Abstract

Metallic glasses (MGs) possess the merits of high strength and a large elastic limit. However, they suffer from little tensile ductility in the inhomogeneous deformation regime due to strain softening and shear localization. In this work, we report a substantial increase in tensile plastic strain (εp) from 2.8% to 10% in a Fe-based metallic glass (MG) via non-affine thermal strain (NTS), accompanied by a significant intensity enhancement and a considerable decrease in activation energy (32%) of the β-relaxation. Notably, pronounced strain hardening is observed during tension. These extraordinary tensile properties are structurally attributed to the NTS-promoted formation of a chemical-fluctuation-mediated network structure consisting of interconnected Fe-rich medium-range orders (MROs) and surrounding metalloid-rich clusters, as well as the subsequent temperature and stress-induced unique evolution of the multiscale structural heterogeneities. Specifically, the stress-induced unique MRO formation, α-Fe nanocrystallization, and the irreversible relaxation-induced structural ordering jointly interact with shear banding to transform strain softening into hardening, leading to excellent ductility. These findings demonstrate that simultaneous relaxation-assisted and transformation-mediated deformation stabilizes the inhomogeneous plastic flow under tension, overcoming the ductility bottleneck of MGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metallic glasses (MGs) feature long-range disordered and short-range ordered atomic arrangements, which endow them with excellent physical and mechanical properties1,2,3,4,5,6. Unlike brittle glasses, such as oxide and ionic glasses, MGs with metallic bonding can accommodate strain at the atomic level through the cooperative rearrangement of a group of atoms1. However, due to the absence of crystallographic defects, such as dislocations, the plastic strain in MGs is localized into thin shear bands (SBs) of ~10–20 nm in thickness7,8. This localization, intrinsically linked to shear softening, causes limited plastic strain under compression and catastrophic fracture under uniaxial tension for MGs in a broad inhomogeneous deformation regime, spanning from room temperature to ~0.95 Tg, as indicated by the strain rate-temperature deformation map (Tg is the glass transition temperature)9,10. Unlike crystalline alloys, where annealing can optimize mechanical properties, annealing often leads to embrittlement of MGs due to the free volume annihilation effect of structural relaxation11,12. Accordingly, to enhance plasticity of MGs, various strategies have been developed, primarily aimed at creating more loosely packed regions (LPRs) and improving structural and chemical heterogeneities13 via composition design14,15, high-pressure torsion16, fluxing treatment17,18, cold rolling19, and cryogenic thermal cycling (CTC)20,21. Although some MGs exhibit considerable compression plasticity through these strategies, the macroscopic tensile ductility of most MGs is still limited at room temperature16,22,23. Only a few studies reported limited tensile plasticity of 0.2–2% with strain hardening through strain-induced nanocrystallization, twinning, phase transformations, and shear band ordering23,24,25. Recently, it has been reported that strain hardening and suppression of shear-banding can be achieved in a rejuvenated Zr-based bulk MG by relaxation without structural transformation, leading to a tensile strain of 0.42%26. However, less attention has been focused on the tensile plasticity in the high-temperature inhomogeneous regime of MGs, where increased atomic mobility relaxes the long-range interactions between shear transformation zones (STZs)27,28. A few reports have found that Zr-based MGs exhibit brittle behavior under uniaxial tension at a high temperature of ~0.82 Tg29,30. So far, significant tensile ductility has been obtained only for MGs with a size of sub-micrometers for in situ tensile tests in the electron microscope, where homogeneous deformation is activated31,32. However, the mechanism by which macroscopic MGs exhibit large ductility and strain hardening under tension has not yet been reported. The lack of tensile ductility and the instability of macroscopic plastic flow, as critical bottlenecks for MGs, significantly restrict their industrial applications at both room and high temperatures.

In this study, we investigate the combined effects of medium-range order (MRO), structural/chemical heterogeneities, and β-relaxation on the tensile deformation of a Fe-based MG. This family of MG was selected for its unique combination of excellent soft magnetic properties33,34, super-high strength35, and superior corrosion and wear resistance36,37. Owing to this exceptional combination of properties, Fe-based MGs are not only commercially applied as soft magnets in highly efficient electromagnetic devices but are also promising candidates for various engineering applications, such as medical implants, automobiles, and warships34,38. However, the poor ductility of Fe-based MGs not only hinders their practical applications as structural materials but also limits their magnetic applications. The Fe-based MGs need annealing treatment to release internal stress or induce nanocrystallization for optimizing soft magnetic properties, which can cause severe embrittlement39. The annealed MGs are thus prone to fragmentation or detachment during the core lamination process and service, causing incomplete or damaged magnetic circuits and other serious outcomes34. The absence of stable plastic flow and the relaxation-induced embrittlement of Fe-based MGs are longstanding critical issues that hinder their broader applications.

To address the ductility bottleneck, we subtly regulated the structural/chemical heterogeneities and MRO of the Fe75Co8B10Si3C3P1 soft magnetic MG40 by adjusting the CTC rate and then employed β-relaxation to facilitate activation of numerous STZs. Surprisingly, unlike conventional structure relaxation (induced by annealing) embrittlement, here, CTC-rendered relaxation, accompanied by a reduction in free volume, is found to enhance the ductility of the Fe-based MG at 0.8 Tg. Significantly, unprecedented tensile plasticity of 10% with pronounced strain-hardening capability has been achieved in the CTC-treated Fe-based MG. We identify a synergy between relaxation-assisted and transformation-mediated deformation mechanisms that are responsible for the exceptional ductility and strain hardening. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this mechanism operates effectively across different binary and multicomponent MG families. Our findings are of great importance for expanding the possibilities of MGs as structural and functional materials.

Results

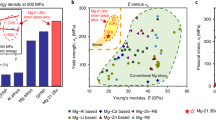

Rapid CTC treatment with an upper temperature of 463 K ( ~ 0.69 Tg) was adopted to the Fe75Co8B10Si3C3P1 MG to tailor their structural/chemical heterogeneity prior to mechanical and structural tests. Then, we focus on the deformation behavior at 0.8 Tg, where a large number of frozen STZs may be activated, and the influence of α-relaxation can be ignored (while maintaining deformation within the inhomogeneous regime). All the AQ and rapid CTC-treated Fe75Co8B10Si3C3P1 alloys exhibit amorphous structure and are noted as AQ, CTC60, CTC30, CTC15 (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). Figure 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2 compare the tensile engineering stress-strain curves of the AQ and CTC-treated samples, all of which exhibit obvious strain-hardening processes before fracture and differ from the homogeneous deformation observed around and above Tg9. This can also be indicated from the true stress-strain curves in the inset of Fig. 1a and strain-hardening rate curves in Fig. 1b. More direct evidence is demonstrated from the increased hardness with increasing tensile strain as shown in the inset of Fig. 1b. Besides, at a given treatment time, the tensile-strained sample shows larger hardness values than the annealed samples. This implies that the increased hardness with increasing strain comprises both the relaxation-induced and stress-induced contributions. Notably, rapid CTC substantially enhances the tensile plasticity, while maintaining the yield strength at ~1120 MPa. The tensile strain εp is 2.8% for AQ and increases to 5.3, 8.4, and 10% for CTC60, CTC15, and CTC30, respectively. The ultimate tensile strength of the CTC30 sample is 1680 MPa. Since the tensile tests were carried out at 0.8Tg, the samples yield at a strain of about 1.5%, which is lower than the usual 2% elastic limit of MGs at room temperature36. Figure 1g summarizes the tensile strain versus normalized temperature (T/Tg) of the present alloys and those MGs reported16,23,41,42,43 (most of which show εp ≤ 2% at a strain rate of 10−4 s−1) under inhomogeneous deformation conditions (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1) to highlight the extraordinary ductility of the present alloys. Furthermore, CTC30 demonstrates a substantial decrease in core loss at 50 and 1 kHz compared to AQ, while maintaining a high saturation magnetic flux density of 1.68 T (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4d–g, the AQ sample exhibits wide-curved domains and narrow fingerprint-like domains, and the CTC60 sample exhibits more irregular edges on the wide domains, indicating a more heterogeneous stress distribution. In contrast, the CTC30 and CTC15 samples exhibit significantly refined magnetic domains characterized by smoother domain wall edges and the absence of fingerprint-like domains, resulting in the optimized soft magnetic properties. Figure 1c–f shows the surface morphology of the deformed ribbons. A small number of secondary SBs are generated along the length of the primary SBs for the AQ sample, corresponding to its limited tensile plasticity (Fig. 1c). The density of SBs increases, and the spacing of SBs narrows obviously for the CTC-treated MGs due to the proliferation of secondary and tertiary SBs. The offset of SBs is visible (Fig. 1d–f, Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). For CTC30 with the highest density of SBs, the interaction of SBs is significantly enhanced, contributing to the largest tensile strain of 10%. Surprisingly, remarkable necking is observed in the CTC30 sample with εp of 8%, demonstrating its large and stable inhomogeneous deformation (Fig. 1h–j). The proliferation of multiple SBs within the necking zone provides direct evidence that plastic necking instability is governed by the propagation and interaction of SBs (Supplementary Fig. 7). The necking phenomena for 3 fractured CTC30 samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. The asymmetry in necking behavior may be related to the uniformly sized rectangular specimens (commonly used for micro-scale metals) with multiscale structural heterogeneity (which leads to the stochastic initiation of shear banding events). In addition, nanovoids with a size of ~650 nm (Supplementary Fig. 9) can be observed in the vicinity of the fracture surface of CTC30, which is associated with free volume aggregation44,45 and is responsible for softening after tensile deformation with εp ~ 8.5%. Notably, these nanovoids were exclusively observed in the CTC30 sample, while no similar features were detected in other samples.

a, b The typical engineering tensile stress-strain curves (a) and the strain-hardening rate versus true strain curves (b) of AQ, CTC60, CTC30 and CTC15 samples tested at 533 K(0.8 Tg), the inset in a is the corresponding true stress-strain curves, the inset in b shows the comparison of the microhardness of the CTC30 sample and tensile-strained CTC30 samples (at 533 K) and the annealed CTC30 (at 533 K) samples. The error bars represent the standard deviation derived from measurements on three independently prepared samples. c–f The SEM images of the surfaces after tensile test for the AQ sample, the CTC60 sample, the CTC30 sample and the CTC15 sample, respectively. g Summary of the tensile plastic strain verses temperature (see Supplementary Table 1 for details, see side bar for chemical compositions). For comparison, the temperature is scaled by Tg. The delineation of homogeneous and inhomogeneous deformation is made with reference to the established deformation map of MGs4. h The SEM image of the surface for a CTC30 sample with 8% tensile strain. i, j The enlarged images of the necking regions indicated by bright blue and orange dotted line, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

It has been found that plastic deformation is closely associated with the activation of β-relaxation and flow units of MGs43,46,47. As indicated in Fig. 2a, CTC treatment significantly enhances the intensity of β-relaxation, with a distinct peak for CTC30 and a shallow shoulder for AQ. The obviousness of β-relaxation can be further quantified by the angle ∠A defined in ref. 47, which increases from ~4° for AQ to ~50° for CTC30 (inset of Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the activation energy of β-relaxation (Eβ) shows considerable reduction (31%) after CTC treatment from 154 ± 5 kJ/mol (~28 RTg) for AQ to 105 ± 4 kJ/mol (~19 RTg) for CTC30 (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 10). The Eβ values of the AQ and CTC60 samples match the empirical relationship Eβ = 26 ± 2 RTg, similar to other MGs48. By contrast, the Eβ values of CTC30 and CTC15 are located below this empirical line and much smaller than those of other MGs with similar Tg (Fig. 2b), which is responsible for the excellent tensile plasticity of CTC30. In addition, the intensity of β-relaxation was found to correlate with the energy distribution of flow units in MGs49,50. A β-relaxation peak is related to an abundant and centralized activation of flow units, while an excess wing or a shallow hump corresponds to a slowly and evenly activated flow unit in broad area with increasing temperature46,50. Thus, the linear heating stress relaxation kinetics were studied to further uncover the effect of CTC on the activation of flow units and β-relaxation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 11, the stress decay (∆σ) increases slowly to about 60 MPa in the initial stage (stage I) and then increases rapidly until it remains constant (stage II). The activation energy spectra p(E), which represents the total available property change caused by all the activation processes between E and E + dE51, is determined from the stress relaxation curve (Supplementary Note 3) and shown in Fig. 2c. The activation energy of flow units that contribute to relaxation is around 95 ~ 135 kJ/mol (Fig. 2c) for all the samples. However, the p(E) of CTC30 and CTC15 are about 50% higher than that of AQ, indicating more flow units activated50. It has been reported that the potential energy barrier of STZ was almost equivalent to the activation energy of β-relaxation, and a larger fraction of activated flow units can promote cooperative motion of atoms and multiple SB formation48. The lowest Eβ and highest p(E) values, between 110 and 130 kJ/mol in CTC30, indicate its easiest activation and the largest fraction of STZs, which promotes the most abundant formation of multiple SBs under tension.

a The temperature dependence of the loss modulus E” (1 Hz) for the AQ, CTC60, CTC30 and CTC15 samples, E” is normalized by a corresponding maximum (at Tg). ∠A is defined as the angle between the two tangents of the β-relaxation peak. The inset shows the degree of ∠A which characterizes the obviousness of the β-relaxation for AQ, CTC60, CTC30 and CTC15 samples. b The activation energy of β-relaxation versus 26 RTg of AQ, CTC60, CTC30 and CTC15 samples compared with other MGs (see Supplementary Table 2 for details). The solid line represents Eβ = 26 RTg, while the upper and lower dashed lines correspond to Eβ = 28 RTg and Eβ = 24 RTg, respectively. c The activation energy spectra of the AQ, CTC60, CTC30 and CTC15 samples. d–f The DSC curves (d), the relaxation spectra obtained by subtracting the first and second successive traces of specific heat Cp (see Methods for details) (e), the variation of ΔHrel (f) of AQ, CTC60, CTC30 and CTC15 samples. The dotted vertical blue lines in (d) and (e) respectively, mark the peak temperature of the endothermic peak and the onset temperature of the enthalpy relaxation. The shaded regions’ area represents the ΔHrel. The error bars in e represent the standard deviation derived from measurements on three independently prepared samples. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Many approaches, including CTC, are employed to improve the plasticity of MGs by rejuvenating the structure to a higher energy state19,20,21. To explore the CTC-induced variation in energy state, DSC measurements were conducted. As shown in Fig. 2d, all the DSC curves exhibit a broad exothermic peak centered at approximately 550 K before crystallization, primarily related to the annihilation of free volume52. Notably, an endothermic peak appears before the exothermic peak for the CTC-treated samples, whose temperature range is close to the β-relaxation (Fig. 2a, d), indicating their intrinsic correlation. This unusual structural recovery process in 400–535 K, recognized as a sub-Tg peak52,53, was widely observed in Zr-, La- and Fe-based MGs after annealing below Tg for several hours or longer54. As shown in Fig. 2e, the onset temperature of the enthalpy relaxation (the shaded region) of the CTC-treated samples, corresponding to their endothermic peak in Fig. 2d, starts about 80 K higher than that of AQ. This indicates that the reversible endothermic peak of the CTC-treated samples associated with the recovery of the LPRs delays the irreversible structural relaxation52,55. Besides, the MGs after CTC treatment show decreased relaxation enthalpy (ΔHrel) and increased hardness (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 12a), which indicates CTC-induced relaxation instead of rejuvenation. It is worth pointing out that there is no noticeable change in the variation of ΔHrel for all the AQ and CTC-treated samples after placing 9 months at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 12b). This implies the CTC-induced irreversible changes of structural heterogeneity.

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) analysis was then conducted for AQ, CTC30, and CTC60 to investigate their atomic structure differences. The HRTEM images and diffuse halo rings in the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns indicate the typical amorphous structure (Fig. 3a, b). Interestingly, some unique crystal-like MROs can be distinguished from the matrix of AQ and CTC-treated samples. These MROs exhibit an imperfect crystal-like structure with a lattice d-spacing of ~0.20 nm corresponding to the (110) plane of α-Fe phase (Supplementary Fig. 13). The unique MROs with α-Fe like structure can be observed more clearly from the fast Fourier transformation (FFT) filtering image in Fig. 3c (transformed from region c in Fig. 3b) and the spatial auto-correlation images (Fig. 3d1–d8). FFT filtering with varying passband ranges yields consistent results (Supplementary Fig. 14). The number of these MROs (~1 nm in size) increases significantly for CTC30 compared to AQ, and larger MROs with 2–3 nm in size are formed in the CTC60 sample (Supplementary Fig. 15). Autocorrelation analysis quantitatively reveals a 50% higher MRO area fraction in CTC30 versus AQ (Supplementary Fig. 16). Note that the fraction of MRO clusters with α-Fe like structure is positively correlated with the tensile plasticity. Moreover, the MROs are predominantly located in the bright regions of the high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image (Supplementary Fig. 17). The enhancement of the structure ordering in CTC30 can be further verified from the more pronounced splitting in the second peak and appearance of shallow peaks around 4 and 7 Å in the radial distribution functions (RDFs) curves (Fig. 3e). At the nanometer scale, CTC30 exhibits enhanced structural heterogeneities, as indicated by the larger contrast variation in its HAADF-STEM images (Supplementary Fig. 18). Furthermore, interesting periodic concentration fluctuations of Fe and Si with an average wavelength of ~6 nm are observed in CTC30, exhibiting a strong correlation along both the ribbon and thickness directions (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20). This results in a unique network structure consisting of mutually neighboring Fe-rich clusters (MROs with α-Fe like structure) and Si-rich clusters (which are harder to accommodate shear)56,57. The EDS concentration line profiles of Fe, Co, Si, and P along the diagonal of the HAADF-STEM images further confirm that these chemical fluctuations are more significant in CTC30 compared to those in the AQ sample (Fig. 3f, g and Supplementary Fig. 21). This CTC-enhanced compositional heterogeneity resembles the temperature-cycling-induced nanoscale heterogeneity of Gd atoms observed in Gd-Co metallic glass by Hosokawa et al. 58.

a, b The HRTEM images with corresponding SAED patterns as insets of the AQ (a) and CTC30 samples (b), respectively. The crystal-like MROs with sizes of about 1 nm are identified by the white lines in (a and b). c The FFT-filtered image of the area indicated by the yellow dashed box in (b). FFT filtering is applied using a passband of 4.1 ~ 5.8 nm⁻¹. d1–d8 The spatial autocorrelation of the yellow dashed area labeled d1-d8 in (c), respectively. e The RDF curves of the AQ and CTC30 samples. The arrows point to the emerging shallow peaks at ~4 Å and ~7 Å in the RDF of the CTC30 sample, indicating enhanced structure ordering. f, g The EDS concentrations line profiles of Fe (f), Si (g) along the diagonal of the HAADF-STEM images (Supplementary Fig. 18). The standard deviations (s) of the atomic percentages are quantified as follows: Fe: s = 5.8% (AQ), s = 6.6% (CTC30); Si: s = 2.8% (AQ), s = 4.6% (CTC30). h, i Contour-line maps of H for CTC30 (h) and CTC30 with 8% tensile strain (i). j The comparison of the FWHM of the H distributions for CTC30, tensile-strained CTC30 (at 533 K) and annealed CTC30 (at 533 K). The error bars represent the standard deviation derived from measurements on three independently prepared samples. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore the potential effects of the cooling rate gradient along the thickness of the ribbon on the structural gradient and its impact on tensile plasticity, we conducted nanoindentation and atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments. Nanoindentation tests reveal a relatively large standard deviation along the thickness direction in both AQ and CTC-treated samples, confirming macroscopic heterogeneity (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). Though the pronounced data scattering obscures any discernible hardness gradient, nanoscale AFM modulus mapping of the AQ cross-section reveals a progressive increase in Young’s modulus with increasing distance from the roller side (Supplementary Fig. 24). This modulus enhancement coincides with reduced mechanical heterogeneity, as quantified by the decreasing full width at half maximum (FWHM) of modulus distribution curves. However, it is noted that the limited tensile plasticity (2.8%) of AQ indicates that the intrinsic gradient structures contribute minimally to the ductility enhancement from CTC treatment.

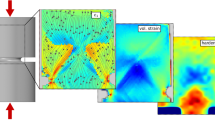

Next, the response of intrinsic multiscale heterogeneities to stress is explored to reveal the deformation mechanisms. Firstly, we investigate the variation of spatial heterogeneities with tensile strain by nanoindentation at an array of 14 × 14 sites. The nanoindentation hardness (H) values of the tensile-strained samples are significantly higher than those of the samples annealed at 533 K (Supplementary Fig. 25), once again verifying the strain-hardening behavior. The typical two-dimensional (2D) map of H for CTC30 shows the interconnected local regions of low H and high H (Fig. 3h), which indicates the presence of hard and soft zones. Similar features are observed for the deformed CTC30 samples with 4 and 8% tensile strain (Fig. 3i, Supplementary Fig. 26a), whose average H is larger than that of CTC30. In addition, the comparison of the FWHM variations of the H distributions for the deformed and annealed CTC30 samples indicates that stress induces an additional increase in inhomogeneity at the micrometer scale (Fig. 3j, Supplementary Fig. 26, and Supplementary Note 4). The evolution of atomic structures under tensile deformation and their interaction with SBs for CTC30 is further illustrated below.

HRTEM observation reveals considerable offset of shear steps on the surfaces of the deformed specimens, which increases (up to 1.1 µm) with increasing tensile strain (Supplementary Fig. 27). For the deformed sample with strain of 4%, α-Fe nanocrystals (NCs) with 4-10 nm are observed in the vicinity of the shear banding region (Fig. 4a, b), and the propagation trace of the SB deflects around a NC. The thickness of SB is around 12 nm, consistent with previous studies7,8,59. Figure 4c shows (110) lattice fringes from an α-Fe NC near the SB. The corresponding inverse FFT image reveals slight lattice distortion within the NC during SB propagation (Fig. 4d). For the CTC30 MG with εp = 10%, it is observed that a broad SB with an initial thickness of ~50 nm bifurcates into SB1 and SB2 with thicknesses of ~25 and ~18 nm, respectively (Fig. 4e, j). The morphology of SBs in CTC30 MG is highly sensitive to tilt angles (α) of the HRTEM specimen (Supplementary Fig. 28). The propagation of SB2 terminates at a NC with a size of ~7 nm (Fig. 4e) and at different locations of the SB2 edge, some NCs can also be observed. As indicated in Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig. 29, crystallization occurs mainly at localized positions around the shear banding region. The inverse FFT image of Fig. 4g shows that intense lattice distortion and many dislocations exist in the α-Fe NCs, indicating the strong interaction between α-Fe NCs and SBs (Fig. 4h). Notably, at the bifurcation of the broad SB, many NCs with sizes of 2 ~ 7 nm are observed inside the SBs (Supplementary Fig. 28c). This is different from the CTC30 sample with εp of 4%, in which the NCs are mainly observed around the edge of SB. Furthermore, for tensile-strained CTC30, the distribution of elements changes significantly due to the propagation of SB in the amorphous matrix (Fig. 4i, j, Supplementary Fig. 30). Fe and Co concentrations decrease in the shear banding region, which is related to the dilatation effect of SBs8,60. Interestingly, Si and P tend to aggregate into the SBs, which may be due to smaller-size atoms being more likely to occupy the free volume within the SBs61.

a The cross-sectional HRTEM image of the SB in CTC30 with εp of 4%. The shear propagation traces are indicated by white arrows. The inset shows the cross-sectional HAADF-STEM image of the SB and the corresponding shear offset in (a). b The corresponding SAED pattern of (a). c The magnified HRTEM image of yellow square region in (a). d Inversed FFT image of (c). e The micrographs of the SBs in CTC30 with εp of 10%. The tilt angles α of HRTEM micrographs is 10°. f The magnified HRTEM image of the larger yellow square region in (e). Inset shows the corresponding SAED pattern. g The magnified HRTEM image of the smaller yellow square region in (e). h Inversed FFT image of (g). i HAADF-STEM micrograph and the EDS mappings of shear band in CTC30 with tensile strain of 10%. j The elemental net intensity profiles along the dashed line which crosses the SB1 and SB2 in Supplementary Fig. 28a. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The above results indicate the critical importance of the variations of MRO and structural/chemical heterogeneity caused by CTC and tensile deformation to the excellent ductility of CTC30, which will be further discussed. MGs have a wide spectrum of atomic packing heterogeneities with diverse MROs and short-range orders. Compared with other MG families, the Fe-based MGs process abundant directional bonds and some unique MROs, such as metalloid-centered triangular prisms62 and MRO with α-Fe like structure (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 13). After CTC treatment, the significant increase in the number of MROs and chemical fluctuations in CTC30 arise from the local strain produced by heterogeneous thermal expansion/contraction upon temperature changes20. The increased hardness in CTC30 implies that these unique MROs are embedded in a relaxed matrix (with large quantities of denser anti-free volume regions)9. Note that the Fe-Fe(Co) metallic bonds are found to be weaker than the covalent metal-metalloid bonds and more easily accommodate shear56,57. Thus, the localized shear events and string-like motion for β-relaxation primarily take place in these MROs with α-Fe like structures due to their rich relatively soft metal-metal pairs. This can explicate the observation that the largely increased number of MROs significantly facilitate collective local arrangements of atoms and proliferate the activation of β-relaxation/STZ in CTC30 (as evidenced by the largely enhanced β-relaxation peak with lowest Eβ and highest P(E)). Under subsequent tensile deformation, the shear-induced transformation from MRO into α-Fe NC can be explicated within the framework of the potential energy landscape (PEL). Shear stress can flatten out the less stable inherent states in PEL and lead to a significant local softening of shear modulus63,64, which facilitates flow and special structural rearrangements causing density fluctuation, elemental redistribution, and crystallization8,23. For CTC30, as long-range atomic diffusion is negligible at the investigated temperature, the precipitation of α-Fe NCs is kinetically favored due to their structural affinity with MROs. This is similar to the formation of B2 CuZr NCs under deformation in a Cu-based MG24. Further, an in-depth check of the interactions between SBs and NCs reveals that slight lattice distortion has occurred in the α-Fe NC close to the SB in the CTC30 with εp of 4%. The lattice spacing of α-Fe NCs inside the SB is larger than that outside the SB (Supplementary Fig. 31). These results imply that plastic slip occurs first65, followed by the formation of NCs in the early stage of SB propagation.

The MRO cluster formation (Supplementary Figs. 32 and 33), the precipitation of α-Fe NCs, and their growth and lattice distortion and dislocation have a strong impact on the ductility of CTC30. Autocorrelation analysis reveals that CTC30 initially possesses 50% higher MRO area fraction than AQ. Notably, this fraction further increases during tensile deformation (by 40% at εp = 4% and 100% at εp = 10%, Supplementary Fig. 32), indicating the formation of a substantial number of stress-induced MROs. Firstly, the Fe-rich MRO clusters and metalloid-rich clusters act as the source and sink of STZs, respectively, that is, STZs are initiated in the MRO clusters and subsequently hindered by the surrounding metalloid-rich clusters. This unique network structure facilitates the generation of multiple embryonic SBs and prevents the development of a single SB. The formation and evolution of α-Fe NCs together with their dislocations alleviate stress concentration during shear banding in MGs and suppress the formation of new SBs in the amorphous matrix. Secondly, these local features (including their interfaces) increase spatial heterogeneities at different length scales from nanometers to micrometers, which effectively impede further expansion of SBs and deflect/bifurcate the SBs’ propagation, promoting the SB’s multiplication. Finally, the mechanism of strain-hardening is related to the competition among free volume generation, structural ordering (related to free volume annihilation), and structural transformation. Unlike at room temperature, where shear-induced disordering dominates over structural relaxation, typically leading to strain softening60,66, structural relaxation at 0.8 Tg, accompanied by free volume annihilation and structural ordering, can facilitate strain-hardening behavior. This mechanism is similar to that reported in a highly rejuvenated MG, where deformation-induced structural relaxation, accompanied by the annihilation of free volume, leads to strain hardening26. Furthermore, the strong interactions between α-Fe NCs and the SBs promote lattice distortion and dislocation-mediated deformation of the NCs, counteracting the softening caused by shear-band expansion, which plays a crucial role in strain hardening. Accordingly, we propose that relaxation-assisted ordering and deformation-induced α-Fe nanocrystallization collectively act as synergistic deformation mechanisms, stabilizing plastic flow through strain hardening. This synergistic mechanism shows remarkable universality across diverse MG systems. We validated it by employing the CTC-driven MRO engineering strategy with relaxation assistance on representative Cu-, Er-, and Fe-based MG systems, including both metal-metal and metal-metalloid systems (Supplementary Figs. 34 and 35). These studies consistently reveal enhancements in tensile plasticity by 90–200%, accompanied by pronounced strain hardening. The mechanical property enhancements correlate with reduced ΔHrel and intensified β-relaxation universally observed in all systems. For example, the Er52Al29Cu19 MG exhibits plasticity enhancement from 2.0 to 4.2% after the rapid CTC treatment. These results demonstrate that this strategy/mechanism is broadly applicable to a wide range of MGs, regardless of their compositional complexity or bonding characteristics.

In summary, more than 60 years after the discovery of MG, we have achieved unprecedented tensile properties with strain hardening in the inhomogeneous deformation regime of the macroscopic MGs. The considerable enhancement of ductility by CTC treatment is attributed to the NTS-promoted formation of a unique network structure comprising interconnected Fe-rich MRO clusters and surrounding metalloid-rich clusters, which possess distinct abilities to accommodate shear. Unlike the general plasticity-improvement mechanism based on enhancing the LPRs via rejuvenation strategies to facilitate the activation of STZ, distinct plasticity enhancement and strain-hardening mechanisms in a CTC-relaxed MG are unveiled. The multiple deformation mechanisms embody (1) β-relaxation assisted easy initiation of massive STZs from the NTS/deformation-enhanced MRO clusters with α-Fe like structure, (2) irreversible structural relaxation-induced free volume annihilation and suppression of rapid shear banding, (3) slowing and bifurcating mechanism of SBs from the abundant structural/chemical heterogeneities (including the interfaces) at nanometer-to-micrometer scales, (4) shear-driven nanocrystallization and lattice distortion and dislocation formation. The above mechanisms work synergistically to counterbalance strain softening and spread out the distribution of plastic flow, leading to considerable tensile strain and overcoming the ductility bottleneck of MGs. Our work has shown that these mechanisms can be effectively applied across various MG systems to enhance ductility. By strategically engineering MRO, relaxation processes, and polymorphic transformations, we can significantly expand the practical applications of MGs in engineering and functional fields.

Methods

Materials preparation and rapid CTC treatment process

Alloy ingots with nominal atomic composition of Fe75Co8B10Si3C3P1 were prepared by induction melting the mixtures of Fe (99.99 wt.%), Co (99.99 wt.%), Si (99.999 wt.%), B (99.99 wt.%), and pre-alloys of Fe-P (26.4 wt.% P) and Fe-C (5 wt.% C) under an argon atmosphere. MG ribbons with width of 450 ± 4 µm and thickness of 16 ± 1 µm were prepared by melt spinning method. Rapid CTC treatment was applied to the ribbons for 30 min using an upper temperature of 463 K ( ~ 0.8 Tg). In each cycle, the ribbons were first heated by silicone oil bath for t1 (t1 = 60, 30, and 15 s), then immediately inserted into liquid nitrogen for t1. Supplementary Fig. 1a shows the schematic diagram of the rapid CTC treatment. The samples after rapid CTC treatment were denoted as CTC60, CTC30, CTC15.

Microstructural characterization

The morphologies of the surface and cross-section of MGs after tensile tests were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Navo Nano SEM450). The elemental distributions on micron-scale were analyzed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) in SEM. TEM (Talos F200X) equipped with a SuperXG2 EDS detector was used to analyze the microstructural and compositional changes of the samples before and after CTC treatment. For MRO analysis, FFT filtering was applied using a passband of 4.1 ~ 5.8 nm⁻¹. The microstructure of the CTC30 sample along the thickness direction was analyzed by a double spherical aberration corrected TEM (FEI Themis Z at 200 kV). The TEM samples of AQ and CTC30 were prepared by ion beam milling, while the TEM samples of the CTC30 near the tensile fracture and along the thickness direction were fabricated using a scanning electron microscope equipped with a Ga-focused ion beam (FIB, 30 kV, Thermo Scientific Scios 2) and an Omniprobe manipulator. Initially, the pieces were pre-cut from the bulk samples by using current of 7 nA. Subsequently, a series of ion beam currents from 0.5, 0.3, 0.1 nA to 10 pA were applied sequentially to further mill the piece into electron-transparent slices with thickness of 70 nm. The phase structure of MG ribbons was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku Ultima IV) equipped with Cu Kα radiation, the accelerating voltage was 40 kV with a current of 40 mA.

Thermal properties

The thermal behaviors of the MGs were investigated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Netzsch 404 F3) at a heating rate of 20 K/min. As for the measurement of ΔHrel, samples were heated at 20 K/min from room temperature to 780 K, followed by a 2 min hold, then cooled to room temperature at 20 K/min. The second heating cycle of the samples was conducted using the same procedure as the first. The ΔHrel is calculated from the area between the first and second heating curves. Since the Tg signal is not observed in the DSC curves, the overall heat of relaxation before Tx was considered as ΔHrel. To ensure the repeatability of the results, five samples were tested for each condition.

Mechanical properties

The relaxation dynamics were studied using dynamical mechanical analyzer (DMA, Netzsch 242 E). The relaxation behaviors of MGs were tested in tension modes with a constant heating rate of 2 K/min at driving frequencies of 1, 2, 5, and 10 Hz. The linear heating stress relaxations of the MGs were measured by the DMA with a constant tension strain of 0.2% and a heating of 3 K/min. Before the stress relaxation experiments, a 3 min delay was applied to allow the samples to equilibrate at the test temperatures. The uniaxial tensile tests were conducted at selected temperatures using a TA Q850 DMA at a strain rate of 10⁻⁴ s⁻¹ (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d). The precise dimensions of the tested specimens were 450 ± 4 µm in width, 16 ± 1 µm in thickness and 10 mm in gauge length. At least three samples for each condition were tested for data repeatability.

For hardness measurement, the microhardness was evaluated using microhardness tester (FM-700, Future-Tech). Nanoindentation tests were conducted using a Hysitron TI 980 TriboIndenter with a standard Berkovich diamond indenter. The tests applied a maximum load of 10 mN in a cycle of 0.1 s loading, 0.1 s holding, and 0.1 s unloading. For each MG sample, 14 × 14 points were measured for the distribution analysis of the nanoindentation hardness.

The Young’s modulus of the AQ sample cross-section was measured by AFM operating in PeakForce Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping (PFQNM) mode using a RTESPA-525 probe. Measurements were performed with a scan size of 500 × 500 nm², peak force of 800 nN, pixel resolution of 128 × 128, and scan rate of 0.6 Hz.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings in this study are available within the main text and the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Greer, A. L. Metallic glasses. Science 267, 1947–1953 (1995).

Ashby, M. F. & Greer, A. L. Metallic glasses as structural materials. Scr. Mater. 54, 321–326 (2006).

Greer, A. L. & Ma, E. Bulk metallic glasses: at the cutting edge of metals research. MRS Bull. 32, 611–619 (2007).

Yavari, A. R., Lewandowski, J. J. & Eckert, J. Mechanical properties of bulk metallic glasses. MRS Bull. 32, 635–638 (2007).

Wang, W. H. Bulk metallic glasses with functional physical properties. Adv. Mater. 21, 4524–4544 (2009).

Inoue, A. & Takeuchi, A. Recent development and application products of bulk glassy alloys. Acta Mater. 59, 2243–2267 (2011).

Li, J., Spaepen, F. & Hufnagel, T. C. Nanometre-scale defects in shear bands in a metallic glass. Philos. Mag. A 82, 2623–2630 (2002).

Greer, A. L., Cheng, Y. Q. & Ma, E. Shear bands in metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. Rep. 74, 71–132 (2013).

Schuh, C., Hufnagel, T. & Ramamurty, U. Mechanical behavior of amorphous alloys. Acta Mater. 55, 4067–4109 (2007).

Sun, B. A. & Wang, W. H. The fracture of bulk metallic glasses. Prog. Mater. Sci. 74, 211–307 (2015).

Murali, P. & Ramamurty, U. Embrittlement of a bulk metallic glass due to sub-Tg annealing. Acta Mater. 53, 1467–1478 (2005).

Zhu, F. et al. Intrinsic correlation between beta-relaxation and spatial heterogeneity in a metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 7, 11516 (2016).

Sun, Y. H., Concustell, A. & Greer, A. L. Thermomechanical processing of metallic glasses: extending the range of the glassy state. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–14 (2016).

Liu, Y. H. et al. Super plastic bulk metallic glasses at room temperature. Science 315, 1385–1388 (2007).

Chen, L. Y. et al. New class of plastic bulk metallic glass. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 075501 (2008).

Joo, S. H. et al. Work-hardening induced tensile ductility of bulk metallic glasses via high-pressure torsion. Sci. Rep. 5, 9660 (2015).

Yang, W. et al. Mechanical properties and structural features of novel Fe-based bulk metallic glasses with unprecedented plasticity. Sci. Rep. 4, 6233 (2014).

Zhou, J. et al. A plastic FeNi-based bulk metallic glass and its deformation behavior. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 76, 20–32 (2021).

Lee, M. et al. Improved plasticity of bulk metallic glasses upon cold rolling. Scr. Mater. 62, 678–681 (2010).

Ketov, S. V. et al. Rejuvenation of metallic glasses by non-affine thermal strain. Nature 524, 200–203 (2015).

Di, S. et al. Enhancement of plasticity for FeCoBSiNb bulk metallic glass with superhigh strength through cryogenic thermal cycling. Scr. Mater. 187, 13–18 (2020).

Yokoyama, Y., Fujita, K., Yavari, A. R. & Inoue, A. Malleable hypoeutectic Zr–Ni–Cu–Al bulk glassy alloys with tensile plastic elongation at room temperature. Philos. Mag. Lett. 89, 322–334 (2009).

Zhang, Z. et al. Intrinsic tensile ductility in strain hardening multiprincipal element metallic glass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2400200121 (2024).

Pauly, S. et al. Transformation-mediated ductility in CuZr-based bulk metallic glasses. Nat. Mater. 9, 473–477 (2010).

Ding, J. et al. Novel heating- and deformation-induced phase transitions and mechanical properties for multicomponent Zr50M50, Zr50(M,Ag)50 and Zr50(M,Pd)50 (M=Fe,Co,Ni,Cu) amorphous alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 104, 109–118 (2022).

Pan, J. et al. Strain-hardening and suppression of shear-banding in rejuvenated bulk metallic glass. Nature 578, 559–562 (2020).

Sopu, D., Stukowski, A., Stoica, M. & Scudino, S. Atomic-level processes of shear band nucleation in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 195503 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. Expanding the homogeneous regime of deformation in bulk metallic glass by electromigration-induced rejuvenation. Commun. Mater. 1, 44 (2020).

Vormelker, A. H., Vatamanu, O. L., Kecskes, L. & Lewandowski, J. J. Effects of test temperature and loading conditions on the tensile properties of a Zr-based bulk metallic glass. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 39a, 1922–1934 (2008).

Vatamanu, L. O. & Lewandowski, J. J. Pressure and temperature effects on tensile strength andplasticity of metallic glasses. Mech. Mater. 67, 86–93 (2013).

Guo, H. et al. Tensile ductility and necking of metallic glass. Nat. Mater. 6, 735–739 (2007).

Ma, E. & Ding, J. Tailoring structural inhomogeneities in metallic glasses to enable tensile ductility at room temperature. Mater. Today 19, 568–579 (2016).

McHenry, M. E., Willard, M. A. & Laughlin, D. E. Amorphous and nanocrystalline materials for applications as soft magnets. Prog. Mater. Sci. 44, 291–433 (1999).

Silveyra, J. M., Ferrara, E., Huber, D. L. & Monson, T. C. Soft magnetic materials for a sustainable and electrified world. Science 362, eaao0195 (2018).

Inoue, A., Shen, B. L. & Chang, C. T. Super-high strength of over 4000MPa for Fe-based bulk glassy alloys in [(Fe1−xCox)0.75B0.2Si0.05]96Nb4 system. Acta Mater. 52, 4093–4099 (2004).

Greer, A. L., Rutherford, K. L. & Hutchings, I. M. Wear resistance of amorphous alloys and related materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 47, 87–112 (2013).

Li, H. X. et al. Fe-based bulk metallic glasses: glass formation, fabrication, properties and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 103, 235–318 (2019).

Huo, Z. X. et al. A review of the preparation, machining performance, and application of Fe-based amorphous alloys. Processes 10, 1203 (2022).

Zhou, J., You, J. & Qiu, K. Advances in Fe-based amorphous/nanocrystalline alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 040702 (2022).

Cai, M. et al. Improvement of soft-magnetic properties for Fe-based amorphous alloys with high saturation polarization by stress annealing. Mater. Res. Lett. 11, 595–603 (2023).

Song, K. K. et al. Significant tensile ductility induced by cold rolling in Cu47.5Zr47.5Al5 bulk metallic glass. Intermetallics 19, 1394–1398 (2011).

Yu, H. B. et al. Tensile plasticity in metallic glasses with pronounced beta relaxations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 015504 (2012).

Di, S. et al. Large tensile plasticity induced by pronounced β-relaxation in Fe-based metallic glass via cryogenic thermal cycling. Mater. Des. 222, 111074 (2022).

Flores, K. M. & Dauskardt, R. H. Mean stress effects on flow localization and failure in a bulk metallic glass. Acta Mater. 49, 2527–2537 (2001).

Shao, Y., Yang, G. N., Yao, K. F. & Liu, X. Direct experimental evidence of nano-voids formation and coalescence within shear bands. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 181909 (2014).

Yu, H. B., Wang, W. H., Bai, H. Y. & Samwer, K. The β-relaxation in metallic glasses. Natl Sci. Rev. 1, 429–461 (2014).

Yu, H. B., Wang, Z., Wang, W. H. & Bai, H. Y. Relation between β relaxation and fragility in LaCe-based metallic glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 358, 869–871 (2012).

Yu, H. B. et al. W. Relating activation of shear transformation zones to β relaxations in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B 81, 220201 (2010).

Luo, P. et al. Prominent β-relaxations in yttrium based metallic glasses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 031907 (2015).

Lu, Z. et al. Revealing β-relaxation mechanism based on energy distribution of flow units in metallic glass. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 144501 (2016).

Gibbs, M. R. J., Evetts, J. E. & Leake, J. A. Activation energy spectra and relaxation in amorphous materials. J. Mater. Sci. 18, 278–288 (1983).

Meng, Y. H. et al. Rejuvenation by enthalpy relaxation in metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 241, 118376 (2022).

Hu, L. & Yue, Y. Secondary relaxation in metallic glass formers: its correlation with the genuine Johari−Goldstein relaxation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 15001–15006 (2009).

Zhao, R. et al. Reversible and irreversible β-relaxations in metallic glasses. Phys. Rev. B 101, 094203 (2020).

Chen, H. S., Inoue, A. & Masumoto, T. Two-stage enthalpy relaxation behaviour of (Fe0.5Ni0.5)83P17 and (Fe0.5Ni0.5)83B17 amorphous alloys upon annealing. J. Mater. Sci. 20, 2417–2438 (1985).

Gu, X., Poon, S. J., Shiflet, G. J. & Widom, M. Mechanical properties, glass transition temperature, and bond enthalpy trends of high metalloid Fe-based bulk metallic glasses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 161910 (2008).

Gu, X., Poon, S. J., Shiflet, G. J. & Widom, M. Ductility improvement of amorphous steels: roles of shear modulus and electronic structure. Acta Mater. 56, 88–94 (2008).

Hosokawa, S. et al. Structural and dynamical changes in a Gd-Co metallic glass by cryogenic rejuvenation. Acta Mater. 284, 120616 (2025).

Sheng, H. et al. Mapping shear bands in metallic glasses: from atomic structure to bulk dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 245501 (2022).

Liu, C., Roddatis, V., Kenesei, P. & Maaß, R. Shear-band thickness and shear-band cavities in a Zr-based metallic glass. Acta Mater. 140, 206–216 (2017).

Pan, J., Chen, Q., Liu, L. & Li, Y. Softening and dilatation in a single shear band. Acta Mater. 59, 5146–5158 (2011).

Naz, G. J. et al. Composition formulas of Fe-based transition metals-metalloid bulk metallic glasses derived from dual-cluster model of binary eutectics. Sci. Rep. 7, 9150 (2017).

Malandro, D. L. & Lacks, D. J. Relationships of shear-induced changes in the potential energy landscape to the mechanical properties of ductile glasses. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 4593–4601 (1999).

Liu, C., Guan, P. & Fan, Y. Correlating defects density in metallic glasses with the distribution of inherent structures in potential energy landscape. Acta Mater. 161, 295–301 (2018).

Glushko, O. et al. How to catch a shear band and explain plasticity of metallic glasses with continuum mechanics. Nat. Commun. 15, 5601 (2024).

Pan, J. et al. Extreme rejuvenation and softening in a bulk metallic glass. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–9 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52231005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H., Q.L. and B. Shen designed the research project; F.H. and M.C. fabricated the samples and performed the mechanical experiments and structural tests; F.H., Q.L., Z.G. and B. Shen conceptualized the paper; Q.L. and F.H. wrote the draft of the manuscript; All the authors analyzed the data and contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pingjun Tao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, F., Luo, Q., Cai, M. et al. Transformation-mediated and relaxation-assisted macroscopic tensile plasticity with strain-hardening in metallic glass. Nat Commun 16, 10147 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65120-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65120-4