Abstract

The development of photonic integrated components for the terahertz region has become an active and growing research field. Despite the numerous applications in this spectral range, hardware design still faces several challenges. We demonstrate an on-chip, active wavelength division multiplexer (WDM) operating at THz frequencies (> 1 THz). The WDM architecture is based on an inverse design topology optimization applied to an active quantum cascade heterostructure embedded in a double metal cavity and planarized with a polymer. Such an approach enables the fabrication of a strongly subwavelength device, with a normalized volume of V/λ3 ≃ 0.5. The WDM input is coupled to an integrated THz quantum cascade laser (QCL) frequency comb, providing three 330 GHz broadband output ports, ranging from 2.2 THz–3.2 THz, with a maximum crosstalk of -6 dB. The three ports are outcoupled via integrated broadband patch array antennas enabling surface emission. Such a device can also operate as a stand-alone element, unlocking advanced on-chip signal processing in the THz range.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

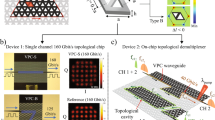

Wavelength division multiplexing and demultiplexing are essential functions in optics and electronics, allowing parallel communication and processing of complex signals1,2. In the field of integrated photonics, the development of advanced optical design techniques has allowed for unprecedented integration of several components into multi-functional photonic chips for telecommunications3,4 as well as for fundamental science5,6,7,8. The THz region of the electromagnetic spectrum has recently seen a rapid evolution thanks to the advent of advanced and efficient sources9,10,11,12,13, frequency combs14,15, and the birth of THz photonic integrated circuits16 that are being developed on different platforms17,18,19, including THz QCLs. In the sub-THz region (f < 500 GHz), a number of devices were first realized without on-chip capabilities20,21. Later, on-chip devices on silicon platforms were proposed22 and experimentally realized, using arrayed waveguide gratings23 and advanced topological photonics concepts24. In the present work, we target the THz (f > 1.5 THz) spectral region, where no devices have been demonstrated for the time being. For these higher frequencies, the use of a dielectric slab for vertical radiation confinement would lead to unpractical thicknesses of 20 μm or less; we propose then a different planar technology more adapted to the targeted wavelength range.

We recently developed an integrated active THz photonic platform25 based on planarized metallic waveguides, featuring an embedded quantum cascade gain medium capable of generating octave-spanning lasers26, broadband frequency combs operating both in the AM and FM regimes27, and also acting as an ultrafast detector28.

As well described in ref. 29, substrateless all-silicon microstructures represent an extremely promising platform for (sub-)THz photonics component integration. In this respect, our III-V metal-polymer-metal surely presents much less appealing figures in terms of propagation losses in passive waveguides and integrability; on the other side, the possibility to realize at will gain-endowed elements operating very efficiently from microwaves (10 GHz) to THz ( > 1.5 THz) yields great advantages for signal generation and manipulation. We believe that the two platforms are indeed complementary, since in any case THz and sub-THz generation happens mainly through III-V elements. The signal generation platform can be then efficiently coupled to silicon-based passive structures exploiting the planar geometry, or eventually integrated antennas. Our platform allows ultra-broadband operation due to the double metal waveguide geometry30,31 that presents no cutoff frequency for the fundamental TM00 mode; TM polarization, with the electric field perpendicular to the plane of the III-V crystal, is the one that couples to the intersubband transitions of the quantum cascade structures32. A wavelength division multiplexer (WDM) is an essential component to fully exploit the highly coherent comb sources27,33, allowing signal manipulation and routing directly on-chip. The layout of our planarized platform comprising parallel plate metallic waveguides provides a strong refractive index contrast between the metal-semiconductor metal active region (nMsM ≈ 3.6), and the passive, planarizing material, the benzocyclobutene (BCB) polymer (nBCB ≈ 1.6). Although not strictly required, this is beneficial for the exploitation of inverse design techniques34 for designing compact high-performance devices, translating the pioneering work of Piggott35 to 100 times longer wavelengths. A remarkable point of difference with what is already demonstrated in the near-IR is the fact that our WDM is an active device with gain, allowing us to compensate for propagation losses of the metal-insulator-metal waveguide that can be severe at these wavelengths ( ≈ 40 dB/cm25), as well as providing a useful knob for fine-tuning the device characteristics by introducing, for example, a supplementary modulation that can be exploited in laser stabilization schemes and, if implemented at RF frequencies, for spectral broadening.

Results

Inverse design and fabrication

The planarized platform we employ is particularly well suited for inverse design applications as the refractive index contrast between the dry-etched, high aspect-ratio active structures and the passive material sandwiched between two metals (see inset Fig. 1) allows for a relatively simple parametrization of the devices, requiring only two discrete values for the material refractive index. The topology-optimized36,37 device design presented in this work has been obtained with SPINS38, an inverse design software for running gradient-based optimization with the adjoint method34,39. The design problem requires a parametrization of the spatial material permittivity distribution ϵ(p), a sequence of forward and adjoint electromagnetic simulations, and an objective function fobj, i.e., the figure of merit used to evaluate the performance of a given intermediate design. At each step of the optimization problem, the objective function and its gradient are evaluated, iteratively updating the topology until converging at the optimal design.

In particular, we use SPINS to design a THz WDM with a 200 μm × 200 μm compact footprint and 40 μm wide input and output waveguides, routing frequencies in the 2.2 THz—3.2 THz range to three broadband output ports. Figure 1a shows the simulation region setup. The light gray square represents the design region where the permittivity is allowed to change, while the dark gray rectangles indicate the input and output waveguides.

The refractive index of GaAs (nGaAs ≈ 3.6, dispersive) and BCB (nBCB = 1.57, constant), a low-loss (3 cm−1 = 13 dB/cm) polymer commonly employed in optoelectronics for planarization, are the upper and lower bounds set for the discrete parametrization of the permittivity distribution. Due to the symmetric planarized waveguide structure with metallic confinement, the propagating optical waves have virtually no dependence along the vertical axis, meaning that only a 2D slice of the structure and an in-plane propagation simulation are required, resulting in a low computational load and a very efficient optimization routine. We defined a broadband objective function as the sum of one sub-objective per optimization frequency (ωi), maximizing the transmission to the desired port. Rejection of unwanted frequencies is not explicitly included in the figure of merit. Therefore, the objective function adopted for the presented optimization can be written as

where Ej(p) is the electric field at frequency ωj simulated with the parametrized permittivity distribution ϵ(p) and the quantity \(({\xi }_{i,j}^{{{\dagger}} }{{{{\bf{E}}}}}_{j})\) represents the overlap integral used to evaluate the coupling efficiency to the desired output mode ξj at port i.

The source injects the fundamental TM00 mode at the input waveguide. The transmitted power is computed as the squared overlap integral of the simulated electric field with the TM00 mode at the output waveguides.

Figure 1 shows the optimized design obtained after 105 iterations and the simulated power flow through the structure at the central frequency of each port.

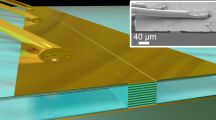

The devices were fabricated following the standard procedure described in ref. 25: we employed a broadband active region, similar to the one reported in ref. 40. This active region features a very broad spectral coverage (2.35–4.00 THz25) as well as a low threshold current density, making it extremely suited as a source for testing the operation of our broadband, three-port WDM. Images of the device through different stages of fabrication are reported in Fig. 2, together with an illustration of the full structure. The lasing cavity connects to the central body of the WDM via a short passive waveguide shaped as an adiabatic tapered transition for minimizing reflections. While providing efficient optical coupling, it also allows the electrical separation of the two active sections thanks to a lithographically defined V-shaped gap in the top metallization. The three ports are outcoupled through spatially separated surface-emitting broadband patch array antennas providing excellent beam properties (both an efficient extraction and a well-defined direction) to couple the laser to a user-defined external device or detector. As presented in more detail in refs. 41,42, the emission mechanism is based on an array of metallic patch elements oscillating in phase (similar to a dipole emitter array), resulting in a narrow single-lobed beam in the vertical direction. The emitted radiation exhibits a near-linear elliptical polarization along the direction of the feeding lines connecting the patches. Further optimization of the antennas would eventually enable a polarization selection of the output (together with the WDM spectral one), enable external cavity configurations43,44, or even employ inverse design on the antenna shape for custom emission properties, such as optical vortex beams45. A broadband time-domain 3D numerical simulation of the entire device structure, comprising QCL and WDM sections (without outcoupling antennas) was performed with CST Studio Suite to predict the performance of the system (see Fig. 2d). The results of this simulation do not include the frequency-dependent antenna response and reflectivity.

a Illustration of the planarized device structure with the active material surrounded by BCB. The device combines two sections: a 2.5 mm long lasing cavity and an electrically separated WDM section with surface-emitting broadband patch array antennas. b SEM image of the dry-etched WDM inverse-designed region before planarization. c Optical microscope image of a fully fabricated device. d 3D CST numerical simulation results for the transmission of the QCL section output to the WDM output ports.

Measurements

First, we test the emission of the device by collecting the signal from the ensemble of the three antennas together and comparing it with the signal emitted from the device’s rear cleaved facet, where there is no spectrally selective element (see Fig. 3). The rear facet spectrum is much broader, covering the 2.65–4.00 THz bandwidth, with an FSR of 15.65 GHz matching the cavity length (2.5 mm) of the QCL section. The output of the three antennas instead covers the bandwidth 2.65–3.30 THz, as expected from the optimization and simulation with SPINS. Unfortunately, the measured emission spectrum is slightly blue-shifted with respect to the intentionally designed active region bandwidth, as it does not extend to lower frequencies (below 2.6 THz) that would be routed into port 4. As a consequence, we expect only some low-intensity, unfiltered broadband emission from port 4.

In order to evaluate the performance of the WDM experimentally, a spatial filter (a 1 mm diameter hole within a 10 × 10 mm metallic plate frame) is positioned inside the cryostat in front of each antenna by means of a piezoelectric controller, allowing the collection of the signal from the individual ports. A detailed description and pictures of the measurement setup can be found in the Supplementary Material. The results of the measurements normalized to the maximum emission per port are reported in Fig. 4. The output of ports 2 and 3 follow with good agreement the prediction, displaying a maximum crosstalk of -6 dB. Port 4, centered at 2.37 THz, shows an attenuated signal since the laser output spectral emission does not cover the targeted bandwidth, as visible from Fig. 3. This experimental configuration also allows us to test the amplifying characteristics of the WDM. Being electrically isolated from the laser, the WDM can be biased independently and act as an amplifier for the emitted radiation in each channel. We report in Fig. 5a the integrated emitted power per port: it is clearly visible that the amplification shows a threshold at 6 V and reaches its maximum (saturates) for an applied bias of 9 V, in very good agreement with what was observed on the LIV curve of the laser (Fig. 5b), where the rollover point is reached at the same bias. The maximum amplification, with a factor of almost 3.5-times (5.4 dB), is achieved for port 2. This is an indication of the higher gain of the active region (biased at 9 V) at the frequencies transmitted to port 2, confirmed by the higher integrated spectral output power of this port (see Fig. 4), followed by port 3 and finally port 4.

a Spectral output collected individually from each port. The red stars correspond to the measured points in (b). The spectra are offset in the vertical direction for clarity without rescaling, showing the actual strength of the detected signal. b Normalized experimental spectral output for the three WDM ports together with the corresponding prediction from the CST 3D simulation. The measurements were done at 20 K, while the laser was operated in continuous-wave at 9.4 V and the WDM section was biased at 8.5 V.

a Spectrally integrated emission signal (stars) for each port as a function of the WDM applied bias. The QCL output power (dashed line) as a function of the QCL applied bias is shown for comparison of the threshold and peak output power voltages with the values for the threshold and maximum amplification of the WDM. The resemblance is clear, as the two sections are made of the same active material, featuring the same gain. b L-I-V curve of the laser while driven at 20 K in the micro-pulse (500 kHz, 5% duty cycle), macro-pulse mode (30 Hz, 50% duty cycle), with the WDM unbiased.

Additionally, we investigate the coherence of the laser emission over the frequency range where the spectral bandwidths of the laser and of the WDM overlap. While operating the QCL in free-running mode, we observe a single strong RF beatnote over a wide fraction of the laser dynamic range (see Fig. 6a, b), indication of a frequency comb operation26. The measurements show some instability arising in a narrow voltage interval below 8 V when the WDM is operated in its amplification regime. Nevertheless, the QCL is overall unaffected by the demultiplexer section, which suggests that the latter introduces weak feedback in the laser cavity. In order to fully characterize the coherence properties of the emission, we employ a SWIFTS14 setup described in the Supplementary Material and equipped with a fast Schottky detector (f\({}_{\max } < 30\) GHz). We operate the laser under +10 dBm RF injection at a frequency of 7.87 GHz, equal to half the cavity roundtrip frequency. We observe coherent comb operation over a bandwidth of ≃ 250 GHz with frep = 2finj = 15.65 GHz, covering channels 2 and 3. As shown in Fig. 6d, the time reconstruction of the QCL output after the WDM splitting appears as an oscillating periodic signal. This waveform is a consequence of the mixed AM and FM nature of the frequency comb, as suggested by the reconstructed intermodal phase difference.

a, b Electrical measurements of the beatnote of the QCL obtained at 20 K, sweeping the voltage of the laser in the two different operating regimes of the WDM: a without amplification, biased at 3 V; b with amplification, biased at 8 V. c Experimental SWIFT spectroscopy measurement. The laser is operated at 7.9 V (105 mA), at 20 K. The spectral product and the SWIFT spectrum overlap where the signal of the Schottky is above the noise floor. The intermodal phase differences are displayed on top for this spectral region. d The reconstructed temporal intensity profile (blue area) and the one corresponding to the same spectrum with Fourier-limited pulses (dashed black line) are compared.

We investigated as well the stability of the comb operation with respect to the WDM bias. We report the electrical beatnote signal as a function of the applied bias to the laser section for two different WDM biases VWDM = 3.0 V (see Fig. 6a) corresponding to a lossy regime and VWDM = 8.0 V (see Fig. 6b), corresponding to the amplification regime. The beatnote map has some minor changes but the majority of the comb regime is preserved for any bias of the WDM section (see Supplementary Material for more measurements). This demonstrates the very good optical isolation between the two sections, allowing a refined control on the performance of the device when operating as a frequency comb.

Discussion

Leveraging the advanced inverse design techniques developed at telecom wavelengths and adapting them to the ultra-broadband planarized waveguide platform for THz and microwave photonics, we demonstrate an active, three-channel WDM integrated on-chip with a THz QCL comb. In this first demonstration, such a device allows the extraction of 200 GHz-wide channels with reasonably low cross-talk below -6 dB. The extracted laser modes are phase-coherent, as proved by SWIFTS measurements, and robust against WDM bias point. This new class of devices paves the way for many applications, such as integrated THz signal processing, broadband THz spectroscopy, and coherent THz telecommunications, as recently demonstrated at telecom frequencies46,47 using frequency combs. The key highlight of the inverse design approach is the possibility of easily optimizing for different material platforms. Additionally, the planarized double metal configuration could allow for versatile integration with various devices, by using antennas and facilitating signal transfer for next-generation integrated photonic systems.

Methods

Device fabrication

The laser chips were fabricated from MBE-grown wafers of the active material, consisting of a strongly diagonal, low-threshold broadband GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure. The fabication process starts with the evaporation of a metallic stack on the sample and on a n+ GaAs substrate. The two are bonded via thermocompression wafer bonding. The active region is exposed after polishing and wet-etching. Then, a dry-etching step is needed to define the active waveguides. Planarization of the sample with BCB polymer follows and finally the definition of the electrical contacts is done to finish the fabrication process. More details on the fabrication are discussed in the Supplementary Material.

Experimental methods

The laser was operated at 20 K in continuous-wave mode, using a Keithley 2420 source, or in pulsed mode with an Agilent 8114A pulse generator. Additional microwave modulation was supplied using a Rohde&Schwarz SMB 100A microwave signal generator in combination with a Mini-Circuits ZVE-3W-183+ microwave amplifier. The laser emission spectra were obtained using a Bruker Vertex 80v, a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR) with a room-temperature deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector. A home-built FTIR spectrometer with a room-temperature DTGS detector in combination with amicrocamera was employed for the measurements of the filtered emission of the isolated WDM output channels. SWIFT spectroscopy measurements were carried out with a Schottky diode working as a fast detector at room temperature. The beatnote signal was collected at the FTIR output and fed into a Rohde&Schwarz FSW67 RF spectrum analyzer with an IQ demodulator function. More details can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Stern, B. et al. On-chip mode-division multiplexing switch. Optica 2, 530–535 (2015).

Dong, P. Silicon photonic integrated circuits for wavelength-division multiplexing applications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 22, 370–378 (2016).

Yamada, K. et al. High-performance silicon photonics technology for telecommunications applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 15, 024603 (2014).

Shekhar, S. et al. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 751 (2024).

Kim, J.-H. et al. Hybrid integration methods for on-chip quantum photonics. Optica 7, 291–308 (2020).

Metcalf, B. J. et al. Quantum teleportation on a photonic chip. Nat. Photon. 8, 770–774 (2014).

Mahmudlu, H. et al. Fully on-chip photonic turnkey quantum source for entangled qubit/qudit state generation. Nat. Photon. 17, 518+ (2023).

Griesmar, J. et al. Superconducting on-chip spectrometer for mesoscopic quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043078 (2021).

Lewis, R. A. A review of terahertz sources. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 47, 374001 (2014).

Ding, Y. J. Progress in terahertz sources based on difference-frequency generation. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 31, 2696–2711 (2014).

Bosco, L. et al. Thermoelectrically cooled THz quantum cascade laser operating up to 210 K. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 010601 (2019).

Khalatpour, A. et al. High-power portable terahertz laser systems. Nat. Photon. 15, 16–20 (2021).

Khalatpour, A. et al. Enhanced operating temperature in terahertz quantum cascade lasers based on direct phonon depopulation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 161101 (2023).

Burghoff, D. et al. Terahertz laser frequency combs. Nat. Photon. 8, 462–467 (2014).

Rösch, M. et al. On-chip, self-detected terahertz dual-comb source. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 17 (2016).

Sengupta, K., Nagatsuma, T. & Mittleman, D. M. Terahertz integrated electronic and hybrid electronic-photonic systems. Nat. Electron. 1, 622–635 (2018).

Xie, J. et al. A review on terahertz technologies accelerated by silicon photonics. Nanomaterials 11, 1646 (2021).

Rajabali, S. & Benea-Chelmus, I.-C. Present and future of terahertz integrated photonic devices. APL Photon. 8, 080901 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Terahertz topological photonics for on-chip communication. Nat. Photon. 14, 446+ (2020).

Karl, N. J. et al. Frequency-division multiplexing in the terahertz range using a leaky-wave antenna. Nat. Photon. 9, 717(2015).

Ma, J. et al. Frequency-division multiplexer and demultiplexer for terahertz wireless links. Nat. Commun. 8, 729 (2017).

Zhu, G. et al. Reverse design of on-chip terahertz demultiplexers. Micromachines 12, 1093 (2021).

Headland, D. et al. Gratingless integrated tunneling multiplexer for terahertz waves. Optica 8, 621–629 (2021).

Gupta, M. et al. 150 Gbps THz chipscale topological photonic diplexer. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309497 (2024).

Senica, U. et al. Planarized THz quantum cascade lasers for broadband coherent photonics. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 347 (2022).

Rösch, M. et al. Octave-spanning semiconductor laser. Nat. Photon. 9, 42–47 (2015).

Senica, U. et al. Frequency-modulated combs via field-enhancing tapered waveguides. Laser Photon. Rev. 17, 2300472 (2023).

Micheletti, P. et al. Regenerative terahertz quantum detectors. APL Photon. 6, 106102 (2021).

Headland, D. et al. Terahertz integration platforms using substrateless all-silicon microstructures. APL Photon. 8, 091101 (2023).

Williams, B. S., Kumar, S., Callebaut, H., Hu, Q. & Reno, J. L. Terahertz quantum-cascade laser at λ ≈ 100μ m using metal waveguide for mode confinement. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 2124–2126 (2003).

Unterrainer, K. et al. Quantum cascade lasers with double metal-semiconductor waveguide resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 3060–3062 (2002).

Faist, J. et al. Quantum Cascade Lasers. (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Micheletti, P. et al. Terahertz optical solitons from dispersion-compensated antenna-coupled planarized ring quantum cascade lasers. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf9426 (2023).

Molesky, S. et al. Inverse design in nanophotonics. Nat. Photon. 12, 659–670 (2018).

Piggott, A. Y. et al. Inverse design and demonstration of a compact and broadband on-chip wavelength demultiplexer. Nat. Photon. 9, 374–377 (2015).

Jensen, J. S. & Sigmund, O. Topology optimization for nano-photonics. Laser Photon. Rev. 5, 308–321 (2011).

Christiansen, R. E. & Sigmund, O. Inverse design in photonics by topology optimization: tutorial. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 38, 496–509 (2021).

Su, L. et al. Nanophotonic inverse design with SPINS: software architecture and practical considerations. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 011407 (2020).

Lalau-Keraly, C. M. et al. Adjoint shape optimization applied to electromagnetic design. Opt. Express 21, 21693–21701 (2013).

Forrer, A. et al. Photon-driven broadband emission and frequency comb RF injection locking in THz quantum cascade lasers. ACS Photon. 7, 784–791 (2020).

Bosco, L. et al. A patch-array antenna single-mode low electrical dissipation continuous wave terahertz quantum cascade laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 201103 (2016).

Senica, U. et al. Broadband surface-emitting THz laser frequency combs with inverse-designed integrated reflectors. APL Photon. 8, 096101 (2023).

Hugi, A., Maulini, R. & Faist, J. External cavity quantum cascade laser. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 25, 083001 (2010).

Wysocki, G. et al. Widely tunable mode-hop free external cavity quantum cascade laser for high resolution spectroscopic applications. Appl. Phys. B 81, 769–777 (2005).

White, A. D. et al. Inverse design of optical vortex beam emitters. ACS Photon. 10, 803–807 (2022).

Marin-Palomo, P. et al. Microresonator-based solitons for massively parallel coherent optical communications. Nature 546, 274–279 (2017).

Shu, H. et al. Microcomb-driven silicon photonic systems. Nature 605, 457–463 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from H2020 European Research Council Consolidator Grant (724344) (CHIC), EU project iFLOWS and SNF project 200021-212735 are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S. conceived the idea. V.D. and U.S. designed the device and performed inverse design optimization and electromagnetic simulations. V.D. and P.M. fabricated the device with support from U.S. M.B. grew the active region heterostructure. V.D. performed the measurements and data analysis. V.D. and G.S. wrote the manuscript with support from U.S. G.S. and J.F. supervised the project and acquired funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexander Piggott and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Digiorgio, V., Senica, U., Micheletti, P. et al. On-chip, inverse-designed active wavelength division multiplexer at THz frequencies. Nat Commun 16, 7711 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62557-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62557-5