Abstract

Membrane nanofiltration (NF) has emerged as a prominent technology for efficient separations of ions, but state-of-the-art polyamide (PA) NF membranes are constrained by a pernicious tradeoff between water permeance and selectivity. This work conceives a versatile molecular engineering strategy to simultaneously improve water permeance and co-cation selectivity through molecular construction of cationic triazolyl heterocyclic polyamide (CTHP) nanofilms via scalable interfacial polymerization. Experimental data and molecular simulations reveal that the CTHP structures precisely regulate the subnanometer pore architecture and binding affinity with water and ions, affording advanced size-sieving and Donnan exclusion while facilitating water partitioning and transport. The exemplified PA membrane exhibits ultrahigh divalent cation rejections of over 99% with a 9-fold increase in monovalent/divalent cation sieving selectivity relative to the pristine benchmark, exceptional water permeance, and good fouling resistance. The implemented molecular engineering strategy holds broad prospects for the rational design of high-performance polymeric membranes for sustainable and precision separations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Precision discrimination of target ions and molecules from complex aqueous mixtures of similar species remains a considerable challenge in widespread applications such as water, clean energy, and resource reclamation1,2,3. Membrane nanofiltration (NF), featuring phase-free conversion separation, has evolved into a premier tool for sustainable water separation because of its high energy efficiency, low carbon footprint, compact design, and manufacturing scalability4,5. The rapid dissemination of NF technology relies on high-performance membranes that ideally have high values of both water permeance and selectivity to fully exploit the prominent process advantages, but such a combination is exceedingly difficult to achieve particularly for polymeric membranes, as the material properties that affect solute transport would, in turn, exert influence on water permeation6,7,8.

Polyamide (PA) thin-film composite membranes are state-of-the-art NF membranes that are particularly attractive for water filtration in practical modules across all scales9,10,11,12. However, the deleterious tradeoff between water permeance and membrane selectivity consistently poses a stumbling block for further performance advancement, where increasing water permeance is inevitably accompanied by a diminished ability to selectively reject solutes13,14. According to the prevailing membrane separation mechanisms, effective strategies for rationally regulating mass transport across the PA membranes hinge on well-defined pore sizes with a narrow size distribution, finely tuned interactions with the permeants of interest, and a thin PA selective layer15,16,17. Innovative materials and fabrication methods that can precisely regulate PA chemistry and nanostructures have therefore become essential pursuits of academic research.

A prevalent approach that has been widely adopted to increase the permselectivity of PA membranes toward charged species involves surface charge optimization to strengthen electrostatic exclusion via in situ and/or post-synthetic modifications18,19. However, most of the approaches reported thus far have primarily focused on promoting solute rejection or selectivity rather than overcoming the permeance/selectivity tradeoff threshold20,21. Recently, exceptional size sieving ability and co-cation selectivity have been achieved by trailblazing studies that use interfacial modulators to narrow the pore size distribution of the PA layer22,23,24,25. Unfortunately, a significant decrease in water permeance is usually accompanied by a concomitant increase in water transport resistance23,24. Many studies have also focused on exploring advanced membrane materials, ranging from biological ion channels and aquaporins to two-dimensional nanomaterials such as vermiculite and graphene, as well as emerging microporous materials including zeolites, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIM), conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs), macrocycles, and porous organic cages, some of which achieved remarkable permselectivity with unprecedented combinations of high permeance and selectivity26,27,28. Although the practicality of these intriguing materials is markedly restricted by many daunting limitations that vary from inherent low structural stability to inferior material availability and the feasibility of membrane fabrication on a large scale, their distinct structural features underscore the importance of well-defined pore sizes and finely regulated mutual interactions in achieving exceptional molecular sieving capabilities and water transport rates29,30,31. Hereupon, we speculate that multifunctional monomers with synthetically engineered chemistry that enable the formation of a PA structure that not only imparts subnanometer pores with a narrow size distribution but also provides low resistance for water transport are likely to achieve disruptive improvements in both water permeance and solute selectivity. Unfortunately, there is currently a lack of rational material design and feasible membrane fabrication strategies to accomplish this arduous undertaking.

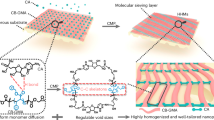

Herein, we demonstrate a facile and effective molecular engineering approach for precise regulation of the mass transfer behavior of PA membranes to circumvent the formidable permeance/selectivity tradeoff in nanofiltration for ion discrimination. Our strategy is contingent on molecular-level control over the nanoporous structure of the PA nanofilm and its interactions with water and ions through in situ construction of cationic triazolyl heterocyclic polyamide (CTHP) structures via scalable interfacial polymerization (IP) using rationally designed quaternary triazole ammonium monomers. Experimental data and molecular simulations revealed that the CTHP structures endow the PA nanofilm with well-defined subnanometer pores with a narrow size distribution and abundant positive charge but low intrinsic water transport resistance, which not only synergistically enhances steric hindrance sieving and Donnan exclusion but also facilitates the permeation of water. The advantages of this molecularly engineered PA structure were demonstrated by its exceptional performance within precise co-cation sieving (Fig. 1a), achieving a 9-fold increase in monovalent/divalent cation selectivity with a tripled water flux relative to the benchmark, successfully reconciling the tradeoff threshold. Considering the diverse array of monomer chemistries, the implemented design strategy provides a promising gateway to advance the development of effective PA membranes with exceptional permselectivity for precise ion separations toward clean water and renewable energy.

a Working principle of precision co-ion separation via nanofiltration. b Schematic diagram of the interconnected subnanometer-sized pores in a desired PA nanofilm with high selectivity and low water transport resistance, and three-dimensional view of an amorphous cell of the PA polymer (cell size: 65 × 65 × 65 Å3). c Synthetic reaction formula of DAT-NH2 isomers and the visualized conformation of their atomic electrostatic potential. d 1H NMR spectra and liquid chromatography (upper left inset) of DAT-NH2 isomers. e Schematic illustration of interfacial polymerization between DAT-NH2/PEI and TMC at the water/hexane interface to form a PA nanofilm. f Molecular structure of the DP-M PA nanofilm (left) and its corresponding polymer chain structure derived from an amorphous cell generated by molecular dynamic (MD) simulations. g FT-IR spectra of the DP-M and P-M PA nanofilms. h N 1 s XPS spectra of the DP-M PA nanofilm. The N1s core level spectrum was deconvoluted into three components located at 399.7, 400.4, and 401.7 eV corresponding to N − (C = O) − , N(H) − C − , and N+ − C − , respectively.

Results

Synthesis of DAT-NH2 monomer and fabrication of PA membranes

Figure 1b shows the conceptual illustration of the ideal PA structure that we intend to construct to circumvent the permeance/selectivity tradeoff in precision nanofiltration (NF). Specifically, the PA layer is synthetically designed with well-defined permeate-PA binding affinity and steric sieving selectivity to simultaneously manipulate the enthalpy and entropy barriers for water and solute transport32,33. To realize this design strategy, we molecularly constructed a multifunctional monomer with primary amine dangling and a highly polarized triazolyl heterocyclic ring bearing quaternary ammonium such as 3,5-diamino-4/1-(2-aminoethyl)−1,2,4-triazole (DAT-NH2, Fig. 1c). Our pursuit of such a molecular architecture was inspired by seminal studies revealing that nitrogen-containing heterocycles, like imidazole derivatives, could induce energetically preferential interactions with water molecules to facilitate their permeation during membrane filtration, while the primary amine pendants with concentrated electron density concurrently provide highly reactive sites to crosslink with trimesoyl chloride (TMC) to form tightly crosslinked PA network with enhanced hydrophilicity and interconnected subnanometer pores. We speculate that these effects are likely to be maximized in triazole-derived compounds, given its five-membered aromatic ring that contains three sp2-hybridized nitrogen atoms and two carbon atoms. Electrostatic potential mapping and quantitative analysis of the key molecular and electronic descriptors of a series of five-membered rings with various numbers of nitrogen heteroatoms by density functional theory (DFT) revealed that the triazole unit possesses the most asymmetric charge distribution and the largest dipole moment (3.974 Debye) (Supplementary Fig. 1). These features suggest that the triazole moiety may introduce localized hydrophilic domains within the PA polymer matrix due to its high polarity and electron delocalization, which could enhance water affinity and thus facilitate transport. DFT-based electronic structure analyses of the DAT-NH2 isomers and PEI fragments further demonstrated that the former exhibits significantly higher molecular polarity, enhanced nucleophilicity, and denser positive electrostatic potentials than the latter (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1 and 2), further substantiating our hypothesis that the DAT-NH2 isomers can enable the formation of highly ionizable cationic PA structures with preferential water transport pathways.

The molecularly designed DAT-NH2 monomer was synthesized via a one-pot quaternization reaction between 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazole and 2-bromoethylamine in dimethylformamide (DMF) and then purified by nonsolvent-induced precipitation (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3 and 4). Intriguingly, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) measurements reveal that a mixture of 3,5-diamino-4/1-(2-aminoethyl)−1,2,4-triazole isomers was obtained from the synthesis. As shown in Fig. 1d, two distinct peaks with almost the same intensity and area ratio were observed in the LC chromatogram pattern. Subsequent MS analysis of these two peaks showed one coincident peak at m/z 143 (Supplementary Fig. 5), which is in good agreement with the molecular weight of the DAT-NH2 isomers (C4N6H11+, MW = 143 Da). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra corroborate these results, where four 1H NMR peaks corresponding to the two types of protons in each isomer are spotted at 3.11 (labeled H I), 3.30 (labeled H I), 3.35 (labeled H II), and 3.99 (labeled H II) ppm. The area ratios of the two peaks (H I/H II) in the 1H NMR spectrum were measured to be 0.88 and 1.04 for the isomers, which are close to the theoretically expected values based on the DAT-NH2 chemical structure. The visualized atomic electrostatic potential image of DAT-NH2 intuitively proclaims the positive charge characteristics of the triazole ring, and quantitative analysis of the molecular van der Waals surface electrostatic potential (ESP) shows that the distribution area and intensity of the positive ESP of the DAT-NH2 isomers are greater than the negative values (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 6).

A self-sustaining PA thin film with good stability immediately formed when DAT-NH2 was brought in contact with TMC at the water/hexane interface (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating a high polymerization rate between DAT-NH2 and TMC. DFT calculations further confirmed the high nucleophilic substitution reactivity of the amino groups on DAT-NH2 toward acyl chloride (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Comprehensive ESP and average local ionization energy (ALIE) analyses reveal that the backbone and chemical functional moieties of the PA structures formed by the two isomers with TMC are almost identical (Supplementary Fig. 10). Therefore, the DAT-NH2 isomers were directly used for PA membrane preparation without further purification. A continuous PA nanofilm can also be in situ synthesized via a similar interfacial polymerization (IP) procedure on top of a polyethersulfone (PES) substrate to prepare robust PA thin-film composite membranes for NF tests (Supplementary Fig. 11). Unfortunately, we observed that the obtained DAT-NH2/TMC PA membrane experienced severe water swelling and thus relatively low permselectivity were obtained in nanofiltration (Supplementary Fig. 12), likely owing to the enhanced hydrophilic nature of the cationic triazolyl heterocyclic structures. We thereby further modified the PA chemical structure by using polyethyleneimine (PEI) as the comonomer during IP to increase the membrane stability and separation performance (Fig. 1e, f). PEI is a benchmark monomer that is widely used for the synthesis of positively charged PA NF membranes (Supplementary Fig. 13). Synthesis condition optimization experiments confirmed that the DP-M membrane fabricated with a 0.06 wt% DAT-NH2 shows an optimum combination of water permeance and ion selectivity in addition to the exceptional robustness (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15), substantially exceeding those of the PA membrane formed solely by PEI (denoted as the P-M benchmark). The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) peaks observed at 1621 cm−1, 1806 cm−1, and 1705 cm−1 are associated with the amide I band, which arises from the stretching vibration of C = O and the coupling with the bending of N–H in subtly different chemical environments (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 16), validating the formation of PA structure. The quaternary ammonium peak at 401.8 eV in the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of DP-M (Fig. 1h and Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18) confirms the presence of DAT-NH2 moieties in the PA layer. It is noteworthy that a significant decline in the O/N ratio was observed by DP-M compared with that of the P-M benchmark, where the O/N ratio decreases from ~1.50 to 0.96 (Supplementary Table 3), suggesting a substantial increase in the PA crosslinking degree of DP-M. The elevated crosslinking degree constricts the space between the stacked polymer chains, thus diminishing the pore sizes and augmenting the mechanical strength of the PA nanofilm (Supplementary Fig. 15). According to the chemical characterization and molecular simulations, the DAT-NH2 modulated PA layer of DP-M has a semirigid 3D polyamide network with a large amount of intrinsic positive charges and smaller chain space compared to the P-M benchmark (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20).

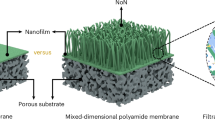

Morphological and structural characterization of DP-M PA membrane

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images corroborate the uniformity and integrity of the formed PA thin layer at the macroscopic scale (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 21). At a finer scale, the PA layer of DP-M appears a smooth and compact surface, whereas the counterpart of the P-M benchmark shows a crumpled surface with numerous ridged wrinkles unequivocally seen on top. This surface morphological discrepancy was further manifested by the atomic force microscopy (AFM) data, where the surface roughness of DP-M (Rq = 3.44 nm) is distinctly lower than that of P-M (Rq = 9.09 nm) (Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Fig. 22). A smooth surface is conducive to alleviating the fouling tendency. Cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showcase that DP-M has an low PA thickness of 59 ± 2 nm (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. 23), which is much thinner than that of the P-M benchmark (i.e., 88 ± 2 nm). The significantly reduced PA thickness might be attributed to the rapid formation of a relatively dense nascent PA film mediated by DAT-NH2 at an initial stage of IP (Supplementary Fig. 24), which subsequently stymies the diffusion of aqueous monomers at the interface and thus suppresses the subsequent growth of the PA nanofilm34,35. On the other hand, the positively charged structure of DAT-NH2 may slow down the diffusion of PEI towards the interface via H-bonding interactions, further retarding the growth of the PA film36,37,38,39,40. In the context of membrane filtration, a thinner PA selective layer spontaneously confers shorter transport pathways and lower water penetration resistance, which is favorable for achieving high water permeance.

a, b Surface FESEM images. c, d 2D and 3D AFM images. e, f Cross-sectional TEM images. Top: P-M. Bottom: DP-M. g Pore radius distribution of PA membranes obtained by PEG rejection tests (the inset illustrates the geometric standard deviation). h Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the fractional free volume (FFV) of PA layers (left). The dark blue and gray colors represent the voids between the polymer chains and the space occupied by the polymer skeleton, respectively. Representative porous molecular structures of the DP-M and P-M PA networks (right). i MD simulations of the pore radius distribution of the PA nanofilms. j Zeta potential as a function of pH. k Summary of the MWCO, water contact angle (CA), root mean square roughness (Rq), FFV, polyamide layer thickness, and zeta potential (ZP) at pH = 6 for DP-M and P-M.

The rejection tests with neutral solutes of polyethylene glycol (PEG) indicate that DP-M has a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 245 Da, almost two times smaller than that of the P-M benchmark (MWCO = 479 Da, Supplementary Fig. 25). Correspondingly, a small effective mean pore radius of 2.8 Å accompanied by a narrow size distribution was achieved by DP-M (Fig. 2g), whereas P-M shows a relatively larger mean pore radius of 3.1 Å and broader pore size distribution, in accordance with our design strategy and the XPS-derived crosslinking degree (Fig. 1b, h). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were further performed to construct realistic structural models to glean molecular-level insights into the microporous structure of the PA layer. As shown in Fig. 2h, the fractional free volume (FFV) of DP-M and P-M PA layers are ~10.3% and 21.6%, respectively. The pore size survey conducted by MD molecular simulations substantiates that the majority of pores within the DP-M PA layer are ~2.75 Å in radius, which is significantly smaller than that of the P-M benchmark (i.e., 3.38 Å). Further analyses of the interior cavity radius disclose a narrower distribution of pore sizes within DP-M (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 26), signifying the compact structure of the PA layer mediated by DAT-NH2 (Fig. 1c). Notably, the microscopic pore features derived from molecular simulations coincide well with those experimentally obtained from neutral solute rejection tests (Fig. 2g, i). The tight nanostructure of DP-M constricts membrane pores to dimensions more favorable for size sieving, with precise ionic and molecular sieving capabilities and a threshold of 5.6 Å in pore diameter. Furthermore, aligning with the chemical features of the CTHP structures in DP-M (Fig. 1g), the cationic DAT-NH2 moieties elevate the membrane hydrophilicity and positive charge density, as manifested by its smaller surface water contact angle (CA) and higher zeta potential (ZP) than that of the P-M benchmark (Supplementary Fig. 25 and Fig. 2j). In the realm of NF applications, the enhanced hydrophilicity facilitates surface partitioning and interior diffusion of water molecules, whereas the ameliorated positive charge density reinforces the electrostatic repulsion selectivity. Collectively, the advanced characteristics gained by the DP-M membrane resonate with our intended design strategy illustrated in Fig. 1b, which underpins the significance of synthetic molecular engineering in precisely regulating the nanoporous structure and chemical features of the PA selective layer (Fig. 2k).

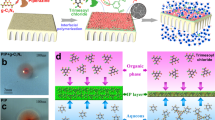

Simultaneous improvement in water permeance and co-cation sieving selectivity

The well-defined subnanometer pores with a sharped size distribution and the inherent positive charges of the DP-M membrane would afford prominent molecular sieving and electrostatic repulsion selectivity in NF applications. We subsequently examined the mass transport behavior of a wide spectrum of inorganic salts through DP-M using a crossflow filtration system. In contrast to the acquiescent expectation that a decrease in membrane pore size along with a downscaled FFVs generally accompanied by a concomitant decline in the water permeation rate, a substantial increase in the water permeance was achieved by DP-M, where the water permeation flux of DP-M is almost tripled at the same pressure compared to the P-M benchmark (Fig. 3a), corresponding to an approximately 3-fold increase in pure water permeance (PWP). The incongruence between the enhanced water permeance and the reduced pore sizes and FFVs likely stems from the molecularly constructed CTHP structures and the low thickness of the PA layer, which provide facilitated water transport pathways with low resistance.

a Pure water flux (PWF) of DP-M and P-M at different operation pressures. b Water flux and ion rejections of DP-M for filtrating different cation solutions. (Feed salt concentration: 1000 ppm; test pressure: 6.0 bar). c MgSO4 and MgCl2 rejections of P-M and DP-M (feed salt concentration: 1000 ppm, test pressure: 6.0 bar). d Effect of operation pressure on the water permeance and MgCl2 rejection of DP-M (feed: 1000 ppm MgCl2). e Effect of pH on the water flux and LiCl rejection of DP-M (feed: 1000 ppm LiCl, test pressure: 6.0 bar). f Effect of operation time on the water flux and MgCl2 rejection of DP-M (feed: 1000 ppm MgCl2, test pressure: 6.0 bar). g Effect of operation pressure on the water permeance and SLi+/Mg2+ of DP-M (feed: 2000 ppm binary mixture of MgCl2 and LiCl with a MgCl2/LiCl mass ratio of 20). h Effects of the Mg2+/Li+ ratio on the water flux and SLi+/Mg2+ ratio of DP-M (feed: 2000 ppm binary mixture of MgCl2 and LiCl with various MgCl2/LiCl mass ratios; test pressure: 6.0 bar). i Performance comparison of DP-M with state-of-the-art PA NF membranes operated under cross-flow nanofiltration. The corresponding references for the data points in (i) are specified in Supplementary Table 4.

At the same time, DP-M shows a sharp size-exclusion cutoff of ~2.5 Å in the Stokes radius of cations (Fig. 3b), adhering to its densified catatonic PA molecular structure, which thereby facilitates the transport of smaller monovalent cations (i.e., Rb+, K+, Na+, and Li+) while sufficiently blocks larger divalent cations (i.e., Ni2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+), with rejection rates greater than 98.0% and high water flux of 50 L m−2 h−1 (LMH). It is noteworthy that ultrahigh rejections of up to 99.1% towards MgCl2 and MgSO4 were specifically achieved by DP-M (Fig. 3c), exceeding most state-of-the-art NF membranes, and similar rejections and water permeance were maintained over a wide pressure range of 2–16 bar (Fig. 3d). In contrast, LiCl rejection monolithically increased from 45.7% to 81.2% when the pressure was raised from 2 to 16 bar (Supplementary Fig. 27). As a result, an ideal Li+/Mg2+ selectivity of 35.8–42.9 was obtained based on single salt rejections (Supplementary Fig. 28), demonstrating its promising capability for precise cation sieving. In the same vein, the P-M benchmark is inferior in terms of both salt rejection and cation differentiation selectivity (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 29).

The separation performances of conventional NF membranes are generally susceptible to the feed salt concentration and pH due to the electrostatic screening effects. Interestingly, DP-M consistently retains its water flux, salt rejection, and co-cation selectivity across a wide range of feed salt contents and pH values. As demonstrated by the cycling performance tests, the Mg2+ rejection of the DP-M membrane decreased slightly from 99.1% to 95.7% while the Li+ rejection dropped from 59.8% to 23.3% as the feed salt content spanned from 1000 to 7000 mg/L, while the rejections were almost fully recovered to the initial values when the feed content was switched back to 1000 mg/L (Supplementary Fig. 30), substantiating good electrostatic shielding resistance toward high ionic strength. There were also no obvious deteriorations in salt rejections and water flux as the feed pH escalated from 1 to 13 (Fig. 3e), underscoring the ability of DP-M to maintain high separation performance in both acidic and alkaline environments. The exceptional pH and salinity stabilities of DP-M are consistent with the inherent structural features of CTHP and the enhanced size-sieving ability endowed by the narrow pore size distribution (Fig. 2g, i). The exceptional hydrophilicity and positive surface charge imparted by the catatonic CTHP structures also affords DP-M with exceptional fouling resistance to positively charged foulants (i.e., DTAB, dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide) (Supplementary Fig. 31). Moreover, DP-M shows exceptional structural durability and performance stability throughout long-term filtration for 120 h (Fig. 3f), where MgCl2 rejection consistently surpassed 99%, with a stable water flux of ~51 LMH being retained. Notably, the DP-M membrane maintained a high MgCl2 rejection of above 99% and a water flux of greater than 50 LMH even after being stored in water for one month (Supplementary Fig. 32). In addition, the DP-M membrane exhibits exceptional chlorine resistance. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 33, relatively stable MgCl2 rejections and water flux were observed throughout the 175 h exposure to 200 ppm sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), while the MgCl2 rejection of the P-M benchmark decreased dramatically from 92.4% to 29.5% with a concomitant rapid increase in water flux from 20.4 to 149.3 LMH. FT-IR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 33c, d) further reveals that the characteristic peak of the amide bond (~1660 cm−1) in P-M substantially decreased with the extension of exposure time, whereas the counterpart peak in the DP-M membrane remained nearly unchanged, demonstrating the exceptional structural durability of the DP-M membrane under oxidative conditions.

The co-cation sieving ability of DP-M was further illuminated by binary salt filtration tests using a mixture of LiCl and MgCl2 as the probe solutes. Similar to the single-salt tests (Supplementary Fig. 28), DP-M shows high Li+/Mg2+ selectivity with a separation factor of greater than 39.0 (SLi+/Mg2+) for the binary mixtures at different operation pressures (Fig. 3g), which signifies a 9-fold greater magnitude than that achieved by the P-M benchmark (SLi+/Mg2+ = 4.3), accompanied by an approximately 2.5-fold increase in water permeance. The persistently high rejections toward divalent cations and co-cation selectivity are presumably ascribed to the advanced molecular sieving and electrostatic repulsion effects afforded by the regulated subnanometer pores and inherent positive charges of DP-M. Furthermore, slight fluctuations in the co-cation selectivity were observed when the feed Mg2+/Li+ mass ratio altered from 1 to 120, where the SLi+/Mg2+ oscillated between 33.5 and 44.3 and the water flux was consistently higher than 51.4 LMH (Fig. 3h). Compared with other reported PA NF membranes with similar chemical and structural properties, DM-P exhibits upper-level water permeance and co-cation sieving selectivity (i.e., Li+/Mg2+) (Fig. 3i), which potentially contributes to a more streamlined separation process with diminished energy consumption (Supplementary Fig. 34), underscoring its remarkable potential for energy-efficient and cost-effective NF separations. To validate the uniformity and scalability of the developed PA membranes, a large-sized DP-M membrane (1×0.3 m) was fabricated via the same interfacial polymerization (Supplementary Fig. 35). Membrane coupons randomly selected from different regions exhibited consistent performance, with the MgCl2 rejection rate stably maintained at 98% while the water flux remained around 50 LMH, indicating the exceptional scalability and stability. Furthermore, the generality of NF performance enhancement by triazole derivatives was demonstrated by extending to other quaternary ammonium triazole analogs (i.e., 3,5-diamino-4/1-(3-aminopropyl)–1,2,4-triazole, DAAT-NH2) and benchmarking against non-triazole monomers (Supplementary Fig. 36 and Fig. 37). The successful breakthrough of the permeance/selectivity tradeoff underpins our membrane design strategy and exemplifies the feasibility of synthetic molecular engineering in rational membrane design.

Regulatory mechanisms of enhanced co-cation selectivity and facilitated water permeation

Given that the DP-M membrane possesses strong intrinsic positive charges and an average micropore diameter of 5.6 Å with narrow size distribution (i.e., from 1.1 to 5.9 Å) (Fig. 2g), we hypothesize that its high rejections toward divalent cations and enhanced co-cation sieving ability lean upon the on-demand tuning of the PA chemistry and nanoporous structure according to the size and valence differences between cations, which instigates unusual differences in energy barriers that cations need to overcome for dissolution and migration. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the average pore size of DP-M (5.6 Å) falls between the Stokes diameter (4.8 Å) and hydrated diameter (7.6 Å) of Li+. Given the substantial difference in hydration energy between Mg2+ and Li+ (1828 vs. 474 kJ/mol), Li+ ions are more susceptible to undergo partial dehydration and subsequent selective permeation through the well-defined micropores of DP-M, enabling effective discrimination between Li+ and Mg2+ cations. This energy discrepancy is further corroborated by DFT calculations (Supplementary Fig. 38), which estimate the hydration energies of Mg2+ and Li+ to be −1922.45 and −563.52 kJ/mol, respectively, indicating that the hydrated Mg2+ encounters a significantly higher energy barrier than Li+ to dehydrate at identical transmembrane pressure.

a Pore size distributions of P-M and DP-M membranes and the sizes of Li+ and Mg2+ cations. Schematic illustration of transmembrane transport of hydrated Li+ and Mg2+ through the subnanometer pores in DP-M. b Analysis of the binding configurations between P-M/DP-M molecular fragments and hydrated Li+ and Mg2+ using the independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition (IGMH). c, d Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermogram derived crystallization and melting behavior of the DP-M membrane after being equilibrated with 1000 ppm c MgCl2 and (d) LiCl aqueous solutions. The lower right inset shows the melting enthalpy (ΔHm), crystallization enthalpy (ΔHc), and their difference (ΔHm−c). e The binding energies between the hydrated Li+/Mg2+ and the PA molecular fragments of P-M/DP-M. The numbers represent the calculated energy gaps between Li+ and Mg2+ in P-M and DP-M. f Interaction region indicator analysis of the PA fragments interacting with Mg2+. The effects of the hydration layer and TMC were shielded (the arb. units here represents energy, and 1 arb. units is approximately 27.21 eV). g Interaction region indicator analysis of the PA fragments derived from DAT-NH2 and the visualized structure diagram. h van der Waals surface area ratio corresponding to various electrostatic potential intervals of the PA molecular fragments.

To gain fundamental insights into the influences of the pore environment on cation dehydration behavior, dynamic molecular simulations were performed to examine the interactions between PA fragments and hydrated Li+ and Mg2+ ions (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 39). Compared with P-M, the independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partitioning (IGMH) analysis shows that DP-M has weaker hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions with water molecules in the hydration shell of Mg2+ ions, which is unfavorable for stabilizing the configuration. In addition, the lower intrinsic charge number of Li+ relative to Mg2+ leads to the weaker binding energy of its hydration layer (Supplementary Fig. 40), while the positively charged CTHP structures in DP-M further promote the escape of polar water molecules from the Li+ hydration shell by exerting extensive van der Waals and hydrogen bonding interactions, as demonstrated in the DP-M/hydrated Li+ configuration (Fig. 4b), thereby aggrandizing the dehydration of Li+ during transmembrane permeation. These effects of promoting Li+ dehydration expedite its transport through DP-M, which plays an important role in enhancing Li+/Mg2+ selectivity, especially when the membrane pore sizes are diminished and the size distribution is constricted. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were also performed to experimentally explore the hydration/dehydration behavior of Li+ and Mg2+ within the polyamide polymer matrix. As shown in Fig. 4c, d, the obtained crystallization enthalpy reveals that Mg2+ (ΔHc = −303.0 J/g) tends to form a more structured and strongly bound hydration shell within the polyamide matrix of DP-M compared to Li+ (ΔHc = −188.2 J/g). Furthermore, the melting enthalpy (ΔHm, 314.8 vs. 237.8 J/g) indicates that Mg2+ is more likely to establish stable coordination interactions with the functional groups and chemical bonds of the polyamide network, thereby requiring greater energy to disrupt the hydration structure. These thermodynamic distinctions disclose the underlying rationale for the enhanced Li+/Mg2+ selectivity of the DP-M membrane, which is in good agreement with the modeling results. Contrarily, for the P-M benchmark (Supplementary Fig. 41), the melting (ΔHm = 338.9 vs. 357.4 J/g) and crystallization (ΔHc = −303.0 vs. −320.3 J/g) enthalpies associated with hydrated Mg2+ and Li+ are comparable, indicating that the P-M benchmark lacks the thermodynamic ability to discriminate between hydrated Mg2+ and Li+, which sheds light on its low Li+/Mg2+ selectivity.

DFT calculations were further performed to illuminate the mutual interactions between PA and cations by performing configuration optimization and cation–PA binding energy calculations (Supplementary Table 5). As displayed in Supplementary Fig. 42, the negative binding energies of hexahydrated Mg2+ with the DP-M PA fragments are consistently lower than those with the P-M fragments, suggesting that the binding interactions between Mg2+ and P-M are relatively more stable. On the contrary, the similar binding energies of hydrated Li+ to DP-M and P-M PA fragments (–28.83 vs. –29.65 kcal/mol) acknowledge that the transport of hydrated Li+ through the two membranes is subjected to similar energetic penalties despite the diminished and narrowed pore sizes of the former (Fig. 4e). However, the binding energy gaps between Li+ and Mg2+ in the DP-M fragments are 16.80 and 9.90 kcal/mol, respectively, which are markedly larger than those in the P-M fragments (i.e., 2.82 and 6.66 kcal/mol) (Fig. 4e), implying that DP-M has an overwhelming advantage over P-M to differentiate Li+ and Mg2+ from the energy perspective. The interaction region indicator (IRI) was subsequently applied to conduct an in-depth analysis of the specific types of interactions between the PA fragments and hexahydrated Mg2+41 (Supplementary Fig. 43). The corresponding scatter plots reveal that the interaction forces involved are intricate and hard to distinguish (Supplementary Fig. 44). Therefore, the hydration layer of Mg2+ and the influence of TMC were shielded to better disclose the contributions of DAT-NH2 moieties in the PA (Fig. 4f). Examining their respective IRI scatter plots, eminent peaks appear near sign(l2)r values of −0.05 and 0.06 arb. units in the DP-M PA molecular fragments. From the electron density point of view, the peak at −0.05 arb. units corresponds to a weak interaction of higher strength, whereas the peak at 0.06 arb. units stems from a stronger spatial repulsion. Notably, the scatter plot of the weak interaction portion ascertains an anomalous peak at approximately 0.013 arb. units in DP-M (Supplementary Fig. 45), which indicates that the CTHP structures derived from DAT-NH2 may generate proprietary steric hindrance at the molecular level. The two distinct peaks in the scatter plot obtained from interaction decomposition confirm that CTHP instigates both attractive and repulsive interactions (Fig. 4g). Further analysis of the IRI visualized isosurface shows that the peak near −0.05 arb. units is attributed to intramolecular H-bonding interactions. These H-bonds account for the in situ formation of the cyclic conformations in the CTHP structures (Fig. 4g), which dictate additional steric hindrance at approximately 0.013 arb. units (the peak near 0.013 is retained in Supplementary Fig. 46). Moreover, the peak at approximately 0.06 arb. units is associated with the strong repulsion induced by the overlapping of the triazole rings in CTHP driven by van der Waals surfaces. Other than the narrowed subnanometer pore sizes, these anomalous intramolecular H-bonding structures provide additional steric hindrance at the molecular level, further amplifying the permeation energy barrier acting on divalent cations.

In addition to the non-Coulombic interactions, long-range Coulombic electrostatic forces (i.e., Donnan exclusion) also play an imperative role in the cation–PA interactions, particularly considering the strongly charged PA structure of DP-M. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of the electrostatic potential (ESP) were conducted to acquire the van der Waals surface ESP distributions of the PA molecular fragments of DP-M and P-M. As illustrated in Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 47–48, DP-M exhibits a exceptional positive potential and this observation was reaffirmed by the quantitative calculation of the ESP region proportions, where DP-M shows a large positive potential region proportion of 97% and an average ESP value of 55.55 kcal/mol, far exceeding the respective value of P-M. The pronounced electrostatic repulsion between DP-M and the positively charged hexahydrated cations is unequivocally conferred by the CTHP structures of the PA layer. The ESP of hydrated Mg2+ is nearly twice as high as that of hydrated Li+ (193.29 vs. 98.53 kcal/mol, Supplementary Fig. 40), which inevitably invokes formidable Donnan exclusion selectivity towards the positively charged DP-M (55.55 kcal/mol). Overall, the intriguing co-cation sieving ability of DP-M proceeds through a cooperative mechanism of steric hindrance and electrostatic exclusion, as corroborated by comprehensive modeling and experimental characterization.

Water molecules need to overcome certain energy barriers when dissolving and diffusing through the PA membrane, which is primarily governed by the chemical features and nanoporous structure of the PA selective layer (Fig. 5a). The mutual interactions of water molecules with the binding sites on the PA network thereby have substantial impacts on water permeation rate. To gain a fundamental understanding of the mechanisms governing the facilitated permeation of water through the DP-M membrane, DFT atomistic calculations and MD simulations were performed. DFT was employed to specifically evaluate the molecular interactions between water and the cationic DP-M PA fragments by calculating the surface free energy (SFE, Supplementary Table 6) and the molecular polarity index (MPI), which reflect membrane hydrophilicity from the perspectives of interfacial thermodynamics and quantum chemistry. As displayed in Fig. 5b, DP-M shows a higher MPI value than that of P-M (i.e., 56.0 vs. 19.7), which is consistent with the lower surface water contact angle of the former. Meanwhile, the SFE value of DP-M is greater than that of P-M (i.e., 50.5 vs. 41.4 kJ/m2), indicating a clear preference of polar water molecules for wetting and partitioning into the PA fragments of DP-M (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 6). To further elucidate the diffusion behavior of water molecules within the PA layer, MD simulations were subsequently conducted to acquire the molecular-level binding affinities of water cluster to the PA fragments (Fig. 5d). The radial distribution functions (RDFs) plots with respect to the PA fragments labeled in green (I), blue (II), and orange (III) reveal that the peak of I-H2O in the first coordination layer is significantly higher than those of II-H2O and III-H2O (Fig. 5e), closely aligned with the DFT calculations and experimental data. Furthermore, the water bonding (WB) capacity calculated by RDFs follows an order of WBI > WBII > WBIII, while the computed binding energies (BE) of fragments I, II, and III with water are in the order of |BEI | > |BEII | > |BEIII | (Fig. 5f). Hereupon, the cationic triazolyl heterocyclic PA structures derived from DAT-NH2 in DP-M have a relatively lower affinity to water clusters. Such energy metrics accentuate a thermodynamic inclination of DP-M to facilitate the transport of water by providing favorable water binding sites with moderate resistance, aligned with our design strategy and the ideal PA nanostructure we intend to construct (Fig. 5g).

a Schematic representation of the advanced structure of an ultrapermeable PA membrane with precise co-cation sieving capability. b DFT atomistic calculations of polarity differences between DP-M and P-M molecular fragments. c ESP distributions of van der Waals surfaces of the water molecules obtained by DFT calculations. d Three representative PA molecular fragments of DP-M and P-M (left) and the schematic illustration of water cluster distribution in each fragment (right). e The radial distribution functions (RDFs) between water and the three PA fragments. f Binding energy (BE) and the number of water molecules (NW) around the three PA fragments. All the information and data described in (d–f) were obtained from MD simulations. g Schematic illustration of the working principle of the semipermeable DP-M for ultrafast co-cation nanofiltration (yellow and blue spheres represent monovalent and divalent cations, respectively).

Discussion

Advanced nanofiltration membranes with exceptional permselectivity offer promising solutions to address pressing challenges associated with water scarcity and renewable energy. This study demonstrates a feasible molecular engineering strategy to reconcile the tradeoff between water permeance and selectivity in state-of-the-art PA nanofiltration membranes for ultrafast co-cation sieving. Our approach is contingent on the fine-tuned regulation of the porous nanostructure and the mutual interactions of the PA layer with water molecules and ions by molecular construction of cationic triazolyl heterocyclic polyamide (CTHP) structures via in situ interfacial polymerization using synthetic DTA-NH2 isomers. The obtained PA membranes exhibited simultaneously enhanced water permeance and selectivity for cation separation, achieving high divalent cation rejections of over 99%, accompanied by a 9-fold increase in monovalent/divalent cation sieving selectivity and tripled water permeance in comparison with the pristine benchmark, as well as outstanding chemical stability and fouling resistance. Experimental data in conjunction with molecular simulations confirm that the intriguing permselectivity springs from the advanced molecular structures of the CTHP-modulated PA layer, which not only investigates a substantial decrease in the membrane pore size and narrows the size distribution but also affords high positive charge density and polarity. Coincidentally, the CTHP structures also provide preferential water binding sites with low energy barriers, energetically facilitating the accommodation and diffusion of water molecules within the PA layer, which eliminates the increased water transport resistance caused by pore size shrinkage. The developed synthetic engineering strategy sheds light on the rational design and fabrication of high-performance polymer membranes for precision NF separations affiliated with water‒energy nexuses.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Polyethyleneimine (PEI, MW = 70000 Da, 50 wt% aqueous solutions), trimesoyl chloride (TMC, 98.0%), 1,2,4-triaminobenzene (95%), 3-bromopropylamine (97%), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 99.0%) ordered from Macklin (Shanghai, China) were used to synthesize the polyamide benchmark membrane via interfacial polymerization. Hexane (99.0%) purchased from Macklin was used as the solvent for the TMC monomer. 3,5-Diamino-1,2,4-triazole (DAT, 98%), 2-bromoethylamine (98%), acetonitrile (99%), and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 98%) were obtained from Macklin for the synthesis and purification of DAT-NH2 isomers. Ethylene glycol (62 Da), diethylene glycol (106 Da), glucose (180 Da), and polyethylene glycols of different molecular weights (i.e., PEG200, PEG400, PEG600, and PEG1000) were provided by Aladdin (Tianjin, China) for membrane pore size characterization. Sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), lithium sulfate (Li2SO4), magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), lithium chloride (LiCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), rubidium chloride (RbCl), potassium chloride (KCl), nickel chloride (NiCl2), calcium chloride (CaCl2), and zinc chloride (ZnCl2) were obtained from Macklin for salt rejection tests. Dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) used in the fouling study was purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99.9%) was supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR) was purchased from Fuchen (Tianjin) Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals and reagents were used as received without further purification. Polyether sulfone (PES) ultrafiltration membrane with a molecular weight cutoff of 20–30 kDa from Weihua Technology Co., Ltd., China was used as the substrate for preparing the polyamide membranes for nanofiltration tests. Deionized water was supplied by a Millipore-D 24 UV ultrapure water integrated system (Millipore Instruments, 18.2 MΩ cm).

Synthesis of DAT-NH2 isomers

3,5-Diamino-4/1-(2-aminoethyl)−1,2,4-triazole (DAT-NH2) isomers were synthesized via a one-step quaternization reaction following the reaction path shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. In a typical synthesis, 4.24 g of 3,5-diamino-1,2,4-triazole (DAT, 42.8 mmol) and 8.77 g of 2-bromoethylamine (42.8 mmol) were dissolved in 90 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) in a 150 mL round-bottom flask. The flask with the reaction mixture was then heated to 45 °C in a water bath and reacted at this temperature for 24 h under vigorous stirring. A pale green solution rapidly formed with increasing reaction time. When the reaction was complete, the resulting mixture was immediately transferred into a 500 mL beaker, and 180 mL of acetonitrile was then added to obtain a milky white suspension. The obtained flocculent precipitates were subsequently redissolved in 10 mL of DMF and then precipitated with 180 mL of acetonitrile. The white solids were collected via high-speed centrifugation. The above dissolution and precipitation treatment was repeated three times. Finally, the as-synthesized DAT-NH2 was vacuum dried at 40 °C overnight and then stored in a sealed container for subsequent characterization and membrane fabrication.

Preparation of PA NF membranes

For the fabrication of the PA thin-film composite NF membrane, the polyether sulfone (PES) substrate was first immersed in an amine monomer aqueous solution with 0.1 wt% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 0.1 wt% Na2CO3 for 5 min. After the excess water on the top surface was removed via filter paper, the amine-monomer saturated PES substrate was sandwiched into a homemade frame with the top surface facing upward. Interfacial polymerization was initiated by carefully adding excessive 0.3 wt% trimesoyl chloride (TMC) solution into the frame to cover the surface, which was allowed to react for 1 min. When the reaction was complete, the excess hexane solution was drained, and the resulting membrane was dried at 60 °C for 30 min. Specifically, DP-M represents a PA membrane that was prepared following the above synthesis procedure using a mixture of DAT-NH2 (0.06 wt%) and polyethyleneimine (PEI) (0.44 wt%) as the amine monomer. The P-M benchmark membrane was fabricated solely by using PEI as the amine monomer. All the as-synthesized PA membranes were stored in deionized water at 5 °C for further characterization and performance tests. The detailed preparation process of the PA nanofilm is included in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Note 1). Two model membranes were prepared by replacing DAT-NH2 with 3,5-diamino-4/1-(3-aminopropyl)−1,2,4-triazole (DAAT-NH2) and 1,2,4-triaminobenzene, respectively, under identical interfacial polymerization conditions. Large-sized DP-M membranes (1×0.3 m) were fabricated using a custom-made interfacial polymerization apparatus under the same reaction conditions as the laboratory-scale preparation.

Characterization

The successful synthesis of DAT-NH2 isomers was confirmed by mass spectrometry (MS, MSQ Plus, USA) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Ultimate 3000 RS, USA). The chemical structure of DAT-NH2 was characterized by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy (Bruker AVANCE AV400, USA). The chemical features of the PA membranes were also analyzed via Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR, Nicolet IN10, Thermo Fisher, USA) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Escalab 250Xi, Thermo Fisher, USA). The membrane surface morphology and roughness were examined via field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Quanta 250 FEG, FEI, USA) and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Nano Wizard 4, Bruker, Germany). The membrane cross-sectional morphology was identified via high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F30, FEI, USA). Surface hydrophilicity was assessed via water contact angle measurements on a contact angle goniometer (HARKE-SPCA, HARKE, China). The surface zeta potential was measured via a SurPASS electrokinetic analyzer (Anton Paar, GmbH, Austria). The molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) and pore size distribution of the membrane were obtained via solute retention tests using polyethylene glycol (PEG) probes with different molecular weights. The thermal behavior related to the hydration state of the ions within the membrane matrix was characterized using a TA Q2000 differential scanning calorimeter (TA Instruments, USA). The detailed procedures for each measurement are included in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Notes 2–3).

Nanofiltration performance tests

The separation performance of the PA membranes was characterized in nanofiltration mode at 23 °C via a cross-flow filtration apparatus with an effective membrane filtration area of 6.0 cm2. Before data collection, the membrane sample was conditioned at a pressure of 2 bar greater than the intended test pressure until the water flux stabilized. The pure water flux (Jw, L m−2 h−1, abbreviated as LMH) was measured using deionized water as the feed, and the water permeance (A, LMH/bar) was calculated via Eq. (1).

where ∆P (bar) is the trans-membrane hydraulic pressure, ∆V (L) is the volume of permeate water collected during a time interval of ∆t (h), and S (m2) is the effective membrane filtration area.

The membrane ion sieving ability was examined via rejection tests that were conducted under various conditions using a wide spectrum of inorganic salts as solutes. Specifically, Na2SO4, Li2SO4, MgSO4, MgCl2, LiCl, NaCl, RbCl, KCl, NiCl2, CaCl2, and ZnCl2 solutions with different concentrations and compositions were used as the feed. The single salt rejection (R, %) was calculated via Eq. (2).

where Cp and Cf are the salt contents of the permeate and feed, respectively. The salt concentration was determined via conductivity measurement via a SevenCompact™ S230 (Mettler Toledo) conductivity meter. Binary mixtures of MgCl2 and LiCl with different mass ratios were used to evaluate the membrane selectivity for co-cation fractionation. The Li+/Mg2+ separation factor (SLi+/Mg2+) was calculated via Eq. (3).

where Cf Mg2+ and Cf Li+ and where Cp Mg2+ and Cp Li+ represent the concentrations of Mg2+ and Li+ in the feed and permeate, respectively. An inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP‒OES, iCAP 7000, Germany) was used to quantify the ion contents of the solution. Each data point was tested three times under the same conditions using randomly selected membrane samples, and the average value was reported.

The long-term stability of the membrane was evaluated by monitoring the water flux and salt rejection for up to 120 h at 6 bar using 1000 ppm MgCl2 solution as the feed. The pH stability of the membrane was assessed by measuring the water flux and salt rejection in a feed pH range of 1 − 13 using 1000 ppm LiCl solution as the probe feed, during which the solution pH was adjusted via HCl and NaOH. The concentrations of the single salt solution and binary mixed solution (MgCl2/LiCl mass ratio of 20) involved in the experiment were 1000 and 2000 ppm, respectively. All nanofiltration tests were performed at room temperature (25 °C), and no additional pH adjustment was made to the feed except for the pH influence tests. The chlorine resistance of the membrane was evaluated by immersing the membrane samples in aqueous sodium hypochlorite solution (NaClO, 200 ppm, pH = 6) under continuous stirring. To ensure that the chlorine concentration remained consistent throughout the exposure period, the NaClO solution was replaced every 24 h. After a specified exposure duration, the membranes were thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to eliminate residual chemicals and then subjected to nanofiltration performance tests. The chlorine tolerance was assessed by measuring the MgCl2 rejection and water flux using a 1000 ppm MgCl2 solution as the probe feed under a transmembrane pressure of 6 bar. Antifouling performance was evaluated using a cross-flow filtration system at 6 bar. A baseline water flux was recorded over 2 h using a 1000 ppm MgCl2 solution as feed. The membrane was then exposed to 200 ppm DTAB in a 1000 ppm MgCl2 solution for 8 h to monitor flux degradation. After three 10-minute deionized water rinse cycles, the recovered flux was evaluated using a 1000 ppm MgCl2 solution for 2 h.

Molecular modelling

Density functional theory (DFT) atomistic calculations were conducted via ORCA quantum chemistry software (version 5.0.4)42,43,44. The binding energy and ion hydration energy were obtained via single-point energy calculations. Electrostatic potential (ESP)45,46, average local ionization energy (ALIE)47, interaction region indicator (IRI)41, independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition (IGMH)48, and molecular polarity index (MPI)49 analyses were performed with the Multiwfn software package to gain insights into molecular electronic properties and interaction patterns50. LAMMPS and GROMACS were employed for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations51,52, where LAMMPS was used to calculate the free volume fraction of the PA nanofilm, whereas GROMACS was applied to analyze the distribution and binding energy of water molecules around specific PA molecular segments. These simulations enabled a detailed exploration of water‒PA interactions, which is crucial for understanding the hydration behavior and separation performance of the membrane. Comprehensive details of the computational methods and protocols are provided in Supplementary Note 4 and Note 5.

Data availability

All relevant data in the main text or the supplementary materials are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, F., Fan, J.-b & Wang, S. Interfacial Polymerization: From Chemistry to Functional Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21840–21856 (2020).

Lu, X. & Elimelech, M. Fabrication of desalination membranes by interfacial polymerization: history, current efforts, and future directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 6290–6307 (2021).

Epsztein, R., DuChanois, R. M., Ritt, C. L., Noy, A. & Elimelech, M. Towards single-species selectivity of membranes with subnanometre pores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 426–436 (2020).

Wang, K. et al. Tailored design of nanofiltration membranes for water treatment based on synthesis–property–performance relationships. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 672–719 (2022).

Sengupta, B. et al. Carbon-doped metal oxide interfacial nanofilms for ultrafast and precise separation of molecules. Science 381, 1098–1104 (2023).

Lu, C. et al. Dehydration-enhanced ion-pore interactions dominate anion transport and selectivity in nanochannels. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf8412 (2023).

Ji, Y. et al. Electric field-assisted nanofiltration for PFOA removal with exceptional flux, selectivity, and destruction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 18519–18528 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ice-confined synthesis of highly ionized 3D-quasilayered polyamide nanofiltration membranes. Science 382, 202–206 (2023).

Freger, V. & Ramon, G. Z. Polyamide desalination membranes: formation, structure, and properties. Prog. Polym. Sci. 122, 101451 (2021).

Tan, Z., Chen, S., Peng, X., Zhang, L. & Gao, C. Polyamide membranes with nanoscale Turing structures for water purification. Science 360, 518–521 (2018).

Zhao, G.-J. et al. Polyamide nanofilms through a non-isothermal-controlled interfacial polymerization. Adv. Funct. Mater. n/a, 2313026 (2024).

Geise, G. M. Why polyamide reverse-osmosis membranes work so well. Science 371, 31–32 (2021).

Lopez, K. P., Wang, R., Hjelvik, E. A., Lin, S. & Straub, A. P. Toward a universal framework for evaluating transport resistances and driving forces in membrane-based desalination processes. Sci. Adv. 9, eade0413 (2023).

Culp, T. E. et al. Nanoscale control of internal inhomogeneity enhances water transport in desalination membranes. Science 371, 72–75 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Manipulating interfacial polymerization for polymeric nanofilms of composite separation membranes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 122, 101450 (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Intrapore energy barriers govern ion transport and selectivity of desalination membranes. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd9045 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Interfacial polymerization at the alkane/ionic liquid interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 14757–14764 (2021).

Raaijmakers, M. J. T. & Benes, N. E. Current trends in interfacial polymerization chemistry. Prog. Polym. Sci. 63, 86–142 (2016).

Shen, L. et al. Polyamide-based membranes with structural homogeneity for ultrafast molecular sieving. Nat. Commun. 13, 500 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Polycage membranes for precise molecular separation and catalysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 3112 (2023).

Yuan, B. et al. Self-assembled dendrimer polyamide nanofilms with enhanced effective pore area for ion separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 471 (2024).

Zhao, G., Gao, H., Qu, Z., Fan, H. & Meng, H. Anhydrous interfacial polymerization of sub-1 Å sieving polyamide membrane. Nat. Commun. 14, 7624 (2023).

Chen, W., Liu, M., Ding, M., Zhang, L. & Dai, S. Advanced thin-film composite polyamide membrane for precise trace short-chain PFAS sieving: Solution, environment and fouling effects. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 169, 493–503 (2023).

Dai, R. et al. Nanovehicle-assisted monomer shuttling enables highly permeable and selective nanofiltration membranes for water purification. Nat. Water 1, 281–290 (2023).

Peng, H. & Zhao, Q. A nano-heterogeneous membrane for efficient separation of lithium from high magnesium/lithium ratio brine. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2009430 (2021).

Hong, S. et al. Precision ion separation via self-assembled channels. Nat. Commun. 15, 3160 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Solar-driven membrane separation for direct lithium extraction from artificial salt-lake brine. Nat. Commun. 15, 238 (2024).

Zhou, Z. et al. Electrochemical-repaired porous graphene membranes for precise ion-ion separation. Nat. Commun. 15, 4006 (2024).

Peng, H., Liu, X., Su, Y., Li, J. & Zhao, Q. Advanced lithium extraction membranes derived from tagged-modification of polyamide networks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312795 (2023).

Peng, H., Su, Y., Liu, X., Li, J. & Zhao, Q. Designing gemini-electrolytes for scalable Mg2+/Li+ separation membranes and modules. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305815 (2023).

Guo, B.-B. et al. Double charge flips of polyamide membrane by ionic liquid-decoupled bulk and interfacial diffusion for on-demand nanofiltration. Nat. Commun. 15, 2282 (2024).

Shefer, I., Peer-Haim, O. & Epsztein, R. Limited ion-ion selectivity of salt-rejecting membranes due to enthalpy-entropy compensation. Desalination 541, 116041 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Simultaneous manipulation of membrane enthalpy and entropy barriers towards superior ion separations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408963 (2024).

Freger, V. Nanoscale heterogeneity of polyamide membranes formed by interfacial polymerization. Langmuir 19, 4791–4797 (2003).

Muscatello, J., Müller, E. A., Mostofi, A. A. & Sutton, A. P. Multiscale molecular simulations of the formation and structure of polyamide membranes created by interfacial polymerization. J. Membr. Sci. 527, 180–190 (2017).

Zhu, Q.-Y. et al. Can the mix-charged NF membrane directly obtained by the interfacial polymerization of PIP and TMC? Desalination 558, 116623 (2023).

Zhang, M. et al. Modulating interfacial polymerization with phytate as aqueous-phase additive for highly-permselective nanofiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 657, 120673 (2022).

Karan, S., Jiang, Z. & Livingston, A. G. Sub–10 nm polyamide nanofilms with ultrafast solvent transport for molecular separation. Science 348, 1347–1351 (2015).

Košutić, K., Dolar, D., Ašperger, D. & Kunst, B. Removal of antibiotics from a model wastewater by RO/NF membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 53, 244–249 (2007).

Sarkar, P., Ray, S., Sutariya, B., Chaudhari, J. C. & Karan, S. Precise separation of small neutral solutes with mixed-diamine-based nanofiltration membranes and the impact of solvent activation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 279, 119692 (2021).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Interaction region indicator: a simple real space function clearly revealing both chemical bonds and weak interactions**. Chem. Methods 1, 231–239 (2021).

Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Becker, U. & Riplinger, C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 224108 (2020).

Stoychev, G. L., Auer, A. A. & Neese, F. Automatic generation of auxiliary basis sets. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 554–562 (2017).

Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. WIREs Computational Mol. Sci. 12, e1606 (2022).

Manzetti, S. & Lu, T. The geometry and electronic structure of aristolochic acid: possible implications for a frozen resonance. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 26, 473–483 (2013).

Lu, T. & Manzetti, S. Wavefunction and reactivity study of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide and its enantiomeric forms. Struct. Chem. 25, 1521–1533 (2014).

Zhang, J. & Lu, T. Efficient evaluation of electrostatic potential with computerized optimized code. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 20323–20328 (2021).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: a new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 43, 539–555 (2022).

Liu, Z., Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Intermolecular interaction characteristics of the all-carboatomic ring, cyclo[18]carbon: focusing on molecular adsorption and stacking. Carbon 171, 514–523 (2021).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Hess, B., Kutzner, C., van der Spoel, D. & Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22125603 & 92475205 to G.H.), the Tianjin Applied Basic Research Diversified Investment–Urban Fire Protection Project (Grant No. 24JCQNJC00010 to G.H.), the General Program of Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 24JCYBJC01550 to G.H.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (040-63253198 & 040-63243125 to G.H.). Special thanks are also made to the Han Gang Research Lab members for their helpful suggestions related to the characterization of materials.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.X.P., Y.L.L., and G.H. designed research; Z.X.P. and Y.L.L. performed research; Z.X.P., Y.L.L., T.G.Y., F.X.Z., Y.L., J.Z., and T.Z. analyzed data; Z.X.P., Y.L.L., L.S. and G.H. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Niveen Khashab and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Z., Lei, Y., Yan, T. et al. Molecular manipulation of polyamide nanostructures reconciles the permeance-selectivity threshold for precise ion separation. Nat Commun 16, 7171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62376-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62376-8