Abstract

The ferroelectricity in nanoscale HfO2-based films enables their applications more promising than that of the perovskite oxides, taking into account the easy compatibility with the modern silicon-based semiconductor technology. However, the well-known polar orthorhombic phase is thermodynamically metastable, making the applications of HfO2-based ferroelectrics challenging in terms of uncontrollability and consequently instability of the physical performance in electronic devices. Here we report the robust ferroelectricity in stable monoclinic Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 single-crystalline films, which was known as non-polar before. The as-prepared films display high endurance performance of wake-up free and non-fatigue behavior up to 1012 cycles. Multimode imaging under aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy reveals that such an unexpected ferroelectric behavior is resultant from an antiphase boundaries-derived monoclinic polar variant (space group, Pc) intergrown with the nonpolar monoclinic phase (P21/c). The switching barrier for the stable polar variant is only 20~50% of that for the metastable orthorhombic phase according to the calculation by the nudged elastic band method. These findings provide a practical approach for designing robust ferroelectricity in hafnia-based materials and would be helpful for the development of lower energy-cost and long-life memory devices compatible with integrated circuit technology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ferroelectric materials have a wide range of applications in next-generation switching, logical, and memory devices. However, the widely-studied perovskite-type ferroelectrics are getting limited in practical applications owing to the scaling effects1 and a low compatibility with the existing Si technology2. The emergent ferroelectricity in doped HfO2 films3 has broken the traditional paradigm and inspired a renewed interest in ferroelectric devices due to the wealth of advantages, including the simple binary structure, robust nanoscale ferroelectricity4, high compatibility with the metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology5,6 and desirable physical properties4,5,7,8,9,10.

Nevertheless, HfO2-based ferroelectric films are usually in the form of polycrystalline and multiphase structures11,12. Despite the prevalent polar orthorhombic phase13 and a complementary rhombohedral ferroelectric phase14 in polycrystalline films, the polymorphic nature of HfO2 definitely blur the crucial structural origins of the ferroelectricity and the mechanism of polarization switching. Great efforts have been made to fabricate high-quality, epitaxial, single-crystalline films15,16,17,18, stabilize the polar phases19,20, and improve the ferroelectricity4,21, however, these efforts are still challenging at the present stage. These challenges are because of the fact that the orthorhombic phase (space group, Pca21), which is known to result in the ferroelectricity, is thermodynamically metastable4,7,22,23. So far, various strategies, such as volumetric confinement7,9, dopant concentration24,25, strain26, defect concentration21,27, and surface electrochemical state20, have been adopted to try stabilizing the polar phase in HfO2-based films. Especially, the constructed nanocrystal grains, whether in ultrathin films or in superlattices, characterized by the high surface-to-volume ratio in these forms, are widely accepted to stabilize the polar orthorhombic phase, based on the fact of its lower surface energy than that of the monoclinic phase28,29. However, the metastable nature of the orthorhombic ferroelectric phase and the inevitable existence of the nonpolar monoclinic phase12 heavily inhibit the development of HfO2-based films with facile controllability and endurance performance, thereby hindering the applications at the state-of-the-art technology node30.

Herein, we find robust ferroelectricity in stable monoclinic Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 (HZO) single-crystalline films, which feature wake-up free and high cycles of non-fatigue property. Such an unexpected ferroelectric behavior is clarified to result from a polar variant intergrown with the nonpolar monoclinic phase. Atomic imaging together with the first-principles calculations indicate that the ferroelectric variant originates a polar state at the antiphase boundaries (APBs), which feature a translation vector of half of the diagonal along [101] direction of the nonpolar monoclinic phase in the HZO films. The constraint of the lattice distortion at the APBs makes the symmetry breaking from the centrosymmetric to the polar variant. More importantly, repeated antiphase boundaries at the unit-cell level in the non-polar monoclinic phase are found to result in the formation of a stable polar phase in the single-crystalline films with much lower switching barrier (0.102 eV/u.c.), and consequently makes the as-received film display higher endurance behavior compared with that of the metastable orthorhombic phase.

Results

A series of HZO films with the thickness of 10 nm, 15 nm, and 65 nm, respectively, were deposited on a (001)-oriented Y2O3:ZrO2 (YSZ) substrate using the pulsed laser deposition (PLD) method. In these HZO films, the stoichiometric ratio of Hf and Zr is calculated as about 1:1 based on the atomic-resolved EDS elemental maps (Supplementary Fig. 1), which is consistent with the Hf05Zr0.5O2 target used. All the as-grown films are single-crystallized, as seen in the spectrum of a representative XRD θ−2θ scan of the 65 nm HZO film (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Only (001) reflection of the monoclinic phase (m-HZO) at ~17° is identified together with the (001) reflection of the YSZ substrate (Fig. 1a), no reflection of other phases being observed (Supplementary Fig. 2). The clear Laue oscillations near the m-HZO (001) diffraction peak suggest a high quality of the crystallization and a smooth interface between the YSZ substrate and the HZO film. The crystallinity of the film is further confirmed according to the XRD rocking curves, which measure the lateral coherence length and the crystallite tilt. As shown in Fig. 1b, the rocking curve is dominated by a sharp peak with the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.013°, indicating the high crystallinity. In the symmetric (001) reciprocal space map (RSM) shown in Fig. 1c, the two reflections of the YSZ substrate and the HZO film have the same in-plane component (Qx) which indicates that the single crystal HZO film is coherently strained and its in-plane lattice parameter matches with that of the YSZ substrate. The broadening of the m-HZO (001) peak might result from the thickness effect, the crystal lattice distortion or even the variation in crystallite domain sizes31. The surface topography of the HZO film is further characterized by the atomic force microscopy (AFM), and the average roughness (Ra) is 762 pm for the region shown in Fig. 1d. The films with thickness of 10 nm and 15 nm are also single-crystallized with the monoclinic structure (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4, 5). The largest FWMH for the 15 nm HZO film attributes to the defect clusters in this film (Supplementary Fig. 6), which could be induced by the accidental fluctuations in laser power during the film deposition. To directly visualize the epitaxial system in real space, cross-sections of the HZO/YSZ (001) sample with a film thickness of 65 nm are prepared for transmission electron microscopic (TEM) observations. The diffraction contrast in the HZO film is comparable with that of the YSZ substrate, as seen in the bright field (BF) TEM image (Fig. 1e), which indicates that the orientation of the film crystal is basically the same as that of the substrate. The high-quality epitaxial growth is further supported by the elemental mapping, shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, where all the elements are distributed in a homogeneous manner. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns along [100] and [010] zone axis, respectively, are obtained in the cross-sectional specimens which are prepared in two perpendicular directions. A primitive monoclinic lattice with β ≈ 100° can be derived according to the SAEDs. In addition, in the [010] electron diffraction pattern (EDP), the h00 reflections with h = odd are extinctions, which indicates the presence of c glide on the (010) plane and therefore a space group of P21/c with the lattice parameter of a = 5.1 Å, b = 5.2 Å, c = 5.3 Å, β = 99°. As a result, the single-crystalline HZO films with the structure being monoclinic phase are epitaxially grown using the PLD method, which is different from the polar orthorhombic HZO films fabricated by atomic layer deposition32.

a XRD θ−2θ scan of a 65 nm HZO film with the monoclinic (m) structure. b Rocking curve of the m-HZO (001) peak showing the high crystallinity of the film. c RSM analysis, indicating the coherence of the HZO film on the YSZ substrate and its in-plane lattice parameter of the film matches with that of the substrate. d AFM image showing the surface topography of the HZO film with the average roughness of 762 pm. e A cross-sectional BF TEM image of the HZO film. f, g SAED patterns of the HZO film along [100] and [010] zone axis, respectively.

It is known that the stable monoclinic phase with space group of P21/c is nonpolar in HfO2-based materials. However, it is of great interest to find that the above monoclinic HZO single-crystalline film displays an unexpected robust ferroelectric property. The vertical and lateral PFM images in Supplementary Figs. 8, 9 suggest the robust out-of-plane polarization component and a weak in-plane polarization component. As shown in Fig. 2a, b, the local PFM amplitude and phase hysteresis loops acquired using piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) suggest the ferroelectric switching behavior. The local amplitude hysteresis loop in Fig. 2a shows a characteristic butterfly loop. Also, the 180° phase change is reflected in the local phase hysteresis loop under external electric field (Fig. 2b). Besides, the HZO film displays the high endurance performance of wake-up free and shows non-fatigue up to 1012 cycles at the test condition of 10 V and 10 MHz (Fig. 2c) using in-plane interdigitated Ti/Au (10 nm/100 nm) electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 10), which is much more remarkable (Fig. 2d) compared with those reported in the literature14,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. The asymmetric endurance property in Fig. 2c is expected to be due to the non-uniform electric field and strain distribution at the inter-digitized electrodes and the structural clamping in the HZO films. The ferroelectricity of the HZO film is further qualitatively confirmed by the polarization-electric field curves, endurance tests at varying electric voltages and varying frequencies (Supplementary Figs. 11–16) and the polarization current responses (Supplementary Fig. 17), despite the faint polarization switching current signals. It is noted that the constant polarization values in endurance tests at varying frequencies (Supplementary Figs. 14–16) attribute to the fixed reading frequency of 5 kHz. Despite this, it is seen that the present HZO film with the stable polar monoclinic phase displays the highest endurance behavior in the form of single-crystalline film fabricated by PLD method, compared with the prevalent polycrystal HfO2-based films.

a, b Local PFM amplitude and phase hysteresis loops. The intergrowth of the polar variant with the non-polar monoclinic matrix makes the as-grown films displays local ferroelectric switching behavior. c Endurance property of the polar phase, displaying the non-fatigue feature up to 1012 field cycles at 10 V and 10 MHz. d The endurance performance of the present monoclinic HZO single-crystalline film, comparing to other reported HfO2-based ferroelectric films with polycrystalline structure14,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

To illuminate the structure origin of the macroscopical ferroelectricity, extensive investigation on the detailed microstructures in the HZO films is further performed, benefiting from the single crystal epitaxially grown on a YSZ substrate. In addition to the cross-sectional TEM observation as that in Fig. 1e–g, planar-view imaging is also performed, as exampled in the dark-field TEM image and low-magnification HAADF-STEM image in Fig. 3a. It is of interest to find that the HZO film features high-density domain boundaries with the line-shaped contrasts approximately perpendicular to the [010] and [100] directions. The growth of the HZO film is likely in the columnar manner (inset in Fig. 3a), and the high-density domain boundaries in the single-crystalline HZO films might be derived from the column coalescence during the film growth42,43,44. The monoclinic lattice of the films is further supported by [001] EDP (Fig. 3b) acquired by slightly tilting the film normal. In order to figure out the lattice distortions particularly at the domain boundary, multimode imaging techniques which include integrated differential phase contrast (iDPC)-STEM and differential phase contrast (DPC)-STEM are alternatively applied together with the high angle angular dark-field (HAADF)-STEM to display all the elements at the atomic scale. The contrast in the iDPC-STEM image is approximately linear to the atomic number, which is helpful for simultaneously imaging heavy and light elements. Besides, the DPC-STEM technique could directly provide the electric field at the atomic scale45,46. Accordingly, the projections of Hf/Zr and O atomic columns along [001] direction of the monoclinic phase are clearly imaged at the atomic scale (Fig. 3c), and alternatively, atomic-resolved Hf/Zr arrays are visualized in the HAADF image and composition maps with single element (Fig. 3d–f). Although the domain boundaries in the monoclinic HZO phase are hard to be discernible in the HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 3g), they emphasize themselves as the antiphase domain boundary (APB) in the iDPC-STEM image (Fig. 3h). Contrast resultant from the structural distortion at the APB is also remarkable in the DPC-STEM image (Fig. 3i).

a Dark-field TEM image with the high-density domain boundaries. Inset is the low-magnification HAADF-STEM image, suggesting the manner of columnar-like growth. b SAED pattern of the HZO film along the [001] zone axis. c Atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM (left panel) and iDPC-STEM (right panel) images of the monoclinic HZO. Insets are the zoom-in HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images displaying the detailed distribution of Hf/Zr- and O- atomic columns. d–f HAADF-STEM image and corresponding EDXS elemental maps of Hf- and Zr- atomic columns. g Atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM image in which an antiphase domain boundary is marked with a pair of arrows. h iDPC-STEM image corresponding to the area in (g), oxygen ions are visualized. i DPC-STEM image, showing electric field modulation at the antiphase domain boundary.

The high-density APBs in HZO films are schematically illustrated in Fig. 4a. Two manually orthogonal directions namely [001] and [100], both of which are parallel to the boundary plane, are selected for imaging the Hf/Zr and O atomic distribution at the domain boundary. According to the zoom-in HAADF-STEM (Fig. 4b) and iDPC-STEM (Fig. 4c) images along the [001] direction, the projection of the structural unit features the trapezoid-like (marked in yellow) and inverted trapezoid-like (marked in green), and they are alternately stacked along [010] direction. However, the periodic stacking is interrupted at the domain boundary (highlighted by the yellow arrow pair). Furthermore, the O-atomic columns marked with small balls are clearly seen in the iDPC-STEM image, and the O-ionic displacements feature an alternative upward and downward array in the monoclinic phase, highlighted with green and red arrows (Fig. 4c). It is of interest to find that, at the domain boundary, the periodicity of O-ionic displacements is broken, leaving a paired O ions within the Hf/Zr sublattice. It is noted that the paired O ions are located at the non-central position of the four surrounding Hf/Zr ions. Similar imaging modes are also performed to focus on the antiphase boundary along the [100] zone axis (Fig. 4d-g). According to the experimental images, the atomic model of the antiphase boundary is constructed and the projections of the optimized atomic structure along the [001] and [100] zone axes are displayed in Fig. 4h and 4i, respectively. The domain boundary is characterized by a crystal translation of (1/2)d100 in (010) plane projected along [001] zone axis (Figs. 4h) and (1/2)d001 in (010) plane projected along [100] zone axis (Fig. 4i), respectively. As a result, in three dimensions the antiphase domain boundary is located in (010) plane with a crystal translation of half of the diagonal along [101] direction, which might induce structure modulation and even phase transitions47. Based on the HAADF-STEM image (Supplementary Fig. 18a) and geometric phase analysis (GPA)48,49,50, remarkable shear strain is revealed at the APB (Supplementary Fig. 18b). Furthermore, based on the atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM image, the position of each atomic column can be measured by fitting the atomic columns as 2D Gaussian peaks51,52,53. By doing so, the lattice rotations along both in-plane and out-of-plane directions are acquired as shown in Fig. 4j–l. In a word, despite the non-polar nature of the monoclinic HZO phase, it is the formation of APB that leads to local lattice distortion and the symmetry breaking from the centrosymmetric to a polar variant.

a Schematic illustration of the APBs in HZO film. b, c Planar-view atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images in which an APB is arrowed in yellow. Green and red arrows in (c) denoting the O-ionic displacements. d, e Cross-sectional atomic-resolved HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images, an APB is located in the central area of this image. f, g Zoom-in HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images of the yellow rectangles in (d) and (e). Atomic structure of the APB derived from the first-principles calculations, along the [001] and [100] zone axis, respectively. Blue dashed lines across the APB in (h, i) highlight the APB-induced atomic displacement; Green, blue and red balls indicate the O- atomic columns in left domain, right domain and antiphase boundary, respectively; Grey, purple and yellow balls denote the Hf/Zr atomic columns in left domain, right domain and antiphase boundary, respectively. j, Cross-sectional atomic-resolved iDPC-STEM image of the antiphase boundary. k, l In-plane lattice rotation (RX) and out-of-plane lattice rotation (RY) corresponding to the area in (j). Lattice modulation is revealed based on the RX and RY maps.

In addition to the single APB as discussed in Fig. 4, repeated (010) APBs at the unit-cell level are frequently observed in the present study, showing a lamella structure embedded in the non-polar monoclinic phase. The thickness of the lamella corresponds to 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8 unit cells as seen in Fig. 5a–e. The localized structures in the lamella are modulated because of the APB-induced atomic displacement, as revealed in the RX maps in Fig. 5f–j. Thus, the Hf/Zr and O sublattices in the lamella are different from their counterparts in the monoclinic matrix, as highlighted in Fig. 5k, l. According to the polar character at the single APB, the expansion of APBs with the step of unit cell is expected to result in a polar variant (APB phase) with a specific symmetry. Taking a lamella with thickness of 8 unit cells as an example, the APB-stabilized phase is shown in the iDPC-STEM image (Fig. 5m), which displays the different Hf/Zr sublattice characters from the polar orthorhombic phase (Supplementary Figs. 19, 20). The reversed O-displacement vector map (Fig. 5n), extracted from the iDPC-STEM image in Fig. 5m, clearly exhibit the polar state along the [00\(\bar{1}\)] direction. To illuminate the symmetry of this polar variant, imaging along the [010] zone axis is carried out, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 21a. The intergrowth of the polar variant and monoclinic matrix is displayed in the atomic-resolved iDPC-STEM images, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 21b. Region 1 and 2 marked in Supplementary Fig. 21b correspond to the monoclinic phase (P21/c) of the matrix and the new polar variant, respectively. It is noted that the new polar variant features the same β angle with the P21/c phase (Supplementary Fig. 21c, d), suggesting that it is a monoclinic phase as well.

a–e Cross-sectional atomic-resolved iDPC-STEM images showing the intergrowth of the polar variant with the m-HZO phase. The polar variants feature lamella with thickness of 2 u.c., 3 u.c., 4 u.c., 5 u.c. and 8 u.c., respectively. f–j The RX maps corresponding to (a–e). k, l Enlarged HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images of the 3 u.c. antiphase boundary, giving the detailed distribution of Hf/Zr- and O- atomic columns. m, n Enlarged iDPC-STEM image of the FE-HZO phase (black rectangle in (e)) and corresponding reversed O-displacement vector map, suggesting the ferroelectric displacements in FE-HZO.

According to the atomic mapping, the difference of Hf atomic chains in the APB phase and those in monoclinic phase is remarkable. In addition, the zigzag characteristic of the Hf atomic chains parallel to the APB in the APB phase is similar to that in the monoclinic phase. Thus, a new structural variant of HfO2 is built by setting the coordinates of Hf atoms in the [010] direction to be y = 0.25 and y = 0.75, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 22a. By fixing the y coordinates of Hf atoms and optimizing the positions of O atoms, the resultant structure is still non-polar monoclinic, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 22b. It is seen that there are two O columns inside a parallelogram of four Hf atomic columns (see the shaded parallelogram in Supplementary Fig. 22b), while the experimental images suggest that there is only one O atomic column, as shown in Fig. 5l, m. Inspired by the experimental observations, O vacancies are introduced in this structure sequentially and the most stable structures at different vacancy concentrations are presented in Supplementary Fig. 22c–f. The atomic configurations shown in Supplementary Fig. 22f could be assigned a polar phase with the space group of Pc. This is consistent with the monoclinic nature of the polar variant revealed in Supplementary Fig. 21. The role of oxygen vacancies on stabilizing the APB-derived monoclinic polar variant is also confirmed by the increased volume of APBs by growing and annealing the HZO films at the low oxygen partial pressure of 10-6 Torr (Supplementary Fig. 23). This strategic manipulation of APB proportion would not only enhance the remanent polarization in ferroelectricity measurement but also demonstrate promising technological implications for non-volatile memory applications. It is worthwhile to add that repeated stacking faults in (100) plane of a monoclinic phase, instead of the (010) in the present study, at the unit-cell level could result in the formation of an orthorhombic variant in an AlCo alloy47.

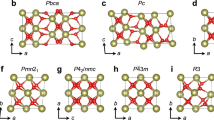

A series of interface models between this polar phase and the nonpolar monoclinic phase are constructed. The orientation relationship between the two phases is (010)P//(010)M, [100]P//[100]M and [001]P//[001]M, where the subscripts P and M represent the polar and monoclinic phases. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 24, the thickness of the nonpolar monoclinic phase is fixed and the thickness of the polar phase varies from 2 u.c. to 8 u.c. By calculating the formation energy of the interface model, it is found that with the increase of the APB width, the interfacial energy decreases, which means the influence of the interface on the APB phase decrease, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 25. In other words, the stability of the APB phase increase with the increase of the APB width. We also studied the stability of the APB phase from the perspective of clamping. By optimizing all lattice parameters of the APB phase, it is found the structure becomes a non-polar phase (a = b = 4.858 Å, c = 5.062 Å, P42/mmc), which indicates that the clamping of the monoclinic phase is important for the stabilization of the APB phase. The optimized atomic structures are shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 26. Based on these atomic structural models, high resolution images under the HAADF-STEM (Fig. 6d–f and Supplementary Fig. 26c, d) and ABF-STEM mode (Fig. 6g–i and Supplementary Fig. 26e, f) are simulated using the software of Dr. probe54. As shown in Fig. 6g-i and Supplementary Fig. 26e, f, the images highlighted in yellow correspond to O-displacement vector maps in the APB phase. Furthermore, in addition to the experimental investigations in Fig. 2a, b, the switching of the stabilized polar monoclinic phase (Fig. 7a) is also studied by the nudged elastic band (NEB) method. The switching barrier is approximately 0.077 eV/u.c. (Fig. 7b), which is only 23% of that of the metastable polar orthorhombic phase (about 0.338 eV/u.c.). We also calculated the switching barrier of the interface model, taking the case of the APB width of 2 u.c. as an example. As shown in Fig. 7c, the switching barrier is 0.170 eV/u.c., which is about 50% of that of the orthorhombic phase. Thus, the polar variant at the extended APB regions could be switched under a smaller coercive field, which is promising for the application in lower energy-cost memory devices.

a–c Atomic structure models of the APB in HfO2 obtained by DFT structural relaxation, with the APB width of 2 u.c., 4 u.c., and 8 u.c., respectively. d–f HAADF images simulated by using the atomic structure models in (a–c). g-i ABF images simulated by using the atomic structure models in (a–c) and corresponding O-displacement vector maps at the APBs.

a Enlarged atomic structure models of the yellow rectangle in Fig. 6c (left panel) and simulated ABF image (right panel), red arrows suggesting the O-displacement vectors. b Switching barrier of the unit cell of the APB phase determined by DFT calculations. c Switching barrier of the APB phase in the interface model with the APB width of 2 u.c. determined by DFT calculations. The red and green arrows denoting the upward and downward polarization, respectively.

In summary, we find the robust ferroelectricity in the monoclinic Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 single-crystalline films, which is derived from the new polar monoclinic variant with the space group of Pc intergrown with the stable non-polar monoclinic phase (P21/c). The structural nature of the polar state is resultant from the lattice distortion at the antiphase boundary, which features a translation vector of half of the diagonal along [101] direction on the (010) plane of the nonpolar monoclinic phase. The constraint of the lattice distortion at the APBs makes the symmetry breaking from the centrosymmetric to the polar variant, in which oxygen vacancies play critical roles. The new polar phase is derived by introducing repeated antiphase boundaries at the unit-cell level in the monoclinic phase, which features robust polarization displacement. The intergrowth of the polar and non-polar phase makes the as-grown films feature the ferroelectric switching under an external electric field with the high endurance of wake-up free and non-fatigue up to 1012 cycles. The switching barrier for the stable polar variant is only 20% ~ 50% of that for the metastable polar orthorhombic phase. Development of future electronic devices requires thin film with single-crystalline structure for the need of controllability and stability of the physical performance in the functional units, consequently, this study provides a new approach for obtaining robust ferroelectricity via engineering planar APBs in single-crystalline hafnium oxide, which would be helpful for developing silicon-compatible ferroelectric electronic devices such as ultra-dense and nonvolatile ferroelectric random-access memory.

Methods

Film deposition details

Using a Coherent ComPex PRO 201 F KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm) for pulsed laser deposition, a set of epitaxial Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films were grown on YSZ (001) substrates. The YSZ (001) substrates employed were commercially sourced without additional chemical or thermal processing. Prior to the deposition of Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films, the substrates were heated to 900 °C and held at this temperature for 20 minutes to ensure surface cleanliness, followed by cooling to the deposition temperature of 850 °C at a rate of 5 °C·min−1. The Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 layers were deposited using a solid sintered target of the same composition, which was pre-sputtered for 20 minutes to remove surface contaminants. During film growth, the following parameters were applied: a repetition rate of 2 Hz, a substrate temperature of 850 °C, an oxygen partial pressure of 70 mTorr, and a laser energy density of 2 J·cm⁻². Subsequently, the as-deposited films were subjected to post-deposition annealing at 850 °C under an oxygen partial pressure of 200 Torr for 20 minutes, followed by slow cooling to room temperature at a rate of 5 °C·min−¹. Another Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 films with increased volume of APBs were grown under the same conditions, apart from being grown and annealed at low oxygen partial pressure of 10-6 Torr.

XRD structural analysis

X-ray θ−2θ scan, rocking curve, and reciprocal space mappings were performed using a high-resolution X-ray diffraction with Cu Kα1 radiation in a X’Pert3 MRD diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical).

TEM sample preparation, TEM/STEM observations

Cross-sectional and planar-view TEM specimens for both TEM and STEM observations were prepared through a conventional procedure of sample preparation involving slicing, bonding, mechanical polishing, dimpling, and final ion milling. Ion milling was performed using a Gatan 695 PIPS system with an initial low angle (5°) and cooling stage, followed by a final polishing step at 0.3 kV for 10 minutes to minimize ionic beam-induced damage. The SAED and bright-field TEM imaging were carried out on a JEOL JEM-F200 transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV. The HAADF-STEM, iDPC-STEM, and DPC-STEM images were acquired using a ThermoFisher Spectra 300 X-FEG aberration-corrected STEM equipped with dual Cs correctors and a monochromator, operated at 300 kV.

STEM result analyses

Strain analyses were performed based on the method of GPA47, which was carried out using Gatan Digital Micrograph software. The atomic positions of Hf/Zr and O were precisely determined through two-dimensional Gaussian peak fitting implemented in Matlab52. This approach enabled accurate measurement of the in-plane and out-of-plane rotations of Hf/Zr sublattices, as well as the displacement of oxygen ions. To improve signal quality, the HAADF-STEM and iDPC-STEM images were preprocessed using a Wiener filter and a low-pass annular mask conforming to the instrument’s resolution limit, both applied to suppress noise.

AFM observations

The local AFM observations were carried out on a commercial AFM system (Asylum Research Cypher ES) at room temperature. The single-frequency mode was used to acquire the topography image of the HZO film. The probes used were Ti/Ir (5/20) coated tips (ASYELEC-01-R) with nominal k = 2.8 N m−1. Polarization switching of the HZO films were observed using a commercial piezoresponse force microscope (Cypher ES, Asylum Research, US) in the dual AC resonance tracking (DART) mode. Conductive Pt/Ir-coated silicon cantilevers (NANO WORLD, ARROW-EFM) were used for PFM hysteresis loop measurements, with the resonance frequency being 75 kHz and the force constant being ∼2.8 N m−1.

First-principles calculations

We have carried out first-principles calculations in the framework of density functional theory as implemented in the Vienna ab-initio simulation package (VASP)55,56. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional57 was used as the exchange-correlation functional for all calculations. The plane wave cutoff energy was set to be 500 eV. The Monkhorst-Pack k-point meshes of 8 × 8 × 8 was adopted for the monoclinic and APB phases and for the interface models containing the APB, the k-point mesh of 8 × 8 × 1 was adopted. The convergence conditions for the electronic self-consistent and the ionic relaxation loops were set to be 10−4 eV and 5 meV·Å−1, respectively. The interface energies of the interface models are calculated by the following equation:

where Etotal is the total energies of the interface model, EP and EM are the total energies of the unit cells of the polar phase and the monoclinic phase, n and m are the numbers of the unit cells of the polar phase and the monoclinic phase in the interface model, and S is the cross-sectional area of the interface model. The factor 4 appears in the denominator since there exist four interfaces in the model.

STEM simulation

The simulated HAADF-STEM and ABF-STEM images were obtained using Dr. Probe based on the multislice method54. During the STEM simulation, an acceleration of 300 kV, a Cs of 0.01 nm, a source size of 0.04 nm, a probe convergence angle of 24 mrad, and collection semiangles of 80−250 mrad for HAADF detector and 11−24 mrad for the ABF detector were used. Partially coherent probe intensity was chosen as the display function. The supercells with the dimensions of 6.85428 nm*4.4070 nm*8.82084 nm were used for the series of extended APBs models constructed via DFT calculations.

Ferroelectricity Measurements

The in-plane interdigitated Ti/Au (10 nm/100 nm) electrodes were patterned on the HZO film using a designed shadow mask by an electric beam evaporator (ULVAC ei-501z). The spacing between the adjacent electrodes was 7 μm, with the width of the interdigital electrodes at 3 μm. The in-plane ferroelectric properties of the film systems were measured by a Keithley 4200A-SCS semiconductor device parameter analyzer at room temperature. The bipolar triangular waveform was applied to obtain the in-plane P-E (P-V) curves of the HZO films. The polarization values in the P-E (P-V) curves were calculated using the charge, the area of the electrode, and the proportion of the polar monoclinic phase in the HZO film. The I-t curves were obtained using the PUND measurement, with the five sequential rectangular pulses being applied: an initial negative pulse followed by two positive pulses and two negative pulses.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are provided in the article and the Supplementary Information. The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Junquera, J. & Ghosez, P. Critical thickness for ferroelectricity in perovskite ultrathin films. Nature 422, 506–509 (2003).

Ambriz-Vargas, F. et al. A complementary metal oxide semiconductor process-compatible ferroelectric tunnel junction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 13262–13268 (2017).

Boscke, T. S., Muller, J., Brauhaus, D., Schroder, U. & Bottger, U. Ferroelectricity in hafnium oxide thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 102903 (2011).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Enhanced ferroelectricity in ultrathin films grown directly on silicon. Nature 580, 478–482 (2020).

Jo, S. et al. Negative differential capacitance in ultrathin ferroelectric hafnia. Nat. Electron. 6, 390–397 (2023).

Schroeder, U., Park, M. H., Mikolajick, T. & Hwang, C. S. The fundamentals and applications of ferroelectric HfO2. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 653–669 (2022).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Ultrathin ferroic HfO2–ZrO2 superlattice gate stack for advanced transistors. Nature 604, 65–71 (2022).

Lee, H.-J. et al. Scale-free ferroelectricity induced by flat phonon bands in HfO2. Science 369, 1343–1347 (2020).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Emergent ferroelectricity in subnanometer binary oxide films on silicon. Science 376, 648–652 (2022).

Yu, L., Zhao, H. J., Chen, P., Bellaiche, L. & Ma, Y. The anti-symmetric and anisotropic symmetric exchange interactions between electric dipoles in hafnia. Nat. Commun. 14, 8127 (2023).

Ma, L.-Y. & Liu, S. Structural polymorphism kinetics promoted by charged oxygen vacancies in HfO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 096801 (2023).

Zhong, H. et al. Large-scale Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 membranes with robust ferroelectricity. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109889 (2022).

Yun, Y. et al. Intrinsic ferroelectricity in Y-doped HfO2 thin films. Nat. Mater. 21, 903–909 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. A stable rhombohedral phase in ferroelectric Hf(Zr)1+xO2 capacitor with ultralow coercive field. Science 381, 558–563 (2023).

Shimizu, T. et al. Growth of epitaxial orthorhombic YO1.5-substituted HfO2 thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 032910 (2015).

Katayama, K. et al. Orientation control and domain structure analysis of {100}-oriented epitaxial ferroelectric orthorhombic HfO2-based thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 102903 (2016).

Li, T. et al. Epitaxial ferroelectric Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin film on a buffered YSZ substrate through interface reaction. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6, 9224–9231 (2018).

Torrejón, L. et al. Growth and structural characterization of strained epitaxial Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 013401 (2018).

Shi, S. et al. Interface-engineered ferroelectricity of epitaxial Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. Nat. Commun. 14, 1780 (2023).

Kelley, K. P. et al. Ferroelectricity in hafnia controlled via surface electrochemical state. Nat. Mater. 22, 1144–1151 (2023).

Kang, S. et al. Highly enhanced ferroelectricity in HfO2-based ferroelectric thin film by light ion bombardment. Science 376, 731–738 (2022).

Mimura, T. et al. Effects of heat treatment and in situ high-temperature X-ray diffraction study on the formation of ferroelectric epitaxial Y-doped HfO2 film. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 58, SBBB09 (2019).

Mimura, T., Shimizu, T., Uchida, H. & Funakubo, H. Room-temperature deposition of ferroelectric HfO2-based films by the sputtering method. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 062901 (2020).

Müller, J. et al. Ferroelectricity in simple binary ZrO2 and HfO2. Nano Lett. 12, 4318–4323 (2012).

Shen, Z. et al. Epitaxial growth and phase evolution of ferroelectric La-doped HfO2 films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 162904 (2022).

Liu, S. & Hanrahan, B. M. Effects of growth orientations and epitaxial strains on phase stability of HfO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 054404 (2019).

Nukala, P. et al. Reversible oxygen migration and phase transitions in hafnia-based ferroelectric devices. Science 372, 630–635 (2021).

Materlik, R., Künneth, C. & Kersch, A. The origin of ferroelectricity in HfxZr1-xO2: a computational investigation and a surface energy model. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 134109 (2015).

Zhao, D., Chen, Z. & Liao, X. Microstructural evolution and ferroelectricity in HfO2 films. Microstructures 2, 2022007 (2022).

Hadnagy, T. Materials and production characterization requirements for the production of FRAM® memory products. Integr. Ferroelectr. 18, 1–17 (1997).

Loke, W. K., Yoon, S. F. & Ng, T. K. and, S.Z, Reciprocal space mapping of GaNxAs1−x grown by RF plasma-assisted solid source molecular beam epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth 243, 427–431 (2002).

Cho, J. W. et al. Atomic layer deposition of epitaxial ferroelectric Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2314396 (2024).

Kashir, A., Kim, H., Oh, S. & Hwang, H. Large remnant polarization in a wake-up free Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 ferroelectric film through bulk and interface engineering. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 629–638 (2021).

M. G. Kozodaev, et al. Mitigating wakeup effect and improving the endurance of ferroelectric HfO2-ZrO2 thin films by careful La-doping. J. Appl. Phys. 125, 034101.034101-034101.034110 (2019).

Chen, H.-H. et al. Ferroelectric polarization enhancement in hafnium-based oxides through capping layer engineering. IEEE J. Electron Devices Soc. 10, 947–952 (2022).

Zhou, D. et al. Wake-up effects in Si-doped hafnium oxide ferroelectric thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 192904 (2013).

Choi, Y. et al. Impact of chamber/annealing temperature on the endurance characteristic of Zr:HfO2 ferroelectric capacitor. Sensors 22, 4087 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Structural and ferroelectric properties of Pr doped HfO2 thin films fabricated by chemical solution method. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 30, 5771–5779 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Large ferroelectric polarization and high dielectric constant in HfO2-based thin films via Hf0.5Zr0.5O2/ZrO2 nanobilayer engineering. J. Materiom. 11, 100922 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Involvement of unsaturated switching in the endurance cycling of Si-doped HfO2 ferroelectric thin films. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 2000264 (2020).

Chen, K.-T. et al. Improvement on ferroelectricity and endurance of ultra-thin HfZrO2 capacitor with molybdenum capping electrode. Electron Devices Technol. Manuf. Conf. (EDTM) 62, 64 (2019).

E. Palstra, H. Celotto, Origin of the increased resistivity in epitaxial Fe3O4 films. Phys. Rev. B 66, 201101 (2002).

Gilks, D., Lari, L., Matsuzaki, K., Hosono, H. & Susaki, T. Structural study of Fe3O4(111) thin films with bulk like magnetic and magnetotransport behaviour. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 17C107–101C107 (2014). 117C107-103.

McKenna, K. P. et al. Atomic-scale structure and properties of highly stable antiphase boundary defects in Fe3O4. Nat. Commun. 5, 5740 (2014).

Shibata, N. et al. Differential phase-contrast microscopy at atomic resolution. Nat. Phys. 8, 611–615 (2012).

Wang, W. et al. Direct atomic-scale structure and electric field imaging of triazine-based crystalline carbon nitride. Adv. Mater. 33, e2106359 (2021).

Li, X. Z., Ma, X. L. & Kuo, K. H. A structural model of the orthorhombic Al3Co derived from the monoclinic Al13Co4 by high-resolution electron microscopy. Philos. Mag. Lett. 70, 221–229 (2006).

Hytch, M. J., Snoeck, E. & Kilaas, R. Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from HREM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 74, 131–146 (1998).

Geng, W. et al. Atomic-scale tunable flexoelectric couplings in oxide multiferroics. Nano Lett. 21, 9601–9608 (2021).

Tang, Y. L., Zhu, Y. L., Liu, Y., Wang, Y. J. & Ma, X. L. Giant linear strain gradient with extremely low elastic energy in a perovskite nanostructure array. Nat. Commun. 8, 15994 (2017).

Geng, W. R. et al. Rhombohedral-orthorhombic ferroelectric morphotropic phase boundary associated with a polar vortex in BiFeO3 films. ACS Nano 12, 11098–11105 (2018).

Anthony, S. M. & Granick, S. Image analysis with rapid and accurate two-dimensional gaussian fitting. Langmuir 25, 8152–8160 (2009).

Tang, Y. L. et al. Observation of a periodic array of flux-closure quadrants in strained ferroelectric PbTiO3 films. Science 348, 547–551 (2015).

Barthel, J. Dr. Probe: A software for high-resolution STEM image simulation. Ultramicroscopy 193, 1–11 (2018). S0304399118301402.

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Hafner, J. Materials simulations using VASP—a quantum perspective to materials science. Comput. Phys. Commun. 177, 6–13 (2007).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 52201018 (W.R.G.), NO. 52571013 (W.R.G.), NO. 51971223 (Y.L.Z.), NO. 51922100 (Y.L.T.), NO. 51901166 (S.R.Z.)), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2021A1515110291 (W.R.G.), 2023A1515012796 (W.R.G.), 2024A1515140162 (W.R.G.)), Guangdong Provincial Quantum Science Strategic Initiative (GDZX2202001, GDZX2302001, GDZX2402001 (X.L.M.)), the Open Fund of the Microscopy Science and Technology, Songshan Lake Science City (202401202 (W.R.G.)), the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences CAS (QYZDJ-SSW-JSC010 (X.L.M.)). Y.J.W. acknowledges the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (No. 2021187). Y.L.T. acknowledges the Scientific Instrument Developing Project of CAS (YJKYYQ20200066), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (Y202048).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.R.G. and Y.J.W. contributed equally to this work. X.L.M. conceived the project on the architecture of quantum materials modulated by ferroelectric polarizations; W.R.G., Y.L.Z., and X.L.M. designed the sample structures and subsequent experiments. W.R.G. performed the thin-film growth, XRD, and PFM observations. W.R.G., Y.L.T. performed the TEM and STEM observations. W.R.G. performed the STEM simulations. Y.J.W. performed the first-principles calculations and digital analysis of the STEM data. S. Zhang, H. Ma, and S. Tuo performed the measurements of the ferroelectric property. All authors participated in the discussion and interpretation of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Minghua Tang, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geng, WR., Wang, YJ., Zhu, YL. et al. A stable monoclinic variant and resultant robust ferroelectricity in single-crystalline hafnia-based films. Nat Commun 16, 8842 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63907-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63907-z