Abstract

Polymethacrylate derivatives are widely used in various industrial applications. The incorporation of degradable thioester bonds in polymethacrylates to achieve degradability/recyclability upon disposal is a challenge. Unfortunately, the most efficient thionolactone to insert cleavable thioester linkages does not copolymerize with methacrylates. We show that a small amount of the thionolactone can be inserted into polymethacrylates by the use of methyl acrylate or N-phenyl maleimide as an auxiliary third comonomer. We confirmed the selective degradation of the copolymer via aminolysis. The intriguing incorporation of the thionolactone via the formation of triads is demonstrated using Monte Carlo simulations and such method is also used to optimize the synthesis conditions. Copolymers of 60,000 g.mol-1 is obtained that could be degraded with a 25-fold reduction of size, confirming the model-based insights and opening the pathway to degradability for polymethacrylates. This approach is also successfully extended to poly(butyl methacrylate), and water-soluble poly(oligo(ethyleneglycol) methacrylate) for biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Free radical polymerization (FRP) is a leading industrial route for synthesizing vinyl polymers such as low density polyethylene, polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), with applications ranging from commodity (e.g. household tools and packaging items) to advanced products (e.g. composites and drug delivery devices)1,2. Such vinyl polymers are however composed of C-C bonds that are not realistically degraded under disposal conditions3. For their recycling, we can thus not rely on an intrinsic recyclability but need to reach out to mechanical or chemical recycling technology, the former challenged by inferior macroscopic properties upon repetitive recycling and the latter facing a high energy cost4,5,6.

The story on intrinsic (bio)degradability is completely different upon dealing with polymers bearing heteroatoms in the backbones or main chains, such as polyesters, polythioesters, polyoxazolines, and poly(phosphoester)s, as made from polycondensation and ring-opening polymerization routes7,8,9. These synthesis routes are unfortunately more restrictive than radical (chain-growth) polymerization routes, and the range of polymers that can be prepared is smaller, preventing the synthesis of polymer materials combining degradability upon demand and key properties of traditional vinyl polymers (e.g. a high tensile and impact strength).

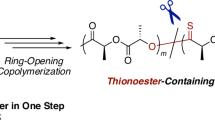

Interestingly, we can introduce heteroatoms into traditional polymer backbones by a radical route employing a low amount of well-defined cyclic (co)monomers that are prone to an addition-fragmentation mechanism, bridging the best of both worlds. This leads to a so-called radical ring-opening polymerization (rROP) route of which the principle is highlighted in Fig. 1a10,11. Such rROP can already be applied with various vinyl comonomers to obtain polymeric materials with highly adjustable degradable properties10,12. The insertion of weaker bonds into commodity (vinyl) polymers by rROP is a very promising way to shift towards sustainable polymer chemistry, as pioneered by Mecking and coworkers13,14 for high density polyethylene and recently reviewed by Guillaneuf et al.15 for a wide span of polymerization routes and applications. The main rROP advantage is to insert a very low amount of weak bonds to fragmentate the polymer for biodegradation/recycling purposes after its lifetime without (significantly) impacting the properties of the commodity polymer during its use.

a Description of the Addition – Fragmentation process. b rROP preparation of polyesters from cyclic ketene acetal (CKA) monomer (focus on homopolymerization and mentioning typical copolymerizations). c rROP of thionolactones, as explored in the present work, to introduce thioester linkages into the polymer backbone (focus on typical copolymerizations).

A structural complication encountered for rROP-made degradable copolymers is that the comonomer needs to be uniformly incorporated within the polymer backbones to confer substantial degradability into the parent (vinyl) polymer16. The degree of homogeneity of comonomer incorporation depends on the monomer reactivity ratios, being the ratios of homo- to cross propagation rate coefficients16, as well as on the polymerization time, temperature, initial monomer concentration17, and monomer addition profile(s)18, the latter supported by more recent modeling studies covering systems with less conventional monomer reactivity ratios. For example, D’hooge and Barner-Kowollik illustrated the strength of semi-batch addition for precision polymer synthesis for Passerini multicomponent polymerization19. Complementary, van Herk and coworkers20 used this approach to overcome the non-favorable reactivity ratios between cyclic ketene acetals (CKAs) and acrylate derivatives, to prepare polymers with high monomer conversion without a substantial compositional drift.

The main rROP monomer family, as evidenced by the vast library of monomer structures with diverse ring-sizes and substituent and detailed kinetic analysis, is that of CKAs, which yields polyesters under homopolymerization conditions (Fig. 1b, example with 2-methylene-1,3-dioxepane (MDO) as CKA)10,21,22. The use of CKAs has resulted in the development of several degradable materials; nonetheless, their absolute reactivity is very low compared to many industrially significant vinyl-based monomers, hence limiting industrial applications that need rapid and high-yield reactions10. Alternative compounds, like cyclic allyl sulfides23 and allyl sulfones24,25, have been synthesized; however, their lengthy and laborious synthetic methods hinder their practical application.

A relatively new rROP monomer family are thionolactones, which were discovered simultaneously by Roth26 and Gutekunst27 focusing on dibenzo[c,e]oxepine-5(7H)-thione (Fig. 1c, DOT). These authors26,28,29 showed that DOT is able to copolymerize with the vinyl monomer (classes) acrylonitrile, acrylates, acrylamides, maleimides derivatives, S-vinyl and P-vinyl monomers30, leading to (co)polymers with a thioester functionality within the polymer backbone. However, its copolymerization with styrene, methacrylate derivatives and vinyl acetate were not successful, at least initially. The compatibility of DOT with styrene and isoprene was only reported later on31,32,33, and Destarac et al.34 as well as Guillaneuf et al.35 reported ε-thionocaprolactone (thCL) as a second thionolactone monomer compatible with less activated monomers such as vinyl ester derivatives. Similarly, Gutekunst et al.36 reported the efficient copolymerization of cyclic thionocarbamate with N-vinyl pyrrolidone (NVP), N-vinyl carbazole (NVC), and N-vinyl caprolactam (NVCl).

With DOT and thCL as thionolactone comonomers, next to CKAs, the range of intrinsically recyclable vinyl-based polymers can be seen as quite large at first sight. However, it is non-trivial to achieve flexibility and precision control with methacrylates such as methyl methacrylate (MMA). For example, Roth et al.37proposed 3,3-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-5Hbenzo[e][1,4]dioxepine-5-thione (DBT) as a thionolactone compatible with reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization but the methyl methacrylate (MMA) was depleted first, leading to a much slower DBT insertion as expected based on the feed composition, inducing undesired intramolecular heterogeneity. Moreover, such thionolactone is incompatible with acrylate derivatives37.

Guillaneuf et al.38 recently showed that density functional theory (DFT) calculations could facilitate the in-silico design of new (co)monomer structures but likely significant research time and even unrealistic synthesis effort is needed to prepare them. Notably, during the writing of this manuscript, Johnson and coworkers39 also applied a DFT approach to design a DOT derivative F-p-CF3-PhDOT that was shown to copolymerize efficiently with MMA. Nevertheless, the preparation of this compound requires a less trivial 5 step-synthesis with an overall yield of only 13 %.

It should be stressed that the (meth)acrylate monomer family is industrially important, with for instance (i) many applications for the automotive industry, (ii) intensive usage for coatings40, casts and protective materials41, and (iii) various functionalized derivatives42. It is thus worthwhile to explore alternative synthesis protocols for degradable polymethacrylates such as PMMA, as done in the present work. Instead of trying to design/develop new structures to reach a good copolymerization behavior between methacrylate derivatives and thionolactones, we sought to tweak observed radical reactivity using an additive to subtly insert the DOT (that is now widely used and whose synthesis is now well mastered in different research groups) into the polymer chain. More in detail, we pioneer the copolymerization of DOT with both acrylate derivatives and maleimide, keeping in mind their copolymerization potential involving methacrylate derivatives. This is done to design efficient DOT-methacrylate-acrylate and DOT-methacrylate-maleimide terpolymerizations, allowing the regulated insertion of weak DOT-based thioester moieties in a fast manner into methacrylate-rich backbones, using a thionolactone comonomer and an auxiliary comonomer.

The choice of the DOT degradable monomer unit (simply “green” unit) is dictated by its availability and efficiency in various copolymerization systems with the only disadvantage its non-reactivity with radical methacrylate derivative units (simply “blue” units)26,27 so that its incorporation should be only directed by the auxiliary comonomer unit (simply “red” unit), either an acrylate or maleimide unit, as shown in Fig. 2b-c (aim of no “green” after “blue” but “green” after “red”). The potential of an auxiliary comonomer to modify the reactivity of methacrylate derivatives has been previously demonstrated by Charleux and Nicolas43,44 for nitroxide-mediated polymerization, and for efficient enhanced spin-capturing polymerization by Junkers and Barner-Kowollik45. Recently, Niu and coworkers46 as well as Sardon et al.47 proposed to introduced either maleimides or crotonate esters to increase the incorporation of CKA into methacrylate based polymers.

a Current issue with no copolymerization of dibenzo[c,e]oxepine-5(7H)-thione (DOT; “green”) with methacrylates (“blue”), instead delivering poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with the absence of degradable (DOT) units; b, c The aim of preparing of degradable PMMA derivatives by terpolymerization of the pair MMA and DOT, with either b methyl acrylate (MA) or c N-phenyl maleimide (PhMal) (“red”), as explored in the present work and with monomer sequences understood using coupled matrix-based Monte Carlo (CMMC) simulations.

The present work puts forward a highly novel combined chemistry and engineering approach to pinpoint and design less conventional batch terpolymerization, opening the door to the successful rROP of methacrylate derivatives avoiding semi-batch approaches. Using well-established rROP comonomers, we reveal new mechanistic insights such as (i) chain transfer to MMA after an at first sight unexpected DOT addition as well as (ii) triad formation with the auxiliary monomer (unconventional “red”-“green”-“red” sequence instead of the more conventional “red”-“green” sequence). These insights are possible thanks to so-called coupled matrix based Monte Carlo (CMMC) simulations, enabling the visualization of each monomer sequence per chain in a representative ensemble by stochastics means48,49. The individual segment lengths after hydrolytic degradation are therefore directly known, enabling a unique quality labeling of the rROP synthesis approach for the selected reaction conditions.

Results

We first focus on methyl methacrylate (MMA) as a model methacrylate derivative to obtain degradable PMMA. We experimentally explore conventional batch co- and terpolymerization conditions, highlighting that CMMC model-design is needed to realize well-defined PMMA-rich backbones with regulated degradability in a fast manner. The most critical model parameters are evaluated and optimized to reveal new mechanistic insights and the best synthesis conditions, as confirmed by experimental validation of the simulation chemical design rules. We then use the same synthesis conditions to highlight also their relevance for other methacrylates, aiming at (i) a lower glass transition temperature (Tg) polymer and (ii) a polymer for the biomedical field.

Experimental conventional co- and terpolymerization

In a first step, we investigated the copolymerization of DOT and MMA, a reference methacrylate derivative. The polymerization is performed at 80 °C, initiated with 0.5 mol% of azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), in solution (anisole; 50 v%) to minimize the gel-effect50,51. The introduction of 5 mol% of DOT in the batch recipe does not lead to any change in the overall conversion compared to the DOT-free MMA polymerization, and produces a poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with roughly similar average molar masses (Supplementary Fig. 12).

A double detection SEC, using Differential Refractive Index (DRI) and UV(254 nm) detectors, was performed to determine if any DOT moieties were inserted into the backbone for a MMA/DOT copolymerization (Fig. 3a). The UV trace showed only a weak aromatic signal for the polymer backbone, confirming the at most very limited incorporation of DOT units. The polymers could also not be degraded under hydrolytically driven conditions (Fig. 4a), so that the sole use of DOT is not.

a, b SEC analyses using double detection (DRI blue line; UV 254 nm: aromatics) green line) for batch synthesis with a) MMA and DOT (weak DOT presence so “blue” chains; 5 mol% initial); and b MMA, MA and DOT (significant DOT presence; [MMA]0:[MA]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5). c SEC analyses using multiple detection (DRI blue line; UV (254 nm): red line: UV of PhMal and DOT; orange line; UV 330 nm: only thioester) for terpolymerization [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5. d Comparison of the normalized UV(254 nm) for MMA (blue line), MMA/DOT (short dotted green line), and MMA/MA/DOT (solid green line), as well as the UV(330 nm) (orange dashed line) for MMA, PhMal, and DOT batch terpolymerization. The solid and dashed lines cannot be compared on an absolute basis, as the absorption coefficients for the DOT-base thioester unit at 254 and 330 nm are different.

SEC analyses (DRI signal) before (dark blue full lines) and after degradation (light blue dotted lines) for a MMA and DOT copolymerization (5 mol% initially); b MMA, MA and DOT terpolymerziation ([MMA]0:[MA]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5); c MMA, PhMal and DOT terpolymerziation ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5). For a and b degradation using KOH (5 wt%) in methanol for 17 h. For c degradation using NH3 in methanol for 17 h. Solid dark blue (start) and dotted light blue (end).

As Roth26 and Gutekunst27 showed that the copolymerization between acrylate derivatives and DOT is very efficient, in a second step, we performed a MA-driven terpolymerization at 80 °C in 50 mol% of anisole, using a feed molar ratio [MMA]0:[MA]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5. After 3 hours, we obtained 83.3% of conversion for MMA as compared to 72.2% for MA and 13.7 % for DOT. Analysis of the isolated polymer by dual detection DRI/UV(254 nm) SEC confirms the labeling of chains by DOT (Fig. 3b). The degradation of the polymer was also performed, using highly efficient basic conditions (5% potassium hydroxide (KOH) in methanol (MeOH); Fig. 4b). After degradation, the aromatic signal disappeared for the SEC signal, confirming the hydrolysis of the thioester bond. Nevertheless, the shift of the molar mass distribution (MMD) is only limited with a moderate number average molar mass (Mn) decrease from 46,800 to 39,000 g.mol-1, indicative of a low (or less efficient) incorporation of thioester moieties into the polymer backbone. Hence, the explored conventional conditions seem limiting, highlighting the relevance of model-based design with auxiliary MA is recommendable.

Before doing so, maleimide driven systems have been considered in an alternative third step, as Roth and coworkers29 have shown that the copolymerization of maleimide derivatives and DOT produces very efficiently an alternating copolymer. The combination of maleimide derivatives, MMA and DOT seems thus interesting to incorporate DOT into a PMMA chain, as the copolymerization of maleimide and methacrylate derivatives has been reported as well52,53,54,55. We specifically have chosen in this third step phenyl maleimide (PhMal) as a comonomer, knowing that the phenyl moiety can be monitored via double detection SEC (UV at 254 nm). Extra UV detection at 330 nm can discriminate the insertion of the thioester moiety from DOT to the aromatic detection for both PhMAl and DOT at 254 nm, although strictly the direct (absolute) comparison of the signal at 254 and 330 nm cannot be done since the absorption coefficient ε is different.

A testing copolymerization using MMA and 10 mol% of PhMal was initially performed and confirmed the random introduction of PhMal into the polymer chains (Supplementary Fig. 3). We then conducted the terpolymerization at 80 °C in 50 mol% of anisole, using a feed ratio [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5. As for MMA/DOT copolymerization and MMA/DOT/MA terpolymerization, we followed the synthesis (Fig. 3c) and the degradation (Fig. 4c) by (multi-detection) SEC. The strong basic degradation conditions used for the previous polymerizations can, however, not be used here, as they lead to the ring-opening of the maleimide unit (Supplementary Fig. 4). It is thus impossible to discriminate between PhMal modification (ring-opening of the maleimide structure) and DOT-induced degradation under the strong basic conditions. Instead, milder conditions realized by ammonia (NH3) addition in methanol, knowing to degrade thioester linkages28 but not modifying the maleimide group (Supplementary Fig. 4), have been applied. Notably, Fig. 4c shows a relatively strong MMD shift with a decrease of Mn from 36,300 g∙mol-1 to 12,400 g∙mol-1.

The relative decrease of Mn is thus more important for a terpolymerization using PhMal than MA (Fig. 4c vs Fig. 4b), showing that the propagation rate coefficients seem more appropriate in the case of maleimide derivatives. Nevertheless, the Mn of the degraded product is not in agreement with the amount of DOT added; assuming equal monomer distances one would expect a much lower Mn of 2000–2500 g∙mol-1. Hence, also for the maleimide-based system model-based design is recommendable to tune the polymerization conditions.

Parameter tuning in view of model-based design

Model-based design is only strong if sufficiently reliable modeling parameters are available. In the context of monomer sequence control, specifically, the propagation rate coefficients and the associated (monomer) reactivity ratios (r values) are relevant. For DOT-based propagations, limited (less reliable) r values are only available, and they are by default based on terminal copolymerization models. For the comonomer pair DOT/MA, Roth et al.26 e.g. determined rDOT = 0.003 and rMA = 0.424, highlighting a preference of cross-propagation specifically in case DOT is a terminal unit of an active chain. In contrast, Gutekunst et al.27 reported that DOT incorporation is more important than the acrylate derivative for DOT ending radicals, suggesting a rDOT higher than 1.

As the rDOT value is of paramount importance for our model-based design, we first re-investigated the copolymerization of DOT and MA and determined reactivity ratios, using the Skeist equation and Nonlinear Least-Squares (NLSS) fitting (see Supplementary Information)56,57,58. Molar feed ratios [MA]0:[DOT]0 of 95:5, 80:20, and 50:50 have been used, and the conversion of both comonomers was determined by 1H NMR. The polymerization is slower with an increasing initial amount of DOT, with only 30% of monomer conversion for the initial feed ratio of 50:50, and even the absence of polymerization for higher contents of DOT. Nevertheless, it was possible to determine the reactivity ratios as rDOT = 1.6 and rMA = 0.2 (Fig. 5), that overall are consistent with literature data.

Experimental and simulated DOT feed monomer composition versus overall molar conversion (Skeist equation56) with fitted rMA = 0.2 and fitted rDOT = 1.6 during copolymerization of DOT and MA at 80 °C in anisole (50%); average error of 5%.

In addition, for the alternative system DOT – PhMal, Roth and coworkers29 showed by NMR that a purely alternating copolymer is obtained. Hence, we considered the reactivity ratios to be rPhMal ≈ 0 and rDOT ≈ 0.

A further inspection of the literature-based r values highlights that for the comonomer pair acrylate-methacrylate most emphasis has been on MMA/n-butyl acrylate (BA) and less on MMA/MA59,60,61,62. More in detail, rMMA values between 1.93 and 2.15, and rBA values between 0.31–0.4 have been determined, varying the nature of the solvent and the temperature, and consistent with a tertiary radical being more stable than a secondary one, and e.g. the results of Penlidis et al.63 focusing on terpolymerization between tri-isopropylsilyl acrylate, MA, and BA. Notably pulsed laser polymerization investigations of various acrylate derivatives revealed a similar activation energy with only a slight increase of kp with the size of the alkyl chain, as also reported for methacrylate derivatives64. We can thus approximate the reactivity ratios of MA and MMA by those of MMA and BA, with selected values of rMMA = 2.0 and rMA = 0.35.

For the MMA – PhMal pair, there are only a few publications dealing with the determination of their reactivity ratios. In particular Hasan and coworkers55 determined rMMA = 0.23 and rPhMal = 0.1. Another study by Schmidt-Naake et al.52 investigated the influence of solvent, reporting average values of rMMA = 1.35 and rPhMal = 0.165. These average values seem at first sight more representative, as with the derivatives N-4-chlorophenyl maleimide54 and N-4-tolyl maleimide53 rMMA values close to 1 and rPhMal values between 0.1 and 0.3 have been reported. As these r values are of crucial importance for the simulation, we also determined them under the same (overall) experimental conditions as the terpolymerization system (see Supplementary Information). Reactivity ratios rMMA = 1.94 and rPhMal = 0.9 have been determined (Supplementary Fig. 7), highlighting the relevance of this extra experimental work, seeing some deviation with the overall literature range.

Note that the homopropagation rate coefficients for DOT and PhMal are not reported in the literature. They have been therefore determined in the present work via CMMC simulation of polymerization kinetic data reported in literature29,65. This has been done with a simplified reaction scheme, which includes chain initiation, propagation, and termination reactions (see Supplementary Information for details).

Model validation for co- and terpolymerization

For the modeling, we started from the benchmarked CMMC model of De Smit et al.17. This kinetic model is the leading model for radical homo- and copolymerization with MMA as main monomer, accounting for diffusional limitations, specifically the gel-effect. In the present work, we have enhanced this model with (cross-)propagation reactions involving DOT and MA/PhMal as well as chain transfer reactions, particularly chain transfer to MMA with a DOT terminal active chain.

The complete list of the elementary reactions and kinetic parameters for the modeling of the co- and terpolymerizations is provided in the Supplementary Information. The method of mathematical optimization was employed to determine remaining unknown kinetic parameters in the polymerization process. This approach involved varying these parameters during CMMC simulations, using a fixed pseudorandom number generator to ensure consistent results. Fixing the generator was crucial for the stable operation of the optimization algorithms, as it minimized variability in simulation outcomes, allowing for more reliable convergence towards optimal parameters. The optimization process was guided by a loss function designed to quantify the deviation between simulation and experiment:

in which \({x}_{\exp,i}\) is the (final) experimental conversion (for the ith point), \({x}_{{sim},i}\) is the (final) simulated conversion, \({M}_{\exp }^{{syn}}\) is the experimental maximum of the polymer SEC trace before degradation, \({M}_{{sim}}^{{deg}}\) is the experimental maximum of the polymer SEC trace after degradation, \({M}_{{sim}}^{{syn}}\) is the simulated maximum of the polymer log-MMD trace before degradation, and \({M}_{{sim}}^{{deg}}\) is the simulated maximum of the polymer log-MMD trace after degradation.

The optimization was carried out in two stages for greater precision, keeping in mind that the shift in (peak) molar mass should be a reasonable target and the absolute Mn values are likely only in qualitative agreement, bearing in mind that a model will fully reflect the low molar mass end with no washing out of smaller species as in an experiment. In the first stage, the DIRECT-L algorithm was applied to find the global minimum of the loss function6. This initial search was performed within a microscopic system volume of 3·10−16, which represented a balance between computational speed and the accuracy of the simulation. At this scale, the algorithm efficiently explored the broader parameter space, locating promising regions in which the loss function was minimized. In a second stage, a local optimization was performed using the COBYLA (Constrained Optimization BY Linear Approximations) algorithm7. This phase was conducted at a larger microscopic system volume of 5·10−16, allowing for finer adjustments and more accurate determination of the kinetic parameters. The combination of the DIRECT-L global search with the local refinement capabilities of COBYLA enabled a sufficiently accurate determination of the kinetic parameters, providing results within 16 to 20 hours. This two-step optimization approach not only improved the accuracy of the kinetic parameter estimation but also maintained computational efficiency, making it suitable for complex polymerization modeling. The reader is referred to the Supplementary Information for more details on the parameter tuning procedures, which are all literature based.

For plotting of monomer sequences, we only depict maximally 200 chains out of the ensemble with millions of monomer units, with the monomer units colored as defined in Fig. 2 i.e. blue for an MMA unit, green for a DOT unit, and red for an auxiliary monomer unit being either based on MA or PhMal.

For (batch) MMA/DOT copolymerization, we observe in Fig. 6a a qualitative agreement of the experimental (red line; repeated from Fig. 3a and simulated (blue dotted line) MMD, with respective Mn values of 40,000 g∙mol-1 and 30,000 g∙mol-1, a difference that can be expected seeing the focus on the peak of the MMD and the experimental less reliable result for the lower molar masses, as explained above. Furthermore, the in-silico analysis of individual polymer chains in Fig. 6b and Fig. 6c reveals that a few chains possess DOT as a terminal unit, as otherwise the weak experimental UV signal in Fig. 3a cannot be explained.

a comparison of the experimental SEC trace (red line), the simulated log-MMD accounting for chain transfer to monomer (blue dotted line), and the simulated log-MMD without chain transfer to monomer reaction (green line) SEC traces; b monomer sequences of 200 chains; c monomer sequence of 9 selected chains; blue – MMA unit, green – DOT unit, purple – terminal double bond (a product of disproportionation), orange – terminal saturated unit (a product of disproportionation or chain transfer to monomer). In subplot a, also a simulated concentration dependency for DOT (orange line), consistent with the weak UV signal in Fig. 3a.

More in detail, we postulate based on the results in Fig. 6 that one of the occurring chain-stopping mechanisms in MMA/DOT synthesis recipes is the radical addition on DOT followed by chain transfer to MMA, a novel mechanistic insight in the field. If this chain transfer reaction is fully excluded for the MMD calculation in Fig. 6a (green line) no change is observed, however, a weak simulated UV-like signal can be obtained if the reaction is accounted for. This simulated signal is shown as the bottom line in Fig. 6a, and follows from counting in the complete matrix representation all terminal DOT units for all chain lengths.

As shown in Fig. 7a and d, for batch MMA/DOT/MA and MMA/DOT/PhMal terpolymerziation, we observe a good quantitative agreement of the shift for experimental and simulated SEC traces before and after degradation, with the most pronounced degradation MMD shift for MMA/DOT/PhMal terpolymerization. A closer inspection reveals that the model description on an absolute basis is better with PhMal than with MA, highlighting a better quantification of r values for the MMA/DOT/PhMal terpolymerzation and a likely a more reliable model-based design for the latter system.

a Simulated and experimental log-MMD/SEC results (4 hours synthesis and after hydrolysis) for the terpolymerization of MMA/DOT/MA ([MMA]0:[MA]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5), with Mn 19,300 g∙mol-1 (simulation) and 46,800 g∙mol-1 (experiment) for polymer before degradation, 13,600 g∙mol-1 (simulation) and 39,000 g∙mol-1 (experiment) for polymer after degradation, b monomer sequences of 200 chains and c selection of 10 polymer chains from b, displaying stand-alone MMA-MA units (examples in red boxes) and triads MA-DOT-MA (example in green box). Blue – MMA unit, green – DOT unit, purple – terminal double bond, orange – terminal saturated unit; d–f Similar results for MMA/DOT/PhMal ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:5:5) with PhMal in red; Mn of 18,190 g∙mol-1 (simulation) and 36,300 g∙mol-1 (experiment) before degradation, 7300 g∙mol-1 (simulation) and 12,400 g∙mol-1 (experiment) after degradation.

The additional in-silico analysis of individual polymer chains in Fig. 7b, c, e, f reveals (i) the presence of undegradable “stand-alone” MA or PhMal units, in general auxiliary comonomer units, only encapsulated by MMA units, and (ii) the presence of “symmetric” degradable triads based on DOT, i.e. ~MA-DOT-MA~ or ~PhMal-DOT-PhMal ~ . Cross-propagation rates for DOT/MA and DOT/PhMal are higher than homopropagation rates, making the formation of such triads plausible, with more such triads in the sample for PhMal consistent with the more pronounced MMD shift. Consistently, the DOT-MMA cross-propagation rate is very low so that the probability of stand-alone DOT monomer units is low, reminding the simulation of MMA/DOT copolymerization from Fig. 6.

Kinetic analysis further highlights that the fractional conversion of DOT monomer is limited and always around 20% (Fig. 8a; PhMal-based terpolymerization). Some deviations between model and experiment are, however, witnessed for the actual time dependency of MMA and PhMal conversions, but this can be attributed to NMR signal overlapping, and the inherent correct concentration balance of simulations with no calibration issues. This DOT limitation contributes to the formation of longer PMMA segments in certain chains (e.g. 100 units), away from a targeted length of 20 units (molar mass of 2000 g∙mol-1) as needed from a degradability point of view66,67,68. Unfortunately, the average simulated segmental chain lengths of the PMMA fragments in Fig. 7 are too high (~60 monomer units), to enable classification as (disposable) oligomers, which is due to the unfavorable propagation kinetics leading to compositional drift17.

Hence, the present model-supported work demonstrates that our common understanding of the copolymer structure with DOT/MA or DOT/PhMal (“red-green”) is too simplified, and instead MA or PhMal centered triads are formed (“red-green-red”). This also means that the segmental chain length of PMMA between two DOT centered triads determines the chain length of the polymers after degradation. Moreover, both experimental and simulated data favor design with the MMA/DOT/PhMal terpolymerization.

Model-based design and validation

In a first step, we can optimize the initial comonomer amounts, knowing that De Smit et al.17 showed that for the copolymerization of MMA and CKA this can significantly improve the segment length distribution, allowing for the synthesis of degradable PMMA-based polymers.

To explore this possibility with a DOT-based terpolymerization system, we varied the initial fractions of DOT and PhMal in the most promising MMA:DOT:PhMal terpolymerization system, reminding that the degradation with MA as auxillary monomers was less efficient (Fig. 4), and keeping the other experimental parameters fixed. The molar ratios [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 equal to 90:5:10 (as a percentage 85.75%/4.75%/9.5%) and 90:10:5 (as a percentage 85.75%/9.5%/4.75%) have been selected. Reminding the previous use of 90:5:5 in Fig. 7e, these two recipes relate to the increase of the initial loaded mass of PhMal or DOT by a factor 2.

The experimental and simulated SEC and MMD results of the three polymers ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 equal to 90:5:10, 90:10:5 and 90:5:5, before and after degradation, are shown in Fig. 9. They are in qualitative agreement, further highlighting the relevance of the use of the model for screening a wide range of reaction conditions. It is further seen that particularly the increase of the initial load of PhMal ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 90:10:5 i.e. 85.75%/9.5%/4.75%) results in a polymer with a higher Mn = 41,660 g∙mol-1, and after degradation, in oligomers with a smaller Mn = 10,550 g∙mol-1 (Fig. 9b). Hence, it is worthwhile to further tune the comonomer amounts by model-based design.

Effect of initial molar ratios ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0), considering 90:10:5 (green); 90:5:10 (yellow); 90:5:5 (purple)), on experimental a and simulated b SEC traces/log-MMDs after 3 hours of MMA:PhMal:DOT terpolymerization (full lines) as well as after degradation (dashed lines).The heights of all peaks are normalized to 1 to emphasize the shift to the left. Purple lines are repeated from Fig. 7e. The simulated traces also simulation the oligomer contributions.

Similar final molar fractions are also simulated and experimentally observed for MMA, DOT and PhMal in this more favored MMA:PhMal:DOT terpolymerization, as shown in Fig. 8b ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:10:5). There is still some deviations between model and experiment that are explained by difficulties of NMR (overlapping of signals) and the inherent correct concentration balance of simulations as opposed to experiments; a combined experimental and model analysis is more reliable, consistent with for instance the work of Van Steenberge et al. on copolymer design for drug delivery2.

Supported by the acceptable shifts before and after degradation for the most promising MMA/PhMal/DOT polymerization (Fig. 9), we performed in a second step model-based design of several concentrations for the synthesis recipe, reminding also the more reliable r values. This design is done to achieve a lower average segment length by controlling the triad incorporation from one chain end to the other. We focused on the in silico variation of the initial PhMal, DOT, and solvent loads under batch conditions, fixing the conventional initiator amount, bearing in mind that this can change the average molar mass of the synthesized polymer. The search for the optimal initial feed ratios was performed via a global maximum search of the (simulated) Mn difference of the polymer before and after degradation.

To find the optimal compositions for synthesis, a minimization algorithm was applied. The simulation of terpolymerization was performed by varying the content of the components MMA, DOT, PhMal, and solvent. The reactivity ratios obtained in the previous step were used for this design. The number-average molar mass of the polymer after degradation was used as a loss function, with the inherent aim to maximize the fraction of oligomeric chains as theoretically these matter the most:

During the optimization, all compositions with \({M}_{n}^{{deg}} < 10000g\bullet {{mol}}^{-1}\) were stored. After 24 hours of searching, the optimization was stopped. As a result of the search, ~200 compositions were saved. From the stored compositions, those with minimal \({M}_{n}^{{deg}}\) and high \({M}_{n}^{{norm}}\) were manually selected.

The two most important results of this in silico design are highlighted in Fig. 10 (red lines), displaying MMD variations for [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:25:16 (68.8%/19%/12.2%) (50% solvent; subplot a) and [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28 (66.2%/13.2%/20.6%) (30% solvent; subplot b). In both cases, the PhMal amount is enhanced, but the cases differ in the role of solvent and DOT being less or more pronounced (compared to PhMal). In both cases, the model predicts a Mn after terpolymerization of ca. 40,000 g∙mol-1 similar to what has been obtained before. For subplot a, the simulated Mn decreases after degradation to 2200 g∙mol-1 and for subplot b a theoretical decrease to 1600 g∙mol-1 is obtained. Such low degradation Mn values are within the target design range, which was unreachable before applying the model-based design, showcasing the novelty of the present work. Consistently, the simulations highlight the stronger presence of PhMal-DOT-PhMal triads ensuring short PMMA segments after degradation, as illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12.

The best modeling results for synthesis and degradation (red lines) at the SEC/MMD level are obtained for a [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:25:16 (68.8%/19%/12.2%) (50% solvent) and b [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28 (66.2%/13.2%/20.6%) (30% solvent). This is further confirmed by the experimental lines in the same subplots (blue lines; also included in Fig. 11 as grey lines).

The simulation design has also been validated experimentally by the blue lines in Fig. 10, with the experimental SEC traces repeated in Fig. 11 also including deconvolution for the degraded oligomers (grey lines). Using the conditions [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:25:16; (68.8%/19%/12.2%) and 50% solvent (case a), a polymer with Mn = 37,300 g∙mol-1 is obtained, delivering degraded oligomers with Mn = 3000 g∙mol-1 upon using deconvoluted SEC; the raw SEC data are purely experimentally not easy to analyze due to the presence of non-negligible amount of low mass side products. The use of the conditions [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28, (68.8%/19%/12.2%) and 30% solvent (case b) allowed to increase the original Mn to 59,500 g∙mol-1, with afterwards an even lower Mn of the degraded oligomers (Mn = 2,500 g∙mol-1). This corresponds to a massive 25-fold decrease in the Mn of the pristine PMMA copolymer.

A good agreement is thus obtained between modeling and experimental results (specifically, if one also sees the clear presence of lower mass species in the original SEC traces), highlighting the strength of the model-based approach presented in the present work. A closer inspection, however, reveals that the experimental Mn values are higher, which can be attributed to the less trivial SEC analysis of oligomers and SEC broadening. Overall, the present work identifies less conventional synthesis conditions, giving the targeted molecular structure for the polymer made, and thus the desired degradation performance.

Moreover, the experimental composition of the copolymer (case b) has been determined using the final conversion of the three monomers. We obtained values of 94%, 94% and 30% respectively, implying that the copolymer contained 77% of MMA, 15.5% of PhMal, and 7.5% of DOT; the NMR-based experimental determination of the copolymer composition is impossible, due to a large overlapping of the 1H NMR signals. Supposing a random incorporation of DOT, this should lead to oligomers with a degree of polymerization close to 15 and thus Mn close to 1600 g∙mol-1. The experimental value (Mn = 2500 g∙mol-1) is thus in rather good agreement with this theoretical value, further highlighting the relevance of the model-based design.

Application with butyl methacrylate using the same model-based design conditions and material properties

Besides methyl methacrylate, we extended the terpolymerization recipe developed above to other methacrylate derivatives to ensure that this process is independent of the pendant alkyl group. We first prepared a copolymer based on n-butyl methacrylate that has a Tg close to room temperature (Tg close to 30 °C) and that is drastically different from PMMA (Tg close to 120 °C).

Using the same synthesis recipe as above, the copolymerization was achieved successfully and led to a copolymer with Mn = 70,600 g∙mol-1 (Fig. 12a). The same degradation procedure led to oligomers with Mn after deconvolution close to 5100 g∙mol-1, leading to a degree of polymerization that is similar to the one obtained after the degradation of PMMA copolymers; the degree of polymerization is now close to 500 for the starting material and close to 30–35 for the degraded polymer chains. We can therefore state that the simulations and, therefore, the chosen recipe are independent of the alkyl group.

a SEC analyses (DRI signal) before (solid blue) and after degradation (dashed light blue) for the model-designed conditions from MMA but taking BMA: [BMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28 (68.8%/19%/12.2%), 30% solvent (Supplementary Table 2 entry 5). The degradation was performed using NH3 in methanol for 17 h. The dotted grey curve is the deconvoluted signal of the degraded oligomers. b Isolated reference P(MMA-co-PhMal-co-DOT) and reference PMMA, and the corresponding films made by solvent casting.

The material properties have also been investigated. First, the degradable PMMA and PBMA copolymers are both white powders that are similar to the corresponding homopolymers. A solvent-cast film of PMMA copolymer and a reference PMMA with a similar Mn led to similar transparent materials (Fig. 12b).

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the copolymer samples did not reveal any mass loss before 280 °C, which is similar to a traditional PMMA sample (Supplementary Fig. 6). In addition, DSC analysis of the copolymer prepared using [MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28 (68.8%/19%/12.2%) and 30% solvent showed a single glass transition temperature Tg of 149 °C (Supplementary Fig. 5) that is higher than the one of pristine PMMA of similar Mn (Tg = 116 °C). Consistent with the modeling results on the monomer sequences, the presence of only one Tg implies that all the monomer units are sufficiently randomly inserted into the copolymer chains, or at least that phase separation does not occur between DOT-rich and DOT-poor domains. The increase in Tg is in agreement with literature data, with e.g. Roth and coworkers29 showing that the alternating PhMal-DOT copolymer has a Tg = 156 °C. The Tg of homo poly(N-phenylmaleimide) was also estimated as 325 °C69.

Dynamical mechanical analysis (Fig. 13c) on samples compression molded at 170 °C confirms the presence of a single Tα transition with a narrow peak for the loss factor. The rubbery plateau located between the glass transition and the terminal regime at high temperatures is, however, significantly shorter for the poly(MMA-co-PhMal) copolymer (Supplementary Table 2 entry 2) than for pure PMMA (Supplementary Table 2 entry 3), and even shorter for the poly(MMA-co-PhMal-co-DOT) copolymer (Supplementary Table 2 entry 1). Given the relatively close average molar masses and dispersities of these polymers, this suggests that the entanglement molar mass Me is significantly increased upon copolymerization with these rigid comonomers. While extensive mechanical characterization of these copolymers is beyond the scope of the present work, this also suggests that reaching toughness similar to pure PMMA in the degradable copolymers might require additional effort to reach higher average molar masses. Similar results were found for PBMA copolymers, including PhMal and PhMal/DOT units (Fig. 13d), including an increase of Tα and a reduced entanglement plateau.

a Yellowing of the samples after compression-molding and evolution of the SEC trace after one and two heating cycles for the Poly(MMA-co-PhMal-co-DOT) ([MMA]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28 (66.2%/13.2%/20.6%) and 30% solvent. (Supplementary Table 2 entry 1) b Yellowing of the samples after compression-molding and evolution of the SEC trace after one and two heating cycles for the Poly(PhMal-alt-DOT) ([PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 50:50 and 68% solvent (Supplementary Table 2 entry 4). c, d Moduli and loss factors of DMA analyses (1 Hz, 1000 Pa shear stress, 3 °C min-1) of PMMA copolymers (Supplementary Table 2 entry 1,2,3) and PBMA copolymers (Supplementary Table 2 entry 5,6,7).

Rheological time-monitoring of the poly(MMA-co-PhMal-co-DOT) sample was carried out as well at 170 °C, and then 200 °C (Supplementary Fig. 13a). While the sample appears thermally stable at 170 °C, a continuous decay of the moduli is observed at 200 °C. After 1 h at 200 °C, a DMA characterization was carried out again, demonstrating a 10 °C decrease of the Tα transition, and significantly decreasing moduli with the complete absence of any rubbery plateau (Supplementary Fig. 13b). These results are highly consistent with cleavage of PhMal-DOT sequences and transformation into unentangled oligomers, which opens the way to a new thermally trigger to induce polymer degradation.

During the compression molding at elevated temperature (> 200 °C), we additionally noticed a yellowing of the terpolymer materials, that was not occur with pure PMMA or PMMA-PhMal copolymer. SEC analyses of the polymers before and after multiple heating steps were therefore performed. The analyses showed that after each compression molding at 200 °C, the SEC trace presented a degradation with a 2-fold decrease in Mn (Fig. 14), yet no mass loss was evidenced by TGA. Intrigued by this result, we first checked that both pure PMMA, MMA-PhMal copolymer and even some poly(styrene-co-DOT)32 and poly(isobornyl acrylate-co-DOT) were not affected by such heating treatments. The thermal instability could thus be specifically due to the triad PhMal-DOT-PhMal or, in general, the presence of DOT-PhMal sequences. Indeed, upon preparing the alternating copolymer PhMal-DOT reported by Roth and coworkers29 and processing this alternating copolymer at the same temperature `as the Poly(MMA-co-PhMal-co-DOT) copolymer, we also observed yellowing of the materials. As shown in Fig. 13b, we then also observed a shift of the SEC trace, again confirming the degradation potential of PhMal-DOT.

SEC analyses (DRI signal) before (blue line) and after degradation (red and purple lines) for the model-designed conditions applied to OEGMA500: [OEGMA500]0:[PhMal]0:[DOT]0 = 90:18:28 (68.8%/19%/12.2%) and 30% solvent. The degradation was performed either using NH3 in methanol/THF for 17 h (red line) or in PBS with 10 mmol of cysteine at pH 7.4 for 1 day (purple line).

Application for biomedical methacrylates using the same model-based design conditions

Besides pure alkyl methacrylates, some methacrylate derivatives are hydrophilic/hydrosoluble and, hence, could be used for biomedical applications. In particular, the oligo(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (OEGMA) monomer has been widely reported for preparing poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) like conjugates at a protein’s N-terminus, with significantly improved pharmacokinetics or/and tumor accumulation70. Recently, Hawker et al.71 reported the preparation of lipid-Poly(OEGMA) derivatives having a monodisperse structure containing a discrete number MAPEG with an unique number of ethylene glycol units (3 or 4) and a specific chain end that allow a better nanoparticle assembly combined with a lower anti-PEG antibody recognition. Nicolas et al.72 also reported the preparation of degradable prodrug containing nanoparticles based on Poly(OEGMA) as hydrophilic moiety.

In order to impart degradability to these polymers, we thus extended our system to OEGMA 500, which is a methacrylate with a PEG side chain of 10 oxyethylene units. The copolymerization of OEGMA, PhMal and DOT was then carried out using the previously established recipe. This led to a poly(OEGMA500) copolymer with a Mn close to 90,000 g∙ mol-1, as determined by SEC DMF using PMMA as standard (Fig. 14). The exact Mn is supposed to be higher, as an apparent Mn has been determined using standards that not have the same behavior in solution73.

In a preliminary test, we performed the same degradation procedure as the one we performed for the hydrophobic copolymers, i.e., aminolysis using ammonia in a THF/MeOH mixture. We obtained a rather good degradation with the production of oligo(OEMA500) with a Mn of 11,000 g∙mol-1, which is at least 9 times lower than the non-degraded copolymer, and corresponds to a degree of polymerization of 22 (Fig. 14; blue vs; red line). The discrepancy compared to the full target could arise from the use of an apparent molar mass that is known to impact the SEC accuracy in cases standards and samples do not have the same structure73.

We also investigated the degradation of the hydrosoluble poly(OEGMA) copolymer in water, as its use in biomaterial applications could be interesting. We thus used the conditions using cysteine already reported by Roth et al.28 for the degradation of polyacrylamides containing DOT units into the backbone. With these specific and mild conditions (cysteine, PBS, 37 °C; purple vs blue line in Fig. 14), we managed to obtain a significant degradation of the starting copolymer. Indeed, we obtained oligomers with a Mn close to 25,000 g∙mol-1. Such behavior with a lower efficiency of degradation from NH3-based aminolysis to cysteine degradation in water is consistent with the work or Roth and coworkers. Nevertheless, this extra experiment confirmed the degradation ability of poly(OEGMA500) in water.

Discussion

To make polymethacrylates such as PMMA inherently degradable upon disposal, cleavable monomer units need to be incorporated in a precise manner. Under industrially relevant conditions, this implies a radical polymerization route such as rROP. Nevertheless, the more promising DOT thionolactone monomer that allows the controlled embedding and degradation of polystyrene, polyisoprene, polyacrylate, polyacrylamides, and thermosets was not compatible with methacrylate derivatives up to now.

In the present work, instead of developing new comonomer structures, we have demonstrated that these cleavable units can still be DOT-based, provided that an auxiliary monomer is employed such as MA or PhMal, tweaking the overall radical reactivity and thus making an “impossible copolymerization” achievable.

Supported by CMMC modeling, the most promising results are obtained using PhMal-based terpolymerization, for which also the most reliable reactivity ratios could be determined. The combined experimental and modeling analysis revealed that MMA-DOT-MA or MMA-DOT-PhMal terpolymerizations can be designed by using less conventional initial conditions, delivering well-defined MA-DOT-MA or PhMal-DOT-PhMal sequences. The CMMC model could be applied to screen a wide range of synthesis conditions to identify the most optimal initial reactant loadings, delivering a MMA-rich polymer with a sufficiently high Mn as well as a sufficiently low Mn after degradation by hydrolysis, mimicking natural disposal.

Notably the designed drop in Mn (up to 25 times) is sufficiently high to create MMA segments that can be seen as oligomers, as experimentally confirmed. The analysis also revealed that DOT can be incorporated at the end of PMMA chains by chain transfer to monomer, although to a very limited extent.

The experimental conditions determined in silico with MMA were also used without any further tuning with several methacrylate derivatives to showcase the robustness of the approach. In particular, a water soluble poly(OEGMA) was prepared that showed similar degradation in water using cysteine as a degradation agent, mimicking physiological conditions making this polymer promising for biomedical applications. Furthermore, the polymer properties of the designed polymers are very interesting compared to those of the PMMA reference polymer.

The performed precision control thus facilitates chemical degradation by design for poly(methacrylates) in a fast manner and enhances the sustainability level of a polymer class less trivial to be chemically modified. We therefore delivered next-generation polymethacrylates with not only control in chain length during synthesis but also during hydrolysis-driven degradation at end-of-life.

Method

Materials and procedures

All reagents and solvents were used as received. Diphenic anhydride (98%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4) (99%), Lawesson reagent (97%), methyl methacrylate (99%), methyl acrylate (99.5%), butyl methacrylate (99%), poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate, phenylmaleimide (99%), anisole (99%), azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN), and anhydrous toluene (99.8%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ammonia solution (25%) was purchased from Fisher Chemicals. Dimethylformamide (DMF- for analysis) was purchased from Carlo Erba Reagents. Potassium hydroxide and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Merck. Deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Dibenzo[c,e]-oxepane-5-thione (DOT) was synthetized according to the literature procedure26,27.

The details of the experimental synthesis and degradation procedure are included in the Supplementary Information.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR)

1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance DPX 300 MHz spectrometer at 300 MHz (1H), 75.5 MHz (13C). Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as an internal standard. The 1H chemical shifts were referenced to the solvent peak for CDCl3 (δ = 7.26 ppm), and the 13C chemical shifts were referenced to the solvent peak for CDCl3 (δ = 77.16 ppm).

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

Molar masses were determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The apparatus was equipped with a 1260 Infinity pump (Agilent Technologies), a 1260 Infinity autosampler (Agilent Technologies), a 1260 Infinity UV photodiode array detector (Agilent Technologies), and a 1260 Infinity RI detector (Agilent Technologies). The stationary phase was composed of 2 PSS-SDV Linear M column and a precolumn at 40 °C. The mobile phase was THF at 1 mL min–1. Samples were solubilized in a mixture of THF and toluene (0.25 wt%) and filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE syringe filter (Agilent). The sample concentration was about 2.5 mg. mL-1. The system was calibrated using polystyrene (PS) standards in the range 100–400 000 g.mol-1, purchased from Agilent.

Poly(OEGMA) was analyzed using a SEC using DMF as solvent. The apparatus was equipped with a dual detection system (UV and RI). The stationary phase consisted of two mixed-bed columns (7.5 × 300 mm, Mixed-C, 200–2,000,000 g·mol−1) and one precolumn (7.5 × 50 mm, PL gel 5 μm guard column). The measurements were performed at 70 °C using a flow rate of 1 mL·min−1. The mobile phase (eluent) was dimethylformamide (DMF) containing 0.1 wt% LiBr and 0.2 vol% acetic acid. Calibration was carried out using poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) standards with molar mass ranges of 162–371,000 and 540–2,210,000 g·mol−1, respectively.

Modeling tools

The Gillespie-based kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) method is employed to simulate terpolymerization of which the main algorithm is included our recent review74. In addition, molecular information on monomer sequences is stored via coupled matrices, making the overall method coupled matrix-based Monte Carlo (CMMC) of which the main algorithm embedding the Gillespie-based algorithm has been published in full detail in Figueira et al.75 and De Keer et al.48. The reader is referred to the Supplementary Information for more details on the CMMC model.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within its supplementary information files. The simulation data generated in this study have been deposited in the database that could be found at this address: https://github.com/PsiXYZ/NatCommun_RingOpening2025. All other data are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Matyjaszewski, K. Macromolecular engineering: From rational design through precise macromolecular synthesis and processing to targeted macroscopic material properties. Prog. Polym. Sci. 30, 858–875 (2005).

Van Steenberge, P. H. M. et al. Visualization and design of the functional group distribution during statistical copolymerization. Nat. Commun. 10, 3641 (2019).

Delplace, V. & Nicolas, J. Degradable vinyl polymers for biomedical applications. Nat. Chem. 7, 771–784 (2015).

De Smit, K. et al. Multi-scale reactive extrusion modelling approaches to design polymer synthesis, modification and mechanical recycling. React. Chem. Eng. 7, 245–263 (2022).

Dogu, O. et al. The chemistry of chemical recycling of solid plastic waste via pyrolysis and gasification: State-of-the-art, challenges, and future directions. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100901 (2021).

Fiorillo, C. et al. Molecular and material property variations during the ideal degradation and mechanical recycling of PET. RSC Sustainability 2, 3596–3637 (2024).

Ikada, Y. & Tsuji, H. Biodegradable polyesters for medical and ecological applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 21, 117–132 (2000).

Schlaad, H. et al. Poly(2-oxazoline)s as smart bioinspired polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 31, 511–525 (2010).

Wang, Y. C., Yuan, Y. Y., Du, J. Z., Yang, X. Z. & Wang, J. Recent progress in polyphosphoesters: from controlled synthesis to biomedical applications. Macromol. Biosci. 9, 1154–1164 (2009).

Tardy, A., Nicolas, J., Gigmes, D., Lefay, C. & Guillaneuf, Y. Radical ring-opening polymerization: scope, limitations and application to (bio)degradable materials. Chem. Rev. 117, 1319–1406 (2017).

Pesenti, T. & Nicolas, J. 100th anniversary of macromolecular science viewpoint: degradable polymers from radical ring-opening polymerization: latest advances, new directions, and ongoing challenges. Acs Macro Lett. 9, 1812–1835 (2020).

Bossion, A., Zhu, C., Guerassimoff, L., Mougin, J. & Nicolas, J. Vinyl copolymers with faster hydrolytic degradation than aliphatic polyesters and tunable upper critical solution temperatures. Nat. Commun. 13, 2873 (2022).

Haussler, M., Eck, M., Rothauer, D. & Mecking, S. Closed-loop recycling of polyethylene-like materials. Nature 590, 423–427 (2021).

Eck, M. et al. biodegradable high-density polyethylene-like material. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 62, e202213438 (2023).

Lefay, C. & Guillaneuf, Y. Recyclable/degradable materials via the insertion of weak bonds using a comonomer approach. Prog. Polym. Sci. 147, 101764 (2023).

Gigmes, D. et al. Simulation of the degradation of cyclic ketene acetal and vinyl-based copolymers synthesized via a radical process: influence of the reactivity ratios on the degradability properties. Macromolecular Rapid Commun. 39 https://doi.org/10.1002/marc.201800193 (2018).

De Smit, K., Marien, Y. W., Van Geem, K. M., Van Steenberge, P. H. M. & D’Hooge, D. R. Connecting polymer synthesis and chemical recycling on a chain-by-chain basis: a unified matrix-based kinetic Monte Carlo strategy. React. Chem. Eng. 5, 1909–1928 (2020).

Lena, J.-B. et al. Insertion of ester bonds in three terpolymerization systems. European Polymer J. 181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2022.111627 (2022).

Tuten, B. T. et al. Visible-light-induced passerini multicomponent polymerization. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 58, 5672–5676 (2019).

Lena, J. B. et al. Degradable poly(alkyl acrylates) with uniform insertion of ester bonds, comparing batch and semibatch copolymerizations. Macromolecules 53, 3994–4011 (2020).

Agarwal, S. Chemistry, chances and limitations of the radical ring-opening polymerization of cyclic ketene acetals for the synthesis of degradable polyesters. Polym. Chem. 1, 953–964 (2010).

Bailey, W. J., Ni, Z. & Wu, S. R. Synthesis of poly-epsilon-caprolactone via a free-radical mechanism - free-radical ring-opening polymerization of 2-methylene-1,3-dioxepane. J. Polym. Sci. Part a-Polym. Chem. 20, 3021–3030 (1982).

Paulusse, J. M. J., Amir, R. J., Evans, R. A. & Hawker, C. J. Free radical polymers with tunable and selective bio- and chemical degradability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 9805–9812 (2009).

Huang, H. C., Sun, B. H., Huang, Y. Z. & Niu, J. Radical cascade-triggered controlled ring-opening polymerization of macrocyclic monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10402–10406 (2018).

Huang, H. C. et al. Radical ring-closing/ring-opening cascade polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12493–12497 (2019).

Bingham, N. M. & Roth, P. J. Degradable vinyl copolymers through thiocarbonyl addition–ring-opening (TARO) polymerization. Chem. Commun. 55, 55–58 (2019).

Smith, R. A., Fu, G., McAteer, O., Xu, M. & Gutekunst, W. R. Radical approach to thioester-containing polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1446–1451 (2019).

Bingham, N. M. et al. Thioester-functional polyacrylamides: rapid selective backbone degradation triggers solubility switch based on aqueous lower critical solution temperature/upper critical solution temperature. Acs Appl. Polym. Mater. 2, 3440–3449 (2020).

Spick, M. P. et al. Fully Degradable thioester-functional homo- and alternating copolymers prepared through thiocarbonyl addition-ring-opening RAFT radical polymerization. Macromolecules 53, 539–547 (2020).

Hepburn, K. S. et al. Thioester-rich degradable copolymers from a thionolactone and S-vinyl and P-vinyl monomers. Polymer, 311 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2024.127485 (2024).

Kiel, G. R. et al. Cleavable comonomers for chemically recyclable polystyrene: a general approach to vinyl polymer circularity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12979–12988 (2022).

Gil, N. et al. Degradable polystyrene via the cleavable comonomer approach. Macromolecules 55, 6680–6694 (2022).

Lages, M. et al. Degradable polyisoprene by radical ring-opening polymerization and application to polymer prodrug nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 14, 3311–3325 (2023).

Ivanchenko, O. et al. epsilon-Thionocaprolactone: an accessible monomer for preparation of degradable poly(vinyl esters) by radical ring-opening polymerization. Polym. Chem. 12, 1931–1938 (2021).

Plummer, C. M. et al. Mechanistic investigation of ε‑thiono-caprolactone radical polymerization: An interesting tool to insert weak bonds into poly(vinyl esters). Acs Appl. Polym. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.1021c00569 (2021).

Calderon-Diaz, A., Boggiano, A. C., Xiong, W., Kaiser, N. & Gutekunst, W. R. Degradable N-vinyl copolymers through radical ring-opening polymerization of cyclic thionocarbamates. ACS Macro Lett. 13, 1390–1395 (2024).

Rix, M. et al. Insertion of degradable thioester linkages into styrene and methacrylate polymers: insights into the reactivity of thionolactones. Macromolecules 56, 9787–9795 (2023).

Luzel, B. et al. Development of an efficient thionolactone for radical ring-opening polymerization by a combined theoretical/experimental approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27437–27449 (2023).

Ko, K., Lundberg, D. J., Johnson, A. M. & Johnson, J. A. Mechanism-guided discovery of cleavable comonomers for backbone deconstructable poly(methyl methacrylate). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9142–9154 (2024).

Yousefi, F., Mousavi, S. B., Heris, S. Z. & Naghash-Hamed, S. UV-shielding properties of a cost-effective hybrid PMMA-based thin film coatings using TiO(2) and ZnO nanoparticles: a comprehensive evaluation. Sci. Rep. 13, 7116 (2023).

Moens, E. K. C. et al. Progress in reaction mechanisms and reactor technologies for thermochemical recycling of poly(methyl methacrylate). Polymers, 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12081667 (2020).

Holmes, P. F., Bohrer, M. & Kohn, J. Exploration of polymethacrylate structure-property correlations: Advances towards combinatorial and high-throughput methods for biomaterials discovery. Prog. Polym. Sci. 33, 787–796 (2008).

Charleux, B., Nicolas, J. & Guerret, O. Macromolecules 38, 5485–5492 (2005).

Guegain, E., Guillaneuf, Y. & Nicolas, J. Nitroxide-mediated polymerization of methacrylic esters: insights and solutions to a long-standing problem. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 36, 1227–1247 (2015).

Zang, L., Wong, E. H. H., Barner-Kowollik, C. & Junkers, T. Control of methyl methacrylate radical polymerization via enhanced spin capturing polymerization (ESCP). Polymer 51, 3821–3825 (2010).

Jiang, N. C., Zhou, Z. & Niu, J. Quantitative, regiospecific, and stereoselective radical ring-opening polymerization of monosaccharide cyclic ketene acetals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5056–5062 (2024).

Gardoni, G. et al. Enhancing the incorporation of 2-methylen-1,3-dioxepane (MDO) into industrial monomers by the addition of crotonate comonomers. Polymer, 307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2024.127298 (2024).

De Keer, L. et al. Computational prediction of the molecular configuration of three-dimensional network polymers. Nat. Mater. 20, 1422 (2021).

Figueira, F. L. et al. Coupled matrix kinetic monte carlo simulations applied for advanced understanding of polymer grafting kinetics. Reaction Chem. Eng. 6. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0re00407c (2021).

D’Hooge, D. R., Reyniers, M. F. & Marin, G. B. The crucial role of diffusional limitations in controlled radical polymerization. Macromol. React. Eng. 7, 362–379 (2013).

Barner-Kowollik, C. & Russell, G. T. Chain-length-dependent termination in radical polymerization: Subtle revolution in tackling a long-standing challenge. Prog. Polym. Sci. 34, 1211–1259 (2009).

Woecht, I. & Schmidt-Naake, G. Free radical copolymerization of methyl methacrylate and n-phenyl maleimide in 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate. Macromol. Symposia 275, 219–229 (2008).

Bharel, R., Choudhary, V. & Varma, I. K. Preparation, characterization, and thermal-behavior of mma-N-aryl maleimide copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 54, 2165–2170 (1994).

Choudhary, V. & Mishra, A. Studies on the copolymerization of methyl methacrylate and N-aryl maleimides. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 62, 707–712 (1996).

Mohamed, A. A. & Hasan, M. E. H. Copolymerization Of N-phenyl maleimide with methyl acrylate, ethyl acrylate, methyl-methacrylate, and butyl methacrylate. Acta Polymerica 42, 544–547 (1991).

Tardy, A. et al. Radical copolymerization of vinyl ethers and cyclic ketene acetals as a versatile platform to design functional polyesters. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 56, 16515–16520 (2017).

Autzen, A. A. A. et al. IUPAC recommended experimental methods and data evaluation procedures for the determination of radical copolymerization reactivity ratios from composition data. Polym. Chem. 15, 1851–1861 (2024).

van Herk, A. M. & Liu, Q. The importance of the knowledge of errors in the measurements in the determination of copolymer reactivity ratios from composition data. Macromolecular Theory and Simulations, 33 https://doi.org/10.1002/mats.202400043 (2024).

Dube, M. A., Penlidis, A. & Reilly, P. M. A systematic approach to the study of multicomponent polymerization kinetics: The butyl acrylate/methyl methacrylate vinyl acetate example .4. Optimal Bayesian design of emulsion terpolymerization experiments in a pilot plant reactor. J. Polym. Sci. Part a-Polym. Chem. 34, 811–831 (1996).

Hakim, M., Verhoeven, V., McManus, N. T., Dube, M. A. & Penlidis, A. High-temperature solution polymerization of butyl acrylate/methyl methacrylate: Reactivity ratio estimation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 77, 602–609 (2000).

Hutchinson, R. A., McMinn, J. H., Paquet, D. A., Beuermann, S. & Jackson, C. A pulsed-laser study of penultimate copolymerization propagation kinetics for methyl methacrylate n-butyl acrylate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 36, 1103–1113 (1997).

McManus, N. T., Dube, M. A. & Penlidis, A. High temperature bulk copolymerization of butyl acrylate methyl methacrylate: Reactivity ratio estimation. Polym. React. Eng. 7, 131–145 (1999).

Yousefi, F. K. et al. Terpolymerization of triisopropylsilyl acrylate, methyl methacrylate, and butyl acrylate: reactivity ratio estimation. Macromolecular Reaction Engineering, 13. https://doi.org/10.1002/mren.201900014 (2019).

Haehnel, A. P., Schneider-Baumann, M., Hiltebrandt, K. U., Misske, A. M. & Barner-Kowollik, C. Global Trends for kp? Expanding the frontier of ester side chain topography in acrylates and methacrylates. Macromolecules 46, 15–28 (2012).

Hill, D. J. T., Shao, L. Y., Pomery, P. J. & Whittaker, A. K. The radical homopolymerization of N-phenylmaleimide, N-n-hexylmaleimide and N-cyclohexylmaleimide in tetrahydrofuran. Polymer 42, 4791–4802 (2001).

Barbon, S. M. et al. Synthesis and biodegradation studies of low-dispersity poly(acrylic acid). Macromol. Rapid Commun. 43, e2100773 (2022).

Gaytan, I., Burelo, M. & Loza-Tavera, H. Current status on the biodegradability of acrylic polymers: microorganisms, enzymes and metabolic pathways involved. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 105, 991–1006 (2021).

Kawai, F. Bacterial degradation of acrylic oligomers and polymers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39, 382–385 (1993).

Krishnamoorthy, S. et al. High Tg microspheres by dispersion copolymerization of N‐phenylmaleimide with styrenic or alkyl vinyl ether monomers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 49, 192–202 (2010).

Gao, W. P. et al. In situ growth of a stoichiometric PEG-like conjugate at a protein’s N-terminus with significantly improved pharmacokinetics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15231–15236 (2009).

Chen, J., Rizvi, A., Patterson, J. P. & Hawker, C. J. Discrete libraries of amphiphilic poly(ethylene glycol) graft copolymers: synthesis, assembly, and bioactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19466–19474 (2022). From NLM Medline.

Zhu, C., Beauseroy, H., Mougin, J., Lages, M. & Nicolas, J. In situ synthesis of degradable polymer prodrug nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 16, 2619–2633 (2025).

Guillaneuf, Y. & Castignolles, P. Using apparent molecular weight from SEC in controlled/living polymerization and kinetics of polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 46, 897–911 (2007).

Trigilio, A. D., Marien, Y. W., Van Steenberge, P. H. M. & D’hooge, D. R. Gillespie-driven kinetic monte carlo algorithms to model events for bulk or solution (bio)chemical systems containing elemental and distributed species. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 18357–18386 (2020).

Moens, E. K. C. et al. Coupled matrix-based Monte Carlo modeling for a mechanistic understanding of poly (methyl methacrylate) thermochemical recycling kinetics. Chemical Engineering Journal, 475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.146105 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-18-CE08-0019, ANR-22-CE06-0017, and ANR-23-CE06-0009) for PhD funding (N.G., B.L., and S.K., respectively). We thank the CNRS and Aix-Marseille University for support. D.R.D. acknowledges FWO Vlaanderen (G027122N) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.L., N.G. and S.K. performed the experiments. I.E. and M.E. performed the simulations. C.L., D.G., P.H.M.V.S., D.R.D., and Y.G. contributed to the bridged design approach. Material properties were determined by DM. The algorithm of the software was developed in earlier work by PHMVS and DRD. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation and review.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luzel, B., Efimov, I., Edeleva, M. et al. The successful impossible radical ring-opening copolymerization of thionolactones and methacrylates via an auxiliary third comonomer. Nat Commun 16, 9468 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64502-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64502-y

This article is cited by

-

Micro and nano plastics (MNPs) in agricultural soils: challenges for food security and environmental health

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)