Abstract

Recently developed scissile mechanochemical probes provide powerful tools for direct visualization of the stress and damage behaviors of polymeric materials. However, simultaneous mapping of both stress and damage fields using a single mechanophore remains challenging. While widely used reversible ring-opening mechanophores (e.g., spiropyran and rhodamine derivatives) effectively report stress levels, they poorly correlate with microscopic damage evolution. In this study, we demonstrate that rhodamine-based mechanophores embedded in multiple network elastomers can simultaneously map both stress distribution and network damage. Although initial loading-induced damage does not immediately alter fluorescence responses, accumulated damage manifests as delayed activation and diminished intensity upon reloading to the same strain. During deformation, mechanophores undergo ring-opening, generating fluorescence, while the crosslinked network sustains progressive damage. While ruptured chains contribute to fluorescence during the initial cycle, their mechanophores remain inactive upon reloading. Consequently, comparative fluorescence analysis across cyclic loading enables simultaneous stress mapping in the first cycle and damage quantification through the difference between cycles. Building on this mechanism, we develop a mechanochemical damage model that accurately captures both stress-strain behavior and fluorescence evolution under diverse loading conditions. By integrating experiments and simulations, we achieve stress and damage visualization in tough elastomers under both homogeneous and inhomogeneous deformations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given the promising applications of soft materials in flexible electronics1,2, soft robotics3,4,5, and tissue engineering6,7,8, the development of soft materials with high strength and toughness has attracted broad research interest in the past two decades. Though different strategies have been employed to obtain tough elastomers and gels9,10,11,12,13, incorporating energy dissipation into interpenetrating networks has proven to be one of the most successful methods. The synthesis of tough and highly stretchable multiple network elastomers14 or hydrogels15 is achieved by incorporating highly crosslinked short-chain networks, serving as the first network, into a loosely crosslinked long-chain matrix. These interpenetrating network-based materials demonstrate superior mechanical properties compared to their single-network counterparts. The superior mechanical performance stems from energy dissipation through sacrificial bond rupture in the first network, while the primary network maintains structural integrity to prevent catastrophic failure16,17. Crucially, the damage inevitably induces a decrease in stress level in cyclic loading, known as the Mullins effect18,19,20,21,22, which also widely exists in filled rubbers and biological tissues23,24. Therefore, quantitative characterization of damage evolution and stress response is crucial for both failure prediction in engineering applications and the rational design of advanced soft materials. A fundamental challenge lies in acquiring molecular-scale information during mechanical loading, which cannot be directly provided by conventional testing methods.

Mechanochemically responsive polymers offer a promising solution for the above challenge by incorporating force-sensitive molecular units (mechanophores) into polymer25,26,27,28. Non-covalent mechanophores, such as hydrogen-bonded or π–π stacked motifs, enable reversible force-responsive behavior with relatively low activation thresholds29,30,31. While these systems are suitable for real-time visualization of mechanical deformation, they typically do not report irreversible molecular damage. On the other hand, covalent mechanophores are able to induce ring-opening isomerization or cleavage of structurally unstable covalent bonds with a critical force, thereby enabling force-induced color changes32, fluorescence33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 or luminescence phenomena14,22,42. By measuring these optical signals, microscopic information on the deformation and damage of polymer networks can be effectively obtained. For instance, a mechanosensitive small molecule known as bis-adamantyl dioxetane was developed, which undergoes scission into two parts under applied force, concomitant with the emission of blue luminescence42. Through incorporation of these mechanophores into multiple network system, the damage behaviors at the crack tip of the elastomer were successfully visualized under deformation, by analyzing optical signals14. Furthermore, quantitative analysis of deformation and light intensity revealed that the toughening mechanism of the multiple network elastomers originates from the rupture of sacrificial bonds, shedding light on the underlying principles of energy dissipation in these materials. Based on the mechanisms revealed by the experiments, several statistical and continuum models43,44,45 have been developed by incorporating progressive damage of networks into theories, which are capable of comprehensively predicting the mechanical responses of multiple network elastomers with different pre-stretching ratios and describing the Mullins effect resulting from damage. It is worth noting that scissile mechanophores are typically designed to report on damage of covalent bonds and should therefore have a scission force lower but as close as possible as that of C-C bonds14. Thus, they would only be able to report on very high stresses making them rather useless for mapping stress.

In contrast, ring-opening mechanophores like spiropyran33,34,35,46 and rhodamine36,37,38,39,47 show promise for highly sensitive stress mapping. In their pioneering work, Moore et al33. successfully integrated spiropyran into glassy polymer networks, achieving mechanochromism, and Silberstein et al48. demonstrated that the fluorescence was dependent on loading rate, deformation modes, and temperature. To develop mechanophores with lower critical ring-opening forces, a range of spiropyran derivatives have been synthesized46,49, which were then integrated into various material systems, such as, polydimethylsiloxanes (PDMS) and polyacrylates34,35,50,51,52. Notably, Chen et al50. correlated spiropyran’s chromatic response with stress in multiple network elastomers, enabling stress field mapping. In a following work, Chen et al52. found a slight decrease in the level of activation during the second loading cycle for a silica-filled elastomer nanocomposite in homogeneous loading condition, indicating the damage may affect the activation of mechanophores in the reloading process. Rhodamine-based mechanophores were also employed in glassy polymers36, multiple network elastomers and hydrogels37,38,39, leading to more sensitive fluorescence responses and smaller activation strains. While previous work has focused on expanding material compatibility and optimizing mechanophore sensitivity, a critical gap remains: these optical signals reflect stress-activated mechanophore responses but provide no direct information about material damage. The main reason is the absence of a direct correlation between the optical signals and the microscopic molecular chain scissions, which are instead interrelated in a coupled manner. Consequently, the utilization of stress sensitive mechanophores with ring-opening reactions to map the microscopic damage in polymers remains largely unexplored. In this work, we successfully address this challenge by employing rhodamine-based mechanofluorescent multiple network elastomers to decouple network damage from force-induced fluorescence responses. Through combined experimental and theoretical approaches, we fully demonstrate the possibility to simultaneously map both stress and damage fields via a single mechanophore.

Results

Preparation of mechanofluorescent multiple network elastomers

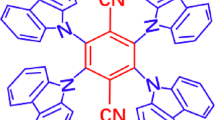

We synthesized mechanofluorescent multiple network elastomers using a multi-step photopolymerization process as detailed in previous works22,39 and Section S1 in Supplementary Information. Briefly, the first network was formed by photopolymerizing a precursor solution containing ethyl acrylate (EA) monomers, rhodamine-based mechanophores as cross-linkers (the detailed synthesis and characterization presented in Supplementary Figs. 1–4), and 2-hydroxy-4’-(2-hydroxyethoxy)−2-methylpropiophenone (I2959) photoinitiators.

After drying, this first network was then immersed in a solution of EA monomers, 1,4-butanediol diacrylate (BDA) cross-linkers, and I2959 initiators, allowing it to swell. This swollen network was subsequently exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light to induce further polymerization, forming a loosely cross-linked matrix network. The swelling and photopolymerization steps were repeated to integrate additional matrix layers into the first network, resulting in the formation of double network (DN) and triple network (TN) elastomers as shown in Fig. 1A. Owing to the swelling process in the synthesis of multiple network system, the first network undergoes varying degrees of pre-stretching. A summary of materials composition is presented in Supplementary Tab. 1. With the increase in matrix networks, the pre-stretching value of the first network also increases, which in turn leads to complex nonlinear mechanical behaviors of elastomers (Supplementary Fig. 6).

A Synthetic scheme of the multiple network elastomer with rhodamine mechanophores. The blue, green and yellow balls in the precursor solution represent monomers (ethyl acrylate), UV initiators and rhodamine mechanophores, respectively. B Scheme of fluorescence and damage evolution for elastomers under different conditions including loading, relaxation, unloading and reloading. The yellow and purple balls represent deactivated and activated mechanophores, respectively. The mechanophore is hexa-functional, so each mechanophore links six chains in three-dimensional space. However, for visual clarity in this 2D illustration, only four chains are shown, with the remaining two chains presumed to extend out of the plane. The Figure was created by Figdraw.com.

Mechanical and fluorescent properties

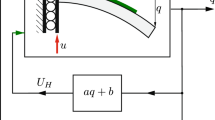

Under mechanical load, mechanochemically responsive elastomers exhibit fluorescence upon ultraviolet excitation. To simultaneously characterize the mechanical deformation and optical response, we developed an in-situ tensile testing system coupled with fluorescence detection (Supplementary Fig. 8). The emitted fluorescence signals were captured by an industrial RGB camera (FLIR BFS-U3-123S6C-C, 12-bit depth). The typical fluorescence response assessment encompasses techniques such as RGB analysis and intensity-based analysis by analyzing the fluorescent images34,35,48,50. In the RGB analysis method, images are separated into red, green, and blue channels, and the grayscale value per pixel within the regions of interest can be calculated. Chromaticity changes can be then obtained (Eq. S1). On the other hand, intensity analysis focuses on measuring light intensity within a specific wavelength range (590-620 nm), as identified by the fluorescence spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 7). Besides, the thickness correction procedure of intensity analysis method is also included (Supplementary Figs. 9-10). Our comparative study (Section S3.1) reveals that under small to moderate strains, both methodologies demonstrate equivalence in characterizing the fluorescence phenomena (Supplementary Figs. 12–14). However, RGB analysis reaches a saturation point during substantial deformations, limiting its effectiveness in capturing the mechanochemical response for elastomers in the large deformation regime. In contrast, intensity analysis maintains its sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 15), allowing for accurate tracking of fluorescence changes even under large deformation. Therefore, while both methods are adequate for moderate fluorescence responses, intensity analysis is more reliable in cases of large strain responses, as the material system investigated here. Given the high sensitivity of rhodamine-based mechanophores, we have adopted intensity analysis to quantify the fluorescence.

We systematically investigated the mechanical and mechanochemical behaviors of both DN and TN elastomers. Our results demonstrate that DN elastomers exhibit only limited damage (Supplementary Fig. 5C), accompanied by significantly weaker fluorescence signals compared to TN elastomers (Supplementary Fig. 11). Consequently, TN elastomers were selected as the primary material system for further study. Figure 2A-B illustrates the stress and corresponding fluorescence responses of the same TN elastomer specimens during three cyclic loading experiments, each with a maximum stretch of 2. Since the fluorescence response needs to be characterized in each cycle, the specimens have to fade completely before resetting for next tests. Previous experiments37,38,39 have shown that both heating and resting at room temperature for several hours are effective methods to revert the ring-opening mechanophores back to ring-closed state. Our control experiments (Supplementary Figs. 12A, B, 12D, E) also demonstrate that limited difference has been observed for the mechanical and chemical properties of the specimens adopting both methods. In order to accelerate the experimental process, before each subsequent loading cycle, the specimen was heat-treated to ensure complete fading of fluorescence. In the first loading cycle (Fig. 2A, B), there is little to no change in fluorescence intensity at low stress levels, as the stress is insufficient to activate the mechanophores. However, once the stretch exceeds 1.4, the fluorescence intensity increases rapidly, indicating that rhodamine mechanophores are continuously activated as the stress rises. After unloading and fading, the response during the second loading cycle differs significantly. The specimen exhibits a clear stress-softening behavior, where the stress level during reloading is lower than that of the virgin material until the deformation exceeds the previous maximum level, namely, the Mullins effect. The critical stretch for fluorescence activation increases to λ = 1.8. Despite the presence of strain hardening, the maximum fluorescence intensity in this cycle is lower than that in the first cycle at the same stretch of 2.0. We also plot the fluorescence intensity as a function of nominal stress as shown in Fig. 2C. In addition to stretch level, the critical activation stress also exhibits a delayed trend, which means that the mechanophores become more difficult to activate. These differences suggest that the accumulated damage from the first cycle affects the subsequent responses. To explore this further, we conducted a third uniaxial tension test. The mechanical and fluorescence responses in the second and third cycles are consistent, confirming that damage to the first network is mainly caused by the first loading process.

A Stress-response of uniaxial tension at a stretch rate of 0.05 /s and B the fluorescence intensity as a function of stretch for TN elastomers from the three cyclic loading tests with the maximum stretch 2.0. C The fluorescence intensity as a function of nominal stress in cyclic tests. D Stress-strain curves from three-step cyclic loading tests at a stretch rate of 0.05 /s and E the related fluorescence responses with the maximum stretches 1.75, 2.0, and 2.25, respectively. F The fluorescence intensity as a function of nominal stress in stepwise cyclic tests. Scale bars, 5 mm. The shaded area represents the range of experimental data obtained.

More directly, Supplementary Fig. 14 presents the fluorescence images during three consecutive cyclic tests at varying stretch levels. It is evident that the fluorescence intensity is highest and activated at the earliest stage during the first loading cycle (Supplementary Fig. 14A), whereas in the second cycle, the intensity is significantly weaker and the critical deformation required for activation is larger (Supplementary Fig. 14B). These observations directly demonstrate the influence of damage on the fluorescence response. In contrast, the fluorescence images from the second (Supplementary Fig. 14B) and third cycles (Supplementary Fig. 14C) appear nearly identical, suggesting that limited damage occurs in the second loading cycle. The scheme of fluorescence and damage evolutions for mechanofluorescent elastomers is shown in Fig. 1B. In the loading process from I to II, a portion of the chains with activated mechanophore crosslinkers is broken. During this period, the aforementioned portion of mechanophores still exhibits a fluorescence response due to a relatively long period needed for the ring-closing process. However, during the reloading process from IV to III, these mechanophores no longer provide any optical signals due to the permanent damage of the networks, resulting in no force applied on these mechanophores. Thus, the network damage represents irreversible backbone scission, which might exclude a specific population of mechanophores from being activated.

Therefore, comparing the fluorescence intensities between the first and second cycles can reveal the extent damage of networks in the first loading process, while the fluorescence intensity itself does not provide such information. To investigate the damage behaviors in soft materials, both cyclic and stepwise loading tests are widely used. Figure 2D–E presents the mechanical and mechanochemical responses during a three-step cyclic loading test, with maximum stretch values of 1.75, 2.0, and 2.25. As the maximum stretch increases, the hysteresis loop—defined by the area between the loading and reloading curves—becomes larger, indicating that larger deformation leads to a more pronounced Mullins effect. While these mechanical results are consistent with previous cyclic loading observations, the mechanochemical responses reveal more insights. Specifically, when each new loading exceeds the prior maximum stretch, both the critical stretch and the corresponding stress required to activate fluorescence increase (Fig. 2F). This behavior suggests that damage is induced once the deformation surpasses the previous maximum, and that the accumulation of damage reduces the number of mechanophores available for ring-opening activation.

To further explore the intricate coupled relationship between fluorescence changes and elastomeric damage, we conducted a subsequent stress relaxation experiment. Figure 3A plots the stress (blue lines) and fluorescence (red circles) responses over time during the first stress relaxation test, which was conducted at a maximum stretch of 2.1 preceded by an initial loading stretch rate of 0.05 /s. The fluorescence behavior observed during the loading process aligns with previous results. At the onset of relaxation, the fluorescence intensity shows a slight increase, attributed to the time-dependent fluorescence response of the mechanophore (Supplementary Fig. 17). Similar to the loading process, the activation of mechanophores still surpasses the ring-closing process at the onset of relaxation. As the stress rapidly decreases, a significant drop in fluorescence intensity follows. Once the stress reaches a plateau after an extended relaxation period, the fluorescence intensity stabilizes. After unloading, there was a residual deformation as shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, which is caused by the viscoelastic deformation. The residual deformation disappeared after applying heat or leaving the sample at room temperature for 4 hours, which also caused a complete fading of the fluorescence. The specimen was then subjected to a second stress relaxation test, and the stress and fluorescent responses as a function of time are shown in Fig. 3B. The stress still slightly decreases with time and reaches a plateau due to viscoelasticity. One notes that the fluorescence activation is delayed, and the peak intensity is lower than in the initial test. Interestingly, the peak intensity in the second test matches the stable intensity observed after the long relaxation period in the first test (Supplementary Fig. 19). This suggests that the reduction in fluorescence in the first relaxation process is due to damaged chains. Though the fluorescence intensity also has a decreasing trend in the second relaxation process, the decrease in the fluorescence is limited compared with the first relaxation test. This indicates that minimum damage occurred in the second loading test53.

A Stress (blue lines) and fluorescence (red circles) values over time during the first stress relaxation test at a fixed maximum stretch of λ = 2.1 preceded by an initial loading at a stretch rate of 0.05 /s and B results from the second stress relaxation test. C Comparison of normalized fluorescence intensity for a TN elastomer under various loading conditions. D Normalized fluorescence intensity as a function of wavelength at different relaxation times during the first test. Fluorescence data in (A) and (B) were obtained from images captured by a camera, while emission spectra in (C) and (D) were recorded using a fluorescence spectrophotometer.

As shown in Fig. 1B, in the relaxation process from Ⅱ to Ⅲ, some ring-opening mechanophores associated with these damaged chains revert to a closed state during relaxation and thus fail to reopen in the subsequent test (in the reloading process from Ⅳ to Ⅲ). Furthermore, we performed quantitative fitting of both fluorescence relaxation profiles (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 20B) using a standard exponential decay function (Supplementary Fig. 21). The fitting results indicate that the fluorescence relaxation time in the stress-relaxation experiment (Fig. 3A) is approximately 945 s, while the corresponding relaxation time under force-free condition (Supplementary Fig. 20) is about 1504 s. These results confirm that both processes occur on a comparable timescale of roughly a thousand seconds. It possibly reveals that the decrease in fluorescence in Fig. 3A is caused by ring-closure of the inactive mechanophores. Similar results were observed in a stress relaxation experiment conducted at a slower loading stretch rate of 0.001 /s (Supplementary Fig. 19), further supporting this assumption. To provide additional evidence, we used a fluorescence spectrometer (RF-6000) to record emission spectra under various conditions. As depicted in Fig. 3C, when the TN elastomer film was first stretched to a ratio of 2.0, a prominent fluorescence band appeared at 610 nm, accompanied by a strong red emission. After a prolonged relaxation period (Fig. 3D), the fluorescence spectrum exhibited a blue shift of approximately 10 nm and a significant decrease in intensity. Following unloading and fading, the same specimen was re-stretched to λ = 2.0, revealing a band at approximately 610 nm, albeit with reduced intensity. Notably, the intensities were consistent under both post-relaxation and second loading conditions. In summary, regardless of using a fluorescence spectrometer or intensity analysis from images, both methods confirm the validity of our hypothesis.

On the basis of the experimental outcomes, we propose a scheme of the fluorescence and damage evolutions under different conditions as shown in Fig. 1B. During the initial loading process (from I to II), the fluorescence response is generated by ring-opening mechanophores linked into two distinct types of chains within the first network. One set of responses originates from undamaged chains, while the other set is derived from damaged ones. It is widely accepted that some crosslinkers attached to shorter chains within the first network, designated as sacrificial chains, are prone to fracture upon a certain level of deformation14,43,44. The ring-opening reaction occurs prior to chain fracture. Consequently, a subset of damaged chains still retains the capacity to provide a fluorescence response. Subsequently, during the stress relaxation test (from Ⅱ to Ⅲ), the corresponding activated mechanophores undergo a gradual ring-closing reaction. As the stress reaches a plateau, all the initially ring-opened mechanophores associated with damaged chains have transformed into a ring-closed state. As a result, after an extended relaxation period at fixed macroscopic strain, only the ring-opening mechanophores linked to undamaged chains still exhibit fluorescence responses. Ultimately, the specimen is reloaded (from Ⅳ to Ⅲ) following unloading and fading. At this point, the entire fluorescence response derives from the activated mechanophores on the undamaged chains, while the inactive mechanophores no longer contribute. Consequently, the fluorescence intensity precisely matches the value observed in the relaxed state. This further suggests that the fluorescence intensity in the initial loading process reflect the concentration of mechanophores undergoing a ring-opening reaction but not directly related to the damage of networks.

Stress and damage mapping in elastomers

Above, we successfully decoupled the relationship between the fluorescent responses and the microscale damage behaviors using rhodamine-based mechanophores as probes. Based on these experimental findings, we conclude that during the initial loading, the molecular damage to the network has negligible impact on the fluorescent response. This is because the ring-closing process takes a period of around 1000 s while the loading process is only around 20 s. Thus, fluorescence intensity can be employed to map the stress. Importantly, for the initial fluorescence-stress curve, reliable stress mapping is only possible during the first loading cycle because the relation is affected by the extent of damage (Fig. 2F). Besides, accumulated damage would increase the critical activation stress for fluorescence in subsequent uniaxial loading processes, thereby reducing the overall fluorescence value, which can be further employed to estimate the damage level. By integrating these mechanisms with the mechanical theory of multiple network elastomers and the chemical kinetics theory of mechanophores54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64, we first develop a mechanochemical model, which will be employed to verify the stress and damage mapping in inhomogeneous deformation conditions.

The detailed processes for constructing the model can be found in Method, and Section S4 in Supplementary Information. The model contains both mechanisms of progressive damage of the first network and dynamic activation of mechanophores, resulting in the ability to capture the Mullins effect in the stress response and the fluorescence responses in cyclic loading conditions. The model parameters have been obtained by fitting to the uniaxial stress-stretch and fluorescence-stretch data. Figure 4A–B further compares the experimental results and the corresponding model simulations for the mechanical and fluorescent responses of the TN elastomers during cyclic tests. The model reproduces key features of the material behavior, including stress softening and the increase in the critical stretch for mechanophore activation due to accumulated damage. Additionally, we plotted the nominal stress-fluorescence intensity correlation obtained from simulation and experiment (Supplementary Fig. 22). It shows that damage leads to an increase in the critical activation stress of mechanophores. It is noted that the model slightly underestimates the critical stress, causing premature fluorescence activation in simulations compared to experiments.

. A Comparison between the experimentally measured and theoretically predicted stress responses and B the corresponding fluorescence responses for TN elastomers in cyclic tests. C The stress-strain responses of uniaxial cyclic tests for four TN samples with maximum stretch ratios of 1.75, 1.88, 2.05, and 2.22, respectively. D The energy dissipation, decreased intensity, and simulated damage percentage as functions of the stretch ratio for TN samples. Data are presented as mean values +/− SD (n ≥ 3).

We further try to quantify the relationship between the damage level and decreased fluorescence intensity based on both experiments and simulations. In the experiment, we prepared four TN samples, subjected to uniaxial cyclic tensions. The stress-strain responses of these samples are shown in Fig. 4C, with maximum stretch ratios of 1.75, 1.88, 2.05, and 2.22, respectively. An increase in maximum stretch ratios leads to a larger hysteresis loop, namely more energy dissipation. Fluorescence intensity measurements were employed as another metric for damage assessment. Specifically, the peak fluorescence intensities for all samples from both cycles were recorded, and the difference was calculated as a measure of decreased intensity, thereby reflecting the extent of damage incurred. Theoretically, a damage percentage for the first network can be defined, which serves as a predictor of material degradation under deformation (details available in Section S4 of the Supplementary Information). Figure 4D plots the energy dissipation, decreased intensity, and predicted damage level as functions of stretch ratio for TN samples. A good correlation between these variables is observed. This suggests that in addition to energy dissipation, the difference in fluorescence intensity between subsequent cycles can be effectively used to quantitatively describe microscopic chain damage levels. It should be noted that energy dissipation cannot be used to quantify the damage level under inhomogeneous deformation conditions. In contrast, spatially resolved fluorescence signals offer a promising alternative for assessing damage in such complex deformation scenarios as shown below.

We conducted cyclic tests using a TN elastomer specimen with a pre-punched hole (the geometric dimensions shown in Supplementary Fig. 5) and recorded the corresponding fluorescence response images. From the distribution maps of fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5A), it can be seen that stress concentration is localized around both sides of the hole during deformation, since the fluorescence intensity is positively correlated with the stress magnitude50. The areas closer to the hole exhibit a larger fluorescence intensity, which is consistent with classical stress concentration theory. In addition, since the geometric dimensions and boundary conditions of the specimen are symmetrical, the fluorescence response of the specimen is also symmetric about the horizontal and vertical axes. The distribution of fluorescence intensity magnitudes in the second cycle is significantly different from that in the first cycle. For example, at nearly the same stretch conditions and the same nominal stress condition (compare map iv and map vi), the overall distribution of fluorescence intensity in map vi is much weaker than in map iv. These findings are consistent with previous experimental results, since the accumulated damage makes the subsequent activation of mechanophores more difficult.

A Fluorescence maps for the elastomer with a circular hole. The black line and blue line represent the stress-strain curves from the first and second uniaxial tension tests at a stretch rate of 0.05 /s. The fluorescence maps (i to iv) correspond to different stretch levels from the first test, while maps (v to vi) are from the second test. B Comparison of simulated and measured distributions of normalized fluorescence intensity for two cycles with a stretch of 2.35. C Comparison of experimental stress maps and simulated ones for TN with a circular hole at different stretch ratios. It is noted that the experimental stress is mapped from the fluorescence in (A) during the first cycle. D Comparison between simulated distribution of damage percentage and experimental distribution of normalized decreased intensity for TN with a stretch of 2.35.

To capture the inhomogeneous deformation behaviors, the model is implemented into the finite element software, COMSOL Multiphysics via user-defined subroutines. The finite element analysis was performed using the same geometry of specimen and loading conditions (Supplementary Figs. 5, 23). As shown in Fig. 5B, the predicted fluorescence distributions for both cycles qualitatively capture the spatial trends observed in the experiments. Due to the damage, the fluorescence intensity around the hole decreases by more than 30% in both simulation and experiment. To establish a comprehensive framework for simultaneous stress and damage field mapping, we first obtained the experimental stress maps via the linear stress-intensity calibration curve in the first cycle (Fig. 2C). As shown in Fig. 5C, the experimental stress distributions exhibit consistency with the finite element simulations. The simulated fields display slightly broader stress regions, which may arise from idealized assumptions in the constitutive model. It should be noted that the maximum nominal stress value of TN sample is about 8 MPa under uniaxial tension condition (Fig. 2D), which is set as the upper stress limit for stress-intensity mapping relation. Besides, it is worth noting that we only mapped the stress in the first loading cycle. The mapping fails with the second cycle because the damage behaviors would disrupt the initial stress-intensity calibration relation (Fig. 2C, F). Accurately mapping stress after damage would require knowledge of the local maximum strain history and a recalibrated stress–fluorescence relation, which is nontrivial given the spatial variability in the sample geometry. For this reason, we have mapped stress in the first loading cycle (states i–iv) quantitatively, as long as the maximum fluorescence intensity in the sample does not exceed the initial calibrated range. Thus, for a material system with a rate-dependent and path-dependent response, mapping stress is challenge and can be valid in a limited region. However, we would like to stress that this is not specific to our system but is true for all non-scissile mechanophores if irreversible damage is present. There is currently no better way to measure stress with mechanosensitive molecules.

For the damage mapping, we can acquire the distribution contour of the decreased fluorescence intensity by subtracting the fluorescence intensity distribution of map iv from that of map vi, as shown in Fig. 5D (experiment). It shows the accumulated damage distribution of a TN elastomer with a pre-punched hole, where the damage radiates from the edge of the opening, extending outward away from the opening edge, with the degree of damage being more severe closer to the opening edge. The simulated damage distribution from finite element analysis, shown in Fig. 5D (simulation), is consistent with the experimental data. Specifically, the effectiveness of rhodamine as a damage reporter stems from two key features: (i) its activation force (ring-opening) is lower than the force required to break backbone C–C bonds, allowing the mechanophore to activate prior to irreversible network damage; (ii) its activation is reversible, enabling post-deformation signal comparison to infer damage. Based on these principles, one could in principle enhance damage sensitivity by selecting or designing mechanophores with lower activation forces47,65. This allows damage detection at lower strains. However, such a probe would also be much more temperature sensitive and would typically switch faster from one state to another making optical measurements more difficult. Therefore, a compromise must be found between sensitivity and stability if quantification is desired.

Discussion

Conventional approaches to stress mapping and damage visualization in soft materials have predominantly relied on non-scissile and scissile mechanochemical probes14,50,53. Limited success has been achieved in integrating multifunctionality within a single mechanophore system. In this work, we introduced rhodamine-based ring-opening mechanophores into tough elastomers. We successfully decoupled the relationship between the fluorescence responses and damage behaviors in this material system and demonstrated the possibility of mapping both stress and damage fields using the single mechanophore. The chromaticity50 or fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2C) of this type of mechanophores is closely related to the applied force, thereby already being applied in the field of stress sensing66,67,68. However, it is challenging to obtain the damage response using ring-opening mechanophores because the optical signals and the microscopic molecular chain scissions are not directly correlated.

To address this problem, we performed cyclic and stress relaxation tests on mechanofluorescent multiple network elastomers. For the cyclic tests, the fluorescence intensity showed a considerable decrease during the reloading process, while the critical activated stretch /stress for fluorescence activation increased. The stress relaxation experiments (Fig. 3) revealed that the fluorescence intensity reaches a steady state under prolonged displacement hold. Upon unloading and resetting the fluorescence, the intensity values measured when the specimen was stretched to the same position again were found to be almost identical to the initial fluorescence stabilization values. These results indicate that the damage incurred during the initial loading phase does not alter the fluorescence response of the mechanophores. The fluorescence response at this stage is attributed by both intact and damaged molecular chains. Notably, the mechanophores included in damaged molecular chains do not contribute to the fluorescence response during subsequent loading cycles, which explains all the experimental observations. Moreover, the decreased intensities can be quantified in cyclic tests, which serves as an efficient metric to represent the damage levels. Thus, the current approach does not report damage directly, but rather reflects the fraction of mechanophores that become inactive after loading.

Based on the decoupling relationship between chemical fluorescence and mechanical damage behavior identified in the aforementioned experiments, a mechanochemical damage model was constructed to validate the hypothesis. The experimental findings and the simulation results have enabled us to successfully decouple the relationship between the fluorescence response of the rhodamine-based mechanophores and the damage behavior. Eventually, we achieved mapping both stress and damage fields in inhomogeneous conditions using only a single mechanophore. It should be noted that the stress mapping is accomplished in the first loading test because material damage would disrupt the initially validated stress-fluorescence mapping relationship. These findings provide a fundamental understanding of the effect of damage on the activation of this ring-opening mechanophore and allow for a more precise utilization of this force-chemical probe tool to elucidate the mechanisms of microscopic deformation and damage evolution.

Methods

Materials

Rhodamine 6 G ( ≥ 98%) and 2-Hydroxy-4’-(2-hydroxyethoxy)−2-methylpropiophenone (I2959, ≥98%) were purchased from Aladdin. Potassium carbonate (≥98%) and 1,4-Butanediol diacrylate (BDA, ≥98%) were purchased from Aladdin. Acetonitrile, Ethanolamine, 2-Bromoethanol, Dichloromethane, Methanol, Triethylamine, Tetrahydrofuran, Ethyl acrylate (EA), and Ethyl acetate (all ≥98%) were purchased from Sinopharm. Acryloyl chloride (≥98%) was purchased from Macklin. Deuterated DMSO ( ≥ 98%) was purchased from Beijing Isotope. All chemicals were used as received.

Fabrication of single network elastomer

The synthesis of a single network elastomer involved the preparation of a precursor solution containing 2.25 mL (20.7 mmol) of ethyl acrylate monomer, 146 mg (1% of the monomer) of the cross-linker TAR, 15 mg (0.3% of the monomer) of the photoinitiator I2959, and 2.25 mL of ethyl acetate as a solvent. Then the solution was injected into a glass mold and the mold was exposed to ultraviolet irradiation in a UV crosslinking chamber for one hour. Subsequently, the resulting single network elastomer was removed from the chamber and placed in an oven at 90 °C to evaporate the solvent until a constant mass was achieved, resulting in the final product. The detailed synthesis and characterization of mechanophores TAR can refer to Section S1.1.

Preparation of multiple network elastomers

The single network elastomer was immersed in the precursor solution for the matrix network to induce swelling. The matrix network precursor solution comprised 30 mL (276 mmol) of ethyl acrylate monomer, 10.5 μL (0.02% of the monomer) of the cross-linker BDA, and 200 mg (0.3% of the monomer) of the photoinitiator I2956. After achieving swelling equilibrium within half an hour, the specimen was subjected to ultraviolet irradiation inside the UV crosslinking chamber for another half hour, resulting in the formation of a double network elastomer. The processes of swelling and photo-crosslinking were repeated with the double network elastomer immersed in the matrix network precursor solution, ultimately leading to the fabrication of a triple network elastomer. For the detailed synthesis of the elastomers the reader can refer to Section S1.2.

Uniaxial tension

Specimens shaped like a dog bone or with a pre-punched hole (Supplementary Fig. 5) were subjected to uniaxial extension at stretch rates of 0.05 /s and 0.001 /s on an electromechanical universal testing machine (SAS, CMT6103), equipped with a 200 N load cell. For the stress relaxation experiments, an initial loading stretch rate of 0.05 /s and 0.001 /s was applied, with a maximum stretch of 2 or 2.1. An industrial color camera (FLIR BFS-U3-123S6C-C, 12-bit depth) with a frame rate of 20 fps was used to record the relative displacement of the two black markers. The stretch was defined as λ = L/L0, where L0 and L are the distances between the two centroids of the marks in the reference and current configurations, respectively. Moreover, because the camera was also used to collect light signals from specimens, it is necessary to set the white balance of the camera, with red channel set to 1.89 and blue channel to 2.21. An exposure time of 50 milliseconds and a gain of 25 were used.

Fluorescent characterization

Three approaches were used to characterize the fluorescent response including spectrum analysis, chromatic analysis, and intensity analysis. We measured the emission spectra using a fluorescence spectrometer (RF-6000), with an excitation wavelength set at 365 nm. The scan speed was configured at 600 nm per minute, and both the excitation and emission bandwidths were fixed at 10 nm. Frames extracted from the recorded videos were used for fluorescence chromatic analysis and intensity analysis. Then the images acquired via the industrial RGB camera were segregated into red, green, and blue channels, and the grayscale value per pixel in the regions of interest was computed for each channel (R, G, B) by ImageJ. Subsequently, chromaticity calculations were performed using Eq. S1 to characterize color alterations. The intensity analysis method was used to collect the light signals within a specific wavelength range (590-620 nm) and calculate the grayscale values per pixel for the regions of interest within the captured images. More details on the fluorescent characterization can be found in Section S2.2.

Simulation

Through introducing damage evolution into the mechanical theory of multiple network elastomers and the chemical kinetics theory of mechanophores, we developed a mechanochemical damage model. The total stress is contributed by both the first network and matrix. It is assumed that the first network has a broad distribution of chain length. The damage rule is set as an abrupt rupture of all chains with a certain length when a critical deformation is reached. The matrix network exhibits a hyperelastic response without damage. The chemical response is quantified by assuming that the fluorescence intensity is proportional to the total concentration of activated mechanophores. The detailed information on the constitutive model is presented in Section S4.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17092750]. All the data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Yuk, H., Lu, B. & Zhao, X. Hydrogel bioelectronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 1642–1667 (2019).

Wang, Q., Gossweiler, G. R., Craig, S. L. & Zhao, X. Cephalopod-inspired design of electro-mechano-chemically responsive elastomers for on-demand fluorescent patterning. Nat. Commun. 5, 4899 (2014).

Li, H. et al. Reconfigurable 4D printing via mechanically robust covalent adaptable network shape memory polymer. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl4387 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. 3D printing of multifunctional hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900971 (2019).

Rothemund, P. et al. Shaping the future of robotics through materials innovation. Nat. Mater. 20, 1582–1587 (2021).

Ni, C. et al. Shape memory polymer with programmable recovery onset. Nature 7984, 748–753 (2023).

Fu, L., Li, L., Bian, Q., Zhang, Y. & Li, Y. Cartilage-like protein hydrogels engineered via entanglement. Nature 618, 740–747 (2023).

Ge, Q. et al. 3D printing of highly stretchable hydrogel with diverse UV curable polymers. Sci. Adv. 7, eaba4261 (2021).

Kim, J., Zhang, G., Shi, M. & Suo, Z. Fracture, fatigue, and friction of polymers in which entanglements greatly outnumber cross-links. Science 374, 212–216 (2021).

Zhong, D. et al. A strategy for tough and fatigue-resistant hydrogels via loose cross-linking and dense dehydration-induced entanglements. Nat. Commun. 15, 5896 (2024).

Zhao, X. et al. Soft materials by design: unconventional polymer networks give extreme properties. Chem. Rev. 121, 4309–4372 (2021).

Sun, J. Y. et al. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 489, 133–136 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Toughening hydrogels through force-triggered chemical reactions that lengthen polymer strands. Science 374, 193–196 (2021).

Ducrot, E., Chen, Y., Bulters, M., Sijbesma, R. P. & Creton, C. Toughening elastomers with sacrificial bonds and watching them break. Science 344, 186–189 (2014).

Gong, J. P., Katsuyama, Y., Kurokawa, T. & Osada, Y. Double-network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv. Mater. 15, 1155–1158 (2003).

Zhao, X. Multi-scale multi-mechanism design of tough hydrogels: building dissipation into stretchy networks. Soft Matter 10, 672–687 (2014).

Gong, J. P. Why are double network hydrogels so tough?. Soft Matter 6, 2583–2590 (2010).

Yang, J. et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of digitally-printed elastomeric polyurethane: Experimental characterization and constitutive modelling using a nonlinear temperature-strain coupled scaling strategy. Int. J. Solids Struct. 267, 112163 (2023).

Tee, Y. L., Loo, M. S. & Andriyana, A. Recent advances on fatigue of rubber after the literature survey by Mars and Fatemi in 2002 and 2004. Int. J. Fatigue 110, 115–129 (2018).

Webber, R. E., Creton, C., Brown, H. R. & Gong, J. P. Large strain hysteresis and Mullins effect of tough double-network hydrogels. Macromolecules 40, 2919–2927 (2007).

Zhan, L., Qu, S. & Xiao, R. A review on the mullins effect in tough elastomers and gels. Acta Mech. Solid. Sin. 37, 181–214 (2024).

Millereau, P. et al. Mechanics of elastomeric molecular composites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9110–9115 (2018).

Diani, J., Fayolle, B. & Gilormini, P. A review on the Mullins effect. Eur. Polym. J. 45, 601–612 (2009).

Budday, S., Ovaert, T. C., Holzapfel, G. A., Steinmann, P. & Kuhl, E. Fifty shades of brain: A review on the mechanical testing and modeling of brain tissue. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 27, 1187–1230 (2020).

Chen, Y., Mellot, G., van Luijk, D., Creton, C. & Sijbesma, R. P. Mechanochemical tools for polymer materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4100–4140 (2021).

Li, M., Zhang, Q., Zhou, Y. N. & Zhu, S. Let spiropyran help polymers feel force!. Prog. Polym. Sci. 79, 26–39 (2018).

Wang, Q., Gossweiler, G. R., Craig, S. L. & Zhao, X. Mechanics of mechanochemically responsive elastomers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 82, 320–344 (2015).

Kean, Z. S. & Craig, S. L. Mechanochemical remodeling of synthetic polymers. Polymer 53, 1035–1048 (2012).

Sagara, Y. & Kato, T. Mechanically induced luminescence changes in molecular assemblies. Nat. Chem. 1, 605–610 (2009).

Li, Z. A. et al. Highly sensitive built-in strain sensors for polymer composites: Fluorescence turn-on response through mechanochemical activation. Adv. Mater. 28, 6592–6597 (2016).

Muramatsu, T., Sagara, Y., Traeger, H., Tamaoki, N. & Weder, C. Mechanoresponsive behavior of a polymer-embedded red-light emitting rotaxane mechanophore. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 24571–24576 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Distal conformational locks on ferrocene mechanophores guide reaction pathways for increased mechanochemical reactivity. Nat. Chem. 13, 56–62 (2021).

Davis, D. A. et al. Force-induced activation of covalent bonds in mechanoresponsive polymeric materials. Nature 459, 68–72 (2009).

Beiermann, B. A. et al. The effect of polymer chain alignment and relaxation on force-induced chemical reactions in an elastomer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 1529–1537 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Fast reversible isomerization of merocyanine as a tool to quantify stress history in elastomers. Chem. Sci. 12, 1693–1701 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. A novel mechanochromic and photochromic polymer film: When rhodamine joins polyurethane. Adv. Mater. 27, 6469–6474 (2015).

Xu, B., Wang, H., Luo, Z., Yang, J. & Wang, Z. Multi-material 3D printing of mechanochromic double network hydrogels for on-demand patterning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 11122–11130 (2023).

Xu, B., Luo, Z., Xiao, R., Wang, Z. & Yang, J. Hybrid phenol-rhodamine dye based mechanochromic double network hydrogels with tunable stress sensitivity. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 43, 2200580 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Novel reversible mechanochromic elastomer with high sensitivity: Bond scission and bending-induced multicolor switching. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 11874–11881 (2017).

Göstl, R. & Sijbesma, R. P. π-Extended anthracenes as sensitive probes for mechanical stress. Chem. Sci. 7, 370–375 (2016).

Slootman, J. et al. Quantifying rate- and temperature-dependent molecular damage in elastomer fracture. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041045 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Mechanically induced chemiluminescence from polymers incorporating a 1,2-dioxetane unit in the main chain. Nat. Chem. 4, 559–562 (2012).

Sun, P., Qu, S. & Xiao, R. On the theory of mechanically induced chemiluminescence in multiple network elastomers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 184, 105543 (2024).

Lavoie, S. R., Millereau, P., Creton, C., Long, R. & Tang, T. A continuum model for progressive damage in tough multinetwork elastomers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 125, 523–549 (2019).

Vernerey, F. J., Brighenti, R., Long, R. & Shen, T. Statistical damage mechanics of polymer networks. Macromolecules 51, 6609–6622 (2018).

Gossweiler, G. R., Kouznetsova, T. B. & Craig, S. L. Force-rate characterization of two spiropyran-based molecular force probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6148–6151 (2015).

Wu, M. et al. Cooperative and geometry-dependent mechanochromic reactivity through aromatic fusion of two rhodamines in polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17120–17128 (2022).

Kim, J. W., Jung, Y., Coates, G. W. & Silberstein, M. N. Mechanoactivation of spiropyran covalently linked PMMA: effect of temperature, strain rate, and deformation mode. Macromolecules 48, 1335–1342 (2015).

Barbee, M. H. et al. Substituent Effects and Mechanism in a Mechanochemical Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 12746–12750 (2018).

Chen, Y., Yeh, C. J., Qi, Y., Long, R. & Creton, C. From force-responsive molecules to quantifying and mapping stresses in soft materials. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz5093 (2020).

Barbee, M. H. et al. Mechanochromic stretchable electronics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 29918–29924 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Spiropyran mechano-activation in model silica-filled elastomer nanocomposites reveals how macroscopic stress in uniaxial tension transfers from filler/filler contacts to highly stretched polymer strands. Macromolecules 56, 5336–5345 (2023).

Ju, J. et al. Role of molecular damage in crack initiation mechanisms of tough elastomers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2410515121 (2024).

Xiao, R., Han, N., Zhong, D. & Qu, S. Modeling the mechanical behaviors of multiple network elastomers. Mech. Mater. 161, 103992 (2021).

Dargazany, R. & Itskov, M. A network evolution model for the anisotropic Mullins effect in carbon black filled rubbers. Int. J. Solids Struct. 46, 2967–2977 (2009).

Mao, Y., Talamini, B. & Anand, L. Rupture of polymers by chain scission. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 13, 17–24 (2017).

Talamini, B., Mao, Y. & Anand, L. Progressive damage and rupture in polymers. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 111, 434–457 (2018).

Buche, M. R. & Silberstein, M. N. Chain breaking in the statistical mechanical constitutive theory of polymer networks. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 156, 104593 (2021).

Govindjee, S. & Simo, J. A micro-mechanically based continuum damage model for carbon black-filled rubbers incorporating Mullins’ effect. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 39, 87–112 (1991).

Arruda, E. M. & Boyce, M. C. A three-dimensional constitutive model for the large stretch behavior of rubber elastic materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 41, 389–412 (1993).

Silberstein, M. N. et al. Modeling mechanophore activation within a viscous rubbery network. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 63, 141–153 (2014).

Kauzmann, W. & Eyring, H. The viscous flow of large molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 62, 3113–3125 (1940).

Ribas-Arino, J. & Marx, D. Covalent mechanochemistry: theoretical concepts and computational tools with applications to molecular nanomechanics. Chem. Rev. 112, 5412–5487 (2012).

Mark, J. E. (ed.) Physical Properties of Polymers Handbook. (Springer, New York, 2007)

Zhang, H. et al. Mechanochromism and mechanical-force-triggered cross-linking from a single reactive moiety incorporated into polymer chains. Angew. Chem. 128, 3092–3096 (2016).

Gossweiler, G. R. et al. Mechanochemically active soft robots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 22431–22435 (2015).

Cho, S. et al. Large-area cross-aligned silver nanowire electrodes for flexible, transparent, and force-sensitive mechanochromic touch screens. ACS Nano 11, 4346–4357 (2017).

Park, J. et al. A hierarchical nanoparticle-in-micropore architecture for enhanced mechanosensitivity and stretchability in mechanochromic electronic skins. Adv. Mater. 31, 1808148 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 226-2025-00137 (R. X.)), the Natural Science Foundation of Hangzhou (Grant No. 2024SZRYBB040002 (R. X.)), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12321002 (S. Q.)), and the 111 Project, China (Grant No. B21034 (S. Q.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: R. Xiao and C. Creton. Methodology: P. Sun and Q. Wang. Investigation: P. Sun, Q. Wang, and J. Yang. Validation: P. Sun, R. Xiao, Z. Wang, Y. Chen, S. Qu, and C. Creton. Supervision: R. Xiao, Z. Wang, Y. Chen, and C. Creton. Writing – original draft: P. Sun. Writing – review & editing: R. Xiao and C. Creton.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, P., Wang, Q., Yang, J. et al. Quantitative stress and damage mapping in multiple network elastomers using a single mechanophore. Nat Commun 16, 10079 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65086-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65086-3