Abstract

The heterodimeric GABAB receptor, composed of GB1 and GB2 subunits, is a metabotropic G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) activated by the neurotransmitter GABA. GABA binds to the extracellular domain of GB1 to activate G proteins through GB2. Here we show that GABAB receptors can be activated by mechanical forces, such as traction force and shear stress, in a GABA-independent manner. This GABA-independent mechano-activation of GABAB receptor is mediated by a direct interaction between integrins and the extracellular domain of GB1, indicating that GABAB receptor and integrin form a mechano-transduction complex. Mechanistically, shear stress promotes the binding of integrin to GB1 and induces an allosteric re-arrangement of GABAB receptor transmembrane domains towards an active conformation, culminating in receptor activation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that shear stress-induced GABAB receptor activation plays a crucial role in astrocyte remodeling. These findings reveal a role of GABAB receptor in mechano-transduction, uncovering a ligand-independent activation mechanism for GPCRs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. The GABAB receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that binds to GABA1,2. As a metabotropic receptor, GABAB receptor plays a crucial role in regulating brain functions and is implicated in various physiological processes, such as locomotion, learning and memory, and cognition3,4,5,6,7. It facilitates slow and long-term synaptic inhibition by inhibiting voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and preventing neurotransmitter release at presynaptic sites8. Additionally, it activates G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels and induces slow inhibitory potentials at postsynaptic sites in neurons8. GABAB receptor also has the ability to trigger Ca2+ release9,10and regulate astrocyte morphogenesis10,11. Dysregulation of GABAB receptor activity has been implicated in various diseases, such as epilepsy12,13, anxiety14, depression15,16, spasticity17, addiction18, pain19, Rett-like Phenotype20, epileptic encephalopathy21, and fragile X syndrome22. Therefore, the GABAB receptor represents an excellent therapeutic target. Baclofen (Lioresal) is a specific agonist of the GABAB receptor and is used to treat spasticity in multiple sclerosis and alcohol abuse disorder23,24,25. Notably, the GABAB receptor is present not only in the central nervous system but also in peripheral regions such as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, where it is involved in regulating intestinal motility, gastric emptying, and esophageal sphincter relaxation26,27,28. This raises the possibility that mechanical forces may regulate GABAB receptor activity. However, whether mechanical forces can regulate GABAB receptor activity has not been explored.

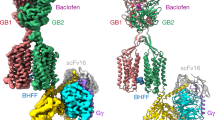

GABAB receptor is a class C GPCR that forms an obligatory heterodimer consisting of two subunits, GB1 and GB2. Each subunit comprises a large extracellular Venus flytrap domain (VFT) followed by canonical seven-transmembrane domains (7TMs)29,30,31. The VFT domain consists of two lobes: LB1 and LB230. In the inactive state, GABAB receptor interacts through the LB1 of two subunits and the intracellular tips of transmembrane domain 3 and 5 (TM3 and TM5)32. Agonists (GABA, baclofen) and antagonists (CGP54626) bind to a large crevice between LB1 and LB2 in the VFT domains of GB1 (VFTGB1). While the agonists stabilize the closure of VFTGB1, the antagonists prevent the closure of VFTGB1 (Fig. 1a). Agonist binding brings LB1 of VFTGB1 (LB1GB1) closer to LB2 of VFTGB1 (LB2GB1) to stabilize VFTGB1 closure, further bringing LB2GB1 and LB2 of GB2 (LB2GB2) in contact30,33,34,35. The interplay between LB2GB1 and LB2GB2, which is essential for receptor activation, triggers a rearrangement from the inactive 7TM interface formed by intracellular tips of TM3 and TM5 of GB1 and GB2 to the active interface formed by TM6 of GB1 and TM6 of GB2, leading to the coupling of Gi/o proteins to GB2 in a shallow pocket formed by TM3 and three intracellular loops30,33,34,35,36 (Fig. 1a). Additionally, positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) of GABAB receptor, such as Rac BHFF, GS39783 and CGP7930, bind within the TM6-TM6 interface to stabilize the active conformation of the receptor30,33,34,37. This mode of GABAB receptor activation has been extensively characterized and validated using multiple approaches. However, it is unclear whether additional mechanisms are in place to activate GABAB receptor.

a Schematic illustration depicting the modulation of GABAB receptor activity by ligands (e.g. agonists: GABA and baclofen; antagonist: CGP54626). b Schematic representation of the experiments applying traction force and shear stress to cells in this study, encompassing conditions such as cell suspension or adhesion; PDL or FN coating; and shear stress treatment. No GABA was added in these experiments. c IP1 production in HEK293 cells transfected with vector or GABAB receptor, along with Gqi9 chimera in the corresponding conditions: suspension or adhesion (left); PDL or FN coating (middle), without (control) or with shear stress (15 dyn/cm2, 15 min) (right). Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from at least three biologically independent experiments (from left to right, n=4, 5, 5, respectively), each performed in triplicate and analyzed using an unpaired t-test (two-tailed) to determine significance. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, not significant (ns) > 0.05. d Real-time recording of intracellular Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells expressing GABAB receptor and Gqi9. Left: Schematic presentation of shear stress loading device and real-time recording of Ca2+ response in single cells. Right: Real-time Ca2+ signal measurement. After the recording of basal state of Ca2+ release for 50 seconds, cells were subjected to shear stress for 100 seconds. Shear stress was then halted for 150 seconds, after which baclofen was injected and the Ca2+ signal was measured for another 200 seconds. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from 85 cells recorded. e Traction force and GABA-induced Gi protein activation in HEK293 cells measured by optimized Gi protein BRET sensors. Schematic presentation of Gi protein activation measurement by BRET assay based on Gαi1-Nluc, Venus-Gγ2 and endogenous Gβ rearrangement (left). Traction force- (middle) and GABA- (right) induced Gi protein activation in HEK293 cells transfected with vector or GABAB receptor together with Gi protein sensor. Cells were treated under suspension or adhesion conditions. The traction force-induced net BRET (middle) was calculated by the BRET ratio obtained under suspension conditions, subtracting the BRET ratio in adhesion conditions. PBS or GABA-induced net BRET (right) was calculated by the BRET ratio before PBS or GABA treatment, subtracting the BRET ratio after PBS or GABA treatment. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from five biologically independent experiments, and analyzed using an unpaired t-test (two-tailed) to determine significance. ****P < 0.0001, **P < 0.01.

Here, we report a ligand-independent activation mechanism of the GABAB receptor. We found that the GABAB receptor can be activated by mechanical forces (e.g., traction force and shear stress) independent of GABA. We demonstrated that GABAB receptors and integrins form a mechano-transduction complex and that shear stress-induced GABAB receptor activation plays a crucial role in astrocyte remodeling. Thus, our findings reveal a role of the GABAB receptor in mechano-transduction, uncovering a ligand-independent activation mechanism for GPCRs.

Results

GABAB receptor is activated by mechanical forces

GABAB receptor can be activated in a ligand-dependent manner by agonists, such as GABA and baclofen (Fig. 1a). However, whether a ligand-independent stimulus, such as mechanical force, can activate GABAB receptor remains unknown. To test this possibility, we explored whether different forces, such as traction force and shear stress, play a role in GABAB receptor activation (Fig. 1b). Both traction force and shear stress are common mechanical forces experienced by cells38,39,40. We first examined the traction force. When growing on the surface of a substrate such as a culture dish coated with poly-D-lysine (PDL), cells usually adhere to the surface of the dish, and traction force develops between the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix (ECM)41. However, no such traction force was observed in cells growing in suspension42. In addition, coating the culture dish with specialized ECM proteins, such as fibronectin (FN), which binds to the cell surface protein integrin, enhances traction force and promotes cell adhesion43,44,45. Myosin II activity is commonly used as a reliable readout of traction force in the cell46,47. We found that in cultured HEK293 cells, myosin II activity was nearly undetectable in suspension cells; in contrast, myosin II activity was clearly observed in adherent cells growing on PDL-coated dishes (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Treatment with FN further increased myosin II activity in adherent HEK293 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1b). These results are consistent with the notion that traction force develops in adherent cells and further increases when cells were attached to ECM proteins48.

We then examined the activity of the GABAB receptor in both adherent and suspended HEK293 cells expressing the GABAB receptor and a chimeric Gqi9, in which the Gi/o-coupled GABAB receptor can couple to the PLC pathway37. We thereby measured the production of the downstream metabolite inositol monophosphate (IP1), using a commonly used assay that reports GPCR activity49. Interestingly, when cells expressing GABAB receptor were attached on dishes coated with PDL, the IP1 production was significantly increased compared with that in suspension condition (Fig. 1c, left panel). The activity of GABAB receptor was further increased in adherent cells growing on FN-coated dishes compared with PDL-coated dishes (Fig. 1c, middle panel). Disruption of traction force by blebbistatin, which inhibits myosin II cross-bridge cycling50, blocked GABAB receptor activity in adherent cells (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These results reveal a correlation between the GABAB receptor activity and traction force, suggesting that mechanical forces can activate GABAB receptor. Because FN coating reflects a more physiological condition, we decided to focus on characterizing cells growing under this condition. Next, we evaluated the effect of shear stress on the GABAB receptor. Shear stress increased IP1 production in adherent HEK293 cells expressing the GABAB receptor and Gqi9 but not in control cells expressing only Gqi9 (Fig. 1c, right panel). This experiment suggests that shear stress can also activate the GABAB receptor.

While IP1 production serves as a reliable readout for GABAB receptor activation, it only reports the accumulative rather than the dynamic activity of GABAB receptor. To provide further evidence, we performed calcium imaging experiments to monitor the dynamic activity of GABAB receptors in response to shear stress in real-time. We found that shear stress could also induce GABAB receptor activity in cells expressing GABAB receptor and Gqi9 shown by the calcium imaging assay (Fig. 1d). A transient increase of Ca2+ release was observed after shear stress application, which quickly peaked and then gradually decreased to basal levels (Fig. 1d). The kinetics of shear stress-induced Ca2+ were slower, and the strength of shear stress-induced Ca2+ was lower than that of baclofen (Supplementary Fig. 1d). No such activity was observed in the control cells expressing only Gqi9 (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Thus, both assays reveal that shear stress can activate GABAB receptor. Taken together, these results demonstrated that GABAB receptor can be activated by mechanical forces. No GABA or any other GABAB receptor agonist was present in our assays and the concentration of GABA in the medium or the buffer was very low (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that the observed mechano-activation of the GABAB receptor is ligand-independent.

Finally, to determine whether traction force directly activates GABAB receptor-mediated Gi/o protein signaling, we employed an optimized bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based Gi protein sensor under physiological conditions, as recently described51. In this assay, we transfected only Gαi1-Nluc and Venus-Gγ2, omitting exogenous Gβ subunits. Since functional G protein signaling requires the formation of a Gαβγ heterotrimer, this design ensures that Gi activation depends exclusively on endogenous Gβ subunits. Consequently, BRET signal generation is constrained by the availability of endogenous Gβ to complex with Venus-Gγ2 (Fig. 1e, left panel). As a positive control, GABA increased the net BRET in cells expressing GABAB receptor and Gi protein sensor in both suspension and adhesion conditions, demonstrating sensor sensitivity (Fig. 1e, right panel). Traction force-induced net BRET was calculated by subtracting the BRET ratio in adhesion conditions from that in suspension. Cells expressing GABAB receptor exhibited a significant increase in traction force-induced net BRET compared to vector-expressing controls (Fig. 1e, middle panel), indicating that mechanical force activates Gi signaling downstream of GABAB receptor.

Mechano-activation of GABAB receptor occurs through a physical interaction with integrin

How is GABAB receptor activated by mechanical forces? The observation that the GABAB receptor can be activated in adherent cells but not in suspension cells indicates that the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor is cell condition-specific, suggesting the participation of additional proteins. As the ECM protein FN greatly enhanced the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor (Fig. 1c) and FN acts by directly binding to the cell surface protein integrin52, we hypothesized that integrin may be involved in the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor. The fact that integrin is a mechano-sensor, which connects both ECM proteins and the cytoskeleton and is sensitive to traction force and shear stress53,54, further supports this model. To test this model, we turned our attention to integrin β3, which is the primary receptor for FN55,56. As a receptor of FN, integrin β3 can function as a heterodimer with integrin αv57. Knockdown of integrin β3 by siRNA abolished traction force-induced GABAB receptor activation (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 3a). These results suggest that integrin β3 plays an important role in the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor.

a IP1 production in HEK293 cells transfected with either control siRNA or integrin β3 siRNA, along with the expressing of vector and Gqi9, or GABAB receptor and Gqi9, under either adhesion or suspension conditions. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from five biologically independent experiments and analyzed using unpaired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. ***P < 0.001, not significant (ns) > 0.05. b Co-immunoprecipitation of GABAB receptor and integrin β3 in HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor constructs (Snap-tagged GB1 and GB2) using anti-integrin β3 antibody, under basal condition. Only GB1 in cell surface was labeled and visualized using an impermeable Snap fluorescent substrate. c–f Co-immunoprecipitation of GABAB receptor and integrin β3 in HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor constructs (HA-tagged GB1 and GB2) using anti-HA antibody, under conditions including suspension or adhesion (c), without (control) or with shear stress (c), Blebbistatin (50 μM, 30 min) treatment (d), RGDS (10 μM, 12 h) treatment (e), or CGP54626 (50 μM, 30 min) treatment (f). Blots are representative from at least three biologically independent experiments (b, n = 4; c, suspension or adhesion, n = 3; control or with shear stress, n = 4; d, n = 3; e, n = 3; f, n = 4). The amount of integrin β3 immunoprecipitated by IgG or HA antibody are present as mean ± s.e.m. in (e) and analyzed using unpaired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. **P < 0.01. g Schematic representation of the BRET assay detecting direct interaction between GABAB receptor and integrin β3. Rluc was fused in C-terminal of GB1 or GB2 subunit (GB1Rluc or GB2Rluc) as luminescence donor. Venus was fused in C-terminal of integrin β3 or integrin αV subunit (integrin β3Venus or integrin αVVenus) as fluorescence acceptor. h, i Interaction of GABAB receptor and integrin β3 interaction between GB1 and integrin β3 or GB1 and integrin αV (h), or GB2 and integrin β3 (i) detected using BRET titration assay. The BRET between mGlu2 with Rluc fused in the C-terminal and 5HT2a receptor with Venus fused in the C-terminal was measured as positive control. The BRET between GB1Rluc and Venus was measured as negative control. Data were analyzed by nonlinear regression on a pooled data set from at least three biologically independent experiments (upper to lower, h, left, n = 16, 10, 12; right, n = 5, 5; i, n = 9, 9) each performed in triplicates, fitting with 1-site binding model in GraphPad Prism 8.

To investigate how integrin β3 mediates the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor, we asked whether GABAB receptor physically interacts with integrin β3. Indeed, when expressed in HEK293 cells, GABAB receptor co-immunoprecipitated (co-IP) with endogenous integrin β3. This was performed using two different approaches to tag (HA tag and Snap tag) the GB1 subunit of GABAB receptor (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 3b–d). We also detected integrin αv in the complex (Supplementary Fig. 3e), which is consistent with the notion that integrin β3 functions as a heterodimer with integrin αv52,58. Thus, GABAB receptor and integrin αvβ3 appear to form a protein complex. In support of this, we found that GABAB receptor and integrin β3 also co-localized in HEK293 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3f). These results together demonstrate GABAB receptor physically interacts with integrin αvβ3 to form a protein complex.

Interestingly, the interaction between integrin β3 and GABAB receptor appeared to be much stronger in adherent cells (Fig. 2c). Disruption of traction force using blebbistatin greatly diminished the interaction between integrin β3 and GABAB receptor (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 3g). Conversely, applying shear stress to HEK293 cells further enhanced integrin β3 and GABAB receptor interaction in these cells (Fig. 2c). These findings indicate that mechanical forces promote the formation of a GABAB receptor-integrin αvβ3 complex by facilitating the interaction between the two proteins.

To provide further evidence that integrin αvβ3 and GABAB receptor physically interact with each other, we tested the inhibitor and the antagonist. The integrin β3 inhibitor RGDS and the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP54626 both inhibited the interaction between integrin β3 and GABAB receptor (Fig. 2e, f, Supplementary Fig. 3g). This suggests that the interaction between integrin β3 and GABAB receptor is rather specific. Furthermore, the formation of GABAB receptor and integrin αv β3 complex increased with GABA treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3h). Overall, our observation suggests that the formation of GABAB receptor-integrin αvβ3 complex may depend on their active conformation.

We then investigated whether the interaction between GABAB receptor and integrin αvβ3 is direct. To test this, we performed a BRET titration experiment59,60. The energy donor Rellina luciferase (Rluc) and the energy acceptor Venus were attached to the C-terminus of GB1 or GB2 subunit of GABAB receptor, integrin β1, integrin β3, and integrin αv (named as GB1Rluc, GB2Rluc, integrin β1Venus, integrin β3Venus, and integrin αvVenus), respectively (Fig. 2g). Within a distance of 10 Å, energy transfer occurs between Rluc and Venus, which would indicate a direct interaction between the two proteins. In this assay, by examining the BRET ratio as a function of the relative amounts of the two tested proteins, one would not only be able to evaluate if a direct interaction occurs between the two proteins, but also can assess the relative strength of the interaction. We first performed control experiments. While no BRET signals were detected between Venus and GABAB receptor (negative control), strong BRET signals were observed between mGlu2 and 5-HT2a that are known to directly interact (positive control)61, validating the assay. Importantly, we observed strong BRET signals between GABAB receptor and integrin β3 (Fig. 2h). These BRET signals were much more robust than those between mGlu2 and 5-HT2a, suggesting that the interaction between GABAB receptor and integrin β3 is stronger than that between mGlu2 and 5-HT2a, which has been demonstrated to form oligomer61. By contrast, weak, if any, BRET signals were detected between integrin αv and GABAB receptor (Fig. 2h). Thus, although integrin αv was present in the integrin αvβ3-GABAB receptor complex (Supplementary Fig. 3e), it did not appear to directly interact with GABAB receptor, further supporting the model that integrin β3 rather than αv directly interacts with GABAB receptor. Notably, the BRET signals between GB1 and integrin β3 were much more robust than those between GB2 and integrin β3, suggesting that GABAB receptor interacts with integrin β3 primarily via its GB1 subunit (Fig. 2i). These results demonstrate that the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor requires integrin αvβ3, which is primarily mediated by a direct interaction between integrin β3 and the GB1 subunit of GABAB receptor. Taken together, our data suggest that GABAB receptor responds to mechanical forces through a mechano-transduction complex formed with integrin αvβ3 and that mechanical forces can promote the formation of this protein complex. FN can also bind to integrin αvβ162. BRET signals were also observed between integrin β1 and GABAB receptor (Supplementary Fig. 4a), suggesting the formation of mechano-transduction GABAB receptor complex with FN-related integrin proteins. Interestingly, other ECM proteins, such as collagen I, also increased GABAB receptor activation (Supplementary Fig.4b), suggesting the involvement of other integrin subtypes.

Both GB1 and GB2 are required for GABAB receptor activation by mechanical forces

As GABAB receptor interacted with integrin β3 primarily through its GB1 subunit, we wondered if GB1 alone can interact with integrin β3. As GB1 alone cannot localize to the plasma membrane, we tested GB1ASA, a GB1 subunit mutant which can localize to the cell surface on its alone63, and found that it cannot be activated by traction force (Fig. 3a). A similar phenomenon was observed with GB2 alone (Fig. 3a). Thus, both GB1 and GB2 subunits are required for the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor. As GB2 is responsible for coupling G proteins to GABAB receptor upon agonist binding, we tested GB2L685P, a mutant form of GB2 that is incapable of activating G proteins64. The traction force failed to induce GABAB receptor activation in HEK293 cells expressing GB1 and GB2L685P (referred to as GABAB-ΔG) together with Gqi9 (Fig. 3b). Thus, similar to ligand-dependent activation of GABAB receptor, mechanical activation of this receptor also requires coupling of G proteins to the receptor via the GB2 subunit. These results indicate that while GABAB receptor interacts with integrin β3 primarily via the GB1 subunit, the GB2 subunit is also necessary for GABAB receptor activation by mechanical forces and this ligand-independent activation mode required G protein coupling to GB2. Thus, both GB1 and GB2 subunits participate in the formation of the mechano-transduction complex with integrin αvβ3.

a–c Left: IP1 production in HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated constructs, along with Gqi9 under either suspension or adhesion conditions: (a): vector, GABAB receptor (GB1 and GB2), GB1 only or GB2 only; (b): vector, GABAB receptor, GABAB-ΔG (mutant with L685 in GB2 substituted with Phenylalanine that fails to couple G protein), or GABAB-ΔB (mutant with the residues S276 and E465 in GB1 mutated to Analine that fails to bind GABA); (c): vector or GABAB receptor, treated with or without antagonist CGP54626 (50 μM, 30 min). Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from at least three biologically independent experiments (from left to right, a, n = 4, 4, 4, 4; b, n = 6, 6, 4, 4; c, n = 5, 3, 6, 4) each performed in triplicates, and analyzed using unpaired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, not significant (ns) > 0.05. Right: Model of the traction force-induced GABAB receptor activation through the closure of GB1VFT-induced LB2GB1 and LB2GB2 in contact. The traction force-activated GABAB receptor requires both GB1 and GB2, and relies on GB2 for G protein coupling. Whereas the traction force-activated GABAB receptor is independent of GABA binding, preventing VFTGB1 closure by GABAB receptor antagonist CGP54626, abolishes traction force-induced GABAB receptor activation, indicating that the closure of GB1VFT-induced LB2GB1 and LB2GB2 in contact is important for traction force-induced GABAB receptor activation.

Furthermore, to understand how mechano-activation occurs through the interaction between the GB1 and GB2 subunits, we generated a GB1 mutant by inserting two mutations (S246A and E465A) into GB1VFT (referred to as GABAB-ΔB) as previously reported65,66,67 to prevent GABA binding but not to prevent the closure of GB1VFT-brought GB1LB2 and GB2LB2 in contact (Fig. 3b). The GABAB-ΔB composed by this GB1 mutant and GB2 wild type can still be activated by traction force to the similar extend as GABAB receptor (Fig. 3b), demonstrating GABA-binding into GB1VFT was not required in mechano-activation of GABAB receptor and indicating that mechano-force alone also stabilize the closure of GB1VFT-brought LB2 of two subunits in contact. An antagonist (CGP54626) can prevent GB1VFT closure-induced two LB2 in contact33. CGP54626 completely blocked traction force-induced GABAB receptor activation, indicating that mechano-force induced GABAB receptor activation requires the closure of GB1VFT-brought two LB2 of two subunits in contact (Fig. 3c). This data is also consistent with the observation that CGP54626 inhibited the interaction between integrin β3 and GABAB receptor (Fig. 2f) whereas GABAB-ΔB still interacts with integrin β3 (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Overall, our results show that the traction force-activated GABAB receptor requires both GB1 and GB2 subunit, and is dependent on the closure of GB1VFT-induced LB2GB1 and LB2GB2 in contact, and GB2 subunit for G protein coupling, but independent of GABA binding, suggesting that mechano-force acts as a positive allosteric modulator agonist (PAM ago) of the GABAB receptor.

Mapping the region in GABAB receptor that interacts with integrin β3

We then sought to map the region in GB1 that interacts with integrin β3. First, we examined the role of VFT in the extracellular domain of GB1 (VFTGB1). Deleting VFT in GB1with a truncated GABAB receptor (GABAB-ΔVFT) lacking the VFT domain of GB1 (GB1-ΔVFT) (Fig. 4a), abolished the interaction between integrin β3 and GABAB receptor, revealing a key role of VFTGB1 in mediating the interaction (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 5a). Similarly, traction force and shear stress failed to induce GABAB-ΔVFT activation in HEK293 cells (Fig. 4c, d), indicating that the VFTGB1 is required for the mechano-activation of GABAB receptor. Both results suggest that the VFTGB1 may mediate the physical interaction between GB1 and integrin β3.

a Schematic representation of GABAB-ΔVFT truncation, in which GB1 subunit lacks of the VFT domain (GB1-ΔVFT), but retains the ability to be activated by positive allosteric modulator Rac BHFF (yellow square). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using anti-HA antibody targeting to the HA tag, which is fused in the N-terminal of GB1 or GB1-ΔVFT. b Co-immunoprecipitation of GABAB receptor or GABAB-ΔVFT and integrin β3 using anti-HA antibody. Blots are from one representative of five biologically independent experiments. c IP1 production in cells transfected with GABAB receptor, or GABAB-ΔVFT, along with Gqi9 under suspension or adhesion conditions. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from four biologically independent experiments each performed in triplicates and analyzed using unpaired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. *P < 0.05, not significant (ns) > 0.05. d Real-time recording of intracellular Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells expressing GABAB-ΔVFT and Gqi9. After recording the basal state of Ca2+ release for 50 seconds, cells were subjected to shear stress for 100 seconds. Shear stress was then halted for 150 seconds, after which Rac BHFF was added for 200 seconds. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from 135 cells recorded.

Next, we used a glycan wedge scanning approach to map the interaction interface between the VFTGB1 and integrin β3. A consensus sequence NXS/T was introduced into GB1VFT to enable the conjugation of a bulky N-glycan moiety to the side chain of the Asn residue, thereby forming a steric wedge to prevent GB1 from interacting with other proteins68. We selected seven GB1 mutants: 320STL322 (M1), 326EER328 (M2), 330KEA332 (M3), 337TFR339 (M4), 347AVP349 (M5), 352NLK354 (M6) and 356QDA358 (M7) (Fig. 5a–c). We have previously shown that the presence of an N-glycan moiety in these mutants do not affect agonist-induced GABAB receptor activation68. We found that although the traction force failed to activate M2, M4, M6 and M7, it was still able to activate M1, M3 and M5 (Fig. 5d). Moreover, the amount of integrin β3 co-IPed with GB1 was greatly reduced in M7 mutant, but not in M3 mutant (Supplementary Fig. 5b). This indicates that residues 326-328, 337-339, 351-353 and 356-358 in GB1VFT are important for its interaction with integrin β3. Interestingly, these sequences in GB1 are highly conserved across different species (human, mouse, C. elegant, D. melanogaster, R. norvegicus, B. taurus, C. sabaeus), especially the last 5 residues RQDAR (Supplementary Fig. 5c). We thus tested this RQDAR motif in GB1VFT, and found that the GABAB-5A mutant (GB1RQDAR-5A + GB2), in which RQDAR were mutated into five A (Ala) residues (Fig. 5b), exhibited a much weaker interaction with integrin β3 (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Importantly, this GABAB-5A mutant could still be activated by GABA (Fig. 5e), but lost sensitivity to traction force and shear stress (Fig. 5f–g). This set of experiments demonstrates that the GB1 subunit of GABAB receptor interacts with integrin β3 via its VFT domain and that the RQDAR motif in VFTGB1 is important for GABAB receptor’s interaction with integrin β3 as well as its activation by mechanical forces.

a 3D model of the VFT of GB1 and GB2. N-glycosylation mutations (M1-7) are highlighted in LB2 of GB1 VFT. b Detailed presentation of the mutants of M1-7 and 5 A. c Schematic representation of GABAB-M1-7 and GABAB-5A. d IP1 production in HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor WT, or GABAB receptor mutants M1-7 along with Gqi9 under suspension or adhesion conditions. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from at least three biologically independent experiments (from left to right: n = 6, 6, 6, 5, 6, 5, 5, 4, 5) each performed in triplicates and analyzed using paired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, not significant (ns) > 0.05. e Intracellular calcium release induced by different dose of GABA in HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor WT and Gqi9, or GABAB-5A and Gqi9. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. from three biologically independent experiments each performed in triplicates. f IP1 production in HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor WT and Gqi9, or GABAB-5A and Gqi9 under suspension or adhesion conditions. Data are mean ± s.e.m. from four biologically independent experiments each performed in triplicates and analyzed using unpaired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. *P < 0.05, not significant (ns) > 0.05. g Real-time recording of intracellular Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells expressing GABAB-5A and Gqi9. After recording the basal state of Ca2+ release for 50 seconds, cells were subjected to shear stress for 100 seconds. Shear stress was then halted for 150 seconds, after which baclofen was added and the Ca2+ signal was measured for another 200 seconds. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from 111 cells recorded.

Mechano-force acts as a positive allosteric modulator agonist (PAM ago) for GABAB receptor activation

Ligand-induced GABAB receptor activation features a close contact between LB2GB1 and LB2GB2, further triggers an allosteric rearrangement of 7TMs at the TM6-TM6 interface between GB1 and GB2 subunits (Fig. 6a), which is considered as a hallmark of the active state of GABAB receptor30,33,34,35,36. Upon ligand binding, the two Val residues in TM6 of GB16.56 and GB26.56 turn close to each other in the active state of the receptor36 (Fig. 6b). The close proximity of the two Val residues in this active state enables the formation of GB1-GB2 dimers through covalent cross-linking of the two subunits, in which the two Val residues are mutated to Cys residue: GB16.56C and GB26.56C 36. Thus, this assay allows the probing of the active state of GABAB receptor in HEK293 cells transfected only with GB16.56C and GB26.56C. Consistent with our previous reports, GABA treatment promoted the formation of GB16.56C-GB26.56C dimers36. Of primary significance, shear stress also promoted the formation of GB16.56C-GB26.56C dimers (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, FN-treatment also increases the formation of GB16.56C-GB26.56C dimers (Fig. 6d, e). In all, this set of experiments demonstrates that mechanical forces can facilitate an allosteric interaction between two VFTs to further induce re-arrangement of 7TMs of GABAB receptor towards an active conformation in a manner similar to that induced by ligand binding, demonstrating that the mechanical force acts as a PAM agonist for GABAB receptor activation.

a Schematic representation of the active state of GABAB receptor, while the TM6s of GB1 and GB2 are rearranged towards each other. b Highlight of the cysteine substitutions (red balls) in the position 6.56 of TM6 in GB1 and GB2 in its active state structure (PDB: 7EB2). c Cross-linking of cell surface GABAB receptor between the two cysteines in GB16.56 and GB26.56 with CuP treatment along with no shear stress (control), shear stress treatment (15 dyn/cm2, 30 min) or GABA treatment (100 μΜ, 30 min). d, e Cross-linking of cell surface GABAB receptor dimer between the two cysteines in GB16.56 and GB26.56 encompassing three conditions: without CuP treatment, with CuP treatment, with both CuP and GABA treatment, under PDL or FN-treated condition. MW, molecular weight. Blots in (c, d) are one representative experiment of five biologically independent experiments. The bars show the percentage of GB1-GB2 dimer, which are relative to total amount of GB1 including GB1-GB2 dimer and GB1 monomer in each lane. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from five biologically independent experiments respectively in (c, d) and analyzed using paired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. f, g Dose response curve and Emax analysis of GABA-induced IP1 production in HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor and Gqi9 under suspension or adhesion conditions (f), or under PDL or FN-treatment (g). Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from five and three biologically independent experiments each performed in triplicates in (f) and (g) respectively. Emax are analyzed using paired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. *p < 0.05.

We also observed that FN-treatment increases of GABA-induced formation of GB16.56C-GB26.56C dimers (Fig. 6d, e), suggesting the PAM effect of mechano-force on GABA-induced activation of GABAB receptor. We further verified whether and how mechanical forces allosterically regulate GABA-induced GABAB receptor activity. Interestingly, both the efficacy and potency of GABA-induced receptor activation was increased under adhesion and FN-treated conditions (suspension vs adhesion, Emax: 256 nM vs 552 nM, EC50: 0.18 μM vs 0.08 μM; PDL vs FN, Emax: 168 nM vs 257 nM, EC50: 0.19 μM vs 0.02 μM) (Fig. 6f-g), highlighting the potential PAM effect of mechano-force on GABA-induced GABAB receptor function in vivo.

Finally, we used a FRET-based inter-subunit sensor of the GABAB receptor to measure the conformational change between two VFTs of GABAB receptor, as previously reported by us69 (Supplementary Fig. 5e), while GABA treatment induced a significant decrease of FRET signal (Supplementary Fig. 5f). The present FRET-based assay is specifically configured for 96-well plate measurements and therefore cannot be implemented in shear stress experiments. To address this limitation while maintaining mechanosensitive responses, we utilized FN-coated substrates to enhance cellular traction forces. FN coating alone induced statistically significant FRET changes (Supplementary Fig. 5g), suggesting the traction force-induced GABAB receptor conformational change. However, the detailed mechanism requires further investigation.

GABAB receptor is required for shear stress-induced remodeling of astrocytes

Having characterized the mechanisms underlying GABAB receptor activation by mechanical forces, we investigated whether and how mechanical force may regulate cellular physiology. GABAB receptors are widely expressed in many types of neurons in the brain8. However, the relatively low abundance and high heterogeneity of neurons (compared to glial cells) pose a challenge for investigating this question in neurons. In addition to neurons, GABAB receptors are also broadly expressed in glial cells, particularly in astrocytes9,11, which are the most abundant neural cells in the brain70. In response to mechanical insults experienced during traumatic brain injury, astrocytes undergo morphological, molecular, and functional remodeling, which transforms them into reactive astrocytes in a process called reactive astrogliosis71. Reactive astrocytes play an important role in tissue repair and remodeling following brain trauma72,73,74. Other pathological conditions such as infection, ischemia, epilepsy, and cancer also trigger reactive astrogliosis73,75,76,77,78. The robust remodeling of astrocytes induced by mechanical insults, high abundance of these glial cells in the brain, and relative ease of culture prompted us to explore whether GABAB receptors contribute to mechano-induced reactive astrogliosis. To do so, we cultured primary astrocytes isolated from the mouse brain and assayed the effects of shear stress on their remodeling. We found that shear stress greatly increased the size of astrocytes and their expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Fig. 7a-c), two key parameters of astrocyte reactivity78,79, indicating that shear stress promoted reactive astrogliosis. Importantly, siRNA knockdown of the GABAB receptor abolished the shear stress-induced increase in the size of astrocytes as well as the expression level of GFAP, pointing to a key role of GABAB receptor in the process (Fig. 7a-d). Additionally, baclofen and GABA increased both cell size and GFAP expression of astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 6), which mimicked the effect of shear stress, demonstrating the physiological role of GABAB receptor activation in astrocyte remodeling. Notably, physiological GABA levels (10 nM)80,81 failed to increase cell size or GFAP expression or synergize with shear stress (Supplementary Fig. 6d-f). However, shear stress alone and 100 µM GABA produced similar effects, suggesting that maximal GABAB receptor activation and mechanical stimulation may converge on common downstream pathways. Together, these results demonstrate that shear stress-induced reactive astrogliosis requires GABAB receptors.

a Immunofluorescent staining of GFAP (red), GFP (green) and DAPI (cyan) in astrocytes transfected with control siRNA or GABAB receptor siRNA along with GFP, treatment with or without shear stress (15 dyn/cm2, 30 min). Images are representative from three biologically independent experiments. Scale bar: 10 μm. b, c Analysis of the cell size and GFAP expression of astrocytes with the same treatment in (a). Measurements are made on each cell by cell basis (ROI) from three biologically independent experiments (number of cells from left to right: n = 47, 37, 32, 40). Data are present as mean ± s.e.m and analyzed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to determine significance. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, ns: non-significant. d RNA interference efficacy of the GB1 in astrocytes in (b, c) using qPCR detecting gbb1 expression. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from three biologically independent experiments and analyzed with unpaired t test (two-tailed) to determine significance. ***P < 0.001.

Shear stress activates astrocytes in a GABAB receptor-dependent manner

The finding that GABAB receptors are required for shear stress to promote reactive astrogliosis suggests that shear stress may activate GABAB receptors in these primary cells just like when it was expressed in HEK293 cells. To test this hypothesis, astrocytes were recorded using calcium imaging to determine their response to shear stress. In astrocytes, Ca2+ is a major downstream event of GABAB receptor and dependent on Gi/o protein, as previously reported9,82,83,84,85. The pre-treatment of PTX totally blocked the baclofen-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Therefore, no transfection of G protein chimera was required to detect GABAB receptor-induced Ca2+ signal in astrocytes. The cells with Ca2+ activation was characterized as previously86 by an increasing in the Ca2+ signal to reach a peak after stimulus and sustain for more than 5 s. Owning to the heterogeneity of primary astrocytes, approximately 37.29% of astrocytes were sensitive to baclofen and were found to induce Ca2+ release, similar to a previous report9. About half (45.76%) of the astrocytes were sensitive to shear stress with a transient but significant increase of the Ca2+ signal (Fig. 8a). Among them, 62.04% were sensitive to baclofen, a GABAB receptor-specific agonist, indicating that most shear stress-sensitive astrocytes expressed GABAB receptors (Fig. 8a-b). Notably, siRNA knockdown of the GABAB receptor greatly reduced the population of astrocytes that were sensitive to baclofen (reduced to 6.69% from 37.29%) (Supplementary Fig. 7b–d) as well as shear stress (reduced to 13.49% from 45.76%) (Fig. 8c, d), indicating that GABAB receptors play a crucial role in mediating shear stress-induced response in these primary cells. The strength of the Ca2+ signal was significantly decreased for both shear stress and baclofen treatment when GABAB receptor was knocked down, whereas as a control, the population of astrocytes with ATP sensitivity remained 100% and the Ca2+ signal was still strongly activated (Supplementary Fig. 7e). Furthermore, PTX pre-treatment also decreased the population of shear stress-sensitive cells from 45.76% to 28.57% (Supplementary Fig. 7f), indicating the involvement of Gi/o protein for shear stress-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytes. Overall, we demonstrated that shear stress can activate astrocytes in a GABAB receptor-dependent manner. This suggests a model in which shear stress can activate GABAB receptors in astrocytes, triggering reactive astrogliosis.

a Real-time recording of intracellular Ca2+ release in astrocytes under shear stress. Cells were transfected with control siRNA and treated with shear stress, baclofen (100 μM) or ATP (100 μM) in the indicated time point. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from 15 cells recorded and are representative from six biologically independent experiments. b Percentage of astrocytes in response to shear stress or baclofen in 236 recorded cells. c Real-time recording of intracellular Ca2+ release in astrocytes under shear stress. Cells are transfected with siRNA knocking down the GABAB receptor and administered to shear stress, baclofen (100 μM), or ATP (100 μM) at the indicated time points. Data are present as mean ± s.e.m. from 45 cells recorded and are representative of six biologically independent experiments. d Percentage of astrocytes with the calcium response (sensitive) or without the calcium response (insensitive) to shear stress (control siRNA: 236 cells; GABAB siRNA: 314 cells). Data are analyzed with χ2 test (two-sided) to determine significance. ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

As a classic class C GPCR, the activation mechanism of GABAB receptor has been extensively characterized at both the biochemical and structural levels, which features a series of ligand binding-induced structural rearrangements in the receptor, culminating in its formation of a ternary complex with heterotrimeric Gi/o proteins30,87. In this study, we found that GABAB receptors were activated by mechanical forces in a GABA-independent manner. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a ligand-independent activation mechanism for GABAB receptor.

It is notable that the GABAB receptor forms a protein complex with integrin and that GABAB receptor sensing of mechanical forces requires a direct interaction with integrin. We thus propose that GABAB receptor and integrin form a mechano-transduction complex. In this complex, integrin likely functions as a mechano-sensor, as integrin is well-known to sense mechanical forces such as traction force and shear stress in cellular mechanotransduction53,88. On the other hand, as blocking integrin function or inhibiting its expression abolishes the mechano-activation of GABAB receptors, GABAB receptors may not directly sense mechanical forces but rather function as a transducer that transduces mechanical signals to downstream G proteins. Here we showed that GABAB receptor interacts with the integrin subunit β3 and β1. Other integrins may also be involved as FN and RGDS can bind to several integrin types57,62. A growing list of GPCRs have been reported to be mechanosensitive, such as AT1R89,90, H1R90,91, bradykinin B2R92, GPR6893, and adhesion GPCRs94,95,96. Unlike GABAB receptors, these mechanosensitive GPCRs are believed to directly sense mechanical forces as a mechano-sensor, though the underlying mechano-transduction mechanisms are not well understood. Thus, GABAB receptor represents the first GPCR that acts as a mechano-transducer rather than a mechano-sensor, revealing a role for GPCRs in mechano-transduction.

Strikingly, although mechanical forces activate GABAB receptor in the absence of ligand binding, they trigger an allosteric rearrangement of the 7TMs in GABAB receptor towards an active state in a manner similar to that induced by ligand binding. Specifically, both ligand binding and shear stress induced a similar allosteric rearrangement of 7TMs in the TM6-TM6 interface of the GB1 and GB2 subunits. This structural rearrangement has been shown to open a shallow cavity at the intracellular side of GABAB receptor to provide access for G protein binding30,33,34,35,36, which is a hallmark of the active state of GABAB receptor. Notably, agonists such as GABA and baclofen bind to a larger crevice between LB1 and LB2 of VFTGB1 to bring the two LB2 of two subunits in contact. As shear stress promotes the binding of integrin to LB2 of VFTGB1, it is conceivable that shear stress may activate the GABAB receptor by promoting integrin binding to LB2 of VFTGB1, which in turn pushes the two LB2 in contact and triggers an allosteric rearrangement of 7TMs in the TM6-TM6 interface towards an active conformation, culminating in receptor activation. In this regard, shear stress-induced binding of integrin to GB1 would mimic the role of ligand (e.g. GABA) binding to GB1 in GABAB receptor activation, providing a potential molecular mechanism by which mechanical forces activate GABAB receptor and allosterically potentiate the GABA effect as a PAM ago (Fig. 9). It is also different from the adhesion GPCRs, which act as mechano-sensors and rely on an extremely large N terminus for ECM recognition and an autoproteolysis domain that undergoes self-cleavage for receptor activation94,96. The GABAB activation showed faster under baclofen treatment than shear stress induced Ca2+ signal in our experiments, which was also observed in GPR6893. However, fundamental differences in stimulus application preclude strict kinetic comparisons: Baclofen can be applied locally at saturating concentrations for rapid, complete receptor activation, whereas higher shear stresses needed to accelerate mechano-activation would detach cells, compromising reliable signal detection.

Antagonist CGP54626-bound GABAB receptor fails to interact with integrin β3, whereas integrin β3 interacts with GB1VFT of GABAB receptor with constitutive activity. Mechanical force promotes GB1VFT and integrin β3 interaction to stabilize the closure of GB1VFT-induced LB2GB1 and LB2GB2 in contact, further inducing an allosteric re-arrangement of the GABAB receptor 7TM towards an TM6-TM6 active conformation, culminating in the asymmetric activation of the receptor with G protein under GB2. Mechanical force acts as a positive allosteric modulator to boost up GABA-induced GABAB receptor activation through interaction between GB1VFT and integrin β3.

We showed that shear stress could stimulate the activity of primary astrocytes in a GABAB receptor-dependent, but GABA-independent manner. We also found that shear stress promotes reactive astrogliosis, a process by which astrocytes undergo remodeling in response to pathological conditions, such as brain trauma, to transition into reactive astrocytes that are important for tissue repair72,73,74. Although the brain is typically considered as a protected organ, it may also experience transient shear stress, such as during traumatic brain injury, which can generate both localized and distributed forces throughout the brain72,73,97. Importantly, shear stress-induced reactive astrogliosis requires GABAB receptor. These results together suggest a model in which mechanical forces activate GABAB receptors in astrocytes to promote reactive astrogliosis. Although GABAB receptor appears to a major contributor to astrocyte mechano-sensitivity, siRNA knockdown of the GABAB receptor eliminated most but not all mechanosensitive astrocytes. This is consistent with the notion that additional mechano-sensors are present in these glial cells, such as mechanosensitive Piezo channels as reported recently98.

As the sole metabotropic GABA receptor, GABAB receptor regulates a wide spectrum of physiological processes, ranging from synaptic inhibition to locomotion7, cognition6, addiction18, epilepsy12,13, and astrocyte morphogenesis10,11. To date, all the physiological functions carried out by GABAB receptor have been attributed to its activation by GABA. Our discovery of a GABA-independent activation mechanism of the GABAB receptor and its crucial role in promoting astrocyte remodeling raises the possibility that this mode of activation may contribute to additional aspects of GABAB receptor functions in the brain. Our work also raises the possibility that other GPCRs could be potentially sensitive to mechanical forces by forming a mechano-transduction complex with integrin.

Methods

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal GB1 antibody targeting the extracellular domain (#55051, 1:1000) was acquired from Abcam (Shanghai, China), and GB1 polyclonal antibody (#BS2717, 1:1000) was obtained from Bioworld Technology (Shanghai, China). Integrin β3 antibody (#sc-46655, 1:100) and anti-mouse IgG (#sc-2025, 1:500) for the co-immunoprecipitation experiment were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Integrin αv antibody (#A2091, 1:1000) was purchased from ABclonal Technology (Wuhan, China). Integrin β3 antibody (#13166, 1:1000), β-actin (#4967, 1:1000), phospho-Myosin Light Chain 2 (MLC-PP, #3675, 1:1000), GFAP (#3670, 1:1000), anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody (#7076, 1:10000), anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked antibody (#7074, 1:10000), anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (DyLightTM 800 4X PEG Conjugate) (#5151, 1:10000) and anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (DyLightTM 800 4X PEG Conjugate) (#5257, 1:10000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Shanghai, China). Anti-HA antibody (#3F10, 1:100) was purchased from Roche (Shanghai, China). Cy3 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (A0521, 1:500) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China).

Reagents

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, #8120251), fetal bovine serum (FBS, #10437028), penicillin-streptomycin (#15140-122), Opti-MEM medium (#31985070), cell dissociation buffer (#2075828), Fluo4-AM (#F14202), lipofectamine 2000 (#11668019) and PierceTM enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (#37074) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China). Proteinase cocktail inhibitor (#04693159001) was bought from Roche (Shanghai, China). Protein G beads (#3394201) and nitrocellulose membranes (#HATF00010) were from Millipore (Shanghai, China). GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) (#43811), Dichloro (1, 10-phenanthroline) copper (II) (#362204), Poly-D-Lysine (#P1149), and Poly-L-ornithine hydromide (#P3655) were bought from Sigma (Shanghai, China). Blebbistatin (#B1387) was purchased from ApexBio Technology (Shanghai, China). Recombinant Human Fibronectin (#40113ES10) was from Yeasen (Shanghai, China). CGP54626 hydrochloride (#HY-101378) and RGDS peptide (Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser, #HY-12290) were from Med Chem Express (Shanghai, China). Baclofen (#0796) and Rac BHFF (#3313) were from Tocris Bioscience (Shanghai, China). Coelenterazine H (#S2011) was purchased from Promega (Beijing, China). Snap-Surface Alexa Fluor 647 (#S9136) was from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA, USA). PTX was purchased from GLPBIO (#70323-44-3, Shanghai, China).

Plasmids

The pRK5 plasmids encoding N-terminal HA-tagged wild-type rat GB1a, N-terminal Flag-tagged wild-type rat GB2, GB1ASA, GB1ΔVFT, HA-Snap-GB1, HA-Snap-GB16.56C, Flag-Halo-GB26.56C, Gi1-Nluc, Gβ1 and Venus-Gγ2 were generated in the lab36,37,51,68. The pRK5 plasmids encode the GB1ΔVFT, tagged with HA and Snap inserted after the signal peptide. The pRK5 plasmids encoding wild-type human integrin β3 (UniProt: P05106) was tagged with HA tag, inserted immediately after the signal peptide. The integrin αv plasmid (UniProt: P06756, #P40612) was purchased from the company (Miaolingbio, Wuhan, China). The probes (full-length mVenus, Rluc, YFP or RFP) were fused to the C terminus of the GB1, GB2, integrin β3, integrin β1, integrin αv, mGlu2 or 5-HT2a receptors. All the mutants for GABAB receptor were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange mutagenesis protocol (Agilent Technologies, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

HEK293 cell culture and transfection

HEK293 cells (ATCC, CRL-1573, lot: 3449904) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (heat-inactivated) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's protocol. Two million cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids with the lipofectamine/DNA ratio at 2:1, and the total DNA at 1.5 μg in 35 mm diameter dishes.

Primary astrocyte culture

All experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the College of Life Science and Technology at Huazhong University of Science and Technology and were specifically designed to minimize the number of animals used. The cerebral cortex was dissected from KunMing mice (one day old) obtained from the Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Following careful removal of meninges, tissues were dissected and cut into small pieces using sharp blades, then digested in 1-2 ml of Trypsin/EDTA in a 37 °C water bath for 8 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the tissue was gently triturated using a 1 ml pipette. The homogenate was centrifuged at 180 g for 5 min. The pellet was re-suspended and seeded in a T75 flask pre-coated with poly-L-ornithine. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium, supplemented with 10% FBS at a density of 1 × 104/cm2. Twenty four hours after the initial plating, the media were changed with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin, and suspended cells were removed. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 7 days. The dishes were shaken at 260 rpm / min (2 h, 37 °C) to obtain purified astrocytes. The remaining enriched astrocyte culture was exposed to 0.5% trypsin for 5 min to cause detachment of the glial monolayer, and cells were then re-plated in a new T75 flask to further purify astrocytes. The astrocytes were used after three times of passage at day 21 for all the experiments.

Cell suspension and adhesion experiment

HEK293 cells were suspended using cell dissociation buffer and collected by centrifugation (180 g, 5 min) to remove the supernatant. Then cells were suspended in PBS and seeded into 96-well plate. For the suspension condition, the well was coated with 1% BSA. For the adhesion condition, the surface of the well was coated with poly-D-lysine (PDL) (5 μg/cm2). The cells were kept in the wells for 3-4 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2, then lysis buffer was added directly for further measurement of IP1 production measurements.

PDL and FN treatment

Poly-D-lysine (PDL) coated surfaces were prepared by incubating 5 μg/cm2 PDL dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline in uncovered tissue culture dishes overnight at 37 °C. Fibronectin (FN)-coated surfaces were prepared by incubating 5 μg/cm2 FN diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in tissue culture dishes overnight at 37 °C as reported99. The HEK293 cells expressing indicated plasmids were seeded into PDL-coated wells or FN-coated wells with culture medium for 24 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Then cells were lysed for IP1 production measurements.

Shear Stress loading experiments

A peristaltic pump (BT-CA600, Naturethink, China) was used to drive a stable flow shear stress. HEK293 cells were seeded on glass plates pre-coated with FN, then transfected with the indicated plasmids when cells grew to ∼80% confluence. After 24 h, glass plates were transferred onto a parallel-plate flow chamber (C901) and subjected to 15 dyn/cm2 (1.5 Pascals) of shear stress for 15 min, followed by IP1 production measurement.

IP1 measurement

IP1 production was measured using the IP-One HTRF kit (62IPAPEB, Revvity, Codolet, France). Cryptate-labeled anti-IP1 monoclonal antibody and d2-labeled IP1 were diluted in lysis buffer and added to the cell lysis in 96-well plate. After 1 h of incubation at 25 °C, the plates were read in PHERAstar FS (BMG Labtech, USA) with excitation at 337 nm and emission at 620 and 665 nm. The accumulation of IP1 concentration (nM) was calculated according to a standard dose-response curve.

Gi1 protein dissociation measurement

HEK293 cells were transfected with optimized Gi protein sensors. For control cells with Gi sensor alone: vector, Gαi-Nluc and Venus-Gγ2 (70 ng + 1.5 ng + 20 ng/well in 96 well plate, 1270 ng + 30 ng + 350 ng /well in 6 well plate); For GABAB receptor and Gi sensor: GB1, GB2, Gαi-Nluc and Venus-Gγ2 (30 ng + 40 ng+ 1.5 ng + 20 ng, 550 ng + 720 ng + 30 ng + 350 ng/well in 6 well plate). After 24 h of culture, cells in both 96-well plate and 6-well plate were starved in PBS for 30 min. Cells from 6-well plates were then detached using Versene (Gibco, #15040066, Shanghai, China), collected by centrifugation (180 g, 5 min), and resuspended in the same 96-well plate alongside adherent cells for BRET signal measurement. The signals emitted by the donor (460-500 nm band-pass filter, Em 480 nm) and the acceptor (510-550 nm band-pass filter, Em 530 nm) were recorded after the addition of 10 μM furimazine using the PHERAstar FS (BMG Labtech, USA) with the program PHERAstar control (Version 4.00 R4). All measurements were performed at 37 °C. The BRET signal (BRET ratio) was determined by calculating the ratio between the emission of acceptor and donor (Em 530 nm / Em 480 nm). The net BRET calculation is described in the corresponding figure legend.

Laminar shear stress stimulation

Coverslips were plated in the laminar shear stress imaging chamber (open diamond bath imaging chambers RC-26, Warner) prior to experiments. Then chambers were mounted onto the microscope and connected to the peristaltic pump (ISM827B, Ismatec). Continuous laminar flow was applied to cells for 100 s.

Shear stress (τ) in arterial segments was calculated in the following equation, according to previous research91,

where Q is the flow rate, μ is fluid viscosity and d is arterial diameter.

Polytetrafluoroethylene capillary tubes (d = 0.5mm) were adapted to model arteries and only focused on the fluorescence from transfected cells next to the fluid input terminal, enabling the estimation of the fluid shear stress on the surface of the coverslips. To calculate a specific value of shear stress, the flow rate (Q = 4.8 ml·min-1) of imaging buffer was controlled through a peristaltic-pump and measured the viscosity of fluid flow (μ = 0.681 ± 0.017 mPa·s, mean ± s.e.m., n = 8) through viscometers. Finally, all the parameters were brought into Eq. (1) to calculate the value of fluid shear stress (τ = 4.44 ± 0.11 Pa, mean ± s.e.m.).

Calcium imaging

For HEK293 cells, they were seeded onto FN-coated coverslips 6 hours after plasmid transfection. After another 24 hours, HEK293 cells were incubated with 1 μM Fluo4-AM in the imaging buffer (130 mM NaCl, 5.1 mM KCl, 0.42 mM KH2PO4, 0.32 mM Na2HPO4, 5.27 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES, 3.3 mM Na2CO3, 1 mM MgSO4, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.1% BSA, 2.5 mM probenecid, pH adjusted to 7.4) for 30 min at 37 °C. For primary astrocytes, they were incubated with 1 μM Fluo4-AM in the imaging buffer (145 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, 3.3 mM Na2CO3, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, pH adjusted to 7.4) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed with imaging buffer and pre-incubated for 5 min at room temperature before calcium imaging. Intracellular Ca2+ fluorescence intensity was measured at 485 nm to indicate basal signal (Fbasal) and response signal under stimulation of shear stress or baclofen (Fresponse). The fluorescence ratio (ΔF/F = (Fresponse-Fbasal) / Fbasal)100 was calculated to represent the effect of shear stress or drugs on calcium signaling.

RNA interference

The integrin β3 siRNA (#sc-63292) and control siRNA (#sc-37007) were purchased from Santa Cruz (Shanghai, China) and the GB1 siRNAs were synthesized from GenePharma (Suzhou, China) and the sequences are: GCGGUUUCCAACGUUCUUUTT (Forward), AAAGAACGUUGGAAACCGCTT (Reverse); GCUACAAGAAGAUCGGCUATT (Forward), UAGCCGAUCUUCUUGUAGCTT (Reverse); GGGAGAAGCCAGUUCCCAUTT (Forward), AUGGGAACUGGCUUCUCCCTT (Reverse).

To knockdown integrin β3 expression, HEK293 cells were transfected with lipofectamine 2000 mixed with integrin β3 siRNA, with a lipid/siRNA ratio at 2:1. The cells were then cultured for 24 h and subjected to IP1 measurements. In parallel, Western blotting was performed to confirm the knockdown of integrin β3.

To knock down GABAB receptor expression, primary astrocytes were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 mixed with GB1 siRNA. The GFP plasmid was co-transfected as reporter of transfection. The lipid/DNA and siRNA ratio was 3:1. Cells were then cultured for 48 h and subjected to Western blotting, calcium imaging and fluorescent imaging. In parallel, quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed to confirm the knockdown of GB1. The total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Life Technologies), and qPCR reactions were performed in a 96-well format using Power SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The following primers were used: GB1 forward: ACAGACCAAATCTACCGGGC, GB1 reverse: GTGCTGTCGTAGTAGCCGAT. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

For HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor with HA-tagged GB1 and Flag-tagged GB2 (HA-GB1 and Flag-GB2), cells were lysed 24 hours after transfection with immunoprecipitation (IP) cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, with complete proteinase inhibitors, pH adjusted to 7.5) on ice for 30 min. For HEK293 cells transfected with GABAB receptor with HA and Snap-tagged GB1, and Flag-tagged GB2 (HA-Snap-GB1 and Flag-GB2), cells were first labeled with 100 nM Snap-649 24 hours after transfection in culture medium at 37 °C for 2 h, then lysed with IP lysis buffer. Lysate were centrifuged at 11,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated with anti-HA or anti-integrin β3 antibody overnight at 4 °C on a rotating wheel and then incubated with Protein G Beads (60 µL of a 50% bead slurry, Millipore) for 4–6 h at 4 °C. The pellet was washed four times with 600 µL of IP cell lysis buffer and resuspended with 2 × SDS sample buffer. Samples were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min and subjected to Western blotting analysis.

Western blotting

Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on 8 to 12% gels. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and washed in blocking buffer (10% BSA in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween 20) for 2 hours at room temperature. The blots were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and then incubated with HRP-linked or fluorescent dye-linked secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. Immunoblots were detected using PierceTM enhanced chemiluminescence reagents and visualized by X-ray film, or the membranes were imaged on an Odyssey CLx imager (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA) at 700 nm and 800 nm. The density of immunoreactive bands was measured by Image J software and normalized as the fold of the basal control.

BRET titration experiment

BRET titration experiments were performed to measure the direct interaction between proteins. Increasing amounts of Venus-tagged receptors were co-expressed with constant amounts of Rluc-tagged receptors in HEK293 cells and cultured for 24 h. Then, after one time wash with PBS, the substrate coelenterazine h (5 μM) was added and BRET signals (emission light at 480 nm and 530 nm, respectively) were detected by Mithras LB940 (Berthold Technologies, Germany). The BRET signals were plotted against the relative expression levels of each tagged receptor. netBRET ratio = [YFP emission at 530 nm/Rluc emission 480 nm] (where Rluc-tagged receptor is cotransfected with Venus-tagged receptor) - [YFP emission at 530 nm/Rluc emission 480 nm] (where Rluc-tagged receptor is transfected alone), in the same experiment. The results were analyzed by nonlinear regression assuming a model with one-site binding (GraphPad Prism, version 8, GraphPad software) on a pooled dataset from three independent experiments.

Fluorescent imaging

HEK293 cells and astrocytes were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and blocked with 2% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. HEK293 cells were stained with 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 30 min. Then cells were washed with PBS and mounted with FluorSave reagent (AR1109, Boster Biological Technology Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China) for fluorescent imaging. Astrocytes were incubated with a primary mouse monoclonal GFAP antibody (1:100) at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with PBS, cells were incubated with a secondary anti-mouse-Cy3 antibody at room temperature for 2 hours. After another washing of three times with PBS, the astrocytes were incubated with DAPI at room temperature for 30 min. Then cells were washed with PBS and mounted with Fluorsave reagent.

Fluorescent images of labeled cells were acquired using an Olympus FV3000 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (60 × objective, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with appropriate fluorescence and filters (DAPI: 405/449 nm; YFP: 488/519 nm; RFP: 543/620 nm; Cy3: 543/620 nm; DAPI: 405/449 nm; GFP, 488/519 nm). The images were digitized and saved in TIFF format. respectively, more than five microscopic fields were randomly chosen for analysis. Images were processed and fluorescence (yellow in merge panels) was quantified with the Image J plugin JACoP using Manders’ co-localization coefficients M1&M2. The settings of the confocal microscope were kept the same for all images when fluorescence intensity was compared. The intensity and area of GFAP were quantified using ImageJ software.

Intracellular calcium release measurements

HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the indicated GABAB receptor and a chimeric protein Gqi9 for 24 h. The cells were then preincubated for 1 h with Ca2+-sensitive Fluo-4 (Life Technologies). The fluorescence signals (excitation at 485 nm and emission at 525 nm) were measured for 60 s (Flexstation 3, Molecular Devices) and recorded using a Flexstation 3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The agonist was added after the first 20 s. The Ca2+ response is expressed as an agonist-stimulated increase in fluorescence.

Cross-linking and fluorescent-labeled blot experiments

HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-Snap-GB16.56 and Flag-Halo-GB26.56 by Lipofectamine 2000 and plated in 12-well plates for 24 h. Then, cells were labeled with 100 nM Snap-649, a non-cell-permeant dye, in culture medium at 37 °C for 2 h. Cells were treated in different mechanical force condition with or without GABA (100 μM) treatment. Afterwards, cross-link buffer (1.5 mM Cu(II)-(o-phenanthroline), 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgSO4, 16.7 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0 and 100 mM NaCl) was added at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation with 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide at 4 °C for 15 min to stop the cross-linking reaction, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) at 4 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, supernatants were mixed with loading buffer at 37 °C for 10 min. In reducing conditions, samples were treated without DTT in loading buffer for 10 min before loading the samples. Equal amounts of proteins were resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). Membrane was imaged on an Odyssey CLx imager (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA) at 800 nm.

Inter subunit FRET sensor measurement

ACP-tag was inserted in the extracellular lobe1 of GB1b subunitand Snap-tag was inserted in the N-terminal of GB2 subunit69. HEK293 cells were co-transfected to express GB1b subunit with the extracellular ACP-tag inserted in the lobe1 and N-terminal Snap-tag GB2 subunit using Lipofectamine 2000 in a 100-mm cell culture dish following the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were plated in fibronectin (FN)-coated or polyornithine (PLO)-coated white 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One) at 105 cells per well and cultured 24 h at 37 °C and followed by 12 h at 30 °C with 5% CO2.

To covalently label CoA-Lumi4®-Tb and Snap-Green on GABAB receptors, combined labeling of Snap- and ACP-tag were performed following the protocol described previously with a small modification101. Briefly, transfected cells were first incubated with 300 nM Snap-Green in DMEM (1 ×) + GlutaMaxTM-I medium for 1 h at 37 °C, then washed once and incubated with 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2 μM CoA-Lumi4®-Tb and 1 µM Sfp synthase in Tag-Lite® buffer for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Next, cells were washed three times in Tag-Lite® buffer, and incubated with 60 μL Tag-Lite® buffer. The trFRET measurements were performed in Greiner white 96-well plates, using a PHERAstar FS microplate reader with the following setup; after excitation with a laser at 337 nm (40 flashes per well), the fluorescence was collected at 520 nm. The acceptor ratio was calculated using the sensitized acceptor signal integrated over the time window [50 µs-100 µs], divided by the sensitized acceptor signal integrated over the time window [900 µs-1150 µs].

Molecular modeling and sequence alignment

The molecular model of GB1 VFT is generated with PyMOL software (Palo Alto, CA, USA) based on the cryo-EM structure of the GABAB receptor (PDB: 7EB2). A model of GB1 VFT to show the residues in LB2 substituted by N-glycan was retrieved from GPCRdb. The protein sequences of the GABAB1a subunit in various species were collected in UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org). The multiple sequence alignment was generated using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) and the graphic was prepared on the ESPript 3.0 server (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi).

Statistical analysis

Data are means ± s.e.m. from at least three independent experiments and statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 8 software. P-values were determined using the unpaired t test (two-tailed), paired t test (two-tailed) or ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant). P > 0.05 was considered statistically not significant (ns). For dose-response experiments, data are normalized and analyzed using nonlinear curve fitting for the log (agonist) vs. response (three parameters) curves.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bowery, N. G. et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXIII. Mammalian gamma-aminobutyric acidB receptors: structure and function. Pharm. Rev. 54, 247–264 (2002).

Ulrich, D. & Bettler, B. GABAB receptors: synaptic functions and mechanisms of diversity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 298–303 (2007).

Bassetti, D. Keeping the Balance: GABAB Receptors in the Developing Brain and Beyond. Brain Sci. 12, 419 (2022).

Enna, S. J. & Bowery, N. G. GABAB receptor alterations as indicators of physiological and pharmacological function. Biochem Pharm. 68, 1541–1548 (2004).

Schuler, V. et al. Epilepsy, hyperalgesia, impaired memory, and loss of pre- and postsynaptic GABAB responses in mice lacking GABAB1. Neuron 31, 47–58 (2001).

Heaney, C. F. & Kinney, J. W. Role of GABAB receptors in learning and memory and neurological disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 63, 1–28 (2016).

Jacobson, L. H. et al. Differential roles of GABAB1 subunit isoforms on locomotor responses to acute and repeated administration of cocaine. Behav. Brain Res. 298, 12–16 (2016).

Bettler, B., Kaupmann, K., Mosbacher, J. & Gassmann, M. Molecular structure and physiological functions of GABAB receptors. Physiol. Rev. 84, 835–867 (2004).

Mariotti, L., Losi, G., Sessolo, M., Marcon, I. & Carmignoto, G. The inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA evokes long-lasting Ca2+ oscillations in cortical astrocytes. Glia 64, 363–373 (2016).

Cheng, Y. T. et al. Inhibitory input directs astrocyte morphogenesis through glial GABABR. Nature 617, 369–376 (2023).

Gould, T. et al. GABAB receptor-mediated activation of astrocytes by gamma-hydroxybutyric acid. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20130607 (2014).

Jafarian, M. et al. The effect of GABAergic neurotransmission on the seizure-related activity of the laterodorsal thalamic nuclei and the somatosensory cortex in a genetic model of absence epilepsy. Brain Res. 1757, 147304 (2021).

Cediel, M. L. et al. GABBR1 monoallelic de novo variants linked to neurodevelopmental delay and epilepsy. Am. J. Hum. Genet 109, 1885–1893 (2022).

Felice, D., Cryan, J. F. & O’Leary, O. F. GABAB Receptors: Anxiety and Mood Disorders. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 52, 241–265 (2022).

Jacobson, L. H. et al. The Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid B Receptor in Depression and Reward. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 963–976 (2018).

Frankowska, M., Filip, M. & Przegalinski, E. Effects of GABAB receptor ligands in animal tests of depression and anxiety. Pharm. Rep. 59, 645–655 (2007).

Chang, E. et al. A Review of Spasticity Treatments: Pharmacological and Interventional Approaches. Crit. Rev. Phys. Rehabil. Med 25, 11–22 (2013).

Cousins, M. S., Roberts, D. C. & de Wit, H. GABAB receptor agonists for the treatment of drug addiction: a review of recent findings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 65, 209–220 (2002).

Malcangio, M. GABAB receptors and pain. Neuropharmacology 136, 102–105 (2018).

Vuillaume, M. L. et al. A novel mutation in the transmembrane 6 domain of GABBR2 leads to a Rett-like phenotype. Ann. Neurol. 83, 437–439 (2018).

Yoo, Y. et al. GABBR2 mutations determine phenotype in rett syndrome and epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol. 82, 466–478 (2017).

Henderson, C. et al. Reversal of disease-related pathologies in the fragile X mouse model by selective activation of GABAB receptors with arbaclofen. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 152ra128 (2012).

Nieto, A., Bailey, T., Kaczanowska, K. & McDonald, P. GABAB Receptor Chemistry and Pharmacology: Agonists, Antagonists, and Allosteric Modulators. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 52, 81–118 (2022).

Holtyn, A. F. & Weerts, E. M. GABAB Receptors and Alcohol Use Disorders: Preclinical Studies. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 52, 157–194 (2022).

Logge, W. B., Morley, K. C. & Haber, P. S. GABAB Receptors and Alcohol Use Disorders: Clinical Studies. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 52, 195–212 (2022).

Tedeschi, L. et al. Endogenous gamma-hydroxybutyric acid is in the rat, mouse and human gastrointestinal tract. Life Sci. 72, 2481–2488 (2003).

Auteri, M., Zizzo, M. G. & Serio, R. GABA and GABA receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: from motility to inflammation. Pharm. Res 93, 11–21 (2015).

Hyland, N. P. & Cryan, J. F. A Gut Feeling about GABA: Focus on GABAB Receptors. Front Pharm. 1, 124 (2010).

Pin, J. P. & Bettler, B. Organization and functions of mGlu and GABAB receptor complexes. Nature 540, 60–68 (2016).

Shen, C. et al. Structural basis of GABAB receptor-Gi protein coupling. Nature 594, 594–598 (2021).

Thor, C. M., David, M.-D., Jean-Philippe, P. & Julie, K. Class C G protein-coupled receptors:reviving old couples with new partners. Biophysics Rep. 3, 57–63 (2017).

Park, J. et al. Structure of human GABAB receptor in an inactive state. Nature 584, 304–309 (2020).

Mao, C. et al. Cryo-EM structures of inactive and active GABAB receptor. Cell Res 30, 564–573 (2020).

Shaye, H. et al. Structural basis of the activation of a metabotropic GABA receptor. Nature 584, 298–303 (2020).

Papasergi-Scott, M. M. et al. Structures of metabotropic GABAB receptor. Nature 584, 310–314 (2020).

Xue, L. et al. Rearrangement of the transmembrane domain interfaces associated with the activation of a GPCR hetero-oligomer. Nat. Commun. 10, 2765 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Allosteric ligands control the activation of a class C GPCR heterodimer by acting at the transmembrane interface. Elife 10, e70188 (2021).

Wang, N. et al. Mechanical behavior in living cells consistent with the tensegrity model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7765–7770 (2001).