Abstract

Magnetic-free nonreciprocal optical devices that prevent backscattering of signals are essential for optical information processing. The achieved nonreciprocal behaviors mostly rely on various optical dispersive effects, leading to dispersive modulations of the spatial beam profiles, such as broadening and discretization, of incident signals. Such deformation inevitably reduces the matching with subsequent functional components. Here, we experimentally demonstrate the nonreciprocal transverse localization of light in a moiré photonic lattice in atomic vapors. When the probe field co- or counter-propagates with the forward coupling field with a honeycomb moiré profile, the output pattern can exhibit localized or dispersive behavior. The nonreciprocal behaviors (in both beam size and transmitted intensity) are from the atomic thermal motion. A backward Gaussian coupling field is also introduced to modulate the size and intensity of the backward probe, which experiences dispersive propagation. The current work provides an approach to control the transverse beam profile in nonreciprocal transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of integrated optical information processing techniques promotes the quest for magnetic-free nonreciprocal optical devices, which usually break the time-reversal symmetry to earn the desired capability in enforcing the unidirectional transmission of optical waves1,2,3,4,5. Up to now, the design of high-performance nonreciprocal optical functionalities has been realized with plenty of approaches without the presence of bulky magnets but bypassing Lorentz reciprocity, including valley polarization pumping6, optical nonlinearity7,8,9,10, Autler-Townes splitting11, Sagnac effect in resonators12,13, chiral light-matter interactions14,15, optically-induced magnetization16 and Brillouin scattering17, to name a few. In the meanwhile, optical nonreciprocity has also been proposed under the frame work of obeying time-reversal symmetry18,19. The implementations of magnet-free optical nonreciprocity, irrespective of satisfying time-reversal symmetry or not, mostly lie in homogeneous bulk media20,21, optical resonators15,22,23,24,25 and spatially discrete photonic structures26,27,28,29,30,31. In most adopted nonreciprocal optical platforms, the behaviors of light are essentially governed by the dispersion of optical media, which can give rise to dispersive modulations (such as spatial broadening and discretization) on the incident light, yet with high nonreciprocal contrast of transmitted intensities. Such deforming effects from nonreciprocal optical devices can reduce the matching between the signals and subsequent components for information processing and transmission.

In 2018, the concept of nonreciprocal localization of photons was proposed in a 1D moving photonic lattice with an embedded static defect32. Such a dynamical periodic configuration based on electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT)33 in an atomic system produces a localized state or scattering mode for photons traveling in opposite directions, leading to nonreciprocal transmission. Very recently, nonreciprocal 1D solitons were reported in a spinning Kerr resonator34 and in active metamaterials35. Optical solitons, resulting from the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity36, can also cancel the dispersive effects but with a threshold for the input power. This indicates that nonreciprocal solitons are applicable for situations involving relatively strong signals. However, no transverse effects were studied in these works. The transverse beam profile is important for beam matching between the nonreciprocal devices and follow-up optical components. Transverse localization could be promising in counteracting the dispersive propagating effects in magnetic-free nonreciprocal optical devices, but it has not been experimentally observed so far.

In this work, by combining the Doppler frequency shift from the thermal motion of atoms and flat bands from moiré structures, we demonstrate the nonreciprocal optical transverse localization in a honeycomb moiré photonic lattice optically induced in a three-level Rb atomic vapor cell. Actually, thermal atoms with Doppler effect, which can produce direction-dependent frequency shift on involved laser fields to destroy the EIT effect, have acted as a powerful platform in conducting nonreciprocal propagation of light37,38 in the longitudinal z direction. Also, the optical diode made from a 1D moving photonic lattice has been experimentally demonstrated in atomic vapors, where the motion of the lattice breaks the time-reversal symmetry39. However, the extra dispersive modulation in the forward case in the nonreciprocal systems relying on atomic vapors has always been inevitable. Here we establish a moiré photonic lattice40,41,42, which is characterized by flat bands with considerably suppressed transverse dispersion43,44,45,46, by coherently superposing two honeycomb photonic lattices with a twist angle of 27.8° in the x-y plane. The required honeycomb lattices are induced under the condition of EIT47,48,49,50 by two identical honeycomb coupling beams from a spatial light modulator (SLM). This experimentally verifies the formation of instantaneously reconfigurable moiré photonic lattices with the assistance of EIT, which has been exploited to theoretically design various moiré structures51,52. By selectively launching the probe beam in the same (forward case) or opposite (backward case) direction to the forward coupling field with the moiré profile, which produces EIT for the co-propagating probe but not for the counter-propagating one, the output can exhibit localized or dispersive feature. The imbalanced output probe intensities in the forward and backward cases are also achieved, since EIT can effectively suppress the resonant absorption, as in the non-Hermitian skin effect53,54,55,56,57. To optically control the nonreciprocal contrast in both the intensity and size between the two output probe beams, a backward Gaussian coupling field is introduced in the opposite direction of the moiré field to excite the backward EIT, which can effectively modify the transmissivity and width of the backward output probe exhibiting broadening. In principle, the behavior of the forward (backward) probe beam is governed by only the forward (backward) EIT, but is immune to the other. With two probe beams simultaneously injected into the moiré lattice in opposite directions, the obtained maximum isolation ratio is about 20.1 dB, and the nonreciprocal contrast of the beam size can be manipulated in the range of 2.79 to 4.25.

Results

Scheme of nonreciprocal transverse localization within a honeycomb moiré lattice

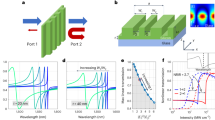

Figure 1a depicts the experimental principle. A forward coupling field Ec (frequency ωc) with a moiré intensity profile is established by superposing two identical honeycomb light beams generated from a phase-type SLM45,58. The twist angle θ between the two honeycomb substructures can be controlled by loading different desired holographs, which possess the phase information of the targeted moiré structure (the detailed experimental setup and holography are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1). A backward Gaussian coupling field Ec′ (ωc′) counter-propagates with Ec inside the atomic sample. Then the weak forward probe beam Ep (ωp) is focused onto one site of the moiré pattern at normal incidence, and a three-level Λ-type energy-level structure is established inside atomic vapors.

a Experimental scheme. A SLM is employed to modulate the vertically polarized forward coupling field Ec into a moiré pattern consisting of two honeycomb substructures. A backward coupling field Ec′ (vertical polarization, frequency ωc′ and wavevector kc′, from a different laser source with Ec) with a Gaussian profile counter-propagates with Ec (frequency ωc and wavevector kc). Two horizontally polarized probe beams Ep (forward case, frequency ωp and wavevector kp) and Ep′ (backward case) are sent into the Rb atomic vapor cell in opposite directions, and their output patterns passing through the atomic medium are imaged onto two cameras (CCD1 and CCD2). Δp, Δc and Δc′ are the frequency detunings of corresponding fields. HR: high reflective mirror, BS: beam splitter, CCD: charge-coupled device camera. b, c The Λ-type energy-level atomic configurations for forward and backward cases with Doppler effect considered.

The three-level atomic configuration for EIT contains two hyperfine ground states F=2 (level |1〉) and F=3 (|2〉) of 5S1/2 and an excited state 5P1/2 (|3〉), as given in Fig. 1b, c. The field Ep (Ec or Ec′) drives the transition from the ground state |1〉 (|2〉) to the excited state |3〉 with detuning Δp (Δc or Δc′), which is denoted by the difference between the probe (forward or backward coupling) frequency ωp (ωc or ωc′) and the natural frequency between the two energy levels it connects. For atomic vapors, the inevitable random thermal motion of atoms can bring Doppler frequency shift for incident laser fields33,37. The frequency shift is described by kiv, with ki being the wave vector of the corresponding beam and v being the velocity of the atoms moving towards the beam. The amplitude of kiv is positively related to the atomic temperature and usually of the order of hundreds of megahertz. In the forward case (Fig. 1b) of Ep co-propagating with forward Ec but traveling oppositely with backward Ec′, Δp, Δc and Δc′ become Δp+kpv, Δc+kcv and Δc′−kc′v, respectively. Considering the very minor difference in wavelengths of the probe and coupling beams, we have kp=kp′≈kc≈kc′ and the two-photon detunings interacting with the co- and counter-propagating coupling fields are (Δp+kpv)−(Δc+kcv)≈Δp−Δc and (Δp+kpv)−(Δc′−kc′v)≈Δp−Δc′+2kpv, respectively. As a result, the influence of Doppler frequency shift is canceled in the co-propagating case, which is also viewed as the Doppler-free situation that allows EIT, while Doppler shift destroys the two-photon resonant condition for EIT in the counter-propagating case33. This gives rise to the fact that the forward probe feels only the EIT (Δp−Δc=0) arising from the forward moiré coupling field, but fails to generate EIT with the backward Gaussian coupling field. Under the EIT condition, the output forward probe can exhibit varying transverse distributions and localization after passing through the moiré photonic lattices with different twist angles, when the two-photon detuning is set around Δp−Δc=0 for exciting the EIT effect. The transverse localization appears due to the peculiar profiles of potential and the band structures characterized by suppressed dispersions in moiré photonic structures42.

In contrast, in the backward case with probe field Ep′ (has the same parameters as Ep but is sent into the vapor cell oppositely) turned on, the two-photon detuning can be expressed as (Δp−kp′v)−(Δc+kcv)≈Δp−Δc−2kpv and (Δp−kp′v)−(Δc′−kc′v)≈Δp−Δc′, see Fig. 1c. Thus, the backward probe Ep′ experiences only the modulation of EIT (Δp−Δc′=0) arising from the backward coupling field. When the two-photon detuning Δp−Δc′ is set far away from the EIT window by changing Δc′, Ep′ behaves as the case without Ec′ and experiences a strong resonant absorption together with a usual beam broadening, resulting in a weak and broad Gaussian pattern after dispersive propagation. With the two-photon detuning approaching towards Δp−Δc′=0, the backward EIT effectively suppresses the resonant absorption of Ep′ and enhances its dispersion, leading to the modification on size of the backward Gaussian output. As a consequence, the output characteristics for the forward and backward probe beams are nonreciprocal in both intensity and transverse profile, see the upper two insets in Fig. 1a, and both nonreciprocal contrasts are controllable via the backward coupling-field detuning.

Nonreciprocal dynamics of the forward and backward signals

In the forward case, the moiré coupling field generates EIT effectively for the co-propagating forward probe. It experiences a spatial periodic susceptibility distribution inside the atomic vapors, but suffers negligible impact from the backward coupling field due to the strong Doppler effect. The resulted forward linear susceptibility with both coupling fields simultaneously present is described as33:

In the above expression, μmn and Γmn are the respective dipole moment and decay rate between states |m〉 and |n〉 (m, n=1, 2, 3); N is the atomic density; ε0 is the vacuum dielectric constant; Ωc(x, y)=μmnEc(x, y)/ħ and Ωc′(x, y)=μmnEc′(x, y)/ħ are the spatially distributed Rabi frequencies of the moiré (Ec) and Gaussian (Ec′) coupling fields, with Ec (Ec′) being the amplitude of the corresponding electric field; \({e}^{-{v}^{2}/{u}^{2}}/u\sqrt{\pi }\) is the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution of velocity, with u being the most probable velocity, and v being the atomic velocity.

According to Eq. (1), the simulated real parts of the susceptibility of the moiré photonic lattices obtained by superposing two honeycomb substructures with different twist angles θ are shown in Figs. 2a–d. When θ is 0, the susceptibility exhibits a honeycomb distribution. As θ increases to 16.4°, 27.8° and 54.0°, which are Pythagorean angles corresponding to the commensurate phases of moiré lattices41,59, the profiles of the susceptibility are clearly distinct from each other, but the translational symmetry is present in three cases with primitive cells of very different sizes, advocating the establishment of moiré photonic lattices. The imaginary susceptibilities are over 2 orders of magnitude smaller than the real parts (Supplementary Fig. 2), and can cause only a very weak absorption of the probe. It’s worth noting that the susceptibility profile felt by the forward probe is immune to the change of detuning Δc′. In principle, the formed moiré lattices at these three non-zero rotation angles remain periodic and all eigenmodes are expanding slightly over time. Nevertheless, it is enough to make the beam expansion suppressed on the scale of the established system.

a–d The real part of the susceptibility of moiré lattices with different twist angles of θ = 0, 16.4°, 27.8° and 54.0° in the forward case. The dash circles mark the injecting position of the probe beam. e–h Simulated output patterns of the forward probe. i, j The real part of the susceptibility and output pattern in the backward case with θ = 27.8° when the backward coupling detuning is Δc′ =−32 MHz. k, l are the same as i, j but with Δc′ = 60 MHz. The amplitudes of the Rabi frequency of the forward moiré and backward Gaussian coupling fields are 165 MHz and 190 MHz, respectively. Δc = 60 MHz and Δp = 68 MHz. The exhibited intensity (I0) of the output pattern in j is artificially enhanced 1022 times to improve its visibility, while the other images show the original intensities.

The propagation dynamics of the light inside the formed photonic lattices is checked by employing the Schrödinger-like paraxial equation50:

where ψ is the envelope of the incident probe field Ep; z is the propagation distance; k0=2πn0/λp and λp are the probe-field wavenumber and wavelength, respectively, with n0≈1 being the background refractive index; Δn≈χ/2 is the modulation of the refractive index arising from the coupling fields.

The simulated output patterns of a narrow Gaussian forward-propagating probe in the transverse x-y plane corresponding to different rotating θ of the forward coupling beams are given in Fig. 2e–h. The setting of θ=0 shows the expected honeycomb profile. The beam expansion is due to the evanescent coupling between neighboring waveguide channels, allowing a direct mapping to the honeycomb lattice of graphene. For the moiré lattices of θ≠0, only in the case of θ = 27.8° a localized wavepacket is clearly seen, while the other twist angles lead to expanding patterns, with intensity modulation corresponding to the profile of \({\mathrm{Re}}({\chi }_{f})\).

The susceptibility \({\chi }_{b}\) experienced by the backward probe modulated by two coupling fields has the same format as Eq. (1), but with the term kpv replaced by −kpv. Obviously, when the two-photon resonance Δp−Δc′=0 is satisfied, the term Δp−Δc+2kpv is hundreds of megahertz away from the resonance. As a result, the propagation of the backward probe is dominated by the EIT from backward Ec′. Figure 2i shows the simulated real part of \({\chi }_{b}\) in the backward case with θ=27.8° and Δp−Δc′ = 100 MHz. It possesses a uniform distribution and is independent on θ, since the Doppler frequency shift suppresses the interaction with the forward moiré coupling field Ec. Also, considering that detuning Δp−Δc′ is far away from the resonance, the imaginary part of \({\chi }_{b}\)(Supplementary Fig. 2) is about two orders of magnitude larger than that of the forward case, similar to the situation without Ec′. Therefore, the backward output based on Eq. (2) is much weaker, as simulated in Fig. 2j, where the exhibited intensity (I0) of the output pattern is artificially enhanced 1022 times to improve its visibility. Then Δc′ is increased to 60 MHz and Δp−Δc′ = 8 MHz (approaching the two-photon resonance), the modulation in both real and imaginary parts of \({\chi }_{b}\) from Ec′ is much stronger. The simulated \({\mathrm{Re}}({\chi }_{b})\) and corresponding backward output are shown in Fig. 2k, l. Please see more details on the evolutions of the susceptibility and transmission of the backward probe in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3. Compared to the localized state in Fig. 2g, the backward transmitted pattern in Fig. 2l is much broader and exhibits a comparable intensity. In this sense, the nonreciprocal behavior in the transverse profile occurs in the designed atomic system. Also, the nonreciprocal contrast in forward and backward transmission is optically controllable.

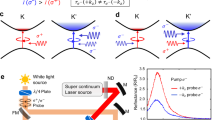

Mechanisms of the forward localization

In general, the dispersionless (flat) band in photonic moiré structures can lead to localization, but the factors that can produce localization in periodic photonic structures are often much more complicated and go far beyond the flat-band effect, considering the fact that the achieved flat bands in photonic lattices rarely exhibit absolutely zero dispersion. Figure 3a–d show the corresponding energy bands, obtained by Fourier-transforming the solution of Eq. (2) with a narrow Gaussian input. The Dirac cones, typical for the honeycomb lattices, can be seen in Fig. 3a with θ = 0. By increasing θ to 16.4°, 27.8° and 54.0°, the moiré lattices in Fig. 3b–d all demonstrate the formation of flat bands (the width of the narrowest band is δE = 6 J for a honeycomb lattice, δE ≈0.13 J in Fig. 3b, δE ≈0.4 J in Fig. 3c and δE ≈0.55 J in Fig. 3d) from the original s band of the honeycomb lattice. In principle, bands with low dispersion could effectively suppress the spreading of incident probe beams, if the beams were exciting only these flat bands. However, according to the simulations in Fig. 2e–h, only θ = 27.8° brings about a strong localization effect.

a–d The energy bands of the moiré photonic lattices with different twist angles. e–g The profiles of potential inside different lattices according to Fig. 2b–d. The red and blue vertical lines mark the deepest and the second deepest potentials, respectively. Ueff(y) is the effective potential, with U0 being peak potential of individual moiré lattice. According to Eq. (2), the potential of the lattice is −k0/n0×Δn(x, y)ψ, indicating that it has the same profile as the refractive index Δn(x, y), but with an opposite sign. y/a1 is the normalized coordinate with a1 being the minimum distance of two sites with the deepest potential in corresponding moiré lattices.

This unexpected result is understood by analyzing the profiles of potential inside different moiré cells, as given in Fig. 3e–g, rather than only the band structures. On the one hand, the simulated moiré bands are not completely flat and still exhibit slight non-zero dispersions, and the probe beam is exciting multiple bands, which will unavoidably lead to the broadening of beams. On the other hand, the moiré lattice obtained by interference of the coupling beams via EIT exhibits an important peculiarity: contrary to other moiré structures studied in electronics and photonics40, the sites of our lattices exhibit different potential depths. During the probe beam propagation, tunneling is only possible between sites (waveguide channels) which have a comparable depth of potential. Our probe beam is always focused on the site with the deepest potential (the largest susceptibility), see Fig. 2a–d. For θ = 27.8°, the potential of the second deepest site is only 79% of that in the deepest one. Whereas in θ=16.4° (θ=54.0°), the second deepest potential in the vicinity of the excited site is 91% (97%) of the deepest one, respectively. A smaller difference of the susceptibility between two sites makes tunneling much easier.

By analyzing the difference of the susceptibility between two adjacent sites, one can understand the output results in Fig. 2e–h of different moiré lattices much better. With θ = 16.4°, the probe beam is not fully localized and slightly couples into surrounding waveguides, due to the similar susceptibilities of the incident site and circumambient sites. The further enlargement of the difference in θ = 27.8° suppresses the coupling of the light between adjacent channels: the transverse localization occurs. A very minor portion of the probe expands outside the incident site. Compared to that in θ = 0 with large dispersion, the localization in θ = 27.8° improves the output peak intensity ten times. The transmitted pattern in θ = 54.0° exhibits the strongest broadening, because the involved sites have almost the same potential. It’s worth mentioning that the suppression of the broadening of wave packets from the formed flat bands in all cases is verified by the fact that the sizes of the output patterns in θ≠0 are smaller than in the case of θ=0 with dispersive bands. Therefore, moiré lattices can give rise to flat bands, but the slight deviations from flatness can induce minor dispersive behaviors. The degree of expansion of the incident light is then dependent on the potential difference between neighboring sites.

Observation of nonreciprocal transverse localization

Figure 4a–h show the experimentally established spatially periodic forward coupling field composed of two honeycomb substructures with different twist angles. As shown in Fig. 4a with θ = 0, the resulted compound pattern still shows a honeycomb distribution. The coupling fields with different moiré patterns by changing θ are presented in Fig. 4b–d, which support the predictions in Fig. 2b–d well. The waveguide channels are optically induced at the positions with the largest intensity of the structured coupling field.

a–d The obtained intensity patterns of moiré coupling field superposed of two honeycomb substructures with different twist angles of 0, 16.4°, 27.8° and 54.0°. The green circles indicate the incident position of the probe beam. e–h The corresponding output patterns of the forward probe beam. i–k The transmission of the backward probe beam with Δc′ increased from −32 MHz to 60 MHz at Δc = 68 MHz and twist angle θ = 27.8°. Since the backward output is too weak to observe, the gain g of the camera CCD2 was set as 15 dB for larger Δc′. To avoid the saturation of the CCD2 at smaller Δc′, g was then adjusted to 3 dB. In the forward case, g = 0 means no gain on CCD1. wb/wf represents the nonreciprocity between the backward and forward output beam sizes. l The dependence of the isolation ratio 10log10(Tf/Tb) on the input power P when both probe beams with the same parameters are present simultaneously but without backward coupling field (experimental measurements – circles). The curve is a guide to the eye.

When the forward probe beam is focused onto one site (marked by the green circle) of the moiré coupling field, the output patterns are obtained as Fig. 4e–h. Here the size of the probe wave packet at the input surface of the vapor cell is comparable to that of one lattice site. Figure 4e shows a clear honeycomb profile under the condition of θ = 0 and confirms the formation of a honeycomb photonic lattice inside the cell. By setting θ = 16.4°, the moiré pattern in Fig. 4b shows that the primitive cell contains several honeycomb units and is quite different from that at θ = 0. As a result, the output probe in Fig. 4f is broadened and demonstrates a modulation corresponding to the moiré lattice. With the angle further increased to θ = 27.8°, the output probe in Fig. 4g shows a narrow wave packet, whose size is close to that of the incident probe beam. This is the transverse localization caused by the suppressed band dispersion and the relatively large difference of potential between the incident and surrounding channels. For the result of Fig. 4h, the expansion of the probe beam is recovered and its output pattern shows a clear hexagonal modulation, agreeing well with the moiré pattern of θ = 54°. All the experimental observations coincide with the simulated Fig. 2e–h.

Figure 4i–k show the output patterns of the backward probe beam for θ = 27.8°, displaying broad Gaussian profiles due to the inherent dispersion. One can see that both the intensity and beam width of the backward output evolves obviously, with Δc′ discretely increased from −32 MHz to 60 MHz. At Δc′ =−32 MHz of Fig. 4i, the two-photon detuning Δp−Δc′ is 100 MHz away from the resonant condition and the backward coupling field can suppress little of the absorption. This is similar to the case without backward Ec′. Here the backward pattern does not exhibit obvious change with modifying θ, because the backward probe field is immune to the modulation of the forward EIT.

In Figs. 4j, k, as Δp−Δc′ gets closer to zero, both the intensity and diameter of the backward output increase gradually. On the one hand, moving closer to the two-photon resonance can result in a smaller \({\mbox{Im}}({\chi }_{b})\) (see Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating more reduction of the resonant absorption. Thus, with Δp−Δc′ = 8 MHz, Fig. 4k depicts that the backward output intensity ultimately becomes comparable to that of the forward output in Fig. 4g. On the other hand, the real part of \({\chi }_{b}\) could be larger near the resonance compared to that at far detuning, leading to more obvious dispersive effect and a broader profile. More backward transmitted patterns for varying Δc′ are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4b. In contrast, the variation of Δc′ imposes no obvious effect on the forward output, which maintains the localized state with strong transmission (see Supplementary Fig. 4a). These observations advocate the effect of nonreciprocal transverse localization with optical controllability. As a result, when both probe beams are oppositely but collinearly sent into the medium under θ=27.8°, we obtain that the nonreciprocal contrast wb/wf on the beam width ranges from 2.79 to 4.25 by setting Δp−Δc′ from 100 MHz to 8 MHz via easily changing Δc′. Here wb (wf) denotes the full width at half maximum of the backward (forward) output probe patterns.

In addition, we measure the isolation ratio of the formed system performing nonreciprocal transverse localization. When Δp−Δc′ is far from the resonance, the forward and backward outputs exhibit the maximum contrast in intensity. Considering the behavior of the backward probe under the far-detuning condition can be viewed as the case without the backward Ec′, we investigated the isolation ratio at different forward probe power P with the backward Ec blocked. Figure 4l shows the dependence of isolation ratio on the input power P when both probe beams present under θ=27.8°. The transmitted intensities of the forward and backward probe are defined as Tf and Tb, and the isolation ratio is obtained as 10log10(Tf/Tb). Here Tf and Tb are acquired by integrating the intensity in the capturing region of the cameras. The experimentally transmitted patterns of the forward and backward probe beams are shown in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6, respectively.

By increasing the probe power P from 80 μW to 240 μW, the isolation ratio grows from 13 dB to 20.1 dB. For the forward case with EIT, the enhancement of the input probe intensity can lead to a stronger Tf, since the absorptive coefficient is determined by the imaginary part of the susceptibility, which does not rely on the probe intensity according to Eq. (1). For the backward case, the probe beam experiences a very strong loss due to the relatively large atomic density and absence of EIT from the both coupling fields, and the transmission Tb approaches nearly 0. Even when the probe power is increased to 240 μW, the backward transmission is still very weak. This is probably due to the non-linear susceptibility (both real and imaginary), which is also different in the forward and backward cases. As a result, the isolation ratio can increase with the probe power. The measurement with two probe beams turned on together advocates that the demonstrated nonreciprocal localization can counteract dynamic reciprocity.

Discussion

In summary, by exploiting a SLM to build superposed patterns consisting of two honeycomb substructures, moiré photonic lattices under different twist angles are effectively established inside atomic vapors with the presence of EIT. Such moiré lattice is a monolayer structure obtained by interfering two involved sublattices, and is distinct from the moiré structure realized by twisted 2D materials41, which is bi-layered. In particular, the moiré photonic lattice with a selective twist angle can give rise to desired transverse localization for the probe beam. By jointly employing the intrinsic Doppler effect from thermal motion of atoms (which is usually considered to be detrimental in the formation of various coherent effects) and the established transverse localization, our work provides an effective route to realize nonreciprocal localization of photons with all-optical controllability of nonreciprocal contrasts in both intensity and transverse profile. What’s more, the isolation ratio of the current regime can be promisingly improved by introducing gain with an additional pump beam60,61. In addition, the current work develops an additional optical functionality with moiré photonic lattices and opens the door for engineering optical nonreciprocity in twistronics62. The nonreciprocal transverse localization that we have demonstrated can be used in magnetic-free nonreciprocal optical devices bypassing dispersive effects for the incident beams, and promisingly improving the matching between the output beams and subsequent optical components for signal processing, with such a wide range of applications as one-way optical imaging or sensing, directional optical communications, and nonreciprocal traps.

In principle, other schemes that can suppress the transverse dispersion can potentially be employed to realize such nonreciprocal transverse localization63. For example, light can be localized by exciting flat-band modes in Lieb or Kagome lattices, but their excitation requires a structured beam with well-designed phase difference64, instead of a Gaussian beam, which could overlap with dispersive subbands and lead to delocalization. In the perspective of applications, Gaussian profiles are the output of most laser sources and the common information carriers in optical information processing. Moiré lattices provide the capacity of localizing a Gaussian beam. Thus, the nonreciprocal localization formed with moiré lattices has the advantage of better universality in the design of nonreciprocal photonic devices that can suppress the dispersive effects.

Methods

Experimental settings

The probe beam and the backward coupling beam are from two different external-cavity diode lasers, while the forward coupling beam is derived from a semi-conductive tapered amplifier seeding with a beam from the third external-cavity diode laser. Both the wavelengths of the probe and coupling fields are ~795.0 nm, and their frequency difference is around 2π × 3.03 GHz. The frequency of the two coupling fields can be controlled separately by their own drivers. The forward coupling field with a moiré intensity pattern and backward coupling field with Gaussian profile have almost the same power of 40 mW. The adopted phase-type liquid crystal SLM has a resolution of 1920 × 1152. The Rb cell with a length of 5 cm is heated to 120 °C by a home-made temperature controller.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the Open Science Framework (OSF) database https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/V5EA965.

References

Jalas, D. et al. What is—and what is not—an optical isolator. Nat. Photonics 7, 579 (2013).

Lodahl, P. et al. Chiral quantum optics. Nature 541, 473 (2017).

Sohn, D. B., Kim, S. & Bahl, G. Time-reversal symmetry breaking with acoustic pumping of nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 12, 91 (2018).

Tang, L. et al. Quantum squeezing induced optical nonreciprocity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 083604 (2022).

Katsantonis, I. et al. Giant enhancement of nonreciprocity in gyrotropic heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 13, 21986 (2023).

Guddala, S. et al. All-optical nonreciprocity due to valley polarization pumping in transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 12, 3746 (2021).

White, A. D. et al. Integrated passive nonlinear optical isolators. Nat. Photonics 17, 143 (2023).

Yang, K. Y. et al. Inverse-designed non-reciprocal pulse router for chip-based LiDAR. Nat. Photonics 14, 369 (2020).

Xia, K., Nori, F. & Xiao, M. Cavity-free optical isolators and circulators using a chiral cross-Kerr nonlinearity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 203602 (2018).

Otterstrom, N. T. et al. Nonreciprocal frequency domain beam splitter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 253603 (2021).

Kittlaus, E. A. et al. Electrically driven acousto-optics and broadband non-reciprocity in silicon photonics. Nat. Photonics 15, 43 (2021).

Maayani, S. et al. Flying couplers above spinning resonators generate irreversible refraction. Nature 558, 569 (2018).

Huang, R., Miranowicz, A., Liao, J.-Q., Nori, F. & Jing, H. Nonreciprocal photon blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 153601 (2018).

Pucher, S., Liedl, C., Jin, S., Rauschenbeutel, A. & Schneeweiss, P. Atomic spin-controlled non-reciprocal Raman amplification of fibre-guided light. Nat. Photonics 16, 380 (2022).

Tang, J.-S. et al. Nonreciprocal single-photon band structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 203602 (2022).

Hu, X.-X. et al. Noiseless photonic non-reciprocity via optically-induced magnetization. Nat. Commun. 12, 2389 (2021).

Zeng, X. et al. Nonreciprocal vortex isolator via topology-selective stimulated Brillouin scattering. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq6064 (2022).

Buddhiraju, S., Song, A., Papadakis, G. T. & Fan, S. Nonreciprocal metamaterial obeying time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 257403 (2020).

Wanjura, C. C. et al. Quadrature nonreciprocity in bosonic networks without breaking time-reversal symmetry. Nat. Phys. 19, 1429 (2023).

Liang, C. et al. Collision-induced broadband optical nonreciprocity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 123901 (2020).

Lu, X., Cao, W., Yi, W., Shen, H. & Xiao, Y. Nonreciprocity and quantum correlations of light transport in hot atoms via reservoir engineering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 223603 (2021).

Shen, Z. et al. Reconfigurable optomechanical circulator and directional amplifier. Nat. Commun. 9, 1797 (2018).

Hua, S. et al. Demonstration of a chip-based optical isolator with parametric amplification. Nat. Commun. 7, 13657 (2016).

Zhu, G.-L. et al. Nonreciprocal superradiant phase transitions and multicriticality in a cavity QED system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 193602 (2024).

Shen, Z. et al. Nonreciprocal frequency conversion and mode routing in a microresonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 013601 (2023).

Söllner, I. et al. Deterministic photon–emitter coupling in chiral photonic circuits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 775 (2015).

Sounas, D. L. & Alù, A. Non-reciprocal photonics based on time modulation. Nat. Photonics 11, 774 (2017).

del Valle Inclan Redondo, Y. et al. Non-reciprocal band structures in an exciton–polariton Floquet optical lattice. Nat. Photonics 18, 548 (2024).

Chiacchio, E. I. R., Nunnenkamp, A. & Brunelli, M. Nonreciprocal dicke model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 113602 (2023).

Pinto-Ramos, D., Alfaro-Bittner, K., Clerc, M. & Rojas, R. Nonreciprocal coupling induced self-assembled localized structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 194102 (2021).

Lee, C. H., Li, L. & Gong, J. Hybrid higher-order skin-topological modes in nonreciprocal systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 016805 (2019).

Ramezani, H., Jha, P. K., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. Nonreciprocal localization of photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 043901 (2018).

Gea-Banacloche, J., Li, Y.-Q., Jin, S.-Z. & Xiao, M. Electromagnetically induced transparency in ladder-type inhomogeneously broadened media: Theory and experiment. Phys. Rev. A 51, 576 (1995).

Li, B. et al. Nonreciprocal optical solitons in a spinning Kerr resonator. Phys. Rev. A 103, 053522 (2021).

Veenstra, J. et al. Non-reciprocal topological solitons in active metamaterials. Nature 627, 528 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Observation of edge solitons in photonic graphene. Nat. Commun. 11, 1902 (2020).

Zhang, S. et al. Thermal-motion-induced non-reciprocal quantum optical system. Nat. Photonics 12, 744 (2018).

Dong, M.-X. et al. All-optical reversible single-photon isolation at room temperature. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe8924 (2021).

Wang, D.-W. et al. Optical diode made from a moving photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 093901 (2013).

Du, L. et al. Moiré photonics and optoelectronics. Science 379, eadg0014 (2023).

Oudich, M., Kong, X., Zhang, T., Qiu, C. & Jing, Y. Engineered moiré photonic and phononic superlattices. Nat. Mater. 23, 1169 (2024).

Xu, G. et al. Hydrodynamic moiré superlattice. Science 386, 1377 (2024).

Wang, P. et al. Localization and delocalization of light in photonic moiré lattices. Nature 577, 42 (2020).

Fu, Q. et al. Optical soliton formation controlled by angle twisting in photonic moiré lattices. Nat. Photonics 14, 663 (2020).

Wang, P., Fu, Q., Konotop, V. V., Kartashov, Y. V. & Ye, F. Observation of localization of light in linear photonic quasicrystals with diverse rotational symmetries. Nat. Photonics 18, 224 (2024).

Meng, Z. et al. Atomic Bose–Einstein condensate in twisted-bilayer optical lattices. Nature 615, 231 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Particlelike behavior of topological defects in linear wave packets in photonic graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 233905 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Angular-dependent Klein tunneling in photonic graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 233901 (2022).

Feng, Y. et al. Loss Difference Induced Localization in a Non-Hermitian Honeycomb Photonic Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 013802 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Non-hermitian delocalization in a two-dimensional photonic quasicrystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 263801 (2024).

Tian, R. et al. Localization-delocalization transition in an electromagnetically induced photonic lattice. Phys. Rev. A 108, 043711 (2023).

Chen, Z., Liu, X. & Zeng, J. Electromagnetically induced moiré optical lattices in a coherent atomic gas. Front. Phys. 17, 42508 (2022).

Yao, S. & Wang, Z. Edge states and topological invariants of non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086803 (2018).

Weidemann, S. et al. Topological funneling of light. Science 368, 311 (2020).

Torres, L. E. F. Perspective on topological states of non-Hermitian lattices. J. Phys. Mater. 3, 014002 (2019).

Martinez Alvarez, V., Barrios Vargas, J. & Foa Torres, L. Non-Hermitian robust edge states in one dimension: Anomalous localization and eigenspace condensation at exceptional points. Phys. Rev. B 97, 121401 (2018).

Torres L. E. & Roche S. A. non-Hermitian loop for a quantum measurement. arXiv:2408.04629 (2024).

Chen, Y.-F. et al. Generation of optical crystals and quasicrystal beams: Kaleidoscopic patterns and phase singularity. Phys. Rev. A 83, 053813 (2011).

Gao, Z., Xu, Z., Yang, Z. & Ye, F. Pythagoras superposition principle for localized eigenstates of two-dimensional moiré lattices. Phys. Rev. A 108, 013513 (2023).

Lin, G. et al. Nonreciprocal amplification with four-level hot atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 033902 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Observation of parity-time symmetry in optically induced atomic lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 123601 (2016).

Orazbay, M. & Valagiannopoulos, C. Twistronics-based polarization engineering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 054028 (2024).

Koutserimpas, T. T. & Valagiannopoulos, C. Multiharmonic resonances of coupled time-modulated resistive metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 064072 (2023).

Xia, S. et al. Demonstration of flat-band image transmission in optically induced Lieb photonic lattices. Opt. Lett. 41, 1435 (2016).

Liang, S. et al. Figure and data of ‘Observation of nonreciprocal transverse localization of light’. Open Science Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/V5EA9 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program (No. 2024YFE0102400, H. J.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62475209, Z. Z., No.11935006, H. J., and No.12421005, H. J.), the Hunan Major Sci-Tech Program (No. 2023ZJ1010, H. J.), Qinchuangyuan “Scientist+Engineer” Team Construction of Shaanxi Province (2024QCY-KXJ-178, Z. Z.) and by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program, through a FET Open research and innovation action under the grant agreements No. 964770 (TopoLight, D. S., G. M.). Additional support was provided by the ANR Labex GaNext (ANR-11-LABX-0014, D. S., G. M.), the ANR program “Investissements d’Avenir” through the IDEX-ISITE initiative 16-IDEX-0001 (CAP 20-25, D. S., G. M.), the ANR project MoirePlusPlus (ANR-23-CE09-0033, D. S., G. M.) and the ANR project “NEWAVE” (ANR-21-CE24-0019, D. S., G. M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. Z. conceived the original idea and supervised the project. D. S. and H. J. co-supervised the project. S. L. and C. C. L. conducted the experiment with the help from Z. Z. and Y. Z. S. L., C. C. L., Z. L., W. Y., G. M. and D. S. provided the theoretical support. D. S., H. J., G. M., C. B. L., Y. Z. and Z. Z. contributed to interpretation of experimental results. Z. Z., D. S. and S. L. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Fangwei Ye and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, S., Li, C., Liu, Z. et al. Observation of nonreciprocal transverse localization of light. Nat Commun 16, 10248 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65084-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65084-5