Abstract

Astilbe chinensis, a perennial ornamental plant in the Saxifragaceae family, is recognized for its medicinal properties due to its diverse secondary metabolites. Here, we generate a chromosome-level genome assembly of A. chinensis. Our analysis provides compelling evidence that A. chinensis experienced a whole-genome triplication event, which preceded the diversification of the Saxifragaceae family. Furthermore, we identify a biosynthetic gene cluster that includes nine terpene synthase (TPS) genes. Among these, the gene AcTPS2 encodes a eudesma-5,7-diene synthase, and the product is confirmed using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. A synteny analysis of this gene cluster across various representative plant species reveals variations in the number, sequence, and function of TPS genes, indicating that neo-functionalization of these TPS genes likely occurred after speciation. Collectively, the genome sequence of A. chinensis lays the foundation for genetic and evolutionary studies of the Saxifragaceae family and provides insights into terpene synthases discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The horticultural plant Astilbe chinensis (Saxifragaceae family) is renowned for its vibrant and diverse flower colors. In addition to its ornamental value, it is also recognized as a medicinal plant with various therapeutic properties, owing to its richness in secondary metabolites like astilbin, bergenin, flavonoids, triterpenes, and phytosterols1,2. The Saxifragaceae family, comprising approximately 640 species and 33 genera, exhibits remarkable ecological diversity—ranging from herbaceous plants to shrubs, trees, aquatic species, and even saxicolous plants3,4. Phylogenetically, this family represents a crucial evolutionary node between Dillenianae and Rosids, though the exact relationships remain unresolved5. Despite its significance, genomic studies of Saxifragaceae are limited, with only four species sequenced to date6,7,8,9. Therefore, the A. chinensis genome sequence will help clarify Saxifragales phylogeny and provide a crucial genomic resource for this understudied plant family.

As the number of sequenced plant genomes continues to grow, we are gaining substantial insights into the genetic blueprints of these organisms. Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) are being increasingly identified within plant genomes, with many implicated in terpenoid biosynthetic pathways10. Terpenes and their oxygenated derivatives, terpenoids, represent one of the largest and most structurally diverse classes of plant metabolites, serving critical ecological functions11. In terpenoid biosynthesis, terpene synthases (TPS) exhibit remarkable catalytic versatility, enabling the formation of thousands of distinct compounds12,13. Although the protein structures and catalytic mechanisms of several plant TPS enzymes have been characterized, predicting their functions and products remains challenging due to extensive variation within their substrate-binding pockets14. Therefore, exploring genetic resources from understudied plants such as A. chinensis offers opportunities to discover TPS genes or gene clusters. Investigating TPS diversity across different plant lineages can further clarify their contributions to species-specific metabolic profiles and ecological adaptations.

Although terpene BGCs are commonly reported for triterpenoids and diterpenoids biosynthesis in plants, such as avenacins, cucurbitacins, momilactones, and casbene, functional BGCs involved in monoterpene and sesquiterpene biosynthesis remain relatively rare15. Genomic studies, however, reveal that many TPS genes are organized in tandem arrays, suggesting these regions may serve as evolutionary hotspots for metabolic diversification16,17. For example, 13 of the 32 TPS genes in Arabidopsis thaliana are arranged in tandem18, and three tandem TPS genes are located on rice chromosome 8: Os080 (Os08g07080), Os100 (Os08g07100), and Os120 (Os08g07120). While Os080 is non-functional, Os100 and Os120 encode sesquiterpene synthases with divergent activities16. Nevertheless, the evolutionary mechanisms underlying the formation of terpene BGCs, including gene duplication, sequence variation, and functional divergence, remain poorly understood.

In previous work, using transcriptome data from A. chinensis, we elucidated the biosynthetic pathways of the flavonoid compounds neodiosmin and salidroside19,20. In the present study, the complete genome sequence of A. chinensis provides a foundation for genetic and evolutionary research in the Saxifragaceae family. Furthermore, the identification of a terpene BGC in this genome has led to the discovery of a eudesma-5,7-diene synthase, and genomic collinearity analysis has unveiled the potential formation process of the terpene gene cluster during plant evolution.

Results

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation of A. chinensis

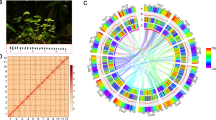

The genome of A. chinensis (2n = 2x = 14)21 was sequenced and assembled using a combination of Nanopore long reads, Illumina short reads, and Hi-C data (Fig. 1A, Table 1, Supplementary Data 1, and Supplementary Methods 1 and 2). An initial genome survey estimated the genome size to be 314.7 Mb, with a high heterozygosity rate of 3.9% (Supplementary Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 1). The final genome assembly achieved a total length of 335.3 Mb, consisting of 7 chromosome-level scaffolds with a N50 size of 42.1 Mb (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. 2, and Supplementary Table 2), which is consistent with the estimated genome size of 366.9 Mb obtained through flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 3). Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs analysis revealed that 98.0% of universal single-copy genes were fully annotated using the eudicots_odb10 database (Supplementary Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table 2). The assembly exhibited excellent continuity, with only 10.5 Kb of total genomic gap (Supplementary Fig. 4). Furthermore, telomere integrity analysis identified 13 out of 14 telomeric structures (92.9%) (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicating high quality and completeness of the assembly. The LTR Assembly Index index score for A. chinensis was 20.5, comparable to those of Medicago sativa (22.3) and Echinochloa colona (22.5), supporting the qualification of this assembly as a reference genome22,23,24.

A Morphology of A. chinensis. B Distribution of A. chinensis genomic features. The linking lines in the circle represent synteny of paralogous sequences in the genome. Outermost to innermost tracks indicate the (1) pseudochromosomes, (2) GC content density, (3) gene density, (4) tandem or proximal duplicated (TD/PD) genes density, (5) TE density, (6) Copia LTR density, (7) Gypsy LTR density, (8) DNA TE density, and (9) LINE TE density.

Through a combination of de novo annotation, homology-based, and transcriptome-assisted gene identification, a total of 21,436 protein-coding genes were annotated (Supplementary Table 3). Functional annotation indicated that 97.69% of these genes had matches in at least one public database, including NR (94.37%), Swissprot (75.14%), PFAM (80.08%), KEGG (43.81%), TrEMBL (94.48%), and Interpro (96.20%) (Supplementary Fig. 5A and Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, we annotated 664 tRNAs, 401 rRNAs (including 211 8S, 94 18S, and 96 28S RNAs), and 589 other non-coding RNAs (114 miRNAs and 475 snRNAs) in the assembled A. chinensis genome (Supplementary Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table 5, and Supplementary Method 3).

Using de novo and homology-based approaches, we identified approximately 150.01 Mb transposable elements (TEs), accounting for 44.74% of the assembled A. chinensis genome (Supplementary Fig. 5C, Supplementary Data 2, and Supplementary Method 4). Long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) constituted the largest proportion, covering 15.25% (approximately 51.13 Mb) of the total genome. Ty1/Copia and Ty3/Gypsy elements were the two main classes of LTR-RTs, accounting for 6.41% and 7.11% of the genome, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). We further compared TE content across other Saxifragales species and the closely related Vitaceae species, Vitis vinifera. TE proportions were 53.01% in V. vinifera, 37.70% in Kalanchoe fedtschenkoi, 40.04% in Kalanchoe laxiflora, and 51.47% in Rhodiola crenulata, suggesting relatively conserved TE proportions across these species without significant divergence (Supplementary Data 2).

Comparative genomic analysis revealed a whole-genome triplication (γ-WGT) event in A. chinensis

To identify whole-genome duplication (WGD) events in A. chinensis, we performed a genome-wide collinearity analysis using Amborella trichopoda and V. vinifera as references. The A. trichopoda genome serves as a unique reference, being the sister lineage to all other living angiosperms, while the V. vinifera genome represents the ancestral eudicot karyotype25,26. Comparative genomic analysis between A. chinensis and A. trichopoda or V. vinifera revealed syntenic depth ratios of 3:1 (A. chinensis: A. trichopoda) and 3:3 (A. chinensis: V. vinifera), respectively (Fig. 2A, B and Supplementary Fig. 7). Consistently, further analysis of the homologous gene of AmTrH2.05G047500.1 from A. trichopoda identified three homologous genes in both A. chinensis and V. vinifera, confirming the presence of 1:3:3 orthologous regions (A. trichopoda: V. vinifera: A. chinensis) in the comparisons (Fig. 2C). It had been established that γ-WGT event occurred in the V. vinifera, whereas no evidence supports lineage-specific polyploidy events in A. trichopoda. Thus, it was inferred that A. chinensis was similar to V. vinifera in that they underwent only the γ-WGT event without additional whole-genome replication events.

Syntenic dot plots between the A. chinensis genome and the A. trichopoda genome (A) and the V. vinifera genome (B). Each dot represents a homologous gene pair retained in a synteny block. C Macrosynteny patterns between A. chinensis, A. trichopoda, and V. vinifera. Matching gene pairs are displayed as connecting shades and highlighted by one syntenic set shown in color. D Chronogram shows divergence times and genome duplications in Superasterids and Superrosids with node age and the 95% confidence intervals labeled. Resolved polyploidization events are shown with blue (duplications) and red (triplications) translucent dots. Pie charts show the proportions of gene families that underwent expansion or contraction. E Ks age distributions for paralogues found in collinear regions (anchor pairs) of A. chinensis and V. vinifera and for orthologues between A. chinensis and V. vinifera. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To elucidate the phylogenetic relationship of A. chinensis among angiosperms, we constructed a phylogenetic tree of 291 low-copy ortholog sets from 14 species across Malvids, Fabids, Saxifragales, Vitales, and Lamiids (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Method 5). Both merged and concatenated methods yielded an identical and highly supported topology, placing A. chinensis as a sister group to other Saxifraga plants within Saxifragales, with Saxifragales forming a sister clade to other Rosids (Vitales, Fabids, and Malvids) within the Superrosids (Supplementary Fig. 8). Predicted gene models for the 15 species clustered to 24,884 orthogroups, among which 756 were expanded and 5123 were contracted in A. chinensis (Fig. 2D).

To further investigate the evolutionary history of the Saxifragales, we estimated intragenomic and interspecific homolog Ks (synonymous substitutions per site) distributions. A. chinensis paralogues showed a signature peak Ks value at approximately 1.35, similar to V. vinifera at 1.25 (Fig. 2E). Analysis of Ks distribution across 14 representative plant species confirmed that all underwent a γ-WGT event around 122–164 million years ago, which aligns with previous reports27,28. In contrast to some plants, such as Gossypium hirsutum, A. thaliana, and other Saxifragales members, which experienced one or two additional WGD events after the γ-WGT event, A. chinensis exhibited no further WGD events (Fig. 2D and Supplementary Fig. 9). Molecular dating analysis suggested that A. chinensis diverged from the other Saxifragales species approximately 86.18–110.51 Mya, following the divergence between Saxifragales and Vitales around 105.17–120.05 Mya (Fig. 2D).

Gene duplication analysis identified a terpene biosynthetic gene cluster

Gene duplication, by generating redundant gene copies and creating genetic novelty in organisms, serves as a crucial evolutionary force driving species formation, adaptation, and diversification29. We thus focused on characterizing duplicated genes in A. chinensis. By identifying distinct duplication modes of gene pairs30, we detected a total of 16,062 duplicated genes, which were categorized into five types based on their duplication origin: 3894 from WGDs, 1963 from tandem duplications (TD), 892 from proximal duplications (PD), 6099 from transposed duplications (TRD), and 5097 from dispersed duplications (DSD) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 7, and Supplementary Method 6). We further compared the Ka/Ks ratio (ratio of the non-synonymous to synonymous substitution) and Ks distribution across these duplication modes. Among these modes, TD and PD gene pairs exhibited higher Ka/Ks ratios and smaller Ks values, indicating an ongoing duplication process for TD and PD, alongside more rapid sequence divergence and stronger positive selection (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table 8).

A Gene upset plot of gene duplication types. WGD whole-genome duplications, TRD transposed duplications, TD tandem duplications, PD proximal duplications, DSD dispersed duplications. B The Ka/Ks ratio distributions and the Ks ratio distributions of gene pairs derived from different modes of duplication. Gaussian kernel estimates of Ka/Ks and Ks for different duplicated groups are shown as violins. The box center line represents the median, the box edges indicate the first and third quartiles, and the whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with two-tailed Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) multiple comparison test (sample sizes: DSD = 6917, PD = 440, TD = 1127, TRD = 4464, WGD = 2212). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by different lowercase letters. Exact P-values are available in Supplementary Table 8. C Venn diagram illustrates the potential logical relations between members of expanded gene families and duplication modes. EGs, expansion genes. D Terpene synthase gene cluster in A. chinensis genome. Genes are represented with arrows. The function of each gene product is indicated by colors: red, terpene synthase (TPS); blue, cytochrome P450; green, truncated cytochrome P450; orange, truncated terpene synthase; purple, cis-prenyltransferase (cis-PT); magenta, methyltransferase (MT); grey, protein of other types. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We identified 3097 expanded genes in 756 orthogroups (Fig. 2D). Of these expanded genes, 617 and 316 overlapped with TD or PD genes, respectively (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Table 7). We performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis on these overlapping genes, which showed enrichment in key GO terms related to “terpene synthase activity”, “enzyme activity”, and “binding” (Supplementary Fig. 10A). For Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, the genes exhibited enrichment in pathways including “plant self-defense”, “plant adaptation”, “cytochrome P450”, and “sesquiterpenoid and triterpenoid biosynthesis” (Supplementary Fig. 10B). In summary, newly formed tandem and PD have significantly contributed to gene family expansion in A. chinensis, playing crucial roles in plant metabolic pathways, particularly the biosynthesis of terpenoids.

To systematically explore the expanded and duplicated genes associated with secondary metabolism in the A. chinensis genome, we employed PlantiSMASH for analysis31. A total of 46 biosynthetic gene clusters were identified, encompassing those involved in the biosynthesis of saccharides, terpenes, alkaloids, polyketides, and lignans (Supplementary Data 3). One significant gene cluster spans approximately 469.8 Kb and comprises multiple genes encoding TPS, cytochrome P450, cis-prenyltransferase (cis-PT), and methyltransferase (MT) (Fig. 3D). It is worth mentioning that this gene cluster contains nine TPS genes, eight of which are expansion genes and categorized as either TD or PD genes, with the exception of AcTPS1 (Supplementary Table 9). TPS enzymes are vital for terpenoid skeleton biosynthesis in plants and are present in almost all plant species, including lower plants32.

Identification of an eudesma-5,7-diene synthase from the terpene biosynthetic gene cluster

Terpenes and their derived terpenoids represent the largest class of specialized metabolites in plants, and many terpene biosynthesis pathways are often associated with biosynthetic gene clusters33. To identify the TPS genes from A. chinensis, we screened the assembled gene models for those containing both the PF01397 and PF03936 motifs, corresponding to the N- and C- terminal domains of TPS enzymes. A total of 38 genes were identified, with nine TPS genes within this cluster belonging to the TPS-a subfamily and forming three subclades (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Method 7). By analysing the selection pressure of TPS genes during evolution, we found the eight TPS genes within the TPS gene cluster showed a sign of positive selection among the TPS-a branch (Supplementary Table 10). These findings suggest that this TPS gene cluster may play a significant role in plant adaptive evolution, as the TPS genes likely undergone neofunctionalization.

A Phylogenetic analysis showcasing the classification and relationship of terpene synthase (TPS) genes in A. chinensis. Genes marked in red are those found within the TPS biosynthesis gene cluster identified in this study. B Expression levels of nine TPS genes in seven tissues. C GC chromatograms of extracts from the yeast cultures expressing AcTPS2 and AcTPS5. Genes were co-expressed with ERG20 (yeast FPPS, NP_012368). Products are identified as: F1, germacrene C; F2, β-elemene; F4, α-selinene; F5, trans-nerolidol. “Empty vector” indicates a negative control. D Mass spectra comparison of products and the authorized standards. E The relative configuration, 1H–1H COSY, the key HMBC and NOESY correlations of eudesma-5,7-diene (F3). F LC chromatograms and mass spectra at a retention time of 9.37 min of the eudesma-5,7-diene standard and extracts from different tissues of A. chinensis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Transcriptome analysis of the TPS gene family revealed distinct expression patterns for different TPS genes, four of which exhibited high expression levels in the rhizomes and roots (Fig. 4B). Sequence analysis revealed these TPS genes share limited similarity with previously characterized TPSs, with the highest degree of similarity to LfTPS02 (AIO10965.1) from Liquidambar formosana in the NCBI database (58.08% identity). To characterize their catalytic activities, we successfully amplified and cloned four TPS genes—AcTPS1 (Asch_Chr1_01883.1), AcTPS2 (Asch_Chr1_01886.1), AcTPS5 (Asch_Chr1_01889.1), and AcTPS6 (Asch_Chr1_01911.1). Using a terpene precursor-supplied yeast JCR27 strain34,35, we co-expressed these genes with the yeast farnesyl diphosphate synthase gene (ERG20) and analyzed their sesquiterpene production.

AcTPS2 catalyzed the formation of five sesquiterpenes (F1–F5), while AcTPS5 generated four sesquiterpene compounds (F1–F4) (Fig. 4C). AcTPS6 was exclusively responsible for F5 biosynthesis (Supplementary Fig. 11). Additionally, AcTPS1 catalyzed the biosynthesis of three sesquiterpenes, specifically F2, F6, and F7 (Supplementary Fig. 11). Among them, F1, F2, F4, F5, F6, and F7 were identified as germacrene C (F1), β-elemene (F2), α-selinene (F4), trans-nerolidol (F5), β-caryophyllene (F6), and α-humulene (F7) through comparisons with standards, and F3 was initially identified as an unknown compound (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. 12). These sesquiterpene products were further validated via transient expression of the corresponding TPS genes in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Method 8).

Following large-scale fermentation and purification from yeast strain, we obtained 2.3 mg of F3, whose chemical structure was further elucidated by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (1H NMR and 13C NMR). Detailed comparison of spectra with δ-selinene, also named eudesma-4,6-diene (P2), revealed that they share the same structure (Supplementary Fig. 14)36. Inadvertently, we observed that the spectra of gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) fore-and-aft NMR were completely different, indicating that the product may be unstable in CDCl3 (Supplementary Fig. 15). We then tested and found that the compound remained stable for NMR without changes by using acetone-d6 and CH3OD as solvents (Supplementary Fig. 15). Ultimately, F3 was isolated as a pale yellow oil. Its molecular formula was determined to be C15H24 via high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR ESI–MS). Through extensive analysis of NMR spectra (1H NMR, 13C NMR, 1H–1H COSY, HMBC, and NOESY) and comparison with previously reported literature, F3 was eventually identified as eudesma-5,7-diene (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Figs. 16–18, and Supplementary Tables 11 and 12)37,38.

Eudesma-5,7-diene has previously been detected in only a few plants, including Vetiveria zizanioides, Croton eluteria, and Preissia quadrata38,39,40. To investigate the tissue-specific distribution of eudesma-5,7-diene in A. chinensis, extracts from rhizomes, leaves, stems, and roots were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS). Although no discernible absorption peaks were detected in root extracts at the retention time (RT) of 9.37 min, the other tissues showed targeted MS/MS fragmentation with characteristic fragment ions that matched authentic standards. These results indicate that eudesma-5,7-diene is specifically localized in the rhizomes, leaves, and stems (Fig. 4F).

We then purified the AcTPS2 protein from heterologous expression in Escherichia coli, and determined its optimal catalytic conditions in vitro. Assays with multiple substrates, including geranyl diphosphate (GPP), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), demonstrated that AcTPS2 exhibits strict specificity for FPP (Supplementary Figs. 19–21). Enzyme kinetic analyses revealed a substrate concentration-dependent activity profile, with maximal velocity (Vmax) of 0.323 nmol·h−1·μg−1 observed at 200 μM substrate (Supplementary Fig. 22). Michaelis–Menten parameters were quantified as follows: Km = 23.84 μM, Kcat = 0.323 min−1, and catalytic efficiency Kcat/Km = 0.0135 min−1·μM−1.

Gene duplication of terpene synthase genes in the biosynthetic gene cluster occurred subsequent to speciation

In a synteny analysis, this terpene gene cluster in A. chinensis demonstrated collinearity with that of various plant species (Supplementary Table 13). Both the upstream and downstream regions of the gene cluster showed sequence conservation, despite variations in TPS gene copy number. Specifically, within the corresponding genomic segments, Coffea canephora, Aquilaria sinensis, and Ipomoea triloba each contained two TPS genes, V. vinifera contained four TPS genes, and Sesamum indicum had six TPS genes, while A. thaliana completely lacked the corresponding region (Fig. 5A). Phylogenetic analysis of these TPS sequences revealed lineage-specific conservation, with TPS genes from the same species clustering together to form distinct subclades, except AcTPS1 (Fig. 5B).

A Comparison of the TPS biosynthetic gene clusters from six plant species with A. chinensis. Synteny between each species is shown with grey lines and TPS genes are marked with a red block. The genes marked with an asterisk have been functionally identified in vitro. B Phylogenetic tree of TPS genes found within TPS biosynthetic genes clusters identified in this study. C GC chromatograms of extracts from the yeast cultures expressing CcTPS2, ItTPS1, and SiTPS2. Genes were co-expressed with ERG20 (yeast FPPS, NP_012368). “Empty vector” indicates negative control. D Chemical structure of sesquiterpene compounds determined by GC chromatograms. Products were identified by comparison to standards or NIST17 library. E A proposed model for the evolutionary trajectory of the TPS gene cluster in plants. Genes annotated with an asterisk have undergone functional identification. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The functions of TPS from V. vinifera and Aquilaria sinensis have been characterized previously, with VvTPS2 mainly producing cubebol (F13) and δ-cadinene (F18), and AsTPS1 producing α-humulene (F7)41,42. To investigate functional variability among other TPS, we synthesized cDNAs of CcTPS2, ItTPS1, and SiTPS2 and performed functional characterization studies (Fig. 5C, D and Supplementary Fig. 11). CcTPS2 catalyzed the formation of six sesquiterpene products, including germacrene-D-4-ol (F15), germacradien-6-ol (F17), α-maaliene (F14), β-elemene (F2), β-selinene (F12), and one unknown compound. ItTPS1 produced seven sesquiterpene products, with cyperene (F8) as the major component. SiTPS2 exclusively produced a single product, pogostol (F16) (Supplementary Data 4). Overall, TPS genes in this gene cluster not only exhibit significant sequence divergence across different species but also produce markedly different arrays of products, suggesting substantial functional diversity.

Therefore, we propose that the initial divergence of plant TPS sequences likely took place between 89 and 125 Mya, during the process of angiosperm genome differentiation. Following this, the duplication of TPS genes happened subsequent to speciation, which ultimately led to the formation of the TPS biosynthesis gene cluster (Fig. 5E). These duplication events likely facilitated the expansion and further functional specialization of TPS genes, allowing plants to explore distinct ecological niches and adapt to environmental changes through the development of diverse secondary metabolites. This sequence of evolutionary events underscores the complexity and dynamism of plant secondary metabolism.

Discussion

Here, we conducted a chromosome-level genome sequencing of A. chinensis, an ornamental plant belonging to the Saxifragaceae family. This genomic resource not only sheds light on the plant’s evolutionary history and reveals its genetic diversity, but also uncovers genes involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis. The development of sequencing technology has led to the revelation of an increasing amount of information on plant genomes. For non-model plants, however, current genomic research primarily focuses on gene evolution and natural variation, with exploration and application of these genomic resources remaining very limited. The advancement of synthetic biology provides a good opportunity for the application of plant genomic resources, without being constrained by the unpredictability and complexity of plant growth and genetic transformation. Given the extensive plant genomic data already available in public databases, adopting this approach can accelerate the discovery of more valuable plant secondary metabolites.

Moreover, through the analysis of the A. chinensis genome, a terpene synthase gene cluster was discovered, and a eudesma-5,7-diene synthase was identified using a yeast chassis for heterologous expression. Eudesma-5,7-diene belongs to the eudesmane-type sesquiterpenoids, which are a class of natural compounds with a wide range of biological activities, especially prevalent in plants of the Asteraceae family, and are also important components of agarwood essential oil43. Eudesmane-type sesquiterpenoids exhibit diverse chemical structures and pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, antibacterial, and antiviral activities44. Eudesma-5,7-diene is relatively rare in nature; hence, research on its biological activity is very limited. Here, we utilize synthetic biology methods for heterologous expression, enabling large-scale fermentation and extraction from yeast, thus paving the way for determining its biological effects and pharmacological properties.

Despite the presence of genes encoding modification enzymes (e.g., AcCYPs, AcMT, and AcPT) within the cluster, our co-expression of AcTPS2 with these genes in both tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) and yeast failed to yield any detectable modified derivatives of its primary product, eudesma-5,7-diene (Supplementary Figs. 23–25). This unexpected result suggests that this locus may not constitute a complete, autonomous biosynthetic pathway. The maturation of the terpene skeleton into a final natural product may require the assistance of auxiliary enzymes encoded elsewhere in the genome. Alternatively, the cluster’s modification enzymes might target alternative products of AcTPS2. These possibilities necessitate further experimental validation to determine the precise functional context of this putative biosynthetic cluster.

Previous studies have demonstrated that TPS gene sequences are mostly lineage-specific in angiosperms. Our evolutionary model (Fig. 5E) traces their origin to a common ancestor of seven analyzed species, followed by lineage-specific duplications and functional divergence. While A. thaliana lost all TPS genes through pseudogenization events, the six other species retained expanded TPS gene families via repeated duplication. Terpenoid compounds are crucial for the environmental adaptability of plants and their interactions with other organisms. Functional characterization demonstrated that cluster-encoded TPS enzymes exhibit distinct catalytic specificities, with detectable signatures of positive selection, suggesting their metabolic diversification contributed to ecological adaptation.

The plant kingdom offers a wealth of genomic resources, with a multitude of TPS genes exhibiting substantial functional diversity. However, the intricate links between the protein sequences, structural conformations, and specific catalytic products of these TPS genes remain largely enigmatic. This complexity indicates a rich potential for further research into the functions of these genes and the biochemical processes they mediate. In summary, we underscore the feasibility of integrating genomic data with evolutionary gene functional analysis and synthetic biology approaches. This integration can unlock the medicinal and ecological potential of plant secondary metabolites, ultimately contributing to a deeper understanding and application of plant metabolic pathways across various fields.

Methods

Genome sequencing and assembly

A. chinensis was purchased from Tianjin Lanxiu Gardening Co., Ltd (Tianjin, China), and fresh leaves were collected for subsequent experiments. For genomic sequencing, high molecular weight genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaf tissue and subjected to long-read sequencing on the Oxford Nanopore PromethION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK), short-read sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and Hi-C sequencing on the BGI MGISEQ platform (MGI Tech, Shenzhen, China). Separately, flow cytometry analysis was performed on fresh leaf samples to estimate the genome size.

The A. chinensis genome was assembled de novo using Canu (v2.1.1)45 based on clean Oxford Nanopore reads. To improve assembly accuracy, the contigs were refined sequentially using Racon (v1.4.17)46 for initial polishing, NextPolish (v1.4.1)47 for short-read-based error correction, and HaploMerger2 (Release 20180603)48 for haplotype merging, all with default parameters. The scaffolds were further anchored into chromosome-level assemblies using Hi-C data via Juicer (v1.6)49 and 3D-DNA (v180922)50. Detailed methodology is provided in the Supplementary Methods 1 and 2.

Functional characterization of sesquiterpene synthase

The open reading frames of AcTPS1, AcTPS2, AcTPS5, and AcTPS6 were cloned from the rhizome cDNA and introduced into the yeast expression vector, as described previously34,35. Primers used for PCR amplification were synthesized by GeneCreate Biological Engineering Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China), and their sequences are detailed in Supplementary Table 14. A comprehensive list of the plasmids and strains used is provided in Supplementary Table 15. The codon-optimized sequences of CcTPS2, ItTPS1, and SiTPS2 were synthesized by GenScript Biotech Corporation (Nanjing, China). Expression plasmids were individually transformed into JCR27 strain. The yeast clone was precultured in the SC medium with uracil dropout supplemented with 1% glucose at 28 °C for 48 h at 220 × g. Then the culture was inoculated into YPD medium with 1% glucose and 1% galactose, covered with isopropyl myristate (IPM) at 28 °C for 72 h at 250 × g. The organic phase from the biphasic culture was harvested and diluted with hexane for GC-MS analysis.

The samples of sesquiterpenes profile were analyzed by GC-MS using GCMS-TQ8040 mass spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with a TR-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The GC oven temperature was initially set at 80 °C for 1 min. The temperature was then ramped up to 280 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 and sustained for an additional 7 min. Terpenoid compounds were characterized within a mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) range of 45–500. The compounds were identified by comparison with our local library of standards, GroupLiu 6.051.

Isolation and structural identification of eudesma-5,7-diene

The IPM was collected from a 14 L culture medium to centrifuge for 50 min at 8000 × g after fermentation. Subsequently, the product was separated through vacuum distillation, and the residual IPM was removed by silica gel column chromatography (CC, 500–800 mesh) with petroleum ether as the eluent to yield 2.3 mg of eudesma-5,7-diene. The structure and purity of the product were determined by NMR and GC-MS analysis35,52. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra data were recorded using a Bruker AVANCE NEO 600 spectrometer (151 MHz or 600 MHz) at 298 K.

Extraction and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis of the extracts from A. chinensis tissues

A total of 5 g of tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen for 5 min and then ground into powder. An adequate amount of ethyl acetate was added by ultrasonic extraction for 40 min. The extract was centrifuged to obtain the supernatant, and the excess solvent was removed using a freeze-dryer. The extract was then re-dissolved in methanol for LC-MS analysis. For LC-MS analysis, an LTQ-Orbitrap-XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used, coupled with an Accela ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatograph and a TSQ Quantum Ultra triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI source. Solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) served as mobile phases. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min and the injection volume was 1 μL. The gradient elution procedure was as follows: 10% B for 1 min; 10–100% B for 10 min; 100% B for 5 min. The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C. Mass spectrometry was performed in positive ion mode as follows: vaporizer temperature, 400 °C; source voltage, 3 kV; sheath gas, 60 au; auxiliary gas, 20 au; capillary temperature, 380 °C; capillary voltage, 6 V; tube lens, 45 V, with a scan of the mass range: 100–800 Da. The compounds were analyzed using the QualBrowser feature of Xcalibur software (version 2.1.0.1140).

Recombinant protein expression in E. coli and purification

The target TPS gene was cloned and constructed into the pET28a(+) vector with a C-terminal 6 × His tag using homologous recombination (Supplementary Tables 14 and 15). The recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) cells for heterologous expression. The suspension was sonicated to obtain soluble cellular components. The supernatant was loaded on a Ni-NTA affinity column (GenScript Biotech Corporation, Nanjing, China) and eluted with an imidazole gradient. The eluted protein was further concentrated using a 30 kDa Millipore Ultrafiltration centrifugal filter (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

Enzymatic assays

A total of 15 µg purified protein was incubated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM DTT, 12.5% glycerol, 0.1% Tween 20, 1 mM sodium ascorbate, and varying substrates GPP, FPP, and GGPP (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 30 °C for 1 h. An equal volume of ethyl acetate was then added to the reaction mixture for extraction. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Enzymatic kinetic parameters were calculated using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.0).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All raw sequence and genome assembly data have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn) with BioProject accession PRJCA027049. Functional characterized TPS sequences have deposited in the GenBase; the accession numbers are C_AA107105.1 (AcTPS1) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107105.1]; C_AA107106.1 (AcTPS2) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107106.1]; C_AA107107.1 (AcTPS5) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107107.1]; C_AA107108.1 (AcTPS6) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107108.1]; C_AA107109.1 (CcTPS2) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107109.1]; C_AA107110.1 (ItTPS1) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107110.1]; C_AA107111.1 (SiTPS2) [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/genbase/search/gb/C_AA107111.1]. Additional data, including genome assemblies and annotations, GC-MS raw data, LC-MS raw data, and NMR raw data can be found in the Figshare database [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28748501]. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sun, H. X., Ye, Y. P. & Yang, K. Studies on the chemical constituents in radix Astilbes chinensis. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 27, 751–754 (2002).

Xue, Y., Xu, X. M., Yan, J. F., Deng, W. L. & Liao, X. Chemical constituents from Astilbe chinensis. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 13, 188–191 (2011).

Deng, J. -b. et al. Phylogeny, divergence times, and historical biogeography of the angiosperm family Saxifragaceae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 83, 86–98 (2015).

Tkach, N. et al. Molecular phylogenetics, morphology and a revised classification of the complex genus Saxifraga (Saxifragaceae). Taxon 64, 1159–1187 (2015).

Zeng, L. et al. Resolution of deep eudicot phylogeny and their temporal diversification using nuclear genes from transcriptomic and genomic datasets. N. Phytol. 214, 1338–1354 (2017).

Liu, X.-D. et al. A Chromosome-level genome assembly of the alpine medicinal plant Bergenia purpurascens (Saxifragaceae). Sci. Data 12, 121 (2025).

Yang, Y.-X. et al. The chromosome-level genome assembly of an endangered herb Bergenia scopulosa provides insights into local adaptation and genomic vulnerability under climate change. GigaScience 13, giae091 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. The Chrysosplenium sinicum genome provides insights into adaptive evolution of shade plants. Commun. Biol. 7, 1004 (2024).

Liu, L. et al. Phylogenomic and syntenic data demonstrate complex evolutionary processes in early radiation of the rosids. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 23, 1673–1688 (2023).

Bryson, A. E. et al. Uncovering a miltiradiene biosynthetic gene cluster in the Lamiaceae reveals a dynamic evolutionary trajectory. Nat. Commun. 14, 343 (2023).

Pichersky, E. & Raguso, R. A. Why do plants produce so many terpenoid compounds?. N. Phytol. 220, 692–702 (2018).

Nagegowda, D. A. & Gupta, P. Advances in biosynthesis, regulation, and metabolic engineering of plant specialized terpenoids. Plant Sci. 294, 110457 (2020).

Gao, Y., Honzatko, R. B. & Peters, R. J. Terpenoid synthase structures: a so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 1153–1175 (2012).

Zhou, F. & Pichersky, E. More is better: the diversity of terpene metabolism in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 55, 1–10 (2020).

Zhan, C. et al. Plant metabolic gene clusters in the multi-omics era. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 981–1001 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Combinatorial evolution of a terpene synthase gene cluster explains terpene variations in Oryza. Plant Physiol. 182, 480–492 (2020).

Qiao, D. et al. A monoterpene synthase gene cluster of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) potentially involved in constitutive and herbivore-induced terpene formation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 184, 1–13 (2022).

Aubourg, S., Lecharny, A. & Bohlmann, J. Genomic analysis of the terpenoid synthase (AtTPS) gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Genet. Genomics 267, 730–745 (2002).

Chang, X. et al. Identification and characterization of glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of neodiosmin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 4348–4357 (2024).

Yao, Y. et al. Structure-based virtual screening aids the identification of glycosyltransferases in the biosynthesis of salidroside. Plant Biotechnol. J. 23, 1725–1735 (2025).

Rice, A. et al. The Chromosome Counts Database (CCDB) – a community resource of plant chromosome numbers. N. Phytol. 206, 19–26 (2015).

Ou, S., Chen, J. & Jiang, N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI). Nucleic Acids Res. 46, e126 (2018).

Shen, C. et al. The chromosome-level genome sequence of the autotetraploid alfalfa and resequencing of core germplasms provide genomic resources for alfalfa research. Mol. Plant. 13, 1250–1261 (2020).

Wu, D. et al. Genomic insights into the evolution of Echinochloa species as weed and orphan crop. Nat. Commun. 13, 689 (2022).

Project, A. G. et al. The Amborella genome and the evolution of flowering plants. Science 342, 1241089 (2013).

Zhou, Y., Massonnet, M., Sanjak, J. S., Cantu, D. & Gaut, B. S. Evolutionary genomics of grape (Vitis vinifera ssp. vinifera) domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11715–11720 (2017).

Badouin, H. et al. The sunflower genome provides insights into oil metabolism, flowering and Asterid evolution. Nature 546, 148–152 (2017).

Jiao, Y. et al. Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature 473, 97–100 (2011).

Panchy, N., Lehti-Shiu, M. & Shiu, S. H. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 2294–2316 (2016).

Yang, F. S. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of a parent species of widely cultivated azaleas. Nat. Commun. 11, 5269 (2020).

Kautsar, S. A., Suarez Duran, H. G., Blin, K., Osbourn, A. & Medema, M. H. plantiSMASH: automated identification, annotation and expression analysis of plant biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W55–W63 (2017).

Chen, F., Tholl, D., Bohlmann, J. & Pichersky, E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: a mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant J. 66, 212–229 (2011).

Tholl, D. Terpene synthases and the regulation, diversity and biological roles of terpene metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 297–304 (2006).

Deng, X. et al. Systematic identification of Ocimum sanctum sesquiterpenoid synthases and (−)-eremophilene overproduction in engineered yeast. Metab. Eng. 69, 122–133 (2022).

Deng, X. et al. Complete pathway elucidation and heterologous reconstitution of (+)-nootkatone biosynthesis from Alpinia oxyphylla. N. Phytol. 241, 779–792 (2024).

Pai¯s, M., Fontaine, C., Lauren, D., La Barre, S. & Guittet, E. Stylotelline, a new sesquiterpene isocyanide from the spongeStylotella sp. application of 2D-NMR in structure determination. Tetrahedron Lett. 28, 1409–1412 (1987).

Lago, J. H., Brochini, C. B. & Roque, N. F. Terpenoids from Guarea guidonia. Phytochemistry 60, 333–338 (2002).

Weyerstahl, P., Marschall, H., Splittgerber, U., Wolf, D. & Surburg, H. Constituents of Haitian vetiver oil. Flavour Frag. J. 15, 395–412 (2000).

Hagedorn, M. L. & Brown, S. M. The constituents of cascarilla oil (croton eluteria bennett). Flavour Frag. J. 6, 193–204 (1991).

König, W. A. et al. The sesquiterpene constituents of the liverwort Preissia quadrata. Phytochemistry 43, 629–633 (1996).

Martin, D. M. et al. Functional annotation, genome organization and phylogeny of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera) terpene synthase gene family based on genome assembly, FLcDNA cloning, and enzyme assays. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 226 (2010).

Ran, J. et al. Identification of sesquiterpene synthase genes in the genome of Aquilaria sinensis and characterization of an α-humulene synthase. J. For. Res. 34, 1117–1131 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Chemical composition and potential properties in mental illness (anxiety, depression and insomnia) of agarwood essential oil: a review. Molecules 27, 4528 (2022).

Wu, Q. X., Shi, Y. P. & Jia, Z. J. Eudesmane sesquiterpenoids from the Asteraceae family. Nat. Prod. Rep. 23, 699–734 (2006).

Koren, S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736 (2017).

Vaser, R., Sovic, I., Nagarajan, N. & Sikic, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Hu, J., Fan, J., Sun, Z. & Liu, S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics 36, 2253–2255 (2020).

Huang, S., Kang, M. & Xu, A. HaploMerger2: rebuilding both haploid sub-assemblies from high-heterozygosity diploid genome assembly. Bioinformatics 33, 2577–2579 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Zhi, Y. et al. Gene-directed in vitro mining uncovers the insect-repellent constituent from mugwort (Artemisia argyi). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 30883–30892 (2024).

Ye, Z. et al. Coupling cell growth and biochemical pathway induction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of (+)-valencene and its chemical conversion to (+)-nootkatone. Metab. Eng. 72, 107–115 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFA0912100) to Li Lu. The numerical calculations in this paper have been done on the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of Wuhan University. We extend our sincere gratitude to Professor Ying-Xiong Qiu from the Wuhan Botanical Garden for his valuable suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.C. analyzed the data. Y.Y., H.Z., J.H., A.G., Z.X., X.F., W.C., Y. Zhi, and Y. Zhang performed the experiments. F.C. and L.L. conceived the project, designed the experiments, and prepared the manuscript. Z.D. and T.L. discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jianquan Liu, Philipp Zerbe and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Yao, Y., Zhu, H. et al. A chromosome-level genome of Astilbe chinensis unveils the evolution of a terpene biosynthetic gene cluster. Nat Commun 16, 9869 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64842-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64842-9