Abstract

Electrolytic hydrogen can support the decarbonization of the power sector. Achieving cost-effective power-to-gas-to-power (PGP) integration through targeted emissions pricing can accelerate the adoption of electrolytic hydrogen in greenhouse gas-intensive power sectors. This study develops a framework for assessing the economic viability of electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP systems in fossil fuel-dependent grids, while considering the competing objectives of the electricity system operator, a risk-averse investor, and the government. Here we show that, given the risk-averse investor’s inherent pursuit of profit maximization, a break-even carbon abatement cost of at least 57 Canadian Dollars per tonne of CO₂ by 2030 from the government, with a shift in electricity market dispatch rules from sole system marginal price-reduction to system-wide emissions reduction, is essential to stimulate price discovery for low-cost hydrogen production and contingency reserve provision by the PGP system. This work can help policymakers capture and incentivize the role of electrolytic hydrogen in low-carbon power sector planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to combust hydrogen at end-use locations with near-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions enables it as an energy carrier to support GHG emission reduction plans in the power sector1. Hydrogen is also suitable for long-duration energy storage to balance seasonal variations in electricity systems that rely on renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and hydro2. Electrolytic hydrogen is produced by splitting water into its constituent elements using excess renewable energy; the produced hydrogen can be reconverted to electricity (gas-to-power) and dispatched to the grid3. Integrating electrolytic hydrogen-based power-to-gas-to-power (PGP) into the electricity system should result in a minimal cost increase for consumers while remaining cost-effective to deploy4. Thus far, PGP systems have been expensive to integrate into the power sector due to the uncertainty surrounding the value derived from the system under prevailing market rules in the power sector5,6. In this study, the value in the PGP system refers to the reduction in the electricity system costs or emissions achieved by integrating both the low-carbon hydrogen production technology (electrolyzer) and energy conversion technology (fuel cell) into the power sector. We view the cost of creating this value through the levelized cost of hydrogen (LCHV), which represents the discounted cost required to make the PGP system viable to build and operate over its lifetime.

Recent studies on the value of using electrolytic hydrogen in the power sector have several gaps. Prior studies examine the role of electrolytic hydrogen in enhancing system flexibility primarily in power sectors with high shares of renewable energy (more than 80 percent [%] of the power mix), which often limits the result replicability in emissions-intensive grids where competition with fossil fuel generation is significant and hydrogen-natural gas blending (even at acceptable blending limits) in gas turbines results in unjustifiably high electricity system costs7,8,9,10,11. Sepulveda et al12. found that in fossil fuel-dependent grids, flexible natural gas plants with carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) provide a more cost-effective pathway for emissions reduction than transitioning to a highly renewable energy grid and energy storage: this finding to the challenges inherent in renewable energy-based power sector decarbonization, such as significant costs associated with batteries, long-duration storage, and expanding multi-regional transmission lines to balance supply and demand mismatches. However, emissions pricing and key techno-economic factors influencing the cost-effective adoption of electrolytic hydrogen in power sectors shifting from coal to renewables, with natural gas as a bridge fuel, were not considered. There is, therefore, a gap in understanding the carbon-abatement costs required to expedite the cost-effective integration of the PGP system in existing emissions-intensive power sectors and induce long-term cost reduction.

Glenk and Reichelstein13 found that reversible fuel cells could help limit electricity price spikes during extreme weather events. However, the study13 assumed a perfect knowledge of wholesale electricity prices, while not examining whether reversible hydrogen conversion remains economically viable under imperfect day-ahead price forecasts. Incorporating imperfect foresight is vital for accurately representing electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP participation in wholesale markets, especially when renewable generation is constrained and thermal generators (including fuel cell operations) are scheduled in advance rather than post-incident in the reserve market14. Another study15 assessed the economic value of the PGP system using a macro-energy systems approach16, but did not include the profit-making context required for a risk-averse investor (or hydrogen producer)17 to determine the minimum levelized cost that justifies integrating PGP systems to maximize revenues from cost-effective hydrogen conversion, storage, and electricity dispatch in power sectors undergoing a low-carbon transition.

Here, we developed an integrated analytical framework that assesses the role of the PGP systems from three distinct value-creation perspectives in an emissions-intensive power sector: lowering electricity system costs (minimizing cost), reducing electricity system emissions (minimizing emissions), and yielding profit for the PGP system investor (maximizing profit). We then compare the integration of the PGP system in a stylized representation of a fossil fuel-dependent electricity system undergoing a low-carbon transition from competing pathways without coal use, a grid mix with a growing renewable energy penetration (HighRE grid), and another dominated by natural gas plants (HighNG grid). The framework is calibrated for the energy system in Alberta (a western Canadian province), drawing on available data for proposed timelines for retrofitting coal plants to natural gas, increasing renewable energy penetration, and the potential use of depleted oil wells and rock caverns for long-duration hydrogen storage18,19. The fossil-fuel-dependent power mix in Alberta provides a practical case for examining the value of the PGP system in an emissions-intensive power sector undergoing a low-carbon transition. However, the study findings extend to regions transitioning from coal power to a natural gas and renewable energy mix in the electricity system, with the models adaptable globally with adjustments to electricity demand and macroeconomic data (monetary values are in 2023 Canadian Dollars [$] unless stated otherwise).

We focused on the universal aspects of low-carbon transition, generation expansion planning and economic dispatch analysis in an emissions-intensive power sector, aiming to maintain a level of generality for the study findings to apply to other global contexts beyond the Canadian case modelled in this work. The LCHV and break-even abatement cost results obtained in this study for the HighRE and HighNG grids under varied PGP value-assessment scenarios are relevant to regions where natural gas serves as a bridge fuel for decarbonizing the power sector, particularly those with underground storage potential, such as the United States and Germany20. The derived break-even abatement cost in the HighNG grid type also indicates an approach to expedite the integration of the PGP system in regions with substantial coal use, but growing renewable energy deployment in the power sector, such as China and India21.

This study confirms earlier findings that there is no immediate economic rationale for integrating PGP systems in power sectors that are still heavily reliant on coal or natural gas without substantially increasing the share of renewable energy in the power sector22,23. However, the integration economics of the PGP system improve when renewable energy capacity surpasses 50% of the power mix. At this point, the fuel cell can complement wind or solar power to meet peak-period demand in the wholesale power market and hydropower in the reserve market, thereby reducing the involvement of thermal generators. The LCHV drops from $36 per kilogram of hydrogen (kgH₂) when wind and solar comprise 50% of the power mix to $10 per kgH₂ when wind, solar, and hydropower together reach 70%, highlighting the influence of renewable energy curtailment for electrolytic hydrogen production and the PGP system’s integration. We propose that providing a break-even abatement cost incentivizes the long-term emissions reduction value induced by the PGP system in an emissions-intensive power sector as the renewable energy capacity increases. For instance, a 50 megawatts (MW) PGP system installed by 2030 would require a break-even abatement cost of at least $57 per tonne of CO2 (tCO2) to be cost-effective.

The colocation of the electrolyzer and fuel cell technologies with transmission line and hydrogen storage access is assumed in this study. External infrastructure costs, such as the construction of long-distance hydrogen pipelines and transmission lines, could increase the LCHV. The pipeline cost required to connect non-captive hydrogen production locations may increase the LCHV by roughly $0.4 per kgH224, potentially impacting the cost competitiveness of the initial PGP system. However, this added infrastructure cost can be offset over multiple subsequent PGP installations due to their proximity to each other and the enabling infrastructure.

Results

An approach for the value assessment of the PGP system in the power sector

We examine the PGP system that produces hydrogen (at 20 bar) through water electrolysis (using either curtailed wind and solar or performing price arbitrage during competitive periods), compresses (at 100–150 bar) and stores the hydrogen (underground) for long durations, and then converts the stored hydrogen to electricity for dispatch through a fuel cell to the grid, when viable (Fig. 1a). The fuel cell competes in the electricity system to meet the periodic power demand in the energy-only market (primarily during peak periods or when competing for trading arbitrage) and the reserve market. The polymer electrolyte membrane technology is prioritized because it is compatible with fast dynamic responses on the grid and has a near-constant hydrogen conversion efficiency25. The fuel cell was chosen for its cold-start capability with no minimum operating hours when installed. The number of electrolyzers and fuel cells for optionality can be increased by n, where n is greater than or equal to zero, and either technology can be offline while the other is operational. We assume a lossless transmission system and location-independent hydrogen production and storage, eliminating the need for a pipeline network, which provides a lower bound for assessing the economic viability of long-duration energy storage in the electricity system8.

a Hydrogen produced using excess renewable energy or through price arbitrage, stored underground, and converted to electricity via a fuel cell for grid dispatch if competitive (the black and green arrows represent electricity and hydrogen flows, respectively, and n is an integer (greater than or equal to 0) that denotes the number of PGP system installations). The PGP system’s role in the power sector hinges on the generation expansion strategy for emissions reduction. b Electricity generation capacity shares (stacked bars) and emission factors (line chart) for the modelled high renewable energy (HighRE) and high natural gas (HighNG) grid types between 2020 and 2050. Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 provide the region-specific data considered to derive the long-term generation expansion capacities for each grid type in b.

Three models are soft-linked26 to gain insights into the temporal operation of the PGP system in the power sector under varied configurations and to determine conditions required for deployment (methods). We used the LEAP-Canada model27, an economy-wide energy systems model of Canada, to determine the capacity expansion of the power generation technologies that define the HighRE and HighNG grids between 2025 and 2050 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The renewable energy penetration in 2050 reaches 54% and 71% in the HighNG and HighRE grids, respectively (Fig. 1b). This value starts at 14% in 2020 (the base year with significant coal use) and increases to 28% (HighNG grid) and 40% (HighRE grid) in 2030. The remaining capacity shares are met by natural gas combined/open cycle gas turbines and cogeneration plants hybridized to the grid (methods). LEAP-Canada is integrated with a price-taker unit commitment and economic dispatch (UC-EDwithPGP) model that includes additional unit commitment characteristics such as generators’ shutdown/startup costs, minimum stable generation, and up/downtime (Supplementary Table 3), for accurate guidance on the periodic competition among all generation technologies. LEAP-Canada did not set the capacity of the PGP system nor model its involvement in the electricity system. Instead, the UC-EDwithPGP model solves a set of objective problems that minimize electricity costs and emissions or maximize profit for the PGP system in competition with other generation technologies (Supplementary Note 1).

The techno-economic characteristics of the PGP system are exogenously specified in line with research on long-duration energy storage and by the electric system operator28,29, and the cost-optimal PGP system capacity was intrinsically derived in the model (Table 1). To define the value creation context in the UC-EDwithPGP model, we assessed whether the PGP system reduces one or both of the energy-only and reserve market costs, which represent the wholesale price of the lowest-cost generator meeting forecasted demand and providing standby power during unexpected supply or demand fluctuations, respectively. Given the uncertainty in day-ahead planning reserves, we derived the periodic reserve requirements in the UC-EDwithPGP model by calculating the active operating reserves that can be procured to mitigate the most severe single contingency event in the electricity system and ensure a 15% planning reserve margin at all times30,31 (Supplementary Note 2). The technology with the lowest marginal cost, providing the active reserve, sets the reserve market price. The ramp rate and availability level influence the amount of operating reserve supplied by the thermal and hydro plants, while the variabilities of wind and solar generation limit their reserve market participation, enabling the fuel cell to fill this role if competitive: the operating cost of the PGP system is passed to the hydrogen producer as part of the levelized cost. Using the 2020 power mix from LEAP-Canada to validate the UC-EDwithPGP model, we achieved a 12% mean absolute percentage error in hourly electricity system costs compared to data from the electric system operator29, which is within the forecasting error range of 10% to 20% reported in a study by Morris32.

The UC-EDwithPGP model outputs are fed to an uncertainty-based levelized cost model built in the Regression, Uncertainty, and Sensitivity Tool (RUST)33 to calculate the levelized cost of hydrogen value and break-even emissions abatement cost, and to identify the techno-economic parameters that influence the cost-effectiveness of the PGP system to the level of sensitivity. Unlike typical one-at-a-time sensitivity analysis, RUST performs a global sensitivity analysis using the Morris34 design of experiments and Sobol’s variance-based analyses35 to identify the interdependence and interaction effects between inputs and deviations from an expected outcome. Uniform, programme evaluation and review technique (PERT), and normal distributions were applied to the timelines, cost-related, and rate-based techno-economic parameters, respectively (Supplementary Table 5).

Renewable capacity over 50% and reserve market involvement are key to cost-effective value

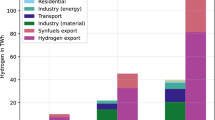

Figure 2a, b illustrates the electricity system’s energy-only cost and reserve cost, both without and with a 50 MW PGP system, between 2030 and 2050 under three different integration scenarios in the HighRE and HighNG grids. Figure 2c shows the LCHV (expressed in $ per kgH2) when the PGP system provides value to the electricity system. We increased the shares of coal in both grid types between 2025 and 2030 from 15–30% and found that no PGP system was required in the power sector under ideal operating conditions, as integrating the PGP system with limited curtailment of wind or solar energy to drive hydrogen production is not viable: this is reflected in the 2030 results where no LCHV was obtained. Thus, if a region has all-natural gas and no coal, the results are still applicable, given the limited curtailment that is taking place.

a–c Electricity system’s energy-only cost and reserve cost, as well as the PGP system’s LCHV, under the minimize cost, minimize emissions, and maximize PGP profit scenarios for the HighNG and HighRE grids in 2030 and 2050. The blue and red columns (panels a and b) are the electricity system costs without and with the PGP system integrated into the grid, respectively. The results in a and b should be read using the Without PGP system as the baseline. The LCHV plots are only for the cases with the PGP system. No information is plotted for the LCHV (c) if the PGP system is not viable in the power sector. Energy-only costs are higher under the minimize emissions and maximize PGP profit scenarios because of frequent thermal generator ramping. With high renewable energy penetration by 2050, the integrated PGP system displaces thermal plants, thereby lowering reserve market costs.

We derived value from the PGP system once the renewable energy capacity share reached ~50% on the grid, which is noticeable in 2050 in both the HighRE and HighNG grids. This outcome is consistent with similar work on the need for high renewable energy penetration to support electrolytic hydrogen use in the European energy system15. Integrating the PGP system by 2050 led to a 1–6% and 1–10% reduction in the respective energy-only and reserve market costs, depending on the grid type. Comparable reductions in electricity system costs driven by the PGP system are observed in the minimize emissions scenario. The LCHV results further reveal that the PGP system is cost-effective for reducing electricity costs in a HighRE grid (with seasonal droughts in wind production) and reducing emissions in a HighNG grid (Fig. 2c).

The maximize PGP profit scenario that prioritizes the risk-averse PGP system investor’s objective to achieve the lowest LCHV possible (~$4 per kgH2) increases the electricity system’s energy-only cost but reduces the reserve cost compared to the minimize cost scenario. Two implications are drawn from this outcome: (i) integrating the PGP system without assessing its impact on wholesale electricity system prices leads to increased frequency of thermal generator ramping irrespective of the renewable energy share in the power mix and (ii) the PGP system is most valuable in reducing the reserve market cost when limiting unexpected supply-demand mismatch, and it achieves this either by complementing hydropower in the HighRE grid or reducing the reliance on fossil fuel power plants in the HighNG grid. These findings align with the study by Glenk and Reichelstein13, which shows that reversible fuel cells can be economical by satisfying unexpected power supply shortfalls in fossil fuel-dependent electricity systems.

Cost-effective integration favours excess renewable energy curtailment and peak-period dispatch

We evaluated the impact of different hydrogen production and fuel cell dispatch strategies on value creation by the PGP system in the power sector. Shifting from an excess renewable energy curtailment approach to hydrogen production with price arbitrage36 does not improve the integration economics of the PGP system (Fig. 3a). Diverting non-surplus renewable energy to produce electrolytic hydrogen increases the average electricity system costs, as doing so requires more frequent ramping of high-cost thermal power plants. With a price-based arbitrage strategy, a risk-averse hydrogen producer may purchase electricity from the grid during periods of higher marginal prices to remain competitive. This approach limits the participation of the fuel cell in the electricity system, particularly in the reserve market, where ramped-up thermal generators ultimately displace it. Overbuilding renewable capacity to ~80% of the grid mix could potentially make price arbitrage viable by consistently lowering electricity prices and hydrogen production costs; however, uncertainties remain regarding its effectiveness in reducing the PGP system’s levelized cost37.

The figure illustrates the changes in electricity system costs and the resulting PGP system’s levelized cost of hydrogen value (LCHV) from a hydrogen production via excess renewable curtailment compared to price arbitrage, and b fuel cell electricity dispatch during peak periods compared to trading arbitrage. The electricity costs are benchmarked against the case without the PGP system in the power sector. A risk-averse PGP system integration strategy involves supplying only excess renewable energy to the electrolyzer and dispatching the fuel cell during periods of peak demand.

Comparing two fuel cell dispatch strategies – peak-period electricity sales versus unrestricted trading arbitrage – we found that peak-period dispatch to the wholesale power market provided a more cost-effective integration approach for the fuel cell within the power sector (Fig. 3b). This is because the peak-only dispatch mostly matches periods of high electricity demand, high electricity prices, and low renewable energy supply, allowing the fuel cell to sell electricity at a premium without increasing its operating cost. The peak-only strategy also supports electricity dispatch by the fuel cell during high-value periods to reduce the marginal cost of electricity and grid emissions and justify the involvement of the PGP system in the emissions-intensive power sector. While unrestricted dispatch may increase revenue generation, it also reduces the stack operating lifetime because of higher operational demands, leading to increased replacement costs and associated levelized costs of the PGP system in most cases.

Least-cost integration of the PGP system enhanced with new electricity market dispatch rules

We modelled the integration of the PGP system under varied configurations of the electricity system to assess the impact on electricity system costs and LCHV across three probable outcomes: best-case (highest positive impact), most likely (central tendency), and worst-case (least beneficial impact). The non-restrictive minimum bidding strategy, which disregarded the influence of the minimum stable generation requirement of dispatchable thermal generators during unit commitment, provided the best electricity system configurations for the integrated PGP system in terms of lowering the LCHV. With no compulsion to meet the minimum stable generation requirement of thermal power plants, generators with higher marginal costs are shut down for extended periods than previously realized. This revised dispatch strategy increases the involvement of the PGP system in the power sector, particularly within the reserve market, resulting in a ~13% reduction in reserve costs (Fig. 4a). The strategy also improves wind energy supply for hydrogen production and increases the energy conversion by the fuel cell during peak-demand periods to complement the lower-capacity thermal generators ramped up, whose minimum uptime requirements have a minimal impact on the day-ahead unit commitment.

The figure illustrates the relative change in electricity costs, grid emissions, and the PGP system’s levelized cost of hydrogen value (LCHV) under varied electricity system conditions. a The best-case (highest positive impact) outcomes, b The most likely (median and central tendency) outcomes, and c The worst-case (least beneficial impact) outcomes are derived from ~30 simulations of the PGP system’s involvement in the electricity system under the minimize cost and emissions scenarios. Relative changes in energy-only cost, reserve cost, and grid emissions are benchmarked against a state without PGP integration, while changes in the PGP system’s LCHV use a baseline with an unchanged grid configuration. Optimal PGP integration in the power sector favours relaxed unit commitment rules that disregard the fossil fuel generators’ minimum generation requirement.

It is debatable whether altering the existing electricity market rules is practical in fossil fuel-dependent power sectors, where operators focus on minimizing the electricity system’s marginal prices, maintaining grid stability, and preventing the occurrence of stranded generation assets with long-term forward contracts in the electricity market. An alternative and more gradual approach to revising the unit commitment rule would be to reduce the stable generation limit for fossil fuel generation, along with a corresponding reduction in the generators’ minimum uptime. This technical adjustment would increase the frequency of fuel cell dispatch to the reserve market while decreasing output from generators with higher emission factors.

Integrating the PGP system to complement rather than displace carbon capture and sequestration (CCS)-integrated natural gas plants in the reserve market in a grid with a renewable share above 50% can yield a 10% reduction in the electricity system costs and a 5% decrease in the PGP system’s LCHV (Fig. 4b). This favourable outcome occurs because CCS increases the operating costs of natural gas plants, making the fuel cell economically competitive in the long term. The worst-case outcome becomes imminent if innovation in electrolytic hydrogen technology stalls and increased reliance on CCS-integrated natural gas plants reduces the potential for additional emissions reductions from the PGP system: this aligns with earlier findings that the value of electrolytic hydrogen in an emissions-intensive grid decreases when other low-carbon solutions for existing thermal generators are prioritized over deploying renewable energy in parallel with long duration energy storage38,39,40.

The PGP system contributes to reducing marginal costs in an electricity system with overbuilt wind and solar capacities, due to the increased availability of excess renewable energy for near-zero-cost hydrogen production and periods available for energy dispatch to the grid, consistent with earlier findings41. However, overbuilding renewable energy suppresses the power sector’s wholesale electricity prices and hinders the cost-effective integration of fuel cells even in the best-case situation: this is because the reduced incomes from electricity dispatch to a grid with predominantly low wholesale prices are insufficient to offset the initial investment and lifetime operating costs of the integrated PGP system, leading to a substantial increase in the LCHV in most cases (Fig. 4c).

Pricing emission reduction expedites integration in emissions-intensive power sectors

Figure 5 shows the break-even abatement cost (BAC) curve of the PGP system installed by 2030 and 2050 in both grid types. The BAC curve illustrates the CO2 emission reduction impacts of the PGP system along with the associated costs required to induce these emission reduction benefits. The 50 megawatts (50 MW) PGP system in the HighRE grid abates 8.47 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2 over its lifetime and becomes cost-effective to integrate with a BAC of $18 per tCO2 in the time horizon (between 2030 and 2050). In the HighNG grid, the same system abates 0.4 MtCO2 over the same period with $57 per tCO2.

The box width indicates the potential cumulative CO2 reduction over the 20-year lifetime of the PGP system, and the height indicates the corresponding break-even abatement cost (BAC). For PGP systems installed in 2030 and 2050, the abatement durations are 2030 to 2050 and 2050 to 2070, respectively. Scenarios on the lower left have lower BACs; scenarios with wider boxes have a greater GHG reduction. The figure should not be mistaken for a ranking of scenarios, which can be questionable when near-zero BACs are included; the curves serve to present the results, not to rank options for GHG emissions abatement. A cost-optimal ( ~ 800 MW) PGP capacity by 2050 in a fossil fuel-reliant grid requires a BAC of $57 per tCO₂ for the initial 50 MW in 2030 with a 5% growth rate for subsequent installations. Reaching this capacity in either grid type by 2050 demands a 15% installation growth rate (from a baseline of 50 MW in 2030).

Delaying the integration of the same 50 MW system until 2050 increases the BAC to over $1500 per tCO2 in either grid configuration, thus indicating that the opportunity to price the marginal emissions reduction value provided by the PGP system diminishes with increased penetration of renewable energy technologies to the grid under existing power sector unit commitment rules. The delay in reduced emission reduction benefits can be mitigated by modifying the unit commitment rules to discount the stable generation requirement of the natural gas plants. This approach results in a lowered BAC of approximately $38 per tCO2 over the PGP system’s lifetime, whereas a cost-optimal PGP system on the grid would require a BAC of around $65 per tCO2 over the operating lifetime (Supplementary Note 7 shows the cost-optimal system).

With the appropriate break-even abatement cost and expected learning rates of the fuel cell and electrolyzer of 10–20%42, the LCHV in the HighNG and HighRE grids decreases to $4 per kgH2 and $6 per kgH2, respectively, and is sufficient to justify electricity system integration for a risk-averse investor (Fig. 6). A notable BAC of $176 per tCO2 with a futuristic technology learning rate of 39% leads to a near-zero integration cost for the PGP system, though reaching such a high learning rate in the near term (before 2030) may not be feasible without significant global fuel cell demand.

With projected long-term PGP technology learning rates (10-20%), a carbon price above $150 per tCO₂ is central to least-cost risk-averse PGP system integration (at ~$5 per kgH2) in an emission-intensive power sector undergoing a low-carbon transition. With constant learning by-doing and carbon abatement pricing, a near-zero LCHV is realized when the PGP system is integrated to minimize electricity costs and electricity emissions in the high renewable energy (HighRE) and high natural gas (HighNG) grid types, respectively.

Energy discharge cost has a significant impact on uncertainty in the PGP cost-effectiveness

Figure 7a shows that for a representative 50 MW PGP system with a mean LCHV of $9.8 per kgH2 and a BAC of $49 per tCO2, the BAC and LCHV exhibit substantial uncertainty, driven by uncertainty in the energy discharge cost (converting hydrogen to electricity by the fuel cell) and the energy charging cost (producing and storing electrolytic hydrogen). The fuel cell CAPEX accounts for more than 40% of the total variability in both the BAC requirement and LCHV (Fig. 7b, c). Therefore, improving economies of scale, ex-ante demand growth and decreasing the fuel cell’s membrane and separator thickness43 will be crucial to lowering the integration costs for the PGP system. The electrolyzer CAPEX and macroeconomic variables that impact the cost of capital (inflation and interest rate) contribute at least 15% to the remaining variability. The energy discharge cost is highly sensitive to changes in the fuel cell CAPEX and the interest rate (Fig. 7d). Similarly, the electrolyzer CAPEX and interest rate have the most influence on the energy charging cost of the PGP system (Fig. 7e). The noteworthy influence of the components’ capital costs (Supplementary Table 4) and the interest rate indicates that technology learning-by-doing and financing costs will be decisive to the long-term energy cost-effectiveness of the PGP system. The locational installation adjusts for the disparities in system installation costs in a technology-importing region compared to a net producer of the PGP components; thus, appropriate calibration of this factor is essential to avoid underestimating the levelized cost of the PGP system.

a The PGP system’s break-even abatement cost (BAC), levelized cost of hydrogen value (LCHV), energy discharging, and charging cost uncertainties. b-e The impact of varied techno-economic parameters on the PGP system’s LCHV, energy discharging costs, and energy charging costs. Box plots of the uncertainties in panel a indicate the mean (single point), 25th, 75th percentile (box), and 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers). In b–e, the parameters (situated at the right corner of each panel) with comparatively larger Morris mean and standard deviation values indicate that the variation of the effect of the input parameter on the output is conspicuous; parameters with a low Morris mean and high standard deviations are mild/semi-sensitive with moderate impacts on the result; parameters with a low Morris mean and low standard deviations (bottom left corner) have a negligible effect on the outcome (detailed data provided in Supplementary Tables 6-9). An installation factor of 1.15 is applied in our regional (net-importing) context to account for increased overnight capital costs. Net exporters of the PGP system components would have an installation factor of ~1. The regional-specific interest rate and fuel cells’ capital cost impact the PGP system’s BAC and LCHV the most.

It should be noted that improving the electrolyzer conversion efficiency increases the amount of hydrogen produced at unpredicted hours and can be maximized by the fuel cell during periods of competitive dispatch to the grid, leading to a reduction in the BAC requirement to reach the cost-competitive operation of the PGP system for a risk-averse investor, especially in power sectors with substantial renewable energy capacity. Therefore, in addition to the round-trip efficiency, potential improvements in electrolyzer efficiency must be carefully considered in perfect foresight models to avoid underestimating the cost-competitiveness of the PGP system. The operating lifetime of the PGP system constrains reductions in any changes to project duration in the economic analysis. Consequently, uncertainty in the project lifetime has a negligible impact on the long-term cost-effectiveness of the PGP system.

Discussion

This study shows that electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP systems can reduce wholesale electricity costs and grid emissions while remaining profitable for risk-averse investors. Earlier studies, including those by Terlouw et al.44 and Dowling et al.41, provide foundational insights into how renewable penetration and cost sensitivities affect hydrogen integration; however, the studies do not explicitly link the system’s economic competitiveness to the policy-dependent carbon abatement value required to facilitate immediate adoption, especially in fossil fuel-dependent economies. While our levelized cost estimates for the PGP system (USD 900-1000 per MWh) align with United States-focused projections22,23, once multi-value streams (peak electricity supply plus reserve provision) are considered, achieving long-term cost parity for electricity generation with natural gas plants would require an implicit BAC of $57-100 per tCO₂ (Supplementary Table 10). The BAC serves as a critical price-discovery metric, revealing the subsidy level required to reconcile the policymaker’s goal of supporting low-carbon systems with the risk-averse investor’s pursuit of profitable hydrogen conversion and electricity dispatch to the grid.

The study findings also challenge the conventional framing in perfect-foresight models, which suggests that electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP systems only serve as renewable energy enablers for long-term power sector decarbonization. We contend that in regions with existing natural gas-dominated grids, even at a sub-50% renewable energy capacity share, the PGP system can be least-cost-viable by 2030 – provided it operates as a dual-purpose asset offering both long-duration storage and direct fossil displacement in reserve markets, with a BAC threshold of $100 per tCO₂ (Fig. 7a). Our findings shows the need to revisit electricity market rules, specifically by relaxing minimum stable generation limits for thermal units as the PGP system’s capital cost declines, so that the fuel cell (energy discharge component) can deliver both the economic and environmental value to the power sector during periods of demand-supply mismatch.

For the practical implementation of the study outcomes, we suggest that the PGP system be viewed as a carbon mitigation lever in the power sector, with distinct dependencies on economic viability and cost-effectiveness, which rest on the priorities of the policymaker, the risk-averse investor, and the electricity system operator. Secondly, we propose introducing the BAC metric in incentive design. Traditional incentive measures for low-carbon technologies in the power sector often prioritize the levelized cost metric alone, while neglecting the implicit carbon price required to harness their emissions reduction potential. We suggest an incentive design approach in which regulators use both the levelized cost (LCHV) and the BAC as key criteria to select the electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP system with the highest overall value to an emissions-intensive power sector. The latter measure would yield the cost of delivering electricity system cost-reduction value to the operator, and the former metric provides the cost of added emission mitigation to the grid. Drawing on successful low-carbon deployments in fossil fuel-reliant regions45, we propose a competitive auction framework in which the incentive-awarding authority, in collaboration with the electricity system operator, identifies and supports the PGP system that demonstrates the most favourable (lowest) LCHV and BAC conditions. The explicit introduction of the BAC metric ensures that carbon pricing may help to catalyze the value provided by subsequent electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP systems installed in the power sector.

Finally, engendering the use of electrolytic hydrogen in the power sector is often viewed as a trade-off between stringent regulations with high-cost penalties and looser policies that provide limited integration potential. We have shown that appropriately set BAC pricing allows electrolytic hydrogen-based PGP systems to reduce electricity system emissions without raising overall electricity costs. Future studies evaluating the economic viability of the PGP system or similar reversible fuel cells for energy conversion can build on the approach espoused in this study to explore additional region-specific emissions pricing or incentive schemes that may further improve their cost-effective deployment in low-carbon energy transition plans. One promising approach for investigation is to compensate the PGP system with the electricity price differentials induced by the fuel cell under the electricity cost-minimizing and profit-maximizing scenarios introduced in this work.

Methods

Assessment framework

We developed an assessment framework for evaluating the PGP system in the power sector, employing a theoretical approach that soft-links an energy systems model with economic dispatch models to provide insights into the temporal operation of the electricity system, aligning with studies on energy storage value analysis in the power sector6,46. The framework flow schematic provided in Fig. 8 shows how the models are soft-linked with their respective input and output data: LEAP-Canada for economy-wide generation expansion planning, the unit-commitment model (UC-EDwithPGP) for profit-maximizing and economic dispatch optimization of the PGP system in the power sector, and a levelized cost model that determines the PGP system’s LCHV under varied techno-economic uncertainties. The descriptions of each model are further described.

a The LEAP-Canada model used for generation expansion planning, UC-EDwithPGP model for price-taker economic dispatch optimization, and the levelized cost model that incorporates uncertainty and sensitivity analyses. b Connections among the three models to obtain the PGP system’s levelized cost of hydrogen value (LCHV) and break-even abatement cost (BAC) with the corresponding techno-economic uncertainties.

LEAP-Canada model

The power generation technologies for the HighRE and HighNG grids are based on the generation mix determined by the Low Emissions Analysis Platform of Canada (LEAP-Canada) model27. LEAP-Canada is a multi-regional generation expansion modelling framework with calibrated and synthesized data from various research on energy systems47,48,49. Sectoral demands, transmission and distribution losses, and electricity exports and imports influence the yearly electricity consumption. The electricity generation capacities are endogenously determined in LEAP-Canada through linear programming as a function of the firm capacity, projected peak load, planning reserve margin, and technology characteristics. Table 2 lists the key assumptions considered in modelling the two grid types for the case study region and the baseline scenario for the result validation in the LEAP-Canada model. The model outcomes were compared to data on historical electricity demand, capacity, and generation outputs from official government databases50,51,52; the predicted generation capacities fell within the ranges of official sources, with a pooled average difference of approximately 3%.

UC-EDwithPGP model

The unit commitment and economic dispatch model, which we named the UC-EDwithPGP model, determines the hourly wholesale electricity prices using the day-ahead market interactions between different least-cost power generation technologies. The model consisted of an objective function to be minimized or maximized. For the minimize cost objective, a minimum-cost bidding strategy in the electricity market is implemented53. The minimize emissions objective adopts a minimum emission strategy to commit all dispatchable generators in the electricity system. In contrast, the maximize PGP profit objective adopts a maximum revenue generation strategy from electricity sales to the grid by the fuel cell. The model formulation is a mixed-integer linear optimization problem (MILP) solved in the GAMS modelling platform (https://www.gams.com) with the CPLEX solver. The UC-EDwithPGP model uses inputs from each dispatchable generator’s heat rate (gigajoule per MWh), ramp rates, minimum power levels, minimum up/down times, startup/shutdown states, startup/shutdown costs, capacity factors, and availability factors. The unit commitment characteristics for the dispatchable generator, such as the minimum operating power, ramp rate capabilities, heat rates, and minimum up/down times, were adopted from de Sisternes et al54. The startup and shutdown costs for the dispatchable generators were calculated using the equations for developing country-level electricity models by considering the relationship between the total nameplate capacity of the power plant, standard unit sizes, and generator characteristics55.

The derivations of the objective functions and constraints for the UC-EDwithPGP model are provided in Supplementary Note 1. The electricity dispatch from the PGP system (if needed by the electricity system) only uses the day-ahead hourly price as the proxy for decision-making. Renewable energy generation systems use historical weather data to determine the likelihood of hydrogen production with curtailed renewable energy. We note that hydrogen production and energy dispatch to the grid do not occur simultaneously, as indicated by a binary constraint added to the model, in line with the ideal configurations of existing integrated PGP systems.

For hydrogen-to-power conversion, we considered a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) instead of an alkaline fuel cell (AFC), a solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC), or a molten carbonate fuel cell (MCFC). The compatibility of an AFC to severe variability in renewable energy supply limits its application in this study, as intermittent electricity supply shortens an AFC’s functional lifespan by almost 50%56. PEMFCs also perform better than AFCs when grid dispatch requirements are highly unpredictable25. Though unique in terms of the lower demand for platinum group metals in the design and ability to both charge and discharge simultaneously, large-scale (non-kilowatt-scale) SOFCs are mostly confined to pilot projects because of issues related to material durability at elevated temperatures57,58. We also favoured the PEMFC over MCFCs because of the quicker response time to grid demand (especially in the reserve market) and the reduced thermal degradation it provides. The MCFC experiences material corrosion challenges due to its high-temperature requirements, which limit its viability for long-duration energy dispatch operations in the power sector compared to PEMFCs59. The cost of PEMFCs has also declined by ~13.5% with every doubling of global installed capacity since 2003; efficiency improvements drive the decline amid an increase in global demand60.

Quantifying the levelized cost of hydrogen value

The levelized cost of hydrogen value (LCHV, denoted in $ per kgH2) aggregates all discounted costs of the PGP system over the lifetime, less the income realized after delivering electricity to the grid. The total monetary value is then divided by the amount of hydrogen produced within the model horizon:

The discounted lifetime cost and income are described in Eq. (2). The parameters \({FOPEX}\), \({CAPEX}\), \({LIEX}\), and \({{energy}}_{{costs}}\) represent the fixed operating, capital, labour, and energy-related costs, respectively.

The capital costs are denominated in $ per kilowatt. The subscript \(e\) represents the balance of plant equipment; thus, the total cost includes the cost of the electrolyzer, fuel cell, power electronics, controller, and compressor. The water cost for electrolysis (\({{H}_{2}}_{{watercost}}\)) and the cost of hydrogen storage (\({{H}_{2}}_{{storagecost}}\)) throughout the year are also included in estimating the discounted costs. The variable \({Ce}\) is the location cost escalation factor61, and \({{CRF}}_{e}\) and \({{RCRF}}_{e}\) are the capital recovery factors of the investment cost and replacement cost discounted over the project lifetime (\(N\)):

The real interest rate is given by \({ir}=([\frac{1+i{r}_{{norm}}}{1+\inf }]-1)\), with inf and \(i{r}_{{norm}}\) representing the inflation and nominal interest rates, respectively. \({Rp}\) is the replacement period of the equipment (particularly the fuel cell and electrolyzer systems) over the project lifetime62. The annualized replacement cost is adjusted for multiple replacement periods using the expression \(|\left(\frac{N}{{Rp}}\right)|\), which reflects the absolute number of times the stack of the energy conversion system is changed. The fixed cost of the system is defined by \({FOPEX}=({{\mathrm{O\&M}}}_{{costfactor}}\times {{CAPEX}}_{e})\).

In the minimize cost and emissions scenarios, the mean output of the fuel cell is between 45 and 70% of the rated capacity. It reaches 90% in the maximized PGP profit scenario, leading to the replacement of the stack earlier than the planned lifetime due to excessive cycling (exceeding 1000 times per year and over 8000 cycles over its lifetime). The impact of this excessive cycling is accounted for in Eq. (4). Therefore, assuming the replacement period is 7 years (less than the potential 12-year lifetime17) and the stack is replaced twice, \(R{p}_{1}=8\) and \(R{p}_{2}=16\). This approach ensured that we did not underestimate the LCHV, especially for the profit maximization case.

Quantifying the hydrogen storage cost

The hydrogen storage cost was calculated using the Hydrogen Delivery Scenario Analysis Model (HDSAM)63. HDSAM, developed by the Argonne National Laboratory, provides a comprehensive toolkit for simulating a geologic hydrogen storage system based on fundamental engineering principles and calculating the associated costs. Ten-day hydrogen storage is assumed to account for plant outages and, to minimize hydrogen supply security constraints, underground salt cavern hydrogen storage is adopted in this study because of its low technology development risk, immediate feasibility, and minimal impact on safety for large-scale hydrogen storage (compared to other potential storage options, such as above-ground steel tanks)64.

The potential for underground hydrogen storage is abundant in Alberta’s sedimentary basins, which contain deep saline aquifers that are favourable for underground hydrogen storage65,66. Spatial and geotechnical assessments indicate that Alberta’s sedimentary basins are located near areas with high renewable energy potential67, with the potential to colocate the PGP systems in locations suitable for large-scale underground hydrogen storage. We assumed a single large-scale cavern is used at the system dispatch level, with operating pressures ranging from 60 to 150 bar68. The maximum hydrogen production rate is 535,000 tonnes per day to maintain operating storage. The labour cost is increased by 15% in HDSAM to reflect Alberta-specific labour characteristics, and an average of ~$0.1 per kgH2 was realized and used as the base cost of underground hydrogen storage in this study.

Quantifying learning-by-doing impact

The effect of learning rates on the LCHV is investigated using Wright’s Law69. A forward-looking approach is applied to the framework for an initial PGP system capability (i.e., 50 MW in 2030) to the maximum incremental capacity achievable for the HighRE and HighNG grids by 2050. The revised capital cost of each incremental electrolyzer and fuel cell (\({{{\rm{CAPEX}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}}}\)) is expressed below:

\({{{\rm{CAPEX}}}}_{{{\rm{e}}},{{\rm{initial}}}}\) represents the capital cost of the initial installation, and \(Y\) is the ratio of the initial PGP system capacity to the cumulative installed capacity on the grid (or normalization factor). The experience rate (b) is estimated and the learning rate range chosen is based on the trajectory of comparable low-carbon technologies42:

Quantifying sensitivity and uncertainty

The LCHV was calculated using the most likely techno-economic parameters. Economic parameters, such as interest rates, inflation, and installation costs, may change over time. Furthermore, the CAPEX and lifetime estimates in the literature differ and may diverge from the target value used in this study. The levelized cost model was paired with the Regression, Uncertainty, and Sensitivity Tool (RUST)33 to assess the techno-economic parameters that have a significant impact on the LCHV of the PGP system (Supplementary Note 6). Parameters like interest rates, inflation, capital costs, learning rates, system lifetime, installed capacity, and efficiencies vary based on their probable distribution type. Morris global sensitivity and Sobol uncertainty analyses were applied to assess the interdependence and interactions between the input parameters and deviations from the expected outcome34,35 (Supplementary Table 5). The absolute value does not significantly impact the percentage sensitivity impact of each techno-economic parameter, but rather by the potential difference between the minimum and maximum realizable values or the distribution type.

Quantifying the break-even GHG abatement cost

The PGP system’s break-even GHG abatement cost (BAC) is calculated with Eq. (7). The BAC is estimated by dividing the numerator in the LCHV by the emissions abated in the electricity system by the PGP system over the lifetime.

The difference in the emissions with and without the PGP system is represented below:

The definition adopted for the BAC is associated with GHG emission reduction (\({{CO}}_{2{abated}}\)) engendered by introducing the PGP system in the energy system (\({{Emissions}}_{{withPGP}}\)) compared to the case without it (\({{Emissions}}_{{noPGP}}\)). This approach compares two decisions and alternatives, and better captures the objective of this study to assess the carbon pricing required to achieve break-even total cost (where revenues minus cost equal zero) for the PGP system relative to the total change in emissions that results from progressing from an electricity system without electrolytic hydrogen adoption to an alternative case where electrolytic hydrogen is adopted under specified conditions in the electricity system. This BAC concept deviates from the more commonly used marginal abatement cost, which typically represents the cost of each additional unit of emissions abatement.

The BAC was calculated for the initial and cost-optimal PGP systems under the minimize cost and minimize emissions scenarios. Although the maximum PGP profit scenario provides a distinct perspective for justifying the involvement of the PGP system in the electricity system, its implementation may be impractical for the system operator; hence, it is excluded from the representation of learning rate effects.

Limitations

Finally, we note some limitations of this work. The PGP system modelled in this study does not compete with short-duration storage technologies. Decreasing the storage duration of the PGP system to less than 24 hours would increase the levelized cost of hydrogen value (Supplementary Fig. 4), making it uneconomical to operate with batteries for primary reserve provision70. This work did not consider the non-direct GHG footprint of the PGP system. An earlier study estimated the GHG footprint of green hydrogen production to be ~0.69 kgCO2 per kgH271. Still, the cradle-to-gate emissions footprint, including storage and energy conversion, has not been thoroughly investigated; this remains an important area for future research to inform better decision-making.

Another limitation of this study is that the profit maximization objective introduced for the risk-averse investor relies on a consistent hourly (or sub-hourly) optimization of the PGP system’s participation in the electricity system to achieve the BAC and LCHV with greater fidelity. Traditional macro-energy system models – often with perfect foresight and coarse time resolution – may not support this level of granularity, as solving the associated mixed-integer problem requires significant computational resources and time to achieve a zero-tolerance gap solution. To address this shortcoming, we recommend using a time-adjusted interest rate for annualized cost estimates under partial foresight or decomposed periods (see Supplementary Note 5), which ensures that both short-term dispatch revenues and emissions benefits are accounted for in the techno-economic analysis calculations.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, and additional information for reproducing the study analysis and outcomes is in the Supplementary Information file.

Code availability

The mathematical formulations of the UC-EDwithPGP model (as written in GAMS) are provided in the Supplementary Information file. The codes supporting the development of the LEAP-Canada and the Regression, Uncertainty, and Sensitivity Tool (RUST) models are proprietary. To request access, please contact the corresponding author, A.K. (amit.kumar@ualberta.ca). Requests will be reviewed and responded to.

References

Nikolaidis, P. & Poullikkas, A. A comparative overview of hydrogen production processes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 67, 597–611 (2017).

Hanley, E. S., Deane, J. P. & Gallachóir, B. P. Ó The role of hydrogen in low carbon energy futures–A review of existing perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 3027–3045 (2018).

Glenk, G. Reversible fuel cells: An economic analysis. SSRN Electron. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3567167 (2020).

International Renewable Energy Agency. Hydrogen: a renewable energy perspective. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Sep/IRENA_Hydrogen_2019.pdf (2019).

Díaz-González, F., Sumper, A., Gomis-Bellmunt, O. & Villafáfila-Robles, R. A review of energy storage technologies for wind power applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 2154–2171 (2012).

Hunter, C. A. et al. Techno-economic analysis of long-duration energy storage and flexible power generation technologies to support high-variable renewable energy grids. Joule 5, 2077–2101 (2021).

Marocco, P. et al. A study of the techno-economic feasibility of H2-based energy storage systems in remote areas. Energy Convers. Manag. 211, 112768 (2020).

Dowling, J. A. et al. Role of long-duration energy storage in variable renewable electricity systems. Joule 4, 1907–1928 (2020).

Blanco, H. & Faaij, A. A review at the role of storage in energy systems with a focus on power to gas and long-term storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 1049–1086 (2018).

Braff, W. A., Mueller, J. M. & Trancik, J. E. Value of storage technologies for wind and solar energy. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 964–969 (2016).

Guerra, O. J., Eichman, J. & Denholm, P. Optimal energy storage portfolio for high and ultrahigh carbon-free and renewable power systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5132–5146 (2021).

Sepulveda, N. A., Jenkins, J. D., de Sisternes, F. J. & Lester, R. K. The role of firm low-carbon electricity resources in deep decarbonization of power generation. Joule 2, 2403–2420 (2018).

Glenk, G. & Reichelstein, S. Reversible power-to-gas systems for energy conversion and storage. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–10 (2022).

González, P., Villar, J., Díaz, C. A. & Campos, F. A. Joint energy and reserve markets: Current implementations and modeling trends. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 109, 101–111 (2014).

Victoria, M., Zhu, K., Brown, T., Andresen, G. B. & Greiner, M. The role of storage technologies throughout the decarbonisation of the sector-coupled European energy system. Energy Convers. Manag. 201, 111977 (2019).

Levi, P. J. et al. Macro-energy systems: toward a new discipline. Joule 3, 2282–2286 (2019).

McDonagh, S., Ahmed, S., Desmond, C. & Murphy, J. D. Hydrogen from offshore wind: Investor perspective on the profitability of a hybrid system including for curtailment. Appl. Energy 265, 114732 (2020).

Government of Alberta. Alberta hydrogen roadmap. https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/d7749512-25dc-43a5-86f1-e8b5aaec7db4/resource/538a7827-9d13-4b06-9d1d-d52b851c8a2a/download/energy-alberta-hydrogen-roadmap-2021.pdf (2021).

Natural Resources Canada. Hydrogen strategy for Canada- Seizing the opportunities for hydrogen. https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/sites/www.nrcan.gc.ca/files/environment/hydrogen/NRCan_Hydrogen-Strategy-Canada-na-en-v3.pdf (2020).

Tarkowski, R. Underground hydrogen storage: Characteristics and prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 105, 86–94 (2019).

International Energy Agency (IEA). The future of hydrogen: Seizing today’s opportunities. Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-hydrogen (2019).

Schmidt, O., Melchior, S., Hawkes, A. & Staffell, I. Projecting the Future Levelized Cost of Electricity Storage Technologies. Joule 3, 81–100 (2019).

Guerra, O. J. et al. The value of seasonal energy storage technologies for the integration of wind and solar power. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 1909–1922 (2020).

Di Lullo, G. et al. Large-scale long-distance land-based hydrogen transportation systems: A comparative techno-economic and greenhouse gas emission assessment. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.08.131 (2022).

Ayodele, T. R. & Munda, J. L. Potential and economic viability of green hydrogen production by water electrolysis using wind energy resources in South Africa. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 44, 17669–17687 (2019).

Deane, J. P. et al. Soft-linking of a power systems model to an energy systems model. Energy 42, 303–312 (2012).

Davis, M., Moronkeji, A., Ahiduzzaman, M. & Kumar, A. Assessment of renewable energy transition pathways for a fossil fuel-dependent electricity-producing jurisdiction. Energy Sustain. Dev. 59, 243–261 (2020).

Sepulveda, N. A., Jenkins, J. D., Edington, A., Mallapragada, D. S. & Lester, R. K. The design space for long-duration energy storage in decarbonized power systems. Nat. Energy vol. 6 506–516 at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-021-00796-8 (2021).

Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO). Current and historical market data and reports. https://www.aeso.ca/market/market-and-system-reporting/data-requests/ (2021).

Alberta Electric System Operator (AESO). Most Severe Single Contingency (MSSC). https://www.aeso.ca/market/market-updates/2020/mssc-reduction/ (2020).

AESO. Alberta reliability standard contingency reserve (BAL-002-WECC-AB1-2). https://www.aeso.ca/rules-standards-and-tariff/alberta-reliability-standards/bal-002-wecc-contingency-reserves/ (2020).

García-Martos, C., Rodríguez, J. & Sánchez, M. J. Modelling and forecasting fossil fuels, CO2 and electricity prices and their volatilities. Appl. Energy 101, 363–375 (2013).

Di Lullo, G., Gemechu, E., Oni, A. O. & Kumar, A. Extending sensitivity analysis using regression to effectively disseminate life cycle assessment results. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 25, 222–239 (2020).

Morris, M. D. Factorial sampling plans for preliminary computational experiments. Technometrics 33, 161–174 (1991).

Sobol, I. M. Sensitivity estimates for non-linear mathematical models. Math. Model. Comput. Exp. 1, 407–414 (1993).

Glenk, G. & Reichelstein, S. Economics of converting renewable power to hydrogen. Nat. Energy 4, 216–222 (2019).

Zeyen, E., Riepin, I. & Brown, T. Temporal regulation of renewable supply for electrolytic hydrogen. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024034 (2024).

Sepulveda, N. A., Jenkins, J. D., Edington, A., Mallapragada, D. S. & Lester, R. K. The design space for long-duration energy storage in decarbonized power systems. Nat. Energy 6, 506–516 (2021).

Levin, T. et al. Energy storage solutions to decarbonize electricity through enhanced capacity expansion modelling. Nat. Energy 8, 1199–1208 (2023).

Jenkins, J. D. & Sepulveda, N. A. Long-duration energy storage: A blueprint for research and innovation. Joule 5, 2241–2246 (2021).

Dowling, J. A. et al. Opportunities and constraints of hydrogen energy storage systems. Environ. Res. Energy 1, 035004 (2024).

Glenk, G., Meier, R. & Reichelstein, S. Cost dynamics of clean energy technologies. Schmalenbach J. Bus. Res. 73, 179–206 (2021).

Kempler, P. A., Slack, J. J. & Baker, A. M. Research priorities for seasonal energy storage using electrolyzers and fuel cells. Joule at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2021.12.020 (2022).

Terlouw, T., Rosa, L., Bauer, C. & McKenna, R. Future hydrogen economies imply environmental trade-offs and a supply-demand mismatch. Nat. Commun. 15, 7043 (2024).

Battke, B. & Schmidt, T. S. Cost-efficient demand-pull policies for multi-purpose technologies – The case of stationary electricity storage. Appl. Energy 155, 334–348 (2015).

Welsch, M. et al. Incorporating flexibility requirements into long-term energy system models-A case study on high levels of renewable electricity penetration in Ireland q. Appl. Energy 135, 600–615 (2014).

Davis, M., Okunlola, A., Di Lullo, G., Giwa, T. & Kumar, A. Greenhouse gas reduction potential and cost-effectiveness of economy-wide hydrogen-natural gas blending for energy end uses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 171, 112962 (2023).

Davis, M., Ahiduzzaman, M. & Kumar, A. How to model a complex national energy system? Developing an integrated energy systems framework for long-term energy and emissions analysis. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 17, 23–58 (2018).

Davis, M., Ahiduzzaman, M. & Kumar, A. How will Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions change by 2050? A disaggregated analysis of past and future greenhouse gas emissions using bottom-up energy modelling and Sankey diagrams. Appl. Energy 220, 754–786 (2018).

Alberta Electric System Operator. Net-zero emissions pathways report. https://www.aeso.ca/assets/Uploads/net-zero/AESO-Net-Zero-Emissions-Pathways-Report.pdf (2022).

Canada Energy Regulator. Canada’s Energy Future 2020: Energy supply and demand projections to 2050. https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/canada-energy-future/2020/index.html (2020).

Alberta Utilities Commission. Annual electricity data. http://www.auc.ab.ca/pages/annual-electricity-data.aspx (2023).

Arroyo, J. M. & Conejo, A. J. Optimal response of a thermal unit to an electricity spot market. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 15, 1098–1104 (2000).

de Sisternes, F. J., Jenkins, J. D. & Botterud, A. The value of energy storage in decarbonizing the electricity sector. Appl. Energy 175, 368–379 at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.05.014 (2016).

Brinkerink, M., Gallachóir, B. & Deane, P. Building and calibrating a country-level detailed global electricity model based on public data. Energy Strateg. Rev. 33, 100592 (2021).

Ulleberg, Ø, Nakken, T. & Eté, A. The wind/hydrogen demonstration system at Utsira in Norway: Evaluation of system performance using operational data and updated hydrogen energy system modeling tools. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35, 1841–1852 (2010).

Rashidi, S. et al. Progress and challenges on the thermal management of electrochemical energy conversion and storage technologies: Fuel cells, electrolysers, and supercapacitors. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 88, 100966 (2022).

U.S. Department of Energy. Hydrogen shot: water electrolysis technology assessment. Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technol. Off. https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-shot (2022).

Tomczyk, P. MCFC versus other fuel cells—characteristics, technologies and prospects. J. Power Sources 160, 858–862 (2006).

Glenk, G., Holler, P. & Reichelstein, S. Advances in power-to-gas technologies: cost and conversion efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EE01208E (2023).

Olateju, B., Kumar, A. & Secanell, M. A techno-economic assessment of large scale wind-hydrogen production with energy storage in Western Canada. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 41, 8755–8776 (2016).

Rahman, M. M., Oni, A. O., Gemechu, E. & Kumar, A. The development of techno-economic models for the assessment of utility-scale electro-chemical battery storage systems. Appl. Energy 283, 116343 (2021).

U.S. Department of Energy. Hydrogen Delivery Scenario Analysis Model (HDSAM). https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/h2a_delivery.html (2020).

Quarton, C. J. & Samsatli, S. Should we inject hydrogen into gas grids? Practicalities and whole-system value chain optimisation. Appl. Energy 275, 5–8 (2020).

Lemieux, A., Shkarupin, A. & Sharp, K. Geologic feasibility of underground hydrogen storage in Canada. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45, 32243–32259 (2020).

Bachu, S. & Stewart, S. Geological sequestration of anthropogenic carbon dioxide in the Western Canada sedimentary basin: suitability analysis. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 41, 32–40 (2002).

Elizabeth, D. & Sonak, P. Canada’s renewable energy project map. Website https://www.futureenergysystems.ca/resources/renewable-energy-projects-canada# (2020).

Bünger, U., Michalski, J., Crotogino, F. & Kruck, O. Large-scale underground storage of hydrogen for the grid integration of renewable energy and other applications. Compend. Hydrog. Energy 133–163 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-78242-364-5.00007-5 (2016).

Wright, T. P. Factors affecting the cost of airplanes. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 3, 122–128 (1936).

Baumgarte, F., Glenk, G. & Rieger, A. Business models and profitability of energy storage. iScience 23, 101554 (2020).

Gemechu, E. D. & Kumar, A. The environmental performance of hydrogen production pathways based on renewable sources. Renewable-Energy-Driven Futur. 375–406 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820539-6.00012-1 (2021).

Alberta Electric System Operator. AESO 2021 Long-term outlook. https://www.aeso.ca/grid/forecasting/ (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the NSERC Alliance Grant Programme on Integrated Assessment of Energy Systems (RES0062884) and the Cenovus Energy Endowed Chair Programme in Environmental Engineering, which funded the research project. The authors acknowledge funding from Cenovus Energy Inc. (RES0063250), Suncor Energy Inc. (RES0063251), Alberta Innovates (RES0063252), Natural Resources Canada (RES0062887), Alberta Energy and Minerals (RES0063253), and Environment and Climate Change Canada (RES0063254). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Programme (CRC-2021-00530). This funding was provided in support of the Canada Research Chair in Assessment of Energy Systems (Tier-1). This research was partially supported by funding from the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Engineering (RES0064108). The authors thank Ms. Astrid Blodgett for editing this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research Conceptualization, A.O. and A.K.; Study Design-Methods, A.O. and M.D.; Software and Modelling, A.O. (UC-EDwithPGP and levelized cost models), M.D. and A.K. (LEAP-Canada model), A.K. (RUST); Result Analysis-Visualization, A.O. and M.D.; Original Draft, A.O.; Writing-Review, A.O., M.D., and A.K.; Supervision and Funding Acquisition, A.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jacqueline Dowling, Yao Zhao, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okunlola, A., Davis, M. & Kumar, A. Assessment of carbon-abatement pricing to maximize the value of electrolytic hydrogen in emissions-intensive power sectors. Nat Commun 16, 8039 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62952-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62952-y