Abstract

Jet flavour tagging enables the identification of jets originating from heavy-flavour quarks in proton–proton collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, playing a critical role in its physics programmes. This paper presents GN2, a transformer-based flavour tagging algorithm deployed by the ATLAS Collaboration that represents a different methodology compared to previous approaches. Designed to classify jets based on the flavour of their constituent particles, GN2 processes low-level tracking information in an end-to-end architecture and incorporates physics-informed auxiliary training objectives to enhance both interpretability and performance. Its performance is validated in both simulation and collision data. The measured c-jet (light-jet) rejection in data is improved by a factor of 3.5 (1.8) for a 70% b-jet tagging efficiency, compared to the previous algorithm. GN2 provides substantial benefits for physics analyses involving heavy-flavour jets, such as measurements of Higgs boson pair production and the couplings of bottom and charm quarks to the Higgs boson, and demonstrates the impact of advanced machine learning methods in experimental particle physics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC)1 is the world’s most powerful particle collider. It is used to extend the boundaries of our understanding of fundamental particles and their interactions. It offers a unique opportunity to test the Standard Model (SM) of particle physics, as well as search for new phenomena beyond the Standard Model (BSM). The demanding experimental conditions at the LHC necessitate continuous innovation by the main experiments, pushing them to apply cutting-edge technologies to efficiently identify physics processes of interest within the largest proton–proton (pp) collision dataset ever recorded. Hadronic jets, collimated streams of particles initialised by quarks or gluons, are the most abundant physics objects in pp collision events, and their characteristics are widely utilised in data analyses.

The flavour of a hadronic jet is determined by the types of hadrons or leptons it contains. Flavour tagging concerns the classification of hadronic jets into those containing b-hadrons (b-jets), c-hadrons (c-jets), hadronic τ-lepton decays (τ-jets), and none of the above (light-jets), using algorithms sensitive to the distinctive properties of the respective classes. Since the beginning of Run 1 of the LHC (2009–2013), the ATLAS experiment2,3 has achieved continuous improvement in the performance of these algorithms. The progress has mostly been driven by the integration of machine-learning techniques, including boosted decision trees and neural networks. The state-of-the-art algorithms used thus far to analyse the data at \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) from Run 2 of the LHC (2015–2018)4,5 led to very impactful physics results such as the observations of the Higgs boson decaying to bottom quarks6 and its production in association with a pair of top quarks7. Flavour tagging plays an essential role in the comprehensive research programme of ATLAS, which includes precision measurements of the Higgs boson8, top quark9 and other SM processes10, as well as the searches for supersymmetry11 and other BSM phenomena12. This work describes a flavour tagging algorithm developed by the ATLAS Collaboration for the analysis of data from pp collisions recorded during Run 2 (2015–2018) and Run 3 (2022–2026) of the LHC at centre-of-mass energies of \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) and \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\), respectively.

Flavour-tagging techniques rely on the long lifetime, high mass, high decay multiplicity and characteristic decay modes of b- and c-hadrons, and the properties of heavy-quark fragmentation13. The typical lifetime of the order of τ ≈ 1.5 ps13,14,15 for b-hadrons in jets with transverse momenta in the range from tens to hundreds of GeV results in them travelling a mean flight length 〈l〉 = βγcτ in the range from few millimetres to centimetres before decaying, which often leads to a secondary vertex significantly displaced from the collision point. Displaced vertices can also be produced by c-hadrons, which have lifetimes of τ ≈ 0.2–1.0 ps, depending on the species16,17,18, and τ-leptons, which have a lifetime of τ ≈ 0.29 ps but a much lower decay multiplicity18,19. The majority of b-jets also contain a tertiary vertex from the decay of the c-hadron produced in the b-hadron decay.

The traditional flavour-tagging algorithms developed by the ATLAS Collaboration are based on a two-stage approach4,5,20. In the first step, specialised low-level algorithms employ complementary approaches to extract information from the trajectories of the charged-particle constituents (‘tracks’) associated with the jet. These specialised algorithms either rely on the properties of individual tracks or leverage their correlations with properties of other tracks to explicitly reconstruct displaced vertices. In the second step, the outputs of low-level algorithms are subsequently combined in a high-level multivariate classifier to maximise performance. The most recent algorithm employed by the ATLAS Collaboration, following this paradigm, is a deep neural network (DL1d) that leverages a low-level track-based algorithm (DIPS)21 based on Deep Sets22. DL1d has already improved the performance by a factor of 1.3 relative to the most advanced algorithm used in published Run-2 physics analyses5.

The introduction of graph neural networks for object reconstruction in particle physics experiments23 prompted a shift in the design strategy of the ATLAS Collaboration. This led to the development of the General Network (GN) series of flavour-tagging algorithms, which directly process track and jet information and are trained using target labels extracted from Monte Carlo (MC) simulation. In parallel, the CMS Collaboration followed a similar trajectory, evolving from two-stage approaches24,25 to unified, end-to-end network architectures26,27,28.

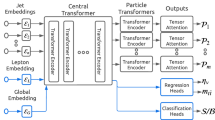

The ATLAS GN tagger uses jet flavour prediction as its primary training target and introduces auxiliary training objectives to reconstruct the internal structure of a jet by grouping tracks originating from a common vertex and by predicting the underlying physics process from which each track originated. Such physics domain knowledge is embedded in a combined loss function that enables a simultaneous optimisation, instead of relying on manually optimised low-level algorithms. This flexible structure allows the swift re-tuning of the algorithms to suit alternative experimental conditions or physics goals. A demonstrator version, GN1, achieves the above design goals using a graph-neural-network29, while the deployment version, GN2, applies a single transformer model30, illustrated in Fig. 1. Details of the algorithm architectures are summarised in the ‘Methods’ section, together with descriptions of the ATLAS detector, simulation samples, physics objects, and analysis strategies.

The jet features are copied for each track associated with the jet. The combined vectors are then fed into a per-track initialisation network, followed by a transformer encoder and a global representation of the jet. njf (ntf) corresponds to the number of jet (track) features. The pooled jet representation and output track embeddings are provided as inputs to the three task-specific networks. Details of the GN2 architecture are summarised in the ‘Methods’ section.

GN2 achieves a remarkable performance boost compared with the DL1d algorithm, with improvements by a factor of 1.5-4 observed in its major experimental applications. The deployment of GN2 should greatly enhance the physics reach of ATLAS in flagship analyses, such as the search for Higgs pair production and the c-quark Yukawa coupling measurement, for which the projected sensitivity at the High Luminosity LHC is improved by up to 30%31. These improvements do not come with a strong dependence on the choice and configuration of the MC event generator, and are confirmed by measured performance in recorded collisions. The innovative auxiliary training objectives bring excellent interpretability and opens up new avenues for future applications.

To facilitate future developments and strengthen the connections between collider experiments and the broader scientific research community, a subset of the training sample with all the required information to train GN2 can be acquired via the CERN Open Data Portal32,33.

Results

Algorithm performance in simulation

The performance of a b-tagging algorithm is evaluated based on its ability to reject c-, τ- and light-jets while maintaining a desired b-jet tagging efficiency. Similarly, the c-tagging performance is assessed by its capability to distinguish c-jets from the other jet flavours. The data samples used for training and evaluation of the model must contain jets from all flavour classes. This is achieved using jets sampled from a mixture of simulated top quark pair (\(t\overline{t}\)) and \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) events, where the latter sample considers a hypothetical heavy BSM particle, \({Z}^{{\prime} }\)34, which can decay into pairs of b-quarks, c-quarks, τ-leptons or light quarks, to populate jets in the TeV regime. The samples are simulated with MC event generators at centre-of-mass energies of both \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) and \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\). All simulated events are processed through the ATLAS detector simulation35 based on GEANT436,37,38. Further details on the simulation samples and the jet flavour labelling are discussed in the ‘Methods’ section. A mixture of samples generated at \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) and \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) is used in the training, to achieve similar performance in both conditions. In this section, the performance evaluated with Run-3 samples at \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) is presented. Jets are classified for b-tagging using a single discriminant Db, which combines the algorithm’s jet flavour prediction output probabilities of a jet being a b-jet (pb), a c-jet (pc), a τ-jet (pτ) or a light-jet (pu) and is defined as:

A jet is considered b-tagged if it has a Db score larger than a given value. A selection on Db defines an operating point (OP) associated with a certain inclusive b-jet tagging efficiency, calculated as the fraction of b-jets that are b-tagged. The mis-tagging rate for c-, τ- and light-jets is determined by the fraction of jets that are mistakenly b-tagged, for that given jet flavour, and the rejection is the reciprocal of the mis-tagging rate. The ATLAS Collaboration uses a sample of simulated \(t\bar{t}\) events, where most jets have a pT below 250 GeV, to derive the OPs. The free parameters fc(τ) determine the relative weighting between pc(τ) and pu in the discriminant Db. The specific value of fc is determined through an optimisation procedure aimed at obtaining a certain balance between rejections of c-jets and light-jets in simulated \(t\overline{t}\) events. The value of fτ is optimised to maximise the τ-jet rejection, while ensuring a negligible impact upon the c-jet and light-jet rejection. In the case of GN2, fc(τ) is set to 0.2 (0.05), while for DL1d, which does not have a τ-jet output in the model, fc is set to 0.018. For GN2, fc is tuned to reach a much higher c-jet rejection, while still achieving a better light-jet rejection, compared with DL1d.

Figure 2 illustrates the tagger performance in terms of the c-jet, light-jet and τ-jet rejection as a function of the b-jet tagging efficiency. In both the \(t\overline{t}\) and \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) samples, GN2 exhibits significantly better background rejection compared with DL1d across the entire range of b-jet tagging efficiencies. The degree of improvement depends on the b-jet tagging efficiency. In the \(t\overline{t}\) sample, the c-jet (light-jet) rejection of GN2 improves by more than a factor of 3 (1.6), compared with DL1d, for the most commonly used 70% OP. The performance of both algorithms starts degrading once the jet pT reaches around 200 GeV, due to several confounding factors, including suboptimal tracking performance in dense environments where the spatial separation between tracks becomes smaller39. In the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) sample, applying the 70% OP selection on Db yields a b-jet tagging efficiency of 30%, and the c-jet (light-jet) rejection of GN2 improves by more than a factor of 3 (4), compared with DL1d. The inclusion of a τ-jet output node in GN2 leads to an even greater enhancement in the τ-jet rejection, by up to a factor of 8 (9) for jets in the \(t\overline{t}\) (\({Z}^{{\prime} }\)) sample, without significantly degrading the c-jet and light-jet rejection.

The c-jet (solid), light-jet (dotted-dashed), and τ-jet (dashed) rejections as a function of the b-jet tagging efficiency for a jets in the \(t\bar{t}\) sample with 20 < pT < 250 GeV and b jets in the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) sample with 250 < pt < 6000 GeV, for both GN2 (light blue) and DL1d (dark orange). The performance of GN2 with respect to DL1d is shown in the bottom panels. The 68% confidence intervals calculated assuming no correlations between the rejections are indicated by the shaded regions, and the uncertainty on each rejection is obtained according to a binomial distribution.

The performance of a c-tagging algorithm is evaluated based on its ability to reject b-, τ- and light-jets while maintaining a desired c-jet tagging efficiency. Due to the end-to-end architecture that does not rely on low-level tagger inputs, GN2 can seamlessly be adapted as a c-tagging algorithm without re-training any lower level algorithms. Similar to b-tagging, a discriminant, Dc, is constructed as:

where fb(τ) is the free parameter that controls the flavour composition of the background in the background hypothesis. The value chosen for fb(τ) is 0.3 (0.01) for GN2, while for DL1d, fb is 0.1, following a similar optimisation procedure as for Db.

The c-tagging performance of DL1d and GN2 are compared in Fig. 3, which shows a significant improvement in performance across all c-jet tagging efficiencies. The b-jet (light-jet) rejection is enhanced by a factor of approximately 1.8 (2.2) in the \(t\overline{t}\) sample at a 30% c-jet tagging efficiency, which is a typical choice in measurements of the c-quark Yukawa coupling40. The b-jet (light-jet) rejection is increased by a factor of approximately 2.7 (4.7) in the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) sample at a corresponding efficiency of 10%. The τ-jet rejection is improved by a factor of approximately 15 (40) in the \(t\overline{t}\) (\({Z}^{{\prime} }\)) sample.

The b-jet (solid), light-jet (dotted-dashed), and τ-jet (dashed) rejections as a function of the c-jet tagging efficiency for a jets in the \(t\bar{t}\) sample with 20 < pT < 250 GeV and b jets in the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) sample with 250 < pt < 6000 GeV, for both GN2 (light blue) and DL1d (dark orange). The performance of GN2 relative to DL1d is shown in the bottom panels. The 68% confidence intervals calculated assuming no correlations between the rejections are indicated by the shaded regions, and the uncertainty on each rejection is obtained according to a binomial distribution.

Algorithm performance in collision data

Due to imperfections in the physics modelling of the MC generator and in the simulated detector response, the distribution of the input variables to the algorithms and their correlations differ between collision data and simulation, resulting in a performance difference. It is not practical to correct each individual mis-modelled variable, so dedicated calibration analyses are employed to measure the tagging efficiency of b-jets, c-jets and light-jets for pre-defined OPs directly4,41,42. In the case of the GN2 algorithm, five OPs are defined corresponding to inclusive b-jet tagging efficiencies of 65%, 70%, 77%, 85% and 90% while for DL1d four OPs are constructed corresponding to inclusive b-jet tagging efficiencies of 60%, 70%, 77% and 85%. The results presented in this paper are derived using pp collision data recorded during Run 2 of the LHC at \(\sqrt{s}\) = 13 TeV, corresponding to an integrated luminosity of 140 fb−1. The tagging performance in data for b-jets, c-jets, and light-jets is measured, in order to obtain jet-flavour-dependent simulation-to-data correction factors, binned in jet pT. They are applied to MC-simulated jets to rescale their tagging efficiencies and mis-tagging rates to match those measured in collision data. The calibration of b-jets and c-jets is done with \(t\bar{t}\) events4,41, while the calibration of light-jets is performed using jets produced in association with a Z boson42. Details of the calibration analyses are provided in the ‘Methods’ section.

Figure 4 presents the calibrated tagging efficiencies and rejections of GN2 and DL1d, along with their associated uncertainties, for each OP. The inclusive efficiencies and rejections are obtained by averaging over the events in a simulated \(t\overline{t}\) sample after requiring the presence of one reconstructed electron or muon. The original efficiencies from the simulated sample are included as references, enabling a direct comparison that shows similar agreement between data and simulation for both GN2 and DL1d. The GN2 tagger demonstrates clear improvements over DL1d in collision data. For instance, the measured c-jet (light-jet) rejection in data is increased by a factor of 3.5 (1.8) for the 70% OP. The measurements in data provide conclusive evidence of the enhanced performance enabled by advanced machine-learning algorithms in identifying heavy-flavour jets at the LHC.

The a light-jet rejection and b c-jet rejection as a function of the b-jet tagging efficiency for GN2 (light blue) and DL1d (dark orange), directly obtained in simulation (hollowed circle) and rescaled to match those in collision data (solid point). The horizontal error bands correspond to the uncertainties associated with the b-jet tagging efficiency measurement, while the vertical error bands indicate the uncertainties associated with the rejection measurements. A \(t\overline{t}\) MC simulation sample with a reconstructed electron or muon is used to derive these results.

Discussion

Key challenges with machine-learning algorithms based on low-level inputs, such as GN2, include the potential loss of interpretability and the need to ensure consistent performance across different MC simulation methods. Robustness against these potential shortcomings is critical to prevent the algorithm from relying on unphysical features of the training sample. In this section, these aspects are discussed further.

Physics inspiration and the auxiliary training objectives

A key strength of the GN2 model lies in its physics-inspired constraints, which aid the main task of jet classification while also improving the interpretability of the model. This is accomplished by incorporating two additional training objectives: predicting the origin of tracks associated with the jet and determining which tracks originate from common vertices. These objectives are not strictly necessary for the jet classification task and are therefore referred to as auxiliary training objectives. The technical implementation details are provided in the ‘Methods’ section.

The track classification auxiliary training objective aims to estimate the probability that a track originates from one of the following physical processes: a pile-up interaction43; the primary hard-scatter interaction; the decay of a b-hadron; the decay of a c-hadron produced by a b-hadron; the decay of a c-hadron; the decay of a τ-lepton; or any other secondary source. Class-weighted losses are applied during training to mitigate the class imbalance, and tracks are classified by the highest-probability category during evaluation. The class weights are fixed and based on the inverse class frequencies in the training dataset.

The classification efficiency refers to the probability for the track’s origin to be correctly predicted, in a group of tracks with certain target origins, while the purity corresponds to the fraction of correctly predicted tracks, within a group of tracks with specific predicted origins. When combining the two categories involving a b-hadron, GN2 achieves an efficiency (purity) of 84% (84%). For tracks that are not of heavy-flavour (HF) origin, the efficiency (purity) is 85% (96%). The above performance is evaluated in Run-3 samples at \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\).

The vertex finding auxiliary training objective aims to identify groups of tracks that originate from a common spatial point. Each pair of tracks in the jet is classified to determine whether they share the same vertex. Using these pair-wise compatibility scores, track groups (vertices) are formed via a union-find algorithm44. SV1, an existing secondary vertex reconstruction algorithm detailed in ref. 5, serves as a reference algorithm. SV1 reconstructs a single inclusive vertex, whereas GN2 can identify multiple vertices of various types within a jet. Therefore, an aggregation procedure is applied to the output of GN2 to enable a direct comparison with the single inclusive vertex produced by SV1. To study the vertex properties of b-jets, the identified vertex containing the most tracks that have a predicted primary origin is removed, as this is likely to be the vertex associated with the primary hard-scatter interaction. Next, the remaining GN2 vertices that include at least one track predicted to have a HF origin are consolidated into a single inclusive vertex.

An inclusive reference vertex is constructed in simulated events, by combining all tracks from simulation-level secondary vertices within the jet that consist solely of HF tracks. A Billoir fit45 is performed on the tracks selected by the GN2 and SV1 vertex finding algorithms to obtain the transverse displacement of the vertex, Lxy. Figure 5 presents the Lxy distribution for vertices obtained with GN2 and DL1d in b-jets from a simulated \(t\overline{t}\) sample, compared to the expected distribution derived from the inclusive reference vertex. GN2 consistently achieves higher vertex-finding efficiency than SV1 across the entire distribution of Lxy. The mass of the secondary vertex can also be calculated using the momenta of tracks selected by the vertex finding algorithms. The distribution of the secondary vertex mass normalised to unity is also shown in Fig. 5. Remarkably, the mass of the secondary vertices reconstructed by GN2 exhibits good agreement with the mass of the inclusive reference vertex, despite the vertex mass not being explicitly targeted during training. Unlike SV1, GN2 does not impose explicit selections on track properties such as impact parameters. This leads to a higher efficiency, albeit with a small contamination from non-HF tracks, which results in a slightly larger secondary vertex mass.

The a transverse displacement and the b mass of the secondary vertex obtained by the GN2 (solid) and the SV1 (dotted) algorithms. While the transverse displacement is calculated via a Billoir fit performed on the tracks assigned to the vertex by the respective algorithm, the vertex mass is defined as the invariant mass of the same set of assigned tracks. MC truth (dashed) corresponds to an inclusive reference vertex derived from all tracks associated to simulation-level vertices containing only b-hadron tracks. The last bin in each plot includes overflow.

GN2 identifies all types of vertices including those from material interactions, photon conversions, and in-flight decays of light hadrons. Consequently, the rate of vertices reconstructed in light-jets, defined as the fraction of light-jets containing a GN2 inclusive vertex, is expected to be much higher compared to SV1 if no selections are applied in the aggregation procedure described above. Figure 6 confirms this with light-jets in the simulated \(t\overline{t}\) sample and shows that once requiring the GN2 inclusive vertex to contain at least one track with predicted HF origin, the vertexing rate is dramatically reduced, down to the same level as SV1.

To test the impact of the auxiliary objectives on the performance of the main jet classification task, various GN2 configurations are trained and tested. The resulting c-jet and light-jet rejections are reduced by up to 30% in both the \(t\overline{t}\) and \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) samples, if both auxiliary objectives are disabled. Disabling only one of them is sufficient to recover most of the performance loss, indicating that the two tasks are highly correlated in their contributions to the main jet flavour tagging objective.

Although the outputs from the auxiliary tasks described above mainly serve as a way to improve HF jet identification, with future development, their direct usage in physics analyses remains a promising possibility.

Robustness against generator modelling variations

Flavour-tagging algorithms are sensitive to the modelling of parton showering, hadronisation, the underlying event and the properties of heavy-hadron decays46. To evaluate the robustness of the algorithm against modelling variations, a comparative study of the GN2 performance in the nominal simulated \(t\overline{t}\) sample used during training and samples produced with alternative generator settings, both with Run-2 conditions at \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\), is performed.

The event and showering generators adopted for the nominal sample are Powhegbox47,48,49,50 and Pythia51, respectively. The alternative samples include the use of a different showering generator (Herwig52,53,54), whilst keeping the same event generator, and the use of Sherpa55, which applies a different approach to all parts of the event generation model. The ratio between the efficiency obtained with an alternative generator setup and with the nominal setup is used to quantify the generator dependence of the algorithms.

Table 1 shows these ratios for b-jets, c-jets, and light-jets at the 70% and 85% OPs. Across the tested generators, the GN2 performance for b-jets agrees to within 1–2%, for c-jets the agreement is within 10%, and for light-jets the agreement is within 4%. Similar agreement is also observed for other OPs. The level of relative disagreement between DL1d and GN2 is close to unity, suggesting that despite the GN2 model being significantly more complex, it does not induce additional generator dependence.

Methods

The ATLAS detector

The ATLAS experiment2,3 at the LHC is a multipurpose particle detector with a forward-backward symmetric cylindrical geometry and a solid-angle coverage of almost 4π. It is used to record particles produced in pp collisions at the LHC through a combination of particle position and energy measurements. It includes an inner-tracking detector (ID) surrounded by a thin superconducting solenoid providing a 2 T axial magnetic field, electromagnetic and hadronic calorimeters, and a muon spectrometer. The ID consists of silicon pixel, silicon microstrip, and transition radiation tracking detectors. The muon spectrometer surrounds the calorimeters and is based on three large superconducting air-core toroidal magnets with eight coils each providing a field integral of between 2 T m and 6 T m across the detector.

An extensive software suite56 is used in data simulation, the reconstruction and analysis of real and simulated data, detector operations, and the trigger and data acquisition systems of the experiment.

Monte Carlo simulation samples

The \(t\overline{t}\) events at \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) are modelled using the Powhegbox[v2]47,48,49,50 event generator at next-to-leading-order (NLO) in the strong coupling constant αs with the NNPDF3.0 NLO57 parton distribution function (PDF) set and the first-gluon-emission cut-off scale parameter hdamp set to 1.5mt, with a top-quark mass of mt = 172.5 GeV. Parton shower, hadronisation, and the underlying event are modelled by interfacing Powhegbox[v2] to Pythia 8.23051, using the A14 set of tuned parameters58 and the NNPDF2.3LO PDF set59. The decays of b- and c-hadrons are performed by Evtgen 1.6.060.

The \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) events at \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) used to enrich the dataset with high-pT jets are generated using Pythia 8.243 with the A14 set of tuned parameters for the underlying event and the leading-order (LO) Nnpdf 2.3LO PDF set. A broad jet pT spectrum with an almost uniform distribution between 250 GeV and 1.5 TeV and a tail expanding to 6 TeV is obtained by applying a weighting factor that modifies the original cross-section of the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) resonance. The decays to \(b\bar{b}\), \(c\bar{c}\), and light-flavour quark pairs are set to have equal branching ratios, while the branching ratio to \(\tau \bar{\tau }\) is set to 5%. The decays of b- and c-hadrons are performed by Evtgen 1.7.0.

The \(t\overline{t}\) and \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) events at \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) are produced using the same setups, but with newer versions of Pythia (8.308) and Evtgen (2.1.1).

The impact of using different generators and models for parton shower and hadronisation is studied with simulated \(t\overline{t}\) events from alternative generator setups. Two scenarios are considered, where either only the showering algorithm is varied, or the entire chain is changed. The former is achieved by interfacing the Powhegbox[v2] generator with the Herwig[7.2.1]52,53,54 showering algorithm using the Herwig[7.1] default set of tuned parameters, with the Nnpdf 3.0 NLO set of PDFs. The latter is realised with the Sherpa[2.2.12]55 generator, using NLO-accurate matrix elements for up to one additional parton, and LO-accurate matrix elements for up to four additional partons, calculated with the COMIX61 and Openloops62,63,64 libraries. The Sherpa parton shower65,66 is applied using the Meps@nlo prescription67,68,69,70 and the set of tuned parameters developed by the Sherpa authors to match the Nnpdf 3.0 NNLO set of PDFs.

Objects for flavour tagging

ATLAS uses a right-handed coordinate system with its origin at the nominal interaction point in the centre of the detector and the z-axis along the beam pipe. The x-axis points from the nominal interaction point to the centre of the LHC ring, and the y-axis points upwards. Cylindrical coordinates (r, ϕ) are used in the transverse plane, ϕ being the azimuthal angle around the z-axis. The pseudorapidity is defined in terms of the polar angle θ as \(\eta=-\ln \tan (\theta /2)\). Angular distance is measured in units of \(\Delta R\equiv \sqrt{{(\Delta \eta)}^{2}+{(\Delta \phi)}^{2}}\).

The fundamental objects for flavour tagging are jets, tracks, and vertices. A concise description of these objects is provided below, while a detailed description is available in ref. 5.

Tracks are reconstructed from ID information39,71. To be considered for jet flavour tagging they are required to be within ∣η∣ < 2.5, have pT > 0.5 GeV and satisfy criteria designed to reject fake and poorly measured tracks72.

Primary vertices (PVs) are reconstructed from tracks in the luminous region of the colliding LHC beams using an adaptive multi-vertex filter73,74. The PV with the highest sum of squared transverse momenta pT of contributing tracks is selected as the primary interaction point (IP) and provides the reference point in an event. The distance of closest approach of a track to the IP, the ‘perigee’, is indicated in the transverse plane by the transverse impact parameter d0. The longitudinal separation between the IP and the point on the track where d0 is measured, is indicated by the longitudinal impact parameter z0. Tracks with large impact parameters can indicate the presence of displaced decays, providing vital information to the flavour tagging algorithms.

The DIPS and GN2 algorithms require tracks to be reconstructed from at least 8 hits in the silicon detector, at most one of which contributes to two tracks, at most two ‘holes’ in the silicon detector, and at most one hole in the pixel detector, where hole denotes a hit missing where one is expected from the track trajectory. Further, requirements on the track impact parameters, ∣d0∣ < 3.5 mm and \(| {z}_{0}\sin \theta | < 5\,{{\rm{mm}}}\), retain charged particle tracks originating from HF hadron decays while suppressing tracks from other sources.

Jets are reconstructed using the anti-kt algorithm75 with radius parameter R = 0.4 using the ‘fastjet’ package76. The input constituents are ‘particle-flow’ objects77 which combine signals in the ATLAS calorimeters and ID to exploit precision tracking information for low-pT charged hadrons spatially matched with calorimeter energy deposits. The jet pT is corrected to the corresponding particle-level jet pT using calibration techniques described in ref. 78. The jets are required to have pT > 20 GeV (to be within the valid calibration range) and ∣η∣ < 2.5 (to be within the tracking fiducial volume set by the ID acceptance) to be considered for flavour tagging. Additionally, jets from pile-up interactions are suppressed by the ‘jet vertex tagger’ (JVT) algorithm79, which uses the ID tracks associated with the jet to form a multivariate discriminant. The JVT efficiency for jets originating from the IP is 92% in the simulation. The jet axis, derived from the sum of the momenta of the jet constituents, is used when associating tracks with the jet and when assigning a lifetime sign to the tracks’ impact parameters. Tracks are associated with a given jet by setting a maximum allowed angular separation ΔR between the track momenta, defined at the perigee, and the jet axis. The ΔR requirement varies as a function of the jet pT to account for decay products from b-hadrons with larger pT being more collimated, ranging from 0.45 for jet pT = 20 GeV to 0.26 for jet pT > 150 GeV. If a track can be associated with multiple jets, it is assigned to the jet closest in ΔR. The sign convention for the lifetime-signed impact parameters assigns a positive sign if the track intersects the jet axis in the transverse plane in front of the IP, and a negative sign if the intersection lies behind the IP20. The flavour labels of jets in simulation are assigned depending on the hadrons associated with the jet. The set of weakly decaying hadrons and hadronically decaying τ-leptons with pT > 5 GeV within a ΔR < 0.3 cone around the jet axis determines the jet flavour following a sequential labelling decision tree. A jet is labelled a b-jet if it contains at least one b-hadron with pT > 5 GeV, a c-jet (τ-jet) if it contains at least one c-hadron (hadronic τ-lepton decay) and no b-hadron, and otherwise it is called a light-jet, where the latter is an inclusive label for the jets originating from a light quark or gluon. These labels are used both for training the algorithms, and for evaluating their performance.

Targets for the auxiliary training objectives are obtained from the simulation-level event record. Tracks are matched with simulation-level particles using the approach in ref. 39. Track-origin labels are obtained by analysing the decay history of the matched particles, while track-pair-compatibility labels are obtained by considering the production vertices of the matched particles. Production vertices within 0.1 mm in 3D space are merged to account for the finite resolution of the detector, and the matched track-pairs are assigned the same label.

The algorithm architecture

The primary flavour tagging algorithm presented is GN2, which directly learns from the charged particle tracks via a transformer-based model. Another algorithm, DL1d, which follows previous approaches of combining inputs from several low-level taggers in a multivariate technique, is also discussed as a baseline reference.

Both algorithms are trained on a dataset created from combining the simulated \(t\overline{t}\) and \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) samples described earlier in this section. Jets with 20 GeV < pT < 250 GeV are taken from the \(t\overline{t}\) sample and those with 250 GeV < pT < 6 TeV from the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) sample. The b-jets, light-jets and τ-jets are re-sampled in pT and η to match the corresponding c-jet distributions, thereby preventing the models from discriminating between jet flavours based on relative kinematic differences. All input variables to the algorithm training are normalised to have zero mean and unit variance. A coarse optimisation of hyperparameters, such as the number of layers, is carried out for both algorithms, and the AdamW80 (Adam81) optimiser is used for training GN2 (DL1d) with the learning rate and optimisation schedule defined below.

The GN2 algorithm is an end-to-end architecture without any intermediate taggers involved, as illustrated in Fig. 1. It is based on the GN129 demonstrator version of the algorithm, replacing the Graph Attention Network82 with a Transformer30 along with other architecture optimisations. GN2 directly accepts information about the jet and associated tracks that are provided by the standard event reconstruction. This results in a simpler and more flexible algorithm which can be easily reoptimised for different physics objectives, such as the identification of highly energetic Higgs bosons decaying into b- or c-quark pairs83, jet energy regression84, exotic jet tagging85, and jet flavour tagging in the ATLAS high-level trigger86. Additionally, when compared with DL1d, GN2 is trained to recognise an additional class of jets that originate from hadronic τ-lepton decays.

First, the jet features are concatenated with a fixed-size array of 40 track feature vectors, with unused elements masked when fewer than 40 tracks are available, allowing it to handle variable track multiplicity without zero-padding. Tracks with smaller absolute track impact parameter significance5 are dropped if there are more than 40 tracks. The same inputs as for GN129 are used, except the variables related to holes in the silicon tracker, which were found to have no impact on performance. A complementary interpretability analysis using integrated gradients shows that the impact parameter significances and angular variables emerge as particularly influential87. The combined vectors are then fed into a per-track initialisation network, which is composed of a single hidden layer and an output layer of size 256. Next, a four layer transformer encoder with eight attention heads is used to produce track representations that incorporate information from other tracks inside the jet. The transformer has an embedding size of 256 and a feed-forward dimension of 512, and uses pre-LayerNorm88. After the transformer encoder, the output track representations are projected down to dimension 128, and a global representation of the jet is produced using attention pooling89. The pooled jet representation and output track embeddings are provided as inputs to the three task-specific networks. The primary objective, jet classification, uses only the pooled jet representation and has an output layer of size 4, providing pb, pc, pu and pτ for the final discriminant definition. The two auxiliary objectives introduced in the Discussion section take advantage of the track embeddings, in addition to the global jet representation. The track origin classification task uses individual track embeddings and has 7 output categories, while the track-pair compatibility task employs a binary output layer, using the embeddings of each pair of tracks. Each task-specific network consists of three hidden layers with size 128, 64 and 32, respectively. ReLU activation90 is used throughout the model. Cross-entropy loss is used by all three task-specific networks, which is combined with tunable weights to form the final loss function, enabling a simultaneous optimisation of the entire algorithm. GN2 applies the same auxiliary network structures and loss weights as GN129.

GN2 is trained using a 4-fold strategy to prevent memorisation of the training samples, given their possible use in ATLAS physics analyses. Jets are assigned to one of the four folds pseudo-randomly, with a number seeded by the event number and discrete jet properties. Four classifiers are then trained, each excluding one of the four folds from the training dataset. In physics analysis, each jet is tagged using the classifier it was excluded from during training. Each of the four networks has approximately 2.3M trainable parameters and is trained using approximately 45M (18M) b-jets, 45M (18M) c-jets, 90M (36M) light-jets and 6.25M (2.5M) τ-jets from the \(t\overline{t}\) (\({Z}^{{\prime} }\)) sample, simulated at both \(\sqrt{s}=13\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\) and \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\,{{\rm{TeV}}}\), with a mixing ratio of 2:1. A learning rate scheduler with cosine annealing91 is used with the initial learning rate set to 1 × 10−7, which is increased to 5 × 10−4 after the first 1% of training steps have been completed. It reduces to 1 × 10−5 over the remainder of the training run. A weight decay of 1 × 10−5 is also added. A batch size of 12,000 is adopted. The different folds have compatible performance within statistical uncertainty. The training data is translated from a standard ATLAS format56 to HDF592. The network is trained with PYTORCH LIGHTNING93,94,95, consuming roughly 300 GPU hours on an NVIDIA A100 card. It is deployed in ATLAS software with ONNXRUNTIME96, adding negligible CPU time. With the updated architecture and training setup, the c-jet (light-jet) rejection is improved by a factor of 1.5 (1.7) for a 70% b-jet tagging efficiency, in the \(t\overline{t}\) sample, and by a factor of 1.3 (1.4) for the corresponding 30% b-jet tagging efficiency, in the \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) sample.

The DL1d algorithm inherits the architecture from its predecessor DL1r, described in Ref. 5, but processes track impact parameters with the DIPS algorithm based on DeepSets21,22 instead of a recurrent neural network97. Overall, 44 input features are fed into DL1d, including the jet pT and η. The architecture of DL1d includes eight hidden layers of size 256, 128, 60, 48, 36, 24, 12, and 6, each followed with ReLU activation and batch normalisation. The training was performed with a learning rate of 1 × 10−3 and training batch size of 15,000. The training data pipeline is similar to GN2, with the exception that training is done with KERAS and TENSORFLOW98 via UMAMI, a dedicated Python toolkit99, and deployed in the ATLAS software with LWTNN100.

Performance measurement strategies in collision data

The measurement of the b-jet tagging efficiency in collision data is carried out in a roughly 90% pure sample of \(t\bar{t}\) events where both top quarks decay leptonically into a lepton, a neutrino and a b-quark. The events are required to contain exactly one electron and one muon of opposite charge, in addition to two jets. The invariant masses of the two lepton-jet pairs are used to define one region enriched in b-jets and three control regions (CRs). The b-jet-enriched region is determined by requiring that both lepton-jet pairs have invariant masses compatible with an on-shell top quark decay. The CRs are used in a likelihood fit to constrain the predicted jet flavour composition. They are constructed to have increased fractions of non-b-jets by requiring that at least one or both of the lepton-jet pairs do not originate from the same top-quark decay. The analysis employs a statistical model based on a likelihood function that extracts the efficiency in collision data binned in pT for all the b-jets in the sample. The dominant systematic uncertainty comes from the modelling of \(t\bar{t}\) events. Additional details on the b-jet calibration procedure are available in ref. 4.

The calibration measurement of the c-jet mis-tagging rate is performed in \(t\bar{t}\) events where one top quark decays leptonically while the other top quark decays hadronically. A sample of c-jets is obtained through the \({W}^{\pm }\to c\bar{s}(\bar{c}s)\) decay from the hadronically decaying top quark. A likelihood-based kinematic reconstruction is employed to find, among the four jets in the event, two jets associated with the hadronically decaying W-boson and two jets stemming from the b-quarks produced in the top quark decays. The mis-tagging rate of c-jets is determined by minimising a χ2 function computed in bins of the jet pT of the two jets from the W-boson decay. Additional terms that correct for the potential mis-modelling of the total number of events in each jet pT bin are estimated simultaneously from the fit to collision data, while the contribution of background events, in which no c-jets are associated with the W-boson decay, is estimated from simulations. The mis-tagging rate of light-jets in this sample is corrected using the method described below. As with the b-jets calibration analysis, the leading source of systematic uncertainties is the modelling of \(t\bar{t}\) events. The c-jet mis-tagging rate calibration procedure is detailed in ref. 41.

The mis-tagging rate for light-jets is determined using jets produced in association with a Z boson, where the Z boson decays into muon or electron pairs. The key challenge in this calibration is to develop a method capable of extracting a light-jet mis-tagging rate in data despite the high rejection of the taggers. The method used in this work involves exploiting transformed track variables in alternate taggers that provide reduced b(c)-jet tagging efficiency and almost unchanged light-jet rejection. The mis-tagging rate of this modified tagger is measured from a fit to the flavour-sensitive secondary vertex mass distribution in collision data, and dedicated uncertainties are introduced so that it can be extrapolated to that of the nominal tagger. These extrapolation uncertainties are a leading source of systematic uncertainty. A detailed description of the procedure is provided in ref. 42.

Code availability

The ATLAS data reduction software is available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4772550)102. The GN2 training software suite can be found at JOSS (https://joss.theoj.org/papers/10.21105/joss.07217)95, and the DL1d training software stack is available at JOSS (https://joss.theoj.org/papers/10.21105/joss.05833)99.

References

Evans, L. & Bryant, P. LHC machine. J. Instrum. 3, S08001 (2008).

ATLAS Collaboration. The ATLAS experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. J. Instrum. 3, S08003 (2008).

ATLAS Collaboration. The ATLAS experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider: a description of the detector configuration for Run 3. J. Instrum. 19, P05063 (2024).

ATLAS Collaboration. ATLAS b-jet identification performance and efficiency measurement with \(t\bar{t}\) events in pp collisions at \(t\bar{t}\). Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 970 (2019).

ATLAS Collaboration. ATLAS flavour-tagging algorithms for the LHC Run 2 pp collision dataset. Eur. Phys. J. C 83, 681 (2023).

ATLAS collaboration. Observation of \(H\to b\bar{b}\) decays and VH production with the ATLAS detector. Phys. Lett. B 786, 59 (2018).

ATLAS collaboration. Observation of Higgs boson production in association with a top quark pair at the LHC with the ATLAS detector. Phys. Lett. B 784, 173 (2018).

ATLAS collaboration. Characterising the Higgs boson with ATLAS data from the LHC Run-2. Phys. Rep. 1116, 4 (2025).

ATLAS collaboration. Climbing to the top of the ATLAS 13 TeV data. Phys. Rep. 1116, 127 (2025).

ATLAS collaboration. Electroweak, QCD and flavour physics studies with ATLAS data from Run 2 of the LHC. Phys. Rep. 1116, 57 (2025).

ATLAS collaboration. The quest to discover supersymmetry at the ATLAS experiment. Phys. Rep. 1116, 261 (2025).

ATLAS collaboration. Exploration at the high-energy frontier: ATLAS Run 2 searches investigating the exotic jungle beyond the Standard Model. Phys. Rep. 1116, 301 (2025).

HFLAV collaboration. Averages of b-hadron, c-hadron, and τ-lepton properties as of 2021. Phys. Rev. D 107, 052008 (2023).

BABAR collaboration. Measurement of the B0 and B+ meson lifetimes with fully reconstructed hadronic final states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 201803 (2001).

ATLAS collaboration. Precision measurement of the B0 meson lifetime using B0 → J/ψK*0 decays with the ATLAS detector. Eur. Phys. J. C 85, 736 (2025).

Belle-II collaboration. Precise measurement of the D0 and D+ lifetimes at Belle II. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 211801 (2021).

Belle-II Collaboration. Measurement of the Λc+ Lifetime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 071802 (2023).

Particle Data Group collaboration. Review of particle physics PTEP 083C01 (2020).

Belle Collaboration. Measurement of the τ-lepton lifetime at Belle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 031801 (2014).

ATLAS collaboration. Performance of b-jet identification in the ATLAS Experiment. J. Instrum. 11, P04008 (2016).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Deep Sets based Neural Networks for Impact Parameter Flavour Tagging in ATLAS.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2020-014 (2020).

Komiske, P. T., Metodiev, E. M. & Thaler, J. Energy flow networks: deep sets for particle jets. J. High Energy Phys. 1, 121 (2019).

Shlomi, J., Battaglia, P. & Vlimant, J.-R. Graph neural networks in particle physics. 7, https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-2153/abbf9a (2020).

CMS Collaboration. Identification of heavy-flavour jets with the CMS detector in pp collisions at 13 TeV. J. Instrum. 13, P05011 (2018).

Bols, E., Kieseler, J., Verzetti, M., Stoye, M. & Stakia, A. Jet flavour classification using DeepJet. J. Instrum. 15, P12012 (2020).

Qu, H. & Gouskos, L. ParticleNet: jet tagging via particle clouds. Phys. Rev. D 101, 056019 (2020).

CMS Collaboration. “A unified approach for jet tagging in Run 3 at \(\sqrt{s}=13.6 \,\, {\mbox{TeV}}\) in CMS.” CMS DP 2024 066, (2024).

CMS Collaboration. “Performance of heavy-flavour jet identification in boosted topologies in proton-proton collisions at \(\sqrt{s}=13 \,\, {\mbox{TeV}}\).” CMS-PAS-BTV-22-001 (2023).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Graph Neural Network Jet Flavour Tagging with the ATLAS Detector.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2022-027 (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention Is All You Need. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762 (2017).

ATLAS and CMS Collaborations, “Highlights of the HL-LHC physics projections by ATLAS and CMS.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2025-018 CMS-HIG-25-002, 4 (2025).

ATLAS Collaboration, ATLAS t\(\overline{t}\) simulation for ML-based jet flavour tagging (JetSet), CERN Open Data Portal (2025).

The JetSet Developers. “Transforming Jet Flavor.”

Langacker, P. The Physics of Heavy \({Z}^{{\prime} }\) Gauge Bosons. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1199 (2009).

ATLAS Collaboration. The ATLAS Simulation Infrastructure. Eur. Phys. J. C 70, 823 (2010).

Agostinelli, S. et al. GEANT4 – a simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250 (2003).

Allison, J. et al. Geant4 developments and applications. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 53, 270 (2006).

Allison, J. et al. Recent developments in Geant4. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 835, 186 (2016).

ATLAS collaboration. Performance of the ATLAS track reconstruction algorithms in dense environments in LHC Run 2. Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 673 (2017).

ATLAS Collaboration. Measurements of WH and ZH production with Higgs boson decays into bottom quarks and direct constraints on the charm Yukawa coupling in 13 TeV pp collisions with the ATLAS detector. J. High Energy Phys. 4, 75 (2025).

ATLAS Collaboration. Measurement of the c-jet mistagging efficiency in \(t\bar{t}\) events using pp collision data at \(t\bar{t}\) collected with the ATLAS detector. Eur. Phys. J. C 82, 95 (2022).

ATLAS Collaboration. Calibration of the light-flavour jet mistagging efficiency of the b-tagging algorithms with Z+jets events using 139 fb−1 of ATLAS proton–proton collision data at \(\sqrt{s}=13 \,\, {\mbox{TeV}}\). Eur. Phys. J. C 83, 728 (2023).

Soyez, G. Pileup mitigation at the LHC: a theorist’s view. Phys. Rep. 803, 1 (2019).

Kozen, D.C. Union-find. in The Design and Analysis of Algorithms 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4400-4_10 (Springer New York, 1992).

Billoir, P. & Qian, S. Fast vertex fitting with a local parametrization of tracks. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 311, 139 (1992).

Buckley, A. et al. General-purpose event generators for LHC physics. Phys. Rep. 504, 145 (2011).

Frixione, S., Ridolfi, G. & Nason, P. A positive-weight next-to-leading-order Monte Carlo for heavy flavour hadroproduction. J. High Energy Phys. 9, 126 (2007).

Nason, P. A new method for combining NLO QCD with shower Monte Carlo algorithms. J. High Energy Phys. 11, 40 (2004).

Frixione, S., Nason, P. & Oleari, C. Matching NLO QCD computations with parton shower simulations: the POWHEG method. J. High Energy Phys. 11, 70 (2007).

Alioli, S., Nason, P., Oleari, C. & Re, E. A general framework for implementing NLO calculations in shower Monte Carlo programs: the POWHEG BOX. J. High Energy Phys. 6, 43 (2010).

Sjöstrand, T. et al. An introduction to PYTHIA 8.2. Comput. Phys. Commun. 191, 159 (2015).

Bähr, M. et al. Herwig++ physics and manual. Eur. Phys. J. C 58, 639 (2008).

Bellm, J. et al. Herwig 7.0/Herwig++ 3.0 release note. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 196 (2016).

Bellm, J. et al. Herwig 7.2 release note. Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 452 (2020).

Bothmann, E. et al. Event generation with Sherpa 2.2. SciPost Phys. 7, 034 (2019).

ATLAS Collaboration. Software and computing for Run 3 of the ATLAS experiment at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 85, 234 (2025).

NNPDF Collaboration. Parton distributions for the LHC run II. J. High Energy Phys. 4, 040 (2015).

ATLAS Collaboration. “ATLAS Pythia 8 tunes to 7TeV data.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2014-021 (2014).

NNPDF Collaboration. Parton distributions with LHC data. Nucl. Phys. B 867, 244 (2013).

Lange, D. J. The EvtGen particle decay simulation package. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 462, 152 (2001).

Gleisberg, T. & Höche, S. Comix, a new matrix element generator. J. High Energy Phys. 12, 039 (2008).

Buccioni, F. et al. OpenLoops 2. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 866 (2019).

Cascioli, F., Maierhöfer, P. & Pozzorini, S. Scattering amplitudes with open loops. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 111601 (2012).

Denner, A., Dittmaier, S. & Hofer, L. COLLIER: A FORTRAN-based complex one-loop library in extended regularizations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 212, 220 (2017).

Gleisberg, T. et al. Event generation with SHERPA 1.1. J. High Energy Phys. 2, 7 (2009).

Schumann, S. & Krauss, F. A parton shower algorithm based on Catani–Seymour dipole factorisation. J. High Energy Phys. 3, 38 (2008).

Höche, S., Krauss, F., Schönherr, M. & Siegert, F. A critical appraisal of NLO+PS matching methods. J. High Energy Phys. 9, 49 (2012).

Höche, S., Krauss, F., Schönherr, M. & Siegert, F. QCD matrix elements + parton showers. The NLO case. J. High Energy Phys. 4, 27 (2013).

Catani, S., Krauss, F., Webber, B. R. & Kuhn, R. QCD Matrix Elements + Parton Showers. J. High Energy Phys. 11, 63 (2001).

Höche, S., Krauss, F., Schumann, S. & Siegert, F. QCD matrix elements and truncated showers. J. High Energy Phys. 5, 53 (2009).

ATLAS Collaboration. Software performance of the ATLAS track reconstruction for LHC Run 3. Comput. Softw. Big Sci. 8, 9 (2024).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Performance of ATLAS Pixel Detector and Track Reconstruction at the start of Run 3 in LHC Collisions at \(\sqrt{s}=900 \,\, {\mbox{GeV}}\).” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2022-033 (2022).

ATLAS Collaboration. Reconstruction of primary vertices at the ATLAS experiment in Run 1 proton–proton collisions at the LHC. Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 332 (2017).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Vertex Reconstruction Performance of the ATLAS Detector at \(\sqrt{s}=13 \,\, {\mbox{TeV}}\).” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2015-026 (2015).

Cacciari, M., Salam, G. P. & Soyez, G. The anti-kt jet clustering algorithm. J. High Energy Phys. 04, 063 (2008).

Cacciari, M., Salam, G. P. & Soyez, G. FastJet user manual. Eur. Phys. J. C 72, 1896 (2012).

ATLAS Collaboration. Jet reconstruction and performance using particle flow with the ATLAS Detector. Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 466 (2017).

ATLAS Collaboration. Jet energy scale and resolution measured in proton–proton collisions at \(\sqrt{s}=13 \,\, {\mbox{TeV}}\) with the ATLAS detector. Eur. Phys. J. C 81, 689 (2021).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Tagging and suppression of pileup jets with the ATLAS detector.” ATLAS-CONF-2014-018 (2014).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Fixing weight decay regularization in Adam. Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. (ICLR 2018).

Kingma, D.P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980 (2017).

Brody, S., Alon, U. & Yahav, E. How attentive are graph attention networks? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2105.14491 (2021).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Transformer Neural Networks for Identifying Boosted Higgs Bosons decaying into \(b\bar{b}\) and \(c\bar{c}\) in ATLAS.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2023-021 (2023).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Transformer networks for constituent-based b-jet calibration with the ATLAS detector.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2025-012 (2024).

ATLAS Collaboration. Search for emerging jets in pp collisions at \(\sqrt{s}=13.6\) TeV with the ATLAS experiment. Rep. Prog. Phys. 88, 097801 (2025).

ATLAS Collaboration. Configuration, performance, and commissioning of the ATLAS b-jet triggers for the 2022 and 2023 LHC data-taking periods. J. Instrum. 20, P03002 (2025).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Explaining the ATLAS GN2 flavour tagging algorithm with integrated gradients.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2025-029 (2025).

Xiong, R. et al. On layer normalization in the transformer architecture. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2002.04745 (2020).

Li, Y., Tarlow, D., Brockschmidt, M. & Zemel, R. Gated graph sequence neural networks. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1511.05493 (2015).

Fukushima, K. Cognitron: a self-organizing multilayered neural network. Biol. Cybern. 20, 121 (1975).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. SGDR: stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1608.03983 (2016).

The HDF Group. “Hierarchical Data Format, version 5”. https://github.com/HDFGroup/hdf5

Ansel, J. et al. Pytorch 2: faster machine learning through dynamic Python bytecode transformation and graph compilation. In Proc. 29th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 2 (ASPLOS ’24) https://doi.org/10.1145/3620665.3640366 (ACM, 2024).

William, F. et al. PyTorch Lightning. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3828935 (2019).

Barr, J. et al. Salt: multimodal multitask machine learning for high energy physics. J. Open Source Softw. 10, 7217 (2025).

ONNX Runtime developers. “Onnx runtime.” https://onnxruntime.ai/ (2021).

ATLAS Collaboration. “Identification of Jets Containing b-Hadrons with Recurrent Neural Networks at the ATLAS Experiment.” ATL-PHYS-PUB-2017-003 (2017).

TensorFlow Developers. Tensorflow. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4724125 (2022).

Barr, J. et al. Umami: a Python toolkit for jet flavour tagging. J. Open Source Softw. 9, 5833 (2024).

Guest, D.H. et al. lwtnn/lwtnn: v2.14.1. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14276439 (2024).

ATLAS Collaboration. “ATLAS Computing Acknowledgments.” ATL-SOFT-PUB-2025-001 (2025).

ATLAS Collaboration. Athena. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4772550 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CERN for the very successful operation of the LHC and its injectors, as well as the support staff at CERN and at their institutions worldwide without whom ATLAS could not be operated efficiently. The crucial computing support from all WLCG partners is acknowledged gratefully, in particular from CERN, the ATLAS Tier-1 facilities at TRIUMF/SFU (Canada), NDGF (Denmark, Norway, Sweden), CC-IN2P3 (France), KIT/GridKA (Germany), INFN-CNAF (Italy), NL-T1 (Netherlands), PIC (Spain), RAL (UK) and BNL (USA), the Tier-2 facilities worldwide and large non-WLCG resource providers. Major contributors of computing resources are listed in ref. 101. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of ANPCyT, Argentina; YerPhI, Armenia; ARC, Australia; BMWFW and FWF, Austria; ANAS, Azerbaijan; CNPq and FAPESP, Brazil; NSERC, NRC and CFI, Canada; CERN; ANID, Chile; CAS, MOST and NSFC, China; Minciencias, Colombia; MEYS CR, Czech Republic; DNRF and DNSRC, Denmark; IN2P3-CNRS and CEA-DRF/IRFU, France; SRNSFG, Georgia; BMFTR, HGF and MPG, Germany; GSRI, Greece; RGC and Hong Kong SAR, China; ICHEP and Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Israel; INFN, Italy; MEXT and JSPS, Japan; CNRST, Morocco; NWO, Netherlands; RCN, Norway; MNiSW, Poland; FCT, Portugal; MNE/IFA, Romania; MSTDI, Serbia; MSSR, Slovakia; ARIS and MVZI, Slovenia; DSI/NRF, South Africa; MICIU/AEI, Spain; SRC and Wallenberg Foundation, Sweden; SERI, SNSF and Cantons of Bern and Geneva, Switzerland; NSTC, Taipei; TENMAK, Türkiye; STFC/UKRI, United Kingdom; DOE and NSF, United States of America. Individual groups and members have received support from BCKDF, CANARIE, CRC and DRAC, Canada; CERN-CZ, FORTE and PRIMUS, Czech Republic; COST, ERC, ERDF, Horizon 2020, ICSC-NextGenerationEU and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, European Union; Investissements d’Avenir Labex, Investissements d’Avenir Idex and ANR, France; DFG and AvH Foundation, Germany; Herakleitos, Thales and Aristeia programmes co-financed by EU-ESF and the Greek NSRF, Greece; BSF-NSF and MINERVA, Israel; NCN and NAWA, Poland; La Caixa Banking Foundation, CERCA Programme Generalitat de Catalunya and PROMETEO and GenT Programmes Generalitat Valenciana, Spain; Göran Gustafssons Stiftelse, Sweden; The Royal Society and Leverhulme Trust, United Kingdom. In addition, individual members wish to acknowledge support from Armenia: Yerevan Physics Institute (FAPERJ); CERN: European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN DOCT); Chile: Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (FONDECYT 1230812, FONDECYT 1240864); China: Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST-2023YFA1605700, MOST-2023YFA1609300), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC - 12175119, NSFC 12275265); Czech Republic: Czech Science Foundation (GACR - 24-11373S), Ministry of Education Youth and Sports (ERC-CZ-LL2327, FORTE CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004632), PRIMUS Research Programme (PRIMUS/21/SCI/017); EU: H2020 European Research Council (ERC - 101002463); European Union: European Research Council (BARD No. 101116429, ERC - 948254, ERC 101089007), European Regional Development Fund (SMASH COFUND 101081355, SLO ERDF), Horizon 2020 Framework Programme (MUCCA - CHIST-ERA-19-XAI-00), European Union, Future Artificial Intelligence Research (FAIR-NextGenerationEU PE00000013), Italian Center for High Performance Computing, Big Data and Quantum Computing (ICSC, NextGenerationEU); France: Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-21-CE31-0022, ANR-22-EDIR-0002); Germany: Baden-Württemberg Stiftung (BW Stiftung-Postdoc Eliteprogramme), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG - 469666862, DFG - CR 312/5-2); China: Research Grants Council (GRF); Italy: Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (ICSC, NextGenerationEU), Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (NextGenEU 153D23001490006 M4C2.1.1, NextGenEU I53D23000820006 M4C2.1.1, NextGenEU I53D23001490006 M4C2.1.1, SOE2024_0000023); Japan: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI JP22H01227, JSPS KAKENHI JP22H04944, JSPS KAKENHI JP22KK0227, JSPS KAKENHI JP23KK0245, JSPS KAKENHI JP24K23939); Norway: Research Council of Norway (RCN-314472); Poland: Ministry of Science and Higher Education (IDUB AGH, POB8, D4 no 9722), Polish National Science Centre (NCN 2021/42/E/ST2/00350, NCN OPUS 2023/51/B/ST2/02507, NCN OPUS nr 2022/47/B/ST2/03059, NCN UMO-2019/34/E/ST2/00393, UMO-2022/47/O/ST2/00148, UMO-2023/49/B/ST2/04085, UMO-2023/51/B/ST2/00920, UMO-2024/53/N/ST2/00869); Portugal: Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT); Spain: Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN & NextGenEU PCI2022-135018-2, MICIN & FEDER PID2021-125273NB, RYC2019-028510-I, RYC2020-030254-I, RYC2021-031273-I, RYC2022-038164-I); Sweden: Carl Trygger Foundation (Carl Trygger Foundation CTS 22:2312), Swedish Research Council (Swedish Research Council 2023-04654, VR 2021-03651, VR 2022-03845, VR 2022-04683, VR 2023-03403, VR 2024-05451), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW 2018.0458, KAW 2022.0358, KAW 2023.0366); Switzerland: Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF - PCEFP2_194658); United Kingdom: Leverhulme Trust (Leverhulme Trust RPG-2020-004), Royal Society (NIF-R1-231091); United States of America: U.S. Department of Energy (ECA DE-AC02-76SF00515), Neubauer Family Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors have contributed to the publication, being variously involved in the design and the construction of the detectors, in writing the software, calibrating subsystems, operating the detectors and acquiring data and finally analysing the processed data. The ATLAS Collaboration members discussed and approved the scientific results. This Article was prepared by a subgroup of authors appointed by the ATLAS Collaboration and subjected to an internal collaboration-wide review process. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Thomas Kuhr, Spandan Mondal and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

University of South Africa, Department of Physics, Pretoria, South Africa.

University of Zululand, KwaDlangezwa, South Africa.

Faculté des Sciences Semlalia, Université Cadi Ayyad, LPHEA-Marrakech, Morocco.

Departamento de Física Téorica y del Cosmos, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain

Universidad San Sebastian, Recoleta, Chile

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

The ATLAS Collaboration. Transforming jet flavour tagging at ATLAS. Nat Commun 17, 541 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65059-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65059-6