Abstract

Shifting electric vehicle charging to use cleaner electricity can reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Grid emissions factors can inform when to shift demand, but key assumptions behind existing emissions factor methods fail for today’s grids and electric vehicle adoption levels. We combine real charging data with a Western U.S. grid model to test these methods under increasing electric vehicle adoption. We find that following existing average and marginal emissions factor methods to manage charging can inadvertently increase grid emissions when emissions factor signals are noisy, too many electric vehicles follow the same signal, or when high-emitting generators respond. We instead propose an alternative Cascading marginal emissions factor strategy that manages charging in smaller groups. We show that the Cascading strategy reduces added emissions by 10–28% across grid scenarios for at least 2 million electric vehicles. Our research reveals how demand response methods must change to reduce emissions and support the grid transition under wider electric vehicle adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leveraging the decarbonization of the electricity grid, electrification is a key strategy to reduce emissions from transportation, heating, industry, and other sectors1. Once these sectors are electrified, their operating carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions depend on the electricity used, which in turn depends on the type of electricity generation used to meet this demand2,3,4.

In grids powered by different high- and low-emitting types of electricity generation throughout the day, shifting demand to times with lower-emitting generators could reduce these operating CO2 emissions5. Organizations such as community choice aggregators, datacenter managers, and electric vehicle (EV) aggregators are increasingly aiming to provide completely carbon-free power to meet their demand6,7,8. However, this requires intelligent, grid-aware charging management methods since emissions impacts of demand shifting strategies are difficult to implement in practice. In the United States, generators are dispatched in order of least-cost9, which may not match the order of least-emissions4,10, and the emissions rates of the generators that respond to shifts in demand vary substantially by location, time of year, and time of day11,12.

EVs, thanks to the widespread availability of managed charging, offer a large-scale test of such methods to shift demand13. Dynamic managed charging, also called smart or controlled charging, can target shifts to precise times to reduce costs, avoid peaks, or reduce emissions by improving alignment with the generator dispatch4,14,15,16. Managed charging can include shifting the charging session’s start or end time, modulating the charging rate throughout the session, or changing the location and duration of the session altogether17,18,19.

Emissions impacts from all three of these objectives depend on many factors, including EV charging behavior assumptions and the regional grid mix3,20. Following some common cost minimization approaches can even result in emissions increases21,22. Consequently, it is important for stakeholders aiming for 100% carbon-free power to optimize for emissions directly, not cost.

There is not a consensus on which direct emissions-minimizing managed charging method is best and guaranteed to reduce emissions. Grid operators and EV aggregators can use either a centralized or decentralized approach. In a centralized case, grid operators schedule and dispatch EV charging directly with other grid resources23,24,25,26,27,28,29. However, since the United States market is cost-focused and policies do not allow for carbon-based dispatch, stakeholders who want to use demand response to reduce emissions cannot rely on centralized charging management or supply-side policies.

Many EV aggregators must turn instead to decentralized charging management, dispatching EVs to follow simple signals and acting independently from the central dispatch to achieve their objectives17. The simple shifting of EV demand to off-peak times or to the middle of the day can reduce emissions in some regions through better utilization of renewables15,30,31,32,33 but can increase emissions in others if coal generators are among the next-in-line in the dispatch at those times3,21,22,34,35,36. Furthermore, this type of charging management faces additional challenges because EV demand is constrained by individual drivers’ mobility needs, charging options, and behaviors20,37,38,39. Aggregators must then decide how to incorporate any unpredictable driving and charging behavior and balance managed charging granularity with increased computational complexity.

A potential solution is the use of a time-varying emissions signal, which changes frequently (for example, hourly) in response to the current grid mix. Hourly marginal prices are the most efficient signal to minimize costs, but that approach does not simply translate to emissions, and there is no agreement on the best time-varying emissions signal to use. Existing approaches use average or marginal emissions factors (EFs) to represent the real-time emissions intensity of electricity generation32,34,35,40,41,42,43,44. Average emissions factors (AEFs) capture the average carbon intensity of all generation at a given time, dividing total emissions by total generation, while short-run marginal emissions factors (MEFs) capture the marginal increase in emissions that would be caused by a marginal increase in demand45,46. The short-run MEF can be given by the emissions rate of the marginal generator, which is the most recent generator dispatched from the merit order45. Other applications that measure emissions impacts over multiple years use medium- and long-run MEFs4,47,48 or even life cycle analysis techniques3,49; here we focus only on short-term impacts and short-run MEFs.

The AEF32,50,51,52,53 and MEF5,16,41,43,54 signals have both been used as objectives for managed charging30,35,42, but their success depends on two central assumptions. For the AEF to accurately capture the emissions impact of managed charging, the generators that respond to a change in demand must match the average overall generation mix at that time. That assumption will fail with a least-cost dispatch where generators of diverse types have different costs. For the MEF to accurately capture the emissions impact of managed charging, either the change in demand must be sufficiently small such that only the marginal generator responds, or all generators responding to the demand increase must have the same emissions rate45. That assumption will fail at some level of EV adoption when large amounts of demand all shift to the same hours, overshooting the margin and negating any initial benefits. The overshooting problem has been solved for cost minimization signals but not for emissions14,55. We have found an example where the MEF method was sequentially adjusted for higher demand, dividing the set of EVs into 100 smaller groups41, but the effects were not thoroughly tested. There is still not an agreement about when exactly existing methods will fail, whether we have already passed that point with current levels of EV adoption, nor how these methods can be made future-proof to increasing demand.

In this study, we demonstrate the limits and failures of existing EF-based methods given growing levels of EV adoption, and we chart a path for emissions-minimizing managed charging. We focus on the challenging case of emissions minimization in a least-cost dispatch system without carbon pricing or other supply-side carbon reduction policies. We choose the Western U.S. Interconnection (WECC) as a case study for its high EV adoption, complex mix of generators, and ambitious plans for grid decarbonization. We extend an open-source, single-node, reduced-order economic dispatch model proposed by Deetjen and Azevedo to simulate grid emissions and EF signals in 2020 and 203010. We couple this with a detailed model of private, passenger EV demand based on real charging and driving data collected from over 700 California EV drivers in 2020, carefully considering driving patterns, charger availability, and charger power. Our results show that following existing MEF methods fails to meaningfully decrease emissions beyond 500,000 managed EVs, equal to about 30% of the EV fleet or less than 0.1% of the total vehicle fleet in WECC as of 202332,56, and can inadvertently increase emissions beyond 1.5 million EVs. The success of following the AEF method varies by year and season, at times decreasing and at other times increasing emissions for the same number of EVs. Instead, we present an alternative method with Cascading MEF signals that can deliver emissions reductions robust to even larger numbers of EVs. This method uses knowledge of the critical point where demand exceeds the margin to divide drivers into small-enough, marginal groups and send managed charging signals to these groups in sequence. Following the Cascading MEF method is successful across scenarios, decreasing added emissions by 10.6–28.3% and always either matching or outperforming the traditional MEF. Our research reveals the danger of carrying forward early-transition solutions to large-scale demand response for EVs and other newly electrified flexible loads. Schemes like the Cascading MEF method should be deployed instead to ensure demand flexibility will reduce emissions and support the grid’s transition.

Results

Managed charging with existing emissions factors

In regions with a variety of generators and renewable power sources, there is potential to reduce emissions by shifting EV demand away from high-emitting coal generators toward low- or non-emitting generation options. WECC is an example of such a region: it has a mix of different types of fossil fuel generators, hydro, nuclear, and substantial amounts of renewables. Fig. 1a shows the WECC merit order for the first week in 2020 (plots for additional weeks appear in Supplementary Fig. 1). The generators are ordered neatly for dispatch by their generation cost, yet their corresponding emissions do not show a clear increasing or decreasing trend.

a Renewable energy capacity and generator merit order for the Western Interconnection (WECC) during the first week of January 2020. The top plot shows the generator operating cost while the bottom plot shows the associated emissions, which are noisy and not correlated with cost. b Hourly MEFs and average emissions factors (AEFs) for the first week in January 2020. MEFs are noisier and larger in magnitude than AEFs. c Normalized added CO2 emissions for charging in WECC for the month of January 2020, averaged over 15 runs with error bars for +/− two standard deviations. The results show that the MEF method is not scalable to large numbers of added EVs.

The disorder of generator emissions rates is reflected in the hourly MEF signal. Fig. 1b shows a comparison between the noisy MEF signal, representing the emissions of the generator responding to a marginal increase in demand, and the smoother AEF signal, representing the total emissions divided by the total demand at each timestep. While the AEF has a consistent shape day-to-day, the MEF appears almost random, as the smallest change in demand can cause it to double when the marginal generator switches from gas to coal.

It is difficult to test the effect of managed charging without a full model of grid dispatch45. Previous implementations of the MEF and AEF have used the same factors to both guide and evaluate the method, biasing the results. Here, instead, we use the economic dispatch model to evaluate emissions impacts by comparing the dispatch of generators under managed and baseline, or uncontrolled, demand45. We calculate this baseline demand from the driver behavior dataset, assuming that charging begins immediately upon plug-in and no charging timers are used (see Methods for details).

Fig. 1c shows the normalized added CO2 emissions for EV charging demand with 100,000 to 2 million added EVs. We find that following the AEF method yields a slight emissions reduction in the grid of January 2020, but the success of following the MEF method depends heavily on the number of added EVs. We find that the MEF method is not scalable, and implementing it with 2 million vehicles actually increases emissions relative to baseline charging. This occurs because the demand is no longer marginal when too many vehicles follow the same signal.

As renewables and other non-emitting generators are never on the margin in 2020, the MEF targets times when only natural gas plants will ramp up to meet the shifted EV demand. When demand overshoots the margin, additional coal plants must be used, adding more emissions than in the scenario with no managed charging at all. This result motivates the need for an alternative effective and scalable managed charging method.

Cascading marginal emissions factors

The MEF method can be successful if the change in EV demand is marginal or is small enough to only rarely change the marginal generator. Fig. 1c shows that a group of 100,000 EVs is small enough on average to reduce emissions in this grid. We apply this insight to implement a managed charging strategy, the Cascading MEF method, that ensures this threshold of 100,000 EVs is not crossed, even for higher levels of adoption.

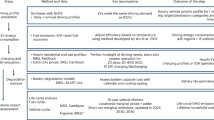

Fig. 2 illustrates the Cascading MEF method. Instead of sending one signal to all EVs, the fleet of EVs is divided into a number of separate groups, and each group receives a different signal. We manage the first group using the MEF signal calculated from the baseline demand grid dispatch, which includes the baseline demand of that group as a placeholder. Then, we replace the first group’s baseline demand with its managed demand and re-run the dispatch to find a signal for the second group. This process repeats sequentially for all groups. Similar grouping strategies have been used in other applications to reduce peak charging demand but not emissions14,32.

The full set of electric vehicles is divided into n smaller groups; each group is then managed in sequence with its own MEF signal. The baseline demand for each group is used as a placeholder to improve the calculation of the MEF signal, then replaced by the newly managed demand profile in the calculations for later groups.

Comparing emissions impacts of AEF, MEF, and Cascading MEF methods

We evaluate the emissions impact of implementing the Cascading MEF method across multiple months and years to test its performance across various grid conditions, comparing against AEF and MEF method implementations and baseline charging. The 2020 simulations leverage historical grid and demand data while the 2030 simulations assume increased renewables, the addition of stationary storage, increased baseline grid demand, and specific generator additions and retirements, all scaled according to WECC projections (see Methods for details).

We show results for varying numbers of EVs between 1000 and 2 million added to the historical baseline demand to illustrate the range of demand levels where these traditional methods fail. We divide the EVs into 20 groups for the Cascading MEF method such that the largest group size is 100,000 EVs.

Fig. 3 displays added emissions for grid models of January and July in 2020 and 2030 for all managed charging methods. These months were chosen to limit impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic as California’s electricity demand had largely recovered from COVID-19 restrictions by July 202057. Table 1 shows the emissions reductions relative to the emissions from baseline charging. Supplementary Table 1 shows the absolute values in kg CO2.

Results are shown using the grid for a January 2020, b January 2030, c July 2020, and d July 2030. The shaded area around each line indicates two standard deviations above and below the average value of 15 simulation runs. In each case, managing charging with the simple MEF is not effective beyond 500,000 vehicles while implementing the Cascading MEF method consistently reduces emissions for up to 2,000,000 vehicles.

Following the Cascading MEF method yields at least a 10% reduction in added emissions in all four simulation months and for every number of added EVs tested and is the only method tested here that reduces emissions in all cases. While charging decisions following the MEF method reduce emissions for small numbers of EVs, after 500,000 EVs these decisions have little impact and can even lead to increased emissions.

On the other hand, following the AEF method reduces emissions in some cases, especially in July both for 2020 and 2030, but increases emissions in others. In January 2030, following the AEF method increases added emissions by up to 3.7%. These dynamics are driven by the availability of renewable generation and fossil fuel prices. Specifically, AEF managed charging concentrates charging during the daytime due to high solar generation. Unless there is excess renewable or non-emitting generation, demand shifted to that time is not met with solar. In January 2030, higher-emitting generators on the margin around midday lead to an increase in emissions with this strategy. Conversely, in July 2030, lower-emitting generators on the margin around midday due to lower natural gas fuel prices lead to a reduction in emissions. For all scenarios, the standard deviation of added emissions between trials is small, driven by the large number of vehicles sampled and by the similar charging availability windows of vehicles in the dataset.

We also observe baseline differences between the 2020 and 2030 grid scenarios. Although there are increased renewables in 2030 (specifically, 176% more solar and 50% more wind capacity in WECC), this additional non-carbon-emitting capacity does not outpace increased electrification enough to ever be on the margin. Given the planned retirement of many high-emitting coal and natural gas generators, baseline charging in WECC has lower added emissions in 2030 than in 2020. Thus, in the WECC region, emissions reductions from managed charging are most important in the short- and medium-term with increasing EV demand and more high-emitting generators to avoid.

Lastly, although following the Cascading MEF signal leads to the greatest emissions reduction among the methods we tested, the reduction is not constant with increasing EV adoption. Specifically, in January 2020, implementing Cascading MEF with 1000 vehicles reduces emissions by 26% compared to the baseline but only yields a 14.8% reduction with 2 million added vehicles. This trend is due to increasing group sizes. Our implementation with 20 groups means a group size of 50 vehicles in the first data point and a group size of 100,000 vehicles in the last data point. It is almost certain that a group of 50 EVs is small enough to be on the margin, but a group of 100,000 will sometimes cause a change in the marginal generator. Group size is an important implementation trade-off: limiting the number of groups limits the complexity of the program for the grid operator but also limits the emissions reductions.

Cascading MEF implementation considerations

EV aggregators using the Cascading MEF method may encounter a variety of challenges with real-world implementation. They must make decisions about the number of EVs in each group and understand how effective their managed charging will be if drivers do not perfectly respond to their dispatched signal. To inform best implementation practices, we test the Cascading MEF method in scenarios with different group sizes and imperfect response to EF signals.

Fig. 4a illustrates the effect of group size on emissions as we vary the number of groups from one, equivalent to the traditional MEF method, to 40. There are diminishing returns for using smaller and smaller EV groups: increasing the number of groups beyond 10 yields only minimal further emissions reductions. For implementation, this means that group size need not be exceedingly small; a group size below 200,000 EVs (corresponding to 10 groups in 2 million vehicles) is sufficient for this system, and running managed charging with smaller groups could introduce unnecessary additional computation costs.

a Cascading marginal emissions factor (MEF) method sensitivity to group size. Further emissions reductions from increasing the number of groups are minimal beyond 10 groups. b Comparison of Cascading MEF method with perfect vs. uncertain charging forecasts and driver responsiveness to managed charging. The shaded area around each line indicates two standard deviations above and below the average value of 15 simulation runs. When not all vehicles follow the signal as expected, the Cascading MEF method is less effective but still provides emissions reductions over traditional MEF managed charging.

Since the MEF signal for each group assumes that each prior group follows its signal perfectly, any deviations from this schedule affect each subsequent group. Aggregators may have limited information about EV drivers’ behavior, both when travel patterns change and drivers refuse to follow a signal. Both of these changes could lead to an altered aggregate managed demand profile and therefore a different resulting MEF signal58.

We test a scenario in which only 75% of EVs follow the EF signal perfectly and the remaining 25% of drivers do not follow the EF signal and are instead assumed to have baseline charging demand. Fig. 4b compares the Cascading MEF method with perfect responsiveness to the EF signal against this case with uncertain responsiveness. Exact percentage values of decrease in emissions are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Adding uncertainty renders the method less effective than perfect responsiveness, but this more realistic implementation still outperforms traditional MEF and AEF methods. Even when only 75% of drivers’ demand is as forecast, following the Cascading MEF method yields over a 7% emissions decrease with 2 million vehicles, while following the traditional MEF method increases emissions.

Cost and peak demand impacts of the Cascading MEF method

Although the Cascading MEF method is enacted in a decentralized manner, to achieve widespread implementation, the scheme still must avoid negative impacts to the grid system as a whole. Two other common objectives in grid operation are reducing total costs and peak demand. Emissions-minimizing charging could help reach emission targets, but it should not substantially increase costs nor cause demand spikes that strain grid infrastructure.

Table 2 shows the average cost reduction across all simulation months and years from each managed charging method compared to the cost from baseline charging. Following the AEF method leads to the most substantial cost decrease, while following the MEF and Cascading MEF methods has minimal effects on the total cost (less than 2.5% increase or decrease). Data for each individual month are presented in Supplementary Table 3. The results indicate that implementing the Cascading MEF method does not compromise on cost and can in some cases decrease costs compared to baseline charging.

To analyze the impact of managed charging on peak demand, Fig. 5 compares baseline and managed EV charging demand profiles. The total energy delivered is constant across managed charging methods over the course of the week (shown in Supplementary Fig. 3); this plot displays a segment of the week-long optimization. During this 24 hour snapshot, demand is shifted away from peak evening hours and is pushed toward daytime with the AEF method and toward late night with the MEF and Cascading MEF methods. Flexibility creates large demand spikes when following the MEF method during times with low MEFs and when many of the EVs are plugged in, like hour 3. The demand peak is much smaller when following the Cascading MEF method than the MEF since separate groups of EVs are encouraged to charge at separate times. This shows that following the Cascading MEF method can achieve substantial emissions reductions without compromising on other grid impacts.

Sensitivity of managed charging to other design parameters

The time-varying, grid-aware signals of the Cascading MEF method are effective for emissions reduction, but implementing this type of managed charging relies on certain assumptions about EV baseline charging and aggregator capability. Specifically, the baseline tested in this work assumes that EV drivers do not use charging timers, and the Cascading MEF method assumes that aggregators can dispatch signals hourly with knowledge of existing charging session locations. To analyze scenarios without these assumptions, we test a scenario with a charging timer implemented in the baseline profile and a simple daytime managed charging method. We also test a case with increased charging availability where we make more generous assumptions about the aggregator’s ability to control charging.

Although aggregators may not have perfect foresight about exact charging session times, they may have knowledge about when the EV is parked at home with access to a charger. Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 display emissions reductions resulting from increasing EV plug-in availability in managed charging. The scenarios presented thus far use only existing sessions, limiting charging power shifts and modulation to only charging sessions calculated directly from the dataset. Here we examine a maximum sessions scenario with increased availability. This is achieved by allowing charging to occur whenever the EV is parked near a charger, even if a charging session did not occur at that time in the historical data.

Surprisingly, adding availability does not automatically lead to a decrease in emissions, and the overall conclusions of this paper are unchanged by these additional charging sessions. Following the MEF and AEF methods still does not yield consistent emission reductions while following the Cascading MEF method reduces emissions in all cases by at least 10% for at least 2 million EVs. This result occurs because the added sessions in the maximum sessions scenario allow for higher peaks in demand, as more EVs can be shifted to the times when the emissions signal is lowest. These high peaks lead more easily to overshoot and push smaller groups of EVs off the margin, suggesting that, for the same number of EVs, the aggregator should dispatch signals in smaller groups if they have knowledge about the maximum sessions possible.

When drivers enable a charging timer, it alters the baseline added emissions, since baseline charging becomes concentrated around the timer start. To examine the effect of timers on our results, we implement a case with a midnight charging timer59. This entails shifting overnight charging sessions to begin at midnight in the baseline. Supplementary Fig. 2 compares the baseline charging with and without the charging timer, and Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 6 show the added emissions from following each emissions-minimizing method compared to the timer baseline. In January 2020, following the Cascading MEF method is between 0.1– 3.1% less effective in reducing emissions relative to the baseline with the timer than relative to the baseline without the timer, depending on the number of EVs added.

Finally, to model a scheme where EVs are simply incentivized to charge during the daytime hours, we use a simple charging signal that only changes twice per day instead of varying the signal every hour. The results for this simple daytime charging analysis are presented in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 7. We find that following this simple signal performs similarly or worse than following the AEF method, reflecting the value of more dynamic signals, the absence of excess renewable generation in our test months in 2020 and 2030, and the relatively high natural gas prices in these grid scenarios.

Discussion

Our research shows that existing approaches to reduce emissions from EV charging with AEF- or MEF-based methods may be less effective with today’s grid and demand conditions. In the Western U.S. today, there are already over 1.6 million registered EVs56, and distributed energy resource aggregators, such as OhmConnect and EnergyHub, are already operating with gigawatt scale capacity60,61. With over 500,000 EVs under the same managed charging method, the key assumption behind the widely used MEF method could fail and lead to an increase in emissions from following this method. We show that the proposed Cascading MEF method is effective for this many vehicles across seasons. In our simulation, following the Cascading MEF method reduces emissions by 13–28% in 2020 and 10–21% in 2030 for up to 2 million vehicles. With small enough groups, the method design supports implementation for millions more EVs and is robust to the region’s plans for full electrification.

Based on these findings, we make several recommendations for policymakers looking to reduce short-term emissions from EV charging. First, consider avoiding MEF or AEF managed charging signals at large scale or in systems where high-emitting generators are commonly on the margin when there is low net demand. Beyond 500,000 vehicles (equivalent to another type of aggregated flexible load drawing approximately 750 MW of demand, calculated from Fig. 5), consider using the Cascading MEF method to manage charging.

Next, to implement the Cascading MEF method, grid operators should develop a program to pass signals to aggregators. The program should contain the following steps: (1) determine the number of EV groups, (2) assign the EVs to different groups, either randomly or (if possible) ensuring EVs with similar demand profiles are distributed across different groups, (3) use simulations to calculate the MEF signal for each group, and (4) communicate a different signal to the aggregators for each group. Lastly, we recommend measuring and reporting the emissions impact of the Cascading MEF method and refining the group size as needed.

Implementing a successful Cascading MEF program requires the consideration of many technological, behavioral, and financial factors. One challenge is coordinating signal dissemination: the vehicles all need a platform to receive the managed charging signal. EV aggregators can serve this role, but they must make decisions about how to account for uncertainty in driver behavior, how frequently a signal changes, and, if they manage more EVs than fit in one group (in the Cascading MEF method), which signals to communicate to which EVs. All of these factors affect computational complexity and efficacy of the managed charging. We find that when aggregating large numbers of EVs, there are only marginal improvements from using group sizes smaller than 200,000 vehicles.

Running the simulation with our dataset requires about one core-hour of computation time per Cascading MEF group per week of simulation time horizon, so with 20 groups or fewer, the simulation will run in less than a day. To implement this method, grid operators and EV aggregators would need to combine their knowledge of the day-ahead generator dispatch bid stack, projected non-EV baseline demand, and projected baseline EV demand. Operators could then calculate the Cascading MEF signals on a daily or weekly basis and pass them to an EV aggregator to dispatch to drivers.

In terms of driver acceptance of managed charging signals, we did not assume changes in driver plug-in behavior in the main analysis, only automated charging management within and across existing plug-in sessions. Nevertheless, drivers may choose to opt out of this managed charging method or change their plug-in and travel patterns. While that makes this method less effective, the uncertainty analysis in Fig. 4b shows that it still delivers an improvement over traditional MEF methods. Regardless of behavior forecasting, aggregators should use time-varying signals for managed charging instead of simple charging shifts.

For many stakeholders, it is important that minimizing for emissions does not lead to large increases in cost. While a small aggregator or datacenter may be less inhibited by cost and able to focus solely on emissions-minimizing managed charging, not all organizations have that opportunity. They may instead implement a mixed cost and emissions objective. We find that the total system generation costs are similar between the baseline and managed charging scenarios; if wholesale prices reflect these generation costs, then aggregators should not experience financial challenges from implementing the Cascading MEF method.

When modeling charging specifically, different assumptions about the profile of baseline charging or the power rating of public chargers could affect the results. While implementing a charging timer does not substantially change baseline added emissions, using a different dataset where users make charging decisions based on other rate structures could alter these baseline emissions. Lastly, if extreme fast charging becomes ubiquitous, it could increase charging demand spikes substantially. Different charging patterns from outside California or the widespread availability of vehicle-to-grid chargers could also change the optimal group size. Future work should include a comparison to different types of baseline charging, such as convenience-focused or cost-focused, and sensitivity analyses to fast charging and vehicle-to-grid availability.

Our analysis assumes the distribution grid can support changes in charging demand, but distribution grid equipment limits may be violated when all homes in a neighborhood install Level 2 chargers62,63. Our model also reduces the region to a single transmission node, but emissions factors may vary across the region64. Future work should investigate both the distribution network and transmission congestion impacts on the Cascading MEF method, including how EV grouping for this method may be affected.

When implementing the Cascading MEF method in other regions, different generation mixes or technologies may also affect the results. We select the entirety of WECC to study the Cascading MEF method for a grid dispatch model with detailed MEF data and a region with a noisy generator emissions bid stack. Furthermore, we assume nonfossil generation is dispatched first and find it is never big enough to be on the margin in our WECC simulation scenarios. As a result, there are no highly desirable charging times when the MEF is zero or when the MEF and AEF align. Comparing the Cascading MEF method to the MEF and AEF methods in other regions where renewables are either dispatched last or are commonly on the margin is an important area of future research.

In other interconnections or even subregions of WECC, seasonality and regional differences can also affect the grid mix. Where the average generator capacity is smaller, the maximum EV group size must be smaller too, and the algorithm may be sensitive to EV group assignment. The AEF method may perform better in other systems with renewables curtailment or where low-emitting generators are consistently on the margin during periods of low net demand. The MEF method may perform better if the merit order is smoother, namely, if it is better ordered by emissions rate. Then, overshooting the margin and changing the marginal generator should introduce only a small error in the expected emissions impact. Alternatively, in a region where generator capacities are larger, overshooting the margin requires larger spikes in demand and may happen less frequently. However, in our simulations, the Cascading MEF method delivers more consistent reductions than the MEF method in a system with a noisy MEF signal and dispatch order.

Another area of future research is the development of a modified MEF signal that encompasses multiple marginal generators deeper down the dispatch bid stack. While charging decisions made via the Cascading MEF method must be calculated sequentially by group, a modified MEF signal could allow one-shot managed charging schedule optimization. However, this signal would require developing new methods to accurately predict each group’s managed charging demand to determine the second, third, or later marginal generators that should be included in the signal.

A successful emissions-minimizing charging algorithm should also be future-proof in the face of a changing grid and future policies. If policymakers or regulators place a carbon price on fossil generation, the generator merit order will shift and with a very high carbon price could be ordered solely by emissions rate. This will reduce the noisiness of the MEF signal and increase the efficacy of both the MEF and Cascading MEF signals.

The Cascading MEF method can be applied to any type of flexible load. The deployment of widespread distributed battery storage and the electrification of heating and other transport segments like medium- or heavy-duty fleets will all introduce new loads controllable by this method. Commercial EVs in these fleets specifically may be even more price sensitive and better suited for this type of managed charging than private, light-duty EVs.

With a complex mix of generators, using existing managed charging methods with the MEF or AEF signals can fail to reduce emissions. The Cascading MEF method provides EV charging aggregators and other flexible demand with a cleaner alternative to ensure emissions reductions even as electrification increases and the amount of flexible demand grows beyond the margin.

Methods

EV charging data and availability

We use a dataset of historical EV charging and driving events from 748 Audi e-tron vehicles located in California. While the dataset covers the period between April 2019 and July 2021, we focus specifically on the months of January and July 2020 to capture charging patterns in two different seasons and avoid the main effects of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. The data entries for January include 680 drivers with 7110 charging sessions in total. Each data entry is specific to one vehicle and contains the date and time and the vehicle’s mileage, battery state of charge (SOC), location, and charging status (either plugged or unplugged). The vehicles each have a battery capacity of 83.6 kWh.

We identify each vehicle’s stops based on plateaus in the mileage value, and we use the change in SOC to reconstruct the vehicles’ energy use and baseline charging profiles. If the SOC increases by more than 2% during a stop, we assume a charging session occurred. Smaller changes in SOC are very common during mileage plateaus; we assume these reflect re-calibration adjustments of the SOC estimation algorithm.

As the SOC is recorded only at the beginning and end of each charging session and the exact charging power profile is unknown, we assume a constant charging rate for baseline charging. We test two scenarios, one without and one with a charging timer.

Without a charging timer, we assume that charging begins immediately at the maximum rate after the vehicle is plugged in, and we do not make any inferences about start or end times of charging behavior based on any electricity price structure.

With a charging timer, we make the same assumption for all sessions except for overnight charging sessions that have enough flexibility to shift the session to accommodate a charging timer. For those sessions, we assume charging begins at midnight and is constant at the maximum rate until the battery reaches the final SOC. The midnight timer start reflects the beginning of the off-peak time-of-use rate for Pacific Gas & Electric’s EV2 rate effective from January– February 202059.

We estimate the baseline charging rate of a particular charging location by assigning a charging level based on previous charging sessions at that location. We round charging rates from those previous sessions down to the nearest charging level; for example, if the average charging rate for an observed session is below the Level 3 rate but above the Level 2 rate, we bin it to the Level 2 rate. These charging levels are U.S. standards, upper bounded by 1.3 kW for Level 1, 6.6 kW for Level 2, 50 kW for Level 3, and 150 kW for Level 465.

By tabulating all charging sessions, we create a baseline charging demand profile for each vehicle. To run a simulation containing more vehicles than present in the dataset, we randomly sample vehicle profiles from the dataset with replacement until we reach the desired total number of vehicles. A sample baseline charging profile with a breakdown of charging levels for 1000 vehicles is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2.

To identify where charging is available to each vehicle, we first cluster the GPS coordinate data of each vehicle’s stops. We use Agglomerative Clustering with complete linkage and a distance threshold of about 50 meters66. This method allows a different number of location clusters for each driver and ensures each location is well defined within a 50-meter radius67. We assume the driver has access to charging at each location for which at least one charging session is recorded. We estimate the maximum charging power for each charger based on all observed sessions for each location, binning as described above. Since fewer than 12% of California public and shared private chargers are Level 3 or above, we assume managed charging is limited to 25 kW to eliminate unrealistic frequent access to fast Level 3 and Level 4 charging and mimic aggregator strategies to protect grid infrastructure from control-induced peaks in demand68.

We implement two charging availability strategies based on each driver’s existing and potential charging sessions. In the main analysis, the existing sessions scenario, we assume charging can only shift within and across existing sessions, namely, times when the vehicle was plugged in. In a sensitivity analysis, the maximum sessions scenario, we assume charging can shift within and across existing and potential sessions, namely, all times when the vehicle was parked where we know it has access to a charger, as identified from the location clustering. Supplementary Fig. 7a depicts the difference between available charging times in both scenarios.

EV charging optimization

We run three separate grid dispatches to optimize each EV’s charging profile and calculate added emissions, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7b. First, we obtain a baseline dispatch with historical demand data with no added EVs. Next, we sample EVs from the dataset with replacement, add their baseline charging demand to the historical demand, and run a second dispatch. Utilizing this prior knowledge of baseline charging demand allows for a better approximation of total demand to feed into the dispatch model and generate an accurate EF signal. The AEF or MEF signal resulting from this dispatch is the input to the optimization problem for managed charging; once we obtain this managed charging profile, we use it for the third grid dispatch to evaluate the impact on emissions.

To simulate managed charging with the AEF or MEF signal, we assume an aggregator solves a convex optimization problem for each EV: minimizing emissions while maintaining minimum battery SOC levels necessary for their driving behavior and respecting constraints on charging access. We assume vehicle-to-grid is not possible. The problem formulation is as follows:

where e is the MEF or AEF signal, p is the charging power, zl and zu are the SOC penalty variables, λ = 1 is the SOC penalty weight, s is the SOC, Q is the EV battery capacity, Δt is the timestep, d is the power used while driving, and η = 0.91 is the charging efficiency. The objective, Eq. (1), includes a linear term to schedule charging during periods of low MEFs or AEFs, as well as a penalty to lessen the impact of charging on battery health. This penalty, which also includes the constraints in Eqs. (8)–(11), regulates the state of charge by limiting the time spent outside the bounds of 20% and 80% SOC.

Equation (2) governs the SOC evolution, while Eq. (3) sets a strict SOC bound. The driving power time series, d, is a fixed input derived from the dataset that is positive when the vehicle is driving and 0 at all other times. We fix the SOC at the beginning and end of each week to allow concatenation of multiple weeks of managed charging (Eqs. (4) and (5)). For the charging constraints, we first limit the charging power to be positive and less than the maximum allowed power at each location (Eq. (6)). Finally, in Eq. (7), we ensure that the vehicle can only charge when parked at a location where charging is available, indicated by set I. p(t) = 0 during all other periods, including while driving and while parked in a place without charging. We solve the optimization problem for one week at a time with 15-minute time intervals to reduce the computation time, resulting in Δt = 0.25 hours and N = 672 data points each week.

Cascading MEF algorithm

The Cascading MEF algorithm uses the same charging optimization problem presented above, but the major difference between this method and the traditional AEF and MEF methods is the signal that each vehicle receives for optimization. As shown in Fig. 2, EVs are managed sequentially in smaller, equal-sized groups. Each group receives a MEF signal for optimization, then its managed demand is used in conjunction with the next group’s baseline demand to re-run the grid dispatch and output the next MEF signal. The signal for each group is calculated using its baseline demand as a proxy, then the proxy is subtracted and replaced with the group’s managed demand using the signal. Supplementary Fig. 8 shows an example of how the Cascading MEF signal is mapped from the generator merit order.

Uncertainty in driver responsiveness to the managed charging signal

We run an additional case with uncertainty in the drivers’ managed charging response as part of a sensitivity analysis. Let \({D}_{i}^{u}\) be the baseline demand of group i and let \({D}_{i}^{c}\) be the managed demand of group i. In the standard Cascading MEF algorithm, the EV demand for group n dispatch is

Therefore, the dispatched demand assumes that all drivers perfectly follow their emissions-minimizing charging signal. To test the Cascading MEF algorithm under uncertainty, we assume that only 75% of vehicles follow this signal, which is modeled as follows.

When calculating subsequent signals, we substitute 25% of the prior groups’ managed demand with baseline demand. This represents a case where those 25% of the drivers ignore the emissions-minimizing charging signal. To model additional uncertainty, we define Duncert by sampling from a normal distribution centered around zero with a standard deviation of the maximum value of 25% of the current group’s baseline demand and add this to the managed demand used in subsequent signal calculations. Lastly, to ensure the new total dispatch demand in kWh is equivalent to the old value, even though the power timeseries values are different, we scale and add Ddisplace. Together, the dispatch demand is

Grid dispatch model

We use an open-source, reduced-order economic dispatch model to simulate the emissions produced at each hour under each demand scenario. The model was first proposed by Deetjen and Azevedo10 and updated by Powell et al.4,32 to represent the years 2020 and 2030. It models the 11 main states in the U.S. portion of the Western Interconnection (WECC) grid, a region with approximately 75 million residents and 48 million personal vehicles32.

The model represents each fossil fuel generating unit in this region, using historical data provided to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through its Continuous Emissions Monitoring Systems (CEMS) to extract each generator’s hourly capacity and emissions rate69. We use information from the EPA’s Emissions and Generation Integrated Resource Database (eGRID) and from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) Form 923 to capture each generator’s construction date, fuel type, location, and fuel prices70,71. Nonfossil generation sources are dispatched first and assumed to have zero cost. Next, fossil generating units are dispatched in order of lowest cost to serve the demand at each hour. We do not represent transmission or trading across grid interconnections. The model does not consider ramping constraints nor, in this implementation, minimum downtime events for coal plants.

Nonfossil fuel generation, including wind, solar, nuclear, and hydropower, is dispatched first. Where Gnonfossil(t) is the total nonfossil fuel generation at time t, we define net electricity demand as

Nonfossil fuel generation never exceeds demand in our simulations for these months and years, so it is never on the margin. To simulate emissions, we dispatch

to the fleet of fossil fuel generators, where DEVs(t) is the EV charging demand.

At hour t, the MEF is defined by the emissions rate of the marginal generator that would ramp up or ramp down production to respond to a small change in demand. The AEF is calculated by dividing the total electricity demand during that hour by the total CO2 emitted during that hour. Both the MEF and AEF have units \(\frac{kg\,{{{\rm{CO}}}}_{2}}{MWh}\).

To model changes to the grid in 2030, we rely on WECC’s announcements and forecasts to incorporate planned fossil fuel generator retirements and additions. For added renewables, we linearly interpolate the new renewable capacity between the 2020 capacity and WECC’s 2035 predictions for solar, wind, and hydropower72. This leads to solar increasing by 176%, wind by 50%, and hydropower by 2%. Nuclear capacity is held constant between 2020 and 2030. We omit storage in our model of the 2020 dispatch as its capacity was only about 500 MW, or approximately 0.01% of total dispatchable capacity73. In 2030, we model storage with a capacity of 16.6 GW72. Lastly, we increase electricity demand by 12.5% compared to 2020 to account for load growth and electrification72. We assume all storage is four-hour storage, meaning it can charge or discharge its full capacity in four hours at a constant rate. We assume it charges during hours of peak solar (11 am–3 pm) and discharges during the four hours of highest net demand each day in a noon–noon time frame. In the 2030 simulations, the storage-adjusted net demand,

is then dispatched to the fossil fuel generators as described above.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The electric vehicle charging data are available at https://doi.org/10.17632/dszk8rzfjx.174. This dataset is a subset of the data published by Balaram et al.75. The input data for the economic grid dispatch data are posted publicly at https://github.com/soniamartin17/cascading-mef-ev-managed-charging. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code developed for this work is available on GitHub at https://github.com/soniamartin17/cascading-mef-ev-managed-charging and at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1714489576.

References

International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2023. Tech. Rep., International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (2023).

Logan, K. G., Nelson, J. D., Brand, C. & Hastings, A. Phasing in electric vehicles: Does policy focusing on operating emission achieve net zero emissions reduction objectives? Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 152, 100–114 (2021).

Tamayao, M.-A. M., Michalek, J. J., Hendrickson, C. & Azevedo, I. M. L. Regional variability and uncertainty of electric vehicle life cycle CO2 emissions across the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8844–8855 (2015).

Powell, S., Martin, S., Rajagopal, R., Azevedo, I. M. L. & de Chalendar, J. Future-proof rates for controlled electric vehicle charging: Comparing multi-year impacts of different emission factor signals. Energy Policy 190, 114131 (2024).

Tang, Y., Cockerill, T. T., Pimm, A. J. & Yuan, X. Reducing the life cycle environmental impact of electric vehicles through emissions-responsive charging. iScience 24, 103499 (2021).

Pepper, J., Miller, G., Maatta, S. & Shahriari, M. Achieving 24/7 Renewable Energy by 2025. Tech. Rep., Peninsula Clean Energy. https://www.peninsulacleanenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/24-7-white-paper-2023.pdf (2023).

24/7 Clean Energy - Data Centers - Google. https://www.google.com/about/datacenters/cleanenergy/.

Greenflux. Smart(er) Charging. https://www.greenflux.com/smart-charging/.

Foley, A. M., Ó Gallachóir, B. P., Hur, J., Baldick, R. & McKeogh, E. J. A strategic review of electricity systems models. Energy 35, 4522–4530 (2010).

Deetjen, T. A. & Azevedo, I. L. Reduced-order dispatch model for simulating marginal emissions factors for the United States power sector. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10506–10513 (2019).

de Chalendar, J. A., Taggart, J. & Benson, S. M. Tracking emissions in the US electricity system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 25497–25502 (2019).

Graff Zivin, J. S., Kotchen, M. J. & Mansur, E. T. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of marginal emissions: Implications for electric cars and other electricity-shifting policies. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 107, 248–268 (2014).

IEA. Trends in electric light-duty vehicles - Global EV Outlook 2023 - Analysis. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/trends-in-electric-light-duty-vehicles (2023).

Kühnbach, M., Stute, J. & Klingler, A.-L. Impacts of avalanche effects of price-optimized electric vehicle charging - Does demand response make it worse? Energy Strategy Rev. 34, 100608 (2021).

Needell, Z., Wei, W. & Trancik, J. E. Strategies for beneficial electric vehicle charging to reduce peak electricity demand and store solar energy. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 4, 101287 (2023).

Kang, Z., Ye, Z., Lam, C.-M. & Hsu, S.-C. Sustainable electric vehicle charging coordination: Balancing CO2 emission reduction and peak power demand shaving. Appl. Energy 349, 121637 (2023).

Anwar, M. B. et al. Assessing the value of electric vehicle managed charging: a review of methodologies and results. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 466–498 (2022).

Li, X. & Jenn, A. Energy, emissions, and cost impacts of charging price strategies for electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5724–5733 (2022).

Daina, N., Sivakumar, A. & Polak, J. W. Modelling electric vehicles use: a survey on the methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 68, 447–460 (2017).

Hardman, S. et al. A review of consumer preferences of and interactions with electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 62, 508–523 (2018).

Schill, W.-P. & Gerbaulet, C. Power system impacts of electric vehicles in Germany: Charging with coal or renewables? Appl. Energy 156, 185–196 (2015).

Weis, A., Michalek, J. J., Jaramillo, P. & Lueken, R. Emissions and cost implications of controlled electric vehicle charging in the U.S. PJM Interconnection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 5813–5819 (2015).

Xu, L., Yilmaz, H. M., Wang, Z., Poganietz, W.-R. & Jochem, P. Greenhouse gas emissions of electric vehicles in Europe considering different charging strategies. Transp. Res. D: Transp. Environ. 87, 102534 (2020).

Manríquez, F., Sauma, E., Aguado, J., de la Torre, S. & Contreras, J. The impact of electric vehicle charging schemes in power system expansion planning. Appl. Energy 262, 114527 (2020).

Lund, H. & Kempton, W. Integration of renewable energy into the transport and electricity sectors through V2G. Energy Policy 36, 3578–3587 (2008).

Blumberg, G., Broll, R. & Weber, C. The impact of electric vehicles on the future European electricity system - A scenario analysis. Energy Policy 161, 112751 (2022).

Jochem, P., Babrowski, S. & Fichtner, W. Assessing CO2 emissions of electric vehicles in Germany in 2030. Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 78, 68–83 (2015).

Jenn, A., Clark-Sutton, K., Gallaher, M. & Petrusa, J. Environmental impacts of extreme fast charging. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094060 (2020).

Jenn, A. & Brown, A. Green Charging of Electric Vehicles Under a Net-Zero Emissions Policy Transition in California. Tech. Rep., Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California, Davis. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rv3h345 (2021).

Arvesen, A. et al. Emissions of electric vehicle charging in future scenarios: The effects of time of charging. J. Ind. Ecol. 25, 1250–1263 (2021).

Nunes, P., Farias, T. & Brito, M. C. Day charging electric vehicles with excess solar electricity for a sustainable energy system. Energy 80, 263–274 (2015).

Powell, S., Cezar, G. V., Min, L., Azevedo, I. M. L. & Rajagopal, R. Charging infrastructure access and operation to reduce the grid impacts of deep electric vehicle adoption. Nat. Energy 7, 932–945 (2022).

Schwarz, M., Auzépy, Q. & Knoeri, C. Can electricity pricing leverage electric vehicles and battery storage to integrate high shares of solar photovoltaics? Appl. Energy 277, 115548 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Emission mitigation potential from coordinated charging schemes for future private electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 308, 118385 (2022).

Huber, J., Lohmann, K., Schmidt, M. & Weinhardt, C. Carbon efficient smart charging using forecasts of marginal emission factors. J. Clean. Prod. 284, 124766 (2021).

Bruchon, M., Chen, Z. L. & Michalek, J. Cleaning up while changing gears: the role of battery design, fossil fuel power plants, and vehicle policy for reducing emissions in the transition to electric vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 3787–3799 (2024).

Powell, S., Cezar, G. V. & Rajagopal, R. Scalable probabilistic estimates of electric vehicle charging given observed driver behavior. Appl. Energy 309, 118382 (2022).

Gschwendtner, C., Knoeri, C. & Stephan, A. The impact of plug-in behavior on the spatial-temporal flexibility of electric vehicle charging load. Sustain. Cities Soc. 88, 104263 (2023).

McLaren, J., Miller, J., O’Shaughnessy, E., Wood, E. & Shapiro, E. CO2 emissions associated with electric vehicle charging: The impact of electricity generation mix, charging infrastructure availability and vehicle type. Electr. J. 29, 72–88 (2016).

Tu, R., Gai, Y. J., Farooq, B., Posen, D. & Hatzopoulou, M. Electric vehicle charging optimization to minimize marginal greenhouse gas emissions from power generation. Appl. Energy 277, 115517 (2020).

Gai, Y., Wang, A., Pereira, L., Hatzopoulou, M. & Posen, I. D. Marginal greenhouse gas emissions of Ontario’s electricity system and the implications of electric vehicle charging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 7903–7912 (2019).

Brinkel, N. B. G., Schram, W. L., AlSkaif, T. A., Lampropoulos, I. & van Sark, W. G. J. H. M. Should we reinforce the grid? Cost and emission optimization of electric vehicle charging under different transformer limits. Appl. Energy 276, 115285 (2020).

Hoehne, C. G. & Chester, M. V. Optimizing plug-in electric vehicle and vehicle-to-grid charge scheduling to minimize carbon emissions. Energy 115, 646–657 (2016).

Sukprasert, T., Bashir, N., Souza, A., Irwin, D. & Shenoy, P. On the Implications of Choosing Average versus Marginal Carbon Intensity Signals on Carbon-aware Optimizations. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Future and Sustainable Energy Systems, e-Energy ’24, 422–427 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1145/3632775.3661953.

Elenes, A. G. N., Williams, E., Hittinger, E. & Goteti, N. S. How well do emission factors approximate emission changes from electricity system models? Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14701–14712 (2022).

Hawkes, A. D. Estimating marginal CO2 emissions rates for national electricity systems. Energy Policy 38, 5977–5987 (2010).

Hawkes, A. D. Long-run marginal CO2 emissions factors in national electricity systems. Appl. Energy 125, 197–205 (2014).

Gagnon, P. & Cole, W. Planning for the evolution of the electric grid with a long-run marginal emission rate. iScience 25, 103915 (2022).

Sheppard, C. J. R., Jenn, A. T., Greenblatt, J. B., Bauer, G. S. & Gerke, B. F. Private versus Shared, Automated Electric Vehicles for U.S. Personal Mobility: Energy Use, Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Grid Integration, and Cost Impacts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 3229–3239 (2021).

Mehlig, D., ApSimon, H. & Staffell, I. Emissions from charging electric vehicles in the UK. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 110, 103430 (2022).

Cheng, K.-W., Bian, Y., Shi, Y. & Chen, Y. Carbon-Aware EV Charging. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm), 186–192 (IEEE, Singapore, Singapore, 2022). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9960988/.

Daneshzand, F., Coker, P. J., Potter, B. & Smith, S. T. EV smart charging: How tariff selection influences grid stress and carbon reduction. Appl. Energy 348, 121482 (2023).

Spitzer, M., Schlund, J., Apostolaki-Iosifidou, E. & Pruckner, M. Optimized integration of electric vehicles in low voltage distribution grids. Energies 12, 4059 (2019).

Li, J., Wang, G., Wang, X. & Du, Y. Smart charging strategy for electric vehicles based on marginal carbon emission factors and time-of-use price. Sustain. Cities Soc. 96, 104708 (2023).

Ensslen, A. et al. Incentivizing smart charging: Modeling charging tariffs for electric vehicles in German and French electricity markets. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 42, 112–126 (2018).

U.S. Department of Energy. Electric Vehicle Registrations by State. https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10962 (2024).

Buechler, E. et al. Global changes in electricity consumption during COVID-19. iScience 25, 103568 (2022).

Han, X., Wei, Z., Hong, Z. & Zhao, S. Ordered charge control considering the uncertainty of charging load of electric vehicles based on Markov chain. Renew. Energy 161, 419–434 (2020).

Pacific Gas & Electric. Electric Rates. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https://www.pge.com/assets/rates/tariffs/Res_Inclu_TOU_200101-200229.xlsx (2020).

Google’s Nest Renew, OhmConnect combine with goal of managing 50 GW of residential demand by 2030 ∣ Utility Dive. https://www.utilitydive.com/news/google-nest-renew-ohmconnect-combine-vpp/715616/.

EnergyHub becomes the first DERMS to exceed 1MM devices under management. https://www.energyhub.com/news/energyhub-becomes-the-first-derms-to-exceed-1mm-devices-under-management.

Muratori, M. Impact of uncoordinated plug-in electric vehicle charging on residential power demand. Nat. Energy 3, 193–201 (2018).

Martin, S., Nnorom, O., Levis, P. & Rajagopal, R. Optimizing software defined battery systems for transformer protection. Appl. Energy 396, 126283 (2025).

Valenzuela, L. F., Degleris, A., Gamal, A. E., Pavone, M. & Rajagopal, R. Dynamic locational marginal emissions via implicit differentiation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 39, 1138–1147 (2024).

Flores, R. J., Shaffer, B. P. & Brouwer, J. Electricity costs for an electric vehicle fueling station with Level 3 charging. Appl. Energy 169, 813–830 (2016).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Day, W. H. E. & Edelsbrunner, H. Efficient algorithms for agglomerative hierarchical clustering methods. J. Class. 1, 7–24 (1984).

Commission, C. E. Electric Vehicle Chargers in California. https://www.energy.ca.gov/data-reports/energy-almanac/zero-emission-vehicle-and-infrastructure-statistics/electric-vehicle (2024). Publisher: California Energy Commission.

US Environmental Protection Agency. Continuous Emissions Monitoring System (CEMS) Data. https://newftp.epa.gov/DmDnLoad/emissions/hourly/monthly/ (2019).

US Environmental Protection Agency. Emissions & Generation Resource Integrated Database (eGRID). https://www.epa.gov/energy/emissions-generation-resource-integrated-database-egrid (2019).

US Energy Information Administration. EIA-923 Monthly generation and fuel consumption time series file. https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/eia923/ (2019).

Western Electricity Coordinating Council. Western Assessment of Resource Adequacy (2022).

Western Electricity Coordinating Council. Resources. https://feature.wecc.org/soti/topic-sections/resources/index.html (2024).

Martin, S., Powell, S., Paxton, W. & Rajagopal, R. California Audi EV Dataset. https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/dszk8rzfjx/1 (2025).

Balaram, D. et al. Graph-based two-level clustering for electric vehicle usage patterns. Energy AI 21, 100539 (2025).

Martin, S. & Powell, S. Cascading Marginal Emissions Factor Charging Control. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17144895.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Volkswagen Group of America (S.M., R.R.), U.S. National Science Foundation through CAREER award number 1554178 (R.R.), and the Stanford Bits & Watts EV50 Initiative with support from the Precourt Institute for Energy (S.P., R.R.). S.P. is also supported by an ETH Postdoctoral Fellowship from ETH Zürich. The authors would like to thank Max Thum for methodology suggestions and running the location clustering code, Mohak Bhimani and Dr. Will Paxton for their useful feedback, Profs. Inês L. M. Azevedo and Thomas Deetjen for their earlier support with the grid model, and the Stanford Research Computing Center for providing computational resources and support that contributed to these research results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. and S.P. designed the study and methodology, carried out the analysis, and wrote and edited the manuscript. S.M. generated the figures. R.R. supervised the work. S.M., S.P., and R.R. conceptualized the work and reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.M., S.P., and R.R. are co-inventors of a provisional patent application on the presented method. The research project was funded in part by Volkswagen Group of America.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alejandro G. N. Elenes, Nicole A. Ryan, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, S., Powell, S. & Rajagopal, R. Cascading marginal emissions signals for green charging with growing electric vehicle adoption. Nat Commun 16, 10150 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64979-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64979-7