Abstract

Reactive nitrogen plays critical roles in atmospheric chemistry, climate, and geochemical cycles, yet its sources in the marine atmosphere, particularly the cause of the puzzling daytime peaks of nitrous acid (HONO), remain unexplained. Here we reveal that iodide enhances HONO production during aqueous nitrate photolysis by over tenfold under typical marine conditions. Laboratory experiments and molecular simulations confirm that HONO formation from nitrate photolysis is a surface-dependent process, and the extreme surface propensity of iodide facilitates nitrate enrichment at interfaces, reducing the solvent cage effect and promoting HONO release. Global model simulations show that this process accelerates atmospheric nitrogen cycling, increasing the levels of nitrogen oxides, hydroxyl radicals, and ozone by over 25%, 30%, and 15%, respectively, and enhancing dimethyl sulfide and methane degradation by over 20% in the marine boundary layers. Our findings highlight the crucial role of iodide in interfacial photochemistry and marine atmospheric nitrogen cycling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen oxides (NOx = NO2 + NO) play a crucial role in the photochemical production of oxidants such as ozone (O3) and HOx (HOx = OH + HO2) radicals in the troposphere1. Even marginal fluctuations in NOx concentrations at parts per trillion (pptv) levels in marine and polar regions can significantly impact OH levels and O3 formation2,3. The changes in oxidants have the potential to affect atmospheric burdens in aerosols and greenhouse gases, thereby affecting global radiative forcing2,4. Recent research has demonstrated that the photolysis of particulate nitrate (NO3–, previously considered a permanent sink of atmospheric reactive nitrogen) is a significant source of NOx with nitrous acid (HONO) as an intermediate3,5,6,7, indicating a new and rapid nitrogen cycling process in the marine boundary layer3,7. HONO is a crucial precursor of OH radicals, with the heterogeneous conversion of NO2, vehicle exhaust, biomass burning, soil emissions, and livestock farming regarded as the significant sources in diverse environments8,9,10,11,12,13. However, these pathways fail to resolve two long-standing issues: the missing source of HONO that accounts for its midday concentration peak7,13,14,15 and the unexpectedly high HONO/NOx ratio observed in marine atmospheres6,7,15. The nitrate-derived HONO production pathway offers a plausible explanation for both of these phenomena. However, field studies and laboratory experiments have reported nitrate photolysis rates that differ by several orders of magnitude7,16,17,18, and the underlying mechanism for the large nitrate photolysis rates inferred from the field observations in the marine atmosphere has not been identified7,16.

Halides, including chloride, bromide, and iodide, are abundantly present in global marine aerosols19,20. Earlier studies have highlighted that halides, especially iodide, possess a remarkable propensity for surface interactions owing to their high polarizability, which, through interactions with the asymmetrically solvated water molecules, attains a more energetically stable state at the interface21,22. Consequently, halides can considerably influence the interfacial distribution of other ions and modulate heterogeneous reactions23. Previous laboratory experiments have confirmed that bromide, due to its surface affinity, can promote the photolysis of nitrate to produce NO2, albeit without concurrently detecting HONO23. Considering iodide’s higher polarizability and surface-enhancing properties, despite its generally lower concentrations, it may possess a high potential to enhance nitrate photolysis. However, the impact of iodide on nitrate photolysis, HONO production, and reactive nitrogen cycling has remained unexplored.

In the present study, through laboratory experiments, we provide compelling evidence for the substantial impact of iodide on promoting the photolysis of nitrate and the production of HONO. At atmospherically relevant concentrations, iodide enhances nitrate photolysis by over an order of magnitude compared to pure nitrate, primarily due to its remarkable surface affinity, which facilitates the transport of nitrate to the interfacial region. Incorporating this newly identified mechanism into a global model, the Community Atmosphere Model with Chemistry (CAM-Chem), substantially increases HONO production, the levels of NO2, O3, and OH, and the degradation of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and methane (CH4) in coastal and marine atmospheres. This proposed mechanism is of significance for future studies on the surface distribution of aerosol ions, the assessment of reactive nitrogen cycling, and greenhouse gas lifetimes in the marine atmosphere.

Results and discussion

Enhanced HONO production from nitrate photolysis by iodide

A series of experiments was conducted in a dynamic chamber to investigate the photolysis of solutions containing nitrate and halides under xenon lamp irradiation (Table S1). The gaseous products, i.e., HONO and NO2, were quantified using a Time-of-Flight Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ToF-CIMS) and a chemiluminescence/photolytic converter NOx analyzer, respectively (refer to the Methods section for detailed experimental procedures).

In the photolysis of a pure nitrate solution (exp. 1), the primary products were HONO and NO2, which supports previously proposed mechanisms of nitrate photolysis (R1–R3)18. The ratio of HONO to NO2 (1.2 ± 0.2) was consistent with the findings of Scharko et al. (2014), indicating comparable yields of nitrite and NO2 during pure nitrate photolysis24. We then conducted experiments with the addition of atmospherically relevant concentrations of chloride, bromide, and iodide at 1.0 M, 1.5 × 10–3 M, and 3.6 × 10–4 M, respectively (Fig. S1). The introduction of chloride (1.0 M) had a minimal effect on the production of HONO and NO2, which is in line with earlier studies suggesting chloride has little effect on the surface partitioning of nitrate25. In contrast, the presence of bromide and iodide increased the production of HONO and NO2, with a particularly pronounced effect on HONO formation. Specifically, bromide (1.5 × 10–3 M) increased HONO concentration by a factor of 5.7 and NO2 concentration by a factor of 1.5, while iodide (3.6 × 10–4 M) resulted in an 8.5-fold increase in HONO and a 2.3-fold increase in NO2 concentrations. The greater enhancement of HONO relative to NO2 could be attributed to the lower solubility of NO2, which facilitates its release from the aqueous solution during pure nitrate photolysis26. Consequently, the HONO/NO2 production ratio increased from 1.2 ± 0.2 under the pure nitrate condition to 4.3 ± 0.3 and 4.5 ± 0.3 in the presence of bromide and iodide, respectively. Previous studies have noted the promotion of NO2 production by bromide in nitrate photolysis, but HONO was not measured therein23. For the first time, we provide clear evidence that halides, specifically bromide and iodide, can significantly enhance HONO production during nitrate photolysis.

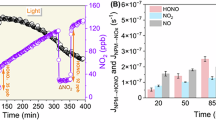

In marine aerosols, chloride, bromide, and iodide commonly coexist. Simulating experimental conditions that reflect their coexistence is essential to elucidate their collective role in the ambient atmosphere. Our experiments demonstrate that when chloride or bromide coexist with iodide, iodide plays a dominant role in enhancing HONO production during nitrate photolysis (Fig. 1a). At an iodide concentration of 1.8 × 10–4 M (exp. 3–6), the addition of 1.0 M chloride (exp. 4), 1.5 × 10–3 M bromide (exp. 5), or 3.0 × 10–3 M bromide (exp. 6) resulted in minimal changes in HONO concentrations (less than 15%). However, doubling the iodide concentration to 3.6 × 10–4 M, both in the absence (exp. 2) and presence (exp. 7) of bromide (3.0 × 10–3 M), led to a substantial increase in HONO concentrations by over 90%, highlighting iodide’s dominant impact under coexistence conditions. Notably, even at significantly lower iodide concentration of 1.8 × 10–6 M, iodide can surpass bromide in influencing HONO production (Fig. 1b). Only when iodide is nearly depleted in the solution, as indicated by the decline of molecular iodine (I2) after 150 min, does bromide exert a noticeable role, triggering a rise in both HONO and molecular bromine (Br2) formation. These findings reveal the crucial role of iodide in HONO production, which has been overlooked in previous studies that focused on the more abundant chloride and bromide18. In summary, when multiple halides coexist, as is typical in marine aerosols, iodide emerges as the primary driver of enhanced HONO production during nitrate photolysis.

a observed HONO concentrations during the experiments: (1) nitrate (1.0 M); (2) nitrate (1.0 M) + iodide (3.6 × 10–4 M); (3) nitrate (1.0 M) + iodide (1.8 × 10–4 M); (4) nitrate (1.0 M) + iodide (1.8 × 10–4 M) + chloride (1.0 M); (5) nitrate (1.0 M) + iodide (1.8 × 10–4 M) + bromide (1.5 × 10–3 M); (6) nitrate (1.0 M) + iodide (1.8 × 10–4 M) + bromide (3.0 × 10–3 M); (7) nitrate (1.0 M) + iodide (3.6 × 10–4 M) + bromide (3.0 × 10–3 M). The error bars represent the standard deviation of all conducted experiments. b HONO production when low concentrations of iodide (1.8 × 10–6 M) coexist with bromide (1.5 × 10–3 M). Initially, only molecular iodine (I2) is present (activated from iodide), with no molecular bromine (Br2), indicating that iodide is involved in nitrate photolysis. Due to the much lower concentration of iodide, the amount of HONO produced is relatively small. Once iodide is nearly depleted (with I2 rapidly declining), bromide can then participate, producing Br2, resulting in a corresponding increase in HONO production owing to the higher bromide concentration (three orders of magnitude greater than iodide). Overall, iodide dominates the production of HONO, while chloride and bromide have a relatively minor effect on HONO production in the presence of iodide.

Mechanism and parameterization

Previously proposed mechanisms for enhanced HONO production during nitrate photolysis in the presence of other substances include: (a) facilitating the conversion of NO2 to HONO by providing hydrogen donors27 or serving as photosensitizers28; and (b) inhibiting the oxidation of nitrite by aqueous OH29,30. However, these mechanisms are inconsistent with our experimental findings. If mechanism (a) were dominant, the observed NO2 concentration should decrease when adding halides, yet our results show increased NO2 levels (Fig. S1). Similarly, if mechanism (b) were valid, experiments with high concentrations of chloride should exhibit a more pronounced effect, as the aqueous reaction rates of OH with chloride and iodide are of the same order of magnitude (1.1 × 1010 M–1 s–1 vs. 0.4 × 1010 M–1 s–1), while the concentrations of added chloride exceed iodide by several orders of magnitude (1.0 M vs. 10–4 M). Therefore, both potential pathways can be ruled out here.

To elucidate the underlying mechanism, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to investigate the influence of individual halides and their coexistence on nitrate ion distribution in the mixed aqueous solutions of NaBr/NaNO3, NaI/NaNO3, and NaBr/NaI/NaNO3 (see Methods for simulation details). In the absence of halides, nitrate ions are uniformly distributed in the bulk phase of NaNO3 solutions (Fig. 2a, e). In contrast, bromide induces a pronounced surface preference for nitrate ions in the NaBr/NaNO3 solutions (Fig. 2b, f), a phenomenon consistent with the previously reported simulations23. Iodide further enhances this effect in NaI/NaNO3 solution (Fig. 2c, g): the interfacial relative enrichment factor of nitrate ions (see Methods for the definition) increases to 3.0 compared to 1.7 with bromide, reflecting a stronger propensity to drive nitrate ions to the interface. This agrees well with our experimental results, which indicate that iodide promotes HONO production from nitrate photolysis more effectively than bromide. In coexistence solutions (NaBr/NaI/NaNO3, Fig. 2d, h), iodide exhibits stronger surface preference (with a more prominent peak located at the outer layer of the surface compared to the iodide peak in Fig. 2g) than bromide (with a much lower surface peak than the bromide peak in Fig. 2f and a more obvious peak located in the bulk phase). These results support the experimental findings that the interfacial distribution of nitrate ions is predominantly influenced by iodide, while the effect of bromide is suppressed under coexistence conditions. The MD simulations reveal that halides, particularly iodide, lead to the formation of a double ion layer (interfacial halides and subsurface counterions) due to their strong polarity21. Halides attract sodium ions closer to the interface, thereby facilitating the transport of nitrate ions to there. The reduced solvent cage effect at the interface inhibits nitrite recombination with ground-state oxygen atoms, O(3P), and subsequent nitrate regeneration. As a result, this process ultimately increases the photochemical production of HONO and NO2. The proposed mechanism herein is further supported by experiments demonstrating a correlation between HONO production and solution surface area. Doubling the surface area, by dividing a single 25 mL solution into two 12.5 mL solutions, nearly doubled the initial HONO production, with a subsequent reduction to approximately 1.8 times as nitrite accumulated in the bulk phase (Fig. 3a). This result indicates that surface reactions govern the HONO production during nitrate photolysis.

The water Gibbs dividing surface (GDS) is located at the dotted line with Z = 0 Å, and the solution center of mass (COM) is set to Z = –15 Å. The probability density (ρ) for each ion shifts along the Z-direction from the COM to the GDS, and the area under the curve equals 0.5. The colors of the curves in right panels e-h correspond to the atom coloring in left panels a–d. a, e surface snapshot and ion density profile for aqueous solutions of NaNO3. The numbers of sodium and nitrate ions are 72 and 72, respectively. Nitrate ions prefer to distribute in the bulk solution and are repelled from the surface. b, f surface snapshot and ion density profile for mixed aqueous solutions of NaBr/NaNO3. The numbers of sodium, bromide, and nitrate ions are 72, 54, and 18, respectively. Nitrate density is enhanced toward the surface through a double ion layer formed by adsorbed bromide and sodium ions. c, g surface snapshot and ion density profile for mixed aqueous solutions of NaI/NaNO3. The numbers of sodium, iodide, and nitrate ions are 72, 54, and 18, respectively. Nitrate ions are drawn much closer to the interface compared to the case assisted by bromide. d, h surface snapshot and ion density profile for mixed aqueous solutions of NaBr/NaI/NaNO3. The numbers of sodium, bromide, iodide, and nitrate ions are 72, 27, 27, and 18, respectively. The interfacial propensity of iodide is significantly enhanced, and the bromides are predominantly pushed into the bulk with a suppressed peak in the surface.

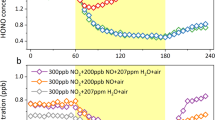

a surface area dependence: Experiments with 25 mL in a single dish and 12.5 mL in two dishes. b iodide concentration dependence: Nitrate and chloride concentrations are both 1 M, bromide is 1.5 × 10–3 M, and pH = 2. c pH dependence: Nitrate and chloride are both 1 M, bromide is 1.5 × 10–3 M, iodide is 1.8 × 10–4 M. d nitrate concentration dependence: Chloride, bromide, and iodide are 1 M, 1.5 × 10–3 M, and 1.8 × 10–4 M, respectively, and pH = 2. Note: The gray data points in c and d represent experiments using pure nitrate solutions without added halides. e parameterization scheme. [I–] and [NO3–] represent the concentrations of iodide and nitrate (mol L–1), respectively; Sa represents the aerosol surface area (μm2 cm–3); JHNO3 represents the photolysis rate of gaseous nitric acid (s–1); pH represents the aerosol acidity. The coefficient k is an exponential pre-factor derived through least squares linear fitting, with no specific physical meaning. The surface area density of the chamber was calculated as the physical surface area of the solution in the petri dish divided by the chamber volume. Error bars represent the standard deviation of all conducted experiments.

We conducted additional experiments to quantify the impacts of iodide concentration, pH, and nitrate concentration on the HONO production during nitrate photolysis. To better simulate the actual atmospheric conditions, all experiments were conducted with chloride and bromide at atmospherically relevant concentrations and ratios, specifically a constant chloride concentration of 1.0 M and a bromide concentration of 1.5 × 10–3 M. Across an iodide concentration range of 1.5 × 10–5 M to 7.2 × 10–4 M, HONO production exhibited near-linear enhancement (Fig. 3b), with the iodide concentration at 7.2 × 10–4 M increasing HONO production by more than an order of magnitude, reaching 12.3 times that of the pure nitrate condition. Iodide is commonly found in global marine aerosols (10–5 – 10–3 M), and in certain coastal regions, its aerosol concentration is expected to reach up to 10–2 M (Table S2 and Fig. S2)31. Therefore, iodide is expected to significantly promote nitrate photolysis and HONO production in marine and coastal atmospheres. Additionally, the formation of HONO is greatly influenced by pH, notably increasing under acidic conditions. The promoting effect of iodide rises from 2.0 times at pH 3.3 to 5.6 times at pH 1.5 (Fig. 3c). The impact of nitrate concentration reveals a shadowing effect in both pure nitrate and iodide-containing solutions. As the nitrate concentration increases to 2 M, the curve for HONO production gradually levels off (Fig. 3d). This suggests that not all bulk nitrate contributes to HONO formation; rather, the surface nitrate is more critical. Once the surface nitrate concentration becomes saturated, further increases in bulk nitrate no longer enhance HONO production. This also explains the lower apparent nitrate photolysis rates observed in polluted areas16. Nonetheless, this effect is primarily evident in urban regions with elevated nitrate levels. In marine atmospheres, the production of HONO may still rise approximately linearly with increasing nitrate concentration due to the relatively low concentrations of nitrate aerosols.

Based on these findings, we propose a parameterization for ambient HONO production rate (PHONO), as a function of [NO3−], [I−], pH, and aerosol surface areas (Sa):

Here, the coefficient k represents an empirical pre-factor (1.9 × 106) derived from least-squares fitting of laboratory data, with no specific physical meaning (Fig. 3e). [NO3−] and [I−] represent aqueous concentrations of nitrate and iodide in aerosols, Sa is the aerosol surface area, JHNO3 is the photolysis rate of gaseous nitric acid, and pH is the aerosol acidity (refer to Fig. 3 and the model simulation section for details). In the following section, we integrated this scheme into a chemistry-climate model to quantify the role of iodide-enhanced nitrate photolysis and HONO production (hereafter referred to as the I-HONO process) in global atmospheric chemistry.

Global impacts of iodide-enhanced HONO production

Extensive ship-based and fixed-site observations have confirmed the widespread presence of iodide19,31 and nitrate aerosols7,32 in the marine atmosphere, suggesting a potentially important role of iodide-enhanced nitrate photolysis and HONO production in global atmospheric chemistry. Here, we incorporated the experimentally derived parameterization scheme into CAM-Chem, a global model with up-to-date reactive halogen sources and chemistry33, to evaluate the global significance of this mechanism. Details of the model description, parameterization option, simulation design, and performance evaluation are provided in the Methods section.

Figure 4 illustrates the simulated absolute and relative changes of HONO, NO2, O3, and OH concentrations in the boundary layer after considering the I-HONO process (the base case results are shown in Fig. S3). The simulated average concentrations of these species across various spatial scales are summarized in Table S3. Our simulations indicate that the I-HONO process leads to noticeable increases in HONO levels (170.0% or 2.7 pptv for the global average, up to 219.6 pptv) and NOx (15.2% or 13.7 pptv for the global average, up to 597.0 pptv) in the global marine atmosphere. Along the coasts of eastern and southern Asia, as well as in Europe and northern America, the concurrent presence of high concentrations of iodide and nitrate aerosols results in relative increases of over 500% for HONO and about 25% for NOx, respectively. At ten coastal/marine sites with available HONO observations, the I-HONO process significantly increases the simulated HONO concentrations, with an average twofold enhancement across the sites (ranging from 22% to over 300%), thereby bringing the simulation results closer to the observations compared to the base case without the I-HONO process (Fig. S4a). The newly proposed process also increases the HONO/NOx ratios at all sites; the simulated HONO/NOx ratio increased from 0.007–0.026 in the base case to 0.013–0.081 in the I-HONO case. The increase at each site ranges from 19% to 238%, with most sites experiencing an increase exceeding 100% (Fig. S4b). This may offer a plausible explanation for the previously observed inexplicably high HONO/NOx ratios in the ambient atmosphere5,6. Moreover, this result suggests that HONO could act as a precursor to NOx production in the marine atmosphere, in contrast to polluted areas where NOx serves as a precursor to HONO formation. This could fundamentally change our understanding of reactive nitrogen cycling and atmospheric oxidation processes in the marine atmosphere.

The accelerated cycling of HONO and NOx from nitrate photolysis results in a larger production of oxidants, particularly O3 and OH, e.g., up to 10.1 at parts per billion (ppbv) or 32.3% increase (1.1 ppbv or 5.6% for global average) in O3 concentration and 2.0 × 106 molecules cm–3 or 73.5% increase (2.0 × 105 molecules cm–3 or 16.0% for global average) in OH concentration (Fig. 4 and Table S3). Along the coastal regions of southern Asia, the I-HONO process results in average changes in O3 and OH levels exceeding 15% and 30%, respectively. The impacts of the I-HONO process on atmospheric oxidant levels have important implications for the oxidation of many air quality and climate-relevant species. Here, we quantify the oxidation rate of DMS (the predominant precursor of sulfate aerosol over the ocean; Fig. S5) and CH4 (the most important reactive greenhouse gas; Fig. S6). Similar to the spatial distribution of I-HONO impacts on OH radicals, the I-HONO process induced large increases in DMS and CH4 loss rates in the global marine boundary layer, with relative changes exceeding 20% in some marine boundary layers. In the present study, we have demonstrated that iodide, ubiquitously existing in the surface air, particularly in marine atmospheres, significantly amplifies the nitrate photolysis rate and induces large changes in atmospheric chemistry and oxidation capacity. It is noteworthy that there exist some uncertainties regarding the global impacts of iodide-induced nitrate photolysis and HONO production processes. We have summarized these uncertainties in Supplementary Text S2.

Atmospheric implications

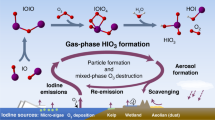

Iodide, functioning as an inorganic antioxidant, accumulates in marine algae and is subsequently released during oxidative stress or senescence34,35. It is abundant in the global marine surface microlayer36. Ocean iodide is emitted into the atmosphere as I2 and hypoiodous acid (HOI) following surface O3 oxidation37,38. These iodine species undergo subsequent atmospheric reactions that drive new particle formation and O3 depletion39,40,41,42. Ultimately, they partition into aerosols, primarily in the form of iodide and iodate43. In this study, we find that the extreme surface propensity of iodide facilitates the transport of nitrate to the surface, effectively promoting HONO production from nitrate photolysis and accelerating reactive nitrogen cycling in the marine atmosphere. This process increases marine atmospheric oxidation capacity, which promotes the oxidation of CH4, DMS, and other reactive trace gases. Enhanced CH4 oxidation and secondary aerosol formation may contribute to a global cooling effect, while increased O3 and secondary aerosol pose adverse impacts on regional air quality, ecosystems, and human health in coastal regions. We provide a brief illustration of the role of iodine in nitrogen cycling in Fig. 5.

Iodide is abundant in the marine surface microlayer and can be generated through biological processes. Ocean iodide is released into the atmosphere following surface ozone oxidation as I2 and HOI. These species undergo subsequent atmospheric reactions and eventually become incorporated into aerosols. Iodide exhibits a strong surface affinity and can form a double layer of interfacial halide and subsurface counterions. This characteristic facilitates the transportation of additional nitrate to the surface, effectively promoting reactive nitrogen cycling via nitrate photolysis in the marine atmosphere. It is important to note that the ion distribution depicted in the diagram is exaggerated for clarity and does not represent the actual absolute quantity distribution. DMS dimethyl sulfide.

The biogeochemical cycle of iodine intricately connects marine organisms with the marine atmosphere. Studies of ice cores from Greenland and the Alpine region have revealed a threefold increase in iodine content since the 1950s44,45. Future iodine emissions may continue increasing due to rising O3 levels and the expansion and intensification of algal blooms46,47,48. Meanwhile, with the successful control of global SO2 emissions, nitrate aerosols have become increasingly important in the atmosphere49. These trends suggest that iodide-enhanced nitrate photolysis, as elucidated in this study, will become more important under the anticipated global warming and play a more crucial role in the marine atmospheric nitrogen cycling. Moreover, previous studies have shown that photochemical processes at air-water interfaces exhibit distinct kinetics and mechanisms compared to bulk-phase reactions50,51. The strong surface preference of iodide likely influences the interfacial distribution of multiple marine aerosol components beyond nitrate, thereby affecting multiphase chemistry of marine aerosols: e.g., enhancing halogen activation and modifying cloud condensation nuclei activity through altered surface hygroscopicity. Our findings reshape the understanding of reactive nitrogen cycling in the marine atmosphere and highlight the crucial yet previously overlooked role of ion-specific surface effects in atmospheric multiphase chemistry. These insights are expected to stimulate new research directions in marine aerosol chemistry, particularly in climate-relevant processes involving interfacial halogen chemistry and aerosol-cloud interactions.

Methods

Laboratory Experiments

All experiments were conducted in a custom-built dynamic chamber. The chamber is constructed from Teflon and has a volume of 1.875 L, with dimensions of 25 cm in length, 15 cm in width, and 5 cm in height. It is equipped with a TFE Teflon-film window on the top for optical access. A Teflon petri dish, 60 mm in diameter and 7 mm in height, was utilized to contain a 20 mL liquid solution during the experiments, which was exposed to light. The reaction products were carried by zero air at a flow rate of 4 L min–1 and analyzed in real-time using iodine-Time-of-Flight Chemical Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ToF-CIMS, Aerodyne Research Inc., USA) for HONO measurement (detected as IHONO–, with a mass-to-charge ratio of 173.9)52, as well as a chemiluminescence/photolytic converter NOx analyzer (Model 42i-TL, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) for NOx measurement. Detailed calibration procedures for the ToF-CIMS are provided in the supplementary materials. The experimental humidity was maintained at 70%, and the residence time of zero air in the chamber was 28 seconds. All experiments were conducted at room temperature (296 K). A high-pressure xenon lamp with a power output of 300 W was employed as the light source to simulate the solar radiation spectrum, with its spectral irradiance characteristics shown in Fig. S7, ranging from 320 nm to 1100 nm and peaking at 450 nm.

The experiments aimed to explore the impacts of iodide concentrations (ranging from 1.8 × 10–6 to 7.2 × 10–4 M), nitrate concentrations (ranging from 0.1 to 2.0 M), and pH (ranging from 1.5 to 4.4) in the presence of halides and nitrate. In addition, control experiments with pure nitrate were conducted under the same conditions. Reagents utilized in the experiments included sodium nitrate (NaNO3) (≥99.0%, Fluka), sodium chloride (NaCl) (≥99.999%, Aladdin), sodium bromide (NaBr) (≥99.99%, Aladdin), and potassium iodide (KI) (≥99.0%, Aladdin). The pH of the solutions was adjusted using a sulfuric acid solution derived from concentrated sulfuric acid (95–97%, Sigma-Aldrich) and monitored with a digital pH meter (HANNA instrument, HI253). To ensure minimal changes in the solution properties, experiments were typically limited to 30–60 min (resulting in <8% change in initial volume). For the iodide/bromide coexistence system (Fig. 1b), experiments were extended to 150 min to ensure complete iodide consumption, with results used solely for qualitative analysis. Analysis of the experimental data revealed that the production of HONO and NO2 stabilized within this period for almost all experimental conditions. The equilibrium concentrations of the measured species for subsequent analysis were determined based on the average results from the final 5 min of each experiment.

To closely mimic actual atmospheric conditions, the experiments adopted the following base scenario: a pH of 2, nitrate concentration of 1 M, chloride concentration of 1 M, bromide concentration of 1.5 × 10–3 M, and iodide concentration of 1.8 × 10–4 M. These choices were made for the following reasons: (1) pH value: Previous research indicates that marine aerosols, despite being initially alkaline, quickly acidify (within minutes) after release53. Field studies commonly observe actual marine aerosols with a pH below 2, a condition also simulated in models54. (2) Nitrate and chloride concentrations: The selected concentrations for these ions align with observations of ambient aerosols and are consistent with those used in prior studies55,56. (3) Bromide concentration: The chosen bromide concentration mirrors the ratio to chloride found in seawater (1/650 of the chloride concentration). (4) Iodide concentration: The iodide concentration was set at 100 times its ratio to chloride (1/550,000) in bulk seawater in the base scenario. Numerous studies have highlighted the significant enrichment of iodide in aerosols compared to seawater57. Our analysis of existing aerosol iodide measurements (Table S2) revealed its common presence in global marine aerosols. Based on assumed aerosol water content, the estimated aqueous iodide concentrations ranged from 10–5 M to 10–2 M, with higher levels observed in coastal regions. The concentration range utilized in our laboratory experiments broadly encompasses these observed conditions (Fig. S2).

In the ambient atmosphere, aerosols contain a diverse array of organic compounds58. Laboratory studies have shown that these organics can influence HONO formation during nitrate photolysis28,29,59. To evaluate whether such compounds modulate the role of iodide, we conducted experiments using representative organic compounds commonly found in marine aerosols or employed in marine aerosol simulations, including ethylene glycol, dimethyl phthalate, sodium dodecyl sulfate, glucose, and oxalic acid. Our findings indicate that the presence of these organic compounds does not significantly alter our results; detailed experimental outcomes are provided in the supplementary materials. It is important to note that our experiments were conducted in aqueous solutions, a common reaction medium in laboratory studies. However, the reaction rates and influencing factors may differ under ambient aerosol conditions. Future studies are recommended to further investigate iodide-induced nitrate photolysis and its atmospheric implications in more realistic aerosol environments.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed to investigate the distribution of nitrate ions in aqueous solutions of NaNO3 and in mixed solutions of NaBr/NaNO3, NaI/NaNO3, and NaBr/NaI/NaNO3. The specific compositions of these systems are detailed in Table S4. All simulations were performed using the OpenMM software package60. The AMOEBA (atomic multipole optimized energetics for biomolecular applications) polarizable force field, which explicitly accounts for the polarization effect with polarizable atomic multipoles through the quadrupole moments61, was used in this study. Specifically, the AMOEBA/GEM-DM flexible water model62 was incorporated to simulate the water solution, and the AMOEBA-IL polarizable force field parameters63 were utilized for all the ions involved in this study. All parameters can be accessed at the force field parameter sets of Tinker (https://dasher.wustl.edu/tinker/distribution/params/), and detailed descriptions of the force field parameters are provided in Tables S5–S7.

The aqueous solutions were built using Packmol software64. All simulations were first run in a 500 ps anisotropic NPT ensembles to equilibrate the system and avoid divergent energies due to induced dipoles, with dimension scaling in the z direction and fixed 30 Å in the x and y directions. Next, the simulation box was set in the center of a rectangular box with dimensions of 30 Å × 30 Å × 150 Å, followed by 50 ns NVT simulations to collect production data. The simulation temperature was maintained at 303.15 K by implementing an Andersen thermostat with a coupling time of 1 ps65. The leap-frog Verlet algorithm66 with a time-step of 1 fs was performed to integrate Newton’s equations of motion. The trajectory data were recorded every 10 ps. The PME method67 was employed to treat the electrostatic multipole interactions with a real-space cutoff distance of 8 Å and an Ewald error tolerance of 5 × 10−4. The cutoff distance for the van der Waals interactions combined with a long-range dispersion correction68 was set to 12 Å. The induced dipoles were converged to a target epsilon of 10−5 using the self-consistency iteration method. No constraints were enforced on covalent bonds or water molecule geometries. To qualitatively analysis the nitrate ion distribution in these mixed aqueous solutions, we introduced a concept of interfacial relative enrichment factor of nitrate ions, defined as the ratio of the integration of probability density (ρ) under the curve of nitrate ion in each mixed aqueous solution relative to that in the pure NaNO3 solution in the interfacial range of 0 to –5 Å. The calculated interfacial relative enrichment factors of nitrate ions are 1.7 and 3.0 for the mixed aqueous solutions of NaBr/NaNO3 and NaI/NaNO3, respectively.

CAM-Chem model

This study utilized a global 3-D chemistry-climate model, the Community Atmospheric Model with Chemistry (CAM-Chem), integrated into the Community Earth System Model (CESM) framework. The model configuration employed a horizontal grid resolution of 0.9° (latitude) × 1.25° (longitude) and 56 hybrid vertical levels spanning from the surface to approximately 40 km. The emission inventory of the routine air pollutants, e.g., CO, SO2, NOx, VOCs, NH3, PM2.5, BC, OC, etc., in 2018–2019 is obtained from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) emissions69.

This version of the CAM-Chem model has been used extensively to simulate halogen species and their impacts on other atmospheric compositions, and we have validated many aspects of the model performance, e.g., gaseous halogen species mixing ratio, tropospheric O3 burden, tropospheric OH burden, etc., which showed that this model setup can capture the general characteristics of tropospheric chemistry (Saiz-Lopez et al., 2023 and the references therein)33.

Nitrate aerosol simulation in CAM-Chem

In this version of the CAM-Chem model, nitrate aerosol is represented as ammonium nitrate in thermodynamic equilibrium with ammonia gas and nitric acid; while ammonia gas is a primary pollutant emitted directly from sources like agricultural activities, nitric acid is a secondary product formed from several atmospheric reactions, mainly including the reaction of NO2 and OH (the dominant daytime source of total nitrate) and the heterogeneous reactions of N2O5 (the dominant nighttime source of total nitrate)70. Such treatment of nitrate aerosol works fine over the land where ammonia is sufficient; however, over the ocean particularly remote ocean where there is no ammonia emission, the simulated nitrate aerosol is at a very low level, which is in contrast to the observations, while the sum of nitrate aerosol and nitrate acid gas is very close to the observed nitrate aerosol (Fig. S8 and Fig. S9). Therefore, in our calculation of the nitrate photolysis rate, we use the sum of both nitrate aerosol and nitrate gas over the ocean, while maintaining only nitrate aerosol over the land.

Iodide aerosol simulation in CAM-Chem

Our CAM-Chem model simulations are based on the latest reactive halogen (including iodine) sources and chemistry, and the detailed description and validation can be found in Saiz-Lopez et al. (2023)33. Briefly, the model incorporated an organic and inorganic halogen (chlorine, bromine, and iodine) photochemistry mechanism, accounting for natural and anthropogenic sources, heterogeneous activation and cycling, and dry and wet deposition in both the troposphere and lower stratosphere. Oceanic emissions of CH2I2, CH2ICl, and CH2IBr were determined based on parameterizations derived from chlorophyll-a satellite maps. HOI and I2 were emitted from the ocean surface following the deposition of surface O3. The concentration of iodide aerosol was simulated by considering the uptake of various gaseous iodine species (HI, HOI, INO3, I2O2, I2O3, and I2O4) on tropospheric aerosol surfaces. The specific uptake coefficients used in the model can be found in Table S8. Please note that in this study, we did not consider the speciation of iodine after uptake into aerosols. Previous research has suggested that iodide ion concentrations typically represent around 25%–90% of total inorganic iodine in aerosols57. Our simulations assumed that iodide ion concentration accounts for 40% of the total iodine in aerosols. The simulated aerosol iodide concentrations typically ranged from 1 to 5 ng m–3 in the surface layer over the ocean and also with noticeable levels over the land (>0.5 ng m–3) due to atmospheric transport (Fig. S10), aligning well with previous observational data (Fig. S11)31. The simulated nitrate aerosol concentration is elevated over the land (typically over 1 µg m–3), and with the continental outflow, the continental-originated nitrate aerosol is also transported to the oceanic regions (Fig. S8). As a result, the marine areas along the coastlines, particularly Eastern and Southern Asia marine areas, are the regions with the most active iodide-enhanced nitrate photolysis process.

HONO simulation in CAM-Chem

There are multiple sources of HONO in the atmosphere. In our model simulations, we consider homogeneous production of HONO through the reactions of OH with NO and heterogeneous reactions of NO2 on aerosol surfaces. We did not include the heterogeneous reactions at the ocean surface due to the alkaline conditions, which hinder the release of generated HONO into the atmosphere. For the HONO production from the photolysis of pure nitrate, we employed an EF (enhancement factor) of 30, a value deemed appropriate in prior research and utilized in previous models to more effectively simulate the impact of nitrate photolysis in polluted regions3,17,71,72. Detailed parameters can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S9).

We use our laboratory-derived parameterization for the HONO production from the iodide-enhanced nitrate photolysis. To provide a more conservative estimate, we apply region/altitude/condition limits (where this reaction is more likely to happen in the ambient atmosphere) to the iodide-enhanced nitrate photolysis reaction: (1) horizontally in the regions from 60°S to 60°N, (2) vertically only within the boundary layer, and (3) only when RH is higher than 60% to ensure the liquid state of aerosols. After incorporating the I-HONO process, the model shows a marked improvement in simulating HONO. At the selected 10 coastal/marine sites, the simulated HONO concentrations have increased by 22%–313%. The deviation of simulated HONO from observations has been significantly reduced (Fig. S4).

CAM-Chem simulation scenarios

In the present study, we simulated two main scenarios, including a scenario incorporating nitrate photolysis with an EF of 30 (Base case) and a scenario considering the parameterized scheme of the iodide-enhanced HONO production during nitrate photolysis (I-HONO case). Both CAM-Chem simulations were run for the year 2019, with an additional 12 months (Jan to Dec 2018) discarded as the spin-up period. The difference in atmospheric compositions between the Base and the I-HONO cases represents the impacts of iodide-enhanced HONO production on atmospheric chemistry. Since iodide remains the dominant driver of HONO production during nitrate photolysis, even at concentrations far below observed and modeled levels, in the presence of other halides, our model simulations focus solely on iodide-induced HONO formation. However, it should be noted that bromide could potentially play a role in environments severely depleted in iodide.

Data availability

Data generated in this study have been deposited in the Mendeley Data public repository (https://doi.org/10.17632/5cd46mhd6j.1)73.

Code availability

The software code for the CESM model is available from http://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/74.

Change history

12 September 2025

In this article the affiliation ‘Environment Research Institute, Shandong University, Qingdao, China’ for Alfonso Saiz-Lopez was incorrectly assigned as has now been removed. The original article has been corrected.

References

Seinfeld, J. H. & Pandis, S. N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: from Air Pollution to Climate Change (John Wiley & Sons, 2016).

Nie, W. et al. NO at low concentration can enhance the formation of highly oxygenated biogenic molecules in the atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 14, 3347 (2023).

Kasibhatla, P. et al. Global impact of nitrate photolysis in sea-salt aerosol on NOx, OH, and O3 in the marine boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 11185–11203 (2018).

Rigby, M. et al. Role of atmospheric oxidation in recent methane growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 5373–5377 (2017).

Ye, C. et al. Synthesizing evidence for the external cycling of NOx in high- to low-NOx atmospheres. Nat. Commun. 14, 7995 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Validating HONO as an intermediate tracer of the external cycling of reactive nitrogen in the background atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 5474–5484 (2023).

Ye, C. et al. Rapid cycling of reactive nitrogen in the marine boundary layer. Nature 532, 489–491 (2016).

Su, H. et al. Soil nitrite as a source of atmospheric HONO and OH radicals. Science 333, 1616–1618 (2011).

Gu, R. et al. Investigating the sources of atmospheric nitrous acid (HONO) in the megacity of Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 812, 152270 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Unveiling the underestimated direct emissions of nitrous acid (HONO). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 120, e2302048120 (2023).

Theys, N. et al. Global nitrous acid emissions and levels of regional oxidants enhanced by wildfires. Nat. Geosci. 13, 681–686 (2020).

Liao, S. et al. High gaseous nitrous acid (HONO) emissions from light-duty diesel vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 200–208 (2021).

Zhong, X. et al. Nitrous acid budgets in the coastal atmosphere: potential daytime marine sources. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 14761–14778 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. Dominant processes of HONO derived from multiple field observations in contrasting environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 9, 258–264 (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Strong marine-derived nitrous acid (HONO) production observed in the coastal atmosphere of northern China. Atmos. Environ. 244, 117948 (2021).

Andersen, S. T. et al. Extensive field evidence for the release of HONO from the photolysis of nitrate aerosols. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd6266 (2023).

Romer, P. S. et al. Constraints on aerosol nitrate photolysis as a potential source of HONO and NOx. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 13738–13746 (2018).

Gen, M., Liang, Z., Zhang, R., Go Mabato, B. R. & Chan, C. K. Particulate nitrate photolysis in the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2, 111–127 (2022).

Gómez Martín, J. C., Saiz-Lopez, A., Cuevas, C. A., Baker, A. R. & Fernández, R. P. On the speciation of iodine in marine aerosol. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD036081 (2022).

Simpson, W. R., Brown, S. S., Saiz-Lopez, A., Thornton, J. A. & Von Glasow, R. Tropospheric halogen chemistry: sources, cycling, and impacts. Chem. Rev. 115, 4035–4062 (2015).

Piatkowski, L., Zhang, Z., Backus, E. H. G., Bakker, H. J. & Bonn, M. Extreme surface propensity of halide ions in water. Nat. Commun. 5, 4083 (2014).

Gladich, I., Shepson, P. B., Carignano, M. A. & Szleifer, I. Halide affinity for the water−air interface in aqueous solutions of mixtures of sodium salts. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 5895–5899 (2011).

Richards, N. K. et al. Nitrate ion photolysis in thin water films in the presence of bromide ions. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 5810–5821 (2011).

Scharko, N. K., Berke, A. E. & Raff, J. D. Release of nitrous acid and nitrogen dioxide from nitrate photolysis in acidic aqueous solutions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 11991–12001 (2014).

Hong, A. C., Wren, S. N. & Donaldson, D. J. Enhanced surface partitioning of nitrate anion in aqueous bromide solutions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2994–2998 (2013).

Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4399–4981 (2015).

Ye, C., Zhang, N., Gao, H. & Zhou, X. Matrix effect on surface-catalyzed photolysis of nitric acid. Sci. Rep. 9, 4351 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Superoxide and nitrous acid production from nitrate photolysis is enhanced by dissolved aliphatic organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 8, 53–58 (2021).

Mora García, S. L., Gutierrez, I., Nguyen, J. V., Navea, J. G. & Grassian, V. H. Enhanced HONO formation from aqueous nitrate photochemistry in the presence of marine relevant organics: impact of marine-dissolved organic matter (m-DOM) concentration on HONO yields and potential synergistic effects of compounds within m-DOM. ACS EST Air 1, 525–535 (2024).

Benedict, K. B., McFall, A. S. & Anastasio, C. Quantum yield of nitrite from the photolysis of aqueous nitrate above 300 nm. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 4387–4395 (2017).

Sherwen, T. M. et al. Global modeling of tropospheric iodine aerosol. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10012–10019 (2016).

Lao, Q. et al. Hemispherical scale mechanisms of nitrate formation in global marine aerosols. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–8 (2024).

Saiz-Lopez, A. et al. Natural short-lived halogens exert an indirect cooling effect on climate. Nature 618, 967–973 (2023).

Küpper, F. C. et al. Iodide accumulation provides kelp with an inorganic antioxidant impacting atmospheric chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 6954–6958 (2008).

Hepach, H., Hughes, C., Hogg, K., Collings, S. & Chance, R. Senescence as the main driver of iodide release from a diverse range of marine phytoplankton. Biogeosciences 17, 2453–2471 (2020).

Chance, R., Baker, A. R., Carpenter, L. & Jickells, T. D. The distribution of iodide at the sea surface. Env. Sci. Process. Impacts 16, 1841–1859 (2014).

Carpenter, L. J. et al. Atmospheric iodine levels influenced by sea surface emissions of inorganic iodine. Nat. Geosci. 6, 108–111 (2013).

Prados-Roman, C. et al. Iodine oxide in the global marine boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 583–593 (2015).

Zhao, B. et al. Global variability in atmospheric new particle formation mechanisms. Nature 631, 98–105 (2024).

He, X.-C. et al. Iodine oxoacids enhance nucleation of sulfuric acid particles in the atmosphere. Science 382, 1308–1314 (2023).

Cuevas, C. A. et al. The influence of iodine on the Antarctic stratospheric ozone hole. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2110864119 (2022).

Benavent, N. et al. Substantial contribution of iodine to Arctic ozone destruction. Nat. Geosci. 15, 770–773 (2022).

Gómez Martín, J. C. et al. Spatial and temporal variability of iodine in aerosol. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD034410 (2021).

Cuevas, C. A. et al. Rapid increase in atmospheric iodine levels in the North Atlantic since the mid-20th century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1452 (2018).

Legrand, M. et al. Alpine ice evidence of a three-fold increase in atmospheric iodine deposition since 1950 in Europe due to increasing oceanic emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 12136–12141 (2018).

Dai, Y. et al. Coastal phytoplankton blooms expand and intensify in the 21st century. Nature 615, 280–284 (2023).

Carpenter, L. J. et al. Marine iodine emissions in a changing world. Proc. R. Soc. A. 477, 20200824 (2021).

Iglesias-Suarez, F. et al. Natural halogens buffer tropospheric ozone in a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 147–154 (2020).

Liu, Y. C. et al. Enhanced nitrate fraction: enabling urban aerosol particles to remain in a liquid state at reduced relative humidity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105505 (2023).

Rossignol, S. et al. Atmospheric photochemistry at a fatty acid–coated air-water interface. Science 353, 699–702 (2016).

Kusaka, R., Nihonyanagi, S. & Tahara, T. The photochemical reaction of phenol becomes ultrafast at the air–water interface. Nat. Chem. 13, 306–311 (2021).

Gu, R. et al. Nitrous acid in the polluted coastal atmosphere of the South China Sea: ship emissions, budgets, and impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 826, 153692 (2022).

Angle, K. J. et al. Acidity across the interface from the ocean surface to sea spray aerosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2018397118 (2021).

Pye, H. O. T. et al. The acidity of atmospheric particles and clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 4809–4888 (2020).

Peng, X. et al. Photodissociation of particulate nitrate as a source of daytime tropospheric Cl2. Nat. Commun. 13, 939 (2022).

Xia, M. et al. Pollution-derived Br2 boosts oxidation power of the coastal atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 12055–12065 (2022).

Droste, E. S., Baker, A. R., Yodle, C., Smith, A. & Ganzeveld, L. Soluble iodine speciation in marine aerosols across the Indian and Pacific Ocean basins. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 788105 (2021).

Fu, P. Q., Kawamura, K., Chen, J., Charrière, B. & Sempéré, R. Organic molecular composition of marine aerosols over the Arctic Ocean in summer: contributions of primary emission and secondary aerosol formation. Biogeosciences 10, 653–667 (2013).

Li, Q. et al. Phase state regulates photochemical HONO production from NaNO3 /dicarboxylic acid mixtures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 7516–7528 (2024).

Eastman, P. et al. OpenMM 8: molecular dynamics simulation with machine learning potentials. J. Phys. Chem. B 128, 109–116 (2024).

Ponder, J. W. et al. Current status of the AMOEBA polarizable force field. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 2549–2564 (2010).

Torabifard, H., Starovoytov, O. N., Ren, P. & Cisneros, G. A. Development of an AMOEBA water model using GEM distributed multipoles. Theor. Chem. Acc. 134, 101 (2015).

Vázquez-Cervantes, J. E. & Cisneros, G. A. Development of imidazolium-based parameters for AMOEBA-IL. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 5481–5493 (2023).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Andrea, T. A., Swope, W. C. & Andersen, H. C. The role of long ranged forces in determining the structure and properties of liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 4576–4584 (1983).

Levesque, D. & Verlet, L. Molecular dynamics and time reversibility. J. Stat. Phys. 72, 519–537 (1993).

Sagui, C., Pedersen, L. G. & Darden, T. A. Towards an accurate representation of electrostatics in classical force fields: efficient implementation of multipolar interactions in biomolecular simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 73–87 (2004).

Shirts, M. R., Mobley, D. L., Chodera, J. D. & Pande, V. S. Accurate and efficient corrections for missing dispersion interactions in molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 13052–13063 (2007).

Gidden, M. J. et al. Global emissions pathways under different socioeconomic scenarios for use in CMIP6: a dataset of harmonized emissions trajectories through the end of the century. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1443–1475 (2019).

Lamarque, J.-F. et al. CAM-chem: description and evaluation of interactive atmospheric chemistry in the community earth system model. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 369–411 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Amplified role of potential HONO sources in O3 formation in North China Plain during autumn haze aggravating processes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 3275–3302 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Improving the representation of HONO chemistry in CMAQ and examining its impact on haze over China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 15809–15826 (2021).

Shen, H. Q. et al. Aerosol iodide accelerates reactive nitrogen cycling in the marine atmosphere. Mendeley Data, V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/5cd46mhd6j.1 (2025).

Community Earth System Model (CESM). http://www.cesm.ucar.edu/models/.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3701101 to L.X. and T.W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42293322 to T.W., 42061160478 to L.X., and W2411028 to Q.L.), the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (15207421 to T.W. and 15217922 to T.W.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M691921 to H.S.), the Hong Kong Scholars Program (XJ202204 to H.S.), and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (P0039835 to T.W.). We thank the Hong Kong Polytechnic University Research Facility in Chemical and Environmental Analysis for providing the ToF-CIMS and X.L. Zhong at Shandong University for her assistance with supplementary experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W., L.X., and H.S. initiated this study. H.S., T.W., L.X., and A.S.-L. devised the research framework. H.S. conducted laboratory experiments, Q.L. performed global model simulations, and F.X. and Y.H. conducted molecular dynamics simulations. H.S., Q.L., F.X., and L.X. wrote the original draft. T.W., A.S.-L., and W.W. revised the paper. All authors discussed the findings and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Prasad Kasibhatla and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, H., Li, Q., Xu, F. et al. Aerosol iodide accelerates reactive nitrogen cycling in the marine atmosphere. Nat Commun 16, 8148 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63420-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63420-3