Abstract

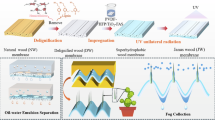

Janus fiber membranes enable directional liquid transport (DLT) for oil-water separation and moisture management, yet conventional pore-channel designs offer limited efficiency. Herein, we have developed a groundbreaking Janus nanofiber structure inspired by the structural characteristics of plant leaves, specifically the pore gradient and liquid transport channels within leaves. An innovative intermediate buffer layer composed of a three-dimensional helical nanofiber membrane was introduced to boost porosity and horizontal interconnectivity. A dopamine-controlled regulation mechanism synergistically optimized the pore structure and wettability of this layer. The resulting Janus membrane exhibits a remarkable unidirectional transport index (1250%), a high oil-water separation efficiency (98.92%), and an ultra-high flux (13860.77 L·m⁻²·h⁻¹). Its integration with textiles demonstrates superior moisture and thermal management, confirming its versatility for applications in oil-water separation, industrial wastewater treatment, and high-performance functional garments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Directional Liquid Transport (DLT) is an innovative technique harnessing the inherent asymmetry of porous materials to facilitate unidirectional, passive, and energy-free movement of liquid droplets within material systems1. This technology holds paramount importance across diverse fields, including environmental science, biomedical applications, and functional textiles2, where it finds widespread use in oil-water separation3, controlled drug release4, and advanced moisture management5. These asymmetric materials are typically designed at the micro- or nanoscale, possessing unique wettability and surface morphologies that efficiently direct liquid flow in specific directions. Notably, Janus fiber membranes, as a novel material, embody contrasting properties on opposing sides, thereby enabling unidirectional liquid transport6. Recently, electrospinning technology has garnered significant attention within the research community due to its versatility in producing porous Janus membranes with tailored wettability, high surface area, and micro- and nanoscale pore structures7. These electrospun membranes are often designed with bilayer or trilayer composite structures, primarily creating hydrophilic-hydrophobic gradients by stacking hydrophilic and hydrophobic fiber membranes or post-treatment techniques along the membrane thickness8,9,10. These designs have consistently demonstrated remarkable efficacy in enhancing liquid transport efficiency and gradient regulation.

Concurrently with advancements in modern manufacturing, researchers have harnessed inspiration from nature’s DLT phenomena to enhance Janus fiber membranes’ performance11,12. For example, Wang et al. developed fog collectors with mixed wettability surfaces and wedge-shaped protrusions by mimicking the structures of desert beetle backs and cactus spines, accelerating droplet formation and facilitating efficient transport13. Inspired by the shape and wettability gradients between the spindle knots and joints of spider silk, Liu et al. developed a biomimetic nanofiber membrane for efficient water collection by utilizing electrospinning and fluid coating14. Cheng et al. developed Janus interface dressings, mimicking lotus leaves’ asymmetric wettability, to facilitate wound exudate drainage15. These studies emphasize optimizing Janus membranes through asymmetric wettability while acknowledging that pore size and porosity critically influence water absorption. Consequently, researchers have devised multiscale Janus fiber membrane structures, fine-tuning pore architecture and integrating asymmetric wettability designs. Drawing inspiration from vascular plants’ sophisticated multiscale pore architecture that enhances transpiration, Ding et al. developed a moisture-wicking Murray membrane fabric with multi-branched macro, micro, and sub-micro pore sizes to optimize internal hydraulic conductivity and minimize transport resistance, enabling effective antigravity directional liquid transport16. Ji et al. furthered this progress by tuning nanofiber diameters through solution conductivity and spray conditions, integrating them with a hydrophilic non-woven layer to yield an efficient microfiltration composite nanofiber membrane featuring a pore size gradient and asymmetric wettability17. Yin et al. inspired by tree roots and stems, employed electrospinning to create radial-oriented and multiscale adjustable nanofiber membranes for advanced water management and wound healing applications12. Nature’s hierarchical structures and asymmetrical wettability have sparked new ideas for developing DLT Janus fiber membranes capable of ultra-fast liquid manipulation. While pore structure design has advanced, studies predominantly focused on pore size gradient optimization through fiber diameter adjustments. However, the impact of fiber structural design on porous channel optimization has not been thoroughly examined.

The helical structures arising from diverse contraction or expansion phenomena exemplify nature’s most captivating three-dimensional forms, spanning from the microscopic intricacies of DNA, bacterial flagella, and viral capsids to the macroscopic grandeur of seed pods, plant vascular systems, and tendrils18,19. These structures empower organisms to execute vital functions, encompassing genetic storage, nutrition acquisition, self-defense, and fluid transportation. Enthused by these structural-functional harmonies, researchers have incorporated helical geometries into fiber fabrication, yielding functional materials adorned with intricate three-dimensional helical fiber structures20. Compared to other methods such as chemical assembly, 3D printing, and microfluidic spinning, side-by-side electrospinning emerges as a simplistic yet potent method, utilizing eccentric nozzles to combine polymers with different mechanical properties and shrinkage rates21. Chen et al. demonstrated this by preparing thermoplastic polyurethane/aramid (TPU/Nomex) helical nanofibers (HNFs) through modifications to the off-center electrospinning apparatus22. Similarly, Yoon et al. obtained HNFs composed of polyvinylpyrrolidone/polyethylene oxide (PVP/PEO) and TPU by controlling solvent vapor pressure and polymer solution conductivity23. Wu et al. further reported the asymmetric shrinkage effect between cellulose acetate (CA) and TPU during the electrospinning process, harnessing their inherent viscoelastic differences to generate HNFs via side-by-side technology, underscoring the versatility and efficiency of this approach24. The formation of these HNFs stems from the disparities in shrinkage rates, fueled by variations in electrostatic forces, solvent systems, and the intrinsic nature of the constituent polymers during side-by-side electrospinning. Based on the above research results, helical fiber structures have proven effective in enhancing the porosity of fiber membranes. Hu et al. notably fabricated a photodynamic antibacterial membrane by integrating an antibacterial agent into CA/TPU HNF membranes, leveraging the higher specific surface area and porosity inherent to the helical structure to amplify light absorption and antibacterial efficacy25. Crucially, the introduction of helical fibers, which naturally intertwine to form fluffy, porous textures, presents a novel approach to designing porous channels in functional materials. This augments overall elasticity, flexibility, and porosity and enables efficient transport mechanisms. Recent research highlights the ability of nanofibers with layered helical structures to mimic xylem vessels, generating axial negative pressure as water ascends26. This facilitates swift, capillary-driven transportation of water and nutrients from roots to leaves. In contrast, the helical nanofiber-induced pore channels facilitate nearly frictionless water movement, enabling remarkable long-distance, anti-gravity water transport in vascular plants.

In this work, inspired by the structural properties of plant leaves during transpiration, we focused on simulating the pore gradient and the role of liquid transport channels within leaves. We introduced a groundbreaking Janus nanofibrous structure integrating longitudinal channels and horizontal networks to amplify liquid transportation efficiency. This innovative design features a gradient porous structure, constructed via layer-by-layer deposition, comprising a hydrophilic-underwater oleophobic Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) layer, a hydrophobic-underwater oleophilic TPU2 layer, and a middle HNF buffer layer enriched with helical CA/TPU1 nanofibers (the trilayer membrane is termed as PHT membrane). The helical fibers, uniquely achieved through hydrophilic PDA surface modification between polymer components, represent a pioneering approach to directional liquid transportation. Notably, to our knowledge, this integrated structure represents the first of its kind. The pore channels in the fiber membrane’s upper, middle, and lower layers generate negative pressure in the thickness direction through asymmetric wettability and porosity, forming an efficient longitudinal water transport path. The horizontal interconnection network of the intermediate buffer absorbing layer effectively reduces the gravitational resistance, further promotes the discharge of water, and achieves more efficient liquid transport. Therefore, this synergy between longitudinal and horizontal channels in the Janus structure significantly enhances liquid transportation efficiency, compared with the wettability gradient Janus membrane. Results show that the PDA-modified three-dimensional helical structure reduces the effective diameter of capillary channels and forms interconnected cellular pathways rather than just vertical porous pathways with straight fibers. This configuration can promote capillary rise, boost moisture absorption by mitigating gravity resistance, and ultimately optimize the DLT performance of Janus fiber membranes. This biomimetic Janus nanofibrous structure with helical nanofibers demonstrates significant potential for application in industrial wastewater treatment, marine oil spill cleanup, and high-end functional garments.

Results

Design of HNFs and biomimetic PHT Janus fiber membranes

Plant leaves form efficient water transport and vapor diffusion channels during transpiration through the complex pore structures between the upper and lower epidermis, palisade tissue, and spongy layer (Fig. 1a). Although the leaf does not conduct direct directional liquid transport, it achieves anti-gravity water transport from the root to the leaf through transpiration pull and a pore network while promoting water vapor diffusion and gas exchange through air gaps (within the palisade tissue and spongy layer) inside the leaf. This multi-level pore structure supports the longitudinal transport of water (from root to leaf) and facilitates the horizontal distribution of water via lateral pores, ensuring the plant’s water balance during drought conditions. Inspired by this natural phenomenon, this study designed an innovative Janus nanofiber membrane that mimics the transpiration mechanism of plant leaves by utilizing pore gradients and liquid transport channels. This three-layer structure biomimics the upper epidermis, palisade tissue/spongy layer, and lower epidermis of a leaf, forming an efficient directional liquid transport pathway (Fig. 1b) through a network of interconnected longitudinal and lateral pores. The lateral interconnecting network pores are developed into a helical nanofiber membrane (HNF membrane) with a three-dimensional interconnected network by utilizing the difference in elasticity between two polymers. Based on the fabrication principles of helical fibers mentioned above, we selected TPU and CA to prove the concept. It is worth noting that TPU and CA are not the only choices. Other materials satisfying the fabrication principles can be applied as well. With TPU exhibiting superior stretchability over CA, we employed a side-by-side electrospinning setup equipped with an off-centered core-shell spinneret to generate TPU/CA helical fibers (Fig. S1). The side-by-side structure was observed in a single helical fiber, as shown in Fig. S2. Upon solidification, TPU with more significant shrinkage imparted a helical nanofiber morphology, enhancing the membrane’s porosity and horizontal interconnectivity (Fig. 1c). To refine the helical structure, hydrophilic PDA was introduced to modulate the TPU-CA interfacial dynamics. Subsequently, hydrophilic-underwater oleophobic PAN nanofibers and hydrophobic-underwater oleophilic TPU nanofibers were electrospun onto opposing surfaces of the HNF substrate, yielding the biomimetic PHT Janus fiber membrane. As exhibited in Fig. 1d, the cross-sectional SEM image of the three-layer fiber membrane shows that the three layers are tightly combined in the interfacial region with good physical bonding between the corresponding layers, each tailored for a specific function. The three-layer fiber structure (with the top and bottom surface structures shown in Fig. 1e) forms a pore gradient. The membrane efficiently pumps water from the hydrophobic layer to the hydrophilic layer by leveraging wettability and pore size gradients. The water is then continuously propelled upwards by wicking action. The photograph of the as-fabricated PHT membrane is displayed in Fig. 1f. Figure 1g, h shows good directional water transport properties by moisture management tester (MMT) tests that water is transported from the hydrophobic side to the hydrophilic side, while reverse osmosis is prevented. It is also verified with the visible stain in Fig. 1i that the magenta-stained water drop cannot be transported from the hydrophilic side to the hydrophilic side.

a The porosity gradient and liquid transport channels within plant leaves achieve water transport and vapor diffusion through the complex pore structures between the upper and lower epidermis, palisade tissue, and spongy layer. This multi-layered pore structure supports longitudinal water transport (from roots to leaves) and enables horizontal distribution through transverse pores, ensuring water balance for plants in arid environments. b Schematic diagram of the biomimetic structure of the PHT-Janus membrane, utilizing longitudinal channels and a horizontally interconnected pore network to construct efficient liquid directional transport pathways. The horizontally interconnected pore network is constructed as a buffer-absorbing layer of helical nanofibers. c SEM image showing the spongy structure of the HINF membrane, forming horizontally interconnected channels similar to the palisade tissue and spongy layer. d The whole cross-section of the PHT Janus membrane. e The magnified cross-section of the PAN hydrophobic layer and the cross-section of the TPU hydrophilic layer. f Photograph of the PHT-X Janus fiber membrane fabricated using electrospinning technology. Water content on the top and bottom surfaces when water droplets are placed on the top surface of the PHT-1 Janus fiber membrane in two water transportation modes: hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic mode (g) and hydrophilic-to-hydrophobic mode (h), with the inset showing water distribution maps (blue indicates wet, white indicates dry). i The diffusion behavior of water droplets on the hydrophobic and hydrophilic sides shows that when on the hydrophobic side, water can penetrate through the fiber membrane and spread on the hydrophilic side; however, on the hydrophilic side, wsater droplets only spread on the surface, while the hydrophobic side remains dry.

Morphology and structure characterizations of HNF membranes

The molecular interactions between CA and TPU were further confirmed by density functional theory (DFT) (Fig. 2a and Fig. S4). Through comparing the different intramolecular interaction patterns between CA and TPU, as well as CA@PDA and TPU, it was found that the -OH groups in CA molecules form strong interfacial hydrogen bonds with the -C = O groups on TPU chains, with a bond length of 1.876 Å and binding energy of −0.405 eV. Before preparing HNF, PDA was premixed uniformly in CA solution for electrospinning, where the -OH groups in CA form stable intramolecular hydrogen bonds with the -C = O groups in PDA. Additionally, during the preparation of HNF, the -NH groups in PDA interact strongly with the -C = O groups in TPU, resulting in an interfacial hydrogen bond length of 1.796 Å and a binding energy further reduced to −0.537 eV, which is stronger than the bonding strength of CA and TPU. In this way, we do not necessarily consider the slippage between CA and PDA because they are surrounded by each other in the premixing. These results indicate that introducing PDA effectively enhances the interfacial hydrogen bonding interactions in the CA-TPU system and significantly improves the system’s electrostatic potential stability. The molecular interactions among CA, PDA and TPU were further confirmed by molecular dynamic (MD) simulations (Fig. S5). Comparing the radial distribution functions (RDFs) of O atoms on CA chains next to the -NH groups in TPU (N–H---O) and the -OH groups in CA next to the O atoms in TPU (O–H---O), O–H---O RDF showed an obviously higher value at a shorter distance, confirming that the C = O bonds on TPU would preferably bond to the -OH groups on CA. In CA/PDA/TPU, the RDF of O-H---O on CA/PDA and N-H---O on PDA/TPU had higher values with shorter distance, indicating stronger bonding interactions. All these RDF results were consistent with the DFT results. The morphology and structural characteristics of HNF membranes are shown in Fig. 2b–d, showing the SEM images of HNF-X films with different PDA contents (0, 2, 4 wt.%) (Fig. S6a–f for SEM images with PDA contents of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 wt.%). The corresponding fiber diameter distribution is shown in Fig. S7a–f. HNF-0 membrane exhibits an irregularly coiled fiber morphology with an uneven distribution of fiber diameter (Fig. 2a and Fig. S7a). However, as PDA content increases, fibers evolve into a regular helical shape with uniform diameters, particularly evident in HNF-1 and HNF-2 membranes (Fig. S6c and Fig. 2b). This is mainly attributed to the ability of PDA to form adequate interfacial adhesion between CA and TPU1, which enhances the interface bonding between the two in the side-by-side spinning process27. However, excessive PDA (≥3wt.%) hampers fiber elongation and contraction, reducing helical fiber formation (Fig. S6e and Fig. 2c). Specifically, at 4 wt.% PDA, fibers predominantly display curved rather than regular helical structures. In summary, optimal PDA contents promote regular helical nanofiber formation by bolstering interfacial adhesion, whereas excessively low or high concentrations impede this structural development.

a Binding schematic of CA and TPU chains with/without PDA molecules. SEM images of HNF-X membranes: b HNF-0; c HNF-2; d HNF-4. e Double-layer strip model of side-by-side electrospun HNF-X. (e-i) Fiber curved/helical structure without adding PDA content. (e-ii) More helical structure with the addition of an appropriate amount of PDA. (e-iii) Curved/straight structure with excessive PDA content. f Curves of helical curvature K and pitch H versus the content of PDA. Error bars in (f) represent standard deviations, n = 100 independent measurements. g FTIR spectra. h Contact angle. Error bars in (h) represent standard deviations, n = 3 independent samples.

The reasons for the influence of PDA content on the helical structure of HNF-X membranes can be explained by comparing the formation of helical structure in side-by-side electrospinning process to the schematic diagram of double-layer prestressed rubber strip in concept, as shown in Fig. 2e. Here, the composite jet is envisioned as a composite strip comprising two intimately juxtaposed rubber-like layers of CA and TPU1 (Fig. 2e–i). The inherent material disparities between these polymers lead to differential deformations under electric field forces, resulting in varied longitudinal stresses and subsequent stretching (\(\Delta {{\rm{\lambda }}}_{1}\)). The CA and TPU1 layers remain permanently bonded via interfacial hydrogen bonding, precluding interfacial mixing. Disregarding component intermixing during spinning, the interface between these rubber layers experiences shear stresses induced by electric field stretching28, leading to spontaneous bending and an intrinsic curvature (K). Notably, the viscous resistance, akin to the stress level, necessitates the presence of hydrogen bonding between layers. Due to the high adhesion of catechol and amino functional groups, the active groups of PDA in the modified HNF-X membrane system increase the formation of hydrogen bonds. In the HNF-X membrane system, the stretching of the composite jet within the electric field harnesses the PDA’s bridge effect to amplify viscous resistance at the interface. This reinforcement fosters tighter integration between the CA and TPU1 layers, enhancing their longitudinal deformation (\(\Delta {{\rm{\lambda }}}_{2}\), Fig. 2e-ii), a pivotal factor in efficiently producing two-component helical fibers29. However, excessive PDA content paradoxically diminishes the deformation disparity (\(\Delta {{\rm{\lambda }}}_{3}\)) between the layers by strengthening their bond, thereby reducing shear stresses essential for bending and helical structure formation (Fig. 2e (iii)).

In addition, the helical structure of HNF-X fibers prepared with different PDA contents was analyzed. Figure 2f shows spiral curvature (K) and pitch (H) measurements as a function of PDA concentration. As PDA concentration increases, K initially rises and declines, while H exhibits an inverse trend. This aligns with SEM findings, indicating that HNF-2, prepared with 2 wt.% PDA, possesses the most compact helical structure, with a minimum H of 1.1 μm and maximum K of 1.3. Notably, the helical fiber structure directly influences the pore size and porosity of the membranes. As depicted in Fig. S8–S9, an increase in helical curvature coincides with a decrease in pore diameter and a rise in porosity, specifically at 2 wt.% PDA, HNF-2 achieves a K of 1.3 and a peak porosity of 87.5%. Furthermore, adjusting PDA content effectively turns the membrane’s average pore size, initially expanding and then contracting from 62.7 μm (HNF-0) to a minimum of 48.1 μm (HNF-2), after expanding again to 65.4 μm (HNF-4). Thus, precise modulation of fiber helical structure through PDA content offers a viable strategy for tailoring three-dimensional network pore channels in HNF membranes, significantly impacting their pore size and porosity.

After electrospinning, the microstructural properties of the HNFs were thoroughly investigated using XRD and FTIR analyses. The XRD patterns (Fig. S10) reveal that HNF-0 exhibits two broad peaks at 2θ = 9.0° and 19.1°, attributed to the 101 crystallographic plane of CA and the hard segment crystal peak of TPU130. Notably, the inclusion of PDA nanoparticles in HNF-X membranes did not disrupt the crystallization process of the CA-TPU1 nanofiber composites, as evidenced by the preservation of these peaks within the same 2θ range. Instead, PDA acted primarily as an interfacial adhesion enhancer.

The FTIR analysis (Fig. 2g) of HNF-0 reveals characteristic absorption bands at 3400, 1725, 1610, and 1250 cm−1, associated with the stretching vibrations of -NH, C = O in TPU1 and -C = O, -O- in CA, respectively24. With PDA addition, the absorption peaks at the 3700–3500 cm−1 region became sharper and denser, indicating an increase in free hydroxyl groups likely due to PDA’s hydroxyl groups and its promotion of hydrogen bonding network rearrangement (Fig. S11). Additionally, the presence of PDA is confirmed by the intensifying absorption within 2360 cm−1 and 2340 cm−1 characteristic of its benzene ring31. Notably, the absorption bands at 3400 cm−1 and 1610 cm−1 diminish in PDA-modified HNF-X, attributed to PDA’s high surface adhesion and reactivity, which facilitate interfacial bonding between CA and TPU1 via hydrogen bonding formation between PDA’s catechol and amino groups with CA’s ester and TPU1’s amino groups, respectively32. This interfacial strengthening plays a pivotal role in shaping helical fibers. Furthermore, PDA significantly improves the wettability of the fiber membranes (Fig. 2h) and increasing PDA content leads to a progressive decrease in contact angle mainly due to the abundant hydroxyl and amino functional groups in PDA molecules. These functional groups formed many hydrogen bonds on the surface of HNF-X membranes, which significantly improved the wettability of HNF-X membranes, indicating that PDA enhanced the hydrophilicity of HNF-X membranes.

Water permeation behavior measurement

We conducted water permeation tests to assess the improvement in water transport efficiency of the PHT membrane. Figure 3a is a panoramic view of a three-layer fiber membrane constructed by layer-by-layer deposition. Figure 3b illustrates the water transport pathway within the PHT membrane. The membrane efficiently pumps water from the hydrophobic to the hydrophilic layer by leveraging wettability and pore size gradients. Notably, including the HFN membrane as a buffer absorption layer facilitates the absorption and infiltration of water into its horizontally interconnected pores, overcoming gravity resistance that straight nanofiber longitudinal channels might encounter. Utilizing dynamic water contact angle (WCA) analysis, we evaluated the wettability of various membranes, including TPU, PAN, and PHT membranes with varied PDA-modified buffer layers (Fig. 3c). Notably, the PAN membrane rapidly absorbed a water droplet, reducing WCA from 60.5° to 0° in 2.3 s. Conversely, HNF-X membranes exhibited accelerated absorption rates with increasing PDA content, with spreading times ranging from 12.5 to 3.4 s, though still slower than PAN. The TPU2 membrane remained hydrophobic, maintaining a WCA of 132°. These findings confirm the successful fabrication of PHT-X Janus fiber membranes featuring gradient wettability and pore structures (Fisg. S7, S8, and Fig. S12). Further analysis of the DLT performance, focusing on the influence of helical structure on the HNF-X intermediate layer, revealed enhanced reverse hydrostatic pressure (PAN to TPU2) and reduced forward pressure (TPU2 to PAN) compared to bilayer PAN/TPU2 membranes (Fig. 3d). Additionally, with the increase of the regularity of spiral structure in PHT-X Janus membranes, the positive static pressure decreases. The reverse static pressure of PHT-X Janus fiber membranes increases with increased hydrophilicity of HNF-X fiber membranes. Remarkably, incorporating the HNF-2 membrane as a central buffer layer facilitated effortless water passage forward, requiring a minimal hydrostatic pressure of 6.5 cm H2O (0.6 kPa). This underscores the pivotal role of horizontally interconnected cellular networks formed by regular helical structures in enhancing water transport. Conversely, water flow in the reverse direction encountered significant resistance, necessitating a hydrostatic pressure of at least 23.1 cm H2O (2.0 kPa), attributed to the hydrophilic layer’s smaller pores and hydrophilic nature, effectively barricading water passage.

a Schematic diagram of PHT-X Janus fiber membrane. b The water ascent channels path and gradient aperture of the PHT Janus fiber membrane generating higher capillary forces, spontaneously absorbing water upward. c The contact angle wetting time change of each PHT-X fiber membrane. d Anisotropic water breakthrough pressures on both sides of the PHT-X Janus fiber membranes and the control PAN/TPU2 fiber membranes. Error bars in (d) represent standard deviations, n = 3 independent samples. e When the water droplets are on the hydrophobic side (TPU) of the PHT-2 samples (hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic mode), the relative water content of the top and bottom surfaces of the sample. f Images of water distribution at the top and bottom of the PHT-X Janus fiber membranes and the control PAN/TPU2 membrane when water droplets were on the hydrophobic side (TPU) of the sample (hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic mode).

Furthermore, utilizing a moisture management tester, we quantified the DLT capacity of PAN/TPU2 bilayer and PHT-X Janus fiber membranes. The droplet transport performance of the hydrophobic side of PHT-X fiber membranes is shown in Fig. S13a–g. The superior DLT performance of PHT-X Janus membranes was tunable by modulating the helical structure regularity in the buffer layer. Notably, the unidirectional liquid transfer R-values reached 806% to 1250%, peaking at 1250% with optimal structure. As is shown in Fig. 3e, when HNF-2 served as the buffer layer, water content on both sides surged initially (0–20 s) upon droplet contact with the hydrophobic surface. Swiftly, the middle layer drew water to the adjacent hydrophilic layer, fueled by the wetting and pore gradients’ pumping force. Simultaneously, the PAN membrane’s capillary force accelerated surface water diffusion33. This synergy yielded a DLT with an R-value 2.4 times that of the bilayer PAN/TPU2 (514%), spanning 20–120 s. This behavior is also confirmed by the water distribution images of the top hydrophobic and bottom hydrophilic surfaces (Fig. 3f) during the moisture management test, with blue and white tones indicating wet and dry areas, respectively. Therefore, we can conclude that the helical structure can help with DLT properties by comparing the PAN/TPU2 bilayer and PHT membranes. Better DLT capacities can be achieved with a more regular helical structure.

At the same time, we tested the transport performance of water droplets from the hydrophilic side of the PHT-X fiber membranes and compared the DLT and anti-reverse osmosis properties, as shown in Fig. S14a–g. In the MMT results of the PAN/TPU2 fiber membrane, some water droplets permeate from the top hydrophilic layer to the bottom hydrophobic layer, and the R is −975%. In contrast, Fig. S14b–g shows the osmosis properties of PHT-X fiber membranes at different HNF-X levels. As the helical structure of the HNF-X fiber membrane gradually decreases and its hydrophilicity increases, the anti-reverse osmosis properties of PHT-X fiber membranes are significantly improved. The water content of the hydrophobic side on the bottom surface is gradually close to zero. R increased from −1050 to −1912%. This indicates that the structural optimization and good hydrophilicity of the HNF-X layer significantly enhance the anti-osmosis ability of the PHT-X fiber film, ensuring that water droplets only travel in a single direction.

DLT mechanism

In practical scenarios, liquids are efficiently extracted from the skin-facing hydrophobic TPU2 layer of the PHT-2, traversing the buffer layer to the outer hydrophilic PAN layer, where they finally evaporate. To simplify comprehension of this directional transport, we have constructed a visual model (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Movie 1). Upon contact with the magenta-dyed hydrophobic surface, the droplet is promptly drawn through the buffer layer and dispersed into the PAN layer, completing the transfer within 3 seconds. Conversely, a droplet on the hydrophilic side rapidly spreads within this layer, forming a larger droplet circle, yet fails to penetrate the hydrophobic layer (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Movie 2). We conducted antigravity-driven experiments to verify the continuous, directional water transport prowess of PHT-X Janus fiber membranes (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Movie 3). The antigravity phenomenon unfolded in five stages: contact, pumping, transport, spreading and evaporation. With the hydrophobic TPU2 layer facing downwards, droplets ascended to make contact. Upon touching the TPU2 layer, water was swiftly pumped into the buffer layer. This rapid transfer stems from the interplay between the wetting gradient and porosity structure disparities between layers, generating a driving force (FW1) and capillary pressure difference (∆P) that efficiently channels water into the inter-fiber capillary channels of the buffer layer. The wetting driving force \({F}_{W1}\) 34 and \(\Delta P\) 35 are represented by Eqs. (1) and (2),

a Water droplet on the hydrophobic TPU2 layer permeating through the conductive PHT-2. b Water droplets on the hydrophilic PAN layer diffusing through the layer. c Antigravity water transport through the PHT-2, where the water moves upward from the hydrophobic layer at the bottom to the hydrophilic layer at the top in hydrophilic-to-hydrophobic mode.

In Eq. (1) \({\gamma }_{{LV}}\) is the surface tension between the liquid and the material surface, \(\theta \left(x\right)\) is the contact angle of the liquid at the position, \({\theta }_{0}\) is the contact angle of the liquid when it is far away from any surface, and the integration region [A, B] represents the change of the liquid’s position between the hydrophobic layer and the buffer layer. In Eq. (2), \({P}_{1}\) and \({P}_{2}\) are the Laplace pressures of the hydrophobic and buffer absorbing layers, respectively, γ denotes the interfacial tension between the liquid and gas phases, \({\theta }_{1}\) and \({\theta }_{2}\) are the WCAs of the hydrophobic and buffer absorbing layers, respectively, as well as \({D}_{1}\) and \({D}_{2}\) refer to their respective capillary channel diameters. Notably, the capillary pressure difference (\(\Delta P\)) between the two layers and the capillary force in the buffer absorbing layer (\({F}_{c1}\)) enable water to overcome the hydrophobic viscous resistance (\({F}_{r}\)) and conduct upward from the hydrophobic side to the transport layer under low water velocity and low G conditions. The capillary force in the buffer absorbing layer \({F}_{c1}\) 36 and the hydrophobic viscous resistance \({F}_{r}\) 37 can be expressed by Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively:

The \({d}_{2}\) in Eq. (7) represents the diameter of the three-phase contact line in the buffer absorbing layer and the capillary force is derived from the Laplace pressure \({P}_{2}\), which is opposite to the pore radius. The \({d}_{1}\) in Eq. (8) is the diameter of the three-phase contact line in the hydrophobic layer. \(2\alpha\) is the conical conicity formed by the difference in pore size between the hydrophobic layer and the buffer absorbing layer. The capillary force (\({F}_{c1}\)) generated by the horizontal interconnected network channels in the buffer absorbing layer promotes the diffusion of water within the buffer layer, reducing the gravitational load on the upward transport of water. Additionally, the capillary pressure difference in the PHT-X Janus fiber membrane, where \({P}_{2}\) is greater than \({P}_{1}\), further enhances the continuous upward pumping of water. Similarly, the interfacial Laplace pressure difference (\(\Delta {P}_{2}\)) between the buffer absorbing layer and the hydrophilic PAN layer (\(\Delta {P}_{2}={{|P}}_{3}-{P}_{2}|\), where \({P}_{3}\) is the Laplace pressure of the hydrophilic layer) is similarly oriented upward to continue the extraction of water from the buffer absorbing layer to the hydrophilic PAN layer. Once the water contacts the hydrophilic PAN layer, the main driving force immediately tunes into a capillary force \({F}_{c2}\) (\({F}_{c2}=\gamma \pi {d}_{3}\cos {\theta }_{3}\), where \({d}_{3}\) is the diameter of the three-phase contact line in the hydrophilic layer, and \({\theta }_{3}\) is the WCA of the hydrophilic layer), which induces the droplets to rapidly diffuse and evaporate on its surface. This mechanism is consistent with the prediction of Murray’s law that a multiscale network of pore interconnections in a porous medium maximizes the transport rate of a finite liquid and minimizes the transport resistance38. As a result, the combined force applied vertically to the liquid always remains upward, resulting in unidirectional and irreversible transport of the liquid as it moves. These results indicate that the three-layer fabric with gradient wettability and pore structure effectively facilitates the directional transport of the liquid. The horizontally interconnected network channels in the intermediate layer serve as a buffer absorbing layer and reduce gravitational resistance, thereby aiding in the anti-gravity transport of the liquid.

PHT Janus membrane practical application demonstration

We demonstrate its potential for oil-water mixture treatment to bridge the gap between PHT membrane and practical use. Wettability is crucial for successful oil-water separation by fiber membranes39. Figure 5a reveals that PHT-X Janus membranes exhibit asymmetric wettability: the hydrophilic side is oleophobic (oil contact angles ranging from 113.3° to 133.3°). In contrast, the hydrophobic side is super-oleophilic (5.7° oil contact angle). In addition, the pre-wetted PHT-X Janus fiber membranes exhibit unique wetting behavior on both sides of the oil (take the PHT-2 Janus fiber film as an example). When a pre-wetted PHT-2 Janus membrane’s hydrophilic side encounters an acidic magenta-stained water droplet in oil, it swiftly absorbs the water (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Movie 4). Conversely, the pre-wetted hydrophobic side exhibits remarkable oil absorption and water rejection, even when submerged in oil (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Movie 5). These findings underscore the potential of PHT-X Janus membranes’ unique wettability for diverse oil-water separation applications. This asymmetry enables efficient separation, as evidenced by the membrane’s ability to block 50 g of Sudan III-stained hexane while allowing 50 mL of methylene blue-stained water to pass through rapidly (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Movie 6). Figure 5e shows separation efficiencies exceed 98% with fluxes up to 13227 L·m-2·h-1, peaking at 98.92 ± 0.18% and 13,860.77 ± 330.04 L m−2 h−1 for PHT-2. Notably, when dry PHT-X membranes with the hydrophobic side up encounter an n-hexane-water mixture, oil flow is initially hindered by viscosity but eventually permeates, highlighting the membrane’s versatility under varying conditions. This indicates that the membrane cannot block the oil in its dry state40. In addition, the PHT-2 Janus fiber membrane showed good separation stability (Fig. 5f). After 10 separations, the separation efficiency remained above 98%, and the separation flux was as high as 13231 L m−2 h−1, indicating excellent reusability.

a Underwater oil contact angle on the hydrophilic side of PHT-X Janus fiber membranes; the inset is oil droplet shape on the hydrophobic side, and all the samples had the same results. Error bars in a represent standard deviations, n = 3 independent samples. b Water collection behavior of the hydrophilic side of PHT-2 in oil. c Water rejection behavior of the hydrophobic side of PHT-2 for water in oil. d Oil-water separation device. e Separation efficiency and flux of PHT-X-Janus fiber membrane. Error bars in e represent standard deviations, n = 3 independent samples. f Separation efficiency and flux of PHT-2-Janus fiber membrane under different separation cycles. g Comparing the separation performance of the PHT-X membrane with that of the fabric/fiber membrane reported in the literature, PHT-X showed even higher throughput at a similar high separation efficiency.

Based on the DLT mechanism, the PHT-X Janus fiber membrane performs excellently in oil/water mixture separation. Due to the DLT characteristics of water, water first contacts the PHT-X Janus fiber membranes and quickly passes through, forming a water film on the surface of the membrane to block the passage of oil and achieve oil/water separation. Compared to previously reported fabric/fiber membranes (Fig. 5g, Table. S1), PHT-2 Janus fiber membranes demonstrate a better separation performance with even higher separation throughput at the similar high separation efficiency. This work provides a sustainable and efficient industrial wastewater treatment and Marine oil cleanup solution.

As shown in Fig. S15, with the addition of the PHT spongy layer, the maximum stresses of the membranes were improved at least 2.5 times, and the breakage strains were increased by 4 times, compared with PAN/TPU2. Besides, it is notable that the membranes with the buffer layer have a steady plateau stress, especially for the PTH-2 membrane, which is caused by the helical fibers to increase their stretchability, and it is vital for human wearables. Therefore, we conclude that the PHT-2 Janus fiber membrane exhibits better mechanical properties, demonstrating its potential for human sweat conditioning and heat management garments. We integrated the high-performing PHT-2 Janus fiber membrane with various conventional fabrics (KF, WF, and DLT-KF). This integration aimed to enhance moisture management efficiency and reduce body surface temperature. By incorporating a wettability gradient, we aimed to facilitate automatic sweat evacuation from the skin to the environment, fostering a dry and comfortable microclimate in hot, humid settings41. As depicted in Fig. 6a, b, we designed an advanced moisture-wicking and cooling garment utilizing the PHT-2 composite fabric. To assess the moisture management capabilities of these composites, we employed the moisture management tester method, utilizing the unidirectional transfer index (R-value) as a metric for moisture conductivity. The results in Fig. 6c reveal that the exceptional DLT properties of the PHT-2 membrane significantly boosted the moisture management performance of all tested fabrics. Notably, the R-values of the original fabrics KF, WF, and DLT-KF improved dramatically upon lamination with PHT-2. Specifically, KF/PHT-2, WF/PHT-2, and DLT-KF/PHT-2 achieved R-value enhancements of 13 times, 8 times, and 1 time, respectively. This remarkable improvement stems from the optimized pore structure and hydrophilicity gradient imparted by the PHT-2 membrane, ultimately enhancing the overall liquid management capabilities of the textile42. Fig. 6d shows the general enhancement effect of PHT-2 fiber membrane on the moisture management capability of various fabrics. By combining PHT-2 with KF of different materials and structures, the moisture permeability of the composite samples was evaluated by the inverted cup method. Results showed that the DLT properties of PHT-2 fiber membrane help improve the humidity management capability of these fabrics, especially for KF5, with a 59.2% increase. In addition, the breathability of the composite sample was also tested, and the results are shown in Fig. 6e. The breathability range of the composite sample is 34.56–91.74 mm/s, which shows not only good air mobility but also has specific wind resistance, showing its broad potential in a variety of applications.

a Application of PHT-2 laminated with fabrics on garments. b Demonstration of the moisture management capabilities of PTH-2 laminated with KF compounded with functional garments with moisture-wicking ability. c Moisture management capabilities of KF, WF, and DLT-KF laminated with PHT-2, evaluated by MMT tests and compared with three original fabrics, respectively. d The moisture permeability of PHT-2 combined with different types of KF and compared with the original fabric. e Breathability of PHT-2 after combination with different types of KF. Error bars in (c–e) represent standard deviations, n = 3 independent samples. f Infrared camera images of the three original fabrics and those laminated with PHT-2 covered with our wet skin. g Compared with the fabrics and fiber films with thermal regulation properties reported in the literature, the fabrics with composite PHT-2 films showed better cooling effects.

Beyond moisture management, thermal regulation is vital for textiles in real-world use. We evaluated thermal properties by measuring fabric surface temperatures at 100 seconds via infrared thermography. As Fig. 6f demonstrates, fabrics laminated with the PHT-2 Janus membrane exhibit lower temperatures than their unlaminated counterparts, confirming their ability to provide a cooling effect in hot environments. KF/PHT-2, WF/PHT-2, and DLT-KF/PHT-2 cover reduced fabric surface temperatures by 2.5 °C, 2.9 °C, and 3.3 °C, respectively, compared to their base fabrics. This cooling effect stems from the membrane’s efficient liquid transport, facilitating sweat evaporation and heat dissipation, lowering fabrics’ surface temperatures43. Thus, the PHT-2 Janus membrane boosts the fabric’s unidirectional liquid transport and realizes effective personal thermal management. Compared to previously reported fabrics and fiber membranes with thermal regulation (Fig. 6g, Table. S2), fabrics with PHT-2 films combined demonstrated superior cooling effects. Moreover, the PHT film had good lamination strength with fabrics demonstrated by the wear abrasion and laundry experiments (Figs. S16–S17). This research provides a new direction for developing functional garments suitable for high temperature and high humidity environments and has significant application value.

Discussion

In summary, we introduce a groundbreaking approach to manipulating the spiral architecture of electrospun nanofibers via PDA additive-driven physical modification. This method fosters robust hydrogen bonding between CA and TPU, yielding exceptional helical nanofibers with peak curvature and porosity at a 2% PDA concentration. We also introduce a novel DLT Janus nanofiber membrane inspired by the structural characteristics of plant leaves during transpiration, focusing on simulating pore gradients and liquid transport channels inside the leaves. The design combines the vertical channel with the horizontal network to achieve excellent water transfer efficiency. Based on Murray’s law and asymmetric wettability, this biomimetic design combines horizontal interconnections and vertical transport channels, enhancing negative pressure-driven transpiration while mitigating gravity resistance. Dynamic WCA and moisture management tests validate its superior water transport capabilities. The helical HNF membrane’s interconnected channels enhance porosity and expedite unidirectional liquid transfer from the TPU2 hydrophobic layer to the PAN hydrophilic layer, achieving a remarkable 1250% unidirectional transfer index (R)—a 2.4-fold improvement over straight-pore membranes, fostering a dry, comfortable microenvironment. Furthermore, the PHT-2 Janus membranes, leveraging their unique underwater oil wettability, exhibit a high oil-water separation efficiency of 98.92 ± 0.18% and a flux of 13,860.77 ± 330.04 L m−2 h−1 post-prewetting, underscoring their multifaceted potential. Additionally, it is crucial to emphasize the versatility of this biomimetic DLT Janus fiber membrane design, which seamlessly integrates with textile fabrics. By incorporating this membrane into textile layers, notable enhancements in humidity and thermal management can be realized. The DLT Janus fiber membranes hold immense potential in advancing industrial wastewater treatment, facilitating marine oil spill cleanups, and producing high-performance functional apparel. These insights pave the way for the innovative design and development of next-generation DLT Janus fiber membranes, ushering in a new era of material science.

Methods

Materials

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN; Mw = 150,000, density = 1.18 g cm−3) was purchased from Kaneka Corporation, Japan. Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU; 1190, Mw = 70,000, density = 1.12 g cm−3) was obtained from Wanhua Chemical Group Co., Ltd. Cellulose acetate powder (CA; acetyl content 39.8 wt.%, hydroxyl content 3.5 wt.%) and hydrochloric acid dopamine (DA; 98%) were purchased from Beijing Innochem Technology Co., Ltd. Lithium chloride (99%), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF; analytical grade), N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc; analytical grade), acetone (ACE; analytical grade), Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris; premium grade), hydrochloric acid (HCl; premium grade), 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (isooctane, 90%), isopropanol (analytical grade), methylene blue (≥82%), Sudan III dye (Mw = 352.39) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Acid fuchsine dye (Mw = 585.55, 99%) was purchased from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All reagents were used as received without further purification. Cotton plain weave fabric, cotton flat knit fabric, and commercial polyester-covered cotton DLT knit fabric were commercially sourced. Five types of fabrics were self-knitted using a Longxing computerized flat knitting machine (E14, Jiangsu Jinlong Technology Co., Ltd., China), including cotton pique knitted fabric (KF1), cotton double rib knitted fabric (KF2), viscose pique knitted fabric (KF3), viscose weft plain knitted fabric (KF4), and viscose double rib knitted fabric (KF5).

Preparations of HNF-X membranes and PHT-X Janus fiber membranes

The Tris-HCl buffer solution with a pH of 8.5 was prepared by dissolving 6.057 g of Tris in 147 mL of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid in a 1000 mL volumetric flask, then diluting to volume with deionized water. The prepared Tris-HCl buffer was used as the solvent for a 2 mg/mL DA solution. The solution was stirred until the DA powder was fully dissolved, and then the mixture reacted in an open container for 20 h. During this time, the transparent solution turned dark brown. The resulting solution was centrifuged at 715.52 × g for 15 min to separate the supernatant and the precipitation. This process was repeated three times to isolate the dark brown precipitate, and then the precipitation was freeze-dried to obtain PDA nanoparticles. CA powder with corresponding weight was added into the ionic solution composed of DMAc/ACE (volume ratio 1:2) and 1.2 wt.% LiCl, and magnetically stirred for 12 h to prepare CA solution with a concentration of 11 wt.%. Then, a series of CA solutions with different PDA contents (0, 0.5 wt.%, 1 wt.%, 2 wt.%, 3 wt.%, 4 wt.%) were prepared by adding a certain mass of PDA nanoparticles into a CA solution of 11 wt.% and dispersed with ultrasonic for 2 h at room temperature. On the other hand, TPU pellets of the corresponding mass were dissolved in DMF/ACE (volume ratio of 3:1) and magnetically stirred at room temperature for five hours to prepare 12 wt.% TPU1 solution and 23 wt.% TPU2 solution. The above-prepared solutions were loaded into the syringe respectively. A side-by-side electrospinning system with eccentric spinneret (TK602NL, Shanghai Anwan Technology Development Co., LTD., China) was employed for the spinning equipment (Fig. S1). Syringes containing 11 wt.% CA solution and 12 wt.%TPU1 solution were controlled by two propulsion pumps at a steady rate of 0.15 ml/h. A high DC voltage of 22 kV is applied at the off-core compound nozzle. The distance from the nozzle tip to the collection roll is 10 cm. Fig. S3 illustrates the morphology of helical nanofibers prepared under varying collection speeds and LiCl concentrations in the CA solution. When the LiCl concentration was 1.2 wt.%, and the collection speed was 0.56 × g, the yield of helical nanofibers increased significantly. Therefore, subsequent experiments were conducted under conditions of 1.2 wt.% LiCl concentration and 0.56 × g collection speed to prepare HNF.

Three-layer composite Janus fiber membranes containing HNF-X membranes with wetting gradient and pore gradient structures were prepared by sequential electrospinning. A specific mass of PAN powder was dissolved in DMAc to prepare a hydrophilic PAN solution with a concentration of 16 wt.% and loaded into a syringe for standing. The hydrophobic layer of the Janus fiber membrane was first prepared with TPU2 solution: a syringe containing TPU2 solution was connected to a 19 G spinneret tip, and 16 kV voltage was applied. Spinning was carried out at a feed rate of 1 ml/h for 20 min, keeping the distance from the tip of the spinneret to the collection roller at 10 cm and the collection speed at 2.25 × g. The hydrophobic TPU2 layer was applied onto a metal collection roller to laminate it with the HNF-X membranes of the intermediate buffer absorbing layer. The solution preparation and spinning parameter adjustments for the HNF-X membranes were as described above. The bilayer of fiber membranes was obtained on the collection roller after 8 h. Subsequently, the hydrophilic layer of PHT-X Janus fiber membranes was prepared with PAN solution, and the preparation process was similar to that of TPU2 fiber membrane, except that the spinneret size was 22 G and the spinning time was 6 h. Finally, the three-layered composite micro/nanofiber membranes PHT (PAN/HNF/TPU2) prepared as described above were placed in a vacuum oven for drying and were denoted as follows: PHT-X Janus fiber membranes (X represents the content of PDA as 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 wt.%). The ambient temperature and relative humidity during all the above spinning processes were 22 ± 2 °C and 80 ± 5%, respectively.

Theoretical simulation of intermolecular interactions between CA/PDA/TPU

The initial molecular system was constructed using Packmol by packing 60 chains of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), 60 chains of polydopamine (PDA), and 60 chains of polycarbonate (PCA), each with a degree of polymerization (DP) of 20, into a cubic simulation box with dimensions of 300 × 300 × 300 ų. To calculate the interfacial interactions of the components, the cubic simulation box is divided into two parts to initially place the two components. Following energy minimization, the system was gradually heated to 298.15 K and equilibrated for 1 ns in the NVT ensemble. Subsequently, isothermal-isobaric (NPT) equilibration was performed for 2 ns at 298.15 K and 1 bar. Production simulations were conducted for 500 ps in the canonical (NVT) ensemble. Temperature control was maintained using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat (coupling constant τ_T = 1.0 ps), while pressure regulation was achieved through the Parrinello-Rahman barostat (coupling constant τ_P = 5.0 ps). Bond constraints involving hydrogen atoms were implemented via the LINCS algorithm. Numerical integration of Newton’s equations of motion was performed using the Velocity-Verlet algorithm with a 2.0 fs timestep. Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 12 Å real-space cutoff. Van der Waals interactions were described by the Lennard-Jones potential, employing the Lorentz-Berthelot combining rules. A smooth energy switching function was applied between 10 Å (inner cutoff) and 12 Å (outer cutoff) to ensure continuous force transitions. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three spatial dimensions.

DFT calculation

DFT calculation including a long-range dispersion correction, as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (vasp 5.4.4), was employed to predict the interaction in CA/PDA/TPU. The exchange-correlation functional was represented with the GGA in the form of the Perdew- Burke-Ernzerhof functional. The projector-augmented wave method was used, and the cutoff energy was 500 eV. The energies were calculated to converge to the accuracy of 1.0 × 10−5 eV. The size of computational cell was 30 ×30 ×30 Å, with a k-point set of 2 × 2 × 2 during the calculations. The binding energy between any two materials among CA/PDA/TPU (indicating the interaction between them) was calculated to be Eb2 = Et - (E1 + E2), where Et is the energy of the supercell containing material 1 and material 2 binding together, and E1 and E2 represent the energy of a single material 1 and material 2 molecule, respectively. The binding energy of the system with CA/PDA/TPU was calculated to be Eb3 = Et3 - (Et2 + E3), where Et3 is the energy of the system containing material 1, material 2 and material 2 binding together, and Et2 is the energy of the supercell containing material 1 and material 2 binding together, and E3 represent the energy of a single material 3 molecule.

Material characterization

The microscopic features of each membrane were observed using field emission SEM (SU1510, Hitachi, Ltd., Japan), and the fiber diameter, pitch H, and helix diameter R were measured using ImageJ software. Each SEM image was measured 100 times with ImageJ, after which the average value was calculated. The above parameters were used to calculate the helical curvature K of the helical nanofibers prepared with different PDA contents for characterizing the helical structure. The larger K is, the smaller the pitch H is, demonstrating the more helical coils per unit length, and the tighter the structure is, and the value of K is calculated as follows44:

The molecular bonding characteristics of the fiber membranes were analyzed using X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D2 PHASER, Bruker AXS GmbH, Germany). Functional group characteristics of the fiber membranes were analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy (FT-IR, Nicolet is 10, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Pore size distribution and porosity

The pore size distribution of each fiber membrane was tested by using a pore tester (PM165, Topas, Germany). The test samples were circular with a diameter of 1 cm, and the test liquid was anhydrous ethanol. Each fiber membrane was measured three times and averaged. At the same time, the porosity of the membrane was measured by wet and dry weighing. The membrane samples were immersed in an isopropyl alcohol solution for 24 h. Then, the membrane samples were removed, the excess isopropanol solution on the membrane surface was removed, and the weight of the samples was weighed and recorded as \({W}_{1}\). Next, the membrane samples were thoroughly dried in an oven, after which the samples were weighed again and recorded as \({W}_{2}\). Membrane porosity, which is the ratio of the mass of the infiltration solution (isopropanol) to the apparent mass of the membranes was calculated by using Eq. (6). Each sample was tested five times under the same experimental conditions, and the average value was calculated45.

Where: \({W}_{1}\) is the mass of the wet membrane, g; \({W}_{2}\) is the mass of the dry membrane, g; \(\rho\) is the density of isopropanol, 0.765 g cm−3; and \(V\) is the apparent volume of the membrane, cm3.

Wetting and moisture permeability tests

The contact angle of the water and oil samples was measured using a contact angle meter (JC2000DM, Shanghai Zhongshan Digital Technology Equipment Co., Ltd., China). The moisture permeability of the fiber membrane was measured using a fabric moisture permeability meter (YG601H-II, Ningbo Textile Instrument Factory, China) according to standard GB/T 12704.1-2009. The temperature and relative humidity of the test conditions were 38 ± 2 °C and 90 ± 2%, respectively.

DLT properties

The forward and reverse breakthrough pressures of the membrane were obtained by measuring the maximum water column height that could be supported on one side of the membrane. During the measurements, water was dropped at a flow rate of 20 ml/min on one side of the fiber membrane, and the height of the water column at which the first drop began to pass through the membrane was recorded as the breakthrough pressure. A pipette gun was used to place 100 μl of magenta-stained water drops on the PHT-X Janus fiber membranes (in air or immersed in oil) and a camera was used to monitor and visualize the transfer of the drops. The directional water transport performance of the membranes was tested using a moisture management tester (MMT, Q290, Xi’an Wilze Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., China) according to the standard AATCC 195-2009. The sample was placed horizontally between the top and bottom sensors, and then a drop of solution (0.21 g, 0.9 wt% NaCl for sweat) was placed in the center of the sample. As the solution passes through the sample, the resistance of the top and bottom surfaces changes and the corresponding relative water content is associated. Thus, the directional water transport characteristic (R) (defined as the difference between the cumulative water content of the top and bottom surfaces) can be quantitatively calculated as shown in Eq. (7) calculated11:

where T is the test time, \({U}_{t}\) and \({U}_{b}\) are the real-time water content at the top and bottom, respectively.

Oil-water separation performance

A self-built oil-water separation unit was used to evaluate the Janus fiber membrane oil-under-directed water transfer characteristics. Prior to each separation, the membrane was wetted entirely with deionized water, and excess water was drained to bring the sample to the state to be tested. Free oil-water (consisting of 50 mL of methylene blue-stained water and 50 mL of Sudan III-stained oil) was poured into the oil-water separation device, starting at the point where the liquid touched the fiber membrane and ending at the point when there was no liquid flowing down at all. For all separation experiments, the permeate flux (\(F\), Lm−2h−1) and separation efficiency (\({E}_{{ff}}\),%)can be calculated from Eqs. (8) and (9), respectively46:

Where \(V\) is the volume of liquid passing through the membrane, L; \(A\) is the effective area of membrane separation, m2; \(t\) is the separation time, h; \({m}_{1}\) is the mass of liquid passing through the membrane, g; and \({m}_{0}\) is the mass of water in the oil-water mixture, g.

Thermal management performance

To visually evaluate the temperature reduction effect of a single guided wet material during water evaporation, the material was covered on the skin, water-simulated sweat was applied, and the surface temperature change of the material was monitored by an infrared thermal imager (FLIR-E6390, Estonia). The temperature and humidity of the environment were controlled, and the temperature drop of the material as the moisture evaporated was continuously recorded. According to GB/T 5453-1997 standard, the YG461E-III breathability meter (Ningbo Textile Instrument Factory) was used to characterize the breathability of the sample. During the test, the air volume passing through the unit area of the sample in unit time was measured under the condition of 20 cm² test area and 100 Pa pressure drop, and 10 tests were conducted for each sample to obtain the average value. According to GB/T 12704.2-2009 standard, YG601H-I computerized fabric permeability meter (Ningbo Textile Instrument Factory) was used to measure fabric moisture permeability. During the test, a water vapor transmission cup filled with distilled water and sealed with the test sample was placed in a sealed environment at a temperature of 38 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 50 ± 2%. After 1 h of water vapor transmission, the total mass of the cup and sample, \({m}_{1}\), was measured using an electronic balance. After equilibrating for another hour, the total mass, \({m}_{2}\), was measured again. The difference between the two masses, \(\Delta m\), represents the amount of water vapor transmitted. Each sample was tested three times, and the average value was taken.

Tensile properties

Test of tensile performance test according to the standard GB/T 3923.2 2013, using MTS E43.504 universal testing machine (winters’ industrial system co., LTD., the United States) in constant velocity tensile test. The sample length was set to 80 mm, the tensile interval to 40 mm, the width to 10 mm, and the tensile speed to 10 mm/min. Each sample was tested at least 3 times.

Data availability

All data needed to support the conclusions of this manuscript are included in the main text and the supplementary information/source data file and are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Yan, L. et al. Porous Janus materials with unique asymmetries and functionality. Mater. Today 51, 626–647 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, H. & Lin, T. Directional fluid transport in thin porous materials and its functional applications. Small 13, 1601070 (2017).

Yan, X. et al. Janus polyacrylonitrile/carbon nanotube nanofiber membranes for oil/water separation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 4511–4521 (2023).

Liu, L. et al. Trilayered fibrous dressing with wettability gradient for spontaneous and directional transport of massive exudate and wound healing promotion. Adv. Fiber Mater. 5, 574–587 (2022).

Fan, C. et al. Dynamically tunable subambient daytime radiative cooling metafabric with Janus wettability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300794 (2023).

Zhou, H. & Guo, Z. Superwetting Janus membranes: focusing on unidirectional transport behaviors and multiple applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 12921–12950 (2019).

Lu, T.-D., Wang, Q., Gu, S.-S. & Sun, S.-P. Beyond symmetry: exploring asymmetric electrospun nanofiber membranes for liquid separation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310218 (2023).

Qin, Y. et al. Preparation and characterization of a PU/(PAN/PVP) unidirectional moisture transport fibrous membrane. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 5, 9817–9824 (2023).

Si, Y. et al. Bioinspired stable single-layer Janus fabric with directional water/moisture transport property for integrated personal cooling management. Adv. Fiber Mater. 5, 138–153 (2022).

Kuang, X. et al. Advances in directional liquid transport textiles: mechanism, construction, and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2406906 https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202406906 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Thermal and moisture managing e-textiles enabled by Janus hierarchical gradient honeycombs. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311633 (2024).

Yin, H. et al. Biomimetic three-layer hierarchical scaffolds for efficient water management and cell recruitment. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 222, 113081 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Beetle and cactus-inspired surface endows continuous and directional droplet jumping for efficient water harvesting. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 1507–1516 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Bioinspired nanofibril-humped fibers with strong capillary channels for fog capture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 28876–28884 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Janus nanofiber membranes with photothermal-enhanced biofluid drainage and sterilization for diabetic wounds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2315020 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Biomimetic fibrous murray membranes with ultrafast water transport and evaporation for smart moisture-wicking fabrics. ACS Nano 13, 1060–1070 (2019).

Ji, K. et al. Green-solvent-processable composite micro/nanofiber membrane with gradient asymmetric structure for efficient microfiltration. Small 19, 2207330 (2023).

Silva, P.-E. -S., de Abreu, F. & Godinho, M.-H. Shaping helical electrospun filaments: a review. Soft Matter 13, 6678–6688 (2017).

Zan, G. & Wu, Q. Biomimetic and bioinspired synthesis of nanomaterials/nanostructures. Adv. Mater. 28, 2099–2147 (2016).

Yu, Y. et al. Bioinspired helical microfibers from microfluidics. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605765 (2017).

Wu, H., Zheng, Y. & Zeng, Y. Fabrication of helical nanofibers via co-electrospinning. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 987–993 (2015).

Chen, S. et al. Effect of different bicomponent electrospinning techniques on the formation of polymeric nanosprings. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 294, 781–786 (2009).

Yoon, J. et al. Synthesis of inherently helical nanofibers: effects of solidification of electrified jet during electrospinning. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 139, e52352 (2022).

Wu, H., Zhao, S. & Han, L. Fabrication of CA/TPU helical nanofibers and its mechanism analysis. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 13, 104 (2018).

Hu, X. et al. Biomimetic helical fiber cellulose acetate/thermoplastic polyurethanes photodynamic antibacterial membrane: Synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253, 126737 (2023).

Liu, Y., Zhang, J. & Wu, P. Near-frictionless long-distance water transport in trees enabled by hierarchically helical molecular pumps. CCS Chem. 1–9 https://doi.org/10.31635/ccschem.024.202403903 (2024).

Cheng, W. et al. Versatile polydopamine platforms: synthesis and promising applications for surface modification and advanced nanomedicine. ACS Nano 13, 8537–8565 (2019).

Qu, H., Wei, S. & Guo, Z. Coaxial electrospun nanostructures and their applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 1, 11513–11528 (2013).

Kim, C.-W., Frey, M.-W., Marquez, M. & Joo, Y.-L. Preparation of submicron-scale, electrospun cellulose fibers via direct dissolution. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 43, 1673–1683 (2005).

Lu, Y.-L. et al. Preparation and properties of natural rubber reinforced with polydopamine-coating modified carbon nanotubes. Express Polym. Lett. 11, 21–34 (2017).

Mou, Z. et al. Synthesis of polyelectrolyte-decorated polydopamine nanoparticles via surface reconstruction for enhancing oil-based lubrication. Chem. Eng. J. 480, 147959 (2024).

Cheng, W. et al. Self-assembly amino-quinone network coatings onto polyester fabric via single-sided spraying of natural polyphenols and polyethyleneimine for highly efficient moisture conducting and bacteriostatic properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 606, 154913 (2022).

Miao, D., Huang, Z., Wang, X., Yu, J. & Ding, B. Continuous, spontaneous, and directional water transport in the trilayered fibrous membranes for functional moisture wicking textiles. Small 14, 1801527 (2018).

Ge, P., Wang, S., Zhang, J. & Yang, B. Micro-/nanostructures meet anisotropic wetting: from preparation methods to applications. Mater. Horiz. 7, 2566–2595 (2020).

Meng, N. et al. Integrated high barrier and efficient moisture-wicking multilayer textile for medical and health protection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2305411 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Reversible water transportation diode: temperature-adaptive smart Janus textile for moisture/thermal management. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1907851 (2019).

Dai, B. et al. Bioinspired Janus textile with conical micropores for human body moisture and thermal management. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904113 (2019).

Liu, X., Wu, H. & Wu, P. Synchronous engineering for biomimetic murray porous membranes using isocyanate. Nano Lett. 22, 3077–3086 (2022).

Chi, H. et al. Fabrics with novel air-oil amphibious, spontaneous one-way water-transport capability for oil/water separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 29150–29157 (2021).

Tian, X., Jin, H., Sainio, J., Ras, R.-H. -A. & Ikkala, O. Droplet and fluid gating by biomimetic Janus membranes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 6023–6028 (2014).

Yetisen, A.-K. et al. Nanotechnology in textiles. ACS Nano 10, 3042–3068 (2016).

Zhou, W. et al. Highly durable Janus fabrics based on transfer prints for personal moisture management. Small 19, 2302512 (2023).

Zhao, H., Fan, Z., Jia, C. & Cai, Z. One-way water transport and enhanced heating and cooling for cotton fabrics. Cellulose 30, 3351–3361 (2023).

Spinks, G.-M. Advanced actuator materials powered by biomimetic helical fiber topologies. Adv. Mater. 32, 1904093 (2020).

Islam, M.-S., McCutcheon, J.-R. & Rahaman, M.-S. A high flux polyvinyl acetate-coated electrospun nylon 6/SiO2 composite microfiltration membrane for the separation of oil-in-water emulsion with improved antifouling performance. J. Membr. Sci. 537, 297–309 (2017).

Che, W., Zhou, L., Zhou, Q., Xie, Y. & Wang, Y. Flexible Janus wood membrane with asymmetric wettability for high-efficient switchable oil/water emulsion separation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 629, 719–727 (2023).

Acknowledgements

X.K. and Z.Z. contributed equally to this work. The research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant NO. 2303054 (H.H.), 52373058 (P.M.), the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu (BK20231056, H.H.), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (JUSRP123005, H.H.). We appreciate Dr. Longsheng Zhang from Jiangnan University for Density Function Theory (DFT) and Mr. Junlun Cao from RMIT for Molecular Dynamics (MD) modeling and simulation support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H. conceived the concept. S.R. and P.M. provided guidance and support throughout the project. X.K. and Z.Z. took lead roles in performing the experiments, analyzing data, and drafting the manuscript. X.M. fabricated and characterized the nanofiber membrane. X.Z. and L.Z. made the DFT and MD simulations. H.C. and G.J. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jafar Azamat, Xiquan Cheng, Tifeng Jiao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuang, X., Zhang, Z., He, H. et al. Biomimetic Janus membrane with spongy channels for directional liquid transport. Nat Commun 16, 10001 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64964-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64964-0