Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by complex sensory processing deficits, which continue to elude comprehensive mechanistic understanding. A key unresolved question is how alterations in neural connectivity and communication translate into the behavioral manifestations seen in ASD. Here, we investigate how oligodendrocyte dysfunction alters myelin plasticity and neuronal activity, leading to auditory processing disorder associated with ASD. We focus on the SCN2A gene, an ASD-risk factor, to understand its role in myelination and neural processing within the auditory nervous system. Transcriptional profiling suggests alterations in the expression of myelin-associated genes in Scn2a conditional knockout mice, highlighting the cellular consequences engendered by Scn2a deletion in oligodendrocytes. The results reveal a nuanced interplay between oligodendrocytes and axons, where Scn2a deletion causes alterations in the intricate process of myelination. This disruption instigates changes in axonal properties, presynaptic excitability, and synaptic plasticity at the single cell level. Furthermore, oligodendrocyte-specific Scn2a deletion compromises the integrity of neural circuitry within auditory pathways, leading to auditory hypersensitivity. Our findings reveal a pathway linking myelin deficits to synaptic activity and sensory abnormalities in ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A prevailing hypothesis suggests that ASD emanates from alterations in brain connectivity1,2,3. Myelination is critical for brain connectivity and temporal processing in the developing brain by coordinating effective axonal conduction and neurotransmission4,5,6. Recent studies using neuroimaging and genetic analysis have shown atypical white matter development and abnormal myelination in individuals with ASD and animal models7,8. However, the specific impact of myelin alterations on neural connectivity, communication, and ultimately behavioral manifestations is not fully delineated. Notably, white matter integrity was altered in specific brain regions of humans with ASD, which are associated with sensory processing9,10. Auditory processing abnormalities, including auditory hypersensitivity, are well-documented in individuals with ASD9. Auditory hypersensitivity, as an excessive or abnormal response to auditory stimuli, may arise from alterations in sensory gain, neuronal activity, and excitation/inhibition (E/I) balance in the auditory circuitry11,12,13. These alterations could be potentially linked to abnormalities in myelination.

ASD has been associated with altered gene expression related to oligodendrocyte (OL) maturation and myelination8. OLs, the myelin-producing glia, play a more complex role in neural development. Beyond facilitating myelination, immature OLs monitor neuronal activities and influence their development14,15. Moreover, OLs engage in dynamic interaction with neurons, contributing to activity-dependent myelination, which in turn supports neural circuit plasticity16,17,18. Thus, OL dysfunction can disrupt neuron-glia interactions and alter ion channel expression along the axon, ultimately affecting neural plasticity5,19. However, the impact of OL dysfunction on myelination, neuronal activity, and synaptic plasticity at the single-cell level and how these alterations contribute to auditory processing deficits in ASD remains unexplored. Additionally, genetic and cellular interactions underpinning the neurodevelopmental feature of ASD require further study.

One gene of particular interest is Scn2a, which encodes the alpha subunit of the voltage-gated Na+ channel 1.2 (Nav1.2), and is highly linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD20,21,22. Loss-of-function mutations in Scn2a impair dendritic excitability, leading to synaptic dysfunction and behavioral deficits22,23,24. Scn2a expression in non-neuronal cells, specifically in oligodendrocyte, has been evident25,26,27. Notably, a transcriptional profile of OL lineage cells from the mouse brain showed that the highest levels of Scn2a expression are in newly formed OLs, an immature OL population. The cell-autonomous role of Scn2a in myelination and neuron-glia interaction remains to be elucidated.

Here, we show that Scn2a deletion specifically in OLs impairs myelination in distal axons, leading to abnormal presynaptic excitability, disrupted action potential propagation to nerve terminals, and altered synaptic activity. These deficits contribute to auditory processing disorders, a hallmark of ASD.

Results

Scn2a cKO mice exhibit auditory hypersensitivity without changes in peripheral function

SCN2A is identified as a high-risk gene associated with ASD, wherein abnormal sensory processing, including auditory hypersensitivity, is frequently observed9,28. In our study, mice with Scn2a haploinsufficiency (Scn2a+/– mice)24,29 exhibited a distinct and pronounced startle response to sudden and loud auditory stimuli (Supplementary Fig. 1A). This heightened startle response is consistent with the hypersensitivity commonly observed in individuals with ASD and in ASD mouse models24,30. Intriguingly, we also observed myelin deficits within the auditory nervous system of these Scn2a+/– mice (Supplementary Fig. 1B–E). To investigate the cell-autonomous role of oligodendrocyte Scn2a in the interplay between myelination and the auditory processing disorders, we utilized Scn2a conditional knockout (cKO) mice (PdgfraCreERT; Scn2afl/fl)27. First, we examined whether oligodendrocyte-specific deletion of Scn2a causes auditory processing abnormalities. In an acoustic startle reflex (ASR) test, Scn2a cKO mice displayed larger startle reflexes in response to stimuli above 95 dB SPL, comparing to control (Scn2afl/fl, n = 15 control mice vs n = 10 cKO mice, two-way ANOVA test, p = 0.0012, Fig. 1A). Scn2a cKO mice showed stronger startle at loud sound stimulation of 105 dB SPL (p = 0.0214) and 115 dB SPL (p = 0.0077, multiple comparison from two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction). The increased amplitude of the startle reflex in Scn2a cKO mice indicates heightened sensory perception, which is considered hypersensitivity. In addition, Scn2a cKO mice exhibited alterations in the pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) test. Typically, a weaker sensory stimulus (or pre-pulse) inhibits the reaction to a subsequent strong sensory event. In control, the inhibition drastically increased with the strength of pre-pulse stimulation. In contrast, Scn2a cKO mice demonstrated a diminished capacity to inhibit the startle reflex, particularly in response to the pre-pulse at 81 dB SPL sound stimulation (35.9 ± 3.22 % PPI, n = 18 control mice vs 24.7 ± 3.19 % PPI, n = 11 cKO mice, p = 0.0377, multiple comparison from two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction, Fig. 1B). The alteration in startle reflex to sound stimulation suggests that Scn2a cKO mice have an impaired sensory gating mechanism, a feature often seen in ASD13,24.

A Illustration of mouse acoustic startle reflex (ASR) and summary of ASR maximum startle amplitudes (mV) to sound stimuli (from 75 dB to 120 dB SPL, background = 65 dB SPL) in control (n = 15) and Scn2a cKO mice (n = 10). cKO mice showed significant increase of startle amplitude at 105 (p = 0.0214) and 115 dB SPL (p = 0.0077). B Pre-pulse inhibition (PPI, %) at different strength of pre-pulse stimuli (69, 73, 81 dB SPL) in control (n = 18) and Scn2a cKO mice (n = 11) showed significant reduction of inhibition at 81 dB SPL (p = 0.0377). C Illustration of mouse auditory brainstem response (ABR) test and representative traces of ABRs in response to click (80 dB SPL) from control and Scn2a cKO mice at P25. 5 distinct waves of neuronal activity corresponding to auditory nerve (I), cochlear nucleus (II), superior olivary complex (III), inferior colliculus (IV), and medial geniculate nucleus (V) in the auditory brainstem circuitry. D Summary of ABR thresholds of control (n = 46) and Scn2a cKO mice (n = 29) in response to click stimuli (from 30 dB to 90 dB SPL). There was no significant difference between groups (p = 0.1842, two-tailed unpaired t-test). E ABR amplitudes (µV) of wave I to V responding to 80 dB SPL clicks. The amplitude of peak II (p = 0.0002) and peak III (p = 0.0191) were significantly larger in Scn2a cKO mice (n = 26) compared to control (n = 39). F The ratio for the amplitude of wave I over the amplitude of each wave (II, III, IV, and V), evaluating central gain changes. G Summary of distortion products (DP, dB SPL) at 80 dB at various pure tone stimuli (4, 8, 12, 16, and 32 kHz) in control (n = 18) and Scn2a cKO mice (n = 7). Each data point represents the value per mouse, and means ± s.e.m. are shown. p-value from multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction at two-way ANOVA test shown with asterisk (A, B, E–G). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To ascertain the extent of auditory processing abnormalities in the sub-cortical regions of Scn2a cKO mice, we utilized in vivo auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) to assess the sum of evoked potential responding sound stimuli along the auditory pathway, particularly in the brainstem (Fig. 1C). There was no significant difference in ABR threshold (Fig. 1D). However, the amplitude of ABRs in response to 80 dB SPL (click) was significantly increased in Scn2a cKO mice compared to control (p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA). The amplitude of peak II (2.44 ± 0.166 µV, n = 39 control mice vs 3.30 ± 0.231 µV, n = 26 cKO mice, p = 0.0002, multiple comparison from two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction) and peak III (2.09 ± 0.129 µV in control mice vs 2.70 ± 0.149 µV in cKO mice, p = 0.0191) were significantly larger in Scn2a cKO mice compared to those of control (Fig. 1E). The increased amplitude of ABRs suggested that Scn2a cKO mice exhibit the hypersensitivity to sound. To evaluate whether there were alterations in central gain, we calculated the ratio between peak amplitudes II to V relative to peak I. There was no statistically significant difference between groups (p = 0.1763, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 1F). Next, we examined the possibility that the hypersensitivity is originated from alterations in peripheral hearing sensitivity. There was no significant change in ABR threshold, peak I amplitude, and distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE, p = 0.6601, two-way ANOVA, Fig. 1G), demonstrating intact peripheral hearing. Collectively, the results demonstrated robust behavioral phenotypes in Scn2a cKO mice, specifically auditory hypersensitivity and impaired sensory gating, mirroring sensory processing abnormalities in ASD.

Myelin related genes were significantly downregulated in mature OL from Scn2a cKO mice

To understand the impact of Scn2a deletion on OL development and myelination within the auditory brainstem circuitry, we characterized the single-cell transcriptional profiles of mouse auditory brainstem using single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq). After the exclusion of low-quality nuclei, we obtained a total of 3083 reliable nuclei for the analysis: 989 nuclei from the control and 2094 nuclei from Scn2a cKO mice. Shared Nearest Neighbor (SNN) clustering identified 16 distinct clusters on Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot, including clusters of neurons (Rbfox3 positive), astrocytes (Aldh1l1 positive), microglia (Itgam positive), and OL lineage cells (Pdgfra and Mog positive, Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, OL lineage cells consisted of five clusters: Oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), Differentiating OL1 (Diff. OL1), Differentiating OL2 (Diff. OL2), Premature OL, and Mature OL. To identify the OL lineage, we analyzed OL-specific genes, such as Pdgfra, Mbp and Mog, expressed in OPCs and mature OLs, respectively (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 2). Given the dynamic nature of OL differentiation, we utilized trajectory analysis to examine this continuous differentiation. The result of trajectory analysis from those populations displayed a narrow differentiation path connecting from OPCs to mature OLs, that similar to patterns in a previously reported study25. The result indicates that OL development follows a clearly defined trajectory, which was outlined by genetic markers specific to the OL lineage.

A (Top) UMAP plots of snRNA-seq dataset with clusters identified as OL lineage cells, indicated by dashed line circles; OPC, Differentiating OL1 (Diff. OL1), Differentiating OL2 (Diff. OL2), Premature OL, and Mature OL. (Bottom) Expression pattern of OL lineage marker genes such as Pdgfra and Mbp. Graded color indicators showed the scaled gene expression level. B (Left) The distribution of single cells colored according to the five OL lineage states identified by trajectory analysis from OPCs to mature OLs (gray line). (Right) The percentage (%) of each cluster (from OPC to Mature OL) in total OLs from individual controls (n = 2) and cKO mice (n = 2). C (Left) UMAP plots of snRNA-seq for OL lineage cells from control (blue dots) and cKO (red dots). (Right) The number of DEGs for each OL lineage. D Volcano plot of differentially expressed myelin related genes (391 genes) in control and cKO mice (without correction for multiple comparison). E 33 genes showed significant differential expression (p < 0.05, without correction for multiple comparison) and interconnection between those genes was detected in String analysis. Those genes were related to myelin structure (green line), cell junction (red), membrane protein signaling (blue), and ion channel (yellow). F Violin plots of top eight genes being downregulated in Scn2a cKO mice: Mobp, Ncam1, Ptn, Gnao1, Mtmr2, Abca2, Arhgef10 and Mpdz.

Although there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of OL lineage cells between control and Scn2a cKO mice, trends of a reduction in the mature OL population and a slight increase in OPCs and differentiating OLs was observed in the Scn2a cKO mice (Fig. 2B). When OL clusters from each genotype were visualized with different colors in the UMAP scatter plot, a distinct difference was observed in mature OLs (Fig. 2C). To quantify these differences further, we identified genes exhibiting significant differential expression between control and Scn2a cKO mice (adjusted p with Bonferroni correction <0.05). Notably, 96 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were detected in mature OLs between control and Scn2a cKO mice (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Datasets 1–5). This result reveals significant alterations in gene expression patterns within mature OLs, suggesting the cascading implications of Scn2a deletion in the orchestration of gene expression within mature OLs. Furthermore, to examine the expression level of myelin-associated genes in mature OLs, we employed AmiGo2, a gene ontology data base, to pick genes for comparison. Among the myelin-related genes (total 391 genes), 33 DEGs were identified (p < 0.05). Notably, the volcano plot showed that Mobp, encoding myelin associated oligodendrocyte basic protein (MOBP), was significantly decreased in Scn2a cKO mice (Fig. 2D). The String analysis revealed that 30 genes out of 33 DEGs have a significant interconnection and can be functionally characterized into four main categories: cell skeletal structure, cell junction, membrane, and ion channel (Fig. 2E). In addition, the most significant down regulated genes; Mobp31, Ncam132, Ptn33, Gnao134, Mtmr235, Abca236, Arhgef1037 and Mpdz38 are known to be related to myelination, cell growth, and neurological diseases (Fig. 2F). Taken together, the transcriptional profiles highlight a pronounced differential expression of myelin-associated genes in mature OLs from Scn2a cKO mice.

Loss of Scn2a impairs myelination in the auditory brainstem during postnatal development without affecting axon caliber

Following the gene expression analysis, we assessed the structural aspects of myelinated axons using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Fig. 3A). This evaluation focused on determining myelin thickness and axon caliber size within axon bundles located in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) in the auditory brainstem. Ultrastructural analysis revealed significant myelin deficits in Scn2a cKO mice, as evidenced by an elevated g-ratio, providing critical insights into the intricate alterations occurring at the structural level. The g-ratio is an indicator of myelin thickness measured by the inner radius (r) divided by the outer radius (R) of the axon in the corresponding axon bundles. To examine alteration in the distribution pattern of the g-ratio, linear regression analysis was used in which slope and y-intercept were compared between groups. While the regression slopes of control and Scn2a cKO were comparable, y-intercept was significantly higher in Scn2a cKO, and the right shift of the cumulative frequency curve indicates an increase in g-ratio in Scn2a cKO compared to control indicating a decreased myelin thickness in Scn2a cKO (Fig. 3B). Consistently, the g-ratio was significantly increased in Scn2a cKO, indicating a decrease in myelin thickness of axons in the MNTB area (0.79 ± 0.003, n = 685 control axons vs 0.84 ± 0.002, n = 736 cKO axons, p < 0.0001, two-tailed unpaired t-test, Fig. 3C). This change remained significant even when analyzed with biological replicates (0.80 ± 0.012, n = 5 control mice vs 0.84 ± 0.012, n = 4 cKO mice, p = 0.0317, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test). On the other hand, axon calibers showed slightly larger inner diameter in Scn2a cKO compared to control (1.39 ± 0.03 µm, n = 685 control axons vs 1.49 ± 0.03 µm, n = 736 cKO axons, p = 0.0204, two-tailed unpaired t-test), however, this difference was no longer significant when analyzed with biological replicates (1.53 ± 0.197 µm, n = 5 control mice vs 1.58 ± 0.109 µm, n = 4 cKO mice, p > 0.9999, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 3D). Furthermore, we quantified the total number of axons per unit area in the MNTB and found no significant difference in axon density between control and cKO mice (0.578 ± 0.048 axons/µm2, n = 6 control mice vs 0.499 ± 0.069 axons/µm2, n = 4 cKO mice, Fig. 3E). Taken together, the results suggest that the targeted deletion of Scn2a in OLs detrimentally affects myelination, as indicated by the increased g-ratio, without significantly altering axon number and caliber size within the auditory brainstem. Notably, the myelin deficits identified in Scn2a cKO mice were consistent with significant alterations in the expression of myelin-related genes in mature OLs from snRNA-seq data (Fig. 2).

A Representative TEM images of axons in the MNTB from control and Scn2a cKO mice at P25. B Scatter plot of g-ratio values plotted as a function of corresponding axon inner diameter of individual axons. Datapoints from individual axons and best fit lines are shown in black for control and red for Scn2a cKO. The regression slopes were 0.0452 in control and 0.0399 in Scn2a cKO mice (p = 0.0516, linear regression comparison, F = 3.795, DFn = 1, DFd = 1417). Y-intercept was significantly increased in Scn2a cKO mice (0.7315 in control vs 0.7800 in cKO, p < 0.0001, linear regression comparison, F = 216.4, DFn = 1, DFd = 1418), indicating decreased myelin thickness. (Inset) The histogram of the distribution of g-ratio and the respective cumulative frequency. C Summary of g-ratio measurement for individual axons (left, 685 control axons vs. 736 cKO axons, p < 0.0001) and the mean values per mouse as biological replicates (right, 5 control mice vs. 4 cKO mice, p = 0.0317). D Summary of inner diameter of individual axons (left, 685 control axons vs. 736 cKO axons, p = 0.0204) and the mean values per mouse (right, 5 control mice vs. 4 cKO mice, p > 0.9999). E Axon density (axon number/μm2) in the MNTB from 6 control mice and 4 cKO mice. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. p value from two-tailed unpaired t-test (left) and two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test (right) with asterisks (C–E). * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For further validation, we tested effect of Scn2a deletion on myelination in another OL-specific Scn2a cKO mice, in which Scn2a was removed from Sox10 expressing OLs, targeting all OL lineage cells (Sox10CreER; Scn2afl/fl)27, also displayed similar alterations in myelin, axon caliber size, and axon density (Supplementary Fig. 3). The observed myelin deficits in Scn2a cKO mice can be attributed to both impaired OL development and alterations in myelin-associated genes. A reduction in the differentiation of OPCs to OLs, evidenced by a decreased mature OLs (CC1+ OLs) in Scn2a cKO mice, further supports these findings27. Together, these results collectively underscore the pivotal role of Scn2a in axon myelination in the auditory brainstem.

OL-specific loss of Scn2a alters myelinated segments and Na+ channel expression at distal axons in the MNTB

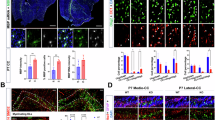

Given the significant alterations in myelination, we postulated that myelin changes might manifest in broader structural and functional aberrations within the neural circuitry. During development, immature OLs play a pivotal role by interacting with axons, which in turn determines the length of myelinated axon segments and nodes5. To elucidate the consequences of Scn2a deletion in OLs on these interactions, we examined the long-myelinated axon extending from the cochlear nucleus to the MNTB and its terminal, the calyx of Held. Myelinated axon segments, the internode, can be visualized by myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) and caspr (a paranodal marker) flanked by two sodium channel clusters (Pan Nav) denoting nodes of Ranvier (Fig. 4A). Thus, we assessed the length of the internode by measuring the distance between two Nav clusters (Fig. 4B). Structural analysis of the calyx axons revealed a shorter internode adjacent to the heminode at the distal axon in Scn2a cKO mice (42.71 ± 2.05 μm, n = 37 control axons vs. 32.02 ± 1.61 μm, n = 55 cKO axons, p = 0.0005, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA), while the length of subsequent internodes remained unchanged (p > 0.9999, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4C). The difference in internode 1 length approached statistical significance when analyzed with biological replicates (40.19 ± 2.11 µm, n = 10 control mice vs 31.25 ± 2.62 µm, n = 10 cKO mice, p = 0.0547, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA), but there was no difference in the length of internode 2 (53.07 ± 6.92 µm, n = 3 control mice vs 52.20 ± 4.64 µm, n = 5 cKO mice, p > 0.9999, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4C). It suggests a potential structural impact of Scn2a deletion in OLs on distal axonal myelination. The reduced length of the last myelinated segment in Scn2a cKO suggests that the myelinated segments near the nerve terminal may be underdeveloped or experience delayed development in these mice39. Furthermore, to determine if the thinner and shorter myelin alters ion channel distribution along the distal axon in Scn2a cKO mice, we examined the patterns of voltage-gated sodium channel (Nav) expression along the calyx of Held axon. Intriguingly, we found a dispersed Nav channel expression at heminodes in Scn2a cKO mice (2.51 ± 0.11 μm, n = 35 control axons vs 3.29 ± 0.17 μm, n = 67 cKO axons, p = 0.0003, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4D). Notably, dispersed Nav channels at the heminode have also been previously observed in dysmyelinated axon terminals5. Nevertheless, Nav clusters did not show any significant alteration either in node 1 (1.57 ± 0.10 µm, n = 24 control axons vs 1.83 ± 0.11 µm, n = 48 cKO axons, p = 0.7783, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA) and node 2 (1.41 ± 0.09 µm, n = 12 control axons vs 1.71 ± 0.11 µm, n = 17 cKO axon, p > 0.9999, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4D). This alteration remained significant when analyzed with biological replicates showing longer heminode in cKO (2.54 ± 0.381 µm, n = 6 control mice vs 3.39 ± 0.195 µm, n = 8 cKO mice, p = 0.0206, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA), but not in node 1 (1.55 ± 0.057 µm, n = 5 control mice vs 1.83 ± 0.165 µm, n = 7 cKO mice, p > 0.9999, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA) and node 2 (1.41 ± 0.045 µm, n = 3 control mice vs 1.64 ± 0.156 µm, n = 5 cKO mice, p > 0.9999, multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction from two-way ANOVA, Fig. 4D). This result highlights the pivotal role of Scn2a in OL development, emphasizing its influence on axon-OL interactions and Nav channel distribution at the distal axons in synapse-rich areas of the auditory brainstem during postnatal development.

A The distal axons and the calyx of Held terminals from cKO mouse (at P15) were dye-filled (lucifer yellow, color-coded with white) during whole-cell recording and subsequently post-immunostaining was performed. The MNTB was immunostained with antibodies against myelin proteolipid protein (PLP, green), Pan Nav (red, yellow arrows), and Caspr (cyan, white arrows). Scale, 20 μm. B Representative images of the calyx of Held axon labeled with Dextran, highlighting distal axons, including presynaptic terminal from control and cKO mouse. Immunostaining with Pan Nav reveals unmyelinated axon segments including heminodes, nodes, and internodes (myelinated segments). Scale, 20 μm. C Summary of internodal lengths, which were measured by the distance from the heminode to node 1 (internode 1, 37 axons from 10 control mice vs. 55 axons from 10 cKO mice, left: p = 0.0005, right: p = 0.0547) and node 1 to node 2 (internode 2, 12 axons from 3 control mice vs. 16 axons from 5 cKO mice) along the distal axon from control and cKO mice (at P21). Data are presented based on individual axons (left) and biological replicates (right). D Quantification of the length of Nav clusters (Pan Nav) at the heminode (35 axons from 6 control mice vs. 67 axons from 8 cKO mice, left: p = 0.0003, right: p = 0.0206), node 1 (24 axons from 5 control mice vs. 48 axons from 7 cKO mice), and node 2 (12 axons from 3 control mice vs. 17 axons from 5 cKO mice), based on individual axons (left) and biological replicates (right). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. p value from multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction at two-way ANOVA test shown with asterisk (C, D). * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The intrinsic excitability at the nerve terminal was altered in Scn2a cKO mice

Alterations in ion channel distribution at the heminode can impact the intrinsic properties of the nerve terminal and presynaptic firing patterns. To investigate this, we first measured the input resistances on the calyx of held and found no significant difference between control (187.8 ± 17.56 MΩ, n = 20 cells) and cKO mice (209.7 ± 22.62 MΩ, n = 24 cells; two-tailed unpaired t-test, p = 0.4626). Next, we examined intrinsic excitability at the calyx terminal by recording presynaptic action potentials (APs), evoked by depolarizing current injection. AP waveform analysis revealed that AP threshold was significantly higher in Scn2a cKO mice (−49.0 ± 0.76 mV, n = 32 cells from 17 control mice vs −46.9 ± 0.56 mV, n = 43 cells from 12 cKO mice, p = 0.0217, two-tailed unpaired t-test, Fig. 5A, B), with no substantial changes in AP amplitude (p = 0.0912, two-tailed unpaired t-test, Fig. 5B). The maximal dV/dt was lower in Scn2a cKO mice (468.1 ± 28.47 mV/ms, n = 33 cells from control vs 411.8 ± 30.17 mV/ms, n = 41 cells from Scn2a cKO, p = 0.0282, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test), indicating a slower AP rise time in Scn2a cKO mice than control. Furthermore, the minimal dV/dt was significantly reduced in Scn2a cKO mice (−359.80 ± 22.60 mV/ms, n = 28 cells from control vs −289.6 ± 21.40 mV/ms, n = 37 cells from Scn2a ckO, p = 0.0040, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test), indicating a slower repolarization. Other parameters in Scn2a cKO, despite not reaching statistical significance, showed trends of alteration: an increased rheobase current (p = 0.058, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test) and a broadened AP width (p = 0.1437, two-tailed unpaired t-test, Fig. 5B). An elevated threshold, a slower rising of the spike, and a slower repolarizing at the calyx terminal indicate that the nerve terminal has reduced excitability. To further support these findings, we also tested the intrinsic excitability by counting the number of APs evoked by incremental current injections. The input-output curves showed a distinct shift, demonstrating fewer APs per current step in Scn2a cKO (p = 0.0176, Two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Fig. 5C). Thus, the result suggests that alterations in Nav channel expression around myelinated segments have a profound impact on presynaptic excitability in Scn2a cKO mice. Intriguingly, another observation is that in ~20% of presynaptic recordings from Scn2a cKO (6 of 26 cells), the calyx terminal displayed aberrant spikes or/and spontaneous spikes when the resting membrane potential was around −65 mV (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, spontaneous firing and aberrant spikes have not been observed before in ex vivo recording from WT with the same experimental setting. The results demonstrated that myelin deficits at the distal axon caused by OL-Scn2a loss can generate asynchronous and abnormal spikes along the distal axon.

A Presynaptic action potentials (APs) elicited with a supra-threshold current injection (top) and their corresponding phase plots (dV/dt against membrane potential, bottom) in control (black) and Scn2a cKO (red). Arrows indicate the threshold of APs. AP threshold was determined by the point where dV/dt exceeds 10 mV/ms, and AP amplitude was calculated from the threshold to the AP peak in the phase plot (dashed lines). B Summary of AP waveform analysis: the rheobase (33 control cells vs. 42 cKO cells), threshold (32 control cells vs. 43 cKO cells, p = 0.0217), amplitude (n = 33 control cells vs. 42 cKO cells), half width (n = 33 control cells vs. 39 cKO cells), max dV/dt (33 control cells vs. 41 cKO cells, p = 0.0282), and min dV/dt (n = 28 control cells vs. 37 cKO cells, p = 0.0040). Individual datapoints are displayed in each bar graph. p-values from two-tailed unpaired t-test shown with asterisk. C (Top) Presynaptic APs elicited by step-like depolarizing current injection. (Bottom). The number of AP in response to each current injection (200 ms, from 50 pA to 400 pA, 21 control cells vs. 31 cKO cells). p-values from two-way ANOVA with multiple comparison shown at the top of figure. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Conduction failures impaired the reliability and fidelity of high frequency spikes at the nerve terminal in Scn2a cKO mice

To understand the implications of thinner myelin sheath and ion channel expression alterations at the distal axon observed in Scn2a cKO, we evaluated AP propagation along the distal axon and the fidelity of APs at the nerve terminal (Fig. 6A). This was achieved by measuring the failure rate (%), calculated as the ratio of the number of AP failures to the total number of stimuli ((Failure number/50 trials) × 100), across different frequencies. In control, the calyx terminal efficiently followed high-frequency stimulation and demonstrated spikes without failures at both 50 Hz and 100 Hz. Conversely, the calyx terminal in Scn2a cKO mice exhibited AP failures at 100 Hz and showed a drastic increase in failures at higher frequencies (Fig. 6B, C). Among total recorded axons in response to 200 Hz stimulation, 28% of axons in the Scn2a cKO displayed failures compared to only 18% in control mice. Furthermore, violin plots revealed a larger proportion of axons with over 80% failure at higher frequencies (300–500 Hz) in Scn2a cKO mice while no axons in control mice showed failure rate above 80% in the same frequency range (Fig. 6C). Thus, myelin defects and disruption of Nav channel clustering caused by Scn2a loss detrimentally affect the reliability and temporal fidelity of spikes at the nerve terminal.

A Illustration of the calyx of Held recording with a bipolar stimulator placed in the midline of the brainstem. B Representative traces of presynaptic action potential (AP) train stimulated at 200 Hz from control (black) and Scn2a cKO (red) mice. Gray arrowheads indicate AP failure during the train in Scn2a cKO mice. C (Left) Violin plots of AP failure rate from control and Scn2a cKO mice stimulated at varied frequencies (from 50 Hz to 500 Hz, 11 control cells vs. 18 cKO cells, p = 0.0048). Solid and dashed lines represent median and first and third quartile, respectively. (Right) The average of AP failure rate at varied stimulating frequencies. D The average stimulating intensity to initiate a single AP (Threshold intensity, TI, 11 control cells vs. 9 cKO cells) from control and Scn2a cKO. p values from two-tailed unpaired t-test shown with asterisk. E Representative traces of 200 Hz AP train from Scn2a cKO mice stimulated with TI, 20% increment from TI, and 40% increment from TI. Note that increasing stimulation intensity reduced AP failures. F (Left) Violin plots of 200 Hz AP failure rate reduced by incremental stimulating intensities in control and Scn2a cKO. Circles and squares indicate individual datapoint (11 control cells vs. 9 cKO cells). (Right) Summary from the left showing the average failure rate from incremental stimulating intensities. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. The median and quartiles were presented with solid and dashed line respectively, and p-values from two-way ANOVA with multiple comparison shown at the top of figure (C, F). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To discern whether AP failures at the nerve terminal are caused by conduction failures throughout the distal axon or failure to evoke AP, we tested if increasing the stimulus intensity could recover AP failures. First, we determined the minimum stimulating intensity (threshold intensity, TI) to trigger a single AP for each axon. We found that threshold intensity was significantly higher in Scn2a cKO than in control (0.55 ± 0.09 V, n = 11 cells from 3 control mice vs 1.43 ± 0.30 V, n = 9 cells from 4 cKO mice, p = 0.0048, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 6D). Next, we quantified failure rate in AP train (200 Hz stimulation) with incremental intensities (Fig. 6E). The calyx terminal from Scn2a cKO showed significantly higher failure rates at the TI (10.00 ± 6.49 %, n = 11 cells from 3 control mice vs 47.78 ± 7.95 %, n = 9 cells from 4 cKO mice, p = 0.0117, multiple comparison with Sidak correction from two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Fig. 6F) which was recovered by increased stimulating intensity. Interestingly, all axons in control with failures at TI were able to recover by TI + 20% intensity, whereas such intensity could only recover ~56% of axons in Scn2a cKO. Most of the axons with failures in Scn2a cKO required at least TI + 40% to recover (Fig. 6F). These findings were similarly observed in another OL-specific cKO mice (Sox10CreER; Scn2afl/fl, Supplementary Fig. 5). Taken together with EM and immunostaining analysis, these results suggest that a shortened distal internode and thinner myelin critically impair axon conduction throughout the distal axon and cause AP failures at the nerve terminal.

Alterations in structural and functional properties of the nerve terminal impact synaptic transmission and short-term plasticity

Alterations in myelination and axonal properties at the nerve terminal critically impact synaptic plasticity4,40. To investigate the effects of myelin alternation in distal axons on synaptic activities, we evaluated synaptic transmission and short-term plasticity at the calyx of Held-MNTB synapse using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings. In the analysis of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs), we did not observed any statistically significant alteration in amplitude (36.90 ± 3.377 nA, n = 31 control cells vs 43.94 ± 4.283 nA, n = 29 cKO cells, p = 0.1989, two-tailed unpaired t-test), but we observed a trend toward an increase in frequency (0.574 ± 0.142 Hz, n = 31 control cells vs 0.992 ± 0.208 Hz, n = 27 cKO cells, p = 0.0963, two-tailed unpaired t-test, Fig. 7A). Furthermore, we recorded evoked EPSCs triggered by afferent fiber stimulation at the midline. There was no significant difference in the amplitude of a single EPSC between groups (6.56 ± 0.340 nA, n = 25 cells from 9 control mice, 6.45 ± 0.612 nA, n = 14 cells from 8 cKO mice, p = 0.8735, two-tailed unpaired t-test, Fig. 7A). However, the paired-pulse ratio was significantly reduced in Scn2a cKO mice (0.852 ± 0.019, n = 25 cells vs 0.678 ± 0.060, n = 14 cells, p = 0.0157, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 7B), indicating an alteration in release probability (Pr). To further investigate this, we analyzed EPSC trains induced by 100 Hz fiber stimulation (50 stimuli, Fig. 7C), employing three established analytical methods for the calyx synapse41. Although trends were observed in Pr and RRP size, statistical significance varied among methods (Supplementary Fig. 6). In the train method analyses42, the vesicle number of RRPs, estimated by extrapolating to the y-axis and dividing the y-intercept value by the amplitude of mEPSCs, was significantly reduced in Scn2a cKO mice (p = 0.0160, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 7D). Pr tended to be higher in Scn2a cKO mice but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0737, Fig. 7E). Additionally, the replenishment rate was significantly lower in Scn2a cKO mice (p = 0.0107, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. 7E), suggesting impaired vesicle availability and recycling at the presynaptic terminal. These changes in the number of vesicles around the active zone, including the size of the readily releasable pool and reduced replenishment, could lead to enhanced short-term depression. Taken together, OL dysfunction led to myelin alterations at the distal axon, which in turn impacted synaptic plasticity at local synapses within the auditory brainstem circuitry.

A (Left) Representative trace of miniature excitatory synaptic currents (mEPSCs) from control and Scn2a cKO mice. (Right) Summary of mEPSC amplitude (31 control cells vs. 29 cKO cells) and frequency (31 control cells vs. 27 cKO cells). B (Left) EPSCs evoked by afferent fiber stimulation with 50 ms interval for paired pulse ratio (PPR). (Right) Summary of PPR in control and cKO (25 control cells vs. 14 cKO cells, p = 0.0157). C Representative traces of eEPSC trains generated at 100 Hz stimulation. D (Left) Plot of cumulative EPSCs against stimulus number in control and cKO. A line fit to the steady-state points (the last 10 of 50 points) is back-extrapolated to the y-axis, and the y-intercept (arrows) divided by the mEPSC amplitude estimates the RRP size. (Right) The number of vesicles of the RRP in 21 control cells and 13 cKO cells (p = 0.0160). E (Left) The release probability (Pr, 20 control cells and 13 cKO cells, p = 0.0737) is calculated by dividing the amplitude of the first eEPSC by the RRP size (the y-intercept in (D)). (Right) The replenishment rate (20 control cells and 12 cKO cells, p = 0.0107) of vesicles, which is estimated by the slope of the linear fit. p-values from two-tailed unpaired t-test (A) and two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test shown with asterisk (B, D, E). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Understanding the fundamental mechanisms of neuronal activity and their interplay with genetic factors provides invaluable insights for neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD. We investigated the role of OL-Scn2a in the developing auditory brain from the genetic profiling to the systemic analysis. Scn2a cKO mice showed hypersensitivity to sound stimulation. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing revealed that the loss of OL-Scn2a impacts myelin-related gene expression in the auditory brainstem. Ultrastructural analysis of myelinated axons demonstrated thinner myelin in Scn2a cKO mice. Electrophysiology and immunostaining showed that alterations in myelinated segments and nodal structure along the distal axon influenced the excitability of the nerve terminal, causing a reduced fidelity and reliability of spikes in Scn2a cKO mice. Additionally, those changes in the interaction between immature OLs and nerve terminal impact synaptic functions. Our findings highlight the temporal progression of myelination in early development and its potential links to the onset or severity of ASD symptoms, offering potential aids for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic interventions.

Abnormal development in white matter and myelination has been found in ASD animal models and humans with autism43,44,45,46. However, how myelin changes are associated with compromised neural circuit function in ASD remains unclear. Disruptions to myelin can influence axonal integrity, altering ion channel distribution, and consequently affect neuronal excitability5,19. Specifically, the spacing and periodicity of myelin segments determine Nav channel distribution at nodes and heminodes, enabling saltatory conduction and precise neural signaling5,39. In MBP-deleted rats, hypomyelination led to disorganized Nav channel clustering and shorter internode, which are associated with a delayed AP onset, a longer AP half-width, and AP failures at the nerve terminal5,47. In the cortical gray matter neuronal circuitry, cuprizone-induced demyelination caused hyperexcitability in pyramidal neurons by altering the axon initial segment (AIS) position and reducing the efficacy of AP generation19. The current study expands the dimensions of what have been previously reported by examining the effects of OL-Scn2a loss on myelin and axonal integrity, specifically at distal axons near nerve terminals. We demonstrate that OL-Scn2a loss leads to alterations in ion channel redistribution and aberrant excitability at nerve terminals, such as conduction failure and spontaneous spiking. This is particularly pertinent as Scn2a-expressing immature OLs are abundant in synapse-rich regions like the MNTB. Interestingly, we observed that OL-Scn2a loss had more pronounced effects at nerve terminals than on nodes, which differs from prior models like MBP-deleted or cuprizone-induced demyelination. In these demyelination models, mature OLs were either unable to myelinate properly or underwent cell death5,19. In contrast, Scn2a cKO mice may have impaired interactions between immature OLs and distal axons, significantly affecting nerve terminal function, including neurotransmitter release and short-term synaptic plasticity during postnatal development. Therefore, our study underscores the region-specific relationship between myelin integrity and ion channel distribution in the developing brain. We emphasize that any disturbances in myelin structure can trigger cascading effects on neuronal excitability and synaptic function in the CNS, especially at nerve terminals in the auditory nervous system.

While OL dysfunctions are highly associated with the pathophysiological process of ASD, few studies have focused on ion channels of OLs. Ion channels, including voltage-gated calcium channels (Cav), sodium channels (Nav), potassium channel (Kv), and inward-rectifier potassium channels (Kir), are expressed in OLs48,49,50. While the functions of Cav and Kir channels in OLs are relatively well-defined, the roles of Nav remain unclear. Our snRNA-seq data demonstrated a decline in the mature OL population coupled with an increase in OPCs and differentiating OLs in Scn2a cKO mice. In addition, OL-Scn2a deletion was found to down-regulate myelin-related genes in mature OLs. How is Nav1.2, encoded by Scn2a, involved in OL maturation and myelination? One possible explanation is that the activation of Nav1.2 may be pivotal for triggering Cav activation, leading to a Ca2+ flux within OLs, which is involved in OL proliferation, migration, and differentiation49. Specifically, Ca2+ signaling facilitated by R-type Cav in myelin sheaths at paranodal regions might influence the growth of myelin sheaths48,51. To activate high-voltage activated calcium channels such as L- and R-Type efficiently, the activation of Nav1.2 should be required for depolarizing OL membrane to around −30 mV52. Consequently, the synergic interplay between Nav1.2 and Cav could amplify calcium signaling in OLs, initiating the differentiation and maturation processes49. Another possibility is that Nav1.2-mediated spiking in immature OLs could facilitate the release of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, which impacts myelination via autocrine signaling. OLs are significant providers of BDNF and express the BDNF receptor TrkB53. Therefore, Nav1.2-mediated excitability of immature OLs may enhance myelination through BDNF–TrkB autocrine signaling in response to neuronal activity.

One prevalent characteristic of ASD is sensory processing disorders, notably auditory hypersensitivity. For example, Fmrp1 KO mice showed hypersensitivity in hearing perception attributed to aberrant activity in the auditory cortex54,55. Similarly, Shank3 KO mice displayed auditory hypersensitivity, as evidenced by amplified ABR responses and a heightened startle reflex in the ASR56. Here, Scn2a cKO mice displayed augmented ABR amplitudes and a stronger startle reflex, despite no peripheral changes. Notably, these mutant mice showed myelin defects in the CNS57,58. This raises the question: How are alterations in myelin and neuronal properties associated with auditory processing disorder? Defects in myelination within auditory pathways can lead to synchronization issues among neurons responsible for sound processing. Increased asynchronized signals can compromise the precise timing required for sound localization and the discernment of complex auditory patterns. In Scn2a cKO mice, a loss of temporal fidelity at presynaptic terminals and inconsistent spike conduction along myelinated axons was observed. Notably, ~20% of presynaptic recordings exhibited aberrant and asynchronous spikes at the nerve terminal in Scn2a cKO. This atypical firing of auditory neurons can contribute to auditory hypersensitivity. Neuronal firing rates were abnormally increased following demyelination, resulting in hyperexcitability of the neural circuitry19,59. This hyperexcitability may be caused by alterations in sodium channel distribution and a rise in extracellular potassium along the myelinated axon60. Another possibility is that hypersensitivity may also emerge from changes in the intricate balance between excitatory and inhibitory regulation within the auditory brainstem. A decline in inhibitory neurons or disruptions in inhibitory inputs can induce hypersensitivity61,62. In Shank3 KO mice, hypersensitivity might be caused by diminished inhibitory regulation in the auditory circuit56. Interestingly, the MNTB serves as a major inhibitory source, releasing GABA and glycine to various nuclei within the superior olivary complex. Consequently, abnormalities in temporal fidelity and altered neurotransmission in the MNTB may disrupt the excitatory and inhibitory balance in this subcortical circuitry, potentially leading to auditory hypersensitivity.

In conclusion, the integrity of the myelin sheath plays a pivotal role in regulating neuronal excitability and ensuring proper auditory function. Defects in myelination can create a spectrum of auditory dysfunctions, including hypersensitivity. Our results demonstrated how OL-Scn2a is involved in the relationship between myelin defects, neuronal excitability, and auditory pathology in ASD, potentially paving the way for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Ethics statement

Animal studies were performed according to the regulations of the institutional animal care and use committee. Approval was obtained from the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) under protocol PRO00011243. All animals used in this study were taken cared under 12 light/12 dark cycle with ad libitum feeding and drinking.

Animals

Conventional Scn2a mutant mice (Scn2a+/+ and Scn2a+/– mice, C57BL6/J background, given by Kevin Bender (UCSF))29 and conditional Scn2a knockout mice27 were used. To create OL-specific Scn2a knockout mice, we crossed a Scn2afl/fl mice (C57BL6/J background, this line was generated in this lab) with two OL-specific Cre-recombinase expressing mouse lines, PdgfraCreERT mice (C57BL6/J background, Jackson labs, Stock #018280) and Sox10CreERT (C57BL6/J background, given by Shin Kang (Temple)), generating double transgenic mice (PdgfraCreERT; Scn2afl/fl and Sox10CreERT; Scn2afl/fl) as described in a previous study27. Littermates without a Cre-recombinase but with Scn2afl/fl were used as control (Scn2afl/fl). 70 mg/kg of tamoxifen was administered via i.p. injection at postnatal days (P) 4, 6, and 8. To validate the specificity of Cre expression, PdgfraCreERT mice were crossed with the Ai9 reporter line (C57BL6/J background, Jackson labs, Stock #007909), and tdTomato expression was examined (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, to confirm the conditional knockout of Scn2a in oligodendrocyte, brains from control and cKO were dissociated using Adult Brain Dissociation Kit (#130-107-677, Miltenyi Biotec). Oligodendrocytes were isolated from the brain tissue of control and cKO using Anti-O4 MicroBeads (#130-096-670, Miltenyi Biotec) and magnetic column (LS Columns #130-042-401, Miltenyi Biotec). mRNA was extracted from the isolated oligodendrocytes and non-oligodendrocytes using RNA isolation kit (#AM1931, Invitrogen), and cDNAs were synthesized from them using RT kit (#43-874-06, Applied Biosystems). qPCR was performed targeting exon 4–6 of Scn2a (Forward: 5’-GTCTAGAAGATTTCACATTTCTACG-3’, Reverse: 5’-CAGAACACAGTGAGTATCATGACG-3’). The qPCR analysis confirmed the conditional knockout of Scn2a in oligodendrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 7). Both male and female mice aged P15-P21 were used for immunohistochemistry, EM, and ex vivo electrophysiology. Mice of both sexes aged P21-P27 were used for snRNA-seq, ABR, ASR, and DPOAE.

Slice preparation

After rapid decapitation of the mice, which were deeply anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, the brainstem was quickly removed from the skull and immersed in ice-cold low-calcium artificial CSF (aCSF) containing the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 25 glucose, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 3 myoinositol, and 2 Na-pyruvate, pH 7.3–7.4 when bubbled with carbogen (95% O2/5% CO2), and 310–320 mOsm/L. The brainstem was sectioned (200 μm thick for electrophysiological recordings and immunostaining) and the slices were transferred to an incubation chamber containing normal aCSF bubbled with carbogen, where they were maintained for 30 min at 34–35 °C and thereafter at room temperature (24 °C). Normal aCSF was the same as low calcium aCSF, but with 1 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2.

Single nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq)

A snRNA-seq was conducted using brainstem tissues from control (Scn2afl/fl) and Scn2a cKO mice (PdgfraCreERT; Scn2afl/fl, P22). The brainstem was dissected and mechanically homogenized using dounce homogenizer in homogenizing buffer (250 mM sucrose, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris, 1 uM DTT and 0.1% Triton-X100) supplemented with enzymatic RNase Inhibitor (400 U/ml). 700 µl of homogenization solution was added. Homogenization involved 5 strokes of a loose pestle and 10–15 strokes of a tight one. The resultant solution was completed to 1 ml and passed through a 40 μm strainer. Post centrifugation, nuclei were rinsed with PBS containing RNAse inhibitor. A subsequent filtration through a 20 µm strainer was done before resuspending in 1 ml of PBS fortified with RNAse inhibitor. For fixation, 3 ml of 1.33% PFA was added to the nuclei for 10 min, followed by permeabilization using 160 μL of 5% Triton X-100 for 3 min. After washing out the PFA, nuclei were suspended in PBS with RNAse inhibitor and quantified manually via a hemocytometer. The fixed nuclei were barcoded and prepared for library using the Evercode WT Mini kit (Parse Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The final library underwent sequencing on Novaseq 500 at Novegen (Sacramento, CA).

The raw reads were mapped and quantified using split-pipe v1.0.3 (Parse Biosciences). The count data was analyzed using Seurat63 in R. To minimize artificial error, the cells with more than 1% mitochondria DNA and 5000 transcripts were considered dead cells and doublet cell, and those were excluded from further analysis. All nuclei were clustered using shared nearest neighbor (SNN) and plotted using Seurat in R. Each cluster was manually identified by examining expression of cell markers (Pdgfra/Cspg4 for OPC, Mog/Mbp/Plp1 for mature OL, Aldh1l1 for astrocyte, Itgam/Csf1r for microglia, Pecam1 for vascular cells, Rbfox3 for neuronal population). To examine oligodendrocyte differentiation, the oligodendrocyte lineage clusters were isolated from the data set and trajectory analysis was conducted using Monocle3 in R64. The population of each differentiation stage of oligodendrocytes was calculated from [number of nuclei from each cluster/total number of nuclei from all of OL lineage]. To examine gene expression pattern in each cluster, the differentially expressed genes between control and cKO were obtained with DESeq265 method with Bonferroni multiple comparison correction in Seurat. For further analysis, we isolated matured OL cluster, where showed significant gene expression difference between groups, and examined expression level of myelin-related genes. To list myelin-related genes, Amigo266 was used. 391 genes were searched on Amigo2 using the keyword “myelin”. The expression level of the genes was compared between groups using DESeq2 methods without multiple correction. The DEGs from the analysis were used gene network analysis using String67. The network was manually categorized based on their function. All of data visualization was done using ggplot268 and String.

Electrophysiology

Slices were perfused with normal aCSF at 2 ml/min and visualized using an infrared differential interference contrast microscope (AxoExaminer, Zeiss, Oberkochen Germany) with a 63× water-immersion objective and a CMOS camera (ORCA-Flash2.8, Hamamatsu, Japan). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed in normal aCSF at room temperature (24 °C) using an EPC-10 amplifier controlled by PATCHMASTER software (HEKA, Elektronik, Lambrecht/Pfalz, Germany). For recordings of eEPSCs, the pipettes were filled with a solution containing the following (in mM):130 Cs-methanesulfonate, 10 CsCl, 5 Na2-phosphocreatine, 10 HEPES, 5 EGTA, 10 TEA-Cl, 4 Mg-ATP, and 0.3 GTP, pH adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH. To this solution, we added 4 mM QX-314 bromide to block the voltage-activated Na+ channel current. Extracellular aCSF solution contained 10 mM bicuculline and 2 mM strychnine to block GABA and glycine receptors, respectively. The holding potential was –70 mV in the voltage-clamp mode. Patch electrodes had resistances of 4–5 MΩ. Series resistance was <20 MΩ, with 80% compensation. Afferent fibers of the calyx of Held synapses were stimulated with a bipolar electrode. For presynaptic recordings, the pipette solution contained (in mM): 125 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 5 Na2-phosphocreatine, 10 HEPES, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.2 EGTA, and 0.3 GTP, pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. Recordings were not corrected for the predicted liquid junction potential of 11 mV. Patch electrodes had resistances of 4–5 MΩ. Current-clamp recordings were continued only if the initial uncompensated series resistance was <20 MΩ4,5. Lucifer Yellow (1 mM, Invitrogen) was added to the pipette solution to visualize the calyx of Held terminal. Presynaptic action potentials (APs) from the calyx of Held terminal were evoked by stimulation with a bipolar platinum-iridium electrode (Frederick Haer, Bowdoinham, ME) placed near the midline spanning the afferent fiber tract of the MNTB. An Iso-Flex stimulator driven by a Master 10 pulse generator (A.M.P.I., Jerusalem, Israel) delivered 100-µs pulses at 1.2 times threshold ( < 15 V constant voltage). Signals were filtered at 2.9 kHz and acquired at a sampling rate of 10–50 µs. AP waveform parameters were analyzed from the first AP induced by minimum current injection (rheobase current) and the subsequent AP phase plot, where membrane potential slope (dV/dt) is plotted against the membrane potential69. In both, and Scn2a cKO mice, all cells displayed a single inflection in the rising phase of the AP, indicating APs were generated at the heminode adjacent to the presynaptic terminal. Presynaptic AP trains were obtained by averaging three sweeps (five for a single AP) in each experiment. Data were analyzed offline and presented using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Auditory brainstem responses (ABRs)

To record ABR, the mice (P21–P27) were anesthetized with 3.5% isoflurane and maintained with 2.3% isoflurane during recording (1 L/min O2 flow rate). ABR recordings were performed in a sound attenuation chamber (Med Associates, Albans, VT). Subdermal needle electrodes (Rochester Electro-Medical, Lutz, FL) were placed on the top of the head, ipsilateral mastoid, and contralateral mastoid as the active, reference, and ground electrode, respectively. The signal differences in the ABRs between the vertex and the mastoid electrodes were amplified and filtered (100–5000 Hz). Acoustic stimuli were generated by an Auditory Evoked Potentials Workstation (Tucker-Davis Technologies [TDT], Alachua, FL). Closed field click stimuli were presented to the left ear. The signals consisted of a series of amplitude-modulated square waves (0.1 ms duration, 16/s) through TDT Multi-Field Magnetic Speakers. The sound stimuli were delivered through a 10-cm plastic tube (Tygon; 3.2-mm outer diameter) at a repeat rate of 16/s. Sound intensities ranged from 90 to 20 dB, with 5-dB decrements, and responses to 512 sweeps were averaged.

Distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs)

Mice were anesthetized with 3.5% isoflurane and maintained with 2.3% isoflurane during recording. DPOAE recordings were performed in a sound attenuation chamber (Med Associates, Albans, VT). Acoustic stimuli were generated by an Auditory Evoked Potentials Workstation (TDT, Alachua, FLO). The ER-10B+ recording microphone (Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL) with ear-tip was inserted into the ear canal. The sound stimuli were delivered through two TDT Multi-Field Magnetic Speakers connected to the recording microphone by 10-cm coupling tubes (Tygon; 3.2 mm outer diameter). Pure tones were presented at 20% frequency separation between f1 and f2 at 4, 8, 12, 16, and 32 kHz. Sound intensities ranged from 80 to 20 dB, with 10-dB decrements, and responses to 512 sweeps were averaged.

The maximum sound intensity of 80 dB was chosen based on the level at which physiological differences were observed in ABR, without introducing confounding effects of excessive sound pressure levels on cochlear condition. Distortion products were calculated as 2f1–f2 minus the noise floor that were detected by the recording microphone and amplified by RZ6 processor (TDT).

Acoustic startle responses (ASRs)

Mice of either sex between ages P25–P27 were put in a Plexiglas holding cylinder located in a sound-attenuated chamber using the SR-LAB startle response system (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). Weights of mice were recorded to account for sex or size differences. Sound levels from the chamber speakers were calibrated with a digital sound level meter (Part Number MS-M80A, Mengshen). Each trial consisted of an initial acclimation period of 5 min of background level noise (at 65 dB) followed by 5 rounds of randomized noise stimuli playing for 40 milliseconds with 15 s of background between each noise stimuli at 65 dB (background), 95 dB, 105 dB, 115 dB, and 120 dB. Stimuli was produced by a digital signal processing-controlled system amplified and emitted by a loudspeaker. Startle responses were measured inside the sound-attenuated chamber by a movement-sensitive piezo-accelerometer platform. The maximum was used as the startle amplitude at each tone, with millivolts (mV) as the unit of measurement, and averaged per mouse. For each strength of stimulus, startle amplitudes were averaged across 10 trials. Startle responses to the three initial stimuli were excluded from statistical analyses.

Pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) of acoustic startle response

PPI of ASR was examined 2 days after the ASR assessment. The apparatus and basic experimental conditions were identical to that described above. Test sessions started with the acclimatization period, which included three startling stimuli (120 dB) to accustom the mice to the experimental procedure. The initial stimuli were followed by 100 trials (10 × 10 trials) presented in a random order. The PPI session involved: 10 trials with a sham stimulus (65 dB, 40 ms), three types (3 × 10) of pre-pulse trials (PP) which included only 20 ms PP stimuli (69, 73, and 81 dB), 10 pulse trials (P) which included only a pulse (startling) stimulus (120 dB, 40 ms), three types (3 × 10) of pre-pulse-and-pulse trials (PP-P) which included a 20 ms PP (69, 73, and 81 dB) followed 100 ms later by a 120-dB P stimulus. Startle responses were measured for 100 ms after the onset of the last stimulus within each trial. For each type of trial, startle amplitudes were averaged across 10 trials. The magnitude of PPI was calculated as a percent inhibition of the startle amplitude in the P trial (treated as 100%) according to the formula: [startle amplitude in P trials–startle amplitude in PP-P trials)/startle amplitude in P trials] × 100%. Startle responses to the three initial stimuli were excluded from statistical analyses.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse brainstem slices (200 µm) stained with tetramethylrhodamine dextran (Invitrogen) were incubated in normal aCSF bubbled with carbogen at 37 °C for 30 min. All slices were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. Free-floating sections were blocked in 3% goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min and incubated with the primary antibody overnight at room temperature. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-PanNa (mouse IgG1; 1:400; Sigma, Cat. #S8809), anti-Caspr (guinea pig IgG; 1:200; gifted from Dr. Manzoor Bhat, UTHSCSA), anti-PLP1 (mouse IgG2a, 1:500; Invitrogen, Cat. #MA1-80034). Antibody labeling was visualized by incubation of appropriate Alexa fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. Stained slices were viewed with laser lines at 488 nm, 568 nm, and 647 nm using a 40x/1.40 or 63×/1.40 oil-immersion objective on a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM-710; Zeiss). Stack images were acquired at a digital size of 1024 × 1024 pixels with optical section separation (z-interval) of 0.5 µm and were later crop to the relevant part of the field without changing the resolution. The confocal image stacks were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Transmission electron microscopy

The brain was removed and immersed in ice-cold low-calcium aCSF (mentioned previously in slice preparation), and the MNTB from the brainstem was dissected at a 200 µm-thick section using a microtome (VT1200s, Leica), then fixed with fixative consisting of 4% formaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde and stored at 4 °C. Further processing was performed by the UTHSCSA Electron Microscopy Lab as previously described40. Axon bundle images were analyzed at a final magnification of 8000X, with the longest length of the axon measured as the inner diameter and the inner radius divided by the outer radius as the g-ratio. Three images of axon bundles per mouse were analyzed and averaged.

Statistical analysis

Immunostaining data were based on analyses from at least six cells in six slices from three to eleven animals. Experimental data were analyzed and presented using Igor Pro and Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For statistical significance, we tested the normality of the data distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test with the Dallal-Wilkinson-Lillie p-values using Prism. If a dataset passed the normality test, we used the parametric test (two-tailed unpaired t-test for two-group comparison, ANOVA for multiple comparison); for all other datasets we used the non-parametric test (two-tailed Mann-Whiney U test for two-group comparison). For linear regression analysis, slope and intercept values were compared. Data collected as raw values are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Details of statistical methods are reported in the text. For all analyses, p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The gene expression data in this study have been deposited in the GEO NCBI under the accession code GSE252185. All other data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

R script for the analysis can be accessible as supplementary data.

References

Yamasaki, T., Maekawa, T., Fujita, T. & Tobimatsu, S. Connectopathy in autism spectrum disorders: a review of evidence from visual evoked potentials and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Front Neurosci. 11, 627 (2017).

Muller, R. A. From loci to networks and back again: anomalies in the study of autism. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1145, 300–315 (2008).

Fields, R. D. White matter in learning, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 31, 361–370 (2008).

Kim, S. E., Turkington, K., Kushmerick, C. & Kim, J. H. Central dysmyelination reduces the temporal fidelity of synaptic transmission and the reliability of postsynaptic firing during high-frequency stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 110, 1621–1630 (2013).

Berret, E., Kim, S. E., Lee, S. Y., Kushmerick, C. & Kim, J. H. Functional and structural properties of ion channels at the nerve terminal depends on compact myelin. J. Physiol. 594, 5593–5609 (2016).

Moore, S. et al. A role of oligodendrocytes in information processing. Nat. Commun. 11, 5497 (2020).

Ameis, S. H. et al. A diffusion tensor imaging study in children with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, OCD, and matched controls: distinct and non-distinct white matter disruption and dimensional brain-behavior relationships. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 1213–1222 (2016).

Phan, B. N. et al. A myelin-related transcriptomic profile is shared by Pitt–Hopkins syndrome models and human autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 375–385 (2020).

O’Connor, K. Auditory processing in autism spectrum disorder: a review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 836–854 (2012).

Owen, J. P. et al. Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders. Neuroimage Clin. 2, 844–853 (2013).

Lee, E., Lee, J. & Kim, E. Excitation/inhibition imbalance in animal models of autism spectrum disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 838–847 (2017).

Sohal, V. S. & Rubenstein, J. L. R. Excitation-inhibition balance as a framework for investigating mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1248–1257 (2019).

Castro, A. C. & Monteiro, P. Auditory dysfunction in animal models of autism spectrum disorder. Front Mol. Neurosci. 15, 845155 (2022).

Barres, B. A. & Raff, M. C. Proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells depends on electrical activity in axons. Nature 361, 258–260 (1993).

Hughes, E. G., Orthmann-Murphy, J. L., Langseth, A. J. & Bergles, D. E. Myelin remodeling through experience-dependent oligodendrogenesis in the adult somatosensory cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 696–706 (2018).

Gibson, E. M. et al. Neuronal activity promotes oligodendrogenesis and adaptive myelination in the mammalian brain. Science 344, 1252304 (2014).

Steadman, P. E. et al. Disruption of oligodendrogenesis impairs memory consolidation in adult mice. Neuron 105, 150–164 e156 (2020).

Pan, S., Mayoral, S. R., Choi, H. S., Chan, J. R. & Kheirbek, M. A. Preservation of a remote fear memory requires new myelin formation. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 487–499 (2020).

Hamada, M. S. & Kole, M. H. Myelin loss and axonal ion channel adaptations associated with gray matter neuronal hyperexcitability. J. Neurosci. 35, 7272–7286 (2015).

Sanders, S. J. et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature 485, 237–241 (2012).

Ben-Shalom, R. et al. Opposing effects on NaV1.2 function underlie differences between SCN2A variants observed in individuals with autism spectrum disorder or infantile seizures. Biol. Psychiatry 82, 224–232 (2017).

Spratt, P. W. E. et al. The autism-associated gene Scn2a contributes to dendritic excitability and synaptic function in the prefrontal cortex. Neuron 103, 673–685.e675 (2019).

Middleton, S. J. et al. Altered hippocampal replay is associated with memory impairment in mice heterozygous for the Scn2a gene. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 996–1003 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Impaired cerebellar plasticity hypersensitizes sensory reflexes in SCN2A-associated ASD. Neuron 112, 1444–1455 e1445 (2024).

Marques, S. et al. Oligodendrocyte heterogeneity in the mouse juvenile and adult central nervous system. Science 352, 1326–1329 (2016).

Berret, E. et al. Oligodendroglial excitability mediated by glutamatergic inputs and Nav1.2 activation. Nat. Commun. 8, 557 (2017).

Gould, E. & Kim, J. H. SCN2A contributes to oligodendroglia excitability and development in the mammalian brain. Cell Rep. 36, 109653 (2021).

Gomes, E., Pedroso, F. S. & Wagner, M. B. Auditory hypersensitivity in the autistic spectrum disorder. Pro Fono 20, 279–284 (2008).

Planells-Cases, R. et al. Neuronal death and perinatal lethality in voltage-gated sodium channel alpha(II)-deficient mice. Biophys. J. 78, 2878–2891 (2000).

Gibson, J. M. et al. Cerebellar contribution to autism-relevant behaviors in fragile X syndrome models. Cell Rep. 42, 113533 (2023).

Montague, P., McCallion, A. S., Davies, R. W. & Griffiths, I. R. Myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein: a family of abundant CNS myelin proteins in search of a function. Dev. Neurosci. 28, 479–487 (2006).

Massaro, A. R. The role of NCAM in remyelination. Neurol. Sci. 22, 429–435 (2002).

Liu, Z. et al. Sec13 promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelin repair through autocrine pleiotrophin signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e155096 (2022).

Marce-Grau, A. et al. GNAO1 encephalopathy: further delineation of a severe neurodevelopmental syndrome affecting females. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 11, 38 (2016).

Guerrero-Valero, M. et al. Dysregulation of myelin synthesis and actomyosin function underlies aberrant myelin in CMT4B1 neuropathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2009469118 (2021).

Mack, J. T. et al. Skittish” Abca2 knockout mice display tremor, hyperactivity, and abnormal myelin ultrastructure in the central nervous system. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 44–53 (2007).

Chaya, T. et al. Identification of a negative regulatory region for the exchange activity and characterization of T332I mutant of Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor 10 (ARHGEF10). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29511–29520 (2011).

Poliak, S., Matlis, S., Ullmer, C., Scherer, S. S. & Peles, E. Distinct claudins and associated PDZ proteins form different autotypic tight junctions in myelinating Schwann cells. J. Cell Biol. 159, 361–372 (2002).

Xu, J., Berret, E. & Kim, J. H. Activity-dependent formation and location of voltage-gated sodium channel clusters at a CNS nerve terminal during postnatal development. J. Neurophysiol. 117, 582–593 (2017).

Barron, T., Saifetiarova, J., Bhat, M. A. & Kim, J. H. Myelination of Purkinje axons is critical for resilient synaptic transmission in the deep cerebellar nucleus. Sci. Rep. 8, 1022 (2018).

Kaeser, P. S. & Regehr, W. G. The readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 43, 63–70 (2017).

Schneggenburger, R., Meyer, A. C. & Neher, E. Released fraction and total size of a pool of immediately available transmitter quanta at a calyx synapse. Neuron 23, 399–409 (1999).

Wolff, J. J. et al. Altered corpus callosum morphology associated with autism over the first 2 years of life. Brain 138, 2046–2058 (2015).

Galvez-Contreras, A. Y., Zarate-Lopez, D., Torres-Chavez, A. L. & Gonzalez-Perez, O. Role of oligodendrocytes and myelin in the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Brain Sci. 10, 951 (2020).

Kumar, A. et al. Alterations in frontal lobe tracts and corpus callosum in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Cereb. Cortex 20, 2103–2113 (2010).

Graciarena, M., Seiffe, A., Nait-Oumesmar, B. & Depino, A. M. Hypomyelination and oligodendroglial alterations in a mouse model of autism spectrum disorder. Front Cell Neurosci. 12, 517 (2018).

Kim, J. H., Kushmerick, C. & von Gersdorff, H. Presynaptic resurgent Na+ currents sculpt the action potential waveform and increase firing reliability at a CNS nerve terminal. J. Neurosci. 30, 15479–15490 (2010).

Cherchi, F., Bulli, I., Venturini, M., Pugliese, A. M. & Coppi, E. Ion channels as new attractive targets to improve re-myelination processes in the brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7277 (2021).

Paez, P. M. & Lyons, D. A. Calcium signaling in the oligodendrocyte lineage: regulators and consequences. Annu Rev. Neurosci. 43, 163–186 (2020).

Peters, C. et al. Voltage-gated ion channels are transcriptional targets of sox10 during oligodendrocyte development. Cells 13, 1159 (2024).

Chen, S., Ren, Y. Q., Bing, R. & Hillman, D. E. Alpha 1E subunit of the R-type calcium channel is associated with myelinogenesis. J. Neurocytol. 29, 719–728 (2000).

Mason, E. R. et al. Resurgent and gating pore currents induced by de novo SCN2A epilepsy mutations. eNeuro, https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0141-19.2019 (2019).

Jang, M., Gould, E., Xu, J., Kim, E. J. & Kim, J. H. Oligodendrocytes regulate presynaptic properties and neurotransmission through BDNF signaling in the mouse brainstem. Elife 8, e42156 (2019).

Nguyen, A. O., Binder, D. K., Ethell, I. M. & Razak, K. A. Abnormal development of auditory responses in the inferior colliculus of a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. J. Neurophysiol. 123, 2101–2121 (2020).

Rotschafer, S. E. & Razak, K. A. Auditory processing in fragile x syndrome. Front Cell Neurosci. 8, 19 (2014).

Pang, R. et al. Transient hearing abnormalities precede social deficits in a mouse model of autism. Behav. Brain Res 437, 114149 (2023).

Pacey, L. K. et al. Delayed myelination in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet 22, 3920–3930 (2013).

Malara, M. et al. SHANK3 deficiency leads to myelin defects in the central and peripheral nervous system. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 79, 371 (2022).

Bacmeister, C. M. et al. Motor learning promotes remyelination via new and surviving oligodendrocytes. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 819–831 (2020).

Curtis, M., Garbelli, R. & Uva, L. A hypothesis for the role of axon demyelination in seizure generation. Epilepsia 62, 583–595 (2021).

Kulinich, A. O. et al. Beneficial effects of sound exposure on auditory cortex development in a mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 134, 104622 (2020).

Ali, F. et al. Inhibitory regulation of calcium transients in prefrontal dendritic spines is compromised by a nonsense Shank3 mutation. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 1945–1966 (2021).

Hao, Y. et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573–3587 e3529 (2021).

Cao, J. et al. The single-cell transcriptional landscape of mammalian organogenesis. Nature 566, 496–502 (2019).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Carbon, S. et al. AmiGO: online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinforma. (Oxf., Engl.) 25, 288–289 (2009).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D638–D646 (2023).

Villanueva, R. A. M. & Chen, Z. J. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis (2nd ed.). Meas.: Interdiscip. Res. Perspect. 17, 160–167 (2019).

Bean, B. P. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 451–465 (2007).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Manzoor Bhat (UTHSCSA) for providing reagents, insightful discussion, and technical assistance. We also thank Drs. Kevin Bender (UCSF) and Shin Kang (Temple) for providing transgenic mice. We thank Drs. Jason Pugh and Michael Roberts for providing comments on the manuscript. National Institutes of Health, NIDCD, R01DC018797 (JHK). National Institutes of Health, NIDCD, R01DC019371 (JHK)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.H.K. Methodology: H.G.B., W.C.W., K.N., E.G., and J.H.K. Investigation: H.G.B., W.C.W., K.N., E.G., and J.H.K. Visualization: H.G.B., W.C.W., K.N., and J.H.K. Supervision: J.H.K. Writing—original draft: H.G.B., W.C.W., and J.H.K. Writing—review & editing: H.G.B. and J.H.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sarah Ackerman, Minqing Jiang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article