Abstract

The high cost and complexity of fabrication limit the large-scale application of flexible inorganic thermoelectric materials. Currently, Bi2Te3-based materials are the only commercially viable option, but the inclusion of Te significantly increases production costs. This study presents a simple and cost-effective method for fabricating flexible Ag2Se films, employing a combination of solvothermal synthesis, screen printing, and spark plasma sintering. The incorporation of a small amount of Te improves film density and facilitates Te diffusion doping, leading to Ag2Se films with a high power factor of 25.7 μW cm−1 K−2 and a figure of merit (ZT) of 1.06 at 303 K. These films exhibit excellent flexibility, retaining 96% of their performance after 1000 bending cycles at a 5 mm bending radius. Additionally, we design a flexible thermoelectric device featuring a triangular p-n junction structure based on these films. This device achieves a normalized power density of 4.8 μW cm−2 K−2 at a temperature difference of 20 K and a maximum cooling of 29.8 K with an input current of 92.4 mA. These findings highlight the potential of this fabrication method for developing thermoelectric materials and devices for energy harvesting and cooling applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thermoelectric technology, especially flexible thermoelectric devices (F-TEDs), is important for converting heat into electricity for power generation and cooling1,2. These devices are well-suited for powering and controlling the temperature of small electronics like smartphones and smartwatches3,4. To achieve sufficient power and cooling performance, F-TEDs require thermoelectric materials with a high power factor (S2σ) and figure of merit (ZT) at near-room temperatures4,5. The ZT value is given by ZT = S2σT/κ, where S is the Seebeck coefficient, σ is electrical conductivity, T is absolute temperature, and κ is thermal conductivity2. The κ includes both lattice thermal conductivity (κl) and electronic thermal conductivity (κe)2. However, most inorganic materials with good thermoelectric properties lack flexibility, while organic materials, though flexible, usually have poor thermoelectric performance. Therefore, researchers are working to improve the flexibility of inorganic thermoelectric materials, as these materials are more advanced in development6,7.

Among thermoelectric materials, Bi2Te3 has the best performance near room temperature and is the only material used in commercial applications8. However, its reliance on tellurium (Te) makes it expensive and limits large-scale use9. Ag2Se is a narrow band-gap n-type semiconductor that exists as an orthorhombic phase (β-Ag2Se) at room temperature and transforms into a cubic phase (α-Ag2Se) at high temperatures (≈130 °C)10. β-Ag2Se has thermoelectric properties comparable to Bi2Te3 due to its high carrier mobility (μ) and low κl, making it a promising alternative2,3. Recent studies on bulk Ag2Se have demonstrated that preferentially fabricating Ag2Se crystals through one-step sintering can enhance the ZT to 0.95 at 300 K2. Additionally, using a solution-based method and optimizing the sintering temperature can increase ZT to 1.1 at 373 K11. Furthermore, doping Ag2Se with 0.2 at.% Zn has been shown to further improve ZT to 1.3 at 393 K12. More recently, 3D-printed Ag2Se pellets achieved a ZT of 1.3 at room temperature, further highlighting its potential13. However, challenges such as high porosity (≈50%), excessive thickness (≈0.8 mm), and limited flexibility hinder its use in wearable and microelectronic devices. Moreover, bulk Ag2Se does not fully utilize its crystal structure, which provides greater ductility than Bi2Te3, making it a strong candidate for flexible thermoelectric materials2.

Several methods have been developed to fabricate Ag2Se films, including magnetron sputtering14, vacuum filtration3, co-evaporation5, physical vapor deposition (PVD)15, and screen printing16. However, achieving a ZT exceeding 1 remains challenging across these techniques. Among these, screen printing is the most straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient. Despite its advantages, most screen-printed Ag2Se films show poor thermoelectric performance17,18. This is mainly due to their high porosity, which reduces σ and lowers the S2σ17,18,19. Addressing this issue while maintaining flexibility remains a key challenge in optimizing screen-printed Ag2Se films. Several strategies have been explored to improve the thermoelectric performance of Ag2Se films, including film orientation control20, doping5,21, sandwich engineering22, and the addition of secondary phases5. Some studies suggest that enhancing the (013) orientation can increase μ and σ, leading to a higher S2σ5. However, a significant increase in σ can also raise κe, which may reduce the ZT5. Additionally, since Ag2Se lacks a layered crystal structure, controlling its orientation is challenging14. Traditional doping methods also have limitations. Ag2Se has a high intrinsic carrier concentration (n) due to the low formation energy of selenium (Se) vacancies5. Reducing n could improve the S, but cation doping usually increases n, which lowers S, as Ag exists in the +1 valence state5. Therefore, anion doping and the introduction of secondary phases are considered more effective strategies3,5. However, anion doping, such as sulphur doping, can alter the primary phase and reduce ZT in some cases23. The addition of secondary phases is also challenging, as selecting a suitable phase to enhance Ag2Se’s properties is not straightforward14. Research on these approaches, especially for flexible films, remains limited, highlighting opportunities for further study.

Result and discussion

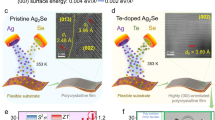

Most inorganic films produced by screen printing have low density due to high porosity17,18. To address this, reducing particle size in the ink or adding fillers can improve film densification17,19,24. Our previous study18 showed that Te acts as a nanobinder, enhancing the thermoelectric properties of screen-printed Bi2Te3 films. We also fabricated Ag2Se films in that study, confirming the effectiveness of Te in screen-printed films. However, at the time, research on Ag2Se was still in its early stages, and the role of Te in Ag2Se films remained unclear. Further investigation is needed to determine the optimal Te content and its impact on Ag2Se films. In this work, we synthesized Ag2Se microparticles and Te nanorods (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) using solvothermal methods, followed by screen printing and spark plasma sintering (SPS) to produce a dense, flexible Ag2Se/Te composite film. Unlike our previous findings, we observed that Te in Ag2Se films undergoes diffusion doping during annealing, optimizing the bandgap. The unit-cell structures of pure and Te-doped Ag2Se are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3, and Fig. 1a illustrates the mechanism of Te incorporation. Te acts as a filler, increasing film density and enhancing μ and σ. Additionally, the Te phase induces an energy filtering effect, optimizing both n and the S. This diffusion doping increases the Ag2Se bandgap from 0.07 to 0.127 eV, further improving n and S. As a result, the Ag2Se/Te film achieves an exceptional S2σ of 25.7 μW cm−1 K−2 at 303 K, the highest reported for screen-printed films (Fig. 1b)16,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. The soldering effect of Te nanorods also enhances film flexibility, as shown in the inset. To evaluate practical applications, we designed a flexible thermoelectric device (F-TED) with a triangular p-n junction, consisting of 10 pairs of p-type Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3 legs and n-type Ag2Se/Te legs, as shown in Fig. 1c. The device achieves a power density (ω) of 1.9 mW cm−2 at a temperature difference (ΔT) of 20 K, corresponding to a normalized power density (ωn) of 4.8 μW cm−2 K−2, comparable to devices made using other fabrication methods (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 1d)5,9,16,25,26,27,28,35,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85. The Peltier effect was also evaluated, showing a maximum cooling performance (ΔTmax) of 29.8 K under a 92.4 mA current without external heat sinks. These results highlight the potential of the Ag2Se/Te film for power generation and thermal management applications.

a Schematic illustration of the mechanism and structure of screen-printed Ag2Se/Te films. The right side shows the calculated bandgap of pure Ag2Se, while the left side shows the bandgap of Te-doped Ag2Se. b Comparison of power factor (S2σ) as a function of the Seebeck coefficient (S) between the Ag2Se film developed in this work and previously reported near-room-temperature inorganic thin films fabricated by screen printing16,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. The inset shows the bending flexibility of the Ag2Se film. c Schematic of the thermoelectric device structure designed in this study. d Comparison of normalized power density (ωn) among thermoelectric devices produced using different fabrication methods5,9,16,25,26,27,28,35,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85. Inkjet printing includes spin coating, machine printing, blade printing, and screen printing.

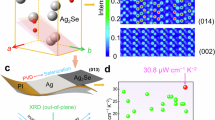

To determine the optimal amount of Te for enhancing the thermoelectric performance of Ag2Se films, we synthesized a series of Ag2Se + xTe compositions, where x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.%. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to examine the phase structure of the resulting films. Figure 2a shows the XRD patterns in the 2θ range from 20° to 55°. All major diffraction peaks align with the orthorhombic Ag2Se phase (PDF #04-002-0445) and hexagonal Te phase (PDF #04-027-7719). As the Te content increases, the intensities of Te-related diffraction peaks strengthen, particularly displaying a (100) preferred orientation, likely due to the pressure applied during SPS. For a more detailed analysis, Rietveld refinement of the XRD data was performed for films with 0, 5, and 10 wt.% Te, as shown in Fig. 2b. Additional refinements for films with 2.5 and 7.5 wt.% Te are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4, with detailed results provided in Supplementary Table 2. The refinement results reveal that as the Te content increases, the lattice parameters (a, b, c) of Ag2Se expand, suggesting that Te2− ions (97 pm) replace Se2− ions (50 pm), as depicted in Fig. 2c. Figure 2d shows the full X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of the Ag2Se film with 5 wt.% Te, confirming the presence of Ag, Se, and Te. Figure 2e provides high-resolution scans of Te 3d5/2, revealing three distinct states of Te in the Ag2Se film: Te0 (573 eV), Te2− (576.1 eV), and Te4+ (572.6 eV). These findings support both the XRD and Rietveld refinement results, further confirming the diffusion of Te into the Ag2Se structure.

a X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of Ag2Se thin films with different Te contents (x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.%). b Rietveld quantitative phase analysis of Ag2Se thin films with x = 0, 5, and 10 wt.% Te. c Corresponding lattice parameters of Ag2Se with x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.% Te. d Full X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey of Ag2Se film with x = 5 wt.%. e Detailed XPS survey for Te 3 d of Ag2Se film with x = 5 wt.% Te. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of Ag2Se films with f x = 0 and g x = 5 wt.% Te from both top and cross-sectional views. h Secondary electron (SE) SEM images of Ag2Se film with x = 5 wt.% Te from 565 to 585 eV. i Corresponding backscattered electron (BSE) SEM images and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps for Ag, Se, and Te.

The microstructure and composition of the as-fabricated Ag2Se/Te films were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Figure 2f, g presents both top and cross-sectional SEM images of Ag2Se films with 0 and 5 wt.% Te. The top-view images reveal that adding Te significantly improves the densification of the Ag2Se film. As the Te content increases, the film thickness remains approximately constant at around 15 μm, as shown in the cross-sectional views. Additional SEM images of Ag2Se films with varying compositions are provided in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6. The film thickness and uniformity show only slight variation (12–16 μm) with different Te content since all films were fabricated using 160 mesh screens. This consistency is attributed to two factors: First, the Te content in the precursor is relatively low compared to Ag2Se. Second, all films were annealed under the same SPS conditions, which involved high temperature and pressure, ensuring uniform densification and minimal influence of additional Te on film morphology. Further analysis of the Ag2Se film with 5 wt.% Te, including secondary electron (SE) and backscattered electron (BSE) images, along with the corresponding EDS maps, is shown in Fig. 2h, i. These results confirm the presence of Ag, Se, and Te elements. Te nanorods are observed filling the gaps between the Ag2Se grains, effectively reducing the porosity of the film, which aligns with our previous findings18. Additional SEM and EDS results for films with different Te contents are available in Supplementary Figs. 7–9 for reference.

To examine the nanostructure of the as-fabricated Ag2Se/Te film, particularly the Te-doped regions, we used the focused ion beam (FIB) technique to prepare a lamella specimen of Ag2Se with 5 wt.% Te. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was then performed to characterize the sample. Figure 3a shows a low-magnification scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image of the lamella sample. Figure 3b presents an enlarged high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) STEM image along with EDS maps for the individual Ag, Se, and Te elements, derived from a selected area in Fig. 3a. These images reveal a uniform distribution of Ag, Se, and Te, indicating homogeneous Te doping (diffusion) throughout the sample. Figure 3c displays a high-magnification, spherical aberration-corrected scanning TEM (Cs-STEM) HAADF image, with insets showing a magnified Cs-STEM HAADF image and a fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern. This confirms that the image was captured along the [0 1 0] zone axis of the Ag2Se matrix, demonstrating a well-ordered lattice structure and confirming the high crystallinity of the prepared film. Figure 3d presents a magnified high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image from the same region, showing lattice contrast that indicates lattice distortion. This distortion is attributed to the substitution of Se2− ions by Te2− ions within the Ag2Se lattice, which aligns with the results from the XRD Rietveld refinement. Figure 3e, f shows low- and high-magnification HRTEM images of the Ag2Se matrix, taken from an area without noticeable lattice contrast, as seen in Fig. 3d. The inset shows the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern with indexed information, confirming the imaging direction is along the [0 1 0] zone axis of Ag2Se. Figure 3g displays a high-magnification HRTEM image of a selected area with lattice contrast, and Fig. 3h shows corresponding strain maps along various directions. These maps indicate that the strain is primarily along the x-direction, caused by the lattice distortion resulting from the Te2− substitution in the Ag2Se lattice. Lastly, Fig. 3i presents inverse Fourier transform images of Fig. 3g, revealing the presence of potential edge-like dislocations. The inset provides an enlarged view of these dislocations, which are likely caused by the substitution of Se2− by Te2− within the Ag2Se lattice.

a Low-magnification high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image of the specimen fabricated by focused ion beam (FIB) technique. b Enlarged HAADF image and its corresponding EDS maps for Ag, Se, and Te elements. c Magnified spherical aberration-corrected scanning TEM (Cs-STEM) HADDF image taken from the selected area of (a). The inset shows the corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern with the view zone axis of [0 1 0]. d Low-magnification TEM image derived from (a). e High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image taken from (d). f Magnified HRTEM image of the Ag2Se matrix. The inset shows the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern viewing along the (0 1 0) direction. g HRTEM image with potential lattice imperfections taken from (d). h Corresponding strain maps along different directions. i Inverse Fourier transform image taken from (g) presents the potential presence of edge-like dislocations. The inset shows a magnified area with a potential edge-like dislocation.

To examine the impact of Te content x (x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.%) on the thermoelectric performance of Ag2Se films, we measured their properties over a temperature range of 303 K to 383 K. Figure 4a–c presents the temperature-dependent S, σ, and S2σ of Ag2Se/Te films. As x increases from 0 to 5 wt.%, both S and σ improve, resulting in an optimized S2σ of 25.7 μW cm−1 K−2 at 303 K. However, when x increases from 7.5 to 10 wt.%, excessive formation of the secondary Te phase within the Ag2Se film leads to a decline in σ, counteracting the increase in S and reducing S2σ. To further understand the variations in S and σ at room temperature, we conducted Hall measurements to evaluate n and μ as functions of x (Fig. 4d). As x increases from 0 to 5 wt.%, μ gradually improves because Te fills the pores in the Ag2Se film. However, when x increases from 7.5 to 10 wt.%, the excessive Te phase enhances phonon scattering, leading to a reduction in μ. Regarding n, it decreases as x increases from 0 to 10 wt.%. This trend, along with the increase in S, can be explained by the calculated bandgap changes based on first-principles DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 10): Ag2Se has a bandgap of 0.07 eV, while Te-doped Ag2Se exhibits a slightly larger bandgap of 0.127 eV. The widening bandgap after Te doping makes it more difficult for electrons to transition to the conduction band, resulting in lower n and higher S.

a Seebeck coefficient (S), b electrical conductivity (σ), and c power factor (S2σ) as a function of temperature. d Measured carrier concentration (n) and mobility (μ) at 303 K. e Room-temperature effective mass (m*) and deformation potential (Edef) calculated by the single parabolic band (SPB) model. f Comparison of predicted S2σ by the SPB model and measured S2σ as a function of n. g Room-temperature thermal conductivity (κ), h and corresponding lattice thermal conductivity (κl) and electronic thermal conductivity (κe) as a function of x. i Comparison of ZT values as a function of x at 303 K.

To better understand the variations in μ and n with different Te contents, Fig. 4e compares the effective mass (m*) and deformation potential (Edef) as functions of x, based on the single parabolic band (SPB) model. As x increases from 0 to 7.5 wt.%, m* gradually rises and then stabilizes. This trend may be attributed to the formation of a secondary Te phase within Ag2Se. The phase boundaries between Te and Ag2Se can induce an energy filtering effect, selectively blocking low-energy carriers, and enhancing the S. To confirm the presence of this mechanism, we performed first-principles DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 10). The results show that the bandgap of Te is nearly 0 eV, while Ag2Se has a bandgap of 0.07 eV, and Te-doped Ag2Se exhibits an increased bandgap of 0.127 eV. The significant differences in band structures among Te, Ag2Se, and Te-doped Ag2Se create an effective energy barrier, facilitating the energy filtering effect. When x increases from 7.5 to 10 wt.%, m* decreases due to the suppression of n, as the secondary Te phase within Ag2Se becomes saturated. Regarding Edef, it initially decreases with x increase from 0 to 5 wt.% since Te atoms fill gaps within the Ag2Se matrix, altering the material’s overall deformation behavior, consistent with previous research18. However, as x increases from 5 to 7.5 wt.%, Edef gradually rises, indicating reduced lattice deformability. This suggests that Te doping becomes more dominant once the Te content within Ag2Se reaches saturation. Figure 4f compares the S2σ predicted by the SPB model with measured S2σ as a function of n, demonstrating that Te doping effectively optimizes n to its optimal range.

To evaluate the thermal transport properties of Ag2Se films with varying Te content (x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.%), we measured the in-plane thermal diffusivity (D) using the photothermal intensity technique (PIT) with an alternating current (AC) method. The κ was then calculated using the equation κ = D × Cp × ρ, where ρ is the mass density (determined via the specific gravity method) and Cp is the specific heat capacity. The measured D values are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, while Fig. 4g presents κ as a function of x at room temperature. As x increases from 0 to 5 wt.%, κ rises due to improved densification, as Te fills the pores within the Ag2Se films. However, when x increases beyond 7.5 wt.%, κ declines due to enhanced phonon scattering caused by lattice imperfections and excessive phase boundaries. To distinguish the contributions of κe and κl, we calculated κe using the equation κe = LσT and determined κl as κl = κ − κe, where the Lorentz number (L) was derived from the SPB model (Supplementary Fig. 12). Figure 4h illustrates the variation of κe and κl with x at room temperature. From 0 to 5 wt.% Te, κe increases due to a rise in σ associated with enhanced film density, while κl decreases as stronger phonon scattering occurs from lattice distortions and additional boundaries. Beyond 7.5 wt.% Te, κe declines as excessive Te phase formation intensifies phonon scattering and reduces σ. Meanwhile, κl increases, indicating that the excess Te phase contributes to lattice thermal transport. Figure 4i shows the ZT values as a function of Te content, with a maximum ZT of 1.06 achieved at 303 K for the Ag2Se film containing 5 wt.% Te. This performance is competitive with previously reported results for screen-printed thermoelectric films.

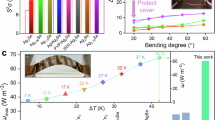

To assess the flexibility of Ag2Se films with varying Te content (x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.%), we conducted a bending test, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. Figure 5a shows the normalized resistance change (ΔR/R0) as a function of bending cycles at a radius (r) of 5 mm. The inset depicts the flexible film with r of 5 mm. After 1000 bending cycles, ΔR/R0 remains below 5% for all samples, demonstrating the excellent flexibility of the as-fabricated Ag2Se films. To evaluate the practical application potential of our films, we designed an F-TED featuring a triangular structure of p-n junctions. The p-type legs were fabricated using commercial Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3 powders through screen printing, the same process used to produce the Ag2Se films. To enhance the thermoelectric performance of Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3, Te was also introduced into the films, with an optimal Te content of 5 wt.%, as determined in our previous study18. The thermoelectric properties of Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3 with 5 wt.% Te at room temperature are provided in Supplementary Table 3. For the device electrodes, we selected Ag paste and Cu tape based on the band banding concept17,86. For the p-type leg (Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3), we employed Ag as the contact material. Ag has a work function of 4.3-4.7 eV, which is reasonably close to or higher than the Fermi level of p-type Bi-Sb-Te alloys (typically 4.5-4.7 eV), enabling near-ohmic contact for hole injection86,87. For the n-type leg (Ag2Se), we used Cu, which has a work function of around 4.5 eV86,88. This aligns well with the lower Fermi level of n-type Ag2Se (typically 4.1–4.3 eV), promoting efficient electron injection and minimizing potential Schottky barriers86. Additionally, these materials offer low electrical resistance, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness, making them well-suited for flexible thermoelectric applications17. Figure 5b illustrates the structure and dimensions of the fabricated device. Its design effectively extends the leg length without increasing vertical space, enabling a higher ΔT in compact environments such as electronics. To assess thermal stability, we conducted ANSYS simulations of the temperature distribution (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). These results further demonstrate that the device featuring a triangular structure can establish a larger ΔT compared to the conventional parallel-structured device when heat is applied to the hot side. Figure 5c presents the experimental output voltage (V) and power (P) as functions of loading current (I) at different ΔTs. The maximum open-circuit voltage (Voc) and P can reach 77.6 mV and 26.2 μW, respectively, at ΔT of 20 K. Figure 5d compares the ω as a function of ΔT. The inset shows an infrared image of the temperature distribution across the device under an applied ΔT. A competitive ω of 1.9 mW cm−2 is achieved when ΔT is 20 K and thereby leading to an outstanding ωn of 4.8 μW cm−2 K−2. To evaluate mechanical flexibility, we performed bending tests. Figure 5e shows the measured ΔR/R0 as a function of r and bending cycles. The inset displays the device under r of 8 mm. Even after 1000 cycles at r of 5 mm, ΔR/R0 remains below 10%, demonstrating excellent flexibility and stability. The device’s potential for wearable electronics is further examined. When worn on a human arm, it generates a Voc of 10.88 mV, as shown in Fig. 5f. Additional dimension details and photographs about the device are shown in Supplementary Figs. 16-17. Additionally, Fig. 5g shows that the device provides a stable Voc when worn on a human arm while walking or sitting, confirming its capability to harness body heat for energy generation. The cooling performance of the device was also evaluated with and without heatsinks, as shown in the Supplementary Figs. 18. Figure 5h presents an infrared image of its temperature distribution when operating as a cooler under an input current of 69.8 mA. A temperature difference of 16.8 K is achieved under this condition. Figure 5i further plots the ΔTmax as a function of input current, showing that ΔTmax reaches 29.8 K at 92.4 mA without external heat sinks. These results confirm that the device is well-suited for various application environments.

a Measured normalized resistance change (ΔR/R0) of the Ag2Se thin films with different Te contents (x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 wt.%) as a function of different bending cycles at 5 mm bending radius (r). The inset depicts the flexible film with r of 5 mm. b Schematic illustration of the size and structure of as fabricated device. c Experimental output voltages (V) and output powers (P) versus loading current (I) with different temperature differences (ΔTs). d Determined output power densities (ω) as a function of ΔT. The inset displays the infrared photograph showing the temperature distribution on the as-fabricated device after applying a ΔT. e Measured ΔR/R0 of as-fabricated device versus different r with different bending cycles. The inset depicts the as-fabricated device with a r of 8 mm. f Photograph of as-fabricated device worn on a human arm and can provide open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 10.88 mV. g Experimental Voc of the device worn on a human arm during sitting and walking as a function of time (0 ~ 130 s). The inset displays an infrared photograph showing the temperature distribution of the device worn on a human arm while seated. h The infrared photograph shows the temperature distribution of the device functioning as a cooler after an input current of 69.8 mA is applied. i Maximum cooling performance (ΔTmax) of the device as a function of input current.

In summary, we successfully fabricate high-performance Ag2Se films using screen printing followed by spark plasma sintering. The introduction of Te during fabrication significantly enhanced film density while creating an energy filtering effect that selectively blocked low-energy carriers, leading to increased S and σ. Additionally, Te diffusion doping occurred during annealing at the Ag2Se-Te boundaries, where Te substitution for Se introduced lattice imperfections, further increasing phonon scattering and reducing κ1. As a result, the Ag2Se films with 5 wt.% Te achieved an exceptional S2σ of 25.7 μW cm−1 K−2 and a competitive ZT of 1.06 at 303 K. The flexibility of the fabricated films was also evaluated. Even after 1000 bending cycles, the ΔR/R0 remained below 5%, demonstrating excellent mechanical durability. Furthermore, we designed an F-TED incorporating a triangular p-n junction structure, coupling 10 pairs of n-type Ag2Se + 5 wt.% Te films with previously optimized p-type Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3 + 5 wt.% Te films. This device achieved a ωn of 4.8 μW cm−2 K−2 at a ΔT of 20 K and provided a ΔTmax of 29.8 K with a current of 92.4 mA. These findings indicate the potential of the fabricated thermoelectric materials and devices for diverse energy-harvesting and cooling applications.

Methods

Chemicals

Selenium (Se, 99.99 %, Sigma-Aldrich), silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99 %, Sigma-Aldrich), ethylene glycol (EG, 99 %, Sigma-Aldrich), tellurium dioxide (TeO2, 99.99 %, Sigma-Aldrich) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96 %, Sigma-Aldrich) were used for solvothermal synthesis without further purification. Ethyl cellulose (Sigma-Aldrich), terpineol (Sigma-Aldrich), dibutyl phthalate (Sigma-Aldrich), and dispersant (Disperbyk-110, BYK USA Inc.) were used for fabricating the printing ink. Commercial Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3 powders (Zhongsheng Heng’an New Material Technology Co., Ltd) were used for fabricating p-type legs.

Silver selenide and tellurium synthesis

Se and AgNO3 were dissolved in EG (36 ml) with stirring by a magnetic stirrer to form a clear solution. After that, 4 ml NaOH (5 mol L–1) was dropped into the solution and formed the precursor solution. Similarly, TeO2 was dissolved in EG, and NaOH was added to the solution. The two prepared solutions were then separately sealed in two 125 ml polytetrafluoroethylene-lined stainless-steel autoclaves. The autoclaves were heated in an oven at 230 °C for 19 h, followed by natural cooling to room temperature. After the synthesis, the two types of products were cooled to room temperature naturally and then collected by centrifugation and washed with deionized water and ethanol several times. Finally, the washed products were dried in the oven at 60 °C for 24 h.

The n- and p-type film fabrication and flexibility test

Firstly, the binder solvent was synthesized by mixing ethyl cellulose (10 wt.%), terpineol (80 wt.%), and dibutyl phthalate (10 wt.%). The binder solvent was magnetically stirred for 2 h at 80 °C to produce a clear solution. After that, the solvothermally synthesized powder or commercial p-type powder (80 wt.%) mixed with binder solvent (7.5 wt.%), terpineol (10 wt.%), and dispersant (2.5 wt.%) to prepare printing ink. Next, it was stirred for 2 h to produce a homogeneous viscous solution. The prepared ink was printed onto the flexible polyimide (PI) substrate. The printed films were dried at 200 °C for 0.5 h and annealed in SPS (SPS-211Lx, Fuji Electronic Industrial CO., Ltd., Japan) with 3 MPa at 450 °C for 10 min. The bending test was conducted by simultaneously pushing movable blocks on both sides of the fabricated film, forcing it to bend to a defined radius.

Flexible device fabrication

The n-type and p-type films are each cut into 10 pairs (Supplementary Fig. 19), with dimensions of 1.2 cm × 0.5 cm, using a laser cutter (TROTEC SPEEDY 300). The resulting pieces are then attached to a PI substrate using silver paste and copper tape. The p-type and n-type elements are positioned at a 30° angle relative to the substrate, while the angle at the p–n junction is 120°.

Characterization

The morphology and structural characteristics of as-synthesized Ag2Se powder and film were analyzed through SEM (JEOL JSM-7100F, Supplementary Figs. 20, 21) and TEM (HITACHI HF 5000), respectively. The chemical composition and crystal lattice structure of the Ag2Se film were determined by XRD (Bruker-D8) with CuKα radiation over an angular range of 10–80° in 0.02° increments. The chemical valence states were detected using an XPS (Kratos Axis ULTRA, Kratos Analytical Limited, Japan). The element distribution and the chemical composition of the products were determined through EDS mapping and spot analysis (equipped in JEOL JSM-7100F and HITACHI HF 5000).

Thermoelectric property measurement

The n and μ values were measured by a Hall system (CH-70, CH-magnetoelectricity Technology Co., Ltd., China) under a magnetic field of up to 500 mT. The ZEM-3 was used to measure the S and σ of the Ag2Se film from 303 to 383 K. The κ values were calculated by the formula κ = D × Cp × ρ89, where D is the thermal diffusivity and Cp is the specific heat capacity. D was measured by a laser flash method (LaserPIT, Advance Riko., Inc., Japan) along the in-plane direction. Based on the porosity of the films determined via ImageJ analysis, the κ was further corrected using the Maxwell–Eucken model90. The κe was calculated using κe = LσT89, where L is the Lorenz number. The results were measured more than five times to promise precision.

Device performance evaluation

A custom-built measurement setup incorporating two multimeters/DC power supply units (KEYSIGHT U3606B and Keithley K2400) was employed to characterize the output voltage and source current of the thermoelectric device. For real-time application measurements, tests were conducted on the wrists of ten volunteers. The Voc was recorded using the KEYSIGHT U3606B multimeter, while the corresponding temperature difference across the device was simultaneously monitored using an infrared thermal camera (see Supplementary Fig. 22).

Data availability

The data generated in this study is provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Qin, B., Kanatzidis, M. G. & Zhao, L.-D. The development and impact of tin selenide on thermoelectrics. Science 386, eadp2444 (2024).

Liu, M., Zhang, X., Zhang, S. & Pei, Y. Ag2Se as a tougher alternative to n-type Bi2Te3 thermoelectrics. Nat. Commun. 15, 6580 (2024).

Ding, Y. et al. High performance n-Type Ag2Se film on nylon membrane for flexible thermoelectric power generator. Nat. Commun. 10, 841 (2019).

Shi, X.-L., Zou, J. & Chen, Z.-G. Advanced thermoelectric design: from materials and structures to devices. Chem. Rev. 120, 7399–7515 (2020).

Yang, D. et al. Flexible power generators by Ag2Se thin films with record-high thermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 15, 923 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. Flexible thermoelectrics based on ductile semiconductors. Science 377, 854–858 (2022).

Shi, X.-L. et al. Advancing flexible thermoelectrics for integrated electronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 9254–9305 (2024).

Liu, Q.-Y. et al. Advances and challenges in inorganic bulk-based flexible thermoelectric devices. Prog. Mater. Sci. 150, 101420 (2025).

Zheng, Z.-H. et al. Harvesting waste heat with flexible Bi2Te3 thermoelectric thin film. Nat. Sustain. 6, 180–191 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. High-performance Ag2Se-based thermoelectrics for wearable electronics. Nat. Commun. 16, 5002 (2025).

Kleinhanns, T. et al. A route to high thermoelectric performance: solution-based control of microstructure and composition in Ag2Se. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400408 (2024).

Abusa, Y. et al. A recipe for a great meal: a benchtop route from elemental se to superior thermoelectric β-Ag2Se. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11382–11391 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Interfacial bonding enhances thermoelectric cooling in 3D-printed materials. Science 387, 845–850 (2025).

Chen, Y.-X. et al. Deviceization of high-performance and flexible Ag2Se films for electronic skin and servo rotation angle control. Nat. Commun. 15, 8356 (2024).

Lei, Y. et al. Microstructurally tailored thin β-Ag2Se films towards commercial flexible thermoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 34, 2104786 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Fully inkjet-printed Ag2Se flexible thermoelectric devices for sustainable power generation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2141 (2024).

Zavanelli, N. & Yeo, W.-H. Advances in screen printing of conductive nanomaterials for stretchable electronics. ACS Omega 6, 9344–9351 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. Nanobinders advance screen-printed flexible thermoelectrics. Science 386, 1265–1271 (2024).

Hatala, M., Gemeiner, P., Hvojnik, M. & Mikula, M. The effect of the ink composition on the performance of carbon-based conductive screen printing inks. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. 30, 1034–1044 (2019).

Cao, T. et al. Advancing Ag2Se thin-film thermoelectrics via selenization-driven anisotropy control. Nat. Commun. 16, 1555 (2025).

Cao, T. et al. Indium-doping advances high-performance flexible Ag2Se thin films. Adv. Sci. 12, 2500364 (2025).

Wu, H. et al. Sandwich engineering advances ductile thermoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 2503020 (2025).

Xin, C. et al. Solution-processed flexible n-Type S-doped Ag2Se thermoelectric generators for near-ambient-temperature energy harvest. Mater. Today Energy 33, 101266 (2023).

Shi, X.-L. et al. Advances in flexible inorganic thermoelectrics. EcoEnergy 1, 296–343 (2023).

Shi, J. et al. Anisotropy engineering in solution-derived nanostructured Bi2Te3 thin films for high-performance flexible thermoelectric devices. Chem. Eng. J. 458, 141450 (2023).

Xie, J. et al. Flexible pCu2Se-nAg2Se thermoelectric devices via in situ conversion from printed Cu patterns. Chem. Eng. J. 435, 135172 (2022).

Du, J. et al. Inkjet Printing Flexible Thermoelectric Devices Using Metal Chalcogenide Nanowires. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213564 (2023).

Mallick, M. M. et al. High figure-of-merit telluride-based flexible thermoelectric films through interfacial modification via millisecond photonic-curing for fully printed thermoelectric generators. Adv. Sci. 9, 2202411 (2022).

Chen, B. et al. Flexible thermoelectric generators with inkjet-printed bismuth telluride nanowires and liquid metal contacts. Nanoscale 11, 5222–5230 (2019).

Mallick, M. M. et al. New frontier in printed thermoelectrics: formation of β-Ag2Se through thermally stimulated dissociative adsorption leads to high ZT. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 16366–16375 (2020).

Yuan, Z. et al. High-performance micro-radioisotope thermoelectric generator with large-scale integration of multilayer annular arrays through screen printing and stacking coupling. Energy Technol. 9, 2001047 (2021).

Feng, J., Zhu, W., Deng, Y., Song, Q. & Zhang, Q. Enhanced antioxidation and thermoelectric properties of the flexible screen-printed Bi2Te3 films through interface modification. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2, 2828–2836 (2019).

Feng, J. et al. Enhanced electrical transport properties via defect control for screen-printed Bi2Te3 films over a wide temperature range. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 16630–16638 (2020).

Mallick, M. M. et al. High-performance Ag–Se-based n-type printed thermoelectric materials for high power density folded generators. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 19655–19663 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. Scalable printing high-performance and self-healable Ag2Se/terpineol nanocomposite film for flexible thermoelectric device. Energy 296, 131232 (2024).

Zhu, W., Deng, Y., Gao, M. & Wang, Y. Hierarchical Bi–Te based flexible thin-film solar thermoelectric generator with light sensing feature. Energ. Convers. Manag. 106, 1192–1200 (2015).

Cao, Z., Koukharenko, E., Tudor, M. J., Torah, R. N. & Beeby, S. P. Flexible screen printed thermoelectric generator with enhanced processes and materials. Sens. Actuat A Phys. 238, 196–206 (2016).

Chen, B. et al. Inkjet printing of single-crystalline Bi2Te3 thermoelectric nanowire networks. Adv. Electron Mater. 3, 1600524 (2017).

Gao, J. et al. A novel glass-fiber-aided cold-press method for fabrication of n-Type Ag2Te nanowires thermoelectric film on flexible copy-paper substrate. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 24740–24748 (2017).

Varghese, T. et al. High-performance and flexible thermoelectric films by screen printing solution-processed nanoplate crystals. Sci. Rep. 6, 33135 (2016).

Chang, P.-S. & Liao, C.-N. Screen-printed flexible thermoelectric generator with directional heat collection design. J. Alloy. Compd. 836, 155471 (2020).

Liang, J., Zhang, X. & Wan, C. From brittle to ductile: a scalable and tailorable all-inorganic semiconductor foil through a rolling process toward flexible thermoelectric modules. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 52017–52024 (2022).

Jiang, C. et al. Ultrahigh performance of n-type Ag2Se films for flexible thermoelectric power generators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 9646–9655 (2020).

Hou, S. et al. High performance wearable thermoelectric generators using Ag2Se films with large carrier mobility. Nano Energy 87, 106223 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Scalable-produced 3D elastic thermoelectric network for body heat harvesting. Nat. Commun. 14, 3058 (2023).

Palaporn, D., Mongkolthanaruk, W., Faungnawakij, K., Kurosaki, K. & Pinitsoontorn, S. Flexible thermoelectric paper and its thermoelectric generator from bacterial cellulose/Ag2Se nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 3489–3501 (2022).

Gao, Q. et al. High power factor Ag/Ag2Se composite films for flexible thermoelectric generators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 14327–14333 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Nanoengineering approach toward high power factor Ag2Se/Se composite films for flexible thermoelectric generators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 36587–36593 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Exceptionally high power factor Ag2Se/Se/polypyrrole composite films for flexible thermoelectric generators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2106902 (2022).

Kashyap, A. et al. Chemically transformed Ag2Te nanowires on polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for flexible thermoelectric applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401234 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. N-type flexible Bi2Se3 nanosheets/SWCNTs composite films with improved thermoelectric performance for low-grade waste-heat harvesting. Nano Energy 104, 107907 (2022).

Yusuf, A. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigation of the effect of filler material on the performance of flexible and rigid thermoelectric generators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 61275–61285 (2021).

You, H. et al. Flexible Bi2Te3-based thermoelectric generator with an ultra-high power density. Appl. Therm. Eng. 202, 117818 (2022).

Huo, W., Xia, Z., Gao, Y., Guo, R. & Huang, X. Flexible thermoelectric devices with flexible heatsinks of phase-change materials and stretchable interconnectors of semi-liquid metals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 29330–29340 (2023).

Zhu, S. et al. Simultaneous realization of flexibility and ultrahigh normalized power density in a heatsink-free thermoelectric generator via fine thermal regulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 1045–1055 (2022).

Moiroux, G., Tur, C., Bourgault, D. & Garden, J. L. High temperature difference in a new flexible thermoelectric bismuth telluride microgenerator. Sens. Actuat A Phys. 347, 113961 (2022).

Xu, Q. et al. High-performance, flexible thermoelectric generator based on bulk materials. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100780 (2022).

Hou, Y. et al. Whole fabric-assisted thermoelectric devices for wearable electronics. Adv. Sci. 9, 2103574 (2022).

Peng, J. et al. 3D extruded composite thermoelectric threads for flexible energy harvesting. Nat. Commun. 10, 5590 (2019).

Lee, B. et al. High-performance compliant thermoelectric generators with magnetically self-assembled soft heat conductors for self-powered wearable electronics. Nat. Commun. 11, 5948 (2020).

Jung, S.-J. et al. Porous organic filler for high efficiency of flexible thermoelectric generator. Nano Energy 81, 105604 (2021).

Abe, H. et al. Performance evaluation of flexible thermoelectric generator with Bi2Te3 thin-film. Appl. Therm. Eng. 248, 123258 (2024).

Park, J. W. et al. A flexible micro-thermoelectric generator sticker with trapezoidal-shaped legs for large temperature gradient and high-power density. Adv. Mater. Technol. 5, 2000486 (2020).

Shang, H. et al. Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3-based films for flexible thermoelectric devices. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 4552–4561 (2020).

Lincoln, B., Annie Sujatha, R., Veluswamy, P. & Majumdar, A. A hybrid ceramic-based flexible thermoelectric nanogenerator with enhanced thermopower for human energy harvesting. Energ. Convers. Manag. 292, 117364 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Stretchable nanolayered thermoelectric energy harvester on complex and dynamic surfaces. Nano Lett. 20, 4445–4453 (2020).

Ao, D.-W. et al. Assembly-free fabrication of high-performance flexible inorganic thin-film thermoelectric device prepared by a thermal diffusion. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2202731 (2022).

Lin, S. et al. Flexible thermoelectric generator with high Seebeck coefficients made from polymer composites and heat-sink fabrics. Commun. Mater. 3, 44 (2022).

Shi, T. et al. Modifying carbon fiber fabric for flexible thermoelectric energy conversion. Appl. Surf. Sci. 610, 155479 (2023).

Pires, A. L. et al. Printed flexible μ-thermoelectric device based on hybrid Bi2Te3/PVA composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 8969–8981 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. A flexible thermoelectric device based on a Bi2Te3-carbon nanotube hybrid. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 58, 80–85 (2020).

Varghese, T. et al. Flexible thermoelectric devices of ultrahigh power factor by scalable printing and interface engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1905796 (2020).

Banerjee, P. et al. Effect of particle-size distribution and pressure-induced densification on the microstructure and properties of printable thermoelectric composites and high energy density flexible devices. Nano Energy 89, 106482 (2021).

Choo, S. et al. Cu2Se-based thermoelectric cellular architectures for efficient and durable power generation. Nat. Commun. 12, 3550 (2021).

Yang, D. et al. High thermoelectric performance of aluminum-doped cuprous selenide thin films with exceptional flexibility for wearable applications. Nano Energy 117, 108930 (2023).

Cao, J. et al. Flexible elemental thermoelectrics with ultra-high power density. Mater. Today Energy 25, 100964 (2022).

Van Toan, N., Kim Tuoi, T. T. & Ono, T. High-performance flexible thermoelectric generator for self-powered wireless BLE sensing systems. J. Power Sources 536, 231504 (2022).

Toan, N. V. et al. Ultra-flexible thermoelectric generator based on silicone rubber sheet and electrodeposited thermoelectric material for waste heat harvesting. Energy Rep. 8, 5026–5037 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Ultrahigh performance PEDOT/Ag2Se/CuAgSe composite film for wearable thermoelectric power generators. Mater. Today Phys. 14, 100223 (2020).

Na, Y. et al. Energy harvesting from human body heat using highly flexible thermoelectric generator based on Bi2Te3 particles and polymer composite. J. Alloy. Compd. 924, 166575 (2022).

Jiang, C. et al. Ultrahigh performance polyvinylpyrrolidone/Ag2Se composite thermoelectric film for flexible energy harvesting. Nano Energy 80, 105488 (2021).

Yin, L. et al. CALPHAD accelerated design of advanced full-Zintl thermoelectric device. Nat. Commun. 15, 1468 (2024).

Yan, B. et al. Heat-sink-free solar-driven thermoelectric device for micro energy scavenging. Nano Energy 123, 109382 (2024).

Zeng, C. et al. Kirigami-inspired organic and inorganic film-based flexible thermoelectric devices with built-in heat sink. Nano Energy 121, 109213 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Design and experimental study of a compact thermoelectric device driven by solar heating and radiative cooling. Energy 4, 100146 (2024).

Zhang, Z. & Yates, J. T. Jr. Band bending in semiconductors: chemical and physical consequences at surfaces and interfaces. Chem. Rev. 112, 5520–5551 (2012).

Brodie, I., Chou, S. H. & Yuan, H. A general phenomenological model for work function. Surf. Sci. 625, 112–118 (2014).

Kumar, B., Kaushik, B. K. & Negi, Y. S. Perspectives and challenges for organic thin film transistors: materials, devices, processes and applications. J. Mater. Sci.-Mater. 25, 1–30 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of nanostructured n-type Bi2Te3 by suppressing te vacancy through non-equilibrium fast reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 391, 123513 (2020).

Wang, J., Carson, J. K., North, M. F. & Cleland, D. J. A new approach to modelling the effective thermal conductivity of heterogeneous materials. Int. J. Heat. Mass Trans. 49, 3075–3083 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The calculations were conducted in the National Computational Infrastructure, supported by the Australian government, for providing computational resources and services. The authors acknowledge the facilities, and the scientific and technical assistance, of the Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research Facility at the Centre for Microscopy and Microanalysis, The University of Queensland. This work was enabled using the Central Analytical Research Facility hosted by the Institute for Future Environments at QUT. Q. Sun acknowledges the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and Research Funding from West China School/Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, No. QDJF2022-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-G.C. and X.-L.S. supervised the whole project. W. C. prepared materials and measured the thermoelectric properties, conducted scanning electron microscope, designed device structures, fabricated devices, and measured the performance of thermoelectric device. J.Z., M.D., X.-L.S., Q.S., and Z.-G.C. provided data analysis support and financial support. M.L. provided principal calculation support. X.W. provides XRD analysis support. J.O. provided transmission microscopy support. W.C., B.H., T.C., N.L., X.-L.S., W.-D.L., and Z.-G.C. discussed the results. M.Z. and C.Z. provided device assembling and test support. W.C., X.-L.S., and Z.-G.C. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Li, M., Wang, X. et al. Flexible Ag2Se-based thin-film thermoelectrics for sustainable energy harvesting and cooling. Nat Commun 16, 7579 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62336-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62336-2

This article is cited by

-

Printed origami thermoelectric generator achieves > 20 Wm−² from low-grade heat via material and process design

Nature Communications (2026)