Abstract

Spatial transcriptomics technologies are becoming increasingly high-resolution, enabling gene expression measurement at the subcellular level. Here, we present subcellular expression localization analysis (ELLA), a statistical framework for modeling subcellular mRNA localization and detecting spatially variable genes within cells. ELLA uses an over-dispersed nonhomogeneous Poisson process to model spatial count data with a unified cellular coordinate system to anchor diverse cellular morphologies, demonstrating effective type I error control and high power in simulations. In real data applications, ELLA identifies genes with distinct subcellular localization and associate these patterns to key mRNA characteristics: nuclear-enriched genes exhibit an abundance of long noncoding RNAs or protein-coding mRNAs, while cytoplasmic- or membrane-enriched genes frequently encode ribosomal proteins or contain signal peptides. ELLA also uncovers dynamic subcellular localization changes across the cell cycle. Overall, ELLA is a powerful, robust, and scalable tool for subcellular spatial expression analysis across high-resolution spatial transcriptomics platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spatial transcriptomics is a collection of new genomics technologies designed to measure gene expression within tissues while preserving spatial localization information. Recent technological advancements have substantially improved the spatial resolution of spatial transcriptomics, facilitating expression measurements at cellular and subcellular levels. Specifically, in situ RNA-sequencing techniques, such as ISS1, FISSEQ2, APEX-seq3, HybISS4, STARmap5, and Ex-seq6, achieve a spatial resolution under 1 μm, which is much smaller than the size of a typical cell. Recent high-throughput sequencing-based techniques, such as Slide-seq V27, Seq-Scope8, and Stereo-seq9, offer spatial resolutions in the range of 0.5–10 μm. In situ imaging techniques, such as MERFISH10, SeqFISH+11, MERSCOPE12, CosMx13, and 10X Xenium14, provide spatial resolutions as fine as 0.1–0.2 μm. Together, these high-resolution spatial transcriptomics technologies have enabled expression measurement at subcellular resolution, providing unprecedented opportunities to interrogate the intracellular localization and distribution of mRNAs within cells.

The intracellular localization and distribution of mRNAs are vital for cellular functions. They ensure the targeted delivery of mRNAs and facilitate localized protein synthesis, enabling precise regulation of gene expression within specific subcellular compartments. The spatial localization of mRNAs empowers cells to respond rapidly to local cues and signals, adapting effectively to changing environments and supporting specialized cellular functions15. For example, the localization of mRNAs encoding for β-actin at the leading edges of fibroblasts or the lamellipodia of myoblasts ensures localized protein synthesis of actin, supporting proper cell polarity and motility16. In addition, the spatial localization of mRNA contributes to cellular organization and differentiation, aiding in the establishment and maintenance of distinct cellular identities and functions, influencing asymmetric cell division and cell fate determination across various organisms. Classic examples of mRNA subcellular localization include the spatially localized expression of Oskar at the posterior end of the syncytial Drosophila embryo, which is essential for the development and assembly of the germ plasm in Drosophila, facilitating germ cell formation17. Another well-known example is Ash1 mRNA in S. cerevisiae, which localizes to the bud tip to establish asymmetry of HO endonuclease gene expression, which is important for mating type switching18. Given the importance of proper mRNA spatial localization, its misplacement often leads to detrimental effects and has been associated with multiple diseases17. For example, disruptions in axonal mRNA transport and localization contribute to neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease19. Therefore, characterizing the subcellular spatial localization pattern of mRNA—how mRNA molecules are localized and distributed spatially within cells, such as whether they are concentrated around the nucleus, enriched at the cell membrane, or diffusely scattered throughout the cytoplasm—is crucial for unraveling the complexity of cellular structure and function, as well as for elucidating the cellular mechanisms underlying disease etiology.

Despite the importance of characterizing the subcellular spatial localization pattern of mRNAs, only a few computational methods have been developed for this purpose, each with its own limitations. Specifically, Bento20 employs pre-trained random forest classifiers to categorize each gene into five pre-defined subcellular RNA localization patterns, while SPRAWL21 relies on four metrics to identify four pre-specified subcellular patterns. However, both methods are limited to imaging-based spatial transcriptomics data, where transcripts are represented as point clouds, but fail to leverage the vast amount of high-resolution spatial transcriptomics obtained from recent sequencing-based technologies, which often include multiple transcript counts at the same capture area or location. Additionally, they are constrained to detect genes with pre-defined localization patterns, thus limiting the discovery of any new spatial localization patterns. As a result, as will be shown here, both methods suffer from low statistical power in detecting a wide range of spatial localization patterns. Besides these major limitations, Bento requires nuclear boundary information, which may not be readily available in some spatial transcriptomics datasets. In addition, Bento is only applicable to analyzing a single cell and lacks the ability to borrow the spatial localization pattern shared across multiple cells. Conversely, SPRAWL is only applicable to analyzing multiple cells, not a single cell, and is unable to directly distinguish between enrichment and depletion in the pre-specified localization patterns due to the nature of its two-sided tests.

Here, we present subcellular expression localization analysis (ELLA), a statistical method for modeling the subcellular localization of mRNAs and detecting genes that display spatial variation within cells in high-resolution spatial transcriptomics. ELLA utilizes an over-dispersed nonhomogeneous Poisson process (NHPP) to model the spatial count data within cells, creates a unified cellular coordinate system to anchor diverse shapes and morphologies across cells, and relies on an expression intensity function to capture the subcellular spatial distribution of mRNAs. ELLA can be applied to an arbitrary number of cells and detect a wide variety of subcellular localization patterns across diverse spatial transcriptomic techniques, while producing effective control of type I error and yielding high statistical power. With a computationally efficient algorithm, ELLA is scalable to tens of thousands of genes across tens of thousands of cells. We illustrate the benefits of ELLA through comprehensive simulations and applications to four spatial transcriptomics datasets. In real data applications, ELLA not only identifies genes with distinct subcellular localization patterns but also reveals that these patterns are associated with unique mRNA characteristics. Specifically, genes enriched in the nucleus show an abundance of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and protein-coding mRNAs, often characterized by longer gene lengths. Conversely, genes containing signal recognition peptides, encoding ribosomal proteins (RPs), or involved in membrane-related activities such as synaptic transmission and G protein-coupled receptor activities, tend to be enriched in the cytoplasm or near the cellular membrane. Moreover, genes exhibit dynamic subcellular localization during the cell cycle, with some showing decreased nuclear enrichment in the G1 phase, while others maintain their patterns of enrichment regardless of cell cycle phases.

Results

Method overview

ELLA is described in “Methods,” with its technical details provided in Supplementary Notes and method schematic displayed in Fig. 1a. Briefly, ELLA is a statistical method for modeling the subcellular localization of mRNAs and detecting spatially variable genes with subcellular spatial expression patterns in high-resolution spatial transcriptomics. ELLA examines one gene at a time, relies on an over-dispersed NHPP to capture the spatial distribution of expression measurements within cells, creates a unified cellular coordinate system by defining a cellular radius in each cell that points from the center of the nucleus towards the cellular boundary, and computes a P value to capture any subcellular expression patterns observed along the cellular radius. ELLA is capable of borrowing information across cells through a joint likelihood framework to substantially improve detection power, while taking advantage of multiple intensity kernel functions to capture the distinct subcellular expression patterns that may be encountered in various biological settings to ensure robust performance. In addition, ELLA relies on a fast-binning algorithm for approximate position computation and leverages policy gradient optimization for scalable inference. As a result, ELLA is computationally efficient and is easily scalable to tens of thousands of genes measured in tens of thousands of cells. ELLA is implemented in Python, freely accessible from https://xiangzhou.github.io/software/.

a ELLA is a method for modeling the subcellular localization of mRNAs and detecting genes that display spatial variation within cells in high-resolution spatial transcriptomics. ELLA takes as inputs the spatial gene expression data along with the nuclear center and cell segmentation information. It first performs data pre-processing to create a unified cellular coordinate system to anchor diverse cell morphologies. It then fits a nonhomogeneous Poisson process model for each gene to capture its spatial distribution within cells, computes a P value to capture any subcellular expression pattern observed along the cellular radius, and estimates such a pattern in the form of estimated pattern expression intensity and pattern score. ELLA is capable of borrowing information across cells through a joint likelihood framework to substantially improve detection power, while taking advantage of multiple intensity kernel functions to capture the distinct subcellular expression patterns that may be encountered in various biological settings to ensure robust performance. b Quantile-quantile plots of the expected and observed −log10 P values in the baseline null simulation, where gene expression is randomly distributed spatially within cells. ELLA was compared to SPRAWL, Bento, and Wilcox. c Radar plots show the powers in the alternative simulations with multiple cells across eleven symmetric subcellular expression patterns, where gene expression is enriched in specific subcellular regions. ELLA was compared to SPRAWL and Wilcox, and power was evaluated based on 5% FDR. d Radar plots of the power of different methods in the alternative simulations with multiple cells across three asymmetric subcellular expression patterns, where gene expressions exhibit distinct asymmetric patterns. ELLA was compared to SPRAWL and Wilcox, and power was evaluated based on 5% FDR. ELLA’s power for radial punctate setting with piecewise constant kernels is marked with “*”. e Radar plots show the power of different methods in the additional alternative simulations with one cell across five symmetric subcellular expression patterns, where gene expression is enriched in specific subcellular regions within cells. ELLA was compared to Bento, and power was evaluated based on 5% FDR. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Simulations

We performed comprehensive simulations on imaging-based spatial transcriptomics to evaluate the performance of ELLA and compared it with three methods. The three methods include SPRAWL21, Bento20, and Wilcox, where Wilcox denotes a modified Wilcoxon rank sum test developed in the present study that uses expression measurements normalized by the area of subcellular regions to examine the difference in expression between nuclear and cytoplasmic areas. All methods examine one gene at a time, and all methods except Bento produce a P value for each gene; Bento outputs five prediction probabilities for five pre-specified cellular localization patterns, which cannot be converted to a P value. Among these methods, ELLA can analyze either one or multiple cells; SPRAWL and Wilcox can only analyze multiple cells; and Bento can only analyze one cell. Therefore, we compared ELLA with SPRAWL and Wilcox in all our main simulations on multiple cells, while comparing ELLA with Bento in additional simulations on only one cell. Unlike ELLA and SPRAWL, both Bento and Wilcox require nuclear boundary information in addition to cell boundary information (Table S1). We provide the actual nuclear boundary information to Bento and Wilcox, although this information may not be readily available in certain sequencing-based techniques, such as Seq-Scope8 and Stereo-seq9, and may not be accurately inferred in other techniques.

Simulation details are provided in “Methods”. Briefly, we sampled n different embryonic fibroblast cells from seqFISH+ data (Fig. S1) and simulated expression counts for 1000 genes to be spatially distributed within these cells. We examined type I error control of different methods in null simulations, where the simulated gene expression counts are randomly distributed spatially within each cell without any specific subcellular spatial expression patterns (Figs. 1b and S2). We also examined the power of different methods in alternative simulations, where the simulated gene expression counts are enriched in specific subcellular regions within the cells, exhibiting either symmetric (consisting of eleven distinct symmetric patterns; Figs. 1c, S3 and S4) or asymmetric patterns (three distinct asymmetric patterns, Figs. 1d and S5). These simple yet interpretable patterns are commonly observed in biological systems and can be modulated or combined to generate more complex spatial patterns. In the simulations, we first created a baseline setting and then varied the number of cells (n), the gene expression level (m), and, in the alternative settings, the strength of the subcellular expression patterns (s; “Methods”), one at a time on top of the baseline setting, to create additional settings. In total, we examined 13 null and 73 alternative settings, with 1000 replicates per setting.

In the null simulations, the P values from ELLA are well calibrated across settings, and so are the P values from SPRAWL, although SPRAWL failed to produce P values for the radial and punctate metrics in m = 1 settings (Figs. 1b, S6 and S7). Wilcox yielded inflated P values, especially in settings where the gene expression level is low, or where the number of cells is large (Figs. 1b, S6 and S7). The P value inflation observed in Wilcox suggests that the simple normalization procedure and the non-parametric Wilcoxon test are not sufficient to control for variance heterogeneity and subsequently type I error (Fig. S8, Table S2).

In the alternative simulations, because some methods failed to control for type I error, we evaluated power based on a fixed false-discovery rate (FDR) to ensure a fair comparison across methods (Methods). We first examined the eleven subcellular expression patterns in the symmetric pattern category, including two patterns with nucleus enrichment, two patterns with nuclear edge enrichment, five patterns with cytoplasmic enrichment, and two patterns with membrane enrichment. Based on an FDR threshold of 0.05, ELLA achieves consistently higher power (average = 0.68, range = 0.61–0.73) than the other methods (SPRAWL: average = 0.04, range = 0.00–0.09; Wilcox: average = 0.04, range = 0.00–0.15) in detecting each of the eleven patterns (Fig. 1c; Table S3). For SPRAWL, its radial and punctate metrics tend to exhibit very low power in detecting any of the patterns (average = 0.01, range = 0.00–0.03), presumably because these metrics are not well-suited for detecting symmetric patterns. The peripheral and central metrics of SPRAWL have low power for detecting the cytoplasmic enrichment patterns (average = 0.01, range = 0.00–0.04) but have slightly higher powers for detecting the membrane and nuclear enrichment patterns (average = 0.05, range = 0.01–0.09), as one might expect. Also, as expected, the power of ELLA, SPRAWL, and Wilcox all improve with increasing number of cells, increasing expression level, and increasing pattern strength across all eleven patterns, although the power of ELLA improves much faster compared to the other two methods (Fig. S9). For example, at an FDR of 0.05, the power of ELLA in detecting the first nucleus pattern is 0.01 with 10 cells, but increases to 1.00 with 300 cells, while the power of SPRAWL’s central metric only increases from 0.01 to 0.42, and the power of SPRAWL’s peripheral metric only increases from 0.00 to 0.66. The exceptions are Wilcox and SPRAWL’s radial metric, whose power for detecting nucleus patterns remains below 0.05 and barely improves as the number of cells increases. We also carefully examined the case where m = 1, a setting commonly observed in spatial transcriptomics datasets (e.g., 57.8% gene-cell pairs in a MERFISH data22), and found that ELLA achieved a power of 0.66 or 0.62 when either the pattern strength was strong or the number of cells was large (Fig. S10). Additionally, we examined another set of 11 alternative simulation settings with over-dispersed counts and found that ELLA consistently achieved high power and outperformed the other methods (Fig. S11).

ELLA is also more powerful than the other methods in detecting two of the three asymmetric subcellular expression patterns. These include the radial-cyto and punctate-cyto patterns, where gene expression is enriched in either a circular sector or a small subcellular disc in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1d). Specifically, for the radial-cyto pattern, ELLA achieved a power of 0.99 while Wilcox achieved a power of 0.00. For SPRAWL, its peripheral, central, radial, and punctate metrics achieved a power of 0.10, 0.00, 0.16, and 0.23, respectively. For the punctate-cyto pattern, ELLA achieved a power of 0.77 while Wilcox had zero power. For SPRAWL, its peripheral, central, radial, and punctate metrics achieved a power of 0.17, 0.00, 0.16, and 0.39, respectively (Fig. 1d; Table S4). Certainly, because ELLA models expression patterns along the cellular radius, it is not powered to detect radial-uniform asymmetric patterns, where gene expression is enriched in a circular sector of the cell completely uniformly (Fig. 1d), a scenario unlikely in practical biological applications.

Importantly, ELLA not only achieves high power in detecting genes with various subcellular expression patterns but also accurately estimates these patterns (Figs. S12 and S13). Specifically, the average KL-divergences achieved by ELLA for estimating the two pattern categories are 0.12 and 0.29, respectively (Table S5). To further summarize the observed subcellular pattern, ELLA computes a subcellular pattern score for each gene. This score represents the relative position of subcellular expression enrichment, with zero indicating enrichment in the cell nucleus and one indicating enrichment on the cell membrane (Methods). The majority of the pattern scores (77%) are within 0.1 of the truth across the three pattern categories, underscoring the accuracy of ELLA (Figs. S14 and S15, Table S6).

ELLA’s performance is robust to the number of kernels used (Fig. S16a), and its framework is general and allows for customized kernel choices. For example, employing a piecewise constant kernel (Fig. S16b) enhanced both ELLA’s power (0.77–0.961; Fig. 1d) and the accuracy of its intensity estimation (Fig. S16c) in the punctate-cyto setting.

We performed additional simulations with only one cell in order to compare ELLA with Bento (Fig. 1e). Bento is capable of detecting five pre-specified patterns, including enrichment in nucleus, nuclear edge, cytoplasm, cell boundary, and none. To favor the comparison towards Bento, we focused on comparing ELLA with Bento under five symmetric patterns that Bento specifically models, where gene expression is enriched in nucleus (including 2 patterns), nuclear edge (1), cytoplasm (1), or cellular boundary (1) under a relatively high expression level (m = 30) and a high pattern strength (s = 9) (Fig. S17). Because Bento cannot produce P values, we used the prediction probabilities output from Bento to rank genes, with which we measured powers based on FDR (Methods). We are able to compute FDR for Bento in simulations only because we know the truth, which is certainly unknown for any real data applications. In the simulations, ELLA achieves high power (Fig. 1e, average = 0.81, range = 0.59–0.91; Table S7) and accuracy (Figs. S18 and S19, Table S8) across all five patterns, consistently outperforming Bento (average = 0.10, range = 0.00–0.75).

We also performed simulations to evaluate the influence of cell segmentation accuracy. In the challenging scenario where the true expression pattern is enriched close to the cell membrane, ELLA provided accurate pattern estimation in the ideal segmentation setting. In the under-segmentation setting, the pattern was estimated reasonably accurately, remaining enriched close to the cell membrane. In the over-segmentation setting, the pattern was to some extent misestimated, appearing enriched in the cytoplasmic region adjacent to, but not coinciding with, the cell membrane. In the noisy segmentation setting, ELLA also produced a reasonably accurate estimation of the expected pattern (Fig. S20). Additionally, in the less challenging scenario where the true expression pattern is enriched in the nucleus, ELLA produced accurate results across all four segmentation settings (Fig. S21). Similar results are observed in both single-cell and multi-cell analysis (Fig. S22).

Seq-Scope mouse liver data

We applied ELLA to analyze four published datasets obtained using different high-resolution spatial transcriptomics technologies (Methods). The four datasets include liver data by Seq-Scope8, an embryo data by Stereo-seq9, an NIH/3T3 embryonic fibroblast cell line data by seqFISH+11, and a brain data by MERFISH22.

We first analyzed the Seq-Scope mouse liver data (Figs. 2a, S23 and S35), which contains 497–1349 genes measured on 870 cells from four cell types, with 82 to 276 cells per cell type (Figs. S36 and S37). The four cell types include periportal hepatocyte (PP; n = 276) and pericentral hepatocyte (PC; n = 276) in normal mice, and PP (n = 236) and PC (n = 82) cells in early-onset liver failure mice (TD23; Fig. S38). We were only able to apply ELLA to the data, as SPRAWL and Bento are not applicable to sequencing-based data, and the nuclear boundary information required for Wilcox and Bento was not available.

a Representative data snapshot tile 2107 (experiment on 10 tiles). Left panel displays the full tile with four gene sets (PC marker genes, blue; PP marker genes, green; Table S10; mitochondria genes, black; nuclear genes, red; Table S13) and cell segmentations. Middle panel zooms into a subregion and displays unspliced expression densities (green), nuclear centers (crosses), gene expressions, and cell segmentations. Right panel displays the H&E staining image. b Estimated spatial expression patterns for genes in five ELLA clusters, the upper panel shows gene counts and proportions, the middle panel shows expression intensities, and the lower panel shows pattern scores. c For each cluster, one representative gene is displayed with its name, P value (3.13e-12, 0.030, 3.27e-14, 0.002, 0.032), and expression intensities overlaid on density maps. Corresponding gene expressions in five selected cells are illustrated with cell boundaries and aligned nuclear centers (crosses). d Bar plot shows the average sn/sc RNA ratio across genes in pattern clusters 1 (red), 2–5 (green; P value = 5e-36), and non-cluster 1 genes (i.e., clusters 2–5 plus the nonsignificant genes; gray; P value = 1e-20). Nuclear-enriched genes (cluster 1) exhibit higher relative snRNA levels. e Bar plot shows the average unspliced/spliced expression ratio across genes in pattern clusters 1, 2–5 (P value = 2e-26), and non-cluster 1 genes (P value = 2e-3). Nuclear-enriched genes (cluster 1) exhibit higher unspliced/spliced ratios. f Bar plot displays the average gene length, measured by four metrics (x-axis), across genes in pattern clusters 1, 2–5, and non-cluster 1 genes. Nuclear-enriched genes (cluster 1) exhibit longer gene lengths. g Bar plot displays the proportions of SRP-coded genes for genes in pattern clusters 1, 2–5 (P value = 3e-7), and non-cluster 1 genes (P value = 3e-33). Cytoplasmic enriched genes (clusters 2–5) frequently encode SRP. Statistical significance for pair-wise comparisons (*<0.05; **<0.01; ***<0.001; without adjustments for multiple comparisons) is based on two-sided Mann–Whitney U test (d–f) or Fisher’s exact test (g) sample size n = 4145 genes (d, e), data are presented as mean values ± the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile, d–f). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

At an FDR of 5%, ELLA identified 317, 308, 315, and 129 genes that display subcellular expression patterns in normal PP, PC cells, and TD PP, PC cells, respectively. 300 of these genes, including six transcription factors (Mlxipl, Jarid2, Zbtb20, Thrb, Sox5, and Creb3l3), were detected in two or more cell types. Based on their subcellular spatial expression patterns, we clustered the detected genes into five distinct pattern clusters (Fig. 2b, “Methods”): 150 genes (13%) display a nuclear expression pattern (cluster 1), 175 (16%) genes display a nuclear edge expression pattern (clusters 2–3), and 788 (71%) genes display one of the two cytoplasmic expression patterns near the cellular membrane (clusters 4–5). Example cells from the five clusters are shown in Fig. 2c.

We carefully examined the basic properties of the genes detected by ELLA in each of the five pattern clusters. For genes with subcellular enrichment near the nuclear center (cluster 1), we found them to have significantly higher snRNA expression in a similar cell type from a separate study24 (cluster 1 vs clusters 2–5 fold enrichment = 9.38, Mann–Whitney U test P value = 5e-36; cluster 1 vs all the remaining genes fold enrichment = 4.42, P value = 1e-20; Fig. 2d) with significantly higher unsplice/splice ratio supporting their nuclear enrichment (cluster 1 vs clusters 2–5 fold enrichment = 1.55, Mann–Whitney U test P value = 2e-26; cluster 1 vs all the other genes fold enrichment = 1.12, P value = 2e-3; Fig. 2e). In addition, these genes have significantly longer gene lengths compared to genes in the other clusters or the remaining genes, both in terms of the average isoform length (Mann–Whitney U test P value = 2e-6 and 1e-3), the longest isoform length (P value = 5e-12 and 3e-7), and the total length across exons (P value = 2e-13 and 4e-7; Fig. 2f). Long genes require additional time to be transcribed and exported25 and their enrichment in the nucleus may serve as a reservoir so that they can be quickly exported to the cytoplasm for translation in response to stimuli26.

For genes with subcellular enrichment in the cytoplasm (clusters 4–5), we found them to frequently encode a signal recognition peptide (SRPs; proportion = 29.60%) as compared to the genes in the nuclear cluster 1 (proportion = 10.67%; Fisher’s exact test P value = 3e-7) or the remaining genes (proportion = 16.45%; P value = 3e-33; Fig. 2g). SRPs are short sequence segments located at the N-termini of newly synthesized proteins that are sorted towards the secretory pathway27. Proteins with SRPs typically reside in the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, or plasma membrane, and include secreted proteins. The enrichment of genes with SRPs among cytoplasmic genes suggests that mRNAs for the secretory pathway also tend to localize in the cytoplasm or near the membrane. This localization likely aids in directing the translated proteins toward their designated subcellular compartments.

We narrow down our focus to the normal PC cell type, which has the largest number of genes with subcellular spatial expression patterns, to carefully examine the 317 genes detected by ELLA (Fig. S38). Among the 52 nuclear (cluster 1) genes (Fig. S39a, Table S9), four of them (Malat1, Neat1, Gm13775, and 1700095B10Rik) are long noncoding RNAs that are previously known to be localized to the nucleus28. 45 of them are protein-encoding genes, including two previously known nuclear-enriched mRNAs, Chd9 and Ppara, dovetailing recent findings that retention of mRNAs in the nucleus may help buffer noise in the stochastic mRNA production process29. Seven of them (Malat1, Neat, n-R5-8s1, Gm24601, Mlxipl, Mafb, and Echdc2) were also found among the top 10 nuclear-enriched genes identified in the original Seq-Scope study, which explicitly searched for genes enriched within 10 μm from the nuclear center8. Among the seven genes, four encode transcription factors or proteins with transcription factor activity. For example, Mlxipl, one of these genes, is a transcription factor retained in the nuclear speckles in the liver30. Finally, all 12 significant mitochondrial genes were detected as cytoplasmic localized (clusters 4–5; Fig. S39b, Table S10), and all four significant PC cell type marker genes were detected as cytoplasmic or membrane localized (clusters 4–5; Fig. S39c, Table S10).

Stereo-seq mouse embryo data

Next, we analyzed the Stereo-seq mouse embryo data, focusing on two major cell types localized in the cardiothoracic region on slice E1S3 on the 16.5 embryo (Figs. 3a, S40 and S41): precursor muscle cells, or myoblasts (596 cells with 2008 genes); and mature muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes (553 cells with 1743 genes; Fig. S42). We were only able to apply ELLA to the data, as SPRAWL and Bento are not applicable to sequencing-based data, and the nuclear boundary information required for Wilcox and Bento was not available in this data.

a Data snapshot for slice E1S3, left shows the nucleic acid staining image, middle shows expressions from three gene sets (erythrocyte, gray; myoblast, blue; cardiomyocyte, green; Table S11), and right zooms into a subregion showing myoblast (blue), cardiomyocyte (green), and Malat1 (red) expression with nuclear centers (crosses) overlaid on the staining image. b Estimated spatial expression patterns for genes in five ELLA clusters: upper panel shows gene counts and proportions, middle shows expression intensities, and lower shows pattern scores. c Example genes and cells for the five pattern clusters. Upper panel lists gene name, P value (7e-4, 2.82e-4, 1.1e-4, 0.004, 9.11e-4), and expression intensities overlaid on density maps. Lower panel shows the expression of the corresponding genes in five selected cells, overlaid with cell boundaries and aligned nuclear centers (crosses). d Bar plot shows the average unspliced/spliced ratio across genes in pattern clusters 1–3 (red), 4–5 (green; P value = 1e-7), and non-cluster 1–3 genes (i.e., clusters 4–5 plus the nonsignificant genes; gray; P value = 7e-50). Genes enriched close to the nuclear center (clusters 1–3) exhibit higher unspliced/spliced ratios. e Bar plot displays average gene length, measured by four metrics (x-axis), across genes in pattern clusters 1–3, 4–5, and non-cluster 1–3 genes. Genes enriched close to the nuclear center (clusters 1–3) exhibit longer gene lengths. f Bar plot displays proportions of transcription factors (TFs) for genes in pattern clusters 1–3, 4–5 (P value = 0.325), and non-cluster 1–3 genes (P value = 2e-6). Genes enriched close to the nuclear center (clusters 1–3) contain a higher proportion of TFs. g Bar plot displays the proportions of ribosomal protein (RP) genes for genes in pattern clusters 1–3, 4–5 (P value = 2e-3), and non-cluster 1–3 genes (P value = 0.327). Cytoplasmic enriched genes (clusters 4–5) contain a higher proportion of RP genes. Statistical significance for pair-wise comparisons (*<0.05; **<0.01; ***<0.001; without adjustments for multiple comparisons) is based on two-sided Mann–Whitney U test (d, e) or Fisher’s exact test (f, g), sample size n = 3683 genes (d, e), data are presented as mean values ± the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile, d, e). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

At an FDR of 5%, ELLA identified 108 and 153 genes to be spatially variable within myoblasts and cardiomyocytes, respectively (Fig. S43). 32 genes were detected in both cell types, including four transcription factors. Based on their subcellular spatial expression patterns, we clustered the detected genes into five distinct clusters (“Methods,” Fig. 3b): 89 genes (34%) display a nuclear expression pattern (cluster 1), 114 genes (43%) display one of the two nuclear edge expression patterns (clusters 2–3), and 58 genes (22%) display one of the two cytoplasmic expression patterns (clusters 4–5). Example cells from the five clusters are shown in Fig. 3c.

We carefully examined the basic properties of the genes detected by ELLA in each of the five pattern clusters. For genes with subcellular enrichment near the nuclear center (clusters 1–3), we again found them to have significantly higher unsplice/splice ratio (clusters 1–3 vs clusters 4–5, fold enrichment = 1.99, P value = 1e-7; clusters 1–3 vs all the remaining genes, fold enrichment = 3.20, P value = 7e-50; Fig. 3d), which is also negatively correlated with the expression pattern score (Pearson correlation = −0.355, P value = 9e-86). Nuclear genes (clusters 1–3) also tend to have longer gene lengths compared to genes in the other clusters or the remaining genes, in terms of the average isoform length (P value = 4e-4 and 6e-30), the median isoform length (P value = 2e-3 and 4e-19), the longest isoform length (P value = 2e-4 and 2e-38), and the total length across exons (P value = 7e-6 and 4e-42; Fig. 3e). Genes in clusters 1–3 contains a higher proportion of newly synthesized RNA based on a separate SLAM-seq study31 (clusters 1–3 vs clusters 4–5 fold enrichment = 1.12, Mann–Whitney U test P value = 0.169; clusters 1–3 vs all the remaining genes, fold enrichment = 1.10, P value = 0.038; Fig. S44).

In addition, genes in clusters 1–3 are enriched with transcription factors (proportion = 15.91%) as compared to the other clusters (clusters 4–5, proportion = 4.55%, Fisher’s exact test P value = 0.325) or the remaining genes (proportion = 5.64%, P value = 2e-6; Fig. 3f). For the genes with subcellular enrichment in the cytoplasm (clusters 4–5), we found them to contain a significantly higher proportion of RP genes (clusters 4–5, 6.90% vs clusters 1–3, 0%, Fisher’s exact test P value = 2e-3; clusters 3–4 vs all the remaining genes, 4.71%, P value = 0.327; Fig. 3g, “Methods”), supporting their localized synthesis. Finally, in terms of 3’UTR length (Supplementary Note 1, Fig. S45), 19 genes display significant variation across five expression pattern clusters (Fig. S46), 21 genes display significant correlation with expression pattern strength (Fig. S47), and 18 genes display significant correlation with expression pattern score (Fig. S48).

We investigated the shared and distinct features of the genes detected by ELLA in both myoblasts and cardiomyocytes (Fig. S49). Both cell types exhibit a similar proportion of genes across the five expression pattern clusters, with common genes displaying similar estimated expression intensities (Figs. S50 and S51). Among the detected genes, 4 transcription factors are detected in both cell types (14 unique in myoblasts and 21 unique in cardiomyocytes; Fig. S52a). These transcription factors are enriched in GO gene sets related to regulation of transcription, development, and various regulatory categories (Fig. S52b, c). In addition, among the detected genes, two long noncoding genes are detected in both cell types (four unique in myoblasts and one unique in cardiomyocytes; Fig. S53), including Malat1, which localized near the nuclear center (clusters 1–3).

SeqFish+ mouse embryonic fibroblast data

Next, we analyzed the NIH/3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line data generated by seqFISH+11, which contains 2,747 genes measured on 171 embryonic fibroblast cells (Figs. 4a and S54). We were unable to apply SPRAWL due to its heavy computational burden but were able to apply Bento, as this data contains nucleus segmentation information.

a Data snapshots. Left shows all transcripts (gray) across 17 batches. Middle zooms into batch 14 with transcripts (gray), nuclear centers (crosses), and nuclear (dashed gray) and cell (solid gray) boundaries. Right shows expression of three gene sets (nuclear/edge, red; cytoplasmic, green; protrusion, blue; Table S14) with nuclear centers (crosses) and boundaries. b Estimated spatial expression. Upper panel shows gene numbers and proportions, middle shows expression intensities, and lower shows pattern scores. c Example genes and cells for the five pattern clusters. Upper panel lists gene name, P value (1.1e-23, 1.03e-34, 3.21e-23, 2.29e-29, 7.32e-10), and expression intensity on density maps. Lower panel shows the expression of the corresponding genes in one selected cell, overlaid with the cell boundary and the nuclear center (cross). d Bar plot displays average gene length, measured by four metrics (x-axis), across genes in pattern clusters 1–3 (red), 4–5 (green), and non-cluster 1–3 genes (i.e., clusters 4–5 plus the nonsignificant genes; gray). Genes enriched close to the nuclear center (clusters 1–3) exhibit longer gene lengths. e Bar plot displays the proportions of transcription factors (TFs) for genes in pattern clusters 1–3, 4–5 (P value = 8e-3), and non-cluster 1–3 genes (P value = 8e-3). Genes enriched close to nuclear center (clusters 1–3) contain a higher proportion of TFs. f Estimated spatial expression patterns of genes across cell cycle phases (G1, S, G2M). Upper panels show expression intensities, middle panels show pattern scores, and lower panels show score distributions. g Upper panel shows violin plots of pattern scores across cell cycle phases for different clusters; G1-significant genes are less likely to be nuclear-enriched and have larger scores than those in S and G2M (one-sided Mann–Whitney U test). Lower panel shows line plots of score trajectories across phases. Statistical significance for pair-wise comparisons (*<0.05; **<0.01; ***<0.001; without adjustments for multiple comparisons) is based on two-sided Mann–Whitney U test (d) or Fisher’s exact test (e), sample size n = 2738 genes (d, g), data are presented as mean values ± the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile, d, g). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

At an FDR of 5%, ELLA identified 2725 genes to display subcellular spatial expression patterns, with 244 being transcription factors. The subcellular expression patterns of the detected genes can be clustered into five distinct clusters (Fig. 4b, “Methods”): 270 genes (10%) display a nuclear expression pattern (cluster 1), 878 genes (32%) display one of the two nuclear edge expression patterns (clusters 2–3), and 1577 genes (58%) display one of the two cytoplasmic expression patterns (clusters 4–5). The identified genes included 45 out of 55 genes with subcellular localization patterns detected through an ad hoc procedure in the seqFISH+ original study. The localization categorization of the 45 genes closely aligns with the pattern reported in the original study but with finer details: for example, 16 genes detected as enriched generally in the nuclear and perinuclear regions in the original study were clustered here as cluster 1 (2 genes), cluster 2 (7 genes), cluster 3 (4 genes), or cluster 4 (3 genes) genes (Fig. S55). Example cells from the five clusters are shown in Fig. 4c.

Because Bento is only applicable to individual cells, we randomly selected 20 cells (Fig. S56) and applied both ELLA and Bento to analyze one cell at a time on 356-1213 (mean = 808) genes with more than 10 counts. Across cells, Bento classified 38.2% genes to one of the four compartmental patterns, 21.5% genes to a pattern called “none,” and the remaining 40.39% genes to either none of these five patterns or multiple patterns (Fig. S57a). Certainly, Bento is unable to produce P values nor quantifications of statistical significance for any of the genes. ELLA was able to allocate all genes to five identified patterns, with 12.41% genes achieving statistical significance (5% FDR; Fig. S57b, c). For genes detected by ELLA and classified by Bento to patterns other than none, their expression pattern classifications are largely consistent with each other, although ELLA offers more detailed results (Fig. S58). For example, 90.12% of the “nuclear” patterned genes detected by Bento were also identified as nuclear genes by ELLA, and these genes were classified by ELLA into two separate clusters (65.13% genes in cluster 1 with nuclear pattern and 27.80% genes in cluster 2 with nuclear edge pattern).

We examined the basic properties of the genes detected by ELLA in each of the five pattern clusters. For genes with subcellular enrichment near the nuclear center (clusters 1–3), we found them to have significantly longer gene lengths compared to genes in the other clusters (clusters 4–5) or the remaining genes, in terms of the average isoform length (P value = 2e-16 and 1e-15), the median isoform length (P value = 1e-12 and 4e-12), the longest isoform length (P value = 6e-11 and 2e-10), and the total length across exons (P value = 7e-5 and 1e-4; Fig. 4c). These four types of gene lengths are also significantly negatively correlated with the ELLA pattern scores (Pearson correlation ranges from −0.15 to −0.08; P values range from 1e-10 to 4e-3). Genes with enrichment near the nuclear center (clusters 1–3) are also enriched with transcription factors (proportion = 10.63%) as compared to the other clusters (clusters 1 and 4–5, proportion = 7.61%, P value = 8e-3) or the remaining genes (proportion = 7.65%, P value = 8e-3; Fig. 4e).

Given that the data is collected from cultured cells that undergo continuous cell division, we explored whether the cell cycle may influence the subcellular spatial localization of gene expression. To do so, we first clustered fibroblast cells into three distinct cell-cycle phases, including G1 (n = 36, 21%), S (n = 83, 49%), and G2M (n = 52, 30%). We then applied ELLA to analyze each cell phase separately and detected 728, 2368, and 1726 genes with subcellular spatial expression patterns, respectively (Fig. 4f). We found that genes significant in the G1 phase are less likely to be enriched close to the nuclear center and display larger pattern scores compared to the genes in the S and G2M phases, regardless which cluster the genes belong to (pattern score fold enrichment in G1 vs S and G2M = 1.53, 1.14, 1.11, 1.15, and 1.07, for the five clusters, respectively; one side Mann–Whitney U test P value = 2e-3, 0.21, 8e-3, 3e-48, 6e-7; Fig. 4g), suggesting that DNA replication during the S phase enhances nuclear enrichment in S and G2M phases. Among the detected genes, 723 are shared across three cell cycles, including 49 (7%), 47 (7%), 129 (18%), 407 (56%), and 84 (12%) genes for each of the five clusters, respectively. ELLA was able to detect dynamics of subcellular expression patterns across cell cycle phases. For example, in each pattern cluster, a subset of genes displays decreasing pattern scores through G1, S, and G2M phases, corresponding to increasing enrichment towards the nucleus (Figs. 4g and S59, “Methods”).

MERFISH mouse brain data

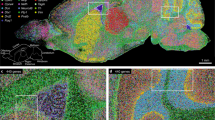

Lastly, we analyzed the adult mouse brain data generated by MERFISH22 (Figs. 5a and S60). We focused on four major cell types residing in the midbrain: excitatory neurons (EX, n = 577), inhibitory neurons (IN, n = 525), astrocytes (Astr, n= 480), and oligodendrocytes (Olig, n = 948) with 557–878 genes per cell type (Fig. S57). Besides ELLA, we were also able to apply SPRAWL to the data, but were unable to apply Wilcox and Bento as the nuclear boundary information required for these two methods was not available in this data.

a Data snapshot. Left shows the DAPI image, middle shows expression of four gene sets (EX, blue; IN, green; Astr, red; Olig, orange; Table S12), and right zooms into a subregion showing the same gene sets with cell centroids (crosses) and segmentation boundaries across five z-stacks. b Estimated spatial expression. Upper panel shows gene numbers and proportions, middle shows expression intensities, and lower shows pattern scores. c Example genes and cells for the four pattern clusters. Upper panel lists gene name, P value (1.97e-14, 3.67e-5, 1.23e-4, 2.05e-12), and expression intensities on density maps. Lower panel shows gene expression in five selected cells, overlaid with cell boundaries and aligned nuclear centers (crosses). d Bar plot shows the average sn/sc RNA ratio across genes in clusters 1–2 (red), 3–4 (green; P value = 7e-26), and non-cluster 1–2 genes (i.e., clusters 3–4 plus the nonsignificant genes; gray; P value = 1e-13). Genes enriched close to the nuclear center (clusters 1–2) exhibit higher snRNA levels. e Bar plot displays average gene length, measured by four metrics (x-axis), in pattern clusters 1–2, 3–4, and non-cluster 1–2 genes. Genes enriched close to the nuclear center (clusters 1–2) exhibit longer gene lengths. f Bar plot displays proportions of transcription factors (TFs) for genes in pattern clusters 1–3 (orange), 4 (blue; P value = 6e-5), and non-cluster 4 genes (i.e., clusters 1–3 plus the nonsignificant genes; gray; P value = 1e-3). Genes enriched close to the cell boundary (cluster 4) contain a lower proportion of TFs. g, h Stem plots show the −log10 P values of the top 10 enriched gene sets in GSEA analysis for genes in pattern cluster 3 and 4, respectively. Gene sets enriched with cluster 3 or 4 genes are related to dendrites and synaptic transmission, and signaling. Statistical significance for pair-wise comparisons (*<0.05; **<0.01; ***<0.001; without adjustments for multiple comparisons) is based on two-sided Mann–Whitney U test (d, e) or Fisher’s exact test (f), sample size n = 2923 genes (d, e), data are presented as mean values ± the interquartile range (25th–75th percentile, d, e). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

At an FDR of 5%, ELLA identified 298, 261, 154, and 151 (total = 864, total distinct = 485) genes that display subcellular spatial expression patterns in EX, IN, Astr, and Olig cells, respectively (Fig. S61). 256 of these genes, including 47 transcription factors, were detected in two or more cell types. The subcellular spatial expression patterns of the detected genes can be clustered into four distinct pattern clusters (Fig. 5b, “Methods”): 171 genes (20%) display a nuclear expression pattern (cluster 1), 298 (34%) genes display a nuclear edge expression pattern (cluster 2), and 395 genes (46%) display one of the two cytoplasmic expression patterns (clusters 3–4). Example cells from the four clusters are shown in Fig. 5c. Compared to the number of genes (864) detected by ELLA, the peripheral, central, radial, and punctate metrics of SPRAWL detected 572, 305, 138, and 238 genes, respectively, with 434 distinct genes in total, the majority of which (345; 79.49%) are overlapped with ELLA (Fig. S62). Note that SPRAWL radial and punctate metrics excluded 57.8% of the unqualified gene-cell pairs that have less than two counts of a gene in a cell, which likely leads to their lower power as well as their failure in producing P values for a small percentage of genes across cell types (2.3%, 272 genes).

We carefully examined the basic properties of the genes detected by ELLA in each of the four pattern clusters. For genes with subcellular enrichment near the nuclear center (clusters 1–2), we found them to have significantly higher snRNA expression in the same cell types from a separate study (clusters 1–2 vs clusters 3–4, fold enrichment = 1.36, P value = 7e-26; clusters 1–2 vs all remaining genes fold enrichment = 1.17, P value = 1e-13; Fig. 5d32). We also found them to have significantly longer gene lengths compared to genes in the other clusters or the remaining genes, in terms of the average isoform length (P value = 4e-4 and 1e-4), the median isoform length (P value = 0.03 and 8e-3), the longest isoform length (P value = 1e-6 and 3e-9), and the total length across exons (P value = 2e-7 and 9e-12; Fig. 5e). In addition, the cluster 4 genes contain a lower proportion of transcription factors (proportion = 3.90%) as compared to the other clusters (clusters 1–3, proportion = 21.22%, P value = 6e-5) or the remaining genes (proportion = 16.01%, P value = 1e-3; Fig. 5f). Gene sets enriched with the clusters 1–2 genes are related to various functions including transcription regulation (Fig. S63), while gene sets enriched with clusters 3–4 genes are particularly related to dendrites and synaptic transmission and signaling (Fig. 5g, h). Several detected genes in clusters 3–4 are associated with cell-cell communication33. For example, several secreted factor/modulator-related genes, such as Penk, Cxcl14, Agt, and Serpine2, and receptor genes like Gabbr2, Gpr37l1, and S1pr1, are detected to be enriched close to the cell membrane, suggesting potential signaling between neighboring cells. Adhesion-related genes such as Gja1 and Cldn11 are enriched close to the membrane, indicating potential roles in physical cell-cell contact. These patterns support a link between mRNA localization and cellular interaction interfaces.

We investigated the shared and distinct features of the genes detected by ELLA in the two neuronal cell types, excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Excitatory neurons contain a slightly higher proportion of nuclear localized genes (cluster 1), and a lower proportion of cell membrane localized genes (cluster 4) compared to inhibitory neurons (Fig. S64). A fraction of the detected genes (Jaccard index = 47.5%) are shared between the two neuronal types, with 13, 39, 53, and 2 shared genes detected across clusters 1–4 and with similar estimated expression patterns (Figs. S65 and S66). In addition, the majority of the detected transcription factors (126) are shared between the two neuronal types, while 20 are uniquely detected in excitatory neurons and 9 are uniquely detected in inhibitory neurons (Fig. S67). The 126 shared transcription factors are enriched in 112 gene sets related to various transcription regulations and neuron differentiation (Figs. S68 and S69). Three out of eight long noncoding genes are detected in both cell types (Fig. S70a). All of the three common long noncoding genes are localized close to the nucleus in both cell types (cluster 2; Fig. S70b). Most cell type marker genes (9 out of 14) detected by ELLA belong to clusters 3–4 with cytoplasmic or membrane localization patterns (Fig. S71).

We evaluated ELLA’s performance across multiple data replications by analyzing all three tissue sections from the 10x Xenium mouse brain data. ELLA detected 192, 197, and 199 genes to have subcellular spatial patterns in neuron cells across the three sections, respectively, with a substantial number of overlaps (175 genes). These genes were clustered into three pattern clusters in each section. Within each pattern cluster, a substantial proportion of genes were commonly detected across all replicate sections (Fig. S72a), with most genes displaying similar estimated expression patterns (Fig. S72b).

Discussion

We have presented ELLA, a statistical method for modeling and detecting spatially variable genes within cells that display various subcellular spatial expression patterns in high-resolution spatial transcriptomic studies. ELLA models the spatial distribution of gene expression measurements along the cellular radius using an over-dispersed NHPP, leverages multiple kernel functions to detect a variety of subcellular spatial expression patterns, and is capable of analyzing a large number of genes and cells. We have illustrated the benefits of ELLA through simulations and real data applications across diverse experimental setups. Specifically, we examined Seq-Scope and Stereo-seq, which represent sequencing-based technologies, with Seq-Scope offering high throughput in a small capture area and Stereo-seq covering a large area with relatively sparse capture. We also examined seqFISH+ and MERFISH represent imaging-based technologies, with seqFISH+ capturing dense signals in small areas and MERFISH covering larger areas with lower density. We also tested ELLA on other popular datasets, such as 10x Xenium, highlighting ELLA’s applicability across diverse subcellular spatial transcriptomics platforms and data types.

Across all four datasets, we consistently observed that genes enriched in the nuclear compartment tend to exhibit longer gene lengths and are more frequently associated with lncRNAs and transcription factors. This pattern supports the hypothesis that longer or regulatory transcripts may be retained in the nucleus for functional or kinetic reasons. Conversely, genes enriched in the cytoplasm or at the membrane frequently contain signal peptides or encode RPs, a trend observed repeatedly across multiple datasets. At the same time, ELLA also revealed dataset-specific findings. For example, the influence of the cell cycle on subcellular localization was revealed in the fibroblast dataset due to the suitability of this dataset for capturing cell cycles. In the MERFISH mouse brain data, we identified membrane-enriched genes related to ligand-receptor interactions and cell signaling pathways. While some detected subcellular patterns may reflect technical artifacts, such as technological variations, segmentation inaccuracies, and detection biases, these sources of noise are likely mitigated in ELLA through joint analysis of multiple cells and effective error controls. The consistent finding across datasets and platforms further suggests that the main discoveries are unlikely to be driven by technical confounders. These findings highlight that while ELLA reliably recovers robust biological patterns across technologies and tissues, it is also capable of conducting dataset-specific analysis to uncover dataset-specific biology, underscoring its utility for both comparative and targeted subcellular transcriptomic analysis.

We have primarily focused on utilizing ELLA to capture the spatial variation of gene expression along the cellular radius within cells, which is inherently one-dimensional and rotation invariant. Detecting rotation-invariant and radially symmetric patterns enables information sharing across multiple cells, thereby enhancing statistical power. In addition, rotation-invariant patterns facilitate results interpretation, as the detected genes can be naturally categorized into cellular compartments, including the nucleus, nuclear membrane, and cellular membrane. The framework of ELLA, however, is general and can be extended to two- or three-dimensional cellular space, enabling modeling of 2D cellular space with kernels defined on a unit circle or 3D cellular space with kernels defined on a unit ball. Use of different kernels in higher-dimensional spaces may further enhance the power of ELLA. For example, radial kernel functions may be particularly effective in detecting genes with radial patterns in 2D cellular space—a pattern that, although unlikely to be biological, the one-dimensional version of ELLA is ill-equipped to detect, as shown in the simulations. Such extensions, however, necessitate careful consideration, as additional modeling features, such as rotation invariance, may need to be incorporated into the kernel structure to effectively utilize information from multiple cells. Additionally, the mRNA subcellular enrichment revealed by ELLA is tied to the mRNA metabolism, such as nuclear exportation and degradation. Thus, integrating spatial transcriptomics localization analysis with mRNA metabolism measurements such as SLAM-seq34 represents a promising future direction.

ELLA leverages nuclear center and cellular boundary information extracted from the spatial transcriptomics data or its accompanying histology image data to register and segment cells through multiple pre-processing steps. These pre-processing steps can vary substantially across different spatial transcriptomics technologies. For example, the accompanying H&E and nucleic acid staining images in Seq-Scope and Stereo-seq need to be registered with the spatial transcriptomics data to obtain the cellular boundary information, while the DAPI images in the imaging-based datasets have already aligned with the spatial transcriptomics data without the need for further registration. Similarly, the nucleus center in sequencing-based datasets is determined based on the enrichment of unspliced sequencing read counts, while in imaging-based datasets is determined as the geometric center of the nuclear segmentation. Importantly, ELLA provides accompanying scripts tailored to distinct spatial transcriptomics platforms to streamline these pre-processing steps. While ELLA, in principle, can accommodate any cell segmentation method, in practice, the accuracy of these segmentations can influence the results (Methods). More accurate segmentation methods that better capture true cell shapes and boundaries are likely to enhance the fidelity of spatial localization pattern analysis. Therefore, we recommend using high-quality, biologically relevant cell segmentation methods when applying ELLA to real datasets. We also offer several recommendations to mitigate the effects of segmentation contamination. First, obtaining accurate cell segmentation, either by leveraging the state-of-the-art computational tools or through expert curation, is crucial. Second, accurate segmentation, under-segmentation, or noisy segmentation is generally preferable to consistently over-segmentation. Third, in multi-cell analysis, a heterogeneous mix of segmentation types, where some cells are over-segmented and others are under-segmented, can help mitigate the impact of segmentation contamination. Finally, we note that accurate cell segmentation using existing tools can be challenging for cells with complex shapes or non-mononuclear structures. Adapting ELLA to accommodate these complexities represents an important direction for future work.

In addition to the nuclear center and cellular boundary information, additional data, such as nuclear boundary information, can also be integrated into ELLA as needed. In such cases, the registration step of ELLA can be extended to register cells based on the nuclear center, nuclear boundary, as well as cellular boundary. Furthermore, the modeling framework of ELLA can be extended to accommodate this additional information. Investigating the effectiveness of ELLA in the context of additional feature information represents an important avenue for future research.

Finally, the computational complexity of ELLA scales linearly with the number of cells, the number of transcripts per cell, and the number of kernels used in the model, making it computationally efficient. For example, the runtimes for analyzing one gene across 50 cells with varying transcript counts (from 1 to 100) range from 7.7 min to 13.9 min (Fig. S73a), and the runtimes for analyzing one gene with 5 transcripts per cell as the number of cells increases (from 5 to 300) range from 0.9 min to 75.5 min (Fig. S73b). When modeling genes across multiple cell types, ELLA can be applied independently to each gene in each cell type to take advantage of parallel computation.

Methods

ELLA overview

Subcellular resolution spatial transcriptomics and data pre-processing

We consider a high-resolution spatial transcriptomics study that collects gene expression measurements at the subcellular level for G genes on S spatial locations. These locations have known two-dimensional x and y spatial coordinates that are recorded during the experiment. For a gene g, its raw expression measurement at each location is represented either as a count or as a binary label, depending on the spatial transcriptomic technique. Specifically, for sequencing-based techniques such as Seq-Scope8 and Stereo-seq9, the expression of a gene on a given location is measured as the number of read counts mapped to the gene. For imaging-based techniques such as seqFISH+11 and MERFISH10, the expression of a gene is measured as the presence (1) or the absence(0) of a hybridization signal at a given location.

To facilitate joint modeling across cells, we create a unified cellular coordinate system to anchor diverse cell shapes and morphologies. To do so, for the high-resolution spatial transcriptomics data, we first follow standard data pre-processing procedures to segment the tissue into cells. We cluster these cells into different cell types based on marker gene expression. For each cell in turn, we obtain the center of its nucleus and assign the spatial coordinates to all expression measurement locations within the cell. For each measured location inside the cell, we calculate two distances: its distance to the nuclear center \({d}_{1}\), and its distance to the cell boundary \({d}_{2}\), in the opposite direction from the nuclear center (Fig. S74a). With these two distances, we further calculate the relative position of the measured location inside the cell as the ratio between the nuclear distance and the summation of the two distances \({{d}_{1}}^{{\prime} }={d}_{1}/({d}_{1}+{d}_{2})\). The relative position ranges between 0 and 1 and allows us to create a unified coordinate system across cells, enabling the joint modeling of multiple cells regardless of their sizes and shapes (Fig. S74b). Importantly, we compute the cellular distances for each measured location efficiently using a binning-based numerical approximation approach. Specifically, we first divided each cell from the center of the nucleus into 100 circular sectors of equal angle measure. In each sector ν, we denote \({r}_{\nu }\) as the maximum distance between the center of the nucleus and the cellular boundary in the sector using the cell segmentation boundary or mask. For each expression measurement location within the sector, we obtain its distance from the center of the nucleus and normalize it by \({r}_{\nu }\) to obtain its relative position. This binning-based approximation approach speeds up computation by eliminating the requirement of computing the distance of each measurement location to the cell boundary, facilitating parallel computation across cells and sectors.

ELLA model for detecting genes with subcellular spatial expression patterns

With the expression measurements and their relative positions within each cell, we aim to identify spatially variable genes that display subcellular spatial expression patterns along the cellular radius that points from the center of the nucleus towards the cellular boundary. The genes with subcellular spatial expression patterns are often localized in certain cellular compartments such as the nucleus, cytoplasm, Golgi apparatus, or cell membrane, and may display distinct enrichment associated with such compartmentalization. To identify those genes, we examine one gene at a time and jointly model its expression measurements within n cells that belong to a given cell type. For the ith cell (\(i=1,\ldots,n\)), we assume that the gene is measured on \({m}_{i}\) spatial locations. For the jth measured location (\(\,\,j=1,\ldots,{m}_{i}\)), we denote the measured gene expression value as \({y}_{{ij}}\), which is either a count or a binary value. We denote the relative position of the jth measured location as \({r}_{{ij}}\in [{\mathrm{0,1}}]\), where 0 corresponds to the center of the nucleus and 1 corresponds to the cellular boundary.

We model the subcellular spatial localization of gene expression within each cell using a one-dimensional over-dispersed NHPP model, which is effectively a tailored Cox Process model. Specifically, we assume that the gene expression counts summed across all relative positions within a given interval \(\left[a,b\right]\subset [{\mathrm{0,1}}]\) on the cellular radius follow an over-dispersed Poisson distribution, with the rate parameter being the integration of an underlying NHPP density function in the interval \(\left[a,b\right]\), where the NHPP density function may vary with respect to the relative position within the cell. Mathematically, the model is expressed as:

where \({Poi}\) denotes a Poisson distribution and \({\lambda }_{i}^{*}(r)\) is the unknown NHPP density function depending on the relative position r. We assume that the NHPP density function \({\lambda }_{i}^{*}(r)\) is decomposed as follows

where \({c}_{i}\), the total read depth for the ith cell, calculated as the summation of the total read counts of the gene of focus within the cell, is used for normalization purpose and for addressing the over-dispersion across cells (Supplementary Note 2); \(s\left(r\right)=2\pi r\) is another normalization term to adjust for the area of the annular region between r and \(r+\Delta r\) (the annular area between r and \(r+\Delta r\) is \(\pi {\left(r+\Delta r\right)}^{2}-\pi {r}^{2}=2\pi r\Delta r+\pi {\left(\Delta r\right)}^{2}=2\pi r\Delta r+o(\Delta (r))\); Supplementary Note 3); \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is the key term of interest—the subcellular spatial expression intensity function that captures the subcellular spatial expression pattern along the cellular radius; and \({\epsilon }_{i}\left(r\right)\) is the random effects term that models additional over-dispersion across cells not accounted for by the total read depth \({c}_{i}\) and is assumed to follow a normal distribution \({\epsilon }_{i}\left(r\right) \sim N[0,{\sigma }_{\epsilon }(r)]\), with \({\sigma }_{\epsilon }(r)\) being an unknown variance parameter to be estimated from the data. Importantly, we enforce the non-negativity of the density function \({\lambda }_{i}^{*}(r)\) by applying a ReLU operation within the inference algorithm (Supplementary Note 4) and constraining the two parameters associated with \({\lambda }_{i}(r)\) to be non-negative (details below).

With the above over-dispersed NHPP model, we can write down the joint likelihood of the subcellular gene expression across n cells as:

Note that we have assumed that the subcellular spatial expression intensity function \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is shared across cells, allowing us to borrow information across cells to enhance the detection of subcellular spatial expression patterns.

The intensity function \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is key for modeling the subcellular spatial expression pattern of the given gene. In particular, if a gene does not display subcellular spatial expression pattern and is instead uniformly distributed within the cells, then \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is expected to be a constant that is invariant to the relative position r. In contrast, if a gene displays subcellular spatial expression pattern, then \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is expected to vary as a function of the relative position r.

Therefore, in the above over-dispersed NHPP model, identifying genes that display subcellular spatial expression pattern within cells is equivalent to testing whether \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is a constant or not. The statistical power of such hypothesis test will inevitably vary depending on how the specified expression intensity function \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) matches the true underlying subcellular spatial expression pattern displayed by the gene of focus. For example, an intensity function enriched near zero will be particularly useful for detecting subcellular expression patterns that are also enriched in the nuclear, while an intensity function enriched near one will be particularly useful for detecting subcellular expression patterns that are also enriched near the cellular membrane. However, the true underlying subcellular spatial pattern for any gene is unfortunately unknown and may vary across genes. To ensure robust identification of subcellular spatial expression genes across various spatial patterns, we consider using a total of k = 22 different kernel functions \({\varphi }_{1}\left(r\right),\ldots,{\varphi }_{k}\left(r\right)\) inside the intensity function \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) to capture a wide variety of possible subcellular spatial expression patterns (Fig. S74c). In particular, each function is a Beta probability density function defined on the interval \([0,1]\), characterized by one of the 22 sets of shape parameters (Table S11) with a mode centering on 0, 0.1, 0.2, …, or 1. Note that, while we use these 22 kernel functions as default kernels in the present study, our method and software implementation can easily incorporate various numbers or types of intensity kernels as desired by the user.

For each kernel \(l=1,\ldots,k\) in turn, we model the intensity function in the form of \(\lambda \left(r\right)={\alpha }_{l}+{\beta }_{l}{\varphi }_{l}\left(r\right)\), where \({\alpha }_{l}\) is the nonnegative intercept parameter and \({\beta }_{l}\) is the nonnegative scaling parameter for the lth kernel function. With the functional form of \(\lambda \left(r\right)\), we can test the null hypothesis \({H}_{0}:{\beta }_{l}=0\), that \(\lambda \left(r\right)\) is a constant. Rejecting the null hypothesis allows us to detect genes that display subcellular spatial expression patterns captured by the particular kernel. We perform inference and hypothesis test for each kernel in turn using a likelihood ratio test. In particular, we first maximize the log likelihood both under the null and under the alternative using a policy gradient approach (Supplementary Note 4) with PyTorch35. Afterwards, we obtain the corresponding P value asymptotically based on an equal mixture of two chi-square distributions with degrees of freedom being zero and one36. Afterwards, we combine the k different P values calculated using different kernels into a single P value using the Cauchy combination rule37,38. Specifically, we convert each of the k P values into a Cauchy statistic, aggregate the k Cauchy statistics through summation, and convert the summation back to a single P value based on the standard Cauchy distribution. The Cauchy rule takes advantage of the fact that a combination of Cauchy random variables also follows a Cauchy distribution regardless of whether these random variables are correlated or not. Therefore, the Cauchy combination rule allows us to effectively combine multiple potentially correlated P values into a single P value for every gene. Finally, we control FDR across genes using the Benjamini–Yekutieli procedure, which is effective for arbitrary dependency among test statistics. We used an FDR cutoff of 0.05 for declaring significance.

Estimation of the subcellular spatial expression pattern with ELLA

While the primary focus of ELLA is on hypothesis testing, it can also be used to estimate the subcellular spatial expression pattern for the detected genes. Specifically, for gene g we can first obtain the k estimated intensity functions for each of the k kernel functions as

where \({\hat{\alpha }}_{l}\) and \({\hat{\beta }}_{l}\) are the estimates for the corresponding parameters. Because each of the k estimated intensity functions captures a particular aspect of the overall subcellular spatial expression intensity function \(\lambda (r)\), we estimate \(\lambda (r)\) with a weighted combination of the estimated intensity functions in the form of

where \({w}_{l}\) is the weight for the lth intensity function with \({\sum }_{l=1}^{k}{w}_{l}=1\). The weights can be derived based on Bayesian model averaging39. In particular, we denote the model with lth kernel function as \({M}_{l}\) and denote the data as D. The posterior distribution for \(\lambda (r)\) is in the form of: \(P\left(\lambda \left(r\right),|,D\right)={\sum }_{l=1}^{k}P(\lambda (r)|{M}_{l},D)P({M}_{l}{|D})\), with the posterior mean estimate being \(\hat{\lambda }\left(r\right)={\mathbb{E}}\left[P(\lambda \left(r\right)|D)\right]={\sum }_{l=1}^{k}{\mathbb{E}}\left[P\left(\lambda \left(r\right)|{M}_{l},D\right)\right]P\left({M}_{l}|D\right)={\sum }_{l=1}^{k}{\hat{\lambda }}_{l}(r)P({M}_{l}{|D})\). Therefore, the weights are in the form

where the last equation holds due to the equal prior assumption on each model, with \(P({M}_{j})=1/k\) \(\left(j=1,\ldots,k \right)\). And \({\sum }_{l=1}^{k}{w}_{l}={\sum }_{l=1}^{k}\frac{P({D|}{M}_{l})}{{\sum }_{j=1}^{k}P({D|}{M}_{j})}=\frac{{\sum }_{l=1}^{k}P({D|}{M}_{l})}{{\sum }_{j=1}^{k}P({D|}{M}_{j})}=1\). We approximate \(P\left(D|{M}_{l}\right)\) with the maximized reward function (\(R(\tau,s)\)) to obtain the weights and subsequently \(\hat{\lambda }\left(r\right)\) (Supplementary Note 5).

ELLA is implemented in python, with an underlying PyTorch Adam for efficient CPU or GPU computation. The software ELLA, together with all analysis code used in the present study, are freely available at https://xiangzhou.github.io/software/.

Compared methods

We compared ELLA with three methods: (1) SPRAWL21, (2) Bento20, and (3) Wilcox. For both SPRAWL and Bento, we followed the tutorial on their corresponding GitHub pages and used the recommended default parameter settings.

SPRAWL takes RNA location information from subcellular multiplexed imaging datasets as inputs and does not explicitly require nuclear boundary or nuclear center information. SPRAWL examines one gene at a time and uses four localization metrics to capture four different types of subcellular spatial enrichment patterns that include peripheral, central, radial, and punctate. Specifically, the peripheral metric is used to identify peripheral/anti-peripheral patterns where the expression enrichment is either proximal or distal from the cell membrane. The central metric is used to identify central/anti-central patterns where the expression enrichment is either proximal or distal from the cell centroid. The radial metric is used to identify radial/anti-radial patterns where a gene is either aggregated or depleted in a sector of the cell. The punctate metric is used to identify punctate/anti-punctate patterns where a gene displays either self-colocalizing/self-aggregating or self-repulsion inside the cell. Because the radial and punctate metrics can only be computed for cells with no less than two expression counts, we had to filter out cells with less than two counts when analyzing a given gene for these two metrics. For each gene and each metric in turn, SPRAWL computes a score for every cell and averages them across cells in a particular cell type to obtain the per-cell-type score. SPRAWL then converted the per-cell-type score to a P value based on a standard normal distribution and used the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure for FDR control. We used an FDR threshold of 0.05 to obtain significant genes. SPRAWL is designed for working with multiple cells and does not support analysis on a single cell because it computes per-gene, per-cell localization scores (e.g., peripheral, central, radial, punctate scores) and aggregates these scores across cells of the same cell type to produce statistically meaningful results. SPRAWL uses the Lyapunov Central Limit Theorem to justify statistical testing, which requires estimating variance across multiple cells. As such, SPRAWL requires at least two cells to compute variance, and typically many more to obtain reliable variance estimates and corresponding P values.

Bento takes RNA location information from subcellular multiplexed imaging datasets as inputs and requires nuclear and cell boundaries as additional information. For each gene-cell pair in turn, Bento computes 13 spatial summary statistics and uses its RNAforest function, which consists of five independent pre-trained binary random forest classifiers, to produce five binary labels that classify gene expression patterns into one of the five patterns, including nuclear, nuclear edge, cytoplasmic, cell edge, and none. For each gene in the cell, we obtained the classification probability \({p}_{c}\) for each pattern c and used \(1-{p}_{c}\) to rank genes for the pattern, which allowed us to measure powers based on FDR in the simulations. However, due to its use of classification probability, it is not feasible to obtain FDR control in any real datasets with Bento.

Wilcox, a Wilcoxon rank sum test-based approach developed in the present study, detects genes that are differentially expressed between two subcellular regions: the nucleus and the cytoplasm. We focus on these two subcellular regions because we can extract the nuclear boundary and cell boundary in many spatial transcriptomics studies. To detect those genes, for each cell in turn, we first extracted the gene expression counts within the nucleus as well as the gene expression counts in the cytoplasm. We then normalized the two counts by the corresponding cellular areas for the two subcellular regions. Afterwards, we performed the Wilcoxon rank sum test across cells to detect genes that are differentially expressed between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

Simulations

We performed comprehensive simulations based on imaging data to evaluate the performance of ELLA and compare it with other methods. We did not perform simulations based on sequencing data, as neither SPARWL nor Bento can be applied to analyze these data. For simulations, we first extracted the cell boundaries of the embryonic fibroblast cells from the seqFISH+ data, calculated the minimal and maximal radius of each cell, obtained a list of 90 reasonably shaped cells with the ratio of minimal and maximal radius ≥0.3, and extracted their nuclear centers and boundaries. We then sampled with replacement n cells from these cells. For each cell in turn, we applied the same binning strategy used in ELLA preprocess to divide the cell from the center of the nucleus into 100 circular sectors of equal angle measure. In each sector v, we denote \({r}_{v}\) as the maximum distance between the center of the nucleus and the cellular boundary in the sector. We calculated the approximate area of the sector v as \(\pi {r}_{v}^{2}\)/100. We also denote \({\theta }_{v,\min }\) and \({\theta }_{v,\max }\) as the minimum and maximum angle measurements of the sector, respectively. For the alternative simulations, we further divided each circular sector into 25 annulus sectors with equal distances.