Abstract

Compositional heterogeneity in metal/nitrogen-doped carbons (M-N-Cs) complicates the fundamental elucidation of the intricate interplay between the active metal species that rule the reactivity of single atomic catalysts (SACs). This study unveils the electronic disruptions of cobalt nanoparticles (Co NPs) to the catalytic behaviors of cobalt single-atom (Co SA). The intense electronic communications between high-density Co NPs and Co SA sites lead to dissociation O3 on the high-spin Co SA sites to generate surface-confined hydroxyl radicals (•OH). However, the tandem electron transfer yields superoxide radical (O2•–) with low reactivity and remarkably reduce ozone utilization efficiency (OUE). In contrast, independent Co SA sites far or free from adjacent Co NPs induce a nonradical O3 activation regime, which markedly improves electron utilization efficiency (~2.9-fold), OUE ( ~ 3.0-fold), and turnover frequency (TOF, ~2.5-fold) of Co SA. The nonradical catalytic ozonation process demonstrates high adaptability to complex water matrices and maintains long-term stability in the treatment of real petrochemical wastewater. The deciphered electronic interplays between metal nanoparticles and single atom sites advance a new paradigm to regulate the selectivity of single atom catalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-atom catalysts (SACs), especially metal/nitrogen-doped carbons (M-N-Cs) with rigid carbon scaffolds and tunable surface chemistry, have emerged as a versatile platform for delicately engineering the electronic interplays with reactants and thermodynamic selectivity1. Additionally, the maximized atom utilization efficiency and uniformly distributed isolated active sites in M-N-Cs substantially promote the reaction kinetics and outperform carbocatalysts with integrated metal nanoparticles (M-NPs), positioning M-N-Cs as a highly promising option for real-world wastewater treatment2,3,4. Nevertheless, the compositional heterogeneity of M-N-C catalysts, particularly the atomically dispersed metal species (M-Nx) with the ubiquitously coexisted graphene-encapsulated M-NPs5, complicates the fundamental explication of the nature of co-existing active sites, hampering unlocking the full catalytic potential and on-demand catalyst design6,7.

Atomically dispersed M-Nx sites are widely accepted as the primary active centers for catalytic reactions, while the undesirable M-NPs formed by the Ostwald ripening effect decrease the utilization efficiency of metal atoms8,9. Efforts have been focused on maximizing the number of M-Nx active sites and eliminating interference from M-NPs formed by their removal10. Generally, elevated annealing temperatures (>900 oC) vaporize the surface-aggregated M-NPs in M-N-Cs and transform them into M-Nx, accompanied by the graphitization of carbon frameworks. Meanwhile, some recent studies suggested that M-NPs encapsulated by few-layer graphene can significantly enhance the reactivity of M-Nx sites through electronic metal-cage interaction (EMCI) due to their electronic interactions11,12. The modulated geometric and electronic properties of M-Nx sites optimize the reactant adsorption and regulate catalytic performance in electrochemical and environmental reactions13,14,15. However, intensified electronic interactions between M-NPs and M-Nx sites may not improve catalytic activity16. The strengthened contact of the reactants on active sites may result in unfavorable adsorption configuration or excessively strong binding, thus altering thermodynamic selectivity and yielding specific intermediates and products. Therefore, decoding the effects of electronic communications between M-Nx and M-NPs on M-N-C catalysts advances the understanding of intrinsic active sites and their synergy in catalysis in terms of kinetics and thermodynamics.

Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation (HCO), as an effective advanced oxidation process (AOP), demonstrates ultrafast kinetics in oxidizing refractory aqueous organic pollutants, relying on the high oxidation potential of O3 (2.05 V) and the reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced from activated O3 on the catalyst surface17,18. To improve intrinsic activity, selectivity and ozone utilization efficiency (OUE), substantial efforts have been devoted to developing efficient catalysts and programming active sites19,20. Additionally, to enhance the adaptability to complex water matrices, fine-tuning the radical and nonradical oxidation regimes in HCO for different thermodynamic selectivity and efficiency has been achieved by modulating the electronic communications between O3 and active sites2,21. However, precise engineering of catalysts’ microenvironment and providing molecular-level insights into reaction kinetics and thermodynamics bottleneck the gap-bridging in the design of highly active and durable catalysts.

Herein, we report an electronic disruption of Co NPs on the catalytic ozonation activity of the single atomic Co-N4 sites by controlling the Co NPs density on the carbon matrix through calcination temperature regulating and mild NH4Cl treatment. The presence of Co NPs around Co-N4 sites induces a radical regime with inferior reactivity for oxidation of aqueous organics. The strong electronic communications between Co NPs and nearby Co-N4 sites enhance the spin state of Co-N4 sites, leading to the catalytic dissociation of adsorbed O3 molecules and initiation of radical-chain reactions that yield surface-bound hydroxyl radical (•OH) and free superoxide radical (O2•–). The radical regime decreases overall electron utilization efficiency in the catalytic ozonation and results in low OUE. In contrast, the isolated Co-N4 sites facilitate the formation of surface-adsorbed O3 complex (*O3) and induce a nonradical oxidation regime via the electron transfer process (ETP), which significantly accelerates the reaction selectivity and OUE. The catalytic ozonation performance of isolated Co-N4 catalysts is then assessed in treating real petrochemical wastewater (PCW). The high chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal efficiency, together with the high adaptability towards various water matrix parameters, envisage its potential for practical purification applications.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations of CoNC-T

The electronic structure and catalytic properties of single-atom (SA) sites on the nitrogen-doped carbon (NC) matrices are sensitive to the electronic environments around, which can be finely tuned by the presence of metallic nanoparticles (NPs)22,23,24. To examine the effect of NPs on adjacent SA sites, we synthesized three CoNC-T catalysts, designated as CoNC-800, CoNC-900, and CoNC-1000, by varying the calcination temperatures at 800, 900, and 1000 °C, respectively (Fig. 1a). A detailed schematic illustration of the strategy for regulating Co NPs and SA content is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 4. At elevated temperatures (≥ 800 °C), partial Co2+ transformed to metallic Co NPs by the reductive carbon scaffold in the carbothermal reduction process11. Simultaneously, some Co species were anchored by N atoms, forming atomically dispersed Co SA sites. This process is driven by the strong binding affinity between Co and N atoms, attributed to the hybridization between the d-orbitals of the transition metal and the 2p orbitals of N1. Combined with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS, Supplementary Table 1), thermogravimetric analysis (TG, Supplementary Fig. 2), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results (Supplementary Fig. 3), the amounts of Co NPs and surface Co SA sites are calculated and compared in Fig. 1b25. As expected, CoNC-900 obtained a significantly lower amount of Co NPs than CoNC-800 (0.85 vs. 3.10 wt.%), while CoNC-1000 exhibited negligible Co NPs (Supplementary Table 2). In contrast, elevating the calcination temperature had a minimal impact on the population of surface Co SA sites (~0.36 wt.%) due to the fixed N content in precursors and the strong hybridization between Co and N orbitals.

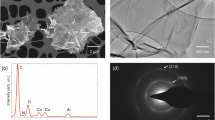

a Schematic illustration of the CoNC-T formation. b Comparison of SA and NPs contents in CoNC-T. c TEM image, d HRTEM image, e AC-HAADF-STEM image and f the corresponding elemental mapping images of CoNC-800. g TEM image, h HRTEM image, i AC-HAADF-STEM image and j the corresponding elemental mapping images of CoNC-900. k TEM image, l HRTEM image, m AC-HAADF-STEM image and n the corresponding elemental mapping images of CoNC-1000.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of CoNC-800 revealed small Co NPs in sizes of 10 - 25 nm (Fig. 1c). High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) further confirmed that these metallic Co NPs were encapsulated in multilayer graphitic carbon, with lattice spacing of 0.35 nm corresponding to the (002) planes of graphitic carbon (Fig. 1d). Notably, the slightly larger lattice spacing of the (002) plane in CoNC-800, compared to the well-ordered graphite (0.33 nm), suggests disorder in the carbon basal plane upon the incorporation of atomic Co species. The lattice fringes observed on the Co NPs were 0.204 nm and 0.185 nm, corresponding to the (111) and (200) crystalline planes of metallic Co, respectively, as corroborated by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) coupled with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) revealed that segregated Co NPs were surrounded by abundant Co SA with a uniform distribution of C, N, and Co elements in CoNC-800 (Fig. 1e, f).

Elevating the calcination temperature reduced the population of encapsulated Co NPs in the carbon matrix. The XRD pattern of CoNC-900 exhibits a declined relative diffraction intensity of metallic Co compared to CoNC-800 (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating a decrease in the content of Co NPs. Upon further elevating the calcination temperature to 1000 °C, Co NPs diffraction peaks diminished, and only graphitic carbon peaks are observed in CoNC-1000. TEM and AC-HAADF-STEM observations confirm that CoNC-900 contains abundant SA and a few Co NPs (Fig. 1g–j), while only atomically dispersed Co sites are discerned in CoNC-1000 with no detectable Co NP (Fig. 1k–n). The reduced content of Co NPs at elevated calcination temperatures was further verified by the gradually weaker magnetic properties of CoNC-900 and CoNC-1000 compared to that of CoNC-800 (Supplementary Fig. 5). In the samples without acid leaching (CoNC-T-NA), the Co contents remained nearly constant across calcination temperatures ranging from 800 to 1000 °C (Supplementary Table 1). After acid washing, the Co contents decreased to 3.48 wt.% for CoNC-800, 1.21 wt.% for CoNC-900, and 0.35 wt.% for CoNC-1000. The increased mesopore volume and defect density in CoNC-T-NA samples at higher annealing temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 3) facilitated the migration of Co NPs toward outer carbon layers, enabling their subsequent removal by acid washing and leading to a reduced Co content14. This was further evidenced by the formation of abundant hollow onion-like shells by leaching the encapsulated Co NPs (Fig. 1l; Supplementary Fig. 7). Correspondingly, the specific surface areas (SSAs) of CoNC-800, CoNC-900, and CoNC-1000 slightly increased compared to those of their non-acid-leaching precursors (Supplementary Fig. 8; Supplementary Table 3).

Decoding the electronic and atomic environments around Co SA sites in CoNC-T

Given the crucial roles of N atoms in stabilizing Co atoms on the NC support, we employed both XPS surveys and soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to decode the structural characteristics. High-resolution N 1 s spectra reveal that N coordinated with Co SA sites (Co-N, 399.2 eV) is identified in all CoNC-T samples, alongside pyridinic (398.2 eV), pyrrolic (400.3 eV), graphitic (401.4 eV), and oxidized N (403.2 eV) species (Supplementary Fig. 9)26,27. The high surface sensitivity of XANES measurement conducted in a total electron yield mode (penetration depth <10 nm) allows the delicate investigations of the surface electronic structure of the doped Co species28. The distinct absorption peak at ~399.5 eV in the XPS N K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra further confirms the presence of Co-N bonding (Fig. 2a), which is critical for anchoring Co single atoms27,29. By comparing the relative deconvoluted areas from XPS N 1 s spectra, the contents of Co-N species show marginal variations with the changes in calcination temperature due to the strong hybridization between Co and N orbitals (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), consistent with the stable amounts of surface Co SA sites. Noted that although the total N content decreased with increasing pyrolysis temperature (Supplementary Table 6), the critical N species (pyridinic and graphitic N) with high thermal stability and responsible for anchoring Co atoms remain sufficient to construct robust Co-N coordination (Supplementary Figs. 9–12).

a N K-edge XANES spectra of CoNC-T. b Co L-edge XANES spectra of CoNC-T. c C K-edge XANES spectra of CoNC-T. d Co K-edge XANES spectra of CoNC-T and reference samples and (e) the corresponding FT-EXAFS curves at R space. EXAFS wavelet transforms of Co K-edge for (f) Co foil and CoPc, (g) CoNC-800, (h) CoNC-900 and (i) CoNC-1000.

In the Co L-edge XANES spectra, the Co L3-edge signals in CoNC-T intensified and shifted positively with increasing calcination temperature (Fig. 2b), indicating a gradual increase in the unoccupied Co 3 d projected state and a higher oxidation state of Co atoms at raised calcination temperatures30. These variations indicate the strong electronic interactions between Co NPs and Co SA, along with the increased electron density at Co SA sites. Notably, absorption peaks at 785 and 800 eV are observed in both CoNC-800 and CoNC-900, likely arising from the metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) effect from Co NPs to the unoccupied ligand orbitals involved in π back-bonding with the Co-N sites31. The MLCT effect confirms the existence of long-range electronic communications between Co NPs and Co SA, facilitating charge transfer from Co NPs to adjacent Co-N4 sites. The enriched electron density over Co-N4 sites induces stronger electronic interactions with O3, promoting its catalytic dissociation into radical ROS. In contrast, no such MLCT effect was observed for CoNC-1000 without Co NPs. The consistent peak features in C K-edge XANES spectra suggest an identical chemical environment in the carbon matrix across all CoNC-T catalysts (Fig. 2c), which establishes a well-defined platform for investigating the electronic interactions between Co NPs and Co SA.

The Co K-edge XANES spectra (Fig. 2d) elucidate the electronic structure and coordination environment of Co species. For CoNC-T, the reduced amount of encapsulated Co NPs correlates with an increase in the oxidation state of the Co species, resulting in a shift of near-edge absorption towards higher energies. The Fourier transform of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra (Fig. 2e) and the corresponding wavelet transform (WT) analysis (Fig. 2f–i) reveal two major peaks at 1.5 and 2.2 Å for both CoNC-800 and CoNC-900, corresponding to Co-N and Co-Co coordination shells, respectively. Nevertheless, the absence of the Co-Co scattering path in CoNC-1000 consolidates the successful removal of encapsulated Co NPs in the carbon matrix. Determining the coordination environment is challenging due to the difficulty in differentiating Co-O from Co-N, as their EXAFS peaks overlap. The absence of the Co-O absorbance peak in the O K-edge XANES spectra (Supplementary Fig. 13) rules out the presence of Co-O bonding. According to EXAFS fitting results, the Co-N coordination numbers for CoNC-T are all close to 4 (Supplementary Fig. 14; Supplementary Table 7), signifying that surface Co SA sites were coordinated with four ambient N atoms in a Co-N4 configuration. Furthermore, significantly lower Co-Co coordination numbers were observed in both CoNC-800 (5.8) and CoNC-900 (3.1) compared with bulk Co (12), stemming from the high surface-to-volume ratio and surface under-coordination state of the encapsulated Co NPs with greatly reduced sizes (Supplementary Note 5)7. In light of the above characterization results, we successfully modulated the contents of Co NPs by finely controlling the heat treatment temperature, giving rise to regulated electronic communications between the SA sites and surrounding NPs.

Influence on activity from Co NPs on Co SA sites

Catalytic ozonation performances of CoNC-T were evaluated through the oxidative degradation of oxalic acid (OA), a probe molecule resistant to direct ozonation (k < 0.04 M−1 s−1) but mineralizable by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated from O3 activation32. As shown in Fig. 3a, all CoNC-T samples exhibit markedly higher activities than their N-doped carbon counterparts (NC-T) without Co species, and SA-dominated CoNC-1000 demonstrates the highest catalytic activity compared to CoNC-900 and CoNC-800 with the presence of Co NPs. Control experiments suggested that molecular oxygen did not play a direct role in assisting the catalytic ozonation process (Supplementary Fig. 15). Additionally, OA removal through adsorption was negligible (<1%) for all CoNC-T catalysts (Supplementary Fig. 16), despite their large SSAs. The electrostatic repulsive force between the negatively charged CoNC-T (Supplementary Fig. 17) and deprotonated OA (pKa1 = 1.23, pKa2 = 4.19) at pH 3 hindered the adsorption process. Furthermore, the robust structure of CoNC-T prevented the dissolution of Co species for secondary pollution and homogeneous O3 activation during the catalytic ozonation process, resulting in negligible leaching of Co2+ (0.02 wt.%). To compare the catalytic activities of CoNC-T catalysts, we normalized the kinetic rate constants by their SSAs to obtain kSSA (Fig. 3b). CoNC-1000 displays a significantly greater kSSA than CoNC-900 and CoNC-800 (5.86 × 10−5, 3.26 × 10−5, and 1.83 × 10−5 g min−1 m−2, respectively). Additionally, the CoNC-1000/O3 system achieves the highest OUE, which is 1.6-fold and 3.0-fold higher than that of the CoNC-900/O3 and CoNC-800/O3 systems, respectively (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 18). To further evaluate ozone utilization and transformation efficiency, we defined the molar ratio (R) of consumed O3 to decomposed OA. A lower R value indicates higher OUE for OA mineralization33. The CoNC-1000/O3 system exhibits the lowest R value (1.1), which increases to 1.6 and 2.5 for the CoNC-900/O3 and CoNC-800/O3 systems, respectively (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table 8), suggesting that the presence of NPs reduces OUE.

a Degradation of OA over NC-T and CoNC-T. b Comparison of kSSA and TOF values of CoNC-T. c Comparison of OUE and R values of CoNC-T. d Effect of DMP on OA degradation over CoNC-T. e Co K-edge XANES spectra of CoNC-800, CoNC-800-N and reference samples, and (f) the corresponding FT-EXAFS curves at R space. g Comparison of kSSA values of CoNC-T and CoNC-T-N. h Comparison of OUE of CoNC-T and CoNC-T-N. Reaction conditions: catalyst loading: 0.02 g L⁻1; [OA]0: 100 mg L⁻1; [DMP]: 0.1 mM; ozone flow rate: 100 mL min⁻1; ozone concentration: 15 mg L⁻1; temperature: 25 °C; initial pH: 3.0. i Comparison of EF values with state-of-the-art HCO catalysts. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three replicate measurements.

To investigate the participation of Co-N4 sites in O3 activation, we added 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanol (DMP), a known selective poison for Co-N sites, to the CoNC-T-induced catalytic systems34,35. The addition of a low concentration of DMP (0.1 mM) had a negligible effect on the direct decomposition of O3 (Supplementary Fig. 19). The significant inhibitory effects of DMP on CoNC-T suggest a predominant contribution of Co-N4 sites to the catalytic ozonation reaction (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. 20). While Co NPs did not directly participate in the reaction due to their encapsulation within carbon layers, their effect on the catalytic performance occurs via neighboring Co SA sites. A radar diagram was also established to correlate the key physicochemical properties of the CoNC-T catalysts with their catalytic performance descriptors, such as kSSA, TOF and OUE (Supplementary Fig. 21). Increasing the annealing temperature from 800 to 1000 °C led to a gradual decrease in nitrogen content due to the decomposition of uncoordinated nitrogen species, while the Co-N coordination amount, single-atom Co content, and SSA remained relatively stable. As the amount of Co NPs within CoNC-T decreased, the corresponding catalytic performances significantly improved, suggesting the negative impact of Co nanoparticles on surrounding Co-N4 sites during O3 activation.

We then employed NH4Cl treatment under an Ar atmosphere at 350 °C to selectively remove the encapsulated Co NPs without affecting the coordination environment of the highly active Co-N4 sites or the integrity of the carbon scaffolds16,36. The resulted catalysts after NH4Cl treatment and subsequent acid washing were denoted as CoNC-T-N. A sharp decrease in Co NPs contents were observed for CoNC-800-N (0.44 wt.%) and CoNC-900-N (0.06 wt.%) compared to their untreated counterparts of CoNC-800 (3.10 wt.%) and CoNC-900 (0.85 wt.%). Notably, their Co SA contents remained unchanged (Supplementary Table 2). TEM and the corresponding AC-HAADF-STEM observations confirm significantly reduced amounts of Co NPs in both CoNC-800-N and CoNC-900-N, with abundant Co SA species (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). The efficient removal of Co NPs is further confirmed by the diminished metallic Co peaks in the XRD patterns (Supplementary Fig. 24), reduced magnetic properties of CoNC-T-N (Supplementary Fig. 25), and a shift of the L3-edge features to a higher energy in the Co L-edge XANES spectra (Supplementary Fig. 26). In addition, the low-temperature NH4Cl treatment did not introduce additional N doping (Supplementary Table 6) or alter the chemical environment surrounding the Co SA sites (Supplementary Fig. 27). The local coordination environments of Co-N4 sites after NH4Cl treatment also remained unchanged. As deciphered by XAS measurements, a higher signal ratio of Co-N to Co-Co bonds in CoNC-800-N than the pristine CoNC-800 further verifies the removal of Co NPs (Fig. 3e, f). More importantly, quantitative EXAFS curve-fitting analysis reveals that the Co SA sites in CoNC-800-N were coordinated with four nitrogen atoms (Supplementary Fig. 28; Supplementary Table 7), consistent with the coordination structure observed in CoNC-800.

The removal of Co NPs in CoNC-T substantially enhanced their catalytic activities, with kSSAs increase of 2.7- and 1.8-fold for CoNC-800-N and CoNC-900-N, respectively (Fig. 3g; Supplementary Fig. 29). Moreover, both kSSAs and OUEs of CoNC-800-N and CoNC-900-N are comparable to those of CoNC-1000, which lacks Co NPs (Fig. 3g, h), suggesting that the presence of Co NPs around the Co-N4 sites would suppress the catalytic activity of the Co SA sites. Notably, the NH4Cl-treated NPs-free CoNC-1000 (CoNC-1000-N) exhibits comparable activity to its untreated counterpart, further suggesting that the NH4Cl treatment had a minimal impact on the catalytic activity of the SA sites.

Based on the above results, turnover frequency (TOF) was calculated using the SA mass loading to determine the intrinsic activity of Co-N4 active sites in CoNC-T (Fig. 3b). The derived TOF for CoNC-1000 with only Co-N4 sites is 1.4- and 2.5-fold greater than those of CoNC-900 and CoNC-800 (28, 20, and 11 min−1, respectively), confirming the detrimental effects of the Co NPs on the activity of the Co-N4 sites. Interestingly, this behavior contrasts with those observed in other electrochemical and AOP-based systems, where NPs synergistically enhance the activity of SA sites13,15,37,38. The catalytic performance of CoNC-1000 was also compared to those of previously reported catalytic ozonation systems in terms of Efficacy Factor (EF, defined as the ratio of contaminant degradation percentage to the amount of dosed catalysts and consumed O3) (Supplementary Table 9). As illustrated in Fig. 3i, the EF of CoNC-1000 outperforms most reported carbon-based catalysts, SACs, metal oxides, and supported metal oxides.

Co NPs-induced selective formation of ROS in catalytic ozonation

The electronic communications between Co-N4 sites and ambient Co NPs also altered the O3 activation thermodynamics to yield different ROS, which in turn affected OUE and catalytic activity. Competitive quenching tests were performed on CoNC-T/O3 systems to identify the primary ROS involved in the catalytic ozonation process for OA degradation, using methanol (MeOH, k•OH /MeOH = 3×109 M−1 s−1) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, k•OH /DMSO = 5.4×109 M−1 s−1) as the scavengers towards surface-adsorbed •OH and both bulk-phase/surface-adsorbed •OH, respectively (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 30)17. Reducing the Co NPs content in CoNC-T changed the primary ROS from surface-adsorbed •OH to nonradical species. Specifically, in the CoNC-800/O3 system, OA degradation is nearly completely suppressed upon the addition of these scavengers, indicating the primary role of the surface-adsorbed •OH in OA degradation. In contrast, both MeOH and DMSO partially inhibit OA oxidation (~30%) in the CoNC-900/O3 system, suggesting a reduced contribution of •OH to OA degradation and an increased contribution from nonradical oxidation. Furthermore, marginal inhibitory effects are observed in the CoNC-1000/O3 system without Co NPs, revealing that OA oxidation proceeded via a nonradical pathway.

a Quenching tests by methanol and DMSO. Reaction conditions: catalyst loading: 0.02 g L⁻1; [OA]0: 100 mg L⁻1; [methanol/DMSO]: 10 mM; ozone flow rate: 100 mL min⁻1; ozone concentration: 15 mg L⁻1; temperature: 25 °C; initial pH: 3.0. b EPR spectra of DMPO-•OH adduct. c Fluorescence microscopy images of the 7-HC solution containing CoNC-T. d EPR spectra of DMPO-O2•– adduct in catalytic ozonation. e In situ Raman spectra for CoNC-800 and CoNC-1000. f Open-circuit potential curves of CoNC-800 and CoNC-1000. g Variations of open-circuit potentials for CoNC-800 and CoNC-1000. h Chronoamperometry (i–t) curves of CoNC-800 and CoNC-1000. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three replicate measurements.

This transition from •OH-based to nonradical-based oxidation, coordinated by the reduction of encapsulated Co NPs contents, was also evidenced by in situ electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spin trapping experiments using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as the spin trapping agent. The characteristic DMPO-•OH signals, identified by a hyperfine coupling constant of aN = aHβ = 14.9 G and an intensity ratio of 1:2:2:139, are observed in both CoNC-800/O3 and CoNC-900/O3 systems (Fig. 4b). The markedly higher DMPO-•OH signal intensity in the CoNC-800/O3 system compared to CoNC-900/O3 suggests a substantial amount of •OH was generated in the CoNC-800/O3 system, consistent with the results of the quenching tests. In contrast, the faint DMPO-•OH signal observed in the CoNC-1000/O3 system, which is comparable to that of the O3/DMPO system without the presence of catalysts, confirms the negligible •OH formation. The removal of encapsulated Co NPs significantly decreased the DMPO-•OH signal intensity for both CoNC-800-N/O3 and CoNC-900-N/O3 systems, exhibiting similar DMPO-•OH signal intensity to that in the CoNC-1000/O3 system. This indicates that Co NPs played a crucial role in promoting •OH generation.

To monitor the spatial distribution of the generated •OH, we used coumarin as a fluorescent probe, which converts to fluorescent 7-hydroxycoumarin (7-HC) upon reaction with surface-confined and free •OH40. As shown in the fluorescence microscopy images (Fig. 4c), blue fluorescence is detected on the surfaces of CoNC-800 and CoNC-900, indicating that the generated •OH is primarily surface-confined. The much weaker fluorescence intensity in CoNC-900 suggests reduced •OH production compared to CoNC-800. In contrast, no detectable 7-HC fluorescence is observed for CoNC-1000, ruling out the formation of surface-bound •OH. The above results underscore the indispensable role of Co NPs in CoNC-T in driving •OH generation.

Furthermore, while O2•– is incapable of directly mineralizing OA due to its moderate oxidation potential (1.44 V), it can act as a radical initiator for •OH generation19,41. The concentrations of the produced O2•– were semi-quantified by the resulted DMPO-O2•– signal intensities. Using methanol as the solvent for the DMPO solution, characteristic peaks of DMPO-O2•– (aN = 14.2 G, aHβ = 11.4 G, and aHγ1 = 1.2 G) appeared in both CoNC-800/O3 and CoNC-900/O3 systems, with a significantly higher DMPO-O2•– intensity in the CoNC-800/O3 system (Fig. 4d). Nevertheless, no such DMPO-O2•– signal is discerned in the CoNC-1000/O3 system, which is dominated by nonradical oxidations. Additionally, the trend in H2O2, as the radical chain termination product of O2•–19, follows the similar trend (Supplementary Fig. 31), indicating that the Co NPs induce O2•– formation from O3 activation.

Apart from free radicals, nonradical species such as singlet oxygen (1O2) and surface-adsorbed activated oxygen species were also examined in these catalytic ozonation systems4. The absence of triplet 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone-N-oxyl (TEMPO) signals in EPR spectra (Supplementary Fig. 32) and singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) signals (excitation wavelength (Ex) of 488 nm and an emission wavelength (Em) of 525 nm) in photoluminescence spectra (Supplementary Fig. 33) exclude the formation of 1O2 in CoNC-T/O3 systems. In situ Raman spectroscopy provides further insights into the dynamic evolution of key surface-adsorbed species (Supplementary Fig. 34). The characteristic peak at 1020 cm−1 in the CoNC-800/O3 system (Fig. 4e) is attributed to surface-adsorbed atomic oxygen (*O), a reactive intermediate (2.43 V) from O3 dissociation42, which would rapidly react with H2O and O3 molecules to generate surface-bound •OH and O2•–, respectively43. Therefore, *O functions as an initiator for generating other ROS rather than directly attacking organics. In contrast, no such an *O signal but a surface-adsorbed O3 (*O3) signal at 620 cm−1 is detected in the CoNC-1000/O3 system41, suggesting that O3 was activated to *O3 without dissociation on CoNC-100044. In the presence of OA, the characteristic Raman signals for *O and *O3 disappeared in the CoNC-800/O3 system and the CoNC-1000/O3 system accordingly, leaving only the Raman signals for adsorbed O2 species (Supplementary Fig. 35)44. This phenomenon indicates active participation of *O and *O3 in OA oxidation.

To further identify different ozone activation behaviors between CoNC-800/O3 and CoNC-1000/O3 systems, catalytic ozone decomposition experiments using saturated ozonated water in the absence of OA were performed (Supplementary Fig. 36). CoNC-800 exhibited a much faster ozone consumption rate and produced significantly higher concentrations of H2O2 compared to CoNC-1000. Furthermore, the intensity 7-HC fluorescence signal of the CoNC-800/O3 system increased progressively with prolonged reaction time (Supplementary Fig. 37), indicating substantial •OH generation. This suggests that in the CoNC-800/O3 system, ozone is readily decomposed on the catalyst surface into *O, which then initiates a series of radical chain reactions to generate secondary ROS such as •OH and O2•–. Contrarily, both the amount of H2O2 produced and 7-HC fluorescence signal detected in the CoNC-1000/O3 system are nearly identical to those observed in single ozonation without the presence of a catalyst, indicating that ozone primarily presents in the molecular form (*O3) without decomposition, consistent with the proposed non-radical pathway. The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) of the catalyst can be indicative to the electronic environment of the reaction interface which affects by the types of the generated ROS in catalytic ozonation45,46. The opposite trend in variations in Cdl after O3 addition for CoNC-800 and CoNC-1000 further confirms the occurrence of radical-based and nonradical-based reaction mechanisms for these two catalytic systems, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 38).

Besides CoNC-T catalysts, we also investigated the produced ROS from NC-T catalysts as the metal-free support for comparison (Supplementary Figs. 39–42). All NC-T catalysts primarily mediated the generation of surface-adsorbed •OH, though with notable fewer •OH production compared to the corresponding CoNC-T. These NC-T catalysts provide baseline activities via radical-based pathways, where their mediocre activities explicate that the introduction of metal species to the metal-free support not only significantly enhances the O3 activation efficiency but also modulates the composition and distribution of ROS by the engineered electronic interactions and adsorption affinity with O3.

In situ electrochemical tests were conducted to examine the oxidation potentials of the formed ROS on the catalyst surface, as well as the electron transfer features during the HCO process. A rotating disk electrode (RDE) was employed to minimize diffusion effects by controlling the diffusion layer and enhancing the mass transport of O3 at high rotation speeds47. This enables open-circuit potential (OCP) measurements to provide intrinsic insights into the surface affinity of the catalysts for O3 molecules and their reaction kinetics. The OCP of CoNC-800 exhibits a greater slope increment compared to CoNC-1000 (Fig. 4f), indicating a stronger interaction between the CoNC-800 and O3. The co-existence of Co NPs and Co SA sites induced strong affinity toward the electrophilic O3, ultimately promoting O3 dissociation to O* and transformation into surface-bound •OH and O2•–. However, CoNC-800 exhibits a reduced potential rise compared to CoNC-1000 (Fig. 4g), possibly arising from the consumption of oxidative *O by H2O and O3. Moreover, CoNC-1000 displays a more pronounced potential drop upon the injection of OA, indicating pronounced electron transfer from OA to surface-adsorbed *O3.

A galvanic oxidation system (GOS) was then employed to investigate different OA oxidation regimes affected by Co NPs. The results showed that the CoNC-1000 system generated a significantly higher current than CoNC-800, and that OA was effectively degraded only in the CoNC-1000-based GOS system (Supplementary Fig. 43). These findings demonstrate that CoNC-1000 facilitated a surface-mediated electron transfer mechanism, wherein electrons were transferred from the weakly adsorbed OA to the CoNC-1000/*O3 complex. OA oxidation in the CoNC-800/O3 system did not follow this surface-mediated ETP. The elevated surface oxidation potential by the produced *O together with the ambient •OH formed a positively-charged activated zone around the catalyst surface. Organics diffusing toward this activated interfacial region can be captured and degraded. This difference in the OA oxidation mechanism is further supported by chronoamperometry (i-t) measurements (Fig. 4h; Supplementary Fig. 44), which show a stronger current that represents the intense electron transfer from OA to *O3 in the CoNC-1000/O3/OA system. Correspondingly, the derived electron utilization efficiency of the CoNC-1000/O3/OA system is 2.9-fold higher than that of the CoNC-800/O3/OA system (Supplementary Fig. 44). Noted that in GOS setup, not only was the degradation kinetics much slower than the heterogeneous catalytic ozonation setup, but partial oxidation of OA was also observed. Given the high surface potential of the *O3 formed on CoNC-1000, a direct oxidation of OA near the catalyst surface could also occur and account for this partial OA removal18,20.

Origins of the electronic disruption effects of Co NPs on Co SA sites

To elucidate the effects of proximity electronic interactions between Co NPs and Co SA sites on the reaction thermodynamics of O₃ activation and dissociation, we constructed two carbon matrix models: one featuring a Co-N4 SA site (CoN4-C) and the other incorporating a cobalt cluster (Co6) beneath the Co-N4 layer (Co6/CoN4-C) as a simplified model to simulate the structure and electronic properties of the Co nanoparticles embedded within the carbon matrix (Supplementary Fig. 45). These models were configured based on the deciphered results from the AC-HAADF-STEM observations (Fig. 1e, m) and the XAS measurements (Fig. 2d, e). The differential charge distribution reveals substantial electron transfer from the Co cluster to the adjacent Co-N4 site in Co6/CoN4-C composite configuration (Supplementary Fig. 46), thereby increasing the electron density of the Co-N4 sites. Furthermore, electron localization function diagrams indicate more delocalized electrons in the Co6/CoN4-C heterojunction compared to CoN4-C (Fig. 5a). This intimate interaction enriches the electron density and enhances delocalization within the carbon framework, leading to improved electron mobility and reduced charge transfer resistance35.

a Electron localization function plots of CoN4-C and Co6/CoN4-C (red represents electrons being more localized, while blue represents electrons being more delocalized). b PDOS of Co 3 d orbital (Co-N4 site) over CoN4-C and Co6/CoN4-C. c In situ EIS spectra for CoNC-800 and CoNC-1000. d Differential charge densities and the corresponding O3 adsorption energy and electron transfer number in CoN4-C-*O3 and Co6/CoN4-C-*O3. Cyan and yellow areas correspond to the respective charge depletion and accumulation. The blue, lilac and gray spheres represent cobalt, nitrogen and carbon atoms, respectively. e PDOS of Co 3 d (Co-N4 site), O 2p and N 2p orbitals over CoN4-C-*O3 and Co6/CoN4-C-*O3. f Illustration of orbital interactions between Co 3 d and O 2p orbitals in CoN4-C-*O3 and Co6/CoN4-C-*O3. g Energy profiles of O3 decomposition over CoN4-C and Co6/CoN4-C. The blue, lilac, gray and red spheres represent cobalt, nitrogen, carbon and oxygen atoms, respectively. IS, TS, and FS are defined as initial state, transition state and final state, respectively. h The proposed mechanisms of O3 activation on CoN4-C and Co6/CoN4-C.

The total density of states (TDOS) analysis demonstrates continuous electron occupation near the Fermi level (Ef) for both CoN4-C and Co6/CoN4-C (Supplementary Fig. 47). Notably, the greater electron density near Ef in Co6/CoN4-C compared to CoN4-C suggests superior conductivity for charge migration48. The projected density of states (PDOS) reveals symmetric electron state densities in the Co 3 d orbitals of CoN4-C, consistent with low-spin Co atoms that lack unpaired electrons (Fig. 5b). Conversely, Co6/CoN4-C exhibits asymmetric and spin-polarized electron densities near Ef, attributed to unpaired electrons on Co atoms stemming from the Co cluster, aligning with Co L-edge XANES results (Fig. 2b)48. Moreover, a significant increase in spin density (the difference in intensity between spin-up and spin-down states) is observed at the CoN4 sites in Co6/CoN4-C, indicating a high spin state49. This elevated spin state in Co6/CoN4-C compared to CoN4-C is further confirmed by a larger calculated effective magnetic moment (μeff, 2.82 vs. 0.02 μB), which widens the spin-related channel in CoN4, thereby facilitating the electron transfer during HCO. Additionally, the upshifted Co d-band center (Ed) toward Ef in Co6/CoN4-C (-0.04 vs. -0.81 eV for CoN4-C) would enhance O3 adsorption, as reflected in the OCP analyses. In situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) further reveals that the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) of CoNC-800 significantly increased following O3 injection (Fig. 5c), potentially attributed to both electronic and steric hindrance caused by the accumulated anionic ROS such as O2•– and the formation of an interfacial “•OH zone”3,40. Additionally, the passivation of the catalyst surface by the high oxidation potential of •OH also contributes to increased Rct. In contrast, CoNC-1000 exhibits a reduction in Rct upon O3 injection (Fig. 5c), suggesting the promoted charge migration upon the formation of the CoNC-1000-*O3 complex. Consequently, the markedly lower Rct of CoNC-1000 (65.8 Ω) relative to CoNC-800 (135.5 Ω) after O3 injection benefited interfacial electron migration to induce nonradical activation of O3 (Supplementary Fig. 48).

As a result, the incorporation of Co clusters induces near-Fermi electronic states and a high-spin state at Co-N4 sites, resulting in stronger O3 adsorption energy (Eads: -1.64 vs. -1.21 eV) and a greater electron transfer number (n: 0.81 vs. 0.58 e⁻) to O3 (Fig. 5d). PDOS analysis reveals a greater overlap between Co 3 d and O 2p orbitals near Ef in Co6/CoN4-C than in CoN4-C (Fig. 5e, f), highlighting the stronger electronic interactions between O3 and Co6/CoN4-C. Furthermore, the high spin Co species in Co6/CoN4-C enhanced the molecular bond order (BO) when interacting with the O 2p orbitals from electron rich O3 by reducing the antibonding state filling50. The greater BO between Co6/CoN4-C and O3 than that between CoN4-C and O3 (2 vs. 1.5) enhanced the O3 adsorption and intensified electron transfer towards O-O bond cleavage. Transition state analysis together with the Gibbs free energy calculations for O3 decomposition on Co-N4 sites reveal that the reaction pathway on Co6/CoN4-C is exothermic and spontaneous (Fig. 5g), while O3 dissociation on CoN4-C requires much higher additional energy to overcome the reaction energy barrier of the transition state (TS). The high electron density at the Co-N4 site coupled with Co6 facilitates catalytic O3 dissociation into *O, which initiates radical chain reactions with H2O and O3 to generate •OH and O2•–, respectively4,43. In contrast, the generation of *O on CoN4-C is endothermic and requires external energy, thereby favoring the formation of a CoN4-C/*O3 complex. The greater upshift of Co Ed and increased spin polarization in CoN4-C after O3 adsorption (Fig. 5f), stemming from the d-orbital energy reordering, enhanced the reactivity of *O3 to directly oxidize organics51.

The electronic disturbance caused by Co NPs on O3 activation pathways over the Co-N4 SA site is schematically illustrated in Fig. 5h, with key elementary reactions in each mechanism. The MLCT effect between the encapsulated Co NPs and adjacent Co-N4 SA sites facilitates charge migration from Co NPs to Co-N4 SA centers, increasing the electron density of the Co atom in Co-N4. As a result, the Co-N4 SA sites exhibit a stronger interaction with O3 and activate it into *O, which subsequently evolves into radical ROS such as •OH and O2•– via radical chain reactions. The produced •OH together with *O elevates the surface oxidation potential and creates a positively charged and reactive domain on the catalyst surface. OA diffusing toward this active region is captured via transient and weak interactions and degraded via electron transfer. While such intense electronic communications between Co NPs and Co SA sites enhance oxidation reactivity because of the enlarged active domain, this radical-based O3 activation process leads to excessive electron transfer and ozone consumption that does not result in proportionally improved pollutant degradation efficiency. Moreover, the complicated radical recombination pathways of •OH and O2•– further decrease the ROS/electron utilization efficiency. Consequently, the overall OUE is reduced, reflected by the deteriorated catalytic performance. Contrarily, O3 can be selectively adsorbed and activated into surface-bound *O3 intermediates, rather than dissociating into *O on an atomically dispersed Co-N4 without the MLCT effect by nearby Co NPs. These *O3 species are more stable and selective for attacking organics by surface-mediated ETP facilitated by weak adsorption and the formation of surface-bound *O3 species, as well as direct oxidation process by the activated interfacial region. The enhanced OUE and improved catalytic activity highlight the importance of suppressing MLCT and maintaining isolated single-atom sites for improving overall ozonation performance. The detailed mechanistic comparison of the reaction pathways for both Co NPs/Co SA and Co SA cases, highlighting the key differences in ozone activation and ROS evolution, is illustrated in Supplementary Note 6.

Practical applications of the CoNC-induced catalytic ozonation

To evaluate the applicability of CoNC-T for practical wastewater treatment, we assessed the performance of the CoNC-T/O3 coupled processes in diverse water matrices. Electrostatic forces between the catalyst surface and aqueous organics are crucial in affecting their interactions and are influenced by the solution pH. Given the low pH point of zero charge (pHpzc) values of the CoNC-T catalysts (~2.8), increasing the solution pH above 3 amplified the electrostatic repulsive force between CoNC-T and the negatively charged OA, prohibiting OA adsorption and thereby decreasing the surface-based oxidation kinetics. (Supplementary Fig. 49). The abundant inorganic anions in real wastewater are typical radical scavengers to quench the radical-based oxidation18. Moreover, they can affect the binding strength between the catalyst surface and the organic reactants by enhancing the ionic strength, disabling the weak outer-sphere interactions18,52. The surface-bound •OH-dominated CoNC-800/O3 system shows suppressed activities in the presence of various inorganic anions (i.e., Cl⁻, HCO3⁻, NO3⁻, and PO43⁻). Additionally, the presence of humic acid (HA) also significantly inhibited the activity of CoNC-800 due to the non-selective nature of •OH (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. 50). In contrast, CoNC-1000 exhibits exceptional performance for OA degradation even in the presence of various inorganic anions and HA, demonstrating superior anti-interference capability. This universal adaptability to background factors can be attributed to the selective nonradical *O3 species and the strong inner-sphere interactions between the O3 and the catalyst surface.

a Removal of OA in different water samples within 60 min. b Reusability tests of CoNC-1000 for OA removal. c TOC removal efficiency of multiple model pollutants in the CoNC-1000/O3 system. d 3D-EEM spectra of six PCW samples before and after 30 min in CoNC-1000/O3 treatment. Reaction conditions: catalyst loading: 0.02 g L⁻1; [OA]0: 100 mg L⁻1; [pollutants]0: 15 mg L⁻1; [anions]: 10 mM; [HA]: 10 mg L⁻1; ozone flow rate: 100 mL min⁻1; ozone concentration: 15 mg L⁻1; temperature: 25 °C; initial pH: 3.0. e Schematic diagram of the continuous-flow catalytic unit. f OA and TOC/COD removal efficiency of PCW-1 in the CoNC-1000/O3 continuous flow system. Reaction conditions: catalyst loading: 0.05 g; solution flow rate: 10 mL min⁻1; ozone flow rate: 0.1 L min⁻1; ozone concentration: 25 mg L⁻1; [OA]0: 100 mg L⁻1; temperature: 25 °C. Error bars represent the standard deviations from three replicate measurements.

In addition, techno-economic analysis (Supplementary Note 7) revealed that the CoNC-1000/O3 system exhibits a markedly lower overall treatment cost (13.3 USD m-3) compared to the CoNC-800/O₃ system (40.9 USD m-3) under batch-scale laboratory conditions, despite the slightly higher material fabrication cost due to the elevated pyrolysis temperature (Supplementary Tables 10-12). This cost advantage is primarily ascribed to its enhanced catalytic activity and OUE. These combined advantages in activity, durability, and cost-effectiveness position CoNC-1000 as a promising and viable candidate for practical implementation in catalytic ozonation processes.

We further examined the catalytic performances of the CoNC-1000/O3 system using tap, river, and seawater as the reaction media. The system sustained high activities in diverse water matrices, consolidating the versatility of the nonradical oxidation system in real-word water environments (Supplementary Fig. 51). For the catalyst reusability test, passivation occurred to CoNC-1000 after five cycles (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Fig. 52). AC-HAADF-STEM observations (Supplementary Fig. 53) combined with XAS analysis results (Supplementary Fig. 54; Supplementary Table 7) rule out the possibility of Co aggregation or the transformation of Co SA into NPs or large aggregates. Nevertheless, the carbon support of CoNC-1000 experienced slight oxidation and corrosion during the cycles. The partial amorphization and increased defective level destroyed the porous structures and enhanced the electron transfer resistance (Supplementary Figs. 55–59). Moreover, demetallation of the Co SA sites was also observed, reflected by the slightly reduced metal loading (Supplementary Table 1). Fortunately, the passivated catalyst can be regenerated via high-temperature calcination in the Ar atmosphere, which helped restore both the graphitization of the carbon support as well as surface chemistry via removing oxidized functionalities and surface contaminants (Supplementary Fig. 60)19,35. More importantly, the CoNC-1000/O3 system effectively mineralized a wide spectrum of organic pollutants, including phenolics, dyes, and antibiotics, demonstrating broad applicability in practical remediation (Fig. 6c; Supplementary Fig. 61).

To assess its potential for real-world applications, the treatment efficiency of CoNC-1000 was evaluated using real petrochemical wastewater (PCW; Supplementary Table 14). After 30 min of treatment, the chemical oxygen demand (COD) values of six PCW effluents were reduced to below 60 mg L⁻1 (Supplementary Table 15), achieving removal efficiencies of 50–70%. Thus, the treated effluents were in compliance with China’s Discharge Standard of Pollutants for the Petroleum Refining Industry (GB 31570-2015, COD < 60 mg L⁻1). Furthermore, three-dimensional excitation-emission matrix (3D-EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy was performed to analyze the changes of dissolved organic matter (DOM) within PCW matrices (Fig. 6d). DOM in PCW is mainly distributed in five regions: region I (Ex < 250 nm, Em < 330 nm), region II (Ex <250 nm, 330 nm < Em < 380 nm), region III (Ex < 250 nm, Em > 380 nm), region IV (Ex > 250 nm, Em < 380 nm), and region V (Ex > 250 nm, Em > 380 nm), corresponding to tyrosine-like aromatic protein, tryptophan-like aromatic protein, fulvic-like substances, soluble microbial by-product-like substances and humic acid-like substances, respectively53. All 3D-EEM peaks in the treated PCW effluents disappeared, indicating that CoNC-1000-based catalytic ozonation effectively removed refractory DOM in PCW. Encouraged by these results, CoNC-1000 was immobilized on quartz wool to ensure high porosity and immersion (Supplementary Fig. 62) and was packed to form a fixed-bed column reactor for a long-term continuous-flow test (Fig. 6e; Supplementary Fig. 63). The CoNC-1000/O3 system demonstrates stable catalytic performance in purifying synthetic wastewater, achieving 100% OA removal over 65 h of operation (Fig. 6f). For PCW treatment, the system maintained high performance, achieving TOC and COD removal efficiencies exceeding 60% over 52 h of continuous operation. The continuously fed organics ensured effective conversion of O3 and utilization of the produced ROS, minimizing damage to the carbon matrix. Furthermore, the fixed-bed continuous-flow treatment resulted in a 3.4-fold decrease in overall treatment cost than batch treatment (Supplementary Table 12). These results highlight the significant potential of CoNC-1000 for extended operation and practical applications in wastewater treatment.

Discussion

In summary, we strategically controlled the density of encapsulated Co NPs surrounding Co-N4 sites to elucidate the intricate electronic interplays between the active metal species in M-N-Cs. By examining their activities and O3 activation mechanisms, we revealed that the electronic disruption induced by Co NPs on surrounding Co-N4 sites adversely affected the catalytic ozonation activity by altering the O3 activation thermodynamics. The over-intensified electronic communications between the high-density Co NPs and Co-N4 sites elevated the spin state of Co-N4 sites, promoting a strong interaction with O3 for its direct dissociation to generate surface-confined •OH. The resulting tandem electron transfer processes within the radical-chain reactions yield O2•– with low reactivity and remarkably reduce OUE. Contrarily, the isolated Co-N4 sites far or free from Co NPs exerted a moderate electron interaction with O3 and induced a non-radical O3 activation regime by forming surface-bound *O3, giving rise to 2.9-, 3.0- and 2.5-fold enhancements in electron utilization efficiency, OUE and TOF, respectively. Additionally, the selective nonradical oxidation demonstrated high efficiency in diverse water matrices and in treating real petrochemical wastewater. This study advances the protocol in modulating the electronic structures of SACs via NPs density control to manipulate their interaction behaviors with ozone toward on-demand selectivity and oxidation capacity with minimal peroxide consumption.

Methods

Chemicals

Ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 99.99%), cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2·6H2O, 99.9%), methanol (MeOH, analytical purity), oxalic acid (OA, 99.9%), phenol (99.9%), p-chlorophenol (4-CP, 99.9%), p-nitrophenol (4-NP, 99.9%), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA, 99.5%), p-chlorobenzoic acid (PCBA, 99.5%), bisphenol acid (BPA, 99%), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, 99.9%), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4, 99.99%), sodium nitrate (NaNO3, 99.9%), sodium chloride (NaCl, 99.9%), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, 98%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37.0%), nitric acid (HNO3, 68%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30.0%), humic acid (HA, 95%), coumarin (99%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 99%), and 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanol (DMP, 99%) were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Reagent Co. Potassium trisulfonate indigo (99.0%), horseradish peroxidase (POD, 95.0%), and N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DPD, 99.0%) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline (DMPO, 99.0%), and 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone (TEMP, 99.0%) were procured from Dojindo Laboratories. Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (SOSG) reagent was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. All chemicals are used without further purification.

Synthesis of CoNC-T and NH4Cl etched CoNC-T-N catalysts

Nitrogen-rich Pleurotus eryngii was chosen as a sustainable and low-cost biomass precursor (C: 42.3%, H: 6.5%, O: 43.5%, N: 5.1%, as determined by elemental analysis). The abundant amino acid groups in Pleurotus eryngii enable strong coordination with Co ions, favoring the formation of atomically dispersed Co species during pyrolysis. Additionally, the intrinsic fibrous and cellular structure of Pleurotus eryngii can be effectively maintained during the freeze-drying and carbonization processes, forming hierarchical porous structures (Supplementary Figs. 64–66). The rationale for choosing Pleurotus eryngii over other biomass precursors as the nitrogen rich carbon support is provided in Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Table 16.

For the synthesis of CoNC-T, freeze-dried Pleurotus eryngii (4 g) was submerged in an aqueous solution containing CoCl2·6H2O (5 mg mL⁻1) and sodium bicarbonate (0.1 g mL⁻1) and soaked for 4 h. The soaked Pleurotus eryngii was then freeze-dried under vacuum, followed by calcination in a tube furnace at 800–1000 °C for 3 h under an Ar atmosphere with a heating rate of 5 °C min⁻1. The calcined products were washed with a 1 M HCl solution at 60 °C overnight to leach out unstable aggregated metal clusters and particles. Finally, the samples were washed with deionized water and dried at 80 °C overnight. The resulting catalysts were denoted as CoNC-T, where T = 800, 900, or 1000, corresponding to the calcination temperature. For comparison, NC-T (T = 800, 900, or 1000) catalysts were also synthesized via similar procedures without the addition of the cobalt precursor.

To further exclude the role of Co nanoparticles, a low-temperature NH4Cl etching method was employed to selectively remove Co nanoparticles without affecting the atomically dispersed Co species and the overall structural integrity of the carbon support16. In a typical synthesis, 0.1 g of CoNC-T and 3 g of NH4Cl were finely ground for 10 min to achieve a uniform black precursor. The mixed precursors were then annealed in the tube furnace in an Ar atmosphere at 350 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 5 °C min⁻1. The calcined products were washed with a 1 M HCl solution at 60 °C overnight. The CoNC-T-N catalysts were obtained by washing with deionized water and drying at 80 °C overnight.

Detailed processes for regulating Co NPs and Co SA populations in CoNC-T catalysts are provided in Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained using a powder X-ray diffractometer (PAN analytical B.V., X’Pert-PROMPD). The excitation light source was Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (ZEISS GeminiSEM 300). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images and corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental mappings were acquired on a transmission electron microscope (Talos F200S). High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM, JEM ARM-200F, JEOL) was employed to characterize the single atoms. Raman spectra was obtained by a LabRAM HR Evolution (HORIBA) spectrometer. N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms were obtained by a Micrometrics Tristar 3000 to characterize the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area (SSA) and Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) pore size distribution. The element compositions of the materials were characterized with an elemental analyzer (Elementar, vario EL cube). A ThermoFisher Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi spectrometer was used to record X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra. Metal contents were analyzed on the Agilent 7500ce inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). X-ray absorption spectra of the samples were collected at the Australian Synchrotron. Three-dimensional fluorescence excitation-emission matrix (3D-EEM) spectra were obtained using a spectrofluorometer (F-7000FL, Hitachi) by scanning at excitation wavelengths in the range of 200–400 nm (5 nm steps) and emission wavelengths in the range of 250–550 nm (2 nm steps). Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was measured on an electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometer (Bruker, EMX plus). A detailed description of characterizations methods is provided in Supplementary Note 1.

Evaluation of catalytic performance

Catalytic ozonation experiments were conducted in a 550 mL semi-batch glass reactor. Ozone was generated from ultrapure oxygen (99.99%) by an ozone generator (Anseros COM-AD-02, Germany) and monitored by an on-line ozone detector (Anseros Ozomat GM, Germany). In a typical experiment, 0.01 g of the catalyst was added to 500 mL of the reaction solution containing 100 mg L⁻1 of OA. The generated gaseous O3, with a concentration of 15 mg L⁻1, was continuously bubbled through a plate diffuser into the bottom of the reactor at a flow rate of 100 mL min⁻1, which was regulated by a mass flowmeter. Samples were then collected from the reactor at specific time intervals and filtered through a 0.22 μm PTFE filter. The filtrate (1 mL) was then quenched by 0.5 mL of Na2S2O3 solution (0.1 M) to consume the unreacted ozone and ROS. OA concentration was analyzed by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatograph (UHPLC, Thermofisher U3000). Total organic carbon (TOC) was analyzed by an organic carbon analyzer (TOC-L, Shimadzu, Japan). Key experiments were performed in triplicate and the results are presented in mean values with standard deviations. For multi-cycle catalyst stability tests, the spent catalyst was recycled by vacuum filtration from the reaction solution, washed three times with ultrapure water, and then dried at 80 °C overnight before next use. The dissolved O3 in the reaction solution was determined by the indigo blue method54. The horseradish peroxidase method was employed to measure H2O2 in solution55. Detailed descriptions of the analysis methods and additional details for the continuous flow tests are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

Calculation of turnover frequency (TOF)

The TOF value was calculated as follows

where, degradation (%) indicates the degradation efficiency of OA, which can be calculated by \(\frac{{{{\rm{C}}}}_{0}-{{\rm{C}}}}{{{{\rm{C}}}}_{0}}\times 100\), and C0 and C are the initial and final concentrations of OA, respectively. The number of active sites is defined as the content of metal in a specific amount of the catalyst in the reaction. Time refers to the duration of the reaction from its initiation to completion.

Calculation of ozone utilization efficiency (OUE)

The OUE was calculated as follows:

where, \({[{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}]}_{{{\rm{consumed}}}}\) represents the amount of consumed O3 during reaction time, \({[{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}]}_{{{\rm{input}}}}\) is the total amount of input O3 during reaction time, \({\left[{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}\right]}_{{{\rm{in}}}}\) is the amount of inlet O3 in the gas phase, \({\left[{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}\right]}_{{{\rm{out}}}}\) is the amount of outlet O3 in the gas phase and \({\left[{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}\right]}_{{{\rm{solution}}}}\) is the amount of O3 in the reaction solution. All of the items in “[]” represent the mass of O3.

Calculation of efficacy factor (EF)

The EF value was calculated as follows:

Calculation of molar ratio of the consumed O3 to the degradation OA (R)

The R was calculated as follows:

where, \({{\rm{n}}}{[{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}]}_{{{\rm{consumed}}}}\) represents the molar amount of consumed O3 and \({{\rm{n}}}{[{{\rm{OA}}}]}_{{{\rm{degraded}}}}\) is the molar amount of degraded OA.

In situ Raman measurement

In situ Raman spectra were recorded using a confocal microscopic Raman spectrometer (LabRAM HR Evolution) equipped with a 532 nm solid-state laser. In a typical procedure, catalyst powder was deposited onto a silicon pallet, which was placed in the center of an in situ reaction cell. A saturated O3 solution was continuously pumped into the reaction cell during the spectra acquisition, which were acquired over the range of 500 to 1200 cm⁻1, with a resolution of 1 cm⁻1 and a duration of 60 s.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were conducted using an electrochemical workstation (CHI 760D, CH Instrument) in a conventional three-electrode configuration, including a working electrode (Φ3 mm glassy carbon electrode), a counter electrode (platinum electrode), and a reference electrode (saturated silver chloride electrode). A Na2SO4 aqueous solution (0.5 M) was used as the electrolyte. Prior to conducting the measurements, ozone was injected to the electrolyte for 30 min to achieve saturation. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed over a frequency range of 10⁻2 to 105 Hz, with an applied amplitude of 10 mV. Open-circuit potential (OCP) was recorded using a rotating disk electrode composed of glassy carbon as the working electrode. O3 and OA were introduced to the system at a certain period of time. Typically, the working electrodes were prepared as follows: 5 mg of catalyst was mixed with 4 mL of isopropanol and 100 μL of Nafion by ultrasonication for 2 h. The resulted ink (5 μL) was dropped on the disk electrode and dried in an oven at 60 °C for 30 min.

The electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) of the catalysts was determined by cyclic voltammetry (CV) within a non-Faradaic potential window. All CV measurements were conducted in a conventional three-electrode system using 0.1 M Na2SO4 as the electrolyte, with a Pt wire as the counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) electrode as the reference. A non-Faradaic potential range was first identified by wide-range CV scans, where no apparent redox peaks were observed. Within this region, CV curves were recorded at various scan rates (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mV s-1). For each scan rate, the capacitive current was extracted at the central potential by averaging the absolute values of the anodic and cathodic currents. The average current values were then plotted against their corresponding scan rates. The slope of the resulting linear fit (i vs. scan rate) was taken as the Cdl.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed with the projector augmented plane-wave (PAW) basis implemented in a Vienna ab-initio simulation package (VASP)56. The plane-waves were cut-off at 550 eV. The exchange-correlations of electrons were described using the generalized gradient approximations (GGA), as proposed by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof57. The DFT-D3 approach was employed to capture the long-range van der Waals interactions58. A vacuum layer of 15 Å was set in z-direction to eliminate the interactions between periodic structures. The energy converge criterion for solving the self-consistent Kohn-Sham equations was set to 10-7 eV. The Brillouin zone was sampled with resolutions better than 0.03 Å-1, using the Monkhorst-Pack scheme59. All the structures in this study were fully relaxed until the Hellman-Feynman forces were less than 0.05 eV/Å. Bader charge analysis was utilized to quantify the localized atomic charges60.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are included within the main text and the Supplementary Information files. All the raw data relevant to the study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Shang, Y., Xu, X., Gao, B., Wang, S. & Duan, X. Single-atom catalysis in advanced oxidation processes for environmental remediation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 5281–5322 (2021).

Liang, L. et al. N-coordinated single cobalt atoms catalyst triggering concerted radical-nonradical process in catalytic ozonation for efficient water decontamination. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 354, 124149 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Manipulating selectivity of hydroxyl radical generation by single-atom catalysts in catalytic ozonation: Surface or solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 17753–17762 (2022).

Ren, T. et al. Single-atom Fe-N4 sites for catalytic ozonation to selectively induce a nonradical pathway toward wastewater purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 3623–3633 (2023).

He, Y., Liu, S., Priest, C., Shi, Q. & Wu, G. Atomically dispersed metal–nitrogen–carbon catalysts for fuel cells: Advances in catalyst design, electrode performance, and durability improvement. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 3484–3524 (2020).

Xiao, F. et al. Atomically dispersed Pt and Fe sites and Pt–Fe nanoparticles for durable proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Catal. 5, 503–512 (2022).

Varnell, J. A. et al. Identification of carbon-encapsulated iron nanoparticles as active species in non-precious metal oxygen reduction catalysts. Nat. Commun. 7, 12582 (2016).

Fei, H. et al. General synthesis and definitive structural identification of Mn4C4 single-atom catalysts with tunable electrocatalytic activities. Nat. Catal. 1, 63–72 (2018).

Yang, Q. et al. Single carbon vacancy traps atomic platinum for hydrogen evolution catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2171–2178 (2022).

Wei, S. et al. Direct observation of noble metal nanoparticles transforming to thermally stable single atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 856–861 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Mechanistic investigations of the pyridinic N–Co structures in Co embedded N-doped carbon nanotubes for catalytic ozonation. ACS ES&T Eng. 1, 32–45 (2021).

Feng, Y. et al. Spherical vs. Planar: Steering the electronic communication between Ru nanoparticle and single atom to boost the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity both in acid and alkaline. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 307, 121193 (2022).

Chen, R., Chen, S., Wang, L. & Wang, D. Nanoscale metal particle modified single-atom catalyst: Synthesis, characterization, and application. Adv. Mater. 36, 2304713 (2024).

Zhao, S.-N., Li, J.-K., Wang, R., Cai, J. & Zang, S.-Q. Electronically and geometrically modified single-atom Fe sites by adjacent Fe nanoparticles for enhanced oxygen reduction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107291 (2022).

Duan, W. et al. Synergistic effects of Co single atoms and Co nanoparticles for electrocatalytic nitrate-to-ammonium conversion in strongly acidic wastewater. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 363, 124812 (2025).

Chen, M.-X. et al. Identification of catalytic sites for oxygen reduction in metal/nitrogen-doped carbons with encapsulated metal nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 1627–1633 (2020).

Yu, G., Wang, Y., Cao, H., Zhao, H. & Xie, Y. Reactive oxygen species and catalytic active sites in heterogeneous catalytic ozonation for water purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 5931–5946 (2020).

Liu, Y., Chen, C., Duan, X., Wang, S. & Wang, Y. Carbocatalytic ozonation toward advanced water purification. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 18994–19024 (2021).

Wang, Y., Duan, X., Xie, Y., Sun, H. & Wang, S. Nanocarbon-based catalytic ozonation for aqueous oxidation: Engineering defects for active sites and tunable reaction pathways. ACS Catal. 10, 13383–13414 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Nanochanneling and local crystallization engineering accelerate multiphase single-atom catalysis for rapid water decontamination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202504571 (2025).

Kong, X., Ma, J., Garg, S. & Waite, T. D. Tailored metal–organic frameworks for water purification: Perfluorinated Fe–MOFs for enhanced heterogeneous catalytic ozonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 8988–8999 (2024).

Shi, Y. et al. Combination of nanoparticles with single-metal sites synergistically boosts co-catalyzed formic acid dehydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 15, 8189 (2024).

Luo, H. et al. Oxidative cleavage and ammoxidation of organosulfur compounds via synergistic Co-Nx sites and co nanoparticles catalysis. Nat. Commun. 14, 2981 (2023).

Zhou, H. et al. Synergistic effect of single atomic Ce sites and CeO2 nanoparticles for boosting oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2404689 (2024).

Liang, S., Jiang, Q., Wang, Q. & Liu, Y. Revealing the real role of nickel decorated nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts for electrochemical reduction of CO2 to CO. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101477 (2021).

Zhu, C. et al. Hierarchically porous M–N–C (M = Co and Fe) single-atom electrocatalysts with robust MN active moieties enable enhanced ORR performance. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801956 (2018).

Hu, W. et al. Embedding atomic cobalt into graphene lattices to activate room-temperature ferromagnetism. Nat. Commun. 12, 1854 (2021).

Bora, D. K. et al. Influence of crystal structure, ligand environment and morphology on Co L-edge XAS spectral characteristics in cobalt compounds. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 22, 1450–1458 (2015).

Du, Z. et al. Cobalt in nitrogen-doped graphene as single-atom catalyst for high-sulfur content lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3977–3985 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. Electronically modified atomic sites within a multicomponent Co/Cu composite for efficient oxygen electroreduction. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100303 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Electronic structure of cobalt nanocrystals suspended in liquid. Nano Lett. 7, 1919–1922 (2007).

Chen, P. et al. Applying both kinetic and thermodynamic measures to promote solar-driven photocatalytic ozonation on defect-engineered porous tungsten oxide. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 362, 124762 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Roles of catalyst structure and gas surface reaction in the generation of hydroxyl radicals for photocatalytic oxidation. ACS Catal. 12, 2770–2780 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Discriminating catalytically active FeNx species of atomically dispersed Fe–N–C catalyst for selective oxidation of the C–H bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10790–10798 (2017).

Li, B. et al. Spin-regulated Fenton-like catalysis for nonradical oxidation over metal oxide@carbon composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2401397 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Facile top-down strategy for direct metal atomization and coordination achieving a high turnover number in CO2 photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19259–19267 (2020).

Luo, J. et al. Transient co-tuning of atomic Fe and nanoparticle facets for self-relaying Fenton-like catalysis. Commun. Mater. 5, 9 (2024).

Zou, H. et al. Single-atom cobalt catalysts encapsulating cobalt nanoparticles with built-in electric field for ultrafast and lasting peroxymonosulfate activation. ACS ES&T Water 4, 2433–2444 (2024).

Bonke, S. A., Risse, T., Schnegg, A. & Brückner, A. In situ electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy for catalysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 33 (2021).

Zhang, S., Quan, X., Zheng, J.-F. & Wang, D. Probing the interphase “HO zone” originated by carbon nanotube during catalytic ozonation. Water Res. 122, 86–95 (2017).

Cheng, Y. et al. Synergistic catalytic ozonation mediated by dual active sites of oxygen vacancies and defects in biomass-derived composites for long-lasting water decontamination. ACS Catal. 14, 4040–4052 (2024).

Li, W., Gibbs, G. V. & Oyama, S. T. Mechanism of ozone decomposition on a manganese oxide catalyst. 1. In situ Raman spectroscopy and ab initio molecular orbital calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 9041–9046 (1998).

Yu, G. et al. Mechanism of ozone adsorption and activation on B-, N-, P-, and Si-doped graphene: A DFT study. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 133114 (2022).

Zhu, Y. et al. Rapid ozone decomposition over water-activated monolithic MoO3/Graphdiyne nanowalls under high humidity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309158 (2023).

Shin, S.-J. et al. On the importance of the electric double layer structure in aqueous electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 174 (2022).

Li, P., Jiao, Y., Huang, J. & Chen, S. Electric double layer effects in electrocatalysis: Insights from ab initio simulation and hierarchical continuum modeling. JACS Au 3, 2640–2659 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Gao, M.-M., Wang, X.-H., Wang, S.-G. & Liu, R.-T. Enhancement of oxygen diffusion process on a rotating disk electrode for the electro-Fenton degradation of tetracycline. Electrochim. Acta 182, 73–80 (2015).

Lv, Q. et al. Atomic ruthenium-riveted metal–organic framework with tunable d-band modulates oxygen redox for lithium–oxygen batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23239–23246 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Spin-related electron transfer and orbital interactions in oxygen electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003297 (2020).

Nørskov, J. K., Abild-Pedersen, F., Studt, F. & Bligaard, T. Density functional theory in surface chemistry and catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 937–943 (2011).

Liu, K. et al. Insights into the activity of single-atom Fe-N-C catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 2075 (2022).

Hayes, K. F. et al. In situ X-ray absorption study of surface complexes: Selenium oxyanions on α-FeOOH. Science 238, 783–786 (1987).

Chen, W., Westerhoff, P., Leenheer, J. A. & Booksh, K. Fluorescence excitation−emission matrix regional integration to quantify spectra for dissolved organic matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 5701–5710 (2003).

Bader, H. & Hoigné, J. Determination of ozone in water by the indigo method. Water Res. 15, 449–456 (1981).

Bader, H., Sturzenegger, V. & Hoigné, J. Photometric method for the determination of low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide by the peroxidase catalyzed oxidation of N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DPD). Water Res. 22, 1109–1115 (1988).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Tang, W., Sanville, E. & Henkelman, G. A grid-based bader analysis algorithm without lattice bias. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 084204 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Y.W. and C.C. greatly appreciate the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22478426 and 22278436). Y.W. acknowledges the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by BAST (No. 1101020370359). This work was also supported by the Australian Research Council (FT230100526 to X.D., FL230100178 to S.W. and DP230102406 to X.D.). Part of this work was carried out on the X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy, Medium Energy X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy and Soft X-ray Spectroscopy beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron, part of ANSTO. This research was supported by an AINSE Ltd. Postgraduate Research Award (PGRA). Z.L. and K.Y. appreciate the financial support from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council General Research Fund (16211421) and the Innovation and Technology Fund (ITS/035/22).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and Y.W. designed the research. Y.L. carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. J.Y. and W.Z. assisted to run catalytic tests and perform characterizations. K.H., Z.L., and K.Y. performed the STEM tests. Z.-S.Z. performed the XAS characterization and analysis. C.C. contributed new reagents/analytic tools. Y.W., X.D., and S.W. further revised the manuscript. Y.W., X.D., and S.W. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions