Abstract

The Amazon rainforest is one of Earth’s most diverse ecosystems, playing a key role in maintaining regional and global climate stability. However, recent changes in land use, vegetation, and the climate have disrupted biosphere-atmosphere interactions, leading to significant alterations in the water, energy, and carbon cycles. These disturbances have far-reaching consequences for the entire Earth system. Here, we quantify the relative contributions of deforestation and global climate change to observed shifts in key Amazonian climate parameters. We analyzed long-term atmospheric and land cover change data across 29 areas in the Brazilian Legal Amazon from 1985 to 2020, using parametric statistical models to disentangle the effects of forest loss and alterations of temperature, precipitation, and greenhouse gas mixing ratios. While the rise in atmospheric methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) mixing ratios is primarily driven by global emissions (>99%), deforestation has significantly increased surface air temperatures and reduced precipitation during the Amazonian dry season. Over the past 35 years, deforestation has accounted for approximately 74% of the ~ 21 mm dry season−1 decline and 16.5% of the 2°C rise in maximum surface air temperature. Understanding the interplay between global climate change and deforestation is essential for developing effective mitigation and adaptation strategies to preserve this vital ecosystem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Amazon rainforest plays a key role in the Earth’s hydrological, energy, and carbon cycles1,2,3. It is a highly biodiverse environment4, and influences weather patterns and climate conditions on a continental scale5,6,7. As the largest tropical forest on Earth, the biome stores between 150 and 200 billion tons of carbon above and below the ground8,9, and it has acted as a major sink for carbon dioxide (CO2)10,11. Over the last decades, however, parts of the forest have become carbon sources rather than carbon sinks, and droughts appear to be a key driver in this transformation10,12,13,14. Accordingly, the impact of climate change and deforestation on the water cycling in the Amazon has been carefully investigated15,16,17,18. Recent studies have further highlighted how ocean–atmosphere teleconnections modulate carbon assimilation and evapotranspiration dynamics across South America’s major biomes, including the Amazon, at seasonal to interannual scales19,20. These findings emphasize the need to contextualize Amazonian carbon and water fluxes not only in terms of local land-use changes but also in large-scale climate drivers. Of the nine processes identified as critical for Earth system stability21, five with the most critical status, namely climate change, biosphere integrity, land system change, freshwater change, and biogeochemical flows, are significantly influenced by the Amazonian Basin, particularly at regional to continental scales.

The increase in CO2 and other anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHG) in the Earth’s atmosphere is warming the planet and generating feedbacks that alter the global climate. This effect will henceforth be referred to as Global Climate Change. A temperature increase of about 0.15 °C per decade has been observed in Amazonia since 1950, along with an increase in dry season length by 6.5 days per decade22. Highly deforested areas experience a dry season five weeks longer compared to 197923. Further increases in dry season length might trigger positive feedback between enhanced flammability of the vegetation, resulting in an intensified fire regime, a perturbed hydrological cycle, as well as an increased vulnerability of the forest to droughts and fires24,25,26. Recent studies have also evaluated how climate and land use changes jointly affect other environmental variables such as hydrology. For instance, Cavalcante et al.27 assessed the Itacaiúnas River Basin and found that climate variability and deforestation have opposite effects on streamflow. Similarly, Panday et al.28 demonstrated similar patterns in the Xingu River Basin using a combination of satellite observations and modeling approaches. These findings highlight the complexity and scale dependence of interactions between climate change, deforestation, and hydrological responses in the Amazon.

Deforestation, forest degradation, and wildfires significantly alter the Amazon’s climate, which has far-reaching consequences for the global climate system29,30. The Amazon Basin covers about 59% of the territory of Brazil, spanning around 5 million km2. From 1985 to 2020, there was a significant drop in forest cover, from 89.1% to 78.7%, while pastureland increased from 4.2% to 14.8%31. Deforestation directly affects precipitation rates and spatial patterns, and the forest’s ability to remove CO232,33,34,35,36,37,38. Together, human activities associated with land use change and global climate change are disrupting the natural balance of the ecosystem, leading to a range of environmental impacts that affect both the region and the whole planet15,16,17,39. The impact of climate change on the Amazon rainforest and its potential for carbon release raises concerns for the global climate system feedback loop18. Particularly, deforestation has a substantial impact on the regional climate of Amazonia5,22,32,40,41. Although previous studies have investigated the combined effects of deforestation and climate change in specific subregions or watersheds27, the relative roles of deforestation and global climate change and their interaction in driving the transformation of the Amazon remain poorly understood and have yet to be disentangled25,42.

In this study, we use observational/reanalysis and remote sensing data to quantify the effects of 35 years of deforestation and global climate change on the regional climate in Brazil’s Legal Amazon (BLA). The datasets used, along with their spatial and temporal coverage, are summarized in Table 1. The BLA was chosen because it corresponds to the official jurisdiction used in Brazil’s environmental policy and monitoring frameworks (e.g., MapBiomas43), and because high-resolution, long-term land use data are reliably available for this territory. Moreover, the BLA encompasses the majority of the Amazon biome within Brazil, where deforestation has been most intense and extensively monitored. A comprehensive assessment of the long-term trends of key climatic variables allowed us to quantify changes and determine the relative contributions from the driving forces.

Results

Quantifying global and regional effects across Brazilian Amazon areas

To disentangle the regional effects of deforestation from the global effects of climate change in the Brazilian Amazon, data on 29 areas of ~300 × 300 km2 between 1985 and 2020 were considered. Deforestation is defined here based on the MapBiomas land cover classification as any loss of native forest vegetation, regardless of the resulting land use class. The particular area size was selected for two reasons. First, they encompass a sufficiently large area to represent the observed path length of deforestation, as indicated by previous studies38, and have recently been adopted in similar spatial analyses of Amazonian land cover dynamics44. This ensures that the effects of deforestation within a given region are adequately captured and analyzed. Second, the dimension of ~90,000 km2 is within the mesoscale range, encompassing atmospheric phenomena like thunderstorms, squall lines, and deep convection, which are characterized by radii between 75 and 150 km45. The 29 areas were chosen to maximize spatial coverage of the BLA while excluding areas dominated by water bodies or permanent wetlands, ensuring reliable surface climate and land cover analysis. To assess the robustness of our findings across different spatial scales, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using smaller grid sizes (50 × 50, 100 × 100, and 200 × 200 km2). The results, shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, indicate that the long-term trends in temperature and precipitation remain consistent across scales, reinforcing the suitability of the 300 × 300 km2 resolution adopted in this study. However, greater variability during the dry season suggests a slight scale dependency for the precipitation in the analysis.

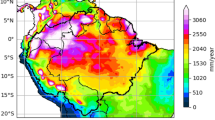

Figure 1 presents the 29 areas analyzed within the BLA. The land-use classification (see Methods for a detailed description) for 1985 (a) and 2020 (b) is overlaid on the areas, providing a clear representation of the deforestation that has occurred in each area over time. The northwest areas of the Amazonian region stand out due to their high fraction of natural forest cover. In contrast, the southern and eastern areas face alarming levels of deforestation, commonly referred to as the arc of deforestation. The deforestation fraction for each area (Supplementary Fig. S2) varies significantly across the 29 areas. Upon analyzing the variation in forest cover across areas, it was determined that the 75th and 25th quantiles of vegetation loss corresponded to 19% and 0.6%, respectively. These findings underscore the substantial spatial variation in the extent of deforestation across different regions.

The green areas represent forest cover as defined by MapBiomas, corresponding to regions with intact native vegetation. Non-forest land covers are represented in yellow, red, and beige tones, encompassing pasture and agriculture, urban areas, and natural non-forest formations, respectively. Water bodies are displayed in blue. The black line delineates the boundary of the BLA, and the black squares represent the 29 fixed grid cells (each ~300 × 300 km2) selected for our analysis. These regions were selected to assess the relative impact of deforestation and global climate change on dry season temperatures, precipitation, and GHG mixing ratios. The figure illustrates widespread forest loss over the past 35 years, particularly in the southeastern portion of the Amazon.

Deforestation and global climate change effects

We collected time series data for average methane (CH4) and CO2 mixing ratios, maximum surface air temperature (Tmax), and average cumulative monthly rainfall for each area. The maximum surface air temperature was used because it provides the clearest and most statistically significant indication of the impact of deforestation compared with the minimum and mean air temperatures. A summary of datasets used, including their resolution and coverage, is provided in Table 1. The deforestation dataset spans the period from 1985 to 2020; however, each variable dataset covers a different time interval, as described in Table 1. This analysis is based on long-term remote sensing and reanalysis datasets, including MapBiomas (land cover), ERA5 (temperature), GPM (precipitation), AIRS (CH4), and OCO-2 (CO2). A detailed description is provided in the Section “Methods”. Each variable dataset shows a distinct pattern of change over the years, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Deforestation and global climate change influence rainfall, temperature, and GHG mixing ratios in distinct ways across the wet and dry seasons14,46,47. However, several studies have shown that the regional climatic impacts of deforestation are more pronounced and meaningful during the dry season, when the forest is more vulnerable to moisture deficits and surface–atmosphere interactions are intensified. In our analysis, the dry season consistently exhibited stronger correlations between deforestation and key climate variables, including maximum temperature and precipitation (see Supplementary Fig. S4), while the wet season showed weaker and often statistically insignificant relationships (see Supplementary Fig. S5). Therefore, our study focuses exclusively on the dry season to isolate and quantify the climatic effects of deforestation with greater precision. A detailed explanation and supporting statistical evidence are provided in the “Methods”, subsection “Definition of wet and dry season, and data processing”.

Our analysis indicates that the relationship between the variable and time is linear, while the relationship with deforestation follows a logarithmic pattern. For example, the analysis of the maximum daily temperature (Fig. 2) shows that during the dry season, these two distinct processes exhibit a nearly linear temporal trend across all deforestation extensions, which is attributed to global climate change, as evidenced by the gradual increase in maximum temperature over the years. Additionally, a logarithmic effect of deforestation is observed, irrespective of the year, whereby an extension in the deforestation area corresponds to a rise in daily maximum temperature. The other atmospheric variables considered in this study (CO2, CH4, and precipitation) also exhibited meaningful variability associated with both long-term global trends and/or regional deforestation (see Supplementary Fig. S4). Regional deforestation patterns strongly modulate dry season precipitation, and the mixing ratios of GHG (CO2 and CH4) exhibit clear long-term trends, primarily driven by global changes. In general, variables more strongly influenced by global climate change exhibited smoother temporal increases, while those sensitive to land cover change responded more directly to deforestation. Three distinct patterns emerge: variables with a clear long-term trend and a weaker influence of deforestation (CH4 and CO2 mixing ratios), a variable sensitive to deforestation and long-term trends (maximum surface air temperature), and a variable with a strong dependence on deforestation and a weak long-term trend (rainfall).

In panel a, data points are colored by deforestation percentage, and a linear fit is applied (R = 0.47, p < 0.05). In panel b, data points are colored by year, and a logarithmic fit is applied (R = 0.63, p < 0.05). Both relationships are statistically significant. The yellow lines represent the fitted linear (a) and logarithmic (b) models.

We assessed the impacts of regional and global contributions of these parameters during the dry season by fitting linear and logarithmic equations to the dataset. More details are presented in the Section “Methods”. These results contrast with a recent study, which reported a linear response of temperature to deforestation48. However, their analysis does not disentangle climate change’s contribution from deforestation, which our findings indicate is essential for capturing the nonlinear response. By isolating the effects of deforestation, we demonstrate that temperature increases with forest loss logarithmically, emphasizing the distinct role of land-use changes in modifying regional climate. This interplay is explored in detail in the following sections, where we disentangle the respective contributions of time and forest loss to the observed patterns.

Modeling the evolution of atmospheric variables

To assess the effects of deforestation and global climate change on GHG mixing ratios and weather variables, we developed an approach that integrates linear temporal trends with the exponential trends associated with deforestation. These effects interact non-linearly due to the interdependence of deforestation (D) and time (t). As detailed in section Methods, we obtained a parametric equation (Eq. (4)) that incorporates the linear time dependence, the logarithmic dependence on deforestation, and their nonlinear interactions. The parameters of Eq. (4) were obtained by fitting observational data to separately capture the contributions of deforestation and global influence to observed changes in climate variables.

Using the parameterized equation, we effectively isolated the individual effects of global emissions and deforestation on changes in GHG mixing ratios and weather parameters. This was achieved by differentiating Equation (4) with respect to time and deforestation, holding either deforestation or time constant, allowing us to distinguish the unique contributions of global climate forcing and deforestation dynamics. Integrating the derived equations for time and deforestation enabled us to quantify the specific contributions of deforestation and global climate change to the observed variations over the 35 years. To account for regional variation, we applied the parameterized equation individually to all 29 studied areas, each covering 300 × 300 km2. While our primary results present Amazon-wide averages, we also present regional distributions in a box plot, including the statistics for all areas. Further details on the equation formulation and parameter definitions can be found in the “Methods”, subsection “Derivation of parametric fits and calculations of deforestation and global contributions”.

Supplementary Figure S6 presents the fitted three-dimensional surfaces that depict how each climate variable responds to both time (year) and the fraction of deforestation, as modeled by Eq. (4). These visualizations offer complementary insight into the nonlinear interactions captured by our approach. The parametric formulations used to construct these surfaces are provided in Table 2 and serve as the foundation for disentangling the respective contributions of global climate change and regional deforestation. To assess the model’s performance, we evaluated the quality of the fit for each variable, which is also shown in Table 2. In addition, Supplementary Figure S7 presents the correlation coefficients individually for the linear and logarithmic contributions, showing that the dry season fits were statistically significant, with confidence levels above 95%, unlike those observed for the wet season. All fits were statistically robust (p < 0.05) and showed strong correlation coefficients (R ≥ 0.69), confirming the reliability of our approach.

Disentangling the influence of deforestation and climate change

Although each variable dataset covers a different period, as shown in Table 1, the fitted equations enable us to extrapolate all analyzed variables to the same period, from 1985 to 2020, which is the period covered by the land use dataset. This extrapolation serves as a reference for understanding the variation of GHG mixing ratio, temperature, and precipitation over the same range of years. Figure 3 presents the overall changes calculated over the 35-year period, as well as the specific contributions from global climate change and deforestation. All calculations were conducted exclusively for the dry season. The boxplots, based on data from all 29 regions, offer a robust statistical summary across the Amazon biome. Median percentage contributions are shown next to the bars, while the deltas indicate the average change observed for each variable. Notably, the relatively short lengths of the boxplots for GHG mixing ratios reflect much lower variability in their contributions compared to those of the meteorological variables.

Boxplots of the deforestation and global climate change contributions to methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), maximum surface temperature, and total precipitation during the dry season between 1985 and 2020, considering individually each of the 29 areas. Values near the bars indicate the median contributions, while deltas at the top of the chart denote the variable’s mean value.

For the gas mixing ratios, CO2 and CH4 exhibited notable increases of approximately 87 ppm and 173 ppb, respectively. Additionally, the maximum surface air temperature experienced a rise of ~2 °C, while the total precipitation during the dry season decreased by about 21 mm dry season−1, on average. By using our parametric equations, we estimated the individual contributions of deforestation and climate change to the observed variabilities. The modulation of the maximum surface air temperature is intricately shaped by the dual influence of global climate change, which exhibits a discernible linear rise over successive years, and the impact of land use transformations resulting from the conversion of forests into pasture and agricultural areas. Separating the distinct influences of regional and global factors reveals that deforestation in the Amazon region resulted in a rise of 0.39 °C in the average daily maximum temperature over 35 years, corresponding to ~16.5% of the total contribution. While this value represents the mean across all study areas, the variation in maximum temperature in the study area with the highest percentage of deforestation (28.5%) reaches values as high as 1.25 °C. In contrast, the more comprehensive effects of global influences contributed to a temperature increase of 1.63 °C, corresponding to 83.5% of the 2.0 °C observed temperature increase. These results highlight that the observed increase in maximum temperature during the dry season cannot be attributed solely to global climate change or deforestation. Instead, it reflects a synergistic interaction in which long-term global warming amplifies the sensitivity of local climate to land-use change, while deforestation intensifies regional heating and reduces evapotranspiration, further exacerbating the warming trend.

These results align with previous observational studies. For instance, Gatti et al.14 reported that regions in the eastern and southeastern Amazon, where deforestation is most intense, exhibited stronger warming trends and carbon release compared to more preserved western regions. This spatial differentiation, which is supported by Supplementary Fig. S8, reinforces our findings that deforestation contributes disproportionately to regional temperature increases. While prior work did not explicitly separate regional and global contributions, our study builds on these patterns by providing a first-order quantification of their respective roles in shaping temperature and rainfall trends across the Amazon basin.

Related to precipitation, our findings reveal that the reduction in forest cover results in a 15.8 mm decrease in precipitation per dry season in the Amazon region, constituting 74.5% of the overall effect. On the other hand, global climate change contributes to a reduction of 5.2 mm in precipitation per dry season, representing 25.6% of the total effect. These results highlight the substantial impact of deforestation on the rainfall regime in the Amazon, with the primary effect occurring during the dry season. Recent studies estimated a 3 mm yr−1 reduction in rainfall for every percentage point decrease in forest cover38. Based on this rate, the decrease in forest cover from 89.1% to 78.7% reported in our study, during the 35 years, would correspond to a rainfall reduction of approximately 30 mm, during the whole year, not far from our calculation only for the dry season. As previously stated, these numbers represent the average for the entire Amazon region. However, when considering the study area with the highest percentage of deforestation (28.5%), there is a discernible rainfall reduction that could reach values of around 50.5 mm during the dry season. Numerous studies have examined the complex changes in rainfall patterns resulting from deforestation, global climate change, or the combined effects of both factors49. In addition, previous research showed the different seasonal impacts of deforestation on cloud cover50 while highlighting the distinct influences of deforestation and climate change on the rainfall regime51. Shallow clouds predominate in deforested areas, while deep convection is favored in forested surfaces52.

Considering the GHG mixing ratios, CO2 has global effects that drive the overall variability and contribute to an approximately 87 ppm increase in mixing ratio over the 35 years modeled. For methane, the mean contributions of the effects of deforestation and global change were of the same order, 0.1% and 99.9%, respectively. Considering the total background mixing ratio, on average, the regional influence resulted in a small increase in the total methane mixing ratio, while the global influence contributed to a change of ~173 ppb. When we apply the model to describe the regional effect over the highest deforestation fraction (28.5%), the mixing ratio changed by around 0.83 ppm, giving a maximum regional change of around 6.9%, which is greater than the average effect. The same reasoning can be applied to analyzing the maximum regional fluctuation in the CH4 mixing ratio. After subtracting the background mixing ratio, methane levels changed by approximately 75 ppb over the 35-year data period, and by around 0.80 ppb between the two hotspots of forest and deforestation. On average, methane varies by around 0.12%, but locally it can reach values of up to 1.06%.

Since GHGs have a long residence time in the atmosphere, their mixing ratios vary slowly and smoothly in space and time in all areas. The fact that the GHG observational data refer to the troposphere also contributes to the smooth variation in mixing ratio. As highlighted in the Introduction section, certain regions within the Amazonian basin may no longer act as carbon sinks but have likely become carbon sources due to deforestation, affecting the net ecosystem exchange (NEE) and eddy covariance fluxes. However, it is worth noting that GHG mixing ratios are disconnected from NEE53. The changes in CO2 mixing ratios are relatively modest, ranging from 2 to 4 ppm14,53, which translates to less than 1% of the total CO2 mixing ratio. Removing the background mixing ratio, the change in mixing ratio over the 6 years analyzed with satellite data changed by about 12%.

Discussions

Preserving Amazonia’s forest cover: anticipating future impacts

As illustrated in Fig. 4, our results demonstrate the distinct influence of global climate change and regional land-use change on Amazonian climate dynamics. Deforestation plays a dominant role in modulating meteorological variables during the dry season. On average, it accounts for 16.5% of the observed increase in maximum daily temperature (~0.40 °C) and 74.5% of the reduction in dry season precipitation (a net loss of 15.8 mm dry season −1). In contrast, GHG mixing ratios were predominantly influenced by global factors, with deforestation exerting only a minor effect. These findings provide a foundation for exploring how continued forest loss may intensify regional climate disruption in the coming decades. Thus, we examine potential future scenarios based on recent trends in deforestation and discuss their implications for Amazonian resilience and climate feedbacks.

Our findings show that the most pronounced climate impacts occur early in the deforestation process, within the first 10–40% of forest cover loss. This nonlinear response suggests a steep initial degradation of local climate regulation functions. While further deforestation continues to alter the climate, the marginal impact becomes less dramatic after this threshold. It underscores the disproportionate importance of preserving existing forest areas before they cross these critical initial loss intervals. Comparisons between the least and most deforested areas further reinforce this aspect: regions that have retained more forest cover show greater climate stability, while those with extensive land cover conversion exhibit intensified warming and drying trends (see Supplementary Fig. S8). These results emphasize that avoiding even early-stage deforestation is essential for safeguarding the biome’s meteorological resilience and minimizing future disruptions to rainfall and temperature patterns.

The observed changes in the rainfall and maximum temperature can potentially change the Amazonian climate. Using the developed parametric equations (Table 2) we extrapolated the effect of the next 15 years considering the maintenance of deforestation rates in the last five years (2016–2020) so that the deforested areas, obtained with linear regression with the deforestation data from the referred period, would reach a fraction of 32.4% in 2035 (here, considering the rate obtained from the 29 areas). In this scenario, CO2 and CH4 mixing ratios would increase by 36.7 ppm and 78 ppb, respectively; the maximum surface temperature would also rise by about 0.62 °C, and total rainfall would decrease by 7.3 mm per dry season. Therefore, compared to 1985 values, in 2035, the Amazonian region is expected to experience a total temperature increase of 2.64 °C, with rainfall reduced by 28.3 mm per dry season, and GHG mixing ratios increased by 123.3 ppb for CO2 and 250.8 ppb for CH4.

While our findings suggest trends consistent with early signs of biome destabilization, we acknowledge that our analytical approach based on statistical extrapolation has limitations in its ability to capture dynamic feedbacks, threshold responses, or ecological resilience mechanisms. However, by disentangling historical contributions of deforestation and global climate change, our method offers a valuable first-order assessment of likely trajectories if current trends persist. While limited, this approach provides a preliminary indication of the risks associated with ongoing deforestation and climate stressors in the Amazon.

The Northeast region of Brazil, a semi-arid region, lies east of the Amazon rainforest and features a “zona da mata" near the coast, characterized by considerable rainfall. At the same time, the Caatinga biome extends further inland and is characterized by semi-arid conditions, with large seasonality and a short wet season. The Cerrado, located directly south of the Amazon rainforest, has a climate characterized by high seasonality, with distinct wet and dry seasons, during which there are typically few rainy days. The typical climate of the Caatinga and Cerrado biomes differs in terms of vegetation cover, the duration of the dry season, and total rainfall. Although it is uncertain whether deforestation in the Amazon will result in the replacement of the forest by Cerrado or Caatinga because changes in the biome are complex and do not depend exclusively on the climate, our results strongly indicate that deforestation processes are escalating exponentially, leading the Amazonian climate towards a potential climate transformation into a Cerrado-climate type or even worse, a Caatinga semi-arid climate type.

Summary

In this study, we examined 35 years of environmental data to disentangle the effects of deforestation and global climate change on key atmospheric variables in the Brazilian Amazon. The analysis reveals that year-to-year variations exhibit a linear trend, while a logarithmic function accurately describes the effect of deforestation. Surface parametric equations considering both yearly and logarithmic variations as a function of deforestation were successfully derived from atmospheric parameters. These parametric equations enable the separation of the specific contributions of global climate change and deforestation extension to the observed changes over the 35-year period for each variable. The dry season is when the impacts of deforestation are most pronounced, mainly on rainfall. The cumulative effects ultimately exacerbate the seasonality even further.

Over the entire 35-year period, there was an increase of around 87 ppm in the mixing ratio of CO2. About all of this increase can be attributed to global emission changes, with a small portion due to the extent of deforestation. A similar tendency was observed for CH4. This gas increased by around 167 ppb, of which 99.9% was attributed to global emission change. If the background mixing ratio is not considered, vegetation’s contribution to changes in gas mixing ratios is relatively much more important. The maximum surface air temperature exhibited a rise of approximately 2.0 °C, with global climate change and the deforestation effect contributing 83.6% and 16.5%, respectively. The total precipitation during the dry season showed a reduction of about 21 mm dry season−1, with deforestation contributing to a decrease of ~15.8 mm dry season−1 (74.5%) and global climate change leading to a decrease of ~5.2 mm dry season−1 (25.5%).

Overall, these findings highlight the intricate relationship between deforestation and global climate change in influencing rainfall patterns across the Amazon. This interaction contributes to nonlinear trends in precipitation, amplifying the impacts of ongoing climate change. The observed reduction in total precipitation during the dry season, combined with a significant increase in maximum surface temperature linked to deforestation, underscores the crucial role of forest cover in maintaining a stable regional water cycle and mitigating climate stress. If deforestation continues unabated, the extrapolation of our results suggests a further decline in total precipitation during the dry season and an increase in maximum surface temperature, factors that could push the Amazon ecosystem toward increasingly unstable states. Emerging evidence suggests that deforestation in the Amazon is already altering South American monsoon patterns, resulting in drier conditions that may compromise the long-term resilience of the rainforest47,54.

In addition, the results of this study suggest that Amazon is moving through a critical transition, potentially exacerbated by extreme events such as the unprecedented 2023 drought55,56. However, we remain cautious about defining a precise deforestation threshold that could trigger biome-scale dieback, particularly because our extrapolation does not fully account for the substantial uncertainties inherent in climate-vegetation interactions, which themselves remain subject to significant uncertainty57. Together, deforestation and climate change are driving substantial transformations across the region during the dry season, resulting in reduced rainfall, elevated temperatures, and increased atmospheric GHG levels. These findings underscore the importance of maintaining and restoring forest cover in the Amazon as a crucial strategy for mitigating climate change and ensuring the stability of ecosystems.

Methods

Land use and land cover data

The land use and land cover (LULC) data were obtained from the MapBiomas Project43, an initiative dedicated to monitoring and mapping changes in LULC throughout Brazil. The MapBiomas platform effectively collects and processes extensive geospatial data from various sources, including satellite imagery captured by different sensors. By implementing advanced classification and analysis algorithms, it identifies and maps alterations in land cover over time. MapBiomas has generated Brazil’s most detailed, up-to-date, and longest time series of LULC mapping. We used Collection 6.0 from MapBiomas for this study. This collection comprises maps with an annual temporal resolution covering the period from 1985 to 2020. The spatial resolution of the data is 30 m based on Landsat satellite images. The global accuracy of the MapBiomas Collection 6 land-use and land-cover maps stands at 87.4%. These datasets are available on Google Earth Engine as a data asset and can be freely accessed through the platform’s website at https://brasil.mapbiomas.org (accessed June 19, 2022).

In our analysis, deforestation is defined as the conversion of areas classified as “forest" in MapBiomas to any other land cover class, including agriculture, pasture, urban areas, water bodies, or natural non-forest formations. This inclusive definition encompasses all transitions that lead to forest loss, regardless of the subsequent land use. Our estimates of deforestation do not consider specific transitions (e.g., forest-to-agriculture or forest-to-mining). Deforestation fractions were calculated as annual averages within each of the 29 study areas, based on the percentage of forest cover loss relative to the initial forest area in 1985. We emphasize that the analysis focuses on the Brazilian Legal Amazon (BLA), rather than the full Amazon biome, due to the availability and consistency of spatially explicit deforestation and land cover data provided by MapBiomas, which is optimized and validated within Brazilian territory. While the Amazon biome extends beyond Brazil’s borders, the BLA encompasses the vast majority of its forest area under national jurisdiction and includes the regions experiencing the highest rates of deforestation. As such, it provides a policy-relevant and analytically consistent domain for our regional climate assessment.

Definition of wet and dry seasons, and data processing

Our analysis evaluated the dry and wet seasons separately to assess the seasonal impact of deforestation on each variable. Given the spatial heterogeneity of seasonal cycles across the Amazonian region, we categorized the dry and wet season months based on the 25th and 75th percentiles of the total integrated rainfall (see Supplementary Fig. S9). The wet and dry seasons were determined by analyzing the precipitation patterns specific to each area within the Amazon region. A comprehensive analysis of the entire time series for each area was conducted to derive an average precipitation annual cycle. To study the whole period, we used data from ERA5 from 1985 to 2020. The objective was not to quantify rainfall amounts, but to describe the distinct seasonal variations in precipitation patterns, which are accurately depicted by the ERA5 dataset. The 75th quartile, representing months with the highest annual rainfall, was identified as the wet season. In contrast, the 25th quartile, representing months with the lowest total rainfall, was designated as the dry season. It is worth noting that the composition of each quartile may vary across the Amazon. Based on quartiles, this methodology ensures an objective approach to defining the seasons. Thus, the dry and wet season data were computed for each time series and obtained based on the 25th and 75th quartiles, respectively, and their annual averages for each area. This was necessary to ensure accurate comparisons regarding the change in forest cover.

We evaluate the sensitivity of deforestation to rainfall, temperature, and trace gas mixing ratios by applying wet and dry season classifications across the 29 study regions. Statistically significant trends emerge predominantly during the dry season. In this period, the relationship between deforestation and climatic variables is particularly strong, with median correlation coefficients of R ~0.75 for maximum temperature and R ~0.70 for rainfall. In contrast, during the wet season, these correlations decline substantially to R ~0.50 and R ~0.30, respectively, and most trends are not statistically significant. Supplementary Figures S4 and S5, along with Fig. 2 (which illustrates the evolution of dry-season temperature), present scatter plots for both seasons, highlighting the seasonal contrasts.

Deforestation disrupts the natural modulation of the water and energy cycles, leading to reduced rainfall and elevated surface temperatures, particularly during the dry season, in line with previous findings47. The linear component of our model, representing the influence of large-scale climatic drivers, shows consistently high correlation coefficients for CO2 and CH4 (R > 0.90) in both seasons, suggesting that variations in GHG mixing ratios are primarily governed by global-scale processes and are relatively insensitive to local deforestation. In contrast, the logarithmic component, capturing the regional-scale effects of deforestation, exhibits marked seasonal variability.

These findings confirm that the climatic impacts of deforestation are most pronounced during the dry season, offering a more distinct and statistically robust signal of its regional influence. Conversely, the wet season appears less responsive to local land cover changes, likely due to the overriding influence of large-scale atmospheric dynamics. Accordingly, our analysis emphasizes the dry season, where the signal of deforestation can be more accurately isolated and quantified.

Weather and greenhouse gases data

This study utilized time series data for methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), daily surface maximum air temperature, and total precipitation during the dry season for each of the 29 study areas. The datasets are summarized in Table 1. These datasets were retrieved from Google Earth Engine (GEE)58 and NASA’s Giovanni platform.

Meteorological data were obtained using custom JavaScript code within GEE. Specifically, we extracted the following products:

-

Daily surface maximum air temperature (2 m above ground level) was obtained from the ERA5 Daily Aggregates dataset, provided by the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) through the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). The dataset is available on GEE under the asset ECMWF/ERA5/DAILY and provides global coverage at a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°, spanning the period from 1979 to September 2020. Daily maximum air temperature values are derived from hourly ERA5 data and represent the highest temperature recorded at 2 m above ground for each day.

-

Total monthly rainfall data derived from the integrated multi-satellite retrievals for GPM (IMERG), Final Run version 6 product, available as the NASA/GPM_L3/IMERG_MONTHLY_V06 asset on GEE. The data provide monthly estimates of precipitation rate (in mm/h) at a spatial resolution of approximately 0. 1° (about 11 km at the equator), covering the period from 2000 to 2020. We converted the precipitation rate to total monthly rainfall (in mm/month) by multiplying the average rate by the number of hours in each month.

Greenhouse gas mixing ratios were obtained from NASA’s Giovanni platform:

-

CH4 mixing ratios were obtained from the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument aboard NASA’s Aqua satellite. We used daily Level 3 data (AIRS3STD) corresponding to the 400 hPa pressure level (upper troposphere), processed using the Standard Physical Retrieval algorithm (version 7). The data provide global coverage at a spatial resolution of 1° × 1° and include both ascending and descending orbits. Daily average CH4 values were extracted for each study region for the period 2002–202059.

-

CO2 mixing ratios were obtained from the Gridded OCO-2 product, which provides daily global maps of column-averaged CO2 dry air mole fraction (XCO2) derived from the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) satellite. Individual retrievals (Level 2) from the high-resolution spectrometer aboard OCO-2 are assimilated into the GEOS modeling system (GMAO/CoDAS) every 6 h, producing Level 3 gridded fields that smooth orbital gaps and ensure spatiotemporal consistency. The dataset is available at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.625°, covering the period from 2015 to 202060.

All datasets were first re-aggregated into monthly means for each of the 29 study regions. Based on the long-term climatological patterns, each region’s time series was then classified into wet and dry seasons, following a percentile-based threshold applied to the monthly precipitation data. This classification allowed us to capture the distinct seasonal responses of atmospheric variables to forest loss. For each season, we subsequently computed annual means, enabling a robust comparison of dry- and wet-season dynamics and a consistent assessment of long-term trends across datasets with different temporal coverage. Given the varying temporal coverage of the datasets (Tmax: 1985–2020; rainfall: 2000–2020; CH4: 2002–2020; CO2: 2015–2020), we applied our obtained parametric modeling approach (see Eqs. (7) and (8)) to reconstruct and extend the time series across the full analysis period (1985–2020). This approach allowed us to capture long-term trends and ensure temporal consistency across variables. By harmonizing datasets with different native resolutions and time spans, this framework enabled robust and consistent comparisons across variables and study regions, facilitating an integrated analysis of the impacts of deforestation and climate change.

Derivation of the parametric fits and calculations of the deforestation and global contributions

The atmospheric variables investigated in this study show a dependency on both the time and the deforestation fraction. To unravel the contributions of time and deforestation, two-dimensional functions were fit to each atmospheric variable. In the following equations, the variable y represents an atmospheric variable (CO2, CH4, the maximum surface temperature, or the rainfall), the dependent variable in the model setup. The two independent variables are time (t, in years) and the deforestation fraction (D, representing the percentage of the area that has been deforested). The influence of deforestation was modeled considering a logarithmic dependence between y and D, as exemplified in Fig. 2c. The dependent variable y, which represents any of the four atmospheric variables investigated in this study, was initially modeled with a logarithmic dependency on deforestation (D) plus a linear dependency on time (t).

where A, B, and C are coefficients fitted to the observations representing the contribution of a regional forcing related to deforestation, a global forcing related to global changes and long-term trends, and an intercept. Our analysis revealed that the coefficients A and B were not independent, as the deforestation fraction depends on time (see Fig. S4). To accurately incorporate these dependencies and account for their non-linear effects, we have extended Eq. (1) into a more comprehensive form, including, for instance, a linear variation of coefficient A and a non-linear variation of coefficient B as follows.

Rearranging the terms, we obtained a model for y(D,t) based on four parameters.

where γ = a1 + b1. This equation is referred to as Eq. (4) in the main text. Thus, four parameters are required to define Eq. (4), which was used to fit the data, considering the fraction of deforested areas and the years. The optimal fits were obtained through the least squares method. This approach resulted in a parametric surface that accurately captures the data behaviors and statistical parameters such as the p-value and correlation coefficient. These statistical measures were used to assess the quality of the data fitting.

To obtain the rates of global and regional change, we differentiate Eq. (4) while holding deforestation and year as constants. This approach allows us to isolate the distinct contributions from global influences and deforestation dynamics. To achieve this, we differentiate Eq. (4) with respect to the year, while maintaining deforestation as a constant. In addition, we differentiate Eq. (4) with respect to the logarithm of the deforested area fraction while holding the year constant. This procedure leads to the following expressions:

Then, Eqs. (5) and (6) were integrated in relation to the year and to the natural logarithm of the fraction of deforested areas, where for the first case, we kept the constant deforestation as the average value of deforestation in each one of the 29 areas from 1985 to 2020 (\(\bar{D}\)), and for the second case, we used the average year (\(\bar{t}\)) which is 2002. Then, the contribution exclusively due to the global changes is

On the other hand, the contribution exclusively due to deforestation is

Table 2 presents the fitted equations for each variable obtained for the dry season.

Data availability

The datasets presented here are available on GitHub.

Code availability

The codes used to process and analyze the data are available on GitHub.

Change history

13 October 2025

In the version of the Supplementary information initially published, the y-axis label in Supplementary Fig. 6d read "CH4 [ppb]" and has now been corrected to "Tmax [°C]". The corrected Supplementary information is now available alongside the online version of the article.

References

Machado, L. A. T. The Amazon energy budget using the ABLE-2b and FluAmazon data. J. Atmos. Sci. 57, 3131–3144 (2000).

Coe, M. T. et al. The hydrology and energy balance of the Amazon basin. In Ecological Studies, 35–53 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-49902-3_3 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016).

Artaxo, P. et al. Tropical and boreal forest atmosphere interactions: a review. Tellus 74, 24–163 (2022).

ter Steege, H. et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian tree flora. Science 342, 1243092 (2013).

Shukla, J., Nobre, C. & Sellers, P. Amazon deforestation and climate change. Science 247, 1322–1325 (1990).

Gedney, N. & Valdes, P. J. The effect of Amazonian deforestation on the northern hemisphere circulation and climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 3053–3056 (2000).

Nobre, C. et al. Science panel for the Amazon. In Executive Summary of the Amazon Assessment Report 2021, 48 (United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York, USA, 2021).

Phillips, O. L. et al. Changes in the carbon balance of tropical forests: evidence from long-term plots. Science 282, 439–442 (1998).

Saatchi, S. S. et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 9899–9904 (2011).

Brienen, R. J. W. et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519, 344–348 (2015).

Malhi, Y. et al. Chapter 6: Biogeochemical cycles in the Amazon. Amazon Assessment 312 Report 2021 (2021).

Hubau, W. et al. Asynchronous carbon sink saturation in African and Amazonian tropical forests. Nature 579, 80–87 (2020).

Basso, L. S. et al. Amazon methane budget derived from multi-year airborne observations highlights regional variations in emissions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 246 (2021).

Gatti, L. V. et al. Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change. Nature 595, 388–393 (2021).

Brienen, R. J. et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519, 344–348 (2015).

Nobre, C. A. et al. Land-use and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, 10759–10768 (2016).

Schöngart, J. et al. The shadow of the Balbina dam: a synthesis of over 35 years of downstream impacts on floodplain forests in central Amazonia. Aquat. Conserv. 31, 1117–1135 (2021).

Cox, P. M., Betts, R. A., Jones, C. D., Spall, S. A. & Totterdell, I. J. Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature 408, 184–187 (2000).

Serrão, E. A. et al. The effects of teleconnections on water and carbon fluxes in the two South America’s largest biomes. Sci. Rep. 15, 1395 (2025).

Dionizio, E. A. et al. Aboveground carbon stocks for different forest types in eastern Amazonia. Environ. Res. Commun. 7, 045006 (2025).

Richardson, K. et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh2458 (2023).

Marengo, J. A. et al. Changes in climate and land use over the Amazon region: current and future variability and trends. Front. Earth Sci. 6, 228 (2018).

Costa, M. H. & Pires, G. F. Effects of Amazon and Central Brazil deforestation scenarios on the duration of the dry season in the arc of deforestation. Int. J. Climatol. 30, 1970–1979 (2010).

Marengo, J. A. & Espinoza, J. C. Extreme seasonal droughts and floods in Amazonia: causes, trends and impacts. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 1033–1050 (2016).

Malhi, Y. et al. Climate change, deforestation, and the fate of the Amazon. Science 319, 169–172 (2008).

Andreae, M. O. et al. Smoking rain clouds over the Amazon. Science 303, 1337–1342 (2004).

Cavalcante, R., Pontes, P., Souza-Filho, P. & De Souza, E. Opposite effects of climate and land use changes on the annual water balance in the Amazon arc of deforestation. Water Resour. Res. 55, 3092–3106 (2019).

Panday, P. K., Coe, M. T., Macedo, M. N., Lefebvre, P. & de Almeida Castanho, A. D. Deforestation offsets water balance changes due to climate variability in the Xingu River in Eastern Amazonia. J. Hydrol. 523, 822–829 (2015).

Xu, X., Jia, G., Zhang, X., Riley, W. J. & Xue, Y. Climate regime shift and forest loss amplify fire in Amazonian forests. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5874–5885 (2020).

Xu, X. et al. Deforestation triggering irreversible transition in Amazon hydrological cycle. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 034037 (2022).

Morais, F. G. et al. Relationship between land use and spatial variability of atmospheric brown carbon and black carbon aerosols in Amazonia. Atmosphere 13, 1328 (2022).

Costa, M. H. & Foley, J. A. Combined effects of deforestation and doubled atmospheric CO2 concentrations on the climate of Amazonia. J. Clim. 13, 18–34 (2000).

Saatchi, S. et al. Persistent effects of a severe drought on Amazonian forest canopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 565–570 (2013).

Alencar, A. A., Brando, P. M., Asner, G. P. & Putz, F. E. Landscape fragmentation, severe drought, and the new Amazon forest fire regime. Ecol. Appl. 25, 1493–1505 (2015).

Sampaio, G. et al. CO2 physiological effect can cause rainfall decrease as strong as large-scale deforestation in the Amazon. Biogeosciences 18, 2511–2525 (2021).

Assis, T. O. et al. CO2 emissions from forest degradation in Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 104035 (2020).

Aragao, L. E. O. et al. Interactions between rainfall, deforestation and fires during recent years in the Brazilian Amazonia. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 363, 1779–1785 (2008).

Smith, C., Baker, J. & Spracklen, D. Tropical deforestation causes large reductions in observed precipitation. Nature 615, 270–275 (2023).

Gatti, L. V. et al. Increased Amazon carbon emissions mainly from decline in law enforcement. Nature 621, 318–323 (2023).

Wilson, C. et al. Large and increasing methane emissions from eastern Amazonia derived from satellite data, 2010–2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 10643–10669 (2021).

Assis, T. O., Aguiar, A. P. D., von Randow, C. & Nobre, C. A. Projections of future forest degradation and CO2 emissions for the Brazilian Amazon. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj3309 (2022).

Davidson, E. A. et al. The amazon basin in transition. Nature 481, 321–328 (2012).

Souza Jr, C. M. et al. Reconstructing three decades of land use and land cover changes in Brazilian biomes with Landsat archive and Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 12, 2735 (2020).

Teixeira, M. J. et al. Analyzing and forecasting the morphology of Amazon deforestation. For. Ecol. Manag. 586, 122662 (2025).

Machado, L. A. T. et al. Overview: Precipitation characteristics and sensitivities to environmental conditions during GoAmazon2014/5 and ACRIDICON-CHUVA. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 6461–6482 (2018).

Fu, R. et al. Increased dry-season length over southern Amazonia in recent decades and its implication for future climate projection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18110–18115 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Recent forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon causes substantial reductions in dry season precipitation. AGU Adv. 6, e2025AV001670 (2025).

Alkama, R. & Cescatti, A. Biophysical climate impacts of recent changes in global forest cover. Science 351, 600–604 (2016).

Costa, M. H. & Foley, J. A. Combined effects of deforestation and doubled atmospheric CO2 concentrations on the climate of Amazonia. J. Clim. 13, 18 – 34 (2000).

Durieux, L., Machado, L. A. T. & Laurent, H. The impact of deforestation on cloud cover over the Amazon arc of deforestation. Remote Sens. Environ. 86, 132–140 (2003).

Pielke, R. A. et al. Interactions between the atmosphere and terrestrial ecosystems: influence on weather and climate. Glob. Change Biol. 4, 461–475 (1998).

Wang, J. et al. Impact of deforestation in the Amazon basin on cloud climatology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3670–3674 (2009).

Botía, S. et al. The CO2 record at the Amazon Tall Tower Observatory: a new opportunity to study processes on seasonal and inter-annual scales. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 588–611 (2022).

Bochow, N. & Boers, N. The South American monsoon approaches a critical transition in response to deforestation. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd9973 (2023).

Rodrigues, M. The Amazon’s record-setting drought: how bad will it be? Nature 623, 675–676 (2023).

Grossman, D. A river in flux. Science 383, 692–697 (2024).

Spracklen, D. & Coelho, C. Modeling early warning signs of possible Amazon forest dieback. Sci. Adv. 9, eadk5670 (2023).

Amani, M. et al. Google earth engine cloud computing platform for remote sensing big data applications: a comprehensive review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 13, 5326–5350 (2020).

AIRS project. Aqua/AIRS L3 Daily Standard Physical Retrieval (AIRS-only) 1 degree x 1 degree V7.0. Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC). https://doi.org/10.5067/UO3Q64CTTS1U. Accessed 01-Jun-2022 (2019).

Weir, B., Ott, L. & Team, O.-. S. OCO-2 GEOS Level 3 daily, 0.5x0.625 assimilated CO2 V10r. Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC). https://doi.org/10.5067/Y9M4NM9MPCGH. Accessed 01-Jun-2022 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. Era5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) grant 2022/07974-0. MAF and MT acknowledge FAPESP projects 2021/13610-8 and 2021/12954-5, respectively, for financial support. MAF acknowledges the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) Universal project number 407752/2023-4 for financial support. LVR acknowledges CNPq for the financial support (project 304819/2022-0). We gratefully acknowledge the support of the RCGI—Research Center for Greenhouse Gas Innovation (23.1.8493.1.9), hosted by the University of São Paulo (USP) and sponsored by FAPESP—São Paulo Research Foundation (2020/15230-5). Some analyses and visualizations used in this paper were produced with the Giovanni online data system developed and maintained by the NASA GES DISC. We thank Dominic Jack from the Max Planck Institute of Chemistry for preparing the scheme representing the processes discussed in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.F. and L.A.T.M. designed the study. M.A.F. processed and analyzed the data. M.A.F. and L.A.T.M. wrote the paper. L.V.R., P.A., T.A., J.L., C.A.N., C.P., U.P., J.S., M.T., and X.X. provided valuable ideas for the data analysis and the interpretation of the results. L.A.T.M. supervised the study and coordinated the FAPESP project. P.A. coordinated the RCGI project. All authors revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Franco, M.A., Rizzo, L.V., Teixeira, M.J. et al. How climate change and deforestation interact in the transformation of the Amazon rainforest. Nat Commun 16, 7944 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63156-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63156-0

This article is cited by

-

Beyond the reporting of disturbed areas: the use of Deter to analyze the spatiotemporal patterns of forest degradation in the Amazon

Geoscience Letters (2026)

-

Observed shifts in regional climate linked to Amazon deforestation

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)