Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) is an opportunistic foodborne pathogen responsible for gastrointestinal illnesses and life-threatening invasive infections. Antimicrobial resistance, virulence, and rapid adaptation to stressful environments in Lm lie in part on its mobile genetic elements (MGE). Here, we aim to characterize the MGE pool of a clinical Lm population using 936 genomes sampled across New York State (USA) from 2000 – 2021. We built a network based on sequence homology among putative MGEs. Within the network are communities of densely interconnected MGEs indicating high genetic similarity in their DNA regions. Although most connections involve the same MGE type, subsets within the network link different MGE types (plasmid-transposon, phage-plasmid). Phages and transposons did not share any genetic connections, suggesting impermeable barriers of exchange between them. Genes involved in stress tolerance are overrepresented in plasmids and transposons, and are mobile between vehicles. Analysis of long-read sequences of a subset of our dataset (n = 37) and publicly available, globally distributed complete genomes (n = 425) recapitulated the MGE connections we observed. Our findings reveal a structured but interconnected network of genetic exchanges between different mobile DNA vehicles. Genetic exchanges between MGEs shape Lm intra-species variation, adaptive potential, and rapid dissemination of clinically relevant traits at short timescales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) is an opportunistic foodborne pathogen responsible for non-invasive listeriosis (febrile gastroenteritis) with symptoms that include diarrhea, fever, headache, and muscle pain1. It can also cause life-threatening invasive infections such as severe sepsis, meningitis, or encephalitis that occurs when the bacterium invades normally sterile sites of the body, e.g., bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid2. Lm is a major public health threat due to listeriosis’ high mortality rate of 20–30%, with susceptible individuals such as the immunocompromised, pregnant, and elderly at high risk3. Lm has the remarkable ability to persist in the face of stressors in the environment, such as low and high temperatures, low and high pH, osmotic shock, high hydrostatic pressure, ultraviolet light, heavy metals, and biocides4,5. It can therefore contaminate food-processing environments and ready-to-eat foods that do not undergo treatment before consumption3. In addition, Lm has natural resistance to fosfomycin and fusidic acid in vitro6,7, although there is evidence that fosfomycin may nevertheless be used to treat listeriosis7. Multi-resistant Lm has been reported in food and food processing environments8. Lm’s ability to cause disease, rapidly adapt to disparate environments and acquire antimicrobial resistance (AMR) lies in part on traits carried by an assortment of mobile genetic elements (MGE)9,10,11.

In bacteria, genetic material is carried by different molecular vehicles – one or a few self-replicating chromosomes and a diverse array of MGEs, such as phages, plasmids, and transposons. MGEs are autonomous genetic agents that are capable of capturing DNA segments and moving them within and between cells12. The clonal nature of bacteria is therefore disrupted by MGEs through horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which enables cells to acquire exogenous DNA from a donor organism to the recipient organism even across large taxonomic distances13. HGT facilitates the rapid sharing of phenotypic innovations that evolved in one group of organisms with distantly related taxa that would otherwise take millions of years to evolve through mutations alone12,14. Although HGT events are often initially neutral or nearly neutral to the recipient15, many well-studied cases of HGTs involve a selective advantage to the recipient organism14. In bacterial pathogens, the consequences of MGE-mediated HGT can be profound. It can result to host switching16, multidrug resistance17, metabolic expansion18,19, and disease outbreaks20,21.

MGEs are horizontally exchanged between cells, with some MGE types able to replicate on their own22. Hence, studying individual MGEs as independently evolving elements, rather than considering all MGEs as a homogenous consortium present inside a bacterium, will bring important insight into how MGEs contribute to the genetic diversity in populations. Such an investigation has been previously carried out at high taxonomic scales encompassing the three domains of life, whereby DNA vehicles of the same type tend to share a gene pool with each other and are distinct from those found in other DNA vehicles, defining independent genetic worlds23. Yet, different types of vehicles are not totally independent, as DNA can, to some extent, move between different types of vehicles, i.e., between chromosomes and specific MGEs, as well as between MGEs24. Some genetic exchanges were indeed reported between different genetic worlds, showing that their evolutionary histories are not completely independent from each other23. In addition, the majority of phage structural variants is shaped by genetic exchange between phages and their respective bacterial hosts25. Across the bacterial domain, the newly discovered phage-plasmid elements mediate gene flow between plasmids and phages and foster the conversion between one or the other26. The same pattern was also observed between genera, as in the case of densely connected MGE types that facilitate inter-genus HGT in six major bacterial pathogens27. Given that HGT in bacteria is strongly favored between close relatives28,29, we expect that genetic exchanges between different MGE types must be common at lower taxonomic levels, i.e., species, subspecies, populations.

Here, we aim to characterize the putative MGEs (plasmids, phages, transposons) of a clinical Lm population using 936 genomes in New York State, USA, from 2000–2021. Altogether, our findings reveal a structured but interconnected network of genetic exchanges between different mobile DNA vehicles. We validated these results using long-read sequences of a subset of our dataset and publicly available, globally distributed complete genomes. Genetic exchanges between MGEs in Lm shape intra-species variation, adaptive potential, and rapid dissemination of clinically relevant traits at short timescales.

Results

Variable gene distribution within a local Lm population

We assembled 936 short-read draft genomes of Lm from listeriosis patients in New York State sampled from 2000–2021. This Lm population can be divided into four major lineages I–IV, of which 62.4% and 32.7% of the genomes belong to lineages I and II, respectively (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Lineages I and II are known to be frequently associated with human listeriosis, including numerous disease outbreaks worldwide30,31,32. Although lineages III and IV are more often reported in animal cases and are rarely associated with human listeriosis33,34, our dataset included 43 and three genomes of these lineages, respectively.

Each row of the matrix represents a genome assembly, whose phylogenetic lineage and clonal complex (CC) are indicated by the first and second row colors on the left of the matrix, respectively. Only CCs represented by at least 30 genomes have individual colors, while less common CCs alternate between two shades of gray. Each column represents an annotated genetic element, with specific names found at the bottom of the matrix. These genetic elements are grouped by colored blocks, shown at the top of the matrix. Blanks indicate the absence of the genetic element of interest in the genome assembly. Regarding inlA, colors inside the matrix indicate whether the gene was found truncated or full-length. Regarding hypervirulence factors, colors indicate whether all genes comprising the Listeria pathogenicity island (LIPI) were found. Regarding the other genetic elements, colors indicate in which DNA vehicle the genetic element is found in the genome. The category “multiple” in the gene columns refers to a gene that was detected multiple times in the same genome, but in different DNA vehicles. “multiple” in the phage column refers to the four genomes that harbor plasmidic phages in addition to other phages. For better visualization, the outgroup (Listeria innocua, Accession number: GCF_028596125) is not shown. Source data for the matrix are provided in Supplementary Data 2.

The population consisted of 143 different clonal complexes (CC). While the distribution of clonal complexes in a clinal dataset is the result of both intrinsic virulence and host characteristics, CC found at high frequency are often referred to as hypervirulent strains, such as CC1, CC6, CC2, and CC4. Of the known hypervirulent strains previously reported35, we found CC1 and CC6 as the most frequently detected in our dataset (13.9% and 6.3% of the genomes, respectively), while CC2 and CC4 were also present, albeit at lower frequencies (5.8% and 4.6%, respectively).

A total of 2,694,252 coding sequences (CDS) were present across the entire Lm dataset, with an average of 2878 CDS per genome assembly. We observed variation in the distribution of genes associated with CRISPR-Cas and restriction modification defense systems (Supplementary Fig. S1A). In terms of virulence genes, a truncated version of the inlA gene (surface protein internalin A) is known to be associated with hypovirulence35,36. Here, six genomes (one from CC1 and five from CC121) have a truncated version of inlA (Fig. 1). CC121 has previously been described as food-associated (rather than clinical) and harboring this truncated inlA gene35.

The Listeria pathogenicity islands 3 and 4 (LIPI-3 and LIPI-4) are known to be associated with hypervirulence35,36. We recovered all eight genes comprising the pathogenicity island LIPI-3 in 45.1% of the genomes, while 1.3% only harbor some gene(s) of the island (Fig. 1). Among the CCs represented by at least 30 genomes in our dataset, only four do not carry LIPI-3 (CC2, CC388, CC5, and CC11). We recovered all six genes comprising LIPI-4 in 20.8% of the genome assemblies, 61.5% of which also have LIPI-3 (such as genomes of CC217 and CC4). We detected LIPI-4 in all genomes of lineage IV and in nearly half of the genomes of lineage III, even though these lineages are known to be rarely associated with clinical diseases33,34. Several of the highly represented CC were associated with the LIPI-3 and/or LIPI-4, as expected. However, some clonal complexes found at relatively high frequency in our dataset did not harbor any LIPI (in particular, CC2, CC5, and CC11).

We next sought to determine the distribution of two sets of genes: AMR and stress tolerance genes (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Data 2). We detected the presence of 2098 AMR CDS in the entire Lm population, representing seven unique AMR genes conferring resistance to fosfomycin, macrolide, tetracycline, and multiple antimicrobial classes. We also identified genes associated with tolerance to biocides, heat, acid, and metal, which we collectively referred to as stress tolerance genes. Across the entire dataset, we detected 1269 CDS associated with stress tolerance, representing 19 unique genes.

The local Lm population carries a diverse mobile pool

We recovered a total of 2332 MGE in the Lm dataset from New York State: 2018 phages, 177 plasmids, 37 phage-plasmid (PP) elements, 100 transposons, but no integrons (Fig. 2B–D and Supplementary Data 2).

Phages were recovered in 98.2% of the genomes (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S1B), with sequence sizes ranging from 5,017 bp (phage sequences under 5 kb were not retained) to 109,699 bp (median = 13,121 bp).

While a previous study described the presence of a putative plasmid in 54% of a globally and ecologically diverse dataset of 1921 lineage I and II genomes37, we recovered plasmids in only 16.8% of the genomes, all of which belonged to lineages I and II. MOB-suite38 clustered these plasmids in 21 groups based on sequence similarity (Fig. 2C). Only one group (AA724) was predicted as being conjugative, while 11 groups were predicted as mobilizable, and nine as non-mobilizable. Plasmid sizes ranged from 1,006 bp to 93,316 bp (median = 13,527.5 bp). Based on replicon types, we can classify the Lm plasmids into different groups, with groups 1 and 2 being the major ones39. Group 1 plasmids carry rep25, while group 2 plasmids carry rep2637. In our dataset, we recovered a replicon gene in 169 of the 177 plasmids (Supplementary Data 3). The most common replicon genes were rep25 (48%) and rep26 (44%). Other replicons were also detected but at lower frequencies, such as rep32 (in 5% of genomes). BacAnt40 also identified seven other replicon genes, including three found in a chromosomic contig according to MOB-suite38.

A total of 37 PP elements consisted of contigs for which we could not precisely decipher their identity as they were fully annotated both as phage and plasmid. They may correspond to true PP elements26, phage misannotated as plasmid, or plasmid misannotated as phage.

Transposons were recovered in 10.4% of the genomes, all belonging to lineages I and II (Fig. 2D). To note, we could not decipher the family of one of these transposons, as BacAnt40 suggested six possible families for it. We refer to this transposon as TnUncertain. Hence, the 100 transposons can be classified into six families: Tn5422, Tn6188, Tn5801-like, Tn6000, Tn925, and TnUncertain. Tn5422 was the most common transposon family in our dataset, while the five other families were rare.

MGEs can exist as integrated within a chromosome, as an independent replicon (e.g., plasmids or free phage), or embedded within other MGEs (e.g., a transposon within a plasmid). Here, 83% of transposons were found in a plasmid, i.e., plasmidic transposon (Fig. 1). Remarkably, we found four prophages within the plasmid group AC310, i.e., plasmidic prophage (Fig. 1). Hybrid genome assembly of the long- and short-read sequences of the four isolates containing these plasmids recovered AC310 in two of the four isolates. The absence of AC310 in the other two isolates is likely the result of the loss of this plasmid since the time of the first DNA extraction. In the two isolates with AC310, we were able to validate the presence of the plasmidic prophages using BLASTn41 (Fig. 3).

A Two plasmids harboring a prophage in genomes H1 (from New York State and derived from long- and short-read sequencing data) and GCF_000438685.2 (from NCBI), with coordinates in kbp. These plasmids also harbor the transposon Tn5422. The presence of a relaxase and T4CP (type IV coupling proteins) genes in these plasmids was determined using oriTDB78. The plasmid of H1 is 100% identical to 62% of GCF_000438685.2’s plasmid sequence, with some genetic rearrangements. A total of 43% of GCF_000438685.2’s plasmid sequence is 99.88% identical to another plasmid of H1, assembled on another contig. B Genetic comparison of both plasmidic prophage sequences, whose genes were functionally annotated by Pharokka84. VirSorter2 (VS2)79 and CheckV’s81 annotations are also presented. VS2’s final scores were of 0.927 and 0.800 for H1 and GCF_000438685.2 prophages, respectively.

MGEs as vehicles of stress tolerance genes

We next identified the DNA vehicles carrying each AMR and stress tolerance gene (Figs. 1 and 4). For example, a gene may be present within the chromosome (with no associated MGE), within a transposon that is integrated inside the chromosome, or within a transposon that is integrated inside a plasmid.

A Percentage of annotated antimicrobial resistance (AMR) coding sequences (CDS), stress tolerance CDS, and other CDS in each DNA vehicle. Genes encoding hypothetical proteins are not included, nor are those found in PP elements. “Others” refers to all genes annotated by Prokka63, except AMR genes, stress tolerance genes, and hypothetical genes. Colors of vehicles correspond to those in Fig. 1. Genes can be found on three types of DNA vehicles: chromosome, phage, plasmid. “Phage” includes both free phage and prophage. Numbers at the top of each bar are the sum of percentages for all vehicles carrying each category of genes. B Percentage of plasmids and transposons that carry at least one AMR or stress CDS. C Number of genes found always in the same vehicle (1) or in several vehicles (2 to 4). In A and C “NS” and “***” stand for non-significant and a p-value < 0.001, respectively, when comparing AMR genes (or stress tolerance genes) with the category “Others” (two-sided Fisher’s exact test). The p-values are <2.2e-16 in A and 3.695e-05 in panel C. Source data are provided in a separate file.

Of the 2098 AMR CDS we detected in the New York Lm dataset, 99.8% were not associated with any MGE (n = 2094), while four were found in a chromosomic transposon (Fig. 4A). Of the 1269 stress tolerance CDS, 78.1% were not associated with any MGE (n = 991), while the rest were in chromosomic transposons (n = 11), or plasmids (n = 265, including 83 in a plasmidic transposon) (Fig. 4A). As all clpL CDS (heat resistance) were found in plasmids, we presume that the two found in PP elements actually correspond to plasmids. The 83 CDS in plasmidic transposon correspond to cadC (cadmium resistance) in Tn5422, whose association has previously been reported42,43. However, six other Tn5422 carriers of cadC were not located in a plasmid. For other CDS (i.e., CDS other than AMR, stress tolerance, or hypothetical), 99.6% were not associated with any MGE. Overall, when comparing the number of CDS in MGE versus in non-MGE, AMR CDS do not show a different pattern than other CDS (p value = 0.16, two-sided Fisher’s exact test), in contrast to stress tolerance CDS (p value = 2.2e−16, two-sided Fisher’s exact test). This difference between stress tolerance CDS and other CDS is due to a large excess of the former in plasmids and transposons. When looking from the plasmid’s perspective (Fig. 4B), we found that 64.4% of them carry at least one stress tolerance CDS, while none carry any AMR CDS. For transposons, 94.0% carry at least one stress CDS, while only 4% carry at least one AMR CDS (all tetM). A substantial portion of the transposons (88.3%) that carry stress tolerance CDS are plasmidic transposons.

Interestingly, the same gene is not always found in the same DNA vehicle type among different genomes (Figs. 1 and 4C). While all AMR were always found in non-MGE locations, eight of the 19 stress tolerance genes were found in two different types of DNA vehicles, and one (cadC) was detected in four different types of vehicles. This variety of vehicle types for the same gene suggests that these genes undergo frequent exchanges between vehicles. As a comparison, among the 1792 genes in the “Others” category, 93.2% were always found in a single vehicle type, while the rest underwent exchanges between two to four vehicle types. This result indicates that AMR genes do not undergo more exchanges between DNA vehicle types compared to other genes, although the low number of AMR genes (eight) does not confer statistical power (p value = 1, two-sided Fisher’s exact test). Stress tolerance genes, however, have an excess of genes experiencing exchanges between multiple DNA vehicles (p value = 3.695e−05, two-sided Fisher’s exact test).

High genetic connectivity between different MGE types

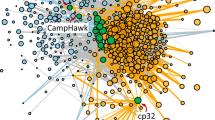

We next sought to identify genetic connections between MGEs based on shared DNA sequences. For this, we generated a network composed of 2332 nodes, whereby each node represents an MGE (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S2). We note that a phage can be split between several contigs, and can therefore be found across several nodes. Two nodes are connected by an edge if they show sequence similarity in at least 200 bp using BLASTn search41. Sequence similarity can result from either common ancestry or horizontal transfer of genetic material. However, distinguishing horizontal transfer from vertical inheritance in genetic connections between the same MGE type requires additional analysis beyond the goals of this study. Nonetheless, we can be certain that connections between different MGE types are the result of horizontal transfer because different MGE types have independent evolutionary origins.

Each node represents an MGE annotated in a genome assembly. Node colors indicate the types of MGE. Because phages were not reconstructed, several nodes may correspond to different parts of the same phage. Each pair of MGE with sequence similarities on at least 200 bp are connected by edges. Edge colors indicate the type of connections. Positions of the nodes in the network were assessed by the algorithm “Prefuse force directed layout” in Cytoscape82 using the log10 of the bitscore of the BLASTn41 hits as edge weight. Subnetworks are labeled A – H. Communities within subnetwork A are circled and numbered 1–3. Clustering coefficient = 0.725, network density = 0.327. Density per community and per MGE type are presented in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Overall, 98.18% of the connections involved the same MGE types (phage-phage, plasmid-plasmid, transposon-transposon, PP-PP), while 1.23% are transposon-plasmid connections, 0.05% are phage-plasmid connections, and 0.54% are phage-PP or plasmid-PP connections. No phage-transposon connection was observed. We identified eight distinct subnetworks, defined as groups of nodes that are completely separated from the other nodes (labeled A–H in Fig. 5). Only seven MGEs did not exhibit any sequence similarity with other MGEs in our dataset (these are not labeled in Fig. 5).

The largest subnetwork (labeled A in Fig. 5) contains 61.9% of all the nodes and all four MGE types (phages, plasmids, transposons, PP). Yet this giant component is structured. We identified three communities within this subnetwork A (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S3). A community is defined as highly connected nodes (intra-community connections) linked to each other by just a few and weaker connections (inter-community connections)44,45. Communities 1 and 2 can be described as phage communities. Community 1 is exclusively composed of phage nodes, while community 2 has a vast majority of phage nodes (99.7%) but also three PP elements that may likely be true phages. Community 3 is the most complex, as it can be defined as a plasmid-transposon-phage community and consisting of 167 plasmids, 89 Tn5422 transposons, 4 phage sequences, and 29 PP elements. Plasmid-transposon connections are expected as transposons are commonly inserted in plasmids46, as it is the case for 83 of the 89 Tn5422 of this community. Plasmid-phage connections, however, were more intriguing. The ones found within community 3 were due to the presence of the four plasmidic prophage, but other phages were also connected to plasmids between communities 2 and 3.

Another subnetwork of interest is subnetwork C, a plasmid-transposon subnetwork, composed of five transposons, all of which are members of the Tn6188 family, and the plasmid AC679. Although we expect plasmidic transposons to cluster with their respective plasmid carrier, as observed in community 3 of subnetwork A, none of these five transposons are found in AC679, nor in any other plasmid we annotated. The transposons were connected to the plasmid by a 967 bp long BLAST hit with 71.2% sequence identity. Hybrid genome assembly of the long- and short-read sequences of the six isolates containing these MGEs allowed us to confirm the presence of these six MGE and the existence of the plasmid-transposon connection, comprising a gene annotated as slmA (Nucleoid occlusion factor SlmA) in the transposons but as a hypothetical protein in the plasmid (Supplementary Fig. S4A). We interpreted this connection as resulting from a horizontal transfer between the Tn6188 family and the AC679 plasmid, although we could not assess the directionality of transfer.

Subnetwork E (transposon subnetwork) may help decipher the classification of TnUncertain, which was found at the center of the subnetwork. TnUncertain is connected to all three Tn5801-like elements as well as to Tn925. While Tn925 was a candidate for TnUncertain according to BacAnt40, the program did not suggest Tn5801-like as a possibility. Interestingly, no connection was observed between Tn5801-like and Tn925. This subnetwork suggests that TnUncertain is a chimera between the families Tn5801-like and Tn925, although we cannot ascertain its origins. The hybrid assemblies of three isolates containing either TnUncertain, Tn925 or Tn5801-like allowed us to confirm that TnUncertain is not the result of misassembly, but truly a chimera of the two others (Supplementary Fig. S4B).

Genetic connectivity of MGEs in a high-quality global Lm dataset

In order to confirm the existence of these various inter-MGE type connections that we recovered in the New York Lm population, we repeated this analysis on a global dataset consisting of high-quality genomes. Such analysis ensured that we avoid connections that could be the result of misassembly or misannotation. We combined 425 publicly available complete genomes (Supplementary Data 4) and 37 genomes from New York that were assembled from short- and long-read sequencing data (or hybrid assemblies) (Supplementary Data 5). We recovered a total of 1317 MGEs across 447/462 genomes: 1077 phages, 119 transposons, 119 plasmids, and 2 PP elements. The network built from sequence similarity of these MGEs recovered all major subnetworks and communities that we had previously identified in the New York dataset (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S5). Subnetwork A still contained communities 1 to 3, but subnetworks B and C are now part of subnetwork A. Subnetwork B is connected to subnetwork A through a single phage, while subnetwork C is connected to subnetwork A through a single plasmid. Altogether, this giant component of the network now contains 98.9% of all 1317 MGEs. While we were unable to recover any phage-plasmid connections within the 37 hybrid assemblies alone, except for those due to plasmidic prophage, we recovered many such connections across this high-quality global dataset of 462 genomes. In total, 0.13% of the genetic connections were phage-plasmid, and 0.40% were phage or plasmid connected to PP elements (Supplementary Fig. S6).

MGEs annotated from NCBI genomes are shown with diamonds (n = 425 genomes), while the ones annotated from the New York genomes generated in this study are shown with ellipse (n = 37 genomes). All subnetworks and communities from Fig. 5 that were recovered here follow the same labeling. Clustering coefficient = 0.921, network density = 0.316. Density per community and per MGE type in Supplementary Fig. S6.

The high quality of these genome sequences also allowed us to compare the phages in this network with all known Lm phage genomes available in NCBI. We recovered sequence similarities with known phages in all phages of community 2 and in the phage connecting subnetwork B to subnetwork A (Supplementary Data 6). A genetic map of a randomly picked phage from each subnetwork/community supports the veracity of these phage annotations, as they all contain genes encoding functions associated with phage (Supplementary Fig. S7). Interestingly, both PP elements harbor some sequence similarities with known phages on part of their length (Supplementary Fig. S8). To note, they also contain the transposon Tn5422 and a putative conjugative region (recovered with ICEfinder47).

Discussion

In this study, we describe the pool of MGEs (plasmids, phages, transposons) and their cargo genes present in Lm genomes. In the two datasets we analyzed (New York State short-read genomes [n = 936] from clinical human sources and high-quality global genomes [n = 462] from various geographical and ecological sources), we built networks based on sequence homology among the MGEs. Although most connections involve the same MGE type, we found densely interconnected MGEs and that subsets within the network link different MGE types (plasmid-transposon, phage-plasmid). Our findings reveal a structured but interconnected network of genetic exchanges between different mobile DNA vehicles. That such MGE connections were observed from both datasets suggests that these patterns are relatively conserved at the population level.

While several highly represented CCs were associated with the previously described hypervirulent factors LIPI-3 and/or LIPI-4, as expected, some CCs found at relatively high frequency in our dataset did not harbor any LIPI (in particular CC2, CC5, and CC11). In contrast, we were surprised to observe LIPI-4 in all genomes of lineage IV and in almost half of the genomes of lineage III, as these isolates are rarely associated with clinical cases. The lack of association between these virulent strains and these hypervirulent factors may suggest the presence of other yet unidentified elements conferring virulence. Interestingly, CC5 is the CC that harbors phage-plasmid connections with the highest number of different CCs, indicating that this CC might drive phage-plasmid exchanges not only within CC5 but also throughout the Lm population (Supplementary Fig. S9). In this sense, two of the plasmidic phages and the plasmid connecting communities 2 and 3 (Fig. 5) belong to CC5. However, we could not find any association between hypervirulence and the presence of phage-plasmid connections (Supplementary Fig. S9), nor with MGE content (as shown by the widespread distribution of each MGE family among genomes throughout the phylogeny in Fig. 1).

Another important finding from our study is that genes involved in stress tolerance are differentially distributed not only among Lm lineages but also among MGE types. In terms of lineages, our result that stress tolerance genes are differentially distributed among clinical Lm lineages are consistent with reports of MGEs in short-read Lm genomes from dairy farms11. The prevalence of stress tolerance genes in lineages I and II may partly explain why these two lineages are the most common in human listeriosis cases. While human food is carefully processed and cooked, these stress tolerance genes increase the chance of bacterial survival during these processes. The stress tolerance genes are overrepresented in plasmids and transposons, and are mobile between vehicles. Our results are consistent with previous studies reporting the presence of stress tolerance genes on different types of MGEs48,49,50. Considering that stress tolerance genes were absent in genomes belonging to lineages III and IV, as were plasmids and transposons, it is tempting to explain the absence of stress tolerance genes by the absence of these MGE types. However, 78.2% of the stress tolerance genes in lineages I and II were present in the chromosome. Thus, we suggest that the mobility of stress tolerance genes, via plasmids and transposons, might be necessary to maintain the stress tolerance genes, including those in chromosomes. In addition, the highly represented plasmid groups (AC309, AA724, AC310) were associated with stress tolerance genes, thus suggesting that their success in the population might be due to the evolutionary advantage the MGEs bring to their bacterial hosts through these genes. Interestingly, two of the four plasmids containing prophage sequences were lost between the short-reads and the long-reads sequencing time lapse, suggesting that such mosaic elements might have a high cost for the host. No stress tolerance gene was recovered in the plasmid group AC308 (the fourth most common plasmid group), raising the question of the reason for its apparent success in the population.

That DNA vehicles tend to form more frequent connections with others of the same vehicle type is in line with the notion of genetic worlds defined by Halary et al. 23 The authors built a genetic similarity network composed of chromosomes, phages, and plasmids and encompassing numerous phyla of Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes. Across the three domains of life, a giant network consisting of three vehicle types was represented but structured in communities, with each community often consisting of a single type of vehicle with its own distinct gene pools23. The network of MGEs within a single species that we described in our study mirrors the results that the authors Halary et al. obtained at higher taxonomic levels. Thus, we showed that even at lower taxonomic levels, whereby we expect more horizontal transfers, DNA vehicles are part of their own genetic worlds.

Yet, these genetic worlds are not completely impermeable, as illustrated by the connections linking different MGE types. Such connectivity is not confined to specific Lm lineages and hence transcends clonal patterns of inheritance. However, we did not find a single connection between phages and transposons, which suggests that there are strong barriers to genetic exchanges between these two genetic worlds. Of particular interest are the genetic connections we observed between phages and plasmids, as they are consistent with the recent discovery of PP elements, which exhibit characteristics of both phages and plasmids and promote gene flow between them26,51. To our knowledge, such elements have never been reported in Lm. Although no AMR nor stress tolerance genes were annotated in phages in our New York State dataset, the presence of possible PP elements and of phage-plasmid connections raises the concern of the possible acquisition of such genes by phages, which could enhance the dissemination of these genes26. While PP elements were first described as phage present as extrachromosomal plasmids that replicate in line with the cell cycle52, their evolutionary origin is unclear. Such elements could be the result of the integration of one entire MGE into the other, to which various structural variations could follow, leading to a more genetically mosaic element, or the result of recurrent acquisitions of single (or a few) genes of one MGE type into the other, which could take place through non-homologous end joining or through homologous recombination driven by insertion sequences for example26. Here, we report three types of candidates that may correspond to different steps of such mechanisms: (i) MGE (clearly annotated as phage or plasmid) involved in phage-plasmid connections, some of which could become PP elements after the acquisition of additional genes (e.g., Supplementary Fig. S4), (ii) plasmids containing a prophage, which could correspond to a recent phage acquisition, and thus true PP elements26 (e.g., Fig. 3), and (iii) the sequences we referred to as PP elements, some of which might correspond to PP elements26. To note, only two PP elements were recovered in the high-quality global dataset, suggesting that most PP elements in the local dataset (n = 37) likely correspond to either phage or plasmid rather than true PP elements. Genetic maps of these two PP elements recovered in the high-quality global genomes strongly suggest that these elements are bona fide phage-plasmid elements (Supplementary Fig. S8).

The impact of such genetic exchanges among MGEs is threefold: (i) large variation in genetic content among distinct co-circulating lineages; (ii) adaptive potential that can be rapidly disseminated at short evolutionary timescales16,17,18,19,20,21; and (iii) genetic mosaicism of DNA vehicles that lead to the confluence of traits, especially those relevant to human health and disease26,51,53. Altogether, our findings add an extra layer of complexity in the forces governing HGT in Lm that extend beyond the transfer between donor and recipient cells. More generally, mosaicism in MGE illustrates the interconnected evolutionary histories of a priori distinct entities. Such mosaicism also raises the problem of MGE annotation methods, as each tool is generally designed to annotate a single type of MGE, assuming that each MGE type belongs to a well-delineated category. Development of new tools that annotate multiple MGEs simultaneously, including mosaic elements, will be particularly useful.

While we did not carry out quantifications of horizontal transfer rates across MGEs, previous findings recovered heterogeneity in HGT rates and donor-recipient preferences among Lm lineages54. In a previous analysis of HGT between the core genomes of 81 Swiss, German, and Dutch Lm isolates representing the four Lm lineages, isolates transfer preferentially with isolates of the same lineage, with higher rates within lineage III54. In inter-lineage transfers, lineage III was the main donor, but lineages I and II were rarely involved in such transfers54. The authors of this previous study inferred that these transfers must occur through transformation, as they found evidence that phages were not involved. Our observation regarding the content in defense systems and in MGEs of the New York genomes (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1) is consistent with a higher transformation rate in lineage III, and with the presence of genetic conflicts between transformation and MGE55: CRISPR-Cas9 genes are associated with lineage III, while restriction modification systems and MGEs are associated with lineages I and II (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1A). However, natural transformation has never been observed in Lm despite the presence of genes described as being involved in competence in other species; some known competence genes have been shown to be involved in different functions in Lm56,57,58. For example, it was shown that comK and its transcription factor σH are involved in intracellular growth in Lm57,59. Hence, whether these genes are also involved in competence in Lm under specific, yet undiscovered conditions, remains to be assessed. An alternative mechanism for genetic transfer the authors did not discuss is the possible involvement of plasmids54. In our study, we did not detect any plasmid in lineage III, i.e., the lineage with the highest HGT rate54, which suggests that plasmid is not likely the main vector of HGT in this particular lineage. Future work should focus on the association between HGT rates of core genes and of MGE with factors explaining heterogeneity in HGT rates across Lm lineages.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, the use of short-read draft genome sequences in the first part of the study (New York State only) may fail to identify the entire pool of MGEs and their cargo genes. The stringency in the MGE annotation we used, and importantly, the fact that gene groups (AMR, stress tolerance, and other genes) were treated equally, alleviates this limitation, and thus, we are confident of the patterns we observed. Moreover, our analyses of the high-quality global genomes validated our results from the short-reads dataset. Second, we included three types of MGE (plasmids, transposons, and phages) in the networks, yet other MGE types have been described in Lm, such as Listeria genomic islands (LGI) and genomic islets (integrative and conjugative elements, ICE), in which genes involved in resistance genes were also reported48,49,50. Future studies could analyze their dynamics together with MGEs already included in the present study to have a more comprehensive picture of the genetic exchanges between all MGE types in Lm. Third, only a single isolate was obtained from each patient, which overlooks the bacterial genetic diversity within the host60. A single isolate from a host is but a snapshot of the numerous transfer donors and recipients in the microbial community existing within the host. Moreover, the low number of genomes from lineage III and IV in our dataset should motivate a broader sampling of Lm in non-human sources, which can potentially uncover novel, cryptic or poorly studied MGEs and their gene cargo. Lastly, identification of MGE variants greatly relies on the composition of known MGEs in current databases and the search algorithms used; therefore, novel variants may be missed. Nonetheless, our work provides a portrait of the standing diversity of MGEs in clinical Lm, which is useful in understanding the bacterial genetic and evolutionary features that make Lm a highly resilient and persistent pathogen in various environments.

Methods

Genomic dataset from New York State surveillance

We used a total of 936 Lm short-read genome sequences that were obtained from the New York State surveillance of foodborne pathogens from 2000 – 2021 (Supplementary Data 1). Genomes were generated from Lm isolates that were received from New York health care providers and collected from individuals diagnosed with Lm infection (Supplementary Data 1). Samples were submitted to the Wadsworth Center, the public health laboratory of the New York State Department of Health. Samples used in the study were subcultured isolates that had been archived in the routine course of Lm surveillance. No patient specimens were used, and patient health information was not collected. Therefore, informed consent was not required. This work has been determined to be exempt from human subject research by the Wadsworth Center Institutional Review Board.

For each isolate, DNA was extracted from overnight cultures in tryptic soy media using QIAamp DNA Blood Minikit kit or QIAamp 96 DNA QIAcube HT kit following manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). DNA library preparation followed protocols for Nextera XT or Nextera DNA Flex kits (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA). DNA samples were sequenced at the Wadsworth Center either on a MiSeq system using 2x250bp reads or on a NextSeq system using 2x150bp reads. Library preparation and short-read sequencing were carried out at the Advanced Genomic Technologies Cluster (AGTC) at the Wadsworth Center.

De novo assembly of paired-end reads was done using Shovill v.1.1.0 (https://github.com/tseemann/shovill). We employed the --trim flag for trimming of adapter sequences. We used QUAST v.5.0.261 and CheckM v.1.1.362 to assess the quality of assembled genomes (Supplementary Data 1). All the 936 assemblies that were retained passed the following inclusion criteria: ≥90% genome completeness, ≤5% genome contamination, ≤200 contigs, and N50 ≥40,000 bp.

Genome annotation of New York Lm genomes

We used Prokka v.1.1.14.663 to annotate assembled genomes and one Listeria innocua genome that we used as an outgroup (Accession no. GCF_028596125). We ran Panaroo v.1.2.764 with the flag –strict option to identify the core genes, which we defined as those genes present in 99% of the assemblies. We obtained a total of 7542 orthologous gene families that made up the pan-genome65, of which 2421 were core genes. We used AMRFinderPlus v.3.11.4 to identify AMR genes66. The option –plus allowed us to detect genes associated with tolerance to biocides, heat, acid, and metal, which we collectively referred to as stress tolerance genes. Annotations by Prokka and AMRFinderPlus were harmonized, favoring the annotation of AMRFinderPlus when the same coordinate was annotated by both software programs. Any CDS annotated by Prokka but not by AMRFinderPlus belongs to the category “Other”. Among these “Other” CDS, some contained names identical to AMR or stress response genes, but we left them in the category “Other” as they were not annotated by AMRFinderPlus. When comparing the different gene categories (AMR, stress CDS, and “Other”; Fig. 4), these ambiguous CDS were excluded from the “Other” category. Truncated inlA gene, associated with hypovirulence, was defined as those shorter than 2300 bp35,36. The Lm genome assemblies were uploaded to the Institut Pasteur BIGSdb Listeria database (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/listeria/)67 for curation to determine the identity of major lineages and CC. We also used this database to identify the presence of the eight and six genes comprising the pathogenicity islands LIPI-3 or LIPI-4. Lineages are defined based on sequence variation in 1500 out of 1748 housekeeping loci as defined previously31.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of New York Lm genomes

We used MAFFT v.7.47168 implemented in Panaroo64 to align 2337 of the 2421 core genes that passed Panaroo’s filters. These filter are used for selection of phylogenetic informative regions and remove sources of bias such as highly variable characters. We extracted the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) from the core sequence alignment using SNP-sites69. We obtained a total of 472,156 SNPs, which were used as input in IQ-TREE v.2.1.470 to build a maximum likelihood phylogeny. We used the option -m MFP in IQ-TREE to select the most appropriate nucleotide substitution model using ModelFinder71. We used the options -B 1000 to set the number of bootstrap replicates to 1000 and -bnni to use the ultrafast bootstrap approximation UFBoot272. We used the best fit model of general time reversible nucleotide substitution model73 with an ascertainment bias correction and FreeRate heterogeneity74 (GTR + ASC + R6). The resulting tree was rooted on the outgroup (L. innocua GCF_028596125). Trees were visualized using the R75 package ape76.

Annotation of putative MGEs in New York Lm

We used BacAnt v.3.140 with default settings to annotate transposons, integrons, and plasmid replicon types.

To annotate plasmids, we used the MOB-recon tool v.3.1.0 from the MOB-suite, which has the advantage to cluster, reconstruct and type putative plasmid sequences from the assembled genomes38. This allowed us to identify whether each contig belongs to the chromosome or to a plasmid. In addition, MOB-suite shows high precision, which means that one can expect most of the predicted plasmids to be true plasmids38,77. In total, 437 contigs ranging from 1006 bp to 93 kbp in length were identified as belonging to a plasmid. These contigs were reconstructed into 179 plasmids, with lengths from 1673 bp to 146 kbp. We will refer to these reconstructed plasmids as “plasmids”. For the two plasmids containing phage sequences we investigated more thoroughly (Fig. 3A), we used oriTDB to identify relaxases and type IV coupling proteins (T4CP) genes78.

To annotate phages, we proceeded in three steps, following the protocol developed by the authors of VirSorter279 (https://www.protocols.io/view/viral-sequence-identification-sop-with-virsorter2-5qpvoyqebg4o/v3?step=1) and the benchmark published by Hegarty et al. 80. We first ran VirSorter2 v.2.2.4 to identify phage sequences, followed by CheckV v1.0.3 on the predicted phage sequences to obtain high sequence quality and to trim potential host regions left at the ends of proviruses81. Next, we ran VirSorter2 a second time on these CheckV-trimmed sequences. VirSorter2 annotates a phage sequence as either a partial contig (in such a case, it is a prophage) or a full contig (which can either be a prophage or a free phage). We will collectively refer to them as “phage”. In total, we obtained 2723 sequences annotated as phage. Although VirSorter2 has high recall compared to other phage detection tools, its precision mirrors a relatively high rate of false positives, similar to other phage annotation tools79. In order to reduce the number of false positives, we applied three filters: (i) we filtered out phages for which CheckV81 could not identify a single viral gene, (ii) we filtered out phages fulfilling at least one of the three tuning removal rules established by Hegarty et al. to accurately identify viral sequences80, and (iii) we removed phages smaller than 5000 bp. All phages that do not pass the first filter did not pass the second filter either.

In all, 37 contigs ranging from 1507 bp to 37 kb were fully annotated as phage (passing at least the first two phage filters), but these were also annotated as plasmid by MOB-suite38. We decided to keep these 37 sequences in our analyses, regardless of their size, but we refer to them as PP elements, and we removed them from the phage and the plasmid categories. We left the possibility of partial contigs annotated as phage on a plasmid contig, which would correspond to a prophage integrated in a plasmid (i.e., plasmidic prophage). Doing so, we were left with 2018 sequences annotated as phage and 400 contigs annotated as plasmids (reconstructed as 177 plasmids).

Lastly, the MGE and gene annotations were merged by examining overlaps between their genomic coordinates.

MGE network reconstruction

To detect genetic similarities between MGEs, we extracted all the annotated MGEs across the entire New York dataset and concatenated them in a single FASTA file. We ran BLASTn41 with the options -evalue 0.00001 and –max_hsps 10 on the concatenated fasta file as both query and subject. We removed self-hits and hits <200 bp from the output. Next, we kept only the best hit (defined here as the sequence with the best bit score) for each pair of MGEs. For plasmids, if we obtain BLASTn hits on several contigs that belong to the same plasmid, as reconstructed by MOB-suite, we kept only one of these contigs. Thus, each plasmid is represented by a single node in the network, regardless of how many contigs it is split across. However, because VirSorter2 does not reconstruct phages, several contigs may correspond to the same phage element. Whether several contigs belong to the same phage or not is therefore uncertain. Hence, we showed one node per phage sequence, i.e., a phage sequence can either be a full contig or a part of a contig. Altogether, we obtained a table with the top BLASTn hit connections for each pair of MGE. We used this table as an input for the function graph_from_data_frame() of the R package igraph (https://igraph.org/) in order to build an undirected graph. The resulting network was then visualized in Cytoscape82 with the algorithm “Prefuse force directed layout” using the log10(bitscore) as edge weight. We detected communities within the network44,45 using the function cluster_fast_greedy of the R package igraph. A community, in the context of network science, is defined as a subset of nodes within the network that are more densely linked among each other than with nodes in the rest of the network45.

High-quality global dataset of Lm genomes

We retrieved 425 complete Lm genomes available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) RefSeq database as of January 2025 (Supplementary Data 4). These genomes were derived from various geographical locations and ecological sources. We also selected a few isolates from our New York dataset for long-read sequencing (Supplementary Data 5). We selected 37 isolates representing the major subnetworks and communities, and that contain MGEs of interest, such as plasmidic phage, TnUncertain transposon, and the two transposons it is connected to.

The 37 isolates were grown on brain heart infusion broth (BD Difco; Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) at 37 °C for 24 h. For long-read sequencing of the 37 isolates, DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy 96 PowerSoil Pro QIAcube HT Kit (#47021). Prior to extraction, samples were lysed using MagMAX Microbiome bead beating tubes. DNA samples were prepared for whole genome sequencing using the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Native Barcoding Kit (#SQK-NBD114). Long Fragment Buffer was used to promote longer read lengths. Sequencing was performed on the PromethION 2 Solo platform using a FLO-PRO114M Flow Cell (R10 version) with a translocation speed of 400 bps. Base calling was performed on the GridION using the super-accurate basecalling model with barcode trimming enabled. DNA extraction and long-read sequencing was carried out at SeqCoast Genomics (Portsmouth, New Hampshire, USA).

For the 37 long-read sequences, adapters were removed using porechop v.0.2.4, and reads were filtered using filtlong v.0.2.1 with the options --min_length 1000 to keep only reads longer than 1000 bp, --keep_percent 90 to retain only 90% of the best reads, and --min_mean_q 7 to retain only reads with quality above 7. These filtered long reads, together with their corresponding Illumina-sequenced short-read sequences, were assembled with unicycler v.0.5.0. The resulting hybrid assemblies contained 1 to 18 contigs. All 37 hybrid genome assemblies had genome completeness between 99.34 and 99.54%, with the exception of one isolate at 98.73%, and all assemblies had less than 0.54% of genome contamination, calculated using CheckM62 (Supplementary Data 5).

We refer to this second dataset (425 genomes from NCBI plus 37 hybrid-assembled genomes sequenced in this study, for a total of 462 genomes) as the high-quality global dataset. MGE annotation and network analyses on this second dataset followed the same methods described above. For plasmids of the NCBI genomes, however, we used the provided annotation. The phages that we annotated across the 462 genomes were compared with known Listeria phages by searching against all 222 complete genomes (available as of February 2025) of Listeria phages available in NCBI using BLASTn41 and e-value threshold of 0.00001. To determine the presence of integrative and conjugative elements (ICE) in the 37 hybrid-assembled genomes, we ran ICEfinder47; results showed that ICE was present in six genome assemblies (Supplementary Data 7). However, although prophages were previously reported in some Lm ICE83, none of these six ICE overlapped with the phages we detected in our dataset. Hence, we did not pursue further analyses of ICE.

Genetic maps

Using the genomes of the high-quality global dataset, we generated GenBank files for each MGE of interest. For this, we used Prokka v.1.1.14.663 for plasmids and transposons, and Pharokka v1.7.584 for phage and PP elements. Figures were generated with clinker v.0.025 with the option -gf to supply a file linking gene names and functions85. Functions were determined by Pharokka.

Statistical analyses

We used two-sided Fisher’s exact tests to compare the percentage of annotated AMR CDS, stress tolerance CDS, and other CDS in MGE versus in non-MGE. For the first test (Fig. 4A), our null hypothesis is that the proportion of CDS of interest (AMR or stress tolerance) carried by non-MGE versus MGE (sum of all MGE vehicles) follows the same distribution as the CDS of the other genes. In the second test (Fig. 4C), our null hypothesis is that the proportion of genes of interest (AMR or stress tolerance) annotated in 1, 2, 3, or 4 different DNA vehicles, depending on the genome assemblies, follows the same distribution as the other genes. In both tests, we did not include CDS located in PP elements because of the uncertainty of identification. We used a p-value threshold ≤ 0.05 to consider the significance of results.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article and its supplementary files. BioSample and the SRA accession numbers corresponding to the Illumina raw reads we used to carry out our re-assembly of the New York State genomes are listed in Supplementary Data 1. To note, genome assemblies originally linked to these SRA in NCBI are not the ones used in the present study; instead, the accession numbers for the 936 short-read sequences we re-assembled in this study can be found in Supplementary Data 1. These re-assembled genomes are annotated by NCBI as Third Party Annotation (TPA) sequences and are publicly available as BioProject PRJNA1280019 in NCBI. The same 936 short-read sequenced assemblies are also publicly available in the Institut Pasteur database (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/), and their IDs can also be found in Supplementary Data 1. The long reads generated in the present study, together with their corresponding 37 hybrid-assembled genomes, are available in NCBI under BioProject PRJNA1234602; the SRA and genome assemblies accession numbers for each isolate are listed in Supplementary Data 5. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The pipeline we used for viral annotation and filtering can be found at: https://github.com/HeloiseMuller/phageAnnotation, with the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17049361. All other scripts used in this study can be found at https://github.com/HeloiseMuller/ListeriaEx_scripts, with the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17069219.

References

Schlech, W. F. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 7, (2019).

Vázquez-Boland, J. A. et al. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 584–640 (2001).

Jordan, K. & McAuliffe, O. Listeria monocytogenes in Foods. in Advances in Food and Nutrition Research (ed. Rodríguez-Lázaro, D.) vol. 86 181–213 (Academic Press, 2018).

Luque-Sastre, L. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Listeria species. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, (2018).

Osek, J., Lachtara, B. & Wieczorek, K. Listeria monocytogenes - how this pathogen survives in food-production environments?. Front. Microbiol. 13, 866462 (2022).

Troxler, R., von Graevenitz, A., Funke, G., Wiedemann, B. & Stock, I. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Listeria species: L. grayi, L. innocua, L. ivanovii, L. monocytogenes, L. seeligeri and L. welshimeri strains. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6, 525–535 (2000).

Scortti, M. et al. Epistatic control of intrinsic resistance by virulence genes in Listeria. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007525 (2018).

Rippa, A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated in food and food-processing environments in Italy. Antibiotics 13, 525 (2024).

Kuenne, C. et al. Reassessment of the Listeria monocytogenespan-genome reveals dynamic integration hotspots and mobile genetic elements as major components of the accessory genome. BMC Genomics 14, 47 (2013).

Yang, H., Hoffmann, M., Allard, M. W., Brown, E. W. & Chen, Y. Microevolution and Gain or Loss of Mobile Genetic Elements of Outbreak-Related Listeria monocytogenes in Food Processing Environments Identified by Whole Genome Sequencing Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 11, (2020).

Castro, H., Douillard, F. P., Korkeala, H. & Lindström, M. Mobile elements harboring heavy metal and bacitracin resistance genes are common among Listeria monocytogenes strains persisting on dairy farms. mSphere 6, e0038321 (2021).

Weisberg, A. J. & Chang, J. H. Mobile genetic element flexibility as an underlying principle to bacterial evolution. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 77, 603–624 (2023).

Daubin, V. & Szöllősi, G. J. Horizontal gene transfer and the history of life. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 8, a018036 (2016).

Arnold, B. J., Huang, I.-T. & Hanage, W. P. Horizontal gene transfer and adaptive evolution in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 20, 206–218 (2022).

Gogarten, J. P. & Townsend, J. P. Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 679–687 (2005).

Richardson, E. J. et al. Gene exchange drives the ecological success of a multi-host bacterial pathogen. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1468–1478 (2018).

Evans, D. R. et al. Systematic detection of horizontal gene transfer across genera among multidrug-resistant bacteria in a single hospital. Elife 9, e53886 (2020).

Pang, T. Y. & Lercher, M. J. Each of 3,323 metabolic innovations in the evolution of E. coli arose through the horizontal transfer of a single DNA segment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 187–192 (2019).

Goyal, A. Horizontal gene transfer drives the evolution of dependencies in bacteria. iScience 25, 104312 (2022).

de Man, T. J. B. et al. Multispecies outbreak of Verona integron-encoded metallo-ß-lactamase-producing multidrug resistant bacteria driven by a promiscuous incompatibility group A/C2 plasmid. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, 414–420 (2021).

Raabe, N. J. et al. Real-time genomic epidemiologic investigation of a multispecies plasmid-associated hospital outbreak of NDM-5-producing Enterobacterales infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 142, 106971 (2024).

Frost, L. S., Leplae, R., Summers, A. O. & Toussaint, A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 722–732 (2005).

Halary, S., Leigh, J. W., Cheaib, B., Lopez, P. & Bapteste, E. Network analyses structure genetic diversity in independent genetic worlds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 127–132 (2010).

Osborn, A. M. & Böltner, D. When phage, plasmids, and transposons collide: genomic islands, and conjugative- and mobilizable-transposons as a mosaic continuum. Plasmid 48, 202–212 (2002).

Lai, S., Wang, H., Bork, P., Chen, W.-H. & Zhao, X.-M. Long-read sequencing reveals extensive gut phageome structural variations driven by genetic exchange with bacterial hosts. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn3316 (2024).

Pfeifer, E. & Rocha, E. P. C. Phage-plasmids promote recombination and emergence of phages and plasmids. Nat. Commun. 15, 1545 (2024).

Botelho, J., Cazares, A. & Schulenburg, H. The ESKAPE mobilome contributes to the spread of antimicrobial resistance and CRISPR-mediated conflict between mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res 51, 236–252 (2023).

Andam, C. P. & Gogarten, J. P. Biased gene transfer in microbial evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 543–555 (2011).

Burch, C. L., Romanchuk, A., Kelly, M., Wu, Y. & Jones, C. D. Empirical evidence that complexity limits horizontal gene transfer. Genome Biol. Evol. 15, evad089 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Core genome multilocus sequence typing for identification of globally distributed clonal groups and differentiation of outbreak strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ. Microbiol 82, 6258–6272 (2016).

Moura, A. et al. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16185 (2016).

Painset, A. et al. LiSEQ - whole-genome sequencing of a cross-sectional survey of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods and human clinical cases in Europe. Micro Genom. 5, e000257 (2019).

Jeffers, G. T. et al. Comparative genetic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from human and animal listeriosis cases. Microbiology 147, 1095–1104 (2001).

Whitman, K. J. et al. Genomic-based identification of environmental and clinical Listeria monocytogenes strains associated with an abortion outbreak in beef heifers. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 70 (2020).

Maury, M. M. et al. Uncovering Listeria monocytogenes hypervirulence by harnessing its biodiversity. Nat. Genet. 48, 308–313 (2016).

Disson, O., Moura, A. & Lecuit, M. Making sense of the biodiversity and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Trends Microbiol. 29, 811–822 (2021).

Schmitz-Esser, S., Anast, J. M. & Cortes, B. W. A large-scale sequencing-based survey of plasmids in Listeria monocytogenes reveals global dissemination of plasmids. Front. Microbiol. 12, 653155 (2021).

Robertson, J. & Nash, J. H. E. MOB-suite: software tools for clustering, reconstruction and typing of plasmids from draft assemblies. Micro Genom. 4, e000206 (2018).

Chmielowska, C. et al. Plasmidome of Listeria spp.—The repA-Family Business. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 10320 (2021).

Hua, X. et al. BacAnt: a combination annotation server for bacterial DNA sequences to identify antibiotic resistance genes, integrons, and transposable elements. Front Microbiol. 12, 649969 (2021).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Lebrun, M., Audurier, A. & Cossart, P. Plasmid-borne cadmium resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes are present on Tn5422, a novel transposon closely related to Tn917. J. Bacteriol. 176, 3049–3061 (1994).

Mullapudi, S., Siletzky, R. M. & Kathariou, S. Diverse cadmium resistance determinants in Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the turkey processing plant environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 627–630 (2010).

Clauset, A., Newman, M. E. J. & Moore, C. Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 70, 066111 (2004).

Radicchi, F., Castellano, C., Cecconi, F., Loreto, V. & Parisi, D. Defining and identifying communities in networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2658–2663 (2004).

Salyers, A. A. & Shoemaker, N. B. Broad host range gene transfer: plasmids and conjugative transposons. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 15, 15–22 (1994).

Wang, M. et al. ICEberg 3.0: functional categorization and analysis of the integrative and conjugative elements in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D732–D737 (2024).

Lee, S., Ward, T. J., Jima, D. D., Parsons, C. & Kathariou, S. The Arsenic Resistance-Associated Listeria Genomic Island LGI2 Exhibits Sequence and Integration Site Diversity and a Propensity for Three Listeria monocytogenes Clones with Enhanced Virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 83, e01189–17 (2017).

Parsons, C., Lee, S., Jayeola, V. & Kathariou, S. Novel Cadmium Resistance Determinant in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e02580–16 (2017).

Parsons, C., Lee, S. & Kathariou, S. Dissemination and conservation of cadmium and arsenic resistance determinants in Listeria and other Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 113, 560–569 (2020).

Pfeifer, E., Bonnin, R. A. & Rocha, E. P. C. Phage-plasmids spread antibiotic resistance genes through infection and lysogenic conversion. mBio 13, e0185122 (2022).

Utter, B. et al. Beyond the chromosome: the prevalence of unique extra-chromosomal bacteriophages with integrated virulence genes in pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 9, e100502 (2014).

Pfeifer, E., Moura de Sousa, J. A., Touchon, M. & Rocha, E. P. C. Bacteria have numerous distinctive groups of phage–plasmids with conserved phage and variable plasmid gene repertoires. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 2655–2673 (2021).

Zamudio, R. et al. Lineage-specific evolution and gene flow in Listeria monocytogenes are independent of bacteriophages. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 5058–5072 (2020).

Mazzamurro, F. et al. Intragenomic conflicts with plasmids and chromosomal mobile genetic elements drive the evolution of natural transformation within species. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002814 (2024).

Borezee, E., Msadek, T., Durant, L. & Berche, P. Identification in Listeria monocytogenes of MecA, a Homologue of the Bacillus subtilis Competence Regulatory Protein. J. Bacteriol. 182, 5931–5934 (2000).

Medrano Romero, V. & Morikawa, K. Listeria monocytogenes σH Contributes to Expression of Competence Genes and Intracellular Growth. J. Bacteriol. 198, 1207–1217 (2016).

Goh, Y.-X. et al. Evidence of horizontal gene transfer and environmental selection impacting antibiotic resistance evolution in soil-dwelling Listeria. Nat. Commun. 15, 10034 (2024).

Rabinovich, L., Sigal, N., Borovok, I., Nir-Paz, R. & Herskovits, A. A. Prophage Excision Activates Listeria Competence Genes that Promote Phagosomal Escape and Virulence. Cell 150, 792–802 (2012).

Didelot, X., Walker, A. S., Peto, T. E., Crook, D. W. & Wilson, D. J. Within-host evolution of bacterial pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 14, 150–162 (2016).

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075 (2013).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Tonkin-Hill, G. et al. Producing polished prokaryotic pangenomes with the Panaroo pipeline. Genome Biol. 21, 180 (2020).

Medini, D., Donati, C., Tettelin, H., Masignani, V. & Rappuoli, R. The microbial pan-genome. Curr. Opin. Genet Dev. 15, 589–594 (2005).

Feldgarden, M. et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog facilitate examination of the genomic links among antimicrobial resistance, stress response, and virulence. Sci. Rep. 11, 12728 (2021).

Jolley, K. A. & Maiden, M. C. J. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 595 (2010).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Page, A. J. et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Micro Genom. 2, e000056 (2016).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. & Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 518–522 (2018).

Tavaré, S. Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lect. Math. life Sci. 17, 57–86 (1986).

Lewis, P. O. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 50, 913–925 (2001).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing https://www.R-project.org/. (2021).

Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2019).

Tian, R., Zhou, J. & Imanian, B. PlasmidHunter: accurate and fast prediction of plasmid sequences using gene content profile and machine learning. Brief. Bioinforma. 25, bbae322 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. oriTDB: a database of the origin-of-transfer regions of bacterial mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D163–D168 (2025).

Guo, J. et al. VirSorter2: a multi-classifier, expert-guided approach to detect diverse DNA and RNA viruses. Microbiome 9, 37 (2021).

Hegarty, B. et al. Benchmarking informatics approaches for virus discovery: caution is needed when combining in silico identification methods. mSystems 9, e01105-23 (2024).

Nayfach, S. et al. CheckV assesses the quality and completeness of metagenome-assembled viral genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 578–585 (2021).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Bellanger, X., Payot, S., Leblond-Bourget, N. & Guédon, G. Conjugative and mobilizable genomic islands in bacteria: evolution and diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 720–760 (2014).

Bouras, G. et al. Pharokka: a fast scalable bacteriophage annotation tool. Bioinformatics 39, btac776 (2023).

Gilchrist, C. L. M. & Chooi, Y.-H. clinker & clustermap.js: automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics 37, 2473–2475 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Advanced Genomic Technologies Cluster at the Wadsworth Center, where library preparation and sequencing were carried out. We are grateful to the staff of the SUNY University at Albany Information Technology Services, where all bioinformatics analyses were carried out, and for their technical assistance. We also thank Bridget Hegarty for her guidance on phage annotation and benchmarking methods. C.P.A. thanks Priscilla Mae and Reginald Farnsworth for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by New York State, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Grant (Cooperative Agreement number NU50CK000423), and the Food and Drug Administration’s LFFM Grant (Cooperative Agreement number 1U19FD007089) to K.A.M. and Wadsworth Center. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health Award number R35GM142924 to C.P.A. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript, and the findings do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the authors’ institutions and funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. and C.P.A. designed and guided the work. K.A.M., L.M., and W.J.W. oversaw bacterial sampling, surveillance, and deposition of short-read sequence data in the NCBI database. S.E.W. carried out subculturing, DNA extraction, and curation of short-read sequence data and metadata during Lm surveillance. H.M., M.M.G., K.R.P., M.M., and S.L.B. prepared the bacterial cultures for ONT sequencing. H.M. and O.O.I. carried out all bioinformatics analyses. H.M. and C.P.A. wrote the initial and revised version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Landry Tsoumtsa-Meda and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muller, H., Ikhimiukor, O.O., Montoya-Giraldo, M. et al. Genetic exchange networks bridge mobile DNA vehicles in the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Commun 16, 9723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64743-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64743-x