we pattern arrays of plasmonic-active nanosensor-cell hybrids and record the dynamic metabolite release from bacterial cells of different assembled sizes for several hours. The biocompatible microbubble assembly process also permits the dynamic evaluation of controlled microbial clusters in response to antibiotics, which facilitates research into cell signaling, metabolism, and drug development, including antibiotics. The microbubble-based assembly offers several key advantages for cell manipulation and patterning. It enables one-step trapping and attachment of cells to a substrate, without requiring the complex microfabrication typically needed for microfluidic devices, valve-based platforms, or physical traps. Additionally, the bubble-based system can capture a wide variety of particles across a broad range of sizes and properties, making it particularly effective for assembling cell/nanosensor hybrids. A detailed comparison with other state-of-the-art techniques, such as microfluidic processing36,37 and active cell trapping34,36,38, is presented in Table S3 of SI. We expect that the fast, massively parallel small-particle assembly method presented herein, will enable further applications in nanomanufacturing39, nanophotonic patterning40, nanorobotics41,42,43, biosensing44,45, single-cell biology46, and hybrid device fabrication44. In particular, this research overcomes longstanding challenges in obtaining microbubble patterns with both high precision and high throughput. These unique capabilities make for general soft microtools and pave the way for cell-sensor-stimulus platforms for cell biology, drug screening, cell-cell communication studies and precision therapeutics.

Methods

Experimental setup

In a typical experiment, a 100–250 μm-thick PDMS well (1.5 mm in diameter) is placed on the α-Si:H surface that has been cleaned by oxygen plasma or UV-ozone treatment. A Na2SO4 solution (0.18 μL) is mixed with the nanoparticles that are to be deposited and then dispersed into the well. The well is sealed with a FTO glass, which serves as the counter-electrode. The FTO on the α-Si:H layer serves as the working electrode. An electric voltage is applied between the working and counter electrodes. The light-illuminated areas become conducting and here the bubbles are formed by electrolysis.

Characterization of the minimally required laser intensity

A single laser beam with a diameter of 7.22 μm is used for the characterization of the bubble formation, measured by the 10/90 knife-edge method (Fig. S12). Prior to the bubble generation, the surface of the silicon was gently cleaned using DI water and IPA. Unless stated otherwise, a 0.1 M Na2SO4 solution, −5 V DC / 12 Vpp at 1.5 kHz AC E-field was applied for ~225 ms using a 500 μm PDMS well for characterization purposes. The electrolyte solutions were prepared before use from a 1.5 M Na2SO4 stock solution. When testing the effects of H2O2 and CTAC these molecules were added to achieve a final concentration of 5% and 1.25 mg/mL, respectively.

Microbubble patterning and particle deposition

For bubble-driven nanoparticle assembly, the substrate surface is first cleaned with DI water and IPA. This is followed by a treatment with oxygen plasma for 1 min at 50 sccm, 50 W power, or with a UVO cleaner for 30 min. A 4% PDDA solution is then applied to the surface for 3 m to positively charge the surface and increase the hydrophilicity, after which the surface is washed with DI water and gently dried using a flow of nitrogen gas. A 0.66–0.8 M Na2SO4 solution containing 200 nm polystyrene nanoparticles is added to the PDMS well applied on the surface. A light pattern is projected via a digital mirror array controlled by a custom-made python program using a continuous 532 nm laser (DJ532-40, Thorlabs). An E-field of −5 V DC and 12 Vpp AC voltage at 1.5 kHz is applied between the working electrode underneath the α-Si:H surface and the counter FTO electrode. Microbubble patterns were formed with 15–50 ms AC bursts, while the bubble-assisted nanoparticle assembly were formed with bursts lasting 225–750 ms.

CHO cell culturing and viability testing for biocompatibility determination

CHO cells were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and maintained in an incubator at a 37 °C, 5% CO2 environment. After culturing, the cells were detached from the culturing flask and diluted to achieve a concentration of 106 cells/mL. A cell solution was applied to a PDMS well on top of PDDA-treated α-Si:H, and bubbles were formed throughout the sample surface following standard microbubble patterning procedures, as described above. Once the bubbles are no longer present, trypan blue was added to the solution. The viability of the cells was determined by checking whether the cells are stained with the dye after waiting 3–5 min. To ensure accurate assessment, only cells that in direct contact with microbubbles were considered, and over 360 cells were analyzed, showing a livability of >93%.

Bacterial microbubble assembly and characterization

For bubble-based live E. coli deposition, the E. coli was washed with DI water for 3 times and concentrated to 4.77 × 107 cells/mL. The concentrated solution was mixed with a 1 M Na2SO4 stock solution 1:1 to facilitate bubble growth, resulting in a 10×, 0.5 M Na2SO4 E-coli solution. For SEM imaging, the original E. coli was fixed via washing with a 7.4 PBS solution 2 times and submersing in a 1:3 acetic acid:EtOH solution for 10 min47. Then, the solution was washed by PBS solution twice and finally washed by DI water and concentrated to obtain a 20× higher E. coli cell density. The concentrated solution was mixed with a 1 M Na2SO4 stock solution 1:1 to facilitate bubble growth, resulting in a 10×, 0.5 M Na2SO4 E. coli solution. After depositing the E. coli with bubbles, the solution was gently exchanged with DI water 10 times to suppress random deposition of E. coli on the surface, then dried. Before SEM imaging, a thin layer of Au/Pd was deposited to improve the imaging of the samples.

Fabrication of SERS-active Ag-on-PS nanospheres, microbubble co-assembly of SERS-nanosensor/B. Subtilis-cell hybrids and dynamic profiling of metabolites with SERS

Dense and uniform Ag nanoparticles were synthesized on commercial 500 nm PS nanospheres (Alfa Aesar, 42714) for SERS nanosensing by using a previously reported method with minor modification45,48,49. First, 1.5 ml of 0.06 M NH₄OH solution was injected into a centrifuge tube, followed by 0.75 ml of 0.06 M AgNO₃ to obtain a stable Ammonia-Silver Ion Complex (solution A). Then, 98 µl of the PS spheres solution (2.5 wt%) was added to solution A and shaken for thorough mixing. An additional 0.75 ml of 0.06 M AgNO₃ was gradually added to solution A. The silver oxide core would form with the solution injection, turning the solution color from white to light yellow (solution B), which was shaken for another 45 min for ripening. Afterward, 2 ml of solution B was removed, leaving 1 ml in the tube to allow further growth of the silver nanoparticles. Then, 10 ml of PVP (2 × 10−5 M in ethanol, M.W. 40,000) was added to the tube as a reductant and stabilizer. The tube was then placed in a 70 °C oven for 7 h to produce dense silver particles with a diameter of around 50 nm on the PS nanospheres. To remove the remaining PVP for clear and sensitive SERS detection, the particles were stored in a 0.1 M KCl solution for a day and treated with a 0.025 M NaBH4 solution for 10 min and then washed two times with DI water before use. B. Subtilis were washed for 5 times in DI water and concentrated before use (4.3 × 108 cells/mL). The particles, cells, and a 1 M Na2SO4 solution were mixed with a volume ratio of 1:1:1 for microbubble deposition. After deposition, the solution was removed and replaced with a Vancomycin solution (8 μg/mL) for SERS testing.

Generation of MDA-MB-231-PalmGRET stable cell lines

To generate the MDA-MB-231-PalmGRET stable cell line, pLenti CMV Puro DEST plasmids encoding PalmGRET (Plasmid #158221; Addgene) were packaged into lentiviruses, then transduced into MDA-MB-231cells. Next, puromycin selection (10 μg/ml, Invitrogen) was conducted to eliminate non-transduced cells. Additional selection using fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed to screen for cells that highly expressed PalmGRET.

Collection of MDA-MB-231-PalmGRET extracellular vesicles

Cells were grown in T225 flasks (Falcon) until they reached full confluency. Next, cells were cultured in serum free medium (Corning) for 22–24 h. The medium was collected and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min followed by a centrifugation step at 2500 × g for 15 min to discard cellular debris and large particles. The supernatant was collected and continuously ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g and 4 °C for 2 h. The EV pellets were suspended in PBS.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within this paper and its Supplementary Information Figures. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gao, Y., Wu, M., Lin, Y., Zhao, W. & Xu, J. Acoustic bubble-based bidirectional micropump. Microfluid. Nanofluidics 24, 29 (2020).

Tovar, A. R. & Lee, A. P. Lateral cavity acoustic transducer. Lab Chip 9, 41–43 (2009).

Orbay, S. et al. Mixing high-viscosity fluids via acoustically driven bubbles. J. Micromech. Microeng. 27, 015008 (2017).

Ozcelik, A. et al. An acoustofluidic micromixer via bubble inception and cavitation from microchannel sidewalls. Anal. Chem. 86, 5083–5088 (2014).

Ahmed, D., Mao, X., Shi, J., Juluri, B. K. & Huang, T. J. A millisecond micromixer via single-bubble-based acoustic streaming. Lab Chip 9, 2738–2741 (2009).

Destgeer, G. et al. Adjustable, rapidly switching microfluidic gradient generation using focused travelling surface acoustic waves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 023506 (2014).

Ahmed, D. et al. Acoustofluidic chemical waveform generator and switch. Anal. Chem. 86, 11803–11810 (2014).

Jeong, J., Jang, D., Kim, D., Lee, D. & Chung, S. K. Acoustic bubble-based drug manipulation: carrying, releasing and penetrating for targeted drug delivery using an electromagnetically actuated microrobot. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 306, 111973 (2020).

Klibanov, A. L., Shevchenko, T. I., Raju, B. I., Seip, R. & Chin, C. T. Ultrasound-triggered release of materials entrapped in microbubble-liposome constructs: a tool for targeted drug delivery. J. Control. Release 148, 13–17 (2010).

Ma, Z. et al. Spatial ultrasound modulation by digitally controlling microbubble arrays. Nat. Commun. 11, 4537 (2020).

Yuan, K., De La Asunción-Nadal, V., Jurado-Sánchez, B. & Escarpa, A. 2D nanomaterials wrapped janus micromotors with built-in multiengines for bubble, magnetic, and light driven propulsion. Chem. Mater. 32, 1983–1992 (2020).

Ren, L. et al. 3D steerable, acoustically powered microswimmers for single-particle manipulation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax3084 (2019).

Li, J., Mayorga-Martinez, C. C., Ohl, C. D. & Pumera, M. Ultrasonically Propelled Micro- and Nanorobots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2102265 (2022).

Qiu, T. et al. Wireless acoustic-surface actuators for miniaturized endoscopes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 42536–42543 (2017).

Li, Y., Liu, X., Huang, Q., Ohta, A. T. & Arai, T. Bubbles in microfluidics: an all-purpose tool for micromanipulation. Lab Chip 21, 1016–1035 (2021).

Goyal, R., Athanassiadis, A. G., Ma, Z. & Fischer, P. Amplification of acoustic forces using microbubble arrays enables manipulation of centimeter-scale objects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 254502 (2022).

Ghosh, S. et al. Directed self-assembly driven mesoscale lithography using laser-induced and manipulated microbubbles: complex architectures and diverse applications. Nano Lett. 21, 10–25 (2021).

Gargiulo, J., Cerrota, S., Cortés, E., Violi, I. L. & Stefani, F. D. Connecting metallic nanoparticles by optical printing. Nano Lett. 16, 1224–1229 (2016).

Armon, N. et al. Continuous nanoparticle assembly by a modulated photo-induced microbubble for fabrication of micrometric conductive patterns. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 44214–44221 (2017).

Lin, L. et al. Bubble-pen lithography. Nano Lett. 16, 701–708 (2016).

Fan, Q., Hu, W. & Ohta, A. T. Localized single-cell lysis and manipulation using optothermally-induced bubbles. Micromachines 8, 121 (2017).

Chen, C., Karshalev, E., Guan, J. & Wang, J. Magnesium-based micromotors: water-powered propulsion, multifunctionality, and biomedical and environmental applications. Small 14, 1704252 (2018).

Li, D., Liu, Y., Yang, Y. & Shen, Y. A fast and powerful swimming microrobot with a serrated tail enhanced propulsion interface. Nanoscale 10, 19673–19677 (2018).

Zhao, C. et al. Theory and experiment on particle trapping and manipulation via optothermally generated bubbles. Lab Chip 14, 384–391 (2014).

Yang, X., Baczyzmalski, D., Cierpka, C., Mutschke, G. & Eckert, K. Marangoni convection at electrogenerated hydrogen bubbles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 11542–11548 (2018).

Baffou, G., Polleux, J., Rigneault, H. & Monneret, S. Super-heating and micro-bubble generation around plasmonic nanoparticles under cw illumination. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 4890–4898 (2014).

Loveland, R. J., Spear, W. E. & Al-Sharbaty, A. Photoconductivity and absorption in amorphous Si. J. Non Cryst. Solids 13, 55–68 (1973).

Chiou, P. Y., Ohta, A. T. & Wu, M. C. Massively parallel manipulation of single cells and microparticles using optical images. Nature 436, 370–372 (2005).

Sakuma, G., Fukunaka, Y. & Matsushima, H. Nucleation and growth of electrolytic gas bubbles under microgravity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 7638–7645 (2014).

Ma, Z., Joh, H., Fan, D. E. & Fischer, P. Dynamic ultrasound projector controlled by light. Adv. Sci. 9, 2104401 (2022).

Westerheide, D. E. & Westwater, J. W. Isothermal growth of hydrogen bubbles during electrolysis. AIChE J. 7, 357–362 (1961).

Higuera, F. J. A model of the growth of hydrogen bubbles in the electrolysis of water. J. Fluid Mech. 927, A33 (2021).

Huang, S., Wang, L., Bruce, T. F. & Marcus, R. K. Isolation and quantification of human urinary exosomes by hydrophobic interaction chromatography on a polyester capillary-channeled polymer fiber stationary phase. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 411, 6591–6601 (2019).

Weiss, R. et al. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of microorganisms: limitations and applicability on the single-cell level. Analyst 144, 943–953 (2019).

Vega, N. M. & Gore, J. Collective antibiotic resistance: mechanisms and implications. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 21, 28–34 (2014).

Lin, H. Y. et al. On-line SERS detection of single bacterium using novel SERS nanoprobes and a microfluidic dielectrophoresis device. Small 10, 4700–4710 (2014).

Kogawa, M. et al. Single-cell metabolite detection and genomics reveals uncultivated talented producer. PNAS Nexus 1, pgab007 (2022).

Baron, V. O. et al. Real-time monitoring of live mycobacteria with a microfluidic acoustic-Raman platform. Commun. Biol. 3, 236 (2020).

Flauraud, V. et al. Nanoscale topographical control of capillary assembly of nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 73–80 (2017).

Yeom, J. et al. Chiral templating of self-assembling nanostructures by circularly polarized light. Nat. Mater. 14, 66–72 (2015).

Venugopalan, P. L., Esteban-Fernández de Ávila, B., Pal, M., Ghosh, A. & Wang, J. Fantastic voyage of nanomotors into the cell. ACS Nano 14, 9423–9439 (2020).

Fischer, P. & Ghosh, A. Magnetically actuated propulsion at low Reynolds numbers: towards nanoscale control. Nanoscale 3, 557–563 (2011).

Law, J. et al. Micro/nanorobotic swarms: from fundamentals to functionalities. ACS Nano 17, 12971–12999 (2023).

Chen, P. et al. Multiplex serum cytokine immunoassay using nanoplasmonic biosensor microarrays. ACS Nano 9, 4173–4181 (2015).

Li, H. et al. Precise electrokinetic position and three-dimensional orientation control of a nanowire bioprobe in solution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1213–1221 (2023).

Baysoy, A., Bai, Z., Satija, R. & Fan, R. The technological landscape and applications of single-cell multi-omics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 695–713 (2023).

Chao, Y. & Zhang, T. Optimization of fixation methods for observation of bacterial cell morphology and surface ultrastructures by atomic force microscopy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 92, 381–392 (2011).

Xu, X., Kim, K., Li, H. & Fan, D. L. Ordered arrays of Raman nanosensors for ultrasensitive and location predictable biochemical detection. Adv. Mater. 24, 5457–5463 (2012).

Xu, X., Kim, K. & Fan, D. Tunable release of multiplex biochemicals by plasmonically active rotary nanomotors. Angew. Chem. 127, 2555–2559 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the support of the National Science Foundation (grants# 2219221, 2506603, 1930649). We also thank the National Institutes of Health (grant R43ES037145) and the UT-Austin Portugal Program for supporting bacterial study. P.F. thanks the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) grant EXC-2082/1-390761711. P.F. and Z.M. acknowledge financial support from the Max Planck Society. S.-Y.Z. and K.-J.L. acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (grant 1R01CA237250). We thank Prof. Jianping Fu of the University of Michigan for the helpful discussion on drug screening.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J., D.E.F., and P.F. contributed to the scientific interpretation, analysis, and preparation of the manuscript. H.J., B.L., and S.-i.H. carried out the design, experimentation, data collection, and analysis. Z.M. performed material characterization. K.-J.L. and S.-Y.Z. fabricated and characterized the extracellular vesicles. The project was supervised by D.E.F.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ines Oberhuber, Simone Schuerle, Charles Shields IV, and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Joh, H., Lian, B., Hsueh, Si. et al. Massively parallel microbubble nano-assembly. Nat Commun 16, 6743 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62070-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62070-9