Abstract

Although tuberculosis is preventable, whom to prioritize for preventive interventions is debated. As part of a follow-up to a mass tuberculosis screening, we aimed to evaluate tuberculosis incidence among persons with distinct baseline X-ray results. From March to October 2020, we implemented a mass tuberculosis screening intervention among elderly persons in eastern China. Participants were followed for incident tuberculosis until October 2022. Tuberculosis incidence over two years among participants with differing baseline chest X-ray results were assessed. Physical examinations and X-rays were administered to all participants. Among persons suspected of tuberculosis, computed tomography, culture or GeneXpert MTB/RIF was performed. Among 183,808 participants, 27,796 had a baseline abnormal X-ray. The annualized incidence per 100,000 person-years was 1,525 (95% CI, 989-2,243), 278 (202-373), 325 (218-466), and 61 (50–75) among participants with X-rays suggestive of active, stable, uncertain and normal, respectively. Among persons with X-ray findings suggestive of tuberculosis, the increased hazard was 16.7 (95% CI, 11.9–23.4). These results demonstrate the risk of developing tuberculosis among persons with an abnormal chest X-ray was very high. Combining mass screening with preventive interventions based on X-ray findings should be explored as a combination intervention package to reduce tuberculosis in high-risk populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis is amongst the leading infectious disease killers globally. In 2022, there was an estimated 10.6 million new tuberculosis patients worldwide1. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to substantial reduction in tuberculosis case detection in 2020 and 20212,3. These impacts have led to calls for additional supplementary interventions, such as mass active case finding among high-risk populations, to improve case detection in settings with a high burden of tuberculosis4,5.

Recently, there has been a renewed interest in mass tuberculosis screening as both an intervention to increase case detection and prevent subsequent Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission6,7,8. The World Health Organization recommends systematic screening among certain at-risk populations including people with human immunodeficiency virus and exposed persons9. A systematic tuberculosis screening strategy using chest X-ray as an initial screening test, followed by diagnostic assessment for those with abnormal findings, aims to detect tuberculosis early and initiate prompt treatment. Recent surveys in Vietnam found a reduction in community tuberculosis prevalence after multiple rounds of systematic screening6. There remain several unanswered questions about the utility of mass tuberculosis screening.

In China, a large proportion of identified tuberculosis, up to 40% in some areas, are among the elderly10,11. Whether targeting this group for mass tuberculosis screening has public health impact has not been investigated12. Additionally, whether mass tuberculosis screenings should include follow-up for persons at especially high-risk of tuberculosis progression has not been thoroughly explored. The historical literature suggests that persons with abnormal chest X-rays may have as much as 10% risk of incident tuberculosis, suggesting prioritizing them for preventive interventions may be useful13. In the past 50 years, few large-scale, population-level mass screening interventions have been implemented and reported to assess populations at high-risk to develop tuberculosis after mass screening interventions.

To further investigate these questions, we conducted a large mass tuberculosis screening among elderly residents aged 65 and older in a rural, high-incidence area of eastern China. Participants were stratified based on distinct chest X-ray features and a cohort was established for follow-up to identify subsequent active tuberculosis patients. Our primary aim of this study was to assess whether there was an increased tuberculosis risk among those with distinct chest X-ray abnormalities, and to evaluate factors that might influence the development of tuberculosis across distinct chest X-ray classifications during the screening period and over the subsequent two years of follow-up. This study provides data to support policymaking for tuberculosis screening and control measures in high-risk populations.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

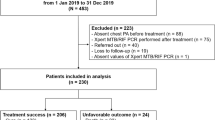

As shown in Fig. 1., in 2020, 187,065 persons participated in a mass tuberculosis screening. Of these, 3,257 were excluded, including 343 (11%) younger than 65 years old, 969 (30%) who did not participate in the chest X-ray examination, and 1,945 (60%) who had a chest X-ray performed but had incomplete data, leaving 183,808 included in the study. Among the 3,257 excluded participants, matching their information with the tuberculosis information system revealed no patients of tuberculosis. Of the 183,808 participants included, 156,012 (84.9%) had normal chest X-rays and 27,796 (15.1%) had abnormal chest X-rays. Among those with abnormal X-rays, 1,988 (7.2%) showed active signs, 9,275 (33.4%) showed uncertain signs, and 16,533 (59.5%) showed stable signs. Of the stable signs, 9,309 (56.3%) were fibrotic lesions, 2,930 (17.7%) were nodular lesions, and 4,294 (26.0%) were calcified lesions. Among the uncertain signs, 5,249 (56.6%) were patchy and 4,026 (43.4%) were non-patchy. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants by chest X-ray classification were detailed in Table 1. The number of participants excluded and retained at different stages for different chest X-ray classifications is shown in detail in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Screening period

During the screening period, among 27,796 individuals with abnormal chest X-rays, 3,953 (14.2%) underwent subsequent tuberculosis diagnostic tests. Those with active chest signs had the highest rate (90%; 1790/1988) of referral for further diagnostic testing (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 174 participants were identified and diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, of which 94% (164/174) were found to have abnormal chest X-ray (Supplementary Table 2). Among these patients, 43 were sputum smear-positive, 55 were sputum culture-positive, and 76 were GeneXpert-positive (Supplementary Table 3). A total of 55 (31.6%) patients were diagnosed with subclinical tuberculosis.

The prevalence of confirmed tuberculosis was 111 cases among 183,808 persons (60 cases per 100,000 screened persons). Compared with those who showed no abnormalities in chest X-ray, the detection ratios of pulmonary tuberculosis in participants with stable, uncertain, and active tuberculosis were 2.92 (95% CI, 0.30-28.07), 5.43 (95% CI, 0.56–52.22) and 2539.29 (95% CI, 798.12-8,078.94), respectively (Supplementary Table 4). During the screening period, few cases were diagnosed among participants with fibrous lesions (1/9,309; <1%), sclerotic lesions (0/2930; 0%), and calcifications (0/4,294; 0%) with detection ratios of 6.98 (95% CI, 0.71–68.60), 0, and 0, respectively. No subgroup of participants in stable and uncertain chest X-ray categories had statistically higher odds of being diagnosed with tuberculosis during screening compared with participants without abnormalities. During the screening period, 253 deaths occurred, with zero attributed to tuberculosis (Supplementary Table 5).

Incidence and risk of normal and abnormal chest X-ray during different follow-up periods

After baseline screening and exclusion of prevalent tuberculosis, 183,382 participants were followed for two years with a total of 362,235 person-years. Overall, there were 4330 deaths among the study population throughout the two-year follow-up period, with a total of 4 deaths due to tuberculosis (Supplementary Table 5). During the first and second year of follow-up, diagnostic tests for tuberculosis were performed on 10.4% (19,045/183,382) and 12.4% (22,490/181,282) of participants, respectively (Supplementary Table 6 and 7). In each of these time periods, 372 (372/183,382; 0.20%), and 359 (359/181,282; 0.20%) patients with tuberculosis were identified (Supplementary Table 2). During the first year of follow-up, 87 (87/372; 23.4%) patients with tuberculosis were sputum smear-positive, 142 (142/372; 38.2%) were culture-positive, and 169 (169/372; 45.4%) were GeneXpert MTB/RIF-positive (Supplementary Table 8). In the second year, 68 (68/359; 18.9%) patients with tuberculosis were sputum smear-positive, 104 (104/359; 29.0%) were culture-positive, and 151 (151/359; 42.1%) were GeneXpert MTB/RIF-positive (Supplementary Table 9). In the first and second years of follow-up, 80 (21.5%) and 73 (20.3%) individuals were diagnosed with subclinical tuberculosis, respectively.

In total, 429 confirmed active tuberculosis patients were identified, with an incidence rate of 118 cases per 100,000 person-years., with a predominance of males diagnosed (N = 318, 74.1%). We first analyzed the study population by all post-screening follow-up. At baseline, the incidence per 100,000 person-years were 464 and 58 among those with and without abnormal chest radiographs. More total incident tuberculosis patients were diagnosed among participants with an abnormal chest X-ray at baseline (N = 249) compared with those without (N = 180), despite far fewer participants in this subgroup (27,549 versus 155,833). People with abnormal chest X-rays had 5.90 (95% CI, 4.83–7.21) higher risk of developing tuberculosis than those without. In the primary analysis (second year of follow-up), 192 pulmonary tuberculosis patients were identified, with an overall incidence rate of 108 per 100,000 person-years. Most patients were male (N = 143, 74.5%). The rates were 371 and 61 per 100,000 person-years for those with and without abnormal chest X-rays, respectively. Results from a multivariable Cox model was similar to the prior model with longer follow-up (aHR, 4.54; 95% CI, 3.38–6.10) (Table 2).

Over the entire follow-up period (both years), the aHRs for tuberculosis was 3.98 (95% CI: 3.09–5.12), 5.64 (95% CI: 4.27–7.44), and 24.46 (95% CI: 18.41–32.49) for stable, uncertain, and active disease signals, respectively, compared to those with no abnormalities on chest X-rays. During only the second year of follow-up, the aHRs for stable, uncertain, and active signs of tuberculosis were 3.48 (95% CI, 2.41–5.02), 4.46 (95% CI, 2.93–6.79) and 14.30 (95% CI, 8.89–23.00), respectively (see Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 10).

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio. Models are adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and prior tuberculosis. Referent category are persons with no abnormal X-ray findings at the baseline mass screening visit. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI). A Follow-up was not restricted and included all follow-up (up to 2 years) for participants after screening (all cases). B Follow-up time for development of tuberculosis began 1 year post-completion of the mass screening intervention.

Throughout the 2-year follow-up period, the aHRs of tuberculosis in those with fibrous lesions, sclerotic lesions, and calcifications on baseline X-rays was 3.96 (95% CI, 2.94–5.34), 5.56 (95% CI, 3.60–8.61), and 1.64 (95% CI, 0.87–3.11) times higher than participants without abnormalities. Among participants with patchy and non-patchy lesions, the increased risk of tuberculosis was 4.25 (95% CI, 2.91–6.21) and 6.83 (95% CI, 4.81–9.69), respectively. When restricting to second year of follow-up, participants with fibrous lesions, sclerotic lesions and calcifications had risks of 3.87 (95% CI, 2.53-5.92), 4.26 (95% CI, 2.15–8.47) and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.49–3.62), respectively, compared with those without chest X-ray abnormalities. The HRs of pulmonary tuberculosis among participants with patchy lesions and non-patchy lesions (compared to a reference group without abnormal X-ray findings) was 3.92 (95% CI, 2.26-6.79) and 4.98 (95% CI, 2.83–8.78) (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 11).

Cox proportional hazards models show adjusted hazard ratios for the development of confirmed tuberculosis among participants with differing subcategories of uncertain and stable chest X-ray findings. Models are adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and prior tuberculosis. The unit of study is the individual participant; all data points represent biological replicates (n = 183,382 independent subjects across all groups). The screening time period occurred from March 1 to October 31, 2020. The total follow-up time period was defined as November 1, 2020–October 31, 2022. Referent category are persons with no abnormal X-ray findings (n = 155,833) at the baseline mass screening visit. Precise sample sizes for each subgroup are as follows: Uncertain, non-patchy lesions (n = 4002); Uncertain, patchy lesion (n = 5243); Stable, fibrous lesion (n = 9290); Stable, sclerotic lesion (n = 2920); Stable, Calcification (n = 4277). To account for any undiagnosed, early tuberculosis patients that may have been diagnosed in year 1 of follow-up, a secondary follow-up period with a one year lead-in time was analyzed. This time period began > 1 year after completion of screening and ran from November 1, 2021–October 31, 2022. Referent category are persons with no abnormal X-ray findings (n = 154,447) at the secondary follow-up period. Precise sample sizes for each subgroup are as follows: Uncertain, non-patchy lesions (n = 3819); Uncertain, patchy lesion (n = 5202); Stable, fibrous lesion (n = 9080); Stable, sclerotic lesion (n = 2857); Stable, Calcification (n = 4163).Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Two-year follow-up identified male (HR = 3.26, 95%CI, 2.63–4.05), over 75 years of age (HR = 1.59, 95%CI, 1.31–1.93), underweight (HR = 3.21, 95%CI, 2.57–4.00), previous tuberculosis (HR = 4.71, 95%CI, 3.47–6.39) as risk factors for developing tuberculosis (Supplementary Table 12).

Discussion

We analyzed the risk of incident tuberculosis associated with a baseline abnormal screening chest X-ray among over 180,000 elderly individuals from eastern China, assessed over 362,233 participant-years of follow up. Our study demonstrated that an abnormal X-ray substantially increased the risk of incident tuberculosis (by up to 200 to 500%) and that the annual risk of developing tuberculosis among persons with an X-ray suggestive of tuberculosis (but bacteriologically negative and not clinically diagnosed) was above 3,000 cases per 100,000 persons.

To our knowledge, this is the largest population-based, prospective study to evaluate the risk of tuberculosis among persons with distinct chest X-ray findings13. We found that 1817 participants with an X-ray suggestive of tuberculosis had a multi-fold higher disease risk over two years of follow-up. In our cohort, the annualized rate of tuberculosis progression was high at ~3%, or 3,000 cases per 100,000 person-years. A recent synthesis of historical studies including 1199 participants with chest X-ray suggestive of tuberculosis found that the annual rate of tuberculosis (based on conversion from microbiologically negative to positive from either culture or smear testing) was ~10% (95% CI, 6.2–13.3)13. Reasons for the discrepancy between these historical studies and our analysis are unclear but is likely multifold. First, there was wide between-study heterogeneity within this synthesis ranging from 3–16%, suggesting that other characteristics not included within this analysis (eg, baseline symptom status, previous tuberculosis history, secondary comorbidities) may have influenced pooled estimates. Second, although our study was prospective, the passive follow-up is likely to underestimate longitudinal risk estimates among this group. Lastly, our study includes and focuses on an elderly population; there may be a difficulty of sputum collection among this population which would lead to underdiagnosis compared to some younger populations.

The especially high-risk of tuberculosis among persons with chest X-rays suggestive of active, unstable tuberculosis is concerning. This rate suggests that these individuals are likely to have early-stage tuberculosis, prior to fully microbiologically positive, active tuberculosis. In the past decade, there has been a push to understand the distinct stages of tuberculosis, including those that occur prior to fully active, microbiologically positive manifestations and post-tuberculosis14,15. Large-scale cohort studies such as this study are needed to better understand the prevalence of distinct stages of disease as well as future risk. Tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, such as the tuberculin skin test or interferon gamma assays, as well as transcriptomic profiling may be useful to further delineate and group participants in their disease process15,16,17. Integrating these tools into one cohort will be a challenge but is needed to continue to improve our understanding in distinct settings.

Although our results suggest that persons with active or inactive abnormal chest X-rays have an increased risk of subsequently developing tuberculosis, how best to manage this population is not clear. Potentially, a mass tuberculosis screening intervention could be paired with targeted preventive intervention for persons that are bacteriologically negative but with an X-ray suggestive of either active or inactive tuberculosis18,19. Historical studies have found mixed results. A recent randomized trial of 677 persons with radiographically inactive tuberculosis lesions and a positive QuantiFERON test from China evaluated whether a 6-week rifapentine and isoniazid preventive therapy regimen effectively averted subsequent tuberculosis20. The trial found similar rates of incident tuberculosis over two years of follow-up among those given and not given tuberculosis treatment (2.3% versus 2.1%) however the overall number of events was low. Which preventive treatment regimen to use in elderly populations is also debated21,22. Further research is needed to understand whether a further targeted intervention to participants with any X-ray abnormality would be beneficial. Our results also indicate that persons that test bacteriologically negative but with X-rays classified as suggestive of tuberculosis may be at especially high-risk of developing tuberculosis. Alternatively, these persons may already have early-stage tuberculosis and may benefit from an attenuated anti-tuberculosis treatment23. Future trials are needed to answer these questions.

The findings of this study offer several important insights about mass screening and tuberculosis risk. First, after active screening, partnered interventions may be guided by the different types of abnormal imaging results for high-risk populations. For individuals exhibiting signs of active tuberculosis, uncertain signs, or those with cavities, strengthening pathogen detection based on sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid sampling, fully utilizing the sensitivity and timeliness advantages of molecular diagnostic technologies to achieve early diagnosis and prompt treatment. For clinical diagnoses without supporting pathogen evidence, standardized evaluation of the effectiveness of anti-tuberculosis treatment should be conducted to support clinical diagnosis and improve treatment completion rates24. These recommendations need further validation in different regions and populations across China. Second, preventive interventions—such as preventive treatment or a full disease treatment regimen— among persons without microbiologically-positive tuberculosis but suggestive X-rays should be further explored. In China and most other settings, this population is not prioritized likely due a lack of empirical evidence regarding effective interventional approaches.

This study has considerable strengths. This cohort is amongst the largest mass chest X-ray screenings. Most mass screenings do not include substantial secondary information such as prior tuberculosis, tuberculosis-related symptoms, diabetes, or body mass index. This secondary data on this large sample allowed us to further identify potential confounders as well as refine specific populations in which this relationship may be most relevant. The well-defined chest X-ray data–including stratifications of stable and unknown X-ray categorizations–on such a large sample are rare.

There are limitations of this work. First, a proportion of individuals with abnormal X-rays at baseline did not undergo microbiological testing to determine if they had tuberculosis at that time. Hence, there is potential for prevalent tuberculosis to have been misclassified as incident tuberculosis. To account for this potential misclassification, we performed additional analyses that began one year after the end of the mass screening intervention, excluding cases occurring early in the follow-up time period. Our results remained largely the same. Second, although our study was prospective, the follow-up was based on a case-registry based diagnoses. Underdiagnoses would likely bias our hazard ratio estimates from our regression analyses towards the null. Third, tuberculosis case information was not electronically registered before 2005, precluding access to patient data prior to that year. Attempts to inquire about patient history were largely unsuccessful due to patients’ inability to recall details. Therefore, we were able to record a history of tuberculosis only from 2005 onward which may have resulted in misclassification. Fourth, in some subgroups of chest X-ray findings, such as fibrotic and sclerotic lesions, the number of tuberculosis events remained low despite the large sample size. This may compromise the precision of our estimates, reflecting the inherent characteristics of this cohort. The statistical power is potentially affected. Fifth, pandemic control measures during COVID-19 may have introduced potential selection bias through altered health behaviors (e.g., avoidance of crowded settings). Although the daily incidence of COVID-19 in Quzhou was low, we cannot exclude the possibility that high-risk individuals avoided screening due to perceived exposure risks. Sixth, in some participants, tuberculosis at baseline was excluded through Xpert and not culture. Although Xpert has high sensitivity, some participants with tuberculosis may have been classified as healthy at baseline. To account for this potential misclassification, we performed additional analyses that began one year after the end of the mass screening intervention, excluding individuals with tuberculosis occurring early on in the follow-up time period. Our results remained largely the same. Seventh, despite strict adherence to national guidelines, operational constraints at the primary healthcare level, including resource limitations, varying levels of staff training, and complex workflows, pose challenges to ensuring the consistency and completeness of all screening and diagnostic procedures. This inconsistency may have resulted in some participants not undergoing the full suite of scheduled examinations, thereby affecting data quality and result accuracy. Future research should focus on enhancing standardization within primary healthcare services to improve screening efficiency and diagnostic precision. Lastly, in our baseline screening, we designed the screening protocol with reference to WHO guidelines, taking into comprehensive consideration the pandemic situation, screening principles, and cost-effectiveness. Although not all screening participants underwent microbiological testing—which might have missed some potential patients—the vast majority of those with chest X-ray findings suggestive of tuberculosis received confirmatory pathogenetic examinations. Among participants with other abnormal or normal radiographic findings, microbiological testing was largely omitted; however, the number of potential undetected patients is expected to be minimal, thus exerting a limited impact on the study.

In conclusion, in a region of high incidence of TB in eastern China, mass screening by chest X-ray identified 0.01% (174/183,808; 95/100,000) of the elderly populations with active TB and identified 0.71% (381/27,549; 711/100,000) of future TB patients in which TB could have been possibly prevented with preventive chemotherapy. In addition, persons with abnormal chest X-ray findings at baseline were multifold times more likely to progress to tuberculosis. In this high-burden setting for tuberculosis, particularly among elderly individuals, tuberculosis detection was limited during the screening period. However, post-screening, targeted interventions based on the categorization of chest radiographs identified those at high risk, preventing the progression to active tuberculosis and reducing community incidence, thereby promoting the goal of ending the tuberculosis epidemic.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Quzhou City Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Approval NO:IRB-2020-R-NO.001). All participants provided informed consent for both the active screening and subsequent follow-ups. For those who were illiterate or could not read, the research staff would read the content of the informed consent to him/her, and then asked the family member to sign the consent form as an agent.

Study setting and population

Quzhou City is located in the western region of Zhejiang Province and comprises six counties (cities, districts) with 100 towns. In December 2019, there were 377,205 permanent residents aged ≥65 years, of whom 311,385 were rural residents. The reported incidence rate of pulmonary tuberculosis in the city was 67 cases per 100,000 person-years in 2019; among those aged ≥65 years, it was 194 cases per 100,000 person-years. The proportion of all pulmonary tuberculosis patients that are elderly in the city reached 41%25. Outmigration is low in Quzhou, especially among the elderly population.

Quzhou City has six designated tuberculosis laboratories (one at the prefectural level and five at the county level), all of which are BSL-2 level facilities capable of performing sputum smear microscopy, molecular testing, MGIT-320 culture, and drug susceptibility testing. Quality control in these laboratories is in accordance with guideline requirements, with a Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture contamination rate of less than 10%. Since 2015, all laboratories have successfully participated in 10 rounds of proficiency testing organized by the National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention for TB molecular diagnostics and drug susceptibility testing, with all results being satisfactory.

Study design

Active screening period

From March to October 2020, Quzhou City conducted a large-scale campaign involving active screening of all residents aged 65 years or older in the rural areas. The active tuberculosis screening intervention among the elderly was led by health administrative departments at the county level, organized and launched by township people’s governments, and supervised by county-level medical institutions. This mass screening involved a comprehensive physical examination and chest X-rays on all enrollees26. The majority of chest X-ray radiographic examinations for tuberculosis were scheduled at township health centers, as most of these centers have radiographic equipment. Among the 89 township health centers, seven that lacked on-site chest digital radiography (DR) equipment utilized mobile chest DR units for screening. Screening for tuberculosis was scheduled to coincide with the residents’ annual physical examination. At township health centers, targeted individuals underwent general health examinations and chest X-ray screenings27; images were uploaded to the local county hospital through the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) for radiological interpretation, with the results subsequently fed back to the township health centers. A diagnostic panel composed of three members (two infectious disease specialists and one radiologist) was responsible for identifying abnormalities in participants’ chest radiographs and classifying the radiographic diagnoses into normal or abnormal28. Abnormal signs were further categorized into active lesions, stable lesions, and indeterminate lesions. Stable signs were subclassified into fibrotic lesions, sclerotic lesions, and calcified lesions29,30,31, while uncertain signs were subclassified into patchy and non-patchy lesions30,31. For abnormal classification, diagnostic results consensus from at least two specialists; disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. The diagnostic panel included qualified licensed physicians, with at least one being a certified attending hospital physician (or more senior in terms of experience). All panelists received training from the Quzhou City Quality Control Center for Tuberculosis Diagnosis and Treatment. During on-site quality control, experts randomly reviewed a certain percentage of X-ray images; a concordance rate of over 90% between the evaluated image decisions and the quality control team was deemed acceptable. For individuals with active lesions, referral to designated tuberculosis hospitals for TB diagnostic tests was made to confirm or rule out active pulmonary tuberculosis. Those without active lesions were advised to seek tuberculosis diagnosis at designated hospitals if tuberculosis-related symptoms developed. In asymptomatic individuals with a chest X-ray result indicating an abnormality, referral to an appropriate healthcare facility for further evaluation and management was recommended to evaluate for other serious conditions such as lung cancer or pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis primarily relied on pathogen detection (including bacteriological and molecular biological methods), combined with epidemiological history, clinical presentation, chest imaging, relevant ancillary tests, and differential diagnosis for comprehensive analysis. Bacteriological examinations included three sputum samples for Mycobacterium tuberculosis smear microscopy (one immediate, one morning, and one night sample), liquid culture of one sputum sample, and one GeneXpert MTB/RIF test24. When sputum volume or quality was inadequate, artificial sputum induction was performed, and bronchoalveolar lavage was used when necessary to obtain sputum samples.

Screening costs were fully covered by the government as part of the Quzhou Municipal Government’s Civil Welfare Project from 2020 to 2022. A specific tuberculosis screening subsidy of 55 yuan per person (1 U.S. dollar is equivalent to 6.5 RMB at the time of the study) was provided, with 35 yuan allocated for chest X-ray costs, 15 yuan for promotional activities, organizational expenses, transportation, and follow-up, and 5 yuan reserved for subsequent diagnostic tests for those identified with active pulmonary lesions. The costs for residents’ health examinations were covered by the urban and rural health insurance funds.

Follow-up period

Follow-up was conducted quarterly by trained community health professionals through on-site visits during health service provision or via telephone interviews. Follow-up visits consisted of inquiries about tuberculosis-related symptoms, educational activities on prevention and treatment, and general health services. An end visit of 2 years (from 1 November 2020 to 31 October 2022) was scheduled for all participants unless they developed TB during follow-up, refused follow-up, or died. Individuals with active lesions during the baseline radiological assessment who were not diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, were instructed to participate in further annual health check-ups and were referred to designated hospitals for tuberculosis diagnostic testing to confirm or rule out tuberculosis. For participants with baseline X-ray findings not suggestive of tuberculosis, were instructed to self-refer to designated hospitals for tuberculosis diagnostic testing if they developed tuberculosis-related symptoms during follow-up. In addition to field visits and telephone interviews, we utilized the local Tuberculosis Management Information System (TBIMS) to capture data on confirmed tuberculosis individuals, thereby supplementing information on unvisited individuals. Confirmed patients were treated according to the standard protocol for active tuberculosis. Participants not diagnosed with tuberculosis were not prescribed preventive treatment, regardless of chest X-ray status, following Zhejiang Provincial and Chinese national guidelines. All tuberculosis patients are managed through the TBIMS maintained by the National Center for Tuberculosis Control and Prevention10. Information regarding death (including timing) was collected from the Cause of Death Registration Reporting Information System maintained by the Zhejiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Relevant definitions

Pulmonary tuberculosis, according to the People’s Republic of China Health Industry Standard WS 288-2017 for Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis24, refers to tuberculous lesions in the lung tissue, trachea, bronchi, and pleura. This includes suspected individuals with tuberculosis, clinically diagnosed patients, and confirmed patients. The diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis primarily relies on pathogen testing (including bacteriology and molecular biology), combined with epidemiological history, clinical presentation, chest imaging, related ancillary tests, and differential diagnosis, for a comprehensive analysis leading to a diagnosis. Pathogen and pathology results serve as the basis for confirmation. Confirmed patients tested microbiologically positive, which includes sputum smear positivity, and/or culture positivity, GeneXpert MTB/RIF positivity, and/or pathology positivity in lung tissue specimens. Clinically diagnosed patients were microbiologically-negative and diagnosed by a group of clinicians based on several relevant clinical characteristics which may include (but are not limited to) epidemiological history, clinical presentation infection testing results, tuberculosis exposure history, and chest imaging results. Subclinical tuberculosis was a condition caused by viable Mycobacterium tuberculosis that did not produce the symptoms associated with clinical tuberculosis but could lead to other abnormalities detectable by current radiological or microbiological testing methods. Tuberculosis-related symptoms included cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, fever, night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, or chest pain.

Active signs: including multiple nodular lesions, patchy, cloudy flocculent and lobar lung consolidations, mass-like opacities, and enlarged hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes. These lesions are featured by heterogeneous density, high central density, peripheral low density, irregular distribution, and infiltrative changes. They may be accompanied by thick-walled, thin-walled, tension cavities, and multiple moth-eaten cavities, as well as satellite lesions, bronchial dissemination, bronchial dilation, lymphangitis, and pleural effusion. Stable signs: including dense nodules, plaques, calcified nodules, fibrous strands and residual purification cavities after treatment. These lesions have clear and sharp margins and may accompany pleural and/or mediastinal lymph node calcifications. Dense nodules and plaques are classified as sclerosing lesions, fibrous striated lesions are classified as fibrotic lesions. Calcified nodules and residual purgative cavities after treatment are classified as calcified lesions. Uncertain signs: including patchy lesions and non-patchy lesions (destroyed lungs, atelectasis, tuberculomas) and other lesions that have not yet been fully calcified, cannot make a diagnosis of inactive pulmonary tuberculosis based on these signs alone; further analysis after obtaining computed tomography scans is required28.

Prior tuberculosis was defined as participants with tuberculosis treatment history registered through TBIMS from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2019. Prevalence cases were defined as those identified either actively or passively among participants during the screening period. Individuals with tuberculosis found before the screening period were not included in this study. A one-month period was allowed for referral and diagnosis following screening, thus including prevalent cases found within one month after the last screening date. Therefore, screening took place from March to September, and all cases found during the time period of March to October were defined as prevalent. Incident cases were those identified and detected either actively or passively during the follow-up period. The follow-up was during the two years post-completion of the screening period. This was from 1 November 2020 to 31 October 2022. Tuberculosis patients occurred exclusively among those who participated in the baseline screening; data from follow-up years (year 1, year 2) did not include individuals who did not partake in the baseline screening.

Elderly people were participants 65 years of age or over. Body mass index (BMI) was categorized into subgroups relevant to Asian populations, including < 18.5 kg/m² (underweight), 18.5–23.9 kg/m² (normal weight), and ≥24 kg/m² (overweight). Diabetes was defined as a prior clinical diagnosis or through a positive fasting glucose test given during the physical examination32,33.

Statistical analysis

Data was described in terms of proportions and case rates. Tuberculosis risk was analyzed by specified time periods as well as chest X-ray classification from the baseline screening visit. Time periods were divided based on initial screening (March 1 to October 31, 2020), first year of follow-up (November 1, 2020 to October 31, 2021), and second year of follow-up (November 1, 2021, to October 31, 2022). The second year of follow-up was specified to account for any unconfirmed early tuberculosis patients that may have been diagnosed in year 1 of follow-up. This time period began > 1 year after completion of screening. All analyses, except for dividing the follow-up time period into the first and second year, were pre-specified.

R version 4.2.0 was used for all analyses. Binomial logistic regression models were used to estimate the prevalence of tuberculosis among participants with different characteristics during the screening process. For the two distinct follow-up time period after screening, time-to-event data were constructed between the first date of the follow-up time period and the date of development of tuberculosis. Follow-up was censored at death, development of tuberculosis, or end of follow-up. We compared tuberculosis incidence in groups with differing chest X-ray status using hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained from Cox proportional hazard models14,34. We used Kaplan-Meier analyses to present the results of participants with distinct chest X-ray classifications developing tuberculosis at different follow-up stages. A two-sample likelihood ratio test was used.

We calculated confirmed active tuberculosis incidence in cases per 100,000 person-years for participants with distinct baseline chest X-ray findings. 95% Poisson CIs were calculated around these estimates and tuberculosis incidence rates were compared using two-sample Poisson tests.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical considerations involving sensitive personal health information. Access to these data may be granted for non-commercial academic research purposes upon reasonable request and is subjected to approval by the first author, Ping Zhu. Requests should be directed to the corresponding authors, Dr. Bin Chen (e-mail:bchen@cdc.zj.cn) and Dr. Jianmin Jiang (e-mail: jmjiang@cdc.zj.cn). Requests will be evaluated within two weeks, and the data will be available for one month after approval. All other data supporting the findings of this study, including processed results, are available in the Supplementary Information.

References

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729 (2022).

Pai, M., Kasaeva, T. & Swaminathan, S. Covid-19’s devastating effect on tuberculosis care—a path to recovery. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1490–1493 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Collateral impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on tuberculosis control in Jiangsu Province, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, 542–544 (2021).

Bhatia, V., Mandal, P. P., Satyanarayana, S., Aditama, T. Y. & Sharma, M. Mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on progress towards ending tuberculosis in the WHO South-East Asia Region. WHO South-East Asia J. Public Health 9, 95–99 (2020).

MacLean, E. L. et al. Integrating tuberculosis and COVID-19 molecular testing in Lima, Peru: a cross-sectional, diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Microbe 4, e452–e460 (2023).

Marks, G. B. et al. Community-wide screening for tuberculosis in a high-prevalence setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1347–1357 (2019).

Liu, Q. et al. Yield and efficiency of a population-based mass tuberculosis screening intervention among persons with diabetes in Jiangsu Province, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 103–111 (2023).

Golub, J. E., Mohan, C. I., Comstock, G. W. & Chaisson, R. E. Active case finding of tuberculosis: historical perspective and future prospects. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 9, 1183–1203 (2005).

World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 2: systematic screening for tuberculosis disease. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022676 (2021).

Hu, Z. et al. Mass tuberculosis screening among the elderly: a population-based study in a well-confined, rural county in Eastern China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 1468–1475 (2023).

Luo, D. et al. Spatial spillover effect of environmental factors on the tuberculosis occurrence among the elderly: a surveillance analysis for nearly a dozen years in eastern China. BMC Public Health 24, 209 (2024).

Teo, A. K. J. et al. Tuberculosis in older adults: challenges and best practices in the Western Pacific Region. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 36, 100770 (2023).

Sossen, B. et al. The natural history of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 11, 367–379 (2023).

Coussens, A. et al. A new disease framework for tuberculosis to guide research towards improved care and prevention - an International Consensus for Early TB (ICE-TB). Lancet Respir. Med., 12, 484–498(2023).

Pai, M. Spectrum of latent tuberculosis—existing tests cannot resolve the underlying phenotypes. Nat., Rev., Microbiol. 8, 242 (2010).

Bobak, C. A. et al. Gene expression in cord blood and tuberculosis in early childhood: A nested case-control study in a South African birth cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, 438–449 (2023).

Esmail, H., Macpherson, L., Coussens, A. K. & Houben, R. M. G. J. Mind the gap–managing tuberculosis across the disease spectrum. EBioMedicine 78, 103928 (2022).

International Union Against Tuberculosis Committee on Prophylaxis Efficacy of various durations of isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis: five years of follow-up in the IUAT trial. Bull. World Health Organ. 60, 555–564 (1982).

Falk, A. & Fuchs, G. F. Prophylaxis with isoniazid in inactive tuberculosis: a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study XII. Chest 73, 44–48 (1978).

Zhang, H. et al. Tuberculosis preventive treatment among individuals with inactive tuberculosis suggested by untreated radiographic abnormalities: a community-based randomized controlled trial. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 12, e2169195 (2023).

Gao, L. et al. Short-course regimens of rifapentine plus isoniazid to treat latent tuberculosis infection in older Chinese patients: a randomised controlled study. Eur. Respir. J. 52, 1801470 (2018).

Xin, H. et al. Protective efficacy of 6-week regimen for latent tuberculosis infection treatment in rural China: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Eur. Respir. J. 60, 2102359 (2022).

Imperial, M. Z. et al. A patient-level pooled analysis of treatment-shortening regimens for drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 24, 1708–1715 (2018).

Nation Health and Family Planning Commission of the people’s Republic of China. WS 288-2017 Diagnosis for Pulmonary Tuberculosis. (Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2017).

Huynh, G. H. et al. Tuberculosis control strategies to reach the 2035 global targets in China: the role of changing demographics and reactivation disease. BMC Med. 13, 88 (2015).

Zhu, P. et al. Effect of active screening of pulmonary tuberculosis in the elderly in rural area in Quzhou, Zhejiang. Dis. Surveill. 38, 196–200 (2023).

National Clinical Medical Research Center for infectious diseases, Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital, Editorial Committee of Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis Prevention Expert consensus on TB activity judgment criteria and clinical application. Chin. J. Antituberc. 42, 301–307 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Trends and predictions of tuberculosis notification in mainland China during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Infect. 87, e100–e103 (2023).

Chinese Society of infectious disease of Chinese Society of Radiology Expert consensus on Imaging diagnosis of hierarchical diagnosis and treatment for tuberculosis. Electron. J. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3, 118–127 (2018).

Ko, Y. et al. Correlation of microbiological yield with radiographic activity on chest computed tomography in cases of suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Plos One 13, e0201748 (2018).

Cheng, S., Zhou, L. & Zhou, X. Expert consensus on diagnosis and prevention of inactive pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 2, 197–201 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Glycemic trajectories and treatment outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis: a prospective study in Eastern China. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 204, 347–356 (2021).

You, N. et al. A risk score for prediction of poor treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients with diagnosed diabetes mellitus from eastern China. Sci. Rep. 11, 11219 (2021).

Peduzzi, P., Concato, J., Feinstein, A. R. & Holford, T. R. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards regression analysis. II. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 48, 1503–1510 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We thank the medical staff and community workers in Quzhou who participated in the active screening. The research was supported by the “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang (grant number 2025C01134) (B.C.), the People’s Government of Quzhou provided special funds for private practical affairs (grant number 202013) (P.Z.), the National-Zhejiang Health Commission Major S&T Project (grant number WKJ-ZJ-2118) (B.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z., J.J., B.C. and L.M. designed the study. P.Z. wrote the initial manuscript draft. X.C., L.M., B.C. and J.J. modified subsequent versions of the manuscript. J.P. and X.H. performed the statistical analysis with input from P.Z., X.C., B.C. and L.M. X.C., J.P., X.H., P.Z., B.C. and L.M. made tables and figures. W.W1., X.H., K.L., W.W2. and X.C. performed the investigation and collected data. P.Z., X.Q. and X.H. were responsible for quality control of the baseline investigation at the study sites. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Robert Wilkinson, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, P., Chen, X., Pan, J. et al. Prognostic value of an abnormal chest X-ray result in predicting the development of tuberculosis. Nat Commun 16, 9866 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64834-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64834-9