Abstract

Both commercial and laboratory-synthesized IrO2 catalysts typically possess rutile-type structures with multiple facets. Theoretical results predict the (101) facet is the most energetically favorable for oxygen evolution reaction owing to its lowest energy barrier. Achieving monolayer thickness while exposing this desired facet is a significant opportunity for IrO2. Herein, we develop an ammonia-induced facet engineering for the synthesis of single-faceted IrO2(101) monolayer. It achieves 230 mV overpotential at 10 mA cmgeo-2 in a three-electrode system and 1.70 V at 2 A cmgeo-2 in a proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer. Though facet engineering primarily contributes to modulating the intrinsic activity rather than stability, single-faceted IrO2 monolayer performs over 10,000-hour stability at constant 1.5 A cmgeo-2 (3.95 mV kh-1 decay) and 1000-hour stability at 0.2 mgIr cmgeo-2 under fluctuating conditions. This work proposes that ammonia-induced facet engineering of IrO2 monolayer enables facet-dependent oxygen evolution reaction (OER) performance and high stability in industrial-scale PEM electrolysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hydrogen (H2), benefiting from its low-carbon intensity, high energy capacity and easy recyclability, is widely applied as an ideal energy carrier to ease the burden of energy and climate issues. Large-scale production of green hydrogen is highly dependent on the conversion of surplus electricity from renewable but fluctuating sources like solar, wind, and hydro power1. Coupling proton exchange membrane water electrolysis (PEMWE) technology with fluctuating renewables presents a promising avenue for producing green hydrogen, which is highly desired to achieve the international goal of “carbon neutrality”. The rate of the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) kinetics at the anode is significantly determined by electrocatalysts, posing a primary challenge to PEMWE commercialization2,3. An even more critical impediment lies in the limited stability of electrocatalysts under both steady-state and fluctuating operational conditions, especially in a strongly acidic environment. To fulfill the industrial demands of PEMWE systems, there is an urgent need to develop high stable and active electrocatalysts, particularly anodic OER catalysts that can operate robustly at industrial-level constant current density or even highly fluctuating current densities, as generated by fluctuating renewables such as solar, wind, and hydro power4.

To date, operating current density of 3 A cmgeo-2 under a low electrolytic voltage of 1.80 V is a basic but harsh guideline on OER electrocatalysts for the US Department of Energy (DOE) 2026 technical target5. However, a series of studies reveal an inevitable trend that most IrO2-based nanostructured catalysts hardly maintain OER efficiency beyond 120 h even at a low current density of 10 mA cmgeo-2 in a three-electrode system6. According to the DOE 2022 durability targets for both PEM electrolyzer stacks and systems, the commercial use of electrocatalyst must allow for long-term operation exceeding 40,000 h with a decay rate of less than 4.8 mV kh-1. The huge research gap between DOE durability targets and the current status of anode electrocatalysts evaluated in the laboratory becomes the most imposing barrier preventing large-scale PEMWE commercialization5. Thus, developing IrO2 system to balance OER activity and stability remains a significant challenge towards electrocatalyst design and application, thus leaving a large room for further study.

Until now, IrO2 has been widely deemed as the best anodic catalyst considering the balance between OER activity and stability7. Doping engineering8,9,10,11, support engineering12,13, crystal phase engineering14,15 and morphology engineering16,17 have been adopted as effective strategies to maximize intrinsic Ir activity and minimize Ir loading amount18. For this reason, a series of IrO2-based materials, including nanoparticles19,20, nanoneedles21,22, nanotubes23, nanosheets14,24,25, nanoribbons26, and even single atom27,28,29, have been designed, synthesized, and applied for acidic OER. Although various morphology engineering strategies have been implemented to develop highly active IrO2 electrocatalysts, both laboratory-synthesized and commercial IrO2 mainly exist in a conventional rutile phase with (110), (101), (200) and (211) crystal facets. Selecting an optimal crystal facet as the growth orientation to construct IrO2 may offer an alternative pathway for the direct synthesis of high-performance anode electrocatalyst. Through 2D edge epitaxial growth, it is possible for us to achieve the unique crystal orientation in the monolayer limit without the support of a substrate. Accordingly, 2D monolayer IrO2 with a unique (101) facet (denoted as IrO2(101) monolayer) hold great promise in OER catalysis due to several structural advantages. First, the 2D monolayer nanostructure makes each Ir atom easily accessible to H2O molecules during OER. Second, the completely uniform and periodic structure makes all surface atomic sites are equally active and equally accessible, which is close to homogeneous catalyst. Third, the desired (101) facet can be well exposed via altering the ammonia-induced epitaxial growth at a monolayer thickness. As anticipated, the single-faceted rutile structure may simultaneously maximize the intrinsic activity and stability of IrO2 in both three-electrode cells and PEM device. However, most IrO2 electrocatalysts are synthesized from the high-temperature oxidation of Ir salts using a traditional Adams combustion method, making facet engineering at a monolayer thickness more challenging30.

Here, by developing an ammonia-induced facet engineering, we synthesize 2D single-faceted IrO2(101) monolayer and provide an insight into the long-term PEMWE applications under various operating conditions. Taking advantages of 2D monolayer structure and highly activated (101) facet, IrO2 electrocatalyst exhibits a lowest overpotential of 237 mV at 10 mA cmgeo-2 for OER than that of commercial IrO2 (Comm IrO2). More importantly, the PEM electrolyzer employing IrO2(101) monolayer as anode catalyst enables over 10,000 h stability test at 1.5 A cmgeo-2. Even at a low Ir loading of 0.2 mgIr cmgeo-2, IrO2(101) monolayer anode achieves a low overpotential of only 552 mV and maintains stability for over 2000 h at industrially-relevant 2 A cmgeo-2. The high OER stability derived from the single (101) facet is also confirmed in the next 1000 h fluctuating test for PEMWE.

Results

DFT-guided facet selection

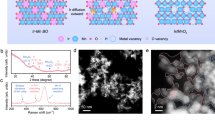

Conventional IrO2 electrocatalysts obtained through the high-temperature Adams fusion method commonly exist as irregular rutile-type nanoparticles with multiple exposed facets31. The rutile phase of IrO2 typically exhibits three primary crystallographic facets: (110), (200), and (101) (Fig. 1a). Different catalytic facets will lead to different catalytic pathways, ultimately exhibiting different catalytic performances32. As a result, the observed OER catalytic activity of IrO2 often represents an average of these various facet-dependent activities. Achieving optimal OER activity through facet engineering of IrO2 along a preferential orientation remains a significant challenge.

a Crystal structure illustration of the (110), (200), and (101) facets of the rutile-phase IrO2. The Gibbs free energy profiles of OER process on different facets at the applied potentials of 1.23 V via the b AEM and c LOM pathways, respectively. The AEM reaction pathways over the d (110), e (200) and f (101) facets, respectively. The Ir, O, and H atoms are represented with the blue, red, and pink circles, respectively.

To gain deeper insights into facet-dependent catalytic performance and subsequently guide the synthesis towards desired facet orientation, we conducted comprehensive density functional theory (DFT) calculations using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). We constructed adsorption models for the (101), (110), and (200) facets of rutile IrO2, and calculated the Gibbs free energies (ΔG) of oxygen intermediates (*OH, *O, and *OOH) to quantitatively assess their adsorption strengths based on both the adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) and the lattice oxygen mechanism (LOM)33,34(Supplementary Figs. 1–3 and Supplementary Tables 1, 2). Our calculations reveal that, for the AEM, the (101) facet exhibits the lowest energy barrier of 0.53 eV (at U = 1.23 V), surpassing the (200) and (110) facets with barriers of 0.64 eV and 0.72 eV, respectively (Fig. 1b). A similar trend is observed in Fig. 1c for the LOM, with the (101) facet again exhibiting the lowest energy barrier. Notably, for the (101) facet, the energy barriers for both AEM and LOM are identical, suggesting that during the OER process on this facet, both reaction mechanisms could potentially occur simultaneously or interchangeably. To elucidate the rate-determining step (RDS) across different facets, we present the reaction pathways in Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. 4a–c. For the (110) and (200) facets, the RDS in both AEM and LOM is the desorption of O2 species (Step 4 in AEM and Step 3 in LOM), indicating strong interactions with O intermediates. In contrast, for the (101) facet, the RDS is identified as the oxidation of *OH to *O (Step 2 in both AEM and LOM), while the desorption steps exhibit significantly lower energy barriers compared to the other facets.

The other mechanisms, including dual-site mechanism (double oxygen coupling mechanism, DOCM) and proton transfer mechanism (PT), were further calculated to comprehensively present the theoretical advantages of the (101) facet. For consistency with the AEM and LOM mechanisms, both DOCM and PT were analyzed as four-step reactions, as illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 5, 6. The corresponding Gibbs free energy profiles for reaction intermediates are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7a, b and Supplementary Tables 3-4. For the DOCM pathway, the RDS is predicted to be the O-O coupling step between adjacent *O and *OH species (Step 4), with energy barriers of 1.50 eV, 2.04 eV, and 2.45 eV for the (101), (200), and (110) facets, respectively. The PT mechanism also indicates distinct facet-dependent characteristics in its RDS. For (200) and (110) facets, the desorption of *OO to form O2 (Step 4) is identified as the RDS, while for the (101) facet, the conversion from *OH to *O (Step 2) becomes RDS. Thus, the energy barriers are 0.53 eV for (101), 0.86 eV for (200), and 1.39 eV for (110) facets, respectively. In conclusion, above four mechanisms display the same facet-dependent trend where (101) < (200) < (110), indicating the superior catalytic activity of the (101) facet.

Analysis of the d-orbital projected density of states (PDOS) of the exposed Ir atoms in the three models reveals that the Ir atoms in the (101) facet exhibit the lowest d-band center at −2.46 eV, followed by the (200) facet at −2.3 eV, while the (110) facet displays the highest d-band center at −2.13 eV (Supplementary Fig. 8). Previous studies have demonstrated that rutile IrO2 typically exhibits strong binding to O-based intermediates, which impedes the dissociation and desorption of these species, limiting OER activity26,35,36. The downshift of the d-band center can effectively weaken the interaction between the catalytic site and intermediates by increasing the probability of anti-bonding orbital occupation, which is primarily responsible for the optimized OER activity observed on the (101) facet.

Based on these findings, constructing IrO2 catalysts with a preferential (101) facet orientation holds the potential to significantly enhance performance and provide mechanistic insights. Nevertheless, facet-controlled synthesis of 2D IrO2 materials with the desired orientation remains a challenge, particularly at high calcination temperatures during the traditional molten salt method. Guided by DFT prediction, we propose an ammonia-induced crystal phase engineering approach for the synthesis of the rutile IrO2 monolayer featuring a single (101) facet.

The synthesis of 2D IrO2(101) monolayer

Although many facet engineering strategies have been proposed for tailoring the crystal facets under mild conditions, such as the additive-assisted solvothermal method and template approach, there are few studies on the facet engineering of rutile IrO237. As a result of the traditional Adams fusion method, rutile IrO2 tends to grow along various orientations at high oxidation temperatures (400-800 °C) and eventually expose different crystal facets. When high oxidation temperature is essential, selecting the optimal crystal facet while maintaining the monolayer thickness of IrO2 becomes an enormous but meaningful challenge.

Amino-containing compounds are widely applied as a surfactant to favor anisotropic growth of 1D, 2D, and 3D nanostructures in low-temperature solvothermal processes38,39. However, utilizing amino-containing compounds for the synthesis of 2D monolayer structures under high-temperature calcination is still less reported, especially in the case of IrO₂. Based on the previously reported ammonia-induced solvothermal methods, we attempt to apply ammonia solution as an inducer to the high-temperature annealing process, and develop an ammonia-induced facet engineering for oriented regulation of the IrO2 facets at the ultimate monolayer thickness limit.

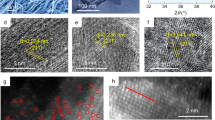

To elucidate the facet-dependent adsorption behavior of NH₃ molecules on rutile-phase IrO₂, DFT calculations were systematically performed (Fig. 2a-c). As illustrated in Fig. 2d, the adsorption energies of NH₃ on IrO₂ (101), (110), and (200) facets were calculated to be −0.64 eV, −0.53 eV, and −0.564 eV, respectively. These computational results clearly indicate that the (101) facet exhibits the strongest NH₃ adsorption affinity among the investigated facets. The pronounced adsorption preference for the (101) facet effectively suppresses its growth kinetics through site-selective molecular passivation, thereby creating a thermodynamic driving force for preferential (101) facet exposure. This DFT simulation provides critical theoretical validation for developing the single-facet engineering of rutile-phase IrO2 along (101) orientation.

The key point of this facet-controlled synthesis has been investigated via modulating the synthesis parameters, elucidating that the nucleation and growth of IrO2(101) monolayer are dominantly guided by NH3·H2O and temperature. During the annealing process, NH3·H2O is introduced as a potent crystal facet growth inducer for exposing desired (101) facet. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 9, IrO2 exhibits a classic rutile structure with strong (110), (101), (200) and (211) diffraction peaks in the absence of NH3·H2O. Upon the addition of 3.2 g NH3·H2O, the (110), (200) and (211) signals are significantly suppressed, while the (101) facet emerges as the dominant crystal surface, revealing the role of NH3·H2O in facilitating the unidirectionally oriented growth of IrO2 grains. Particularly, as the NH3·H2O amount is further increased to 12.8 g, the characteristic peaks corresponding to the (110), (200) and (211) facets almost disappear. Therefore, IrO2(101) monolayer has been successfully constructed through ammonia-induced growth, in which IrO2 nucleation preferentially occurs along the (101) facet, thereby further demonstrating the effect of NH3·H2O. Analogously, the morphological evolution of IrO2 from irregular nanoparticles to 2D monolayers is accompanied by the concurrent crystal evolution. The successful synthesis of single-(101)-faceted monolayer validates the intimate correlation between the morphological and crystallographic changes, where the preferential growth along the (101) facet guides the formation of the 2D monolayer structure (Supplementary Fig. 10).

In addition to NH3·H2O, the unidirectionally oriented growth is also highly dependent on the annealing temperature, making it challenging to expose the unique (101) facet at temperatures exceeding 500 °C. To understand the role of temperature in crystal evolution, XRD characterization was then conducted at different temperatures to simulate the IrO2 growth (Supplementary Fig. 11). The heat temperatures of 350 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C are crucial to its crystal growth (labeled as IrO2(101)−350, IrO2(101) monolayer and IrO2(101)−500, respectively). According to the XRD curves of IrO2, the (101) facet becomes the dominating one at 350 °C and 450 °C. As the temperature increases to 500 °C, the growth velocities of (110), (200) and (211) facets accelerate significantly. Consequently, a conventional rutile IrO2 structure with various crystalline facets will evolve preferentially. As evidenced by TEM images in Supplementary Fig. 12, 2D IrO2 obtained at 350 °C, 450 °C, and 500 °C exhibit the average sizes of 100 nm, 500 nm and 2 μm, respectively, which correspond to the bottom-up growth.

According to a series of previously studies, amino group have also been widely used to bond with the unsaturated dangling bonds and lower the surface energy of the specific facet, resulting in preferential exposure of specific facets at the early nucleation19,40,41. As the importance of amino ligand in facet engineering has been demonstrated, we infer that NH3 molecules that are released from the iridium complex at the high-temperature calcination process can exhibit the strongest adsorption with the IrO2(101) tfacet han other facets. From the thermodynamic perspective, the selective adsorption may lower the surface energy to stabilize (101) facet and facilitate its preferred exposure42,43. From the kinetic perspective, the strongest adsorption ability of NH3 molecules may prevent growth along the [101] direction, while the lateral growth of IrO2 nucleus will competitively occur, which is responsible for directing the formation of the 2D monolayer structure44,45. Based on previous studies and our experiments, we infer that both the kinetics and thermodynamics show a synergistic effect on the final exposed (101) facet of the crystals46,47.

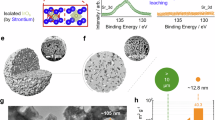

Characterization of 2D IrO2(101) monolayer

In this work, we have successfully synthesized 2D rutile IrO2 in the monolayer limit, uniquely oriented along the (101) facet. As shown in Fig. 3a, as-prepared IrO2 is a freestanding 2D material that can be successfully obtained via an ammoniating process with K2IrCl6, KNO3, and NH3·H2O. TEM images reveal the uniform planar structure and graphene-like morphology with an average size of 200 nm (Supplementary Fig. 13). The ultrathin character greatly improves their mechanical flexibility, and further causes surface corrugations and crumples to form on 2D IrO2 (Fig. 3b). The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image shown in Fig. 3c further displays the 2D structure of rutile IrO2 with dominant (101) facet. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern marked by a red solid box shows a single bright polycrystalline ring (inset in Fig. 3c). Using the graphical circle tool to analyze FFT pattern, the calculated d-spacing is 2.590 Å, which is almost same as the theoretical value of the (101) lattice spacing (2.5863 Å)48. The corresponding intensity profile along the blue rectangle in high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image further exhibits an average space distance of ∼ 2.59 Å, which is almost same as the lattice parameter of 2.5863 Å on the rutile-IrO2 (101) facet (Fig. 3d)19,49. All the crystalline characteristics of 2D IrO2 monolayer confirm a preferential crystal orientation growth along the (101) facet. EDS mapping and line-scanning spectra further display Ir, O and N atoms are well-dispersed over the monolayer structure (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 14). The percentages of Ir, O, and N atoms in the marked region were measured to be 28.52%, 59.33%, and 12.15%, respectively, with an atomic ratio of Ir and O close to the theoretical value of 1:2 (Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Table 5). Trace N atoms during ammonia-induced synthesis may modulate the electronic configuration, potentially altering charge transfer kinetics and intermediate adsorption energy during oxygen evolution. According to atomic force microscopy, 2D IrO2(101) crystals are approximately 2 ~ 3 nm in height, which is close to the theoretical thickness of one- or two-unit cell. And IrO2 typically exhibits a 2D monolayer structure with uniform and smooth surface as measured by 3D structure simulation (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 16).

a TEM image of IrO2(101) monolayer. b HRTEM image of surface corrugation on IrO2. c HRTEM image of the (101) facet. The inset shows the FFT pattern of the marked region. d HRTEM image and the corresponding intensity profile along the blue rectangle in d. e STEM elemental mapping of IrO2(101) monolayer. f AFM image of 2D monolayer IrO2. The scale bars in a, b, c, e and f are 100 nm, 10 nm, 5 nm, 50 nm and 100 nm, respectively.

In general, commercially available IrO2 exists in the rutile phase with (110), (101), (200) and (211) characteristic peaks in XRD pattern (Fig. 4a)50. Different crystal facets will bring about different OER pathways, and finally display different OER performances51. Obtaining a unique crystal orientation of IrO2 via the Adams fusion method remains challenging, owing to the isotropic growth that occurs under high-temperature treatment. Interestingly, with the introduction of amine, only a single (101) diffraction peak is observed on the 2D IrO2(101) monolayer. Rietveld refinement of IrO2(101) monolayer shows the (101) peak accounts for 96.63% of total integrated intensity, indicating the successful construction of a single-faceted structure through ammonia-induced preferred orientation growth (Supplementary Fig. 17). From a macroscopic perspective, the catalyst powder of IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits a distinctly different green color, which contrasts with the grayish powder of Comm IrO2 purchased from Alfa Aesar and Umicore Co., Ltd (Supplementary Fig. 18).

a XRD curves and b XPS spectra of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar), respectively. c Ir 4 f XPS spectra and d O 1 s XPS spectra of IrO2(101) monolayer and Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar). e Raman spectra of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar). f Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar).

As shown in Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 19, the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were conducted to compare the electronic structures of as-prepared IrO2 and Comm IrO2. Except Ir 4 f and O 1 s signals, a negligible N 1 s peak is also detected in XPS spectrum of IrO2(101) monolayer, revealing trace N dopant during the ammonia-induced growth process. The Ir 4 f spectra can be deconvoluted into nine peaks, including two IrIV, two IrIII and five accompanying satellite peaks (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 19a)52,53. The Ir 4 f binding energies of IrO2(101) monolayer and IrO2 NP are almost the same as that of Comm IrO2. Interestingly, the Ir 4f5/2 binding energy of IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits obvious positive shift towards higher binding energy than that of IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2 (Supplementary Table 6), suggesting a stronger electron-donating effect of 2D monolayer structure than that of nanoparticle structures. Based on the proportion of IrIV and IrIII for IrO2(101) monolayer, the Ir species consist of 74.3% IrIV and 25.7% IrIII, indicating the predominant presence of rutile-phase IrO2 (Supplementary Fig. 19b). According to Fig. 4d, the O 1 s XPS spectrum was deconvoluted into five peaks, including adsorbed oxygen (Oadsorbed), unsaturated oxygen (Ovacancy), and three Ir-O peaks (where μ1-O, μ2-O, and μ3-O represent oxygen coordinated with 1, 2, and 3 Ir atoms, respectively). Notably, the μ1/μ2 ratio of IrO2(101) monolayer is calculated to be as low as 0.41, which is typical of a rutile-type structure54. Both Ir 4 f and O 1 s XPS results demonstrate that IrO2(101) monolayer primarily exists in the rutile-type crystal structure.

Raman scattering is a powerful technique to characterize 2D materials because of its strong sensitivity to the electronic structure. The peak positions of the Raman features are summarized in Supplementary Table 7. Interestingly, two major Raman peaks, namely the Eg and A1g modes for rutile IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2 are identified, respectively, while only an Eg peak is detected at 540.09 cm-1 in the Raman spectrum of IrO2(101) monolayer (Fig. 4e)55. The absence of the A1g peak in the 2D IrO₂ monolayer can be attributed to the symmetry reduction caused by dimensional confinement. In traditional rutile IrO₂ nanoparticles (3D, D4h symmetry), the A1g peak corresponds to oxygen octahedra vibrations along the c-axis. When reduced to a single-faceted monolayer (2D, C4v symmetry), the loss of periodicity along the c-axis eliminates the symmetry conditions required for the A1g vibration. In contrast, the Eg mode (in-plane Ir-O stretching) persists due to retained in-plane symmetry. This symmetry breaking directly suppresses the A1g peak, confirming the structural transition from 3D rutile nanocrystal to 2D rutile monolayer. Furthermore, the 2D monolayer nanostructure exhibits highest specific surface area of 353.8 m2 g-1, almost 3 and 50 times higher than that of nanoparticle counterpart (114.2 m2 g-1) and Comm IrO2 (7.7 m2 g-1), respectively. As shown in Fig. 4f, the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm of the IrO2(101) monolayer can be categorized as type IV with a hysteresis loop. The pore-size distribution further exhibits the presence of mesopores with an average diameter of 3.29 nm on the 2D monolayer (Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 8), which can be observed in the TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 21). This is attributed to the ammonia-induced pore-forming process19.

The coordination information of the 2D single-faceted monolayer structure was also corroborated by synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy using the Ir L3-edge. As shown in Fig. 5a, the X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy (XANES) curve of IrO2(101) monolayer is in good accordance with that of Comm IrO2, indicating a similarity in the rutile phase. Meanwhile, the XANES whiteline position for 2D IrO2 monolayer slightly shifts to higher energy compared to Comm IrO2. Combined with the first derivative of the Ir L3-edge in Supplementary Fig. 22, it indicates that the oxidation state of Ir species is slightly higher than +4. This result is also consistent with those measured from XPS analysis. Figure 5b compares the Fourier transform (FT) k2-weighted EXAFS spectra of IrO2(101) monolayer, Comm IrO2 and Ir foil. As a reference sample, Ir foil exhibits a strong peak at 2.7 Å, which corresponds to the Ir-Ir coordination56. In contrast to Ir foil, no obvious peaks of Ir-Ir coordination were detected in IrO2(101) monolayer. The scattering paths of the Ir centers in IrO2(101) monolayer and Comm IrO2 exhibit a prominent peak of Ir-O coordination at 2.00 and 1.97 Å, respectively. Accordingly, the Ir L3-edge EXAFS reveals that the length of the Ir-O bond in IrO2(101) monolayer is slightly longer than that of Comm IrO2. The increase in Ir-O bond length may be attributed to the lattice expansion induced by 2D monolayer structure and unsaturated coordination environment57,58. Furthermore, the WT-EXAFS (Wavelet Transform Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure) spectrum of IrO2(101) monolayer shows that the shell area for Ir-O scattering at R = 1.50 Å and k = 4.50 Å-1, and no shell area for Ir-Ir scattering is observed, implying neither Ir nanoclusters nor nanoparticles exist (Fig. 5c-e). The extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) results were further Fourier transformed to simulate the real crystal model of IrO2(101) monolayer. Figure 5f exhibits the fitting curve of a single (101) facet, which is perfectly reproduced by the experimental FT-EXAFS data. According to Ir L3-edge EXAFS fitting parameters in Supplementary Table 9, the coordination number (Ir-O) is about 5.9 and the bond length is about 2.00 Å. Combining the above XAFS results and previous studies, a schematic model of IrO2(101) monolayer is presented in Fig. 5g51,59,60. Each Ir atom coordinates with six O atoms to form a single layer of 2D rutile IrO2 crystal along (101) facet.

a Ir L3-edge XANES spectra of IrO2(101) monolayer, Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar) and Ir foil. b FT-EXAFS spectra of IrO2(101) monolayer, Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar) and Ir foil at Ir L3-edge. Corresponding wavelet transforms for the k2-weighted Ir L3-edge EXAFS signals of c IrO2(101) monolayer, d Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar), and e Ir foil. The color scale represents the wavelet transform signal intensity, with blue and black corresponding to high and low amplitudes, respectively. f The FT-EXAFS r space fitting curve of the crystal model in g. g Crystal structure of IrO2(101) monolayer. The refined structure model is simulated based on the XRD, FFT, and EXAFS analysis, Ir (yellow), O (red).

Ex-situ electrochemical characterization

In order to study the structural and performance advantages, the OER measurements of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2 (Alfa Aesar), Comm IrOX (Alfa Aesar) and Comm Ir black were initially carried out in a three-electrode configuration using 0.1 M HClO4 as the aqueous electrolyte14. All reference electrodes were calibrated before OER tests, and the calibration voltages in HClO4 and H2SO4 are 0.296 V and 0.247 V, respectively. As plotted in Fig. 6a, IrO2(101) monolayer displays the lowest overpotential of 227 ± 5 mV (n = 5) at a current density of 10 mA cmgeo-2, compared to 307, 311, 292, and 301 mV of IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2, Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black (Supplementary Fig. 23a). Even at 50 mA cmgeo-2, IrO2(101) monolayer maintains a low overpotential of 272 mV, nearly 200 mV lower than its nanoparticle counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 23b). The most active linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curve confirms that IrO2(101) facet plays the most vital role in optimizing the OER performance over other facets. Tafel slope is another important parameter to probe the response of IrO2 catalyst to the interfacial charge transfer towards the working potential. As depicted in Fig. 6b, IrO2(101) monolayer has the lowest Tafel slope of 44.73 mV dec-1 within the potential range of 1.45-1.47 V. For comparison, higher Tafel slopes are obtained by IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2, Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black, with delivering 83.06, 70.28, 65.19, and 80.97 mV dec-1, respectively. The OER kinetics on the (101) facet is much faster than those of nanoparticle counterparts, confirming that the 2D single-facet monolayer structure is more favorable for OER pathway61. The lower Tafel slope of IrO2(101) reveals that the RDS is related to the desorption of O2 species, rather than the adsorption of water molecules and their subsequent oxidation for other conventional catalysts, which aligns with the DFT calculations62. The kinetics of OER processes on IrO2(101) monolayer was further evaluated by EIS measurement (Supplementary Fig. 24 and Supplementary Table 10). Fitting EIS curves reveals that IrO2(101) monolayer has the smallest charge transfer resistance (RCT) of 10.32 ohm, compared to those measured for IrO2 NP (109.60 ohm), Comm IrO2 (88.49 ohm), Comm IrOX (25.25 ohm), and Comm Ir black (18.06 ohm). We attribute the lowest high frequency resistance to the maximized charge transfer process resulted from the monolayer thickness and highly oriented facet, which is the main origin of the superior OER performance. And Ohmic resistance (R) is calculated to be 21.92 ± 1.01 ohm (n = 5) from EIS measurements. To identify the origin of monolayer structural advantages in mass transfer, we quantified the surface superaerophobicity of IrO2 catalysts by assessing the adhesive force between bubbles and the surface (Supplementary Fig. 25). Interestingly, the adhesive force measured on the monolayer IrO2(101) surface was found to be merely 17.7 μN, featuring pronounced superaerophobicity in electrolyte. Employing IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar) as contrastive samples, the values of adhesive force were measured to be 52.4 μN and 32.0 μN, respectively. Therefore, the bubble release from the MEA surface of monolayer IrO2(101) seems to be easier in the solution, which can be attributed to the exceptionally low contact region between the bubbles and the uniform monolayer surface and thus low adhesive force63,64. Above results demonstrate that the fine construction of 2D monolayer interface featuring a specific facet simultaneously optimizes both its kinetic behavior and wetting behavior, thereby facilitating efficient charge and mass transfer from the IrO2 surface for OER.

a LSV curves of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar), Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black scanned at 5 mV s-1 in 0.1 M HClO4 with iR-correction. b Tafel plots of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar), Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black. c Corresponding mass activities of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar), Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black. d Chronoamperometry measurements of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2(Alfa Aesar), Comm IrOX, and Comm Ir black at a high constant potential of 1.6 V with online iR correction. Inset shows the degradation profiles during the initial 10 h. (R = 21.92 ± 1.01 ohm; GCE area: 0.196 cm2).

We further calculated the specific current densities at 1.50 V vs. RHE to study their OER performances. To present a comprehensive performance evaluation of different catalysts, the OER performances were evaluated by normalizing surface areas obtained using different approaches, such as GCE (glassy carbon electrode) geometric areas and electrochemically active surface areas (ECSA)14. IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits both the highest geometrical activity of 47.75 mA cmgeo-2 and ECSA-based activity of 0.027 mA cmECSA-2 at 1.50 V vs. RHE, nearly 10 times higher than those of IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2, Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black (Supplementary Fig. 26a, b). The methods to determine the ECSA-based surface areas of different catalysts and clean GCE using the non-iR corrected CV curves are summarized in Methods section (Supplementary Figs. 27, 28). In addition, the mass activities at 1.50 V vs. RHE were calculated to compare their intrinsic activities. By normalizing the Ir loading, rationally designed IrO2(101) monolayer performs 238.75 mA mgIr-1 at 1.5 V vs. RHE, almost 10 times higher than that of other rutile IrO2 (Fig. 6c). Here, we have adopted a multi-electrolyte cross-validation strategy to ensure the broader applicability and relevance of IrO2(101) monolayer to the electrocatalysis community. Both H2SO4 and HClO4 are widely used and accepted electrolytes in OER studies, each offering distinct advantages that correlate with the specific experimental conditions and systems under investigation. The complementary properties of H2SO4 (strong acidity, high ionic conductivity) and HClO4 (weak anion adsorption) enable systematic evaluation of the intrinsic activity trends across distinct electrochemical environments. By presenting results in two commonly used electrolytes, we aim to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the catalytic behavior and to make our work accessible to researchers working with either electrolyte. The OER performance of IrO2(101) monolayer was also evaluated using 0.5 M H2SO4 as the electrolyte65. IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits the lowest overpotential of 245 mV at the current density of 10 mA cmgeo-2, compared to 304, 344, 297 and 305 mV for IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2, Comm IrOX and Comm Ir black, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 29a). The Tafel slope of IrO2(101) monolayer in 0.5 M H2SO4 was measured to be only 47.47 mV dec-1 (Supplementary Fig. 29b). The difference in Tafel slopes of IrO2(101) monolayer and commercial IrO2 between 0.5 M H2SO4 and 0.1 M HClO4 arises from the synergy effect, with lower values typically observed in HClO4. First, SO42- exhibits strong adsorption via chemical binding to IrO2 surfaces, increasing charge transfer resistance and the Tafel slope. In contrast, weakly adsorbed ClO4- minimizes interfacial resistance, facilitating intrinsic OER kinetic and exhibiting a lower Tafel slope. Second, the higher H+ concentration in H2SO4 (1 M) hinders Step 2 (*OH → *O), which leads to a high Tafel slope, while the lower H⁺ concentration in HClO4 (0.1 M) mitigates this reaction barrier, resulting in a reduced Tafel slope. Third, the high ionic strength of H2SO4 (0.5 M) may induce a compact double-layer structure, potentially hindering H⁺ transport to the electrode surface. Conversely, the lower ionic strength of HClO4 (0.1 M) forms a more diffuse double layer, promoting rapid H⁺ transfer and resulting in a reduced Tafel slope. In addition, both mass activities and EIS results illustrate that IrO2(101) monolayer shows the highest intrinsic activity and lowest electron transfer resistance (Supplementary Fig. 29c, d). Above OER measurements conducted in 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte further demonstrate that the IrO2(101) facet provides an ideal catalytic platform for OER process by favoring mass transport, mechanical behavior, and even electron transfer. The catalyst exhibits high catalytic activity and stability in two different electrolytes, demonstrating the universality of the IrO2(101) monolayer.

In the nucleation and growth process, both NH3·H2O amount and temperature play vital roles in guiding the (101)-oriented growth of IrO2 nuclei at a monolayer thickness. A perfect IrO2(101) monolayer is predicted to possess highest electrocatalytic performance for OER compared to other traditional nanostructures, due to the ~100% exposure of the (101) facet on the monolayer. LSV curves reveal that IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits the lowest overpotential of 227 mV to attain a current density of 10 mA cmgeo-2, which is 80 mV, 36 mV and 22 mV lower, respectively, than its counterparts synthesized with NH3·H2O amounts of 0 g, 3.2 g and 12.8 g (Supplementary Fig. 30). Insufficient ammonization is unfavorable for the preferred orientation growth of the highly active (101) facet, whereas excessive ammonization may disrupt the orderliness and integrity of the (101) crystal facet. In terms of annealing temperature, the overpotential of IrO2(101)-350 and IrO2(101)-500 were measured to be 257 mV and 357 mV at 10 mA cmgeo-2, respectively, significantly higher than that of IrO2(101) monolayer (227 mV) (Supplementary Fig. 31). Thus, 450 oC is identified as the optimal temperature to favor the lateral growth of 2D monolayer structure.

In addition to activity, balancing the operating stability in acidic media poses another significant challenge when considering the structural stability at industrial-level current densities under practical OER condition10,66. In a three-electrode system, we evaluated the stability of the catalyst under constant potential (1.6 V) with online iR correction. After 92 h of testing, the current density of IrO2(101) monolayer maintains its initial value with no obvious decay, while IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2, Comm IrOX, and Comm Ir black show significant current decay within only 12, 10, 18, and 14 h, respectively (Fig. 6d). The inset further compares their degradation profiles during the initial 10 h, with the calculated results clearly showing that Comm IrOX (decay rate: 2.34 mA cm-2 h-1) exhibits faster degradation than Comm IrO2 (decay rate: 1.03 mA cm-2 h-1) during the initial 10 h. As for chronopotentiometry (CP) tests, both IrO2 NP and Comm IrO2 suffer from dramatically activity loss during 100 h while the working potential of IrO2(101) monolayer at 50 mA cmgeo-2 maintains a consistent value after 910 h (Supplementary Fig. 32). The inset in Supplementary Fig. 32 further exhibits that the linear polarization curves of IrO2(101) monolayer before and after the CP test perfectly overlap. The overpotential decay rate was calculated to be only 15 μV h-1, demonstrating the superior stability of IrO2(101) monolayer. It also operates stably at the high current of 200 mA cmgeo-2 during a 167 h stability test, confirming its great potential for commercial application (Supplementary Fig. 33). To provide a more objective perspective, the comparison of activity and stability between IrO2(101) monolayer and other state-of-the-art Ir-based catalysts is shown in Supplementary Table 1114,27,67,68,69,70,71,72. We also found that the 2D monolayer structure seems to be more insensitive to the working potential than previously reported nanostructured IrO2. For instance, a strong redox peak of IrIII/IV appears at 0.86 V vs. RHE once an anodic potential is applied, indicating that Ir3+ has been oxidized to Ir4+ or an even higher state (Supplementary Fig. 34a). Even after 10000 CV cycles, no obvious shift in the redox peak has been detected3. In comparison, both Comm IrO2 and Comm IrOX show larger redox peak shifts (25 mV and 90 mV) after cycling, confirming the enhanced stability of IrO2(101) monolayer (Supplementary Fig. 34c,d). The distinct cyclic voltammetry (CV) profiles of these catalysts can be attributed to the high double-layer capacitance of the Ti felt electrode, as evidenced in Supplementary Fig. 34e. The polarization curves and overpotentials of IrO2(101) monolayer before and after the 2,000th/10,000th CV cycles tests also prove that its activity loss is negligible despite being a 2D monolayer structure (Supplementary Fig. 35a, b). In order to be closer to real-life applications, we conducted 10,000 CV cycle tests within the higher voltage range of 1.2-1.8 V (Supplementary Fig. 34b). And there is no significant change in the polarization curve and overpotential before and after OER, indicating that IrO2(101) monolayer can still maintain high stability during cyclic operation at high voltages (Supplementary Fig. 35c, d).

To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the stability property of IrO2(101) monolayer, the inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) was further operated to calculate the dissolution amount of the Ir element after durability test at 1.6 V. From the ICP-OES data in Supplementary Table 12, the S-number for each IrO2 catalyst was calculated as the ratio of the molar amount of evolved O2 to the molar amount of dissolved Ir5. The S-number of IrO2(101) monolayer after OER was calculated to be 4.48 × 106, over 11, 40, 8 and 9 times higher than the S-numbers of IrO2 NP (4.02 × 105), Comm IrO2 (1.06 × 105), Comm IrOX (5.30 × 105) and Comm Ir black (4.95 × 105), respectively (Supplementary Table 13). In addition, IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits competitive stability compared to other recently reported Ir-based catalysts, including pristine Ir or Ir oxides (1 ~ 9.2×105)73, Ir-based alloys (5 ~ 2.49 × 105)10, and IrO2@TiO2 nanoparticles (1.0×104)74. Given the high current density and the superlong test time, the performance stability of 2D IrO2(101) monolayer in acidic media is further highlighted, pointing to its significant potential for commercialization even at monolayer thickness.

As shown in Supplementary Figs. 36 and 37, the monolayer structure and uniform (101) facet orientation of the IrO2(101) monolayer remain intact after ~1000 h stability test at 50 mA cmgeo-2. TEM analysis reveals an initial sheet-like morphology with no reconstructed nanoparticles or nanoclusters on the surface, and the lattice spacing remains consistent with the initial value. XRD characterization further confirms the presence of only a prominent (101) diffraction peak at 34.93°, without any signals from other rutile facets, demonstrating high stability in the crystallographic orientation during long-term operation. To gain insights into the electronic structure changes after the stability test, XPS analysis was performed. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 38, XPS spectrum of the IrO2(101) monolayer exhibits a slight blue shift of 0.15 eV compared to the initial state, suggesting the partial oxidation of surface Ir atoms under acidic OER conditions. Above characterizations after OER stability test confirm that the single-(101)-facet structure realizes a win-win strategy in terms of activity and stability, positioning IrO2(101) monolayer as a promising candidate for PEM applications.

In-situ electrochemical characterization

The catalyst research evolving from the simple modulation of IrO2 composition/size on the macroscopic scale to the precise design of IrO2 structure/morphology at the nanoscale suffers from the same corrosion problem stemming from the dissolution of IrO42- anions into the electrolyte66. In general, most previously reported high-performance OER electrocatalysts can only survive in a three-electrode system, while their activity loss usually becomes magnified in PEM devices after 100 h, which starkly contrasts with the stability results observed on GCE75. For the industrial application of PEM electrolyzers, searching an advanced IrO₂ material structure that can meet the technical targets for PEM electrolyzer—high current densities of 2 A cmgeo-2 at low overpotentials (≤1.9 V) and long-term stability exceeding 40,000 h at industrial-scale current density with a decay rate below 4.8 μV h-1—presents a great opportunity and challenge for a sustainable PEM future6,76,77. As a proof-of-concept of its commercial value, the OER performance of IrO2(101) monolayer was evaluated in PEM devices under various operating conditions (Supplementary Fig. 39). As depicted in Fig. 7a, the catalyst-coated membranes (CCMs) for PEMWE were prepared using IrO2(101) monolayer as the anode catalyst (1.5 mgIr cmgeo-2 or 0.2 mgIr cmgeo-2) and commercial Pt/C (0.3 mgPt cmgeo-2 or 0.2 mgPt cmgeo-2) as the cathode catalyst via spray coating on both sides of the Nafion 115 membrane. After assembly, MEAs with IrO2(101) monolayer were tested in a 4 cm2 active area PEMWE single cell at 80 °C and ambient pressure, with a preheated Milli-Q ultrapure water flow of 10 mL min-1 onto the anode.

a Schematic diagram of the PEM cell. H (yellow), O (red). b Cell voltage (Ecell) with respect to the current density with the anode loading of 1.5 mgIr cmgeo-2 and the cathode loading of 0.3 mgPt cmgeo-2. Inset shows I-V curves of IrO2(101) monolayer and Comm IrO2(Umicore) with a low anode/cathode loading of 0.2 mgIr/Pt cmgeo-2. c Electrolysis durability test of IrO2(101) monolayer with low Ir loading under simulated fluctuating conditions. d Electrolysis durability test of low-Ir-loading MEAs at a constant 1.5 A cm-2. e Comparison of PEM performance in this work with those in previous studies. f Electrolysis durability test of IrO2(101) monolayer under steady-state condition, which achieves over 10,000 h OER stability at a constant 1.5 A cm-2. PEM devices were carried out at 80 °C and ambient pressure.

IrO2(101) monolayer performs high PEM activity, achieving the standard current density of 2 A cmgeo-2 at a low potential of 1.70 V, significantly lower than Ecell of IrO2 NP (1.82 V@2 A cmgeo-2) and Comm IrO2 (1.84 V@2 A cmgeo-2), respectively (Fig. 7b). Additionally, lowing the Ir loading in CCMs below 0.5 mgIr cmgeo-2 is another crucial issue to meet the deployment and upscaling of PEM electrolyzers, which can be ascribed to the low abundance and extremely high cost ($4700 per oz in 2024)30,61. Thus, PEMWEs with low-Ir-loading MEA (0.2 mgIr cmgeo-2) were recorded to evaluate catalyst performance. Accordingly, the cathode loading was reduced from 0.3 mgPt cmgeo-2 to 0.2 mgPt cmgeo-2 to match the variation in anode loading, and this adjustment ensured a balanced electrode configuration. As shown in the inset of Fig. 7b, Ecell reaches 1.78 V at 2 A cmgeo-2 using low-Ir-loading MEA, which is comparable to the best PEMWEs employing the same MEAs with substantially higher Ir loadings (1 ~ 2 mgIr cmgeo-2)78,79,80. Meanwhile, considering the importance of high current performance in evaluating water electrolysis cells, we conducted additional I-V tests at high current density of 3-5 A cm-2 (Supplementary Fig. 40). Even at 4 A cm-2, IrO2(101) monolayer achieves a low voltage of 1.93 V, which is significantly lower than other advanced Ir-based catalysts1.

Demonstrating the catalyst stability in PEM device is a more challenging task than achieving high PEM activity. To date, most OER catalyst stabilities are still tested in a simple three-electrode system utilizing a low working current density below 200 mA cmgeo-2, which performs far from their practical working conditions. Although some recently reported catalysts have demonstrated operation in PEM systems for over 100 h at a constant current density of 1-2 A cmgeo-2, evaluating their comprehensive working stabilities in all aspects including the stability response to fluctuations in wind/solar energy inputs or low Ir loading, is easy to ignore6. Therefore, many high-performance OER electrocatalysts developed from academia often rest in the laboratory, while commercially available IrO2 is being explored to address technical problems encountered from real applications81. Compared to the steady-state condition, voltage fluctuation caused by wind or solar power can exacerbate Ir loss and even catalytic deterioration, ultimately compromising the overall PEM efficiency82,83. To bridge the research gap of stability tests, we use a square wave voltage toggling between 1.6 and 2.3 V to simulate the fluctuating power patterns of wind or solar photovoltaic sources84,85,86,87,88. Square wave cycling is chosen as it represents more severe testing conditions compared to constant potential or triangular wave protocols, accelerating catalyst stability assessment by promoting Ir dissolution through non-equilibrium processes. The potential range is selected to isolate catalyst degradation while avoiding excessively high potentials that degrade other components (the bipolar plate and porous transport layer) or extremely low potentials that risk hydrogen crossover and membrane damage. As depicted in Fig. 7c, Ecell over time was measured at 1.6 and 2.3 V for 1 min each. Notably, voltage switching exhibits little negative effect on PEM durability. According to the TEM image after PEM durability testing under fluctuating operating condition, IrO2(101) monolayer still maintains its initial 2D crystal structure, suggesting IrO2(101) monolayer remains both activity and structural advantages even after 1,000 h fluctuating testing (Supplementary Fig. 41).

As for steady-state condition, stability assessments of OER catalysts are typically conducted in a simple three-electrode or PEM system, where constant voltages are applied from external electrochemical workstation. This is a key criterion before we can commercialize it. When the current density reaches 3 A cm-2, challenges like gas bubbling, heat exchange, and hydrogen crossover become more pronounced in the PEM electrolyzer. These issues can interfere with measurements, thereby complicating objective evaluation. Consequently, most recent literature reports focus on testing at 1.5 or 1 A cm-2. To align with these studies and facilitate comparison with state-of-the-art research, we initially selected a current density of 1.5 A cm-2 for PEM tests. Figure 7d firstly compares the stability data of low-Ir-loading PEM electrolyzers. Even with Ir and Pt loading as low as 0.2 mg cmgeo-2, Ecell achieves over 2000 h stability without obvious activity loss at 1.5 A cmgeo-2. As shown in Fig. 7e and Supplementary Table 14, IrO2(101) monolayer not only meets part of the DOE technical standards but also shows competitive performance against previously reported catalysts in terms of both voltage efficiency and stability14,21,49,56,61,89,90,91,92. As evidenced in Fig. 7f, the IrO2(101) monolayer anode cell (1.5 mgIr cmgeo-2) maintains high OER stability of 10,217 h at 1.5 A cmgeo-2 with a negligible degradation rate of 3.95 μV h-1. In contrast, for Comm IrO2 and IrO2 NPs, their efficiency loss is drastically raised during the 500 h OER test, which may be attributed to the accelerated catalyst degradation. In order to meet the DOE criteria, an 800-hour constant current test was also conducted in PEM device at 3 A cm-2. The negligible activity loss (a voltage decay of 2.00 mV) indicates that IrO2(101) monolayer can maintain high stability even at a high current range (Supplementary Fig. 42). All these comprehensive stability tests confirm that IrO2(101) monolayer suffers less catalytic deterioration under both dynamic and constant power operation, despite its monolayer rutile (101) structure.

Discussion

Guided by theoretical calculations, we have successfully synthesized 2D single-faceted IrO2(101) monolayer based on an ammonia-induced preferred orientation growth. Both XRD characterization and TEM observation confirm that IrO2(101) monolayer possesses a monolayer rutile structure featuring a single (101) facet. The highly activated (101) facet presents a low overpotential of 237 mV at 10 mA cmgeo-2 in a three-electrode cell, and performs high PEM activity with a low Ecell of 1.70 V at 2 A cmgeo-2. Importantly, the practical operating stability of the IrO2(101) monolayer anode cell has been tested under various working conditions. Although IrO2 crystal is constructed in the monolayer limit along a unique growth orientation, IrO2(101) monolayer still meets part of the DOE durability targets for PEMWE. Under steady-state conditions, the long-term operation exceeds 10,000 h with a negligible decay rate of less than 3.95 mV kh-1. Even at a low Ir loading of 0.2 mg cmgeo-2, the PEMWE test for IrO2(101) monolayer anode maintains stability for over 2,000 h at a constant 1.5 A cm geo-2. When coupled with simulated fluctuating electricity from solar/wind power sources, IrO2(101) monolayer anode cell also achieves long-term stability exceeding 1000 h. This work proposes a phase engineering strategy for the design and synthesis of 2D single-(101)-faceted IrO2 at monolayer thickness, demonstrating outstanding OER activity and long-term PEMWE stability under both steady-state condition and fluctuating condition.

Methods

Chemicals

Dipotassium hexachloroiridate (K2IrCl6, 99.9%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar Co., Ltd. Iridium(IV) oxide (IrO2, 99%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Catalog No. 043396) and Umicore (Catalog No. 0685/29NB3) Co., Ltd. Ir Black (Ir, 99.9%) was purchased from Apinno Co., Ltd. Ammonium hydroxide (NH3·H2O, 25.0-30.0%) and isopropanol were purchased from Beijing InnoChem Science & Technology Co., Ltd. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95.0-98.0%), perchloricacid (HClO4, 70.0-72.0%), and Potassium nitrate (KNO3, ≥99.0) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Nafion solution (5 wt %) and Nafion N115 membrane (125 μm) was purchased from DuPont Co., Ltd. Other reagents used were of analytical grade without further purification. Deionized water, supplied by Thermo Scientific Smart2Pure 6 UV Water Purification System, was used throughout the experiments. The PEM device was purchased from China Titanium Guochuang (Qingdao) Technology Co.

Synthesis of 2D IrO2 (101) monolayer

All IrO2 catalysts were synthesized via a calcination approach in a muffle furnace. Initially, 240 mg of K2IrCl6 and 6.4 g of NH3·H2O were dissolved in 40 mL deionized water under ultrasonic treatment at 25 °C for 3 h. Subsequently, 4.848 g of KNO3 was introduced to the solution with stirring for 1 h. The mixture was then concentrated by heating at 80 °C under magnetic stirring until achieving a viscous slurry. The resulting precursor was transferred to a quartz boat and calcined in air at 450 °C (heating rate: 5 °C min-1) for 0.5 h, followed by natural cooling to room temperature. Finally, IrO2(101) monolayer was filtered, washed with deionized water, and vacuum-dried at 60 °C overnight, respectively. The comparison materials were prepared by varying the calcination temperatures from 350 °C to 500 °C, or modifying NH3·H2O volumes (0, 3.2, or 12.8 mL) during precursor preparation. Notably, IrO2 NP was synthesized specifically using 0 mL of NH3·H2O.

Characterization

The XRD patterns of all powder samples were recorded by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD, D8 Advance) at an operation voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA, using a Cu Kα radiation source. The powder samples were uniformly placed on a Glass slide. The TEM images and EDX data were characterized by a JEOL JEM-F200 transmission electron microscope with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. For TEM analysis, the powder samples were dispersed in ethanol and dropped onto a carbon film-supported copper grid. EDX analysis was performed with the same microscope using a Silicon Drift Detector (Oxford Instruments, X-MaxN 80 T, 150 mm2). AFM images were captured using the atomic force microscopy (AFM, Dimension ICON), where the powder samples were dispersed in ethanol and dropped onto a mica sheet. The XPS results were obtained with a Thermo Fisher ESCALAB 250Xi X-ray photoelectron spectrometer using an operation voltage of 12.5 kV and a filament current of 16 mA. The samples were prepared by placing the powders onto stainless steel substrates and securing them with double-sided adhesive. The excitation source used was Al Kα rays (hv = 1486.8 eV). The full spectrum scan pass energy was 150 eV with a step size of 1 eV, and the narrow scan pass energy was 50 eV with a step size of 0.1 eV. The charge correction was based on C 1 s at 284.80 eV as the energy reference. The BET specific surface areas were characterized using a Micromeritics 3Flex (Version 5.00). The powder samples were degassed at 120°C for 6 h under a vacuum before the measurement. Raman spectra were measured using a Laser Microscopic Confocal Raman Spectrometer (inVia™, Renishaw) under excitation by laser light at λ = 532 nm. The powder samples were placed onto a glass slide for the measurement. XAFS measurements were carried out in transmission mode at the 1W1B beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF). A Si(111) double-crystal monochromator was employed to adjust the incident photon energy. The storage ring operated at 2.5 GeV with a beam current of approximately 200 mA. Beam intensity was monitored using an ionization chamber filled with a gas mixture of 25% Ar and 75% N2 for Ir L3-edge measurements. Iridium foil was measured and used as a reference for energy calibration in transmission mode. The powder samples were uniformly spread onto a sample holder. Data were analyzed with the ATHENA and ARTEMIS (version 0.9.26) modules of the IFEFFIT software package. The EXAFS functions were Fourier transformed to R-space with a k-weight of 2, within the range of 3.16-12.40 Å-1, using a Hanning window (dk = 1.0 Å-1). The X-ray fluorescence (XRF) measurements (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) were performed using a spectrometer equipped with an Rh anode X-ray source (50 kV, 25 mA). The Ir Lα (9.17 keV) and Pt Lα (9.44 keV) emission lines were acquired for 60 s per point with a 1 mm beam spot. The commercial IrO2 used in characterization experiments was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Catalog No. 043396).

Electrochemical measurements

All glassware was cleaned with laboratory-grade detergent, rinsed three times with deionized water and dried at 80°C before each experiment. All electrochemical experiments in three electrode system were carried out using the CHI760E electrochemical workstation (CH Instrument Co., Ltd.). The commercial IrO2 used in three electrode system was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Catalog No. 043396). The glassy carbon electrode (GCE area: 0.196 cm2) was used as the working electrode, calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode, and platinum gauze was used as the counter electrode, all electrodes were purchased from Tianjin Aida Co., Ltd. OER measurements were conducted in 60 mL O2-saturated 0.1 M HClO4 (pH = 0.95 ± 0.03) or 0.5 M H2SO4 (pH = 0.35 ± 0.05) electrolyte. The electrolytes were prepared by gradually adding concentrated acid to deionized water under continuous stirring. Prepared electrolytes were stored in airtight glass containers at room temperature. The calibration was performed by using a Pt foil as the working electrode, the calomel electrode as the reference electrode and Pt gauze as the counter electrode in a H2-saturated electrolyte (0.1 M HClO4 or 0.5 M H2SO4). All OER potentials were calibrated with respect to RHE scale by averaging the electrode potentials at zero current density in cyclic voltammetry scans. For measurement with iR-correction, R referred to the ohmic resistance arising from the electrolyte/contact resistance of the setup. The scan rate was set to 2.00 mV s-1 for both LSV measurements ranging from 1.10 to 1.60 V vs. SCE, and Tafel plot measured from 1.10 to 1.40 V vs. SCE. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) tests were conducted with a frequency range from 10 Hz (low frequency) to 100 kHz (high frequency); a corresponding equivalent circuit and fitting resistance value were analyzed by ZSimpWin Software Analysis. Chronoamperometry measurements were performed using the Chronoamperometry mode on the CHI760 electrochemical workstation, with the potential set to a constant value of 1.60 V vs. RHE with online iR correction. Chronopotentiometry measurements were performed using the Chronopotentiometry mode, with the current set to constant values of 50 or 200 mA cm-2. Cyclic voltammetry was performed using the CV mode on the CHI760 electrochemical workstation. The mass activities and ECSA-based specific activities of the catalysts were calculated based on the catalyst mass and electrochemical active surface areas (ECSAs) on the glassy carbon electrodes, respectively. The catalyst inks were obtained by mixing 4.0 mg IrO2 catalyst in a solution of 800 μL isopropanol, 200 μL deionized water, and 40 μL Nafion solution (5 wt%), with sonication to form the homogeneous catalyst ink. Then, 10 μL of the ink was dispersed on the GCE with drying naturally for testing (Ir loading: 0.2 mgIr cm-2). In the stability test, Ti felt (area: 1×1 cm2, Bekaert Co., Ltd., Catalog No. 2GDL10) was used as the working electrode, and 0.1 M HClO4 saturated with O2 was used as the electrolyte. The homogeneous catalyst ink was formed by ultrasonic mixing of 5.0 mg catalyst in 500 μL isopropanol, 500 μL deionized water and 10 μL Nafion solution (5 wt%, DuPont Co., Ltd.). 200 μL of ink was dispersed on the Ti felt (Ir loading: 1.0 mgIr cm-2).

For the PEM experiments, the anode catalyst ink was prepared by mixing 10 mg of IrO2 catalyst with 108 μL of deionized water, 1327 μL of isopropanol, and 44.4 μL of 5 wt% Nafion solution. The commercial IrO2 used in PEM experiments was purchased from Umicore (Catalog No. 0685/29NB3). The cathode catalyst ink was prepared by mixing 10 mg of Pt/C catalyst (TKK Co., Ltd.) with 128 μL of deionized water, 1528 μL of isopropanol, and 95.3 μL of 5 wt% Nafion solution. Both inks were then thoroughly mixed using an ultrasonic bath (Kunshan Ultrasonic Instruments Co., Ltd.) and a cell disruptor (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). After stirring for over 24 h, the catalyst ink was uniformly sprayed on the central 2.5×2.5 cm2 area of the N115 proton exchange membrane (Ir loading: 0.2 or 1.5 mgIr cm-2) at 90 °C using ultrasonic spraying machine (Suzhou Xifeng Automation Co., Ltd.). Nafion N115 membranes were separately treated with H2O2, H2SO4 and deionized water at 80°C before spraying. Carbon paper (Toray Co., Ltd. Catalog No. TGP-H-090) and Ti felt were pressed on the outside of the catalytic layer using a hot press (Dongguan Donghe Machinery Equipment Co., Ltd.) at a pressure of 450 kg and a temperature of 140 °C for ten minutes. The anode and cathode loadings of MEAs were calibrated using XRF spectroscopy by placing part of the catalyst-sprayed proton exchange membrane on the sample stage and measuring the Ir and Pt mass, then calculating the loading based on the measured area.

After the MEA was prepared, PTFE sealing materials (Chemours Co., Ltd.) and Ti bipolar plates (Zhongtai Guochuang Technology Co., Ltd.) were assembled around the MEA to form an electrolyzer. For all PEM tests, deionized water was used as the electrolyte at a flow rate of 18.2 ml min-1, with a working temperature of 80 °C, and voltage was supplied by an NGI programmable DC power source (Enzhi (Shanghai) Measurement and Control Technology Co., Ltd). The I-V curve was measured from 0 to 3.00 A cm-2, with 25 current points, each held for 30 seconds. Steady-state tests were conducted using a cross-flow configuration at 1.50 A cm-2. Non-steady-state tests were conducted using a square wave pattern with voltages of 1.60 V and 2.30 V, each held for 1 min. The XRD, XPS, and TEM results of IrO2(101) monolayer after the stability test were obtained by analyzing the used MEAs.

The ECSAs of IrO2 were estimated from double-layer capacitance (CDL) and specific capacitance (CS) using the following equation:

The electrochemical double-layer capacitance (CDL) at non-Faradic potential range was obtained by measuring the capacitance of double layer at solid-liquid interface employing cyclic voltammetry (CV) with different scan rates (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 70 mV s-1) in a range from 1.25 to 1.35 V vs. RHE.

The CS value was found to be 0.036 mF cm-2 in 0.1 M HClO4 electrolyte using a polished glassy carbon-rotating disk electrode from the CV curves in Supplementary Fig. 27. The CDL values of IrO2(101) monolayer, IrO2 NP, Comm IrO2, and Comm Ir black were estimated from the CV curves in Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28.

DFT calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)93,94,95,96. The interactions between ion cores and valence electrons were described using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method97,98. For the exchange-correlation functional, we employed the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation99. The wave functions at each k-point were expanded using a plane wave basis set, with the kinetic energy cutoff set to 500 eV. Geometric optimizations were performed using a force-based conjugate gradient method until the energy converged to 1.0 × 10-5 eV per atom, with the maximum force on each atom less than 0.05 eV Å-1. To account for long-range van der Waals interactions, Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction was implemented100,101.

The crystal structures of rutile-IrO2 were used to construct slab models for the electrocatalytic study. Periodic slab models of the IrO2(110), (200), and (101) facets were constructed using 2 × 1, 2 × 2, and 1 × 2 surface supercells, respectively, each comprising four metal-oxide layers. The bottom layer was constrained to maintain bulk-like properties. A vacuum space of 15 Å was introduced between the slab and its periodic image to minimize inter-slab interactions. To evaluate the activity of the electrocatalysts, we estimated the free energy diagram using the following equation102:

where ΔG is the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔE represents the total energy change derived from DFT calculations, ΔZPE is the change in zero-point energy, ΔS denotes the entropy change, and T is the temperature (298.15 K).

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available within the article, Supplementary Information, Source Data, and from the corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper. The source data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28189622. Received: ((will be filled in by the editorial staff)) Published online: ((will be filled in by the editorial staff))

References

Liu, R.-T. et al. Recent advances in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 5652–5683 (2023).

Song, J. et al. A review on fundamentals for designing oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2196–2214 (2020).

Suen, N.-T. et al. Electrocatalysis for the oxygen evolution reaction: recent development and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 337–365 (2017).

Chatenet, M. et al. Water electrolysis: from textbook knowledge to the latest scientific strategies and industrial developments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 4583–4762 (2022).

Tao, H. B. et al. The gap between academic research on proton exchange membrane water electrolysers and industrial demands. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1074–1076 (2024).

Knöppel, J. et al. On the limitations in assessing stability of oxygen evolution catalysts using aqueous model electrochemical cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 2231 (2021).

Shi, Q., Zhu, C., Du, D. & Lin, Y. Robust noble metal-based electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3181–3192 (2019).

Zhu, W. et al. Stable and oxidative charged Ru enhance the acidic oxygen evolution reac-tion activity in two-dimensional ruthenium-iridium oxide. Nat. Commun. 14, 5365 (2023).

Wu, D. et al. Efficient overall water splitting in acid with anisotropic metal nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 12, 1145 (2021).

Li, R. et al. IrW nanochannel support enabling ultrastable electrocatalytic oxygen evolution at 2 A cm-2 in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 12, 3540 (2021).

Shan, J. et al. Transition-Metal-Doped RuIr Bifunctional Nanocrystals for Overall Water Splitting in Acidic Environments. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900510 (2019).

Oh, H.-S. et al. Electrochemical Catalyst-Support Effects and Their Stabilizing Role for IrOX Nanoparticle Catalysts during the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12552–12563 (2016).

Seitz, L. C. et al. A highly active and stable IrOX/SrIrO3 catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction,. Science 353, 1011–1014 (2016).

Dang, Q. et al. Iridium metallene oxide for acidic oxygen evolution catalysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6007 (2021).

Fan, Z. et al. Extraordinary acidic oxygen evolution on new phase 3Riridium oxide. Joule 5, 3221–3234 (2021).

Alia, S. M. et al. Iridium-based nanowires as highly active oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 3 (2018).

Lee, S. et al. Activated chemical bonds in nanoporous and amorphous iridium oxides favor low overpotential for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 3171 (2022).

Xu H. et al. Iridium-based electrocatalysts for the acidic oxygen evolution reaction: engineering strategies to enhance the activity and stability. Mater. Chem. Front., 1248–1267 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Nanoporous IrO2 catalyst with enhanced activity and durability for water oxidation owing to its micro/mesoporous structure. Nanoscale 9, 9291–9298 (2017).

Lee, Y. et al. Synthesis and activities of rutile IrO₂ and RuO₂ nanoparticles for oxygen evolution in acid and alkaline solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 399–404 (2012).

Lim, J. et al. Ultrathin IrO2 nanoneedles for electrochemical water oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1704796 (2018).

Lim, J. et al. Amorphous Ir atomic clusters anchored on crystalline IrO₂ nanoneedles for proton exchange membrane water oxidation,. J. Power Sources 524, 231069 (2022).

Zhu, J.-Y. et al. Iridium nanotubes as bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution and nitrate reduction reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 14064–14070 (2020).

Zu, L. et al. Self-Assembly of Ir-Based Nanosheets with Ordered Interlayer Space for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2208–2217 (2022).

Jiang, B. et al. Mesoporous metallic iridium nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12434–12441 (2018).

Liao, F. et al. Iridium oxide nanoribbons with metastable monoclinic phase for highly efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 1248 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Iridium single atoms incorporated in Co3O4 efficiently catalyze the oxygen evolution in acidic conditions. Nat. Commun. 13, 7754 (2022).

Hua, K. et al. Catalytic activity of nanometer-Sized Ir–Ox catalysts with different coordination numbers for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 487–497 (2024).

Hua, K. et al. Integrating atomically dispersed Ir sites in MnCo2O4.5 for highly stable acidic oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 14, 3712–3724 (2024).

Ouimet, R. J. et al. The role of electrocatalysts in the development of gigawatt-scale PEM electrolyzers. ACS Catal. 12, 6159–6171 (2022).

Lee, Y., Suntivich, J., May, K. J., Perry, E. E. & Shao-Horn, Y. Synthesis and activities of rutile IrO2 and RuO2 nanoparticles for oxygen evolution in acid and alkaline solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 399–404 (2012).

Stoerzinger, K. A., Qiao, L., Biegalski, M. D. & Shao-Horn, Y. Orientation-dependent oxygen evolution activities of rutile IrO2and RuO2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 1636–1641 (2014).

Zagalskaya, A. & Alexandrov, V. Role of defects in the interplay between adsorbate evolving and lattice oxygen mechanisms of the oxygen evolution reaction in RuO2 and IrO2. ACS Catal. 10, 3650–3657 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. A Highly Active, Long-lived oxygen evolution electrocatalyst derived from open-framework iridates. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208539 (2023).

Kim, K.-S. et al. Promoting oxygen evolution reaction induced by synergetic geometric and electronic effects of irco thin-film electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 12, 6334–6344 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Exclusive strain effect boosts overall water splitting in PdCu/Ir core/shell nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 8243–8250 (2021).

Li, L., Xia, Y., Zeng, M. & Fu, L. Facet engineering of ultrathin two-dimensional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 7327–7343 (2022).

Sun, S., Gebauer, D. & Cölfen, H. A solvothermal method for synthesizing monolayer protected amorphous calcium carbonate clusters. Chem. Commun. 52, 7036–7038 (2016).

Sasikala, S. P., Poulin, P. & Aymonier, C. Advances in subcritical hydro-/solvothermal processing of graphene materials. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605473 (2017).

Yang, J. et al. Formation of two-dimensional transition metal oxide nanosheets with nanoparticles as intermediates. Nat. Mater. 18, 970–976 (2019).

Hambley, T. W. & Lay, P. A. Comparisons of.pi.-bonding and hydrogen bonding in isomorphous compounds: [M(NH3)5Cl]Cl2 (M=Cr, Co, Rh, Ir, Ru, Os). Inorg. Chem. 25, 4553–4558 (1986).

Kim, S. W. et al. Two-dimensionally grown single-crystal silicon nanosheets with tunable visible-light emissions. ACS Nano 8, 6556–6562 (2014).

Jung, W. et al. Colloidal synthesis of single-layer MSe2 (M = Mo, W) nanosheets via anisotropic solution-phase growth approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 17, 7266–7269 (2015).

Huang, X. et al. Freestanding palladium nanosheets with plasmonic and catalytic properties. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 28–32 (2011).

Albani, M. et al. Competition between kinetics and thermodynamics during the growth of faceted crystal by phase field modeling. Phys. Status Solidi B 256, 1800518 (2019).

Wulff, G. XXV. zur frage der geschwindigkeit des wachsthums und der auflösung der krystallflächen. Z. Krist.-cryst. Mater. 34, 449–530 (1901).

Cahn, J. W. & Carter, W. C. Crystal shapes and phase equilibria: A common mathematical basis. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 27, 1431–1440 (1996).

Sun, W., Song, Y., Gong, X.-Q., Cao, L. -m & Yang, J. An efficiently tuned d-orbital occupation of IrO2 by doping with Cu for enhancing the oxygen evolution reaction activity. Chem. Sci. 6, 4993–4999 (2015).

Zhuang, L. et al. Porous structure engineering of iridium oxide nanoclusters on atomic scale for efficient pH-universal overall water splitting. Small 17, 2100121 (2021).

Hao, S. et al. Torsion strained iridium oxide for efficient acidic water oxidation in proton exchange membrane electrolyzers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1371–1377 (2021).

Kwon, S. et al. Facet-dependent oxygen evolution reaction activity of IrO2 from quantum mechanics and experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11719–11725 (2024).

Sanchez Casalongue, H. G. et al. In situ observation of surface species on iridium oxide nanoparticles during the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7169–7172 (2014).

Kasian, O. et al. Degradation of iridium oxides via oxygen evolution from the lattice: correlating atomic scale structure with reaction mechanisms. Energ. Environ. Sci. 12, 3548–3555 (2019).

Roiron, C., Wang, C., Zenyuk, I. V. & Atanassov, P. Oxygen 1s X-ray Photoelectron Spectra of Iridium Oxides as a Descriptor of the Amorphous-Rutile Character of the Surface. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 11217–11223 (2024).

Korotcov, A. V., Huang, Y. S., Tiong, K. K. & Tsai, D. S. Raman scattering characterization of well-aligned RuO2 and IrO2 nanocrystals. J. Raman Spectrosc. 38, 737–749 (2007).

Wang, C. et al. Engineering lattice oxygen activation of iridium clusters stabilized on amorphous bimetal borides array for oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 27126–27134 (2021).

Yu, H. et al. Strain-triggered distinct oxygen evolution reaction pathway in two-dimensional metastable phase IrO2 via CeO2 loading. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 20251–20262 (2024).

Meng, G. et al. Strain regulation to optimize the acidic water oxidation performance of atomic-layer IrOX. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903616 (2019).

Matz, O. & Calatayud, M. Periodic DFT Study of rutile IrO2: Surface reactivity and catechol adsorption. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 13135–13143 (2017).

Albertin, S. et al. Oxidation and reduction of Ir(100) studied by high-energy surface X-ray diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 5244–5255 (2022).

Retuerto, M. et al. Highly active and stable OER electrocatalysts derived from Sr2MIrO6 for proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Nat. Commun. 13, 7935 (2022).

Fang, Y.-H. & Liu, Z.-P. Tafel kinetics of electrocatalytic reactions: From experiment to first-principles. ACS Catal. 4, 4364–4376 (2014).

Liang, J. et al. Efficient bubble/precipitate traffic enables stable seawater reduction electrocatalysis at industrial-level current densities. Nat. Commun. 15, 2950 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Systematic design of superaerophobic nanotube-array electrode comprised of transition-metal sulfides for overall water splitting. Nat. Commun. 9, 2452 (2018).

Jebaslinhepzybai, B. T., Partheeban, T., Gavali, D. S., Thapa, R. & Sasidharan, M. One-pot solvothermal synthesis of Co2P nanoparticles: An efficient HER and OER electrocatalysts. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46, 21924–21938 (2021).

Loncar, A., Escalera-Lopez, D., Cherevko, S. & Hodnik, N. Inter-relationships between oxygen evolution and iridium dissolution mechanisms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114437 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. KIr4O8 nanowires with rich hydroxyl promote oxygen evolution reaction in proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402643 (2024).

Abdullah, M. I. et al. Tackling activity-stability paradox of reconstructed NiIrOX electrocatalysts by bridged W-O moiety. Nat. Commun. 15, 10587 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Inverse doping IrOX/Ti with weakened Ir-O interaction toward stable and efficient acidic oxygen evolution. Chem 9, 2931–2942 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalysis in acid by a perovskite with face-sharing IrO6 octahedral dimers. Nat. Commun. 9, 5236 (2018).