Abstract

YnaI is a member of the family of bacterial MscS (mechanosensitive channel of small conductance)-like channels. Channel gating upon hypoosmotic stress and the role of lipids in this process have been extensively studied for MscS, but are less well understood for YnaI, which features two additional transmembrane helices. Here, we combined cryogenic electron microscopy, molecular dynamics simulations and patch-clamp electrophysiology to advance our understanding of YnaI. The two additional helices move the lipid-filled hydrophobic pockets in YnaI further away from the lipid bilayer and change the function of the pocket lipids from being a critical gating element in MscS to being more of a structural element in YnaI. Unlike MscS, YnaI shows pronounced gating hysteresis and remains open to a substantially lower membrane tension than is needed to initially open the channel. Thus, at near-lytic membrane tension, both MscL and YnaI will open, but while MscL has a large pore and must close quickly to minimize loss of essential metabolites, YnaI only conducts ions and can thus remain open for longer to continue to facilitate pressure equilibration across the membrane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mechanosensitive channels translate mechanical forces into ion fluxes across cell membranes and play pivotal roles in a variety of biological processes, including touch, hearing and blood pressure regulation1,2. Mechanosensitive channels evolved in bacteria, where they are essential for protection from lysis upon hypoosmotic shocks3,4,5. Virtually all bacteria express a mechanosensitive channel of large conductance (MscL), which provides most of the protection against hypoosmotic shock, but most bacteria also express a mechanosensitive channel of small conductance (MscS) and often also additional members of the MscS-like channel family6.

MscS has been extensively studied and the first structure, determined by X-ray crystallography7, revealed a heptamer with a large cytoplasmic domain and each subunit contributing three transmembrane (TM) helices. TM3 forms the ion-conducting pore whereas TM1 and TM2 form a paddle that senses membrane tension. A later study of MscS carrying the A106V mutation allowed determination of the first structure of MscS in the open state8. A subsequent crystal structure of MscS identified the presence of alkyl chains in extramembranous pockets. This discovery, together with additional experiments, including mass spectrometry and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations that showed less lipids in the pockets in the open state than in the closed state, prompted the proposal of the ‘lipids-move-first’ mechanism9. In this molecular implementation of the fundamental ‘force-from-lipids’ principle10,11,12, membrane tension initiates the extraction of lipids from the pockets, which destabilizes the closed conformation and initiates MscS gating. This mechanistic model gained further experimental support from recent single-particle cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of MscS in lipid nanodiscs that revealed lipids associated with different regions of the channel: pore lipids inside the ion-conducting channel seal the pore in the closed state, pocket lipids in the extramembranous pockets that have to be extracted for the channel to transition to the open conformation, and hook/gatekeeper lipids in between the tension-sensing TM1-2 paddles13,14,15. One of these studies also used β-cyclodextrin (βCD)-mediated lipid removal from the nanodiscs to mimic membrane tension, which allowed visualization of MscS in the inactivated state15.

E. coli expresses the archetypal MscS and five additional MscS-like channels that all share a structurally similar core with MscS ( ~ 20–25% sequence similarity) but feature additional structural elements. YnaI and YbdG have two additional transmembrane helices, whereas YbiO, MscK, and YjeP have eight additional helices as well as large periplasmic extensions6. Of these channels, MscK, which differs from the other E. coli MscS-like channels in that its activation requires external potassium ions, is the only one for which the structure is known for both the closed and open states16. The cryo-EM structures did not reveal associated lipids, potentially a limitation of the used image-processing strategy, but the TM domain of MscK in the closed state is substantially curved and flattens in the open state. Hence, MscK was proposed to be activated not through the lipids-move-first mechanism but in a similar manner as eukaryotic Piezo channels17,18, namely through tension-mediated flattening of the transmembrane domain16. A similar mechanism has now also been proposed for MscS19.

The remaining MscS-like channels of E. coli are less well understood, but several structures have been determined for YnaI20,21,22,23,24. YnaI is similar to MscL in that it opens at a tension that is close to membrane rupture, but unlike MscL, once open, YnaI only generates a conductance of ~0.1 nS25. Still, when overexpressed, YnaI can protect E. coli from hypoosmotic shock25.

A first cryo-EM map of YnaI at 13 Å resolution confirmed its structural similarity to MscS, showing a comparable cytoplasmic vestibule and a slightly larger transmembrane domain consistent with its two additional transmembrane helices20. A subsequent study produced the first high-resolution structure at 3.8 Å resolution of YnaI in amphipols. While the map only resolved the pore-forming helix, TM3, and one helix of the sensor paddle, TM2, the study established that YnaI forms a Na+/K+-selective channel and that Met158 is critical for its ion selectivity24. The most intriguing structures were obtained when YnaI was extracted from the membrane with the copolymer diisobutylene/maleic acid (DIBMA). By using DIBMA to extract YnaI directly from E. coli membranes into native nanodiscs, cryo-EM analysis yielded a 3.0 Å resolution density map that resolved all five TM helices, visualizing for the first time the arrangement of the additional helices, TM-N1 and TM-N2, relative to the three core helices, TM1-322. This study also provided the first glimpse of YnaI in the open state. For this purpose, YnaI was purified and reconstituted into liposomes. The liposomes were then exposed to lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), which had previously been used to activate MscS (e.g.26), and YnaI was extracted with DIBMA. Cryo-EM analysis of the resulting YnaI-containing DIBMA nanodiscs yielded three intermediate-resolution density maps that showed the channel in a closed-like, intermediate and open-like conformation22. Even though the TM helices were not well resolved, the open-like conformation features a much flatter transmembrane domain than seen in the closed-like state, which suggested that this flattening may result in channel gating as in the case of MscK16.

The first cryo-EM map of YnaI did not have the resolution to visualize associated lipids, but an accompanying tryptophan quenching study already suggested that YnaI has lipid-accessible cavities similar to those in MscS20. A lipid associated with YnaI, in a position similar to that of the pocket lipids in MscS, was then indeed seen in the higher-resolution cryo-EM structure of YnaI in DIBMA22, as well as in two subsequent cryo-EM structures, one obtained with YnaI in the detergent lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol (LMNG)23 and one obtained with the copolymer SMA2000 that only resolved the two central helices, TM2 and TM321. Analysis by thin-layer chromatography established that, compared to the composition of the E. coli membrane, lipids co-purifying with YnaI may be enriched in cardiolipin and phosphatidyl serine23. Importantly, mutations of residues interacting with the associated lipid showed effects on channel activation and on cell survival upon hypoosmotic shock22,23. These results indicated that lipids associated with YnaI are important for mechanosensation and may play a similar role as the pocket lipids in MscS, suggesting that YnaI may potentially also be gated by the lipids-move-first mechanism, although the structure of the open-like conformation indicated a gating motion quite distinct from that seen in MscS22.

In this work, we determine cryo-EM structures of nanodisc-embedded YnaI in the closed conformation that all revealed well-resolved pocket lipids, but despite pursuing several approaches, we were unable to obtain a structure of YnaI in the open conformation. However, our structures and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a molecular explanation for why YnaI requires near membrane-lytic tensions to activate. In addition, a detailed electrophysiological characterization of YnaI reveals substantial gating hysteresis and points towards a potential physiological role for this channel.

Results

The structure of YnaI in the closed resting state reveals many pocket lipids

After optimizing the purification of YnaI in dodecyl maltoside (DDM), we reconstituted the recombinant protein with the lipid dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine (DOPC) and the membrane scaffold protein (MSP) MSP2N2, which forms nanodiscs with an average diameter of 15–16.5 nm27.

Analysis of the resulting YnaI nanodiscs by single-particle cryo-EM yielded a density map at 2.5 Å resolution (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2), which allowed us to build an atomic model for most of the channel (Fig. 1a). Density for peripheral helix TM-N2 was poorly resolved and only allowed building the helical backbone. Our model of YnaI is consistent with previous structures obtained by single-particle cryo-EM21,22,23,24 with minimal root-mean-square deviations between corresponding Cα atoms (e.g., 1.10 Å for 6URT). The cytoplasmic vestibule domain is most similar between YnaI structures, whereas the two additional transmembrane helices, TM-N1 and TM-N2, show the largest variations, suggesting that these helices are more dynamic.

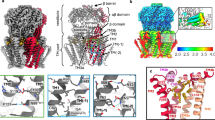

a Cryo-EM map (transparent white surface) and model of YnaI (white ribbons) with individual domains of one YnaI subunit colored and labeled. Membrane indicated by transparent yellow box. b Analysis of the pore radius of YnaI in the closed conformation using HOLE28. Left panel: Cut-away view of the YnaI structure (cyan ribbons) and the ion-conducting pathway (blue surface). Side chains of residues Leu154 and Met158, which form the pore constriction, are shown as light orange sticks. Right panel: Plot of the pore radius of YnaI along the z axis (black line). Pore radius plots are also shown for the structures of YnaI in LMNG (PDB: 6URT, blue line)23 and in native DIBMA nanodisc (PDB: 6ZYD, red line)22. c Alignment of the structures of YnaI (cyan ribbons) and MscS (PDB: 6VYK; white ribbons) in the closed conformation. Left panel: Overall view of two aligned subunits. YnaI helices TM-N1 and TM-N2 are not shown for clarity. The gatekeeper lipid sandwiched between the two MscS subunits is shown as black sticks, and the MscS residues stabilizing its headgroup are shown as magenta sticks. Right panels: Zoomed-in views of the boxed region in the left panel for MscS (top) and YnaI (bottom). YnaI does not have the structural features that would stabilize a gatekeeper lipid (indicated as transparent black sticks). d The cryo-EM map of YnaI shows clear density for the pocket lipids. Shown are sections perpendicular (top) and parallel to the membrane (bottom) through the YnaI model (cyan ribbons) and the density in the pockets not accounted for by the YnaI model (transparent salmon surface) and the modeled lipid molecules (red sticks). Top two panels on the right show zoomed-in views of the density and models of the pocket lipids, while bottom panel shows a section through the lipid density and models at the position indicated by the dashed line in the panel above. Ten distinct elongated densities could be modeled as acyl chains with 10 to 18 carbon atoms. Numbers indicate modeled lipids.

Analysis of the YnaI structure with the program HOLE28 showed that the narrowest region of the pore, at residue Met158, has a diameter of ~6.6 Å (Fig. 1b), which is consistent with previously determined structures of YnaI in the closed conformation21,22,23,24. Like all maps determined to date, our map also does not show density for pore lipids or gatekeeper lipids, which are seen in maps of MscS in nanodiscs13,14,15. The lack of pore lipids is likely related to the more hydrophilic nature of the YnaI pore compared to the MscS pore22. Furthermore, TM2 and TM3 in YnaI are shorter than in MscS, the distance between TM1 and TM2 is larger in YnaI than in MscS, and the residues that stabilize the headgroup of the gatekeeper lipid in MscS are not conserved in YnaI (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 2e). Also, like in previous cryo-EM maps of YnaI, our map shows density for lipids in the hydrophobic pockets, lipids that are proposed to play a critical role in the mechanosensation of MscS9,15. Our map shows ten well-defined tubular densities (Fig. 1d). The headgroup densities were not sufficiently well resolved to identify the lipid species, and all lipids were therefore modeled as phosphatidylethanolamine, the predominant lipid species in E. coli membranes29. The acyl chains were modeled according to the length of the tubular densities and contained 10 to 18 carbon atoms.

Nanodiscs do not allow structure determination of YnaI in the open conformation

We have recently introduced lipid removal with β-cyclodextrin (βCD) as an approach to mimic membrane tension and to open mechanosensitive channels30,31. We therefore incubated YnaI-containing nanodiscs with βCD and analyzed the effect on YnaI by cryo-EM. The sample yielded a density map at 2.3 Å resolution (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 3, 4), and the model revealed that the channel remained in the closed conformation. The RMSD between the structures of nanodisc-embedded YnaI with or without βCD treatments was 0.57 Å.

a The overlay of the structure of YnaI in DOPC nanodiscs before (one subunit shown as cyan ribbons) and after treatment with βCD (one subunit shown as cornflower blue ribbons and the other six subunits as white ribbons) shows that nanodisc-embedded YnaI remains in the closed conformation upon treatment with βCD. b Representative patch-clamp electrophysiology recordings (from sets of 5 recordings each) of soy polar liposomes reconstituted without (top panel) and with YnaI (bottom panel) that were treated with 10 mM βCD. The pipette potential was +30 mV. The increase in current shortly before rupture of the YnaI-containing liposomes shows that βCD-mediated lipid removal can activate YnaI in liposomes. c Quantification of peak currents from 5 recordings each that were induced by βCD treatment of soy polar liposomes without (Empty) and with YnaI. The box-and-whisker plot shows the median current (line), the upper and lower quartiles (box), and the upper and lower extremes (whiskers).

We used electrophysiology to assess whether the failure to use βCD to generate a cryo-EM structure of nanodisc-embedded YnaI in the open state was a feature of the channel or a shortcoming of the use of nanodiscs. We reconstituted YnaI with soy polar lipid into proteoliposomes and performed patch-clamp electrophysiology. When 10 mM βCD was applied to increase membrane tension, we consistently observed increasing YnaI activation with peak currents of approximately 15–50 pA until the patches ruptured, while empty control liposomes did not show any currents (Fig. 2b, c). These results confirmed that YnaI can be activated by increased membrane tension induced by βCD application.

In another approach to determine the structure of YnaI in an open conformation, we used lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), which was used to activate YnaI in a previous study22. We incubated YnaI in DOPC spNW25 nanodiscs with 5 μM LPC and then determined the structure by cryo-EM. The resulting map at 3.0 Å resolution allowed us to build a model, which again showed the channel in a closed conformation (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Figs. 5, 6).

a The overlay of the structure of YnaI in DOPC nanodiscs before (one subunit shown as cyan ribbons) and after treatment with LPC (one subunit shown as slate blue ribbons and the other six subunits as white ribbons) shows that nanodisc-embedded YnaI remains in the closed conformation upon treatment with LPC. b 2D-class averages showing side views of MscS (left panels) and YnaI (right panels) reconstituted in DOPC nanodiscs before (top panels) and after treatment with LPC (bottom panels). LPC treatment induces a conformational change in MscS, as seen by the distinct appearances of the transmembrane domain in the MscS averages before and after LPC treatment (indicated by square brackets), whereas LPC treatment has no effect on the appearance of the transmembrane domain in the YnaI averages. c Representative patch-clamp electrophysiology recordings (from sets of 5-6 recordings each) of soy polar liposomes reconstituted with MscS (top panel) and with YnaI (bottom panel) that were treated with 25 μΜ LPC. The pipette potential was +30 mV. The increase in current before rupture of the MscS-containing liposomes shows that LPC can activate MscS in liposomes, but this is not observed for YnaI-containing liposomes. d Quantification of peak currents from 5-6 recordings each that were induced by LPC treatment of soy polar liposomes without protein (Empty), with MscS, and with YnaI. The box-and-whisker plot shows the median current (line), the upper and lower quartiles (box), and the upper and lower extremes (whiskers).

To understand whether the failure to activate nanodisc-embedded YnaI with LPC was a feature of the channel itself or was related to our use of nanodiscs, we tested the same approach with nanodisc-embedded MscS. In contrast to 2D averages of nanodisc-embedded YnaI that looked essentially the same whether the nanodiscs were incubated with LPC or not, 2D averages of MscS showed a clear change in the appearance of the transmembrane region after incubation with LPC (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 7).

We also used electrophysiology to determine whether YnaI can be activated by LPC. We reconstituted YnaI, and as control also MscS, with soy polar lipid into proteoliposomes and performed patch-clamp measurements. As shown previously, incubation with 25 μM LPC resulted in robust activation of MscS with peak currents of 500–1700 pA. In contrast, addition of 25 μM LPC elicited no currents for YnaI and empty liposomes (Fig. 3c, d). These results show that, unlike MscS, YnaI cannot be activated by LPC.

The first structure of MscS in the open state was determined by X-ray crystallography with detergent-solubilized MscS carrying the A106V mutation that stabilizes MscS in an open conformation8. We thus introduced the analogous mutation, A155V, in YnaI and determined its cryo-EM structure in DDM. Data processing yielded two maps of YnaI in slightly different conformations, both at 2.8 Å resolution, which allowed us to build atomic models (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 8, 9). In model A155V-1, the configuration of transmembrane helices TM-N1, TM1, TM2 and TM3 is essentially identical to that in the closed conformation of YnaI. In model A155V-2, only the mutation-carrying and pore-forming TM3 is in the same position as in the closed conformation, whereas TM1, TM2 and TM-N1 appear to be rotated about TM3b. TM-N2 was not resolved in either map. Thus, even though the A155V mutation induced some conformational change in a subpopulation of the channels, the pore remains in the closed conformation. However, the observed rotation may represent the beginning of YnaI channel opening.

a Cryo-EM analysis of A155V mutant YnaI in DDM revealed two different conformations, which are overlaid and shown parallel to the membrane (complete channels) and perpendicular to the membrane (section). One conformation shows the canonical closed conformation (one subunit shown as green-yellow ribbons and the other six subunits as white ribbons), whereas the other conformation shows a rotation of the peripheral helices (one subunit shown as sea green ribbons), but the channel remains closed. Residue Ala155 that was mutated to Val is represented as red spheres. b The pressure sensitivity of wild-type (WT) YnaI (n = 5), WT MscS (n = 6) and YnaI mutants A155V (n = 4), K108L (n = 6), R120A (n = 4) and F40A (n = 3) relative to WT MscL measured in giant spheroplasts prepared from E. coli strain MJF431 (which does not express MscS, MscK and MscM) shows that the pressure sensitivity of YnaI is similar to that of MscL. Mutations R120A and F40A had no effect on the pressure sensitivity of YnaI, whereas mutation K108L and potentially A155V made the channel slightly more sensitive to pressure. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance assessed using unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. c Interactions of pocket lipids (salmon sticks) with YnaI (cyan ribbons) in DOPC nanodiscs. The YnaI residues interacting with the pocket lipids that were mutated are shown as light-green spheres. The inset shows a magnified view of a single hydrophobic pocket. The side chains of the YnaI residues interacting with the pocket lipids that were mutated are shown as light-green sticks.

We then expressed wild-type YnaI, wild-type MscS, and A155V mutant YnaI in E. coli strain MJF431, which also expresses MscL, and prepared giant spheroplasts for patch-clamp electrophysiology. Application of a constant pressure ramp showed that the activation threshold of the A155V mutant remained close to that of endogenous wild-type MscL but was slightly reduced (Fig. 4b). Statistical analysis revealed that this reduction was above statistical significance. This result indicates that this mutation in YnaI may have a small effect but it is much smaller than that of the analogous A106V mutation in MscS, which mirrors the degree of structural effects these mutations have in MscS and YnaI.

Previous studies of YnaI identified multiple mutations that increase its open probability based either on decreased pressure required to open YnaI in electrophysiology experiments, such as K108L22, or on increased survival after hypoosmotic shock when the mutant is overexpressed, as is the case for R120A23. Our structures also show that residue Phe40 interacts with pocket lipids (Fig. 4c) and so we hypothesized that mutating this residue to alanine could make it easier for the lipids to dissociate and thus facilitate channel opening. However, our patch-clamp experiments with YnaI mutants K108L, R120A, and F40A only showed a statistically significant reduction in the activation threshold for the K108L mutation, whereas the other two mutations did not show a statistically significant change in activation threshold (Fig. 4b).

The pocket lipids in YnaI do not freely exchange with the membrane

Reconstitution of MscS into nanodiscs with 1,2-didecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DDPC), which will form a very thin membrane, serendipitously stabilized the channel in a sub-conducting state15. To test whether this is also the case for YnaI or whether hydrophobic mismatch activates YnaI, we determined the cryo-EM structure of YnaI reconstituted with DDPC into MSP2N2 nanodiscs at 2.3 Å resolution, which once again showed YnaI in the closed conformation (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). In particular, we noticed that the density representing the pocket lipids is almost indistinguishable from that seen in the map generated with YnaI in DOPC nanodiscs (Fig. 5b), suggesting that the pocket lipids were the native E. coli lipids that co-purified with YnaI and were not removed by the detergent during purification or replaced in the nanodisc with the much shorter DDPC lipids. This observation, and the fact that pocket lipids are much better defined in YnaI maps than in MscS maps, suggests that the pocket lipids in YnaI are quite static, different from the dynamic pocket lipids in MscS (Fig. 5c).

a Overlay of YnaI in DDPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs (one subunit in blue) and YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs (one subunit in cyan). b Comparison of the pocket lipid density (transparent surfaces) and models (sticks) for YnaI in DOPC nanodiscs (left) and in DDPC nanodiscs (right). Views parallel (top) and perpendicular to membrane (bottom) show that the pocket-lipid density is virtually identical. c Comparison of the pocket-lipid density from a single pocket of YnaI in DOPC nanodiscs (left) and of MscS in DOPC nanodiscs (right). Views parallel (top) and perpendicular to membrane (left bottom) show that the pocket-lipid density in YnaI reveals well-defined acyl chains, and less so in MscS. d Lipid occupancy of the hydrophobic pockets in MscS (gray line) and YnaI (cyan line) over time in MD simulations. Lines depict average occupancy. e Distance of pocket lipids in YnaI and MscS from membrane. Left: Representative snapshots from MD simulations show that pocket lipids (red sticks) in YnaI (one subunit in cyan) are further away from membrane (faint yellow box) than pocket lipids (red sticks) in MscS (one subunit shown in solid white). Right panel: Distance of pocket lipids from membrane in YnaI and MscS simulations. Distance measured from center of mass (COM) of pocket lipids to COM of cytoplasmic-leaflet lipids over last 500 ns of production phase of MD simulations. Box-and-whisker plot shows median distance (line), mean (x symbol), upper and lower quartiles (box), and upper and lower extremes (whiskers). Statistical significance assessed using unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test (n = 1500). f Distance of cytoplasmic domain of YnaI and MscS from membrane. Distance measured from COM of cytoplasmic domain to COM of cytoplasmic-leaflet lipids during last 500 ns of production phase of MD simulations. Solid lines depict average distance for YnaI (cyan) and MscS (gray), and shaded regions depict standard deviation. g Representative snapshots show that more protein residues interact with pocket lipids (red sticks) in YnaI (left) than in MscS (right). Residues interacting with pocket lipids shown as light-green sticks.

Following up on this observation, we performed all-atom MD simulations to further assess the properties of the pocket lipids. We placed YnaI, and for comparison also MscS, into a bilayer approximating the lipid composition of a native E. coli membrane and ran three replica simulations. We performed extended equilibration simulations constraining the protein backbone (because the pockets collapse in the absence of lipids; not shown) and followed how long it took for lipids to fill the initially empty pockets. We found that compared to MscS, it took almost two times longer for the pockets of YnaI to fill with lipids during equilibration ( ~ 300 ns for MscS versus ~ 500 ns for YnaI) (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Movies 1, 2). The half times t1/2 by which the pockets were half filled were 32.3 ± 12.0 ns for MscS and 127.0 ± 21.4 ns for YnaI. Once fully occupied, the MscS pockets accommodated on average 24.7 ± 1.0 total lipids and 3.5 ± 0.6 lipids per pocket, whereas the YnaI pockets accommodated on average 30.5 ± 2.7 total lipids and 4.3 ± 0.9 lipids per pocket (Supplementary Fig. 12a). While mostly phospholipids entered the pockets, with no strong preference for any specific phospholipid species, cardiolipin also entered the pockets, in agreement with previous work23 (Supplementary Fig. 12b).

Closer inspection of the pocket lipids revealed that those in YnaI are located on average ~20.5 ± 1.3 Å from the average position of the center of mass of the lipids in the cytoplasmic leaflet, ~3 Å further away than the pocket lipids in MscS ( ~ 17.6 ± 2.5 Å) (Fig. 5e). The reason for the increased distance of the pocket lipids from the membrane is the presence of the two additional transmembrane helices in YnaI, TM-N1 and TM-N2. While these two helices are fully embedded in the membrane, they push the MscS-like core of YnaI further out of the membrane compared to MscS, so that the cytoplasmic domain of YnaI ends up ~4.2 Å further away from the cytoplasmic leaflet compared to MscS ( ~ 64.4 Å for MscS versus ~ 68.6 Å for YnaI) (Fig. 5f). As a result, the hydrophobic pockets are further away from the membrane (Supplementary Movie 3), providing a molecular explanation for why it takes longer for lipids to fill the pockets in YnaI.

Analysis of the electrostatic interactions between YnaI and lipids revealed that several charged residues, Arg37, Lys108, Arg110, Arg116, Arg120, Lys123, Asp176, and Arg202, make strong interactions with the pocket lipid headgroups (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 13a), perhaps explaining why mutating individual residues had minimal effect on YnaI activation. In comparison, only six residues in MscS make strong electrostatic interactions with the pocket lipids, Arg46, Arg54, Arg59, Asp67, Arg74 and Tyr75 (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 13c). Additionally, more residues in YnaI make hydrophobic interactions with the pocket lipids than in MscS (Supplementary Fig. 13b, d). Thus, YnaI has a higher number of interactions and greater total interaction energies with its pocket lipids than MscS (Supplementary Fig. 13e, f), which is consistent with the better-defined pocket lipid density in our cryo-EM maps of YnaI. Analysis of hydrophobic interactions formed by YnaI with the pocket lipids also revealed that residues Phe40 and Leu41 positioned at the cytoplasmic portion of TM-N1 interact with the pocket lipids, aiding in anchoring TM-N1 and TM-N2 to the core of YnaI (Supplementary Fig. 13b). This observation suggests that the pocket lipids in YnaI may play a more structural role, namely by stabilizing the arrangement of the transmembrane helices, rather than the functional role they play in MscS.

Removal of the additional N-terminal transmembrane helices does not convert YnaI into MscS

The diffusion of the pocket lipids out of the pockets plays an important role in the membrane tension-induced conformational changes in MscS9,15,32. We hypothesized that removing transmembrane helices TM-N1 and TM-N2 would potentially mobilize the pocket lipids in YnaI and thus increase the mechanosensitivity of the truncated channel. However, previous attempts to express and purify YnaI lacking the two N-terminal helices were unsuccessful23. Comparison of the YnaI and MscS structures revealed that the YnaI TM1 helix is slightly shorter than the TM1 helix in MscS (Fig. 6a), which could prevent the stable insertion of YnaI helix TM1 into the membrane in the absence of YnaI helices TM-N1 and TM-N2. We therefore replaced the N-terminal helices of YnaI as well as the loop connecting TM-N1 to TM1 with residues 1–31 of MscS, which corresponds to the N-terminal tail of MscS (containing a short amphipathic helix) as well as the first 9 residues of TM1 (Fig. 6a).

a Design of the MscS/YnaI chimera. Residues 78–343 in YnaI (left) were combined with residues 1–31 from MscS (right) to lengthen TM1 of YnaI and create a chimeric protein (middle) that can stably insert into a membrane (represented by the faint yellow box). b In-silico model of the MscS/YnaI chimera (left panel) and cryo-EM density (transparent white surface) and model (crimson ribbons) of the MscS/YnaI chimera in DOPC nanodiscs (right panel). Only the cytoplasmic domain and the pore-forming helix TM3a were resolved. The chimeric channel adopted the closed conformation and the TM3a helices are positioned inside the membrane. c Representative patch-clamp electrophysiology recording (from a set of 3 recordings) from a giant spheroplast prepared from E. coli strain MJF431 (which does not express MscS, MscK and MscM) overexpressing the MscS/YnaI chimera in response to a pressure ramp (red line) from 0 mmHg to −120 mmHg and back to 0 mmHg. The pipette potential was +60 mV. The black circle denotes the first MscL opening. While several MscL are activated, no current consistent with YnaI opening is observed.

We purified this MscS/YnaI chimera, reconstituted it with DOPC into MSP1E3D1 nanodiscs, and determined the cryo-EM structure at 2.5 Å resolution (Fig. 6b, right panel and Supplementary Figs. 14, 15). While the resulting density map did not resolve the TM1-2 paddle, it showed clear density for the cytoplasmic domain and the TM3a pore helices, which adopted the position seen in the closed conformation. The cryo-EM structure of the chimera (Fig. 6b, right panel) shows that it sits in the membrane in a different way than predicted from the in silico-generated model33 (Fig. 6b, left panel). In the experimental structure, the TM3a pore helices are embedded in the membrane rather than located mostly outside the membrane as is the case in MscS, YnaI and the predicted MscS/YnaI chimera. Even though this arrangement shifts the pockets of the chimera into the membrane (Supplementary Fig. 15e) and even though TM1-2 is disordered, the map shows some density at the position of the pocket lipids, suggesting that the cytoplasmic domain and pore helices suffice to localize some lipids to the pockets (Supplementary Fig. 15f).

To address the question whether the MscS/YnaI chimera is still gated by membrane tension or not, we expressed it in E. coli strain MJF431, which lacks MscS, MscK, and MscM, prepared giant spheroplasts, and performed patch-clamp electrophysiology. Ramp pressure was applied to patch membranes, but in five independent experiments only endogenous MscL currents were detected (Fig. 6e). Therefore, the chimeric channel is insensitive to membrane tension.

The channel characteristics of YnaI differ greatly from those of MscS

Since we were not able to determine the structure of YnaI in an open conformation, we focused on using patch-clamp electrophysiology to better characterize the function of YnaI. We first expressed YnaI in E. coli strain MJF431 (∆MscS, ∆MscK, ∆MscM), which expresses MscL that we used as reference to calibrate the activation threshold of YnaI. We prepared and patched giant spheroplasts and applied increasing hydrostatic negative pressure at a constant rate of −75 mmHg/s. As reported previously25, we observed large MscL and very small YnaI currents at almost the same pressure. YnaI channels opened at a pressure of 146.7 ± 7.7 mmHg and had a single-channel conductance of 98 ± 4 pS (n = 6; ± standard error of mean [s.e.m.]). Remarkably, in our experiments, MscL with its large current of approximately 180 pA, often opened before YnaI (five out of six recordings) at an average pressure of 140.2 ± 7.5 mmHg (Fig. 7a, b). From the six recordings, the activation threshold ratio between MscL and YnaI (PL/PY) was calculated as 0.96 ± 0.02 (n = 6; ± s.e.m.). These observations confirm that YnaI, in the context of a native E. coli membrane and using a pressure ramp, has a very high activation threshold. On the other hand, when the pressure was released from the patch membranes at the same rate, YnaI closed significantly later, at a pressure of −67.3 ± 5.2 mmHg, than MscL, at a pressure of −112.0 ± 2.5 mmHg (Fig. 7a inset, b), revealing that the threshold of YnaI for closing is much smaller than its threshold for opening. YnaI is thus another example of an MscS-like channel, such as plant channel AtMSL1034,35 and MscCG from Corynebacterium glutamicum36, that shows much stronger gating hysteresis than the very weak gating hysteresis of MscS37. Note that strong gating hysteresis was only observed for YnaI but not for MscL in the same patch membranes.

Pressure applied to inside-out excised patches and channel currents shown in red and black, respectively. Pipette potential was +60 mV, except +50 mV for panel c. a Representative recording (n = 6) from a giant spheroplast from E. coli strain MJF431 (lacking MscS, MscK and MscM) overexpressing YnaI. Black circle: first MscL opening. Dashed lines: first YnaI opening and last YnaI closing. Inset: magnified view of YnaI currents in region indicated by blue box. C and O1-O3: currents resulting from closed and one to three open YnaI channels. Statistical significance assessed using unpaired two-sided Welch’s unequal variances t-test. b Thresholds for opening and closing of MscL (black) and YnaI (blue). p-value calculated by Welch’s unequal variances t-test shows that YnaI and MscL close at statistically significant different pressures (n = 6). The box-and-whisker plot shows the median current (line), the upper and lower quartiles (box), and the upper and lower extremes (whiskers). c Representative recording (n = 3) from a giant spheroplast from E. coli strain MJF612 (lacking MscL, MscS, MscK and YbdG) overexpressing YnaI shows single-channel opening and closing events (O1-O3, number of open channels). Dashed lines: first YnaI opening and last YnaI closing. d Fast opening kinetics and strong inactivation of MscS in response to pressure steps (left) (Figure adapted from ref.36). Representative recording (n = 3) from a giant spheroplast generated from E. coli strain MJF612 overexpressing YnaI in response to increasing pressure steps from −80 mmHg to −130 mmHg in −10 mmHg intervals. YnaI responds to the pressure pulses slowly and does not show inactivation (right). e Representative recording from a giant spheroplast of E. coli strain MJF612 overexpressing MscS (top) or YnaI (bottom) in response to various pressure ramps. Dashed lines indicate changes in peak currents with fast to slow pressure ramps. f Representative recording (n = 3) from a giant spheroplast from E. coli MJF431 overexpressing YnaI. Black circle: first MscL opening. Below horizontal dashed line, the number of activated YnaI channels increased when this slow pressure ramp was applied. Insets: zoomed-in views of YnaI currents in regions indicated by blue boxes.

To better characterize the channel function, we expressed YnaI in E. coli strain MJF612 (∆MscL, ∆MscS, ∆MscK, ∆YbdG) that lacks MscL. In the absence of the large MscL currents, YnaI currents could be clearly observed when the ramp pressure was applied to patch membranes. The first YnaI channel opened at a pressure of −151 mmHg, and at the maximum pressure used of −200 mmHg more than six YnaI channels were activated (Fig. 7c). Consistent with the results obtained with the MJF431 strain, YnaI also showed strong gating hysteresis in the MJF612 strain, with the last channel closing at a pressure of −81 mmHg (Fig. 7c). Repetitions yielded opening and closing thresholds for YnaI of −144.0 ± 10.2 mmHg and −58.0 ± 10.6 mmHg, respectively (n = 3; mean ± s.e.m.).

To examine whether YnaI channels inactivate under constant pressure as reported for MscS, we applied increasing pressure steps to patch membranes (Fig. 7d, right panel). YnaI currents rose slowly to a plateau and remained there under constant pressure. This behavior is opposite from MscS whose currents rise quickly to a maximum and then gradually decline due to inactivation36 (Fig. 7d, left panel). These observations suggest that YnaI has much slower gating kinetics than MscS and that YnaI does not have a inactivation mechanism, consistent with previous results obtained for YnaI22 and previously shown for other MscS-like channels, such as plant channels AtMSL1034,35 and FLYC138.

The slow gating kinetics and lack of inactivation of YnaI are not features consistent with a fast response to a sudden osmotic downshock but suggest that YnaI has evolved to respond to slow osmotic changes. We further tested this notion by using different pressure ramps. In the case of MscS, as reported before39 and reproduced here (Fig. 7e, top), slower pressure ramps result in decreasing peak currents, a consequence of its inactivation mechanism. In contrast, YnaI shows increasing peak currents with slower pressure ramps (Fig. 7e, bottom). The fact that more YnaI channels open with slower pressure ramps illustrates that YnaI indeed responds best to slow osmotic changes. While the number of channels that open clearly depends on the speed of the pressure ramp, even in recordings using slow pressure ramps, YnaI still showed strong hysteresis (Fig. 7e, bottom). This result proves that the gating hysteresis is an inherent feature of YnaI and implies that it has different gating pathways for opening and closing.

To establish whether the activation threshold of YnaI depends on the speed of the pressure ramp, we expressed YnaI in E. coli strain MJF431, to use the endogenous MscL as reference for its activation threshold, and prepared giant spheroplasts. By applying a slow pressure ramp to the excised membrane patch, we observed the activation of numerous YnaI channels (Fig. 7f), as previously seen when YnaI was expressed in the MJF612 strain (Fig. 7a). The first YnaI channel opened at −125 mmHg, close to when the first MscL channel opened (Fig. 7f). In contrast, the last YnaI channel closed at -86 mmHg, at a much smaller pressure than when the last MscL channel closed, which occurred at −137 mmHg (Fig. 7f). Repetitions yielded opening and closing thresholds of −135.7 ± 6.7 mmHg and −84.7 ± 14.5 mmHg for YnaI (n = 3; mean ± s.e.m.), and of −158.0 ± 4.7 mmHg and −150.0 ± 5.2 mmHg for MscL (n = 3; mean ± s.e.m.). The activation threshold ratio between MscL and YnaI (PL/PY) obtained with the slow pressure ramp is 1.17 ± 0.04, which differs from that obtained with the fast pressure ramp of 0.96 ± 0.02. This difference is statistically significant as assessed by unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test (p-value of 0.019), indicating that the gating threshold for YnaI opening becomes lower with slower pressure ramps.

Discussion

Several groups have already studied the structure and function of YnaI20,21,22,23,24, but a full understanding of its activation mechanism and biological function remained elusive. In particular, while a previous study succeeded in determining structures of YnaI in a closed-like, an intermediate and an open-like conformation, the structures did not provide a full understanding of the mechanistic basis for its gating22. Since we recently introduced cyclodextrins as a universal tool to study mechanosensitive channels by extracting lipids from a membrane and thus mimicking membrane tension15,30,31, we used this approach to study YnaI. Exposure of patched membranes to βCD indeed activated the incorporated YnaI channels, shortly before membrane rupture. However, when we determined the structure of nanodisc-embedded YnaI after incubation with βCD, the model revealed that the channel remained in the closed conformation. In a recent study on mechanosensitive OSCA channels, βCD incubation also failed to yield the structure of the nanodisc-embedded channel in the open conformation40.

All other approaches we pursued to obtain a cryo-EM structure of YnaI in the open state, namely incubation with LPC as well as introducing mutations and hydrophobic mismatch, were also not successful. In contrast to βCD, incubation with LPC and all introduced mutations also failed to open YnaI in electrophysiological experiments. Of note, our result that LPC does not open YnaI is inconsistent with a previous study that was able to use LPC to obtain structures of YnaI in an open-like and an intermediate conformation22. However, these cryo-EM structures also do not align well with other results. In particular, these conformations were only observed after the YnaI channels in the LPC-treated liposomes were extracted with DIBMA22 whereas cryo-EM analysis of the YnaI channels in LPC-treated liposomes before DIBMA extraction only revealed the closed-like conformation41. Furthermore, previous electrophysiologic studies on YnaI22,25 as well as our own (Fig. 7) only identified closed and open states but detected no sub-conducting states or inactivation, so that it is not immediately obvious what functional state the observed intermediate state would correspond to. Taken together, it is possible that the previous structures of YnaI in an open-like and an intermediate conformation do not represent physiologically meaningful conformations induced by LPC but instead may be an artificial effect of extracting YnaI from the membrane with DIBMA.

Compared to MscS, YnaI only features two additional peripheral transmembrane helices per subunit, leaving the fold of the MscS core mostly unchanged. Yet a detailed electrophysiological characterization shows that the functional characteristics of YnaI differ greatly from those of MscS. The cryo-EM structure and MD simulations show that the additional helices of YnaI change how the protein interacts with lipids. None of the cryo-EM maps of lipid-embedded YnaI determined to date show any indication of pore or gatekeeper lipids that are present in MscS13,14,15. However, our maps show larger and better-defined density for the pocket lipids in YnaI than that observed for the pocket lipids in any MscS map, indicating that more, but less mobile, lipids occupy the YnaI pockets, a result supported by our MD simulations. The reduced mobility of the pocket lipids is likely the result of the two additional helices of YnaI, which lift the MscS-like core of YnaI and thus also the lipid-filled pockets further out of the membrane than in MscS. Moreover, due to the additional helices, the pocket lipids in YnaI make more interactions with the channel than the pocket lipids in MscS. Since the pocket lipids must leave the pockets in MscS for the channel to transition into the open state, the molecular implementation of the lipids-move-first model9, the increased separation of the YnaI pocket lipids from the bulk membrane and their increased interactions with the channel itself may explain why YnaI is much less sensitive to membrane tension than MscS. Furthermore, considering the reduced mobility of the pocket lipids in YnaI compared to those in MscS, it is also possible that none or less of them leave the pockets in response to membrane tension. It thus appears that the additional YnaI helices converted the function of the pocket lipids from an element that responds to membrane tension and is intricately involved in channel gating in MscS to a more structural element in YnaI. In other words, current evidence suggests that it is more likely that YnaI is not gated by the lipids-move-first mechanism.

Maybe the greatest riddle with respect to YnaI concerns its physiological role. In a hypoosmotic stress assay, overexpression of YnaI rescues the survival of the E. coli Δ7 strain, in which all seven of its mechanosensitive channels have been deleted25, showing that YnaI function suffices to prevent cell lysis. On the other hand, wild-type E. coli cells also express MscL, which also opens at the near-lytic membrane tension required for YnaI to open and provides a much larger conductance, rendering the function of YnaI apparently superfluous. However, because the 28 Å pore of MscL is very large once the channel is fully activated42, the cell loses important cytoplasmic solutes and even small proteins (e.g.43). Therefore, MscL opens for only very short periods before closing again, thus minimizing loss of cytoplasmic solutes. YnaI, unlike MscS, does not inactivate and our electrophysiologic characterization revealed that it has a substantial gating hysteresis. Therefore, once YnaI opens, it remains open for much longer than MscL, which, as YnaI only conducts ions, poses no risk of losing essential solutes from the cytoplasm but provides for an extended period of allowing the osmotic pressure in the cytoplasm to adjust to that of the outside environment, thus improving the survival chances of the bacterium.

Is this, however, a physiologically realistic scenario? Our electrophysiologic measurements established at which pressures MscL and YnaI open and close (Fig. 7b). Based on the measured membrane tension at which MscL opens (~ 10 mN/m44), we can convert pressure to membrane tension, showing that MscL closes at a still dangerously high membrane tension of ~8 mN/m whereas YnaI closes at the lower membrane tension of ~4.8 mN/m, similar to the tension at which MscS opens (~ 5 mN/m44). These results establish that YnaI, at least in principle, could lower membrane tension to a safe level.

Considering that initial cell disruption events occur 200–1000 ms after downshock45, a question that arises is whether YnaI lowers the membrane tension to a safe level in a sufficiently fast manner. It has been estimated that upon a hypoosmotic shock, E. coli adapted to 500 mM NaCl needs to release ~5 × 108 osmotically active solutes in a few milliseconds to rebalance with a surrounding medium of ~200 mOsm46. Based on the conductance of 98 pS we measured for YnaI and assuming a very conservative membrane potential of 20 mV (the membrane potential of E. coli was measured to be −142 mV47), the ion flux through a single YnaI channel comes to 1.22 × 104 ions/ms (see Supplementary Information). Hence, it would take 40,000 ms for a single YnaI channel to release the required 5 × 108 ions. Since an analysis of quantitative mass spectrometry data48 estimated that E. coli expresses ~30 YnaI channels49, it would take the 30 YnaI channels present in E. coli ~ 1.3 seconds to release the required ions. This estimate is based on YnaI alone, but since E. coli also expresses MscL and MscS, which will release a large number of osmotically active solutes and ions, the remaining number of ions that YnaI has to release will be much smaller and will thus likely be accomplished within a few hundred milliseconds at most.

It is also important to consider the effect of the rate at which the membrane tension increases on the activation of bacterial mechanosensitive channels. Using a hypoosmotic shock assay that exerts a fast shock, MscS and MscL expressed at their native levels sufficed for >95% of cells to survive5. In contrast, stopped-flow experiments, which allow the rate of the osmotic shock to be controlled, demonstrated that the MJF465 mutant strain, which lacks MscL, MscS and MscK, can survive slow osmotic shocks and that the survival rate depends on the rate of the osmotic change49. These results suggest that the MscS-like channels expressed in the MJF465 strain at their native levels, namely YnaI, YbiO, YbdG, and MscM, while not essential for surviving abrupt osmotic changes, are sufficient to help cells survive slow osmotic changes. Consistent with this notion, our electrophysiological experiments show that the slow gating kinetics, the reduction in activation threshold with slower pressure changes, and lack of inactivation of YnaI (Fig. 7d) results in many more YnaI channels being activated by slow pressure ramps (Fig. 7e). This finding indicates that unlike MscS and MscL, which react to sudden osmotic changes, YnaI is best suited to respond to slow osmotic changes.

In conclusion, we propose a model for how YnaI may work in concert with MscL and MscS to protect E. coli cells in the scenario of fast and slow osmotic changes. For a fast osmotic change, MscS starts to open at a tension of ~5 mN/m to release ions. However, if MscS is not able to alleviate the rapid increase in membrane tension, the membrane tension continues to increase, which leads to the activation of MscL when the tension reaches ~10 mN/m. MscL opens a large pore in short bursts, quickly releasing large amounts of osmotically active solutes and counteracting further increase in membrane tension. If opening of MscS and MscL reduces membrane tension quickly, not many YnaI channels will have opened due to its slow gating kinetics while not many MscS channels have inactivated. Therefore, MscS and MscL are most important for bacterial survival of fast osmotic changes. In contrast, for slow osmotic changes, MscS channels will also start to open at a tension of ~5 mN/m, but, if this does not reduce the membrane tension, they will gradually inactivate over time. As membrane tension continues to increase, it will activate MscL channels but also an increasing number of YnaI channels. MscL releases a large amount of osmotically active solutes but closes at a still high membrane tension of ~8 mN/m. In contrast, due to their large gating hysteresis, YnaI channels will remain open and can decrease membrane tension to ~4.8 mN/m, thus taking over the role of the inactivated MscS channels. Altogether, we suggest that the physiological role of YnaI is to help bacteria to survive slow osmotic changes, providing an example for how the different MscS-like channels provide a means for bacteria to survive dynamic changes in the osmotic environment.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Wild-type Escherichia coli YnaI with a C-terminal 6xHis tag was cloned into the pET20-b vector, which was then used to transform E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The cells were grown at 37 °C in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin. When the culture reached an OD600 of approximately 0.8, protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.4 mM and incubated for 16 h at 20 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended and lysed by sonication in Lysis Buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme) supplemented with one tablet of cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Membranes were pelleted by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4 °C, resuspended in Buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl), and then solubilized with the addition of 2% dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM). The solubilized membranes were clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated with 4 ml nickel-affinity resin (Qiagen) and washed with 50 column volumes (CV) of 30 mM imidazole in Buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl and 0.025% DDM). The protein was eluted with 10 CV of 250 mM imidazole in Buffer B, concentrated with Amicon Ultra 15 ml 50 kDa cut-off centrifugal filters (Millipore Sigma), and loaded onto a Superose 6 Increase 10/300GL size-exclusion column (Cytiva) equilibrated with Buffer B. Fractions containing YnaI were pooled and used immediately for reconstitution into nanodiscs or frozen at −80 °C for later use.

Point mutations were introduced in YnaI using the Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA for the chimeric channel consisting of MscS residues 1–31 and YnaI residues 78–343 was synthesized and cloned into the pET-20b(+) vector by GenScript. All mutant YnaI proteins were expressed and purified as described for wild-type YnaI.

Reconstitution of YnaI into nanodiscs

Most lipids (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, DOPC; 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine-N-(Cyanine 5), cy5-DOPC; 1,2-didecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, DDPC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids and used to prepare 10 mg/ml stock solutions in 5% DDM in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 300 mM NaCl. L-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) from egg yolk was purchased from Sigma. The types of MSPs and detergent-solubilized lipids as well as the mixing ratios used for nanodisc reconstitution are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. After a 20 min incubation, the detergent was removed by the addition of 30% (v/v) Bio-Beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad) for 4 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation. The sample was then transferred to a new tube of 30% Bio-Beads and incubated overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation. The Bio-Beads were allowed to settle by gravity and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. The sample was loaded onto a Superdex200 10/300 size-exclusion column equilibrated with 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 300 mM NaCl to remove empty nanodiscs and aggregated protein. Peak fractions containing YnaI in nanodiscs were pooled and used to prepare vitrified samples for cryo-EM.

Lipid extraction from YnaI-containing nanodiscs with β-cyclodextrin (βCD)

Lipid extraction from YnaI-containing nanodiscs was performed as previously described15. To determine the optimal incubation time, YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs were incubated with 100 mM β-cyclodextrin (βCD). After 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 11 h, and 24 h, a 100-μl aliquot was taken and loaded onto a Superose6 5/150 column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and 300 mM NaCl to separate YnaI-containing nanodiscs from βCD and aggregates. An incubation time of 24 h was deemed optimal. Peak fractions from this sample containing nanodisc-embedded YnaI were pooled and concentrated to 0.2 mg/ml to prepare vitrified samples for cryo-EM.

Treatment of channel-containing nanodiscs with lyso-phosphatidylcholine (LPC)

YnaI in DOPC/spNW2550 nanodiscs at ~0.05 mg/ml was incubated with L-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) (Sigma) at a final concentration of 5 μM for 16 h at 4 °C and then used for cryo-EM sample preparation as described below.

MscS was expressed, purified, and reconstituted into nanodiscs with DOPC and MSP1E3D1 as described before15 using a molar MscS:MSP1E3D1:DOPC ratio of 1:20:200. The sample was concentrated to ~0.1 mg/ml, incubated with LPC at a final concentration of 3 μΜ for 10 min, and then used for cryo-EM sample preparation as described below.

EM specimen preparation and data collection

The homogeneity of all samples was first examined by negative-stain EM with 0.7% (w/v) uranyl formate as previously described51. The protein concentration was measured with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and adjusted to between 0.3–0.6 mg/ml. Aliquots of 3 μl were applied to glowed-discharged Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 Cu 400 mesh grids with graphene oxide support (Electron Microscopy Sciences) using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For YnaI-containing nanodisc samples, the Vitrobot was set at 10 °C and 100% humidity with a 20 s delay after sample application before blotting the grids for 0.5–2 s with a blot force of 0. For the MscS-containing nanodisc sample, the Vitrobot was set at 4 °C and 100% humidity and after 30 s, the grids were blotted for 2–3 s with a blot force of 0. Grids were then plunged into liquid nitrogen-cooled ethane.

All YnaI samples were imaged in the Cryo-EM Resource Center at the Rockefeller University using 300-kV Titan Krios electron microscopes (Thermos Fisher Scientific) operated with SerialEM52 and equipped with a K3 direct detector camera. Data were recorded in super-resolution counting mode at a nominal magnification of 81,000x, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 0.86 Å at the specimen level, and using a defocus range of −1 to −2.5 µm.

For YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs, 5472 movies were collected at a dose rate of 35 e–/s/pixel. Exposures of 1.5 s were dose-fractionated into 50 frames of 0.03 s, resulting in 1.42 e–/Å2/frame and a total dose of 70.98 e–/Å2.

For YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs after βCD incubation, 5285 movies were collected; for YnaI in DOPC/spNW25 nanodiscs after LPC incubation, 5760 movies were collected; for YnaI A155V in DDM, 7140 movies were collected; for YnaI in DDPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs, 6480 movies were collected; and for the MscS/YnaI chimera in DOPC/MSP1E3D1 nanodiscs, 7077 movies were collected. Movies were collected at a dose rate of 27 e–/s/pixel, and exposures of 1.5 s were dose-fractionated into 50 frames of 0.03 s, resulting in 1.095 e–/Å2/frame and a total dose of 54.76 e–/Å2.

MscS in DOPC/MSP13ED1 nanodiscs after LPC incubation was imaged at the New York Structural Biology Center using a 300 kV Titan Krios electron microscope operated with Leginon53 using counting mode and a defocus range of −0.8 to −2.0 µm. 6991 movies were collected with a K3 direct detector camera at a nominal magnification of 105,000x, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 0.84 Å at the specimen level. The dose rate was set to 25 e–/s/pixel, and 1.5 s exposures were dose-fractionated into 50 frames of 0.03 s, resulting in 1.053 e–/Å2/frame and a total dose of 52.64 e–/Å2.

Cryo-EM data collection parameters are summarized in Supplementary Tables 2–4.

Cryo-EM image processing

For all YnaI data sets, collected movie stacks were gain-normalized, motion-corrected, dose-weighted and binned over 2 × 2 pixels in Motioncorr254. The contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters were determined with CTFFIND4.155 implemented in RELION. The micrographs were curated by average defocus value, CTF fit resolution, CTF cross correlation, and manual inspection. All image processing was performed with RELION-3.156 and cryoSPARC57 version 4.5. All ab-initio reconstructions, 3D classifications and refinements were performed with C7 symmetry enforced.

For YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs, curation yielded 5472 motion-corrected micrographs. Blob picking was performed using Gautomatch 0.56 without templates, yielding 598,403 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned 5-fold, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Five class averages showed well-resolved structural features and were used as templates to re-pick the micrographs with Gautomatch, which yielded 1,083,210 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned 5-fold, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. 26 classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined, yielding 928,273 particles. A subset of this particle stack (628,016 particles from 14 classes) was used to generate an ab-initio model in cryoSPARC. 209,065 particles from 2D classes with junk features were used to create three decoy maps by starting ab-initio reconstructions that were aborted after the first iteration. The ab-initio model and 3 decoy maps were used to seed a heterogeneous refinement with the full particle stack into 4 classes in cryoSPARC. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 563,719 particles were re-extracted without binning in RELION and subjected to heterogeneous refinement into 3 classes in cryoSPARC, using the good density map from the previous heterogeneous refinement as reference map. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 338,501 particles were subjected to non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. To improve the density for the peripheral TM-N2 helix, the particles were subjected to 3D classification without alignment into 10 classes in cryoSPARC, using a mask to focus the classification on the transmembrane domain. One class with 40,124 particles showed well-resolved density for all transmembrane helices and the map was further improved by non-uniform refinement and sharpening in cryoSPARC. The final map had a resolution of 2.5 Å based on gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (GSFSC) and a cut-off criterion of FSC = 0.143. Local-resolution estimates for the final map were calculated in cryoSPARC.

For YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs after βCD incubation, curation yielded 5,166 motion-corrected micrographs. Blob picking was performed using Gautomatch without templates, yielding 1,148,473 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Five class averages showed well-resolved structural features and were used as templates to re-pick the micrographs with Gautomatch, which yielded 2,565,002 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 5 × 5 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. 25 classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined, yielding 1,820,122 particles. A subset of this particle stack (557,635 particles from 5 classes) was used to generate an ab-initio model in cryoSPARC. 1,274,940 particles from 2D classes with junk features were used to create three decoy maps. The ab-initio model and 3 decoy maps were used to seed a heterogeneous refinement with the full particle stack into 4 classes in cryoSPARC. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 882,106 particles were re-extracted without binning in RELION and subjected to heterogenous refinement into 2 classes in cryoSPARC using the good density map from the previous heterogeneous refinement as reference map. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 616,471 particles were subjected to non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. To improve the density for the peripheral TM-N2 helix, the particles were subjected to 3D classification without alignment into 6 classes in cryoSPARC, using a mask to focus the classification on the transmembrane domain. One class with 130,915 particles showed well-resolved density for all transmembrane helices and the map was further improved by non-uniform refinement and sharpening in cryoSPARC. The final map had a resolution of 2.5 Å based on GSFSC and a cut-off criterion of FSC = 0.143. Local-resolution estimates for the final map were calculated in cryoSPARC.

For YnaI in DOPC/spNW25 nanodiscs after LPC incubation, curation yielded 2856 motion-corrected micrographs. Blob picking was performed using Gautomatch without templates, yielding 765,767 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Six class averages showed well-resolved structural features and were used as templates to re-pick the micrographs with Gautomatch, which yielded 1,051,383 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. 21 classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined and the corresponding 997,348 particles were used to generate an ab-initio model that was used to seed a 3D classification into 4 classes in RELION. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 154,047 particles were subjected to another round of 3D classification into 4 classes in RELION. Three of the resulting classes showed well-resolved structural features and were combined. The corresponding 128,518 particles were re-extracted without binning in RELION and subjected to non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. To improve the density for the peripheral TM-N2 helix, the particles were subjected to 3D classification without alignment into 6 classes in cryoSPARC, using a mask to focus the classification on the transmembrane domain. Two classes showed well-resolved density for all transmembrane helices and the corresponding classes were combined, yielding 44,418 particles. The map was further improved by non-uniform refinement and sharpening in cryoSPARC. The final map had a resolution of 3.0 Å based on GSFSC and a cut-off criterion of FSC = 0.143. Local-resolution estimates for the final map were calculated in cryoSPARC.

For A155V mutant YnaI in DDM, curation yielded 7140 motion-corrected micrographs. Blob picking was performed using Gautomatch without templates, yielding 2,481,666 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 5 × 5 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Three class averages showed well-resolved structural features and were used as templates to re-pick the micrographs with Gautomatch, which yielded 2,443,261 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 5 × 5 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Four classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined, yielding 1,838,380 particles. These particles were used to generate three ab-initio models in cryoSPARC. All particles were also used to create three decoy maps. The best ab-initio model and the 3 decoy maps were used to seed a heterogeneous refinement with the full particle stack into 4 classes in cryoSPARC. This step was repeated two more times using the same seeds. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 826,975 particles were subjected to another round of heterogeneous refinement into 4 classes in cryoSPARC using as seeds the same maps used for the first heterogeneous refinement. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 729,300 particles were re-extracted without binning in RELION and subjected to non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. The resulting map showed poor density for the transmembrane helices and the particles were therefore subjected to 3D classification without alignment into 10 classes in cryoSPARC, using a mask to focus the classification on the transmembrane domain. Two classes, with 80,640 and 73,180 particles, showed well-resolved density for the transmembrane helices in distinct conformations. These two maps were separately improved by non-uniform refinement and sharpening in cryoSPARC. Both maps did not resolve TM-N2. The final maps had a resolution of 2.8 Å based on GSFSC and a cut-off criterion of FSC = 0.143. Local-resolution estimates for the final map were calculated in cryoSPARC.

For YnaI in DDPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs, curation yielded 6480 motion-corrected micrographs. Blob picking was performed using Gautomatch without templates on a subset of 1949 micrographs, yielding 720,504 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 5 × 5 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Eight class averages showed well-resolved structural features and were used as templates to re-pick all the micrographs with Gautomatch, which yielded 1,076,654 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 5 × 5 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. 13 classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined, yielding 795,013 particles. All the particles were used to generate an ab-initio model in cryoSPARC. A subset of this particle stack (1605 particles from 6 classes with junk features) was used to create three decoy maps. The ab-initio model and 3 decoy maps were used to seed a heterogeneous refinement with the full particle stack into 4 classes in cryoSPARC. One class with well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 373,386 particles were re-extracted without binning in RELION and subjected to heterogeneous refinement into 3 classes in cryoSPARC using the good density map from the previous heterogeneous refinement as reference map. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 246,123 particles were subjected to non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. To improve the density for the peripheral TM-N2 helix, the particles were subjected to 3D classification without alignment into 6 classes in cryoSPARC, using a mask to focus the classification on the transmembrane domain. One class with 67,108 particles showed well-resolved density for all transmembrane helices and the map was further improved by non-uniform refinement and sharpening in cryoSPARC. The final map had a resolution of 2.3 Å based on GSFSC and a cut-off criterion of FSC = 0.143. Local-resolution estimates for the final map were calculated in cryoSPARC.

For the MscS/YnaI chimera in DOPC/MSP1E3D1 nanodiscs, curation yielded 4290 motion-corrected micrographs. Blob picking was performed using Gautomatch without templates, yielding 1,395,202 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. Seven class averages showed well-resolved structural features and were used as templates to re-pick the micrographs with Gautomatch, which yielded 2,890,888 particles. The particles were extracted into 360 × 360-pixel boxes, binned over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in RELION. 13 classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined, and the resulting 2,127,486 particles were subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes in cryoSPARC. 12 classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined, and the resulting 770,462 particles were subjected to heterogeneous refinement into 4 classes in cryoSPARC. To seed this heterogeneous refinement, two copies each of EMDB maps 2,1463 (MscS in a sub-conducting state) and 21,464 (MscS in a inactivated state) were used. One class showed well-resolved structural features, and the corresponding 282,233 particles were re-extracted without binning in RELION and subjected to non-uniform refinement in cryoSPARC. The final map had a resolution of 2.5 Å based on GSFSC and a cut-off criterion of FSC = 0.143. Local-resolution estimates for the final map were calculated in cryoSPARC.

For MscS in DOPC/MSP1E3D1 nanodiscs after LPC incubation, all data processing was performed in cryoSPARC v4.5. The collected 6991 movies were gain-normalized, motion-corrected and dose-weighted using Patch Motion Correction. The CTF parameters were determined using Patch CTF Estimation. CTF fit resolution, defocus range and relative ice thickness were used to curate the motion-corrected micrographs, and 5151 micrographs were selected for further processing. Particles were first picked using Blob picker on a random subset of 300 micrographs, which yielded 226,905 particles. The particles were extracted into 320 × 320-pixel boxes, binning over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 50 classes. Four classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were selected for template picking of the same subset of 300 micrographs, resulting in a particle stack of 347,956 particles. These particles were subjected again to 2D classification into 50 classes. Classes that showed the clearest features of MscS were selected and subjected to a second round of 2D classification into 50 classes. Eight classes with averages showing well-resolved structural features were combined and the corresponding 19,259 particles were used to train a Topaz picking model58 over 10 epochs, with an expected particle number of 400 per micrograph. The Topaz picking model was then used to pick particles from all micrographs, yielding 6,508,443 particles. The particles were extracted into 320 × 320-pixel boxes, binned over 4 × 4 pixels, normalized, and subjected to 2D classification into 100 classes. 25 classes showing well-resolved structural features were combined and the corresponding 2,426,514 particles were subjected to a final round of 2D classification into 100 classes.

Model building and refinement

To build an atomic model into the density map of YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs, the previously determined cryo-EM structure of YnaI (PDB: 6URT) was rigid-body docked into the cryo-EM map in UCSF ChimeraX59. One monomer of the model was then refined using real-space refinement in Coot 0.8.960. Lipids with a PE headgroup and saturated 20 carbon-long acyl chains were first rigid-body fitted into densities representing pocket lipids, followed by real-space refinement in Coot. Then, terminal carbons in the lipid acyl chains were deleted to match the densities, followed by further manual adjustment and real-space refinement in Coot. The protein-and-lipids model for one monomer was further refined in Phenix 1.17.161 (phenix.real_space_refine). Then, seven copies of the refined monomer were docked into the cryo-EM map using Phenix (phenix.dock_in_map), followed by a final round of refinement in Phenix (phenix.real_space_refine) to resolve any clashes between monomers. The density for TM-N2 had lower resolution and only allowed the modeling of a poly-alanine peptide. This structure was used as starting model to build atomic models into the density maps of YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs after βCD incubation, YnaI DOPC/spNW25 nanodiscs after LPC incubation, and YnaI in DDPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs, which were then refined as described above. For each map, the density for the pocket lipids was inspected, and the position and length of the acyl chains were further refined and adjusted manually as needed in Coot.

The two maps of the A155V mutant YnaI in DDM did not resolve TM-N2, which was thus not modeled. The density for TM1 and TM-N1 had considerably poorer resolution in both maps compared to that in all other YnaI maps. For A155V-1, side chains were assigned only to a portion of TM1, while the rest of TM1 and TM-N1 were modeled as poly-alanine chains. For A155V-2, the entirety of TM1 and TM-N1 were modeled as poly-alanine chains. In both maps, non-protein density in the hydrophobic pockets of YnaI was observed but was not as clear as in all other YnaI maps and could not be confidently identified as either lipid or detergent molecules. Thus, only acyl chains were modeled.

The map of the MscS/YnaI chimera did not resolve TM1 and TM2. The model of YnaI in DOPC/MSP2N2 nanodiscs was rigid-body docked into the cryo-EM map of the MscS/YnaI chimera in UCSF ChimeraX, and all transmembrane helices except TM3 were deleted. The model was refined using real-space refinement in Coot and Phenix (phenix.real_space_refine).

All models were validated using Phenix (phenix.validation_cryoem). Map-to-model FSC curves were calculated with Phenix (phenix.mtriage). Refinement and validation statistics are provided in Supplementary Tables 2–4.

The pore radius of YnaI was determined using the program HOLE v2.228 using an end radius of 30 Å. The pore radius along the YnaI axis was determined by calculating the distance between the center of the pore and the surface of the pore determined by HOLE for each point along the axis.

Quantification of βCD-mediated lipid removal from YnaI-containing nanodiscs

βCD-mediated lipid removal was quantified as described before15. Briefly, unlabeled DOPC and Cy5-labeled DOPC (Avanti Polar Lipids) in chloroform were mixed at a molar ratio of 17:1. The lipid mixture was first dried under a stream of argon gas and further dried under vacuum overnight. The lipid film was solubilized with 5% DDM and used to reconstitute YnaI into MSP2N2 nanodiscs. The YnaI-containing nanodiscs were then incubated with βCD as described. Gel-filtration peak fractions before and after βCD treatment were adjusted to a similar protein concentration (0.3–0.6 mg/ml), and light absorption was measured at 280 nm and 650 nm with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each measurement was repeated five times and the averaged A650:A280 ratio was used as the Cy5-lipid-to-protein ratio. Three independent experiments were performed.

Preparation of YnaI liposomes and patch-clamp electrophysiology