Abstract

New tissues and organs in plants develop from stem cells located in meristematic tissues. Cell wall-mediated mechanics has been proposed to play crucial roles in controlling stem cell activity. Here, we show that in Arabidopsis shoot apical meristems (SAMs) Cellulose Synthase Like-D5 (CSLD5)-mediated cell wall synthesis modulates tissue mechanics. The Myb-domain transcription factor MYB3R4 directly activates CSLD5 expression, leading to robust new cell wall synthesis in dividing cells. CSLD5 forms complexes with CESAs to guide cellulose-based wall construction. Disruption of CSLD5 results in reduced wall stiffness and altered expression of touch-responsive genes. Confining CSLD5 to L1 layer cells restores the mechanical properties and growth defects of csld5 SAMs, indicating molecular and cellular compensation across shoot meristem layers. We further demonstrate that epidermal expression of OsCSLD4 in rice enhances inflorescence meristem growth and seed production. Our results suggest a principle for breeding high yield crops through cell-type specific cell wall remodelling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In plants, the active division and differentiation of stem cells and their progenitors drive the continuous formation of new tissues and organs1,2. Stem cell activity is regulated by both hormonal signals and environmental cues3. At the shoot apical meristem (SAM), auxin and cytokinin signaling pathways form a dynamic network that maintains stem cell homeostasis and directs organ formation4,5,6,7,8,9. Recent advances have highlighted the critical roles of mechanical forces in shoot meristem development10,11. For instance, cortical microtubules in the SAM cells align along the direction of maximal tensile stress and reorient in response to altered stress patterns induced by ablation or compression12. Mechanical signaling can further guide cell plate positioning, regulate organ formation, modulate the polarization of the auxin efflux carrier PIN1, and influence the expression of SHOOT MERISTEMLESS, a key regulator of stem cell activity13,14,15,16.

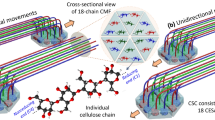

Biochemical and biomechanical signals converge at the cell wall to regulate cell and organ morphology17,18,19,20. The plant cell wall is predominantly composed of cellulose microfibrils, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin, and can be classified as primary or secondary depending on the timing of synthesis, tissue type, and cell extendibility21,22. Cell wall components are initially deposited at the end of cell division, strengthened during cell growth, and reorganized when plants encounter environmental stresses23,24. Cellulose consists of long chains of glucose molecules linked by β−1,4-glycosidic bonds and organized into highly ordered crystalline structures that confer strength and rigidity to the cell wall. Cellulose synthases (CESAs) are key enzymes responsible for cellulose synthesis25,26,27; they form large hexameric complexes known as the cellulose synthase complexes (CSCs), which move along microtubules to synthesize and project cellulose microfibrils through the plasma membrane28. Mutations in CESAs lead to various phenotypes, including abnormal cell shapes, reduced growth, and defective shoot meristem development10,26,27. In addition to CESA, the Arabidopsis genome encodes six cellulose synthase-like (CSL) families, namely CSLA, CSLB, CSLC, CSLD, CSLE, and CSLG29. Among these, CSLD proteins share the greatest amino acid similarity with CESAs. Microsomal membranes containing the primary cell wall CSLD proteins (CSLD2, CSLD3, and CSLD5) exhibited elevated mannan synthase activity30,31, while in vitro biochemical assays demonstrated that CSLD proteins possess β−1,4 glucan synthase activity32. Although the specific products of CSLDs in plant cells remain to be determined, the observations of shorter root hairs, reduced fertility, and dwarf phenotypes in csld mutants indicate broad roles for CSLD genes in tip-growing cells and other cell types33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

Here, we investigate the roles of CSLD family genes in shoot meristem development. Using a combination of in vitro biochemistry, in vivo live imaging, and biophysical measurements, we demonstrate that mutation of CSLD5 reduces cell wall stiffness and decreases cell division. Genetic analysis reveals that CSLD2, CSLD3, and CSLD5 are functionally interchangeable in regulating stem cell proliferation. Furthermore, expressing CSLD5 in the L1 layer under the control of the ATML1 promoter was sufficient to restore meristem defects in the csld5 mutant. Our results highlight the critical roles of CSLD-mediated cell wall synthesis in controlling stem cell growth, cell wall mechanics, and intercellular communication.

Results

Perturbation of cell wall homeostasis affects shoot meristem development

Cell wall synthesis and remodeling are primarily mediated by glycosyltransferases (GTs). Despite the large number of GT genes encoded by the Arabidopsis genome (~560; http://www.cazy.org), RNA sequencing and mRNA in situ hybridization assays have revealed that only a subset of GT genes are expressed in the shoot apical meristem, and their mRNAs accumulate in distinct domains and cell types40. To investigate the functions of cell wall synthesis in SAM development, we selected 29 meristem-expressed GT genes involved in the synthesis of various cell wall components (Fig. 1a). Among these genes, FUT1 exhibited high and homogeneous expression, representing Type 1 as defined in our previous study40; For Type 2 (flower primordial enrichment), we selected six genes from the GT families GT29, GT31, GT34, and GT77; CSLD5 and GALS2 are the only two genes grouped into Type 3 (expressed only in dividing cells); For Type 4 (expressed generally, but at higher levels in dividing cells), we analysed 19 genes belonging to six different GT families, including multiple GAUT and GATL members. Additionally, we analysed GATL6, which was grouped into Type 5 (provascular expression). The homozygous T-DNA insertion lines in the Col-0 background for each of these 29 GT genes, with insertion sites preferentially in an exon if available, were isolated, and the T-DNA insertions were confirmed by genotyping with gene-specific primers.

a GT mutants used for shoot apical meristem (SAM) analysis. The left panel shows a schematic representation of the organization of the cell wall. The primary cell wall in the meristematic cells mainly consists of cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and cell wall proteins that are typically modified with carbohydrate side chains. Mutants of each gene were selected based on their mRNA expression patterns. b Analysis of SAM size in the GT mutants. The size of the SAMs is determined by measuring the average of the radii of three successive primordia to the SAM center, and the results are displayed as box and whisker plots with individual data points. The error bars represent the maximum and minimum values. Center line, median; box limits, 25th and 75th percentiles. The color of the boxes correlates with the function of each gene in cell wall synthesis, as shown in (a). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, compared to Col-0). ns not significant. The exact P values are provided in the Source Data file.

Morphological analysis revealed that GT mutants, such as gals2 and xxt2, exhibited smaller plant sizes, while the majority of the other mutants appeared indistinguishable from wild-type (Supplementary Fig. 1a). 3D laser scanning confocal microscope images were collected for the SAMs of these mutants and subjected to quantitative analysis (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). The SAM size of most of the GT mutants was comparable to that of the wild-type (Col-0), suggesting functional redundancy or minor roles for the products. However, we observed slightly larger meristems in cslc8 that is defective in xyloglucan synthesis41, and irx10-l, irx14-l, and f8h mutants with reduced glucuronoxylan contents42. In contrast, csld5, xxt2, gaut9, gaut10, gals2, and gals3 plants exhibited smaller meristems compared to WT. The reduced meristem size in the xxt2 single mutant was consistent with the dominant activity of XXT2 in xyloglucan synthesis43. GAUTs encode galacturonosyltransferases that mediate pectin synthesis by transferring galacturonic acid from uridine 5’-diphosphogalacturonic acid to homogalacturonan. Glycosyl residue composition analysis had detected reduced GalA contents in the gaut9 and gaut10 single mutants44, which may contribute to the smaller SAMs observed in these two mutants. The β−1,4-galactosyltransferases GALS transfer Gal residues from UDP-Gal to β−1,4-galactopentaose, thus are involved in pectin rhamnogalacturonan I synthesis. The smaller meristems of gals2 and gals3 were in correlation with the reduced Gal contents in the single gals mutants45. Together, our genetic screening reveals that, in addition to cellulose and xyloglucan10,46, pectin and CSLD5 products, also contribute to shoot meristem growth.

CSLD5 mediates de novo cell wall formation

Pectin has been shown to control cell wall mechanics and meristem morphogenesis13, but the function of CSLD family enzymes in stem cell growth remains unclear. Among all the GT mutants analysed, csld5 exhibited the smallest SAMs (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2). To dissect the cellular basis of the defective meristem growth in csld5, we reconstructed 3D images of WT and csld5 SAMs. Quantification of the L1 layer cell size in MorphoGraphX47,48 revealed that cells of csld5 were much larger than those of WT (Fig. 2a). Cell enlargement in csld5 SAMs may suggest faster growth or delayed cytokinesis.

a Comparison of cell size in wild-type (WT, Col-0) and csld5 SAMs. The L1 (epidermal) cells were segmented in MorphoGraphX and shown as a heatmap. Scale bar, 50 µm. b Reduced cell division activity in csld5. Cells division was tracked using the plasma membrane marker myr-YFP (shown in blue). The cells that divide within a 24-h interval are labeled in magenta. Data represent means ± SD. n = 6 SAMs for WT and 6 SAMs for csld5. Scale bar, 50 µm. c Comparison of new cell wall morphology in wild-type (WT, Col-0), csld5, and csld2 csld5 SAMs. Left panels show the segmented L1 (epidermal) cells, with red lines labeling the newly formed cell walls within 24 h (for WT), 24 h (for csld5), or 24 and 72 h (for csld2 csld5). The projected cells are shown in the right panels, with the new walls indicated by stars. Note that there were no cell division in the csld2 csld5 double mutant in the first 24 h. Scale bar, 10 µm. d Analysis of cell growth in wild-type and csld5 SAMs. Heatmaps show the relative cell size increase over 12 h in the L1 cells, with a value of 1 indicating no growth. The growth rate of csld5 cells is reduced compared to that of wild-type cells. Scale bar, 50 µm. Boxplots (a, d) indicate median (box center line), 25, 75% (box), and the whiskers extend to the minima and maxima. ****P < 0.0001 (Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

CSLD5 has already been shown to be enriched in dividing cells40,49. Thus, we first investigated cell divisions in csld5 SAMs. We introduced the plasma membrane marker pUBQ10::myr-YFP into WT and csld5, and conducted time-lapse live imaging of the SAMs at 12-h intervals. Compared to WT, we found that new cell wall formation was delayed in csld5. Within 24 h, new cell walls were observed in 20% of the WT SAM cells, which was reduced to 12% in csld5 (Fig. 2b). It had been shown that csld5 exhibited cell wall stubs in root cortical cells, a phenotype further enhanced in the csld2 csld5 or csld3 csld5 double mutants49. Similar cell wall gaps were also present in the leaf epidermal cells of the maize csld1 mutant50. However, we found that such cell stubs are rare or absent in the SAM cells of csld5. Even in the csld2 csld5 double mutant with severe growth defect, the new cell walls remain intact in recently divided cells (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Movies 1–3), suggesting the shoot stem cells exhibit distinct responses to impaired wall synthesis compared to root or leaf cells.

Next, we investigated growth rates in clsd5 SAMs. Consistent with previous findings, in WT SAMs the cells at the peripheral zone (PZ) grow faster than those at the central zone (CZ) due to distinct wall elasticity at these regions13,51,52. In contrast, this heterogeneous growth pattern was lost in csld5, with most of the epidermal cells, particularly at the periphery, expanding less rapidly than those in WT SAMs (Fig. 2d). In addition to reduced overall expansion, the growth rates of csld5 were slightly more variable than those of the wild-type SAMs. However, this difference was not statistically significant, probably due to the variation between different SAMs (Supplementary Fig. 3). Together, these data demonstrate that the presence of larger cells in csld5 is not due to increased growth rate.

Based on these results, we propose that CSLD5 contributes to shoot meristem growth by promoting new cell wall synthesis in dividing cells. The perturbed growth map suggests an indirect impact of CSLD5-mediated de novo cell wall formation onto the growth of the SAM.

CSLD5 maintains cell wall mechanical integrity

As cell growth is influenced by the mechanical strength of the walls53,54, the decreased cell expansion rate in csld5 might suggest a reduction in wall extensibility. We thus employed atomic force microscopy (AFM) to examine the wall properties of WT and csld5 SAMs. We observed that the apparent Young’s modulus (EA) of the anticlinal walls in csld5 SAMs was greatly reduced compared to the wild type (Fig. 3a), indicating that the cell walls of csld5 were less stiff. To further verify the AFM measurements, we conducted osmotic treatments52,55,56. Compared to wild type, the csld5 cells showed more shrinkage in the presence of 0.4 M mannitol, suggesting soft walls (Fig. 3b). Along with the reduced cell wall stiffness, the csld5 SAMs consistently exhibited a more pointed shape compared to those of WT plants (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the stress originating from the inner tissues may exert pressure towards the surface layer, resulting in greater expansion in the axial direction than in the circumferential direction57,58. RNA sequencing revealed that 18.8% (117/622) of the genes downregulated in csld5 SAMs overlapped with the touch core transcriptome (Fig. 3d, e)59. Among these 117 touch genes, 22 belong to the top 51 most touch-induced genes60. These genes include the touch marker genes TCH2, TCH3, TCH4, as well as genes involved in Ca2+ signaling, ethylene activity, and hypoxia response (Fig. 3f). While the fertility and lignin content did not show significant difference, we observed an upregulation of immunity-related genes in csld5, potentially indicating a molecular response to cell wall defect (Supplementary Fig. 4)18. Together, our biomechanical and gene expression data suggest a role for CSLD5 in maintaining the mechanical properties of cell walls.

a Apparent Young’s modulus (EA) maps of the L1 cells of WT (n = 7) and csld5 (n = 6) SAMs, showing that the csld5 cell walls are softer. The data shown are normalized values using the wild-type SAMs as a reference. Scale bar, 20 µm. b Map of cell shrinkage of WT (n = 5) and csld5 (n = 6) SAMs after osmotic treatment. The dissected SAMs were imaged both before and after a 20-min treatment with 0.4 M mannitol. More shrinkage in clsd5 suggests soft walls. Boxplots (a, b) indicate median (box center line), 25, 75% (box), and the whiskers extend to the minima and maxima. ****P < 0.0001 (Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test). c Geometric shapes of WT (n = 12) and csld5 (n = 12) SAMs. The left panels show the Gaussian curvature of SAMs. The right panel shows the quantification of the curvature, which was estimated by fitting a parabola based on the longitudinal view of the SAMs. Scale bars, 50 µm. d Gene ontology (GO) analysis of differentially expressed genes in WT and csld5 shoot meristems. The colors indicate the significance of enrichment for each term, presented as “−log10 (p value)”. The sizes of the filled circles reflect the proportion of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each term. Note that genes involved in DNA binding were downregulated in csld5, suggesting feedback from cell wall defect to transcriptional reprogramming. Statistical significance was determined by hypergeometric test in R package clusterProfiler. e Venn diagram of the overlap between downregulated genes in csld5 and the touch core transcriptome28. f Comparison of touch-responsive gene expression in wild-type and csld5 SAMs by qRT-PCR in dissected WT and csld5 shoot apices. Data are presented as mean values ± SD of three independent replicates. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001). Experiments were repeated four times with different samples, giving similar results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Feedback from CSLD5-mediated wall synthesis to cell cycle machinery

CSLD5, along with GALS2, was among the only two GT genes showing cell cycle-regulated patchy pattern in our mRNA in situ hybridization screening40. CSLD5 expression could also be detected in the dividing cells of other tissue such as the root (Supplementary Fig. 5). Analysis of the CSLD5 promoter identified five mitosis-specific activator elements (MSA), which could be recognized by the MYB3R transcription factors in our previous chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) assays (Fig. 4a, b)61. We further validated the binding of MYB3R1 and MYB3R4 to the CSLD5 promoter by ChIP-quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA) assays (Fig. 4c–e). A dual-luciferase assay demonstrates that the promoter activity of CSLD5 was significantly enhanced in the presence of MYB3R1, MYB3R4, or both, suggesting that these transcription factors directly activate CSLD5 gene expression (Fig. 4f). This was confirmed by qRT-PCR and RNA FISH assays, showing that the expression levels of CSLD5 was substantially reduced in the myb3r1 myb3r4 double mutant (Fig. 4g, h).

a A schematic diagram of the CSLD5 genomic region, with colored circles indicating the positions of the MSA elements. “I” and “II” are the regions analysed by ChIPqPCR. b Genome browser tracks of MYB3R1 and MYB3R4 ChIP-seq coverage at CSLD5 genomic region. c ChIP-qPCR analysis to confirm MYB3R1 and MYB3R4 binding to the promoter regions of CSLD5. Data were presented as mean values ± SD of three independent replicates. d, e Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showing that MBP-MYB3R1 and MBP-MYB3R4 could bind to the Cy5-labeled DNA probes. f Dual-luciferase assay demonstrating transcriptional activation of CSLD5 by MYB3R1 and MYB3R4. n = 6 biological replicates, with error bars representing mean ± s.e.m. g Comparison of CSLD5 transcript levels in WT and myb3r1 myb3r4 SAMs by qRT-PCR. Data represent means ± SD, n = 3 biological replicates. h RNA FISH to compare CSLD5 mRNA expression in WT and myb3r1myb3r4 SAMs. i Expression patterns of pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD5 at the SAM. Scale bars, 20 µm (left two panels), 5 µm (right panel). j Time-lapse imaging of GFP-CSLD5 during cell division. Scale bar, 5 µm. k Partial co-localization of GFP-CSLD5 with VHA-RFP. Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) = 0.895 ± 0.006 (n = 60 ROIs from three individual SAMs). Scale bar, 5 µm. l, m RNA FISH to compare HIS4 (l, top panel) and CYCB1;2 (l, bottom panel) mRNA expression in wild-type and csld5 SAMs. Quantification of RNA FISH signals is shown in (m). Scale bar, 50 μm. n A schematic illustration of molecular events during cell division. o A proposed model of feedback between cell wall synthesis and cell cycle progression. Mutation of CSLD5 resulted in delayed cell plate formation and softer cell walls, which feed back to the cell cycle machinery, leading to cell cycle arrest at early mitosis. Boxplots (h, m) indicate median (box center line), 25, 75% (box), and the whiskers extend to the minima and maxima. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (c, f, g, m), ****P < 0.0001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Differently to its mRNAs, CSLD5 proteins were enriched in mitotic cells, but we could also detect some signals in interphase cells (Fig. 4i). Time-lapse imaging shows that CSLD5 proteins started to be translated from prophase onwards and accumulated at the developing cell plates at the end of mitosis (Fig. 4j), similarly to what has been observed in root and leaf dividing cells49. Upon completion of the new cell wall, CSLD5 proteins persisted in the cells for several hours (Fig. 4j). Non-cell plate-localized CSLD5 proteins formed a ring-like structure surrounding the VHA1-RFP-labeled trans-Golgi network (TGN) (Fig. 4k), reminiscent of CESA362 and rice OsCSLD463. The dynamic localization patterns of CSLD5 resemble those of primary cell wall CESAs64.

Cell growth and division are tightly coordinated65. While the expression of CSLD5 is controlled by cell division, we found that cell cycle progression was also affected in csld5. Compared to WT, the expression level of HIS4 mRNAs were much lower in csld5 SAMs, whereas the expression of CYCB1;2 was increased (Fig. 4l, m). HIS4 is a cell cycle marker gene that labels G1-S transition cells, and CYCB1;2 is only expressed at early prophase (Fig. 4n). Thus, we propose a scenario in which mutation in CSLD5 compromised cell wall synthesis, which in turn triggers reduced cell cycle progression, ultimately leading to cells arrested at early stages of mitosis before cell plate formation in csld5 (Fig. 4o).

CSLD5 directly interacts with CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6

Within the cellulose synthase superfamily, CSLDs exhibit the highest similarity to CESAs in their amino acid sequences29. All CESAs and some CSLDs, including CSLD2, CSLD3, CSLD4, and CSLD5, possess a conserved N-terminal RING-type zinc finger domain predicted to be involved in protein complex formation66. In agreement with this, we found that CSLD5 interacts with CSLD3 in yeast (Fig. 5a). Moreover, CSLD2 and CSLD3 were functionally interchangeable with CSLD5 in regulating meristem size and plant growth when expressed from a CSLD5 promoter (Fig. 5b–g).

a CSLD5 interacts with CSLD3 in yeast. The split-ubiquitin membrane yeast two-hybrid system was used to test the interaction between CSLD5 and CSLD3. CSLD5 was fused to the Nub fragment encoded in pXGY18, and CSLD3 was fused to the Cub fragment encoded in pXGY17. b Expression patterns of GFP-CSLD2 and GFP-CSLD3 under the control of CSLD5 promoter. GFP-CSLD2 and GFP-CSLD3 were highly expressed in actively proliferating cells when driven by the CSLD5 promoter. Scale bar, 50 µm. c Both GFP-CSLD2 and GFP-CSLD3 proteins localized to the cell plate, with similar subcellular dynamics to CSLD5. Scale bar, 5 µm. d–g The growth phenotype and 3D projections of the SAMs. The cell walls are stained using propidium iodide (PI) and shown in Grayscale. Quantification of the plant weight (e) and SAM size (g) demonstrates that expression of GFP-CSLD2, GFP-CSLD3, and GFP-CSLD5 under the control of the CSLD5 promoter fully restores csld5 mutant phenotypes. The plant weight represents the fresh weight of whole plants excluding the roots. SAM size was determined by measuring the average of the radii of three successive primordia to the SAM center. For plant weight, WT (n = 10), csld5 (n = 10), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD2 (n = 13), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD3(n = 12), and csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD5 (n = 11). For SAM size, WT (n = 10), csld5 (n = 9), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD2 (n = 8), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD3 (n = 12), and csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD5 (n = 16). Data represent means ± SD (e, g). Letters indicate statistically significant differences between the genotypes, as calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (P < 0.05). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In Arabidopsis, a CESA6 chimeric protein containing the CSLD3 catalytic domain could integrate into the CESA complexes (CSCs) and fully rescue the growth defects of the CESA6 null mutant prc1-132. Additionally, CSLDs have been recently shown to assemble to CSC-like rosettes and contribute to cellulose synthesis in Physcomitrium patens67. These findings suggest a functional link between these two classes of cell wall synthases. To explore the potential interactions between CSLD5 and CESAs, we conducted a yeast two-hybrid assay. Using the split-ubiquitin-based membrane yeast two-hybrid system, we detected strong interactions between CSLD5 and the primary cell wall CESAs CESA3 and CESA6 and a weak interaction between CSLD5 and CESA1 (Fig. 6a). To validate the interactions between CSLD5 and CESAs in planta, we co-expressed GFP-CSLD5 with FLAG-tagged CESA1, CESA3, or CESA6 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and performed co-immunoprecipitation assays. We found that all three CESAs could be coimmunoprecipitated with GFP-CSLD5 using a GFP-specific antibody (Fig. 6b), indicating physical association of CSLD5 with CESAs in both yeast and plant cells.

a CSLD5 interacts with CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 proteins in yeast. b CSLD5 interacts with CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 as detected by Co-IP assays. Unprocessed original scans of blots are shown in Source Data. c Co-localization of CSLD5 and CESA proteins. Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) = 0.763 ± 0.011 (n = 49 ROIs from five inoculated leaves) for GFP-CESA1, 0.587 ± 0.015 (n = 56 ROIs from three inoculated leaves) for GFP-CESA3, and 0.686 ± 0.012 (n = 54 ROIs from five inoculated leaves) for GFP-CESA6. Scale bars, 5 μm. d–f Subcellular localization of CSLD5 and CESA proteins in Arabidopsis root cells. The top panels show interphase cells, and the bottom panels show cells at late mitosis when the cell plates (indicated by arrows) are being formed. Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) = 0.601 ± 0.016 (n = 46 ROIs from five individual roots) for GFP-CESA1, 0.698 ± 0.013 (n = 65 ROIs from four individual roots) for GFP-CESA3, and 0.629 ± 0.013 (n = 48 ROIs from four individual roots) for GFP-CESA6. Scale bars, 5 μm. g The growth phenotypes (top panels) and 3D projections of the SAMs (bottom panels) of wild-type, csld5, and csld5 plants expressing GFP-CESAs. Scale bars: top panels, 2 cm; bottom panels, 50 µm. h, i Quantification of the plant weight (h) and SAM size (i). For plant weight, WT (n = 11), csld5 (n = 12), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA1 (n = 14), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA3 (n = 13), and csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA6 (n = 14). For SAM size, WT (n = 11), csld5 (n = 16), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA1 (n = 15), csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA3 (n = 13), and csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA6 (n = 12). j Immunofluorescence labeling of amorphous cellulose in WT and csld5 SAMs. The longitudinal sections of the shoot apex were incubated with non-crystalline cellulose antibody CBM4. n = 5 SAMs for WT and 5 SAMs for csld5. Data represent means ± SD (h–j). Significant differences between the genotypes were calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (P < 0.05) (h, i) and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05). Scale bar, 20 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we examined the cellular dynamics of CSLD5 and CESA proteins. In the N. benthamiana transient expression system, we observed partial co-localization between mCherry-CSLD5 and GFP-CESA1, GFP-CESA3, or GFP-CESA6 in some of the presumed Golgi stacks (Fig. 6c). However, these cells are not dividing, questioning the relevance of CLSD5 in the SAM. We thus generated stably transgenic plants co-expressing mCherry-CSLD5 with GFP-CESA1, GFP-CESA3, or GFP-CESA6. Consistent with previous reports49, CSLD5 decorated the cell plates together with CESA3, and this co-localization on the cell plate was also evident between CSLD5 and CESA1 or CESA6. Substantial overlap of CSLD5 and CESA proteins was also observed in the Golgi stacks (Fig. 6d–f). Together, these data suggest a direct interaction and co-localization of CSLD5 with the primary cell wall CESAs.

To investigate the functional relationship between CSLD5 and CESAs, GFP-tagged CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 were expressed in the csld5 mutant under the control of the CSLD5 promoter. While CESA1 had minimal effects on csld5 growth, the csld5;pCSLD5::GFP-CESA6 plants exhibited severely stunted growth (Fig. 6g–i), resembling the phenotypes of the csld2 csld5 double mutant31 or cesa high-order mutants26, suggesting that ectopic expression of CESA6 in dividing cells may disrupt the normal functions of the CSC or CESA-CSLD complexes. By contrast, GFP-CESA3 was found to largely rescue the growth defect of csld5 (Fig. 6g–i), indicating that CESA3 is functionally equivalent to CSLD5 in controlling SAM growth and plant development.

Both molecular and genetic assays suggest an involvement of CSLD5 in the synthesis of cellulose or cellulose-like wall materials. In support of this, an immunolabelling assay using the cellulose-binding module CBM468 showed a great reduction in the content of amorphous cellulose in csld5 SAMs (Fig. 6j). Taken together, although the activities of CSLD5 in the biosynthesis of xylan and pectin cannot be excluded36,69, our data, along with the findings that CSLD5 expression is induced by isoxaben habituation70 and that CSLD3 acts as a UDP-glucose-dependent β−1,4 glucan synthase32, suggest that CSLD5 has similar functions to CESAs, at least to CESA3, in the construction of cellulose-based cell walls. Therefore, we propose that CSLD5 directly contributes to de novo cell wall formation and cell cycle progression by synthesizing cellulose-based new wall materials. This, in turn, indirectly influences the mechanical reinforcement of the walls during maturation, ultimately leading to inhibited cell growth and smaller SAMs in the csld5 mutant.

Expressing CSLD5 in L1 cells restores wall mechanics and shoot meristem growth

Our data so far has established CSLD5 as a contributor to new wall synthesis in dividing cells at the shoot meristem, with an impact on the growth of the rest of the SAM. To explore this non-cell autonomous effect of CSLD5 on growth, we investigated whether ectopic expression of CSLD5 would also impact SAM growth. When GFP-CSLD5 proteins were expressed throughout the SAM under the control of the RPS5A promoter71, we found that they only partially rescued the smaller SAMs and growth defects of csld5 (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that cell wall-mediated interlayer or intercellular coordination of growth may indeed exist in the actively proliferating meristematic tissues.

To test this hypothesis, we confined CSLD5 expression to the epidermis by using the ATML1 promoter72,73. The pATML::GFP-CSLD5 construct was transformed into the csld5 mutant background. As the ATML1 promoter has been reported to be sometimes active in the L2 layer74, we selected only those lines with L1-restricted expression for further analysis. RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b) and confocal microscopy analysis (Fig. 7a, b) revealed that both GFP-CSLD5 mRNAs and the cognate proteins were detected specifically in the L1 cells of the SAM. We found that the SAM and plant size of csld5 were all fully rescued by the L1-expressed GFP-CSLD5 (Supplementary Fig. 7c–f). By segmenting the csld5;pATML::GFP-CSLD5 SAM cells, we show that the enlarged L1 cells of csld5 were restored to wild-type levels (Fig. 7c). Moreover, quantification of cell size in the L2 layer also showed full complementation (Fig. 7d). In addition to cell size, the number of cells in both L1 and L2 layers were greatly increased in the csld5;pATML::GFP-CSLD5 SAM plants, which were even more than those of the wild-type SAMs (Fig. 7e, f). Thus, expression of CSLD5 in the epidermal cells fully restored the cell growth and proliferation defects of the csld5 mutant.

a Confocal microscopy analysis to show the top views of the SAMs expressing pATML1::GFP-CSLD5. The cell walls were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and shown in magenta. GFP signals are shown with the Fire look-up table. Scale bar, 50 µm. b Side views of the SAMs, indicating the specific expression of pATML1::GFP-CSLD5 in the L1 cells. Scale bars: left panels, 50 µm; right panels, 10 µm. c, d Quantification of the size of cells in the L1 (c) and L2 (d) layers of the SAMs of WT, csld5, and csld5;pATML1::GFP-CSLD5 plants. The cells were segmented in MorphoGraphX and shown as heatmaps (top panels). The projections of the cells are shown in the bottom panels. Scale bars, 20 µm. e, f Quantification of the number of cells in the L1 (e) and L2 (f) layers of the SAMs. In both layers, the csld5;pATML1::GFP-CSLD5 SAMs contain more cells than those of WT and csld5, indicating a non-cell-autonomous over-compensation effect. n = 4 SAMs for each genotype. g Hierarchical clustering of the 117 CSLD5-related touch genes in WT, csld5, and csld5;pATML1::GFP-CSLD5 SAMs. The expression for most of these genes was restored to wild-type levels by epidermal GFP-CSLD5. Three biological replicates, each containing 24 shoot apices, were analysed for gene expression. The repeats of each genotype are shown in separate columns. Boxplots indicate median (box center line), 25, 75% (box), and the whiskers extend to the minima and maxima in (c–f). Letters indicate statistically significant differences between the genotypes, as calculated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (P < 0.05). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

RNA sequencing analysis indicates that the transcriptome changes in csld5 SAMs were broadly restored to WT in the csld5;pATML::GFP-CSLD5 plants (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Specifically, 79.5% (93/117) of the CSLD5-maintained and touch-responsive genes, including mechanosensitive genes upregulated in the gip1gip2 mutant with stiffer nuclei75, were restored to wild-type levels by L1-expressed CSLD5 (Fig. 7g and Supplementary Fig. 8b). In line with this molecular and cellular complementation, AFM measurement showed that the csld5;pATML::GFP-CSLD5 SAMs were stiffer than csld5 alone (Supplementary Fig. 8c), indicating that the mechanical property was also restored. Together, these results suggest that CSLD5-mediated cell wall synthesis can act in a non-cell autonomous manner to regulate cellular activity in the inner layer cells and promote SAM growth.

Epidermis-specific expression of OsCSLD4 promotes inflorescence meristem growth and seed production in rice

In the quantitative analysis, we noticed that expression of GFP-CSLD5 in L1 cells not only rescued csld5 growth defects, the csld5;pATML::GFP-CSLD5 plants and SAMs were even larger than those of the wild-type Col-0 (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). This observation suggests that cell wall remodeling in the epidermis could be a potential strategy to enhance shoot meristem activity and overall plant growth. To test this hypothesis, we turned to the cereal crop rice (Oryza sativa). The rice CSLD5 orthologue, OsCSLD4, is known to be expressed in dividing cells and essential for plant growth63,76. We expressed GFP-OsCSLD4 in the wild-type Zhonghua 11 (ZH11) background under the control of the epidermis-specific ROC1 promoter77. RNA FISH (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b) and confocal imaging (Fig. 8a) confirmed that both GFP-OsCSLD4 mRNA and proteins were restricted to the epidermal cells.

a Confocal microscopy analysis showing the specific expression of pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 in the epidermal cells of the rice inflorescence meristem. GFP signals are shown with the Fire look-up table. Scale bar, 100 µm. b Growth morphologies of wild type (ZH11) and two independent pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 transgenic lines. The pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 plants have more tillers as compared to ZH11. Scale bar, 10 cm. c Expression of GFP-OsCSLD4 in L1 cells enhances panicle growth. The number of panicle branches, particularly the secondary branches, is increased in pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 plants. Scale bar, 3 cm. d–g Quantitative analysis of the numbers of tillers (n = 11 for ZH11, 9 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #1, and 11 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #2) (d), primary (n = 54 for ZH11, 54 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #1, and 54 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #2) (e), and secondary (n = 93 for ZH11, 54 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #1, and 60 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #2) (f) panicle branches, and seeds per panicle (n = 57 for ZH11, 33 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #1, and 45 for pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 #2) (g) in WT and pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 plants, showing that rice agronomic traits are improved by epidermally expressed GFP-OsCSLD4 in the shoot meristem. Data represent means ± SD. Significant differences between samples were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (**P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The shoot meristems of the pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 plants were larger than those of the wild-type plants and exhibited higher levels of HIS4 expression (Supplementary Fig. 9c), indicating stronger cell division activity. These transgenic plants were of similar height to WT (Supplementary Fig. 9d, e) but produced more tillers, suggesting enhanced axillary meristem activity (Fig. 8b, d). While the length of the pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 panicles was comparable to that of the wild-type plants (Supplementary Fig. 9f), both primary and secondary branch numbers were increased (Fig. 8c, e, f). Consequently, the pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 panicles generated more seeds than the ZH11 control (Fig. 8g). Interestingly, the seed weight of pROC1::GFP-OsCSLD4 plants was indistinguishable to ZH11 (Supplementary Fig. 9g), suggesting that epidermal OsCSLD4 expression does not trigger a compensatory effect to interfere with seed development.

Discussion

Plant cell growth is a complex process that involves active deposition of new cell wall materials to accommodate wall expansion and strengthening20,21,22,23. Given their crucial roles in plant development, cell wall biosynthesis and remodeling are tightly regulated. During cellulose synthesis, the cellulose synthase complexes sit within the plasma membrane and deposit cellulose directly to the cell wall, guided by the cortical microtubules28. As the cortical microtubules align in the direction of maximal tensile stress12, mechanical stresses thus guides cell wall assembly, and the wall properties in turn feed back to tissue mechanics78. We show that, in the actively proliferating shoot meristem, CSLD5 protein participates alongside CESA proteins within the CSCs to drive cellulose-based new wall synthesis. MYB3R4 activation of CSLD5 expression, together with cytokinin-triggered MYB3R4 nuclear shuttling61, enables transient production of a large amount of CSLD5 proteins within a few minutes, allowing for rapid and highly efficient new cell wall building at the end of mitosis. Feedback from CSLD5 to cell division control supports the concept that cell wall synthesis and cell plate formation are components of the cell cycle progression21.

Recent studies have revealed that CSLD proteins, similar to CESAs, assemble into plasma membrane rosettes, exhibit β−1,4 glucan synthase activity, and contribute to cellulose microfibril synthesis32,67. Based on the observed physical interactions and functional complementation between CSLD5 and CESAs, we propose that these proteins may form chimeric CESA-CSLD heterocomplexes responsible for wall construction and integrity maintenance in the shoot meristems. The CSLD5-CESA heterocomplex represents a cell wall synthesizing machinery distinct from classic CSCs. While CESA3 may share similar catalytic or regulatory domains with CSLD5, thus can integrate into the CSLD5 complex, CESA1 and CESA6 appear to lack these domain-specific features, rendering them unable to functionally substitute for CSLD5. Additional experiments, such as domain-swapping between CSLD5 and CesAs, will help to clarify these possibilities.

The specific expression of CSLD5 in mitotic cells, along with the dynamic localization of CSLD5 proteins to the new cross walls, suggests that CSLD5 primarily functions to promote de novo cell wall formation, influencing wall maturation and mechanics. In csld5, delayed cell plate assembly prolongs cell cycle progression and reduces the proliferative activity, resulting in fewer, larger cells. Although the newly formed walls in csld5 appear morphologically intact, they may exhibit compositional or structural defects. As these defects propagate with wall aging, they lead to a global reduction in cell wall stiffness.

Intercellular communication between distinct cell layers is crucial for plant morphogenesis. At the SAM, disruption of the L1 epidermal layer through microsurgical laser ablation led to a loss of meristem identity and altered cell division patterns in the underlying L2 layer79, and similar meristem defects were observed in the atml1/pdf2 mutant or the DEK1 RNAi plants80. Over-expression of the CDK inhibitors KRP1/ICK1 and KRP4 in the epidermis resulted in fewer and larger cells, but this perturbation of the L1 did not affect cell numbers in the inner layers81. In contrast, we found that expression of CSLD5 in the L1 fully restored the growth defects of the csld5 SAMs, and the complementation occurs not only in L1 but also in L2 cells, suggesting that CSLD5-mediated cell wall synthesis regulates cell development across layers of the SAM. Interlayer coordination was also observed for the BR-mediated growth response: L1-specific expression of the BR receptor BRI1 or the BR biosynthesis enzyme CPD in bri1 and cpd mutants, respectively, could greatly rescue the cell size defect in both the epidermis and the inner layers, leading to normal plant architecture82. CSLD5-mediated cell wall synthesis may be transformed into mechanical signaling that fine-tunes cellular activities in the inner tissues, as has been proposed for the brassinosteroid-promoted growth of internal tissue by affecting epidermal wall mechanics83. The effect of ectopic activity of CSLD5 in Arabidopsis SAM, and of OsCSLD4 in inflorescence meristem development in rice, demonstrates a cross-species conserved role of the L1 layer in guiding shoot meristem growth. This provides insights into how plant domestication, primarily driven by developmental changes, may involve crosstalk between cell wall and meristem biology.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) was used as the wild-type control. The mutant lines csld2, csld5, ixr1-2, and myb3r1 myb3r4 have been described previously40,61,84. The csld2 csld5 double mutant was generated through crossing. All the GT mutants were ordered from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Center, and the mutant information is listed in Table S1. Seeds were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol/0.05% Triton X-100 for 5 min and briefly rinsed in 95% ethanol for 1 min. The seeds were dried under a sterile hood and germinated on horizontal or vertical plates containing half-strength solid Murashige-Skoog medium. After 11 days, the seedlings were transferred to soil. The plants were cultivated in a growth chamber under the following conditions: long-day photoperiod (16-h light/8-h dark), light intensity 170 μmoles m−2 s−1, day/night temperature 21/17 °C.

Rice (Oryza sativa) plants were grown in protected paddy fields at the Shanghai or Hainan Island experimental stations. Tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) plants were grown at 22 °C under long-day conditions (16-h day/8-h night), and the leaves of 3–4-week-old plants were used for transient expression experiments.

Plasmid construction and plant transformation

For pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD5, a 2,995 bp of the promoter upstream of the CSLD5 start codon was amplified with primers D5P-F (KpnI) and D5P-R (PstI). A 717 bp GFP coding region was amplified with primers GFP-F (PstI) and GFP-R (SpeI). A 4270 bp genomic fragment containing the whole coding sequence of CSLD5, as well as a 487 bp 3’ region, was amplified with primers D5DNA_F (SpeI) and D5DNA_R (XbaI). The three fragments were sequentially ligated into the vector pBluescript SK-, giving rise to SK-D5pro, SK-D5pro-GFP, and SK-D5pro-GFP-D5. The whole fragment containing the CSLD5 promoter, GFP, and CSLD5 coding region were digested with KpnI and XbaI, which was ligated into pCAMBIA1300.

For pCSLD5::mCherry-CSLD5, a 3,000 bp of the promoter upstream of the CSLD5 start codon was amplified with primers D5pro-F (EcoRI) and D5pro-R (KpnI), and a 1000 bp 3’ region was amplified with primers D5ter1k_F (XbaI) and D5ter1k_R (HindIII). The vector pCAMBIA1300 was digested with EcoRI and HindIII, and the two PCR products were inserted into pCAMBIA1300 by homologous recombination (ClonExpress, Vazyme), resulting in 1300-pCSLD5-MCS-CSLD5ter1k. A 708 bp of mCherry coding region was amplified with primers mCherry-F (KpnI) and mCherry-R (KpnI), and a 3,777 bp genomic fragment containing the whole coding sequence of CSLD5 was amplified with primers D5g_F (KpnI) and D5g_R (BamHI). The 1300-pCSLD5-MCS-CSLD5ter1k was digested with KpnI and BamHI, and the mCherry and CSLD5 fragments were inserted into pCSLD5-MCS-CSLD5ter1k by homologous recombination, resulting in pCSLD5::mCherry-CSLD5.

For pATML1::GFP-CSLD5, the GFP-CSLD5 fusion fragment was amplified with primers GFP-1300-SacI-F and CSLD5-R (PstI) using 1300-pCSLD5::GFP-CSLD5 as a template. The PCR product was inserted into 1300-Nos by homologous recombination, resulting in 1300-GFP-CSLD5-Nos. The promoter of ATML1 was amplified with primers pATML1-F and pATML1-R using genomic DNA as template. The PCR product was inserted into 1300-GFP-CSLD5-Nos by homologous recombination, giving rise to the pATML1::GFP-CSLD5.

For pRPS5A::GFP-CSLD5, the promoter of RPS5A was amplified with primers pRPS5A-F and pRPS5A-R using genomic DNA as template, and the eGFP coding region was amplified with primers eGFP-F and eGFP-R. The PCR products were inserted into 1300-Nos by homologous recombination, resulting in 1300-pRPS5A-eGFP-MCS-Nos. The genomic fragment containing the whole coding sequence of CSLD5 was amplified with primers CSLD5-F (SalI) and CSLD5-R (PstI), which was ligated into 1300-pRPS5A-eGFP-MCS-Nos by homologous recombination, resulting in pRPS5A::GFP-CSLD5.

For pCSLD5::GFP-CESA1, pCSLD5::GFP-CESA3, and pCSLD5::GFP-CESA6, eGFP coding region was amplified with primers eGFP-F/eGFP-R (BamHI). The PCR products were inserted into 1300-pCSLD5-MCS-CSLD5ter1k by homologous recombination, resulting in 1300-pCSLD5-eGFP-MCS-CSLD5ter1k. The genomic fragment containing the whole coding sequence of CESA1, CESA3, or CESA6 were amplified with primers CESA1-F (BamHI)/CESA1-R (PstI), CESA3-F (BamHI)/CESA3-R (PstI), and CESA6-F (BamHI)/CESA6-R (PstI). The PCR products were inserted into 1300-pCSLD5-eGFP-MCS-CSLD5ter1k by homologous recombination.

For pUBQ10::GFP-CESA1, pUBQ10::GFP-CESA3, and pUBQ10::GFP-CESA6, the CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 genomic DNA fragments containing the whole coding regions were amplified with primers CESA1-F (KpnI)/CESA1-R (BamHI), CESA3-F (KpnI)/CESA3-R (BamHI), and CESA6-F (KpnI)/CESA6-R (BamHI). The vector pCAMBIA1300-UBQ10-eGFP(N)-NOS was digested with KpnI and BamHI, and the PCR products were inserted into pCAMBIA1300-UBQ10-eGFP(N)-NOS by homologous recombination.

Confocal microscopy imaging and data analysis

SAM sample preparation

The main inflorescence meristems at the bolting stage were used to analyze the SAM size, gene expression patterns, and protein subcellular dynamics. About one centimeter of the shoot apex was cut from the tip, and the SAMs were dissected under a stereoscopic microscope. After removing the larger flowers, the SAMs were transferred to a box containing fresh MS medium (Murashige & Skoog medium including vitamins). To show the cell boundaries, the SAMs were stained with 0.1% propidium iodide (PI) for 2 min to label the cell walls. The dye solutions were rinsed off with sterile water prior to imaging.

Long-term time-lapse imaging

For tracking cell division at the SAM, the plants were taken out of the soil and transferred to lidded boxes containing room temperature Arabidopsis medium. The larger flowers were removed to expose the inflorescence meristem. The plants were left to recover in a growth chamber with a 16/8-h light/dark cycle for 12 h before confocal imaging. Confocal z-stacks of the SAMs were acquired with either a 25 × NA 0.95 long-distance water-dipping objective on a Leica SP8 or a 40 × NA 1.2 long-distance water-dipping objective on a Zeiss LSM880. Laser excitations were 488 nm (PI, GFP) and 555 nm or 561 nm (RFP, FM4-64). 3D rendering was carried out in Fiji.

Live imaging of rice shoot meristems

At the reproductive-to-reproductive transition stage (around 60 days after germination), the shoot apices of rice plants were dissected. The leaves and leaf sheaths were carefully removed to expose the floral primordia for confocal imaging.

Image processing and analysis

Cell size, cell growth, and cell lineage tracking were all performed using MorphoGraphX according to the user manual (http://www.morphographx.org)16,17. Briefly, for each SAM, a surface mesh was extracted from the confocal stack. The cells were segmented, and the cell size was quantified. To assess cell growth and cell division activity, confocal stacks of the same SAM at different time points were segmented. The daughter cells were assigned with the parent labels. A cell growth heatmap was created based on the change in the size of the same cells at different time points. Cell division was analyzed by using the “Heat Map Proliferation” tool.

AFM measurements

The AFM data were collected as previously described13. The dissected SAMs were immobilized on glass slides with room temperature agarose. The SAMs were immersed in 0.55 M mannitol to remove the turgor pressure. To measure the stiffness of the sample cell walls, an AFM cantilever loaded with a spherical tip was used to indent the sample over a 100 × 100 μm square area, within the area 64 × 64 measurements were made resulting in 4096 force-indentation experiments; each force-indentation experiment was treated with a Hertzian indentation model to extrapolate the apparent Young’s modulus; each pixel in a stiffness map represents the apparent Young’s modulus from one force-indentation point. For topographical reconstructions, the height of each point was determined by the point of contact from the force-indentation curve; each contact point is from the same curve used to determine the apparent Young’s modulus (EA). Stiffness data were projected onto topographical maps using Matlab. The cantilevers used were as follows: “Nano World” (NanoWorld AG, Neuchâtel, Switzerland) TL-NCH-20 tips with a spring constant of 10−130 N/m (estimated to be 1.5 N/m) with Sphere Tips of a 900−1100 nm radius.

A total of 17 WT, 14 csld5, and 7 csld5 pATML1::GFP-CSLD5 SAMs were examined across three experimental series. Due to the length of time for sample preparation and immobilization, proper alignment of the cantilever over the SAM, and acquisition of data, AFM measurements were not acquired together in the same session nor with the same cantilever (cantilevers become spent due to contamination, damage, or issues during mounting on the AFM head). For this reason, calibrated cantilevers were first used from Batch A (calibrated to a master reference calibration cantilever). Batch A calibrated cantilevers were used for 2/7 wild-type (WT, Col-0) and 2/6 csld5 SAMs for Experiment 1, which supplies the data for Fig. 3a, and for 4/4 csld5 SAMs in Experiment 2, which supplies data for Fig. S8c. Once all the Batch A calibrated cantilevers (including the master reference calibration cantilever) were spent, subsequent cantilevers (Batch B) were calibrated based on the rigidity of a custom-made gravity-calibrated cantilever as described in ref. 85. Due to the two different modes of calibration, Batch B cantilever data were normalized to Batch B WT cantilever data using the formula (A × 5,000,000)/(X̄WT − 1202) for Experiment 1, and the formula (A × 5,000,000)/(X̄WT + 1202) for Experiment 2. In these formulae, A represents the measured rigidity of a given sample, and X̄WT denotes the average rigidity of the WT meristems within the respective experiment. The values 5,000,000 and 1202 represent constants to interconvert the two different reference calibration cantilevers. While this normalization does not mitigate the effects of inter-experimental variability, it preserves genotype-specific trends.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Co-IP assays were conducted to verify the protein interactions in planta. A 3774 bp genomic fragment containing the coding sequence of CSLD5 was amplified with primers D5g_F1 (KpnI)/D5g_R1 (BamHI), and cloned into the vector pCAMBIA1300-UBQ10-eGFP(N)-NOS via homologous recombination, resulting in the construct pUBQ10::eGFP(N)-CSLD5-NOS. The CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 genomic fragments were amplified with primer pairs CESA1-flag-F (KpnI)/CESA1-flag-R (PstI), CESA3-flag-F (KpnI)/CESA3-flag-R (PstI), and CESA6-flag-F (KpnI)/CESA6-flag-R (PstI). The vector pCAMBIA1300-UBQ10-3xFlag(N)-NOS was digested with KpnI and PstI, and the PCR products were inserted into pCAMBIA1300-UBQ10-3xFlag(N)-NOS by homologous recombination, giving rise to pUBQ10::3xFlag(N)-CESA1-NOS, pUBQ10::3xFlag(N)-CESA3-NOS, and pUBQ10::3xFlag(N)-CESA6-NOS.

All plasmids were transformed into the Agrobacterium strain GV3101 and expressed in N. benthamiana leaves through co-infiltration. The infiltrated leaves were ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. IP extraction buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail was added to the tissue powder, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. Following centrifugation at 13,400×g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was incubated with Anti-GFP Affinity Beads 4FF (Smart-Lifesciences) at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed three times with IP extraction buffer. SDS loading buffer was added to the beads, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were detected using the cognate antibodies.

CESA and CSLD5 co-localization assay

For transient expression in N. benthamiana, pUBQ10::GFP-CESA1, pUBQ10::GFP-CESA3, and pUBQ10::GFP-CESA6 were co-expressed with pUBQ10::mCherry(N)-CSLD5 in N. benthamiana leaf cells by co-infiltration. Fluorescence signals were detected 48 h after transformation using a laser scanning confocal microscope (ZEISS LSM 880).

For co-localization studies in Arabidopsis seedlings, the constructs pUBQ10::mCherry-CSLD5, pUBQ10::eGFP-CESA1, pUBQ10::eGFP-CESA3, and pUBQ10::eGFP-CESA6 were transformed into Col-0. The double reporter lines co-expressing mCherry-CSLD5 and GFP-CESAs were generated by crossing the respective single reporter lines. GFP and mCherry fluorescence signals were detected with ZEISS LSM 880.

Protein expression and purification

The coding region of MYB3R1 and MYB3R4 DNA binding domains were amplified with primers R1-DBD-F/R and R4-DBD-F/R, respectively. All PCR products were inserted into the pTolo-EX1 vector by homologous recombination, giving rise to pTolo-EX1-MYB3R1-N, and pTolo-EX1-MYB3R4-N. The constructs were transformed into E. coli (Rosetta, DE3) and grown in LB medium at 37 °C to OD600 = 0.5. The expression of the recombinant proteins was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG). Bacteria were cultured for 20 h at 18 °C before protein purification. The recombinant proteins were affinity-purified with Ni-NTA beads (smart), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay

The Y2H assay was used to detect protein interaction following the DUALhunter system (Dualsystems Biotech). The coding sequences of CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 were fused to the Nub fragment encoded in the pXGY17 vector, and the full coding sequence of CSLD5 was fused to the Cub fragment encoded in the pXGY18 vector. The constructs were transformed into the yeast strain NMY51 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The yeast transformants were grown on nutrient-restricted mediums to examine the interactions between various protein combinations.

EMSA

The DNA fragments within the CSLD5 promoter region were labeled with Cy5 and used as probes for the electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). To synthesize the probes, the DNA fragments were amplified using gene-specific primers, and labeled with 5’ Cy5 in a second round of PCR using a universal primer. The DNA binding domains of MYB3R1 (aa 1–200) and MYB3R4 (aa 1–200) were purified and incubated with 7.5 nM Cy5-labeled DNA probes in buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 250 mM KCl, 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT at room temperature for 30 min. For the competition assay, various amounts of unlabeled DNA with identical sequences to the fluorescent probes were mixed with the labeled DNA probes. The protein-DNA mixture was subsequently fractionated on a 4.5% native gel in running buffer containing 0.5 × TBE at 100 V for 1 h in a 4 °C cold room. The gels were scanned with a Typhoon FLA 9000 (FUJIFILM FLA 9000 plus DAGE).

Transactivation assay

The dual-luciferase assay was used to assess the transcriptional activities of MYB3R1 and MYB3R4 on the CSLD5 promoter. A 2995 bp of the CSLD5 promoter was digested from the construct SK-D5pro with KpnI and BamHI and ligated into the pGreenII 0800-LUC vector, resulting in pCSLD5::LUC. In these constructs, REN was expressed under the control of the 35S promoter, which was used as an internal control. The constructs UBQ10::GFP-MYB3R1, UBQ10::GFP-MYB3R4, and pCSLD5::LUC were transiently expressed in tobacco leaf cells through Agrobacterium infiltration. The RNA silencing suppressor P19 was also co-expressed to increase gene expression efficiency. The activities of LUC and REN were assessed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The LUC activity was normalized to the REN activity (LUC/REN). The means and standard errors of LUC/REN were calculated from six independent biological replicates.

ChIP qPCR

For the ChIP assay, around 1000 shoot apices of pMYB3R1::GFP-MYB3R1 and pMYB3R4::GFP-MYB3R4 plants were pooled for chromatin extraction. After grinding in liquid nitrogen, the plant materials were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. ChIPs were performed using an anti-GFP antibody (Ab290, Abcam) in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail coupled to a 1:1 mix of protein-A and protein-G Dynabeads (Life Technologies, 510001D and 10003D). DNA was extracted using AMPure beads. qPCR was performed with primers D5-ChIP-R1-F/R and D5-ChIP-R2-F/R. The sequences of the primers are listed in Table S2.

mRNA in situ hybridization

For mRNA in situ hybridization, the shoot apices were dissected and fixed in FAA (3.7% formaldehyde, 5% acetic acid, and 50% ethanol) at 4 °C overnight. The samples were then embedded in wax and sectioned into 8-µm slices. After dewaxing, rehydration and dehydration, the sections were hybridized with CSLD5 RNA probes at 55 °C overnight. After hybridization, the slides were washed in SSC and incubated with an anti-digoxigenin-AP antibody (Roche) for 2 h at room temperature. The hybridization signals were detected by NBT/BCIP (Roche) color reaction. The CSLD5 RNA probes were prepared by in vitro transcription using the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (Roche). Images were taken in a Zeiss AxioImager M2 microscope with a PlanApochromat 20x/0.8 NA objective and a Zeiss Axiocam MRc color camera.

For fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), the anti-digoxigenin-POD (Roche) antibody was used instead of the anti-digoxigenin-AP antibody, and the hybridization signals were detected using the TSA Plus Cy5 Fluorescence System (Perkin Elmer). Before observation of the hybridization signals, the slides were mounted with 1 mg/ml DAPI to stain the nuclei. The RNA FISH images were taken in a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope with a 20 × 0.8NA dry objective. Laser excitations were 405 nm (DAPI) and 633 nm (Cy5). Fluorescence intensities were quantified in Fiji.

CBM4 staining

CBM4 staining was performed to detect the amorphous cellulose. His-tagged CBM4 of Cellulomonas fimi (ATCC 484) endoglucanase C (CBD4N1) was produced in E. coli. The samples were prepared as described previously86. In brief, deparaffinized, hydrated 4-µm sections of shoot meristems were incubated with CBM4 recombinant protein in 2F4 buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl at pH 7.5, 5% milk) for at least 3 h. The sections were then counterstained with secondary antibodies directed against the His-tag, produced in either chicken or rabbit, in 2F4 buffer with 5% milk for at least 2 h. Finally, the staining was detected using a fluorescent anti-chicken or anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with either CF488 or Alexa 568 fluorophores. CBM4 was a kind gift from Harry Gilbert87,88.

Alexander staining

The viability of pollen grains was evaluated by Alexander staining. Mature anthers were collected before anthesis and immersed in Alexander’s solution, which consisted of 10% (v/v) EtOH, 0.1 mg/ml malachite green, 25% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mg/ml phenol, 50 mg/ml chloral hydrate, 0.5 mg/ml acid fuschin, 50 µg/ml orange G, and 1% (v/v) glacial acetic acid. The pollen grains were stained overnight at room temperature. After staining, the anthers were rinsed and mounted on a microscope slide for observation under bright-field microscopy.

Lignin measurement

The quantification of total lignin was performed using the acetyl bromide soluble lignin (ASBL) assay. Leaves from one-month-old plants were collected and dried at 65 °C. The samples were then ground to a fine powder and used for alcohol insoluble residues (AIR) preparation following the method described by ref. 89. Briefly, the powder was washed sequentially with 70% (v/v) ethanol, chloroform/methanol (1:1 v/v), and acetone. The AIR was subsequently treated with α-amylase (1 μg/mL) and pullulanase (10 units/mL) in a 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). Finally, the samples were washed with water and acetone, then dried at 45 °C. The lignin content was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm using a spectrophotometer as described previously90.

RNA sequencing analysis

For transcriptome analysis, the shoot apices of Col-0, csld5, and csld5;pATML1::GFP-CSLD5 plants were pooled for RNA extraction and library preparation. RNA sequencing was performed using the Illumina platform. Raw sequencing reads were trimmed with Trimmomatic v.0.39 to remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences. The quality of the sequencing data was evaluated using FastQC v0.12.1. Reads were then aligned to the TAIR10 transcriptome using Hisat2 v2.2.1. Gene expression levels were quantified using TPMCalculator v0.0.3 and featureCounts v2.0.6. Heatmaps were generated in R to visualize the expression levels. The ClusterProfiler package in R was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis. Coding sequences (CDS) were retrieved from TAIR and searched against the non-redundant protein sequences (nr) database using DIAMOND BLASTX. The top 20 blast hits with an E-value cutoff of 10−3 for each sequence were loaded into Blast2GO Basic for GO mapping and annotation. The default annotation configuration was fixed with a GO weight of 5 and an annotation cutoff of 75. KEGG Orthology (KO) annotation was performed by sequence BLAST against KEGG GENES through KofamKOALA.

Statistics

Quantification analysis on SAM size, cell size, and plant weight was conducted in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All values are presented with mean ± SD. Significance of difference was examined by Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA test. Individual data points are displayed as box and whisker plots with the error bars representing maximum and minimum values (center line, median; box limits, 25th and 75th percentiles). Detailed descriptions of quantifications and statistical analyses can be found in the figures, figure legends, or methods section.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Sequencing data are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE272708. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Meyerowitz, E. M. Genetic control of cell division patterns in developing plants. Cell 88, 299–308 (1997).

Greb, T. & Lohmann, J. U. Plant stem cells. Curr. Biol. 26, R816–R821 (2016).

Pfeiffer, A., Wenzl, C. & Lohmann, J. U. Beyond flexibility: controlling stem cells in an ever changing environment. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 35, 117–123 (2017).

Reinhardt, D. et al. Regulation of phyllotaxis by polar auxin transport. Nature 426, 255–260 (2003).

Heisler, M. G. et al. Patterns of auxin transport and gene expression during primordium development revealed by live imaging of the Arabidopsis inflorescence meristem. Curr. Biol. 15, 1899–1911 (2005).

Smith, R. S. et al. A plausible model of phyllotaxis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 1301–1306 (2006).

Jönsson, H., Heisler, M. G., Shapiro, B. E., Meyerowitz, E. M. & Mjolsness, E. An auxin-driven polarized transport model for phyllotaxis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 1633–1638 (2006).

Besnard, F. et al. Cytokinin signalling inhibitory fields provide robustness to phyllotaxis. Nature 505, 417–421 (2014).

Zhao, Z. et al. Hormonal control of the shoot stem-cell niche. Nature 465, 1089–1092 (2010).

Sampathkumar, A. et al. Primary wall cellulose synthase regulates shoot apical meristem mechanics and growth. Development 146, dev179036 (2019).

Trinh, D. C. et al. How mechanical forces shape plant organs. Curr. Biol. 31, R143–R159 (2021).

Hamant, O. et al. Developmental patterning by mechanical signals in Arabidopsis. Science 322, 1650–1655 (2008).

Peaucelle, A. et al. Pectin-induced changes in cell wall mechanics underlie organ initiation in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 21, 1720–1726 (2011).

Heisler, M. G. et al. Alignment between PIN1 polarity and microtubule orientation in the shoot apical meristem reveals a tight coupling between morphogenesis and auxin transport. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000516 (2010).

Louveaux, M., Julien, J. D., Mirabet, V., Boudaoud, A. & Hamant, O. Cell division plane orientation based on tensile stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E4294–E4303 (2016).

Landrein, B. et al. Mechanical stress contributes to the expression of the STM homeobox gene in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. eLife 4, e07811 (2015).

Hamant, O. & Traas, J. The mechanics behind plant development. N. Phytol. 185, 369–385 (2010).

Wolf, S., Hematy, K. & Hofte, H. Growth control and cell wall signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 381–407 (2012).

Bidhendi, A. J. & Geitmann, A. Relating the mechanics of the primary plant cell wall to morphogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 449–461 (2016).

Coen, E. & Cosgrove, D. J. The mechanics of plant morphogenesis. Science 379, eade8055 (2023).

Somerville, C. et al. Toward a systems approach to understanding plant cell walls. Science 306, 2206–2211 (2004).

Cosgrove, D. J. Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 850–861 (2005).

Facette, M. R., Rasmussen, C. G. & Van Norman, J. M. A plane choice: coordinating timing and orientation of cell division during plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 47, 47–55 (2019).

Gu, Y. & Rasmussen, C. G. Cell biology of primary cell wall synthesis in plants. Plant Cell 34, 103–128 (2022).

Taylor, N. G., Laurie, S. & Turner, S. R. Multiple cellulose synthase catalytic subunits are required for cellulose synthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12, 2529–2540 (2000).

Persson, S. et al. Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15566–15571 (2007).

Desprez, T. et al. Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 15572–15577 (2007).

Paredez, A. R., Somerville, C. R. & Ehrhardt, D. W. Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science 312, 1491–1495 (2006).

Richmond, T. A. & Somerville, C. R. The cellulose synthase superfamily. Plant Physiol. 124, 495–498 (2000).

Verhertbruggen, Y., Yin, L., Oikawa, A. & Scheller, H. V. Mannan synthase activity in the CSLD family. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1620–1623 (2011).

Yin, L. et al. The cooperative activities of CSLD2, CSLD3, and CSLD5 are required for normal Arabidopsis development. Mol. Plant 4, 1024–1037 (2011).

Yang, J. et al. Biochemical and genetic analysis identify CSLD3 as a ß−1,4-glucan synthase that functions during plant cell wall synthesis. Plant Cell 32, 1749–1767 (2020).

Doblin, M. S., De Melis, L., Newbigin, E., Bacic, A. & Read, S. M. Pollen tubes of Nicotiana alata express two genes from different ß-glucan synthase families. Plant Physiol. 125, 2040–2052 (2001).

Wang, X. et al. AtCSLD3, a cellulose synthase-like gene important for root hair growth in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 126, 575–586 (2001).

Favery, B. et al. KOJAK encodes a cellulose synthase-like protein required for root hair cell morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 15, 79–89 (2001).

Bernal, A. J. et al. Disruption of AtCSLD5 results in reduced growth, reduced xylan and homogalacturonan synthase activity and altered xylan occurrence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 52, 791–802 (2007).

Bernal, A. J. et al. Functional analysis of the cellulose synthase-like genes CSLD1, CSLD2, and CSLD4 in tip-growing Arabidopsis cells. Plant Physiol. 148, 1238–1253 (2008).

Galway, M. E., Eng, R. C., Schiefelbein, J. W. & Wasteneys, G. O. Root hair-specific disruption of cellulose and xyloglucan in AtCSLD3 mutants, and factors affecting the post-rupture resumption of mutant root hair growth. Planta 233, 985–999 (2011).

Park, S., Szumlanski, A. L., Gu, F., Guo, F. & Nielsen, E. A role for CSLD3 during cell-wall synthesis in apical plasma membranes of tip-growing root-hair cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 973–980 (2011).

Yang, W. et al. Regulation of meristem morphogenesis by cell wall synthases in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 26, 1404–1415 (2016).

Kim, S. J. et al. The synthesis of xyloglucan, an abundant plant cell wall polysaccharide, requires CSLC function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 20316–20324 (2020).

Brown, D. M., Zhang, Z., Stephens, E., Dupree, P. & Turner, S. R. Characterization of IRX10 and IRX10-like reveals an essential role in glucuronoxylan biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 57, 732–746 (2009).

Zabotina, O. A. et al. Mutations in multiple XXT genes of Arabidopsis reveal the complexity of xyloglucan biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 159, 1367–1384 (2012).

Caffall, K. H., Pattathil, S., Phillips, S. E., Hahn, M. G. & Mohnen, D. Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutants implicate GAUT genes in the biosynthesis of pectin and xylan in cell walls and seed testa. Mol. Plant 2, 1000–1014 (2009).

Liwanag, A. J. et al. Pectin biosynthesis: GALS1 in Arabidopsis thaliana is a β−1,4-galactan β−1,4-galactosyltransferase. Plant Cell 24, 5024–5036 (2012).

Zhao, F. et al. Xyloglucans and microtubules synergistically maintain meristem geometry and phyllotaxis. Plant Physiol. 181, 1191–1206 (2019).

Barbier de Reuille, P. et al. MorphoGraphX: a platform for quantifying morphogenesis in 4D. Elife 4, 05864 (2015).

Strauss, S. et al. Using positional information to provide context for biological image analysis with MorphoGraphX 2.0. Elife 11, e72601 (2022).

Gu, F. et al. Arabidopsis CSLD5 functions in cell plate formation in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Plant Cell 28, 1722–1737 (2016).

Hunter, C. T. et al. Cellulose Synthase-Like D1 is integral to normal cell division, expansion, and leaf development in maize. Plant Physiol. 158, 708–724 (2012).

Milani, P. et al. In vivo analysis of local wall stiffness at the shoot apical meristem in Arabidopsis using atomic force microscopy. Plant J. 67, 1116–1123 (2011).

Kierzkowski, D. et al. Elastic domains regulate growth and organogenesis in the plant shoot apical meristem. Science 335, 1096–1099 (2012).

Geitmann, A. & Ortega, J. K. Mechanics and modeling of plant cell growth. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 467–478 (2009).

Boerjan, W. et al. Top five unanswered questions in plant cell surface research. Cell Surf. 11, 100121 (2024).

Hong, L. et al. Variable cell growth yields reproducible organ development through spatiotemporal averaging. Dev. Cell 38, 15–32 (2016).

Sapala, A. & Smith, R. S. Osmotic treatment for quantifying cell wall elasticity in the sepal of Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Mol. Biol. 2094, 101–112 (2020).

Boudaoud, A. An introduction to the mechanics of morphogenesis for plant biologists. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 353–360 (2010).

Hamant, O. & Haswell, E. S. Life behind the wall: sensing mechanical cues in plants. BMC Biol. 15, 59 (2017).

Van Moerkercke, A. et al. A MYC2/MYC3/MYC4-dependent transcription factor network regulates water spray-responsive gene expression and jasmonate levels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 23345–23356 (2019).

Lee, D., Polisensky, D. H. & Braam, J. Genome-wide identification of touch- and darkness-regulated Arabidopsis genes: a focus on calmodulin-like and XTH genes. N. Phytol. 165, 429–444 (2005).

Yang, W. et al. Molecular mechanism of cytokinin-activated cell division in Arabidopsis. Science 371, 1350–1355 (2021).

Crowell, E. F. et al. Pausing of Golgi bodies on microtubules regulates secretion of cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 1141–1154 (2009).

Li, M. et al. Rice cellulose synthase-like D4 is essential for normal cell-wall biosynthesis and plant growth. Plant J. 60, 1055–1069 (2009).

Miart, F. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of cellulose synthesis during cell plate formation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 77, 71–84 (2014).

Sablowski, R. & Gutierrez, C. Cycling in a crowd: Coordination of plant cell division, growth, and cell fate. Plant Cell 34, 193–208 (2022).

Kumar, M., Carr, P. & Turner, S. R. An atlas of Arabidopsis protein S-acylation reveals its widespread role in plant cell organization and function. Nat. Plants 8, 670–681 (2022).

Roberts, E. M. et al. An alternate route for cellulose microfibril biosynthesis in plants. Sci. Adv. 10, eadr5188 (2024).

Kljun, A. et al. Comparative analysis of crystallinity changes in cellulose I polymers using ATR-FTIR, X-ray diffraction, and carbohydrate-binding module probes. Biomacromolecules 12, 4121–4126 (2011).

Zhu, J. et al. A cellulose synthase-like protein is required for osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 63, 128–140 (2010).

Manfield, I. W. et al. Novel cell wall architecture of isoxaben-habituated Arabidopsis suspension-cultured cells: global transcript profiling and cellular analysis. Plant J. 40, 260–275 (2004).

Weijers, D. et al. An Arabidopsis Minute-like phenotype caused by a semi-dominant mutation in a RIBOSOMAL PROTEIN S5 gene. Development 128, 4289–4299 (2001).

Takada, S. & Jurgens, G. Transcriptional regulation of epidermal cell fate in the Arabidopsis embryo. Development 134, 1141–1150 (2007).

Meyer, H. M. et al. Fluctuations of the transcription factor ATML1 generate the pattern of giant cells in the Arabidopsis sepal. Elife 6, e19131 (2017).

Kierzkowski, D., Lenhard, M., Smith, R. & Kuhlemeier, C. Interaction between meristem tissue layers controls phyllotaxis. Dev. Cell 26, 616–628 (2013).

Goswami, R. et al. Mechanical shielding in plant nuclei. Curr. Biol. 30, 2013–2025 (2020).

Yoshikawa, T., Eiguchi, M., Hibara, K., Ito, J. & Nagato, Y. Rice slender leaf 1 gene encodes cellulose synthase-like D4 and is specifically expressed in M-phase cells to regulate cell proliferation. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 2049–2061 (2013).

Ito, M. et al. Position dependent expression of GL2-type homeobox gene, Roc1: significance for protoderm differentiation and radial pattern formation in early rice embryogenesis. Plant J. 29, 497–507 (2002).

Zhang, Y. et al. Molecular insights into the complex mechanics of plant epidermal cell walls. Science 372, 706–711 (2021).

Reinhardt, D., Frenz, M., Mandel, T. & Kuhlemeier, C. Microsurgical and laser ablation analysis of interactions between the zones and layers of the tomato shoot apical meristem. Development 130, 4073–4083 (2003).

Johnson, K. L., Degnan, K. A., Ross Walker, J. & Ingram, G. C. AtDEK1 is essential for specification of embryonic epidermal cell fate. Plant J. 44, 114–127 (2005).

Bemis, S. M. & Torii, K. U. Autonomy of cell proliferation and developmental programs during Arabidopsis aboveground organ morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 304, 367–381 (2007).

Savaldi-Goldstein, S., Peto, C. & Chory, J. The epidermis both drives and restricts plant shoot growth. Nature 446, 199–202 (2007).

Kelly-Bellow, R. et al. Brassinosteroid coordinates cell layer interactions in plants via cell wall and tissue mechanics. Science 380, 1275–1281 (2023).

Scheible, W. R., Eshed, R., Richmond, T., Delmer, D. & Somerville, C. Modifications of cellulose synthase confer resistance to isoxaben and thiazolidinone herbicides in Arabidopsis Ixr1 mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10079–10084 (2001).

Mitrossilis, D. et al. Real-time single-cell response to stiffness. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16518–16523 (2010).

Haas, K. T., Wightman, R., Meyerowitz, E. M. & Peaucelle, A. Pectin homogalacturonan nanofilament expansion drives morphogenesis in plant epidermal cells. Science 367, 1003–1007 (2020).

Johnson, P. E., Tomme, P., Joshi, M. D. & McIntosh, L. P. Interaction of soluble cellooligosaccharides with the N-terminal cellulose-binding domain of Cellulomonas fimi CenC 2. NMR and ultraviolet absorption spectroscopy. Biochemistry 35, 13895–13906 (1996).

Blake, A. W. et al. Understanding the biological rationale for the diversity of cellulose-directed carbohydrate-binding modules in prokaryotic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29321–29329 (2006).

Foster, C. E., Martin, T. M. & Pauly, M. Comprehensive compositional analysis of plant cell walls (Lignocellulosic biomass) part I: lignin. J. Vis. Exp. 37, 1745 (2010).

Barnes, W. J. & Anderson, C. T. Acetyl bromide soluble lignin (ABSL) assay for total lignin quantification from plant biomass. Bio. Protoc. 7, e2149 (2017).

Acknowledgements