Abstract

Digital light processing 3D printing is a powerful manufacturing technology for shaping materials into complex geometries with high resolution. However, the rheological and chemical requirements for printing limit the use of materials to photoactive resins. Here, we propose a versatile manufacturing platform for constructing versatile materials using DLP-printed water-soluble granular polyacrylamide as sacrificial molds. The polymerization-induced phase separation during printing results in a close packed granular geometry with intrinsic micropores, which greatly accelerates the dissolution rate of polyacrylamide. Combined with precise control over the molecular weight, this salt-like sacrificial mold can be fully dissolved in neutral water at room temperature within 30 min. Furthermore, significant surface oxygen inhibition promotes the leveling and spreading of liquid resin on the cured part surfaces, achieving a printing speed of 375 mm/h in a top-down printer. Due to the mild conditions for mold removal, complex-shaped architectures can be created from a variety of compositions, including temperature-sensitive low-melting alloys, alkaline-degradable polyesters, as well as widely used materials such as silicone rubber, polyurethane, polyolefin elastomer, and epoxy. Considering the fast mold dissolution rate and mild dissolution conditions, the present platform represents a potential low-cost, and universal indirect 3D printing method for shaping versatile materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM), often referred to as 3D printing, has emerged as a transformative technology capable of creating products with intricate geometries by depositing materials layer by layer based on computer-aided design (CAD) model data. Compared with traditional manufacturing methods such as cutting, drilling, or casting, 3D printing facilitates the efficient production of customized items in low volumes, while also providing extensive design flexibility1,2. Various 3D printing techniques, including fused deposition modeling (FDM)3, inkjet printing4, selective laser sintering (SLS)5, digital light processing (DLP)6,7,8, stereolithography (SLA)9, and direct ink writing (DIW)10, have been developed to enable the customized fabrication of polymer products. Among these techniques, light-based fabrication techniques (DLP and SLA) are typically favored for generating high-resolution, complex structures in largely unconstrained geometries. However, these techniques operate based on highly specialized chemical reactions, primarily radical-initiated polymerization of acrylates or cationically initiated acrylate/epoxy hybrid systems11,12, resulting in printed products with overly restricted functionality that cannot be adapted to a wider range of application scenarios.

Within a category of methods commonly referred to as “indirect 3D printing”, the 3D printer is employed to produce sacrificial molds that are subsequently infused or filled with a secondary material and later dissolved or extracted. Indirect 3D printing presents a compelling alternative approach, facilitating the fabrication of complex 3D structures using materials that are challenging to process through direct 3D printing methods. This is particularly relevant for thermosetting materials such as silicones13, polyurethanes14, and epoxies15, which typically require thermal curing mechanisms. To enable their direct 3D printing, these materials must undergo chemical modification through the introduction of photoactive acrylate functional groups. Similarly, metal or ceramic 3D printing necessitates complex post-processing procedures involving debinding and sintering after the initial printing stage16. The chemical modification approach fundamentally alters the material’s intrinsic properties and functionality. An ideal indirect 3D printing process should meet the following criteria: it should feature a high printing speed for the mold to compensate for the extended preparation cycle caused by additional steps, and it should employ mild mold removal conditions to match various target materials, preferably avoiding harsh conditions such as high temperatures or acidic/basic environments.

Recent years have witnessed advancements in indirect 3D printing using light-curing techniques. Initially, various hydrolysable di(meth)acrylates were synthesized and introduced into the liquid resin as cleavable crosslinkers. The hydrolysable bonds employed include diacetal/acetal bonds, hindered urea bonds, ester bonds, etc17,18,19. In addition to requiring complex molecular design, the molds produced by the above cleavable crosslinkers typically necessitate hydrolysis under acidic or alkaline conditions at temperatures as high as 90 °C. Consequently, they are unsuitable for molding temperature-sensitive materials, such as wax and low-melting-temperature alloys, or acid/alkali-sensitive materials, such as polyesters. Another potential approach is to print dissolvable thermoplastics as sacrificial molds20. Deng reported the first successful DLP printing of thermoplastic molds using a hydrophilic monomer (4-acryloylmorpholine) without any crosslinker21, however, the dissolution of the molds still requires high temperatures and extended periods. Alternatively, Kleger utilized salts as leachable molds, which were printed using photocurable resins loaded with NaCl particles22. Although salt molds can be dissolved in water at room temperature, the potential instability of the resin caused by particle sedimentation and the complex post-processing steps including debinding and sintering pose challenges to their practical application.

Polymerization-induced phase separation (PIPS) can introduce intrinsic micro- or nanoscale porous structures during polymerization23,24,25. The resulting porous structure facilitates solvent diffusion and interaction with the polymer. Previous work combining PIPS with DLP printing typically results in crosslinked thermosets, as it is considered that crosslinking is necessary to meet the rapid gelation requirements of 3D printing26,27,28. Here, we successfully achieved DLP printing of non-crosslinked granular polyacrylamide through PIPS. By controlling the degree of phase separation and molecular weight, the printed polyacrylamide exhibits a salt-like ability to dissolve rapidly in neutral water at room temperature, making it ideal for use as a sacrificial mold in indirect printing. In addition, we found that the formulated acrylamide resin can be printed at a speed of 375 mm/h, which is highly advantageous for the practical application of this manufacturing platform.

Results and Discussion

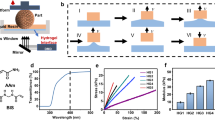

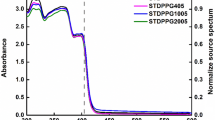

Acrylamide (AAm) is a common hydrophilic monomer, and its aqueous solution can polymerize to obtain a soft transparent hydrogel. Typically, a crosslinking agent, such as N,N’-Methylenebisacrylamide (BIS), is essential to form a crosslinked network that maintains structural and mechanical stability. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) is a high-affinity solvent for acrylamide but a nonsolvent for polyacrylamide. When acrylamide is dissolved in a DMF/H₂O mixed solvent, it can undergo polymerization-induced phase separation initiated by free radicals. If a photo-initiator such as diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phosphine oxide (TPO) is used, this process can be compatible with high-precision stereolithographic printing techniques, such as DLP (Fig. 1a). When using a DMF/H₂O mixed solvent, rapid gelation can occur (5 s for a slice thickness of 100 μm, light intensity: 14.7 mw/cm2), achieving considerable gel strength and modulus (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Table 1), which is highly beneficial for the layer-by-layer printing process (Fig. 1b). The printing resolution can be 400 μm using a commercial DLP printer (Supplementary Fig. 1). Unexpectedly, this process does not require a chemical crosslinker, which is completely different from the traditional design of polyacrylamide hydrogels. This effect likely arises from the phase separation process, in which linear polyacrylamide polymer chains precipitate out of the solvent, self-assembling into a granular microstructure. The granules then fuse at their interfaces to form a continuous, rigid polymer framework (Fig. 1c). The content of monomer acrylamide was fixed at 50 wt%, and different formulations were labeled as AAm50-DMFX (where X represents the mass fraction of DMF in the mixed solvents). Transmittance measurements revealed a decrease in average transmittance from 93.0% (AAm50-DMF0) to 7.1% (AAm50-DMF100) as the DMF ratio increased (Fig. 1e). This indicates that the phase separation domain size expanded with the higher DMF fraction, resulting in stronger light scattering. It should be noted that when the DMF content is reduced to a certain level (AAm50-DMF0 or AAm50-DMF10), phase separation becomes minimal or does not occur. Due to the absence of a crosslinker, the cured product remains a flowable sol. In addition, with the increase of DMF ratio in the mixed solvent, the cured material transitions from a soft, stretchable gel to a high-modulus plastic (Fig. 1d). The higher modulus results from a higher degree of phase separation, which corresponds to the microstructure observed in the cured samples (Fig. 1f). The mercury intrusion test revealed a porosity of 47.84% for AAm50-DMF100, which aligns closely with the amount of solvent used (50 wt%), indicating a high degree of phase separation and minimal retention of DMF solvent within the PAAm granules. Considering the higher modulus (68.49 MPa), which facilitate stable high precision printing, as well as the high degree of phase separation and larger pore size, which benefit subsequent dissolution, we selected AAm50-DMF100 for further study.

a Illustration of the DLP printing process and the formulations. b Complex-shaped structures printed with AAm50-DMF100. c Schematic of the polymerization-induced phase separation process. d The stress-strain curves of different formulations. e Transmittance of gels with different DMF weight ratios, tested without dye, thickness: 500 μm. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD (n = 3). f SEM images of gels with different DMF weight ratios.

Indirect printing essentially involves two processes: printing of sacrificial molds and casting of another material. Therefore, for indirect printing to have greater advantages in practical applications, one prerequisite is the ability to increase the printing speed. Here, we use a top-down DLP printing technique. For this process, the rate-limiting step for overall printing speed is the leveling of the liquid resin on the surface of the cured solid material after each exposure. Typically, this process is very slow and may even require the use of a blade to actively aid in leveling. The viscosity of the AAm50-DMF100 liquid resin is only 15 cP, which is at least one order of magnitude lower than that of commercial resins, demonstrating exceptional flowability. Additionally, a pronounced oxygen inhibition effect is observed during polymerization, whereby oxygen from the air above the resin creates an uncured liquid layer. This transition from a solid to a liquid surface reduces interfacial tension, facilitating enhanced resin wetting and spreading. We first qualitatively investigated the wetting behavior of the liquid resin on several different surfaces, including a non-phase-separated AAm50-DMF0 gel (sample i), a phase-separated AAm50-DMF100 gel cured in the absence of oxygen (sample ii), and a phase-separated AAm50-DMF100 gel cured in open air (sample iii). It is clear that the phase-separated surface (with a porous microstructure indicating the presence of a large amount of free solvent) and the fully inhibited surface both facilitate rapid wetting of the liquid resin, with the latter being more pronounced (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Movie 1, 2, 3). The inhibition depth of AAm50-DMF100 liquid resin (the total resin thickness is 100 μm) was tested under different irradiation energies (Fig. 2b). At an irradiation intensity of 14.7 mW/cm², the inhibition depth decreased as irradiation time increased (Fig. 2c). With sufficiently long irradiation, the resin fully cured, and no distinct liquid inhibition layer was observed. When the irradiation time was fixed at 5 seconds, the inhibition layer thickness was approximately 26 μm. In this inhibition layer, the polymerization reaction is severely inhibited, with most acrylamide existing as monomers or low-molecular-weight oligomers (Fig. 2d). Beyond this inhibition layer, acrylamide rapidly polymerized to form high-molecular-weight polymer chains, with a molecular weight of approximately 70 kg/mol. The molecular weight of the cured material at the very bottom slightly decreases, likely due to the material becoming opaque from phase separation, which hinders further light penetration. Based on these results, we achieved a printing speed of 375 mm/h on a custom-built top-down DLP printer, without the need for blade-assisted leveling (Supplementary Movie 4). In fact, the printing speed could be further increased by using a higher-powered light source or more stable, high-speed hardware21.

a The wettability of different precursor liquids. Images were captured 0.5 s after droplet contact with the surface. i: a non-phase-separated AAm50-DMF0 gel. ii: a phase-separated AAm50-DMF100 gel cured in the absence of oxygen. iii: a phase-separated AAm50-DMF100 gel cured in open air. b Illustration of the decay of surface inhibition along the Z-axis depth in a cured resin layer. c The effect of irradiation time on the depth of inhibition. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD (n = 5). d Depth profile of the molecular weight. Irradiation time: 5 s. Data are presented as mean values +/- SD (n = 3). e Rapid printing with a printing speed of 375 mm/h.

Another criterion for evaluating the effectiveness of indirect printing is the dissolution speed and conditions of the printed sacrificial mold. High temperatures, acidic, or alkaline conditions can all affect the compatibility between the mold and the casting material. The excellent water solubility of non-crosslinked polyacrylamide, along with its granular microstructure, facilitates rapid mold removal. This is somewhat similar to a salt mold, but with significantly reduced processing difficulty22. The effects of pore structure, resulting from different degrees of phase separation, and molecular weight on the dissolution rate of polyacrylamide were investigated. The AAm50-DMF40 sample has a dense network structure (Fig. 1f), requiring 3.7 h to fully dissolve in neutral water at room temperature. This is already a highly efficient dissolution compared to previous methods that used hydrolyzable crosslinkers. However, with the introduction of distinct phase separation, the granular AAm50-DMF100 lattice fully dissolves in just 23 min under the same conditions, achieving a 7-fold decrease in dissolution time (Fig. 3a). The introduction of a chain transfer agent effectively reduces molecular weight, further increasing the dissolution rate. For example, with the addition of 0.5% 1-heptanethiol, the molecular weight decreased from 80 kg/mol to 42 kg/mol (Supplementary Fig. 2), and the complete dissolution time of the lattice with the same dimension decreased to just 12 min. A quantitative dissolution experiment using a standard cubic sample also demonstrated that the dissolution rate can be tuned by adjusting the molecular weight (Fig. 3b). However, molecular weight cannot be reduced indefinitely, as this would compromise the strength of the printed sacrificial mold, making it prone to breakage during the casting of other materials. In addition, the effects of sample size and temperature on solubility were systematically investigated. Larger sample sizes exhibited extended dissolution times (Fig. 3c). The dissolution mechanism proceeded through a gradual surface-to-core erosion process rather than bulk collapse. Elevated temperatures significantly accelerated dissolution kinetics, with complete dissolution achieved in only 17 min at 70 °C. This represents approximately a 90% reduction in dissolution time compared to room temperature conditions (Fig. 3d).

Benefiting from its exceptionally mild dissolution conditions, the salt-like granular polyacrylamide mold is suitable for casting a broader range of materials. Although the addition of thiols could enhance dissolution rates to some extent, the original formulation (AAm50-DMF100) was ultimately selected for mold printing in this study due to its relatively better printability (Supplementary Fig. 3). To demonstrate the versatility of the polyacrylamide mold, we first employed a melting-casting strategy using three distinct materials: a low-melting-point alloy (Bi-In-Pb-Sn-Cd), an alkaline-degradable polycaprolactone (PCL) and a polyolefin elastomer (POE). Each material was melted, cast into the mold, and solidified before the polyacrylamide mold was dissolved in water, yielding three-dimensionally structured replicas (Fig. 4a). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) revealed that polyacrylamide begins thermal degradation near 200 °C (Supplementary Fig. 4a), theoretically limiting the processing temperature of castable materials. However, we successfully demonstrated that the mold could withstand short-term exposure to higher temperatures (e.g., 250 °C molten tin) (Supplementary Fig. 4b), suggesting its potential applicability beyond the nominal thermal limit. Additionally, we have successfully replicated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) and polyurethane (PU) (Fig. 4b). Unlike the aforementioned thermoplastic or meltable materials, PDMS and PU require in situ thermal curing reactions after casting. Due to their thermo-curing mechanisms, these materials are generally incompatible with direct DLP 3D printing unless they undergo chemical modification, for example, through the grafting of photopolymerizable groups like acrylates29,30,31. However, such modifications frequently compromise their intrinsic properties and functionalities. In addition to serving as a shell, the polyacrylamide can also be used as a core, enabling the creation of PDMS structures with internal flow channels, which could be applied as microfluidic devices (Fig. 4c).

The microporous structure of the polyacrylamide mold enables fast dissolution but also introduces a potential risk where the cast material may diffuse into the micropores. We evaluated the infiltration of these materials into the PAAm mold. Results demonstrated that except for the high-surface-tension alloy, most materials could infiltrate the micropores to varying degrees (ranging from 140 to 864 μm) during casting (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In general, lower molecular weight (Mw) of the cast material correlated with greater diffusion depth within the microporous structure of the PAAm mold. After dissolving PAAm in water, the surfaces of PCL (Mw = 80,000) and POE exhibited distinct microstructural patterns (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In contrast, PCL (Mw = 2000) retained a smooth surface, likely due to the complete collapse of the microporous layer during PAAm swelling and dissolution. For PDMS, the presence of nitrogen atoms in the PAAm molecular structure may chelated with platinum (the PDMS catalyst), deactivating it and thereby inhibiting polymerization both within the micropores and at the mold surface. Consequently, the surface of the casted PDMS also lacked microstructures. For PU, we hypothesize that the lower crosslinking density led to partial collapse of the surface microstructure during water evaporation.

The phenomenon of material diffusion discussed above suggests a potential alternative application where low-molecular-weight precursors with low viscosity permeate the porous structure of granular polyacrylamide, ultimately forming a bi-continuous interpenetrating network after in situ reaction and curing. Subsequent dissolution of the polyacrylamide in water yields a three-dimensional foam with an inherent microporous architecture (Fig. 5a). For instance, a precursor solution comprising small-molecule epoxy monomers and amine curing agents (viscosity ~30 cP, DMF as diluent) can permeate a 2.0 × 1.0 × 0.5 cm granular polyacrylamide cuboid. After sequential curing at 80 °C for 8 h and then at 120 °C for 2 h, followed by dissolving the polyacrylamide, an epoxy replica with identical geometry is obtained. Both the surface and interior of the epoxy sample exhibit a uniform pore structure that replicates the granular polyacrylamide template (Fig. 5b). This approach leverages our 3D-printed granular polyacrylamide molds to directly fabricate complex-shaped 3D foams, which is unachievable with conventional indirect printing techniques (Fig. 5c). The feasibility of this method relies on precursor diffusion, necessitating the use of low-viscosity small-molecule precursors, sometimes supplemented with solvents to reduce viscosity or vacuum-assisted infiltration. To demonstrate the versatility of this technique, we developed three additional low-viscosity compatible precursors beyond epoxy, including: low-molecular-weight two-component polyurethane, acrylate monomers, and fluorocarbon resin dispersions (Detailed molecular structures and preparation protocols are provided in the Methods). By combining these precursors with granular polyacrylamide molds, we successfully fabricated foams of diverse materials featuring intricate three-dimensional architectures (Fig. 5d).

a Schematic diagram of microporous structures replicated from PAAm sacrificial templates. b Epoxy replicated PAAm porous structure (cuboid thickness: 5 mm) and SEM images of cuboid epoxy foam cross-section. c 3D epoxy foam with different geometry. d Other 3D foam materials and corresponding cross-sectional microstructures. All scale bars are 10 mm unless otherwise noted.

We achieve high-precision DLP printing of non-crosslinked polyacrylamide through polymerization-induced phase separation. This polyacrylamide possesses an intrinsic microporous structure derived from granule packing. Its salt-like ability to dissolve rapidly in neutral water at room temperature makes it ideal for use as a sacrificial mold in indirect printing. The polyacrylamide mold offers broad material compatibility and can also be used to produce microporous foams. One limitation of the polyacrylamide molds lies in its incompatibility with water-soluble materials. For instance, they cannot be used to replicate soft hydrogels, a class of materials for which high-precision direct 3D printing remains particularly challenging. Our preliminary findings reveal that diacetone acrylamide-water precursors can similarly undergo polymerization-induced phase separation to form analogous microstructures (Supplementary Fig. 6). Poly (diacetone acrylamide) can serve as an effective supplement to polyacrylamide, broadening the compatibility range of such water-soluble sacrificial molds. So, we believe that this PIPS enabled polyacrylamide mold and its related technology could enable indirect printing to be practically applied in large-scale manufacturing.

Methods

Materials

Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA, 95%), 1-heptanethiol (98%), benzoyl peroxide (BPO, AR), ethyl acetate (99.5%), polyethylene glycol (PEG400, average molecular weight 400), N,N,N,’N’-tetrakis(2-hydroxypropyl)ethylenediamine (HPED, ≥99%), bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE, ≥85%), N,N’-methylenebisacrylamide (BIS, 99%), acrylamide (AAm, ≥99%), 3-butoxypropylamine (BOPA, 98%), triethanolamine (TEA, ≥99%), polycaprolactone diol (average molecular weight 2000), trimethyl-1,6-hexamethylene diisocyanate (TMHDI, 97%), ethanol ( ≥ 99.7%), diacetone acrylamide ( ≥ 99%) and diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (TPO, 97%) were purchased from Aladdin. N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.8%) was purchased from Meryer. Basic violet 8 was purchased from TCI. 3-aminobenzylamine (NN, 98%) was purchased from Macklin. The two-component silicone rubber (Sylgard 184) was purchased from Dow Corning. Alloy (melting point: 47 °C, composition: Bi 44.7% - In 19.1% - Pb 22.6% - Sn 8.3% - Cd 5.3%) was bought from Dongguan Huatai Metal Material Technology Co., Ltd., China. Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP, ≥98%) was purchased from Leyan. Polycaprolactone (average molecular weight 80,000) was purchased from Dongguan Zhangmutou Haobang Plastic Trading Firm. Polyolefin elastomer (POE, C6, average molecular weight 70,000) was bought from Dongguan Gangtai Energy Technology Co., Ltd., China. Fluorocarbon resin (Fluorinated ethylene vinyl ether copolymer) was bought from Dongguan Siyezi Plastic Co., Ltd., China. XYlink 311 (Methylene diphenylamine) was purchased from Suzhou Xiangyuan New Materials Co., Ltd., China. ADIPRENE® LFP E560A (Isocyanate-terminated prepolymer) was purchased from LANXESS. Tin was bought from Yongkang City Hardware Market NAILIDA Soldering Tin Business Department. All chemicals were used as received.

Resin preparation

AAm, DMF, and H2O with the weight ratio of 50:x:50-x (x = 50, 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, 5, 0; denoted as AAm50-DMFX, X = x/50%) were mixed first. Then 1 wt% photo-initiator (AAm50-DMF0/10/20/30: LAP, other resin: TPO) and 0.04 wt% Basic violet 8 were added (transmittance test was conducted without dye). It is worth noting that the AAm50-DMF0 formulation contains 10 wt% BIS. Thiol was added to tune the molecular weight of polyacrylamide. In this experiment, we specifically added 0.5 wt% and 1 wt% 1-heptanethiol, designated as AAm50-DMF100-0.5%SH and AAm50-DMF100-1%SH, respectively.

DLP printing

The sacrificial molds were printed using a top-down DLP 3D printer (DM200, Zongheng Additive Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd., Zhuhai) with a 405 nm projector. All molds were sliced at a thickness of 100 µm, with an exposure time of 5 s per layer (power density: 14.7 mW/cm²). After printing, the models were soaked in DMF for 1 h, followed by drying at 45 °C for 12 h and at 75 °C for another 12 h to remove the DMF. The drying time can be adjusted appropriately according to the size of the model. Furthermore, the lattice (Fig. 2e) was printed at a speed of 375 mm/h to achieve rapid printing.

The wettability test

Firstly, three types of gels with distinct surface properties were prepared: a non-phase-separated AAm50-DMF0 gel (sample i), a phase-separated AAm50-DMF100 gel cured in the absence of oxygen (sample ii), and a phase-separated AAm50-DMF100 gel cured in open air (sample iii). Specifically, sample i and sample ii were fabricated by injecting the precursor solution between two quartz glass slides (with a 500 µm-thick PDMS spacer to control thickness) and subsequently curing via photo-polymerization. Sample iii was prepared by spreading the precursor solution onto a glass slide equipped with a 500 µm-thick PDMS spacer, with the liquid surface exposed to air, followed by photo-polymerization. These three gels were placed horizontally on a platform to ensure a flat surface. A syringe was then used to drop an identical volume of the corresponding precursor solution onto each gel surface from the same height (1 cm). After the droplets landed on the gel surfaces, images of the droplet states were captured at the same time intervals for analysis.

Characterization of oxygen inhibition polymerization

Depth profile of the molecular weight: A 100 µm thick liquid film of AAm resin was evenly spread on a glass slide using a coater, followed by photopolymerization (light intensity 100%, exposure time 5 s). First, the surface liquid layer was gently collected using a scalpel by tilting the glass plate, allowing the liquid to flow into a glass bottle, which was labeled as Sample 1. Next, the solid layer beneath was carefully sliced into three layers along its thickness using a scalpel. Each layer was collected separately and labeled as Samples 2, 3, and 4, respectively. As each layer was sliced and collected, the remaining thickness was measured by vernier scale to determine the sliced thickness. All samples were then dissolved in water and analyzed using gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Agilent PL-GPC50).

(2) The effect of irradiation time on the depth of inhibition: To measure the inhibition depth under different energy conditions, A 100 µm thick liquid film of AAm resin was evenly spread on a glass slide using a coater. After irradiation, the residual liquid on the surface was wiped with a napkin. The thickness of the solid layer was measured using a vernier scale and recorded as h µm, while the inhibition depth was calculated as (100 h) µm. Each energy condition was tested for at least three times, and the average thickness was used for analysis.

Sacrificial molding

Conventional casting

-

(1)

The alloy and PCL (Mw = 2000) were melted separately at 80 °C, then each was injected into its own dedicated PAAm mold. After cooling and solidifying, the sacrificial molds were dissolved in water. POE particles were packed into the sacrificial mold’s channels and heated at 135 °C for 1 h to melt. Upon cooling and solidification, the mold was washed away with water, yielding a complex POE-based structure. The results were shown in Fig. 4a.

-

(2)

Silicone rubber: The PDMS was thoroughly mixed with the curing agent in the ratio of 10:1 and subsequently a portion of the mixture was injected into a shell sacrificial mold. The degassing process was carried out at 40 °C, followed by a curing process at 80 °C for 3 h. Eventually, the sacrificial mold was dissolved to release the molded PDMS part. Polyurethane: The mixture of XYlink 311 and ADIPRENE® LFP E560A was poured into the channels of the sacrificial mold and cured sequentially at 50 °C for 1 h and 120 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the sacrificial mold was dissolved with water, leaving behind a polyurethane model. The results were shown in Fig. 4b.

-

(3)

The PDMS precursor was first poured into a square mold (The square mold was fabricated from commercial resin printing), degassed at room temperature, and then the core sacrificial mold was immersed. Upon completion of curing at room temperature, the embedded sacrificial mold was removed through dissolution in water (The sacrificial mold requires 37 h of dissolution at room temperature with 500 rpm stirring.), resulting in the fabrication of a microfluidic device. The results were shown in Fig. 4c.

Infusion casting

-

(1)

Epoxy foam: Epoxy monomer BADGE (13.6 g), NN (0.61 g), BOPA (3.93 g) and DMF (2.721 g, 15 wt%) were mixed and infused into the microporous structure of the sacrificial mold under vacuum. Subsequently, it was cured at 80 °C for 8 h and at 120 °C for 2 h. The epoxy foam was obtained by dissolving the sacrificial scaffold in water.

-

(2)

Polyurethane foam: First, TMHDI (14.59 g, 2 mol), TEA (4.02 g, 0.8 mol), HPED (2.47 g, 0.31 mol), and PEG400 (1.33 g, 0.1 mol) were mixed with ethyl acetate (11.21 g, 50 wt% relative to total monomers) and stirred until a transparent solution was obtained. The sacrificial mold was then fully immersed in the solution until complete infiltration. Next, the mold was heated at 50 °C for 4 h. After curing, the mold was further dried at 70 °C for 12 h to completely remove residual solvent. Finally, the polyurethane foam was obtained by dissolving the sacrificial mold in water.

-

(3)

Polyacrylate foam: A mixture of TMPTA (20 g), BPO (0.2 g, 1 wt%), and DMF (3 g, 15 wt%) was prepared and infused into the sacrificial mold’s microporous structure. The mold was heated at 70 °C for 3 h. After curing, it underwent further drying at 70 °C for 12 h to evaporate residual solvent. Finally, the sacrificial scaffold was subsequently dissolved in water, producing a polyacrylate foam.

-

(4)

Fluorocarbon resin foam: The fluorocarbon resin dispersion was thoroughly mixed with the curing agent at a mass ratio of 2:1, followed by the addition of 15 wt% anhydrous ethanol as a diluent to adjust the solution viscosity. After complete homogenization, the mixture was infused into the micropores of a sacrificial mold. The mold was then heated at 70 °C for 3 h. Finally, the sacrificial mold was removed by dissolution in water, yielding a fluorocarbon foam structure.

All foam materials ultimately have their water removed through freeze-drying.

Microstructural characterization

The morphology of the printed samples from different AAm formulations, as well as the morphology of different casting materials, was analyzed using SEM (Verios G4 UC, Thermo scientific, High Voltage: 2 kV, Detector: Through-the-Lens Detector (TLD), Mode: Secondary Electron(SE)).

Transparency test

The dye-free resin was poured between two quartz glass slides with a 500 µm PDMS ring spacer, cured, and then tested for transparency using a photoelectric fog meter (Shanghai INESA Physico optiacal Instrument Co.,Ltd.). Each sample was measured three times, and the average value was recorded.

Dissolution test

We first evaluated the dissolution behavior of 20 mm lattice structures fabricated from three formulations: AAm50-DMF40, AAm50-DMF100 and AAm50-DMF100-0.5%SH. Each lattice was individually immersed in water with magnetic stirring (500 rpm) at room temperature to determine complete dissolution time. Additionally, we conducted quantitative dissolution testing through three experimental groups: (1) For thiol content effect, we compared 10 mm cubes of AAm50-DMF100, AAm50-DMF100-0.5%SH, and AAm50-DMF100-1%SH under room temperature stirring conditions; (2) For size effect, we tested 5 mm, 10 mm and 15 mm AAm50-DMF100 cubes under identical dissolution conditions; (3) For temperature effect, we dissolved 10 mm AAm50-DMF100 cubes at room temperature, 50 °C and 70 °C with stirring.

Molecular weight analysis of polymers with different thiol content

A 100 µm thick liquid film of AAm resin with different thiol content, without dye (AAm50-DMF100, AAm50-DMF100-0.5%SH, AAm50-DMF100-1%SH) was individually spread on a glass slide using a coater, followed by photopolymerization (light intensity 100%, exposure time 5 s). Subsequently, the film was peeled off with a blade, dried at 70 °C for 12 h to remove residual solvent. The sample was then dissolved in water, and the molecular weight was measured using GPC (Agilent PL-GPC50). Each formulation was measured three times, and the average value was recorded.

Mechanical properties test

Tensile tests were conducted using a computer-controlled universal testing machine (Shenzhen Sansi Zongheng Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature (25 °C), with a speed of 20 mm/min for AAm50-DMF100/80 (this sample was much brittle, so we use a lower tensile speed) and 100 mm/min for AAm50-DMF60/40. The dog-bone samples with 40.0 × 10.0 × 1.5 mm dimensions were printed for each test. The tensile modulus was determined by calculating the slope of the stress-strain curve within the 1–2% strain range.

Porosity and pore size test

Cubes measuring 10.0 × 10.0 × 2.0 mm printed with different formulations were separately loaded into an automatic mercury porosimeter (the max pressure: 414 MPa, AutoPore IV 9510, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, USA.) to test porosity and pore size.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the article and its Supplementary Information file. The data are available from the corresponding authors on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, B., Zhang, Z., Pei, Z., Qiu, J. & Wang, S. Current progress on the 3D printing of thermosets. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 3, 462–472 (2020).

Ligon, S. C., Liska, R., Stampfl, J., Gurr, M. & Mülhaupt, R. Polymers for 3D printing and customized additive manufacturing. Chem. Rev. 117, 10212–10290 (2017).

Cano-Vicent, A. et al. Fused deposition modelling: current status, methodology, applications and future prospects. Addit. Manuf. 47, 102378 (2021).

Zub, K., Hoeppener, S. & Schubert, U. S. Inkjet printing and 3D printing strategies for biosensing, analytical, and diagnostic applications. Adv. Mater. 34, 2105015 (2022).

Han, W., Kong, L. & Xu, M. Advances in selective laser sintering of polymers. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 4, 042002 (2022).

Cheng, J., Yu, S., Wang, R. & Ge, Q. Digital light processing based multimaterial 3D printing: challenges, solutions and perspectives. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 6, 042006 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Advances in precision microfabrication through digital light processing: system development, material and applications. Virt. Phys. Prototyp. 18, e2248101 (2023).

Patel, D. K. et al. Highly stretchable and UV curable elastomers for digital light processing based 3D printing. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606000 (2017).

An, X. et al. Stereolithography 3D printing of ceramic cores for hollow aeroengine turbine blades. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 127, 177–182 (2022).

Saadi, M. A. S. R. et al. Direct ink writing: a 3D printing technology for diverse materials. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108855 (2022).

Layani, M., Wang, X. & Magdassi, S. Novel materials for 3D printing by photopolymerization. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706344 (2018).

Lai, H., Peng, X., Li, L., Zhu, D. & Xiao, P. Novel monomers for photopolymer networks. Prog. Polym. Sci. 128, 101529 (2022).

Chen, Q. et al. 3D printed multifunctional, hyperelastic silicone rubber foam. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900469 (2019).

Jia, Y. et al. Highly efficient self-healable and robust fluorinated polyurethane elastomer for wearable electronics. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 133081 (2022).

Duan, H., Chen, Y., Ji, S., Hu, R. & Ma, H. A novel phosphorus/nitrogen-containing polycarboxylic acid endowing epoxy resin with excellent flame retardance and mechanical properties. Chem. Eng. J. 375, 121916 (2019).

Xu, X. et al. Sophisticated structural ceramics shaped from 3D printed hydrogel preceramic skeleton. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404469 (2024).

Miao, J. et al. 3D printing of sacrificial thermosetting mold for building near-infrared irradiation induced self-healable 3D smart structures. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 131580 (2022).

Zhao, B. et al. Photo-curing 3D printing of thermosetting sacrificial tooling for fabricating fiber-reinforced hollow composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213663 (2023).

Peng, S. et al. Tailored and highly stretchable sensor prepared by crosslinking an enhanced 3D printed UV-curable sacrificial mold. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008729 (2021).

Zhu, G. et al. Digital light 3D printing of double thermoplastics with customizable mechanical properties and versatile reprocessability. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401561 (2024).

Deng, S., Wu, J., Dickey, M. D., Zhao, Q. & Xie, T. Rapid open-air digital light 3D printing of thermoplastic polymer. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903970 (2019).

Kleger, N. et al. Light-based printing of leachable salt molds for facile shaping of complex structures. Adv. Mater. 34, 2203878 (2022).

Lee, K., Corrigan, N. & Boyer, C. Polymerization induced microphase separation for the fabrication of nanostructured materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307329 (2023).

Zhu, L., Su, Y., Liu, Z. & Fang, Y. Shape-controlled synthesis of covalent organic frameworks enabled by polymerization-induced phase separation. Small 19, 2205501 (2023).

Wang, Z., Heck, M., Yang, W., Wilhelm, M. & Levkin, P. A. Tough PEGgels by in situ phase separation for 4D printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2300947 (2024).

Dong, Z. et al. 3D printing of inherently nanoporous polymers via polymerization-induced phase separation. Nat. Commun. 12, 247 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Enhancing temperature responsiveness of PNIPAM through 3D-printed hierarchical porosity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2403794 (2024).

Song, C., Zhao, Q., Xie, T. & Wu, J. DLP 3D printing of electrically conductive hybrid hydrogels via polymerization-induced phase separation and subsequent in situ assembly of polypyrrole. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 5348–5356 (2024).

Zhao, T. et al. Superstretchable and processable silicone elastomers by digital light processing 3D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 14391–14398 (2019).

Bhattacharjee, N., Parra-Cabrera, C., Kim, Y. T., Kuo, A. P. & Folch, A. Desktop-stereolithography 3D-printing of a poly(dimethylsiloxane)-based material with sylgard-184 properties. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800001 (2018).

Ding, G. et al. Meniscal transplantation and regeneration using functionalized polyurethane bionic scaffold and digital light processing 3D printing. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133861 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following programs for the financial support: the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB3805701 to J.W.), National Natural Science Foundation (No. 22422505 and 22375176 to J.W.). Research and Development Project for “Top Soldiers” and “Leading Geese” of Zhejiang Provincial Science Technology (2024C03082 to Q.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and Z.S. designed and conducted the experiments. J.W. wrote the paper. Q.Z., T.X., and J.W. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kunal Masania, who co-reviewed with Christopher Lankhof; Nikolaj Mandsberg; and Lixin Wu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Si, Y., Sun, Z., Zhao, Q. et al. 3D printing of salt-like granular polyacrylamide as sacrificial molds for shaping versatile materials. Nat Commun 16, 7177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62674-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62674-1