Abstract

Quantum chaos is central to understanding quantum dynamics and is crucial for generating random quantum states, a key resource for quantum information tasks. In this work, we introduce a new class of quantum many-body dynamics, termed pseudochaotic dynamics. Although distinct from chaotic dynamics, out-of-time-ordered correlators, the key indicators of quantum chaos, fail to distinguish them. Moreover, pseudochaotic dynamics generates pseudorandom states that are computationally indistinguishable from Haar-random states. We construct pseudochaotic dynamics by embedding a smaller k-qubit subsystem into a larger n-qubit system. We demonstrate that a subsystem of size \(k=\omega (\log n)\) is sufficient to induce pseudochaotic behavior in the entire n-qubit system. Furthermore, we construct a quantum circuit exhibiting pseudochaotic dynamics and demonstrate that it generates pseudorandom states within \({{{\rm{polylog}}}}(n)\) depth. In summary, our results constitute the discovery of new quantum dynamics that are computationally indistinguishable from genuine quantum chaos, which provides efficient routes to generate useful pseudorandom states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum many-body dynamics represents a forefront of our modern understanding of quantum mechanics with profound implications across fields such as quantum information science1,2,3,4, thermodynamics5,6,7, condensed matter physics8,9,10, and high-energy physics11,12,13. However, due to the hardness of simulating the dynamics, their properties are still not fully understood. One area of particular interest is quantum chaotic dynamics, with prototypical examples including the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev (SYK) model14,15 and random quantum circuits16. A defining characteristic of chaos, both in classical and quantum systems, is the butterfly effect17,18,19, which asserts that local information in an initial state quickly scrambles across an exponentially large space. Since tracking this scrambled information requires exponential resources, simulating such quantum dynamics using classical computers is generally intractable. This challenge has spurred the use of quantum devices to study quantum chaos4,20,21 with potential applications in quantum supremacy tasks22,23,24,25. Discovering new classes of quantum many-body dynamics could similarly yield unexpected insights across these fields.

A deep connection between quantum chaos and randomness offers a promising route for generating ensembles of quantum states26,27,28,29 close to uniformly random (i.e., Haar-random) quantum ensembles. As a quantum cryptographic primitive, Haar-random quantum ensembles have crucial applications in quantum information science including quantum cryptography30,31, quantum estimation theory32,33,34, and quantum complexity theory35. However, preparing a genuine Haar-random ensemble of quantum states demands exponentially deep circuits36, which current technology struggles to achieve. The recent formulation of pseudorandom quantum states37 has shed light on this problem by considering an ensemble of quantum states that even quantum computers cannot distinguish from Haar-random states within limited computation time, i.e., computationally indistinguishable, but are preparable with lower circuit depth. The pseudorandomness in quantum states and associated computational indistinguishability of various quantum resources like entanglement38, magic39, and coherence40, have found a wide range of applications in quantum information processing41,42,43,44,45.

Motivated by these previous developments, we introduce a new class of quantum many-body dynamics for quantum simulations, called ‘pseudochaotic dynamics,’ capable of generating pseudorandom states. Although pseudochaotic dynamics are not chaotic and thus fundamentally distinct from conventional chaotic dynamics, we demonstrate that they are surprisingly indistinguishable within limited computation time from chaotic ones through the defining metric of chaos, namely out-of-time-ordered correlators (OTOCs)46, which quantify the butterfly effect.

In this work, we provide a systematic construction of these dynamics by embedding the unitary dynamics of a k-qubit subsystem into the entire n-qubit quantum system. Remarkably, this approach is feasible even with a very small subsystem size with \(k=\omega (\log n)\) and a circuit depth of \(\omega (\log n)\). This depth without any conditions almost touches the shallowest depth for generating pseudorandom states made by assuming cryptographic assumptions38,47. Moreover, the subsystem’s dynamics need not be inherently chaotic, which contrasts strongly with our common understanding of quantum chaos. We also discuss how the properties of pseudochaos are related to coherence generated by the subsystem dynamics40, and other quantum resources studied in the context of pseudorandom quantum states, such as entanglement38, magic39.

Results

Pseudochaotic dynamics

We define pseudochaotic dynamics as a non-chaotic unitary time evolution with i. computational indistinguishability from chaotic time evolution via OTOCs, and ii. capability to generate pseudorandom states. The latter implies that the pseudochaotic dynamics loses its initial information over a certain time scale as like the former does.

Computational indistinguishability via OTOC

The OTOC of a unitary operator U with Pauli like local operators V and W, V2 = W2 = 1, at infinite temperature is46

This can be estimated in experiments by reverse time evolution or interferometric measurements48,49. OVW(U) can be thought of as an observable when we replace the trace operation by the inner product with the Bell pair state in the double copy space, and thus it can be estimated by measurements in that space.

In quantum chaotic systems, OVW(U) converges to zero as the time interval increases for any local operators V and W. In addition, the values of these converged OTOCs decrease exponentially with the system size19. Detecting this characteristic exponential decay in system size requires the uncertainties in the estimated OTOCs to also decay exponentially. However, if the number of realizable copies is limited to a polynomial in the system size, the uncertainties in estimating the OTOCs by a poly-time quantum algorithm scale at best as Ω(1/poly(n)) when the algorithm saturates the Heisenberg limit, making it impossible to observe the exponential decay of the OTOCs. Consequently, any dynamics with OTOCs scaling negligibly, i.e., OVW ~ o(1/poly(n)), for all time t ≥ t* for some constant t* > 0 becomes computationally indistinguishable from chaotic one by OTOCs. We take this indistinguishability as one criterion for U to be pseudochaotic.

Capability to generate pseudorandom states

An ensemble of chaotic unitary operators can generate Haar-random states50. We require that pseudochaotic dynamics produces a pseudorandom state ensemble37 in the same way. This capability of generating pseudorandom states is another manifestation of the indistinguishability of pseudochaotic dynamics from chaotic ones. For this, we note that a pseudorandom state ensemble is an ensemble that cannot be distinguished from a truly random ensemble using only a polynomial number of measurements and a poly-time quantum algorithm. This immediately implies that an ensemble of states generated through pseudochaotic dynamics as we explained above should be indistinguishable from one generated by fully chaotic dynamics within polynomial copies by any polynomial time (quantum) algorithm. Figure 1a illustrates this concept of the pseudochaotic dynamics.

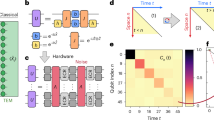

a A quantum computer simulates dynamics either from a chaotic ensemble or a pseudochaotic ensemble. Any poly-time quantum algorithm \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) on a polynomial number of copies with poly-time classical post-processing fails to pin down whether the dynamics is chaotic or not by measuring OTOC. An example of pseudochaotic dynamics is obtained by conjugating the dynamics in a subspace by a random permutation. To make this dynamics pseudochaotic, the dimension of the subspace 2k should be given by \(k=\omega (\log n)\) with the number of qubits n, which is much smaller than the entire space dimension 2n. A circuit implementation of this dynamics requires \({{{\rm{polylog}}}}(n)\) depth with all-to-all connectivity. b We can schematically classify how the late-time 1/OVW scales with n into three different regimes. In a chaotic system (orange color), this scaling is exponential in n. For a system with local scrambling (blue color), the scaling is at most polynomial in n. Pseudochaotic dynamics (peach color) exhibits the scaling which falls between these two. c The 2k-dimensional subspace is mapped to the entire space by isometries {Oa}. \({{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) is the space spanned by an ensemble of unitary operators {u} in the subspace, which could be non-chaotic. Through the action of Oa, \({{{{\mathcal{V}}}}}_{{{{\rm{sub}}}}}\) is mapped to \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) within the entire Hilbert space, preserving its dimension. Remarkably, even if the subspace dimension is negligibly smaller than the entire space dimension, its ensemble average over random isometries cannot be distinguished from chaotic dynamics by any poly-time quantum algorithms with access to polynomially many copies of evolved states.

Explicit construction

We introduce a systematic construction for pseudochaotic dynamics, which we term ‘random subsystem-embedded dynamics (RSED)’. The RSED consists of two components: a random subset isometry Oa and an embedded unitary operator u in the subsystem. The random subset isometry is defined as

where k ≤ n represents a subsystem of size k within the total system of size n, and p and f are random permutation and function, respectively. Our key observation is that \(k=\omega (\log n)\) is necessary for RSED to be pseudochaotic. Below we always set \(k=\omega (\log n)\). The term a ∈ {0, 1}n−k serves as the seed for these random mappings. This isometry embeds a unitary operator u, acting on the 2k-dimensional subsystem Hilbert space, into the 2n-dimensional Hilbert space of the entire system.

The full unitary evolution of RSED is given by

Figure 2b illustrates how dynamics in the subsystem is embedded into the entire system by an isometry Oa. The effect of the conjugation by {Oa} is equivalent to applying random permutation with random sign factors on the unitary operator in the entire space, u ⊗ I⊗(n−k). The time evolution operator with an evolution time t is

because of \({O}_{a}^{{{\dagger}} }{O}_{{a}^{{\prime} }}={\delta }_{a,{a}^{{\prime} }}\). In principle, arbitrary u is allowed. However, for a RSED to be pseudochaotic, it is sufficient for ut to have negligibly small elements for all time t ≥ t* for some positive constant t* as we explain below. More details on the RSED can be found in Supplementary Note 1.

Here we compute the OTOCs of OVW of (a, b) the Pauli SYK model and (c, d) H⊗kP with V = Zi and W = Zj with i ≠ j. a, c OVW of independent realizations. b, d Averaged OVW over random subset isometries and random realizations of the embedded u’s for various system sizes n. \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{p,f}{O}_{VW}\) in the caption denotes that the averaged OTOCs are computed using the closed formula in Method Eq. (12). For all cases, the subspace dimension is 2k with k = 10.

Interestingly, the level statistics of a pseudochaotic RSED differ drastically from those of conventional chaotic systems due to exponential degeneracies in its energy spectrum. Thus, even when a chaotic u is chosen, the level statistics of the corresponding RSED deviate from the standard Wigner-Dyson distribution51,52. In contrast, the spectral form factor of the RSED closely follows the behavior of that of u. Further details can be found in Supplementary Note 10.

Negligible OTOC

We first show that if elements of u have negligible magnitudes in the computational basis, i.e., the diagonalizing basis of Oa, then an individual realization of the RSED has negligible OTOCs and thus cannot be distinguished from chaotic unitary evolutions via OTOC. Here, negligible, or negl(n) appeared below, means the magnitude of a quantity decays faster than inverse of any polynomial function of n.

Theorem 1

OTOCs with local operators are negligible with probabilities higher than 1 − negl(n) in the system size n for an individual realization of the RSED with an embedded unitary operator u of the dimension 2k with \(k=\omega (\log n)\) (sampled from an ensemble) if the maximum (averaged) magnitude of elements of the embedded operator u is O(2−k/2).

Proof

Details are in Theorem 5 of Supplementary Note 3.

Such u naturally includes general chaotic dynamics following the random matrix theory, whose time evolution operators have the matrix elements of order O(2−k/2) for all time t ≥ t* for some constant t* > 0. In literature, such t* is called the intermediate time regime for chaotic dynamics53.

Notably, non-chaotic u can also have such property. An example is the product of Hadamard gates H⊗k with a random sign operator P in the subsystem, namely u = H⊗kP. The matrix elements of ut are on average order of 2−k/2 for t ≥ t* ≈ 1 (See Supplementary Note 7). Thus, this RSED is expected to demonstrate negligible OTOCs for all t ≳ 1, according to Theorem 1. Indeed, we numerically confirm that individual realizations of the RSED exhibit negligibly small OVW as shown in Fig. 2a, b. By passing, we mention that without the sign randomization P, u = H⊗k alone cannot produce pseudochaotic dynamics and OTOCs are not suppressed as the matrix elements of ut do not persistently scale with 2−k/2 (Supplementary Note 8).

We also compute OTOCs of the RSED by embedding the Pauli SYK model54, which is chaotic. As expected, this RSED demonstrates vanishing OTOCs, see Fig. 2c, d. Importantly, the late-time saturated values of OVW for u = H⊗kP scale as negl(n), as clearly demonstrated in the log-log plot of OVW versus system size n (Fig. 3). Minor numerical details and additional data are available in Supplementary Note 7. By passing, we note that OTOCs at finite temperatures and those with non-local Pauli operators are also negligible (Supplementary Notes 4, 8).

In evaluating OTOCs Eq. (1), we chose V = Zi, W = Zj, i ≠ j, and \(k={(\log n)}^{2}\). The OTOCs are averaged over random isometries and random phase gates P. The time t at which the OTOC values are extracted is fixed to t = 4 for all system sizes n. Since the OTOCs approaches to the infinite-time values for t ≳ 1, any such value of t is sufficient to capture the late-time behavior. If the OTOCs scaled as an inverse polynomial in n, the data would appear as straight lines in the log-log plot. However, the observed curve (red solid line) is concave, indicating that the OTOCs decay faster than any inverse polynomial. The linear function fit with the numerical data (blue straight line) has the slope ≈ −2.85 in this log-log plot.

The exponential decay of OTOCs in evolution time and their associated exponents, known as Lyapunov exponents, are also well-established signatures of quantum chaotic systems13,53. However, for systems governed by nonlocal Hamiltonians, such as the pseudochaotic dynamics considered here, a well-defined Lyapunov exponent does not exist. Further details on this issue are provided in Supplementary Note 6.

Pseudorandom State Generator

We first demonstrate that RSED with chaotic u is a pseudorandom state generator. More precisely, we show that if an ensemble of u generates a pseudorandom state ensemble in the subsystem, then the corresponding ensemble of U in Eq. (3) produces a pseudorandom state ensemble in the entire Hilbert space.

Theorem 2

RSEDs with an ensemble of embedded unitary operators that generate a pseudorandom state ensemble in the subspace with a negligible error generate a pseudorandom state ensemble in the entire space.

Proof

This is proven in Theorem 6 of Supplementary Note 9.

Such an ensemble of chaotic u can be constructed by sampling time evolution operators from a single, fixed chaotic u, provided that the time interval exceeds its relaxation time. This immediately implies that the corresponding U produces a pseudorandom state ensemble by sampling states in time. This is nicely parallel to the generation of the Haar random state ensemble by sampling states in the time trajectory of a state under chaotic dynamics at a sufficiently long time interval50.

Next, we consider an ensemble of u with negligibly small elements with the unbiased mean magnitude of 2−k/2, e.g., ut for t ≥ t* ≈ 1 with u = H⊗kP, and show that the corresponding ensemble of RSED can also produce a pseudorandom state ensemble. Hence, such RSED serves as another example of pseudochaotic dynamics. We highlight that the subspace dynamics u does not need to be ergodic, as illustrated in Fig. 1c.

Theorem 3

Let \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{k}\) be an ensemble of unitary operators in a k-qubit subsystem with dimension K = 2k. Let us assume that for all \(u\in {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{k}\), there exists ϵ > 0 such that

for all b and \({b}^{{\prime} }\). In addition, let us assume that \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{u \sim {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{k}}\left[{\left\vert {u}_{b,{b}^{{\prime} }}\right\vert }^{2}\right]={K}^{-1}\) holds for all b and \({b}^{{\prime} }\). Then, an ensemble of RSEDs with \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{k}\) generates an ensemble of pseudorandom states.

Proof

Let us consider an initial computational state \(\left\vert p(ba)\right\rangle\). This evolves under the subsystem embedded dynamics U with an embedded dynamics u as

Let ρ be Hybrid 3 of ref. 38, and σ be the ensemble average of \(U\left\vert p(ba)\right\rangle\) over \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{k}\), random permutations p, and random functions f. Then, the triangular inequality gives

with \({\rho }_{{{{\rm{Haar}}}}}=\int\,d{\psi }_{{{{\rm{Haar}}}}}\left\vert \psi \right\rangle {\left\langle \psi \right\vert }^{\otimes t}\). The first term on the right-hand side is negligible due to Lemma 3 of ref. 38. In addition, the second term TD(ρ, σ) is is negligible due to the assumption of \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{u \sim {{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{k}}\left[{\left\vert {u}_{b,{b}^{{\prime} }}\right\vert }^{2}\right]={K}^{-1}\) as shown in the proof of Theorem 7 of Supplementary Note 9.

While unitary operators in a general random ensemble have unbiased elements, it is not a necessary condition for a pseudochaotic dynamics. Indeed, even when elements are biased, RSED is pseudochaotic if u generates maximal relative entropy of coherence55 in computational basis with a negligible deviation. This sufficient condition is consistent with the necessary condition of \(\omega (\log n)\) coherence introduced in ref. 40. More details can be found from Theorem 8 of Supplementary Note 11.

Quantum circuit and its resources

We present an explicit quantum circuit for pseudochaotic RSED and the resources required to implement it.

The circuit consists of three steps, as shown in Fig. 4. The first and last steps apply quantum secure pseudorandom function and permutation in the entire system with \({{{\rm{polylog}}}}(n)\) depth circuits under the assumption of the sub-exponential hardness of the Learning with Errors (LWE) problem56,57,58,59. In the middle, only the subsystem evolves under dynamics generating nearly maximal coherence in the computational basis. The generation of maximal coherence can be achieved by products of Hadamard gates, so the time complexity for the middle step is Ω(1).

Coherent evolution in (a) refers to unitary dynamics generating nearly maximal coherence in the subsystem. The sum of subsystem dynamics conjugated by random isometries in (b) can be implemented by pseudorandom function and permutation in the entire space in (a). This identity can be derived by inserting a resolution identity operator in the computational basis at the straight lines of the middle step in (a). See Supplementary Note 1 for details.

The pseudochaotic RSED can be turned into a truly chaotic dynamics by increasing the number of entangling and non-Clifford gates in random permutation and function (the first and last steps in Fig. 4a), coherent gates in the subsystem dynamics, and the size of the subsystem (the middle step in Fig. 4a), which brings the ensemble of resulting states closer to Haar random states. More explicitly, the exponential decay of OTOC in system size, which is expected for general quantum chaotic systems, can be achieved once pseudorandom isometries are replaced by truly random unitaries by using exponentially many non-Clifford and entangling gates and embedding Ω(n) Hadamard gates60. On the other hand, using only one of these resourceful gates cannot decrease OTOCs and the trace distance with Haar random states. Thus, such a process cannot turn the RSED into chaotic dynamics.

Theorem 4

Each of entanglement, magic, and coherence of a pseudochaotic RSED can be increased independently without changing other resources and making the RSED chaotic.

Proof

Entanglement, magic, and coherence can be controlled independently by attaching random Clifford gates, random T-gates, and random Hadamard gates, respectively, to the end of the circuit in Fig. 4. Details can be found in Supplementary Note 12.

Discussion

In this work, we propose a new concept called pseudochaotic dynamics, which is a non-chaotic dynamics that cannot be distinguished from the maximally chaotic dynamics using polynomial resources. We further introduce the RSED as a systematic way to construct pseudochaotic dynamics and pseudorandom states. This dynamics can be implemented by pseudorandom permutation and function, which can be implemented by polylogarithmic depth circuits56,57,61,62, for example in Rydberg atoms or ion-trapped qubits63,64. Using this, we expect that pseudochaotic dynamics can be realized in near-term devices with a few dozens of qubits (Supplementary Note 13). Although it is not the primary focus of this work, an RSED can generate an approximate state t-design with the shallowest circuit depth among currently known protocols26,27,28,29,65,66,67, which will be detailed separately in ref. 60. These together make our RSED highly efficient for tasks such as classical shadow tomography33, benchmarking quantum circuits68, and even studying black holes69,70,71,72.

Let us highlight the distinctions between our work and previous studies38,39,73,74. First, our approach clearly contrasts with prior investigations of pseudorandom quantum states38,39, which primarily focused on quantum resource requirements. Instead, we emphasize the dynamical properties such as OTOCs of quantum circuits that generate pseudorandom states. Second, our construction of a pseudorandom state generator is distinct from prior work based on random gates74, which exhibit suppression of OTOCs on average by the operator mean field theory73. In contrast, our pseudochaotic RSED exhibit suppression of OTOCs for each individual realization. Additionally, we assume the hardness of the LWE problem which is believed to be secure against quantum attacks38,58,59, while ref. 74 relies on the assumption that security against a classical adaptive chosen-plaintext and chosen-ciphertext attack implies quantum security. Third, our work introduces a Hamiltonian-based RSED for generating pseudorandom states, opening the door to their realization in analog quantum simulators. This stands in sharp contrast to previous works38,39,74, which rely on quantum circuits implemented on digital quantum computers. Lastly, our pseudochaotic RSED achieves the known lower bound on circuit depth for generating pseudorandom states38,74.

We finish by discussing interesting future research directions. First, it will be interesting to clarify the relation between the two properties, having negligible OTOCs and generating pseudorandom states, of the pseudochaotic dynamics are related. Second, it would be also interesting to study dynamical properties of RSEDs with various embedded Hamiltonians including integrable ones, which could potentially lead to the discovery of a new class of quantum many-body dynamics. Another interesting question is to investigate whether typical pseudochaotic dynamics can be used to construct pseudorandom unitaries and whether these dynamics are difficult to simulate with classical algorithms. If both are true, the quantum advantage in random circuit sampling, which relies on typical circuits being close to Haar-random unitaries35,45,75, could be demonstrated with significantly lower circuit depth by replacing them with pseudochaotic dynamics. Answering these questions could, therefore, provide a new perspective on the connection between quantum computational advantage and quantum chaos26,76. Finally, we note a recent related work that introduces a similar concept of pseudochaos77. While our definition of pseudochaotic dynamics only requires negligible OTOCs and the generation of a pseudorandom state ensemble, ref. 77 imposes an additional constraint on the definition of pseudochaos to avoid producing states with high entanglement and magic. Notably, our construction of RSED encompasses the pseudo-Gaussian unitary ensemble introduced in ref. 77, by embedding an ensemble of unitaries whose eigenvalues follow Wigner’s semicircle distribution without level repulsions. Clarifying the precise relationship between the two definitions of pseudochaos remains an important direction for future work.

Methods

Out-of-time ordered correlators

A Poisson-bracket out-of-time ordered correlator quantifies how a local operator W spreads under a unitary evolution U by measuring the magnitude of parts of UWU† commuting with another local operator V. Formally, it is defined as

If U does not spread W much, then V at almost everywhere commutes with UWU†. Thus, CVW(U) is vanishing. On the other hand, if U is chaotic so makes UWU† be a sum of arbitrary non-local Pauli strings, then CVW saturates to unity. When local operators satisfy V2 = W2 = I like as Pauli operators, then it becomes

Here, OVW(U) is the OTOC used in the main text. Any chaotic U makes OVW(U) vanishingly small.

Calculation of OTOCs

Estimation of OVW(U) of a chaotic system is generally challenging as it requires to simulate the system. However, for the RSED, it is possible to calculate OVW(U) both analytically and numerically. Here, we compute OVW(U) with V = Zi and W = Zj with i ≠ j.

Let p and f be a random permutation and function, respectively. Then, OVW(U) is given by

Here, {bi} and {ai} are summed over {0, 1}k and {0, 1}n−k, respectively. Since V = Zi and W = Zj, this can be simplified as

Numerically, this can be approximately computed by the importance sampling on a ∈ {0, 1}n−k. The ensemble average of OVW(U) over f is given by

since that of \({(-1)}^{{[p({b}_{1}a)]}_{i}+{[p({b}_{3}a)]}_{i}}\) is \({\delta }_{{b}_{1},{b}_{3}}\). Here, A. *B is the element-wise multiplication of A and B. More details are deferred to Supplementary Notes 2 and 3.

Pseudorandom state ensemble

A pseudorandom state ensemble \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) is an ensemble of states that cannot be distinguished by any polynomial copies of states and any poly-time quantum algorithms. For any t = poly(n), there is no poly-time quantum algorithm \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) that satisfies

with \(\rho={{\mathbb{E}}}_{\phi \sim {{{\mathcal{E}}}}}\left[\left\vert \phi \right\rangle {\left\langle \phi \right\vert }^{\otimes t}\right]\) and \(\sigma={{\mathbb{E}}}_{\psi \sim {{{\rm{Haar}}}}}\left[\left\vert \psi \right\rangle {\left\langle \psi \right\vert }^{\otimes t}\right]\).

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data have been deposited in the Mendeley Data (10.17632/h7gsjtv27p.1)(ref. 78).

References

Saffman, M., Walker, T. G. & Mølmer, K. Quantum information with Rydberg atoms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2313 (2010).

Wendin, G. Quantum information processing with superconducting circuits: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 106001 (2017).

Pezzè, L., Smerzi, A., Oberthaler, M. K., Schmied, R. & Treutlein, P. Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensembles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018).

Monroe, C. et al. Programmable quantum simulations of spin systems with trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025001 (2021).

Eisert, J., Friesdorf, M. & Gogolin, C. Quantum many-body systems out of equilibrium. Nat. Phys. 11, 124–130 (2015).

Nandkishore, R. & Huse, D. A. Many-body localization and thermalization in quantum statistical mechanics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 15–38 (2015).

D’Alessio, L., Kafri, Y., Polkovnikov, A. & Rigol, M. From quantum chaos and eigenstate thermalization to statistical mechanics and thermodynamics. Adv. Phys. 65, 239–362 (2016).

Dziarmaga, J. Dynamics of a quantum phase transition and relaxation to a steady state. Adv. Phys. 59, 1063–1189 (2010).

Heyl, M. Dynamical quantum phase transitions: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 81, 054001 (2018).

Abanin, D. A., Altman, E., Bloch, I. & Serbyn, M. Colloquium: Many-body localization, thermalization, and entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 021001 (2019).

Lunin, O. & Mathur, S. D. Ads/cft duality and the black hole information paradox. Nucl. Phys. B 623, 342–394 (2002).

Maldacena, J. & Stanford, D. Remarks on the sachdev-ye-kitaev model. Phys. Rev. D. 94, 106002 (2016).

Maldacena, J., Shenker, S. H. & Stanford, D. A bound on chaos, J. High Energy Phys. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1007/jhep08(2016)106 (2016).

Sachdev, S. & Ye, J. Gapless spin-fluid ground state in a random quantum Heisenberg magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 3339 (1993).

Kitaev, A. Talks at KITP, University of California, Santa Barbara, Entanglement in Strongly-Correlated Quantum Matter https://online.kitp.ucsb.edu/online/entangled15 (2015).

Fisher, M. P., Khemani, V., Nahum, A. & Vijay, S. Random quantum circuits. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 14, 335 (2023).

Lieb, E. H. & Robinson, D. W. The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems. Commun. Math. Phys. 28, 251 (1972).

Shenker, S. H. & Stanford, D. Black holes and the butterfly effect. J. High Energy Phys. 2014, https://doi.org/10.1007/jhep03(2014)067 (2014).

Roberts, D. A. & Yoshida, B. Chaos and complexity by design. J. High. Energy Phys. 2017, 121 (2017).

Lewis-Swan, R. J., Safavi-Naini, A., Kaufman, A. M. & Rey, A. M. Dynamics of quantum information. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 627–634 (2019).

Joshi, L. K. et al. Probing many-body quantum chaos with quantum simulators. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011018 (2022).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing and the entanglement frontier https://arxiv.org/abs/1203.5813 (2012).

Boixo, S. et al. Characterizing quantum supremacy in near-term devices. Nat. Phys. 14, 595–600 (2018).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505 (2019).

Aaronson, S. & Gunn, S. On the classical hardness of spoofing linear cross-entropy benchmarking https://doi.org/10.4086/toc.2020.v016a011 (2020).

Brandão, F. G. S. L., Harrow, A. W. & Horodecki, M. Local random quantum circuits are approximate polynomial-designs. Commun. Math. Phys. 346, 397–434 (2016).

Nakata, Y., Hirche, C., Koashi, M. & Winter, A. Efficient quantum pseudorandomness with nearly time-independent hamiltonian dynamics. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021006 (2017).

Ho, W. W. & Choi, S. Exact emergent quantum state designs from quantum chaotic dynamics, Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.128.060601 (2022).

Cotler, J. S. et al. Emergent quantum state designs from individual many-body wave functions. PRX Quantum 4, 010311 (2023).

Ananth, P., Qian, L. & Yuen, H. Cryptography from pseudorandom quantum states, in Annual International Cryptology Conference https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15802-5_8 (Springer, 2022) pp. 208–236.

Kretschmer, W., Qian, L., Sinha, M. & Tal, A. Quantum cryptography in algorithmica, in Proceedings of the 55th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.00879 (2023) pp. 1589–1602.

Knill, E. et al. Randomized benchmarking of quantum gates, Phys. Rev. A 77, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreva.77.012307 (2008).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Predicting many properties of a quantum system from very few measurements. Nat. Phys. 16, 1050–1057 (2020).

Huang, H.-Y. Learning quantum states from their classical shadows. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 81 (2022).

Bouland, A., Fefferman, B., Nirkhe, C. & Vazirani, U. On the complexity and verification of quantum random circuit sampling. Nat. Phys. 15, 159 (2019).

Knill, E. Approximation by quantum circuits https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9508006 (1995).

Ji, Z., Liu, Y.-K. & Song, F. Pseudorandom quantum states, in Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2018, edited by Shacham, H. and Boldyreva, A. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96878-0_5 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018).

Aaronson, S. et al. Quantum pseudoentanglement, https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.00747 (2023).

Gu, A. et al. Pseudomagic quantum states, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.132.210602 (2024).

Haug, T., Bharti, K. & Koh, D. E. Pseudorandom unitaries are neither real nor sparse nor noise-robust, https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.11677 (2023).

Kretschmer, W. Quantum Pseudorandomness and Classical Complexity, in 16th Conference on the Theory of Quantum Computation, Communication and Cryptography (TQC 2021), Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), Vol. 197, edited by Hsieh, M.-H. https://doi.org/10.4230/LIPIcs.TQC.2021.2 (Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, Dagstuhl, Germany, 2021) pp. 2:1–2:20.

Morimae, T. & Yamakawa, T. One-wayness in quantum cryptography, Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2022/1336 https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/1336 (2022).

Bostanci, J. et al. Unitary complexity and the uhlmann transformation problem, arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.13073 https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.13073 (2023).

Elben, A. et al. The randomized measurement toolbox. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 9 (2023).

Movassagh, R. The hardness of random quantum circuits. Nat. Phys. 19, 1719 (2023).

Hashimoto, K., Murata, K. & Yoshii, R. Out-of-time-order correlators in quantum mechanics. J. High. Energy Phys. 2017, 1 (2017).

Naor, M. & Reingold, O. Number-theoretic constructions of efficient pseudo-random functions. J. ACM 51, 231–262 (2004).

Swingle, B., Bentsen, G., Schleier-Smith, M. & Hayden, P. Measuring the scrambling of quantum information. Phys. Rev. A 94, 040302 (2016).

Yao, N. Y. et al. Interferometric approach to probing fast scrambling https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.01801 (2016).

Schiulaz, M., Torres-Herrera, E. J. & Santos, L. F. Thouless and relaxation time scales in many-body quantum systems, Phys. Rev. B 99, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.99.174313 (2019).

Cotler, J., Hunter-Jones, N., Liu, J. & Yoshida, B. Chaos, complexity, and random matrices, J. High Energy Phys. 2017, https://doi.org/10.1007/jhep11(2017)048 (2017).

Livan, G., Novaes, M. & Vivo, P. Introduction to random matrices theory and practice. Monogr. Award 63, 914 (2018).

García-Mata, I., Jalabert, R. A. & Wisniacki, D. A. Out-of-time-order correlators and quantum chaos. Scholarpedia 18, 55237 (2023).

Hanada, M., Jevicki, A., Liu, X., Rinaldi, E. & Tezuka, M. A model of randomly-coupled pauli spins, J. High Energy Phys. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/jhep05(2024)280 (2024).

Baumgratz, T., Cramer, M. & Plenio, M. B. Quantifying coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 140401 (2014).

Banerjee, A., Peikert, C. & Rosen, A. Pseudorandom functions and lattices, in https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29011-4_42Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2012, edited by Pointcheval, D. and Johansson, T. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012) pp. 719–737.

Hosoyamada, A. & Iwata, T. 4-round luby-rackoff construction is a qprp, in International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:147692931 (2019).

Arunachalam, S., Grilo, A. B. & Sundaram, A. Quantum hardness of learning shallow classical circuits. SIAM J. Comput. 50, 972 (2021).

Zhao, H. et al. Learning quantum states and unitaries of bounded gate complexity. PRX Quantum 5, 040306 (2024).

Lee, W., Kwon, H. & Cho, G. Y. Fast pseudothermalization https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.03974 (2024).

Naor, M. & Reingold, O. Synthesizers and their application to the parallel construction of pseudo-random functions. J. Computer Syst. Sci. 58, 336 (1999).

Zhandry, M. A note on the quantum collision and set equality problems. Quantum Info Comput. 15, 557–567 (2015).

Evered, S. J. et al. High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 622, 268 (2023).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58 (2024).

Feng, X. & Ippoliti, M. Dynamics of pseudoentanglement. J. High Energ. Phys. 2025, 128 (2025).

Haah, J., Liu, Y. & Tan, X. Efficient approximate unitary designs from random Pauli rotations https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.05239 (2024).

Schuster, T., Haferkamp, J. & Huang, H.-Y. Random unitaries in extremely low depth https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.07754 (2024)

Helsen, J., Roth, I., Onorati, E., Werner, A. & Eisert, J. General framework for randomized benchmarking. PRX Quantum 3, 020357 (2022).

Yoshida, B. & Kitaev, A. Efficient decoding for the Hayden-Preskill protocol https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.03363 (2017).

Yoshida, B. & Yao, N. Y. Disentangling scrambling and decoherence via quantum teleportation. Phys. Rev. X 9, 011006 (2019).

Bouland, A., Fefferman, B. & Vazirani, U. Computational Pseudorandomness, the Wormhole Growth Paradox, and Constraints on the AdS/CFT Duality, in 11th Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2020), Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics (LIPIcs), Vol. 151, edited by Vidick, T. https://doi.org/10.4230/LIPIcs.ITCS.2020.63 (Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, Dagstuhl, Germany, 2020) pp. 63:1–63:2.

Piroli, L., Sünderhauf, C. & Qi, X.-L. A random unitary circuit model for black hole evaporation, J. High Energy Phys. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1007/jhep04(2020)063 (2020)

Chamon, C., Mucciolo, E. R. & Ruckenstein, A. E. Quantum statistical mechanics of encryption: Reaching the speed limit of classical block ciphers. Ann. Phys. 446, 169086 (2022).

Chamon, C., Mucciolo, E. R., Ruckenstein, A. E. & Yang, Z.-C. Fast pseudorandom quantum state generators via inflationary quantum gates. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 37 (2024).

Bremner, M. J., Montanaro, A. & Shepherd, D. J. Average-case complexity versus approximate simulation of commuting quantum computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 080501 (2016).

Harrow, A. W. & Mehraban, S. Approximate unitary t-designs by short random quantum circuits using Nearest-Neighbor and Long-Range gates. Commun. Math. Phys. 401, 1531 (2023).

Gu, A., Quek, Y., Yelin, S., Eisert, J. & Leone, L. Simulating quantum chaos without chaos https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.18196 (2024).

Lee, W., Kwon, H. & Cho, G. Y. Pseudochaotic many-body dynamics as a pseudorandom state generator, Mendeley Data, V1, https://doi.org/10.17632/h7gsjtv27p.1 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Changhun Oh for helpful discussions. W.L. and G.Y.C. are supported by Samsung Science and Technology Foundation under Project Number SSTF-BA2002-05 and SSTF-BA2401-03, the NRF of Korea (Grants No. RS-2023-00208291, No. 2023M3K5A1094810, No. RS-2023-NR119931, No. RS-2024-00410027, No. RS-2024-00444725) funded by the Korean Government (MSIT), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under Award No. FA2386-22-1-4061, No. FA23862514026., and Institute of Basic Science under project code IBS-R014-D1. H.K. is supported by the KIAS Individual Grant No. CG085302 at Korea Institute for Advanced Study and National Research Foundation of Korea (Grants No. RS-2023-NR119931, No. RS-2024-00413957 and No. RS-2024-00438415) funded by the Korean Government (MSIT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L., H.K., and G.Y.C. conceived and designed the project. W.L. performed theoretical analyses and calculations under the supervision of H.K. and G.Y.C. All authors contributed to discussions and to writing and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, W., Kwon, H. & Cho, G.Y. Pseudochaotic many-body dynamics as a pseudorandom state generator. Nat Commun 16, 6800 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62081-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62081-6