Abstract

Traditional metal alloys require energy-intensive processes to manage atomic complexity for improved strength and toughness, with stringent control over impurities and processing conditions. High-/medium-entropy alloys (HEAs/MEAs) offer a sustainable alternative by introducing atomic complexity with fewer constraints, enabling unique phase transitions. Here, a Cu–Au–Ag MEA is fabricated using vacuum suspension melting followed by heat treatment. The alloy exhibits three distinct levels of heterogeneous structures: micron-scale phase separation, nano-ordered L12 phase, and chemical short-range order (CSRO). It demonstrates tensile and compressive strengths of 550 MPa and 1700 MPa for the micropillar sample, respectively, with 25% tensile elongation and over 50% compressive strain. The large-scale sample achieves a tensile strength and elongation of about 500 MPa and 40%, respectively. Compared to traditional gold, silver, and copper alloys, both the strength and plasticity are enhanced. The microstructural characteristics and corresponding mechanical properties are found to match the experimental structure through high-temperature ternary alloy phase diagrams and simulations. This work introduces a alloy design approach that leverages atomic affinity manipulation to regulate multilayer heterogeneous structures, which offers an efficient pathway for designing MEAs suitable for demanding high-performance electronic packaging applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The strength and toughness trade-off reaches a harmony in ancient Damascus steel enabled by the woven hard and soft layers1,2. The superior mechanical properties originally result from repeatedly folding and forging by skilled blacksmiths, leading to the carbon redistribution and work hardening in macrocomposites3,4. Such time-consuming and costly mechanical post-processes challenge todays’ idea of green production and sustainability, and are hard to apply new techniques like one step synthesis5, 3D printing6,7, and plainification of materials8.

Recently, high-entropy alloys (HEAs) offer a new avenue in the development of metals and alloys, the vast compositional space facilitates the direct modulation of materials’ mechanical, chemical, or even functional properties9,10,11. The entropy concept is now way beyond the single-phase domain, evolving to incorporate a colorful phase variety. For example, the dual-phase HEAs, such as the non-equiatomic Fe80-xMnxCo10Cr10 (at%) system has both face centered cubic (FCC) and hexagonal closely packed (HCP) phases, which realize the transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) and achieve a much higher ductility without sacrificing the ultimate strength12. On the other hand, the appearance of a second phase, like unusual soft L12 phase in (FeCoNi)86-Al7Ti7, provides the similar hard-soft weaving effect, and reaches an excellent balance of strength and ductility13. Besides the obvious compositional and phase space, the chemical short-range order (CSRO) is getting more attention recently14,15,16. The phases in HEAs, either solid solutions or intermetallics, are all within a wide homogeneous range, displaying a multicomponent nature17,18. The CSRO will fine tune the lattice to promote local phase change19, diffuse anti-phase boundary20,21, severe lattice distortion22,23, etc., which results in extra solid-solution hardening. From atomic to microstructural scale, the HEAs possess advantages in providing soft-hard domains after very simple fabrication, like casting. It poses the question of whether all those effects could be preserved in one HEA alloy or if there is a rational design that covers all those effects.

The nature of all the above phases and CSRO variations lies in the disorder-order transition associated with the high-to-low entropy as a function of temperature24,25. In this endeavor, the binary Ag-Cu system has been studied for coinage for thousands of years, while Cu-Au and Cu-Au-Ag systems have been models for more than half a century, becoming the cornerstone and foundation of meta-stable thermodynamics26,27,28. Moreover, Cu-Au-Ag alloys hold considerable promise in electronic packaging applications, such as 3D integrated circuits (ICs)29,30, solar cell metallization31,32,33, and electrical contact materials34,35, where the demand for reliable, energy-efficient, and high-performance materials is critical. In this study, the equiatomic CuAuAg medium entropy alloy (MEA) was prepared under the guidance of meta-stable thermodynamics driven by the cluster variation method (CVM)36. After simple arc-melting and one-time annealing, the multi-heterogeneous structure including phase separation, intermetallic nanoprecipitation, and CSRO was obtained simultaneously. A synergy of elevated strength and ductility in mechanical performance is achieved in the CuAuAg MEA. Such strength and toughness are critical for ensuring the reliability of miniaturized packaging, as they help to better withstand external forces or thermal expansion effects, prevent mechanical fatigue failure, and reduce the risk of brittle fracture. Therefore, the rationale of microstructure modulation not only provides insights into the fundamental science of HEAs and MEAs but also enables the development of electronic packaging materials exhibiting good combinations of strength and ductility.

Results

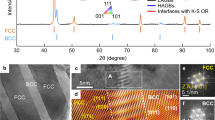

Damascus-style dual-phase structure

The practical-to-ideal configurational entropy ratio and ternary meta-stable phase diagram constructed by first-principle corrected CVM (Fig. 1a) show that a miscibility gap pops out from the Au–Cu region at 650 °C, complying with the experimental and other theoretical observations in the literature37,38,39. This means the equiatomic CuAuAg MEA will experience phase decomposition along the miscibility gap (corresponding meta-stable phase diagrams are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Fig. 1b) indicate the decomposed Cu-rich and Ag-rich FCC solid-solution phases. These structures correspond to Powder Diffraction File (PDF) numbers 01-074-7033 (yellow label in Fig. 1b) and 04-010-7444 (blue label in Fig. 1b), respectively, from the PDF-5+ dataset40. Based on the quantitative analysis of XRD peaks and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2), the actual compositions of Cu-rich and Ag-rich are close to Cu60Au33Ag7 (near 48.5% area) and Cu10Au35Ag55 (near 51.5% area), respectively. The nonsymmetric phase separation along the miscibility gap suggests the non-equal atomic interactions. As can be seen in Fig. 1a, the Cu-rich phase (blue star) is located near the miscibility gap, while the Ag-rich phase (pink star) is located on the opposite side of the lever formed by the equiatomic phase (yellow triangle) and the Cu-rich phase. The Ag-rich phase exhibits a slight deviation.

a Practical-to-ideal ratio of configuration entropy of CuAuAg alloy at 650 °C. b XRD pattern indicating a two-phase Cu-rich and Ag-rich structure, corresponding to PDF cards No. 01-074-7033 and No. 04-010-7444, respectively. c Optical microscopy image of CuAuAg alloy with Damascus-like pattern. d HAADF image of CuAuAg alloy. e–g Chemical mapping of Cu, Au and Ag, the scale bars in (e–g) are identical to that in (d).

The optical microscopy (Fig. 1c) shows a typical two-phase feature with black and white stripes. These stripes exhibit two distinct interactive sizes, which result from elemental segregation during the separation of the Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases, leading to variations in stripe sizes. However, the composition and crystal structure of those stripes, regardless of size, remain the same. Interestingly, this striped pattern resembles that of classic Damascus steel. The zebra stripes range from nanoscale to macroscale, insinuating the difference of our CuAuAg MEA from traditional Damascus steel3,4. The sample for transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis was taken from a region of representative, medium-sized grains in Fig. 1c. The TEM imaging (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3a–b) and elemental mapping (Fig. 1e–g and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b) confirm the Damascus striped pattern at sub-microscale. The elemental distribution is divided into Cu (green region in Fig. 1e) and Ag (blue region in Fig. 1g) regions, while the Au (yellow region in Fig. 1f) is less pronounced with a slight preference for the Cu-rich region. At a smaller scale, we found there are equally spaced cataphracted stripes inside the Cu-rich area, indicating a hierarchical structure from macro to nano scale.

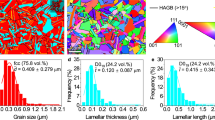

Nanolamellar heterogeneous structure

To understand the fish-scale nanolamellar structure in Fig. 1d, CVM calculation is performed at a lower temperature. A typical example of the ternary CuAuAg phase diagram as well as the practical-to-ideal configurational entropy ratio is shown in Fig. 2a. Two ordered phases39,41, L10 CuAu and L12 Cu3Au appear in Fig. 2a with a sharp drop in the entropy. In order to unravel the crystal structure of the striped phase, high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) is utilized, and the overall morphology is shown in Fig. 2b. Those fish-scale stripes are embedded in the Cu-rich matrix and do not show a clear boundary with the matrix (Fig. 2c). The atomic imaging of one strip (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3c) displays strong contrast between the strip and the Cu-rich matrix. Nevertheless, the atomic fringe is coherent across the strip. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) shows two different crystal structures, FCC and L12 for the matrix and strip, respectively. This confirms the strip is L12 which precipitates from the Cu-rich matrix.

a Practical-to-ideal ratio of configuration entropy of CuAuAg alloy at 350 °C. b Precipitation in Cu-rich region. c HAADF image of striped phase. d HAADF image of FCC and L12 phase. Inset: FFT pattern. e HR-HAADF image of interface between FCC and L12 phase. f Element distribution in the line scanning. g–i Chemical mapping of Cu, Ag and Au.

Figure 2e shows the high-resolution HAADF (HR-HAADF) image of the coherent FCC-L12 interface. A linear scan and mapping are performed across the interface in Fig. 2f. The upper zone could be identified as L12 intermetallics with a composition near Cu75Au20Ag5, while the lower zone is an FCC solid solution with a composition of Cu50Au20Ag30. The elemental mapping shows a clearer separation of Au and Ag in the Cu-rich matrix (Fig. 2g–i). The L12 is almost dominated by Cu3Au, while the FCC is CuAg-rich. Together with the phase diagram and HAADF-STEM image, the precipitation of L12 Cu3Au could be affirmed in the cooling process. It is also noteworthy that Au and Cu signals in the FCC solid solution are scattered and display some clustering inclination.

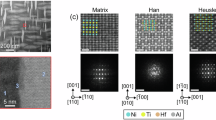

Chemical short-range order

The clustering feature has been confirmed by the HR-HAADF image of the FCC Cu-rich region (Fig. 3a), together with the inverse FFT image (Fig. 3b) of the extra spot of the original FFT pattern (inset of Fig. 3a). Even though the atomic arrangement is even, there is extra an FFT spot inside the perfect FCC [110] zone axis. The inverse FFT confirms that these spots correspond to the CSRO region (highlighted by yellow circles), where the lattice spacing of the CSRO structure is approximately twice that of the FCC matrix, as shown in Fig. 3b. This demonstrates a typical L12-type superlattice in the CSRO structure.

a HR-HAADF image of the Cu-rich region with the [110] zone axis and the corresponding FFT pattern (inset). b Inverse FFT image showing the CSRO regions, which exhibit a lattice spacing approximately twice that of the perfect FCC lattice. c Atomic mapping of L12 region in CuAuAg MEA Cu-rich phase. d Pair probabilities and CSRO parameters correspond to the first nearest neighbors calculated by CVM, percentages of Cu and Au and Ag are 0.73, 0.21 and 0.06, respectively. e–g Atomic resolution mapping of Cu-Au pair, Cu-Ag pair, and Au-Ag pair in L12 region of Cu-rich phase, the scale bars in (e–g) are identical. h 3DAP images of Cu, Au, Ag elements. i Element distribution of 3DAP near the phase boundary between Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases. j Component fluctuations in Cu-rich phase represents a signature of L12 strips, the specific iso-concentration surfaces are defined at 60 at%.

To dig into the atomic interaction in L12 superlattice, atomic mapping of an L12 region of the Cu-rich phase is plotted in Fig. 3c. Various colors, like purple, orange, cyan, pink, etc., result from the overlap of original yellow (Cu), blue (Ag), and red (Au), suggesting the existence of strong CSRO. As a result, CVM is used to determine the CSRO and pair probability of L12 superlattice in Cu-rich phases42,43. The pair probability in the upper panel of Fig. 3d indicates that the Cu-Au atomic pair is likely to segregate with a pair probability an order of magnitude higher than those of Cu-Ag and Au-Ag. The CSRO (corresponding to the first nearest neighbors) confirms this Cu-Au affinity, but also suggests strong attractive interactions between Au and Ag. Cu-Ag on the other hand, is unlikely to form CSRO structures. The atomic resolution mapping of Cu, Au, and Ag elements supports our pair probability and CSRO from CVM. Figure 3e–g shows the strong interaction in Cu-Au pairs and some interaction in Au-Ag pairs, while weak interaction in the Cu-Ag pair, which is demonstrated by the mixed color of each element.

The three-dimensional atom probe (3DAP) images in Fig. 3h further provide a spatial representation of the Cu, Au, Ag and mixed distributions. The observed compositional gradients reflect the coexistence of Cu-rich and Ag-rich regions, offering strong evidence of the phase-segregated nature of the annealed alloy (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). The elemental distribution obtained via 3DAP near the phase boundary between the Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases (the cylinder area in the bottom right of Fig. 3h) reveals a gradual transition in Cu and Ag composition in Fig. 3i, confirming the phase segregation predicted and observed in Fig. 1. We take a close look at the Cu-rich region and notice a few gray strips (Fig. 3j). The Cu:Au compositional fluctuations around those strips (black dotted rectangle) are near 0.75:0.25 = 3:1, indicating the L12 ordered phase. The length of this area is around 5 nm, almost identical to the width of the L12 strip in Fig. 2d. This further supports the hierarchy of phase segregation and nano-precipitation. Supplementary Movie 1, 2, and 3 provide a 3D animation of fault-like element distribution in Cu and Ag but a nearly uniform distribution in Au.

Mechanical performance

The mechanical properties were estimated by the elastic moduli of CuAuAg MEA. The Young’s modulus and hardness are shown in Fig. 4a, b, respectively. The Cu-rich phases, either solid solution or L12 structure, have a higher modulus and hardness than the Ag-rich phases. The practical-to-ideal ratio suggests the L12 ordering and corresponding CSRO increase the mechanical strength of the L12 over the FCC counterpart (more elastic properties are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). The detailed pair probability and CSRO parameters are shown in Fig. 4c, d for Cu-rich FCC and L12 phases, respectively. As the L12 phase has a composition close to Cu75Au20Ag5, except for the highest probability of the Cu-Cu pair, the Cu-Au pair is also significant, and the probability of the remaining pairs is nearly zero. Conversely, the Cu-Cu, Ag-Ag, Cu-Au, Cu-Ag, and Au-Ag pairs are present in the FCC solid solution, while the Au-Au pair remains at a negligible level. CSRO in Fig. 4d reveals the important role of Au-Au interaction in both FCC and L12 phases, indicated by the large negative value. This indicates that a pair with a notably low probability may exhibit robust interactions. Ag-Ag interactions have a negligible effect on the CSRO of the L12 phase. From Fig. 4, we can see the higher Young’s modulus and hardness of L12 over FCC phases is mainly contributed from the Ag-Ag and Cu-Au interactions.

a Practical-to-ideal ratio of Young’s modulus, b distribution of hardness, c pair probability and (d) CSRO parameters of FCC and L12 in the Cu-rich phase, composition of L12 configuration is set to Cu75Au20Ag5, and FCC configuration is set to Cu50Au20Ag30. The values presented are deterministic results from a single, converged CVM simulations for each structure type. Each bar represents a unique, calculated physical quantity (pair probability or CSRO parameter) for a specific atomic pair within that simulated equilibrium state.

The room-temperature tensile and compressive properties of the CuAuAg MEA were investigated (Fig. 5a) to validate the effect of those heterogeneous structures and CSRO strengthening on the mechanical performance. Figure 5a shows the room-temperature tensile and compressive strength of the CuAuAg MEA micropillar and large-scale samples (4 mm × 5 mm). It reaches ~550 MPa and 1700 MPa for tensile and compressive strength for micropillars, respectively. The corresponding elongation after tensile deformation is about 25%, while the compressive strain exceeds 50% (more specimen test results are demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 5). The large-scale tensile sample shows a strength of about 500 MPa and a elongation of nearly 40%. As shown in Fig. 5b, the tensile strength and elongation are better than those of worked and heat-treated unary, binary, and ternary counterparts44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Among those experimental results in the literature, there is a Au27.9Ag20.3Cu51.8 alloy54 which has a higher Cu concentration and more L12 precipitates after a series of processes including cold working, drawing, aging and quenching, and displays lower strength and toughness (purple pentagons) in comparison to our CuAuAg MEA (red stars). Our mechanical properties (appearing in the upper right corner in Fig. 5b) insinuate a balanced strength and toughness, especially for the large-scale sample.

a Strain-Stress curves of CuAuAg alloy. b Tensile mechanical performance of the CuAuAg MEA compared to related materials44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54. The error bars of large-scale specimens indicate the mean ± standard deviation, calculated from four samples of the same size. c In situ tensile testing images with different strain, (i) 0% strain, (ii) 10% strain, (i) 20% strain, (iv) 25% strain. d TEM analysis of the deformed structure in CuAuAg MEA, (i) TEM images and elemental mapping showing coordinated deformation of Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases, (ii) Interaction of dislocations with the L12 structure, (iii) The L12 phase exists mainly at the boundary between the Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases, and there is an obvious difference in dislocation density between the Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases, (iv) Dislocation enrichment is near the L12 superstructure.

The slip bands during the in situ tensile tests are shown in Fig. 5c, respectively (more specimen images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6). During tensile deformation, slip bands on the critical resolved shear stress (CRSS) (45° with respect to the tensile direction) plane immediately appear where the sample is hooked into the mount. After reaching 20% strain, more and more slip bands emerge, some are deviated from the CRSS plane, displaying a typical ductile deformation behavior. The cross-section reduces, and a crack generates after 25%. Furthermore, the microstructure of the deformed large-scale sample is presented in Fig. 5d. As seen in Fig. 5d(i), the TEM and chemical mapping images reveal that the alloy microstructure has elongated in the direction of the applied force, forming a lamellar structure. Figure 5d(ii) and Fig. 5d(iv) show a significant accumulation of dislocations near the L12 phase within the Cu-rich region, impeding dislocation movement and enhancing the alloy’s strength. Additionally, the TEM images and elemental mapping in Fig. 5d(iii) show that the L12 phase in the deformed microstructure is positioned at the boundaries between the Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases.

Discussion

Based on the above results, we now outline three critical points that provide insights into the HEAs/MEAs design and optimization. Firstly, practical entropy plays a key role in the HEAs/MEAs phase stability and microstructure. It is known that single-phase HEAs/MEAs is in a metastable state which will be broken at lower temperature heat fluctuations55,56,57. Three types of phase decomposition could appear at lower temperatures, multiple solid solutions, spinodal decomposition, and intermetallic precipitation12,58,59,60. In our CuAuAg MEA, all three phenomena occur, which differs from the well-known phase relationship in binary Cu-Au and Cu-Ag61,62. The sequence and relationships between them are predicted by first-principles based CVM, as shown in Figs. 1a and 2a. The practical entropy, representing the advantage of CVM, could describe the metastable phase relationship, such as spinodal decomposition into Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases (Fig. 1a) at an annealing temperature of 650 °C. When cooling down, a disorder-order transition appears on the Cu-rich side, while the miscibility gap enables more Au to enter the Ag-rich solid solution (Fig. 2a). Thus, as shown in the middle of the schematical plot in Fig. 6, the CuAuAg MEA evolves into a macro-nano scale hierarchical structure during cooling.

The CuAuAg MEA exhibits a four-tiered structural hierarchy that mirrors the length-complexity scaling with Damascus-like, multiple-layer, heterogeneous microstructures: at the macroscale (20-100 µm), alternating Cu-rich and Ag-rich lamellae assemble into a linear composite reminiscent of Damascus patterning; at the mesoscale (100 nm-1 µm), phase separation produces an interwoven soft-hard morphology; at the nanoscale (5–20 nm), ordered L12 intermetallic precipitates introduce nonlinear strengthening; and at the atomic/picometer scale (1–10 Å), CSRO within both the FCC matrix and L12 precipitates yields exponential complexity. Together, these hierarchical features produce a layered microstructure with intricate phase distributions and synergistic hardening mechanisms, imparting the CuAuAg MEA with balanced strength and ductility.

Secondly, the multiscale hierarchical structures introduce colorful strengthening and toughening mechanisms and lead to better overall performance. The macroscopic Damascus-like Cu-rich and Ag-rich region weaving provides a linear composite effect (Fig. 6). The elemental mapping (Fig. 5d(i)) confirms that the hard Cu-rich phase and the soft Ag-rich phase are intertwined, indicating that these two phases can deform in a coordinated manner. This linear effect can be described by the following equations, which represents the relationship between the mechanical properties of composite materials’ components63,64:

where P represents the properties, such as tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and hardness, etc. P1, V1, P2 and V2 are the property and volume of components 1 and 2, respectively. The linear composite effect enables the hardness of CuAuAg equiatomic MEA, composed of Cu-rich and Ag-rich phases, to be attained within the range of 4.06 to 4.25 GPa. The concurrent presence of a hard Cu layer and a soft Ag layer results in a synergistic improvement in both strength and ductility, attributable to the random distribution of the two regions in a linear combination. As shown in Fig. 5d(iii), the dislocation density in the Cu-rich phase is higher than in the Ag-rich phase, indicating that the Cu-rich phase contributes more to strengthening the alloy, while the Ag-rich counterpart primarily enhances toughness. The quite distinct dislocation densities in the Damascus-like Cu-rich and Ag-rich regions suggest the strain across the stripes is not the same, while the stress is. This indicates the strengthening and toughening originate more from the Reuss model63,64.

Besides, the nano-scale intermetallic compound (L12 superlattice, as illustrated in Fig. 2b-d) introduces a nonlinear interaction in the CuAuAg MEA (Fig. 6). This leads to an enhanced resistance to dislocation movement, as dislocations are diverted around the L12 nanolamellar structure. The strengthening mechanisms in this system can be explained within the framework of the Hall-Petch relationship, which has been well-established in dual-phase nanolamellar materials65,66,67. Specifically, the strengthening contributed by the boundaries between the L12 phase and the FCC matrix can be expressed by the equation:

where k denotes the Hall-Petch coefficient, and L represents the spacing between nanolamellae. The Hall-Petch coefficient \({{\rm{k}}}\) can be computed using the formula:

where n is the number of dislocations crossing a lamella, which, based on our TEM statistical analysis of deformed samples (Fig. 5d), is ~n ~ 0.5. Additionally, the shear modulus G = 37.36 GPa, the magnitude of Burgers vector, |b | , is 2.774 × 10−10 m, and the average lamellar thickness L = 5 nm were considered in the calculation. With these parameters, we estimate that the strengthening contribution from the nanolamellar boundaries is ~130 MPa, suggesting that the nanolamellar boundaries play a key role in enhancing the macroscopic strength of the material. Additionally, the results from the deformed samples demonstrate that the nanolamellar L12 phase significantly hinders dislocation movement (Fig. 5d(ii–iv)), as a result of the notably higher dislocation density around the L12 phase compared to other regions of the alloy.

Thirdly, a more complicated strengthening effect (Fig. 6), the CSRO, was observed in the nano and pico-scale in both FCC matrix and L12 compound. In the Cu-rich region with FCC lattice, the CSRO was observed with an additional spot in the FFT pattern (Fig. 3a, b). The short-range ordering, derived from the intrinsic interaction behavior of atoms, facilitates additional solid solution strengthening and improves the toughness of alloys15,68,69. The strain field, which is generated by the multitude of CSRO regions, will enhance the likelihood of geometrically necessary dislocations interacting with one another, thereby inducing a hetero-deformation induced hardening70,71. This effect could be attributed to the increased resistance to dislocation slip due to the disruption of favorable atomic bonds72,73. The hardening is thus linked to the dissipation of energy due to the disruption of atomic correlations, with the energy expended in this process being proportional to the degree of dislocation glide. Accordingly, this can be quantitatively characterized by the antiphase boundary (APB) energy EAPB, and the corresponding increase in the CRSS, which is expressed as follows69,74:

In the CuAuAg MEA, the EAPB for the Cu-rich region (Cu50Au20Ag30) of the (110) type APB can be determined through CVM75,76,77,78. The calculated EAPB is 1.87 meV with a lattice parameter a = 0.3887 nm. Utilizing these values, the increase in CRSS \({\triangle \tau }_{{{\rm{CRSS}}}}\) is 36.74 MPa. This suggests that the occurrence of CSRO phenomena also has an impact on the strengthening of CuAuAg MEA. In addition, it is noteworthy that the phenomenon of CSRO can also manifest in the L12 phase outside the solid solution (Fig. 3c–g). The attractive interaction between Cu and Au with strong bonding can also result in the reinforcement of alloys. Therefore, the dilemma of the trade-off between strength and ductility can be overcome in the model CuAuAg MEA (Fig. 5a–b) through multiple strengthening mechanisms, spanning from the macroscale Damascus-like composite to the pico-scale CSRO strengthening.

As a result, in our CuAuAg alloy system, the interactions between Cu, Au, and Ag lead to the formation of a layered microstructure with a complex phase distribution (Fig. 6). The phase separation between these elements results in distinct macroscopic variations, which contribute to the optimization of the material’s strength and toughness, while promoting interphase strengthening across multiple scales. The differences in solubility and element affinities, particularly between Au and Ag, facilitate the formation of fine precipitates and atomic-scale CSRO. These microstructural features synergistically enhance the alloy’s durability and phase stability, providing a robust foundation for its performance in various applications.

In conclusion, the multi-scale hierarchical HEA design approach presented here offers a transformative strategy for overcoming the trade-off between strength and toughness in structural materials. In the model CuAuAg MEA, a range of hierarchical structures are presented, spanning from pico-scale CSRO, nano precipitation, micro phase separation, to macro-scale Damascus-like patterns. These features synergistically enhance mechanical performance by incorporating diverse strengthening mechanisms, including composite effects, precipitation hardening, and CSRO strengthening. This is accomplished through a straightforward process that is both economical and environmentally sustainable, making it suitable for a wide range of HEAs and large-scale industrial production. The findings elucidate the role of entropy-driven phase decomposition, chemical short-range ordering, and multiscale structural evolution. They also support the design of electronic packaging materials that offer a balance of strength and ductility for demanding applications.

Methods

Experiment

Gold ingots (20 g; 99.99%), silver ingots (10.96 g; 99.99%) and copper nuggets (6.45 g; 99.99%) were purchased from Beijing Ryubon Materials Technology Co., Ltd. and melted at least 5 times via vacuum arc melting. After the melting process, the alloy ingots were subjected to a 24 h homogenization treatment at 650 °C. Thin slices were then cut from the alloy ingots and polished on both sides before ion beam cutting. Thereafter, ultrathin and nano-pillar samples were prepared using the Helios NanoLab 600i focused ion beam-scanning electron microscope operating at 30 kV. Phase identification and compositional analysis were conducted via using Bruker Advance D8 X-ray diffraction with a Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) under a scan speed of 5˚/min and Talos F200X transmission electron microscopy operating at 200 kV. In addition, in situ stretching experiments were performed on the samples, and micron-sized columns were fabricated using the Helios 5UC focused ion beam-scanning electron microscope. Micro-scale tensile samples and micropillar samples with varying diameters were also created on the polished sample surface, and their mechanical properties were tested using the FT-NMT04 Nano-mechanical test system. Mechanical properties of large-scale samples were assessed using a PicoFemto-SEP on dog-bone shaped specimens (5 mm length × 4 mm width × 1 mm thickness). The three-dimensional element concentration distribution was analysed from the 3D atom probe CAMECA LEAP5000XR. The atomic structures were characterized by the advanced spherical aberration-corrected transmission electron microscope Spectra 300S/TEM, which was operated at 300 kV.

Cluster variation method

The meta-stable phase diagrams, CSROs and pair probabilities of the Cu–Au–Ag system were calculated using CVM36. The CSRO parameters utilize the same expression as Warren-Cowley short-range order parameters αij79,80, and are defined as follows:

where the yij denotes the pair probability of i and j elements pair, and xi represents the point probability of the i element. In the CVM calculation, a regular tetrahedron of an FCC lattice81 (Supplementary Fig. 7e) and the natural iteration method82 were employed. The formalism of the CVM is presented in Supplementary Note 2, and further details of the CVM derivations can be found in a study conducted by Kikuchi36,83,84. The energy interaction parameters used in the CVM calculation followed the detailed derivations of the study by Schön85, the interaction energy parameters are presented in Supplementary Fig. 7e.

First principles calculation

The energies and elastic moduli (presented in Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Note 3, and Supplementary Table 1) of the Cu–Au–Ag system were calculated using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) version 6.3.286,87. This computational approach is based on the principles of density functional theory (DFT), which involves the iterative solution of Kohn–Sham equations. In these calculations, the projected augmented wave (PAW) method88 was employed in conjunction with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional89. The Monkhorst and Pack method for cubic crystal systems was adopted for k-point meshing90. A 13 × 13 × 13 mesh was selected after convergence tests. The calculations were performed with an energy cut-off of 520 eV, an energy convergence criterion of 10⁻⁶ eV and a force convergence criterion of 0.01 eV/Å. In the calculations, spin polarization was considered with ISPIN = 2 and the default magnetic configurations were utilized.

Data availability

The primary data generated in this study, underpinning all reported findings, are included in the Supplementary Information and Source Data files, additional datasets are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All simulations were executed using commercial software VASP version 6.3.2. The codes used to calculate the CSRO parameters and configuration entropy in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Wadsworth, J. & Sherby, O. D. On the bulat—damascus steels revisited. Prog. Mater. Sci. 25, 35–68 (1980).

Kürnsteiner, P. et al. High-strength damascus steel by additive manufacturing. Nature 582, 515–519 (2020).

Verhoeven, J. D. Genuine damascus steel: a type of banded microstructure in hypereutectoid steels. Steel Res 73, 356–365 (2002).

Peterson, D. T., Baker, H. H. & Verhoeven, J. D. Damascus steel, characterization of one Damascus steel sword. Mater. Charact. 24, 355–374 (1990).

Wei, S., Ma, Y. & Raabe, D. One step from oxides to sustainable bulk alloys. Nature 633, 816–822 (2024).

Qu, Z. et al. High fatigue resistance in a titanium alloy via near-void-free 3D printing. Nature 626, 999–1004 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Ultrauniform, strong, and ductile 3D-printed titanium alloy through bifunctional alloy design. Science 383, 639–645 (2024).

Li, X. & Lu, K. Improving sustainability with simpler alloys. Science 364, 733–734 (2019).

Han, L. et al. Multifunctional high-entropy materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 846–865 (2024).

Han, L. et al. A mechanically strong and ductile soft magnet with extremely low coercivity. Nature 608, 310–316 (2022).

Cao, G. et al. Liquid metal for high-entropy alloy nanoparticles synthesis. Nature 619, 73–77 (2023).

Li, Z., Pradeep, K. G., Deng, Y., Raabe, D. & Tasan, C. C. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength–ductility trade-off. Nature 534, 227–230 (2016).

Yang, T. et al. Multicomponent intermetallic nanoparticles and superb mechanical behaviors of complex alloys. Science 362, 933–937 (2018).

Moniri, S. et al. Three-dimensional atomic structure and local chemical order of medium- and high-entropy nanoalloys. Nature 624, 564–569 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Direct observation of chemical short-range order in a medium-entropy alloy. Nature 592, 712–716 (2021).

He, M., Davids, W. J., Breen, A. J. & Ringer, S. P. Quantifying short-range order using atom probe tomography. Nat. Mater. 23, 1200–1207 (2024).

George, E. P. & Ritchie, R. O. High-entropy materials. Mrs Bull. 47, 145–150 (2022).

Cantor, B. Multicomponent high-entropy cantor alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 120, 100754 (2021).

Ding, Q. et al. Tuning element distribution, structure and properties by composition in high-entropy alloys. Nature 574, 223–227 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Short-range order and its impact on the CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nature 581, 283–287 (2020).

Xie, Z. et al. Role of local chemical fluctuations in the shock dynamics of medium entropy alloy CoCrNi. Acta Mater. 221, 117380 (2021).

He, Q. F. et al. A highly distorted ultraelastic chemically complex elinvar alloy. Nature 602, 251–257 (2022).

Jian, W.-R. et al. Effects of lattice distortion and chemical short-range order on the mechanisms of deformation in medium entropy alloy CoCrNi. Acta Mater. 199, 352–369 (2020).

Spurling, R. J., Lass, E. A., Wang, X. & Page, K. Entropy-driven phase transitions in complex ceramic oxides. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 090301 (2022).

McCormack, S. J. & Navrotsky, A. Thermodynamics of high entropy oxides. Acta Mater. 202, 1–21 (2021).

Nix, F. C. & Shockley, W. Order-disorder transformations in alloys. Rev. Mod. Phys. 10, 1–71 (1938).

Siegel, S. On the kinetics of the order-disorder transformation in Cu3Au. J. Chem. Phys. 8, 860–866 (1940).

Van Baal, C. M. Order-disorder transformations in a generalized Ising alloy. Physica 64, 571–586 (1973).

Chen, C., Yu, D. & Chen, K.-N. Vertical interconnects of microbumps in 3D integration. MRS Bull. 40, 257–263 (2015).

Tu, K. N. Reliability challenges in 3D IC packaging technology. Microelectron. Reliab. 51, 517–523 (2011).

Huang, Z. et al. Size-controlled synthesis of ultrafine silver powders for electronic paste using a one-pot aqueous method. Mater. Des. 252, 113773 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. Low resistivity achieved through enhanced sintering activity in silver paste with submicron particles created through nanoparticle self-assembly. APL Mater. 13, 021103 (2025).

Li, P. et al. Optimizing silver paste conductivity with controlled convection for nanowrinkle growth. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 34181–34191 (2024).

Kwon, H. et al. Investigation of the electrical contact behaviors in au-to-au thin-film contacts for RF MEMS switches. J. Micromech. Microeng. 18, 105010 (2008).

Xie, X. et al. Sliding electrical contact behavior of AuAgCu brush on au plating. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 25, 3029–3036 (2015).

Kikuchi, R. A theory of cooperative phenomena. Phys. Rev. 81, 988–1003 (1951).

Hultgren, R. R. et al. Selected Values Of The Thermodynamic Properties of Binary Alloys. American Society for Metals, (1973).

Wei, S.-H., Mbaye, A. A., Ferreira, L. G. & Zunger, A. First-principles calculations of the phase diagrams of noble metals: Cu-Au, Cu-Ag, and Ag-Au. Phys. Rev. B 36, 4163–4185 (1987).

Kusoffsky, A. Thermodynamic evaluation of the ternary Ag–Au–Cu system—including a short range order description. Acta Mater. 50, 5139–5145 (2002).

Kabekkodu, S. N., Dosen, A. & Blanton, T. N. PDF-5+: a comprehensive Powder Diffraction FileTM for materials characterization. Powder Diffr. 39, 47–59 (2024).

Cao, W., Chang, Y. A., Zhu, J., Chen, S. & Oates, W. A. Application of the cluster/site approximation to the calculation of multicomponent alloy phase diagrams. Acta Mater. 53, 331–335 (2005).

Schön, C. G., Duong, T., Wang, Y. & Arróyave, R. Probing the entropy hypothesis in highly concentrated alloys. Acta Mater. 148, 263–279 (2018).

Mohri, T., Sanchez, J. M. & De Fontaine, D. Short range order diffuse intensity calculations in the cluster variation method. Acta Met. 33, 1463–1474 (1985).

Xu, L. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of pure copper plate processed by novel dynamic offsets and shear force adjustment rolling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 558–570 (2024).

Robinson, J., Arjunan, A., Stanford, M., Lyall, I. & Williams, C. Effect of silver addition in copper-silver alloys fabricated by laser powder bed fusion in situ alloying. J. Alloy. Compd. 857, 157561 (2021).

Xie, M. et al. Microstructural evolution and strengthening mechanisms in cold-rolled Cu–Ag alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 851, 156893 (2021).

Robinson, J., Stanford, M. & Arjunan, A. Correlation between selective laser melting parameters, pore defects and tensile properties of 99.9 % silver. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101550 (2020).

Arjunan, A. et al. Mechanical performance of additively manufactured pure silver antibacterial bone scaffolds. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 112, 104090 (2020).

Yan, X. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of pure copper manufactured by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 789, 139615 (2020).

Zhao, H., Fu, H., Xie, M. & Xie, J. Effect of ag content and drawing strain on microstructure and properties of directionally solidified Cu-Ag alloy. Vacuum 154, 190–199 (2018).

Kim, J.-Y. & Greer, J. R. Tensile and compressive behavior of gold and molybdenum single crystals at the nano-scale. Acta Mater. 57, 5245–5253 (2009).

Al-Fadhalah, K. J. H., Li, C.-M., Beaudoin, A. J., Korzekwa, D. A. & Robertson, I. M. Microplastic processes developed in pure ag with mesoscale annealing twins. Acta Mater. 56, 5764–5774 (2008).

Sharpe, W. N. et al. Tensile stress-strain curves of gold film. In Proc. ASME 2006 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition: Materials, Nondestructive Evaluation, and Pressure Vessels and Piping, Chicago, Illinois, USA, 533–540 (ASME 2006) https://doi.org/10.1115/IMECE2006-13290.

Fu, L. et al. Phase formation, microstructure evolution and strengthening mechanism of Au27.9Ag20.3Cu51.8 noble metal medium-entropy alloy during cold deformation and aging. Mater. Sci. Eng.: A 887, 145733 (2023).

Lilensten, L. et al. Design and tensile properties of a bcc Ti-rich high-entropy alloy with transformation-induced plasticity. Mater. Res. Lett. 5, 110–116 (2017).

Otto, F., Yang, Y., Bei, H. & George, E. P. Relative effects of enthalpy and entropy on the phase stability of equiatomic high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 61, 2628–2638 (2013).

Brodie, J. et al. Stability of the B2 phase in refractory high entropy alloys containing aluminum. Acta Mater. 268, 119745 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Zhou, Y. J., Lin, J. P., Chen, G. L. & Liaw, P. K. Solid-solution phase formation rules for multi-component alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 10, 534–538 (2008).

He, J. Y. et al. A precipitation-hardened high-entropy alloy with outstanding tensile properties. Acta Mater. 102, 187–196 (2016).

Luan, H. et al. Spinodal decomposition and the pseudo-binary decomposition in high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 248, 118775 (2023).

Sundman, B., Fries, S. G. & Oates, W. A. A thermodynamic assessment of the Au-Cu system. Calphad 22, 335–354 (1998).

Gallego, L. J., Somoza, J. A., Alonso, J. A. & Lopez, J. M. Determination of phase diagrams of eutectic binary alloys with partial solid solubility. Phys. B 154, 82–86 (1988).

Ishai, O. & Cohen, L. J. Elastic properties of filled and porous epoxy composites. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 9, 539–546 (1967).

Ahmed, S. & Jones, F. R. A review of particulate reinforcement theories for polymer composites. J. Mater. Sci. 25, 4933–4942 (1990).

Ren, J. et al. Strong yet ductile nanolamellar high-entropy alloys by additive manufacturing. Nature 608, 62–68 (2022).

Fan, L. et al. Ultrahigh strength and ductility in newly developed materials with coherent nanolamellar architectures. Nat. Commun. 11, 6240 (2020).

R. H. J. Hannink, A. J. Hill, Nanostructure Control of Materials, Woodhead Publishing, (2006).

Liu, H., Tang, S., Ma, Y., Liu, W. & Liang, C. Short-range ordering governs brittleness and ductility in W-Ta solid solution: Insights from pugh’s shear-to-bulk modulus ratio. Scr. Mater. 204, 114136 (2021).

Schön, C. G. On short-range order strengthening and its role in high-entropy alloys. Scr. Mater. 196, 113754 (2021).

Wang, F. et al. Shearing brittle intermetallics enhances cryogenic strength and ductility of steels. Science 384, 1017–1022 (2024).

Xu, B. et al. Harnessing instability for work hardening in multi-principal element alloys. Nat. Mater. 23, 755–761 (2024).

Fisher, J. C. On the strength of solid solution alloys. Acta Met. 2, 9–10 (1954).

Flinn, P. A. Solute hardening of close-packed solid solutions. Acta Met. 6, 631–635 (1958).

Schön, C. G. & Kikuchi, R. Scalar-product cluster variation method layer formulation for the irregular tetrahedron cluster in bcc lattices. Phys. Rev. B 72, 094101 (2005).

Kikuchi, R. & Cahn, J. W. Theory of interphase and antiphase boundaries in f.c.c. alloys. Acta Met. 27, 1337–1353 (1979).

Kikuchi, R. Boundary free energy in the lattice model. I. General formulation. J. Chem. Phys. 57, 777–782 (1972).

Kikuchi, R. Boundary free energy in the lattice model. II. Applications of the general formula. J. Chem. Phys. 57, 783–787 (1972).

Kikuchi, R. Boundary free energy in the lattice model. III. Solution of the paradox. J. Chem. Phys. 57, 787–791 (1972).

Cowley, J. M. An approximate theory of order in alloys. Phys. Rev. 77, 669–675 (1950).

Cowley, J. M. Short-range order and long-range order parameters. Phys. Rev. 138, A1384–A1389 (1965).

Kikuchi, R. & Murray, J. L. Tetrahedron treatment of the fcc lattice. Calphad 9, 311–348 (1985).

Kikuchi, R. Natural iteration method and boundary free energy. J. Chem. Phys. 65, 4545–4553 (1976).

Kikuchi, R. A theory of cooperative phenomena. II. equation of states for classical statistics. J. Chem. Phys. 19, 1230–1241 (1951).

Kurata, M., Kikuchi, R. & Watari, T. A theory of cooperative phenomena. III. detailed discussions of the cluster variation method. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 434–448 (1953).

Schön, C. G. & Inden, G. Concentration dependence of the excess specific heat capacity and of the thermodynamic factor for diffusion in f.c.c. and b.c.c. ordering systems. Acta Mater. 46, 4219–4231 (1998).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Miao Song, Junyang He and Zhangwei Wang for their insightful discussions, and we thank the Powder Metallurgy Research Institute for providing technical support with their double Cs–corrected TEM system. Part of this study was supported technically by Institute for Advanced Study and High-Performance Computing Center of Central South University, we thank Shang Zhengang for the technical support with 3DAP. S.T. acknowledges the support from Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 2019JJ50813). W.L. acknowledges the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51931012). C.L. acknowledges the support from Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 2025JJ20048), and from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers 92373208, 52471026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T. conceived the project. The experiments were carried out by S.T., G.L., B.C. and C.L. The analysis of the data was conducted by S.T., G.L., C.L., P.L., J.Y. and Z.H. The preparation of the figures was undertaken by G.L. and C.L. The composition and editing of the draft were the responsibility of S.T., G.L. and C.L. The supervision of the project was overseen by Y.M. and W.L. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yoon-Uk Heo and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, S., Luo, G., Li, P. et al. Damascus-style hierarchical microstructures enable a strong and ductile medium-entropy alloy. Nat Commun 16, 9624 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64058-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64058-x