Abstract

Multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence (MR-TADF) materials are promising for organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) owing to their narrowband emission and efficient triplet utilization. However, realizing stable deep-blue emission with high practical efficiency remains challenging, largely due to limited strategies for hypsochromic shifts without compromising photophysical properties. Here, we report a late-stage direct double borylation strategy for B/N-based MR frameworks, which extends π-conjugation resonance, increases transition energy, enhances transition dipole moment, and reduces the S1−T1 energy gap. The proof-of-concept emitter, ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes, exhibits blue-shifted emission compared to its parent molecule while maintaining excellent TADF characteristics, including high photoluminescence quantum yield (93%), narrowband emission (16 nm), and fast reverse intersystem crossing rate (2.05 × 105 s–1). OLEDs employing ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes achieve outstanding performance with >30% external quantum efficiency, high luminous efficacy, and near NTSC color purity. Furthermore, phosphor-sensitized fluorescence device display a minimal efficiency roll-off and long operational lifetime (LT80 > 1000 h at 100 cd m–2), establishing a new benchmark for blue OLEDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) materials have been steadily explored over the past decade due to their ability to harvest both triplet and singlet excitons to achieve 100% internal quantum efficiency (IQE) without employing precious metals1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Usually, conventional Donor-Acceptor (D-A) based TADF molecules reduce the overlap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), which results in small ΔEST and high reverse intersystem crossing rate constant (kRISC) values. However, these molecules exhibit large Stokes shifts and broad spectra from their intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) nature, leading to wide full width at half maxima (FWHM) and poor color purity, limiting their suitability for OLED applications. To address these issues, our group introduced a pioneering concept of multi-resonance (MR)-TADF materials, based on an alternative boron (B)/nitrogen (N)-doped polycyclic aromatic framework. In 2016, we reported the first MR-TADF material, DABNA-19. This molecule exhibits several advantageous features, including narrow-band emission for high color purity and a high absolute photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), making it well-suited for ultrahigh-resolution display applications. Such advantages arise from the alternating localization of the HOMO and LUMO on different carbon atoms within the same benzene ring, which reduces the vibronic coupling between the ground state (S0) and the first singlet excited state (S1), leading to extraordinary narrowband emission. Inspired by this concept, intensive research has been conducted in the field of MR-TADF materials10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Among the developed materials, the π-extended double boron emitter ν-DABNA stands out as a star molecule in OLEDs, owing to its narrow FWHM and exceptionally high external quantum efficiency (EQE) of ~35%11. However, the Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage (CIE) color coordinates of ν-DABNA (0.12, 0.11) deviate from the National television system commission (NTSC) standard for pure blue color (CIE(x,y) of (0.14, 0.08)). For practical applications, precise control over the emission peak is essential to achieve the desired wavelength while preserving excellent photophysical properties.

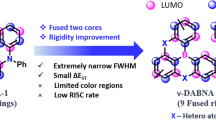

Tuning the emission wavelength can be achieved through frontier molecular orbital (FMO) engineering by introducing electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups at the positions affecting the HOMO/LUMO distribution44,45. Bathochromic shifts can be easily achieved by introducing substituents or extending the π-conjugation. However, achieving deep blue emission, which is crucial for commercial displays, requires effective strategies for hypsochromic shifts, a challenge that remains largely unaddressed in the literature. Figure 1 illustrates ν-DABNA-based blue emitters that exhibit a hypsochromic shift compared to the parent molecule, ν-DABNA. One strategy for achieving a blue-shifted emission is replacing one or two nitrogen (N) atoms with oxygen (O) atoms, forming ν-DABNA-O-Me14 and BOBO-Z46. While these emitters exhibited bluer emissions, they suffered from reduced rate constants for fluorescence (kF) and reverse intersystem crossing (kRISC), leading to a lower device EQE. For example, BOBO-Z reached a maximum EQE of only 14%. An alternative approach is introducing electron-withdrawing fluorine (F) atoms17, as demonstrated in 4F-ν-DABNA47, which also exhibited bluer emission. However, this strategy also resulted in lower rate constants and stability, leading to severe roll-off and shorter device lifetime. Recently, our group reported an approach to achieve blue-shifted emission by replacing two diphenylamine groups with stronger donor azepine (Az) groups at the LUMO distribution positions. The resulting compound, ν-DABNA-Az121, exhibited pure blue EL spectra with CIE coordinates of (0.14, 0.08), approaching NTSC standards. This strategy improved kF and kRISC, enhancing TADF device performance. However, the stronger Az donors raised the HOMO level, promoting charge recombination in this emitter, which limited the further improvements in device lifetime when using sensitizers in the hyperfluorescence (HF) or phosphor-sensitized fluorescence (PSF) systems48,49,50,51. Therefore, the current strategies for achieving hypsochromic shifts in blue emissions for displays are still hindered by these associated drawbacks, limitting OLED technology development. To overcome these challenges, a novel and versatile design strategy is highly demanded to achieve ultra-pure blue narrowband emission while improving device performance.

Herein, we have developed a novel strategy: the late-stage direct double borylation of B/N-based MR frameworks, which effectively extends their fully resonating π-conjugation, resulting in increased transition energy, enhanced transition dipole moment, and smaller S1−T1 energy gap. Based on the advantages of ν-DABNA, we utilized its core skeleton, excluding the two diphenylamine groups, as a parent structural motif to demonstrate our concept. Figure 1 illustrates the designed ν-DABNA-core and its subsequent borylation, incorporating two additional boron (B) atoms attached to mesityl (Mes) groups. The late-stage direct double borylation strategy enables the conjugation expansion of the ν-DABNA-core, thereby enhancing the MR characteristics and facilitating ultra-pure blue emission with an exceptionally narrow FWHM. Furthermore, the expanded conjugation enhances the horizontal dipole orientation of the emitter, leading to improvements in external quantum efficiency (EQE), luminance, and power efficiency52. To achieve high selectivity in the late-stage direct double borylation process, we designed ν-DABNA-M, which was substituted with methyl (Me) and Mes groups for steric protection. Subsequently, borylation occurred at the desired positions, resulting in the formation of the ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes. The synthesized ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes exhibited a narrow FWHM of 16 nm with a λmax of 463 nm in PMMA film. TADF devices based on ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes exhibited a deep-blue EL spectra at 467 nm, with EQEmax over 32% and FWHM of 16 nm. Notably, the PSF device fabricated with ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes exhibited a remarkable low efficiency roll-off and an exceptionally long operational lifetime of LT80 at 100 cd m–2 for over 1000 h, setting a new benchmark for blue OLEDs.

Results

Molecular design and synthesis

Initially, we conducted theoretical calculations using density functional theory (DFT) and higher-level spin-component scaling second-order approximate coupled-cluster (SCS-CC2) methods with the def2-TZVP basis set. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the incorporation of the two additional B atoms effectively extends the π-conjugation, resulting in the HOMO and LUMO of ν-DABNA-B-Mes significantly expanding the electron density distributions in a spatially alternative pattern, thereby enhancing the MR characteristics compared to the ν-DABNA-core. The calculated S0–S1 transition energy for ν-DABNA-B-Mes (3.09 eV) is slightly higher than that of the ν-DABNA-core (3.07 eV), indicating a blue-shifted emission for the former. The transition-dipole moment (μ) values for ν-DABNA-core and ν-DABNA-B-Mes are calculated to be 6.65 D and 9.48 D, respectively. The increased transition-dipole moment of ν-DABNA-B-Mes corresponds to a higher oscillator strength (f), as indicated by the relationship (f ∝ μ2 = [\({{\mbox{q}}\int {{\phi }^{*}}_{{\mbox{LUMO}}}\left({{{\rm{r}}}}\right){{{\rm{r}}}}{\phi }_{{\mbox{HOMO}}}\left({{{\rm{r}}}}\right){{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{3}{{{\rm{r}}}}{{{\boldsymbol{]}}}}}^{2}\)). As expected, the oscillator strength of ν-DABNA-B-Mes (f = 0.8425) is significantly enhanced compared to that of the ν-DABNA-core (f = 0.4470), indicating more efficient S0–S1 transition. Given the strong correlation between oscillator strength and the radiative constant, this enhancement is expected to result in increased fluorescence rate (kF) and molar extinction coefficient (ε). The improved kF and ε will consequently enhance the EQE of OLEDs, both with and without a sensitizer. Furthermore, ν-DABNA-B-Mes exhibited a smaller ΔEST of 34 meV compared to the ν-DABNA-core (43 meV), highlighting the superiority of this molecular design. The calculated spin-orbital coupling (SOC) matrix elements for ν-DABNA-B-Mes and ν-DABNA-core are as follows: (〈S1|\(\widehat{H}\)SOC|T1〉: 0.646 and 0.005 cm–1, 〈S1|\(\widehat{H}\)SOC|T2〉: 0.576 and 0.049 cm–1). The larger rigid and twisted π-conjugated system of ν-DABNA-B-Mes enables enhanced excited-state mixing, reduces energy gaps, and promotes MR-induced CT character, all of which contribute to stronger effective SOC (Supplementary Fig. 2). The smaller ΔEST and larger SOC values for ν-DABNA-B-Mes compared to ν-DABNA-core suggest a higher kRISC, based on the relationship between kRISC, 〈Sn|\(\widehat{H}\)SOC|Tn〉, and ΔEST (kRISC ∝ 〈Sn|\(\widehat{H}\)SOC|Tn〉2/ΔEST). These computational results strongly support the advantages of the late-stage direct double borylation strategy in achieving deep-blue emission and further enhancing the MR-TADF properties. Additionally, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, ν-DABNA-core and ν-DABNA-B-Mes exhibited small RMSD values between the S0 and S1 geometries (0.149 and 0.095 Å, respectively), indicating minimal geometry relaxation and weak vibronic coupling. Huang–Rhys (HR) factors calculated using MOMAP further support this observation, revealing low values primarily associated with low-frequency vibrational modes. These results suggest narrowband emission characteristics, making these compounds well-suited for OLED application.

Energy-level diagrams, frontier molecular orbitals (isovalue = 0.02), and transition energies of a ν-DABNA-core and b ν-DABNA-B-Mes. Transition energies for S1, T1, and T2 were calculated at the SCS-CC2/def2TZVP//M06-2X/6-31 G(d) level of theory in the geometry of S0. Transition-dipole moment for S1 to S0 was calculated at the M06-2X/6-31 G(d) level of theory. SOC matrix elements, SOC (S1–T1) and SOC (S1–T2), were calculated at the M06-2X/TZP//M06-2X/6-31 G(d) level of theory in the geometry of T1 and T2, respectively.

The synthetic route of ν-DABNA-M and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes is illustrated in Fig. 3. Specifically, the Mes and Me groups were introduced to suppress late-stage borylation at the undesired reaction sites. The one-shot borylation precursor 3 was synthesized via a Buchwald-Hartwig amination reaction from compounds 1 and 2, yielding 82%. Compounds 1 and 2 were prepared from commercially available reagents through one or two-step Buchwald–Hartwig amination reactions. The strategic introduction of chlorine (Cl) atoms in precursor 3 is critical for regioselective borylation at the para-positions, acting as orienting groups for the subsequent reaction14,53. The chlorine-directed one-shot double borylation of precursor 3 was achieved by using stoichiometric amounts of BI3, resulting in the formation of ν-DABNA-M-Cl with a moderate yield of 40%. Subsequently, the two directing chlorine atoms were removed in the presence of NiCl2(dppe) and NaBH4, leading to the formation of ν-DABNA-M in a high yield (90%)54. In the final step, the late-stage direct double borylation of ν-DABNA-M was performed via electrophilic borylation with BI3, followed by quenching with Mes-MgBr, resulting in the formation of ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes in 48% yield. The thermal and bond stability of the emitters were evaluated via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and DFT calculations. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, the decomposition temperatures (Td) at 5% weight loss were 443°C for ν-DABNA-M and 455°C for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes, indicating good thermal stability. Bond dissociation energy (BDE) values for C–N and C–B bonds in various electronic states (Supplementary Fig. 8) reveal enhanced bond strength after introducing two additional boron atoms. These results support the improved stability of ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes compared to its parent compound.

The strategy developed here is synthetically novel and generalizable for achieving regioselective borylation at sterically hindered positions that are typically inaccessible. By employing chloro substituents as removable directing groups in a one-shot borylation step, followed by reductive cleavage of the C–Cl bond to regenerate the C–H bond, we enabled mesityl boron substitution at the ortho-position relative to the original Cl group. To the best of our knowledge, this approach has not been reported. In contrast to NOBNacene, which was synthesized by fusing two DOBNA units and introducing mesityl boron groups, resulting in red-shifted emission due to mere π-extension37. Our design allows precise incorporation of mesityl boron at HOMO positions, leading to blue-shifted emission. Importantly, this methodology is applicable not only to ν-DABNA derivatives but also to a broad class of MR-TADF molecules commonly synthesized via one-shot borylation to achieve a blue-shifted emission. TD-DFT calculations further support the generality of this approach, showing consistent blue-shifts upon mesityl boron introduction for several representative MR-TADF scaffolds (Supplementary Fig. 9). This further demonstrates the potential of our strategy to expand the chemical space of π-extended MR-TADF emitters with blue-shifted emission.

Photoluminescence properties

The photophysical properties of ν-DABNA-M and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes were evaluated in poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) films doped with 1 wt% of the compounds (Fig. 4 and Table 1). ν-DABNA-M exhibited a sky-blue emission at 473 nm, with a narrow FWHM of 17 nm and a high PLQY of 92% (Fig. 4a), indicating that ν-DABNA-M retains excellent MR characteristics. In contrast, ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes displayed a deep-blue emission at 463 nm, which is significantly blue-shifted. The FWHM and PLQY of ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes were 16 nm and 93%, respectively, highlighting the effectiveness of late-stage direct double borylation strategy in extending π-conjugation and enhancing molecular rigidity. This modification enables the blue-shifted emission without compromising the photophysical performance. The ΔEST values, derived from the emission maxima of the fluorescence and phosphorescence spectra at 77 K, were determined to be 117 meV for ν-DABNA-M and 109 meV for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes. The transient decay curves for both compounds revealed two distinct components: prompt lifetimes (τF) of 4.60 ns for ν-DABNA-M and 2.60 ns for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes, and delayed lifetimes (τTADF) of 10.0 and 6.90 μs, respectively (Figs. 4b and 4d). The short delayed lifetimes can be attributed to high kRISC values, resulting from the small ΔEST values, which are beneficial for enhanced TADF performance. The rate constants for fluorescence (kF), internal conversion (kIC), intersystem crossing (kISC), and reverse intersystem crossing (kRISC) were calculated using the reported method55,56. The kF values for ν-DABNA-M and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes were determined to be 1.64 × 108 s–1 and 2.57 × 108 s–1, respectively. The shorter τF and higher kF values for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes are consistent with its higher oscillator strength, as predicted computationally. In addition, ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes exhibits a strong absorption band at 456 nm (log ε = 5.46) in toluene, while ν-DABNA-M shows an absorption band at 464 nm (log ε = 5.14) in toluene (Supplementary Fig. 12). These experimental results are in excellent agreement with the computational predictions (Fig. 2). The kRISC values of ν-DABNA-M and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes were 1.22 × 105 s–1 and 2.05 × 105 s–1, respectively. The increase in kRISC value for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes provides strong evidence for the advantages of the late-stage direct double borylation strategy in enhancing TADF properties.

ν-DABNA-M (a, b) and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes (c, d) in poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA; 1 wt% doped films). a, c Steady-state PL (fluorescence) spectra at 300 K (blue) and 77 K (red) without delay time and phosphorescence spectra at 77 K (green) with a delay time of 25 ms. b, d Transient photoluminescence decay curves at 300 K and their relevant parameters. The red curves represent the single exponential fitting data (background =1).

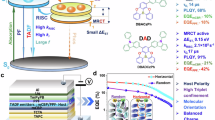

OLED performances

To demonstrate the potential of the developed materials, TADF-based OLED devices were fabricated with the following structure: indium tin oxide (ITO, 50 nm)/ N,N’-di(1-naphthyl)-N,N’-diphenyl-(1,1’-biphenyl)-4,4’-diamine (NPD, 35 nm)/ tris(4-carbazolyl-9-ylphenyl)amine (TCTA, 15 nm)/ 3,3’-di(9H-carbazol-9-yl)-1,1’-biphenyl (mCBP, 15 nm)/ emissive layer (ν-DABNA-M or ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes) and mCBP and DOBNA-Tol13 (20 nm)/ DOBNA-Tol (10 nm)/ 2,7-bis(2,2’-bipyridine-5-yl)triphenylene (BPy-TP257, 20 nm)/ LiF (1 nm)/ Al (100 nm). The chemical structures of the compounds used in device fabrication are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 17. The emitter doping concentration was optimized by fabricating devices with concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 wt%. Among them, the device with 1.0 wt% doping exhibited the best performance. The architecture and EL characteristics of the fabricated TADF-based devices are shown in Fig. 5 and Table 2. The TADF OLEDs based on ν-DABNA-M and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes as emitter exhibited ultra-narrow FWHMs of 16 nm, with the EL emissions peaking at 477 nm (sky-blue) and 467 nm (deep-blue), respectively. Both devices displayed high EQE values of 29.5, 23.7, and 16.5% for ν-DABNA-M and 31.1%, 25.4%, and 18.2% for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes at 10, 100, 1000 cd m−2, respectively. The higher EQE values of ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes are presumably due to the π-conjugation extension, which enhance the molecular orientation to increase the light outcoupling efficiency. According to the analysis of the angle dependence of the PL using codeposition films in mCBP and DOBNA-Tol, the horizontal molecular orientations (Θh) of ν-DABNA-M and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes were determined to be 80.4% and 86.7%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18). The roll-off characteristics of ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes device at 1000 cd m−2 was also improved compared to ν-DABNA-M, which is driven by enhanced PLQY and RISC processes. Notably, the CIE y coordinate for ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes was 0.09, approaching the pure blue NTSC gamut (CIE y, 0.08) and significantly outperforming ν-DABNA-M (CIE y, 0.16). Furthermore, its ultra-narrow FWHM of 16 nm sets an exceptional performance benchmark among deep-blue MR-TADF materials with CIE y ≤ 0.1 (Supplementary Table 7). The LT80 of the ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes-based device was 15 hours at an initial luminance of 100 cd m–2, shorter than that of ν-DABNA-M-based device (67 h). This reduced operational stability is likely due to its blue-shifted emission and higher photo energy (467 nm/2.65 eV vs. 477 nm/2.60 eV), which can accelerate degradation processes.

a Device structure with the estimated energy levels of each component in eV. b Normalized EL spectra of the devices in operation. Inset: Electroluminescence, FWHM and the images of the fabricated devices. c Commission Internationale d’Éclairage (CIE) (x,y) coordinates. d Current density (solid) and luminance (dashed) vs. driving voltage. e Current efficiency (solid) and Power efficiency (dashed) vs. luminance. f External quantum efficiency (EQE) vs. luminance.

To improve the device lifetime, a PSF device was fabricated using PtON-TBBI (13 wt%) as a sensitizer and ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes (1 wt%) as the terminal emitter. The device architecture and performance details are shown in Fig. 6 and Table 2. The chemical structures of the compounds that utilized in the PSF device are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 17. The PSF device exhibited EL spectra identical to the TADF system, delivering ultra-pure deep-blue narrowband emission at 467 nm with an FWHM of 17 nm (96 meV), indicating efficient energy transfer from sensitizer to the terminal emitter due to its high ε (log ε = 5.46, Supplementary Fig. 12). Its turn on voltage (2.5 eV) was significantly lower than that of the TADF device (3.4 eV), reflecting optimal charge transport and injection efficiency. The ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes-based PSF device achieved an EQEmax of 25.6%, maintaining 23.7% at 1000 cd m–2 and 20.2% at 10000 cd m–2, demonstrating exceptional roll-off characteristics with only 7 and 21% decay, respectively. This outstanding stability surpasses that of previous HF or PSF systems using ν-DABNA or its derivatives as emitters (Supplementary Table 8), attributed to the low-lying HOMO level of ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes, which effectively suppresses hole trapping at the emitter. Furthermore, the lifetime of the PSF device was significantly improved, with an LT80 of 16 h at an initial luminance of 1000 cd m–2. Based on this LT80@1000 cd m–2 value (16 h), the LT80@100 cd m–2 was estimated to be 1010 h, calculated with the following equation: LT80@100 cd m–2 = LT80@1000 cd m–2 × (1000 cd m–2 / 100 cd m–2)n, the acceleration factor value for n was assumed to be 1.8 based on the reported PSF devices that ultilized ν-DABNA as the terminal emitter58,59. Such a long lifetime of the PSF device can be attributed to the efficient energy transfer and the stability of the terminal emitter. For comparison, the ν-DABNA-M-based PSF device and the phosphor-only device were also fabricated, and their performance details are shown in Supplementary Fig. 24 and Supplementary Fig. 25.

a Device structure with the estimated energy levels of each component in eV. b Normalized EL spectra of the PSF device in operation. Inset: Electroluminescence, FWHM and the image of the fabricated device. c Commission Internationale d’Éclairage (CIE) (x,y) coordinates. d Current density (solid) and luminance (dashed) vs. driving voltage. e Current efficiency (solid) and Power efficiency (dashed) vs. luminance. f External quantum efficiency (EQE) vs. luminance.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a novel and versatile strategy: the late-stage direct double borylation of B/N-based MR frameworks. This approach effectively extends their fully resonating π-conjugation, leading to increased transition energy, enhanced transition dipole moment, and a smaller S1−T1 energy gap, which are critical factors for narrowband deep-blue OLEDs. To demonstrate its potential, we conducted the direct double borylation of ν-DABNA-M to obtain ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes, which exhibits a deeper blue emission (463 vs. 473 nm), improved PLQY (0.93 vs. 0.92), higher kr (2.57 × 108 s–1 vs. 1.64 × 108 s–1) and kRISC (2.05 × 105 s–1 vs. 1.22 × 105 s–1), while also significantly improving solubility. This proof-of-concept compound, ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes, exhibits excellent TADF characteristics, making it particularly well-suited for narrowband deep-blue OLED applications. The TADF and PSF-based OLED devices were fabricated using ν-DABNA-M-B-Mes as the emitter. Both types of devices demonstrated excellent performance, achieving high external quantum efficiency (EQE), high luminous efficacy, and excellent color purity, approaching NTSC standards. Furthermore, the PSF device exhibited a remarkable low efficiency roll-off and an exceptionally long operational lifetime of LT80 at 100 cd m–2 for over 1000 h, setting a new benchmark for blue OLEDs. This outstanding performance is attributed to the low HOMO energy level of the designed compound, which reduces hole trapping and extends the lifetime in the PSF system, highlighting the effectiveness of our design strategy. Our findings are pivotal for researchers and practitioners seeking innovative solutions to address the challenges associated with color purity and efficiency in OLED technology.

Methods

General Procedure

All the reactions dealing with air- or moisture-sensitive compounds were carried out in a dry reaction vessel (small scale, a Schlenk flask; large scale, a three-neched round bottomed flask) under a positive pressure of nitrogen. Air and moisture sensitive liquids and solutions were transferred via a syringe or a Teflon cannula. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on glass plates coated with 0.25 mm 230–400 mesh silica gel containing a fluorescent indicator (Merck, #1.05715.0009). TLC plates were visualized by exposure to ultraviolet light (254 or 365 nm). Organic solutions were concentrated by rotary evaporation at ca. 10–50 mmHg. Flash column chromatography was performed on Merck silica gel 60 (spherical, neutral, 140–325 mesh) and Kanto Chemical silica gel 60 N (spherical, neutral, 40–50 μm). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR), carbon nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR), and boron nuclear magnetic resonance (11B NMR) spectra were recorded on JEOL ECA500 (495 MHz) NMR spectrometers. Proton chemical shift values are reported in parts per million (ppm, δ scale) downfield from tetramethylsilane and are referenced to the tetramethylsilane (δ 0). 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 125 MHz: carbon chemical shift values are reported in parts per million (ppm, δ scale) downfield from tetramethylsilane, and are referenced to the carbon resonance of tetramethylsilane (δ 0) or CDCl3 (δ 77.0). 11B NMR spectra were recorded at 159 MHz: boron chemical shift values are reported in parts per million (ppm, δ scale) and are referenced to the external standard boron signal of BF3·Et2O (δ 0). Data are presented as: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet and/or multiplet resonances), coupling constant in hertz (Hz), signal area integration in natural numbers, and assignment (italic). IR spectra were recorded on an ATR-FTIR spectrometer (IRAffinity-1S, Shimadzu). Characteristic IR absorptions are reported in cm–1. High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained by the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) method with a JEOL SpiralTOF instrument. The purity of isolated compounds was determined by 1H NMR analyses or HPLC analysis on a JASCO UV-2070 Plus instrument equipped with a reversed-phase C18 column (Mightysil RP-18 GP, Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., 4.6 × 100 mm i.d.).

Materials

Materials were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Wako), Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Aldrich Inc., and other commercial suppliers, and were used after appropriate purification, unless otherwise noted. Florisil (100–200 mesh) was purchased from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. (Kanto).

Solvent

Anhydrous solvents were purchased from above-described suppliers and/or dried over Molecular Sieves 4 A and degassed before use. Water content of the solvent was determined with a Karl Fischer moisture titrator (AQ-2200, Hiranuma Sangyo Co., Ltd.) to be less than 20 ppm.

Synthesis and characterization

The experimental details on synthesis and characterization are presented in the Supplementary Information. The NMR charts are shown in Supplementary Figs. 26–40.

Computational methods

All calculations were performed with Gaussian 16 (Revision B.01), ADF2021 packages unless otherwise noted. The DFT method was employed using the B3LYP or M062X hybrid functional. Structures were optimized with the 6-31G(d) basis set. The time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculation was conducted at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level or the M06-2X/TZP level. Coupled-cluster (CC2) calculations were performed using the TURBOMOLE package with def2-TZVP basis set at the structures optimized at the (TD) M06-2X/TZP level. The RMSDs of the optimized structures at S0 and S1 states were analyzed by VMD software. The Huang-Rhys (HR) factors and simulated spectra were calculated using the MOMAP software.

Measurement of absorption and emission characteristics

UV-visible absorption spectra were measured using a V-560 UV-visible spectrometer (JASCO) at 298 K. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were measured using an F-7000 spectrometer (Hitachi High-Tech) at 77 and 298 K. Furthermore, the absolute PL quantum yields were measured using C9920-02G spectrometers (Hamamatsu Photonics). The PL decays were measured using a C11367 spectrometer (298 K, Hamamatsu Photonics) and were then fitted using a single exponential function to determine the lifetimes of prompt and delayed fluorescence.

Device fabrication and measurement of electroluminescence characteristics

OLEDs were fabricated on glass substrates coated with a patterned transparent ITO conductive layer. The substrates were treated with 300 W oxygen plasma. The pressure during the vacuum evaporation was 5.0 × 10−4 Pa, and the film thickness was controlled using a calibrated quartz crystal microbalance during deposition. After all layers were deposited, the OLED test modules were encapsulated with a capping glass in an evaporation chamber filled with nitrogen. The OLED characteristics of all fabricated devices were evaluated at 298 K in an air atmosphere using a voltage–current–luminance measuring system, comprising a source meter (Keithley 2400) and a spectral radiance meter (Topcon SR-3AR). The EQE was calculated using the EL spectrum, assuming that the light-emitting surface was a perfect diffusion surface; all radiance elements from every angle were added up and inputted into the formula to obtain the EQE.

Data availability

The data supporting the main findings of this work are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information, or available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Uoyama, H., Goushi, K., Shizu, K., Nomura, H. & Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light-emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012).

Zhang, Q. et al. Design of efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for pure blue organic light emitting diodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 14706–14709 (2012).

Zhang, Q. et al. Efficient blue organic light-emitting diodes employing thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Photonics 8, 326–332 (2014).

Im, Y. et al. Molecular design strategy of organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters. Chem. Mater. 29, 1946–1963 (2017).

Yang, Z. et al. Recent advances in organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 915–1016 (2017).

Wong, M. Y. & Zysman-Colman, E. Purely organic thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605444 (2017).

Cai, X. & Su, S.-J. Marching toward highly efficient, pure-blue, and stable thermally activated delayed fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802558 (2018).

Nakanotani, H., Tsuchiya, Y. & Adachi, C. Thermally-activated delayed fluorescence for light-emitting devices. Chem. Lett. 50, 938–948 (2021).

Hatakeyama, T. et al. Ultrapure blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules: efficient HOMO-LUMO separation by the multiple resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 28, 2777–2781 (2016).

Hatakeyama, T. et al. One-shot multiple borylation toward BN-doped nanographenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1195–1198 (2018).

Kondo, Y. et al. Narrowband deep-blue organic light-emitting diode featuring an organoboron-based emitter. Nat. Photonics 13, 678–682 (2019).

Ikeda, N. et al. Solution-processable pure green thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter based on the multiple resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 32, 2004072 (2020).

Oda, S. et al. Carbazole-based DABNA analogues as highly efficient thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials for narrowband organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2882–2886 (2021).

Tanaka, H. et al. Hypsochromic shift of multiple-resonance-induced thermally activated delayed fluorescence by oxygen atom incorporation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17910–17914 (2021).

Oda, S. et al. One-Shot synthesis of expanded heterohelicene exhibiting narrowband thermally activated delayed fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 106–112 (2022).

Oda, S. et al. Development of pure green thermally activated delayed fluorescence material by cyano substitution. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201778 (2022).

Oda, S. et al. Ultra-narrowband blue multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205070 (2023).

Uemura, S. et al. Sequential multiple borylation toward an ultrapure green thermally activated delayed fluorescence material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 1505–1511 (2023).

Sano, Y. et al. One-shot construction of BN-embedded heptadecacene framework exhibiting ultra-narrowband green thermally activated delayed fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11504–11511 (2023).

Ochi, J. et al. Highly efficient multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence material toward a BT.2020 deep-blue emitter. Nat. Commun. 15, 2361 (2024).

Mamada, M. et al. Efficient deep-blue multiple-resonance emitters based on azepine-decorated ν-DABNA for CIEy below 0.06. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402905 (2024).

Hayakawa, M. et al. “Core–Shell” wave function modulation in organic narrowband emitters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18331–18340 (2024).

Liang, X. et al. Peripheral amplification of multi-resonance induced thermally activated delayed fluorescence for highly efficient OLEDs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11316–11320 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-resonance induced thermally activated delayed fluorophores for narrowband green OLEDs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 16912–16917 (2019).

Pershin, A. et al. Highly emissive excitons with reduced exchange energy in thermally activated delayed fluorescent molecules. Nat. Commun. 10, 597 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Constructing charge-transfer excited states based on frontier molecular orbital engineering: narrowband green electroluminescence with high color purity and efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17442–17446 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Achieving pure green electroluminescence with CIEy of 0.69 and EQE of 28.2% from an aza-fused multi-resonance emitter. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17499–17503 (2020).

Nagata, M. et al. Fused-nonacyclic multi-resonance delayed fluorescence emitter based on ladder-thiaborin exhibiting narrowband sky-blue emission with accelerated reverse intersystem crossing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20280–20285 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Multi-resonance deep-red emitters with shallow potential-energy surfaces to surpass energy-gap law. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 20498–20503 (2021).

Cheon, H. J., Woo, S. J., Baek, S. H., Lee, J. H. & Kim, Y. H. Dense local triplet states and steric shielding of a multi-resonance TADF emitter enable high-performance deep-blue OLEDs. Adv. Mater. 34, 2207416 (2022).

Park, I. S., Min, H. & Yasuda, T. Ultrafast triplet–singlet exciton interconversion in narrowband blue organoboron emitters doped with heavy chalcogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205684 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Narrowband emissive TADF conjugated polymers towards highly efficient solution-processible OLEDs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211172 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. A highly twisted carbazole-fused DABNA derivative as an orange-red TADF emitter for OLEDs with nearly 40 % EQE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202212575 (2022).

Naveen, K. R., Yang, H. I. & Kwon, J. H. Double boron-embedded multiresonant thermally activated delayed fluorescent materials for organic light-emitting diodes. Commun. Chem. 5, 149 (2022).

Cai, X., Pu, Y., Li, C., Wang, Z. & Wang, Y. Multi-resonance building-block-based electroluminescent material: lengthening emission maximum and shortening delayed fluorescence lifetime. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304104 (2023).

Mubarok, H. et al. Triptycene-fused sterically shielded multi-resonance TADF emitter enables high-efficiency deep blue OLEDs with reduced dexter energy transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202306879 (2023).

Suresh, S. M. et al. A deep-blue-emitting heteroatom-doped MR-TADF nonacene for high-performance organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215522 (2023).

Jin, J. et al. Integrating asymmetric O−B−N unit in multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters towards high-performance deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218947 (2023).

Suresh, S. M., Hall, D., Beljonne, D., Olivier, Y. & Zysman-Colman, E. Multiresonant thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters based on heteroatom-doped nanographenes: recent advances and prospects for organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908677 (2020).

Kim, H. J. & Yasuda, T. Narrowband emissive thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2201714 (2022).

Naveen, K. R., Palanisamy, P., Chae, M. Y. & Kwon, J. H. Multiresonant TADF materials: triggering the reverse intersystem crossing to alleviate the efficiency roll-off in OLEDs. Chem. Commun. 59, 3685–3702 (2023).

Jiang, H., Jin, J. & Wong, W. Y. High-performance multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters for narrowband organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2306880 (2023).

Mamada, M., Hayakawa, M., Ochi, J. & Hatakeyama, T. Organoboron-based multiple-resonance emitters: synthesis, structure–property correlations, and prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 1624–1692 (2024).

Fan, T., Zhang, Y., Zhang, D. & Duan, L. Decoration strategy in para boron position: an effective way to achieve ideal multi-resonance emitters. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202104624 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Frontier molecular orbital engineering: constructing highly efficient narrowband organic electroluminescent materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312451 (2023).

Park, I. S., Yang, M., Shibata, H., Amanokura, N. & Yasuda, T. Achieving ultimate narrowband and ultrapure blue organic light-emitting diodes based on polycyclo-heteraborin multi-resonance delayed-fluorescence emitters. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107951 (2022).

Naveen, K. R. et al. Deep blue diboron embedded multi-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters for narrowband organic light emitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 432, 134381 (2022).

Chan, C. Y. et al. Stable pure-blue hyperfluorescence organic light-emitting diodes with high-efficiency and narrow emission. Nat. Photon. 15, 203–207 (2021).

Jeon, S. O. et al. High-efficiency, long-lifetime deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Photon. 15, 208–215 (2021).

Zhang, K. et al. Carbazole-decorated organoboron emitters with low-lying HOMO levels for solution-processed narrowband blue hyperfluorescence OLED devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313084 (2023).

Kim, E. et al. Highly efficient and stable deep-blue organic light-emitting diode using phosphor-sensitized thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq1641 (2022).

Zhang, K., Wang, X., Wang, M., Wang, S. & Wang, L. Solution-processed blue narrowband OLED devices with external quantum efficiency beyond 35% through horizontal dipole orientation induced by electrostatic interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202423812 (2025).

Wu, L. et al. Orienting group directed cascade borylation for efficient one-shot synthesis of 1,4-BN-doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as narrowband organic emitters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402020 (2024).

Guek, S. J. K., Ji, L., Loke, J. W. L., Koh, H. L. & Fan, W. Y. Nickel(II) phosphine-catalysed hydrodehalogenation of aryl halides under mild ambient conditions. Mol. Catal. 524, 112310 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Anthraquinone-based intramolecular charge-transfer compounds: computational molecular design, thermally activated delayed fluorescence, and highly efficient red electroluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 18070–18081 (2014).

Kaji, H. et al. Purely organic electroluminescent material realizing 100% conversion from electricity to light. Nat. Commun. 6, 8476 (2015).

Togashi, K., Nomura, S., Yokoyama, N., Yasuda, T. & Adachi, C. Low driving voltage characteristics of triphenylene derivatives as electron transport materials in organic light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 20689 (2012).

Wu, C. et al. New [3+2+1] iridium complexes as effective phosphorescent sensitizers for efficient narrowband saturated–blue hyper–OLEDs. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301112 (2023).

Chung, W. J. et al. Over 30 000 h Device Lifetime in Deep Blue Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with y Color Coordinate of 0.086 and Current Efficiency of 37.0 cd A−1. Adv. Opt. Mater. 9, 2100203 (2021).

Acknowledgements

T.H. acknowledge Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST (grant no. JPMJCR22B3), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (ILR) (grant no. 23K20039), the Core-to-Core Program (grant no. JPJSCCA20220004), and the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant no. 24K01569).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. conceived and supervised the project. J.H. performed the synthesis and characterization. K.T. supported the borylation reaction. J.H. and Y.K. performed the photophysical measurements. J.H., J.O., and M.K. performed the computational calculations. Y.K. fabricated the OLED devices. J.H. wrote the manuscript. T.H., M.M., J.O., and K.R.N. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hao, J., Ochi, J., Tanaka, K. et al. Late-stage direct double borylation of B/N-based multi-resonance framework enables high-performance ultra-narrowband deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes. Nat Commun 16, 8867 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63908-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63908-y