Abstract

Stabilizing the RSV F protein in its prefusion conformation is crucial for effective vaccine development but has remained a significant challenge. Traditional stabilization methods, such as disulfide bonds and cavity-filling mutations, have been labor-intensive and have often resulted in suboptimal expression levels. Here, we report the design of an RSV prefusion F (preF) antigen using a proline-scanning strategy, incorporating seven proline substitutions to achieve stabilization. The resulting variant, preF7P, is structurally and biochemically validated to maintain the correct prefusion state. PreF7P demonstrates superior immunogenicity with a 1.8-fold increase in neutralizing antibody titers when compared to DS-cav2, and provides protection from clinical disease against both RSV A and B strains in female murine and female cotton rat models. In clinical development, preF7P exhibits high expression levels (~10 g/L) in clinical-grade CHO cells. The clinical-grade vaccine elicits robust immunogenic responses across female mice, female SD rats, and both male and female cynomolgus macaques, significantly boosting RSV pre-infection neutralizing antibody titers, and providing sustained protection for at least six months in female mice. This proline-scanning strategy offers a streamlined approach for stabilizing class I fusion proteins, potentially accelerating the development of vaccines for other pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of bronchiolitis and pneumonia in infants and young children, and is responsible for ~ 3.6 million pediatric hospitalizations worldwide every year1,2,3,4. In older adults, RSV is responsible for comparable levels of morbidity and mortality as influenza viruses5,6,7,8. The F protein of RSV represents the primary antigen target for vaccine development2,3,9,10. As a class I fusion glycoprotein, F mediates the fusion of RSV and host cell membranes through irreversible conformational changes from the labile prefusion state to the stable postfusion state11,12,13,14. The prefusion F (preF) presents six antigenic sites, labeled Ø (zero) to V15,16,17. The Ø and V sites are displayed only on the preF surface, whereas antigenic sites I to IV are shared by preF and the postfusion F (postF)15,18. PreF-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been reported to be substantially more potent than mAbs targeting other antigenic sites19,20,21,22, and to contribute to the majority of the human RSV-neutralizing response following natural infection5,23. However, owing to its instability, the preF protein is prone to prematurely refolding into its more stable postfusion conformation in solution5. Prefusion stabilization is therefore critical to producing preF reliably in mammalian cells and thus developing effective subunit vaccines5,24,25,26.

Enhanced Respiratory Disease (ERD) remains a critical concern in RSV vaccine development, particularly for RSV-naïve infants. Historical formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccine trials in the 1960s revealed that vaccinated infants experienced paradoxically severe disease upon natural RSV infection, leading to increased hospitalizations and tragically, the deaths of two vaccinated infants27. Multiple mechanisms potentially contribute to ERD, including suboptimal neutralizing antibody responses, formation of low-avidity antibodies, skewing toward Th2-dominant immune responses, and pulmonary immune complex deposition with subsequent complement activation28. In contrast to FI-RSV, where the critical prefusion F protein conformation was lost during inactivation29, vaccine candidates incorporating stabilized preF antigens may reduce ERD risk by promoting the generation of functionally protective antibodies.

Several common strategies to stabilize class I fusion glycoproteins such as preF include: 1) the introduction of disulfide bonds to tether regions that undergo substantial conformational changes to others that do not5,24,30,31; 2) the introduction of non-polar amino acids to fill interior cavities that might otherwise be prone to moving during conformational rearrangement5,24,30,32; 3) the introduction of charge mutations to decrease unfavorable electrostatic repulsions or increase electrostatic interactions with proximal residues24; and 4) the introduction of proline residues in the turn located between the central helix and the first heptad repeat (HR1), to prevent the formation of a single elongated α helix in the postF protein25,33,34. These strategies have led to the generation of several stable preF proteins such as DS-cav15,35,36, 84730, and DS-cav224, all of which exhibit more potent immunogenicity compared to postF. However, those variants have all exhibited modest expression yields with relatively high levels of aggregates24, making mass production challenging and hampering the development of subunit vaccines. The aforementioned stabilization strategies are also heavily dependent on high-resolution structures to guide the positioning of stabilizing changes, and the iterative engineering process is typically quite laborious and time-consuming37.

Hsieh et al. used all of the aforementioned stabilization strategies to design prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins38. Through rigorous testing of various combinations of beneficial substitutions based on different stabilization strategies, a variant with six proline substitutions eventually exhibited the highest levels of expression and heat stability38. Proline substitutions at flexible loops or at the N termini of helices can stabilize them using the restricted backbone dihedral angles of proline residues, and thus effectively stabilizing protein structures37,38. This work involving the prefusion SARS-CoV-2 spike protein inspired us to hypothesize that it would be feasible to design a high-expression, prefusion-stabilized class I fusion protein using the proline substitution approach.

In this study, we proposed a proline-scanning strategy for every flexible loop located before an α helix within the RSV F protein, aiming to rationally design prefusion-stabilized RSV F antigen. Using this approach, we identified multiple beneficial proline substitutions. Combining seven proline substitutions allowed us to generate a high-yield, prefusion-stabilized RSV F antigen, termed preF7P. This variant achieved expression levels exceeding 10 g/L in clinical-grade, stable Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell lines, demonstrated robust immunogenicity, and provided sustained protection for at least six months in murine models. The scalability and stability of preF7P underscore its potential as a viable candidate to meet the global demand for an effective RSV vaccine.

Results

Identification of multiple prefusion-stabilizing proline substitutions in RSV F via proline-scanning

To develop a prefusion-stabilized RSV F protein, we established a systematic proline-scanning strategy targeting loops preceding α helices. We engineered a recombinant RSV F ectodomain (residues 26–513) containing an N-terminal signal peptide and a C-terminal T4 fibritin trimerization domain. A (GGGGS)3 linker was introduced between the F1 and F2 subunits to functionally mimic the native long loop between F1 and F2 subunits (residues 100–135) while providing sufficient spatial separation for independent folding of each subunit. (Fig. 1a).

a Schematic of the RSV antigen design. The antigen includes an F ectodomain from aa 26–513 that is colored in gray, a linker of (GGGGS)3 to fuse the C terminus of F2 at residue 99 to the N terminus of F1 at residue 136, and a T4 fibritin trimerization domain that is termed as foldon, shown in yellow. b Proline-scanning regions in the RSV F structure (PDB ID: 4JHW). Nine loops from L0–9 (shown in different colors), located before α helices, were subjected to proline scanning. c PreF vs postF expression levels of variants harboring one or two proline substitutions in the L0 loop. At 72 h post transfection, the cell culture supernatant was tested for binding to prefusion-specific AM14 and postfusion-specific 4D7, via ELISA. d PreF expression levels of F1P-based variants with one or two additional proline substitutions in the L1–8 loop. At 72 h post-transfection, a 1:80 dilution of the cell culture supernatant was tested for binding to prefusion-specific AM14 via ELISA. For c and d Data are presented as mean values +/- standard errors of mean (SEM) from three independent experiments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Structural analysis identified nine loops (L0-L8) preceding α helices as potential targets11 (Fig. 1b). Among these, the L0 loop between α4 and α5 helices was of particular interest, as it undergoes a dramatic conformational change during the prefusion-to-postfusion transition, where the α4 helix rotates ~180° to form a single elongated α helix with L0 and α5. Initial screening of the L0 loop identified S215P as an effective stabilizing mutation that maintained the prefusion conformation. Additional proline substitutions in L0 (Q210P, I214P, or N216P) combined with S215P showed similar prefusion-stabilizing effects. However, all these variants showed lower preF expression compared to DS-cav2 (Fig. 1c). Based on these results, we selected two variants for further optimization: F1P (containing S215P) and F2P (containing S215P-N216P) (Supplementary table 1), with the latter incorporating an additional proline substitution for potential enhanced prefusion-stabilizing effects. Subsequent proline scanning through loops L1-L8 using F1P as template identified seven additional beneficial substitutions (N67P, L138P, G139P, L141P, E161P, Q279P, and S377P) that enhanced preF expression (Figs. 1d, 2a).

a Locations of identified beneficial proline substitutions from proline scanning of the L0–8 loops. The RSV prefusion F structure was generated based on PDB ID: 4JHW. b PreF (left) and postF (right) expression levels of variants with combined proline substitutions. At 72 h post-transfection, preF concentration in the cell culture supernatant was assayed via sandwich ELISA using prefusion-specific AM14 as coating mAbs and DS-cav2, to plot a standard curve. The binding activity of the cell culture supernatant to postfusion-specific 4D7 was determined using ELISA. Data are presented as mean values +/- SEM from three independent experiments. c Representative of gel-filtration chromatograms of F1-2P-based variants with additional proline substitutions. d Representative of gel-filtration chromatograms of F1-2P-based variants with additional proline substitutions. For c and d Gel-filtration profile for each protein, representative of at least two experiments, was assessed on a Superose 6 10/300 GL SEC column. e–h Groups of BALB/c mice (n = 9) were immunized twice with placebo or F variants adjuvanted with Alum plus CpG1826 at a three-week interval. Serum samples collected at five weeks post initial vaccination were assessed for neutralizing antibody titers against RSV Long strain (e) and RSV BA9 strain (f) by live virus microneutralization assays. At five weeks post initial vaccination, the mice were challenged with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV A (long strain) administered via the i.n. route. Lung samples obtained at 5 dpi were subjected to virus titration by PFU assays (g) and RT-PCR (h). i New groups of BALB/c mice (n = 8) were immunized with placebo, preF7P, or preF6P that was adjuvanted with Alum plus CpG1826, at weeks 0 and 3. At week 5, the mice were challenged with 1 × 105 PFU of the RSV BA9 strain. Lung samples obtained at 5 dpi were subjected to virus titration by RT-PCR. j, k BALB/c mice (n = 10 per group) received two immunizations of placebo, DS-cav1, preF7P, or preF6P at either 2 μg or 12 μg doses, adjuvanted with Alum plus CpG1826 at a three-week interval. Serum neutralizing antibody titers against RSV Long strain (j) and RSV BA9 strain (k) were measured at five weeks post-initial vaccination by live virus microneutralization assays. For e–k, data are presented as mean values +/- SEM. P-values were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n.s. P > 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Combination of beneficial proline substitutions

We systematically tested beneficial mutation combinations, beginning with adjacent positions L138P-G139P in the L2 loop (F1P-2P) (Supplementary Table 1). This combination dramatically improved preF expression from 2.0 μg/mL (F1P) to 49.1 μg/mL, though with slightly increased binding to postfusion-specific mAb 4D739 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1). F1P-2P demonstrated strong binding to a panel of prefusion-specific antibodies (D2511, AM2240, AM1441, and hRSV9042) (Supplementary Fig. 2). A parallel variant based on F2P (F2P-2P) showed similar properties (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Further optimization of F1P-2P and F2P-2P involved systematic incorporation of additional beneficial proline substitutions, guided by two criteria: (1) positions showing individual benefits in prefusion stability and expression, and (2) spatial distribution across different flexible loops for potential additive stabilizing effects. For instance, N67P was selected for its beneficial effects in the L1 loop, while Q279P was chosen for its prefusion-stabilizing properties in the L6 loop. The F1P-2P-based variants harboring three or four additional proline substitutions achieved even higher preF expression (56.4-76.3 μg/mL), significantly exceeding DS-cav2 (5.7 μg/mL), while maintaining postfusion-specific mAb 4D7 reactivity comparable to DS-cav2 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Figs. 4, 5). Similarly, several F2P-2P-based variants, including F2P-2P-Q279P, F2P-2P-L141P-Q279P, and F2P-2P-N67P-Q279P, demonstrated enhanced preF expression coupled with reduced 4D7 recognition (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Biophysical characterization demonstrated superior properties of our proline-stabilized variants. Unlike DS-cav2 which showed significant aggregation, all variants expressed as homogeneous trimers with molecular weights of 168–178 kDa (Fig. 2c, d). The F1P-2P-based variants exhibited high binding affinity (KD ≤ 0.2 nM) to prefusion-specific antibodies targeting distinct epitopes: AM14 (quaternary-dependent), AM22 (site Ø), and hRSV90 (site V). The F2P-2P-based variants showed reduced AM22 binding affinity, likely due to the double proline substitutions decreasing the L0 loop flexibility required for site Ø-specific mAb binding, yet maintained strong binding to AM14 and hRSV90 (KDs ≤ 0.1 nM), confirming their prefusion conformation. All variants showed consistent thermal stability with melting temperatures of 58.2-59.5 °C. Most variants maintained stability after two weeks at 25 °C, with only three constructs (F1P-2P-L141P-Q279P-S377P, F2P-2P-Q279P-S377P, and F2P-2P-N67P-L141P-Q279P) showing minor decreases in preF concentrations (Supplementary Table 2).

Immunogenicity and efficacy investigations of F variants with multiple proline substitutions in mice

We next measured the immunogenicity of those engineered antigens harboring multiple-proline substitutions by immunizing BALB/c mice at week 0 and 3. Serum samples obtained at week 5 were evaluated for antigen-specific IgG and neutralizing antibody titers using ELISA and live-virus microneutralization assay. We observed that, similarly to DS-cav2, all of our variants elicited high antigen-specific IgG levels with titers reaching up to > 106 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Microneutralization assays against RSV A (Long strain) showed that no neutralizing antibodies were detected in placebo sera, whereas all RSV vaccine candidates induced high 50% neutralizing antibody titers (NT50) of > 1000 (Fig. 2e). Two lead candidates, F1P-2P-N67P-L141P-Q279P-S377P and F2P-2P-N67P-Q279P (renamed as preF7P and preF6P), induced superior neutralizing antibody responses (NT50: 8,822 and 6,651) compared to DS-cav2 (NT50: 4,888) (Fig. 2e). Consistent with high neutralizing antibody levels against RSV A, DS-cav2-, preF7P-, and preF6P-immunized sera exhibited strong neutralizing activity against RSV B, with NT50 titers of 1,540, 2,708, and 2,068, respectively (Fig. 2f). At week 5, immunized mice were challenged with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV A (Long strain) via the intranasal (i.n.) route. At 5 days post-infection (dpi), the mice were euthanized. Their lungs were then harvested and subjected to analysis of viral loads using PFU assays and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The results showed that all of the placebo-vaccinated mice exhibited high levels of live virus (103.8 PFU/g) (Fig. 2g) and viral RNAs (107.5 RNA copy equivalents/g) (Fig. 2h). By contrast, both preF7P- and preF6P-vaccinated mice were highly protected with no detection of live virus (Fig. 2g) and significantly decreased levels of viral RNAs, by factors of > 60 (Fig. 2h). To explore the protection efficacy against RSV B challenge, new groups of BALB/c mice were vaccinated twice and then challenged with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV strain BA9. Consistent with the high protection efficacy against RSV A, preF7P and preF6P vaccinations substantially reduced lung viral RNA loads by 152- and 162-fold compared to the placebo (Fig. 2i). However, no live virus was detected in the placebo mice, suggesting that RSV B is less infectious in mice.

To further validate the superior immunogenicity of preF7P and preF6P, we performed additional immunization studies to directly compare them with DS-cav1, a key benchmark in RSV vaccine development. At both 2 μg and 12 μg doses, preF7P and preF6P elicited significantly higher neutralizing antibody titers compared to DS-cav1 against RSV A and B strains (Fig. 2j, k). Specifically, preF7P induced approximately 3.5-fold higher neutralizing antibody titers compared to DS-cav1, while preF6P showed approximately 2.5-fold increase (Fig. 2j, k).

Protection efficacy of preF7P and preF6P in cotton rats

The immunogenicity and protection efficacy of preF7P and preF6P were then evaluated in cotton rats, which represent a more permissive model of RSV infection. Groups of cotton rats were immunized with two doses of placebo, preF7P, or preF6P (50 μg per dose) via the intramuscular (i.m.) route, at a three-week interval (Fig. 3a). At week 5, half of the cotton rats in each group were bled to collect serum samples, then challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of RSV A (Long strain) via the i.n. route. The other half of each group were infected with 2 × 105 PFU of RSV B (BA9 strain). At 5 dpi, all of the cotton rats were euthanized and their nose and lung specimens were harvested to measure their viral loads. Their lung samples were also assessed for vaccine-mediated enhancement of pathology.

a Groups of cotton rats (n = 16) received placebo or F variants at 50 μg dose adjuvanted with Alum plus CpG1826 at weeks 0 and 3. At week 5, half of the cotton rats in each group (n = 8) were bled for sera collection, and challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of RSV long strain via the i.n. route. The other half of the cotton rats in each group (n = 8) were challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of the RSV BA9 strain via i.n. route. At 5 dpi, all of the cotton rats were euthanized, and nose and lung tissues were harvested for the detection of viral loads and determination of lung pathology scores. b, c Neutralization antibody titers of sera against the RSV Long strain (b) and RSV BA9 strain (c) by live virus microneutralization assays (n = 8 cotton rats per group). d–g Virus titrations in nose (d, f) and lung (e, g) tissues by PFU assays and RT-PCR following infection with the RSV Long strain (n = 8 cotton rats per group). h–k Virus titrations in nose (h, j) and lung (i, k) tissues by PFU assays and RT-PCR following infections of RSV BA9 strain (n = 8 cotton rats per group). l–n Lung pathology scores following challenge with RSV Long strain (l), RSV BA9 strain (m), or for FI-RSV vaccinated animals challenged with RSV Long strain (n) (n = 8 cotton rats per group for panels l, m; n = 6 cotton rats per group for panel n). Scores were assessed for alveolitis and for total pathology comprising alveolitis, peri-bronchiolitis, perivasculitis, and interstitial pneumonia. For b–n data are presented as mean values +/- SEM. P-values were analyzed via one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n.s. P > 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

All serum samples from the preF7P- and preF6P-immunized groups showed high neutralizing antibody levels, with NT50 titers reaching 3,247 and 2,136, respectively against RSV A (Fig. 3b); and 1,930 and 924, respectively against RSV B (Fig. 3c). By contrast, the sera from the placebo groups exhibited no detectable neutralizing activity against either RSV A or B (Fig. 3b, c). Notably, following RSV A infection all of the nose and lung samples from the preF7P and preF6P groups tested negative for live virus (Fig. 3d, e). By contrast, high levels of live virus were observed in the placebo controls with medium titers of 103.8 PFU/g for the nose samples (Fig. 3d) and 103.7 PFU/g for the lung samples (Fig. 3e). Similarly, the placebo samples showed high viral RNA copies, with medium titers of 107 copies per gram in the nose tissues (Fig. 3f) and 107.7 copies per gram in the lung tissues (Fig. 3g). Significantly lower levels of viral RNA copies were observed in the vaccinated groups, including ~200-fold decreases in the nose samples (Fig. 3f), and 157-fold (preF7P) and 75-fold (preF6P) reductions in the lung samples (Fig. 3g). Following RSV B challenge, high levels of live virus were observed in placebo cotton rats (medium titers of 103.1 PFU/g in nose tissues and 103.4 PFU/g in lung ones; Fig. 3h, i), differing significantly from the no detectable live virus present in the placebo mice. By contrast, preF7P and preF6P vaccinations resulted in no detectable live virus in all nose and lung tissue samples (Fig. 3h, i). When compared to the placebo controls, the cotton rats that received preF7P or preF6P vaccinations also showed substantial reductions of viral RNA loads, by 74–147-fold for nose tissues (Fig. 3j) and 118–160-fold for lung tissues (Fig. 3k). Thus, both preF7P and preF6P provided significant protection against RSV A and B strains. Moreover, lung pathology scores based on alveolitis in combination with peri-bronchiolitis, perivasculitis, and interstitial pneumonia, were minimal and comparable between the placebo and vaccine groups (Fig. 3l, m, and Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that both preF7P and preF6P did not induce enhanced respiratory disease. To further validate this safety profile, we included a formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccine as a positive control for enhanced respiratory disease (Fig. 3n and Supplementary Fig. 7), which exhibited significantly elevated alveolitis scores and higher overall pathology scores in contrast to both placebo and our candidate vaccines. Lung cytokine analysis following challenge revealed that both preF7P and preF6P groups exhibited significantly reduced IL-4 expression with comparable IL-5 and IL-13 levels relative to the placebo group (Supplementary Fig. 8a). By contrast, the FI-RSV group showed elevated expression of all Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13) compared to placebo (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These findings demonstrate the absence of Th2 bias in our vaccine candidates.

To further evaluate the potency of our constructs at lower doses and to compare them with the benchmark candidate DS-cav1, we conducted an additional immunization-challenge study where cotton rats were immunized with preF7P, preF6P, or DS-cav1 at reduced dose levels (0.5 μg and 5 μg), all adjuvanted with Al(OH)3 and CpG 1826. At the 5 μg dose, preF7P elicited neutralizing antibody titers that were 3.0-fold higher against RSV A and 4.2-fold higher against RSV B compared to DS-cav1 (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). Similarly, preF6P showed approximately 2-fold higher titers against both RSV A and B compared to DS-cav1 (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). Following challenge with RSV A, all vaccine groups (preF7P, preF6P, and DS-cav1) showed complete protection against live virus replication, with no detectable live virus in the lung tissues at both the 0.5 μg and 5 μg dose levels (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Consistent with its superior neutralizing antibody induction, the preF7P group demonstrated significantly lower viral RNA loads compared to the DS-cav1 group (Supplementary Fig. 9d), indicating more efficient viral clearance. Analysis of lung cytokine expression showed that both preF7P and preF6P at doses of 0.5 μg and 5 μg did not exhibit Th2-biased responses after immunization and challenge (Supplementary Fig. 9e–h).

Determination of the structures of prefusion-stabilized F with multiple proline substitutions

To verify the prefusion conformation of our RSV F constructs, we determined the X-ray crystal structures of preF6P, preF7P, and F2P-2P-N67P-L138P-G139P-L141P-Q279P-S377P (which was renamed preF8P) to 2.8, 2.9, and 2.8 Å, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). All three structures exhibited the same crystal form, P212121, with six identical chains forming two trimers in one asymmetrical unit, and higher levels of symmetry were not permitted during indexing (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 10a). The structures of preF6P, preF7P, and preF8P confirmed the expected prefusion conformation (Fig. 4a–d and Supplementary Fig. 10a, b), with small root-mean-square deviations of 0.923, 1.006, and 1.176 Å (Fig. 4b, 4d and Supplementary Fig. 10b), respectively, for all backbone atoms from the structural model of DS-cav2 (PDB: 5K6I). The largest mismatch with DS-cav2 was localized to the GS linker between the F1 and F2 subunits (Fig. 4b, d and Supplementary Fig. 10b). This difference should be originated from the different long linker designs used in our constructs, compared to the short GS linker used in DS-cav2. As the GS linker is occluded deep within the F trimers, its conformational difference was thought to have little impact on protein immunogenicity. Not surprisingly, most residues from the GS linker were not visible, owing to its intrinsic flexibility. Consistent with other reports, the foldon trimerization motif in the C-terminus of F1 was also not observed. Unambiguous electron density was observed for all designed proline substitutions in the structures of preF7P (P67, P138, P139, P141, P215, P279, and P377), preF6P (P67, P138, P139, P215, P216, and P279), and preF8P (P67, P138, P139, P141, P215, P216, P279, and P377; Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig. 10c). Representative electron density maps for residues 213–220, which encompass the P215 and P216 substitution sites, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. These structural studies suggested that, similarly to DS-cav2, all three of our variants existed in the prefusion conformation.

a, b RSV F trimers of preF7P (a) and preF6P (b) with each promoter shown in a different color. c, d Alignment of a promoter from preF7P (c, orange ribbon) and preF6P (d, green ribbon) with DS-cav2 (white ribbon, PDB ID 5K6I). e, f Proline substitutions in preF7P (e) and preF6P (f). Blue, nitrogen atoms; red, oxygen atoms.

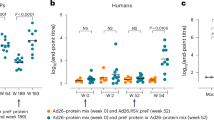

Development and immunogenicity evaluation of a clinical-grade preF7P RSV vaccine

To further develop clinical-grade preF7P-based recombinant protein subunit vaccine against RSV, preF7P was constructed without any purification tag and transformed into clinical-grade CHO cell lines. Monoclonal stable cell lines were screened for antigen expression. One cell line with high antigen abundance and high passage stability was selected for further building of cell banks and large-scall production. Notably, preF7P reached expression levels of 10.3 g/L, with a final purified antigen yield of 3.8 g/L (Fig. 5a). Purified preF7P reached > 99% purity and a size of 168 kDa, as determined via analytical ultracentrifugation (Fig. 5b–d). Real-time biophysical assays showed that preF7P exhibited strong binding affinity to prefusion-specific mAbs, including D25 (KD of 0.095 nM), AM22 (KD of <0.001 nM), AM14 (KD of 0.074 nM), and hRSV90 (KD of 0.081 nM; Fig. 5e–h). In addition, for the mAbs that recognized both preF and postF, preF7P displayed apparent binding with KD values ranging from <0.001 nM to 2.437 nM (Fig. 5i–k). Notably, no binding of preF7P to postfusion-specific 4D7 was detected (Fig. 5l). Thus, the binding data of preF7P confirmed its prefusion conformation and the integrity of the prefusion epitopes. We next evaluated the immunogenicity of preF7P formulated with clinical-grade MF59 (preF7P-MF59) or CpG1018 plus alum (Al-CpG, preF7P-Al-CpG) in mouse, Sprague Dawley (SD) rat, and cynomolgus macaque models. All animals received two intramuscular vaccinations in a prime-boost regimen on Days 0 and 21. Doses of 12 μg, 120 μg, and 120 μg of preF7P were administered to C57BL/6 mice, SD rats, and cynomolgus macaques, respectively. Following the two-dose regimen, both adjuvant formulations of preF7P induced robust antigen-specific IgG titers (>10^6) in mice (Fig. 5m). To assess antigen-specific cellular immunity, splenocytes from immunized mice were harvested, stimulated with a preF7P peptide pool, and analyzed for Th1 (IFN-γ and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-4) cytokine production via ELISPOT. A Th1-skewed response was observed in the Al-CpG group, while a mixed Th1/Th2 response was seen in the MF59 group (Fig. 5n–p). In SD rats, both adjuvant formulations induced strong antigen-specific and neutralizing antibody responses, whereas no antigen-specific or neutralizing antibodies were detected in the negative control or adjuvant control groups (Fig. 5q, r and Supplementary Fig. 12a). The Al-CpG group elicited significantly higher neutralizing antibody titers compared to the MF59 group, with titers of 7,971 vs. 3,313 against RSV A and 4,740 vs. 2,343 against RSV B (Fig. 5q, r). Similarly, sera from twice-immunized macaques demonstrated robust antigen-specific IgG responses, with titers of 31,353 in the MF59 group and 135,765 in the Al-CpG group (Fig. 5s). Consistent with the SD rat data, the Al-CpG group generated higher neutralizing antibody titers than the MF59 group, with titers of 279 vs. 45 against RSV A and 256 vs. 83 against RSV B (Fig. 5t). In summary, preF7P, formulated with either MF59 or Al-CpG, demonstrated excellent immunogenicity across all three animal models.

a PreF7P was produced in an industry-standard CHO cell system using GMP-grade manufacturing. Antigen expression levels, yields after separation and purification, and purity levels for vaccine stock solution by SEC-HPLC are shown. b SDS-PAGE migration profiles of increasing amounts of GMP grade preF7P. c, Western blot analysis of increasing amounts of GMP grade preF7P using a commercial RSV F-specific antibody (Sino Biological) as a probe. For b and c, representative data are shown from three independent experiments with similar results. d Ultracentrifugation sedimentation profiles of GMP grade preF7P. e–l Representative BIAcore diagrams of GMP grade preF7P bound to a panel of RSV F-specific mAbs including prefusion-specific D25 (e), AM22 (f), AM14 (g), and hRSV90 (h); pre/postfusion-recognized 101 F (i), MPE8 (j), and palivizumab (k); postfusion-specific 4D7 (l). m–p C57BL/6 mice (n = 18 per group) were administered placebo or preF7P adjuvanted with MF59 or Alum plus CpG1826 at weeks 0 and 3. At week 4, half of the mice in each group (n = 9) were euthanized for spleen collection and subsequent ELISPOT assay. At week 5, the remaining mice (n = 9) were bled for serum collection. m Antigen-specific IgG titers in serum collected five weeks post-initial vaccination were measured via ELISA. n–p Cellular immune responses in female C57BL/6 mice (n = 9 per group) following two doses of vaccine or placebo were evaluated by ELISPOT. Splenocyte secretion of IFN-γ (n), IL-2 (o), and IL-4 (p) in response to RSV F stimulation were quantified to assess vaccine-induced immunity. q, r, SD rats (n = 10 per group) received placebo or F variants adjuvanted with MF59 or Alum plus CpG1826 at weeks 0 and 3. Sera were collected at weeks 3 and 7, and neutralizing antibody titers against RSV A strain (q) and RSV B strain (r) were determined using live virus CPE assays. s, t Cynomolgus macaques (n = 4 per group) were administered placebo or preF7P adjuvanted with MF59 or Alum plus CpG1826 at weeks 0 and 3. Sera were collected at weeks 3 and 7. s Antigen-specific IgG titers in serum were measured by ELISA. t Neutralizing antibody titers against RSV A and RSV B strains were assessed using live virus microneutralization assays.For m–t data are presented as mean values +/- SEM. P-values were analyzed via one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n.s. P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. Animal illustrations in panels m, q, and s were obtained from SciDraw.io under Creative Commons 4.0 (CC-BY) license. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Protective efficacy of the clinical-grade preF7P vaccine in pre-infection and long-term mouse models

To simulate real-world conditions where individuals are pre-exposed to RSV and subsequently receive an RSV vaccine as a booster, we employed a pre-infection mouse model to assess the vaccine’s protective efficacy. In this study, BALB/c mice were initially infected with the RSV Long strain at week 0 (Fig. 6a). At week 4, they received a single injection of either PBS, adjuvant (MF59 or Al-CpG), or 6 μg (Low Dose, LD) or 12 μg (High Dose, HD) of preF7P formulated with MF59 or Al-CpG (Fig. 6a). Serum samples were collected, and the mice were subsequently challenged with RSV at week 6 (Fig. 6a). Pre-exposure resulted in the elicitation of antigen-specific IgG titers averaging approximately 10^4, alongside low neutralizing antibody titers of 31 against RSV A and 19 against RSV B (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 12b). Importantly, vaccination with either preF7P-MF59 or preF7P-Al-CpG significantly augmented neutralizing antibody titers: 18-fold (preF7P-MF59-HD), 15-fold (preF7P-MF59-LD), 72-fold (preF7P-Al-CpG-HD), and 30-fold (preF7P-Al-CpG-LD) against RSV A, as well as 8-fold (preF7P-MF59-HD), 7-fold (preF7P-MF59-LD), 28-fold (preF7P-Al-CpG-HD), and 14-fold (preF7P-Al-CpG-LD) against RSV B (Fig. 6b). Following RSV challenge, the mice in the placebo control group exhibited high lung loads of live virus and viral RNA copies (Fig. 6c–e). In contrast, pre-exposure conferred significant protection, as indicated by the absence of live virus and reductions of viral RNA copies by 1541-fold for RSV A and 491-fold for RSV B in the PBS group (Fig. 6c–e). Consistent with the elevated neutralizing antibody levels, vaccination with either preF7P-MF59 or preF7P-Al-CpG further reduced viral RNA copies by 2–7-fold (RSV A) and 17–218-fold (RSV B) for preF7P-MF59, and by 3–4-fold (RSV A) and 79–82-fold (RSV B) for preF7P-Al-CpG (Fig. 6d, e). Notably, in the preF7P-MF59-LD group, viral RNA copies were undetectable following RSV B challenge (Fig. 6e). These findings indicate that the preF7P-based vaccines effectively enhance the RSV-elicited immune response, suggesting a high degree of structural consistency between preF7P and the native F protein in the virus.

a BALB/c mice (n = 20 per group) were pre-infected with 1×105 PFU of RSV Long strain at week 0. At week 4, mice received either placebo, MF59, Alum plus CpG1826, or F variants adjuvanted with MF59 or Alum plus CpG1826. At week 6, sera were collected, and the mice were challenged with 1×105 PFU of RSV Long strain (n = 10 per group) or RSV BA9 strain (n = 10 per group). Lung samples collected at 5 dpi were subjected to viral titration via PFU assays and RT-PCR analysis. b Neutralization antibody titers of sera against the RSV Long strain and RSV BA9 strain by live virus CPE assays (n = 10 mice per group). c Viral titers in lung tissues were quantified by PFU assays following infection with RSV Long strain (n = 10 mice per group). d, e Viral titers in lung tissues were measured by RT-PCR following infection with RSV Long (d, n = 10 mice per group) and RSV BA9 (e, n = 10 mice per group) strains. f, BALB/c mice (n = 9 per group) received placebo or F variants adjuvanted with MF59 or Alum plus CpG1826 at weeks 0 and 3. Sera were collected at weeks 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, and 27. At week 27, mice were challenged with 1×105 PFU of RSV Long strain (n = 5 per group) or RSV BA9 strain (n = 4 per group), and lung samples were collected at 5 dpi for viral titration by PFU assays and RT-PCR analysis. g, h Neutralizing antibody titers in sera against RSV Long (g, n = 9 mice per group) and RSV BA9 (h, n = 9 mice per group) strains were measured using live virus CPE assays. i, Viral titers in lung tissues were quantified by PFU assays following infection with RSV Long strain (n = 5 mice per group). j, k Viral titers in lung tissues were determined by RT-PCR following infection with RSV Long (j, n = 5 mice per group) and RSV BA9 (k, n = 4 mice per group) strains. For b–e and g–k, data are presented as mean values +/- SEM. P-values were analyzed via one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n.s. P > 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). The dashed line indicates the limit of detection. Syringe, blood drop, and virus illustrations in panels a and f were obtained from SciDraw.io under Creative Commons 4.0 (CC-BY) license. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To assess the durability of humoral immune responses and long-term protective efficacy, BALB/c mice were immunized with 12 μg of preF7P adjuvanted with either MF59 or Al-CpG at weeks 0 and 3 (Fig. 6f). Serum samples were collected between weeks 3 and 27, and the mice were challenged with RSV A or RSV B at week 27 (Fig. 6f). In the preF7P-MF59 group, antigen-specific IgG titers peaked at 2,623,547 by week 7, followed by a gradual decline to approximately 1,500,000 between weeks 7 and 27 (Supplementary Fig. 13). Neutralizing antibody titers against RSV A ranged from 1,742 to 6,451 between weeks 7 and 15, subsequently decreasing to 640 by week 27, while titers against RSV B remained between 1,618 and 1,891 during weeks 7–15, before stabilizing at 1,023 by week 27 (Fig. 6g, h). Similarly, in the preF7P-Al-CpG group, IgG titers reached 4,222,363 by week 7 and stabilized at approximately 2,000,000 from weeks 7 to 27 (Supplementary Fig. 13). Neutralizing titers against RSV A were sustained at 2,195–2,560 during weeks 7–11, dropping to 435 by week 15 and then remaining stable through week 27 (Fig. 6g). Against RSV B, titers peaked at 2,042 by week 7 and stabilized around 550 from weeks 15 to 27 (Fig. 6h). Following RSV challenge, no live virus was detected in the lungs of vaccinated mice, whereas the placebo group exhibited viral loads of up to 5,193 PFU/g (Fig. 6i). Compared to the placebo group, viral RNA copies were reduced by 122-fold for RSV A and 286-fold for RSV B in the MF59 group, and by 41-fold for RSV A and 37-fold for RSV B in the Al-CpG group (Fig. 6j, k). These data indicate that preF7P-based vaccination confers long-term protection, persisting for at least six months in this mouse model.

Discussion

To drive virus-cell fusion, the class I fusion proteins on the virus surface are temporarily locked into an energetically unfavorable prefusion state12,37. The pre- to postfusion transition releases sufficient energy to pull the membranes of the virus and the host cell together, allowing them to fuse43,44,45. This membrane fusion mechanism means that preF proteins are unstable, and the most potent neutralizing antibodies that impair the fusion functions and neutralize infectivity can only be elicited by the preF proteins as the postF proteins lose the potential for virus-cell fusion. For vaccine development, the stabilization engineering of preF proteins has thus become critical9,10,46,47.

In this study, we employed a streamlined proline-scanning strategy to design a prefusion-stabilized RSV F antigen with high expression levels. Consistent with a previous report25, S215P efficiently traps F proteins in the prefusion conformation (Fig. 1c) by disfavoring the refolding of the L0 loop between the α4 and α5 helices. Importantly, the introduction of double mutations (L138P and G139P) resulted in a 24-fold increase in preF expression (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2). However, this enhancement was accompanied by a modest increase in the binding of postfusion-specific antibodies in the cell supernatant (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2), likely due to trace amounts of postF. Subsequent proline substitutions not only further boosted preF yield but also diminished postfusion-specific antibody binding (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4). Our lead candidate, preF7P, demonstrated strong immunogenicity and protective efficacy against RSV A and B strains in murine and cotton rat models, supporting its progression to clinical development. In stable clinical-grade CHO cell lines, preF7P achieved expression levels of approximately 10 g/L, highlighting its potential for large-scale vaccine production. Formulated with MF59 or Al-CpG adjuvants, preF7P elicited potent immune responses across mouse (Fig. 5m–p), SD rat (Fig. 5q, r), and cynomolgus macaque (Fig. 5s, t) models, significantly enhanced neutralizing antibody titers following RSV infection (Fig. 6b), and offered superior protection compared to infection alone (Fig. 6d, e). These findings suggest a high structural fidelity of preF7P to the native prefusion F protein. Notably, preF7P also provided durable protective efficacy, maintaining significant immunogenicity for at least six months in mice (Fig. 6i–k).

The disulfide design strategy represents an efficient way to stabilize the prefusion protein conformation by restraining mobile regions to regions that remain static during the pre- to postfusion transition24,31. However, a considerable quantity of unwanted aggregates is usually involved during the expression of disulfide-engineered variants, as was demonstrated by DS-cav2 (Fig. 2c), possibly owing to mismatches between introduced cysteines and naturally occurring ones throughout the unaltered portions of the protein. For protein-based vaccines, such aggregates can be removed through a separation and purification process. However, for gene-based vaccines, including DNA/messenger RNA vaccines, as well as recombinant virus-vectored vaccines, these aggregates are produced in host cells where they cannot be purified48,49,50,51. Aggregate byproducts therefore exist within vaccinated individuals and thus may be associated with unpredictable additional safety risks. By contrast, our preF7P construct from the proline-scanning strategy was expressed as a single peak with little aggregates. Thus, preF7P-based gene vaccines theoretically have better safety profiles. Moreover, the high expression of preF7P may also improve gene-based vaccines by producing more antigen per vaccine molecule, thus improving efficacy at the same dose or maintaining efficacy at lower doses.

Proline has restricted backbone torsion angles. The proline-scanning strategy is based on scanning loops positioned before α helices, aiming to improve the loop or helix rigidity afforded by engineered proline substitutions as “anchors”, and thus improving protein structural stability. Unlike other structural-based stabilizing methods—including the introduction of disulfide bonds, cavity-filling mutations, and electrostatic interaction optimization—atomic-level information is not as critical for the proline-scanning strategy. One low-resolution cryo-EM structure or one structure from a homologous protein with low sequence identity can also serve as the template. Thus, the proline-scanning strategy may be more advantageous for the development of vaccine candidates against emerging viruses without determined high-resolution structures. In addition to stabilizing the prefusion conformation for class I fusion glycoproteins, the proline-scanning strategy should be expanded to be applied to improve expression and structural stability for any protein with an abundance of α helices.

Enhanced Respiratory Disease (ERD) remains a critical concern for RSV vaccine development. Our comprehensive assessments in cotton rats showed no ERD tendencies with preF7P or preF6P, while FI-RSV controls exhibited the typical pathological features associated with ERD in this model. However, the mechanisms underlying ERD in RSV-naïve populations remain incompletely understood, and current animal models have inherent limitations in predicting human responses52. This limitation was recently highlighted by Moderna’s RSV mRNA vaccine development, where no evidence of ERD was observed in preclinical animal studies, yet safety concerns emerged during clinical evaluation in RSV-naïve individuals53. Despite the encouraging safety profile demonstrated in our preclinical studies, there is no doubt that ERD risk needs to be closely monitored in clinical studies, especially in RSV-naïve populations.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal experiments involving mice and cotton rats were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Changping Laboratory, while experiments involving Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats and cynomolgus macaques were approved by the JOINN Animal Ethics Committee. All procedures were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Cells, viruses, and animals

HEK293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216), Vero cells (ATCC, CCL-81), HEp-2 cells (ATCC, CCL-23), and BHK-21 cells (ATCC, CCL-10) were all cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS,

Gibco) and 1% (v/v) penicillin-treptomycin (p/s) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Expi 293 F (Gibco, A14527) cells were cultured in SMM 293-TII-N medium (Sino Biological Inc.) supplemented with 1% (v/v) p/s at 37°C and 5% CO2. RSV strains Long (A subgroup) and BJ86673 (BA9, B subgroup) were kindly provided by L. Zhao (Capital Institute of Pediatrics, Beijing, China). RSV was propagated in HEp-2 cells and titrated in BHK-21 cells using a plaque-forming units (PFU) assay. Female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (6–8 weeks old, equal numbers of male and female) were obtained from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Company (licensed by Charles River). Female cotton rats (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from SiPeiFu (Beijing) Biotechnology Company, and cynomolgus macaques (3–4 years old, equal numbers of male and female) were obtained from JOINN Laboratories. Mice and cotton rats were housed at the Laboratory Animal Center of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), while SD rats and cynomolgus macaques were housed at JOINN Laboratories. All animals were maintained in specific pathogen-free (SPF) facilities and allowed free access to water and a standard chow diet and provided with a 12-h light and dark cycle (temperature, 20–25 °C; humidity, 40–70%). RSV infection experiments were conducted in a BSL-2 facility at the Laboratory Animal Center of China CDC.

Screening of prefusion-stabilized RSV F variants by ELISA

RSV F variants with 8 × His tags at their C-termini were cloned in a pCAGGS plasmid. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected in a 12-well-microplate format. At 72 h post-transfection, cell culture supernatants were harvested and assessed for preF and postF expression levels by ELISA. For ELISA, purified mAb AM14, 4D7, D25, AM22, hRSV90, Pali, or MPE8 was plated at 200 ng per well in 96-well ELISA plates overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with 5% skimmed milk at room temperature (RT) for 30 min; 100 μL cell supernatant at suitable dilutions was added to each well for 1 h at RT. An anti-His antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was used to trap the antigen at a concentration of 1 μg/mL at RT for 1 h. TMB chromogen solution was then used for the color development reaction, which was stopped by the addition of 2 M H2SO4. Reaction color changes were quantified at 450 nm in a microplate reader (TECAN). For preF protein quantitation, prefusion-specific AM14 and anti-His antibody conjugated with HRP was used as a coating and detection antibody in a sandwich ELISA. The amount of preF protein was determined from the calibration curves constructed using known concentrations of the DS-cav2 standard. For our heat stability study of the constructed F variants, various F proteins were diluted to 0.1 mg/mL and incubated at 25 °C for two weeks. Heat stability was assessed by comparing preF concentrations between heat-stressed and unstressed samples.

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out on RSV F variant proteins using the ProteomeLab XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter). Volumes of 380 mL of protein sample (A280 = 0.6–0.8) and 400 mL of PBS buffer were injected into appropriate channels of 12 mm double-sector aluminum epoxy cells with sapphire windows. Solutions were centrifuged at 8900 x g at 20 °C in an An-60Ti rotor for 8 h. Scans were collected at 280 nm, with 3 min elapsed between each scan. Data were analyzed using the continuous sedimentation coefficient distribution c(s) model in SEDFIT software.

SDS–PAGE analysis and western blot

Cell culture supernatants or purified protein samples were analyzed on 10% (w/v) Tris-Gly BeyoGel™ Plus PAGE gels under reducing conditions. For western blot, transfer to an NC membrane was performed using a semi-dry apparatus (Ellard Instrumentation). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS buffer containing 0.5% Tween-20. RSV F proteins were detected using a commercial RSV-F-specific antibody (Sino Biological), followed by secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Abbkine). The blot membrane was scanned on a Tanon 5200 instrument and the resultant images were analyzed using Tanon software.

Expression and purification of RSV F variants

The coding sequence for RSV F variants based on the A2 strain was codon-optimized for mammalian cell expression and synthesized. For each construct, a signal peptide sequence of MKCLLYLAFLFIGVNC was added to the protein’s N terminus for protein secretion, and an 8 × His tag was added to the C terminus to facilitate further purification processes. These constructs were synthesized by GenScript, China. They were cloned into the pCAGGS vector, respectively, and transiently transfected into HEK293F cells. After five days, the supernatant was collected, and soluble protein was purified by Ni-affinity chromatography using a HisTrapTM HP 5 mL column (GE Healthcare). The sample was further purified via gel filtration chromatography with Superose 6 10/300 GL SEC column (GE Healthcare) in a buffer composed of 5 mM Na-Citrate (pH 6.5) and 150 mM NaCl. The eluted peaks were analyzed by SDS-PAGE for protein purity.

Antibody expression and purification

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) of D25, AM22, AM14, Palivizumab (Pali), MPE8, hRSV90, 101 F, and 4D7, and the corresponding fragments of antibody-binding (Fabs), were secreted from transiently transfected HEK293F cells with pCAGGS plasmids containing coding sequences for Ig heavy chain and light chains. The cell culture was collected on day 5 post-transfection. The supernatant was mixed with one volume of buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, and filtered using a 0.22 μm filter. The mixture was passed through a HiTrap Protein A HP column (GE Healthcare) for mAbs, or through a HiTrap Protein G HP column (GE Healthcare) or the HiTrap Protein L HP column (GE Healthcare) for Fabs. The bound protein was detached from the column using 0.1 M glycine, pH 3.0. The elution was adjusted to neutral pH via the addition of 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, and further purified by gel filtration. The mAbs and Fabs were then buffered with PBS, concentrated, and stored at −80 °C for further use.

Nano differential scanning fluorimetry

For nano-differential scanning fluorimetry (Nano-DSF), a Prometheus NT.48 (NanoTemper Technologies) was used. RSV F variant proteins at 1 mg/mL were loaded in Nano-DSF grade standard capillaries and then exposed to thermal stress from 25° to 95°, at a rate of 1 °C/min. Intrinsic fluorescence at 330 and 350 nm (F330/F350) was recorded with a dual-UV detector. The melting temperature (Tm) was calculated using the PR.ThermControl software.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

SPR binding experiments were carried out using a BIAcore 8 K (GE Healthcare) at RT. For all measurements, a buffer consisting of 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4, and 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 was used as running buffer, and all proteins were exchanged into this buffer in advance. The binding kinetics of RSV F proteins to RSV F-specific mAbs were assessed using a multi-cycle model. Purified Fabs were coupled with biotin via the NHS-PEG12-Biotin reagent (Thermo Fisher) and immobilized on a SA chip at ~100 response units. After three injections of running buffer, 2-fold dilutions of increasing concentrations of RSV F variants were injected over both the ligand-bound and reference flow cells at a rate of 30 μL/min. The following concentration ranges were used for each antibody-antigen pair: D25:RSV F, 0.0625-8 nM; AM22:RSV F, 0.03125-4 nM; AM14:RSV F, 0.03125-4 nM; Palivizumab:RSV F, 0.5-64 nM; MPE8:RSV F, 0.03125-4 nM; 101 F:RSV F, 0.125-16 nM; hRSV90:RSV F, 0.03125-4 nM; 4D7:RSV F, 1-128 nM. Data were collected over time. After each cycle, the sensor surface was regenerated via a short treatment using 10 mM glycine-HCl (pH 1.7: D25, AM22, MPE8, hRSV90; pH 1.5: AM14, Palivizumab, 101 F, 4D7). The raw data and affinities were collected and calculated using a 1:1 fitting model with BIAcore 8 K analysis software (BIAevaluation v.4.1). All measurements were performed in triplicate, and results are presented as Mean ± SEM.

Animal experiments

To assess the immunogenicity of RSV F protein variants, female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were administered two intramuscular (i.m.) injections at weeks 0 and 3. The mice received either a placebo or 12 μg of RSV F protein adjuvanted with 50 μg Al(OH)3 (Invivogen) and 10 μg CpG 1826 (Invivogen). Serum samples were collected at week 5, heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min, and stored at −20 °C. For RSV challenge experiments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and inoculated intranasally (i.n.) with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV in 50 μL of DMEM. Five days post-challenge (dpi), mice were euthanized, and lung tissues were harvested for viral load quantification. For immunogenicity comparison with DS-cav-1, female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were administered two intramuscular injections of either 2 μg or 12 μg of preF7P, preF6P, or DS-cav-1 (Sino Biological), all adjuvanted with 50 μg Al(OH)3 and 10 μg CpG 1826, at weeks 0 and 3. Serum samples were collected at week 5, heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min, and stored at −20 °C.

In the cotton rat model (6–8 weeks old), animals were immunized at weeks 0 and 3 with either placebo or 50 μg RSV F protein adjuvanted with 500 μg Al(OH)3 and 100 μg CpG 1826. At week 5, sera were collected, and rats were challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of RSV in 100 μL DMEM via the i.n. route. At 5 dpi, rats were euthanized, and nasal turbinate and lung tissues were collected for viral load analysis. Lung tissues were also subjected to histopathological scoring. For the evaluation of vaccine-enhanced disease, a formalin-inactivated RSV (FI-RSV) vaccine was prepared as an additional control. Briefly, RSV Long strain was propagated in HEp-2 cells and inactivated with 0.01% formalin at 37 °C for 72 h. The inactivated virus was purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Cotton rats received 20 μg FI-RSV (quantified by BCA assay) formulated with Al(OH)3 adjuvant, administered according to the aforementioned immunization and challenge regimen. To further evaluate the potency of our constructs at lower doses and to compare them with the benchmark candidate DS-cav1, cotton rats were immunized with preF7P, preF6P, or DS-cav1 at two dose levels (0.5 μg and 5 μg), all adjuvanted with Al(OH)3 and CpG 1826. Following a prime-boost regimen with a three-week interval, serum samples were collected at week 5 for neutralizing antibody analysis against RSV A and B strains. All animals were subsequently challenged via the i.n. route with 2 × 105 PFU of RSV in 100 μL DMEM. At 5 dpi, rats were euthanized, and lung tissues were collected for viral load analysis.

To evaluate the immunogenicity of the clinical-grader preF7P protein, female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) received two i.m. doses of either placebo or 12 μg preF7P protein adjuvanted with MF59, or 75 μg Al(OH)3 and 300 μg CpG 1018 (Dynavax), at weeks 0 and 3. Spleens were harvested at week 4 for ELISPOT assays, and sera were collected at week 5 for further analysis, followed by heat inactivation and storage at −20 °C. Similarly, female SD rats (6–8 weeks old) were inoculated twice, with placebo or 120 μg preF7P protein adjuvanted with MF59, or 750 μg Al(OH)3 and 3000 μg CpG 1018. Serum samples were collected at weeks 3 and 7, inactivated, and stored under the same conditions. To extend the evaluation to non-human primates, Cynomolgus macaques (3–4 years old) were inoculated at weeks 0 and 3 with either placebo or 120 μg preF7P protein adjuvanted with MF59, or 750 μg Al(OH)3 and 3000 μg CpG 1018. Serum samples were collected at weeks 3 and 7, heat-inactivated, and stored at −20 °C.

To investigate the protective efficacy of preF7P against RSV-A and RSV-B strains in a pre-infection mouse model, female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were initially challenged i.n. with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV Long at week 0. At week 4, mice were administered placebo, MF59, Alum plus CpG 1018, or preF7P protein adjuvanted with MF59 or Alum plus CpG 1018. Sera were collected at week 6, followed by a i.n. challenge with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV Long or BA9 strain. Lung tissues were harvested at 5 dpi for viral titrations.

Long-term protection efficacy of preF7P was evaluated by inoculating female BALB/c mice with placebo or 12 μg preF7P adjuvanted with MF59, or 75 μg Al(OH)3 and 300 μg CpG 1018, at weeks 0 and 3. Serum samples were collected at weeks 7, 11, 15, 19, 23, and 27, inactivated at 56 °C, and stored at −80 °C. At week 27, mice were i.n. challenged with 1 × 105 PFU of RSV Long or BA9 strain. Lung tissues were collected at 5 dpi for viral load analysis.

ELISA

ELISA plates (Corning) were coated overnight with 2 μg/mL of RSV F variant proteins in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, and blocked using 5% skim milk in PBST. Serum samples were diluted and added to each well. The plates were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody and developed with 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate. Reactions were stopped with 2 M H2SO4, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (TECAN). The endpoint titer was defined as the highest reciprocal dilution of serum to yield an absorbance of > 2.1-fold of the background values. Antibody titers below the limit of detection were determined to be half of the limit of detection.

RSV microneutralization assays

The serum neutralizing activity was assessed using a CPE-based microneutralization assay. Briefly, hep-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates one day prior to infection. On the day of infection, heat-inactivated serum samples were serially diluted and incubated with RSV (100 TCID50) for one hour at 37 °C. The virus-serum mixture was then added to wells containing 1 × 104 hep-2 cells and incubated at 37 °C. Cells infected with RSV A (Long strain) or RSV B (BA9 strain) were used as positive controls, while uninfected cells served as negative controls. Cytopathic effects (CPE) were observed and recorded on day 5 post-infection. Virus back-titration was performed to ensure the accuracy of viral titers. The 50% neutralization titers (NT50) were defined as the serum dilution required for 50% neutralization of viral infection.

Determination of virus titers in tissue samples

Viral loads in lung and nasal turbinate tissues were determined by PFU assays and RT-PCR. For the PFU assays, the supernatants of the lung and nasal turbinate homogenates were diluted 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1000 in DMEM, then added in duplicates to pre-plated BHK-21 cell monolayers in 12-well plates. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, the supernatant was discarded and a mixture of 2% methylcellulose gel and 2 × DMEM (50: 50%) was added. After incubating at 37 °C for 4 days, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were fixed with a 50:50% methanol:ethanol mixture at room temperature for 10 min before being washed with PBST. The cells were blocked with 5% skim milk for 30 min and stained for 1 h with HRP-labeled palivizumab. After washing with PBST, TrueBlueTM peroxidase substrate (KPL) was added for color development and the cells were rinsed with water to stop the reaction. The plates were then air-dried, plaques were counted, and viral titers were expressed as PFU/g of tissue.

For RT-PCR, viral RNA was isolated from 200 μL supernatants of homogenized tissues using a magnetic bead extraction kit (EmerTher). RSV N gene detection was performed using real-time RT-PCR with a commercial kit (Shanghai Yiyan Biotechnology) on QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification was performed as follows: 50 °C for 15 min, 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Viral loads were expressed on a log10 scale as viral copies per gram, after a standard curve was constructed.

Pulmonary histopathology

The lung tissues of the cotton rats were prepared in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. They were then cut into 4 μm sections, deparaffinized, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Four parameters of pulmonary inflammation were assessed: peribronchiolitis (inflammatory cell infiltration around the bronchioles), perivasculitis (inflammatory cell infiltration around the small blood vessels), interstitial pneumonia (inflammatory cell infiltration and thickening of the alveolar walls), and alveolitis (cells within the alveolar spaces). Scores were assigned based on the intensity of inflammation in the lungs and the extent of the damaged area. Score 0: No lesions; score 1: ≤ 5% of lung is compromised with severe lesions, or ≤ 25% with mild lesions; score 2: ≤ 25% of lung is compromised with severe lesions, or ≤ 75% with mild lesions; score 3: ≤ 75% of lung is compromised with severe lesions, or ≤ 100% with mild lesions; score 4: ≤ 100% of lung is compromised with severe lesions.

Lung cytokine analysis

Total RNA was extracted from homogenized lung tissue using an extraction kit (EmerTher). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara) in a final reaction volume of 20 µL, containing 0.5 µM of each primer. The primer sequences used for target genes are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Amplifications were conducted on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) under the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec; with a final melt curve analysis. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were converted to relative expression levels and normalized to the β-actin mRNA level in each sample. Samples with a β-actin Ct value exceeding 20 were designated as suboptimal quality, requiring cDNA re-synthesis.

Crystallization, data collection and structure determination

Protein crystals were grown via the vapor-diffusion method at 18 °C in hanging drops (1 μL of RSV F variant protein solution at 5 mg/mL plus 1 μL of reservoir solution) that had equilibrated 200 μL of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate pH 5.5 and 24% Jaffamine® ED-2001, pH 7.0. For data collection, the crystals were cryo-protected by briefly soaking them in reservoir solution supplemented with 6% (v/v) glycerol before flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility BL10U2 (wavelength, 0.9792 Å). The data were processed using XDS Program Package. The structures were solved by the molecular replacement method using the Phaser program in Phenix. The structural models were then adjusted in Coot and refined using the Phenix.refine function. Structure images were then generated by ChimeraX or Pymol.

Pilot scale production of preF7P

The coding sequence for preF7P was codon-optimized for mammalian cell expression. A signal peptide sequence was added to the N terminus for protein secretion, and no tag sequence was added to the C terminus. Clinical-grade CHOK1-GenS cell lines expressing preF7P were generated and further selected for clones with high expression levels. The cell lines with the highest levels of antigen expression were selected for large-scale immunogen production and purification.

ELISPOT assay

Antigen-specific T cell responses were evaluated by IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 ELISPOT assays. Spleens from C57BL/6 mice were harvested at one week post the second vaccination, and splenocytes were isolated. 96-well flat-bottom plates were pre-coated with 10 μg/ml of anti-mouse IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-4 antibodies (BD Biosciences) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The wells were blocked with 200 μL of RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 2 h at room temperature. Splenocytes were resuspended at 1 × 107 cells/ml, and 100 μL of the cell suspension was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. RSV preF7P polypeptide (1 μg/ml) and 99 μl of RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS were added to the wells, and PMA was used as a positive control. After 18 h of incubation, the cells were discarded, and the plates were sequentially incubated with biotinylated IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-4 detection antibodies (BD Biosciences), streptavidin-HRP conjugate (BD Biosciences), and AEC substrate (BD Biosciences). Plates were washed with deionized water, dried, and developed for 15 min to visualize spots. Spot counts were analyzed using an automated ELISPOT reader and image analysis software (Cellular Technology).

Statistics

GraphPad Prism v.9.0.1 software was used for data analysis. Data are represented as means ± SEMs. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired, two-sided Student’s t-tests for two-group comparisons, and via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons between > 2 groups. P values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant, where *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The atomic coordinates and corresponding structure factors for the X-ray crystal structures of preF6P, preF7P, and preF8P have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession codes PDB 8ZQ6, 8ZPY, and 8ZQ7, respectively. Previously published structures used in this study include: 4JHW (RSV prefusion F structure) and 5K6I (DS-cav2 prefusion F structure). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Griffin, M. P. et al. Single-dose nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in preterm infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 415–425 (2020).

Langedijk, A. C. & Bont, L. J. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and novel interventions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 734–749 (2023).

Kampmann, B. et al. Bivalent prefusion f vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1451–1464 (2023).

O’Brien, K. L. et al. Efficacy of motavizumab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease in healthy Native American infants: a phase 3 randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 15, 1398–1408 (2015).

McLellan, J. S. et al. Structure-based design of a fusion glycoprotein vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus. Science 342, 592–598 (2013).

Ginsburg, A. S. & Srikantiah, P. Respiratory syncytial virus: promising progress against a leading cause of pneumonia. Lancet Glob. health 9, e1644–e1645 (2021).

Guo, L., Deng, S., Sun, S., Wang, X. & Li, Y. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality, transmission zones, and implications for seasonal prevention strategy in China: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 12, e1005–e1016 (2024).

Langedijk, A. C. et al. The genomic evolutionary dynamics and global circulation patterns of respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Commun. 15, 3083 (2024).

Wilson, E. et al. Efficacy and Safety of an mRNA-Based RSV PreF Vaccine in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 2233–2244 (2023).

Papi, A. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 595–608 (2023).

McLellan, J. S. et al. Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody. Science 340, 1113–1117 (2013).

Cai, Y. et al. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Sci. (N. Y., N. Y.) 369, 1586–1592 (2020).

Falsey, A. R. & Walsh, E. E. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F vaccine. Cell 186, 3137–3137.e3131 (2023).

Gilman, M. S. A. et al. Transient opening of trimeric prefusion RSV F proteins. Nat. Commun. 10, 2105 (2019).

Taleb, S. A., Al Thani, A. A., Al Ansari, K. & Yassine, H. M. Human respiratory syncytial virus: pathogenesis, immune responses, and current vaccine approaches. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.: Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 1817–1827 (2018).

Wen, X. et al. Structural basis for antibody cross-neutralization of respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus. Nat. Microbiol 2, 16272 (2017).

Sesterhenn, F. et al. De novo protein design enables the precise induction of RSV-neutralizing antibodies. Science (New York, N.Y.) 368 (2020).

McLellan, J. S. et al. Structure of a major antigenic site on the respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein in complex with neutralizing antibody 101F. J. Virol. 84, 12236–12244 (2010).

Chang, L. A. et al. A prefusion-stabilized RSV F subunit vaccine elicits B cell responses with greater breadth and potency than a postfusion F vaccine. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eade0424 (2022).

Drysdale, S. B. et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of hospitalizations due to RSV in infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 2425–2435 (2023).

Falsey, A. R. et al. Efficacy and safety of an Ad26.RSV.preF-RSV preF protein vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 609–620 (2023).

Swanson, K. A. et al. A respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) F protein nanoparticle vaccine focuses antibody responses to a conserved neutralization domain. Science Immunology 5 (2020).

Sacconnay, L. et al. The RSVPreF3-AS01 vaccine elicits broad neutralization of contemporary and antigenically distant respiratory syncytial virus strains. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadg6050 (2023).

Joyce, M. G. et al. Iterative structure-based improvement of a fusion-glycoprotein vaccine against RSV. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 811–820 (2016).

Krarup, A. et al. A highly stable prefusion RSV F vaccine derived from structural analysis of the fusion mechanism. Nat. Commun. 6, 8143 (2015).

Mascola, J. R. & Fauci, A. S. Novel vaccine technologies for the 21st century. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 87–88 (2020).

Browne, S. K., Beeler, J. A. & Roberts, J. N. Summary of the vaccines and related biological products advisory committee meeting held to consider evaluation of vaccine candidates for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease in RSV-naïve infants. Vaccine 38, 101–106 (2020).

Acosta, P.L., Caballero, M.T. & Polack, F.P. Brief History and Characterization of Enhanced Respiratory Syncytial Virus Disease. Clin. Vaccine. Immunol. 23, 189–95 (2015).

April M, K., Masaru, K. & Barney S, G. Pre-fusion F is absent on the surface of formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus. Sci. rep. (2016).

Che, Y. et al. Rational design of a highly immunogenic prefusion-stabilized F glycoprotein antigen for a respiratory syncytial virus vaccine. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eade6422 (2023).

Hsieh, C. L. et al. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized human metapneumovirus fusion proteins. Nat. Commun. 13, 1299 (2022).

Gonzalez, K. J. et al. A general computational design strategy for stabilizing viral class I fusion proteins. Nat. Commun. 15, 1335 (2024).

Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Sci. (N. Y., N. Y.) 367, 1260–1263 (2020).

Pallesen, J. et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E7348–e7357 (2017).

Marcandalli, J. et al. Induction of potent neutralizing antibody responses by a designed protein nanoparticle vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus. Cell 176, 1420–1431.e1417 (2019).

Crank, M. C. et al. A proof of concept for structure-based vaccine design targeting RSV in humans. Sci. (N. Y., N. Y.) 365, 505–509 (2019).

Sanders, R. W. & Moore, J. P. Virus vaccines: proteins prefer prolines. Cell host microbe 29, 327–333 (2021).

Hsieh, C. L. et al. Structure-based design of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spikes. Sci. (N. Y., N. Y.) 369, 1501–1505 (2020).

Flynn, J. A. et al. Stability Characterization of a vaccine antigen based on the respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein. PloS one 11, e0164789 (2016).

Jones, H. G. et al. Alternative conformations of a major antigenic site on RSV F. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007944 (2019).

Gilman, M. S. et al. Characterization of a prefusion-specific antibody that recognizes a quaternary, cleavage-dependent epitope on the RSV fusion glycoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005035 (2015).

Mousa, J. J., Kose, N., Matta, P., Gilchuk, P. & Crowe, J. E. Jr A novel pre-fusion conformation-specific neutralizing epitope on the respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16271 (2017).

Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. cell Biol. 23, 3–20 (2022).

Huang, Q., Han, X. & Yan, J. Structure-based neutralizing mechanisms for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Emerg. microbes Infect. 11, 2412–2422 (2022).

Huang, Q., Zeng, J. & Yan, J. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. J. Genet. genomics = Yi chuan xue bao 48, 107–114 (2021).

Walsh, E. E. et al. Efficacy and safety of a bivalent rsv prefusion F vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1465–1477 (2023).

Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403–416 (2021).

Barbier, A. J., Jiang, A. Y., Zhang, P., Wooster, R. & Anderson, D. G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 840–854 (2022).

Mercado, N. B. et al. Single-shot Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature 586, 583–588 (2020).

Yu, J. et al. DNA vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Sci. (N. Y., N. Y.) 369, 806–811 (2020).

Huang, Q. et al. A single-dose mRNA vaccine provides a long-term protection for hACE2 transgenic mice from SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 12, 776 (2021).

Lin, M. et al. A truncated pre-F protein mRNA vaccine elicits an enhanced immune response and protection against respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Commun. 16, 1386 (2025).

Snape, M. D. et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of an mRNA-Based Rsv Vaccine and an Rsv/hMPV Combination Vaccine in Children 5 to 23 Months of Age. Preprints (2024).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the staff from the BL10U2 beamline at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China) for assistance during X-ray diffraction data collection. We are grateful to the staff from Biochemical and Molecular Platform of Changping Laboratory for their assistance during protein purification and characterization. We thank X. Lan (China CDC) for assistance with cotton rat experiments. We thank Dr. Junfeng Hao (Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Dr. Yu Kuang (China Agricultural University) for lung tissue histopathological evaluation. This project is financially supported by Changping Laboratory (Grant No. 2022A-03-05 to J.H.Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.H. initiated and designed the study. J.Y. supervised the study. Q.H. designed the proline-scanning methodology and antigen optimization strategy, while Q.L., L.L., X.C., and Y.S. conducted the corresponding experiments. X.D. and F.W. prepared RSV viruses. Q.L., F.W., Y.L., and L.L. conducted microneutralization assays. Q.H. and L.Z. analyzed the neutralization data. Y.L., Y.X., Q.L., X.D., and Y.B. conducted the animal experiments. Q.L. and X.C. grew the antigen crystals. X.H. and Y.W. collected the diffraction data and determined the structure. Q.H., J.Y., X.H., L.B., and C.G. analyzed the animal protection efficacy data. Q.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. J.Y. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.Y. and Q.H. are inventors on patents No. PCT/CN2023/122155 and PCT/CN2023/122160. These patents do not restrict the publication or availability of the data presented in this study. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jorge Blanco, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions