Abstract

Selective hydrogenation of CO2 into methanol offers an ideal route for the utilization of greenhouse gas, but it remains a great challenge to be carried out under mild conditions due to the intrinsic chemical stability of CO2. Here, we report sulfur-bridged cooperative molybdenum binuclear sites anchored on covalent triazine frameworks (denoted as Mo-S-Mo/CTF), as highly efficient active sites for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol at room temperature. Under near-ambient conditions (30 °C, 0.9 MPa), Mo-S-Mo/CTF produces methanol with 96% selectivity and a methanol synthesis rate of 21.88 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1. In-situ spectroscopic characterizations combined with theoretical calculations reveal that Mo-S-Mo/CTF favors CO2 hydrogenation into methanol via the formate pathway at room temperature instead of the CO pathway at 150 °C. The cooperation of CO2 activation on one molybdenum site and H2 splitting on the other plays a key role in high catalytic activity. Our work provides a new direction for methanol synthesis at room temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Selective conversion of CO2 into high-value-added chemicals represents a promising approach for the mitigation of excessive CO2 emission1,2. Among the various reduction products of CO2, methanol attracts great attention, as it can serve as a basic industrial raw material that widely be used to synthesize a series of important industrial chemicals3,4. However, the intrinsic chemical stability of CO2 and consecutive multi-step hydrogenation process render it a great challenge for the reaction of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol to be operated with high activity and selectivity under mild conditions. For instance, conventional metal oxide catalysts such as CuO, In2O3, and ZnO have been widely used for CO2 hydrogenation5,6,7, which is generally operated at temperature and pressure ranges of over 280 °C, and 5–10 MPa, respectively. The introduction of precious metals with excellent hydrogen dissociation abilities, such as Pd, can further moderate the reaction conditions, but the selectivity of methanol will be significantly reduced8. Therefore, the development of efficient catalysts capable of highly selective conversion CO2 into methanol under mild conditions is a great challenge, but also of paramount significance9,10.

In order to rational design of highly efficient catalysts, the reaction mechanism has been investigated. Generally, the mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation to methanol has been widely debated in the literature, focusing on two reaction pathways: formate pathway11,12,13 and the CO-involved pathway14,15. Although great efforts have been made to design efficient catalysts for this reaction in recent years16,17,18, only a few studies in the literature have reported achieving room temperature synthesis of methanol via CO2 hydrogenation19,20,21. For example, Deng et al.21 reported that the in-plane sulfur vacancies (Sv) in FL-MoS2 serve as the primary active sites for this reaction under mild conditions. Hosono et al.19 reported an air-stable hcp-PdMo intermetallic catalyst for room-temperature CO2 hydrogenation. Both FL-MoS2 and hcp-PdMo in the above works catalyzed methanol synthesis through the CO pathway. Limited by insufficient activation of active sites in nanoparticles, the methanol synthesis rate is extremely low (<0.3 mg g−1 h−1) at room temperature. Different from the production of *CO or *COOH in the CO-involved pathway, formate is more likely to be produced, and it’s reported to be synthesized over dual sites catalysts by the hydrogenation of CO2 even under ambient conditions22,23. Therefore, we believe that it is possible to efficiently synthesize methanol at room temperature by converting CO2 hydrogenation path into formate mechanism at low temperatures.

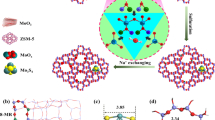

In this work, inspired by the high catalytic activity of MoS2, we employed a top-down strategy to disperse bulk layered-MoS2 into sulfur-bridged cooperative Mo binuclear sites anchored on covalent triazine frameworks (CTF). This strategy yielded a highly efficient catalyst, denoted as Mo-S-Mo/CTF, for the room-temperature CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via the formate mechanism. Specifically, under near ambient conditions (30 °C and 0.9 MPa), Mo-S-Mo/CTF achieves a 96% methanol selectivity and a methanol synthesis rate of 21.88 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1. Moreover, Mo-S-Mo/CTF exhibits promising stability for over 120 h in a stability test, without any obvious decay in its activity and selectivity for methanol. Combined with a series of characterizations, including Aberration correction high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM), X-ray photoelectron (XPS), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and atomistic simulations, the fine structure of Mo-S-Mo/CTF was confirmed to be cooperative molybdenum binuclear centers anchoring on CTFs via two Mo-N bonds and single Mo-S. Further in-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) analysis implies that CO2 hydrogenation follows the formate pathway to form methanol at room temperatures and the CO pathway to form CO intermediates at elevated temperatures (>150 °C), respectively. This work achieves CO2 hydrogenation to methanol under ambient temperature and sheds interesting light on the development of catalysts based on the in-depth reaction mechanism.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of catalysts

We synthesized the Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalyst using a top-down approach (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Method). First, CTF was synthesized using the traditional ion-thermal method by trimerization of 2,6-pyridinedicarbonitrile (2,6-DCP) in molten ZnCl2. Subsequently, the synthesized CTF was soaked in (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O and CH4N2S aqueous solution and kept at 200 °C in the hydrothermal reactor for 22 h. Followed by the reduction in an H2 atmosphere at 300 °C for 150 min, Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalyst was thus obtained. Bare MoS2 and MoS2/CTF with higher Mo loadings were also prepared as the references. FTIR characterization confirmed the successful synthesis of CTF. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, 2,6-DCP shows a distinct cyano group absorption peak at 2245 cm−1 which disappears completely after the ionthermal process, while the stretching vibrations at 1560 cm−1 and 1082 cm−1 corresponding to the stretching vibration of C-N bonds within the triazine ring structure become visible, indicating the trimerization is complete. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, the Mo-S-Mo/CTF chemical composition was calculated by in-situ XPS. The element Mo and N remain stable under the H2 reduction process and the element S decreases from 3.44 wt% to 2.98 wt%. Additionally, the Zn contents are 0.11 and 0.09 wt% in the Mo-S-Mo/CTF and MoS2/CTF, respectively. The physical adsorption was tested and listed in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2. Compared to MoS2/CTF and MoS2, the Mo-S-Mo/CTF had a larger specific surface area (1121.9 m2·g−1) and higher CO2 adsorption. capacity (39.12 cc·g−1). After uniformly loading MoS2, the specific surface area and CO2 adsorption capacity of the CTF significantly decreased. However, this trend did not continue in the H2 reduction process (Supplementary Fig. 4). It indicates that the introduction of CTF can significantly enhance the contact between CO2 and the active sites, thereby promoting the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Meanwhile, the pore structure of the Mo-S-Mo/CTF remains stable during the H2 reduction process. The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the as-synthesized Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalyst revealed an absence of the distinct diffraction peaks of MoS2 (PDF#75-1539), indicating a highly uniform dispersion of MoS2 on the CTF support (Supplementary Fig. 5). To determine the structure of Mo-S sites after H2 reduction treatment, the in-situ XRD of Mo-S-Mo/CTF was tested under 300 °C with H2 flow. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, there were no significant changes, and the Mo-S-Mo/CTF remained characterized by amorphous CTF, indicating that the uniformly dispersed MoS2 did not transform metal or metal oxide nanoparticles during the H2 reduction process. Complementary FTIR spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 7) corroborates this structural evolution: spectra of Mo-S-Mo/CTF before H2 reduction exhibit characteristic vibrations of layered MoS2 at 610, 891, and 1399 cm−1 alongside CTF-specific peaks24. After reduction, MoS2-related peaks vanish while CTF features persist.

The morphology of as-prepared Mo-S-Mo/CTF was further investigated by scanning electron microscope (SEM). As shown in Fig. 1a, MoS2 was uniformly dispersed on the external surface of CTF in the morphology of the thin layer nanosheet. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and AC-HAADF-STEM images (Fig. 1b, c) further revealed that these highly dispersed layered MoS2 were extremely thin, typically consisting of only a few layers, with an interlayer spacing of approximately 0.61 nm. The average thickness of the MoS2 nanosheets was determined to be 1.4 nm by using atomic force microscopy (AFM) characterization (Fig. 1d), corresponding to the thickness of 2-3 layers of MoS2, which was consistent with TEM characterization. For the MoS2/CTF and MoS2 reference catalysts, the dispersion of MoS2 species was more densely packed, and individual nanosheets exhibited much thicker thickness and a higher number of layers (Supplementary Figs. 8–10). After reduction treatment in H2 atmosphere, it is interesting to note that the layered MoS2 species have all disappeared for Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalyst (Fig. 1f). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) images (Fig. 1g) showed that Mo, C, N, and S were atomically dispersed in the Mo-S-Mo/CTF, which indicated that Mo and S species were anchored into the skeleton of CTF support from layered MoS2 during the reduction process. The atomic resolution fine structure of Mo-S-Mo/CTF was further investigated by using AC-HAADF-STEM. As shown in Fig. 1h, Mo-S-Mo/CTF exhibits a large number of adjacent, paired bright dots (labeled with a red square frame) distributed on a substrate of lower contrasts. These small bright dots can be attributed to atomically dispersed Mo considering their much higher Z contrast (M = 95.95 for Mo) than CTF (M = 12 or 14). Line-profile scanning for 6 pairs of such bright dots gives an average distance of 2.9 Å (±0.1 Å) (Fig. 1i). This is much shorter than the theoretical value (3.2 Å) for the two Mo atoms within MoS2, again confirming the reconstruction and condensation of the Mo-dimer moieties as a result of the removal of few-layer MoS2 in the synthesis. More evidence can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 11.

a SEM image of Mo-S-Mo/CTF before H2 reduction treatment. b HR-TEM images of Mo-S-Mo/CTF before H2 reduction treatment. c AC-HAADF-STEM images of Mo-S-Mo/CTF before H2 reduction treatment. d AFM image of Mo-S-Mo/CTF before H2 reduction treatment. e The AFM corresponding height profiles. f HAADF-STEM images of Mo-S-Mo/CTF. g Element mapping images of Mo-S-Mo/CTF. The scale bar is 50 nm. h AC-HAADF-STEM images of Mo-S-Mo/CTF. i Intensity profiles of dual-atom sites in a red frame.

The chemical nature of the Mo binuclear in Mo-S-Mo/CTF was probed by using quasi in-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in Fig. 2a, the peaks at 229.05 and 232.2 eV (red) are ascribed to 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 peaks of Mo4+, and the peaks in the blue line are ascribed to 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 peaks of Mo6+. After H2 reduction, the peaks ascribed to Mo6+ moved to the lower binding energy, possibly due to the loss of S coordination. The S 2p spectra were shown in Supplementary Fig. 12a, a peak at 168.3 eV ascribed to the SOx decreased after H2 reduction, and no excess stoichiometric S was observed. O 1s spectra contained peaks at 532.6 eV and 530.9 eV, attributed to the C=O and C-OH species, respectively. The surface oxidation could originated from the hydroxyls at CTF support, which could be observed at about 3400 cm−1 from FTIR of CTF (Supplementary Fig. 2). To clarify the origin of oxygen species, we conducted comparative XPS analysis of pristine CTF (Supplementary Fig. 13a), which exhibited identical O 1s profiles (C-OH: 533.1 eV; C=O: 531.8 eV)25. Furthermore, to investigate the structural and spectral of oxygen species at Mo-S-Mo/CTF, a reference MoO3/CTF catalyst was synthesized by using a hydrothermal method. The XRD pattern of MoO3/CTF (Supplementary Fig. 14a) shows no distinct diffraction peaks for crystalline MoO3, consistent with the XRD features of Mo-S-Mo/CTF, indicating its highly dispersed state on the amorphous CTF support. The HR-TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 14c) reveal the presence of MoO3 on CTF, with lattice spacings of 0.25 nm, corresponding to the (0 4 1) plane of orthorhombic MoO3. EDS elemental mapping (Supplementary Fig. 14d) confirms the uniform distribution of Mo, O, and N across the CTF support, verifying the successful synthesis of MoO3/CTF. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, displayed a distinct Mo-O peak at 530.2 eV, absent in both CTF and Mo-S-Mo/CTF. These results confirm that oxygen in Mo-S-Mo/CTF originates from the CTF support instead of the Mo-O species. The deconvoluted N 1s spectra of Mo-S-Mo/CTF demonstrate that the nitrogen species can be assigned to pyridinic N (398.2 eV), pyrrolic N (399.9 eV), and graphitic N (401.4 eV), consistent with N 1s spectra of pristine CTF (Supplementary Figs. 12c, 13b).

X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) measurements were performed at Mo K-edge to investigate the local structures of Mo atoms in catalysts. As shown in Fig. 2b, the K-edge of Mo-S-Mo/CTF lies between those of MoS2 and MoO3/CTF, indicating an average Mo oxidation state between +4 and +6, consistent with XPS results. The precisely local structure of Mo-S-Mo/CTF was obtained by fitting the EXAFS spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 3). The coordination number of the Mo-N path was estimated to be 2.1 with the bond distance of 1.70 Å, and the coordination number from the second sphere by the Mo-S path was assessed to 1.1, with the corresponding distance of 2.51 Å. The last sphere was determined to the Mo-Mo path with a coordination number of 1.1 and a corresponding distance of 2.91 Å, which is in agreement with the average Mo-Mo distance measured from AC-HADDF-STEM images (Fig. 1h). As shown in Fig. 2c, the EXAFS spectrum of Mo-S-Mo/CTF fundamentally differs from MoO3/CTF, which exhibits distinct Mo-O (1.1 Å) and Mo-Mo (1.6 Å and 3.2 Å). The Mo K-edge k2χ(k) oscillation curve for Mo-S-Mo/CTF fits well with the possible model (Fig. 2d). Subsequently, to more clearly discriminate the coordination atoms in the Mo species, EXAFS wavelet transform analysis was carried out (Fig. 2e). Intense Mo-N coordination, which is illustrated by red color, is observed in the WT contour plots of Mo-S-Mo/CTF at the radial distances of ~1.20 Å. Also, the weak Mo-Mo and Mo-S coordination can be observed in the WT contour plots of Mo foil and MoS2, which agrees with the results from EXAFS spectra. Additionally, DFT calculations reveal that the Mo-N bond energy in Mo-S-Mo/CTF (−10.66 eV) is significantly stronger than that of Mo-O (−6.22 eV), confirming that structural evolution favors the formation of Mo-N-coordinated “Mo-S-Mo” sites over Mo-O species during catalyst synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 17). Combined with XPS research for CTF and MoO3/CTF, the Mo-O species could be ruled out at Mo-S-Mo/CTF.

According to the above characterization results, it is evident that under high-temperature reducing conditions, the layered MoS2 is reduced by hydrogen to lose some sulfur atoms. Simultaneously, the Mo atom is anchored by two N atoms on the CTF, thereby forming the target Mo diatomic structure as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 18b. To validate the rationality of this structure formation, we further conducted theoretical calculations to estimate the energies required for the formation of various possible structures. Starting with the Mo2S4/CTF as the initial structure, three possible structures of Mo-S-Mo/CTF, Mo-S2-Mo/CTF, and Mo-Mo/CTF were investigated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Table 4, it was observed that the Mo-S-Mo/CTF structure had the lowest formation energy. In addition, we analyzed the projected density of states (PDOS) of Mo in Mo-S-Mo/CTF and MoS2/CTF models to study the d-band center. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20, the model of MoS2/CTF is composed of CTF and single-layer MoS2 with S vacancies, which are bound by van der Waals forces. The Mo-S-Mo/CTF features a Mo-S-Mo triatomic structure embedded within the CTF framework. Supplementary Fig. 21 exhibits the PDOS plots of Mo-S-Mo/CTF and MoS2/CTF. The DOS of Mo-S-Mo/CTF is closer to the molecular orbital due to its non-continuous Mo-S-Mo structure. Although this has limitations, compared with MoS2/CTF (−1.197 eV), the d-center of Mo-S-Mo/CTF shifts to higher energy levels near the Fermi level. This implies a lower valence state of Mo-S-Mo/CTF and a higher capacity for adsorption intermediates. Furthermore, it is found that the Bader charge of Mo binuclear in Mo-S-Mo/CTF are significantly different, being +1.03 e and +1.16 e. Different electronic states of Mo sites may endow synergistic effects on CO2 activation and H2 dissociation.

Catalytic performance of CO2 hydrogenation

The catalytic activities of the prepared catalysts for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation were evaluated in a fixed-bed reactor. Figure 3a illustrates the methanol synthesis rate over the Mo-S-Mo/CTF, MoS2/CTF, and MoS2 catalysts using a gas feed of CO2/H2 mixture with a 1/3 ratio at 1.5 MPa. It can be observed that Mo-S-Mo/CTF can catalyze the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol at even room temperature (30 °C). The corresponding methanol synthesis rate was measured to be 46.88 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1, which is significantly higher than that of the reference MoS2/CTF (3.13 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1), and MoS2 catalysts (0 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1). In addition, the catalytic activity of Mo-S-Mo/CTF demonstrated a notable enhancement with increasing reaction temperature. In the low-temperature range (30–120 °C), the net methanol yield of Mo-S-Mo/CTF is about nine times higher than that of MoS2/CTF (Fig. 3a). At 180 °C, the methanol synthesis rate of Mo-S-Mo/CTF has significantly increased to 4816.56 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1 (Fig. 3b). Moreover, Mo-S-Mo/CTF maintained the methanol selectivity of above 92% at a temperature range of 30–180 °C, which is also superior to that of the reference MoS2/CTF and MoS2 catalysts (Fig. 3c). The selectivity and product distributions at all temperatures are shown in Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23. Furthermore, under much milder reaction conditions (30 °C and 0.9 MPa), the methanol was produced with a synthesis rate of 21.88 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1. In addition, the reactivity of the MoO3/CTF was evaluated and found that it only begins to catalyze methanol formation under harsh conditions (220 °C, 1.5 MPa), achieving a mere 11.3 % methanol selectivity. Controlled Zn-doping experiments confirmed that Zn species play no promotional effect for methanol formation under mild conditions (Supplementary Table 5). This confirms that Mo-O species and Zn species are neither dominant in the Mo-S-Mo/CTF nor catalytically relevant. Supplementary Table 6 summarizes the methanol synthesis rate of Mo-S-Mo/CTF under various reaction conditions, along with those of the reported catalysts. Mo-S-Mo/CTF exhibits a methanol synthesis rate of 9.25 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1 at 30 °C, 0.9 MPa, and 30,000 mL gcat−1 h−1, which places it among the top-performing catalysts reported to date under comparable conditions.

The stability of the catalyst was examined by a long-time continuous reaction test. Both under 30 and 180 °C, the Mo-S-Mo/CTF produced methanol continuously without degradation over 120 h (Fig. 3d). Moreover, the tail gas from the fixed bed was also introduced into a U-shaped tube containing water, and samples were taken at 6 h and 48 h, respectively, for 1H NMR. It was observed that the signal intensity of methanol was significantly enhanced, indicating that CO2 hydrogenation produced methanol constantly with the extension of reaction time (Supplementary Fig. 24). To confirm whether there are any structural changes of the Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalyst after the reaction, we conducted the long-time stability test without using Al2O3 for dilution. From the stability reaction results (Supplementary Fig. 25), it was observed that during the reaction, both the methanol systhesis rate of the catalyst and the selectivity for methanol showed no significant changes. Structural characterizations (Supplementary Figs. 25–29) of the spent Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalyst further confirmed that there was no structure evolution during the reaction process. The above results indicate that Mo-S-Mo/CTF is a stable catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation methanol. Kinetic studies of CO2 hydrogenation further confirmed the superior catalytic performance of Mo-S-Mo/CTF. This catalyst exhibited a remarkably low apparent activation energy (Ea) of 24.8 kJ mol−1 in the low-temperature region (30–120 °C), substantially lower than both MoS2/CTF and MoS2 (Supplementary Fig. 30). However, its Ea increased to 42.6 kJ mol−1 in the high-temperature range (180–260 °C), suggesting potential changes in the reaction pathway with temperature. Notably, its low-temperature Ea is lower than the reported catalysts achieving room-temperature methanol synthesis (h-PdMo, 27 kJ mol−1)19. The minimal Ea at low temperatures underscores the capability of Mo-S-Mo/CTF to efficiently catalyze CO2 hydrogenation under exceptionally mild conditions, consistent with experimental observations.

Mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation

To obtain further insight into the CO2 activation and hydrogenation over Mo-S-Mo/CTF at low-pressure and ambient temperature, in-situ DRIFTS analysis was carried out under 1.5 MPa and 30 °C. Firstly, the catalyst was pretreated with atmospheric H2 at 300 °C for 120 min. Followed by cooling down to 30 °C and purging with mixed gas (CO2:H2 = 1:3) at 1.5 MPa, the spectrum was collected. As shown in Fig. 4a, the HCO3* species were first observed once the feed gas was introduced. The peaks located at 1683 and 1437 cm−1 were assigned to ionic bicarbonate species i-HCO3* and the peaks at 1634 and 1227 cm−1 to bidentate bicarbonate species b-HCO3*, respectively. Additionally, the CO3* was also detected at 1505 and 1261 cm−1. As the reaction proceeded, formate species (HCOO*) gradually appeared with peaks observed at 1600 cm−1, 1338 cm−1and 2955 cm−1, which were assigned to νas(OCO), δ(C-H), and δ(C-H)+ νs(OCO), respectively11,12. The higher band position at 1600 cm−1 compared to previous reports could be due to the formate adsorbed on single Mo sites11,26. The peaks at 1684 and 1146 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibration of the C=O and out-of-plane wagging vibration of C-H bonds in CH2O*, respectively. Meanwhile, vibration peaks assigned to ν(CO)-terminal, ν(CO)-bridge, νs(CH3), and νas(CH3) of CH3O*at 1039, 1144, 2843, and 2897 cm−1 were also detected11, indicating that methanol was produced at room temperature. Additionally, no CO* species was detected at 2000 to 2100 cm−1. Therefore, the pathway for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol in Mo-S-Mo/CTF primarily followed the formate route at room temperature.

We observed a notable increase in the reaction activity of Mo-S-Mo/CTF between 120 and 180 °C, suggesting potential shifts in reaction mechanisms at higher temperatures. Consequently, in-situ DRIFTS analysis was conducted at 150 °C and 1.5 MPa (Fig. 4b). The wide band between 1574 and 1684 cm−1, and a single peak at 1251 cm−1 were detected in the initial time, which were attributed to HCO3* and CO3* species. Interestingly, no significant presence of HCOO* species was observed around 1600 cm−1, unlike the spectrum observed at room temperature (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the appearance of a CO* band at 2081 cm−1 indicated the generation of CO* species at 150 °C. Other features observed at 1052, 1134, 1170, 2877, and 2937 cm−1 were associated with CH2O* and CH3O* species, suggesting the reaction pathways for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol via reverse water-gas shift (RWGS) at 150 °C. These findings indicate that CO2 activation and hydrogenation over Mo-S-Mo/CTF catalysts proceed via two distinct reaction pathways: the formate path at room temperature and the RWGS path at elevated temperatures. To gain further insights into the interplay between these pathways, in-situ DRIFTS of Mo-S-Mo/CTF were analyzed at varying reaction temperatures under normal pressure conditions. Supplementary Fig. 30 initially illustrates that the active species were primarily excited in HCO3* (1612 cm−1) at 30 °C due to the existence of surface hydroxyl groups. Formate species (HCOO*, 1594 cm−1) emerged at 60 °C, accompanied by a decrease in HCO3* signal intensity. Subsequently, the CO* band (2076 cm−1) was detected at 90 °C and intensified with rising temperatures, followed by the appearance of CH3O* (1087 cm−1) and CH2O* (1189 cm−1) until 120 °C. Remarkably, the distinctive C–H stretching vibrations (2868 and 2944 cm−1) characteristic of methanol were observed at 180 °C. These observations suggest that the facile formation of formate intermediates and their subsequent hydrogenation to methoxy may constitute the rate-determining step (RDS) for methanol production.

DFT calculations

To investigate the catalytic mechanism for S-bridged Mo binuclear sites towards CO2 hydrogenation, we carried out density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Figure 5 shows the calculated lowest-energy pathway for CO2 hydrogenation, which involves HCOO*, H2COO*, and CH3O* key intermediates. The reaction started with the dissociative adsorption of an H2 molecule on a Mo atom. Considering that the HCO3− and CO32- species detected by in-situ DRIFTS may also be in the initial state of the reaction, the in-situ DRIFTS of pristine CTF under CO2 has been carried out. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 32a, the wideband (1300 and 1450 cm−1) and single band (1610 cm−1) were attributed to νas(C-O) and νas(C–O), respectively, proving the CTF could adsorb CO2 as HCO3−27,28. Furthermore, the HCO3− could decompose to CO2 at Mo-S-Mo sites with a low barrier (0.03 eV), confirming that the HCO3− could rapidly desorb as CO2 and undergo the hydrogenation reaction (Supplementary Fig. 32b). The dissociation energy barrier of H2 is 0.453 eV, and then a CO2 molecule was adsorbed near the other Mo atom in a spontaneous process. While there were two possible channels for CO2 hydrogenation, that is, to HCOO* or COOH*, the results showed that the formation of the HCOO* group had a lower barrier of 0.174 eV, but the formation of the *COOH was difficult with a higher barrier of 1.32 eV (Supplementary Fig. 33). Thus, the pathway of further dissociation of *COOH into CO is more unfavorable. Furthermore, the CO pathway (direct CO2 dissociation to CO) has been investigated, as shown in the Supplementary Fig. 34. The results indicate that while the direct CO2 dissociation to CO is energetically favorable with a low barrier (0.11 eV), the subsequent formation of the *CHO intermediate has a significantly high energy barrier (2.45 eV), making this pathway unfavorable. The above results indicated that the formate pathway was the favorable route for CO2 hydrogenation on Mo-S-Mo/CTF, consistent with the results in the in-situ DRIFTS.

Then, the *HCOO intermediate undergoes hydrogenation to form H2COO, and then a second H2 molecule dissociated on the single Mo atom with nearly barrierless (0.108 eV). The O atom of the H2COO group could then be hydrogenated and broken with the carbon atom. The barrier of this step is 0.948 eV, higher than those of other steps (Fig. 5). At the same time, the third H2 molecule was adsorbed the neighboring Mo atom. The energy barriers to dissociate the third H2 and generate CH3O are 0.755 and 0.229 eV, respectively. The last step is the direct formation of free CH3OH instead of adsorbed CH3OH from CH2OH*, which would overcome the barrier of 0.049 eV and further release 0.545 eV energy. Based on the aforementioned results, we conclude that CO2 hydrogenation prefers to follow the formate pathway to form CH3OH on S-bridged Mo binuclear sites.

Discussion

This work presents a significant advancement in the field of CO2 hydrogenation into methanol under mild conditions by introducing sulfur-bridged Mo binuclear sites anchored onto covalent triazine frameworks as highly efficient catalysts. Through a simple top-down approach of thermal reduction of thinly dispersed MoS2 layers on CTF, a covalent triazine frameworks coordinated binuclear molybdenum catalyst (Mo-S-Mo/CTF) was successfully prepared. At 30 °C and 0.9 MPa, Mo-S-Mo/CTF exhibited remarkable performance for methanol production from CO2 hydrogenation, with a methanol synthesis rate of 21.88 μmol gMoSx−1 h−1 and 96 % methanol selectivity. In-situ spectroscopic analysis elucidated the reaction pathways, showing that the catalyst favors the formate pathway at low temperatures and reverses to CO pathway at elevated temperatures. Further DFT investigations indicate that the reaction tends to follow the formate path with a lower barrier of 0.948 eV. Overall, this work provides a promising strategy for efficient CO2 hydrogenation to methanol under room temperature, and sheds interesting light on the development of catalysts based on the in-depth reaction mechanism.

Methods

Synthesis of Mo-S-Mo/CTF and MoS2/CTF

The 2,6-pyridinedicarbonitrile (2,6-DCP) derived covalent triazine frameworks (CTF) were synthesized using ion-thermal synthesis as reported23. Specifically, 3 g of 2,6-DCP and 15 g of anhydrous ZnCl2 were mixed in a glove box under inert gas. The mixture was then transferred into a Pyrex ampule, which was evacuated, sealed, and heated to 400 °C for 20 h and then to 600 °C for another 20 h. After cooling to room temperature and carefully opening, the reaction mixture was ground. It was washed with large amounts of water to remove most of the ZnCl2 and further stirred in 2 M diluted HCl for 12 h to eliminate residual salt. The resulting black powder was filtered, successively washed with water, and dried in a vacuum at 150 °C for 12 h. The MoS2 was prepared by using the hydrothermal method. In detail, ammonium molybdate and thiourea were first dissolved in water and mixed at a ratio of 1:2 (mol/mol), followed by adding the CTF powder in a hydrothermal reactor. The catalysts were named Mo-S-Mo/CTF and MoS2/CTF with theoretical mass ratios of MoS2:CTF = 1:10 and 1:5, respectively. After being maintained at a temperature of 200 °C for 22 h, the reaction mixture was centrifuged 2 times with H2O at 5000 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently, the synthesized material at 80 °C for 14 h under a vacuum. Before evaluating CO2 hydrogenation, the catalyst was reduced in a hydrogen atmosphere at 300 °C for 150 min with a flow speed of 20 mL min−1.

Synthesis of MoO3/CTF

48 mg sodium molybdate was dissolved in 160 mL of deionized water under stirring, and then 2 M HCl (4.8 mL) was added, followed by stirring for about 30 min until the solution became homogeneous. After 200 mg CTF was added into the solution under stirring, the obtained solution was transferred into a 200 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave. The autoclave was kept at 180 oC for 24 h in an oven and then cooled to room temperature. The product was washed with H2O and dried at 80 oC.

Catalyst Characterization

The actual loadings of the noble metals were determined by using inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) on an IRIS intrepid II XSP instrument (Thermo Electron Corporation). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source. The in-situ XRD were collected in a homemade chamber. The sample was heated in H2 flow (50 mL min−1) at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. After the inner temperature of the chamber reached 300 °C, the XRD patterns were recorded. The quasi in-situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) data were collected using a Thermo Fisher ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer with a monochromatized Al Kα X-ray. The beam diameter was 500 um, and the acceleration voltage was 15 kV. After recording the spectra of the fresh catalyst in the analyzer chamber, the sample was transferred into the preparation chamber to do the reduction. The sample was heated in 20% H2-Ar flow (50 mL min−1) at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. After the inner temperature of the preparation chamber reached 300 °C and was maintained for 3 h, the sample was cooled to 30 °C under constant N2 flow (50 mL min−1). The reduced sample was directly returned to the analyzer chamber without exposure to air, and XPS data were recorded. The X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) were collected at BL 11B station in the Shanghai synchrotron radiation Facility (BSRF 1W1B). A pair of channel-cut Si (111) crystals were used in the monochromator. The spectra were recorded at room temperature in the fluorescence mode with a solid-state detector. The Athena software package was used for the data analysis. High-resolution resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) analysis was performed by using a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 instrument operated at 200 keV. Aberration correction high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) images were obtained with a JEOL JEM-ARM200F STEM/TEM system at a guaranteed resolution of 0.08 nm.

Catalytic tests

The CO2 hydrogenation was performed in a silica-glass fixed bed reactor. Mix and grind the catalyst and alumina in a mass ratio of 1 to 10 for granulation. The 100 mg sample was pre-treated in H2 at 300 °C for 150 min. The reaction was performed in a flow of CO2-H2 (1:3, 30 mL min−1), and the outlet gaseous was analyzed using a gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a flame ionization detector (FID). A PONA capillary column was connected to the FID for methanol analysis. The catalytic performances during the stable phase of the reaction were typically used for discussion. The reaction parameters including methanol synthesis rate, and product selectivity were calculated as follows:

where cMeOH is the concentration of methanol at the outlet of the reactor, V is the flowing rate of the outlet gas, and mMoSx is the weight of Mo element and S in the catalyst. nproduct is the amount of product (mol) (including CH3OH, CO and CH4) at the outlet of the reactor.

Computational methods

All DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP version 6.1.2)29,30,31 and the CP2K software (version 2023.2)32,33,34. The electronic structures and density of states (DOS) were calculated using VASP with projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials35,36. For the calculations using VASP, the exchange-correlation potential energy was described using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional37. The van der Waals interactions were corrected using Grimme’s semiempirical D3 dispersion correction scheme38,39. A kinetic energy cutoff of 520 eV and 1 × 1 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh for sampling the Brillouin Zone were adopted. The electronic energies satisfied the convergence criteria of 10−6 eV. All the structures were relaxed until the force on each ion was less than 0.02 eV/Å. Due to the large scale of the models, we used CP2K to calculate the reaction paths. For the calculations using CP2K, the PBE exchange-correlation functional, along with Goedecker–Teter–Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials40, was utilized. DZVP-MOLOPT-SR-GTH basis sets were employed41. The computational cell was defined with dimensions A = 25.282 Å, B = 21.895 Å, and C = 35.229 Å for periodic boundary conditions. Geometry optimizations and transition state locations were carried out using a conjugate gradient (CG) optimizer42, with the convergence criteria being a maximum force of 4.5 × 10−5 eV/Å and a root mean square force of 3.0 × 10−4 eV/Å. The SCF calculations were constrained by a tolerance of 10−6 Hartree, with a maximum of 25 iterations allowed for inner SCF cycles and 20 for outer SCF cycles. The Grimme’s DFTD3(BJ) correction was applied for correcting van der Waals interactions38,39. Gaussian smearing, with a width of 0.05 eV, was used for the treatment of electronic states. The transition state structures were investigated using the Climbing Image-Nudged Elastic Band (CI-NEB) method43, involving five replicas and a spring constant of 0.05, to ensure the precise determination of energy barriers. Data analysis and visualization were conducted using VESTA 3.5.844 and OVITO 3.10.445 to assess electronic and structural properties. Input files were generated using Multiwfn 3.846.

Data availability

All the data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Any additional information can be requested from the corresponding authors [G.R. and W.D.]. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

He, M., Sun, Y. & Han, B. Green carbon science: scientific basis for integrating carbon resource processing, utilization, and recycling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 9620–9633 (2013).

Ye, R.-P. et al. CO2 hydrogenation to high-value products via heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Commn. 10, 5698 (2019).

Jiang, X., Nie, X., Guo, X., Song, C. & Chen, J. G. Recent advances in carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol via heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 7984–8034 (2020).

Navarro-Jaen, S. et al. Highlights and challenges in the selective reduction of carbon dioxide to methanol. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 564–579 (2021).

Kattel, S., Liu, P. & Chen, J. G. Tuning selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation reactions at the metal/oxide interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9739–9754 (2017).

Xiao, S. et al. Highly efficient Cu-based catalysts via hydrotalcite-like precursors for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Catal. Today. 281, 327–336 (2017).

Cai, Z. et al. Fabrication of Pd/In2O3 nanocatalysts derived from MIL-68(In) loaded with molecular metalloporphyrin (TCPP(Pd)) toward CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. ACS Catal. 12, 709–723 (2022).

Bahruji, H. et al. Pd/ZnO catalysts for direct CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. J. Catal. 343, 133–146 (2016).

Bai, S.-T. et al. Homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts for hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol under mild conditions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4259–4298 (2021).

Yang, T. et al. Coordination tailoring of Cu single sites on C3N4 realizes selective CO2 hydrogenation at low temperature. Nat. Commn. 12, 6022 (2021).

Feng, Z. et al. Asymmetric sites on the ZnZrOx catalyst for promoting formate formation and transformation in CO2 hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12663–12672 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Optimizing reaction paths for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation via metal-ligand cooperativity. Nat. Commn. 10, 1885 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. The role of Cu1-O3 species in single-atom Cu/ZrO2 catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 5, 818–831 (2022).

Wu, W. et al. CO2 hydrogenation over copper/ZnO single-atom catalysts: water-promoted transient synthesis of methanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213024 (2022).

Zou, R. et al. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over the copper promoted In2O3 catalyst. J. Energy Chem. 93, 135–145 (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Engineering the Cu/Mo2CTx (MXene) interface to drive CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nat. Catal. 4, 860–871 (2021).

Len, T. & Luque, R. Addressing the CO2 challenge through thermocatalytic hydrogenation to carbon monoxide, methanol and methane. Green Chem. 25, 490–521 (2023).

Cannizzaro, F., Hensen, E. J. M. & Filot, I. A. W. The promoting role of Ni on In2O3 for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. ACS Catal. 13, 1875–1892 (2023).

Sugiyama, H., Miyazaki, M., Sasase, M., Kitano, M. & Hosono, H. Room-temperature CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over air-stable hcp-PdMo intermetallic catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9410–9416 (2023).

Kanega, R., Onishi, N., Tanaka, S., Kishimoto, H. & Himeda, Y. Catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol using multinuclear iridium complexes in a gas-solid phase reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1570–1576 (2021).

Hu, J. et al. Sulfur vacancy-rich MoS2 as a catalyst for the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Nat. Catal. 4, 242–250 (2021).

Ren, G. et al. Ambient hydrogenation of carbon dioxide into liquid fuel by a heterogeneous synergetic dual single-atom catalyst. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100705 (2022).

Zhai, S. et al. Heteronuclear dual single-atom catalysts for ambient conversion of CO2 from air to formate. ACS Catal. 13, 3915–3924 (2023).

Feng, W. et al. Flower-like PEGylated MoS2 nanoflakes for near-infrared photothermal cancer therapy. Sci Rep. 5, 17422 (2015).

Gunasekar, G. H., Shin, J., Jung, K.-D., Park, K. & Yoon, S. Design strategy toward recyclable and highly efficient heterogeneous catalysts for the hydrogenation of CO2 to Formate. ACS Catal. 8, 4346–4353 (2018).

Han, X. et al. Synergetic interaction between single-atom Cu and Ga2O3 enhances CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over CuGaZrOx. ACS Catal. 13, 13679–13690 (2023).

Zou, W. et al. Metal-free photocatalytic CO2 reduction to CH4 and H2O2 under non-sacrificial ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313392 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Cayanamide group functionalized crystalline carbon nitride aerogel for efficient CO2 photoreduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312634 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Hutter, J., Iannuzzi, M., Schiffmann, F. & VandeVondele, J. cp2k: atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.-Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 15–25 (2014).

Kühne, T. D. et al. CP2K: an electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package-Quickstep: efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 194103 (2020).

Borštnik, U., VandeVondele, J., Weber, V. & Hutter, J. Sparse matrix multiplication: the distributed block-compressed sparse row library. Parallel Comput. 40, 47–58 (2014).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703 (1996).

VandeVondele, J. & Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 114105 (2007).

Shewchuk, J. R. An introduction to the conjugate gradient method without the agonizing pain. Technical Report. (Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1994).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO-the Open Visualization Tool. Model Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2009).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFA1503104), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22308193), Taishan Scholars Project (No.tspd20230601), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020QB056), and Shandong University Future Program for Young Scholars (No. 62460082164128, No. 62460082064083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.D. and G.R. conceived the concept and design research. S.Z., X.G. and C.Y. carried out the catalyst synthesis, characterization, and catalytic test. D.Z., Y.P. and L.Y. executed the theoretical calculations. T.Y. carried out part of the characterization and catalytic test.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xinwen Guo, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhai, S., Pan, Y., Yang, C. et al. Room-temperature methanol synthesis via CO2 hydrogenation catalyzed by cooperative molybdenum centres in covalent triazine frameworks. Nat Commun 16, 7876 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63191-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63191-x