Abstract

On-chip inductors enable high integration in radio-frequency electronics, critical for compact, power-efficient systems. However, they often occupy a large chip area due to low inductance density (D, defined as the total inductance per unit area) that scales sublinearly with conductor length (l) in planar architectures. Here, we present a three-dimensional rolled-up, magnetically integrated microinductor technology with record-high inductance density. By exploiting a superlinear scaling law (D ∝ l2.4) via 3D winding with magnetic thin films, our devices achieve 8333 nH/mm² at 0.55 GHz—over two orders of magnitude higher than conventional planar inductors. This breakthrough stems from a 3D geometry in which strained layers confine multiple turns in a compact tubular volume, intensifying local fields and flux linkage while reducing leakage. A wafer-scale, CMOS-compatible process yields self-assembled coils that roll 10 mm of planar conductors into ~240 μm-diameter microcoils. The high inductance density, low substrate losses, and GHz operation make magnetically integrated inductors suited for more compact radio-frequency systems-on-chip and high-frequency power modules and next-generation Internet of Things/5G/6G applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The relentless pursuit of miniaturization in modern electronics, spanning from portable devices to high-performance computing systems, has imposed unprecedented challenges on on-chip passive components responsible for energy storage and dissipation in electric or magnetic fields1,2,3,4,5. While substantial progress has been made in scaling resistors and capacitors through advancements in CMOS (complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor) technology6,7, the miniaturization of on-chip inductors remains a critical bottleneck due to the fundamental conflict between inductance scaling laws and geometric constraints8,9. This limitation necessitates relatively large physical dimensions to achieve target inductance values and performance metrics. Conventional planar on-chip inductors, which serve as indispensable components in radio frequency integrated circuits (RF ICs) for Internet of Things (IoT) applications10,11,12, can occupy up to 50% of total chip area9. This significant area consumption creates major barriers to fully integrated radio frequency systems-on-a-chip (RF SoCs) and high-frequency power management ICs in CMOS processes, particularly for compact implementations13,14,15,16. To achieve ultracompact dimensions without sacrificing performance, the development of microinductors with ultrahigh inductance density (D), defined as the total inductance (Ltotal) divided by the footprint (A), is of vital importance.

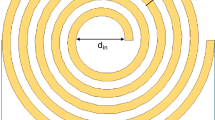

Traditional planar architectures attempt to boost the inductance, including self-inductance Lself and mutual inductance Lmutual, by extending conductor length. However, this inherently enlarges the footprint area (A = wl, where w is the conductor width), thus limiting any net gain in inductance density. Through analytical modeling based on empirical closed-form expressions, we calculated the inductance of the planar inductors in four fundamental configurations (cases 1–4 in Fig. 1a) and investigated the scaling trend against the conductor length (Supplementary Note 1). A straight wire shows Lself ∝ l1.1 with nearly constant inductance density (D ∝ l0.01, case 1 in Fig. 1c). The addition of magnetic materials on top enhances Lself but preserves similar scaling limitation of inductance density (D ∝ l0.01, case 2 in Fig. 1c). Further, in a spiral configuration, the mutual inductance between nearby conductors yields Lmutual ∝ l1.7, enabling D ∝ l0.5 (case 3 in Fig.1b, c). Even magnetic-enhanced spirals follow similar scaling (D ∝ l0.5, case 4 in Fig. 1b, c). Despite integrating magnetic films on both the top and bottom of the conductor (i.e., sandwich structure), the scaling law is only D ∝ l0.6 (Supplementary Note 1). Consequently, in these planar architectures, D adheres to the sublinear scaling with l, fundamentally limiting on-chip inductor miniaturization. Hence, an approach that circumvents footprint-related constraints while sustaining large inductance values is urgently needed.

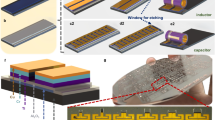

a Schematic of a conductor of length l configured as microinductors in various geometries. In each pair, the first configuration (cases 1, 3, and 5) shows the pure conductor (yellow) as a straight line, a 2D spiral, and a 3D wound structure, respectively, while the second (cases 2, 4, and 6) depicts the corresponding configuration with an additional magnetic layer (blue). b, c Calculated self-inductance and mutual inductance (b) and inductance density (c) versus conductor length for cases 1–6. d Schematic of the proposed RuMi inductor with 6 coil cells rolled up from a planar meander configuration. The equivalent circuit model is shown with Lcell, Rcell and Ccell as the inductance, resistance and capacitance of a single coil cell, Cgap and Mgap as the capacitance and the mutual inductance between the adjacent coil cells, Rs and Cs as the parasitic resistance and capacitance of the substrate, respectively. e Electron microscope image of a fabricated 6-cell RuMi inductor. Scale bar, 100 μm. f Optical image of an array of 40 RuMi inductors. Inset: Optical image of a single RuMi inductor cut from the wafer and placed at the tip of a nipper. Scale bars, 1 mm. g Measured inductance and the Q-factor for 4-cell and 6-cell RuMi inductors with a rolling length of 10 mm. Inset: Optical images of the corresponding 4-cell and 6-cell RuMi inductors. Scale bar, 500 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our breakthrough addresses these limitations through the development of three-dimensional (3D) wound geometries (cases 5–6 in Fig. 1a) that overcomes planar scaling constraints. By vertically winding conductors rather than confining them to planar layouts, the coil radius remains minimally affected by wire thickness, thereby maintaining a nearly constant footprint area (A). Calculated by a discretized Biot-Savart approach, we found that this topological transformation fundamentally alters the scaling law (Supplementary Note 2). For a bare 3D coil, while self-inductance scales linearly, mutual inductance scales approximately quadratically (Lmutual ∝ l2.0, case 5 in Fig. 1b), driving inductance density to D ∝ l1.9 under constant A (Fig. 1c). Integrating a magnetic material layer within the 3D architectures amplifies this effect, yielding in a remarkable boost in self-inductance as Lself ∝ l1.5 and in mutual inductance as Lmutual ∝ l2.5 (case 6 in Fig. 1b). This substantial improvement in scaling arises from two synergistic effects introduced by the 3D magnetic integration. First, once rolled into a 3D coil, the magnetic thin films become sandwiched within the conductor windings so that the magnetic flux generated by these windings is largely parallel to the magnetic layer, thereby intensifying flux coupling in the coil interior. Second, because conductor thickness (typically tens to hundreds of nanometers) is much smaller than its width (a few to tens of micrometers), 3D winding enables a significantly tighter roll than 2D layouts, reducing inter-turn separation and thus further amplifying the local magnetic field and enhancing overall inductance. Given the near-constant footprint area, the resulting superlinear scaling (D ∝ l2.4, case 6 in Fig. 1c) may theoretically yield unprecedented inductance densities, exceeding planar counterparts by more than two orders of magnitude. For instance, for a 10-mm wire with magnetic materials wound in 3D (case 6), D can reach ~40,000 nH/mm2 in theory, while the planar counterpart (case 4) only achieves ~210 nH/mm2 as illustrated in Fig. 1c, with further improvements possible for longer wires.

We experimentally demonstrate this principle through the realization of 3D rolled-up magnetically integrated (RuMi) inductors. We developed a CMOS-compatible fabrication process to transform multiple connected conducting wires (up to 10 mm) integrated with magnetic materials into compact coils (~220–280 μm in diameter). Schematic in Fig. 1d illustrates the rolling process of a RuMi inductor with 6 cells, and the electron microscope image in Fig. 1e highlights the fabricated device. This fabrication process demonstrates exceptional yield about 92% on a 2-inch wafer (Supplementary Fig. 1), with Fig. 1f showcasing a microinductor array containing 40 successfully fabricated devices. The microinductors can be diced from the wafer for subsequent integration with other components, as illustrated in the inset of Fig. 1f. As shown in Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. 2, a 4-cell RuMi inductor, each cell with a 10-mm-long conductor, has 140 μm × 240 μm footprint after rolling, demonstrating 280 nH inductance at 0.55 GHz, translating to D = 8333 nH/mm2. Similarly, a 6-cell RuMi inductor has 320 inductance at 0.50 GHz with a 190 μm × 240 μm footprint, corresponding to D = 7,017 nH/mm2. The inductance density is two orders of magnitude higher than standard planar microinductors (typically D < 100 nH/mm2)17,18 and surpassing previous records. However, the inductance density of the fabricated sample is lower than prediction (Fig. 1c), primarily due to two factors: the increased footprint arising from the spacing between the coil cells, and the presence of their negative mutual inductance (Supplementary Note 3). Unlike conventional methods that rely on thicker magnetic films (typically several micrometers or more) to increase inductance density, at the cost of increased hysteresis and eddy current losses14,19, our method adopts multiple permalloy (50 nm)/tantalum (5 nm) thin film laminates with minimized losses, which demonstrates ideal in-plane anisotropy with low coercivity20. In addition, the rolled-up microstructures exhibit very low substrate loss and parasitic capacitance (equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 1d) because most of the electric and magnetic fields are confined within the microinductor above the substrate21,22. Both low magnetic losses and reduced substrate losses result in the GHz regime operating frequency of our microinductors. Compared with the two mainstream three-dimensional on-chip inductor technologies, namely through-silicon-via (TSV) inductors23,24 and vertically stacked spiral inductors17,25, the RuMi architecture offers both greater process economy and fundamentally superior scaling. Device fabrication is completed in only four conventional lithography steps and avoids costly unit operations such as deep-reactive etching, chemical-mechanical planarization, and thick Cu plating that are essential for TSV coils26, as well as the >10 lithography iterations commonly required for stacked-spiral inductors17 featuring high inductance density (Supplementary Note 4). Beyond this manufacturing advantage, RuMi inductors exhibit a super-linear inductance-density relationship with conductor length (D ∝ l2.40), surpassing both the trend of TSV (D ∝ l0.02) and stacked-spiral inductors (D ∝ l1.77) (Supplementary Note 4), thereby establishing a new performance benchmark for on-chip 3-D inductors. This work establishes a new design paradigm for high-density microinductors, addressing the critical need for ultracompact RF electronics in emerging IoT and 5G/6G applications. The universal superlinear scaling law of inductance density revealed through our analysis provides a fundamental framework for 3D microinductor optimization, transcending specific material or fabrication methods.

Results

Design and fabrication of the RuMi microinductors

We developed a fully CMOS-compatible fabrication process for the RuMi inductors. A Ge sacrificial layer, an Al2O3 protection layer and a SiNx strained bilayer were sequentially deposited on the substrate using electron beam evaporation, atomic layer deposition (ALD) and inductively coupled plasma chemical vapor deposition (ICP CVD), respectively, which are shown as steps 1 and 2 in Fig. 2a. The strained bilayer consists of a low-frequency (LF) SiNx layer with compressive stress and a high-frequency (HF) SiNx layer with tensile stress27. Such stress mismatch enables the self-rolling mechanism upon etching the sacrificial layer, transforming the planar structure into a tubular microstructure28,29. The fabrication process continues with four critical lithography steps. The first lithography and reactive ion etching (RIE) processes define the rolling area (step 3), followed by a second lithography step to pattern the copper (Cu) conducting wires (step 4). An Al2O3 film is then deposited using ALD as an insulating layer between the conducting wires and the subsequent magnetic layer. The third lithography step patterns the magnetic film layer (step 5), consisting of multiple stacks of permalloy (Py, Ni80Fe20) 50 nm/tantalum (Ta) 5 nm laminates deposited using physical vapor deposition (PVD). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the deposited Py and the precise Fe/Ni composition are presented in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. The final steps involve depositing a protective Al2O3 film via ALD (step 6) and performing a fourth lithography to open an etching window for the Ge sacrificial layer (step 7). The controlled release of the structure is achieved through XeF2 gas etching, initiating the self-rolling process from the defined window (step 8)30,31. Figure 2c schematically illustrates the final film stack configuration after rolling, with detailed fabrication parameters provided in the “Methods” section.

a Schematic of the CMOS fabrication process. b Optical images (bottom) of RuMi inductors with 2-6 cells and rolling lengths of 1.2–3.6 mm before rolling, scanning electron microscope images (middle) after rolling, and a finite element simulation result (top) of the rolled-up structure. Scale bars, 200 μm. c Schematic of layer stacks in the rolled-up RuMi inductors. d, e STEM images of the cross-section of the layer stacks. Scale bars, 500 nm for (d) and 100 nm for (e, f) EDS elemental maps of the same cross-section. Scale bar, 100 nm.

The diameter of the rolled-up structures, primarily controlled by the HF/LF SiNₓ bilayer and the thicknesses of the Cu and Py layers, remains nearly consistent regardless of the rolling length or number of coil cells. Figure 2b demonstrates this consistency, showing three RuMi inductors from the same fabrication batch with identical material thicknesses but varying layouts (2-6 coil cells, 1.2–3.6 mm rolling length), achieving similar final diameters of approximately 220 μm (with 4 stacks of Py/Ta laminates, see Supplementary Table 3 for primary dimensional parameters of all samples). We speculate these inductors have approximately 5, 3.5, and 1.7 turns, respectively. We performed finite element simulations of this rolling process, showing good agreement with the experimental results (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Note 5). Furthermore, cross-sectional analysis via scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) reveals the detailed microstructure (Fig. 2d). The films exhibit a slightly curved geometry, corresponding to the tubular structure. As depicted in Fig. 2e, the 380 nm-thick Cu layer as the conductor, the magnetic layer consisting of 4 stacks of Py/Ta laminates, and the insulating Al2O3 layer in between, are clearly visible and intact after the rolling process. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (Fig. 2f) confirms the layer composition, with the observed Cu signal outside the conducting layer attributed to the sample holder during sample preparation by focused ion beam etching, which does not affect the experimental analysis.

Magnetic characterization and inductance enhancement

The integration of magnetic materials with increased thickness and permeability can significantly enhance the inductance of RuMi inductors (Supplementary Note 2). Thin-film Py with in-plane anisotropy has been extensively utilized in microinductors due to its exceptional magnetic properties, including high permeability and low coercivity20,32. However, increasing the thickness of Py films beyond a critical threshold leads to the formation of strip domains with out-of-plane magnetization components, which degrade magnetic softness and reduce permeability33. This phenomenon is accompanied by increased coercivity, resulting in higher hysteresis losses that compromise high-frequency performance34,35,36. Figure 3a presents the hysteresis loop of a 300-nm-thick Py structure, characterized using magneto-optical Kerr effect (MOKE) measurements (see “Methods”), deposited on planar winding conductors prior to the rolling process. Both the hysteresis loop and magnetic force microscopy (MFM) image (inset of Fig. 3a) confirm the presence of strip domains with out-of-plane magnetization components. We note that although the magnetic material is patterned as a long and narrow wire with its long axis along the y-axis in the schematic of Fig. 3a, no clear difference is observed in the hysteresis loops measured along the x- and y-directions. This observation suggests that shape anisotropy effects are minimal in materials exhibiting strip domains.

a, b Hysteresis loops of the magnetic structures formed by a 300-nm thick Py films (a) and 6 stacks of 50 nm Py/5 nm Ta laminates (b) in the RuMi inductors before rolling, measured with the magnetic field applied perpendicular (x-axis) or parallel (y-axis) to the rolling direction. Insets: MFM images of the corresponding films. Scale bars, 500 nm. c, d Electromagnetic finite element simulation results of the cross-sectional magnetic field distribution at 0.5 GHz with an excitation of 1 V for a 6-cell RuMi inductor with 2.4 mm rolling length, (c) before and (d) after integrating 6 stacks of Py/Ta laminates. Scale bar, 50 μm. Insets: magnified views highlighting the field distribution between spiral layers. The white curved regions (rolled conductors) are omitted for clarity. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, f Measured and simulated inductance (e) and Q-factor (f) versus frequency of the same 6-cell, 2.4-mm-long RuMi inductor with or without the integrated magnetic laminates. Inset: measurement setup showing the GSG test structure. Scale bar, 200 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To maintain optimal magnetic properties, we implemented a laminated structure consisting of six stacks of Py (50 nm)/Ta (5 nm) layers (Fig. 3b). This configuration preserves the total magnetic material volume while maintaining ideal in-plane anisotropy, as evidenced by the MFM image (inset of Fig. 3b) showing minimal out-of-plane components. As shown by the hysteresis loops, the elongated, winding geometry of the laminated magnetic patterns induces distinct magnetic anisotropy, with the easy axis aligned along the long axis (y-axis) and the hard axis along the short axis (x-axis) of the magnetic structures. This orientation is particularly advantageous for RF applications, as the alternating magnetic field generated by RF signals aligns with the hard axis, resulting in increased permeability and reduced losses37,38. Post-rolling characterization using vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) confirms the stability of the magnetic properties of the laminated Py films (Supplementary Fig. 5).

To quantify the magnetic enhancement, we employed electromagnetic FEM simulations to analyze the magnetic field distribution in the cross-section of rolled-up structures (Supplementary Note 6). Figure 3c, d compare the magnetic flux density (B) distributions in a 4-cell microinductor before and after integrating the magnetic layers, respectively, operating at 0.5 GHz. The non-magnetic structure exhibits a maximum flux density of 1.1 mT, while the magnetic-integrated version achieves 8 mT. Furthermore, rather than dispersing outside the coil area, the magnetic flux in the integrated structure is more concentrated between and near the conducting wires, leading to significant inductance enhancement. High-frequency characterization was performed using a network analyzer and microwave probe station with GSG (ground–signal–ground) probes (see Methods and inset of Fig. 3c). Inductance and quality factor were extracted from S-parameters, with detailed measurement and calculation procedures provided in Supplementary Note 7. The magnetic-integrated 3D inductor demonstrates a 60% improvement in inductance (28.1 nH at 1.5 GHz) compared to its non-magnetic counterpart (Fig. 3e). Remarkably, the Q-factor experiences only a slight reduction due to the low-loss laminated Py structure (Fig. 3f). The frequency when the Q-factor reaches its maximum drops from 2.5 GHz to 1.5 GHz, likely due to the improvement of L and the increased magnetic losses14. Our simulation results based on the high-frequency equivalent circuit model also agrees well with the experiment data (Supplementary Note 6).

Characterization of the RuMi inductors and the scaling advantage

We conducted a comprehensive comparison of the electrical performance between planar and RuMi inductors, demonstrating significant enhancements in both inductance and Q-factor after the rolling process. A series of RuMi inductors with varying structural parameters were fabricated and characterized (detailed parameters provided in Supplementary Table 3). Figure 4a and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c illustrate the inductance enhancement achieved through the rolling process. Compared to their planar counterparts, RuMi inductors with rolling lengths of 1.2 mm, 2.4 mm, and 3.6 mm exhibit 1.7-fold, 4.8-fold, and 5.5-fold increases in inductance, respectively. This trend confirms the scaling advantage of the rolled-up configuration, with longer wires demonstrating more substantial inductance improvements. Furthermore, the Q-factors of RuMi inductors consistently surpass those of planar devices (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6d–f), primarily due to the dramatic reduction in substrate loss following the rolling process.

a, b Inductance and Q-factor versus frequency for RuMi inductors measured in planar and rolled-up states at different rolling lengths. Each device has 6 coil cells, and 6 stacks of Py/Ta laminates, a 15 μm-wide Cu conductor, and a 10 μm-wide magnetic structure. c, d Measured and theoretical calculation inductance (c) and the maximum Q-factor (d) as functions of rolling length of the RuMi inductors in planar and rolled-up configurations, each with a varying number of cells. The calculated inductance for 2-, 4-, and 6-cell inductors (6 stacks of Py/Ta laminates, 15 μm Cu width, and 10 μm magnetic structure width) scales with l2.4 in the rolled-up state and scales with l1.1 in the planar states, respectively. The shaded regions correspond to the scaling ranges of inductance and the experimental ranges of maximum Q-factor for planar and rolled-up inductors. Error bars show mean ± s.d. (n = 3–5 samples for different rolling length and coil cells). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The performance of RuMi inductors with 2, 4, and 6 cells was systematically characterized across various lengths, both before and after the rolling process (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Figs. 7, 8). Consistent with previous observations, longer rolling lengths result in greater inductance enhancement relative to planar configurations. The electrical performance of RuMi inductors was analyzed via their high-frequency equivalent circuit model (Supplementary Note 6), with theoretical calculation results showing excellent agreement against experimental data. Both experimental and calculation results reveal distinct scaling behaviors: the inductance of RuMi inductors shows a strong nonlinear length dependence (L ∝ l2.4), whereas planar designs follow an approximately linear trend (L ∝ l1.1). This significantly enhanced scaling, combined with the nearly constant footprint of rolled-up structures, translates to a superlinear increase in inductance density (D ∝ l2.4). Additionally, RuMi inductors with more coil cells demonstrate greater inductance enhancement comparing to their planar counterparts. For instance, at a 3.6 mm rolling length, 2−, 4−, and 6-cell configurations show 3.3-fold, 3.9-fold, and 6.7-fold increases, respectively.

The rolled-up configuration of RuMi inductors also displays favorable Q-factor scaling behavior comparing to their planar counterparts. In planar inductors, the maximum Q-factor decreases as the wire length increases from 1.2 mm to 3.6 mm, mostly due to increased substrate loss associated with larger footprints. In contrast, RuMi inductors exhibit the opposite trend, with Q-factors increasing with rolling length (Fig. 4d). This improvement can be attributed to two key factors: (1) the rolled-up structures are predominantly detached from the substrate, minimizing substrate loss; and (2) the substantial inductance enhancement in longer rolled-up structures boosts reactive power more significantly than the associated increase in device loss39,40.

We further investigate the influence of the Cu conductor width (wCu) and the magnetic layer width (wPy) on the electrical performance of RuMi inductors. Figure 5a and Supplementary Fig. 9 present the inductance for six different combinations of (wCu, wPy), as wCu = 15 μm, 30 μm, and 45 μm and wPy = 10 μm, 20 μm, 25 μm, and 40 μm, respectively. The design constraint wPy ≤ wCu is maintained for each combination, as the Py/Ta laminates are deposited atop and smaller than the Cu conductors in our architecture. As shown in the results, increasing wPy for a fixed wCu, or decreasing wCu for a fixed wPy, effectively increases the magnetic material volume within the same layout, resulting in higher inductance. Furthermore, larger wPy values reduce the shape anisotropy within the plane, resulting in increased permeability enhancing inductance41,42. The number of Py/Ta stacks also significantly influences device performance. In principle, additional stacks provide more magnetic material, which enhances inductance. However, as shown in Fig. 5b, implementing 4, 6, and 8 stacks progressively increases the diameter of RuMi inductors. This is because adding more magnetic stacks increases the overall bending stiffness, so under the same stress from the HF/LF SiNx bilayer, the resulting strain is reduced, leading to a larger final diameter. The increased diameter, and consequently the larger cross-sectional area, undesirably reduces inductance (Supplementary Note 2). This trade-off likely explains the observed trend, where inductance initially increases and then decreases with more stacks (Fig. 5c). A similar trend in the Q-factor is observed, reflecting the balance between inductance enhancement and increased magnetic losses with additional magnetic material. Consequently, the geometric parameters of magnetic layers, such as lateral dimensions and Py/Ta stacks, directly modulate their magnetic anisotropy field, while simultaneously influencing the magnetic flux distribution of the rolled-up 3D structure, thereby affecting the electrical performance of RuMi inductors. Based on this analysis, we identified wCu = 15 um, wPy = 10 um, 6 stacks of Py/Ta laminates as optimal design parameters considering inductance and operational frequency. Using these parameters, we fabricated RuMi inductors up to 10 mm long with 6 coil cells, achieving unprecedented inductance in a tiny footprint (Fig. 1g) and thus record-high inductance density. Additionally, the Q-factors can be effectively raised by further increasing the conductor width (wCu from 60 μm to 200 μm) and thickness (tCu from 400 to 600 nm). This method effectively decreased the metal loss in the inductors, resulting maximum Q-factor up to 9.5 that are sufficient for many on-chip inductor applications9,43. Further, adjusting these conductor parameters can effectively tune the self-resonance frequency (e.g., ranging from 5.6 GHz to 7.5 GHz in Fig. 5d,e), providing designers with the flexibility to target specific RF bands.

a Measured inductance of the RuMi inductors for different conductor widths (wCu) and magnetic-structure widths (wPy). All devices have 4 cells, a 2.4 mm rolling length and 6 stacks of Py/Ta laminates. Error bars show mean ± s.d. (n = 3-4 samples for different wCu and wPy). b Measured inner diameter of the rolled-up structure versus the number of Py/Ta laminate stacks, with corresponding optical images (insets). Scale bars, 200 μm. Error bars show mean ± s.d. (n = 5 samples). c Inductance and Q-factor versus frequency for RuMi inductors with different stacks of Py/Ta laminates (Nstacks). All devices have 4 cells and a 3.6 mm rolling length. d Inductance and Q-factor versus frequency for RuMi inductors with different conductor widths (wCu). All devices have two cells and 2 mm rolling length, 600 nm thick of copper and one stacks of Py/Ta laminates. e Inductance and Q-factor versus frequency for RuMi inductors with different thickness of copper (tCu). All devices have two cells, 2 mm rolling length, 200 μm width of copper and one stacks of Py/Ta laminates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. f Benchmark of maximum Q-factor (Qmax) multiplied by inductance density (D) versus frequency, comparing the RuMi inductors in this work with leading 2D or 3D CMOS-compatible magnetic-integrated microinductors17,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57.

Figure 5f benchmarks the inductance area density multiplied by maximum Q-factors versus operating frequency of the proposed RuMi inductors against state-of-the-art counterparts from the literature (see Supplementary Table 4 for detailed information, and Supplementary Fig. 10 for a plot with L×Qmax versus frequency)17,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. Apparently, the proposed RuMi inductors outperform current CMOS-compatible magnetically-integrated 2D and 3D microinductors, meeting the demanding requirements of next-generation on-chip RF integrated circuits.

Discussion

This work fundamentally redefines the scaling paradigm for on-chip inductors through 3D wound architectures with magnetic integration. The RuMi inductors establish a superlinear scaling law of inductance density (D ∝ l2.4) enabled by synergistic 3D flux confinement and optimized magnetic pathways. With a record-breaking density of 8333 nH/mm2 at 0.55 GHz while maintaining wafer-scale fabrication with CMOS compatibility, this technology holds high potential to fundamentally address the miniaturization bottleneck and enable more compact RF SoC design. The structural design of RuMi inductors is relatively simple, and the processing requires only four-step lithography, without any special substrate treatment50 and overheating process14, enabling the integration with current RF/analog technologies with relative ease (a possible integration process is shown in Supplementary Note 8). Additionally, capacitors or resistors can be co-patterned in the rolling area, forming self-assembled passive component networks. Although the planar layout of RuMi inductors initially occupies a large chip area, strategically placing them at the periphery and dicing unused regions (Fig. 1f, inset) can effectively minimize the overall footprint. This approach aligns with commercial RF SoC layouts, where inductors are typically placed at the edges to reduce interference.

Several approaches remain to further enhance inductance density and shrink device dimensions beyond current demonstrations. Stress-engineered nanomembranes could extend winding lengths beyond 10 mm with even smaller radii, while high-permeability materials (e.g., FeCoB57, CoZrTa58) may further amplify flux density. Incorporating 2D material like graphene conductors9 coupled with van der Waals magnets34 could lead to sub-micron coils59,60 with unprecedented inductance density and high Q-factors. Meanwhile, the current planar meander layout (Fig. 1d) could evolve into a spiral structure (though requiring additional insulating layers and vias) with the advantage of the positive mutual inductance between adjacent coil cells. Preliminary calculations and experimental data (Supplementary Note 9) indicate that RuMi inductors with this spiral layout achieve substantially higher inductance density and Q-factors than their meander-based counterparts.

Beyond addressing the longstanding scaling challenge for passive components, this work also paves the way for 3D heterogeneous integration in advanced microelectronics. The ultrahigh-inductance-density RuMi technology can revolutionize power management chips by significantly reducing their footprint while enhancing efficiency and enabling higher switching frequencies61. In quantum computing, ultracompact RuMi inductors as resonators allow dense qubit arrays, thereby facilitating large-scale quantum processors62. In micro-robotics, GHz operation combined with sub-millimeter dimensions supports wireless power transfer via near-field coupling in highly constrained spaces63,64. Moreover, the universal superlinear scaling law, independent of specific material and fabrication methods, could potentially shape RuMi inductors into a cornerstone for next-generation IoT, 5G/6G, and intelligent edge computing that require miniaturized RF devices.

Methods

Fabrication of RuMi inductors

A 50 nm germanium (Ge) layer was deposited on a 2-inch C-plane (0001) sapphire wafer by e-beam evaporation (Kurt J. Lesker Lab 18) as the sacrificial layer. A 10 nm Al2O3 layer was then deposited at 250 °C by atomic layer deposition (Picosun R-200) to protect the Ge sacrificial layer. SiNx was then deposited by inductively coupled plasma chemical vapor deposition (ICP-CVD, PlasmaPro 100) as the strained layer. Specifically, 20 nm low-frequency SiNx was deposited at 360 kHz with compressive stress (~ −1200 MPa) and 20 nm high-frequency stress SiNx was deposited at 13.56 MHz with tensile stress (~ 200 MPa). The stresses of the HF and LF SiNx films are calibrated in a previous publication26.

Then, rolling areas were patterned by the first photolithography (SUSS MA6) step, followed by reactive ion etching (RIE, Trion T2) for 2 min at a pressure of 35 mTorr (30 sccm CF4 and 1 sccm O2 flow) and RF power of 60 W. In the second photolithography process, we used a lift-off process forming the metal electrodes with 10 nm chromium /380 nm copper/10 nm gold electrodes deposited by magnetron sputtering (DETECH DE500DL). Then, a 20 nm Al2O3 layer was deposited by ALD at 250 °C, serving as the insulating layer between the metal layer and the following magnetic layer.

In the third photolithography followed by a lift-off process, magnetic stripes of multiple stacks of 50 nm permalloy/5 nm tantalum laminates deposited by magnetron sputtering (DETECH DE500DL) were defined. Another 10 nm Al2O3 layer was deposited by ALD at 250 °C, serving as the cover layer to avoid any oxidation of the beneath layers and protect the sacrificial layer from etching by XeF2 in the undesired area. Etching windows were opened by the fourth photolithography process and the buffered oxide etch (BOE) etching process. XeF2 vapor was applied to selectively etch the sacrificial Ge layer by XeF2 Dry Etching System (Samco VPE-4F). Finally, the entire structure automatically rolled up and form multi-turn hollow tubular structure.

Characterization of RuMi inductors

Morphological characteristics of the RuMi Inductors were characterized via SEM Zeiss Sigma 300. Optical images are captured via Zeiss Axiolab 5. TEM characterization of the rolled-up metal layer and laminated Py layer is performed by JEOL ARM200F.

Magnetic performance characterization of RuMi inductors

The magnetic performance of laminated Py film was tested by Durham Magneto Optics NanoMoke 3. The hysteresis loops of the rolled-up magnetic-integrated inductors was measured by Quantum Design’s MPMS 3. Magnetic force microscopy images were acquired by Bruker Dimension Icon with a CoCr-coated probe (MESP-V2). All data were measured at room temperature.

RF performance characterization of RuMi inductors

RF performance was measured using a R&S ZNL20 from 10 MHz to 20 GHz, and two port scattering parameters (S-parameters) were obtained. An ‘open-through’ de-embedding procedure was used to calibrate out the RF testing fixture effects. The RF testing fixture was designed to a GSG configuration with 150 μm pitch for 40 GHz probes.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The core code for calculation of the inductance of different physical model is publicly available via GitHub at https://github.com/NanomembraneGroup/RuMi_Inductor.git65. Other code that supports the findings of this study is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Decoutere, S., Carchon, G., Dehan, M. & Mercha, A. Passive on-chip components: trends and challenges for RF applications. Microelectron. Eng. 82, 503–513 (2005).

Khan, M. I., Dong, H., Shabbir, F. & Shoukat, R. Embedded passive components in advanced 3D chips and micro/nano electronic systems. Microsyst. Technol. 24, 869–877 (2018).

Kwon, Y. C., Seol, H. C., Hong, S. K. & Kwon, O. K. Process optimization of integrated SiCr thin-film resistor for high-performance analog circuits. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 61, 8–14 (2014).

El-Kady, M. F. & Kaner, R. B. Scalable fabrication of high-power graphene micro-supercapacitors for flexible and on-chip energy storage. Nat. Commun. 4, 1475 (2013).

Chen, L. Y. et al. Continuous wireless pressure monitoring and mapping with ultra-small passive sensors for health monitoring and critical care. Nat. Commun. 5, 5028 (2014).

Souri, K., Chae, Y. & Makinwa, K. A. A. A 5800-μm2 resistor-based temperature sensor with a one-point trimmed inaccuracy of ±1.2 °C (3σ) from −50 °C to 105 °C in 65-nm CMOS. IEEE Solid-State Circ. Lett. 2, 67–70 (2019).

Gupta, R. et al. Advances in micro and nano-engineered materials for high-value capacitors for miniaturized electronics. J. Energy Storage 55, 105591 (2022).

Burghartz, J. N. & Rejaei, B. On the design of RF spiral inductors on silicon. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 50, 718–729 (2003).

Kang, J. et al. On-chip intercalated-graphene inductors for next-generation radio frequency electronics. Nat. Electron. 1, 46–51 (2018).

Pardue, C. A., Bellaredj, M. L. F., Davis, A. K., Swaminathan, M. & Nakazawa, S. Design and characterization of inductors for self-powered IoT edge devices. IEEE Trans. Compon., Packag., Manuf. Technol. 8, 1263–1271 (2018).

Xu, N., An, Y., Yu, H. & Yang, J. A study of the fully on-chip inductor coils for 30 MHz power regulation applications in energy harvesting, Sensor Networks, and IoT Scenarios. IEEE Sens. Lett. 7, 1–4 (2023).

Mariappan, S., Rajendran, J., Yusof, Y. M., Ramiah, H. & Kantimahanti, A. K. CMOS low-power current source-based tunable inductor for IoT devices. In 2020 4th IEEE Electron Devices Technology & Manufacturing Conference (EDTM). https://doi.org/10.1109/EDTM47692.2020.9117926 (2020).

Chen, Q., Wang, C., Zhang, F., Li, C. & Wang, A. 3D heterogeneous integration enabling future RF ICs. In 2018, IEEE Radio and Wireless Symposium (RWS). 188-190. https://doi.org/10.1109/RWS.2018.8304982 (2018).

Hao, W. et al. Advances and perspectives in magnetic-integrated inductors for RF ICs. IEEE Trans. Mater. Electron Devices 1, 106–120 (2024).

Mathúna, C. Ó, Wang, N., Kulkarni, S. & Roy, S. Review of integrated magnetics for power supply on chip (PwrSoC). IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 27, 4799–4816 (2012).

Wang, K., Qi, Z., Li, F., Wang, L. & Yang, X. Review of state-of-the-art integration technologies in power electronic systems. CPSS Trans. Power Electron. Appl. 2, 292–305 (2017).

Ni, Z. et al. Design and analysis of vertical nanoparticles-magnetic-cored inductors for RF ICs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 60, 1427–1435 (2013).

Zhan, J., Wang, X., Fang, Q., Shi, Z. & Yang, C. Stacked-spiral RF inductors with fully-filled vertical nanoparticle magnetic core. In 2012 IEEE Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium. 367-370 https://doi.org/10.1109/RFIC.2012.6242301 (2012).

Gardner, D. S. et al. Review of on-chip inductor structures with magnetic films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 45, 4760–4766 (2009).

Dastagir, T. et al. Tuning the permeability of permalloy films for on-chip inductor applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 162506 (2010).

Huang, W. et al. On-chip inductors with self-rolled-up SiNx nanomembrane tubes: a novel design platform for extreme miniaturization. Nano Lett. 12, 6283–6288 (2012).

Huang, W. et al. Three-dimensional radio-frequency transformers based on a self-rolled-up membrane platform. Nat. Electron. 1, 305–313 (2018).

Wang, M., Batarseh, I., Ngo, K. D. T. & Xie, H. Design and fabrication of integrated power inductor based on silicon molding technology. In 2007 IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference 1612-1618 https://doi.org/10.1109/PESC.2007.4342237 (2007).

Wang, M. W. M., Ngo, K. D. T., & Xie, H. SU-8 enhanced high power density MEMS inductors. In 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics 2672-2676 https://doi.org/10.1109/IECON.2008.4758379 (2008).

Zolfaghari, A., Chan, A. & Razavi, B. Stacked inductors and transformers in CMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 36, 620–628 (2001).

Jiang, M., Papistas, I. A., & Pavlidis, V. F. Cost modeling and analysis of TSV and contactless 3D-ICs. In Proceedings of the 2020 on Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 519–524 https://doi.org/10.1145/3386263.3406931 (2020).

Tarraf, A., Daleiden, J., Irmer, S., Prasai, D. & Hillmer, H. Stress investigation of PECVD dielectric layers for advanced optical MEMS. J. Micromech. Microeng. 14, 317 (2004).

Froeter, P. et al. Toward intelligent synthetic neural circuits: directing and accelerating neuron cell growth by self-rolled-up silicon nitride microtube array. ACS Nano 8, 11108–11117 (2014).

Schmidt, O. G., Schmarje, N., Deneke, C., Müller, C. & Jin-Phillipp, N. Y. Three-dimensional nano-objects evolving from a two-dimensional layer technology. Adv. Mater. 13, 756–759 (2001).

Khandelwal, A. et al. Self-rolled-up aluminum nitride-based 3D architectures enabled by record-high differential stress. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 29014–29024 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Enhanced photothermoelectric conversion in self-rolled tellurium photodetector with geometry-induced energy localization. Light.: Sci. Appl. 13, 153 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Nanolaminated permalloy core for high-flux, high-frequency ultracompact power conversion. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 28, 4376–4383 (2013).

Hubert, A. & Schäfer, R. Magnetic Domains: The Analysis of Magnetic Microstructures. (Springer, 1998).

Li, Z. et al. Low-pass filters based on van der Waals ferromagnets. Nat. Electron. 6, 273–280 (2023).

Talebian, S., Hojjat, Y., Ghodsi, M. & Karafi, M. R. Study on classical and excess eddy currents losses of Terfenol-D. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 388, 150–159 (2015).

Zezyulina, P. A. et al. Effect of perpendicular anisotropy and eddy currents on the microwave performance of single-layer and multi-layer permalloy films. IEEE Magn. Lett. 7, 1–4 (2016).

Rahman, B. M. F. et al. Application of sub-micrometer patterned permalloy thin film in tunable radio frequency inductors. J. Appl. Phys. 117, 17C121 (2015).

Wang, T. et al. Integrating nanopatterned ferromagnetic and ferroelectric thin films for electrically tunable RF applications. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 65, 504–512 (2017).

Yue, C. P. & Wong, S. S. On-chip spiral inductors with patterned ground shields for Si-based RF ICs. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuit 33, 743–752 (1998).

Hikmat, O. F. & Ali, M. S. M. RF MEMS inductors and their applications—a review. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 26, 17–44 (2017).

Wu, H., Gardner, D. S., Xu, W. & Yu, H. Integrated RF on-chip inductors with patterned Co-Zr-Ta-B films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 48, 4123–4126 (2012).

Wang, N., O’Sullivan, E. J. & Herget, P. Integrated on-chip inductors with electroplated magnetic yokes (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 111, 07E732 (2012).

Lee, T. H. The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits. (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Wang, N. et al. High-Q magnetic inductors for high efficiency on-chip power conversion. In 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting. (IEDM) 35.3.1-35.3.4 https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2016.7838547 (2016).

Gardner, D. S., Schrom, G., Hazucha, P., Paillet, F. & Muthukumar, S. Integrated on-chip inductors using magnetic material (invited). J. Appl. Phys. 103, 07E927 (2008).

Zeng, K., Allen, W. N., Sinani, M., Martinez, C., & Peroulis, D. Magnetic nanoparticle ink for RF integrated inductor applications. In 2014 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS2014). 1-4 https://doi.org/10.1109/MWSYM.2014.6848576 (2014).

Koh, K. et al. High frequency microwave on-chip inductors using increased ferromagnetic resonance frequency of magnetic films. In 2015 28th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS). 208-211 https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMSYS.2015.7050923 (2015).

Xu, W. et al. Improved frequency response of on-chip inductors with patterned magnetic dots. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 31, 207–209 (2010).

Selvaraj, S. L., Haug, M., Cheng, C. S., Dinulovic, D., & Wieland, M. On-chip thin film inductor for high frequency DC-DC power conversion applications. In 2020 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC). 176-180 https://doi.org/10.1109/APEC39645.2020.9124544 (2020).

Huang, W., Yang, Z., Kraman, M. D., Wang, Q. & Li, X. Monolithic mtesla-level magnetic induction by self-rolled-up membrane technology. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay4508 (2020).

Fang, X., Wu, R., Peng, L. & Sin, J. K. O. A novel silicon-embedded toroidal power inductor with magnetic core. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 292–294 (2013).

Sturcken, N., Davies, R., Wu, H., Lekas, M., & Kalnitsky, A. Magnetic thin-film inductors for monolithic integration with CMOS. In 2015 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). 11.4.1-11.4.4 https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2015.7409676 (2015).

Yang, Z. et al. Unleashing the performance of self-rolled-up 3D inductors via deterministic electroplating on cylindrical surfaces. Adv. Mater. Technol. 9, 2400092 (2024).

Koh, K., Park, J., Park, J., Zhu, X., & Lin, L. Core-shell magnetic nanoparticles for on-chip RF inductors. In 2013 IEEE 26th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS). 465-468. https://doi.org/10.1109/MEMSYS.2013.6474279 (2013).

Gao, Y. et al. Significantly enhanced inductance and quality factor of GHz integrated magnetic solenoid inductors with FeGaB/Al2O3 multilayer films. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 61, 1470–1476 (2014).

Zhuang, Y., Vroubel, M., Rejaei, B., Burghartz, J. N. & Attenborough, K. Magnetic properties of electroplated nano/microgranular NiFe thin films for RF application. J. Appl. Phys. 97, 10N305–310N305-3 (2005).

El-Ghazaly, A., White, R. M. & Wang, S. X. Gigahertz-band integrated magnetic inductors. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 65, 4893–4900 (2017).

Sato, N., El-Ghazaly, A., White, R. M. & Wang, S. X. 45° induced magnetic anisotropy for isotropic high-frequency permeability. IEEE Trans. Magn. 51, 1–4 (2015).

Zhao, B., Wan, Z., Liu, Y., Xu, J. & Duan, X. High-order superlattices by rolling up van der Waals heterostructures. Nature 591, 385–390 (2021).

Zhang, E. et al. Graphene rolls with tunable chirality. Nat. Mater. 24, 377–383 (2025).

Lee, F. C. & Li, Q. High-frequency integrated point-of-load converters: Overview. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 28, 4127–4136 (2013).

Gonzalez-Zalba, M. F. et al. Scaling silicon-based quantum computing using CMOS technology. Nat. Electron. 4, 872–884 (2021).

Bandari, V. K. et al. A flexible microsystem capable of controlled motion and actuation by wireless power transfer. Nat. Electron. 3, 172–180 (2020).

Cortese, A. J., Smart, C. L., Wang, T., Reynolds, M. F. & Mceuen, P. L. Microscopic sensors using optical wireless integrated circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 9173–9179 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. High inductance density in CMOS-compatible magnetically integrated 3D microinductors for radio-frequency applications. RuMi_Inductor https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17097203 (2025).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Key Technologies R&D Program of China (2021YFA0715302 to G.H. and 2022YFA1207000 to J.C.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52101214 to J.C. and 62375054 to Y.M.), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (24QA2700700 to J.C.), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (24520750200 to Y.M., 24CL2900200 to Y.M. and 25CL2900202 to Y.M.). Part of the experimental work was carried out in the Fudan Nanofabrication Laboratory, ShanghaiTech Quantum Device Lab and ShanghaiTech Soft Matter Nanofab (No. SMN180827). The computations in this research were performed using the CFFF platform of Fudan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C., L.C., G.H. and Y.M. conceived the project. L.C., Z.Q., S.L. led the designed and fabricated all of the samples, with assistance from Y.W., T.W., Y.H. and W.H., S.L., L.C. and P.L. performed the theoretical calculations and finite element modeling. Z.Q., Z.Z. and L.C. performed the SEM and STEM characterization. L.C. performed the MFM measurements. J.Y., L.C. and L.Z. performed the NanoMOKE and VSM measurements. L.C. and Z.Q. performed the RF electrical measurements. L.C., Z.Q. and S.L. analyzed the data. L.C., J.C., G.H. and Y.M. co-wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.H., Z.Q., S.L., L.C., J.C., and Y.M. are inventors on a patent application related to the three-dimensional (3D) rolled-up, magnetically integrated (RuMi) microinductor technology described in this study. The patent applicant is Fudan University. Patent application number: CN202410810109.5 (status: publication). This patent covers the RuMi microinductors presented in Figs. 1–5. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Karen Dowling and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Qiao, Z., Liu, S. et al. High inductance density in CMOS-compatible magnetically integrated 3D microinductors for radio-frequency applications. Nat Commun 16, 10072 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65032-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65032-3