Abstract

Topological electronic crystals are electron crystals in which spontaneously broken translation symmetry coexists with or gives rise to a nontrivial topological response. Here, we introduce a novel platform and analytical theory for realizing interaction-induced Hall crystals, a class of topological electronic crystals, with various Chern numbers C. The platform consists of a two-dimensional semiconductor subjected to an out-of-plane magnetic field and one-dimensional modulation, which can be realized by moiré or dielectric engineering. Interactions drive the system to spontaneously break the residual translational symmetry, resulting in anisotropic Hall crystals with various C, including ∣C∣ > 1, tunable by field. Remarkably, these persist across continuous ranges of filling and field, and the global phase diagram can be understood in a unified manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two-dimensional electronic systems in a strong magnetic field display a rich interplay between charge density wave (CDW) and quantum Hall phases. In the lowest Landau level, Wigner crystals compete with fractional quantum Hall (FQH) states at low fillings1,2,3. Even more interesting is the theoretical prediction that crystalline order and the quantized Hall effect may coexist, leading to a novel quantum phase of matter referred to as the Hall crystal4.

Besides exhibiting a topologically quantized Hall effect, the most striking fact about Hall crystals, first noted by Halperin et al.5, is that the number of electrons per unit cell can vary continuously, as can the number of flux quanta per unit cell. However, they satisfy a definite relation, the Diophantine relation5, which relates them to rational topological invariants such as the many-body Chern number C. The Hall conductivity of the Hall crystal (pinned by an infinitesimal potential) is \({\sigma }_{H}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{h}\frac{\partial \bar{\rho }}{\partial {\rho }_{\Phi }}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{h}C\)6,7.

The study of Hall crystals was initially motivated by the Wigner-crystal-to-FQH transition at low fillings of the lowest Landau level (LL)4,5,8. Later, Hartree-Fock studies revealed crystalline electron phases in partially filled higher LLs9,10,11,12, which also exhibit a quantized Hall effect due to the completely filled LLs. Recent observations of quantum anomalous Hall (QAH) states in moiré materials13,14,15 have sparked great interest in “anomalous” Hall crystals16,17,18,19,20,21,22, requiring no external magnetic field. Indeed, evidence of a QAH crystal with C = 1 has been observed at fractional filling of twisted bilayer-trilayer graphene23.

Existing studies of (anomalous) Hall crystals have largely focused on states with unit many-body Chern number ∣C∣ = 1 arising from a partially filled Landau level or Chern band. An intriguing research direction is the study of Hall crystals with ∣C∣ > 1, which we dub higher Hall crystals. Such states have not been observed in the ordinary quantum Hall effect and may exhibit interesting new physics when interactions are present. The remarkable tunability and customizability of two-dimensional materials further motivate the search for such phases.

In this work, we introduce a realistic and tunable platform for Hall crystals with various, unexpected many-body Chern numbers. By controlled analysis, we show that these reliably emerge from generic electron interactions in an engineered setting. For instance, we find a C = 1 Hall crystal over a range of Landau level fillings ν < 1/2.

Our platform consists of a 2D semiconductor or graphene subject to an out-of-plane B field and a one-dimensional superlattice potential V(x), as shown in Fig. 1. Our proposal is straightforward to implement with patterned dielectrics or bottom gates, as demonstrated by several experiments (e.g.24,25). For example, the observation of Weiss oscillations suggests that these systems are well-captured by LLs modulated by a periodic potential, our analytical starting point24,25,26,27,28.

The proposed platform is an active semiconductor or graphene layer with free charge carriers subject to a uniform field \(B\hat{z}\) and a 1D modulation V(x) from a patterned substrate. Electron interactions drive CDW formation along the y direction resulting in Hall crystals with various Chern numbers.

Here, we show that Coulomb interactions in such periodically modulated LLs induce various CDW instabilities that spontaneously break the continuous translation symmetry along y and lead to an intricate phase diagram, featuring Hall crystals with diverse Chern numbers.

Results

Setup and model

We start by considering Landau levels (LLs) of a two-dimensional electron system subject to a one-dimensional periodic potential V(x). We decompose the potential into harmonics as \(V(x)=\sum _{i}{V}_{i}\cos ({q}_{i}x)\) and consider strong magnetic fields ∣Vi∣ ≪ ωc = B/m (e = ℏ = 1). To first order in Vi/ωc, LL mixing can be neglected and the energy spectrum of the n-th LL becomes dispersive as a function of ky:

with \(\ell=1/\sqrt{B}\) the magnetic length, while remaining flat as a function of kx. This quasi-1D energy dispersion is a consequence of the locking between electron position x and momentum ky in a LL. Indeed, in the high field limit ℓ → 0, En(ky) = V(x = kyℓ2) exactly traces the potential landscape.

In the presence of electron interactions, the LL-projected Hamiltonian can naturally be written in the Landau gauge basis, taking the form (dropping the y subscripts from now)

where \({c}_{n,k}^{\dagger }\) is the creation operator for the Landau gauge orbital \({\varphi }_{n,k}(\overrightarrow{r})=\frac{1}{\sqrt{{L}_{y}\ell \sqrt{\pi }{2}^{n}n!}}{e}^{-iky}{H}_{n}((x-k{\ell }^{2})/\ell ){e}^{-{(x-k{\ell }^{2})}^{2}/2{\ell }^{2}}\) and \({U}_{{k}_{1},\ldots,{k}_{4}}\) is a projected interaction matrix element.

We now analyze our setup microscopically. For the purpose of a rigorous analytical treatment, we assume that the interaction energy scale is small compared to the bandwidth W ~ ∣V∣ of the modulated LL (which is in turn much smaller than the cyclotron energy ωc). In this weak interaction regime, let us first consider the effect of the energy dispersion H0. When the n-th LL is partially filled, low-energy electron states are one-dimensional chiral modes associated with equipotential lines of En(k) = μ with μ the chemical potential, forming an array of 1D chiral fermion wires along the y direction (see Fig. 2). These wires have alternating chiralities and spacings δa0 and (1 − δ)a0, where a0 is the period of V(x), and δ increases with the LL filling factor ν from 0 to 1. For example, in the case of a sinusoidal potential \(V(x)=V\cos (2\pi x/{a}_{0})\), δ = ν, the positions are xI = a0(⌊(I − 1)/2⌋ + 1/2 + (−1)Iν/2) (This also holds for any periodic V(x) with a single local maximum and local minimum per unit cell coincident with those of \(\cos (2\pi x/{a}_{0})\).) and the velocities are \({v}_{I}= {\frac{\partial {E}_{n}}{\partial {k}_{y}}}\vert _{{k}_{I}}\equiv {(-1)}^{I}v\) (with v > 0). Even (odd) wire index corresponds to a positive (negative) velocity along the y direction.

The active degrees of freedom are particle-hole excitations near the Fermi level, with the bulk electrons far below the Fermi level frozen due to Pauli blocking. In analogy with the standard treatment of quantum wires, the low-energy theory can be expressed in terms of the chiral fermions \({\psi }_{I}=\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{{k}_{I}-\Lambda }^{{k}_{I}+\Lambda }\frac{dk}{2\pi }{e}^{-iky}{c}_{n,k}\), where I = 1, …2N and N → ∞ in the thermodynamic limit. By retaining only terms involving low-energy chiral fermions ψI in H, we obtain the effective Hamiltonian

(kI ~ I) where indices are implicitly summed. Since our setup has translation symmetry along the y direction, Heff satisfies momentum conservation

This, along with charge conservation, places important kinematic constraints on the effective theory: allowed interactions in Heff are correlated hoppings of a pair of opposite-chirality fermions (I0, J0) → (I0 − l, J0 + l). They can all be written as

where I0 < J0, \({J}_{0}-{I}_{0}\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,2=1\) and l≥0. Such terms preserve the center-of-mass position along x direction as required by y momentum conservation.

The l = 0 terms, which we refer to as forward scattering, conserve the number of electrons in each wire and have coefficient

Importantly, both direct and exchange interactions involving momentum transfer q ~ 0 and kJ − kI contribute to the forward scattering process \({{\mathsf{U}}}_{IJ}\). The l ≠ 0 terms will be referred to as correlated hoppings.

CDW orders and Hall crystals

An array of coupled quantum wires is generically unstable to interactions29,30,31,32. Before analyzing the exact order realized for a given set of microscopic parameters, we discuss general features of the ordered phases associated with interactions such as \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{{I}_{0},{J}_{0},l}\). In the thermodynamic limit, \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{{I}_{0},{J}_{0},l}\) and its unit-cell-translated copies induce long-range order for the CDW order parameter \({\psi }_{{I}_{*}}^{\dagger }{\psi }_{{J}_{*}}\), where I* ∈ {J0 + l, I0 − l} and J* ∈ {I0, J0} are such that \({I}_{*}-{J}_{*}\,\mathrm{mod}\,\,2=1\). From the density operator \(\rho (y) \sim \sum _{I,J}{\psi }_{I}^{\dagger }{\psi }_{J}{e}^{i({k}_{I}-{k}_{J})y}\), we deduce that the CDW has wavevector \(Q=| {k}_{{I}_{*}}-{k}_{{J}_{*}}| \) along the y direction. In particular,

In general, the resulting CDW is topological. One indication is the presence of Nedge gapless edge modes on a system with a boundary along x. Equivalently, Nedge is the number of wires left “untouched” by the operator Eq. (5) and its translated copies. Some careful counting shows that Nedge takes the values shown in Table 1.

This implies that the CDW can carry a nontrivial Chern number. Indeed, the state is a Hall crystal, as we now show. We employ a relation between density, field, and unit cell area in crystalline Hall systems, with A0 = (2π/Q)a0. All these quantities can vary continuously but satisfy the Diophantine relation

where \(\bar{\rho }\) is the electron density, ρΦ = 1/2πℓ2 is the LL degeneracy per unit area, and in the presence of an infinitesimal gap opening, the insulating state has Hall conductance \({\sigma }_{xy}=C\frac{{e}^{2}}{h}\) by the Streda formula. This implies, for our case,

Q can be deduced across various cases using Eq. (7), and we record the results in Table 1. Putting this together, we may observe that Eq. (9) is satisfied precisely with \(\eta={(-1)}^{{I}_{0}-l-1}\) and

a nontrivial agreement necessitated by the bulk-boundary correspondence. Moreover, we can compactly express the wavevector as

We further detail the nature of these phases in (See Supplemental Material, which includes details on the bosonization procedure, strong coupling phases, and phase diagrams.). The simplest cases are the C = 0 and C = 1 insulators (shown in Fig. 2a) which correspond to (I0, J0, l) = (even/odd, I0 + 1, 1), respectively. In other words, these correspond to strong backscattering between adjacent wires. Naïvely, we may expect that a C = 0 or C = 1 state is always preferred. While this is indeed the case in the limit of tightly localized wires ℓ/a0 → 0, we will show that, surprisingly, various other Hall crystals are stabilized under general assumptions.

Let us comment on the nature of the CDW phases at special rational conditions. From Eq. (11), it follows that a scenario with both a rational flux per unit cell Φ0 = a0/Qℓ2 and rational filling ν can be achieved. For instance, this could arise for Φ0 = s/t and ν = r/s given integers r, s, t. These integers must then satisfy t/s = η(r/s − C), which is equivalent to the noninteracting Diophantine equation

which was shown in ref. 6 to hold for a Landau level subject to a periodic potential \({U}_{1}\cos (2\pi x/{a}_{0})+{U}_{2}\cos (Qy)\) with U2 ≪ U1, and precisely Φ0 = s/t, ν = r/s. Indeed, σH = Ce2/h in this context as well, which famously follows from the Kubo formula6.

Methods and phase diagram

In order to determine the CDW order for a given set of microscopic parameters, we proceed to solve the low-energy model of coupled wires, which describes our modulated LL system at weak interaction (compared to the bandwidth). We will bosonize each wire and apply a perturbative renormalization group analysis.

We now treat the system by bosonization: a chiral boson field ϕI is introduced for each wire via \({\psi }_{I}={(2\pi \alpha )}^{-1/2}{e}^{i{k}_{I}y}{e}^{{(-)}^{I}i{\phi }_{I}}{\gamma }_{I}\), where α is a short-distance cutoff and γI is a Klein factor29,30,31,32. The quadratic action is

where \({{\mathsf{K}}}_{IJ}={(-)}^{I+1}{\delta }_{IJ}\) and \({{\mathsf{V}}}_{IJ}=v{\delta }_{IJ}+(1/\pi ){{\mathsf{U}}}_{IJ}\). (More details on the bosonization procedure can be found in (See Supplemental Material, which includes details on the bosonization procedure, strong coupling phases, and phase diagrams.).) The action Eq. (13), describing a sliding Luttinger liquid with forward scattering interactions between wires31, is an RG fixed point parametrized by \({\mathsf{V}}\).

We proceed to study the effect of the remaining interactions (i.e. correlated hoppings) on these fixed points. A general type of symmetry-allowed perturbation takes the bosonized form

where \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{{I}_{0},{J}_{0},l}\), defined in Eq. (5), has bosonized form

with

It is important to note that Eq. (14) is a sum of local operators that are mutually commuting.

At the fixed point, if only a single type of correlated hopping Eq. (14) is present, the system develops the corresponding CDW order with wavevector given by Eq. (11). However, because all types of correlated hoppings with different I0, J0, l are present for generic interactions, the situation is more complicated. We proceed by searching for the most relevant instability among all types of correlated hoppings, which indicates the strongest ordering tendency at any given set of microscopic parameters.

To proceed, we take the bare electron-electron interactions to be of Coulomb form, which upon projection to the LL yield matrix elements \({U}_{I{I}^{{\prime} }{J}^{{\prime} }J}={L}_{y}\left\langle I{I}^{{\prime} }\right\vert {\hat{V}}_{C}\left\vert {J}^{{\prime} }J\right\rangle \), where \(\left\vert I\right\rangle \) denotes a Landau gauge orbital. For \({\hat{V}}_{C}\), we consider both long-range and gate-screened Coulomb interactions \({V}_{C}(\overrightarrow{r})=({e}^{2}/\epsilon r){e}^{-r/\lambda }\), where ϵ is the dielectric constant and λ is a screening length. Writing \({k}_{{I}^{{\prime} }}-{k}_{I}=q,{k}_{{J}^{{\prime} }}-{k}_{J}=p\), we have (See Supplemental Material, which includes details on the bosonization procedure, strong coupling phases, and phase diagrams.)

for the lowest LL, where K0 is a modified Bessel function of the 2nd kind and

The \({{\mathsf{U}}}_{IJ}\) depend on a0 and ν through the positions of the wires. We show an example of \({\mathsf{U}}\) in Fig. 3a.

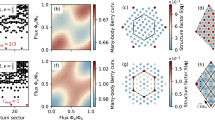

a Density-density couplings \({{\mathsf{U}}}_{IJ}/v\) (dots) and projected lowest LL interactions (line) as functions of interwire separation. The origin, indicated by 0, is a wire I0 with I0 odd. Symbols indicate (a0, ν) values in (b). b Phase diagram of lowest LL modulated by a periodic potential V(x) in a field B with short range Coulomb interactions (\({B}_{0}=1/{a}_{0}^{2},\lambda=\ell \)). Phases labelled by Chern numbers C; each phase has wavevector Q (Eq. (11)) and η = − sgn(C). c Heuristic depiction of charge density of in the smectic metal (left) and Hall crystal (right) phases at ν = 1/3.

Next, we generate a phase diagram by finding the most relevant instability Eq. (15) at the fixed point defined by \({S}_{{\rm{eff}}}[{\mathsf{V}}]\), with \({\mathsf{V}}\) set by microscopic parameters, and present the results in Fig. 3. To this end, we need to find scaling dimensions of the operators \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{{I}_{0},{J}_{0},l}\). In the absence of interactions, the scaling dimension is simply \(\frac{1}{2}{\overrightarrow{m}}^{T}\overrightarrow{m}=2\), as appropriate for a four-fermion operator. When \({\mathsf{U}}\) is nonvanishing, we may perform a field redefinition \({\phi }_{I}^{{\prime} }={{\mathsf{A}}}_{{I}^{{\prime} }I}{\phi }_{I}\) with \({\mathsf{A}}\) chosen such to diagonalize the interactions while maintaining the commutation relations; in particular, we may take any \({\mathsf{A}}\) satisfying \({\mathsf{A}}{\mathsf{V}}{{\mathsf{A}}}^{T}=\,\text{diag}\,({u}_{i})\), \({\mathsf{A}}{\mathsf{K}}{{\mathsf{A}}}^{T}={\mathsf{K}}\), and \(\det {\mathsf{A}}=1\)33. It then follows that operator \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{{I}_{0},{J}_{0},l}\) has scaling dimension \(\Delta=\frac{1}{2}{\overrightarrow{m}}^{T}{{\mathsf{A}}}^{T}{\mathsf{A}}\overrightarrow{m}\). We note that the \({{\mathcal{O}}}_{{I}_{0}+2j,{J}_{0}+2j,l}\) mutually commute for all j, indicating that they may gap out the bulk in a manner preserving the discrete translation symmetry along x34.

We systematically searched for the most relevant instability on a system of N = 300 wires to generate the phase diagram Fig. 3b. At each set of microscopic parameters we tested, the Chern number agreed among the most relevant instabilities. The phase diagram reveals the formation of Hall crystals with various Chern numbers as filling and moiré period are varied. The system has a particle-hole × inversion symmetry which manifests as a symmetry under ν → 1 − ν, C → 1 − C. In Fig. 3c we visualize the mean-field charge density profile at Φ0 = 3/2, ν = 1/3 by solving the noninteracting problem with both U2 = 0 and U2/U1 = 0.2, a heuristic depiction of “before and after" interactions are switched on.

When \(B/{B}_{0}\equiv {({a}_{0}/\ell )}^{2}\gg 1\), modes are well-localized to the wires and C = 0 or C = 1 phases dominate. These both arise from backscattering between nearest neighbor pairs as in Fig. 2. The C = 1 state has an unpaired chiral mode on a system with left or right termination.

As B decreases, the magnetic length becomes larger and the wavefunctions in several adjacent unit cells strongly overlap, allowing longer-range hoppings. Interestingly, the Chern number of the Hall crystal concurrently grows in magnitude. For instance, when ν < 1/2, we observe a sequence C = 0, 1, − 1, 2, − 2 for decreasing a0/ℓ. We have thus demonstrated by a controlled analysis the possibility of higher Hall crystals. This sequence extends, though not exactly, down to smaller fields.

A simple explanation for this is that the system tends to choose its Chern number according to the rule of thumb Qℓ ≈ c*, where c* is a nonuniversal O(1) constant depending on the interactions. We can reproduce the phase diagram quite well by minimizing ∣Qℓ − c*∣ for c* ≈ 1.0, with analogous phase diagrams for higher-n Landau levels taking \({c}_{*}\approx 1/\sqrt{n}\), as we show in the Supplemental Material (See Supplemental Material, which includes details on the bosonization procedure, strong coupling phases, and phase diagrams.). The precise value of c* depends on the form factor \({U}_{I{I}^{{\prime} }J{J}^{{\prime} }}\), but not on a0/ℓ or ν. Thus we can efficiently predict the Hall crystal phase diagram for a wide range of systems simply by specifying c* and applying a rule of thumb: minimize ∣Qℓ − c*∣ using \(Q=\frac{{a}_{0}}{{\ell }^{2}}| C-\nu | \).

The analytical structure borne out of the physical setup proposed above bears a resemblance to the phenomenological coupled wire construction of fractional topological phases (e.g. refs. 34, 35). By contrast, we analyze a physically accessible scenario, starting with a spatially modulated Landau level, and treat realistic microscopic interactions, focusing on the CDW instabilities. The relation to prior works opens the door to studying more exotic phases in our current setup, including FQH states, anyon crystals, and superconductors. These instabilities may require higher-fermion operators (e.g. a six-fermion operator for the Laughlin state) to become the most relevant, and hence a strong coupling approach is necessary36. Competition with so-called FQAH crystals37,38 presents an additional interesting avenue for further study.

Discussion

In summary, we have proposed an experimentally accessible platform to realize anisotropic Hall electronic crystals with various Chern numbers, namely a two-dimensional semiconductor (e.g. a transition metal dichalcogenide or GaAs layer) or graphene in a strong field and 1D modulation. This provides the first analytically controlled route to a novel kind of Hall crystals, whereas previous studies on intrinsic 2D Hall crystals rely on uncontrolled Hartree-Fock calculations or invoke unrealistic interactions5,39. Interestingly, our work shows that by subjecting Landau levels to a 1D periodic modulation, the resulting interaction-induced Hall crystals can have higher, or even sign-flipped, Chern numbers.

In particular, a patterned dielectric substrate or back gate with an etched 1D superlattice24,25,26,27 may help to unlock these phases. Signatures of these phases occur when \(B{a}_{0}^{2} \, \lesssim \, 10\). Dielectric etching or e-beam lithography can produce periods down to a0 ~ 35 nm27 or ~ 10 nm, respectively, and thus the required B fields are entirely realistic. Weak interactions (which may not necessarily be a requirement) can also be achieved; in graphene, for instance, interwire interactions can be e2/ϵrϵ0a0 ~ 5 meV for ϵr = 10 and a0 = 35 nm, while ℏωc can reach 50 meV. Interaction strength is further tunable by dielectric environment. In contrast to previously studied examples of Hall crystals, the crystals in our setup would have a strong anisotropy which we expect to be present in any observable.

The relevant experimental platforms may deviate in a few ways from the pristine model considered here. First, the superlattice may only have an approximate periodicity a0 due to strain variations or patterning imprecision. In this case, many instabilities considered herein would fail to conserve the dipole symmetry, increasing the likelihood of a stable smectic metal. Second, defects, disorder, or an underlying y modulation may spoil the translation symmetry, in which case fermion bilinears \({\psi }_{I}^{\dagger }{\psi }_{J}\) may trigger an instability to a 2D Fermi liquid. The temperature scale for this, however, is exponentially small in the perturbation strength. Finally, higher harmonics \(\cos (m{q}_{0}x)\) may be present in V(x), but their contributions are strongly suppressed in a B field by \({e}^{-{m}^{2}{q}_{0}^{2}{\ell }^{2}/4}\), and hence they typically do not alter the physics; thus adherence to \(V(x)={V}_{0}\cos ({q}_{0}x)\) is unnecessary.

Moreover, a physical magnetic field may not be a strict requirement. Strain engineering in graphene can produce pseudomagnetic fields of order 100 T40, whose alternating pattern naturally gives rise to an array of 1D snake states41,42. Generic Chern bands subject to a 1D periodic potential should also exhibit an array of 1D edge states. In our context, these states could serve as chiral modes whose interactions may drive (anomalous) Hall crystal formation, though a careful study is required of competing 2D Fermi liquid instabilities. An interesting future direction is the extension of the current work to zero field settings.

Correlated crystals with variable Chern numbers, tunable by field and moiré period, are the central features predicted in this work. Their predominance in the phase diagram, which was recovered as a weak coupling instability, is nevertheless expected to be even more robust. Moreover, we note the intriguing existence of scenarios where a 1d modulation forms spontaneously, such as in stripe phases of higher Landau levels. We reveal here that this spontaneous modulation may be a precursor to the formation and promotion of more conventional Hall crystals. Their phenomenology presents a fascinating direction for future studies, particularly at strong interaction, where competition with FQH phases34,35,36,37 becomes important. These Hall crystals may be topological cousins of the bubble phases in higher Landau levels, which also form with lattice constant of approximately the cyclotron radius9.

The higher Chern numbers also raise the prospect for interesting new physics. For instance, novel FQH states in Chern C bands are expected at fillings ν = r/(2r∣C∣ + 1)43 which could give rise to unexpected Hall conductivities. Another possibility is that defects in higher Chern states, known as genons44,45, are endowed with nontrivial (even non-abelian) statistics, which could possibly be probed by STM46. Finally, the phases engineered in this work could have secondary instabilities towards generalized charge density waves47,48 with C × C expanded unit cells.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings in this work are publicly available online at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16755488.

Code availability

The code used to generate the data and figures appearing in this work is available online at https://github.com/nisargapaul/hall-crystals.

References

Stormer, H. L., Tsui, D. C. & Gossard, A. C. The fractional quantum Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 71, S298–S305 (1999).

Tsui, Y.-C. et al. Direct observation of a magnetic-field-induced Wigner crystal. Nature 628, 287–292 (2024).

Fogler, M. M., Koulakov, A. A. & Shklovskii, B. I. Ground state of a two-dimensional electron liquid in a weak magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1853–1871 (1996).

Tesanovic, Z., Axel, F. & Halperin, B. I. Hall crystal versus Wigner crystal. Phys. Rev. B 39, 8525–8551 (1989).

Halperin, B. I., Tesanovic, Z. & Axel, F. Compatibility of crystalline order and the quantized Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 922 (1986).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & Den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982).

Niu, Q., Thouless, D. J. & Wu, Y.-S. Quantized Hall conductance as a topological invariant. Phys. Rev. B 31, 3372–3377 (1985).

Kivelson, S., Kallin, C., Arovas, D. P. & Schrieffer, J. R. Cooperative ring exchange theory of the fractional quantized Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 873–876 (1986).

Koulakov, A. A., Fogler, M. M. & Shklovskii, B. I. Charge density wave in two-dimensional electron liquid in weak magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 499–502 (1996).

Moessner, R. & Chalker, J. T. Exact results for interacting electrons in high Landau levels. Phys. Rev. B 54, 5006–5015 (1996).

Rezayi, E. H., Haldane, F. D. M. & Yang, K. Charge-density-wave ordering in half-filled high Landau levels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 1219–1222 (1999).

Shayegan, M., Manoharan, H. C., Papadakis, S. J. & Poortere, E. P. D. Anisotropic transport of two-dimensional holes in high Landau levels. Phys. E 6, 40–42 (2000).

Cai, J. et al. Signatures of fractional quantum anomalous Hall states in twisted MoTe2. Nature 622, 63–68 (2023).

Park, H. et al. Observation of fractionally quantized anomalous Hall effect. Nature 622, 74–79 (2023).

Lu, Z. et al. Fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect in multilayer graphene. Nature 626, 759–764 (2024).

Sheng, D. N., Reddy, A. P., Abouelkomsan, A., Bergholtz, E. J. & Fu, L. Quantum anomalous hall crystal at fractional filling of Moir\’e superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 066601 (2024).

Dong, J. et al. Anomalous Hall Crystals in Rhombohedral Multilayer Graphene. I. Interaction-Driven Chern Bands and Fractional Quantum Hall States at Zero Magnetic Field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 206503 (2024).

Dong, Z., Patri, A. S. & Senthil, T. Theory of Quantum Anomalous Hall Phases in Pentalayer Rhombohedral Graphene Moiré Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 206502 (2024).

Zhou, B., Yang, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Fractional Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect in Rhombohedral Multilayer Graphene in the Moiréless Limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 206504 (2024).

Tan, T. & Devakul, T. Parent berry curvature and the ideal anomalous hall crystal. Phys. Rev. X, 14, 041040 (2024).

Shen, X. et al. Stabilizing fractional Chern insulators via exchange interaction in Moiré systems. arXiv: 2405.12294 (2024).

Song, X.-Y., Jian, C.-M., Fu, L. & Xu, C. Intertwined fractional quantum anomalous Hall states and charge density waves. Phys. Rev. B 109, 115116 (2024).

Su, R. et al. Moiré-driven topological electronic crystals in twisted graphene. Nature 637, 1084–1089 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Anisotropic band flattening in graphene with one-dimensional superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 525–530 (2021).

Drienovsky, M. et al. Commensurability oscillations in one-dimensional graphene superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026806 (2018).

Huber, R. et al. Band conductivity oscillations in a gate-tunable graphene superlattice. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–7 (2022).

Forsythe, C. et al. Band structure engineering of 2D materials using patterned dielectric superlattices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 566–571 (2018).

Matulis, A. & Peeters, F. M. Appearance of enhanced Weiss oscillations in graphene: theory. Phys. Rev. B 75, 125429 (2007).

Emery, V. J., Fradkin, E., Kivelson, S. A. & Lubensky, T. C. Quantum theory of the smectic metal state in stripe phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2160–2163 (2000).

Vishwanath, A. & Carpentier, D. Two-dimensional anisotropic non-Fermi-liquid phase of coupled Luttinger liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 676–679 (2001).

Mukhopadhyay, R., Kane, C. L. & Lubensky, T. C. Sliding Luttinger liquid phases. Phys. Rev. B 64, 045120 (2001).

Sondhi, S. L. & Yang, K. Sliding phases via magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 63, 054430 (2001).

Murthy, C. & Nayak, C. Almost perfect metals in one dimension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 136801 (2020).

Kane, C. L., Mukhopadhyay, R. & Lubensky, T. C. Fractional quantum Hall effect in an array of quantum wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 036401 (2002).

Teo, J. C. Y. & Kane, C. L. From Luttinger liquid to non-Abelian quantum Hall states. Phys. Rev. B 89, 085101 (2014).

Shavit, G. & Oreg, Y. Quantum geometry and stabilization of fractional chern insulators far from the ideal limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 156504 (2024).

Tan, T., May-Mann, J. & Devakul, T. Variational Wave-Function Analysis of the Fractional Anomalous Hall Crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 036604 (2025).

Lu, H., Wu, H.-Q., Chen, B.-B., Sun, K. & Meng, Z. Y. From fractional quantum anomalous Hall smectics to polar smectic metals: nontrivial interplay between electronic liquid crystal order and topological order in correlated topological flat bands. Rep. Prog. Phys. 87, 108003 (2024).

Murthy, G. Hall crystal states at ν = 2 and moderate Landau level mixing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1954–1957 (2000).

Levy, N. et al. Strain-induced pseudo–magnetic fields greater than 300 Tesla in graphene nanobubbles. Science 329, 544–547 (2010).

Tang, E. & Fu, L. Strain-induced partially flat band, helical snake states and interface superconductivity in topological crystalline insulators. Nat. Phys. 10, 964–969 (2014).

Venderbos, J. W. F. & Fu, L. Interacting Dirac fermions under a spatially alternating pseudomagnetic field: realization of spontaneous quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 93, 195126 (2016).

Möller, G. & Cooper, N. R. Fractional Chern insulators in Harper-Hofstadter bands with higher Chern number. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 126401 (2015).

Barkeshli, M. & Qi, X.-L. Topological nematic states and non-Abelian lattice dislocations. Phys. Rev. X 2, 031013 (2012).

Barkeshli, M., Jian, C.-M. & Qi, X.-L. Twist defects and projective non-Abelian braiding statistics. Phys. Rev. B 87, 045130 (2013).

Papić, Z., Mong, R. S. K., Yazdani, A. & Zaletel, M. P. Imaging anyons with scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011037 (2018).

Dong, J., Ledwith, P. J., Khalaf, E., Lee, J. Y. & Vishwanath, A. Many-body ground states from decomposition of ideal higher Chern bands: Applications to chirally twisted graphene multilayers. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023166 (2023).

Niu, S., Alicea, J., Sheng, D. N. & Peng, Y. Quantum anomalous Hall effects and Hall crystals at fractional filling of helical trilayer graphene. arXiv: 2505.24146 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Pak Kau Lim, Valentin Crepel, and especially Bert Halperin for helpful discussions. NP acknowledges the KITP, where this work was initiated. This research was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) under award FA9550-22-1-0432. This research was supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Simons Foundation, and grant no. NSF PHY-2309135 to the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP). GS acknowledges support from the Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics at Caltech, and from the Yad Hanadiv Foundation through the Rothschild fellowship. LF was supported in part by a Simons Investigator Award from the Simons Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.P., G.S. and L.F. conceived the idea, conducted the analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paul, N., Shavit, G. & Fu, L. Designing Hall crystals with variable Chern numbers. Nat Commun 16, 8103 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63320-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63320-6