Abstract

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) based on formamidinium lead iodide (FAPbI₃) demonstrate near-ideal bandgaps approaching the Shockley-Queisser efficiency limit, yet residual MA⁺ from methylammonium chloride (MACl) additives compromises their operational stability under thermal/light stress. Therefore, we developed an α-phase-assisted antisolvent method employing MACl-free precursors to fabricate α-FAPbI3 films. These films exhibit enhanced thermal stability and structural integrity, which were comprehensively characterized using multiple techniques. The optimized devices achieved a 26.1% power conversion efficiency (PCE), ranking among one of the highest reported values for FAPbI3-based inverted PSCs, and exhibit sustained stability under accelerated aging conditions. This strategy resolves the MA⁺-induced degradation bottleneck, paving the way for commercially viable high-performance PSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Achieving high-performance perovskite solar cells (PSCs) hinges on the development of optimal light-absorbing materials. Among these materials, black α-FAPbI3 emerges as a highly promising absorber material due to its ideal optical bandgap and high thermal stability1,2,3. This material is pivotal for advancing both the efficiency and long-term stability of PSCs. However, the large ionic radius of FA⁺ in α-FAPbI3 results in a high Goldschmidt tolerance factor (~0.98), destabilizing the photoactive α-phase at room temperature4,5. This instability triggers a phase transition to the non-photoactive δ-phase (~2.43 eV)6, severely hindering the reproducible fabrication of high-performance α-FAPbI3 and compromising operational stability in practical devices7,8,9,10. To address the structural instability of α-FAPbI3, various strategies involving cation doping or additives have been widely employed in the fabrication of FAPbI3 perovskites11,12,13,14,15,16. For instance, incorporating MA⁺ or Cs⁺ cations at the A-site reduces FA⁺ content, balancing the tolerance factor reduction and enhancing crystal structure stability. Alternatively, the addition of a significant amount of MACl into the precursor solution can lower nucleation and crystallization barriers, thereby controlling the crystallization kinetics of the perovskite film during deposition and enabling the production of FAPbI3 perovskites. However, these strategies involving cation doping or additives come with their own set of challenges. The presence of MA+ poses issues due to its volatility, significantly compromising the thermal stability of the perovskite films. In addition, the uneven spatial distribution of Cs+ within the perovskite film can lead to energy band misalignment between the perovskite and transport layers, thereby impeding charge extraction and transport. Moreover, these strategies have the potential to increase the defect state density at interfaces, accelerating non-radiative recombination and causing substantial losses in open-circuit voltage, efficiency, and stability. Therefore, the development of an efficient method for fabricating pure α-FAPbI3 without the need for extrinsic cation doping is crucial.

In this study, we developed an α-phase-assisted antisolvent method to fabricate high-quality, stable α-FAPbI3 films free of MA+ residue, utilizing an MACl-free perovskite precursor. We observed that conventionally prepared FAPbI3 films, which contain approximately 5.27 mol% MA+ residue due to the use of MACl additives, exhibit reduced thermal stability caused by MA+ volatilization. In contrast, the MA+ residue -free FAPbI3 films demonstrated enhanced compositional stability at elevated temperatures, maintaining their structural integrity under harsh conditions. The resulting FAPbI3 PSCs achieved a PCE of 26.1%, while the corresponding module, with an aperture area of 20.8 cm2, delivered a notable aperture efficiency of 22.1%. Stability tests under one-sun illumination at 55 °C demonstrated operational durability, with the target FAPbI3-based PSCs retaining over 95% of their initial PCE after 1000 h of continuous maximum power point tracking, in contrast to the control devices, which degraded to 60% of their initial efficiency within approximately 500 h. This study demonstrates the feasibility of producing high-performance and stable PSCs without residual MA+, making a significant advancement toward the practical application and scalability of PSCs technology.

Results

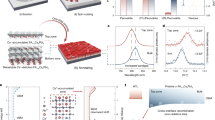

High-quality α-FAPbI3 films of reduced MA+ residue was successfully prepared using α-phase-assisted antisolvent method. Figure 1A presented a schematic illustration of the preparation process of the target FAPbI3 film, using an MACl-free FAPbI3 perovskite precursor to effectively suppresses MA+ residues. Additionally, various additives, including DASCN, FASCN, and MASCN, were investigated for their ability to enhance the formation of high-quality FAPbI3 films when incorporated into the ethyl acetate (EA) antisolvent. However, optical images and XRD characterization revealed that only MASCN as the additive facilitated the successful fabrication of high-quality black-phase FAPbI3 films (Supplementary Fig. 1). The corresponding optoelectronic performance assessments demonstrated that the MASCN-treated films achieved the highest PCE (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, the optical images effectively document the distinct and significant color changes of the films during the fabrication process (Supplementary Fig. 3). The target film underwent a direct phase transition from the wet film to the black α-phase, whereas the control film remained in the yellow δ-phase after antisolvent treatment. The observed difference can be attributed to the use of MASCN as an additive in the antisolvent, which significantly reduces the Gibbs free energy of formation for the α-FAPbI3 (Fig. 1B). DFT calculations (Fig. 1C) further corroborated these findings, revealing that while the incorporation of 5 mol% MAI results in a slight reduction in the formation energy of α-FAPbI3, the introduction of MASCN significantly lowers it, thereby promoting the phase transition of the α-FAPbI3. These findings conclusively demonstrated the α-phase-assisted antisolvent effectively inhibits the formation of the intermediate δ-phase, thereby facilitating the direct crystallization of the α-FAPbI3 during the deposition process. Supplementary Fig. 4 indicated that MA+ plays a crucial role in the formation of α-FAPbI3, as only the additives MAI and MASCN led to the formation of black α-phase powder, whereas FASCN resulted in the yellow δ- FAPbI3.

A Schematic representation of α-FAPbI3 formation using an additive-free FAPbI3 perovskite precursor. B Schematic diagram illustrating the reduction of phase transition energy for α-FAPbI3. C Formation energies calculations of FAPbI3 with FASCN, MAI, and MASCN. D Phase transition process of the unannealed control and target FAPbI3 film. E In situ XRD pattern of control and target FAPbI3 films during the annealing process.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements revealed the intermediate phases of both unannealed control and target FAPbI3 films (Fig. 1D). The unannealed target FAPbI3 film exhibited a prominent diffraction peak at 13.9°, corresponding to α-phase FAPbI3, along with weaker peaks at 11.4° indicative of the δ-phase FAPbI317. In contrast, the unannealed control FAPbI3 film displayed a single peak at 11.4°, characteristic of the δ-phase FAPbI3. Dynamic monitoring of the XRD spectra demonstrated that the formation of α-FAPbI3 begins within 3 s of antisolvent treatment, with significant crystallization occurring after 6 s (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). This observation underscored the efficacy of MASCN in reducing the energy barrier for α-phase formation. To further elucidate the kinetics, we performed in situ XRD during thermal annealing of both control and target films (Fig. 1E). The control film initially showed δ-FAPbI3, which transitioned to a mixture of PbI2 and α-FAPbI3 during heating. This disordered phase evolution—beginning only at t = 2 s—delayed substantial crystallinity improvement until t = 6 s. In stark contrast, the target film exhibited near-complete δ-to-α phase conversion within 2s, bypassing intermediate byproducts. This rapid, direct phase transition directly enhances crystalline quality by minimizing defect-inducing competing pathways18,19.

Photoluminescence (PL) mapping revealed significant spatial variations in PL peak intensities, with the target FAPbI3 film exhibiting a fourfold increase in intensity compared to the control film (Fig. 2A). This substantial enhancement indicated a reduction in non-radiative recombination centers and confirmed improved crystallinity. Supporting this, XRD analysis showed significantly higher intensities for the (100) peak at 13.9° and the (200) peak at 28.0° in the target film, demonstrating high crystalline quality (Supplementary Fig. 7). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (Supplementary Fig. 8) illustrated a distinct morphological evolution: the control film comprises numerous small grains (~0.2 μm) with pronounced wrinkling, while the target film features smoother, larger grains (~2 μm). Notably, this grain size enhancement is evident even in unannealed films (Supplementary Fig. 9) and was attributed to the critical role of MASCN in modulating crystallization kinetics. Specifically, MASCN increased the nucleation energy barrier during mesophase formation, delaying nucleation and leading to more uniform growth, fewer defects, and reduced void formation (Supplementary Fig. 10). However, while optimal MASCN concentrations favored this uniform growth, excessive amounts caused precursor over-solubilization, inducing partial re-dissolution of crystallites during spin-coating and subsequent void formation (Supplementary Fig. 11). Quantitatively, the target film’s enhanced quality is reflected in its average photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 7.6%, a significant improvement over the control’s 2.7% (Fig. 2B), indicating efficient suppression of non-radiative recombination20. The calculated trap density decreased dramatically from 7.25 × 1015 cm−3 in the control to 1.09 × 1014 cm−3 in the target film (Supplementary Fig. 12). Trap density of states (tDOS) measurements further confirmed a reduction in deep-level defects (0.3–0.42 eV) within target PSCs (Fig. 2C), which was critical for minimizing non-radiative recombination losses and enhancing overall device performance.

A PL mapping images of control and target FAPbI3 film. B Quantitative photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of perovskite film. C tDOS spectra of the control and target FAPbI3 devices. D Measurement of residual MA+ content in the control and target FAPbI3 films after annealing. E Origin ToF-SIMS spectra of control and target FAPbI3 films.

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy was employed to quantify the residual MA+ content in both control and target FAPbI3 films (Fig. 2D). The samples were scraped from the perovskite films and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 for 1H NMR analysis. The protons in FA+ generated distinct signals at 9.01, 8.65, and 7.85 ppm, while the 1H NMR resonance at 2.38 ppm was attributed to the -CH3 group in MA+, consistent with our findings (Supplementary Fig. 13). By combining standard samples (Supplementary Fig. 14) and quantifying the integrated NMR resonance signals of the -CH3 for MA+ and -CH for FA+, the molar ratio of MA+ to FA+ in the FAPbI3 films was accurately determined. The control FAPbI3 film, which underwent annealing, contained 5.27 mol% residual MA+, originating from the unannealed film that contained 30 mol% MACl additive (Supplementary Fig. 15 and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, the target FAPbI3 film exhibited negligible residual MA+. Normalized time-of-flight secondary-ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) was used to further validate spatial distribution (Fig. 2E); the original plots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 16. Consistent with NMR, control films exhibited uniform MA⁺ signals throughout the FAPbI3 bulk, confirming homogeneous incorporation of residual MA⁺. In stark contrast, target films showed near-background MA⁺ levels at all depths. This multi-technique convergence robustly confirms both the ultra-low MA⁺ residue and its destabilizing role in conventional approaches. To validate the advantages of MASCN additive, we compared the thermal decomposition behaviors of MASCN and MACl using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Supplementary Fig. 17). The results revealed that MASCN decomposes at a significantly lower temperature (176 °C) than MACl (213 °C), indicating its higher volatility and, consequently, greater ease of evaporation during thermal processing.

Steady-state PL spectra further revealed distinct peak positions for control and target FAPbI3 films, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 18. Specifically, the PL peaks were observed at 810 nm for the control film and 816 nm for the target film, with the latter exhibiting a 6 nm red shift relative to the former. The external quantum efficiency (EQE) spectrum, shown in Supplementary Fig. 19A, demonstrated an improved EQE for the target PSCs across the entire wavelength range of 300–900 nm. The integrated current density (JSC) values derived from the EQE spectra were 23.21 mA/cm2 for the control PSCs and 25.5 mA/cm2 for the target cells. This red shift was further corroborated by the bandgap calculations derived from the EQE data, aligning with the PL analysis results (Supplementary Fig. 19B). These findings highlight the detrimental impact of residual MA+ on the optoelectronic properties of perovskite films.

We conducted a theoretical analysis of the decomposition enthalpy of pure FAPbI3 and FAPbI3 containing 5 mol% MA+ residue using DFT calculation (Fig. 3A). The results revealed that the presence of 5 mol% MA+ residue lowers the decomposition enthalpy of FAPbI3, suggesting that FAPbI3 crystals with MA+ residue is more prone to decomposition (Fig. 3B). To further validate these theoretical predictions, we conducted controlled aging experiments under rigorous thermal and photothermal conditions, using perovskite formulations without excess PbI2 to eliminate its known destabilizing effects. Both FAPbI3 films were subjected to continuous heating at 85 °C for 120 h in a nitrogen environment. The residual MA⁺ content in the control FAPbI3 film decreased from 5.6 mol% to 0.8 mol% after thermal aging, indicating significant degradation of the control film (Supplementary Fig. 20). In contrast, the target FAPbI3 film maintained almost identical properties before and after the aging, demonstrating a significant enhancement in its compositional stability. Moreover, the thermal decomposition of the residual MA+ was accompanied by a notable increase in PbI2 content, as confirmed by XRD measurements (Supplementary Fig. 21). The peak intensity of PbI2 in the aged control FAPbI3 film increased sharply, resulting in a higher intensity ratio of the PbI2 peak to the perovskite (001) peak under external thermal stimulus. Interestingly, no characteristic peak of PbI2 was observed in either the fresh or aged target FAPbI3 film, highlighting its enhanced compositional stability. Both the control and target FAPbI3 films were directly exposed to halogen lamp emitting at 100 mW/cm2 within a nitrogen-filled glovebox. The formation of metallic Pb (Pb0) was confirmed through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 22, the peaks observed at 138.6 eV and 143.5 eV correspond to the Pb2+ 4f7/2 and Pb2+ 4f5/2 states, respectively. After 120 h of light aging, two adjacent peaks were detected at 136.9 eV and 141.7 eV in the control FAPbI3 film, which were attributed to the presence of Pb0. In contrast, the target FAPbI3 films showed no detectable signal of Pb0. These comprehensive results clearly demonstrate that MA+ residue significantly compromises FAPbI3 stability under both thermal and light stress conditions, emphasizing the critical importance of minimizing MA+ incorporation to enhance device stability21,22,23,24.

A Theoretical models of pure FAPbI3 and FAPbI3 with 5 mol% MA+ residue. B Decomposition enthalpy of pure FAPbI3 and FAPbI3 with 5 mol% MA+ residue. C c-AFM images of the control and target FAPbI3 films before and after thermal stress. D Statistical surface current signals of the control and target FAPbI3 films before and after thermal stress. E Steady-state PL spectra of the control and target FAPbI3 films under continuous heating.

Conductive atomic force microscopy (c-AFM) measurements were performed to evaluate the electronic properties of the as-fabricated control and target FAPbI3 films. As shown in Fig. 3C, both the control and target FAPbI3 films displayed homogeneous surface electronic properties in their initial states. However, the target FAPbI3 film showed a significantly higher average surface current signal of 1573 pA, compared to 808 pA for the control FAPbI3 film, indicating superior charge transport capabilities. Upon heating, the surface current signal of the control FAPbI3 film decreased markedly, while the signal for the target FAPbI3 film remained relatively stable. Bar charts presenting the statistical results of the current signals from various samples further validate the significant reduction in the conductivity of the aged target FAPbI3 films, contrasting with the minimal impact on the charge transport capability of the control FAPbI3 films (Fig. 3D). Figure 3E illustrates the steady-state PL peak shift and intensity variations of the perovskite film over time under continuous heating at 85 °C. The observed decline in steady-state PL intensity and the red-shift of the emission peak in the control FAPbI3 film were primarily attributed to the residual MA+ volatilization25,26,27,28. In contrast, the target FAPbI3 film exhibited a significantly smaller decrease in PL intensity and a reduced red shift, further confirming its superior thermal stability.

We then fabricated inverted PSCs with the following structure: ITO/Py3/ Al2O3/FAPbI3/LiF/C60/BCP/Ag, to evaluate their photovoltaic performance. In this device architecture, we employed in-house synthesized (2-(pyren-1-yl)ethyl)phosphonic acid (Py3) as the hole-selective contact material29. The conventional fabrication methods, which do not include MACl additives, typically result in devices with a limited PCE of 15.1% (Supplementary Fig. 23). This is primarily due to the high phase transition barrier of α-FAPbI3. The optimal concentration of MASCN was determined by comparing the performances of the PSCs (Supplementary Fig. 24). The current density-voltage (J–V) curves for the champion control and target PSCs are presented in Fig. 4A. The champion control PSCs achieved a PCE of 22.7% with an open-circuit voltage (VOC) of 1.095 V, a short-circuit current density (JSC) of 25.5 mA/cm², and a fill factor (FF) of 81.4%. In contrast, the best-performing target PSCs attained an enhanced PCE of 26.1% (certified 26.08%, see the certificate in Supplementary Fig. 25) with a higher VOC of 1.163 V, a JSC of 26.5 mA/cm², and an FF of 85.1%, which is one of the highest PCE of FAPbI3-based inverted PSC so far (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table 2). Our method is also compatible with low-temperature processing. Notably, we achieved a PCE of 25.5% at an annealing temperature of 100 °C and 25.9% at 130 °C, demonstrating the versatility of our approach (Supplementary Fig. 26). Statistical analysis also confirmed consistent reproducibility across annealing temperatures (100 °C, 130 °C, 150 °C), with average PCE values of 24.8%, 25.2%, and 23.7%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 27). The target device achieved PCE of 25.5% and 25.0% in reverse and forward scans, respectively, a notable improvement over the control device (22.5% and 21.2%). This result indicates a significantly attenuated hysteresis effect, as evidenced by the reduced discrepancy in PCE between scan directions (Supplementary Fig. 28). At the maximum power point (MPP), the target PSCs maintained a stable PCE of 25.9% over after 300 s (Supplementary Fig. 29). The histogram of PCEs for 20 individual PSCs shown in Fig. 4C confirmed the good reproducibility of the PCE improvement with the target FAPbI3 PSCs, demonstrating a 31.9% increase in average PCE from 19.4 ± 1.9% to 25.6 ± 1.2%. To further validate the universal effectiveness of this special anti-solvent strategy, we extended its application to 1-cm2 PSCs. The champion 1-cm2 PSCs achieved a PCE of up to 24.2%, with a VOC of 1.135 V, a JSC of 25.4 mA/cm², and an FF of 83.9%, outperforming the control device, which had a PCE of 20.1%, a VOC of 1.070 V, a JSC of 24.4 mA/cm2, and an FF of 76.9% (Supplementary Fig. 30A). The statistical distribution of PCEs for the 1-cm2 PSCs, summarized in Supplementary Fig. 30B, further demonstrated the reproducibility of the target PSCs, with an average PCE increasing from 18.1% to 23.7%. To demonstrate its broad applicability and uniqueness, we have now conducted control experiments across two distinct MA-free perovskite systems: FA0.95Cs0.05PbI3 and FA0.85Cs0.15Pb(I0.8Br0.2)3. By applying the same MASCN anti-solvent engineering without cation additives, we achieved PCEs of 26.3% (Figs. 4D) and 22.7% (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. 31), respectively, which are significantly higher than those of the control devices (23.5% and 21.5%) (Supplementary Fig. 31). This strategy was subsequently applied to upscaled solar modules with an aperture area of 20.8 cm2 (Fig. 4F). The target solar module achieved a champion aperture PCE of 22.1%, with a VOC of 11.2 V, a ISC of 53.1 mA, and an FF of 77.2%. In contrast, the best-performing control module showed a PCE of only 17.9 %, with a VOC of 10.3 V, a ISC of 52.2 mA, and an FF of 69.1%. The mini-modules treated with MASCN vapor achieved a PCE of only 16.3% (Supplementary Fig. 32). This substantial improvement underscores the effectiveness of our strategy in enhancing the performance of upscaled solar modules.

A Champion J–V curves of FAPbI3 PSCs. B Comparison of the PCE of device in this work with those of the FAPbI3 inverted PSCs reported in literature. The value of this work is highlighted with a red dot. C Statistical distribution of PCEs for the FAPbI3 PSCs. D Champion J–V curves of FA0.95Cs0.05PbI3 PSCs and E FA0.85Cs0.15Pb(I0.8Br0.2)3 PSCs. F J–V curve of the champion control and target perovskite modules with an aperture area of 20.8 cm2.

The improved power conversion efficiency originates from enhanced carrier extraction and transport. Optimized band alignment between the target FAPbI3 film and C60, driven by the perovskite’s elevated work function, lowers the interfacial energy barrier (Supplementary Fig. 33). This enables efficient electron transfer to the electron transport layer, reducing energy losses. Transient analyses confirm these enhancements: photovoltage decay (TPV) measurements show a 298 μs recombination lifetime in target devices, exceeding the 126 μs observed in controls and indicating suppressed carrier recombination (Supplementary Fig. 34A)30,31. Concurrently, photocurrent decay (TPC) reveals accelerated extraction in target devices (3.7 μs) relative to controls (7.2 μs), demonstrating improved charge collection (Supplementary Fig. 34B). Light-intensity-dependent VOC measurements yield ideality factors of 1.895 for controls and 1.332 for target devices (Supplementary Fig. 35). The target’s near-unity ideality factor signifies reduced interfacial non-radiative recombination, directly explaining VOC enhancement. This reduction is further validated by dark J–V measurements, where target devices display lower reverse saturation current, signifying diminished interfacial trap states (Supplementary Fig. 36). Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) decay dynamics (Supplementary Fig. 37) provide critical insights: target films show substantially prolonged lifetimes (τ₁ = 60.9 ns, τ₂ = 217.7 ns) versus controls (τ₁ = 2.5 ns, τ₂ = 57.5 ns), confirming suppressed non-radiative recombination while promoting radiative channels. Crucially, the extended τ₂ correlates with enhanced external radiative efficiency (EQEEL), where target devices achieve 10.2% versus 1.8% for controls (Supplementary Fig. 38), unambiguously linking defect suppression to performance gains. Consistent with these optoelectronic improvements, the electrical parameters of the target device showed a reduction in series resistance (Rs) from 44.8 ± 15.3 Ω to 24.5 ± 9.2 Ω and an increase in shunt resistance (Rsh) from 5780 ± 4780 Ω to 20,820 ± 13,070 Ω, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 39). These changes indicate suppressed recombination at the interfaces and grain boundaries32,33.

The target FAPbI3 film demonstrated enhanced hydrophobicity, evidenced by a larger contact angle relative to the control film (Supplementary Fig. 40). This improved moisture resistance critically inhibits phase degradation, preserving the photoactive black α-phase of FAPbI3. Accelerated stability testing under high humidity (85% RH, 25 °C) revealed stark differences—control film exhibited visible yellowing within 1 h due to δ-phase formation (Supplementary Fig. 41A), while target film maintains phase integrity throughout testing. Post-degradation XRD analyses confirmed these results, showing complete δ-phase conversion in controls (Supplementary Fig. 41B) versus dominant α-phase retention with only trace impurities in target films. To further investigate the impact of the intrinsic stability of FAPbI3 films on device performance, we fabricated PSCs using thermally aged FAPbI3 films. The statistical distribution of PCE indicated no significant differences in PSC performance between fresh and aged target FAPbI3 films, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 42. In contrast, the performance of PSCs employing aged control FAPbI3 films showed a pronounced decline, decreasing from 20.4 ± 2.7% to 13.8 ± 1.9%.

The changes in PSC performance were monitored over time under accelerated aging conditions following the International Summit on Organic Photovoltaic Stability (ISOS) protocols34. The target PSCs exhibited remarkable stability against both photo-induced and thermal degradation. Specifically, the target devices maintained 95% of their initial PCE after 1800 h of continuous illumination, whereas the control devices experienced a significant performance decay to 30% of initial PCE within merely 200 h (Supplementary Fig. 43). Furthermore, we evaluated encapsulated devices under 85 °C/85% RH dual stress. After 960 h, target devices retained >85% of initial PCE, whereas control devices suffered near-complete failure (Fig. 5A). To further evaluate operational stability, we also conducted maximum power point (MPP) tracking of the control and target PSCs under continuous one-sun light soaking at approximately 35 °C. The target devices maintained about 97% of their initial PCE for over 1000 h, while the PCE of the control PSCs drop to less than 60% after approximately 170 h (Fig. 5B). Cross-sectional high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images of aged devices reveals stark structural differences: control devices exhibit severe structural collapse with indistinct silver electrode and C60 layers (Fig. 5C), while target PSCs maintain fully intact architectures (Fig. 5D). EDX mapping further demonstrates significant silver ionic migration at the perovskite interface in aged controls (Fig. 5E), contrasting sharply with minimal silver penetration and well-defined interfaces in target devices (Fig. 5F). This degradation mechanism originates from MA⁺ volatilization during aging, which triggers perovskite collapse and accelerates Ag migration. Crucially, target films—with negligible MA⁺ residue and superior structural integrity—effectively suppress this cascade. These findings underscore that minimizing MA⁺ residue in FAPbI3 films is essential for enhancing long-term operational stability.

A Evolution of the PCEs tracked under 85 °C/85% RH dual stress following the ISOS-D-2 protocol. B Maximum power point (MPP) tracking of control and target PSCs under continuous one-sun light soaking at ~55 °C. The initial PCEs of the devices are 21.3% and 24.5% for the control and target devices, respectively. Cross-sectional HAADF images and EDX mapping of the (C) control and D target aged devices, respectively. The EDS line scan of the cross-sectional sample of the (E) control and F target aged devices.

Discussion

This study establishes a critical advancement in perovskite photovoltaics by developing α-phase-directed anti-solvent strategy that enables the fabrication of high-quality, MA+ residue-reduced α-FAPbI3 films from MACl-free precursor solution. Our comprehensive investigation provides unequivocal evidence that residual MA+ cations detrimentally affect both the optoelectronic properties and operational stability of FAPbI3 PSCs, inducing bandgap instability and accelerating degradation under thermal and illumination stress. The strategic incorporation of MASCN into the anti-solvent system successfully circumvents these limitations by facilitating the direct formation of phase-pure α-FAPbI3 while ensuring complete MA+ elimination. The resulting inverted FAPbI3 PSCs achieved a remarkable PCE of 26.1% (certified 26.08%), while large-area modules (20.8 cm2) exhibited an aperture efficiency of 22.1% and significantly enhanced durability under accelerated aging tests. The methodology and fundamental insights presented herein represent a significant step forward in the quest for reliable, large-scale perovskite photovoltaic technologies.

Methods

Materials

All materials used in this work were obtained commercially and used without further purification unless otherwise specified. The transparent indium tin oxide glass (ITO, 10 Ω per square, transmittance 88%) was purchased from Advanced Election Technology Co., Ltd. The perovskite raw materials including lead iodide (PbI2, 99.99% purity), lead bromine (PbBr2, purity 99.9%), cesium iodide (CsI, purity 99.999%), formamidinium iodide (FAI, purity 99.99%), Al2O3 dispersions (with a hydrated diameter of 100 nm, dispersed in ethanol), bathocuproine (BCP, purity 99%) and LiF (purity 99.99%) were all purchased from Advanced Election Technology Co., Ltd. Methylamine thiocyanate (MASCN, purity 99.99%), methylammonium chloride (MACl, purity 99.9%) and C60 (purity 99.9%) was purchased from Xi’an E-light New Material Co., Ltd. OAmI (purity 99.9%) were purchased from Xi’an Yuri Solar Co., Ltd. The required solvent, including N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, extra dry, purity 99.8%), isopropanol (IPA, extra dry, purity 99.8%), ethanol (extra dry, purity 99.8%), ethyl acetate (EA, extra dry, purity 99.5%), and was purchased from J&K Scientific. N-Methylpyrrolidone (NMP extra dry, purity 99.9%) was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Inc. The silver (Ag, purity 99.99%) was purchased from Hebei Ancai Advanced Material Technology Co., Ltd. All chemical reagents were used as received without further purification unless otherwise specified.

Perovskite precursor and film preparation

For the control FAPbI3 and FA0.95Cs0.05PbI3, 1.7 M perovskite precursor solution was prepared by dissolving FAI and PbI2 in 1 mL mixed solvent of DMF, NMP, and DMSO at volume ratio 4:1:1. Then additional 5 mol% PbI2 and 30 mol% of MACl were added to the perovskite precursor solution and stirred for 2 h. The filtered perovskite precursor was spin-coated on substrate at 1000 rpm for 3 s and 5000 rpm for 60 s in nitrogen glove box, and 300 µL of EA anti-solvent was dropped quickly at 45 s during the second spinning step. Then these films were annealed at 90 °C for 1 min and 150 °C for 10 min, respectively.

For the target FAPbI3 and FA0.95Cs0.05PbI3, 1.7 M perovskite precursor solution was prepared by dissolving FAI and PbI2 (5% excess) in 1 mL mixed solvent of DMF, NMP and DMSO at volume ratio 4:1:1. The filtered perovskite precursor was spin-coated on substrate at 1000 rpm for 3 s and 5000 rpm for 60 s in nitrogen glove box, and 300 µL of special EA (MASCN) anti-solvent was dropped quickly at 45 s during the second spinning step. Then these films were annealed at 90 °C for 1 min and 150 °C for 10 min, respectively.

For the preparation of perovskite films with a composition FA0.85Cs0.15Pb(I0.8Br0.2)3, 1.65 M perovskite precursor solution was prepared by dissolving CsI, FAI, PbBr2, and PbI2 in 1 mL mixed solvent of DMF and DMSO at volume ratio 4:1. Additional 5 mol% PbI2 was added to the precursor solution, and the solution was stirred overnight. The filtered perovskite precursor was then spin-coated on substrate at 1000 rpm for 10 s and 5000 rpm for 40 s in nitrogen glovebox. Two fifty microliters of CB anti-solvent were dropped quickly at 25 s during the second spinning step. Afterwards, the film was annealed at 110 °C for 30 min.

Fabrication of inverted perovskite solar cell devices

Firstly, the ITO glass was washed with detergent solution, acetone, and absolute ethanol under sonication of 30 min each followed by drying with a pure nitrogen flow. The cleaned and dry ITO substrates were then treated with ultraviolet-ozone for 25 min. To deposit Py3 layer on ITO glass, the Py3 solution with 0.6 mg/mL in mixed solvent of ethanol and DMF at volume ratio 3:1 was spin-coated at 1000 rpm for 10 s and 3000 rpm for 40 s in nitrogen glovebox. The role of adding DMF as a co-solvent is to improve the dispersion of the molecules in the solvent, as reported elsewhere35. Afterwards, the film was annealed at 120 °C for 10 min. Then, the Al2O3 dispersion was deposited on the Py3 layer at 3000 rpm for 40 s. The Al2O3 film was annealed at 110 °C for 10 min. Perovskite films were coated on Py3 layer following the abovementioned method. OAmI/IPA solution was used for surface passivation as reported elsewhere. After cooling down to room temperature, the whole device was transferred to a vacuum chamber under a base pressure of <5.0 × 10−6 Pa. 0.8 nm LiF, 40 nm C60, 6 nm BCP, and 120 nm Ag electrode were thermally evaporated on the perovskite thin film sequentially (AE, Angstrom Engineering Inc). A ~120 nm MgF2 was also evaporated at the glass side to minimize the reflection losses from the glass substrates.

Device characterization

The J–V characteristics of photovoltaic devices were established in a N2-filled glovebox at room temperature using a xenon lamp solar simulator (Enlitech, SS-F5, Taiwan). The power of the light was calibrated to 100 mW/cm2 by a silicon reference cell (with a KG2 filter). The J–V characteristics of photovoltaic cells were taken using a Keithley 2400 source measure unit under a simulated AM 1.5 G spectrum, with an Oriel 9600 solar simulator. Typically, the devices were measured in reverse scan (1.20 V → 0 V, step 0.02 V). All the devices were measured without pre-conditioning, such as light-soaking, and applied a bias voltage. Steady-state power conversion efficiency was calculated by measuring stabilized photocurrent density under a constant bias voltage. External quantum efficiency (EQE) measurements were carried out using a QE-R EQE system (Enlitech, Taiwan). Highly sensitive EQE was measured by an integrated system (PECT-600, Enlitech, Taiwan) in which the photocurrent was amplified and modulated by a lock-in instrument. EQE-EL values of perovskite films were collected by a commercialized system (LQE-50X-EL, Enlitech) that was equipped with an integrated sphere and a photomultiplier tube.

Device stability test

The devices were encapsulated by a glass-glass encapsulation technology combined with an edge seal (UV Curing Sealant, three bond 3035B) to seal the device under UV light illumination (LED flood lamp, DELOLUX 20) in a N2-filled glovebox. A piece of black tape was attached to the exterior of the cover glass to protect the solar cell during UV curing. Indium solar ribbon was used to protect the evaporated metal electrode of the solar cells. To measure the environment-light stability of the encapsulated devices following the ISOS-L-1 protocol, we stored devices at constant photo in the environmental test chamber. The encapsulated devices were measured periodically under AM 1.5 G illumination (100 mW/cm2) in ambient air at ~35 °C. The thermal stability test of the device, following the ISOS-D-2 protocol, was conducted under 85 °C/85% RH dual stress. The PCEs of the devices were tracked over time, and the J–V measurements were performed after cooling the devices down to room temperature. The operational stability tests were carried out at the maximum power point (MPP) under AM 1.5 G illumination (100 mW/cm2) at ~55 °C. The voltage at the MPP was automatically applied, and the power output of the devices was tracked.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analysis

The EDX mapping of the cross-sectional PSCs was investigated in TEM (Talos F200X G2, Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with EDX and HAADF detectors in STEM mode at 200 kV operating voltage. Sample preparation involved creating a cross-sectional lamella in a scanning electron microscope (Helios 5 UX, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with an EasyLift nanomanipulator, aided by a Ga-focused ion beam (FIB). Protective carbon and platinum layers were deposited on the sample using electron and ion beams to prevent damage.

Material characterization

Solution NMR analysis was measured by 500 MHz solution NMR spectrometer with a room temperature probe (Bruker Biospin). UV-vis absorption spectra of the perovskite films were obtained using a Shimadzu UV-VIS-NIR (UV3600Plus + UV2700) equipped with integrating sphere, in which monochromatic light was incident to the substrate side. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were carried out on an XPS (ThermoFisher ESCALAB Xi+). An Al Kα (1486.6 eV) X-ray was used as the excitation source. XRD data were collected in reflection mode at room temperature on a D8 advance diffractometer equipped with a 1D LynxEye detector using monochromated Cu-Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) radiation. SEM was carried out on the Field Emission Environment Scanning Electron Microscope of QuattroS. For TRPL measurement, the sample was excited with a picosecond pulsed diode laser (Pico-quant LDH 450), with a ∼70 ps pulse width and 20 MHz repetition rate, focused on sample with a 100x objective (NA = 0.90). PLQY values of perovskite films were collected by a fibre-coupled spectrometer, paired with a 405 nm power-tunable CW laser to photoexcite the films within an integrating sphere. The power of the excitation light is precisely measured utilizing a calibrated power meter. The PL signal was acquired through the TCSPC strobelock system. The total instrument response function (IRF) for the PL decay was less than 200 ps, and the temporal resolution was less than 30 ps. The energy density of laser for TRPL measurements was 26.46 nJ/cm2. Photoluminescence (PL) apping was measured on alpha 300 R (WITec GMBH, Germany) confocal TA Raman system. Transient photovoltage decay (TPV) under the open-circuit condition and transient photocurrent decay (TPC) under the short-circuit condition were conducted by Photo-Electrochemical measurement system. Conductive atomic force microscope (c-AFM) was measured with the machine (Cypher ES Oxford Instruments) by a bias of 500 mV. A Time-of-Flight Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) (ION-TOF TOF-SIMS V) was used to depth-profile the perovskite materials and completed devices. Analysis was completed using a 3-lens 30-kV Bi-Mn primary ion gun; the Bi+ primary-ion beam (operated in bunched 4 mode; 10-ns pulse width, analysis current of 1.0 pA) was scanned over a 25 × 25-µm area. Depth profiling was accomplished with a 1-kV oxygen-ion sputter beam (10.8 nA sputter current) raster of 150 × 150 µm area. All spectra during profiling were collected at a primary ion dose density of 1 × 1012 ions/cm2 to remain at the static-SIMS limit.

DFT calculations

We performed the computational part of this study using the density functional theory (DFT) and first-principles calculations. The VASP package was used with a plane-wave basis set and the projected augmented wave (PAW) method36,37. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional, which incorporates a generalized-gradient approximation for the exchange-correlation functional, was employed for both the self-consistent field calculations and geometry optimization38. For the geometry optimizations, a 4 × 4 × 1 Γ-centered k-mesh and a plane wave basis with an energy cutoff of 500 eV were utilized. To ensure relaxation, the atomic positions and cell volumes were adjusted using a conjugate gradient algorithm until all residual forces were below 0.01 eV/Å.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Min, H. et al. Efficient, stable solar cells by using inherent bandgap of α-phase formamidinium lead iodide. Science 366, 749–753 (2019).

Wei, Q. et al. Photoelectric performance and stability comparison of MAPbI3 and FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy 174, 933–939 (2018).

Jiang, Q. et al. Rapid advances enabling high-performance inverted perovskite solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 399–419 (2024).

Masi, S. et al. Stabilization of black perovskite phase in FAPbI3 and CsPbI3. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 1974–1985 (2020).

Cui, X. et al. Recent progress on the phase stabilization of FAPbI3 for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Sol. RRL 6, 2200497 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Stabilization of highly efficient and stable phase-pure FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells by molecularly tailored 2D-overlayers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15688–15694 (2020).

Kim, M. et al. Methylammonium chloride induces intermediate phase stabilization for efficient perovskite solar cells. Joule 3, 2179–2192 (2019).

Ye, F. et al. Roles of MACl in sequentially deposited bromine-free perovskite absorbers for efficient solar cells. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007126 (2021).

Zhou, T. et al. Inhibiting the decomposition of methylammonium using cations with low deprotonation energy. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 22742–22749 (2022).

Jeangros, Q. et al. In situ TEM analysis of organic–inorganic metal-halide perovskite solar cells under electrical bias. Nano Lett. 16, 7013–7018 (2016).

Lu, H. et al. Vapor-assisted deposition of highly efficient, stable black-phase FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. Science 370, 8985 (2020).

Du, T. et al. Additive-free, low-temperature crystallization of stable α-FAPbI3 perovskite. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107850 (2022).

Shang, M. et al. “Visible” phase separation of MAPbI3/δ-FAPbI3 films for high-performance and stable photodetectors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2100266 (2021).

Peng, W. et al. Solution-grown millimeter-scale Mn-doped CsPbBr3/Cs4PbBr6 crystals with enhanced photoluminescence and stability for light-emitting applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 373–380 (2024).

Gao, H. et al. Low-temperature synergistic effect of MA and Cl towards high-quality α-FAPbI3 films for humid-air-processed perovskite solar cells. Dalton Trans. 53, 136–147 (2024).

Hernandez, L. H. et al. The role of A-site composition in the photostability of tin–lead perovskite solar cells. Sustain. Energy Fuels 6, 4605–4613 (2022).

Sidhik, S. et al. Two-dimensional perovskite templates for durable, efficient formamidinium perovskite solar cells. Science 384, 1227–1235 (2024).

Ge, R. et al. Kinetics controlled perovskite crystallization for high performance solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319282 (2024).

Jiao, B. et al. Realizing stable perovskite solar cells with efficiency exceeding 25.6% through crystallization kinetics and spatial orientation regulation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2313673 (2024).

Park, J. et al. Controlled growth of perovskite layers with volatile alkylammonium chlorides. Nature 616, 724–730 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. Organoammonium-Ion-based perovskites can degrade to Pb0 via amine–Pb (II) coordination. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2262–2267 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Photostability of MAPbI3 perovskite solar cells by incorporating black phosphorus. Sol. RRL 3, 1900197 (2019).

Liu, G. et al. Mixed-phase low-dimensional perovskite-assisted interfacial lead directional management for stable perovskite solar cells with efficiency over 24%. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 4395–4404 (2021).

Deng, X. et al. Benzotriazole derivative inhibits nonradiative recombination and improves the UV-stability of inverted MAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. J. Energy Chem. 65, 592–599 (2022).

Kang, D.-H. et al. Effect of residual chloride in FAPbI3 film on photovoltaic performance and stability of perovskite solar cell. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2122–2129 (2023).

Li, S. et al. High-efficiency and thermally stable FACsPbI3 perovskite photovoltaics. Nature 635, 82–88 (2024).

Chen, R. et al. Reduction of bulk and surface defects in inverted methylammonium- and bromide-free formamidinium perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 8, 839–849 (2023).

Li, H. et al. 2D/3D heterojunction engineering at the buried interface towards high-performance inverted methylammonium-free perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 8, 946–955 (2023).

Zhao, K. et al. Peri-Fused polyaromatic molecular contacts for perovskite solar cells. Nature 632, 301–306 (2024).

Wang, R. et al. Caffeine improves the performance and thermal stability of perovskite solar cells. Joule 3, 1464–1477 (2019).

Wang, R. et al. Constructive molecular configurations for surface-defect passivation of perovskite photovoltaics. Science 366, 1509–1513 (2019).

Truong, M. A. et al. Tripodal triazatruxene derivative as a face-on oriented hole-collecting monolayer for efficient and stable inverted perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7528–7539 (2023).

Caprioglio, P. et al. On the origin of the ideality factor in perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2000502 (2020).

Khenkin, M. V. et al. Consensus statement for stability assessment and reporting for perovskite photovoltaics based on ISOS procedures. Nat. Energy 5, 35–49 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Compact hole-selective self-assembled monolayers enabled by disassembling micelles in solution for efficient perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304415 (2023).

Kresse, G. et al. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. et al. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Komsa, H.-P. et al. Alignment of defect levels and band edges through hybrid functionals: effect of screening in the exchange term. Phys. Rev. B 81, 205118 (2010).

Acknowledgements

All the authors thank Xiaohe Miao, Lin Liu, and Taofei Zhou from Instrumentation and Service Center for Physical Sciences (ISCPS), Xingyu Lu, Yinjuan Chen, Zhong Chen, and Yuan Cheng from Instrumentation and Service Center for Molecular Sciences at Westlake University for the assistance in the characterizations. R.W. acknowledges a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 62474143), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province of China (grant nos. LD24E020001 and QKWL25E1301), and support from the Key R&D Program of Zhejiang (2024SSYS0061). J.X. acknowledges grants (grant nos. LR24F040001, LDG25E020001) from the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province of China, the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 62274146), the support from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (226-2022-00200), the grant from the Research and Development Foundation of Dongfang Electric (Hangzhou) Innovation Institute Co., Ltd. (grant no. 4F-CSC24005), and Zhejiang Province's Vanguard and Leader Geese Research and Development Program (2024C01246(SD2)). This work was also supported by the Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Low-Carbon Intelligent Synthetic Biology (2024ZY01025) and Muyuan Laboratory (programme ID 14136022401). L.Y. acknowledges the grant by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 62204209).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z. and L.Y. conceived the idea. K.Z. and L.Y. did the device fabrication and characterization under the supervision of J.X. and R.W. C.D. and I.Y. conducted the theoretical calculations. X.Z., J.S., X.M., P.S., Y.L., D.J., Y.T., J.Xu, S.Z.Q., L.S, C. X.W. and L.T. assisted with the device fabrication and characterizations. K.Z. wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, K., Yao, L., Değer, C. et al. Mitigating residual MA+ for stable FAPbI3 perovskite photovoltaics. Nat Commun 16, 10074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65045-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65045-y