Abstract

Echocardiography is crucial for diagnosis and management of cardiac diseases. Existing reference values may not be applicable to rural African populations due ethnicity related variability and limited data. This study aimed to establish reference values for echocardiographic parameters in a rural population. We assessed echocardiographic parameters in the adult population ( ≥ 18 years) from rural areas endemic for loiasis in the Republic of Congo. Reference values were established using participants with normal BMI, no hypertension/diabetes, and no significant echocardiographic abnormalities. Statistical analyses included comparisons by sex and age group. This study of 422 participants revealed significant variations in echocardiographic parameters across age and sex groups. Left ventricular dimensions and mass were larger in males, while left ventricular ejection fraction was higher in females. Left atrial dimensions, including area and volume, increased with age. Right ventricular dimensions also exhibited sex and age-related differences, with males generally showing larger dimensions. The prevalence of echocardiographic abnormalities varied significantly compared to reference values from other populations. This study provides age- and sex-stratified reference values for echocardiographic parameters in a rural population endemic for loiasis, highlighting the need for population-specific reference values and a standardized approach to their establishment to improve comparability across studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) account for ~one-third of global deaths, with 18.6 million fatalities reported in 20191. Historically, Africa was thought to be relatively spared from these conditions, but the past three decades have witnessed a 50% increase in the burden of CVDs on the continent. This includes over 37% of deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and 22.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost due to cardiovascular conditions in 20172,3,4. While traditional risk factors for CVDs, such as hypertension and diabetes, may be less prevalent in rural African populations, other unique challenges, such as limited healthcare access and a high burden of infectious diseases, may contribute to significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality5.

Echocardiography is a cornerstone of cardiovascular evaluation, providing critical insights into disease severity, therapeutic decision-making, prognosis, and treatment monitoring6. However, significant variability in echocardiographic measurements has been observed based on age and sex, physical activity, and ethnicity, even after adjusting for body surface area (BSA)7,8,9. In African populations, while some studies have proposed reference values for echocardiographic parameters, these investigations have largely focused on urban or hospital-based populations. Studies were conducted in South Africa, Nigeria, and Angola, and included apparently healthy patients presenting to urban echocardiography centers8,10,11. Consequently, these reference values may not be representative and applicable to populations living in rural areas, which often exhibit different physical activity patterns, cultural habits, exposure to diseases, and limited access to healthcare, and consequently, could help distinguish a cardiopathy from a local norm variant.

The most common causes of heart failure reported in 22 studies conducted across Africa were hypertensive heart disease, followed by rheumatic heart disease and cardiomyopathies including dilated cardiomyopathies, peripartum cardiomyopathies, HIV-associated cardiomyopathies and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, representing the most common cardiomyopathies in Sub-Saharian Africa12. While hypertension remains prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa (~25–30%) and is the most common cause of heart failure in rural areas, only 6% of these studies were conducted in rural settings, where rheumatic heart disease and cardiomyopathies were found to be more prominent causes relative to urban areas13,14. This highlights the unique context of rural African settings, where the burden of infectious diseases could potentially further complicate cardiovascular health and underscores the need for a better understanding of cardiac parameters in these populations15. Parasitic diseases that are prevalent in these rural and disadvantaged areas have been shown to significantly contribute to increased morbidity and mortality, including cardiovascular diseases16,17,18. This is especially the case of loiasis (a filarial disease) which is one of the most prevalent in rural areas of central Africa. In this latter case, accelerated vascular aging, along with its secondary cardiovascular complications, could potentially result from or be reflected by increased arterial stiffness associated with loiasis [14, 18, 19]; this factor may, in turn, influence echocardiographic findings. In the absence of tailored reference values for echocardiographic parameters, accurate diagnosis and effective management of cardiac alterations in these populations becomes challenging. Indeed, these values could help distinguish a cardiopathy from a local norm variant.

To address this gap, we conducted this study to establish reference values for echocardiographic parameters in a rural population of central Africa. Our findings aim to enhance the understanding of echocardiographic norms in underrepresented populations, with implications for both local clinical practice and global research on cardiovascular health disparities.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

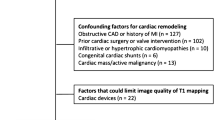

Of the 988 participants eligible for this study, 422 healthy individuals were ultimately included to establish reference intervals. Exclusion criteria comprised diabetes (n = 3), hypertension (n = 403), significant echocardiographic abnormalities (n = 103), and underweight status (n = 57). A flow chart depicting the participant selection process is provided in Fig. 1. The sample was predominantly male (72.3%), with a mean age of 44.0 ± 13.7 years. Smoking history was reported by 20.8%. Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 119.2 ± 11.5 mmHg and 70.3 ± 10.0 mmHg, respectively. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population.

Echocardiographic parameters in healthy population (n = 422)

Reference intervals

Reference values for echocardiographic parameters, stratified by age and sex and derived from the healthy population, are presented in Table 2 (using mean ± SD) and Table 3 (using normal values range), and in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, 3 for details. Supplementary Tables 4, 5, and 6 present the detailed reference values for the population excluding participants with stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease. These values can be used to identify individuals whose echocardiographic measurements fall within the expected reference range. For example, for left ventricular (LV) septal wall thickness in women under 40 years of age, the reference interval is 0.50 to 0.98 cm. Similarly, in men aged 60 and over, the reference interval for the same measurement is 0.59 to 1.2 cm. Compared to reference intervals found in the literature, reference values from this study showed the greatest discrepancies for RA area, peak TR velocity, mean aortic valve gradient et E wave deceleration slope (Fig. 2).

A, B Male and female values for left-sided cardiac parameters. C, D Male and female values for right-sided cardiac parameters and Doppler indices. *This parameter was specifically assessed in participants with TR, leading to the exclusion of 95 participants without this condition from the calculation. AR Aortic Regurgitation; BSA Body Surface Area; IVC Inferior Vena Cava; LA Left Atrium/Left Atrial; LV Left Ventricle/Left Ventricular; LVEF Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; RA Right Atrium/Right Atrial; RV Right Ventricle/Right Ventricular; TAPSE Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion; TR Tricuspid Regurgitation; VTI Velocity Time Integral. The bars in the figure indicate only the abnormal threshold for each parameter, with values to the right denoting the upper limit and those to the left indicating the lower limit. For instance, a right atrial surface area exceeding 8.65 based on our reference values or surpassing 22 according to literature is considered elevated in men. Similarly, the mean aortic valve gradient is deemed abnormal if below 14.7 as per our reference values or under 20 based on literature data.

LV measurements

LV diastolic internal diameter averaged 4.4 ± 0.4 cm overall, with males having larger diameters (4.5 ± 0.4 cm) than females (4.2 ± 0.4 cm) (p < 0.001). Similar differences by sex were observed for LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes measured in both 4- and 2-chamber views (p < 0.001), with males consistently demonstrating larger volumes. LV mass indexed to BSA also showed significant differences by both sex (higher in males, 3.6 ± 0.5 g/m² vs. 3.0 ± 0.5 g/m² in females) and age (p < 0.001).

LA measurements

Left atrial (LA) size and volume were assessed across various age groups and sexes. LA volumes and LA areas (4-chamber) were similar between sexes, whether indexed or not. While absolute LA volume trended towards being larger in males (44.6 ± 11.9 mL vs. 40.4 ± 11.6 mL), this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.068). Age did not appear to significantly impact LA size or volume in this study (Table 2).

RV measurements

RV longitudinal diameter was significantly larger in males (3.2 ± 0.4 cm) compared to females (3.1 ± 0.4 cm, p = 0.009). Similarly, RV end-diastolic and end-systolic areas were also significantly larger in males (15.0 ± 2.9 cm² and 8.1 ± 1.8 cm², respectively) compared to females (12.5 ± 2.3 cm² and 6.6 ± 1.4 cm², both p < 0.001). However, RVOT prox showed no significant difference between the sexes (p = 0.060). TAPSE and peak systolic velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation jet were similar between the sexes. While there was a statistically significant difference in RV longitudinal diameter between age groups (p = 0.036), no specific trend was observed, and other RV parameters were not significantly influenced by age. Significant differences were observed in both maximum and minimum IVC diameters across sexes (p < 0.001), with males demonstrating the largest mean diameters (Table 2).

LV and RV function

LVEF did not differ significantly across age groups and sexes (p > 0.999). More details are presented in Table 2. While cardiac output remained relatively similar between males and females (p > 0.999), a non-significant decrease was observed across age groups (p = 0.168).

Although not statistically significant, a consistent trend towards decreased left ventricular systolic function with increasing age was observed, as shown by higher TAPSE and peak S velocity TR values in younger participants.

Pulmonary pressure

Pulmonary valve acceleration time demonstrated a statistically significant difference across age groups (p < 0.001), with the oldest age group showing a lower mean value. However, no significant difference was observed between males and females (p = 0.689). Similarly, the peak tricuspid regurgitation (TR) gradient showed no significant difference between males and females (p > 0.999), but significantly increase across age groups (p = 0.014), with mean values of 18.0 ± 5.5 mmHg for < 40 years, 19.4 ± 5.3 mmHg for 40–59 years, and 21.7 ± 5.4 mmHg for > 60 years.

Diastolic function

Several Doppler and tissue Doppler parameters were assessed. Peak pulmonary artery systolic velocity was significantly lower in males compared to females (p < 0.001). However, when stratified by age, this difference disappeared, and instead, the oldest age group ( ≥ 60 years) demonstrated a significantly higher peak pulmonary artery systolic velocity compared to the other age groups (p < 0.001). Peak mitral inflow E velocity was significantly influenced by age, with the youngest group ( < 40 years old) having higher E velocities and the oldest group having the lowest (p < 0.001). Similar trends with age were observed for E-wave deceleration slope (p < 0.001), septal and lateral e’ velocities (both p < 0.001), and average e’ velocity (p < 0.001). Consequently, the E/e’ ratios, whether septal, lateral, or averaged, were all significantly affected by age, with the highest values observed in the oldest age group (p = 0.013, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). The peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity also showed significant variation across age groups, with the oldest group exhibiting the highest velocity (p = 0.025). E/A ratio differed significantly across age groups (p < 0.001) but not between sexes (p = 0.144). More details are presented in Table 2.

Echocardiographic abnormalities in the whole population (n = 988)

To describe the discrepancies between our reference values and those present in the literature, the prevalence of echocardiographic abnormalities diagnosed according to our study’s and literature-derived criteria were compared in Table 47,19,20,21,22. Our reference intervals provide a similar prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (4.05%) compared to literature values (3.85%). However, we observed statistically significant differences in the prevalence of several other abnormalities. Left ventricular dilation was more common when using our reference values (3.88% vs 0.63%), while aortic dilation (25.7% vs 77.7%), left atrial dilation (8.14% vs 41.1%), right ventricular dilation (3.22% vs 28%), and systolic dysfunction (7.18% vs 19.4%) were all less prevalent when using our reference values compared to the literature reference values.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to report reference values for echocardiographic parameters in an adult population living in a rural area endemic for loiasis in the Republic of the Congo. The observed morphological abnormalities varied significantly by age (more frequent in the elderly) for most parameters and by sex (more frequent in women) for some parameters. For metric values (chamber dimensions and Doppler), a significant difference was observed between sexes and across age groups for almost all variables, including those indexed to BSA. These results are consistent with those reported in other studies conducted in both Caucasian and African populations11,19,20. This highlights the need to establish reference values for each age and sex group in order to account for this variability.

In comparison to women, men exhibited significantly larger left ventricular dimensions and volumes, including end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, end-diastolic diameter, and ventricular mass. These results are consistent with those previously reported in Nigerian, Angolan, Brazilian, and European populations. Conversely, women demonstrated a significantly higher left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) than men, a finding similar to that observed in the Angolan population. However, no statistically significant sex-based differences in LVEF were observed in either Brazilian or European populations11,20,23,24. This could further support the hypothesis that outcomes vary significantly based on ethnicity, lifestyle, physical activity, diet, and alcohol consumption, as suggested by previous studies25. The age-related variations in these measurements were not uniform. While end-diastolic and end-systolic left ventricular volumes demonstrated a significant decrease with increasing age, there was a concomitant significant increase in septal and ventricular wall thickness. Furthermore, the left ventricular ejection fraction did not exhibit a significant age-related variation. The literature on age-related changes in these cardiac parameters is inconsistent, with studies reporting a wide range of findings, including increases, decreases, and no significant changes with advancing age. These discrepancies may be attributed to various factors, such as differences in study populations, methodologies, and definitions of normal aging8,23,26,27. Note that considering the specificities of our population, a certain dietary habit or the consumption of locally available plants (with a high proportion of indigenous people) could potentially contain cardioprotective substances, such as beta-blockers. Therefore, it is essential to provide age-specific reference values for these echocardiographic parameters, in order to account for the unique characteristics of each age group.

Left atrial measurements, both indexed and non-indexed, didn’t show significant variation with age, including both surface area and volume. This finding contrasts with results reported in Caucasian and Brazilian populations, where left atrial dimensions were not found to correlate with age. Nevertheless, these studies reported significant sex-related differences, with higher values in men, a finding also observed in our study population20,23. Therefore, contrary to the recommendations of other authors suggesting that age- and sex-specific reference values for the left atrium are unnecessary, it is crucial to establish distinct reference ranges for these variables in rural populations. This approach will allow for a more accurate assessment of left atrial size and function in this particular demographic.

Unlike measurements of other cardiac chambers, right ventricular parameters did not exhibit a consistent age-related trend. For instance, basal diameter exhibited comparable values among all age groups. Conversely, end-systolic volume demonstrated a significant decrease with advancing age. Similarly, sex-based differences in right ventricular parameters were inconsistent. These findings diverge from those reported by other African studies, which did not identify significant differences in right ventricular parameters based on age and sex8. Conversely, in Caucasian populations, these parameters were significantly lower in women and decreased with age20.

Overall, the reference values obtained for the different age and sex groups in our study differed significantly from those reported in the literature. When applying these cut-offs to metric parameters associated with various abnormalities (Table 5), it became apparent that the prevalence of these abnormalities varied substantially depending on whether our study’s reference values or those from the literature were used. Actually, our findings suggest that cardiac adaptations in our population may reflect both environmental and physiological factors. While most cardiac measurements were close to international reference values, we observed key differences, including a higher normal range for left ventricular end-diastolic volume (4-chamber view), a lower right atrial surface area, lower E/e’ ratios (septal, lateral, and average), and a higher normal E-wave deceleration slope. These variations likely influenced the classification of cardiac abnormalities, with a higher prevalence of left ventricular dilation and a lower prevalence of left atrial dilation, aortic dilation, right ventricular dilation, and systolic dysfunction when using our reference values compared to international ones. This suggests that standard global reference intervals may not be fully applicable to this population and could lead to over- or underestimation of certain cardiac conditions.

Physiological adaptations in this population could be driven by factors such as chronic exposure to high levels of physical activity, nutritional patterns, or genetic predispositions. Notably, the lower E/e’ ratios and the reduced prevalence of left atrial and right ventricular dilation may indicate more favorable diastolic function, potentially reflecting lower overall cardiac stress. An additional hypothesis is the potential cardioprotective effect of traditional plant-based medicine widely used in this population. Several locally used medicinal plants have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory properties, which could contribute to maintaining vascular health and preventing cardiac remodeling. Further studies exploring biochemical markers and longitudinal cardiovascular outcomes in individuals using these traditional remedies could provide valuable insights into their protective effects.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although we implemented a thorough clinical screening protocol, we cannot definitively exclude all chronic or subclinical conditions in the absence of exhaustive laboratory or imaging investigations. The criteria used to define the healthy population may not have identified all potential underlying pathologies that could influence cardiac morphology, such as dyslipidaemia or infraclinical cardiac diseases, though available data on lipidic profiles were normal. Additionally, we acknowledge that hypertension should ideally be confirmed by at least two measurements taken at separate time points. Relying on a single visit as we did may have led to an overestimation of some hypertension cases. This limitation reflects the realities of conducting population-based studies in remote rural areas with constrained resources. Second, while we tested for common parasitic infections, we chose not to exclude individuals with asymptomatic Loa loa microfilaremia or soil-transmitted helminths, given their extremely high prevalence in the study region and the absence of clear evidence of their impact on cardiac morphology. Third, renal function assessment was not available for all participants. However, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding those with CKD stage 3–5, and provide this subset as supplementary reference data. Fourth, the sample was not randomly selected from the study population, which could lead to a non-representative sample, though given that the study focused on establishing reference values in a healthy population, this potential bias may not have significantly impacted the results. Fifth, due to technical limitations with the Philips CX50, direct export of the LV 4-chamber biplane measurements was not possible, and we therefore approximated LV end-diastolic volume by averaging the 4- and 2-chamber views, which may have affected our categorizations and prevalence estimates for LV dilatation. Additionally, the absence of global longitudinal strain (GLS) measurement represents a methodological limitation, as GLS is valuable for detecting subclinical systolic dysfunction, though this was not feasible with our portable equipment under field conditions. Sixth, two operators performed all measurements using dedicated devices, with each patient evaluated by only one operator, which could limit generalizability due to potential operator-dependent variability, though previous studies have reported good to excellent intra- and inter-observer reproducibility for echocardiographic measurements.20 Finally, the generalizability of our findings may be limited as the study was conducted in a single geographical region, and these reference values may not be directly applicable to populations from other geographical areas with different genetic backgrounds or environmental conditions. These limitations underline the need to interpret our reference values within the context of the local health system and epidemiological landscape. Nonetheless, we believe our data offer a relevant and realistic echocardiographic reference adapted to populations living in rural Central Africa, representing the first study of such scale conducted in a region endemic for loiasis.

Finally, echocardiographic parameters exhibited significant variations across age and sex groups. This study provides reference values for echocardiographic measurements stratified by age and sex in an area where no data was available. Comparisons with data from other populations revealed discrepancies in the prevalence of abnormalities defined using these reference values, underscoring the need for population-specific reference values tailored to age and sex. Additionally, there is a pressing need for consensus on the definition of a reference population and the methodology used to establish reference values for echocardiographic measurements, to reduce discrepancies across studies.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted between May and June 2022 as part of the Morbidity due to Loiasis (MORLO) project which aims at assessing the morbidity and the prevalence of organ complications related to loiasis. Data were collected from participants recruited from 21 villages in the Lekoumou division of the Republic of Congo, a forest area endemic to loiasis with a combined population of 16,284 inhabitants (Census 2023).

Participants

Participants were recruited from a sample of volunteers aged 18 years and over who participated in a 2019 pre-screening survey for inclusion in a clinical trial for the treatment of loiasis28. Individuals with a Loa loa microfilarial load exceeding 500 mf/ml in 2019 were matched with a control of the same sex and age (within 5 years) residing in the same village, and having no microfilariae at the pre-screening. A flow diagram of the pre-screening and selection process for this study was published in a previous article15.

Data collection

After identifying eligible participants in the database, they were invited to Sibiti Hospital where data was collected. Participants who consented to participate in the study underwent a clinical examination during which sociodemographic data and medical history were collected, including assessment of current medications, known cardiovascular or renal diseases, and other chronic conditions. Anthropometric measurements and blood pressure were taken. Stool examination was performed in participants who agreed to provided samples to screen for soil-transmitted helminths. Participants with fever or clinical symptoms suggestive of malaria were excluded. Whole blood samples were collected from each patient and analyzed for HbA1c and lipid profile with a point-of-care Afinion 2 device (Abbott Rapid Diagnostics, Bièvres, France). Additionally, a calibrated thick blood smear was performed following inclusion to quantify microfilarial density, as the 2019 screening was used solely to pre-identify potential participants. Finally, participants underwent an echocardiography to assess cardiac morphology and function.

Echocardiographic examination

Echocardiography was performed on all. Two-dimensional echocardiography with m-mode, pulse wave (PW), continuous wave (CW), and tissue doppler imaging (TDI) was performed with a CX50 ultrasound system (Philips). The acquisition protocol adhered to the standards of the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging22. Echocardiographic examinations were performed by two qualified operators from the University Hospital of Montpellier: a certified cardiologist-sonographer (VD, 2/3 of examinations) and an anaesthesiologist from the cardio-surgical intensive care unit (LR, 1/3 of examinations). To ensure data consistency, all final interpretations and measurements were centralized and conducted exclusively by the cardiologist-sonographer following a standardized quality control process.

Echocardiographic measurements

A comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation was performed to assess ventricular and atrial size, left and right ventricular systolic and diastolic function, regional wall motion abnormalities, valvular structures and function, and evaluation of pericardium adhering to the latest international guidelines and recommendations22,29. Image quality was excellent for the vast majority of participants, with only a very small number of individuals having suboptimal echogenicity that did not compromise satisfactory echocardiographic evaluation. Left ventricular (LV) end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes, as well as LV ejection fraction (EF), were calculated using the biplane method of disks (modified Simpson’s rule).

LV diastolic function and left atrial filling pressure (LAP) were evaluated using mitral inflow velocities (E/A ratio), septal mitral annulus velocity (e’), tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity, E/e’ ratio and left atrial (LA) volume index30.

Right ventricular (RV) function was assessed using tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), systolic excursion velocity of the tricuspid annulus by tissue Doppler imaging (s’), and fractional area change (FAC). Pulmonary artery pressure was estimated using TR velocity. Right atrial pressure was estimated based on the diameter of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and its inspiratory collapse22,31.

The following variables were indexed to BSA for analysis: LV septal wall thickness, LV posterior wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume (2-chamber and 4-chamber), LV end-systolic volume (2-chamber and 4-chamber), LV mass, LA area (2-chamber and 4-chamber), LA volume, RV basal diameter, right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) prox, RV end-diastolic area, RV end-systolic area, RA area, aortic sinotubular junction diameter, sinus of Valsalva diameter, ascending aorta diameter, Cardiac output, and aortic valve area. Indexing to BSA was performed to account for variations in body size among the study population. All echocardiographic examinations were systematically reviewed and validated by an experienced cardiologist-sonographer to ensure consistency and reliability of measurements.

Construction of reference values

For the construction of reference values charts, we considered the group of healthy participants as those with a BMI between 18 and 35 kg/m², without hypertension (blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or a history of hypertension under treatment) or diabetes (HbA1c > 6.5% or known diabetes under treatment), and without any significant morphological abnormalities on echocardiography. Specifically, we excluded individuals with significant valvulopathy (mitral or aortic insufficiency of grade 3 or 4, tricuspid insufficiency of grade 3 or 4), pulmonary stenosis, dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, suspected cardiac amyloidosis, regional wall motion abnormalities (hypokinesia, dyskinesia), restrictive filling patterns, significant pericardial effusion, or congenital anomalies such as severe ventricular septal defect or atrial septal defect. To account for the potential impact of chronic kidney disease on cardiac measurements, we performed a sensitivity analysis by additionally excluding participants with stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease using EKFC KDIGO classification. Echocardiographic measurements for each population age and gender subgroups were described using the mean and standard deviation. Reference intervals were determined using a parametric approach, calculated as the mean ± 2 standard deviations (SD), applied to the healthy population.

Diagnostic of cardiac abnormalities

Once these reference charts were established, we aimed to classify our entire population according to ten distinct cardiac abnormalities that were defined based on the reference values derived from the healthy population examined as part of the present study, but also from reference values obtained from American and European populations (Table 5 and Supplementary Tables). To minimize the total number of comparison articles and consequently reduce variability in methodological approaches, we prioritized studies with the maximum number of available echocardiographic parameters. External reference values were primarily derived from the NORRE study. Additional reference standards were obtained from established international guidelines: British Society of Echocardiography recommendations, American Society of Echocardiography and European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging joint recommendations and European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and American Society of Echocardiography guidelines7,19,20,21,22. Table 5 presents these ten abnormalities and definitions. Last, impaired diastolic function was assessed according to the recommendations of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (Supplementary Fig. 1)30. As TR velocity was exclusively evaluated in participants presenting with TR, individuals without this condition were assumed to have a TR velocity < 2.8 cm/s (considered within the normal range).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were described using mean ± standard deviation, median (and interquartile range), and range. Categorical variables were described using frequency and percentage. For the identified morphological anomalies, we described the distribution by sex and age group. The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions, depending on whether the expected cell count was less than or equal to 5. For echocardiographic measurements, a parametric Student t-test was used to compare values between sexes, and ANOVA test was used to compare values between age groups. P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm correction method. Once this work of constructing reference charts for echocardiographic norms was completed, we applied these cut-offs to classify individuals based on 10 clinically significant echocardiographic abnormalities (Table 5). Data were initially collected on paper forms in the field and subsequently entered into a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database by two independent operators, with discrepancies resolved by a third operator to ensure data accuracy. Data were analysed using R version 4.2.3 (2023-03-15 ucrt) and RStudio version 2023.6.1.524 (Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA.) with tidyverse and gtsummary packages32,33.

Inclusion and ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Congolese Foundation for Medical Research (No. 036/CIE/FCRM/2022) and administrative authorization by the Congolese Ministry of Health and Population (No. 376/MSP/CAB/UCPP-21). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the fundamental principles of ethics in research involving human subjects, as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki34.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are deposited with restricted access in DataSuds repository (IRD, France) at (https://doi.org/10.23708/HUNHAB). They cannot be publicly shared because of legal restriction. The access to the data is subject to approval and a data sharing agreement. Data can be made available to researchers for legitimate research purposes upon request to the corresponding author. Requests will be reviewed and responses provided within a few months. Once access is granted, data will remain available for the duration specified in the data sharing agreement. Related documentations are openly available and granted under CC-BY license.

References

Roth, G. A. et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 76, 2982–3021 (2020).

Murray, C. J. & Lopez, A. D. Global and regional cause-of-death patterns in 1990. Bull. World Health Organ 72, 447–480 (1994).

Noncommunicable Diseases | WHO | Regional Office for Africa. https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases (2025).

Gouda, H. N. et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Glob. Health 7, e1375–e1387 (2019).

Price, A. J. et al. Prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, and cascade of care in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional, population-based study in rural and urban Malawi. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 6, 208–222 (2018).

Lee, S. H. & Park, J.-H. The role of echocardiography in evaluating cardiovascular diseases in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diab Metab. J. 47, 470–483 (2023).

Patel, H. N. et al. Normal values of cardiac output and stroke volume according to measurement technique, age, sex, and ethnicity: results of the World Alliance of Societies of Echocardiography study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 34, 1077–1085.e1 (2021).

Nel, S. et al. Echocardiographic indices of the left and right heart in a normal black African population. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 33, 358–367 (2020).

Washburn, R. A. et al. Echocardiographic left ventricular mass and physical activity: quantification of the relation in spinal cord injured and apparently healthy active men. Am. J. Cardiol. 58, 1248–1253 (1986).

Oyati, A. I., Danbauchi, S. S., Alhassan, M. A. & Isa, M. S. Normal values of echocardiographic parameters of apparently healthy adult Nigerians in Zaria. Afr. J. Med Med Sci. 34, 45–49 (2005).

Morais, H., Feijão, A. & Pereira, S. D. V. Global longitudinal strain and echocardiographic parameters of left ventricular geometry and systolic function in healthy adult Angolans: effect of age and gender. gcsp 2022, e202202 (2022).

Agbor, V. N. et al. Heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa: a contemporaneous systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J. Cardiol. 257, 207–215 (2018).

Kwan, G. F. et al. A simplified echocardiographic strategy for heart failure diagnosis and management within an integrated noncommunicable disease clinic at district hospital level for sub-Saharan Africa. JACC Heart Fail 1, 230–236 (2013).

Tantchou Tchoumi, J. C. et al. Occurrence, aetiology and challenges in the management of congestive heart failure in sub-Saharan Africa: experience of the Cardiac Centre in Shisong, Cameroon. Pan Afr. Med J. 8, 11 (2011).

Campillo, J. T. et al. Association between arterial stiffness and Loa loa microfilaremia in a rural area of the Republic of Congo: A population-based cross-sectional study (the MorLo project). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0011915 (2024).

Kunutsor, S. & Powles, J. Cardiovascular risk in a rural adult West African population: is resting heart rate also relevant? 21, 584–91 (2014).

Buell, K. G. et al. Atypical clinical manifestations of loiasis and their relevance for endemic populations. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6, ofz417 (2019).

Mishra, A., Ete, T., Fanai, V. & Malviya, A. A review on cardiac manifestation of parasitic infection. Trop. Parasitol. 13, 8–15 (2023).

Caballero, L. et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal cardiac Doppler data: results from the NORRE Study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc.Imaging https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev083 (2015).

Kou, S. et al. Echocardiographic reference ranges for normal cardiac chamber size: results from the NORRE study. Eur. Heart J. - Cardiovascular Imaging 15, 680–690 (2014).

Harkness, A. et al. Normal reference intervals for cardiac dimensions and function for use in echocardiographic practice: a guideline from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res Pr. 7, G1–G18 (2020).

Lang, R. M. et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the american society of echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 28, 1–39 (2015).

Ângelo, L. C. S. et al. Echocardiographic Reference Values in a Sample of Asymptomatic Adult Brazilian Population. Arq Bras Cardiol. 89, 184–9 (2007).

Asch, F. M. et al. Similarities and differences in left ventricular size and function among races and nationalities: results of the World Alliance Societies of Echocardiography Normal Values Study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 32, 1396–1406.e2 (2019).

Shah, B. N. Normal reference range values in adult echocardiography: further evidence that race matters. Indian Heart J. 68, 758–759 (2016).

Choi, J.-O. et al. Normal echocardiographic measurements in a Korean population study: Part I. Cardiac chamber and great artery evaluation. J. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 23, 158 (2015).

Daimon, M. et al. Normal values of echocardiographic parameters in relation to age in a healthy japanese population the JAMP study: the JAMP study. Circ. J. 72, 1859–1866 (2008).

Campillo, J. T. et al. Safety and efficacy of levamisole in loiasis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, 19–27 (2022).

Baumgartner, H. et al. Recommendations on the echocardiographic assessment of aortic valve stenosis: a focused update from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 30, 372–392 (2017).

Nagueh, S. F. et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 29, 277–314 (2016).

Humbert, M. et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: Developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Endorsed by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) and the European Reference Network on rare respiratory diseases (ERN-LUNG). Eur. Heart J. 43, 3618–3731 (2022).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Sjoberg, D. D., Whiting, K., Curry, M., Lavery, J. A. & Larmarange, J. Reproducible summary tables with the gtsummary package. R. J. 13, 570–580 (2021).

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the HORIZON EUROPE European Research Council (ERC) 2020 [grant agreement No 949963]. CBC is the carrier of this grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank the French Embassy in Republic of Congo. We thank the Lékoumou health district, the medical, paramedical and technical staff of the Sibiti hospital, the PNLO and IRD drivers, and the participants for agreeing to participate. We also extend our thanks to Philips (Boris Glandieres) for the loan of a CX50 ultrasound machine, which accelerated the fieldwork.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.D., J.T.C. and C.B.C. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the study and the accuracy of the data analysis and are responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript. Concept and design: V.D. and C.B.C. Participation in the field study: V.D., J.T.C., L.G.R., E.L., S.D.S., F.M., S.D.S.P., M.B., M.C.H. and C.B.C. Acquisition of data or filed quality control: V.D., L.G.R., J.T.C. and C.B.C. Drafting of the manuscript: G.S.W., V.D. and C.B.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: G.S.W. and C.B.C. Interpretation of data: All authors Administrative, technical, or material support: J.T.C. Supervision: F.M. and C.B.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Philip Brainin and Martin Rohacek for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wafeu, G.S., Dupasquier, V., Campillo, J.T. et al. Reference values for cardiac dimensions and function in a rural population living in a loiasis-endemic area of the Republic of the Congo: An echocardiographic study. Nat Commun 16, 9109 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64131-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64131-5