Abstract

Metal nanoclusters have served as an emerging class of programmable nanomaterials with customized structures. However, it remains highly challenging to achieve the single-atom regulation of metal nanoclusters without altering their structural frameworks. Here, we achieve the single-point defects manipulation based upon a cluster pair of Au21 and Au22 by meticulously complementing the surface defects of the former nanocluster with an additional single-Au complex. The two nanoclusters exhibited identical geometric structures, but their pronounced quantum-confinement effects resulted in different electronic properties, evident in their distinct optical absorption and emission characteristics. Temperature-dependent steady-state photoluminescence spectra and femtosecond transient absorption spectra showed that the manipulation of a single-point defect in Au22 inhibited non-radiative decay pathways, reduced electron loss at higher energy levels, and accelerated intersystem crossing, which ultimately enhanced its emission intensity. Overall, the Au21 and Au22 cluster system in this study provides a cluster platform with controllable surface single-point defects, enabling the regulation of the photophysical dynamics at the atomic level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoscience has been flourishing since Richard Feynman’s groundbreaking speech about the possibilities of manipulating matter at the atomic level, famously titled “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom”1,2. For a long time, it has been the dream of nanoscientists to master atomic-level manipulations and control the structure of nanomaterials precisely. With the ongoing accumulation of synthetic knowledge and the development of advanced analytical methods, researchers can now tailor the composition and morphology of metal nanoparticles3,4,5,6. However, achieving atomic-level adjustments at specific sites on the nanoparticle surface—such as adding or removing one or two metal atoms at designated positions-remains challenging. These atomic modifications are crucial, as they control the physicochemical properties of the nanomaterials7,8,9,10,11.

Metal nanoclusters are an emerging class of promising nanomaterials due to their atomically precise structures12,13. Their nanoscale sizes endowed these nanoclusters with molecular-like characteristics, featuring discrete electronic energy levels and strong quantum-confinement effects14,15,16. Indeed, the quantum-confinement effects of metal nanoclusters render them programmable nanomaterials with structure-dependent properties, and any perturbations on compositions/structures may induce variations in clusters’ physicochemical performances5,17,18,19. In turn, the atomically precise nature of nanoclusters enables researchers to master the structure-property correlations, which is essential for visualizing the quantum-confinement effects of these nanomaterials20,21,22,23. In this context, it is necessary to develop structurally analogous cluster systems with comparable properties for such a visualization, which requires the atomic-level manipulation of nanoclusters24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, as of now, it remains highly challenging to achieve the single-atom regulation of metal nanoclusters without altering their structural frameworks31,32,33,34,35. Atomic-level understanding of the structure-dependent physical-chemical properties requires newly developed cluster systems as model platforms and precise tools36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43.

Herein, the atomic-level manipulation has been accomplished using two structurally analogous gold cluster molecules, [Au21(AdmS)12(PPh2py)3]+ and [Au22(AdmS)12(PPh2py)4]2+ (abbreviated to Au21 and Au22, respectively), with which the photophysical dynamics of metal nanoclusters have been regulated at the atomic level. Specifically, the single-point defect of the Au21 nanocluster could be complemented by the addition of a single-gold-atom complex, giving rise to its structural analog, the Au22 nanocluster. The maintained structural framework and the single-atom disparity of the two nanoclusters rendered them a platform for visualizing the quantum-confinement effects in determining their photophysical properties. While both cluster analogs maintained a consistent geometric framework, they exhibited evidently different electronic structures and distinct chromatic properties―Au21 displayed reddish-brown absorption, whereas Au22 showed yellowish-green absorption. Additionally, the Au22 showed much brighter photoluminescence (PL) compared to the single-point defective Au21, with PL quantum yields of 47.63% for Au22 and 13.10% for Au21. Such differences in photophysical properties, triggered by the single-atom manipulation, have been unambiguously rationalized using a combination of temperature-dependent steady-state PL spectroscopy and femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy. Our findings revealed that the weaker electron-phonon coupling and faster intersystem crossing (ISC) in Au22 contributed to its enhanced emission intensity.

Results

Synthesis and structural characterization

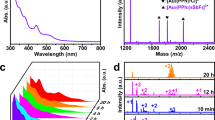

The Au21 nanocluster was synthesized using a one-pot synthetic method by directly reducing Au-AdmS-PPh2py complexes with NaBH4 (Supplementary Fig. 1a; see Methods). The CH2Cl2 solution of Au21 was reddish-brown; however, upon the addition of the AuPPh2pyCl complex to Au21, the solution color altered from reddish-brown to yellowish-green, indicating the cluster transformation from Au21 to Au22, derived from their mass characterizations (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). To assist the sample ionization in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), cesium acetate (CsOAc) was added to the cluster sample. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 1c, 2, two prominent mass signals at m/z of 3549.67 and 3696.46 were detected in the positive mode, which matched well with the chemical formulas of [Au21(AdmS)12(PPh2py)3(CH3OH)Cs+]2+ (calc m/z 3549.68) and [Au22(AdmS)12(PPh2py)4]2+ (calc m/z 3696.34), respectively. In this context, the Au21 and Au22 nanocluster molecules were in “+1” and “+2”-charge states, respectively, demonstrating their identical free valence electron numbers of 8e, i.e., 21(Au) − 12(SR) – 1(charge state) = 8 for the Au22 nanocluster and 22(Au) – 12(SR) – 2(charge state) = 8 for Au21.

Single crystals of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters were cultivated by diffusing hexane into their CH2Cl2 solutions over 7 days, and their atomically precise structures were determined using single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Tables 1,2). The Au21 cluster crystallized in the orthorhombic space group Fddd, while Au22 crystallized in a monoclinic system with a C2/c space group, resulting in distinct packing arrangements within their respective crystal lattices. Structurally, the two nanoclusters exhibited comparably geometric structures while the surface single-point defect of the Au21 nanocluster was complemented by a single-gold-atom complex, giving rise to its structural analog, the Au22 nanocluster (Fig. 1). Specifically, the Au17 core of the Au21 nanocluster could be conceptualized as consisting of a twisted Au11 unit and a twisted Au10 unit that share an Au4 face (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the Au18 core of the Au22 nanocluster was made up of two twisted Au11 units by sharing the same Au4 face (Fig. 1b). While the Au10/Au11 structures here adopted a cuboctahedral shape, their cuboctahedral configuration was distorted. Additionally, the overall structure of Au21, depicted in Fig. 1c,e, featured an Au17 kernel protected by four Au1(SR)2 motifs, four μ2-SR ligands, and three vertex PPh2py ligands. In comparison, the Au22 nanocluster contained the same surface Au1(SR)2 and μ2-SR stabilizers as those found in Au21, while four PPh2py ligands were anchored at vertex positions of the Au18 kernel (Fig. 1d,f). Collectively, the introduced single gold atom would not alter the overall framework of the Au21 nanocluster but fill in its surface defects by anchoring an additional PPh2py stabilizer, giving rise to a structurally analogous nanocluster pair with single-point defects manipulation.

a The Au17 kernel of the Au21 nanocluster comprises one Au11 and one Au10 units by sharing four Au atoms. b The Au18 kernel of the Au22 nanocluster consists of two Au11 units by sharing four Au atoms. c Three PPh2py ligands acting as terminals of the Au17 core. d Four PPh2py ligands acting as terminals of the Au18 core. e Structural anatomy of the Au21 nanocluster with a peripheral single-atom defect. f Structural anatomy of the Au22 nanocluster with a full-protected surface. SR AdmS; PR’ PPh2py. Color legends: light blue sphere and orange sphere, Au; red sphere, S; green sphere, P; light grey sphere, N; grey sphere, C; white sphere, H.

Although the introduction of a single gold atom to the surface defect of Au21 would not alter its overall skeleton, the corresponding bond lengths underwent readjustment. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 3a, the average Au-Au bond length of the Au18 kernel in Au22 was shorter than that of the Au17 kernel in Au21, measuring 2.899 Å compared to 2.953 Å. Moreover, the single-point defect in Au22 caused a notable decrease in both peripheral Au-P and Au-S bond lengths (Supplementary Fig. 3b,c). In this context, at the molecular level, the introduction of a surface single-gold-atom rendered the cluster skeleton more compact, and thus the overall framework of Au22 was more rigid. The comparisons of the metal skeleton and the core size of the two clusters also support this perspective. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, the length and width of the Au22 nanocluster are 9.87 and 10.03 Å, respectively, both shorter than those of the Au21 nanocluster. Additionally, the core of the Au22 cluster is more compact than that of the Au21 cluster. The strengthened structural rigidity of the Au22 nanocluster might enhance the emission intensity of nanoclusters in their molecular states by minimizing vibrational relaxation (discussed below)44,45.

From a supramolecular chemistry perspective, the crystalline packing arrangement of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters in the lattice differed significantly. The intercluster distances between adjacent Au21 molecules were determined as 20.11 and 22.08 Å, while those for Au22 were 17.98 and 19.80 Å, demonstrating that the Au22 cluster molecules were more closely packed in the crystal lattice (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). In addition, several intermolecular hydrogen interactions (H∙∙∙H) were observed between adjacent Au21 nanoclusters with an average interaction length of 2.32 Å (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). By comparison, the crystal lattice of Au22 not only contained several intermolecular H∙∙∙H interactions (average interaction length: 2.43 Å) but also included multiple C-H∙∙∙π interactions (Supplementary Fig. 8c-e). Such rich intermolecular interactions were probably responsible for the more closely packed Au22 clusters in the crystal lattice46,47.

Photophysical properties

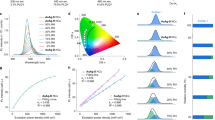

Due to the strong quantum-confinement effect of metal nanoclusters with nanoscale sizes, the single-point defect manipulation would result in differences in the photophysical properties of the Au21/Au22 cluster pair. Indeed, the single-atom regulation has been shown to affect the geometric structures of the two nanoclusters, which would ultimately influence their electronic structures and optical performances. As illustrated in Fig. 2a,b, the CH2Cl2 solution of Au22 displayed intense optical absorption around 590 nm, accompanied by a shoulder band at 470 nm, whereas Au21 presented only a weak and broad peak at 510 nm. The PL properties of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters were then evaluated under ambient conditions. As shown in Fig. 2a,b, strong emissions of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters occurred at 715 and 730 nm, respectively, when the cluster solution was excited at 375 nm. The PL intensity of Au22 was four times greater than that of Au21. In addition, the PL QY of the Au22 nanocluster was determined to be 47.63%, evidently enhanced from the 13.10% of the Au21 nanocluster with a surface single-point defect. The Au22 nanocluster exhibited a refined structure symmetry relative to Au21, which improved the structure rigidity and weakened the framework vibration of the former cluster, resulting in its higher PL intensity. Furthermore, the average PL lifetimes of Au21 and Au22 were measured as 2.65 and 3.82 μs, respectively, and the microsecond lifetimes suggested their analogous phosphorescent characteristic (Fig. 2c,d). To obtain more accurate and direct measurements, we tested the excitation spectra of the two clusters and found a high degree of agreement with their corresponding absorption spectra (Fig. 2a,b; see Methods for test conditions). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, the excitation-dependent emission spectra indicate single sources of Au21 and Au22. In this context, the characteristic peaks of the excitation spectra aligned with the absorption spectra of the two nanoclusters, suggesting that the absorption and emission processes occur at the same energy level48,49.

a Optical absorptions, excitations (PLE), and emissions (PL) of Au21 nanoclusters. b Optical absorptions, excitations (PLE), and emissions (PL) of Au22 nanoclusters. c PL lifetimes of Au21 nanoclusters. d PL lifetimes of Au22 nanoclusters. e Temperature-dependent PL spectra of Au21 nanoclusters dissolved in CH2Cl2. f Temperature-dependent PL spectra of Au21 and of Au22 nanoclusters dissolved in CH2Cl2. g FWHM of the steady-state PL spectra as a function of temperature for Au21 nanoclusters dissolved in CH2Cl2. h FWHM of the steady-state PL spectra as a function of temperature for Au22 nanoclusters dissolved in CH2Cl2.

To investigate the effect of single-point defect manipulation on photophysical and vibration properties of the two gold nanoclusters, we further analyzed their temperature-dependent steady-state PL spectroscopy. A consistent increase in PL intensity was observed for both nanoclusters in their solution state as the temperature decreased from 300 to 200 K (Fig. 2e,f). To better understand the vibrational properties of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters, we extracted the temperature-dependent full width at half maxima (FWHM) of their emission peaks, and the plots are given in Fig. 2g,h. The distribution of FWHMs could be well fitted according to Eq. (1)50,51,52.

Upon where Γ0 was the temperature-independent intrinsic linewidth, Sac and Sop were the coupling strengths for acoustic phonons and optical phonons, respectively, and Eac and Eop were the average energy of acoustic phonons and optical phonons. As illustrated in Fig. 2e–h, the core-directed low-frequency acoustic phonons (4.3 meV for Au21 and 6.9 meV for Au22) barely affected the cluster emission, while the fitted optical phonon energies (36.1 meV for Au21 and 41.6 meV for Au22) indicated that the Au-S vibrations from cluster surfaces or interfaces dominated their non-radiation. The coupling strength of 55.3 meV for Au22 was crucially lower than the value of 137.7 meV for Au21, suggesting a weaker electron-phonon coupling and less PL quenching of the former nanocluster.

Electron dynamics

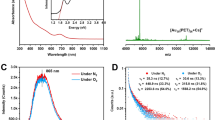

For molecular-state metal nanoclusters, their PL QYs depend not only on the electron transition of the luminescent state but also on the electron relaxation process in the upper energy levels53,54. Femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy was then performed to trace the electron trajectory before reaching the luminescent state. Upon the 400 nm excitation and the 500–750 nm detection, two distinct ground-state bleaching (GSB) dents near 520 and 670 nm were obtained in the 2D-TA map for Au21 (Fig. 3a,c). Given the total positive signal distribution, the very broad excited-state absorption (ESA) should span the entire probe region, and the differences between absorption and GSB peak positions should arise from the ESA modification. For Au22, a main GSB band at 590 nm overlapped with broad ESA was observed, which precisely corresponded to the main absorption peak in steady state, thus reflecting its structure integrity during the measurement (Fig. 3b,d). Of note, the TA signals of Au21 and Au22 underwent essential changes only for the initial few picoseconds, and then converged to a stable situation.

From the TA kinetic traces selected at specific probe wavelengths of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters (Fig. 3e,f), we speculated that at the early part of the TA dynamics, the Au21 nanocluster first showed a faster electron injection process and followed by a slower electron decay process compared to Au22, finally an electron relaxation process exceeding the detector capacity. Global fitting required three decay components to fit the dynamics (0.36 ps, 2.61 ps, and > 1 ns for Au21 and 0.53 ps, 1.11 ps, and > 1 ns for Au22) (Supplementary Fig. 10a–d). The <1 ps dynamics could be explained as the internal conversion (IC) of hot electrons from Sn to the S1 state since the values were importantly reduced under the 530 nm pump (Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). Given the phosphorescent characteristic from the triplet state of the two nanoclusters, the few picoseconds were attributed to their intersystem crossing (ISC). The last >1 ns component accounted for the electron−hole recombination because of their μs-level luminescence lifetimes.

PL mechanism

In this context, the PL mechanisms of Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters were proposed. Given the phosphorescence nature of Au21 and Au22, the excitation light should first pump the ground-state electrons to the excited singlet state, followed by a change in spin direction and eventually relaxed to the luminescent triplet state (Fig. 4a, b). Accordingly, the enhanced PL intensity of the Au22 nanocluster relative to Au21 could be rationalized from the following two aspects: (i) less energy loss in the upper energy levels, where the slower IC indicated more efficient electron relaxation of Au22; 2) faster ISC, which should arise from a reduced energy gap between singlet and triplet for Au22 through the single-point defect manipulation rather than the energy-level splitting induced by strong dipole-dipole interaction (Fig. 4c). Collectively, the single-point defect manipulation endowed the structurally comparable Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters with contrasting photophysical dynamics, and such differences originated from the strong quantum-confinement effects of such small gold nanoclusters.

Discussion

In summary, the surface single-point defects of the Au21 nanocluster could be complemented by an additional single-Au complex, giving rise to its structural analog, the Au22 nanocluster with a maintained framework. Although the Au21 and Au22 nanoclusters exhibited nearly identical geometric structures, their electronic structures were significantly different due to strong quantum-confinement effects. The two nanoclusters manifested distinct photophysical properties, particularly in their optical absorption and emission characteristics. Such differences were rationalized by analyzing their temperature-dependent steady-state PL spectra and femtosecond transient absorption spectra. The single-point defects manipulation on Au22 inhibited the non-radiative decay pathways, reduced the electron loss at elevated energy levels, accelerated intersystem crossing, and ultimately enhanced its PL intensity. Collectively, the Au21 and Au22 cluster system, featuring a controllable single-point defect, provides a platform for visualizing single-atom manipulation effects in determining the photophysical dynamics of metal nanoclusters.

Methods

Materials

Adm-SH was prepared following a method reported in ref. 55. All following reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification, including tetrachloroauric(III) acid (HAuCl4·3H2O, 99% metal basis), diphenyl-2-pyridylphosphine (PPh2py), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 99%), methanol (HPLC grade), ethanol (HPLC grade), dichloromethane (HPLC grade), hexane (HPLC grade), and ethyl ether (HPLC grade).

Synthesis of [Au21(AdmS)12(PPh2py)3]+

300 µL of HAuCl4·3H2O (0.2 g mL−1) and 50 mg of PPh2py were added into a mixed solvent of 10 mL of CH3OH and 10 mL of CH2Cl2, and the solution was stirred vigorously. After 10 min, a freshly prepared solution of NaBH4 (20 mg in 2 mL of water) was added, and the solution color changed to black immediately. Subsequently, 50 mg of Adm-SH was introduced to the solution. The reaction was proceeded for 8 h, after which the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and evaporated to yield the crude product, which was purified three times with CH3OH. Finally, the precipitate (insoluble in CH3OH) was dissolved in CH2Cl2, giving rise to the solution of the Au21 nanocluster, which was used directly in the crystallization process. The yield is 10% based on the Au element (calculated from the HAuCl4·3H2O) for synthesizing the Au21 nanocluster.

Synthesis of [Au22(AdmS)12(Ph2py)4]2+

10 mg of the Au21 nanocluster was dissolved in a 20 mL of CH2Cl2, and 1 mg of AuPPh2pyCl complex was added. The solution color changed from red to green within 30 s, indicating the transformation from Au21 to Au22. The product was purified three times with CH3OH. Finally, the precipitate (insoluble in CH3OH) was dissolved in CH2Cl2, giving rise to the solution of the Au22 nanocluster, which was used directly in the crystallization process. The yield is 86% based on the Au element (calculated from the Au21 nanocluster) for synthesizing the Au22 nanocluster.

Crystallization of [Au21(AdmS)12(PPh2py)3]+ and [Au22(AdmS)12(PPh2py)4]2+

Single crystals of Au21 or Au22 nanoclusters were cultivated at room temperature by liquid diffusion of n-hexane into a CH2Cl2 solution containing the Au21 or Au22 nanocluster. After 7 days, red block crystals for Au21 based on Au and black block crystals for Au22 were collected, and the structures of the Au21 and Au22 nanocluster were determined.

X-ray crystallography

The data collection for single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) of all nanocluster crystal samples was carried out on a Stoe Stadivari diffractometer under nitrogen flow using a graphite-monochromatized Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.54186 Å). Data reductions and absorption corrections were performed using the SAINT and SADABS programs, respectively. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined with full-matrix least squares on F2 using the SHELXTL software package. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and all hydrogen atoms were set in geometrically calculated positions and refined isotropically using a riding model. All crystal structures were treated with PLATON SQUEEZE, and the diffuse electron densities from residual solvent molecules were removed.

Characterizations

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) measurements were performed on a MicrOTOF-QIII high-resolution mass spectrometer. The sample was directly infused into the chamber at 5 μL min−1. For preparing the ESI samples, nanoclusters were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1 mg mL−1) and diluted (v/v = 1:1) with CH3OH. All UV‒vis optical absorption spectra of the nanoclusters dissolved in CH2Cl2 were recorded using an Agilent 8453 diode array spectrometer, whose background correction was made using a CH2Cl2 blank. Nanocluster samples were dissolved in CH2Cl2 to make dilute solutions, followed by spectral measurement. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were measured on an FL-4500 spectrofluorometer with the same optical density (OD) of ≈0.1. Absolute PL quantum yields (PL QYs) and emission lifetimes were measured with dilute solutions of nanoclusters on a HORIBA FluoroMax-4P. Femtosecond-TA spectroscopy was performed on a commercial Ti: Sapphire laser system (Spitfire SpectraPhysics; 100 fs, 3.5 mJ, 1 kHz). Solution samples in 1 mm path length cuvettes were excited by the tunable output of the OPA (pump). Excitation-dependent emission spectra involve adjusting the wavelength (λex) of the excitation light and recording the corresponding emission spectrum using an Edinburgh FLS1000 spectrofluorometer. Excitation spectra were conducted on the FL-4500 spectrofluorometer by fixing the emission wavelength and scanning the excitation wavelength.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Crystallographic data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 2379695 (Au21) and 2379692 (Au22) and are provided as Supplementary Data 1.

References

Hayes, N. K. Nanoculture: implications of the new technoscience. Intellect Books: Bristol, UK, (2004).

'Plenty of room' revisited. Nat. Nanotech. 4, 781 (2009).

Jin, R., Zeng, C. & Chen, Y. Atomically precise colloidal metal nanoclusters and nanoparticles: fundamentals and opportunities. Chem. Rev. 116, 10346–10413 (2016).

Chakraborty, I. & Pradeep, T. Atomically precise clusters of noble metals: emerging link between atoms and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 117, 8208–8271 (2017).

Matus, M. F. & Häkkinen, H. Understanding ligand-protected noble metal nanoclusters at work. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 372–389 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Double-helical assembly of heterodimeric nanoclusters into supercrystals. Nature 594, 380–384 (2021).

Chen, T., Yao, Q., Nasaruddin, R. R. & Xie, J. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: a powerful platform for noble-metal nanocluster analysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11967–11977 (2019).

Deng, G. et al. Alkynyl-protected chiral bimetallic Ag22Cu7 superatom with multiple chirality origins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217483 (2023).

Shi, W.-Q. et al. Near-unity NIR phosphorescent quantum yield from a room-temperature solvated metal nanocluster. Science 383, 326–330 (2024).

Huang, R.-W. et al. [Cu81(PhS)46(tBuNH2)10(H)32]3+ reveals the coexistence of large planar cores and hemispherical shells in high-nuclearity copper nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8696–8705 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Single-atom “surgery” on chiral all-dialkynyl-protected superatomic silver nanoclusters. Sci. Bull. 70, 365–372 (2024).

Fukumoto, Y. et al. Diphosphine-protected IrAu12 superatom with open site(s): synthesis and programmed stepwise assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402025 (2024).

Ma, F., Abboud, K. A. & Zeng, C. Precision synthesis of a CdSe semiconductor nanocluster via cation exchange. Nat. Synth. 2, 949–959 (2023).

Ebina, A. et al. One-, two-, and three-dimensional self-assembly of atomically precise metal nanoclusters. Nanomaterials 10, 1105 (2020).

Shen, H. et al. Photoluminescence quenching of hydrophobic Ag29 nanoclusters caused by molecular decoupling during aqueous phase transfer and emission recovery through supramolecular recoupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317995 (2024).

Silalahi, R. P. B. et al. Hydride-containing 2-electron Pd/Cu superatoms as catalysts for efficient electrochemical hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, 202301272 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Revealing the etching process of water-soluble Au25 nanoclusters at the molecular level. Nat. Commun. 12, 3212 (2021).

Liu, L.-J. et al. NIR-II emissive anionic copper nanoclusters with intrinsic photoredox activity in single-electron transfer. Nat. Commun. 15, 4688 (2024).

Luo, P. et al. Highly efficient circularly polarized luminescence from chiral Au13 clusters stabilized by enantiopure monodentate NHC ligands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202219017 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Anchoring frustrated Lewis pair active sites on copper nanoclusters for regioselective hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27852–27860 (2024).

Swierczewski, M. et al. Exceptionally stable dimers and trimers of Au25 clusters linked with a bidentate dithiol: synthesis, structure and chirality study. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215746 (2023).

Pan, P. et al. Control the single-, two-, and three-photon excited fluorescence of atomically precise metal nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213016 (2022).

Zhu, C. et al. Fluorescence or phosphorescence? The metallic composition of the nanocluster kernel does matter. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205947 (2022).

Kawawaki, T. et al. Toward the creation of high-performance heterogeneous catalysts by controlled ligand desorption from atomically precise metal nanoclusters. Nanoscale Horiz. 6, 409–448 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Boosting CO2 electrochemical reduction with atomically precise surface modification on gold nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 6351–6356 (2021).

Yadav, V. et al. Site-specific substitution in atomically precise carboranethiol-protected nanoclusters and concomitant changes in electronic properties. Nat. Commun. 16, 1197 (2025).

Han, Z. et al. Tightly bonded excitons in chiral metal clusters for luminescent brilliance. Nat. Commun. 16, 1867 (2025).

Pan, P., Kang, X. & Zhu, M. Preparation methods of metal nanoclusters. Chem. Eur. J. 31, e202404528 (2025).

Kang, X. & Zhu, M. Tailoring the photoluminescence of atomically precise nanoclusters. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2422–2457 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Self-assembly of chiroptical ionic co-crystals from silver nanoclusters and organic macrocycles. Nat. Chem. 17, 169–176 (2025).

Zhao, J., Ziarati, A., Rosspeintner, A. & Bürgi, T. Anchoring of metal complexes on Au25 nanocluster for enhanced photocoupled electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316649 (2024).

Deng, G. U. et al. Structural isomerism in bimetallic Ag20Cu12 nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 26751–26758 (2024).

Yao, L.-Y., Qin, L., Chen, Z., Lam, J. & Yam, V. W.-W. Assembly of luminescent chiral gold(I)-sulfido clusters via chiral self-sorting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202316200 (2024).

Tian, W.-D. et al. Lattice modulation on singlet-triplet splitting of silver cluster boosting near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202421656 (2025).

Li, J.-J. et al. A 59-electron non-magic-number gold nanocluster Au99(C≡CR)40 showing unexpectedly high stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 690–694 (2022).

Yan, J., Teo, B. K. & Zheng, N. Surface chemistry of atomically precise coinage-metal nanoclusters: from structural control to surface reactivity and catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 3084–3093 (2018).

Hu, F. et al. Molecular gold nanocluster Au156 showing metallic electron dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17059–17067 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Ligand-protected metal nanoclusters as low-loss, highly polarized emitters for optical waveguides. Science 381, 784–790 (2023).

Ghorai, S., Show, S. & Das, A. Hydrogen bonding-induced inversion and amplification of circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) in supramolecular assemblies of axially chiral luminogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202500879 (2025).

Xu, C.-Q. et al. Observation of the smallest three-dimensional neutral boron cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202419089 (2025).

Zhang, W. et al. Aggregation enhanced thermally activated delayed fluorescence through spin-orbit coupling regulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202404978 (2024).

Zhu, C. et al. Rational design of highly phosphorescent nanoclusters for efficient photocatalytic oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 23212–23220 (2024).

Tang, L. et al. Structure and optical properties of an Ag135Cu60 nanocluster incorporating an Ag135 buckminsterfullerene-like topology. Nat. Synth. 4, 506–513 (2025).

Xiao, Y., Wu, Z., Yao, Q. & Xie, J. Luminescent metal nanoclusters: biosensing strategies and bioimaging applications. Aggregate 2, 114–132 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Atomically engineered trimetallic nanoclusters toward enhanced photoluminescence and photoinitiation activity. Adv. Mater. 37, 2417984 (2025).

Yan, N. et al. Bimetal doping in nanoclusters: synergistic or counteractive?. Chem. Mater. 28, 8240 (2016).

Sakthivel, N. et al. The missing link: Au191(SPh-tBu)66 Janus nanoparticle with molecular and bulk-metal-like properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15799–15814 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Gapped and rotated grain boundary revealed in ultra-small Au nanoparticles for enhancing electrochemical CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202410109 (2025).

Wu, Z., Yao, Q., Zang, S. & Xie, J. Aggregation-induced emission in luminescent metal nanoclusters. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa208 (2021).

Vuong, T. Q. P. et al. Exciton-phonon interaction in the strong-coupling regime in hexagonal boron nitride. Phys. Rev. B. 95, 201202 (2017).

Wu, B. et al. Strong self-trapping by deformation potential limits photovoltaic performance in bismuth double perovskite. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd3160 (2021).

Toyozawa, Y. Theory of line-shapes of the excit.on absorption bands. Prog. Theor. Phys. 20, 53–81 (1958).

Liu, Z. et al. Elucidating the near-infrared photoluminescence mechanism of homometal and doped M25(SR)18 nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19969–19981 (2023).

Tang, J. et al. Two-orders-of-magnitude enhancement of photoinitiation activity via a simple surface engineering of metal nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, 202403645 (2024).

Kang, X., Xu, F., Wei, X., Wang, S. & Zhu, M. Valence self-regulation of sulfur in nanoclusters. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax7863 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support of the NSFC (22371003, 22471001, U24A20480, T2325015 and 12174151), the Ministry of Education, Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (2408085Y006), the University Synergy Innovation Program of Anhui Province (GXXT-2020-053), and the Scientific Research Program of Universities in Anhui Province (2022AH030009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.P. and W.H. conceived, carried out experiments, and wrote the paper. W.D. assisted in the synthesis, optical spectral measurement,s and analyzed the data. Z.W., X.B., X.K., and M.Z. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, P., Dong, W., Huang, W. et al. Regulation of the photophysical dynamics of metal nanoclusters by manipulating single-point defects. Nat Commun 16, 10065 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65024-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65024-3