Abstract

Black carbon (BC) aerosols, with their strong light-absorbing ability, are major drivers of the global climate. In existing models, BC aerosols are simplified as a single core when determining radiative effects. Here, we found that 21% of BC aerosols contain multiple cores during a wildfire smoke observation. By considering dynamic effective medium approximation (DEMA) with Mie theory and assuming randomly distributed multi‒core BC, the light absorption was 1.81 times greater than that under the single‒core assumption for particles with overall diameters >400 nm and core diameters >200 nm. A machine learning emulator was developed for DEMA-based absorption enhancements and incorporated into a global atmospheric model. For global aerosol absorption, multi‒core BC particles lead to a 19% increase, especially in wildfire-affected regions. This study emphasizes the critical role of multi‒core BC particles in amplifying radiative forcing and the necessity to revise models for the simulation of BC climate impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Black carbon (BC) plays a uniquely critical role in shaping the Earth’s climate system through its radiative absorption ability and aerosol‒cloud interactions, which allow it to contribute to slow winds1, suppress the planetary boundary layer2, alter snow and ice melting conditions3, and generate other regional climate and weather changes4,5. Between 25 and 36% of global BC emissions originates from wildfires6,7, with the remainder originating primarily from energy-related combustion processes, such as those associated with residential solid fuels and fossil fuels6,8. The intensity and duration of wildfires are increasing globally due to the higher temperatures, drier vegetation, and longer dry seasons resulting from climate change5,9. When BC aerosols are coated by other nonabsorbing substances, the resulting lensing effect can significantly amplify their degree of light absorption, as quantified by the absorption enhancement factor, Eabs10,11,12,13. The Core–Shell Mie model, which is widely employed in atmospheric models (e.g., the Weather Research and Forecasting model coupled with Chemistry) can be used to obtain the light absorption enhancement (Eabs_CS) value of BC. In the Core‒Shell Mie model, it is assumed that there is one central BC core per particle (ncore = 1)14,15, and the BC mixing state is represented via the BC core diameter (Dc) and the particle-to-core diameter ratio (Dp/Dc). The total BC absorption level is represented by the black carbon absorption aerosol optical depth (BC AAOD; Methods), which depends on both Eabs and the BC mass in the atmospheric column16,17,18. On the basis of the third phase of the Aerosol Comparisons between Observations and Models intercomparison initiative (AeroCom), BC AAOD accounts for 36%–84% of the global annual mean of total absorption aerosol optical depth (AAOD) at the 550-nm wavelength, indicating that BC yields a relatively notable warming effect16,17,18. However, AeroCom and other global observations indicated that global models frequently underestimate BC AAOD, and a scaling factor of 1.4–2.8 is needed to ensure alignment with global observational data for subsequent radiation assessment6,17,18,19. A quantitative review of the BC AAOD is provided in Supplementary Text 1. Some model studies attributed this upscaling factor to uncertainties in emission inventories and BC mass loads; moreover, these researchers focused on constraining the representation of the mixing state of BC in global atmospheric models6,16,19.

Significant uncertainties exist in the mixing state and Eabs of BC in observations and simulations11,13. Fierce et al.20 proposed that accounting for particle-to-particle heterogeneity in the mixing state and the complex morphology of BC-containing particles may resolve these uncertainties. Moreover, Liu et al.10 and Fierce et al.20 reported that the Core‒Shell Mie model might oversimplify the nonspherical morphology of BC particles, leading to potential overestimation of the degree of light absorption at low Dp/Dc values (<~1.4). Chen et al.21 further proposed that nonsphericity contributes only marginally (3.3%) to the global BC AAOD. In field studies, researchers reported Eabs_CS values varying between 1 and ~1.5; these studies relied solely on single particle soot photometers (SP2) and obtained Eabs_CS values via the Core‒Shell Mie model22,23. Direct optical measurements conducted with a photoacoustic spectrometer, a particle soot absorption photometer, and other technologies were employed to determine the average Eabs values, which ranges from 1 to ~2.520,24 (refer to Supplementary Table 1 for details). It is well known that SP2 measurements and laboratory experiments typically exhibit an upper size limit of Dp < ~400 nm, with the detailed range depending on the SP2 configuration25,26. However, field studies roughly estimated that the contribution of BC-containing particles with Dp > 400 nm to the bulk BC mass and light absorption level could reach 50%, especially during polluted periods27,28. Detailed comparisons of Dp and Dc across model, field, and laboratory studies are summarized in Supplementary Text 2 and Supplementary Table 2. These findings highlight a gap in the understanding of how the mixing state of large particles (Dp > 400 nm) affects Eabs.

Our study is further inspired by considering the maximum Eabs value of ~4, which was reported in certain experiments and field studies29,30,31,32 and is consistent with the simulations of Fuller, et al.33. Importantly, the simulations by Fuller, et al.33 were based on the Dynamic Effective Medium Approximation (DEMA) with Mie theory under the assumption that multiple BC cores (ncore ≥ 1) are randomly distributed within particles33,34,35,36. However, the impacts on Eabs and BC AAOD have been neglected because of a lack of direct evidence for ncore > 1 in DEMA for ambient BC particles. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) enables detailed analysis of individual particles, and this technique effectively captures the mixing structure of BC-containing particles15,37. Multi‒core BC particles have occasionally been reported in previous studies on the basis of TEM (refer to Supplementary Table 3 for details), but their roles in driving radiative forcing and their connection to DEMA remain underexplored. One recent study confirmed that coagulation leads to the occurrence of multi‒core BC particles with Dp > 400 nm during long-range transport38. Some field studies have proposed that coagulation during the long-range transport of wildfire smoke drives the increase in the Dp value of BC-containing particles39,40,41,42. Satellite observations show that wildfire smoke produces a dense haze layer at 2000–4000 m above sea level (a.s.l.) from Southeast Asia to Yunnan Province, China4,43. Therefore, these wildfire events provide unique real-world laboratory setting for understanding BC light absorption and the changes in mixing states during transport, particularly for multi‒core BC aerosols.

To characterize the evolution of mixing states for transported BC, we conducted a field campaign at the Yunya Atmospheric Environment Research Observatory (YAREO) during the wildfire-affected periods. The station is located atop a mountain in Yunnan Province at 2200 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1). We quantified the impact of ncore on the size dependence of Eabs and the subsequent influence on BC AAOD with machine learning algorithms in a global atmospheric model. This study provides the insight into addressing the missing absorption enhancement resulting from multi‒core BC aerosols in global atmospheric models.

a 72-h backward trajectories arriving at 2000 m above ground level during the sampling periods (March 18-29, 2023), including highly polluted (HP) and less polluted (LP) periods. b1–b3 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of particles containing different number of black carbon (BC) cores (ncore). c Relative abundance of different particle types and the proportion of multi‒core BC particles (MC, ncore > 1) to all BC-containing particles. “Total”, “HP”, and “LP” represent the summary results during the whole periods, highly polluted periods, and less polluted periods, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Characteristics of aerosol particles

Highly polluted periods are defined as when the total mass of elemental carbon, organic matter, dust, and water-soluble inorganic ions exceeds 15 μg m−3 at the sample station (Supplementary Fig. 1). We found that mass concentrations of these aerosol chemical components during highly polluted periods were approximately 3 times higher than them during less polluted periods (e.g., elemental carbon in Supplementary Table 4). In Supplementary Fig. 2a, BC concentrations increased from 0.15 to 4.4 μg m−3 over the sampling period, driving BC AAOD to increase from 0.003 to 0.062 based on Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications version 2 (MERRA2). Additionally, Supplementary Fig. 2b-d show that regional BC concentration and BC AAOD during highly polluted periods were about three times higher than them during less polluted periods, while PM10 concentration at the downstream national monitoring station became double during highly polluted periods. Satellite data and air mass trajectories both indicated that south-westerly air masses passed over areas with intense fire activity in Southeast Asia during highly polluted periods, leading to regional pollution events at the downwind sampling site (Fig. 1a). In contrast, western trajectories from South Asia rarely passed over fire-affected regions during less polluted periods (Supplementary Fig. 3). These results suggested that the highly polluted periods were influenced mainly by the long-range transport of wildfire smoke from Southeast Asia, providing ideal real-world conditions for understanding BC ageing mechanisms during long-range transport.

In TEM images, BC particles appeared as fractal-like aggregates of soot, and they were either externally mixed as bare-like BC aerosols (Fig. 1b1) or BC aerosols coated with secondary aerosols (Fig. 1(b2–b3)) after undergoing ageing processes, such as condensation, coagulation, and cloud processing15,25. Among the 3950 analysed particles, 47% were BC-containing particles, comprising 33% coated BC particles and 14% bare-like BC particles (Fig. 1c), whereas the remainder were BC-free particles (Supplementary Fig. 4). In summary, multi‒core BC particles accounted for 21% of the BC-containing particles, 14% during the less polluted periods and 25% during the highly polluted periods (Fig. 1c). The detailed individual-particle analysis can be found in the Methods section and Supplementary Text 3.

During highly polluted periods, wildfire smoke after long-range transport could enhance the formation of multi‒core BC particles (Fig. 1a vs. Supplementary Fig. 3). However, few studies reported the size-dependent characteristics of multi‒core BC particles. Instead, some studies considered the two-dimensional data characteristics of Dp/Dc and Dc and the size distribution of Dc to approximately assess the mixing states of BC aerosols in biomass burning smoke and wildfire smoke26,44,45. To obtain the equivalent volume diameters of individual BC-containing particles and their BC cores (i.e., Dp and Dc, respectively), we calibrated the equivalent circle diameters obtained from TEM images to the equivalent volume diameters via a regression relationship from atomic force microscopy measurements (refer to the Methods). For multi‒core BC particles, Dc represents the diameter of a single sphere whose volume is equivalent to the sum of all BC core volumes. Figure 2a and Table 1 both show that multi‒core BC particles became the dominant particle type at Dc > 200 nm.

a Different colours represent the number of BC cores (ncore) in each particle, and the histogram is the number distribution of particles with different BC core size (Dc). Dc is the cumulative equivalent volume diameter of all BC cores in a particle. b Two-dimension distribution of particle-to-core diameter ratio (Dp/Dc) and Dc based on the transmission electron microscopy. The smooth line is used for all coated BC particles (black) and their fitting curve (purple). The Boundarycond line means the max Dp/Dc versus Dc via the condensation processing, and beyond Boundarycond line, changes in Dp/Dc are predominantly influenced by coagulation. The Boundarycond line is well described in Chen et al.38 and Sedlacek et al.25. c The range of ncore in different size bins based on the diameter of the whole particle (Dp).

Figure 2b shows that the average Dp/Dc ratio first decreased with increasing Dc, and then remained relatively constant for particles with Dc > 200 nm. This relationship was well fitted by the following equation: Dp/Dc = 2.5 + 6.3×Exp(-Dc/63) (purple line in Fig. 2b). The fitting results revealed that the average Dp/Dc ratio remained steady at 2.5, mainly for Dp > 400 nm (blue and green dots in Fig. 2b). Similar plateau values of Dp/Dc were reported for Southeast Tibetan Plateau (~ 2.2)38 and during a transboundary transport event in Beijing (~ 2.4)44. If condensation dominated the BC aging mechanism (ncore = 1), particles with smaller Dc values would exhibit higher Dp/Dc values when coated with the same volume of condensate aerosols25. Specifically, Dp/Dc was expected to approach ~1 with increasing Dc value. The blue line shown in Fig. 2b represents the maximum Dp/Dc value under the condensation mechanism described by Chen et al.38 and Sedlacek et al.25. Figure 2b shows that particles with Dp > 400 nm (blue and green dots) were above the blue line. Below this blue line, condensation dominated the BC ageing process, maintaining the ncore value at 1 (Fig. 2c). Above the blue line, coagulation dominated the ageing process, resulting in an increase in the ncore value (i.e., ncore > 1) (Fig. 2c).

Box models developed by Matsui et al.46 and Riemer et al.47 revealed that thickly coated BC particles were dominated by coagulation rather than by condensation. They concluded that the number of coagulation events increased with increasing Dp and peaked at Dp > ~400 nm46. Several field studies proposed that coagulation could account for most of the increase in particle size (Dp) in wildfire smoke39,40,41,42. Theoretically, coagulation between two BC-containing particles could increase ncore and produce a larger Dc value46. In this study, multi‒core BC particles were observed in the TEM images (Fig. 1b3), thus providing direct evidence of coagulation among BC-containing particles. Figure 2c shows that the range of ncore increased with increasing Dp: for example, ncore ranged from 1 to 5 for Dp between 400 and 600 nm, and from 1 to 8 for Dp ≥ 800 nm. We observed a critical condition near Dp > 400 nm and when ncore transitioned from 1 to > 1 (Fig. 2c). This phenomenon was also observed in the Southeast Tibetan Plateau38 and Amakusa City, Japan48. Table 1 indicates that multi‒core BC particles became the dominant type of coated BC particles for Dp > 400 nm and Dc > 200 nm. To facilitate parameterization, we defined two proxy features (M1 and M2), as expressed in Eq. (1), to represent the primary size characteristics of multi‒core BC particles and their subsequent impact on Eabs. In 1310 coated-BC particles, 20% simultaneously satisfied M1 = 1 and M2 = 1 (i.e., M1×M2 = 1), in which the number of multi‒core BC particles was three times greater than that of single-core BC particles (Table 1).

Optical absorption enhancement

In this study, we employed an electron-microscopy-to-BC simulation tool, coupled with discrete dipole approximation (EMBS–DDA)37 to visualize the effect of ncore on Eabs of BC-containing particles. The EMBS tool provides an interactive interface for designs of particles with different sizes and positions of cores that are input into the DDA module to calculate their optical properties37. To explain the differences between single-core and multi‒core BC particles, we further adopted the near-field calculation algorithm of DDA49,50,51 to simulate the light electric field intensity inside and around scattering particles (i.e., secondary aerosols) and coated BC particles, respectively.

BC-containing particles were assigned different ncore values and positions in the EMBS–DDA simulations, whereas Dp/Dc was set to the average value (i.e., Dp/Dc = 3 in Supplementary Fig. 5) to represent the common scenario for Dp > 400 nm. Under the assumption that BC cores were randomly located in an individual particle, the probability of core occurrence obviously increased from the centre to off-centre positions. Specifically, BC aerosols with a single core or multiple cores at the particle centre represented idealized and specialized scenarios, respectively. Innumerable possible core locations would increase the DDA simulation burden of every configuration excessively, even with fixed input parameters of Dp, Dc, and ncore. Herein, we simulated three representative scenarios using DDA:

DDA1: Setting ncore = 1 with the core at the centre. The simulated Eabs value was almost equal to that of the Core‒Shell Mie model, as shown in Fig. 3a–b.

a Simulation results of different methods for different diameters of BC cores (Dc). Dc is the cumulative equivalent volume diameter of all BC cores in a particle. Input parameters and simulation outputs are detailed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. b Schematic diagrams illustrate typical mixing states for different discrete dipole approximation simulations (DDA1, DDA2, and DDA3), each with distinct core configurations. c1–c6 Near-field calculations were employed to determine the electric field intensity at 550 nm for secondary aerosol particles (c1) and various DDA scenarios (DDA1: c2, DDA2: c3-4, DDA3: c5-6), with the diameter of the whole particle (Dp) at 600 nm. Supplementary Fig. 9 also provides simulation results for Dp = 300 nm. White lines represent the border of particles, and black line marks the location of the BC cores. The colour represents the normalized electric field intensity versus the incident light (dimensionless).

DDA2: Setting ncore > 1 with multiple cores concentrated near the centre, as shown in Fig. 3b.

DDA3: Setting ncore > 1 with cores distributed at various off-centre positions, as shown in Fig. 3b. The detailed settings are provided in Supplementary Text 4, Supplementary Tables 5–6, and Supplementary Fig. 6. In addition, we calculated Eabs via the Core–Shell Mie and DEMA–Mie models on the basis of the same input parameters (Dp, Dc, and ncore) used in DDA. Each core is the same size in the particles in DDA1-DDA3, and Supplementary Fig. 7 shows the simulations with different sizes of BC cores (Diff. Size). In Supplementary Fig. 7, Diff. Size shows a similar range of Eabs with DDA1-DDA3, which supports the assumption in Jacobson52: it is ideal to track a size distribution of BC within coated BC particles of each size, but a monodisperse distribution of BC within coated particles was used for quick optical simulations.

We found that the Eabs values for ncore = 1 were 12–222% lower than those for ncore > 1, particularly in DDA3 scenarios (Supplementary Table 6). Figure 3a shows that the DEMA–Mie could represent the average increasing trend in DDA3. Notably, the DEMA–Mie model accounted for scenarios with ncore ≥ 1 in which the cores were randomly distributed, but their exact locations were not specified in DDA. We compared the Eabs ranges (from minimum to maximum) obtained via the DEMA–Mie and DDA3 simulations. Figure 3b shows that the Eabs range from the DDA3 simulations agreed well with that from the DEMA–Mie model. The results further confirmed that DEMA–Mie was efficient for simulating the average impact of ncore at random positions on Eabs.

Supplementary Fig. 8 shows that the light electric field intensity was enhanced (lensing effect) in the off-centre region of a secondary scattering particle, which is consistent with the experiment findings of Arroyo, et al.50 and Li, et al.53. The intensity of the enhanced field, as indicated by colour, was particularly high for Dp > 400 nm (Supplementary Fig. 8). We further modelled the electric field intensity for coated BC particles with various ncore values, as shown in Fig. 3(c1–c6) for Dp = 600 nm and Supplementary Fig. 9 for Dp = 300 nm. Figure 3(c1–c6) show the enhanced presence of white and orange areas in the regions marked by black circles, suggesting that DDA2 and DDA3 exhibited higher Eabs values than did the DDA1 simulations. In Supplementary Fig. 9, a smaller colour gradient indicates a weaker lensing effect for Dp = 300 nm, but the difference in Eabs between Core-Shell structure and multi-core structure is still up to 1 (DDA1 vs. DDA3). Kahnert et al.54 also proposed that the energy field rapidly attenuated within a solid BC sphere, which limits the contribution of the core mass near the particle centre to light absorption. Moreover, Beeler and Chakrabarty55 defined a phase shift parameter to describe a simulation like Fig. 3c2. However, in these previous simulations, multi‒core BC particles were not employed as input parameters.

Eabs_DEMA exhibited a quasilinear increase with the logarithm of Dp/Dc under M1×M2 = 0 for all 1310 coated BC particles (black line in Fig. 4a). Notably, the particles with M1×M2 = 1 (red dots in Fig. 4a) exhibited higher Eabs_DEMA values than did those with M1×M2 = 0 (blue dots) for the same Dp/Dc value. In contrast, the Core‒Shell Mie model showed that Eabs_CS first increased with increasing Dp/Dc and then plateaued at ~2 for M1×M2 = 1 (red dots in Fig. 4b). The differences between Eabs_DEMA and Eabs_CS indicated that Eabs_DEMA was 1.17 and 1.81 times greater than Eabs_CS for M1×M2 = 0 and 1, respectively (Fig. 4c).

M1×M2 = 1 represents the particles with the diameter of black carbon (BC) cores (Dc) larger than 200 nm and the diameter of the whole particle (Dp) larger than 400 nm. Dc is the cumulative equivalent volume diameter of all BC cores in a particle. a Fitting of Eabs_DEMA for particles with M1×M2 = 0 (blue points) using the dynamic effective medium approximation with Mie model (DEMA–Mie). b Lines showing the increase in Eabs as the particle-to-core diameter ratio (Dp/Dc) increases across various Dc values under the Core‒Shell Mie model (Eabs_CS). c Comparison analysis of differences between Eabs_DEMA and Eabs_CS for M1×M2 = 0 and 1, respectively. d Impacts on Eabs_DEMA shown as different SHAP values for each input feature via SHapley Additive ExPlanation (SHAP) approach. Further details on SHAP are in the Methods section. e–i Impacts of primary input features on Eabs_DEMA quantified by the SHAP values.

In summary, these findings suggested that the Core‒Shell Mie model could significantly underestimate the light absorption of BC-containing particles when M1×M2 = 1. However, the DEMA–Mie model could be a suitable and efficient tool for simulating the optical properties of multi‒core BC particles. Therefore, the developed DEMA–Mie model provides a more favourable balance between computational efficiency and physical representation than the DDA and Core‒Shell Mie models.

Machine learning emulator

In previous global simulations, the developers of DEMA52,56,57 used a noninteger ncore,cal value (i.e., Dc3/1,000,000) to approximate ncore. However, Wang, et al.58 proposed that a noninteger ncore,cal value was implausible because observational evidence for multi‒core BC particles was lacking. Therefore, it was necessary to parameterize the impact of ncore on Eabs on the basis of the real-world size dependence of ncore. We employed a random forest (RF) model to predict Eabs_DEMA and quantify how Eabs_DEMA changed with the mixing state of coated BC. On the basis of 1310 samples (coated BC particles), we developed two RF emulators (RF1 and RF2) for Eabs_DEMA, with input features including Dp/Dc, Dc, Dp, Eabs_CS, ncore, ncore,cal, M1, M2, and M1×M2. RF1 included all the input features, whereas RF2 excluded ncore, which was generally unavailable in global models. SHapley Additive ExPlanation (SHAP) values, rooted in coalitional game theory59, were employed to distribute the total effect of each input feature on the predicted Eabs_DEMA for individual particles (refer to the Methods). By comparing the prediction performance levels and SHAP values of RF1 and RF2, we determined whether M1×M2 could serve as a proxy for the impact of ncore on Eabs_DEMA.

RF1 performed well for both the training and test datasets, achieving an R2 value of 0.96 (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 7). Figure 4d shows that Dp/Dc, Dc, Dp, and Eabs_CS were the primary driving features due to their broad SHAP value distributions. Notably, the SHAP distributions for ncore and M1×M2 exhibited a T shape, indicating that there was a threshold effect on Eabs_DEMA (Fig. 4d). To enhance the interpretability of the RF predictions, we visualized the SHAP values corresponding to each feature value. Figure 4(e–i) show the driving patterns of these primary features on Eabs_DEMA. Each point represents an individual particle, and its colour is indicative of its M1×M2 value to illustrate how M1×M2 influences the driving patterns of these features (Fig. 4e–i). Figure 4e shows that ncore was positively correlated with its SHAP values only when M1×M2 = 1; otherwise, the SHAP values were approximately 0. These results suggested that the impact of ncore on Eabs_DEMA was the most significant for particles with M1×M2 = 1. Figure 4f shows a positive correlation between Dp/Dc and its SHAP value, with a steeper trend for particles with M1 × M2 = 1 (red) that that of particles with M1×M2 = 0 (blue). This result indicated a greater increase in Eabs_DEMA with increasing Dp/Dc for M1×M2 = 1. Figure 4g shows that Eabs_CS positively correlated with its SHAP value overall, except for particles within the grey-shaded region where Eabs_CS ≈ 2. For these particles, the SHAP value was close to zero when M1×M2 = 1 (red in Fig. 4g), suggesting that Eabs_CS had predictive utility for Eabs_DEMA for M1×M2 = 0 but not for M1×M2 = 1. The increasing Dp value led to a greater increase in Eabs_DEMA with M1×M2 = 1 (Fig. 4h), whereas the transition of M1×M2 from 0 to 1 altered the correlation of Dc with its SHAP value from negative to positive (Fig. 4i). These findings suggested that Dp and Dc exerted a nonlinear driving effect on Eabs_DEMA and that BC cores with M1×M2 = 1 exhibited more notable interactions with light. Similar patterns were observed when ncore (Supplementary Fig. 11) was used to explain the driving patterns in RF1 compared with when M1×M2 was used, as shown in Fig. 4(f–i). We concluded that M1×M2 could serve as a proxy for the impact of ncore on Eabs_DEMA.

To assess the predictive performance of Eabs_DEMA without ncore as an input feature, we performed additional tests to construct RF2. In RF2, the input features included Dp/Dc, Dc, Dp, Eabs_CS, ncore,cal, M1, M2, and M1×M2. RF2 performed comparably to RF1, achieving an R2 value of 0.95 (vs. 0.96 for RF1) and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.14 (vs. 0.17 for RF1) (Supplementary Table 7). The SHAP value distributions remained consistent between RF1 and RF2 (Supplementary Fig. 12 vs. Figure 4), further confirming that M1×M2 could effectively replace ncore for predicting Eabs_DEMA in machine learning models.

Implications for the atmospheric model

Multi‒core BC particles are not exclusive to wildfire smoke events but are instead widely observed in other environments, as listed in 11 additional studies in Supplementary Table 3. However, these studies did not focus on multi‒core particles or their optical properties. To evaluate the global impact of multi‒core BC particles on the bulk optical properties of dry aerosols, we coupled the Community Atmosphere Model with the Aerosol Two-dimensional bin module for foRmation and Aging Simulation (CAM–ATRAS, a global model) and the RF2 model offline (refer to the Methods and Supplementary Fig. 13). CAM–ATRAS model showed that wildfire sources dominated BC sources in regions such as South Africa and South America (Supplementary Figs. 14a–c). The long-range transport of wildfire emissions from Southeast Asia to southern China frequently increased the BC loadings in March (Supplementary Figs. 14d–e). The global distribution of particles with M1×M2 = 1 overlapped with wildfire hotspots (Supplementary Figs. 15a–e) and regions of intensive anthropogenic emissions (Supplementary Figs. 15f–g). In these areas and downstream regions, such as oceans and the Tibetan Plateau, particles with M1×M2 = 1 accounted for ~2% of the total number and ~30% of the mass of BC in the atmospheric column (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 16–17). Figure 5b shows that the global average BC AAOD was 2.04 × 10−3 under the Core–Shell Mie model but increased to 2.42 × 10−3 under the DEMA–Mie model. These large differences occurred mainly in high-emission regions such as China, India, and South Africa, where the elevated BC AAOD was driven by the number concentrations (NM1×M2=1) of particles with M1×M2 = 1 in the atmospheric column (Supplementary Fig. 18 and the blue contours in Fig. 5b). Furthermore, the relative difference in the BC AAOD was 19% globally. Hot spots (> 19%, red colour in Supplementary Fig. 19) were located downstream of high-emission regions, due to the higher fraction of particles with M1 × M2 = 1 (Supplementary Figs. 16-17), which highlighted the role of transported aerosols in determining the BC AAOD.

a A conceptual scheme of wildfire smoke in transport. b Global distribution of annually average differences in BC AAOD using Core‒Shell (CS) model and dynamic effective medium approximation (DEMA) with Mie theory (DEMA–Mie) respectively. Blue lines mark the area where the number concentration reaches 1010 m-2 for BC-containing particles with the diameter (Dp) larger than 400 nm and the diameter of BC cores (Dc) larger than 200 nm (i.e., M1×M2 = 1) in the atmospheric column. Green point is the sample station.

We highlighted the enhanced light absorption due to multi‒core BC particles and acknowledged the potential overestimation of Eabs simulations due to the nonsphericity of BC particles at low Dp/Dc values10,20. In their experiment, Liu et al.10 measured a value of Eabs near 1 for Dp/Dc < 1.4, whereas the calculated Eabs_CS value increased with increasing Dp/Dc. Our study could address the gap in that of Liu et al.10, where Eabs and the mixing state were clearly marked as unknown for Dp/Dc > 3 owing to the upper measurement limit of the SP2 instrument (i.e., Dp < ~400 nm). We conducted a sensitivity analysis by setting Eabs at 1 for Dp/Dc < 1.4 and using RF2 in CAM–ATRAS to compare the relative importance due to nonsphericity and multi‒core nature of BC particles. We defined a ratio between the DEMA-derived increase and the nonsphericity-derived decrease in the global BC AAOD (refer to the Methods). According to Supplementary Fig. 20, this ratio could increase by up to fourfold across the downstream areas of high-emission regions, particularly in wildfire areas such as Southeast Asia and the sample station of this study.

We evaluated the impacts of multi‒core BC particles in dry aerosol particles by using a real-world ncore value rather than the assumed ncore,cal value, integrating microscale individual-particle analysis with optical simulations and global models. BC-containing particles could be activated into cloud condensation nuclei when the humidity increases15,60. Via a rough estimation that involved replacing ncore with ncore,cal for individual cloud droplets, Jacobson35,52 reported that the DEMA‒Mie model could yield a greater near-surface temperature increase (+33%), greater heating rate (+130%), and a larger number of interstitial aerosol particles (+140%), compared to the Core‒Shell Mie model. However, accurately parameterizing the changes in ncore during aerosol‒cloud interactions remains a significant challenge, particularly during long-range transport and cloud processes. Therefore, we propose that future global and regional models should incorporate multi‒core BC scenarios, potentially for particles with Dp > 400 nm and Dc > 200 nm, to increase the accuracies of BC light absorption and radiative forcing predictions. Our study highlights the missing absorption enhancement of multi‒core BC aerosols in ambient air, which helps improve the atmospheric modelling of these aerosols and their potential climatic impacts.

Methods

Aerosol collection and measurement

Aerosol samples were collected from 18 to 29 March 2023 at the Yunya Atmospheric Environment Research Observatory station of the Chinese Academy of Science in Woyun Mountain, west of Kunming, Yunnan Province (25.16 N, 102.4 E, 2200 m a.s.l. in Fig. 1a). A KB-120F sampler with a flow rate of 100 L min−1 was used to collect PM10 samples (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter ≤ 10 μm) on 90-mm-diameter quartz filters for 11.5 h (09:30–21:00 for the daytime; 21:30–09:00 for the nighttime in Beijing time). The chemical composition of PM10 was analysed (refer to Supplementary Text 5 for more details). Hourly PM10 data were downloaded from the China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (https://air.cnemc.cn: 18007/). MERRA2 provided the hourly mass concentrations of BC and the BC AAOD at 550 nm during the sampling periods (https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/MERRA-2/).

Individual particle collection and morphological analysis

A portable DKL-2 sampler (Genstar Electronic Technology, China) equipped with a 0.5-mm jet nozzle was employed to collect individual aerosol particles. The particles were collected on a copper grid coated with a carbon film (carbon Type-B, 300-mesh copper; Tianld Co., China) and silicon wafers. These samples were collected at 3:00, 9:00, 15:00, and 21:00 Beijing time for 15–40 min and stored in plastic capsules under low relative humidity (RH = 20-25%). Twelve samples were selected, and a total of 3950 particles were analysed via TEM (JEOL JEM-2100, Japan) in combination with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS; INCA X-MaxN 80 T, Oxford Instruments, United Kingdom). The strong electron beam of TEM could easily damage the coating of the coated BC particles61. Therefore, we determined the morphology and number of BC cores in an individual particle with this technique, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 21.

RADIUS software (EMSIS GmbH, Germany) was adopted to measure the morphological features of individual particles in the TEM images, e.g., the equivalent circle diameter (ECD) and bearing area (A). Additionally, individual particles on silicon wafers were measured via atomic force microscopy (AFM). Gwyddion 2.64 software (http://gwyddion.net/) was used to automatically obtain the bearing area (A) and bearing volume (V) of 165 individual particles. The ECD and equivalent volume diameter (EVD) of individual particles were calculated according to the following Eqs. (2–3)48:

where A is the bearing area, nm2; V is the bearing volume, nm3; ECD and EVD are the equivalent circle diameter and the equivalent volume diameter, nm, respectively.

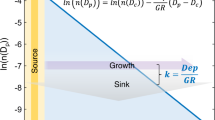

A bootstrap linear regression analysis was used to obtain the transform ratio between the ECD and EVD. Through bootstrap analysis, we could use a limited dataset to estimate the slope coefficients in the regression equation by resampling 1000 times with replacement, which could increase the credibility and robustness of the results. The final equation was EVD = 0.54 × ECD, with an R2 value of 0.99 (Supplementary Fig. 22). Consequently, a slope factor (k) of 0.54 was adopted to estimate the EVD from the ECD for all the particles in the TEM images. In this study, Dp was represented by the EVD of the whole particles (coating + BC cores). We used Eq. (4) to obtain Dc for all BC-containing particles.

where Dc is the cumulative equivalent volume diameter of all BC cores in a particle; ncore is the number of BC cores; the subscript i denotes the ith core; Acore is the bearing area obtained from the TEM images; k is the average transform ratio between the ECD and the EVD obtained via AFM, i.e., 0.54 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 22.

Light absorption enhancement (E abs)

In the DEMA–Mie model, it is assumed that one or multiple spherical BC cores are randomly distributed within one particle. The effective refractive index of the whole BC-containing particle (\(\epsilon\)) could be obtained via Eq. (5)34,62,63. The Mie model was subsequently used to calculate the optical properties at a wavelength of 550 nm.

where r is the radius of a BC core, and n(r) is the number concentration of cores per unit radius interval. The multi-BC cores cause complex light interactions and influence Eabs, which was considered as the third term in Eq. (5)52,62. Without the third term, Eq. (5) transforms into the Bruggeman mixing rule34,52. Owing to the lack of observational evidence for ncore, the developers of DEMA52,56,57 used a noninteger ncore,cal value (i.e., Dc3/1,000,000) to approximate ncore. Individual particle analysis provided ncore values using TEM (e.g., ncore = 6 in Fig. 1b3). Notably, λ is the light wavelength, and we selected a value of 550 nm for one case. \({\epsilon }_{c}\) and \({\epsilon }_{{coat}}\) are the dielectric constants of BC and other aerosol components, respectively, which could be transformed via the widely used refractive index (RI) through the procedure outlined in Supplementary Text 6. According to the literature, the RI values are 1.85 + 0.71j for BC aerosols and 1.53 + 0j for coating aerosols37,64. Finally, the complex Eq. (5) was solved using the Newton‒Raphson method, and the details are provided in Supplementary Text 6.

PyMieScatt, an open-source Python package, was used to calculate Eabs via Eq. (6), according to the Core‒Shell Mie (Eabs_CS) and DEMA–Mie models (Eabs_DEMA), respectively14,65.

where Cabs,p and Cabs,c are the absorption cross sections of the coated BC particles and the bare BC particles, respectively. When the DEMA–Mie model is used, Cabs,c is calculated for spherical BCs with the same Dc. To compare Eabs_CS and Eabs_DEMA, we applied EMBS–DDA model as a reference37 and constructed different particle shapes with various Dc and ncore values at the same Dp/Dc. Details are provided in Supplementary Text 4.

Random forest (RF) and Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) approach

Both field and modelling studies face challenges in measuring and simulating ncore per particle58. Therefore, it is essential to quantify the potential nonlinear impact of ncore on Eabs_DEMA and to develop an emulator for Eabs_DEMA via the use of other features as proxies for ncore. We employed the RF model to create an emulator to predict Eabs_DEMA. We divided 1310 samples (coated BC particles) as follows: 70% were used for the training set, and 30% were used for the test set. Finally, two emulators were developed: RF1 included all input features, such as Dp/Dc, Dc, Dp, Eabs_CS, ncore, ncore,cal, M1, M2, and M1×M2; RF2 excluded ncore and included other parameters. Furthermore, the SHAP approach was employed to distribute the total effect on the predicted Eabs_DEMA of each input feature59. According to coalitional game theory, the difference in model predictions involving a feature j (e.g., ncore) compared with the predictions without j was attributed to the marginal contribution of this feature. Considering the interactive effects between features, differences were computed for every possible feature subset combination of each sample66. For each particle sample, K features were input to generate the prediction for Eabs_DEMA, denoted as f(xi), including a linear function of feature attribution in Eq. (7).

where K is the total number of features; N is the total samples; f(xi) is the predicted Eabs_DEMA value for the ith particle via the RF model in this study; and \({\Phi }_{j}\left(f,x\right)\) is the SHAP value, which quantifies the impact of feature j on the prediction for input xi in the built model. Specifically, the contribution of ncore (i.e., j = ncore) of the ith particle (xi) to Eabs_DEMA was denoted the SHAP (xi, j) value in Eq. (7), as shown by the scatter in Fig. 4e. The base value, \({\Phi }_{0}\left(f,x\right)\) was the average value of the predicted results. SHAP calculations were performed using the kernelshap and shapviz R packages, whereas the RF model was trained using the randomForest R package.

Parameterization and global model simulations

In many global models, accumulation-mode aerosols are oversimplified and represented by only a few mixing states57,67. As a result, BC-free particles are often misclassified as a coating on BC particles, leading to an 18–44% overestimation of the BC AAOD21,57 (refer to Supplementary Text 1 for details). Although correcting this uncertainty is not our direct objective, we must ensure that BC-free particles do not confound our simulations and examination of the Core‒Shell Mie and DEMA–Mie models. To address this issue, we selected the CAM–ATRAS, in which 40 mixing state bins are employed to represent accumulation-mode aerosols, including BC-free particles and various BC-containing particles35,57,68. The CAM–ATRAS model achieves satisfactory performance against a wide range of surface, aircraft, and satellite observations, particularly within the AeroCom III (Aerosol Comparisons between Observations and Models) framework18,46,67,69. AeroCom III is an open international initiative aimed at better understanding global aerosols and their impact. The dataset produced by the 17 models participating in AeroCom III, including the CAM–ATRAS, has been extensively adopted across multidisciplinary studies18,19.

In the CAM–ATRAS, accumulation-mode particles with dry diameters (Dp) ranging from 40 nm to 1250 nm were classified into 5 size bins. Then eight BC mixing state bins were further defined on the basis of the mass ratio of BC to total dry aerosols, ranging from 0% to 100%, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. Via the use of these 40 two-dimensional mixing state bins, the CAM–ATRAS simulated various aerosol processes, including emission, new particle formation, condensation, coagulation, activation into cloud droplets, aqueous-phase chemistry, and deposition68,69,70. The model setup aligned with AeroCom III18: emission data were taken from monthly anthropogenic emissions based on the Community Emissions Data System8 and Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED) version 4.171 (https://www.globalfiredata.org/), in which wildfire emissions were explicitly defined. The simulations were conducted with a horizontal resolution of 1.9° latitude × 2.5° longitude, 30 vertical layers (extending up to ~40 km), and monthly average outputs for the 2008–2015 period18,68,69,70.

Via the use of this model, we evaluated changes in the BC AAOD at 550 nm wavelength with and without considering multi‒core BC particles. The analysis involved the following steps. (1) Dp and Dc were calculated on the basis of aerosol number concentrations, mass, and density of each aerosol composition of the 40 bins. (2) In the base scenario, Dp and Dc were used to run the Core‒Shell Mie model and obtained Eabs_CS. (3) Dp and Dc were transformed into ncore,cal, M1, M2, and M1×M2, which were then input into RF2 along with Dp/Dc, Dc, Dp, Eabs_CS, ncore,cal, M1, M2, and M1×M2 to obtain Eabs_DEMA for each mixing state bin. (4) Eabs_CS and Eabs_DEMA were substituted into Eq. (8) to calculate the BC AAOD offline, BC AAODCS, and BC AAODDEMA, respectively. The detailed workflow is shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. Matsui, et al.57 demonstrated that BC AAOD results from offline calculations closely aligned with those from online simulations using the Core‒Shell Mie model.

where z denotes the 30 levels for height and k denotes the mixing state bins for BC-containing particles; dh and ρ are the grid cell height and air density for each level, respectively; N is the aerosol number concentration for each mixing state bin; Cabs,c and Eabs are the same as those in Eq. (6).

Sensitivity analysis

We highlight the enhanced light absorption ability resulting from multi‒core BC particles while acknowledging the potential overestimation in the findings of Eabs simulations due to the nonsphericity of BC at low Dp/Dc values10,20. An experiment by Liu, et al.10 revealed that the measured Eabs value approached 1 for Dp/Dc < 1.4, but the modelled Eabs_CS value increased with increasing Dp/Dc. We set Eabs_CS and Eabs_DEMA at 1 for Dp/Dc < 1.4 and then substituted Eabs_CS and Eabs_DEMA into Eq. 8 for Dp/Dc > 1.4 to calculate BC AAOD again; these values were referred to as BC AAOD*CS and BC AAOD*DEMA, respectively. We estimated the contribution ratio using Eq. (9) to assess the relative importance of the global BC AAOD simulation due to nonsphericity and multi‒core BC.

Data availability

The Fire Information during the sampling period is provided by https://firms.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/map/. The observation and simulation data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28225802]72. CAM-ATRAS model simulation results are available upon request from the author (H.M.). The transmission electron microscopy images are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

Code for modelling absorption with DEMA–Mie is available from the author (M.J.). The Mie optical calculations are performed with PyMieScatt, which is available at https://github.com/bsumlin/PyMieScatt. 72-h backward trajectories are performed by MeteoInfo_3.5.2 (http://meteothink.org/). The code of the EMBS is available online (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13606304). The source code of DDA (DDSCAT 7.3.3) can be obtained online (http://ddscat.wikidot.com/). Code related to the RF1 and RF2 is available at [https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28225802]72. Additional code may be requested from the corresponding authors.

References

Jacobson, M. J. & Kaufman, Y. J. Wind reduction by aerosol particles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L24814 (2006).

Ding, A. J. et al. Enhanced haze pollution by black carbon in megacities in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2873–2879 (2016).

Coppola, A. I. et al. The black carbon cycle and its role in the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 516–532 (2022).

Ding, K., et al. Aerosol-boundary-layer-monsoon interactions amplify semi-direct effect of biomass smoke on low cloud formation in Southeast Asia. Nat. Commun. 12, 6416 (2021).

Xu, R. et al. Global population exposure to landscape fire air pollution from 2000 to 2019. Nature 621, 521–529 (2023).

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5380–5552 (2013).

Xu, H. et al. Updated global black carbon emissions from 1960 to 2017: improvements, trends, and drivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 7869–7879 (2021).

Hoesly, R. M. et al. Historical (1750–2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 369–408 (2018).

Jones, M. W. et al. Global rise in forest fire emissions linked to climate change in the extratropics. Science 386, eadl5889 (2024).

Self, E. C. et al. Black-carbon absorption enhancement in the atmosphere determined by particle mixing state. Nat. Geosci. 10, 184–188 (2017).

Cappa, C. D. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements due to the mixing state of atmospheric black carbon. Science 337, 1078–1081 (2012).

Jacobson, M. Z. A physically-based treatment of elemental carbon optics: implications for global direct forcing of aerosols. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 217–220 (2000).

Jacobson, M. Z. Strong radiative heating due to the mixing state of black carbon in atmospheric aerosols. Nature 409, 695–697 (2001).

Sumlin, B. J., Heinson, W. R. & Chakrabarty, R. K. Retrieving the aerosol complex refractive index using PyMieScatt: a Mie computational package with visualization capabilities. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 205, 127–134 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Microphysical properties of atmospheric soot and organic particles: measurements, modeling, and impacts. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 65 (2024).

Lund, M. T. et al. Concentrations and radiative forcing of anthropogenic aerosols from 1750 to 2014 simulated with the OsloCTM3 and CEDS emission inventory. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 4909–4931 (2018).

Chiu, R. Y. et al. Exploiting simultaneous observational constraints on mass and absorption to estimate the global direct radiative forcing of black carbon and brown carbon. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 10989–11010 (2014).

Sand, M. et al. Aerosol absorption in global models from AeroCom phase III. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 15929–15947 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Multi-angular polarimetric remote sensing to pinpoint global aerosol absorption and direct radiative forcing. Nat. Commun. 13, 7459 (2022).

Fierce, L. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements by black carbon controlled by particle-to-particle heterogeneity in composition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 5196–5203 (2020).

Chen, G., Liu, C., Wang, J., Yin, Y. & Wang, Y. Accounting for black carbon mixing state, nonsphericity, and heterogeneity effects in its optical property parameterization in a climate model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 129, e2024JD041135 (2024).

Zeng, L. et al. Overestimation of black carbon light absorption due to mixing state heterogeneity. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 2 (2024).

Zhao, G., Tan, T., Zhu, Y., Hu, M. & Zhao, C. Method to quantify black carbon aerosol light absorption enhancement with a mixing state index. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 18055–18063 (2021).

Che, H. et al. Seasonal variations in fire conditions are important drivers in the trend of aerosol optical properties over the south-eastern Atlantic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 8767–8785 (2022).

Sedlacek, A. J. et al. Using the black carbon particle mixing state to characterize the lifecycle of biomass burning aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14315–14325 (2022).

Schwarz, J. P. et al. Measurement of the mixing state, mass, and optical size of individual black carbon particles in urban and biomass burning emissions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 33968 (2008).

Zhao, W. et al. Measurement report: size-resolved mass concentration of equivalent black carbon-containing particles larger than 700 nm and their role in radiation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 14889–14902 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Significant contribution of coarse black carbon particles to light absorption in North China Plain. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 9, 134–139 (2022).

Yus-Díez, J. et al. Absorption enhancement of black carbon particles in a Mediterranean city and countryside: effect of particulate matter chemistry, ageing and trend analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 8439–8456 (2022).

Mikhailov, E. F., Vlasenko, S. S., Podgorny, I. A., Ramanathan, V. & Corrigan, C. E. Optical properties of soot–water drop agglomerates: an experimental study. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 111, D07209 (2006).

Li, H. et al. Relationship between light absorption properties of black carbon and aerosol origin at a background coastal site. Sci. Total Environ. 886, 163863 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Sources and physicochemical characteristics of black carbon aerosol from the Southeastern Tibetan Plateau: internal mixing enhances light absorption. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 4639–4656 (2018).

Fuller, K. A., Malm, W. C. & Kreidenweis, S. M. Effects of mixing on extinction by carbonaceous particles. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 104, 15941–15954 (1999).

Chýlek, P., Ramaswamy, V. & Cheng, R. J. Effect of graphitic carbon on the albedo of clouds. J. Atmos. Sci. 41, 3076–3084 (1984).

Jacobson, M. Z. Investigating cloud absorption effects: global absorption properties of black carbon, tar balls, and soil dust in clouds and aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 117, D06205 (2012).

Jacobson, M. Z. Short-term effects of controlling fossil-fuel soot, biofuel soot and gases, and methane on climate, Arctic ice, and air pollution health. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 115, D14209 (2010).

Fan, M. et al. Nonlinear enhancement of radiative absorption by black carbon in response to particle mixing structure. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, 96437–97697 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Quantifying evolution of soot mixing state from transboundary transport of biomass burning emissions. iScience 26, 108125 (2023).

June, N. A. et al. Aerosol size distribution changes in FIREX-AQ biomass burning plumes: the impact of plume concentration on coagulation and OA condensation/evaporation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 12803–12825 (2022).

Sakamoto, K. M. et al. Aged boreal biomass-burning aerosol size distributions from BORTAS 2011. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 1633–1646 (2015).

Hodshire, A. L. et al. Dilution impacts on smoke aging: evidence in Biomass Burning Observation Project (BBOP) data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 6839–6855 (2021).

Sakamoto, K. M., Laing, J. R., Stevens, R. G., Jaffe, D. A. & Pierce, J. R. The evolution of biomass-burning aerosol size distributions due to coagulation: dependence on fire and meteorological details and parameterization. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 7709–7724 (2016).

Huang, K. et al. Superposition of Gobi dust and southeast asian biomass burning: the effect of multisource long-range transport on aerosol optical properties and regional meteorology modification. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 124, 9464–9483 (2019).

Liu, H. et al. Size-resolved mixing state and optical properties of black carbon at an urban site in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 749, 141523 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Strong haze-black carbon-climate connections observed across Northern and Eastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 128, e2023JD038505 (2023).

Matsui, H. et al. Development and validation of a black carbon mixing state resolved three-dimensional model: aging processes and radiative impact. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 118, 2304–2326 (2013).

Riemer, N., West, M., Zaveri, R. A. & Easter, R. C. Simulating the evolution of soot mixing state with a particle-resolved aerosol model. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D09202 (2009).

Xu, L. et al. Tracing the evolution of morphology and mixing state of soot particles along with the movement of an Asian dust storm. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 14321–14332 (2020).

Flatau, P. J. & Draine, B. T. Fast near field calculations in the discrete dipole approximation for regular rectilinear grids. Opt. Express 20, 1247–1252 (2012).

Corral Arroyo, P. et al. Amplification of light within aerosol particles accelerates in-particle photochemistry. Science 376, 293–296 (2022).

Beeler, P. et al. Light absorption enhancement of black carbon in a pyrocumulonimbus cloud. Nat. Commun. 15, 6243 (2024).

Jacobson, M. Z. Effects of externally-through-internally-mixed soot inclusions within clouds and precipitation on global climate. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 6860–6873 (2006).

Li, K. et al. Significantly accelerated photochemical and photocatalytic reactions in microdroplets. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100917 (2022).

Kahnert, M., Nousiainen, T. & Lindqvist, H. Models for integrated and differential scattering optical properties of encapsulated light absorbing carbon aggregates. Opt. Express 21, 7974–7993 (2013).

Beeler, P. & Chakrabarty, R. K. Constraining the particle-scale diversity of black carbon light absorptionusing a unified framework. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 14825–14836 (2022).

Riemer, N. & Bond, T. C. Toward reduced representation of mixing state for simulating aerosol effects on climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, 971–980 (2017).

Matsui, H., Hamilton, D. S. & Mahowald, N. M. Black carbon radiative effects highly sensitive to emitted particle size when resolving mixing-state diversity. Nat. Commun. 9, 3446 (2018).

Wang, Z., Zhang, H., Li, J., Jing, X. & Lu, P. Radiative forcing and climate response due to the presence of black carbon in cloud droplets. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 118, 3662–3675 (2013).

Lauritsen, S. M. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence model to predict acute critical illness from electronic health records. Nat. Commun. 11, 3852 (2020).

Ching, J., Fast, J., West, M. & Riemer, N. Metrics to quantify the importance of mixing state for CCN activity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 7445–7458 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Fractal dimensions and mixing structures of soot particles during atmospheric processing. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 4, 487–493 (2017).

Abo Riziq, A., Erlick, C., Dinar, E. & Rudich, Y. Optical properties of absorbing and non-absorbing aerosols retrieved by cavity ring down (CRD) spectroscopy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 1523–1536 (2007).

Sihvola, A. & Sharma, R. Scattering corrections for Maxwell Garnett mixing rule. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 22, 229–231 (1999).

Bond, T. C. & Bergstrom, R. W. Light absorption by carbonaceous particles: an investigative review. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 40, 27–67 (2007).

Sorensen, C. M. & Fischbach, D. J. Patterns in Mie scattering. Opt. Commun. 173, 145–153 (2000).

Aas, K., Jullum, M. & Løland, A. Explaining individual predictions when features are dependent: more accurate approximations to Shapley values. Artif. Intell. 298, 103502 (2021).

Gliß, J. et al. AeroCom phase III multi-model evaluation of the aerosol life cycle and optical properties using ground- and space-based remote sensing as well as surface in situ observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 87–128 (2021).

Matsui, H. & Mahowald, N. Development of a global aerosol model using a two-dimensional sectional method: 2. Evaluation and sensitivity simulations. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 9, 1887–1920 (2017).

Matsui, H. et al. Contrasting source contributions of Arctic black carbon to atmospheric concentrations, deposition flux, and atmospheric and snow radiative effects. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 8989–9009 (2022).

Matsui, H. Development of a global aerosol model using a two-dimensional sectional method: 1. model design. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 9, 1921–1947 (2017).

van der Werf, G. R. et al. Global fire emissions estimates during 1997–2016. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 697–720 (2017).

Chen, X. Locating the missing absorption enhancement due to multi-core black carbon aerosols, Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28225802, 2025.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF0809402), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42075096), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024-00416902), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M770296), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LZJMZ25D050002, LQN25D050002). Joseph Ching was supported by the Dean’s Research Fund of the Faculty of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Projects No: FLASS/DRF 0401 A ICRS-1), and the Start-up Research Grant for Newly Recruited Academic Staff, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Projects No. RG45/2023-2024 R R4392). Yinon Rudich acknowledges support by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant #928/21). H.M. was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (MEXT/JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP20H00196, JP22H03722, JP23H00515, JP23H00523, JP23K18519, JP23K24976, and JP24H02225, the MEXT Arctic Challenge for Sustainability phase II (ArCS II; JPMXD1420318865) project, and by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund 2–2301 (JPMEERF20232001) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C. and W.L. conceived the overall idea and performed most of the analysis and model simulations; Z.Z., F.Z., Y.W., X.C., and W.L. drafted the paper; D.L., S.Z., Y.R., Z.S., H.Y., and K.J. edited the paper; X.C. and F.W. collected the samples; X.C., H.Y., and K.J. conducted single particle analysis; J.C., H.M., and M.J. conducted the simulations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Ching, J., Wu, F. et al. Locating the missing absorption enhancement due to multi‒core black carbon aerosols. Nat Commun 16, 10187 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65079-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65079-2

This article is cited by

-

Unveiling air toxicity in urban environment through morphology and chemical reactivity of aerosol: insights from Delhi, India

Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health (2026)