Abstract

Changes in the immune microenvironment are frequent in cancers occurring in adult patients, yet our understanding of the pediatric cancer immune microenvironment and its clinical relevance is limited. We investigate the immune microenvironment in pediatric T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), using single-cell CITE-seq and immune repertoire analyses. We identify a T-ALL subgroup characterized by a remodeled immune microenvironment, which is associated with adverse clinical outcome in minimal residual disease low patients. This adverse immune landscape is dominated by the presence of a population of non-malignant CD4-CD8-TCRαβ T cells that interact with CXCL16 expressing non-classical monocytes. Leukemia cell intrinsic transcriptional rewiring in these patients is associated with activation of Rap1 signaling. Inhibiting Rap1 signaling results in increased sensitivity to the BCL2/BCL-XL inhibitor navitoclax. Our study provides insights into the immune microenvironment of pediatric hematologic malignancies, forming the basis for identifying potential (immuno) therapeutic targets and risk stratification for treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

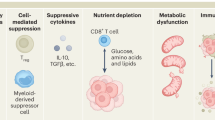

Targeting immune dysfunction within the tumor microenvironment has been recognized as a promising strategy in many adult tumors with high mutational burden and neoantigen load1,2,3,4. However, the exact composition of the immune microenvironment at single-cell resolution remains largely unknown in many pediatric malignancies. Studies in pediatric acute leukemias and pediatric solid tumors have pointed to alterations in immune cell subsets, including myeloid cells and T cells5,6,7,8,9. For example, the presence of non-classical monocytes was associated with poor prognosis in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)5. Additionally, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are present in many solid and hematologic malignancies in adults, but these represent a heterogeneous group of dysfunctional CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocytes. However, the biological and clinical significance of the diverse subsets remains unclear in most cancers10,11,12.

Single-cell studies in T-ALL, a hematologic malignancy predominantly occurring in children and young adults13,14,15, have so far focused on malignant cells16,17, while a comprehensive understanding of the associated immune network is missing. T-ALL is an aggressive malignancy characterized by disruption of normal thymocyte development, leading to accumulation of immature T cell lymphoblasts in the bone marrow and peripheral blood. Although intensified multi-agent chemotherapy has led to improved overall survival rates up to 80% in children, relapsed/refractory T-ALL remains difficult to treat18,19. Targeted therapies, including against NOTCH1, the most frequently mutated oncogene in T-ALL, have shown limited successes and are associated with genetic and epigenetic drug resistance20,21,22. Moreover, identifying epitopes uniquely expressed on leukemia and not expressed by normal T cells has been challenging23, thus indicating a need to identify targetable alterations in the immune microenvironment.

In this study, we generate a single-cell cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes (CITE-seq) and immune repertoire atlas from 136,671 CD45+ cells in pediatric T-ALL patients and healthy donors. We identify a distinct T-ALL subgroup that shows enrichment of double-negative (CD4-CD8-) TCRαβ (DNαβ) T cells and non-classical monocytes, which is linked to poor clinical outcomes in minimal residual disease (MRD) low patients. Our findings uncover a potential CXCL16-mediated interaction between non-classical monocytes and DNαβ T cells and identify Rap1 signaling in leukemia cells as a therapeutic vulnerability. Together, our study provides novel insights into the immune microenvironment of pediatric hematologic malignancies that will form the basis for the identification of novel (immuno)therapeutic targets.

Results

Characterizing the CD45+ immune microenvironment in pediatric T-ALL

To comprehensively define the immune microenvironment in T-ALL, we generated single-cell transcriptome and surface protein expression (CITE-seq) and immune repertoire (TCR/BCR-seq) data from fifteen pediatric T-ALL patients at diagnosis and at different treatment timepoints (days 1–6 and at time of remission) and four healthy donors (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 1). Supplementary Data 1 delineates detailed patient information, including enrollment status on DFCI protocol 16-001 (NCT00400946; Treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children). All patients received standard of care multi-agent chemotherapy treatment, including dexamethasone, doxorubicin, vincristine, and asparaginase for induction. We included 204 feature barcoding antibodies to uncover selected surface protein expression (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 2) and in addition profiled alpha-beta (αβ) T and B cell receptor repertoire (TCRαβ/BCR) to investigate clonality in αβ+ T cells and B cells, respectively. Mononuclear cells from peripheral blood (PB; longitudinal) or bone marrow (BM; diagnosis only) were isolated and CD45high immune cells and CD45dimCD7+ malignant cells were sorted and subsequently pooled to enrich for immune cells. For comparison, we also sorted CD45high immune cells from four healthy donors (Supplementary Fig. 2). Single-cell sequencing of the transcriptome (scRNA-seq), surface protein expression (antibody-derived tag-seq, scADT-seq) and immune repertoire (scTCRαβ/scBCR-seq) was performed using the 10x Genomics platform (Fig. 1a). In total, 94,649 immune and 42,022 malignant cells passed quality control and doublet removal, with cells expressing a median of 1599 or 2534 genes, respectively (Supplementary Data 3).

a Schematic overview of the single-cell CITE-seq (transcriptome and surface protein expression) and immune repertoire sequencing (TCRαβ/BCR-seq) workflow. The clinical cohort included fifteen pediatric T-ALL patients for whom samples were collected at diagnosis (Dx, PB (n = 10) and BM (n = 5)), short-term treatment (ST, PB (n = 8)) and remission (RM, PB (n = 6). Four healthy donor samples (PB (n = 2) and BM (n = 2)) were taken along as control samples. Samples were sorted for CD45high immune cells and CD7+CD45dim malignant cells. The 5’ 10x Genomics Immune Profiling sequencing protocol was used to analyze the transcriptome (RNA-seq), surface protein expression (ADT-seq, 204 surface proteins) and immune repertoire (TCRαβ/BCR-seq). b Weighted-nearest-neighbor (WNN) UMAP plot based on transcriptome and surface protein expression (CITE-seq) of 136,671 cells from fifteen T-ALL patients and four healthy donors, colored by cell type. mDCs: myeloid dendritic cells; pDCs: plasmacytoid DCs; NK: natural killer; HSPC: hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. c Bubble heatmap showing normalized gene expression (left) and surface protein expression (right) of selected signature genes or proteins for cell types shown in (b). d Surface protein expression of CD34, CD1a, CD3, CD4 and CD8 in malignant cells and normal T cells from T-ALL patients at diagnosis. e Heatmap of average RNA expression of known T-ALL oncogenes15 in malignant cells of T-ALL patients at diagnosis. f Heatmap of percentage of cells with TCRβ motifs detected in the 10x Genomics scTCRαβ-seq data. g Distribution of immune cell types in healthy donors (BM: n = 2, PB: n = 2) and T-ALL patient samples (diagnosis: BM: n = 5, PB: n = 10; prophase: PB: n = 6; treatment: PB: n = 2, remission: PB: n = 6).

Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction based on the transcriptome and surface protein expression showed patient-specific malignant cell clusters and major immune cell type clusters (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 3a). These cell types included T cells, NK cells, monocytes, dendritic cells and B cells according to Azimuth cell type annotation24 and expression of canonical immune cell lineage marker genes and surface proteins (Fig. 1c). Malignant cells displayed distinct immunophenotyping profiles (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Data 1) and patient-specific gene expression programs, including expression of genes frequently deregulated in T-ALL such as TAL2, TLX3 and LMO115 (Fig. 1e). Importantly, to further distinguish normal T cells from malignant T-ALL cells, we analyzed TCRαβ repertoires. Nine out of fifteen patients expressed clonal CDR3β motifs, which we did not observe in normal T cells from the same patient (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 3b). The other six patients did not express any TCRαβ sequences, consistent with these representing more immature CD34+ T-ALLs that had not undergone TCR rearrangement, yet, or being derived from the gamma-delta (γδ) TCR lineage. Moreover, we identified arm-level copy number variations in malignant cells, which were not detected in normal T cells from T-ALL patients (Supplementary Fig. 3c).

After separating immune cells from malignant cells, we focused on understanding the composition of the immune microenvironment. Notably, we observed differences in the distribution of several major immune cell categories in T-ALL patients at time of diagnosis compared to healthy donors. T cell abundance was reduced in T-ALL samples while at the same time there was an expansion of myeloid cells (Fig. 1g). Importantly, these differences were not related to age as similar trends were not observed by comparing adult and pediatric healthy control donors, except a slight reduction of CD8+ T cells in pediatric healthy donors (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

Enrichment of atypical memory B cells in T-ALL patients at diagnosis

To comprehensively define B cell types in the immune microenvironment, we performed dimensionality reduction based on transcriptome and surface protein expression (Fig. 2a). Integrated analysis of Azimuth cell type annotation, canonical marker gene and surface protein expression identified five B cell types including progenitor, naïve, memory, atypical memory B cells and plasma(blast) cells (Fig. 2a,b). Progenitor B cells, which were only identified in BM samples, were highly depleted from T-ALL patient samples. In contrast, there was a significant enrichment of atypical memory B cells at T-ALL diagnosis as assessed by differential MiloR neighborhood abundance25 (Fig. 2c,d). Atypical memory B cells were characterized by absence of CD21 and CD27 and high expression of ITGAX/CD11c and TBX21 (Fig. 2b) and are found in diseases associated with chronic antigen stimulation26,27. Abundance of these cells was variable across T-ALL patients at diagnosis (0–50% of B cells) and decreased upon treatment (Fig. 2e). Class-switching occurred in ~50% of atypical memory B cells, similarly to memory B cells in healthy donors and T-ALL at diagnosis (Fig. 2f).

a WNN UMAP plot based on transcriptome and surface protein expression of 14,587 B cells colored by B cell types. b Bubble heatmap showing normalized gene expression (left) and surface protein expression (right) of selected signature genes or proteins for B cell types shown in (a). c Distribution of B cell types in healthy donors (BM: n = 2, PB: n = 2) and T-ALL patients (diagnosis: BM: n = 5, PB: n = 10; prophase: PB: n = 6; treatment: PB: n = 2, remission: PB: n = 6). At.: atypical. d, Log2 fold changes of differential neighborhood abundance testing by MiloR25. MiloR neighborhoods (n = 430, where each neighborhood contains on average 15 cells) are grouped by B cell type. Colors indicate an enrichment (red) or depletion (green) of B cell type at T-ALL diagnosis if more than half of the neighborhoods were significantly enriched/depleted (spatial FDR < 0.1). e Boxplot showing percentage of atypical memory B cells of B cells for healthy donors (n = 4) and T-ALL patient samples across treatment (diagnosis n = 15; prophase n = 6; treatment n = 2, remission n = 6). PB/BM samples are indicated by a square (BM) or circle (PB). An unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. f Proportion of expressed BCR constant chain (scBCR-seq) in B cells in healthy donors and T-ALL patients at diagnosis. g Heatmap of scaled average gene (left) and surface protein (right) expression of selected differentially expressed genes across B cells. See Supplementary Data 4 for full list of differentially expressed genes.

To further characterize the transcriptional regulation of atypical memory B cells found in T-ALL, we performed differential expression analysis across naïve and memory B cells from healthy donor cells and T-ALL samples at diagnosis (Supplementary Data 4). We observed high surface protein expression of multiple BCR inhibitory receptors (e.g. PD1/CD279, FCRL-5/CD307e and CD22) and high expression of genes associated with late stages of B cell differentiation (e.g. SOX5) in atypical memory B cells from T-ALL patients (Fig. 2g). Furthermore, the presence of BCR inhibitory receptors suggests that these cells are unresponsive to BCR signaling, as described for atypical memory B cells in AML9.

Altered composition of T cell types in T-ALL

We next focused on T and NK cell types in the T-ALL microenvironment. Transcriptome and surface protein expression analysis revealed eleven T cell types including naïve T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs) and effector T cells and two subtypes of NK cells including CD56+ and CD16+ NK cells (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, differential MiloR neighborhood analysis25 showed a significant enrichment of CD3+CD4-CD8-TCRαβ+ (double-negative, DNαβ) T cells in the T-ALL microenvironment at diagnosis in contrast to a reduction of NKT, naïve and memory T cells (Fig. 3c–e). Moreover, endogenous T cells in T-ALL patients at diagnosis showed lower TCRαβ diversity compared to healthy donor T cells (Fig. 3f), illustrated by an altered T cell composition including clonal CD8+GZMB+ T cells and DNαβ T cells (Fig. 3g). We also observed an enrichment of CD56+ NK cells in T-ALL at diagnosis, although this was not significant by MiloR differential analysis (Fig. 3c,d). Together, this suggests an altered T cell immune system in T-ALL.

a WNN UMAP plot based on transcriptome and surface protein expression of 46,754 TNK cells colored by T cell types. b Bubble heatmap showing normalized gene expression (left) and surface protein expression (right) of selected signature genes or proteins for T cell types shown in (a). c Distribution of T cell types in healthy donors (BM: n = 2, PB: n = 2) and T-ALL patients (diagnosis: BM: n = 5, PB: n = 10; prophase: PB: n = 6; treatment: PB: n = 2, remission: PB: n = 6). d Log2 fold changes of differential neighborhood abundance testing by MiloR25. MiloR neighborhoods (n = 2038, where each neighborhood contains on average 26 cells) are grouped by T cell type. Colors indicate an enrichment (red) or depletion (green) of T cell type at T-ALL diagnosis if more than half of the neighborhoods were significantly enriched/depleted (spatial FDR < 0.1). e Surface protein expression of TCRαβ, CD4 and CD8 in T cell types (n = 39,006 T cells across 4 healthy donors and 15 T-ALL patients). f Chao1 TCRαβ diversity index scores (Immunarch82) of normal T cells in healthy donors (n = 4) and T-ALL patients at diagnosis with at least 75 T cells (n = 10). An unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. g Circle packing plot showing T cell type (color) in relation to TCRαβ clonotype for healthy donors (left), T-ALL diagnosis (right). Grouped T cells in bold circles indicate clonal cells (i.e. same TCRαβ cdr3 motif). h Heatmap of percentage of cells with TCRβ motifs detected in the 10x Genomics scTCRαβ-seq results. ‘Other TCRβ’ indicates any other TCRβ motif than the clonal TCRβ motifs found in malignant cells (see Fig. 1f). i Heatmap of t-test statistics of TCRαβ feature enrichment (Mann-Whitney U test FDR < 0.01, ConGA84) in T cells.

As most T-ALL develop from a CD4-CD8- thymic precursor, we next investigated the possibility that DNαβ T cells originate from malignant cells. First, DNαβ T cells lacked expression of T-ALL and double-negative thymocyte associated genes such as PTCRA (pre-TCR), ERG, CD34 and DNTT (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). Second, when comparing TCRβ CDR3 motifs of malignant cells and DNαβ T cells, we did not capture any malignant TCRβ motifs in DNαβ T cells (Fig. 3h). Third, while arm-level copy number variation analysis showed patient-specific profiles in malignant cells, these were not observed in DNαβ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4d). Of note, DNαβ T cells with their unique surface protein expression profile (CD7-CD38+CD27+CD57+CD45RA+) were also present in healthy donors, although at very low frequency ( < 3% of T cells) (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 4e). These data suggest that DNαβ T cells are not originating from their malignant T-ALL counterparts. Notably, although we did not detect CD8A RNA expression that is indispensable for surface CD8 expression, DNαβ T cells expressed low levels of CD8B, suggesting these might have been derived from the CD8+ lineage (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 4b). Correspondingly, DNαβ T cells shared TCRαβ CDR3 motif characteristics with CD8+ T cells but not with CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3i), similarly to what is observed in other DNαβ T cells28.

Features of T cell activation and antigen reactivity in DNαβ T cells

To further characterize T-ALL associated DNαβ T cells, we performed differential expression analysis across T cell subtypes (Fig. 4a). Gene set enrichment analyses of genes significantly higher expressed in DNαβ T cells compared to other T cell subtypes revealed enrichment of signatures related to several T cell processes including ‘Immune response’, ‘PD-1 signaling’ and ‘T cell activation’ (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Data 5), suggesting these cells are actively regulating immune responses. For example, significant genes included HAVCR2/CD366 and TIGIT (inhibitory receptors), ISG20 and GZMA (immune response) and CD38 and LGALS3 (T cell activation) (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, DNαβ T cells displayed features of T cell activation in an antigen-dependent manner. TNFRSF9 (encoding CD137) is a well-known marker of antigen-reactive CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and its expression is activation dependent11,12,29. Thirteen percent of DNαβ T cells at initial diagnosis displayed CD137 on the cell surface with most cells simultaneously displaying the early activation marker CD69, compared to less than 2% double-positive in other T cell types from healthy donors (Fig. 4c). Additionally, DNαβ T cells displayed higher gene expression scores for both exhausted CD8+ T cells and CD4+TNFRSF9+ Treg signatures11 than healthy donor T cells (Fig. 4d). DNαβ T displayed lower TILs signature scores compared to pan-cancer TILs30 (Fig. 4d), suggesting that these cells have overlapping and distinct cancer-associated transcriptional programs. Furthermore, DNαβ T cells demonstrated high T cell stemness (Fig. 4e), supporting that these T cells are in an activated state. However, DNαβ T cells did not express major cytotoxic and effector genes frequently found in CD8+ effector or exhausted T cells (e.g. GZMB and GNLY) (Fig. 4a) and displayed lower effector memory cells re-expressing CD45RA (Temra) scores than CD8+GZMB+ T cells from healthy donors (Fig. 4d). Although DNαβ T cells did not express master regulators of CD4+ Tregs (e.g. FOXP3), IL10 was expressed in DNαβ T cells with high specificity (Supplementary Fig. 4f), and patients with high number of DNαβ T cells showed elevated serum IL10 levels (Fig. 4f).

a Heatmap of scaled RNA expression of top 200 differentially expressed genes across all T cells. Genes indicate top marker genes of DNαβ T cells (purple) or selected marker genes of other T cells that have low expression in DNαβ T cells (green). b Bar graph of significant gene ontologies based on top 200 marker genes in DNαβ T cells analyzed by DAVID Gene ontology (P-value is derived from a Modified Fisher’s Exact Test). See Supplementary Data 5 for full list of differentially expressed genes. Immunoreg.: immunoregulatory. c Scatterplot of CD69 and CD137 surface protein expression in T cells from healthy donors and T-ALL patient samples at diagnosis. d Heatmap of z-normalized TIL signature scores11,12,29 for DNαβ T cells from T-ALL patients, T cells from normal donors and pan-cancer enriched TILs (ProjecTILs30). e T cell stemness scores for T cell types (CD8+naïve: n = 2593 cells; CD4+naïve: n = 5839 cells; CD4+memory: n = 4169 cells; CD8+GZMK+: n = 1356 cells; CD8+GZMB+: n = 1547 cells; DNαβ: n = 1481 cells). A one-way Anova test followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test was used for statistical analysis (p < 0.001 for all comparisons with DNαβ T cells). f Concentration of IL10 in serum of healthy donors (n = 2) and T-ALL patients at diagnosis and short-term treatment for group 1 (n = 4) and group 2 (n = 4) T-ALL patients. A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test with Holm correction was used for statistical testing and only significant comparisons are shown. g Regulon activity (pySCENIC31) in DNαβ T cells. h Boxplots showing DNαβ T cell transcriptomic signature scores for DNαβ T cells from T-ALL patients, T cells from healthy donors and pan-cancer enriched TILs (Project TIL30). i Boxplot showing percentage of T-ALL associated DNαβ T cells of T cells across treatment (diagnosis n = 4; prophase n = 3; treatment n = 1, remission n = 3). j Boxplots showing DNαβ T cell transcriptomic signature scores for DNαβ T single cells from healthy donors (PB, n = 14 cells) and group 2 T-ALL patients at diagnosis (PB, n = 901 cells) and prophase treatment (PB, n = 2040 cells). A one-way Anova test followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test was used for statistical analysis.

To further define gene regulatory relationships in DNαβ T cells, we analyzed regulon activity (transcription factor (TF) activity assessed by target gene expression)31 and observed high regulon activity for TFs associated with chronic T cell activation, including those active in CD8+ terminally exhausted cells and CD4+TNFRSF9+ Tregs, such as BATF and EOMES (Fig. 4g).

Distinct transcriptional program in DNαβ T cells

To assess if other T cell types may express transcriptional programs similar to the unique program identified in DNαβ T cells, we computed DNαβ T cell transcriptome and surface protein expression signatures based on the top differentially expressed genes (n = 20) and surface proteins (n = 10) across T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4g and Supplementary Data 5). The DNαβ T cells transcriptomic signature was highly specific for DNαβ T cells in T-ALL, when compared to healthy donor T cells and pan-cancer tumor-infiltrating T cells (TILs) (Fig. 4h). Notably, we detected DNαβ T cells in 10/15 patients at diagnosis at varying frequencies. However, only five patients displayed a significant difference in the DNαβ T cell signature score compared to healthy donor DNαβ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 4h), suggesting this score is indicative of a unique subset of T-ALL that is associated with DNαβ T cells (33%). For the following, we will refer to this subset of patients as group 2 (n = 5) compared to the rest of the patients in our cohort (group 1, n = 10) (Supplementary Data 6). In group 2 patients for whom longitudinal data were available, DNαβ T cells were still detectable after steroid prophase treatment (3/3) but were undetectable or less than 3% during further treatment (1/1) or at remission (2/2) (Fig. 4i). DNαβ T cells after prophase treatment displayed lower scores of the T-ALL associated DNαβ T cell signature compared to diagnosis, but still significantly higher compared to healthy donors (Fig. 4j), and displayed only 2.2% (CD69 + /CD137 + ) and 30.3% (CD69+) positive cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4i).

Increased abundance of non-classical monocytes in T-ALL

Besides altered T and B cell compartments, we observed an overall enrichment of myeloid cells (Fig. 1g), of which non-classical (NC) monocytes were significantly overrepresented in T-ALL at diagnosis compared to the healthy donor immune microenvironment as assessed by differential MiloR neighbourhood abundance25 (Fig. 5a,b). This was also confirmed by comparing to pediatric healthy donors (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Abundance of NC monocytes was reduced a few days after start of treatment and at normal frequencies in remission samples (Fig. 5c). In contrast to classical monocytes, NC monocytes expressed FCGR3A (encoding CD16) and CX3CR1 (Fig. 5d) and are thought to play a role in adhesion and migration32,33,34. Surprisingly, NC monocyte abundance was highest in T-ALL patients with DNαβ T cells, while atypical memory B cells were detected at similar abundance across the two T-ALL groups and were not correlated with NC monocytes or DNαβ T cells abundance (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 5b).

a Distribution of myeloid cell types in healthy donors (BM: n = 2, PB: n = 2) and T-ALL patients (diagnosis: BM: n = 5, PB: n = 10; prophase: PB: n = 6; treatment: PB: n = 2, remission: PB: n = 6). b Log2 fold changes of differential neighborhood abundance assessed by MiloR25 comparing healthy donors (n = 4) and T-ALL patients at diagnosis (n = 15). MiloR neighborhoods (n = 1680, where each neighborhood contains on average 31 cells) are grouped by myeloid cell type. Colors indicate an enrichment (red) or depletion (green) of myeloid cell type in T-ALL if more than half of the neighborhoods were significantly enriched/depleted (spatial FDR < 0.1). c Boxplot showing ratio of NC/C monocytes for healthy donors (BM: n = 2, PB: n = 2) and T-ALL patients (diagnosis: BM: n = 5, PB: n = 10; prophase: PB: n = 6; treatment: PB: n = 2, remission: PB: n = 6). An unpaired t-test (left) or a one-way Anova test followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test (right) was used for statistical analysis and only significant comparisons are shown. d Bubble heatmap showing normalized gene expression (left) and surface protein expression (right) of canonical myeloid marker genes or proteins in myeloid cells. e Boxplot showing ratio of NC/C monocytes (left) and percentage of atypical memory B cells (right) for healthy donors (n = 4) and T-ALL group 1 (n = 10) and T-ALL group 2 (n = 5) T-ALL patient samples at diagnosis. A one-way Anova test followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test was used for statistical analysis and only significant comparisons are shown. f Heatmap showing sum of interaction specificity weights for T cell, B cells, myeloid and leukemia cell-cell interactions in group 2 T-ALL patients (NATMI35).

To assess possible cell-cell interactions between malignant cells, monocytes, T cells and B cells of T-ALL patients with DNαβ T cells (i.e. T-ALL group 2), we predicted cell-cell communications using NATMI35 interaction analysis. Focusing on DNαβ T cells, we observed the most specific predicted interactions with NC monocytes as sender cells and DNαβ T cells as receiver cells (Fig. 5f). To further define this immune network, we assessed ligand activities using NicheNet36 in DNαβ T cells focusing on NC monocytes as sender cells. We detected several ligand-receptor interactions between NC monocytes and DNαβ T cells with known function in inhibitory T cell pathways (e.g. PDCD1, TIGIT), suggesting NC monocytes may contribute to the exhausted phenotype of DNαβ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

CXCL16 induces DNαβ T cell transcriptional programs upon chronic activation in vitro

Among the interactions between NC monocytes and DNαβ T cells, the CXCL16-CXCR6 interaction was among the top five interactions with high specificity (Fig. 6a), and we also detected ligand activity of CXCL16 in DNαβ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c). CXCR6 was highest expressed in DNαβ T cells and detected at lower levels in CD8+MAIT, DNγδ, and CD8+GZMK+ T cells (Fig. 6b). As membrane-anchored CXCL16 can be cleaved by the disintegrin-like metalloproteases ADAM10 and ADAM17 resulting in soluble CXCL16 (sCXCL16)37,38, we also evaluated their expression in the T-ALL immune microenvironment. The CXCR6 ligand CXCL16 and its proteases ADAM10 and ADAM17 were highest expressed in NC monocytes compared to other cell types and specifically the expression of the proteases was higher in NC monocytes at diagnosis than in healthy donors and T-ALL at remission (Fig. 6b,c). Therefore, we postulated that sCXCL16 may be increased in the T-ALL patients with high percentage of NC monocytes. We quantified sCXCL16 levels in serum of healthy donors and T-ALL patients at diagnosis and indeed detected a significant increase of sCXCL16 in samples with >60% NC monocytes compared to samples with <30% NC monocytes (Fig. 6d).

a Interaction specificity weights of ligand-receptor interactions between NC monocytes and DNαβ T cells in T-ALL group 2 patients (NATMI35). b Bubble heatmap showing expression of genes involved in the CXCL16-CXCR6 axis in group 2 T-ALL patients at diagnosis. c mRNA expression of CXCL16, ADAM10 and ADAM17 in peripheral blood NC monocytes for group 2 T-ALL patients at diagnosis (n = 1603 cells), prophase (n = 740 cells) and remission (n = 103 cells) and healthy donors (n = 168 cells). A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test with Holm correction was used for statistical testing and only significant comparisons are shown. d Barplot showing concentration of soluble CXCL16 in serum of primary peripheral blood samples grouped by percentage of NC monocytes of monocytes. Data are presented as mean values +/- SEM (0-30%: n = 3, 30-60%: n = 2, 60–100%: n = 2) including technical duplicates. A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test with Holm correction was used for statistical testing and only significant comparisons are shown. e Experimental approach for in vitro induction of CD8low cells. CD8+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads and cultured with 150 U/ml IL-2 alone or IL-2 with 100 ng/ml CXCL16 for 7 days. Upon harvest, CD8high, CD8mid and CD8low CD3+ T cells were sorted and processed for low-input RNA-seq using the Smart-seq2 protocol39. f, Heatmap of scaled normalized expression of low-input RNA-seq using the Smart-seq2 protocol of genes in the DNαβ T cell transcriptome score for in vitro induced CD8high (n = 3), CD8mid (n = 4) and CD8low T cells at day7 in the absence (n = 2) or presence (n = 4) of CXCL16. g Heatmap of regulon activity (RScenic31) of top DNαβ T cell regulons shown in Fig. 4g for sorted CD8high, CD8mid and CD8low T cells from cultured CD8+ T cells harvested at day 7. h Boxplots showing regulon activity for in vitro induced CD8low T cells at day 7 in the presence or absence of CXCL16 shown in (g) for each hierarchical cluster (n = 3, n = 3 and n = 5 regulons in each cluster, respectively). A paired t-test was used for statistical analysis; n.s.: not significant.

We next hypothesized that CXCL16 may contribute to the specific transcriptional program that we had identified in DNαβ T cells. To investigate this in vitro, we subjected CD8+ T cells to chronic activation with anti-CD3/CD28 beads and IL-2 in the absence or presence of CXCL16. We used CD8+ T cells postulating that DNαβ T cells derived from CD8+ T cells based on their low expression of CD8B and their shared TCR usage with CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3b,i). In addition, while chronic activation of naïve CD8+ T cells from healthy donors resulted in a sizable population of CD4-CD8- T cells with high expression of key DNαβ T cell genes such as GZMK and EOMES as analyzed by RT-qPCR in vitro, CD4+ T cells did not (Supplementary Fig. 6). To study the transcriptional programs and regulon activities of these in vitro induced DN T cells, we sorted for CD8high, CD8mid and CD8low cells followed by low-input RNA-seq using the Smart-seq2 protocol39 (Fig. 6e). After 7 days of anti-CD3/CD28 and IL-2 activation, CD8low T cells cultured in the presence of CXCL16 showed increased expression of several genes present in the DNαβ T cell transcriptomic signature compared to CD8+ T cell populations cultured without CXCL16 (Fig. 6f). Key TFs expressed in DNαβ T cells from T-ALL patients (MYB, PRDM1 and EOMES) displayed highest regulon activity in CD8low T cells with or without CXCL16 (Fig. 6g,h). Additionally, IRF2, IRF3 and BATF regulon activity increased upon addition of CXCL16 (Fig. 6g,h). Together, these results suggest that in vitro generated CD8low T cells share characteristics with DNαβ T cells and that CXCL16 induces the BATF/IRF2/IRF3 regulatory network in these CD8low T cells.

Inhibiting Rap1 signaling induces apoptotic priming in T-ALL

We next examined transcriptional differences between malignant cells from the two T-ALL groups, hypothesizing that differential engagement of regulatory gene networks under immune selective pressure may underlie functional divergence between the two groups. Unbiased differential expression analysis in malignant cells revealed that genes higher expressed in group 2 T-ALL patients compared to group 1 T-ALL patients were involved in several processes related to mature T cell receptor signaling, T cell activation, adhesion, and Rap1 signaling (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Data 7). Genes associated with Rap1 signaling included ITGAL (encoding CD11a) and ITGB2 (encoding CD18) as well as other genes such as LAT, which plays a crucial role in T cell activation (Supplementary Fig. 7a,b)40. The integrins CD18 and CD11a together form LFA-1, for which CD54 is the main ligand. LFA-1 plays a role in T cell/antigen presenting cell (APC) interactions and is regulated through Rap1 signaling41. LFA-1 interactions were enriched between NC monocytes and malignant cells in T-ALL group 2 patients, including ICAM1 (encoding CD54) with ITGB2/ITGAL (encoding CD18/CD11a) (Fig. 7b). T-ALL group 2 patients displayed significantly higher surface protein expression of CD54 in NC monocytes and CD11a and CD18 in malignant cells, respectively, compared to cells from group 1 T-ALL patients (Fig. 7c,d). Notably, CD54 surface expression decreased after steroid prophase and showed similar levels as in healthy donors at remission (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Together, this suggests that malignant cells from T-ALL group 2 patients may engage Rap1 signaling.

a Bar graph of significant gene ontologies based on the top 100 differentially expressed genes in malignant cells of group 2 T-ALL patients compared to group 1 T-ALL patients (Supplementary Data 7) as analyzed by DAVID Gene ontology. P-value is derived from a Modified Fisher’s Exact Test. Immunoreg: Immunoregulatory interactions between a lymphoid and non-lymphoid cell. b Ligand-receptor interactions (NATMI35) between NC monocytes and malignant cells from T-ALL group 2 patients. c, d Violin plots showing surface protein expression of CD54 in NC monocytes from healthy donors (n = 102 cells (BM), n = 168 cells (PB)), T-ALL group 1 (n = 881 cells (PB), n = 1531 cells (BM)) and T-ALL group 2 (n = 1603 cells (PB), n = 1226 cells (BM)) at diagnosis (c), and CD11a and CD18 in malignant cells from T-ALL group 1 (n = 4 (BM), n = 6 (PB)) and T-ALL group 2 (n = 1 (BM), n = 4 (PB)) patients (downsampled to 300 cells/sample) at diagnosis (d). A one-way Anova test followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test (c) or an unpaired t-test (d) was used for statistical analysis. e Viability as assessed by CellTiter-Glo assay upon GGTI-298 treatment in T-ALL cell lines (Jurkat, HPB-ALL and CCRF-CEM) for three days and two primary T-ALL samples from group 2 (P8 and P14) for five days. Viability is normalized to vehicle control DMSO. Each dot represents a data point from an independent replicate. Bars and error bars represent the mean and SEM of triplicates. f Heatmap of normalized cytochrome c- cells upon 12-hour treatment with GGTI-298 or vehicle DMSO in T-ALL cell lines Jurkat, HPB-ALL and CCRF-CEM. g Most synergistic area score (MSA) (Bliss, SynergyFinder75) of combination treatment with Rap1 inhibitor GGTI-298 and indicated drugs in T-ALL cell lines (Jurkat, HPB-ALL and CCRF-CEM) and two primary T-ALL patients samples from group 2. MSA > 10 is considered strongly synergistic (dashed line). Each dot represents the MSA and error bars indicate 95% confidence interval. h Dose-response curves (CellTiter-Glo assay) of T-ALL cell lines (Jurkat and HPB-ALL) and primary T-ALL P14 treated with various concentrations of GGTI-298 and navitoclax (top) or venetoclax (bottom) for three or five days, respectively. Viability of GGTI-298 without addition of BCL2 inhibitors were normalized and set to 100%. Most synergistic area score (MSA) (Bliss, SynergyFinder75) is shown (see (g)). Each dot represents the mean and error bars represent SEM of three independent replicates.

Rap1 signaling is involved in multiple T cell processes including normal T cell activation, cytoskeleton reorganization and adhesion41. To investigate the role of Rap1 signaling as a novel therapeutic target in T-ALL, we treated the T-ALL cell lines Jurkat, HPB-ALL and CCRF-CEM and two patient samples from group 2 (P8 and P14) with the geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor GGTI-298 that inhibits Rap1 signaling. All three cell lines and the patient samples were sensitive for Rap1 inhibition as illustrated by decreased cell viability upon treatment with GGTI-298 (Fig. 7e). In addition, we observed increased apoptotic priming in the presence of Rap1 inhibition in the T-ALL cell lines Jurkat and HPB-ALL, and to a lesser extent in CCRF-CEM (Fig. 7f), as assessed by BH3 profiling42,43. We next evaluated whether Rap1 inhibition could enhance the efficacy of pro-apoptotic agents. To this end, we treated T-ALL cell lines and primary patient samples with GGTI-298 in combination with navitoclax (BCL2/BCL-XL inhibitor) and venetoclax (selective BCL2 inhibitor). Combination treatment with GGTI-298 resulted in synergistic effects in two cell lines and one primary sample (Fig. 7g,h and Supplementary Fig. 7d), suggesting that a subset of T-ALL may be particularly sensitive to dual targeting of Rap1 signaling and BCL2-mediated survival pathways.

Distinct transcriptional programs in leukemia cells correlate with outcome

We hypothesized that the leukemia-intrinsic transcriptional rewiring observed in group 2 patients reflects adaptive cellular states that may directly influence treatment response and therapeutic resistance. To this end, we defined T-ALL gene scores based on the top 15 differentially expressed genes between leukemia cells in group 1 and group 2 (Fig. 8a). Importantly, the corresponding surface proteins present in these signatures were also differentially expressed (Fig. 8b). The score for T-ALL group 2 (i.e. representative of one-third of T-ALL patients with high abundance of DNαβ T cells and NC monocytes), included several genes involved in T cell activation and immune processes (including CD69, HLA-B and CD52). To validate our scores in an independent T-ALL dataset of patients who received the same treatment, we analyzed bulk RNA-seq data of 14 patients44, and in addition analyzed matched clinical immunophenotyping to investigate DNαβ T cell abundance. We used the percentage of CD4-CD8-CD7- T cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirates at time of diagnosis to determine the frequency of DNαβ T cells, as TCRαβ/γδ flow data was not available and inclusion of CD7 was sufficient to distinguish DNαβ T cells from DNγδ T cells (Supplementary Figs. 4e and 8a). We detected more than 3% CD4-CD8-CD7- T cells in three out of the 14 patients. These patients, annotated as group 2 by flow, displayed significantly higher group 2 scores but no significant differences in group 1 scores by RNA-seq (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Fig. 8b). These results validate that the group 2 score is indicative of a subset of T-ALL patients ( ~ 20–35% of patients) with a remodeled immune microenvironment associated with the presence of DNαβ T cells.

a Heatmap of scaled normalized RNA expression of top 15 genes differentially expressed in leukemia cells of group 1 T-ALL patients and group 2 T-ALL patients. A score for each group was computed based on the sum of expression of these genes. b Violin plots showing surface protein expression of genes present in the T-ALL transcriptomic scores shown in (a) for malignant cells from T-ALL group 1 (n = 4 (BM), n = 6 (PB)) and T-ALL group 2 (n = 1 (BM), n = 4 (PB)) patients (downsampled to 300 cells/sample) at diagnosis. An unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis; n.s.: not significant. c Group 2 scores for primary T-ALL patient samples of an independent dataset (GSE18115744) split by percentage of CD4-CD8-CD7- T cells analyzed by flow cytometry ( < 3% n = 11, >3% n = 3, see Supplementary Fig. 8b). A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for statistical analysis. d Visualization of T-ALL oncogenic groups ordered by group 2 scores for patient samples from the TARGET cohort (n = 265). A chi-square test comparing lower tertile and upper tertile was used for statistical analysis. e Kaplan-Meier curve of event-free survival (EFS, n = 580) and overall survival (OS, n = 597) of MRD low T-ALL patients from the Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program dbGaP phs002276.v2.p1 grouped based on score for group 2. A log-rank test was used for statistical analysis to compare high versus low score groups, also see Supplementary Fig. 8c. f Illustration of the remodeled immune system and leukemic Rap1 signaling in group 2 T-ALL patients.

Next, we investigated whether this specific T-ALL subgroup was associated with certain genetic subtypes based on recurrent rearrangements13,14,15. Analysis of an independent dataset from the Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) initiative (n = 265) revealed that LMO2/LYL1 (immature thymocyte stage) and TAL1/2 (late-cortical stage) rearrangements15 were enriched for high group 2 scores (Fig. 8d). In contrast, patients with TLX1/3 rearrangements were depleted from high group 2 scores (Fig. 8d). Of note, based on oncogene expression, TLX3 expression was only detected in group 1 T-ALL samples compared to TAL1/2 expression, which was predominant in group 2 T-ALL patients in our patient cohort (Supplementary Data 6).

We then assessed the association of our gene scores with outcome in an independent public RNA-seq dataset of 1249 pediatric T-ALL patients, who were enrolled on COG AALL0434 (Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program, phs002276). The strongest independent predictor of relapse in T-ALL in the modern era is response to therapy, evaluated by end-induction minimal residual disease (MRD)45. We therefore investigated whether the group 2 expression score would define a group of patients with adverse outcome independent of MRD. Strikingly, patients with high group 2 score showed significantly worse overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) specifically in MRD low patients (Fig. 8e). No significant differences were observed in MRD high patients or when using group 1 expression scores (Supplementary Fig. 8c). These analyses indicate that a specific patient subgroup that is characterized by Rap1 signaling in leukemia cells and a remodeled immune network with high serum levels of CXCL16, NC monocytes and DNαβ T cells, has worse OS and EFS in MRD low pediatric T-ALL patients (Fig. 8f).

Discussion

In this study, we performed an integrated analysis of single-cell transcriptome, surface protein expression, and immune repertoire to unravel the cellular composition of immune cells in pediatric T-ALL across treatment and identified a T-ALL subgroup with high abundance of non-malignant CD4-CD8-TCRαβ T cells and non-classical monocytes. Leukemia-cell intrinsic rewiring in these patients was associated with mature T cell activation programs and Rap1 signaling, of which its inhibition resulted in increased apoptotic priming. A computed gene expression score that is indicative of this subgroup revealed an association of patients with higher scores and adverse clinical outcome in MRD low patients in an independent cohort. Of note, high expression of this signature does not affect outcome in MRD high patients. These findings suggest that using this signature score may allow to identify a subgroup of patients with low MRD that face adverse outcome using the current standard of care treatment regimens.

Chronic tumor-antigen exposure and an immunosuppressive microenvironment can induce dysfunctional T cell states46. TILs may compromise immune surveillance and contribute to a permissive microenvironment that allows cancer cells to persist or re-emerge. Clinically, this dysfunction may limit the effectiveness of immune-mediated clearance following therapy and undermine the durability of MRD-negative remission, highlighting the need to evaluate immune fitness alongside tumor burden in relapse risk assessment. Dysfunctional CD8+ TILs show high surface expression of inhibitory receptors, including PD-1 and TIM-310,47, while immunosuppressive regulatory CD4+ TILs demonstrate high CTLA-4 expression and secrete IL1010,11. Importantly, the DNαβ T cells in T-ALL identified here shared some of the TILs dysfunctional and immunosuppressive features. For example, we found high expression of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL10, inhibitory receptor TIGIT and identified BATF as a central transcriptional regulator. BATF, a member of the AP-1/ATF transcription factor superfamily, has been shown to be a key regulator of highly suppressive activated Tregs in the tumor microenvironment48. Moreover, BATF has been previously implicated in immune modulation across multiple contexts, including epigenetic reprogramming of NK cells in AML49 and CAR T-cell exhaustion50,51. Notably, recent findings suggest that BATF activity can be therapeutically targeted using bromodomain inhibitors to mitigate T-cell exhaustion52. These data support further investigation of BATF as a key mediator of T cell impairment in leukemia and as a potential therapeutic target to enhance immune surveillance.

DNαβ T cells have been described in a few other disease contexts, including some chronic infections and autoimmune diseases53,54,55. Expansion of DNαβ T cells is observed in patients with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) with mutated FAS56. These FAS controlled DNαβ T cells share some characteristics with the DNαβ T cells identified here, such as high expression of EOMES, MYB and IL10 and surface expression of CD57, CD38 and CD45RA. It is conceivable that host-intrinsic immunomodulatory defects impair the patient’s ability for effective immune surveillance during leukemia development. Interestingly, some of the genes with germline mutations in ALPS have been described as somatic mutations in hematologic malignancies (such as STAT3 in lymphoid malignancies57). Further studies leveraging large datasets that include germline sequencing are needed to understand whether the observed immune microenvironmental alterations may be linked to an underlying immunomodulatory defect in this subgroup of patients.

Very little is known about the presence and role of DNαβ T cells in cancer. DN T cells have been detected in some solid tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma58, and described as a heterogeneous population that includes GZMB+ highly cytotoxic, inflammatory and regulatory DN T cells59,60. Given the predominance of DNγδ T cells in these scenarios, it is difficult to compare with the DNαβ T cells we observed in T-ALL. Interestingly, it has recently been shown that persistent CD19 targeting CAR-T cells in B-ALL become CD4/CD8 negative61. Similar to the DNαβ T cells identified here, these persisting DNαβ CAR-T cells expressed high levels of GZMK, TIGIT and EOMES while lacking the effector genes GZMB and KLRD1. It is unclear though, which host factors or antigens may have contributed to their persistence and their CD4-CD8- phenotype. While our findings indicate that DNαβ T cells likely originate from CD8⁺ T cells, additional studies are needed to elucidate their precise developmental origin. Additionally, the role of other T cell subtypes including NKT, naïve and memory T cells in the leukemia microenvironment, which were present at reduced frequencies at time of diagnosis, warrants further investigation.

We defined a role for non-classical monocytes in the T-ALL immune microenvironment. We detected increased abundance of NC monocytes in almost all T-ALL patients, with highest abundance found in patients with DNαβ T cells. Increased relative abundance of NC monocytes has been described in pediatric B-ALL5 and other hematologic malignancies62, and their presence has been associated with treatment failure. Our data suggest that NC monocytes play a key role in supporting DNαβ T cells. We predicted a possible interaction between CXCL16 secreted by NC monocytes and its receptor CXCR6 on DNαβ T cells as one of the top scoring interactions between the two cell types and detected increased levels of soluble CXCL16 in serum samples of patients with high abundance of NC monocytes. The CXCL16-CXCR6 axis has been shown to be involved in providing critical signals to CXCR6+CD8+ T cells thereby increasing their survival and expansion63. Additional studies are needed to understand how this axis mechanistically affects DNαβ T cell survival, activation, effector and regulatory function. Notably, NC monocytes also send and receive signals to/from other immune subtypes such as classical monocytes, myeloid dendritic cells, and DNαβ T cells.

In addition to non-classical monocytes, we observed several B cell subsets with altered frequencies in T-ALL at diagnosis, including an enrichment of atypical memory B cells and a reduction of naïve and progenitor B cells in bone marrow samples. In our study, AtM B cells were not enriched in the subgroup of patients with increased frequency of DNαβ T cell or non-classical monocytes. Further studies are needed to understand whether atypical memory B cells affect treatment outcome as demonstrated for AML9 and their role as antigen-presenting cells. Moreover, dedicated longitudinal bone marrow sampling would provide more insights into how the the loss of progenitor B cells in T-ALL evolves over the course of the disease.

Notably, the remodeled immune microenvironment was associated with leukemia-cell intrinsic rewiring. Leukemia cells of patients with high frequency of DNαβ T cells and NC monocytes in their immune microenvironment demonstrated gene expression programs of mature T cell activation and Rap1 signaling. We showed that inhibition of Rap1 using the geranylgeranyl transferase inhibitor GGTI-298 induces apoptotic priming. This finding is reminiscent of other data in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and AML demonstrating that sensitization to venetoclax requires inhibition of protein geranylgeranylation64. Our findings suggest that the mature T-ALL subtype we describe here may be amenable to combination therapies of BCL-2/BCL-XL inhibitors with Rap1 inhibition as a novel treatment strategy. Combining gene expression analysis of leukemia cells (score 2), immunophenotyping (% DNαβ T cells and NC monocytes) and T-ALL subgroup classification (e.g. TAL1) would improve identifying those patients for which BCL2/BCL-XL inhibitors would be beneficial. Further studies are needed to understand the role of Rap1 signaling for initiation and/or maintenance of the remodeled immune microenvironment and potential cellular interactions between leukemia cells and DNαβ T cells and NC monocytes.

In contrast to other acute leukemias including AML or B-ALL, for which defined genetic events confer clinically relevant risk stratification, there is no consensus on high-risk genetic events in T-ALL or how to adapt treatment in the presence of defined genetic events13. In this study, we identified a subgroup of pediatric T-ALL patients with inferior survival that is characterized by mature T cell activation signatures including Rap1 signaling and several immune cell alterations reflective of chronic activation. Further studies are needed to understand how DNαβ T cells and/or NC monocytes mediate worse outcome in the setting of low MRD. These studies will need to include careful kinetic investigations of the dynamic changes of these immune cell populations during treatment, perturbation of this immune network or depletion of key cellular components such as DNαβ T cells and/or NC monocytes in in vivo model systems to investigate exactly how they impact disease biology and patient outcome. It is conceivable that even in cases of MRD-negative T-ALL, DNαβ T cells through their interactions with other immune cells and/or cytokine production contribute to an immunosuppressive microenvironment that facilitates impending relapse by enabling leukemic cells to evade immune surveillance and create a permissive niche that facilitates leukemic dormancy and eventual re-emergence. Notably, some patients presenting with late relapse demonstrate the same clone as at time of diagnosis, which may be due to an immunosuppressive microenvironment that facilitates reappearance of the same leukemia. Further studies of the co-evolution of leukemia and immune microenvironment are needed to understand the underlying mechanisms of leukemia reoccurrence in these patients. While MRD negativity is currently the strongest predictor of favorable outcomes, this paradigm may be subverted in patients where the immune system fails to maintain long-term control of residual disease. Integrating immune profiling into MRD evaluation may refine relapse prediction and reveal actionable targets for immunotherapeutic intervention, even in patients who meet current thresholds for deep molecular remission. Importantly, some of the epitopes expressed on leukemia cells, DNαβ T cells and/or NC monocytes in this network are under active investigation as immunotherapeutic targets (e.g. CD3865,66, CD8167,68, TIGIT69,70,71 and TIM371,72). These may thus not only provide ways to investigate their relevance for disease biology and treatment outcome but may ultimately lead to their development as novel therapeutics.

Methods

Human samples

Banked bone marrow and/or blood samples from children with de novo T-ALL who had consented to biobanking for future research (Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC); protocol 06-078), were provided in a de-identified manner. All T-ALL patients in this cohort received multi-agent chemotherapy treatment including dexamethasone, doxorubicin, vincristine, and asparaginase for induction. Age (median age 11 years), immunophenotype, karyotype information, mutational information (rapid heme panel73), MRD status and enrollment on DFCI protocol 16-001 (NCT00400946 Treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Children) are listed in Supplementary Data 1. Mononuclear cells from healthy donors were obtained from Research Blood Components (peripheral blood) or from AllCells (bone marrow). This study was approved by the DF/HCC Institutional Review Board.

Human primary T cell cultures

Mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood (Crimson) using Ficoll Paque Plus (Fisher Scientific, 45001750) according to protocol. Subsequently, CD8+ T cells were isolated from mononuclear cells using the EasySep CD8+ Positive Selection kit (StemCell Technologies, 17853). To isolate CD4+ T cells, we performed CD4+ positive selection using the EasySep Release Human CD4 Positive Selected Kit (StemCell Technologies, 17752) followed by CD3+ isolation using the Human T Cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies, 19051). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were cultured in XVivo 15 (Fisher Scientific, 04-418Q) supplemented with 5% Human serum (Sigma Aldrich, H4522-100ML) and 150 U/ml IL2 (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-097-743). T cells were activated by Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Life Technologies, 11132D) for 10 days followed by 4 days of culture without Dynabeads. Media and cytokines were refreshed every 2 days.

Human cell lines

T-ALL cell lines Jurkat (ATCC, TIB-152), HPB-ALL and CCRF-CEM (Broad Institute CCLE) were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11875-085) with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 26140-079), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140163), 1% glutamine (Life Technologies, 25030164), 1% NEAA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11140-050), 1% Sodium Pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11360-070), 25 mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher, 15630-080) and 55 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21985-023). Cell lines were verified by DNA fingerprinting with small tandem repeat profiling at the DFCI Molecular Diagnostics Core (https://moleculardiagnosticscore.dana-farber.org/human-cell-line-identity-verification.html) and were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Cell preparation and single-cell multi-omics library sequencing (10x Genomics)

Cryopreserved mononuclear cells from peripheral blood or bone marrow were thawed in prewarmed RPMI 1640 (ThermoFisher Scientific, 11875-085) supplemented with 10% FBS (ThermoFisher Scientific, 26140-079) and 55 nM 2-Mercaptoethanol (ThermoFisher Scientific, 21985-023) by a serial dilution according to protocol (10x Genomics). Mononuclear cells were pelleted by centrifugation (400 g at 4 °C) and supernatant was discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1% BSA in PBS and incubated with Human TruStain FcX Blocking Solution (Biolegend, 422302) for 10 min on ice. After incubation, FITC-conjugated anti-human CD45 (Biolegend, 368508) and PE-conjugated anti-human CD7 (Biolegend, 395604) were added at a final dilution of 1/20 and incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark. In addition, samples were either stained with a custom anti-human Totalseq-C cocktail containing 204 CITE-seq antibodies (5x diluted compared to recommended concentration) (Biolegend, custom order, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 2) or with a hashtag antibody (final concentration 0.125ug/million cells) (Biolegend, 394661, 394663, 394667) to pool samples after sorting74 (Supplementary Data 3). After incubation, cells were washed three times in 2.5 ml PBS with 1% BSA at 400 g for 5 min at 4 °C. Finally, samples were resuspended in PBS with 1% BSA supplemented with 0.1μM DAPI for cell sorting.

Viable DAPI-CD45high immune cells and DAPI-CD45midCD7+ malignant cells were sorted on an BDFacs Aria II sorter. In case of T-ALL patient samples, immune cells and malignant cells were pooled after sorting to have at least > 50% immune cells per sample. After sorting, cells that were stained with the Totalseq-C antibody cocktail were centrifuged and resuspended in PBS with 0.4% BSA and directly loaded on the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller. Samples that were stained with hashtag antibodies were pooled and stained with the Totalseq-C antibody cocktail as described above and subsequently loaded onto the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller.

Generation of the gene expression library, surface proteins library and the VDJ library was done according to the 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM Single Cell V(D)J Reagent Kits with Feature Barcode technology for Cell Surface Protein v1.1 (10x Genomics: Chromium Next GEM #1000165, Library Construction #1000020, VDJ B #1000016, VDJ T #1000005, Feature Barcoding #1000080, Chip G #1000120, Index T Set A #1000213, Index N Set A #1000213) or v2 (10x Genomics: Chromium Next GEM #1000263, Library Construction #1000190, VDJ B #1000253, VDJ T #1000252, Feature Barcoding #1000541, Chip K #1000286, Index TT Set A #1000215, Index TN Set A #1000250) protocol (Supplementary Data 3). Transcriptome (5’), surface protein expression and VDJ sequencing libraries were assessed by Agilent Tapestation and quantified using Qubit dsDNA before sequencing. 10x Genomics libraries were paired-end sequenced on a Nextseq500 system (Illumina) with the following read configurations for the transcriptomic and feature barcoding libraries: 26-8-0-58 bp and for the immune repertoire libraries 26-8-0-134 bp.

In vitro generation of DN T cells

To generate CD4-CD8- T cells in vitro, CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells were cultured and activated using Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Life Technologies, 11132D) for 10 days on beads followed by 4 days off beads supplemented with fresh 150 U/ml IL-2 (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-097-743) every 2 days. To investigate the effect of sCXCL16 on T cells in vitro, CD8+ T cells were cultured in the absence and presence of 100 ng/ml CXCL16 (R&D, 976CX025). On day 7, 14 and 21, T cells were analyzed for CD3, CD4 and CD8 surface expression. T cells were stained for 30 min at 4 °C with FITC-conjugated anti-human CD4 (Biolegend, 317408), PE-conjugated anti-human CD8 (Biolegend, 301008) and APC-conjugated anti-human CD3 (Biolegend, 300312) at a final dilution of 1/20 in PBS + 1% BSA. Cells were washed twice at 4 °C and 0.1μM DAPI was added before proceeding to sort on a Sony Sorter SH800.

For qPCR experiments, CD4+CD8- T cells, CD4-CD8+ and CD4-CD8- T cells were sorted on a Sony Sorter and processed for RNA isolation. RNA was isolated from sorted T cells using RNeasy microkit (Qiagen, 74004) according to protocol. RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix for qRT-PCR (Invitrogen, 11752050) and used for qPCR experiments using SYBRgreen MasterMix (Applied Biosystems, 4309155). Experiments were performed in duplicates. GAPDH (Fw: AATCCCATCACCATCTTCCA, Rv: TGGGACTCCACGACGTACTCA) was used as housekeeping gene to assess expression of EOMES (Fw: AGGCGCAAATAACAACAACACC, Rv: ATTCAAGTCCTCCACGCCATC), GZMK (Fw: CTGTGGTTTTAGGCGCACAC, Rv: GTTTTGCGGCTGTTTGAAGC), TBX21 (Fw: AGGATTCCGGGAGAACTTTG, Rv: CCCAAGGAATTGACAGTTGG) and HAVCR2 (Fw: CTGCTGCTACTACTTACAAGGTC, Rv: GCAGGGCAGATAGGCATTCT).

For low-input RNA-seq experiments, cells were stained with CD3, CD4 and CD8 as described above and minipools of 100 viable CD3+ cells (DAPI negative, singlets) were sorted for CD4+, CD8high, CD8mid and CD8low cells into a 96-well plate containing 10ul lysis buffer (TCL buffer (Qiagen)) supplemented with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies). Plate based full-length RNA-seq libraries were processed according to the Smart-seq2 protocol39. We performed RNA purification (2.2x RNA-SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter, A63987), first strand cDNA synthesis (Maxima RNase H-minus RT and Buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific, EP0752) and 1μM biotinylated TSO (5′-/5Biosg/AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTACATrGrG+G-3′), PCR pre-amplification (2x KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix and 0.1μM ISPCR primer (5’-/5Biosg/AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3’) and cDNA purification (0.8x DNA-SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter, A63881)39. 1 ng of cDNA from each sample was carried forward for tagmentation using the Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, FC-131-1096). Adapter ligated fragments were amplified and purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, A63881). DNA quantification was done using the Qubit High Sensitivity dsDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Q32854) and library quality was assessed by a High Sensitivity D5000 Screen Tape on a 2200 Tape Station System (Agilent Technologies). Low input plate-based full-length RNA-seq libraries were paired-end sequenced (75 cycle NextSeq 500 High Output (Illumina)) on a NextSeq 500 System (Illumina) with an average sequencing depth of 8 million reads per sample.

Dose-response curves Rap1 inhibitor GGTI298

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, washed and resuspended in pre-warmed MEM-Alpha medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, 12571-063) supplemented with 10% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich, H4522-100ML). Cells were treated with DNase I at a final concentration of 4 U/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, D4513-1VL) and filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer (Fisher Scientific, 08-771-2). A total of 40,000 cells were seeded per well in MEM-Alpha medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, 12571063) supplemented with 10% human serum, 100 U/mL IL-2 (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-097-743), 20 ng/mL IL-7 (BioLegend, 581902), and 20 ng/mL IL-15 (BioLegend, 570302). Cells were cultured overnight prior to drug treatment.

Cells were treated for 3 days (T-ALL cell lines) or 5 days (primary T-ALL cells) at indicated concentrations of Rap1 inhibitor GGTI298 (MedChemExpress, HY-15871), navitoclax (MedChemExpress, HY-10087) and venetoclax (MedChemExpress, HY-15531). Cells were incubated in an opaque flat-bottom 96-well plate, after which CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega, G7572) was performed according to manufacturer protocol and measured on a SpectraMax M5. Synergy was assessed using SynergyFinder v3 (https://synergyfinder.fimm.fi/)75.

BH3 profiling

To assess apoptotic priming upon Rap1 inhibition, T-ALL cell lines were treated with 1μM or 5μM GGTI298 (MedChemExpress, HY-15871) or vehicle DMSO for 12 hours and subjected to BH3 profiling according to protocol42,43. In short, DMSO- and GGTI298 treated cells were stained with 1:100 live/dead Zombie Aqua (Biolegend, 423101), resuspended in MEB2-P25 buffer (150 mM Mannitol (Sigma-Aldrich, M9647), 10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5 (Sigma-Aldrich, H4034), 150 mM KCl (Sigma-Aldrich, P9541), 1 mM EGTA (Sigma-Aldrich, E3889), 1 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, E6758), 0.1% BSA (VWR, 100182-742), 5 mM Succinate (Sigma-Aldrich, S3674), 2.5 g/L Polaxamer 188 (Fisher, MT61161RM) and permeabilized with 0.002% digitonin (ThermoFisher Scientific, BN2006). Permeabilized cells were exposed to varying concentrations of synthetic BH3 peptides (BIM, BAD, HRK, MS1, and FS1) (Vivitide), 1% DMSO as negative control, or 20uM Alamethicin (Enzo, BML-A150-0005) as positive control for 1 hour at RT. To assess dependences, specific peptides were included: BIM peptide binds BAX and BAK, BAD (binds BCL-2, BCL-w, and BCL-xL), HRK (binds BCL-xL), MS1 (binds MCL-1), and FS1 (binds BFL1). Cells were then fixed using 10% buffered formalin for 10 minutes, followed by neutralization by N2 buffer (1.7 M Tris base (Fisher, BP381), 1.25 M Glycine pH 9.1 (Fisher, BP381)) for 5 min at RT. Subsequently, cells were stained with a final concentration of 200 ng/ml anti-cytochrome c (Biolegend, 612310) or IgG1 antibody (Biolegend, 400136) in 10X Perm/Wash buffer (BD Bioscience, 554723) at 4 °C overnight, after which flow cytometry analysis was performed on a BD LSR Fortessa analyzer. Level of cytochrome c was measured as a readout for sensitivity to the BH3 peptides. Analysis was performed using FlowJo, where the cytochrome c+ gate was drawn based on the negative DMSO control ( > 90% cytochrome c retention) and the positive Alamethicin control (0% cytochrome c). Relative cytochrome release was calculated as follows: 1 – [(well of interest – positive control) / (negative control – positive control)].

ELISA

The Human IL-10 ELISA (Biolegend, ab100549) assay was performed according to protocol to measure IL-10 levels in serum samples from healthy donors and patient samples (diluted 2-10x). Samples were tested in triplicates and measured using a microplate reader SpectraMax M5. Human CXCL16 was measured in duplicates using a multiplex assay (BosterBio, #SEST004-P0004) by BosterBio (https://www.bosterbio.com/ Pleasenton, CA).

Single-cell multi-omics data processing and quality control

Sequencing reads were demultiplexed and aligned to the GRCh38-3.0.0 reference genome using Cell Ranger 6.1.076. Python package Scrublet was applied to all samples to calculate a doublet score77. Samples formed a bimodal distribution, and the threshold was set accordingly to remove doublets. In addition, we applied DropletQC to exclude empty droplets and damaged cells based on their nuclear fraction78. Further downstream processing was done using Seurat 4.3.0 in R24,79. Cells that had > 10% mtDNA, <200 genes, or > 5500 genes in the transcriptome were removed. In addition, we removed cells with > 30,000 antibody counts and with <100 antibodies detected. The remaining cells were further processed for normalization. Transcriptomic counts were transformed using the SCTransform function from the Seurat R package with percentage mitochondrial DNA, S.score and G2M.score (Cell Cycle Scoring in Seurat) regressed out. Surface antibody counts (ADT assay) and hashtag antibody counts (HTO assay) were centered log-ratio (CLR)-normalized74,80. As we observed batch effects based on surface protein counts between samples that were hashed versus not hashed (Supplementary Data 3), we used the ‘FindIntegrationAnchors’ and ‘IntegrateData’ functions from Seurat81 to correct batch effects in the surface protein counts due to hashing. Batch effects in the transcriptome due to different 10x versions (v1.1 and v2 (Supplementary Data 3) were also corrected (using ‘SelectIntegrationFeatures’, ‘PrepSCTIntegration’, ‘FindIntegrationAnchors’ and ‘IntegrateData’ functions in Seurat).

Cell type annotation

Azimuth24 was applied in combination with canonical marker genes to annotate cell types in the single-cell 10x Genomics dataset. Cells derived from peripheral blood samples were analyzed using the Azimuth peripheral blood reference map and cells derived from bone marrow samples were analyzed using the Azimuth bone marrow reference map. Cells that had a low cell type annotation score according to Azimuth and clustered in a different immune cell lineage (e.g. annotated B-cell with low score in myeloid Seurat cluster) were annotated as doublets. Azimuth cell type annotation in combination with canonical marker genes and surface proteins was used to annotate detailed cell type clusters from Seurat.

Immune repertoire analysis

Reads from the scTCRαβ and scBCR immune repertoire libraries (10x Genomics) were processed using the Cell Ranger vdj command. For patient 10 only, we included the --denovo parameter to detect TCRαβ motifs in the leukemia cells. Immunarch was applied to analyze TCRαβ diversity in normal T cells82. Only patient samples with at least 50 normal T cells were included in the analysis. TCRαβ diversity was assessed by the Chao1 diversity estimation using the R package immunarch and a t-test was used for statistical analysis. Visualization of unique and clonal clonotypes in healthy donors and T-ALL patient samples was done using the R package TCellPack83. For each of the sample groups, we depicted 1000 αβ T cells, excluding invariant MAIT and NKT cells. In order to analyze TCR features of DNαβ T cells, we applied CoNGA84. T-test statistics of significant TCR features (Mann-Whitney U test FDR < 0.01) were displayed for the CoNGA gene expression clusters.

Differential cell type abundance

Differential neighborhood analysis using MiloR 0.99.11 was performed to identify immune cell types that were over- or underrepresented in T-ALL25. MiloR neighborhoods (where each neighborhood contains multiple cells) were grouped by detailed cell type annotation (e.g. T_CD8naive, Mono_NC, etc) and annotated as significant if more than half of the neighborhoods within the cell type were significant with a threshold of spatial FDR < 0.1.

Copy number variation analysis

To analyze copy number variations in malignant cells and normal T cells, we applied InferCNV 1.6.0 with the Hidden Markov-Model85. HSPCs and T cells from healthy donors in our dataset as well as pan-cancer tumor infiltrating T cells from Zheng et al.11 were used as reference cells. Ribosomal genes (RPS^ and RPL^) were excluded from the analysis due to high variable expression that skewed analysis.

Regulon analysis in single cells

Regulon activity in the 10xGenomics single-cell dataset was analyzed using pySCENIC 0.12.131 using a downsampled dataset of 9323 immune cells with a maximum number of 300 cells for highly abundant cell types (e.g. CD4+naïve, classical monocytes, etc.) per group (i.e. healthy donors and T-ALL patient samples). We included T cells from healthy donors and from T-ALL patients at initial diagnosis that had DNαβ T cells (i.e. T-ALL group 2). To compare differences in regulon activity across transcription factors, pySCENIC regulon activity was scaled across all cell types.

T cell signature scores

We computed signature scores by taking the average expression of genes present in gene signatures, including the T cell stemness signature86 and our DNαβ T cell signatures. We computed a DNαβ T cell transcriptomic and surface protein expression signature by taking 20 genes (transcriptome signature) and 9 surface proteins (surface protein expression signature) that were differentially enriched between T cell types. For the transcriptomic signature, we excluded genes that were expressed in > 85% of T cells other than DNαβ T cells to ensure high specificity scores (Supplementary Data 5).

Cell-cell interactions and ligand activity

To analyze ligand-receptor interactions in the T-ALL microenvironment, we first applied NATMI35 to identify cell-cell communications in T-ALL patient group 2 with high specificity. Also, by using NATMI, we identified significantly appeared interactions in T-ALL group 2 patients compared to group 1 patients and healthy donors. To further investigate ligand activities in DNαβ T cells, we performed differential NicheNet 1.1.036 analysis between niches of interest (e.g. DNαβ T cells as receiver, non-classical monocytes as sender cells). Ligand activities were prioritized which were higher in the group 2 T-ALL immune network compared to group 1 T-ALL patients.

Gene ontology analysis

DAVID gene ontology software (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/tools.jsp) was used to investigate overrepresented gene ontologies of marker genes. Marker genes were identified using the “PrepSCTFindMarkers’ and ‘FindAllMarkers’ function from Seurat in R.

Low input bulk RNA-seq analysis using the Smart-seq2 protocol

Paired-end sequencing reads were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq (2.20), trimmed using trimmomatic 0.36 and aligned to the human genome (hg19) using STAR (2.5.2b) aligner with the following parameters: twopassMode Basic; alignIntronMax 100,000; alignMatesGapMax 100,000; alignSJDBoverhangMin 10; alignSJstitchMismatchNmax 5 −1 5 5. HTSeq (0.9.1) read counts were used as input to generate a Seurat object (CreateSeuratObject) in R. Reads were normalized (NormalizeData) and scaled (ScaleData) using Seurat in R. We applied RScenic31 to analyze regulon activity in in vitro activated T cells. Regulon activity was scaled and averaged across all samples. Clustering of regulons was done using Pearson correlation and ward.D2 hierarchical clustering.

Analysis of primary pediatric T-ALL bulk RNA-seq datasets

To analyze the clinical relevance of our identified signature, we first performed differential expression analysis between malignant cells of T-ALL group 1 and T-ALL group 2 (‘FindAllMarkers’ function from Seurat). Cells were downsampled per patient to limit patient-specific effects as well as effects due to the different 10X Genomics versions (see Supplementary Data 3) used. In addition, genes were excluded if expressed in <= 2 patients to exclude patient-specific gene expression profiles. Our score contained the top 15 genes higher expressed in T-ALL group 2 or T-ALL group 1, with genes excluded that were expressed in > 90% in the comparison group to ensure high specificity scores. To validate our single-cell RNA-seq results in primary T-ALL bulk RNA-seq datasets, we analyzed three bulk RNA-seq datasets of pediatric T-ALL patient samples.

We analyzed a bulk RNA-seq dataset (n = 265) that was generated by the Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments initiative (https://ocg.cancer.gov/programs/target/projects/acute-lymphoblastic-leukemia) to study the association between score group 2 with T-ALL oncogenic groups. The data are available at the Genomic Data Commons (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). Htseq raw counts were downloaded from the TARGET database and normalized using DESeq287. Samples were divided in three groups based on group 2 score and a chi-square test was performed to analyze enrichment of oncogenic groups in lower versus upper tertiles.

To validate the leukemia gene signatures, we analyzed bulk RNA-seq data from patients treated on the DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 16-001 (GSE18115744) for which clinical immunophenotyping was available. Bulk RNA-seq htseq counts were normalized using DESeq2 in R used to calculate the gene expression scores. We also analyzed the percentage of CD4-CD8-CD7- T cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirates at time of diagnosis using clinical phenotyping data. CD7 was included as TCRαβ/γδ flow data was not available and inclusion of CD7 was sufficient to distinguish DNαβ T cells from DNγδ T cells. Patients with >3% DN T cells were annotated as group 2 by flow and a Wilcoxon-rank sum test was performed to test differences in group 1 and group 2 signature scores.

To assess clinical relevance, we analyzed bulk RNA-seq data from the Gabriella Miller Kids First Pediatric Research Program in Pediatric T cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia dbGaP project phs002276.v2.p1, which are available from Kids First Data Resource Portal (https://kidsfirstdrc.org/) and dbGaP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs002276.v2.p1). We restricted our analysis to patients who were diagnosed at or under 18-years of age (n = 1249). Raw rsem counts were imported using the tximport function from the R package tximport. Zero length and genes not expressed were removed and remaining genes were normalized using the DESeqDataSetFromTximport function from DESeq287 followed by vst normalization in R. The sum of the expression of the genes in each of the score 1 and 2 genesets was used to calculate the final patient scores. Patients were split in three equal groups based on the score and subsequently separated in MRDlow and MRDhigh patient groups. Overall and event-free survival was based on 5-year censoring. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were generated using the ‘survival‘ package in R and a log-rank test was used for statistical testing.

Publicly available RNA-seq datasets from healthy donors

To compare CD45+ immune cells from adult healthy donors (our data) and pediatric healthy donors, we processed publicly available single-cell RNA-seq data (10x Genomics). Single-cell pediatric bone marrow (GSE13250917) and pediatric peripheral blood (GSE16873288) were processed as described before for our single-cell RNA-seq samples. In short, we applied Scrublet77 to remove doublets, quality control in Seurat24,79, and cell type annotation using Azimuth bone marrow or peripheral blood references24.

For bulk RNA-seq analysis of publicly available datasets (Thymocytes: GSE15107989,90, healthy PBMCs: GSE10701191), we mapped reads to reference genome hg19 using STAR as described earlier for low-input RNA-seq. Htseq counts were normalized using DESeq2 in R and log2 normalized counts were used to analyze expression of selected genes.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size, and no data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment due to the limited number of samples available and the exploratory nature of the study. Statistical analysis was performed in R. All boxplots were generated using ggplot2 in R. Boxplots show the median and the interquartile range (IQR, box from 25th to 75th percentile). The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 × IQR and values higher or lower than this are plotted as outliers.

Reporting summary