Abstract

Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs), comprising ~2500 compounds with pharmacological significance, are well-studied in Ranunculales but poorly understood in Magnoliids, an early-diverging angiosperm group. This study characterizes key enzymes in Houttuynia cordata—including 6-OMT, NMT, CYP80B, and 4’OMT—that form BIA backbones and uncovers a CYP80G-mediated phenol coupling reaction in isoboldine biosynthesis. Functional analysis reveals conservation of BIA backbone formation genes between Magnoliids and Ranunculales, with evidence of gene duplication and neofunctionalization in H. cordata. Genome-wide analysis identifies dynamic clustering of CYP80B with 4’OMT and 6-OMT genes across angiosperms, reflecting their interlinked biochemical roles in the formation of BIA backbones. These findings suggest that such gene clustering may evolved through biochemical coordination, offering insights into the evolutionary mechanisms behind plant gene cluster formation. The study provides a foundation for understanding BIA biosynthesis across flowering plants and supports synthetic biology strategies to produce high-value BIAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIAs) are a diverse group of approximately 2500 compounds with significant pharmacological properties, including analgesic, antiseptic, and antineoplastic effects1. These compounds are primarily found in early-diverging eudicots (e.g., Ranunculales and Proteales) and basal angiosperm Magnoliids (e.g., Magnoliales, Laurales, and Piperales) (Supplementary Fig. 1a)2,3,4. BIA biosynthesis begins with the condensation of dopamine and 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (4-HPAA), catalyzed by norcoclaurine synthase, forming norcoclaurine (NCC)5. This intermediate serves as foundation for diverse BIA class, such as bisbenzylisoquinolines, aporphines, morphinans, protopines, berberines, phthalideisoquinolines (Supplementary Fig. 1b)3,6,7. Although BIA biosynthesis can be complex, they largely stem from the mainstream pathway of 1-benzylisoquinolines (1-BIAs), which do not have a direct C-C coupling between the phenolic group and the isoquinoline ring. Biosynthesis of 1-BIAs mainly involves methylation and hydroxylation of NCC. Briefly, NCC is 6-O-methylated and N-methylated by 6OMT and CNMT enzymes, respectively, forming (S)-N-methylcoclaurine (NMC). The NMC is further catalyzed by CYP80B and 4’OMT enzymes, yielding (S)-reticuline (RTC), a central branch-point intermediate for synthesizing diverse BIA backbones through C-C coupling and other modifications (Supplementary Fig. 1c)8,9,10,11.

The diversification of BIAs in land plants is likely in a step-wise fashion, with the early-diverging Magnoliids species accumulating structurally simple BIAs (e.g., 1-BIAs and aporphines) and the latter-diverging eudicot Ranunculales species accumulating structurally more complex BIAs (e.g., sanguinarine, berberine and morphinan) (Supplementary Fig. 1a)2,3. While BIA pathways in Ranunculales (e.g., Papaver somniferum,) and Proteales species (e.g., Nelumbo nucifera) were extensively studied12,13,14,15, their biosynthesis and evolution in Magnoliids remain poorly understood. Recent years have seen increasing studies on the early-diverging angiosperm group Magnoliids, revealing new insights into diversification of BIAs. For instance, a study of Liriodendron chinense (Magnoliales) led to the discovery of not only a functionally conserved 6OMT (LcOMT1), but also a novel NMT (LcNMT1) capable of catalyzing both mono- and di-methylation of (S)-coclaurine (COC)16. In Aristolochia contorta (Aristolochiaceae, Magnoliids), researchers identified 6OMTs (AcOMT1 and AcOMT2) and a promiscuous CYP80Q enzyme (AcCYP80Q8) that converts (S,R)-NMC into (S,R)-Glaziovine. This contrasts with the stereospecific CYP80Q (NnCYP80Q1) in Nelumbo nucifera (Proteales), which exclusively recognizes (R)-NMC as a substrate15,17,18. While these limited studies indicate conservation and diversification of BIAs between Magnoliids and other eudicot plant families, a systematic analysis of the complete mainstream pathway for 1-BIA biosynthesis in Magnoliids remains lacking. This knowledge gap thus hinders a comprehensive understanding of BIA evolution across flowering plants.

Here, we focused on Houttuynia cordata (Saururaceae)--a Magnoliids species known as Yu Xing Cao--a herbaceous plant widely used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (Fig. 1a)19. We characterized a cascade of key enzymes (6OMT, NMT, CYP80B, and 4’OMT) responsible for RTC biosynthesis in H. cordata, providing compelling evidence for conservation of 1-BIA biosynthesis between Magnoliids and other angiosperm families. We also identified a neofunctionalized NMT (HcNMT5) that specifically produces di-methylated COC and the first reported isoboldine synthase (HcCYP80G2) in plants. Intriguingly, evolutionary analysis reveals that the CYP80B, 4’OMT and 6OMT genes are frequently clustered across diverse Magnoliids and Ranunculales species. This gene clustering correlates with coordinated chemical modifications on the phenol rings of RTC, enabling selective C-C coupling reactions to generate specific scaffolds for diverse BIAs in flowering plants. The chemistry-associated gene clustering thus may complement other widely debated scenarios explaining metabolic gene clustering, such as intermediate toxicity, coordinated gene co-expression and natural selections20,21,22,23. This work not only identifies the conservation and diversification of BIA biosynthesis in angiosperms, but also shows that biochemical reaction interdependency may be an overlooked evolutionary driver of gene cluster formation.

a Images of H. cordata showing its leaves and rhizomes. b Detection of four major 1-BIAs (compared to standards) in plant tissues of H. cordata using UPLC-MS/MS. Extracted ion chromatograms are shown. c Enzyme assay of Hc6OMT1 or Hc6OMT2 with supply of norcoclaurine (NCC) in transient N. benthamiana system. Coclaurine (COC) was exclusively detected in samples expressing 6OMTs by UPLC-MS, compared to a chemical standard. d Enzyme assay of HcNMTs with supply of COC in transient N. benthamiana system. Aligned extracted ion chromatograms are shown for the standards and tobacco samples in UPLC-MS analysis. Mono- or di-methylated products are shown. In both (c, d), tobacco leaves expressing with a MNG fluorescence protein were used as negative control. e Partial sequence alignment for HcNMTs and characterized CNMTs. A (S)-reticuline (RTC) N-methyltransferase PsRNMT (Papaver somniferum; Ranunculales) with di-methylation functionality is included. The key amino acid residue is highlighted in a red box. f Proposed MGC biosynthetic pathways in H. cordata.

Results

Identification of genes for 1-BIA biosynthesis in H. cordata

In Magnoliids plants, the prevalent type of BIAs are structurally simple 1-BIAs and aporphines (Supplementary Fig. 1a)3. To gain insights into 1-BIA biosynthesis in H. cordata (Fig. 1a), we purchased four available 1-BIA standards-- NCC, COC, NMC and RTC (Supplementary Table 1) --and applied targeted metabolic analysis to two plant tissues: rhizomes and leaves (Fig. 1a). Ultra-performance liquid chromatograms coupled with mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) analysis showed that the four 1-BIAs were present in H. cordata, with predominant accumulation in rhizomes (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 2). To identify 1-BIA biosynthetic genes in H. cordata, we carried out homology searches in the recently published H. cordata genome24 for enzyme families involved in the RTC pathway (see Methods), including OMT, NMT and CYP80 families (Supplementary Tables 2–4). This analysis identified two 6OMT, two 4’OMT, five NMT and seven CYP80 genes (see “Methods”) (Supplementary Figs. 3–5; Supplementary Table 5). Examination of their gene expression pattern across six plant tissues revealed that ~80% of these genes share similar expression profiles (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Functional characterization of 6OMTs in H. cordata

According to previous studies25, 6OMT serves as the rate-limiting step in 1-BIA production and catalyzes the first modification of the fundamental BIA backbone, NCC. To verify the functions of the two candidate 6OMT genes (Hc6OMT1 and Hc6OMT2), we first cloned them from a cDNA library and tested their activities using a hyper-trans expression system in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves26,27. Agrobacterium strains carrying Hc6OMT1 or Hc6OMT2 were infiltrated into tobacco leaves for about three days to enable protein synthesis, followed by infiltration of NCC (not natively synthesized in tobacco). Metabolites extracted from leaf tissues after three days were analyzed by UPLC-MS. Compared to the control expressing a fluorescence protein (instead of 6OMT), both Hc6OMT1 and Hc6OMT2 samples produced a new compound with retention time and MS spectra matching authentic COC standard (Fig. 1c). Given that NCC and COC were detected in H. cordata tissues (Fig. 1b), these results confirm that Hc6OMT1 and Hc6OMT2 encode functional enzymes responsible for norcoclaurine 6-O-methylation in H. cordata.

Functional characterization of CNMT in H. cordata

The N-methylation of COC, catalyzed by COC N-methyltransferase (CNMT), was recently characterized in Magnoliids species L. chinense16. To investigate the functions of the five candidate HcCNMT genes, we tested them using the transient expression system in tobacco described earlier. When COC was supplied, samples expressing HcNMT2, HcNMT3, or HcNMT4 produced a compound identified as NMC based on its matching retention time and MS spectra with an authentic NMC standard (Fig. 1d). In contrast, no NMC-related molecules were identified in HcNMT1 or HcNMT5 samples, suggesting these paralogs may have lost NMC-producing activity. In L. chinense, the characterized CNMT (LcNMT1) exhibits dual functionality, producing both NMC (mono-methylated COC) and magnocurarine (MGC; di-methylated COC). This contrasts with Ranunculales CNMTs, which exclusively synthesize NMC10. Similarly, MGC was detected in tobacco samples overexpressing HcNMT2, HcNMT4, or HcNMT5, implying that Magnoliids CNMTs may have acquired broader/new catalytic roles. Strikingly, HcNMT5 exclusively produced MGC (Fig. 1d). A single E204G mutation in LcNMT1 has been shown to shift its activity to MGC-only production16. The glycine (G) residue also presents in PsRNMT (Papaver somniferum; Ranunculales) which has di-methylation functionality on (S)-RTC (Supplementary Fig. 1c, e)28,29. Consistent with this, sequence alignment revealed that only glycine occupies the equivalent position in HcNMT5 (Fig. 1e). Therefore, HcNMT5 functions as a natural NCC di-methyltransferase, specifically generating MGC in H. cordata (Supplementary Fig. 7). Our work thus reveals a complex biosynthetic network for MGC production in H. cordata, underpinned by gene duplication and neofunctionalization (Fig. 1f).

To further test the results of enzymatic activities of 6OMTs and NMTs obtained from transient assays in N. benthamiana, we evaluated their functionality using crude protein extracts from tobacco leaves incubated with the substrates and the cofactor S-adenosyl methionine (SAM). These experiments confirmed their roles as methyltransferases (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Functional characterization of (S)-reticuline biosynthesis in H. cordata

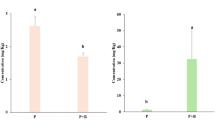

Previous studies have shown that CYP80B and 4’OMT are involved in (S)-RTC biosynthesis8,9. CYP80B catalyzes the 3’-hydroxylation of NMC, followed by 4’OMT-mediated 4’-O-methylation to produce RTC (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Our homology search identified one CYP80B (HcCYP80B) and two 4’OMTs (Hc4’OMT1 and Hc4’OMT2) (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 5). Interestingly, HcCYP80B and Hc4’OMT1 are tightly linked on the chromosome and exhibit highly similar expression patterns across major plant tissues (Fig. 2a). While multiple CYP80B gene copies exist in the flanking region of Hc4’OMT2, these genes are likely undergoing pseudogenization (Fig. 2a). The three genes were successfully cloned and functionally tested in tobacco leaves. When NMC was supplied as a substrate, tobacco expressing HcCYP80B produced a compound (1) with m/z = 316, 16 units higher than NMC (m/z = 300). Co-expression of HcCYP80B with Hc4’OMT1 led to a sharp decline in 1 and the production of RTC, confirming 1 as 3’-hydroxy-NMC. Hc4’OMT2 displayed comparable catalytic capability, with seemingly less efficiency (Fig. 2b). Moreover, Hc4’OMT2 showed negligible expression across all tissue transcriptomes (Fig. 2a). Together, these results indicate that the HcCYP80B-Hc4’OMT1 mini-gene cluster drives NMC-to-RTC conversion in H. cordata (Fig. 2c).

a Expression pattern for the genes in CYP80B-4’OMT cluster (Chromosome 11a) and its duplicated region (Chromosome 01a). Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped fragments (FPKM) values were derived from the published dataset24 and used to create the heatmap. The cluster is drawn based on annotation file. Three CYP80B truncated sequences identified in Chr. 01a are shown with dashed arrows. b Enzyme assay of HcCYP80B and Hc4’OMTs with supply of N-methylcoclaurine (NMC) in transient N. benthamiana system. Aligned extracted ion chromatograms (m/z = 316; m/z = 330) are shown for (S)-reticuline (RTC) standard and tobacco samples in UPLC-MS analysis. c Schematic view of HcCYP80B-Hc4’OMT1 gene cluster determined (S)-reticuline (RTC) biosynthesis in H. cordata.

In summary, mainstream 1-BIA biosynthesis in flowering plants--including Magnoliids and Ranunculales--likely relies on conserved 6OMT, CNMT, CYP80B, and 4’OMT (sub)-families.

Identification of a novel aporphine synthase in H. cordata

In addition to 1-BIAs, H. cordata produces aporphine alkaloids likely derived from the 1-BIA30. For instance, aristolactam--a nephrotoxic compound--is an aporphine alkaloid frequently detected in H. cordata31,32. Studies indicate that CYP80Q and CYP80G, members of the CYP80 family, play key roles in aporphine alkaloids backbone formation via C–C coupling reactions15,33. To identify candidate aporphine alkaloid biosynthetic genes in H. cordata, we successfully cloned HcCYP80Q1 and two CYP80G genes (HcCYP80G1 and HcCYP80G2) and tested their activity in the tobacco transient expression system, co-infiltrated with putative substrates (NMC or RTC). We next screened for potential products exhibiting a 2-unit mass reduction relative to substrates, consistent with C–C coupling. While no targeted products were detected for CYP80Q (Supplementary Fig. 9), CYP80Gs assays with RTC yielded distinct products. UPLC-MS/MS analysis revealed that the HcCYP80G1 expression generated a new compound (2) compared to the control, while HcCYP80G2 produced an additional compound (3) (Fig. 3a). In Coptis japonica (Ranunculales), CYP80G converts RTC to (S)-corytuberine (CTB) via a C2’-C8 phenol coupling reaction33. However, 2 and 3 did not co-elute with the CTB standard in the UPLC-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 3a). Several mechanistic studies indicate CYP80G-mediated phenol coupling begins with 3’-OH hydrogen abstractions, followed by radical migration to reactive carbons (Supplementary Fig. 10)13,33,34. Chemically, ortho- and para-carbons in hydroxyphenyl group are more reactive than meta-carbons due to electronic and steric effects. Beyond C2’–C8 coupling (as in CTB), alternative products like isoboldine (IBD)—a C6’–C8-coupled aporphine alkaloid—are plausible. Recent work has also proposed that IBD originates from RTC35. Using an IBD standard, we confirmed that 3 matched IBD in retention time and fragmentation patterns. Detectable IBD levels in H. cordata leaves and rhizomes further support HcCYP80G2 as an isoboldine synthase (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 11). Additionally, we directly determined the in vitro enzyme activity using tobacco leaves crude protein extracts incubated with the substrate RTC (see “Method”). Again, only HcCYP80G2 was found to produce IBD, but not HcCYP80G1 or the negative control (Supplementary Fig. 12). To our best knowledge, this is the first reported plant enzyme responsible for IBD biosynthesis. Compound 2, however, could not be purified or matched to known standards.

a Detection of HcCYP80G1 and HcCYP80G2 functions on (S)-reticuline (RTC) in transient tobacco system by UPLC-MS/MS. STD Standard, CTB (S)-corytuberine, IBD isoboldine. RTC was supplied as substrate. Ions with a reduction of 2-m/z relative to RTC were searched. 2 and 3 were identified as products. Notably, the CTB co-eluted peaks in plant tissue samples showed distinct parent ions in UPLC-MS/MS. b The molecular docking between alphafold3 predicted HcCYP80G2 and the ligand RTC. c The proposed catalytic mechanism of HcCYP80G2. Based on the result in (b), it is likely that the first hydrogen abstraction occurs at the 3’-OH group, followed by the second hydrogen abstraction at the 7-OH group. The C8-C6’ linkage is then proceeded by two one-electron transfers with subsequent radical coupling.

The catalytic mechanism for CTB synthase (CjCYP80G2) was previously proposed33(Supplementary Fig. 10). We next generated a 3D structure of IBD synthase (HcCYP80G2) using AlphaFold3 and docked it with the RTC substrate (Fig. 3b). In the simulation, the 3’-OH oxygen atom of RTC is positioned 4.5 Å from the Fe(II) center in the heme, while the distance for the 7-OH group is 6.2 Å (Fig. 3b). It has been proposed that a two-step of the Fe=O-mediated hydrogen abstraction (first in the 3’-OH, then in the 7-OH), followed by radical migrations to the C8 and C2’ carbons, enabling the production of CTB through C–C coupling in Coptis japonica33. Given the high similarity of docking simulation results between the CTB and IBD synthase, it is likely that the resulting radical (consequence of hydrogen abstraction in 3’-OH) migrates to the para-carbon (C6’), giving rise to distinct C–C coupling reaction and the subsequent formation of IBD (Fig. 3c).

Large-scale identification of “OMT-CYP” gene clustering across a wide range of BIA-producing plant species

Despite the wide BIA distribution in Magnoliids, biosynthesis pathways in this clade remain poorly characterized. To advance our understanding of BIA evolution, we investigated the conservation and diversification of the CYP80B-4’OMT mini-gene cluster across Magnoliids. We performed synteny analysis on genomes of seven BIA-producing species spanning five plant families (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 6). The CYP80B-4’OMT cluster was present in all examined genomes and localized to conserved syntenic genomic blocks, except in Annona cherimola (Annonaceae) (Fig. 4). Intriguingly, 6OMT genes were identified in the CYP80B-4’OMT flanking region in four species from three plant families (Annonaceae, Magnoliaceae and Aristolochiaceae) (Fig. 4). Notably, the 6OMT genes within syntenic blocks of L. chinense (Magnoliaceae) and Aristolochia contorta (Aristolochiaceae)--functionally characterized in recent studies16,17--share synteny with Hc6OMT in H. cordata. Given the phylogenetic diversity of our sampled genomes, we propose that the 6OMT-CYP80B-4’OMT gene cluster likely originated in early flowering plant ancestors prior to the divergence of Magnoliales and Piperales. In contrast, the CYP80B-4’OMT cluster occupies distinct genomic blocks relative to 6OMT gene in H. cordata, Saururus chinensis and Piper nigrum (Fig. 4), suggesting additional translocation of this module in Saururaceae and Piperaceae during evolution.

BIA related gene clusters were first characterized in Papaver somniferum (Ranunculales) for morphine and noscapine production36. However, these gene clusters appear unique to the P. somniferum, and earlier studies did not include 6OMT, CYP80B, and 4’OMT genes. Remarkably, reanalysis of the P. somniferum genome revealed gene clusters containing PsCYP80B paired with either Ps6OMT or Ps4’OMT (Supplementary Fig. 13). Similar CYP80B-6OMT or CYP80B-4’OMT gene clusters were recently identified in three additional Ranunculales species (Stephania japonica, Stephania yunnanensis, and Stephania cepharantha)37. Expanding this analysis to diverse BIA-producing Ranunculales species confirmed the widespread occurrence of such clusters, though the 6OMT-CYP80B type dominated in this order (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Collectively, our large-scale analysis of BIA producing plants across basal angiosperms (Magnoliids) and early-diverging eudicots (Ranunculales) reveal dynamic gene clustering of 6OMT, CYP80B, and 4’OMT genes, which encode critical steps for BIA backbone biosynthesis. This conserved genomic architecture thus provide a potential marker for identifying BIA pathways in other plant lineages.

Discussion

Here, we have characterized a cascade of key enzymes critical for the core BIA backbone formation in H. cordata. While these catalyzing enzyme (sub)families are likely conserved between Ranunculales and Magnoliids (two major BIA-producing clades in flowering plants), functional diversification is evident through gene duplications in H. cordata. This is reflected by (1) variable catalytic activity between paralogs; (2) sub- or neo-functionalized gene cop(ies) such as HcNMT5 and HcCYP80G2. As a polyploid species, H. cordata’s whole-genome duplication (WGD) events may have driven this diversification, though mechanistic links require further investigation.

Our work also reveals widespread dynamic 6OMT-CYP80B-4’OMT gene clustering across species in Ranunculales and Magnoliids. Unlike most biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs)21,38, which are typically lineage-restricted, these clusters occur dynamically across phylogenetically distant flowering plants (Supplementary Fig. 13). While metabolic gene clustering has emerged as a key framework for studying genome evolution and metabolic diversification, its evolutionary drivers remain poorly understood and debated21,23. A prevailing hypothesis posits that clustering facilitates coordinated spatiotemporal gene regulation via genetic or epigenetic modulations39,40,41. Others argue that natural selection—either purifying or positive—drives cluster assembly21,42. For instance, purifying selection may maintain the thalianol cluster in Arabidopsis thaliana, as mutations in these genes produce toxic intermediates38,43. Contrarily, positive selection likely preserves BGCs encoding defensive compounds, favoring co-inheritance of functionally linked genes22,44,45. While these models could theoretically explain 6OMT-CYP80B-4’OMT clustering, their prevalence across angiosperms suggests additional mechanisms may exist.

The three genes encode enzymes that modify phenyl groups to generate RTC—the central intermediate skeleton for other BIAs via C–C coupling reactions—resulting in a conserved structural feature: one methylated -OH and one free -OH group on its phenyl rings (Fig. 5). To investigate the functional necessity of these modifications, we revisited three downstream enzymes catalyzing RTC’s intramolecular C–C coupling: the sinoacutine synthase MdCYP80G10 in Menispermum dauricum13, the salutaridine synthase PsCYP719B1 in P. somniferum34, and the (S)-corytuberine synthase CjCYP80G2 in Coptis japonica33 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Despite differing evolutionary origins and coupling products, all enzymes require a free -OH group for catalysis (e.g., hydrogen abstraction) (Supplementary Fig. 10). Complete methylation of both -OH groups would block coupling, while unmethylated intermediates with multiple free -OH groups impair catalytic activity. Consistent with this, these enzymes exhibit strict substrate selectivity, accepting only intermediates with one free -OH group11,33. As noted by Jonathan E. Poulton in The Biochemistry of Plants (1981), “methylation … reduces the chemical reactivity of the phenolic groups…. [and] may play a crucial role in directing intermediates toward specific biosynthetic pathways (of BIAs).” In our newly proposed model, the CYP80B generates a hydroxyl group required for subsequent C–C coupling; and the 6OMT or 4’OMT-mediated methylation acts as ‘protecting groups’6, ensuring regio-selectivity by preventing aberrant reactions. Therefore, the interplay between free -OH availability and methylation-directed selectivity might provide a mechanistic rationale for the evolutionary retention of 6OMT-CYP80B-4’OMT dynamic gene clustering in diverse plant families (Fig. 5). The clustering of genes associated with interlinked biochemical reactions thus inspires new perspectives on the evolutionary forces driving the formation of metabolic gene clusters in plants.

The coupled chemical reactions (phenyl hydroxylation and O-methylation) are essential for the intramolecular selective C–C coupling of RTC, which generates a series of specialized BIAs (three reported examples plus the HcCYP80G2 with distinct C–C couplings are illustrated; see details in Supplementary Fig. 10). We speculate that the interdependence between the two functional groups underpins the dynamic gene clustering of the 6OMT, CYP80B, and 4’OMT genes across a wide range of plant lineages.

Methods

Plant materials and chemical standards

The H. cordata and N. benthamiana plant samples were grown in a growth chamber (16 h of light/8 h of dark, 22 °C) at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. All chemical standards used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Bioinformatics analysis

The genome sources used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table 6. The information on reference protein was listed in Supplementary Tables 2–4. For identification of OMTs, NMTs, and CYP80s, BLASTP with a cut-off of E value (<1e−10) and sequence identity (>40%) was applied. The output was further filtered by sequence length (300–700 residues for CYPs and 200–500 residues for OMTs and NMTs)46,47,48. Multiple sequence alignment was generated with MUSCLE49. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed using FastTree50. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using iTOL (https://itol.embl.dei). Microsynteny analysis was performed using the MCscan package with default parameters (https://github.com/tanghaibao/jcvi/wiki/MCscan-(Python-version)). We obtained the gene expression matrix using the published Houttuynia cordata transcriptome data24. The raw paired-end reads were processed for quality control and trimming using Trimmomatic 0.39, adhering to the default settings51. The cleaned reads were mapped to the reference genome using the HISAT2 software in directional mode52. Subsequently, for each sample, the mapped reads were used to assemble transcripts with StringTie through a reference-guided assembly approach to output the FPKM values53.

Docking simulation analysis

The structure of HcCYP80G2 with its heme ligand was predicted using AlphaFold354. The RTC ligand structure was drawn with ChemDraw (v22.0.0 64-bit). The docking results were simulated using NRGSuite-Qt55, a PyMOL (v3.1.3; PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; Schrödinger) plugin based on FlexAID56, which relies on a genetic algorithm to predict binding sites and generate docking results. The plugin identified the binding site, and the top-ranked one was selected for FlexAID docking. The docking parameters were set to 2000 for both the initial population (chromosomes) and the number of generations. The result with the highest docking score was chosen as the result. PyMOL was also used to visualize the docking results.

Gene cloning and synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using Total RNA Extractor (Trizol) (Sangon BioTech, Shanghai, China), and the cDNA was synthesized using the HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The candidate genes were amplified by PCR using cDNA from H. cordata as the template and the PCR products were inserted into pEAQ-Xhol vector (digested with Xhol) using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 7.

Transient expression and enzyme assay in N. benthamiana

Candidate genes were cloned into the pEAQ-Xhol vector and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (LBA44404). A positive colony was selected and resuspended in 10 mL of LB medium, incubated at 28 °C with agitation at 220 rpm until the value of OD600 nm reached 1, and then centrifuged at 4000 g for 10 min. The pellets were then resuspended in 5 mL MMA buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, and 150 μM acetosyringone in Milli-Q water), and incubated at 28 °C in the dark for 1 h. Agrobacterium suspension (the final OD600 nm = 0.2 for each strain) was infiltrated into the abaxial side of 6 to 8-week-old N. benthamiana leaves (on a 14 h light-cycle) using a 5 mL syringe until the entire leaf was infiltrated. The injected N. benthamiana plants were then kept in the dark for 1 day, followed by 2 days of light exposure (14 h light-cycle). Next, 0.1% DMSO with or without 25 μM substrate was infiltrated into the abaxial side of previously Agrobacterium-infiltrated leaves. 3 days after feeding, leaves were harvested, lyophilized, ground into powder, and stored at −20 °C for later analysis. Each treatment consisted of 3 or 4 leaves, and the biological replicates consisted of 3 different plants.

In vitro enzyme activity

For in-vitro enzyme activity analysis, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 carrying the target genes were used to infiltrate 4-week-old in N. benthamiana leaves. After 3 days, leaf samples were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, followed by extraction of crude protein using 400 µL of Plant Lysis Buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton-X100), and the homogenate was centrifuged at 13,800 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing the crude protein extract was collected, and protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. For enzyme activity of CYPs, 100 µg of crude protein was incubated in a 100 µL reaction buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM NADPH, and 0.1 mM substrate (RTC) at 28 °C for 6 h. For the NMTs/OMTs, 100 µg of crude protein was incubated in a 100 µL reaction buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM SAM, and 0.1 mM substrate (COC/NCC) at 28 °C for 24 h. Reactions were terminated by adding 100 µL of methanol, followed by centrifugation at 13,800 g for 10 min to remove insoluble debris. Finally, 1 µL of the supernatant was injected into an UPLC-MS/MS system for product detection.

For enzyme activity analysis, 100 µg of crude protein was incubated in a 100 µL reaction buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM NADPH, and 0.1 mM substrate (RTC) at 28 °C for 6 h. Reactions were terminated by adding 100 µL of methanol, followed by centrifugation at 13,800 g for 10 min to remove insoluble debris. Finally, 1 µL of the supernatant was injected into an UPLC-MS/MS system for product detection.

BIA extraction from plants

Lyophilized tissue powder (100 mg for H. cordata; 50 mg for tobacco leaves) was weighed into a 2 mL centrifuge tube and 1 mL methanol was added. The mixture was sonicated for 30 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min. After being transferred into a new 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, the extraction was spun-dried in a Genevac (EZ-2 4.0) and then dissolved in 200 μL methanol by 10 min of ultrasonication. After centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min, 100 μL extraction solution was transferred into vials for UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

UPLC–MS analysis

The UPLC-MS analysis was performed on a UHPLC-MS system (Thermo Scientific Vanquish UHPLC) equipped with a C18 column (1.8 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B), and the linear gradient elution program was as follows: 0–2 min, 2% B; 2–10 min, 2–10% B; 10–13 min, 10–50% B; 13–16 min, 50–95% B; 16–18 min, 95% B; 18–18.1 min, 95–2% B; 18.1–20 min, 2% B. The flow rate was 0.25 mL/min and the column temperature was 25 °C. The electrospray ionization (ESI) source was used for detection in a positive-ion mode with a vaporizer temperature of 350 °C and a m/z range of 200–800.

UPLC–MS/MS analysis

The UPLC-MS/MS analysis was performed on a Thermo Fisher Vanquish UPLC system coupled to a Q-Exactive Plus Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). A UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm i.d. × 100 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters) with a VanGuard BEH C18 precolumn (2.1 mm i.d. × 5 mm, 1.7 µm, Waters) was used for separation. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The linear gradient elution program was as follows: 0–2 min, 5% B; 2–12 min, 5–15% B; 12–18 min, 15–50% B; 18–19 min, 50–100% B; 19–20 min, 100% B; 20–21 min, 100–5% B; 21–22 min, 5% B. The flow rate was 0.30 mL/min and the column temperature was 25 °C. The ESI source was used for detection in a positive-ion mode with a mass range of m/z 150–500.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. All functional experiments in transient N. benthamiana leaves were performed in triplicate unless otherwise stated.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Dembitsky, V. M., Gloriozova, T. A. & Poroikov, V. V. Naturally occurring plant isoquinoline N-oxide alkaloids: their pharmacological and SAR activities. Phytomedicine 22, 183–202 (2015).

Liscombe, D. K., MacLeod, B. P., Loukanina, N., Nandi, O. I. & Facchini, P. J. Evidence for the monophyletic evolution of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in angiosperms. Phytochemistry 66, 2501–2520 (2005).

Tian, Y. et al. Structural diversity, evolutionary origin, and metabolic engineering of plant specialized benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1787–1810 https://doi.org/10.1039/d4np00029c (2024).

Martin, F. et al. Alkaloids from the Chinese vine Gnetum montanum. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 2425–2430 (2011).

Samanani, N., Liscombe, D. K. & Facchini, P. J. Molecular cloning and characterization of norcoclaurine synthase, an enzyme catalyzing the first committed step in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant J. 40, 302–313 (2004).

Dastmalchi, M., Park, M. R., Morris, J. S. & Facchini, P. Family portraits: the enzymes behind benzylisoquinoline alkaloid diversity. Phytochemistry Rev. 17, 249–277 (2018).

Hagel, J. M. & Facchini, P. J. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid metabolism: a century of discovery and a brave new world. Plant Cell Physiol. 54, 647–672 (2013).

Morishige, T., Tsujita, T., Yamada, Y. & Sato, F. Molecular characterization of the S-adenosyl-L-methionine:3’-hydroxy-N-methylcoclaurine 4’-O-methyltransferase involved in isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesisin Coptis japonica. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23398–23405 (2000).

Pauli, H. H. & Kutchan, T. M. Molecular cloning and functional heterologous expression of two alleles encoding (S)-N-methylcoclaurine 3’-hydroxylase (CYP80B1), a new methyl jasmonate-inducible cytochrome P-450-dependent mono-oxygenase of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant J. 13, 793–801 (1998).

Choi, K. B., Morishige, T., Shitan, N., Yazaki, K. & Sato, F. Molecular cloning and characterization of coclaurine N-methyltransferase from cultured cells of Coptis japonica. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 830–835 (2002).

Kutchan, T. M. & Dittrich, H. Characterization and mechanism of the berberine bridge enzyme, a covalently flavinylated oxidase of benzophenanthridine alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 24475–24481 (1995).

Singh, A., Menéndez-Perdomo, I. M. & Facchini, P. J. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy: an update. Phytochem. Rev. 18, 1457–1482 (2019).

An, Z. et al. Lineage-specific CYP80 expansion and benzylisoquinoline alkaloid diversity in early-diverging eudicots. Adv. Sci. 11, 1–14 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Analysis of the Coptis chinensis genome reveals the diversification of protoberberine-type alkaloids. Nat. Commun. 12, 3276 (2021).

Menéndez-Perdomo, I. M. & Facchini, P. J. Elucidation of the (R)-enantiospecific benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthetic pathways in sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera). Sci. Rep. 13, 1–18 (2023).

Cheng, W. et al. Characterization of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid methyltransferases in Liriodendron chinense provides insights into the phylogenic basis of angiosperm alkaloid diversity. Plant J. 112, 535–548 (2022).

Cui, X. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of Aristolochia contorta provides insights into the biosynthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and aristolochic acids. Hortic Res. 9, uhac005 (2022).

Meng, F. et al. Characterization of two CYP80 enzymes provides insights into aporphine alkaloid skeleton formation in Aristolochia contorta. Plant J. 118, 1439–1454 (2024).

Wei, P. et al. Houttuynia Cordata Thunb.: a comprehensive review of traditional applications, phytochemistry, pharmacology and safety. Phytomedicine 123, 155195 (2024).

Nützmann, H. W., Scazzocchio, C. & Osbourn, A. Metabolic gene clusters in eukaryotes. Annu Rev. Genet. 52, 159–183 (2018).

Polturak, G., Liu, Z. & Osbourn, A. New and emerging concepts in the evolution and function of plant biosynthetic gene clusters. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 33, 100568 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Formation and diversification of a paradigm biosynthetic gene cluster in plants. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2020).

Zhang, J., Zhang, J. & Peters, R. J. Why are momilactones always associated with biosynthetic gene clusters in plants? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 13867–13869 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. The Houttuynia cordata genome provides insights into the regulatory mechanism of flavonoid biosynthesis in Yuxingcao. Plant Commun. 5, 101075 (2024).

Robin, A. Y., Giustini, C., Graindorge, M., Matringe, M. & Dumas, R. Crystal structure of norcoclaurine-6-O-methyltransferase, a key rate-limiting step in the synthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Plant J. 87, 641–653 (2016).

Reed, J. et al. A translational synthetic biology platform for rapid access to gram-scale quantities of novel drug-like molecules. Metab. Eng. 42, 185–193 (2017).

Stephenson, M. J., Reed, J., Brouwer, B. & Osbourn, A. Transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves for triterpene production at a preparative scale. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 1–11 (2018).

Morris, J. S., Yu, L. & Facchini, P. J. A single residue determines substrate preference in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid N-methyltransferases. Phytochemistry 170, 112193 (2020).

Morris, J. S. & Facchini, P. J. Isolation and characterization of reticuline N-methyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of the aporphine alkaloid magnoflorine in opium poppy. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 23416–23427 (2016).

Ma, Q. et al. Bioactive alkaloids from the aerial parts of Houttuynia cordata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 195, 166–172 (2017).

Michl, J., Ingrouille, M. J., Simmonds, M. S. J. & Heinrich, M. Naturally occurring aristolochic acid analogues and their toxicities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 676–693 (2014).

Xu, Z. et al. In vitro nephrotoxicity and quantitative UPLC-MS analysis of three aristololactams in Houttuynia cordata. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 227, 115289 (2023).

Ikezawa, N., Iwasa, K. & Sato, F. Molecular cloning and characterization of CYP80G2, a cytochrome P450 that catalyzes an intramolecular C-C phenol coupling of (S)-reticuline in magnoflorine biosynthesis, from cultured Coptis japonica cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8810–8821 (2008).

Gesell, A. et al. CYP719B1 is salutaridine synthase, the C-C phenol-coupling enzyme of morphine biosynthesis in opium poppy. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24432–24442 (2009).

Li, Q. et al. Identification of the cytochrome P450s responsible for the biosynthesis of two types of aporphine alkaloids and their de novo biosynthesis in yeast. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 66, 1703–1717 (2024).

Winzer, T. et al. A Papaver somniferum 10-gene cluster for synthesis of the anticancer alkaloid noscapine. Science 336, 1704–1708 (2012).

Leng, L. et al. Cepharanthine analogs mining and genomes of Stephania accelerate anti-coronavirus drug discovery. Nat Commun 15, 1537 (2024).

Field, B. & Osbourn, A. E. Clusters in different plants. Science 194, 543–547 (2008).

Zhan, C. et al. Selection of a subspecies-specific diterpene gene cluster implicated in rice disease resistance. Nat. Plants 6, 1447–1454 (2020).

Shang, Y. et al. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber. Science 346, 1084–1088 (2014).

Nützmann, H. W. & Osbourn, A. Regulation of metabolic gene clusters in Arabidopsis thaliana. N. Phytol. 205, 503–510 (2015).

Takos, A. M. & Rook, F. Why biosynthetic genes for chemical defense compounds cluster. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 383–388 (2012).

Huang, A. C. et al. A specialized metabolic network selectively modulates Arabidopsis root microbiota. Science 364, eaau6389 (2019).

Nützmann, H. W., Huang, A. & Osbourn, A. Plant metabolic clusters–from genetics to genomics. N. Phytol. 211, 771–789 (2016).

Polturak, G. & Osbourni, A. The emerging role of biosynthetic gene clusters in plant defense and plant interactions. PLoS Pathog. 17, 1–11 (2021).

Nelson, D. & Werck-Reichhart, D. A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J. 66, 194–211 (2011).

Hansen, C. C., Nelson, D. R., Møller, B. L. & Werck-Reichhart, D. Plant cytochrome P450 plasticity and evolution. Mol. Plant 14, 1244–1265 (2021).

Facchini, P. J. & Morris, J. S. Molecular origins of functional diversity in benzylisoquinoline alkaloid methyltransferases. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1–22 (2019).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. Fasttree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Bolger, A. M. et al. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, 1–18 (2022).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Shumate, A., Wong, B., Pertea, G. & Pertea, M. Improved transcriptome assembly using a hybrid of long and short reads with StringTie. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, 1–18 (2022).

Galdino, G. T. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Galdino, G. T. & Desc, T. NRGSuite-Qt: A PyMOL plugin for high-throughput virtual screening, molecular docking, normal-mode analysis, the study of molecular interactions and the detection of binding-site similarities. Bioinform. Adv. 5, 1–13 (2025).

Gaudreault, F. & Najmanovich, R. J. FlexAID: revisiting docking on non-native-complex structures. J. Chem. Inf. Model 55, 1323–1336 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Rui Xia (South China Agricultural University) for critical reading and discussions. The Z.L. laboratory is funded by National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2602000). S.W. is funded by the Project for Innovative Leading Talent in Jiangxi “Ganpo excellent talent plan” (gpyc20240024). And both labs are supported by the Key Project at Central Government Level: The Ability Establishment of Sustainable Use for Valuable Chinese Medicine Resources (2060302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. conceived the idea and supervised the project. C.S., and X.Z. performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the figures. C.Z. conducted molecular docking analysis. S.W., J.W., J.Z. and N.A. contributed to data analysis and writing. W.J. contributed to metabolites analysis. B.C. contributed to plant collection and growth. A.R. & K.W. contributed to CYP80G in vitro assays. Z.L. & C.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shan, C., Zhou, X., Zhu, J. et al. Gene duplication and clustering underlie the conservation and diversification of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. Nat Commun 16, 7669 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63175-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63175-x