Abstract

Aqueous Zn-I flow batteries are attractive for grid storage owing to their inherent safety, high energy density, and cost-effectiveness. However, Zn anode deposition/dissolution reactions cause severe water migration owing to ionic imbalance, especially under harsh conditions with high state-of-charge and high areal/volumetric capacities, further exacerbating intrinsic challenges for practical Zn-I systems. Herein, we develop a tailored ionic-molecular sieve membrane to regulate the transport behaviors of water/hydrated ion clusters, enabling the electrolyte balance by precise size sieving effects. Systematic investigations of different subnanometer pore sizes reveal that the optimal range (0.55–0.65 nm) can selectively intercept large hydrated ion clusters and reduce polyiodide shuttling. In this way, Zn-I flow batteries with this membrane exhibit a stable cycling over 2000 h (500 cycles) under harsh conditions (50% state-of-charge), achieving 66.4 mAh cm−2/53.2 Ah L−1posolyte/27.66 Wh L−1system. This systems also deliver a low self-discharging rate, retaining a high Coulombic efficiency of 98.5% after 3 days static flow. Furthermore, techno-economic cost analysis reveals a competitive levelized cost of long-term energy storage for systems incorporating this membrane (551.98 USD MWh−1 at an energy-to-power ratio of 18 h). This work offers insights into controlling water transport behaviors for realizing long-life flow batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

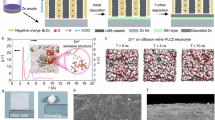

The new type of large-scale energy storage should mandate enhanced safety, prolonged duration, and minimized levelized cost1,2,3,4,5,6. Aqueous flow batteries (AFBs) stand out for accommodating large-scale energy storage at a relatively lower cost while maintaining high power output7,8,9,10. Among the array of prospective systems, aqueous zinc-iodine flow batteries (Zn-I FBs) manifest promising potential due to low cost, intrinsic safety, and high theoretical volumetric capacity (268 Ah L−1) (Fig. 1a)11,12,13,14,15,16. To meet the practical performance requirements, high-energy and long-term cycling stability under harsh operation conditions is a prerequisite for the Zn-based FBs, encompassing the high areal capacity for Zn-based anodes and the high operating state-of-charge (SOC) for iodide-cathodes. However, two issues protrude out as the irreversible side reactions at the anode (e.g., dendrites, hydrogen evolution) and the deleterious crossover of polyiodide active species (Fig. 1b)12,14,17,18. More remarkably, differing from conventional FBs (such as vanadium-based systems), water (H2O) out-of-balance (Fig. 1b) stands as another bottleneck issue for the Zn-based FBs due to the deposition/dissolution-type hybrid FBs19. A large amount of ion exchange causes variations in ionic concentrations between the posolyte and negolyte when realizing the high areal capacity. Meanwhile, H2O molecules could also transport through the membrane between the posolyte and the negolyte driven by the osmosis pressure and the electric field force, which would trigger a volumetric electrolyte loss and the cascaded deteriorate side reaction to culminate in battery deactivation18,19. Even though these issues widely existed in Zn-based FB systems, especially targeting high-energy performance, it has not been drawn much attention and systematically resolved due to the electrochemical performance assessments being carried out under gentle operating conditions featuring low SOC, low areal capacity, and low energy density, which directly dissatisfies Zn-I FBs for long-life energy storage applications4,18,20.

a Schematic illustration of Zn-I FBs battery for grid-scale energy storage. b Crossover of polyiodide (Ix−), side reaction, and severe water migration induced by pristine membranes leads to rapid cell failure of Zn-I FBs. c Alleviated crossover and water migration in Zn-I FBs using IMS-based membranes, where the volume of the posolyte and negolyte was maintained in balance. d The properties and performances of membranes with different subnanometer pores towards hydrated ionic size.

Developing high-performance membranes is an effective strategy to overcome those challenges by regulating the mass exchange behaviors through the membrane to suppress the crossover of active ion species (not involving the hydrated ions and the H2O molecules)18,21,22, which could be realized by introducing a functional layer onto the supporting membrane as composite membranes. The transport manners of the ion/molecule across the membrane could be regulated by the coating layer featuring different pore sizes, charged status, thicknesses, and other relevant parameters23,24,25,26,27. However, the micro-scale transport processes of the hydrated ions as charge carriers and the H2O molecules have been barely explored in current Zn-I FBs, especially the regulating principles of the mass exchange. Conversely, the ionic-molecular sieve (IMS) with tailorable nanochannels was widely investigated to regulate the transport manners of different ions/molecules based on the size-sieving effect18,24,28. Consequently, the as-developed IMS-coated composite membranes, namely the IMS membranes, accommodate great potential to regulate the mass exchange behaviors to improve the performance of Zn-I FBs (Fig. 1c). Nevertheless, the IMS membranes would encounter the trade-off dilemma between ionic selectivity and conductivity to be compatible with different sizes of hydrated ions and H2O molecules involved in negolyte/posolyte electrolytes, where H2O molecules could cross the membrane in the form of hydrated ion29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

Specifically, regarding the IMS with excessively smaller pore sizes, the IMS-based membranes could effectively impede the issues of polyiodide crossover and water migration (Fig. 1d-1), while those membranes unavoidably lead to low ionic conductivity due to the restricted ions flux within FB systems, resulting in low operating power density. On the other hand, when the pore size of the membrane is expanded to promote ion transport (Fig. 1d-2), it would crumble the selectivity for iodide active species and hydrated ions, resulting in low Coulombic efficiency (CE) and water out-of-balance of negolyte/posolyte electrolytes. However, the quantitative regulation relationship between the nanostructure of the IMS and the mass exchange behaviors of the membrane was not systematically elaborated. Thus, when employing the most universal and high ionic conductive potassium (K+) ions as supporting electrolytes, we propose that constructing the IMS-based membranes with a tailor-made pore size smaller than partially hydrated potassium ions (K+·(H2O)n, ~6 Å) could retain a certain level of ionic conductivity and suppress the crossover of polyiodides and imbalance of H2O molecules (Fig. 1d-3), achieving a long-duration cell cycling reaction in Zn-I FB systems.

Here, we systematically designed Zn-MOF-CJ3-based IMS (ZMC-IMS) membranes with the hydrated ions-confined subnanometer channel. The tailored ZMC-IMS membranes with the size-sieving effect can selectively intercept different-sized ions and regulate the transport of different hydration level ions, blocking water migration in electrolytes to support long-time cycling stability. In addition, the localized high-concentration iodide layer triggered by the ZMC-IMS membrane can effectively suppress the crossover of polyiodides by the ionic repulsion. As a result, the Zn-I FBs cell using the ZMC-IMS-based membrane demonstrated high performance and delivered a long cycling lifespan at harsh operation conditions due to retaining water balance and the shuttling-free issue. Furthermore, techno-economic analysis in this work revealed that the ZMC-IMS membrane-enabled Zn-I FBs promise to achieve a competitive levelized cost of storage (LCOS) toward long-life energy storage.

Results

IMS membrane design

Firstly, as shown in Fig. 2a–c, three sorts of IMS (ZIF-8-IMS, MOF-5-IMS, and ZMC-IMS) were synthesized to accommodate different ion-transport channel configurations with various sub-nanopore sizes, respectively. The powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns can verify the successful fabrication of the above molecular sieves (Supplementary Fig. 1)37,38,39. Specifically, according to BET results (Supplementary Fig. 2), the pore size distributions of ionic-molecular sieves showed the quantitative difference that ZIF-8-IMS had a pore size of ≈3 Å, ZMC-IMS had a pore size of ~5.5–6.5 Å and MOF-5-IMS had a pore size of ~12 Å, which were in accord with the previous reports37,38. To optimize the coating layer, the carbon nanotubes (CNT) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were incorporated within the coating layers and functioned as the supporting dispersive framework and the binder (Supplementary Figs. 3–5), respectively, ensuring the uniform dispersion of ionic-molecular sieves. The selective ionic transport modes in these IMS-coated Nafion-based membranes (ZIF-8-IMS membranes, ZMC-IMS membranes, and MOF-5-IMS membranes) and the pristine N117 membrane were investigated using concentration-driven dialysis diffusion tests (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). As shown in Fig. 2d, all four membranes exhibited the same trend, in which the cation transference number through the membrane decreased as the size of the cation increased. Typically, ions exist in their hydrated form for transportation within the electrolyte, wherein the detailed diameters and hydration degree of these three representative cations were K+·(H2O)6 with ~6.62 Å, Na+·(H2O)3 (~7.16 Å), and Zn2+·(H2O)6 ~ 8.60 Å, respectively36,40,41,42. Specifically, MOF-5-IMS membranes showed almost the same ionic selectivity as pristine N117 membranes due to the largest pore size of MOF-5-IMS of ~12 Å. In contrast, ZIF-8-IMS membranes exhibited the lowest metal cation transference number, which can be attributed to the interception of the large hydrated K+·(H2O)6 with the hydration shell diameter (~6.62 Å) by the small subnanometer pore diameter size (<3 Å) of ZIF-8-IMS36. The prepared ZMC-IMS membranes showed selective interception with a slightly decreased transference number of hydrated K+ and highly suppressed transference capability for the hydrated Na+/Zn2+. Notably, the radius of hydrated ion differs with the quantity of water in the solvation shell layer, in which the hydration degree of K+·(H2O)n (n = 1–8) follows a normal distribution (the optimal coordination number: 6, the corresponding diameter: 6.62 Å)40,43,44,45. This result means the small hydrated K+·(H2O)ns (ns = 1–4) with less solvation water could pass through the ZMC-IMS layer to retain a high K+ ionic conductivity. Therefore, the ZMC-IMS-based selective layer exhibited the sieving effect on hydrated K+, owing to tailor-made subnanometer pore frameworks of ZMC-IMS.

a Crystal structure model of ZIF-8-IMS with subnanometer diameter of 3.4 Å, b ZMC-IMS with a subnanometer diameter of 5.5–6.5 Å, and c MOF-5-IMS with subnanometer diameter of ~12 Å. d Cation (K+, Na+, and Zn2+) mobilities calculated using I/V profiles by N117, MOF-5-IMS, ZMC-IMS, and ZIF-8-IMS membranes. e I3− permeability and water migration of N117, MOF-5-IMS, ZMC-IMS and ZIF-8-IMS membranes. f UV-visible spectra of 10 mM KI3 solution after soaking with 50 mg of ZMC-IMS and CNT. g The zeta potential of N117, CNT, and ZMC-IMS membranes saturated by KI1.5 in 1.0 mM KCl solution. h The evolution of bonding energy of I3− interacting with the ZMC-IMS of metal/oxygen active sites and the electrostatic potential (ESP)-mapping of ZMC-IMS (Surface local maximum of ESP are represented as red spheres, and numbers mark out the corresponding ESP values). The details of the optimized structure can be seen in Supplementary Data 1. All error bars represent standard deviations from three independent tests.

To study the permeability of active polyiodide species through the membranes with different pore sizes of the coated molecular sieves, two-compartment H-cells consisting of 2 M KI3 in one cell and deionized water in counterpart cell were used to evaluate by the UV-visible absorption spectra, as schemed in Supplementary Fig. 8. The permeability of I3− in Fig. 2e-left-Y-axis and Supplementary Figs. 9–13 followed the order of N117 (2.11 × 10−5 cm2 h−1) > MOF-5-IMS membranes (3.04 × 10−7 cm2 h−1) > ZMC-IMS membranes (1.68 × 10−7 cm2 h−1) > ZIF-8-IMS membranes (7.66 × 10−8 cm2 h−1). It indicated that all the coating layers could inhibit the crossover issue of the active iodine species across the membrane. Moreover, regarding the unmodified Nafion membrane, it should be noted that although the migration of negatively charged polyiodide species is supposed to be rejected by the Donnan exclusion effect, the crossover would still diffuse through the micropore and swelling channel of the Nafion membrane18. Moreover, to mitigate the influence of osmotic pressure, we employed another H-type cell with a feed reservoir containing a lower concentration of KI3 (0.1 M) and a permeate side filled with supporting salts (0.1 M KCl) to further evaluate the permeability of all membranes. The permeation results obtained from the low osmotic pressure H-cell align with the trends observed in the previous measurements (Supplementary Figs. 14–18), which follow the order of N117 > MOF-5-IMS membranes > ZMC-IMS membranes > ZIF-8-IMS membranes. On the other side, the water migration for 5 days was further compared in Fig. 2e-right-axis and Supplementary Figs. 9–18, which indicated that a decrement in pore size is associated with a proportional reduction in the volume of water migration. Notably, to probe the exact role of the ZMC-IMS, the ionic selectivity, polyiodide permeability, and water migration of CNT-based membranes without containing the ZMC-IMS were comparatively investigated. There were small differences in these parameters of the CNT-based membrane compared with the pristine N117 membranes (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20), further implying the highly selective sieving effect of the ZMC-IMS. According to the above analysis, ZMC-IMS membranes with a well-matched pore size could achieve a balance among the key factors to enable high-performance Zn-I FBs, retaining a high ion conductivity, limiting the Ix− active redox permeability, and restricting the water migration. Thus, the ZMC-IMS with pore size within 5.5–6.5 Å and the derived ZMC-IMS membranes were selected as the prototypical materials for the following investigations.

As clearly shown in Supplementary Fig. 21, the ZMC-IMS featured a rod shape with a uniform elemental distribution. After drop-casting and coating the synthesized ZMC-IMS nanoparticles onto the two sides of the supporting N117 membrane, the smooth ZMC-IMS layer showed a thickness of about 10 ± 1 μm (Supplementary Fig. 22). The successful loading of the ZMC-IMS coating layer can also be demonstrated by XRD results (Supplementary Fig. 23). UV-visible spectra were tested by as-prepared KI3 solutions before and after soaking with ZMC-IMS and CNT (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 24), respectively. UV-visible absorbances associated with I3− (288 nm and 350 nm) decreased more after soaking in ZMC-IMS than in CNT, and slightly increased after soaking for 5 days based on ZMC-IMS20. Moreover, elemental mapping patterns of ZMC-IMS@I3− further demonstrated the absorption of active iodine species (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26). These observations converged to the fact that ZMC-IMS with nanochannel chemistry accommodated a strong polyiodide absorption ability/stability. Consequently, a localized high-concentration iodide layer would be constructed within the ZMC-IMS layer during battery operation. Zeta potential measurements of the N117, CNT, and ZMC-IMS membranes were conducted to examine the electrostatic repulsion of membranes, where the negative zeta potential signifies the prevalence of a negative net charge on the membrane surface46. As displayed in Fig. 2g, all measurements showed negative zeta potentials resulting from the absorbed negatively charged polyiodide in ZMC-IMS (KI1.5-soaked, −74.62 mV) and intrinsic negatively charged functional groups in N117 (KI1.5-soaked, −25.88 mV). Notably, the magnitude of zeta potentials of ZMC-IMS membranes was substantially larger than that of CNT membranes (KI1.5-soaked, −45.65 mV), which suggested that ZMC-IMS membranes had a stronger electrostatic repulsion strength against anions compared to their counterparts.

To further comprehend the adsorption-active sites between polyiodide species and ZMC-IMS, the atomic binding state was explored. In general, metal active sites would be activated by the removal of coordinating solvent molecules, which can be confirmed by the positive shifts of the binding energy of the Zn 2p spectrum in Supplementary Fig. 2747. The negative shifts of binding energy in the high-resolution Zn spectra were observed for ZMC-IMS@I3− compared with activated ZMC-IMS (Supplementary Fig. 28a), implying the occurrence of electronic interaction between ZMC-IMS and adsorbed polyiodide species (Fig. 2h-i). Furthermore, as displayed in Supplementary Fig. 28b, the more positive shifts of binding energy in the high-resolution I 3d spectra were shown for ZMC-IMS@I3− compared with CNT@I3−, which indicated the strong chemical absorption rather than physical absorption between ZMC-IMS and active redox48. The molecular electrostatic potential (ESP) was further employed to analyze the active sites of absorbing I3−(Fig. 2h-ii), where the regions with more positive ESP tend to interact with polyiodides49. The simulated potentials for both the Zn atom (Fig. 2h-i) and O atom (Fig. 2h-iii) with surrounding sites exhibited an electron-deficient solid center, which was conductive to boost the chemical interaction of polyiodide I3− species with ZMC-IMS50. The results can also be demonstrated by calculating the adsorption energy of those active sites, which reflects the magnitude of the interaction ability at different sites. As shown in Fig. 2h-(vi, v) and Supplementary Fig. 29, both metal and oxygen active sites reflected superior polyiodide absorption ability. This detailed investigation highlighted the I3− capability of ZMC-IMS for Zn-I FB systems, effectively constructing a localized high-concentration iodide layer to prevent the crossover of the polyiodide for Zn-I FBs.

Restrained hydrated ion clusters migration by ZMC-IMS membrane

Due to ions existing in hydration states, the transport of hydrated ions would be accompanied by substantial water migration, thereby controlling the coordination number of hydrated ions across membranes, which can inhibit electrolytes out-of-balance33,34. Therefore, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were employed to calculate the representative smallest hydrated metal ions (K+·(H2O)n, n = 1–8) transport through Nafion and ZMC-IMS@Nafion membranes. MD simulations clearly showed the K+·(H2O)n clusters could transport across the Nafion membranes, as shown in snapshots of Fig. 3a35. In contrast, the ZMC-IMS@Nafion membranes with the tailored subnanometer pores of ZMC-IMS (Supplementary Fig. 30) could block the large hydrated K+ clusters (K+·(H2O)nl, nl = 5–8) (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c–f showed the radial distribution function and statistical distribution of the oxygen atoms on water molecules surrounding K+ ions, respectively. Specifically, it can be found that K+·(H2O)n (n = 1–8) clusters can be easily diffused into the permeate side of the Nafion membranes (Fig. 3c, e), corresponding to barely selective interception of the hydrated ions and resulting in a large amount of H2O migration during FBs operation. In comparison, K+·(H2O)nl (nl = 5–8) clusters with larger solvation shells in ZMC-IMS@Nafion membranes were confined to the feed side, where small hydrated K+ clusters (K+·(H2O)ns, ns = 1–4) were distributed in the whole systems due to the free-transport across the ZMC-IMS@Nafion membranes (Fig. 3d, f), indicating the size-selective permeability of the hydrated H2O number by the ZMC-IMS layer.

Snapshots of a Nafion, and b ZMC-IMS@Nafion membranes at different times in an electric field I of 4.5 V/nm. Blue spheres represent K+ and red spheres represent H2O. Radial distribution function, corresponding coordination number, and statistical distribution of hydrated K+ clusters at 300 ps using c, e Nafion, and d, f ZMC-IMS@Nafion membrane. The details of the molecular dynamics trajectories can be seen in Supplementary Data 2. g SAXS profiles of N117, CNT, and ZMC-IMS membranes (d is the Bragg spacing). Two-dimensional scattering pattern of h N117, and I ZMC-IMS membranes. Schematic illustrations of hydrated K+ (K+·(H2O)n) clusters transport mechanisms across j N117, and k ZMC-IMS membranes based on the surface zone, represented as nanochannels for simplicity. l ZMC-IMS membranes can freely transport the small hydrated K+ (K+·(H2O)ns) clusters while significantly hindering the migration of large hydrated K+ (K+·(H2O)nl) clusters.

The small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was subsequently conducted to probe the hydrated-ion cluster size inside the N117, CNT, and ZMC-IMS membranes35. The SAXS pattern of N117 and CNT membranes (Fig. 3g) both showed two scattering ionomer peaks at q ≈ 0.66 nm−1 and q ≈ 1.8 nm−1, translating to K+·(H2O)x clusters with larger sizes for N117 and CNT membranes, respectively, according to the Bragg equation34,51,52,53. In contrast, there was no signal of large K+·(H2O)nl clusters observed on ZMC-IMS membranes, only the existence of small K+·(H2O)ns clusters, which was due to the ionic-selective limitation of the ZMC-IMS layer. Meanwhile, the two-dimensional SAXS patterns (Fig. 3h, i, and Supplementary Fig. 31) are isotropic for both membranes, revealing an isotropic dispersion and orientation of heterogeneities within both polymers. Therefore, ZMC-IMS membranes exhibited strong interception of the largely hydrated ions to prevent H2O migration compared with other counterparts, which is in accordance with MD simulations.

The resistance of the membranes against water uptake is another critical parameter in maintaining the structural integrity of the membrane to maintain stable ion transport. The swelling behaviors of ZMC-IMS and N117 membranes were explored (Supplementary Fig. 32). Specifically, the ZMC-IMS membrane showed a much lower water uptake and swelling ratio than N117, which can be attributed to the uptake suppression of water clusters by the ZMC-IMS layer. Moreover, the hydrophobic feature of the ZMC-IMS layer also contributed to the anti-swelling properties of the IMS-coated membranes, as verified by the larger contact angle of ZMC-IMS membranes compared to that of pristine N117 (Supplementary Fig. 33). The above results illustrated the water clusters would aggregate in the ionic conduction channels and swell the Nafion structure during the transport process of the hydrated ions (Fig. 3j). On the contrary, the ZMC-IMS-based membrane could endow the size selectivity on the hydrated ions as charge carriers of different hydrated degree (Fig. 3k, l), which could selectively block the transportation for largely hydrated ions with the coordinated water number over 4. Therefore, according to the microscopic analysis of the transport process of hydrated ions, the ZMC-IMS membrane with tailor-made pores could effectively restrict larger hydrated K+ through the size-sieving effect to relieve the water migration, favorably achieving the long-duration Zn-based FBs under high areal capacity/SOC conditions (Fig. 3j–l).

Electrochemical performance

The electrochemical performance of flow batteries with ZMC-IMS membranes was evaluated by constructing a prototype Zn-I FBs, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 34. During 80 cycles of operation (Fig. 4a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 35), stable CE and energy efficiency (EE) were observed under different working currents for the flow-mode Zn-I FBs using ZMC-IMS membranes. It should be noted that the electrochemical performance of Zn-I FBs was evaluated at the high-concentration polyiodide-based posolyte. The volumetric energy density of the Zn-based FBs was high at high SOC conditions, which delivered a high volumetric capacity of 53.2 Ah L−1posolyte (5 mL 6 M KI + 3 M ZnBr2 | 5 mL 3 M ZnBr2 + 3 M KCl at 50% SOC), and the corresponding areal capacity was 66.4 mAh cm−2. In contrast, as displayed in Supplementary Fig. 36, the N117-based FBs exhibited low rate capability and enlarged voltage polarizations at the 21st cycle once the working currents increased to 20 mA cm−2. Thus, the reversible cycling with a power density range (10–50 mA cm−2) under flow-states exhibited the promising potential based on ZMC-IMS membranes for satisfying stable large-scale energy storage applications across power requirements.

a CE and EE of Zn-I FB cell (5 ml of 6 M KI + 3 M ZnBr2 | ZMC-IMS membrane | 5 ml of 3 M ZnBr2 + 3 M KCl, 4 cm2 membrane area) under 10, 20, 30 and 50 mA cm−2 at 50% SOC. The inset shows the prototype of Zn-I FBs flow-cell stack (5 ml of electrolytes, 4 cm2 membrane area, for illustration). b Galvanostatic cycling of Zn-I FBs cell with ZMC-IMS and pristine N117 membranes. c Long cycling of high-energy Zn-I FB flow-cell (5 mL of 6 M KI + 3 M ZnBr2 | ZMC-IMS membrane | 5 mL of 3 M ZnBr2 + 3 M KCl, 4 cm2 membrane area) at 30 mA cm−2 with the designated discharge duration (energy to power ratio, E/P) of 2.23 h. The insets show the representative voltage profiles over cycling, CE, and volumetric/areal capacity during 500 cycles (2050 h). d Self-discharging performance of Zn-I FB flow-cell after charging to 50% SOC for static flowing 24 h and 168 h. e Comparison of Zn-based FBs in terms of CE, working time, and areal/volumetric capacity, where the symbol size and color scale show the corresponding areal capacity and volumetric capacity, respectively. All battery tests were charged from 0% to either 20% or 50% SOC.

The cycling performance of the Zn-I FB with ZMC-IMS membranes was further evaluated at 20%-SOC of the iodine posolyte. The as-developed Zn-I FBs delivered a stable charge-discharge operation over 1000 cycles at 30 mA cm−2 with stable CE (average >99.0%), realizing the volumetric capacity of 21.4 Ah L−1posolyte (Supplementary Fig. 37). Furthermore, we increased the energy of the flow cell by increasing 50%-SOC (5 mL 6 M KI + 3 M ZnBr2 |5 mL 3 M ZnBr2 + 3 M KCl), the scale-up ZMC-IMS membranes-based Zn-I FBs with a designated charging areal capacity of 67 mAh cm−2 and operated stably for 500 cycles (>2050 h) with no obvious CE decay at an average of 99.0%, as demonstrated in Fig. 4c. This flow system demonstrated long cycling calendar life even under a high volumetric/areal capacity (53.2 Ah L−1posolyte/27.66 Wh L−1system, 66.4 mAh cm−2). Compared to the CNT membrane and the N117 membrane-based Zn-I FBs under the same working condition, both FBs showed inferior CE (CNT-based FBs: ~98.21%; N117-based FBs: ~97.14%) with severe capacity loss, lower discharging volumetric capacity (CNT-based FBs: ~51.76 Ah L−1posolyte; N117-based FBs: ~52.38 Ah L−1posolyte) and short cycle lifespan (CNT-based FBs: ~500 h; N117-based FBs: ~170 h), respectively (Supplementary Figs. 38–40). Those results can be demonstrated by the SEM and XRD patterns after cycles (Supplementary Figs. 41 and 42), wherein the capacity loss and pH rise induced by crossover and a large number of water migrations can lead to severe side reactions, resulting in the rapid cell failure of Zn-I FBs without ZMC-IMS membranes14,54. Benefiting from the sub-nanopore chemistry of MOF materials, the ZMC-IMS membrane exhibited a favorable and uniform Zn deposition at the carbon felt-membrane interface. Notably, the reduced Arrhenius dependence of charge transfer resistance in symmetric cells by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements (Supplementary Figs. 43 and 44) suggested possible modulation of Zn desolvation processes, potentially contributing to dendrite suppression55. Therefore, as shown in the results above, the high CE and cycle stability in ZMC-IMS membranes-based systems illustrated that the ZMC-IMS layer had a high restriction function on polyiodides and an excellent suppression effect on water migration for stable cycling, thereby endowing a reversible plating/stripping process of Zn-based anodes and conversion reaction of polyiodide-based cathode for realizing high-performance Zn-I FBs with long life.

The crossover issue of the active polyiodide was investigated by the self-discharge performance of Zn-I FBs at 50% SOC applying different membranes (Fig. 4d). Specifically, no apparent CE decrement was observed for ZMC-IMS membranes after different flowing periods (99.5% after 24 h; 98.5% after 168 h), while the CE dramatically decrease to 93.6% and 84.4% after static flowing 24 h and 168 h for N117 membranes (Fig. 4d). The results could be assigned to the localized high-concentration iodide layer in ZMC-IMS layer to strongly electrostatic repel the charged iodide species in the posolyte, effectively alleviating the crossover issue to achieve the high-performance Zn-I FBs. To probe the origin of the electrochemical performance of the ZMC-IMS-based FBs, the ZMC-IMS coating layer was subjected to 100 times mechanical bending, preserving a uniform and dense structure (Supplementary Fig. 45). In addition, no powder residuals were observed in the reservoirs after a 500 h water-flushing test in a flow-cell configuration with flow rates ranging from 20 to 60 ml min−1 (Supplementary Fig. 46). The mechanical stability of ZMC-IMS membranes could support electrochemical stability in Zn-I FBs. On the other side, regarding the water migration of the N117-based FBs, the volume of negolyte decreased continuously during the long cycling while the volume of posolyte increased substantially over 96 h (Supplementary Fig. 47). In contrast, the volumes of both posolyte and negolyte showed a slight change over 1500 h in using ZMC-IMS membranes for Zn-I FBs testing (Supplementary Fig. 48). It is consistent with the above rate and cycling performance that the electrochemical performance of the ZMC-IMS membrane-based FBs could be attributed to the effective mitigation on the crossover and water migration issue of the electrolytes. Thus, the Zn-I FBs assembled with ZMC-IMS membranes performed good battery performances, which were evaluated in more practical conditions by taking these vital parameters together, i.e., CE, volumetric/areal capacity, and working lifetime, compared with those previously reported works based on Zn-polyhalide FBs in Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 1.

Techno-economic cost analysis based on emerging AFBs

Considering the high areal capacity and long-life performance of Zn-I FBs with ZMC-IMS-based membranes, we simulated and calculated LCOS, wherein LCOS pertains to the normalized lifetime cost to cumulative delivered electricity4,18. This metric holds significant importance in assessing the commercialization potential of demonstrated systems and is closely linked to specific application durations. Lu’s group and Schmidt’s group outlined the methodology for LCOS calculation, where the LCOS is closely linked to specific application durations, as elaborated in Supplementary Tables 2–7 and Supplementary Figs. 49–53. Thus, we investigated LCOS variations based on discharge duration (or energy-to-power ratio, E/P) for three emerging zinc-bromine (Zn-Br) FBs, zinc-iron (Zn-Fe) FBs, and Zn-I FBs. Meanwhile, the promising all-organic 2,6-DBEAQ (4,40-((9,10-anthraquinone-2,6-diyl)dioxy) dibutyrate) redox flow batteries (AQFBs) were presented as the reference. Notably, the reported AFB testing durations in the literature are much shorter than the projected shelf life derived from decay rate measurements. Since the LCOS is calculated based solely on projected shelf life, it offers initial comparisons for nascent laboratory-scale AFB prototypes (Fig. 5a), but it is unsuitable for direct benchmarking against the mature vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs). Thus, the LCOS assigned to the commercialized VRFBs serves as a visual reference, which was intended for contextual understanding rather than direct comparison with laboratory-based AFBs.

a Bulk energy storage LCOS analysis of Zn-Br FBs62, Zn-Fe FBs63, and Zn-I FBs as a function of discharge duration E/P (180 cycles per annum (p.a.), interest rate 8%, electricity price (Electricity-P) USD-20 MWh−1). The gray zone indicates the price range for commercial VRFBs4,56; the dashed plot indicates the price for AQFBs58; the black arrows indicate E/P greater than 18 h (Supplementary Table 2). b Breakdown of the LCOS with a discharge duration of 18 h for Zn-Br FBs62, Zn-Fe FBs63, and Zn-I FBs, including electricity cost (E-Cost), operation and maintenance (O&M) cost, and investment cost. The gray zone indicates the price range for commercial VRFBs4,56; the dashed plot indicates the price for AQFBs58. c normalized installation cost breakdown including energy cost (CE, including chemical costs and tank cost), power cost (CP), balance-of-plant cost (Cbop), and additional cost (Cadd) for 270 kWh/15 kW (upper) and 3600 kWh/15 kW (lower) Zn-I FB systems. The left (light color) and right (dark color) charts represent the present and projected future costs of the Zn-I FB systems, respectively. Considering the extended cycle life demonstrated by our Zn-I FBs, a 20-year project lifetime is adopted as a benchmark in the LCOS analysis, along with an 8% annual discount rate to account for discounted energy delivery over time, thereby underscoring the advantages of our developed Zn-I FB systems.

Figure 5a displays LCOS estimations for three emerging aqueous Zn-based FBs across a range of durations (1–23 h, 180 cycles per year) suited for bulk long-duration energy storage. Firstly, the LCOS of commercial VRFBs was indicated as a reference zone, summarized by Schmidt’s group and Zakeri’s group4,56. All systems exhibited sharp LCOS reduction for short durations (1–2 h), stabilizing asymptotically for more extended periods (>10 h) due to the diminishing power cost percentage. The developed Zn-I FBs in this work offered advantages in low energy cost and long operating lifetime. Still, they faced drawbacks in power cost due to the modest current density. As depicted in Fig. 5a, Zn-I FBs maintained lower LCOS than the other Zn-based FB systems across large energy/power (E/P) ratios, i.e., long duration energy storage, due to their prolonged calendar life from low decay rate and energy cost. The LCOS of Zn-I FBs was larger than Zn-Fe FBs before the duration of 4 h, which was due to the short duration of operation being greatly influenced by power costs. However, Zn-I FBs have become competitive and have lower LCOS at long durations exceeding 11 h compared to AQFBs. The cost analysis indicated that the developed Zn-I FBs remained competitive for long-duration energy storage applications (>11 h). For a detailed breakdown, Fig. 5b presents the LCOS analysis of Zn-I FBs compared with ZnBr FBs and Zn-Fe FB systems using an E/P ratio of 18 h, focused on bulk storage applications. The result demonstrated the promising potential of constructing low-cost Zn-I FB systems for large-scale long-duration energy storage.

We further proceed to breakdown the total initial installed cost of the Zn-I FB systems for both short-duration (270 kWh/15 kW, 22 h) and long-duration (3600 kWh/15 kW, 10 days) energy storage applications, highlighting the cost share of each component (Fig. 5c)18,57. Specifically, in the case of the current Zn-I FBs configuration, the power cost represented 82.5% of the total capital cost for the short-duration application, which decreases to 31.4% for the long-duration application. This calculated analysis emphasized the need to reduce the power cost of Zn-I FBs for short-duration storage, which requires improvements in reducing the cost of the Nafion-based membrane. Furthermore, we project a lower cost estimation of the energy storage system shown in Fig. 5c (future Zn-I FBs), incorporating two improvement directions for the future: (1) using a lower cost non-fluorinated membrane with higher ionic conductivity compared to Nafion (i.e., the porous membrane with 1.0 Ω cm2 in K+ conductive electrolytes at 20-fold times lower costs than Nafion membrane), (2) optimizing the volumetric ratio of positive/negative electrolyte ratio to improve the utilization rate of electrolytes (Supplementary Fig. 51)58. With these enhancements, the total normalized installed cost could decrease by 81.4% compared to the current laboratory-scale Zn-I FB systems of an 18-h duration. The power cost accounts for only 16.3% of the total cost (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Additionally, this work showed that the Zn-I FBs flow cells utilizing the IMS membrane exhibited high cycling stability with long discharge/charge durations (~18 h for each set) (Supplementary Fig. 53), further supporting their applicability for long-duration energy storage. Therefore, the developed Zn-I FB systems offer the long-duration storage required for cycling stability and the potential for a cost-effective levelized storage cost in various large-scale energy storage applications.

Discussion

In summary, we developed a ZMC-IMS membrane with precise pore sizes to match the transport of ions within a 6.5 Å diameter, thereby maintaining high ion conductivity and mitigating the crossover of active materials. The size-tailored pores with sub-nanochannels in the ZMC-IMS layer feature the size-sieving effect, selectively intercepting largely hydrated K+(H2O)n (n > 4), which relieved the volume imbalance of electrolytes induced by water migration. In addition, the ZMC-IMS layer can chemically confine the polyiodides inside the sub-nanochannel to construct a localized high-concentration iodine layer to electrostatically repulse the active iodine species to resolve the crossover issue. Correspondingly, this work demonstrated a full-flow prototype Zn-I FB system that accommodated stable cycling over 3 months (500 cycles) with a high areal/volumetric capacity of 66.4 mAh cm−2/53.2 Ah L−1posolyte/27.66 Wh L−1system and high CE of 99% under 50% SOC. The as-developed Zn-I FB systems delivered a low self-discharge rate in retaining a high CE of 98.5% after static flowing for 3 days. Meanwhile, techno-economic cost analysis uncovered that the ZMC-IMS membranes-enabled Zn-based FBs showed competitive LCOS for large-scale energy storage. Our work offers insights into controlling water transport behaviors for realizing long-life Zn-based FBs as long-duration energy storage plants.

Method

Materials

All chemicals were used as received. Zinc bromide (ZnBr2, ≥98%), zinc acetate (Zn(Ac)2, ≥99%), potassium chloride (KCl, ≥99%), potassium iodide (KI, ≥99.5%), sodium chloride (NaCl, ≥99.5%), potassium hydroxide (KOH, ≥98 %), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95%–98%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30 wt% in H2O), iodine (I2, ≥99%), zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, ≥99%), 2-methylimidazole (≥98%), trimesic acid (H3BTC, 95%), triethylamine (AR, ≥99.5%), trimesic acid (AR, ≥98%), terephthalic acid (AR, ≥99.5%), N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, AR, ≥98%), ethanol (AR, ≥99.5%), methanol (AR, ≥99.5%) and 1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidinone (NMP, AR, ≥99%) were received from Sigma-Aldrich. Graphite felt (3.0 mm, carbon ≥99%, bulk density 0.12–0.14 g cm−2) was received from Yi Deshang Carbon Technology. Nafion membrane (N117, Dupont) was received from Shanghai Hesen Electric. Carbon nanotubes were received from XFNANO Technology. Ti foil (99.9%, 100 μm) was obtained from Kangwei Metal. Zn foil (200 μm, 99.99%) was purchased from Chenshuo Metal. PVDF (HSV900) binder was received from Taiyuan Lizhiyuan Batteries.

Synthesis of ZMC-IMS

ZMC-IMS crystals were modified and synthesized by a hydrothermal method. In a typical procedure, 0.872 g of Zn(Ac)2 was dissolved in 25 mL of mixed solution (DMF: ethanol: DI H2O) and sonicated for 20 mins. 1 g of H3BTC was dispersed into 25 mL of the same mixed solution (DMF: ethanol: DI H2O) and sonicated for 20 mins. Afterward, these two solutions were mixed and stirred for another 20 mins. 0.5 mL of triethylamine was slowly added to the above solution and then stirred for 24 h. The mixture was sealed into a PTFE-lined autoclave and then transferred into a preheated oven at 80 °C for 16 h under static conditions. After cooling to room temperature, the product was centrifuged and washed with DMF, methanol, and DI H2O three times each and finally dried at 60 °C under vacuum for 16 h. The obtained white product was then used as the ZMC-IMS. The activated ZMC-IMS was calcined at a low temperature of 150 °C for 3 h in nitrogen with a heating rate of 2 °C min−1.

Synthesis of ZIF-8-IMS37 or MOF-5-IMS38

A solid mixture of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.525 g) and 2-methylimidazole (0.015 g) was dissolved in DMF (9 mL) in a 12 mL Teflon-capped vial, which was heated at a rate of 2 °C min−1 to 130 °C, held at this temperature for 24 h, and then cooled at a rate of 5 °C h−1 to room temperature. Colorless polyhedral crystals were filtered from the reaction mixture, washed with methanol 3 times, and dried in air.

Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (1.19 g) and terephthalic acid (0.34 g) were dissolved in 40 ml of DMF during vigorous stirring at room temperature. Three drops of H2O2 aqueous solution (30 wt%) were added to the solution. Triethylamine (2.3 ml) was slowly added dropwise to the above solution under vigorous agitation for 1 h. The white product was collected by repeated filtering and thorough washing with DMF three times. The sample was degassed firstly at room temperature for 6 h, then heated to 180 °C at a heating rate of 2 °C min−1 and held at this temperature for 12 h under degassing in vacuum.

Preparation of ZMC-IMS membranes

Prior to use, commercial Nafion membranes underwent a series of pretreatment steps. First, they were immersed in 5% H2O2 at 80 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the membranes were treated with 5% H2SO4 under the same temperature for another hour. To convert the H+-form Nafion into the K+-conductive type, the membranes were further incubated in 1 M KOH aqueous solution at 80 °C for 2 h. After each step, the membranes were thoroughly rinsed with DI water for 30 mins to remove residual chemicals. The ZMC-IMS membrane was fabricated via drop-casting a slurry consisting of ZMC-IMS: CNT: PVDF at a mass ratio of 8:1:1 in NMP solvent (see Supplementary Fig. 2). The slurry was homogenized by sonication before application. The loading of ZMC-IMS on each side of the N117 membrane was controlled by adjusting the volume of slurry deposited, targeting a uniform density of 1 mg·cm−2. The cast membrane was dried at 60 °C for 3 h and then rehydrated in DI water before testing. For comparative purposes, additional membranes were prepared by substituting ZMC-IMS with either ZIF-8-IMS or MOF-5-IMS in the slurry. All other preparation conditions remained consistent with those used for the ZMC-IMS membrane.

Permeability

The permeability of KI3 through various membranes was assessed by tracking changes in UV-visible spectra on the permeate side during H-cell experiments (Supplementary Fig. 6). The feed chamber was charged with 2 M KI3 solution, and the permeate compartment was filled with deionized water. A circular symmetric transport channel connected the two reservoirs, which were separated by the test membrane. Given the low concentration of KI3 accumulated in the permeate compartment, the concentration in the feed was assumed to remain approximately constant, and the flux of KI3 across the membrane was treated as steady—consistent with a pseudo-steady-state condition throughout the experiment18.

where V (ml) denotes permeate volume; cA and cB(t) (mol L−1) represent the KI3 concentrations in the feed/permeate compartments, respectively; A (cm2) refer to the effective area and and L (cm) is a thickness of the membrane; P (cm2 min−1) is the membranes permeability; t (min) and t0 (min) correspond to the elapsed time and the time lag, respectively. The permeability P was calculated from the slope of the linear fit between −ln(1-cB(t)/cA) and t.

Absorption ability of Zn-MOF-CJ3 by UV-visible spectra

For adsorption analysis, 50 mg ZMC-IMS or CNT powders were vortex-mixed with 1 mL KI3 solution (10 mM KI: I2 = 1:1). After overnight agitation and centrifugation, supernatants underwent UV-Vis spectroscopy (PerkinElmer Lambda 1050+), with quantification against Beer’s law plots from 0.1–1 mM KI3 standards.

Zeta potential measurement18

The zeta potentials of the membranes were determined via streaming potential measurements on a SurPASS instrument (Anton Paar), with subsequent analysis performed using a Malvern Nano ZS90 system. The zeta potential (ζ) was evaluated according to the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski (H–S) equation:

where dU/dp represents streaming potential (U)-pressure (p) slope, η denotes the viscosity of the electrolyte, ε and ε0 are the permittivity of the electrolyte and vacuum, respectively, and κ refers to the conductivity of the electrolyte. Prior to zeta potential measurement, the N117, CNT, and ZMC-IMS membranes were equilibrated in 0.5 M KI1.5 solution for 48 h. Afterward, the samples were thoroughly rinsed with DI water to remove residual electrolytes and then dried under dynamic vacuum at 40 °C. A 1 mM KCl aqueous solution was used as the standard electrolyte during streaming potential testing.

Water uptake and swelling performance

Prior to measurement, fully hydrated N117 and ZMC-IMS membranes were immersed in DI water at the specified temperature for at least 24 h. Fully dried membrane samples were obtained by vacuum drying at 80 °C for more than 48 h. The water uptake (φ) was calculated as the weight percentage of absorbed water relative to the dry membrane:

where mh and md represent the masses of the hydrated and dry membranes, respectively. The hydrated mass was measured immediately after removing surface moisture with Kimwipes. The swelling ratio was defined based on the length change of the membrane upon hydration:

where lh and ld correspond to hydrated and dry membrane lengths.

Ion transference numbers25

The ion-transport numbers for the cation-exchange membranes were investigated using CHI electrochemical testing unit (760E). The V-I profile was tested by two Ag/AgCl reference electrodes when the membrane was sandwiched between two cells soaking with different salts (KCl, NaCl, and ZnCl2) concentration gradients (0.1 M||0.01 M, Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, reversal potential (Vrev) can be calculated as the following equation:

Where Vrev is the measured reversal potential; R is the gas constant; T is the temperature of the solution; n is the charge number; F is the Faraday constant; acis and atrans are the activity of the ionic species (refer to CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics); ccis and ctrans are the concentration of ionic species45.

Electrochemical characterization

The posolyte consisted of 6 M KI and 3 M ZnBr2 dissolved in DI H2O, while the negolyte contained 3 M ZnBr2 and 3 M KCl in DI H2O. For the Zn-I flow battery assembly, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) frames were used to form flow channels and secure pre-treated graphite felt electrodes with a geometric area: 4.0 cm2 (2 × 2 cm2) and a thickness of 2.0 mm (Supplementary Fig. 22). Electrolyte circulation was driven by a peristaltic pump (Chuang Rui Precision Pump), establishing continuous flow through the electrodes. All cells were charged from 0% to either 20% or 50% state of charge (SOC). Cycling performance was evaluated using three parallel cells. The system-level energy density was calculated as follows:

EIS was employed using a CHI 760E workstation at open-circuit potential (10 mV amplitude, 100 kHz–0.1 Hz range), with triplicate measurements.

Galvanostatic tests were conducted using a LAND CT2001A battery testing system at room temperature (23–25 °C). Current densities ranged from 10 to 50 mA cm−2. Charging was performed at a fixed capacity (107 mAh or 268 mAh), and discharging terminated at a cutoff voltage of 0.1 V. The theoretical capacity was determined based on the iodide content in the catholyte, which acted as the capacity-limiting species.

Polarization measurements determined area-specific resistance after charging to 50% SOC at 10 mA cm−2, followed by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) from OCV to 0 V (100 mV s−1 scan rate).

Characterizations

The distribution of pore size was tested by BET (Micromeritics ASAP 2460). The crystal structure was studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD, X’Pert Pro MPD, Philips, Holland) using Cu Kα as the radiation source under 40 kV and 40 mA. Morphologies were probed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 450 FEG SEM). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra were recorded on a photoelectron spectrometer (ESCALAB 250, Thermo Scientific, America), where the binding energy (BE) of the elements was calibrated by the BE of C 1 s (284.60 eV).

Small-angle X-ray scattering18,35

SAXS data were collected using a Xeuss 2.0 instrument (Xenocs) with an incident X-ray wavelength of λ = 0.154 nm. SAXS/wide-angle X-ray scattering patterns were recorded in a q range of 0.1 nm−1 < q < 10 nm−1, where q = (4πsin θ)/λ is the length of the scattering vector and 2θ is the scattering angle. On the basis of Bragg’s law d = 2π/q, where d is the hydrated K+ cluster size in the nanodomains. Both samples of N117, CNT, and ZMC-IMS membranes were soaked in a 0.1 M KCl solution and then taken out of fully hydrated K+ states for SAXS tests. The coating layer on CNT and ZMC-IMS membranes was removed with Kimwipes immediately before the experiment to probe the information on the membrane substrates.

DFT calculation59

All the computations were conducted based on the density functional theory (DFT) using the Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package (CASTEP) code of the Materials Studio 2019 software. The generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional was used to describe the electronic exchange and correlation effects. The kinetic-energy cutoff was set as 500 eV. The geometry optimization within the conjugate gradient method was performed with forces on each atom less than 0.05 eV/Å. Additionally, the convergence thresholds for energy and force were set to 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å, respectively. The adsorption of iodine species on the ZMC-IMS is modeled by placing the I3− on different active sites. The Brillouin zone was sampled by a y k-point mesh of 1 × 1 × 1. The binding energy of the configuration (Ebind) was calculated by the following equation:

where EA, EB, and EAB respectively represent the energies of A (I3−) and B (ZMC-IMS) and the complex energy, a negative value of Ebind indicates that the process is an exothermic reaction, and a high negative value corresponds to a stronger interaction, which indicates more heat release and a more stable product.

MD simulations

Two distinct membrane-electrolyte systems were modeled: (1) a Nafion membrane and (2) a Nafion membrane modified with ZMC-IMS (2 × 2 × 1 dimensions). Both systems featured dual bulk solution compartments - the left chamber contained 6 M KI and 3 M ZnBr₂ electrolyte, while the right chamber held pure water, with 4728 water molecules distributed collectively. Each Nafion membrane comprised five polymer chains (10 repeating units per chain) at a 20.6 hydration level, with hydronium counterions ensuring charge neutrality60.

MD simulations were performed using LAMMPS to analyze ion-transport mechanisms61. Following energy minimization, systems underwent >4 ns equilibration at 300 K. Subsequently, K+ migration through membranes was accelerated by applying a 4.5 V/nm electric field to enable practical computation times. Trajectory analysis generated radial distribution functions and coordination numbers, with a harmonic bond potential (equilibrium distance: 0.28 nm) maintaining consistent hydration shells around K+ ions. This enhanced field strength facilitated data acquisition while preserving mechanistic insights into ion permeation behavior.

Cost modeling of the flow batteries

The LCOS was estimated using the online tool available at www.EnergyStorage.ninja (accessed on 5 May 2023). The energy normalized installed cost (USD kWh−1) for Zn-I FBs was derived based on data reported by Lu’s group or Darling’s group4,18. Detailed parameters and assumptions employed in the cost analysis are provided in Supplementary Tables 2–7.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are presented in the Manuscript and Supplementary Information or are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Huskinson, B. et al. A metal-free organic–inorganic aqueous flow battery. Nature 505, 195–198 (2014).

Lin, K. et al. Alkaline quinone flow battery. Science 349, 1529–1532 (2015).

Green, M. A. & Bremner, S. P. Energy conversion approaches and materials for high-efficiency photovoltaics. Nat. Mater. 16, 23–34 (2017).

Schmidt, O., Melchior, S., Hawkes, A. & Staffell, I. Projecting the future levelized cost of electricity storage technologies. Joule 3, 81–100 (2019).

Amini, K., Shocron, A. N., Suss, M. E. & Aziz, M. J. Pathways to high-power-density redox flow batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 3526–3535 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Development of flow battery technologies using the principles of sustainable chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 6031–6074 (2023).

Malik, R. Flow battery solvents: looking deeper. Joule 1, 425–427 (2017).

Sawant, T. V., Yim, C. S., Henry, T. J., Miller, D. M. & McKone, J. R. Harnessing interfacial electron transfer in redox flow batteries. Joule 5, 360–378 (2021).

Yao, Y., Lei, J., Shi, Y., Ai, F. & Lu, Y.-C. Assessment methods and performance metrics for redox flow batteries. Nat. Energy 6, 582–588 (2021).

Perry, M. L., Rodby, K. E. & Brushett, F. R. Untapped potential: the need and opportunity for high-voltage aqueous redox flow batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 7, 659–667 (2022).

Weng, G.-M., Li, Z., Cong, G., Zhou, Y. & Lu, Y.-C. Unlocking the capacity of iodide for high-energy-density zinc/polyiodide and lithium/polyiodide redox flow batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 735–741 (2017).

Xie, C., Zhang, H., Xu, W., Wang, W. & Li, X. A long cycle life, self-healing zinc-iodine flow battery with high power density. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11171–11176 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. An all-aqueous redox flow battery with unprecedented energy density. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 2010–2015 (2018).

Xie, C., Liu, Y., Lu, W., Zhang, H. & Li, X. Highly stable zinc–iodine single flow batteries with super high energy density for stationary energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1834–1839 (2019).

Yang, J., Song, Y., Liu, Q. & Tang, A. High-capacity zinc–iodine flow batteries enabled by a polymer–polyiodide complex cathode. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 16093–16098 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Accelerating the dissolution kinetics of iodine with a cosolvent for a high-current zinc–iodine flow battery. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 14090–14097 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Act in contravention: a non-planar coupled electrode design utilizing “tip effect” for ultra-high areal capacity, long cycle life zinc-based batteries. Sci. Bull. 66, 889–896 (2021).

Li, Z. & Lu, Y.-C. Polysulfide-based redox flow batteries with long life and low levelized cost enabled by charge-reinforced ion-selective membranes. Nat. Energy 6, 517–528 (2021).

Zhang, L., Feng, R., Wang, W. & Yu, G. Emerging chemistries and molecular designs for flow batteries. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 524–543 (2022).

Li, B. et al. Ambipolar zinc-polyiodide electrolyte for a high-energy density aqueous redox flow battery. Nat. Commun. 6, 6303 (2015).

Machado, C. A. et al. Redox flow battery membranes: improving battery performance by leveraging structure–property relationships. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 158–176 (2020).

Yuan, Z., Zhang, H. & Li, X. Ion conducting membranes for aqueous flow battery systems. Chem. Commun. 54, 7570–7588 (2018).

Xiong, P., Zhang, L., Chen, Y., Peng, S. & Yu, G. A chemistry and microstructure perspective on ion‐conducting membranes for redox flow batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24770–24798 (2021).

Lu, W. & Li, X. Advanced membranes boost the industrialization of flow battery. Acc. Mater. Res. 4, 681–692 (2023).

Yuan, Z. et al. Low-cost hydrocarbon membrane enables commercial-scale flow batteries for long-duration energy storage. Joule 6, 884–905 (2022).

Xia, Y. et al. Polymeric membranes with aligned zeolite nanosheets for sustainable energy storage. Nat. Sustain. 5, 1–12 (2022).

Tan, R. et al. Hydrophilic microporous membranes for selective ion separation and flow-battery energy storage. Nat. Mater. 19, 195–202 (2020).

Kong, D. et al. N‐CNTs‐based composite membrane engineered by a partially embedded strategy: a facile route to high‐performing zinc‐based flow batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301448 (2023).

Dai, Q. et al. Thin-film composite membrane breaking the trade-off between conductivity and selectivity for a flow battery. Nat. Commun. 11, 13 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. Efficient metal ion sieving in rectifying subnanochannels enabled by metal–organic frameworks. Nat. Mater. 19, 767–774 (2020).

Wang, P. et al. Ultrafast ion sieving using nanoporous polymeric membranes. Nat. Commun. 9, 569 (2018).

Fu, L., Yang, Z., Wang, Y., Li, R. & Zhai, J. Construction of metal‐organic frameworks (MOFs)–Based membranes and their ion transport applications. Small Sci. 1, 2000035 (2021).

Sukkar, T. & Skyllas-Kazacos, M. Water transfer behaviour across cation exchange membranes in the vanadium redox battery. J. Membr. Sci. 222, 235–247 (2003).

Schmidt-Rohr, K. & Chen, Q. Parallel cylindrical water nanochannels in Nafion fuel-cell membranes. Nat. Mater. 7, 75–83 (2008).

Kim, R. et al. Scaling the water cluster size of Nafion membranes for a high performance Zn/Br redox flow battery. J. Membr. Sci. 564, 852–858 (2018).

Chao, D. et al. Roadmap for advanced aqueous batteries: from design of materials to applications. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba4098 (2020).

Hobday, C. L. et al. Understanding the adsorption process in ZIF-8 using high pressure crystallography and computational modelling. Nat. Commun. 9, 1429 (2018).

Li, Y. & Yang, R. T. Significantly enhanced hydrogen storage in metal− organic frameworks via spillover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 726–727 (2006).

He, J. et al. Three metal-organic frameworks prepared from mixed solvents of DMF and Hac. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 90, 145–152 (2006).

Gong, X., Li, J., Xu, K., Wang, J. & Yang, H. A controllable molecular sieve for Na+ and K+ ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1873–1877 (2010).

Lu, C. et al. In situ characterization of dehydration during ion transport in polymeric nanochannels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14242–14252 (2021).

Cao, L. et al. Solvation structure design for aqueous Zn metal batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21404–21409 (2020).

Bostick, D. L. & Brooks, C. L. III Selectivity in K+ channels is due to topological control of the permeant ion’s coordinated state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 9260–9265 (2007).

Ohtaki, H. & Radnai, T. Structure and dynamics of hydrated ions. Chem. Rev. 93, 1157–1204 (1993).

Lide, D. R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Vol. 85 (CRC press, 2004).

Martın, A. et al. Zeta potential of membranes as a function of pH: Optimization of isoelectric point evaluation. J. Membr. Sci. 213, 225–230 (2003).

Naghdi, S. et al. Selective ligand removal to improve accessibility of active sites in hierarchical MOFs for heterogeneous photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 282 (2022).

Cheng, Z. et al. Achieving long cycle life for all-solid-state rechargeable Li-I2 battery by a confined dissolution strategy. Nat. Commun. 13, 125 (2022).

Shi, R. et al. Nitrogen-rich covalent organic frameworks with multiple carbonyls for high-performance sodium batteries. Nat. Commun. 11, 178 (2020).

Sun, Y., Song, S., Xiao, D., Gan, L. & Wang, Y. Easily constructed imine-bonded COFs for iodine capture at ambient temperature. ACS Omega 5, 24262–24271 (2020).

Browne, C., Raghuwanshi, V. S., Garnier, G. & Batchelor, W. Modulating the chiral nematic structure of cellulose nanocrystal suspensions with electrolytes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 650, 1064–1072 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Evaluation of the microstructure of dry and hydrated perfluorosulfonic acid ionomers: microscopy and simulations. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 938–944 (2013).

Hu, J., Zhang, H., Xu, W., Yuan, Z. & Li, X. Mechanism and transfer behavior of ions in Nafion membranes under alkaline media. J. Membr. Sci. 566, 8–14 (2018).

Liang, G. et al. Regulating inorganic and organic components to build amorphous‐ZnFx enriched solid‐electrolyte interphase for highly reversible Zn metal chemistry. Adv. Mater. 35, 2210051 (2023).

Hao, J. et al. An in-depth study of Zn metal surface chemistry for advanced aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 32, e2003021 (2020).

Zakeri, B. & Syri, S. Electrical energy storage systems: a comparative life cycle cost analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 42, 569–596 (2015).

Darling, R. M., Gallagher, K. G., Kowalski, J. A., Ha, S. & Brushett, F. R. Pathways to low-cost electrochemical energy storage: a comparison of aqueous and nonaqueous flow batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3459–3477 (2014).

Kwabi, D. G. et al. Alkaline quinone flow battery with long lifetime at pH 12. Joule 2, 1894–1906 (2018).

Li, P. et al. Highly thermally/electrochemically stable I−/I3− bonded organic salts with high I content for long‐life Li–I2 batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2103648 (2022).

Okada, T., Møller-Holst, S., Gorseth, O. & Kjelstrup, S. Transport and equilibrium properties of Nafion® membranes with H+ and Na+ ions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 442, 137–145 (1998).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Yin, Y. et al. Dendrite‐free zinc deposition induced by tin‐modified multifunctional 3D host for stable zinc‐based flow battery. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906803 (2020).

Yuan, Z., Duan, Y., Liu, T., Zhang, H. & Li, X. Toward a low-cost alkaline zinc-iron flow battery with a polybenzimidazole custom membrane for stationary energy storage. Iscience 3, 40–49 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. CityU C1002-21G) and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation under Project 2022B1515120019. This work was also supported in part by the InnoHK Project on [Project 1.3 - Flexible and Stretchable Technologies (FAST) for monitoring of CVD risk factors: Sensing and Applications] at the Hong Kong Centre for Cerebro-cardiovascular Health Engineering (COCHE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.Z. conceived the project. G.J.L. and Z.Q.W. supervised the research. Z.Q.W. prepared the materials. Z.Q.W., Y.Q.W., H.H., Z.C., A.C., Z.D.H., and S.X.W. conducted the characterization and analyzed the data. Z.Q.W., S.Y., and Y.H. performed DFT calculations. Z.Q.W., G.J.L., and C.Y.Z. wrote the paper, and all authors engaged in discussions related to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Rajaram Nagarale, Caixing Wang, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Z., Wang, Y., Hong, H. et al. Long-life aqueous zinc-iodine flow batteries enabled by selectively intercepting hydrated ions. Nat Commun 16, 9301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64344-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64344-8